Coastal Forest Fisheries, Estuarine Livelihoods, and Human Well‑being in Southern Puerto Rico

Carlos G. García‑Quijano1,2 · Hilda Lloréns1,2 · David C. Griffith3 · Miguel H. Del Pozo4 · John J. Poggie1

Accepted: 18 September 2023

© The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2023

Abstract

Estuaries and coastal forests, including the coastal fisheries they support, are among the most biodiverse and productive ecosystems on Earth. In Southern Puerto Rico (SPR), there is a culturally significant emic category of estuarine/coastal forest resource utilization known as “Pesca de monte” (tropical coastal forest fisheries, TCF fisheries hereafter) that constitute a parallel activity to commercial fisheries underreported in fishery statistics. Our three years of field research revealed that SPR communities derive considerable value from TCF resources, showing multiple engagements with these environments and wide-spectrum resource dependency. The value generated by TCF use includes the social and cultural acts of production and exchange in households, neighborhoods, and communities, whether the resources are sold, bartered, given as gifts, or consumed directly. Coastal policy that fails to protect productive TCF landscapes or hinders community access to these resources risks degrading human well-being around the coast. We discuss the implication of our findings for coastal policy in TCF fishery dependent regions such as SPR.

Keywords Puerto Rico Fisheries · Mangroves · Tropical Coastal Forests · Coastal Livelihoods · Food security · Reciprocity · Human Well-Being · Local Ecological Knowledge (LEK) · Southern Puerto Rico

Introduction

Human well-being is the fundamental objective of public policy and development, but metrics like Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Income per Capita (ICP), are inadequate

* Carlos G. García-Quijano cgarciaquijano@uri.edu

Hilda Lloréns hilda_llorens@uri.edu

David C. Grifth grifthd@ecu.edu

Miguel H. Del Pozo miguel.delpozo@upr.edu

John J. Poggie jpoggie@uri.edu

1 Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA

2 Department of Marine Afairs, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA

3 Department of Coastal Studies, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA

4 Departamento de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Puerto Rico-Ponce, Ponce, Puerto Rico

proxies for measuring actual human well-being because they rest upon unfounded assumptions about the determinants of human well-being. This realization has motivated some to seek more holistic frameworks to understand and measure well-being (Costanza et al., 2014; Daly & Cobb, 1994; Kubiszewski et al. 2013, 2017; Jackson, 2020).

Environmental social scientists have increasingly focused on understanding the foundations of well-being to inform environmental management that enhances the co-production of value in human ecosystems (Biedenweg & Gros-Camp, 2018; Charnley et al., 2017; Costanza et al., 2014; Hicks et al., 2016; O’Neill 2002; Pollnac et al., 2006; Smith & Clay, 2010; Stiglitz et al., 2010). Studies have identified multiple links between the utilization of coastal resources by human communities and aspects of human well-being such as food security, cultural identity, self-determination, life satisfaction, job satisfaction, economic resilience, enjoyment of the natural environment, and family/community relationships (Breslow et al. 2016; Coulthard et al., 2011; Donkersloot et al., 2020; García-Quijano et al., 2015; Pollnac et al., 2006; Pollnac & Poggie, 2008; Seara et al., 2017). However, the complex and critical human-environment relationships of natural-resource dependent peoples, particularly those engaging in livelihood practices to some extent outside the

formal economy, require further insights from the intersection of social and ecological sciences (García-Quijano & Lloréns, 2017; Tsing, 2015).

Coastal Subsistence Patterns in Puerto Rico

Many families and communities in the rural coasts of Puerto Rico (PR) and elsewhere in the Caribbean combine multiple livelihoods of coastal resource use, preparation, and marketing with mainstream jobs in agriculture, retail, services, government, and local industries (Comitas, 1973; Griffith & Valdés Pizzini, 2002; Griffith et al., 2007; GutiérrezSánchez, 1982). This mixed coastal subsistence pattern has existed for hundreds of years throughout Puerto Rico’s coasts and dates at least as far back as early plantation economies, when enslaved sugar workers supplemented their diet and economy with local coastal resources. After emancipation, formal employment for most people was unpredictable and often limited to sugarcane planting and harvest times. Coastal resource use was especially important for survival during the dead season of sugarcane agriculture, locally called “el invernazo” (literally “the punch of winter”). After 1990, sugarcane in southeastern PR was replaced by other industries, including energy production, pharmaceuticals, tourism, and construction, that episodically hire and fire large numbers of non-skilled workers (Berman-Santana, 1996). This has fostered a strong tradition of self-reliance

and independence typical of rural coastal peoples (GarcíaQuijano, 2006; Pollnac & Poggie, 2008).

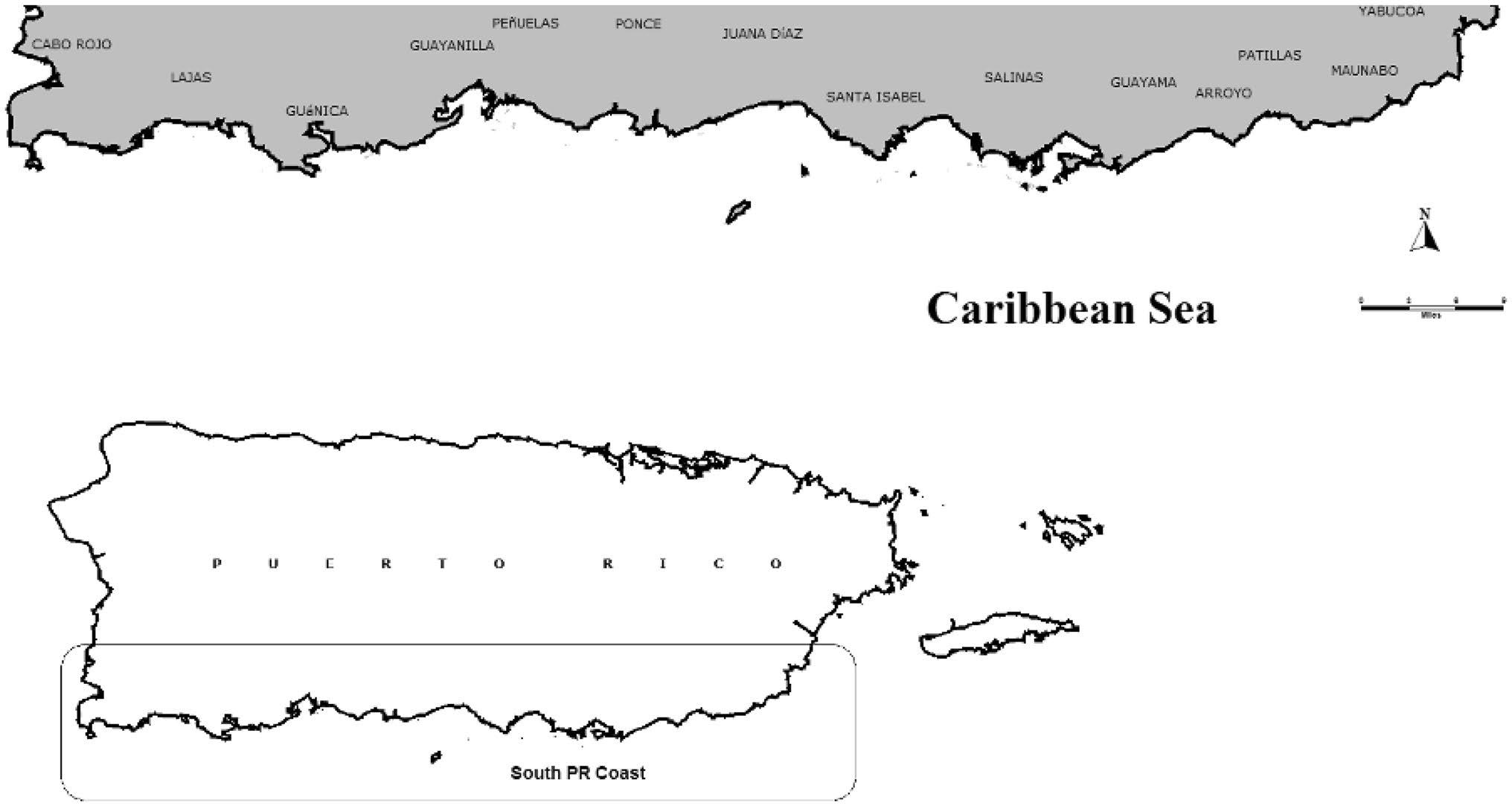

Most Puerto Ricans on the archipelago’s large island reside on the coastal plains, such as the southern region where we conducted our fieldwork (Fig. 1). Coastal mangrove and estuarine forests occur throughout the region, including two of the largest estuaries in Puerto Rico, the Bay of Jobos and Bosque de Boquerón (Dominguez, 2008; Field et al., 2008; Lugo, 1988), which have an extended history of settlement and use by humans (Field et al., 2008; García-Quijano, 2006; García-Quijano et al., 2016; GiustiCordero, 1994, 2015).

Tropical Coastal Forest (TCF) Resources in Human Perspective

Millions of people around the world make at least part of their living from the resources found in tropical and subtropical estuarine forests such as mangroves and related wetlands (Beitl et al., 2019; Das, 2017; Diegues, 1999; Glaser, 2003; Jones, 1985; Márquez Perez, 2019; Treviño, 2022; Walters et al., 2008; Zu Ermgassen et al., 2021). Aside from providing abundant food resources, these ecosystems support tropical fisheries production because they provide essential habitat for up to 80% of important fishery species at different times during their life histories (Das, 2017; Hamilton & Snedaker, 1984). TCFs also support these fisheries indirectly as they interact with other coastal ecosystem types such as

seagrasses, coral reefs, and even pelagic zones (CarrasquillaHenao & Juanes, 2017; Koenig et al., 2007; Mumby et al., 2004; Nagelkerken et al., 2008; Robertson & Duke, 1990). TCFs provide ecosystem services to neighboring human communities, such as storm surge protection and improved water quality (Costanza et al., 1997, 2014).

Societies and cultures with a historic dependence on TCF resources have developed Local/Traditional Ecological Knowledge regarding coastal forests and their processes, as well as traditions of subsistence, foodways, cultural identities, and religious rituals, based on their experience with, dependence on, and interaction with these ecosystems (Stoffle et al. 2020). Diegues (1995, 1999) has used the term “Mangrove civilizations” ( civilizações do mangue) to describe “communities that have developed a specific way of life where economic, social, and cultural activities fundamentally depend on the existence of this coastal flora and fauna [mangroves] and related biological cycles (rhythms of tides, fisheries, etc.)” (1999:201). Further, mangroves, swamps, and other wetland environments long offered sanctuary to escaped slaves, conscientious objectors to civil war, refugees, fugitives, immigrants, and others fleeing formal systems of government and authority. As shifting borders between inland and marine environments, mangroves and other coastal ecosystems have served as locations for smuggling and piracy yet have also served as refuges and settlement spaces for peoples fleeing repressive political economies (Andreas, 2014; Ellis et al., 2014; Fuller, 2021; Griffith, 1999).

Access to healthy coasts and estuarine forests/swamps affords Puerto Rican coastal rural households opportunities for commercial fishing, recreation, leisure, and the incorporation of coastal wild resources into contemporary lifestyles, often resulting in exceptional levels of well-being, satisfaction, and happiness, even when controlling for income or material wealth (García-Quijano et al., 2015, 2019; Seara et al., 2017). TCFs and estuaries have become loci of competition for space and resources for a variety of economic interest sectors, such as tourism, recreation, urbanization, and industry (Brusi, 2004; Griffith et al., 2007; Khazad & Griffith, 2016; Stonich, 2000; Valdes-Pizzini, 2006). These processes have created markets for luxury coastal resources (e.g., queen conch and lobster), benefitting resource harvesters but simultaneously increasing pressure on the habitats on which valued species rely.

García-Quijano et al. (2013) studied the linkages between coastal and marine resource use, from commercial to subsistence, and various aspects of community well-being and quality of life and documented coastal residents’ widespread reliance on a variety of coastal and marine resources for their household economies and food security. This and similar studies identified moral economies of household reproduction and community beneficence related to fishing and the

use of a multiplicity of coastal resources distributed to the community beyond harvesters and their immediate families, while entrenching harvesters in reciprocity networks and thereby enhancing positive community and social relationships (Donkersloot et al., 2020; García-Quijano, 2009; Grace-McCaskey et al., 2021; Griffith, 1999; Griffith et al., 2007, 2013; Poe et al., 2015; Valdés-Pizzini, 2011).

An emergent culturally significant emic category of mangrove and coastal forest resource utilization is known regionally as “Pesca de monte,” translated as tropical coastal forest (TCF) fisheries (see García-Quijano et al., 2015, 2016). TCF fisheries constitute a distinct but parallel activity to marine “commercial” fisheries, which has gone underreported in official fishery statistics and has remained largely ignored. As a result, coastal policy makers are unaware of their value (García-Quijano et al., 2016).

We report on our three-year multi-methods ethnographic research into coastal Puerto Ricans’ utilization of and dependence on Tropical/Estuarine Coastal Forest (TCF) resources. We explore and describe the links between the use of these resources and well-being of coastal community residents.

Methods

We conducted fieldwork between 2016 and 2020. Our research design consisted of two complementary research phases. We first used qualitative ethnography and cultural mapping techniques (Griffith et al., 2007, 2013) to empirically describe and characterize the culture of TCF resource use dependency around the Southern Coast of Puerto Rico. In the second phase, we chose five coastal communities associated with estuarine forests to enable in-depth qualitative and quantitative assessments of the economic and cultural importance of local TCF resources, including direct resource users.

Ethnographic Interviews

We conducted semi-structured, key informant interviews with 35 TCF resource harvesters, 10 TCF resource vendors working in local eateries, and five community activists. Key informants were identified by snowball sampling (Johnson, 1990) focused on identifying local experts in aspects of the harvest, use, marketing, and cultural importance of TCF resources. We also conducted informal interviews with more than 30 coastal residents who were occasional or episodic harvesters around their homes and communities for home or family consumption. During these interviews we gathered data on local definitions of quality of life and wellbeing, as well as the mechanisms by which coastal Puerto Ricans derive value from TCF resource use and associated

Maunabo Emajaguas 19

Juana Díaz El Pastillo 21

Ponce Playa 21

Guayanilla Playa 19

Guánica Playa/Guaypao 20

activities. In addition, we carried out interviews with 30 people (working in 18 seafood eateries) involved in TCF resource marketing in the study region. We gathered specific information about the degree to which Puerto Rican south coast seafood restaurants depend on local TCF resources, the reciprocity patterns related to the use of the resources, the social relationships that support the eateries access to the resources, and the distribution of economic benefits from local TCF resource use.

Interview data were analyzed and coded using HyperResearch (2015) and NVIVO (QSR, 2020) to identify and describe the different modes of engagement with TCF resource use by residents, practices of exchange and reciprocity, local cultural models related to quality of life and well-being, and local ecological knowledge about TCFs. Interviews were conducted in Spanish and most coding was done with the original Spanish interview transcripts.

Structured Interviews with Coastal Households

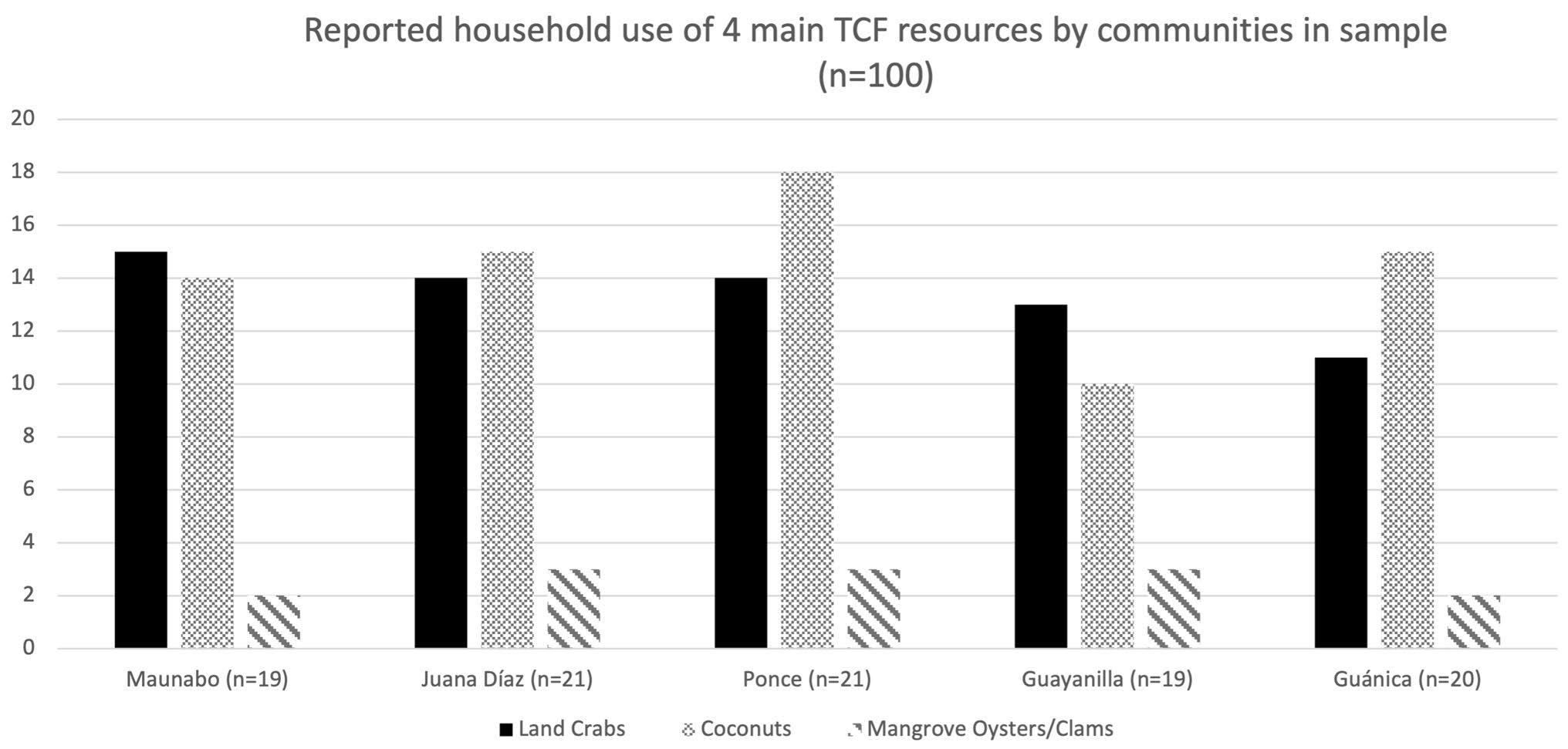

Building on results of ethnographic phase, we designed and conducted structured interviews with a probability sample of 100 households in five SPR communities (Table 1). We used geographic cluster sampling (see Alvarado et al., 2009; Garcia-Quijano et al. 2013, 2015) to choose eligible households for interviews using US Census blocks overlaid on Google Earth ™ freeware aerial photographs. The communities were chosen to maximize representation of East and West, urban and rural, TCF resource engagement, linkages with local and regional economy, and types of resources used (Fig. 2).

The goal of the structured interviews was to assess variation in TCF resource use, dependence, and impacts on human well-being and resilience among a probability sample of households, chosen because they resided in the study region. Analysis of structured interview data had three main goals: 1) to identify patterns of variation in coastal residents’ engagement with TCFs, 2) to identify patterns of variation related to manifestations of well-being, and 3) to build on ethnographic data to identify and understand the mechanisms by which the value generated by TCF resource use in the region reaches people. In the following sections we report on: 1) the diversity of TCF resources, 2) the widespread dependency on local TCFs, 3) how close social relationships and reciprocity practices enhance the value of TCF fisheries value, and 4) the importance of recognizing productive TCF landscapes.

Results

The Diversity of TCF Fishery Resources in Southern Puerto Rico

TCFs in the study region include a variety of ecosystems such as mangroves, wetlands, tidal flats, and associated estuarine bodies of water like mangrove channels, lagoons, and bays. Coastal forests are used extensively, but a specific group of resources-animals and plants used for food-were repeatedly and almost universally referred to as TCF resources.

Atlantic Land Crabs “Jueyes” (Cardisoma Guanhumi)

Land crabs (Fig. 3) are an important component of the diet of tropical and subtropical coastal residents around the world (Abraham & Lambeth, 2001; Alves et al., 2005; Baine et al., 2007; Diegues, 1999; Foale, 1999; Jones, 1985; Rouse, 1992). In Puerto Rico, land crab populations probably benefited from environmental changes when much of the marshes and coastal plains of Puerto Rico were drained or modified for sugarcane cultivation, which expanded favorable habitat (Lugo, 1988). They are routinely captured both for selling and for everyday consumption, by hand (or with metal kitchen tongs) while walking through the coastal forest, especially during reproductive aggregations called corridas, or extracted from their caves (by hand, with a metal hook, or shovels), or using baited traps (trampas, cebos, cajas) placed near cave entrances (see Fig. 7).

Captured land crabs are put in cages, wooden or cement boxes, or modified artifacts such as abandoned bathtubs or barrels, where they are “cleaned and fattened” for between 10 and 21 days, and fed with a variety of plant products such as corn, coconut, bread, mango, or cohítre grass (Commelina longicaulis). Entire households (and, when there is a large corrida, extended families, and groups of neighbors) participate in the tasks associated with capturing, cleaning, picking and/or cooking land crabs. Although capturing jueyes inside the TCF tends to be an activity carried out by men, women also capture crabs and actively participate—and are often in charge of the other activities such as cleaning, fattening, and preparing the meat. Many important and celebratory family events in these communities are celebrated with feasts of land crabs, locally called “jueyadas.” Catching, cleaning, and preparing jueyes is part of the cultural knowledge of the coast.

Land crab populations in Puerto Rico have declined in recent decades due to a combination of factors including high demand and capture rates, destruction of habitat for coastal development, and the abandonment of sugarcane plantations that provided extensive habitat (Govender, 2007; Lugo, 1988; Quiñones Llópiz et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Fourquet & Sabat, 2009). A management plan with a closed season has recently

been implemented (DRNA, 2010). However, coastal residents have been reporting since the early 2010s that they are again seeing “corridas” (mobile reproductive aggregations, literally “crab runs”) of land crabs in numbers comparable to those of several decades ago, which is encouraging (GarciaQuijano et al., 2016). During the period of fieldwork for this research in 2016–2020, residents have corroborated these observations throughout the coast, to the extent that some corridas, especially those in 2017–2018 after Hurricanes Irma and Maria, have been described by long time crabbers and other residents as the largest in 40 years. These large corridas were repeatedly referred to as a sort of “divine restitution” for the suffering caused by the hurricanes.

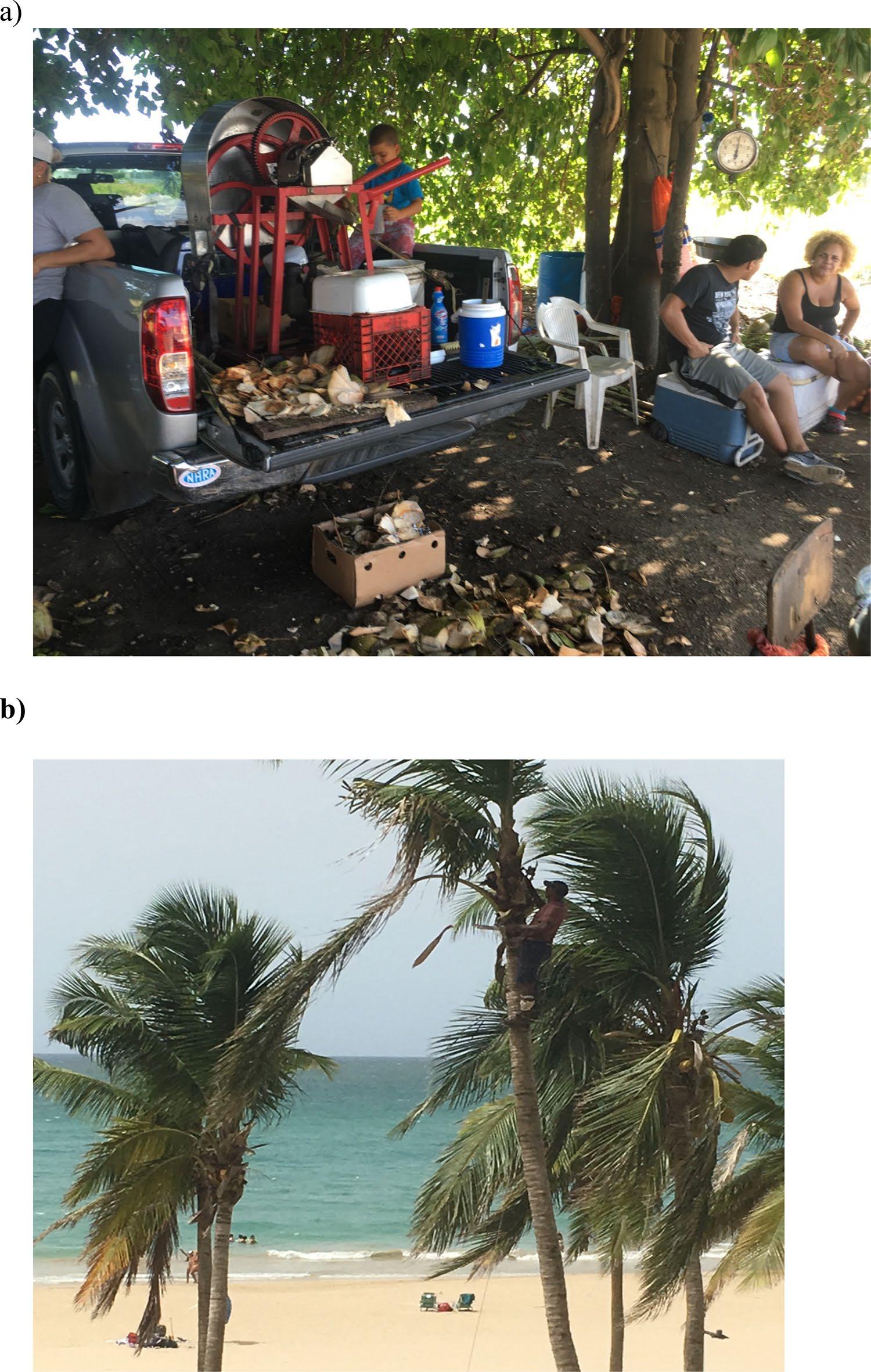

Coconuts (Cocos Nucifera)

The coconut palm is an Indo-Pacific species in origin, introduced by Portuguese colonizers to the Neotropics (Harries, 1992). Coconuts are traded on a large scale globally and are harvested locally by millions of people throughout the tropics for direct use and small-scale trade, as food (coconut water and pulp), oil, and textile fiber (Harries, 1992). Southern PR coastal forests contain abundant coconut palms from a combination of intentional palm planting along with their natural dispersal by land and sea. The harvesting of coconuts figures prominently as a TCF resource use in our study regions, as well as elsewhere in the island (e.g., Giusti-Cordero, 1994, 2015). Most of the coconut harvested by residents in the study area is marketed locally (Fig. 4), for sale as “coco frío” (chilled whole coconut), in roadside stalls, mostly staffed by men, or markets. The preparation of coconut-based foods, such as “dulce the coco” (coconut candy), “limbers” (flavored ice), “arroz con dulce” (rice and coconut pudding), and “arepas de coco” (coconut fritters), to name a few, is mostly done by women. Men, women, and sometimes children, can be found selling these products on roadside stands.

Oysters (Crassostrea Rhizophorae) and Clams (Lucina Pectinata)

Ostiones, or mangrove oysters, are found in Atlantic tropical estuarine areas and tend to aggregate in clusters on the aquatic roots of the red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) (Angell, 1986; Nikolic et al., 1976). Oysters are detached from the mangrove root with a spatula or dulled knife and carefully placed in buckets for transport. White clams (Lucina pectinata), mobile bivalves, 1–8 cm in diameter that live in shallow, low energy sediment bottoms in estuarine and coastal areas across the tropical and temperate western Atlantic (Beasley et al., 2005; Rondinelli & Barros, 2010) are harvested by digging in shallow coastal lagoons between 3–5 feet deep.

Although they are found in different (albeit adjacent) habitats and are caught in different ways, in our study area mangrove oyster fishers tend to also fish for clams and vice versa, although some fishers expressed a preference for one or the other. Oysters and clams are prepared and consumed in similar ways and are generally marketed together. They are usually sold from stalls or carts, where they are eaten raw on the shell, with lemon and/or hot sauce. In our study area, most of the stalls were operated by the fishermen themselves, sometimes assisted by relatives. Often land crabs and coconuts are also sold in the same stall. About half of the oyster and clam fishers we interviewed (or someone else

in their household) also caught land crabs and/or harvested coconuts.

A variety of other coastal resources are utilized and consumed by residents and were occasionally mentioned as TCF fishery resources. These include cocolía or blue crabs (Callinectes sp.), Maví tree (Colubrina spp.) bark,

sea grapes, razor clams, and “wild” sugarcane. A variety of estuarine fish caught in mangrove channels, ponds, springs, and tides are sometimes considered as part of TCF fishery. This includes estuarine fish such as the jarea (Mugil curema ), macho de lisa ( Mugil cephalus/liza ), mojarra (Gerres cinereus), burro (Micropogonias furnieri), as well

as some species that, as part of their feeding, reproductive, or defensive movements, routinely enter estuarine waters. Some examples of the latter are snook (Centropomus undecimalis), sardines and herring (Harengula and Opistonema sp.), ballyhoo (Hemiramphus sp.), cutlassfish (Thichiurus lepturus), and sennet (Sphyraena picudilla). Local harvesters use a gradual continuum to classify these fishing activities as more TCF fishing if they are fished using castnets, in mudflats areas and mangroves channels, and fishing “from shore.” By contrast, fishing done from a boat with gillnets or hooks, or in estuarine areas closer to the sea is considered commercial marine fishing.

TCF Fisheries Harvesting and Consumption

During fieldwork we identified the TCFs of the study region as human ecosystems full of economic activity, a landscape of human labor and economic relationships (see GiustiCordero, 2015) where land crabs, coconuts, and multiple estuarine aquatic species are routinely harvested and where value is added by preparing, processing, selling, and gifting, so they become culturally prized delicacies. Almost every community we visited had visible signs of land crabbing (“se venden jueyes,” [crabs for sale] signs, crab cages in yards) and coconut harvesting (piles of coconuts, tables used to sell coconuts, piles of husks and shells). Fishing for estuarine fish, using “tarrayas” castnets and handlines, and pots for blue crabs, was ubiquitous, and certain coastal communities (mostly in Guayama, Salinas, Santa Isabel, Lajas, and Cabo Rojo) had active kiosks selling mangrove oysters and clams on most weekends (Fig. 4).

From the sample of 100 coastal residents, 26 worked with or derived at least part of their income from coastal resources at the time of the interview. Of these 26 respondents, 10 worked in marine fisheries, three in TCF resources, and 13 worked in both marine and TCF resources. An additional six respondents had at some in their lives worked with or derived income from coastal resources. Fifty respondents had immediate family members who worked with or derived at least part of their income from coastal resources. Of these 50, 20 worked in marine fisheries, nine in TCF resources, and 21 in both marine fisheries and TCF resources.

There was widespread agreement that TCF resources are important for their coastal communities, both for household economies and for identity and culture (see Table 2). People repeatedly mentioned that TCF resource use is important for 1) creating and reproducing quality lives and quality communities, with some using the terms “dead and sad” to describe their communities if they were not able to use TCF resources, 2) providing means of making a living that are alternative to both formal labor markets and socially destructive economic activities such as drug smuggling and other illegal activities, 3) providing a way for the poorest

Table 2 Total reported consumption of 4 main TCF resources that are captured locally (n = 100)

CR # consumers Avg. % from S. Coast (St. Dev.) Avg. % from same community (St. Dev.)

Land Crabs

(2.74) 95.60 (15.30) mangrove oysters/ clams

community members with appropriate LEK to make money or self-provision when needed, such as ex-convicts, the unemployed, and disenfranchised older people. One of our key informants emphasized the importance of TCF fisheries for food security in 2016 when talking about land crabs and coconut harvesting: “… ‘la pesca de monte’ has fed this region since the times of the sugarcane.”

More than 99% of the land crabs, coconuts, and clams/ oysters consumed by coastal residents were reported to be from the South coast, and 91% and 95.6% were reported caught in the same community where the respondent lived (Table 3). Further, 57 respondents (out of the 67 who reported eating land crabs) reported that 100% of the TCF resources they consumed were caught in the community they live in. This has important implications for food security, showing a direct link between access to local estuarine forests (literally around people’s homes and communities) and an important source of nutrition in the form of high-quality protein and nutrients like fatty acids, iron, zinc, calcium, and vitamin D (Kawarazuka & Béné, 2010; Vianna et al., 2020).

Víctor, a 54 year old TCF harvester, told us from his food truck where he sells oysters, clams, and coconuts in a southwestern coastal village:

“I learned how to fish in the mangroves, catch crabs and oysters from the elders. Around here, there was not much to do, but “los viejos” had that knowledge. I learned how to harvest oysters carefully, with a blunt knife, without hurting the mangrove root, so the oysters would grow again, I learned how to keep them fresh and bring them to Boquerón [a SW PR village that is known as a center for eating oysters and clams from roadside vendors and kiosks] and to serve them to the customer. That is how I made a living and stayed out of trouble. I raised my kids from this. That, right there, is my son, he is studying in “El Colegio” (University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez), but in the weekends he helps me sell oysters and coconut water”.

Victor felt proud that his son, a college student, worked with him on the weekends. But not all young TCF fishers were able or willing to pursue education. It was nearly

Table 3 Structured questionnaire responses to question: “ Do you consider local resources to be important for the identity and culture of (family and community)?”

# YES responses (N = 100)

Land Crabs (67)

Coconuts (79) clams/ oysters (13) fsh (82)

ple around here grow up knowing how to get their own, they catch a lot of their fish and land crabs” (interview, July 2016).

universally mentioned that a key contribution of TCF resource use for community well-being is that it represents a viable alternative for young people, especially school dropouts and those already in the criminal justice system, to participate in productive nature-based economic activities.

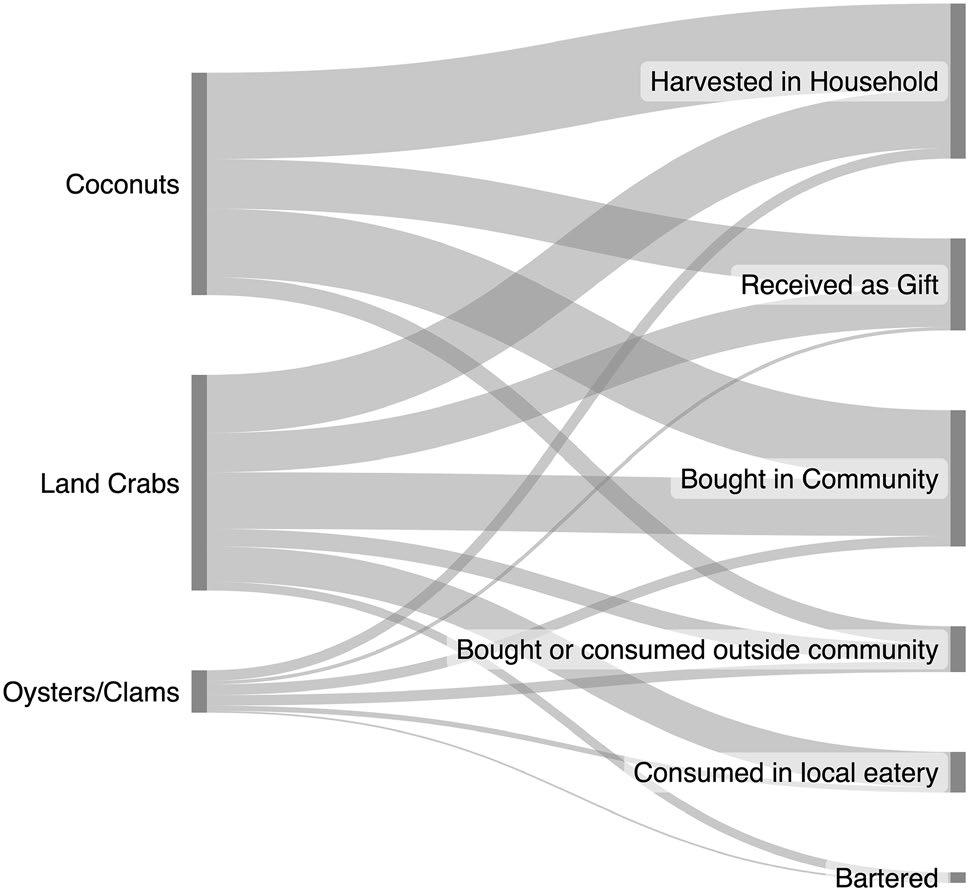

Close Social Relationships and Reciprocity

Echoing the findings of García-Quijano et al. (2013), we found that a significant portion of the high-quality fresh fish and other coastal resources consumed by residents of the study communities depends on close personal family and neighbor networks. TCF resources, specifically, are mostly accessed in both geographic and social proximity to the forager’s/fisher’s household. The most frequent response to our question about the ways in which the three main TCF resources (land crabs, coconuts, oysters/clams) are procured for the household was “captured/harvested by a household member,” which was also the second-most frequent response for finfish. This coincides with our ethnographic observations that it is common for households along the coast to harvest these resources opportunistically in a variety of contexts, for example during a land crab aggregation, as occasional recreational harvesting, or as part of targeted/ sustained harvesting for consumption and sale. It is also common to harvest crabs or coconuts for a specific purpose, for example to get extra money for an unanticipated expense, for an upcoming family feast, to send to friends and family living in the continental United States, or for cooking a specific recipe. Children and adolescents often forage for crabs or harvest coconuts to contribute to their households’ food supply and/or sell to supplement their allowances or their parents’ income. These patterns were described by one of our informants:

“… around here, you might find that people don’t spend too much on local seafood, but it is because peo-

But buy/sell transactions occur overwhelmingly in the context of close social relationships. The response “Bought from a local/community harvester” was the tied for most mentioned way of accessing clams/oysters (6), and secondmost for land crabs (32) and coconuts (39). For land crabs and coconuts, these transactions frequently took place at the homes of harvester, which often advertise land crabs or coconuts for sale, or the consumer. However, we also found that many harvesters who sell land crabs or coconuts from home do not see a need to advertise since they are known to the community and, in the words of a crabber from San Felipe in Salinas: “They know where to find me, and that I am a land crabber and have good crabs for sale. Just like you found out about me by asking around” (July 2016 interview). People also reported widespread practices of deferred payment for TCF resources based on trust and social closeness. Similarly, a crabber in Guayanilla told us:

“Sometimes I put the sign up, but even if I forget, people are always coming looking for jueyes, by the dozen and for picked meat too. Some of them I know, some of them just somehow find that I have “jueyes limpios” (cleaned crabs) and show up at my door. My wife makes coconut limbers (flavored ice), so sometimes people come for a limber, and end up leaving with a dozen crabs” (January 2018 interview).

Gift-giving reflects social closeness (Mauss, 1954). Supporting our findings in a previous study, we identified widespread gift-giving of TCF resources.1 All interviewed harvesters reported routinely giving part of their catch to family, friends, and community members. Thirty-four of our 100 household questionnaire respondents reported routinely receiving local TCF resources as gifts (Table 4). From the harvesters’ perspective, several expressed that they considered giving their harvest as a gift and thus entering the “open reciprocity” (Graeber, 2014) economy to be of comparable economic importance to selling their harvest. Indeed, contrary to what would be expected by assumptions of maximizing profit, some crabbers kept the very best, highest value crabs for giving away rather than for selling, as illustrated by a July 2018 conversation in a crabber’s home. He indicated: “right here, in this box, I keep the best crabs, the largest and fattest.” When asked if he intended to sell them at the highest prices, he laughingly responded:

1 García-Quijano et al. (2013) found 45 out 97 residents reported receiving fsh and other coastal resources as gifts and 97% of harvesters reported routine gift-giving.

Table 4 Structured questionnaire responses to question:

“Approximately what percentage of TCF resource (s) are bought, received as a gift or captured by household member?”

“No, these are ‘los jueyes para regalar’ [the crabs for giving away]. I save them for my family or my friends when they visit me, we cook some crabs, and eat, and have a beer or two. Next time you come here, I can make you a few ... Right now, I have 3 dozen that I will parboil, freeze, and sent express mail to my sisters in Chicago and Boston. They get so happy when they receive the crabs, it reminds them of home.”

Indeed, we found that parboiling, freezing, and sending land crabs (either whole or just the land crab meat) to family in the continental USA is a common practice for both crabbers and regular consumers, who buy them and send them by express mail or in a traveler’s luggage. In every case, the sending and receiving of these gifts was described as a joyful act of expressing cultural identity through foodstuffs and of helping maintain connections. Because the majority of crabbers in PR are Black and Afro-descendants, Lloréns and García-Quijano (2020) called this an expression of “mobile Black ecologies.” These connective practices sustain and deepen kinship and friendship bonds, express care and sharing despite (or as a result) of displacement, migration, and distance. By engaging in these mobile food sharing practices, the TCFs enhance the experience of their relatives and friends in the Puerto Rican diaspora and serve to cement ties that can also result in jobs and places to stay in the continental United States. In sum, this practice illustrates the significance that the coastal ecology and its foodstuff has on its residents, working as a marker of cultural identity and belonging, even when they have chosen or been forced to live far away.

Local coastal resources production and marketing through restaurants in the study region likewise relies strongly on personal connections and local social networks. For example, when responding to questions about and the type of relationship they had with the harvesters who caught the land crabs they sell, seafood (Fig. 5) vendors reported that the most common type of relationship was a “personal, local, casual relationship” (11 for land crabs, 10 for fish), followed by “close, contractual relationship” (1 for land crabs; 3 for fish) and “anonymous, market-type relationships” (3 for land crabs, 4 for fish). One restaurant owner caught their own land crabs to sell in their restaurant. Thus, 13 of 18 of

restaurants get their land crabs and their fish through local, personal relationships (contractual, casual, and self). This ties the restaurant sector closely to local producers and local resources (cf. García-Quijano et al. 2013).

Gift or Market Economies?

An important policy implication of these results is that a significant portion of the real value people get from TCF resources will be missed if it is measured by standard economic, currency-exchange approaches: of the four most frequent ways that people reported accessing local TCF resources, two do not involve currency exchange at all, and the other two most frequently rely on informal market exchanges, unlikely to be reported or captured in official expenditure records. Assessments of the value of local fisheries based on currency expenditures are most probably grossly underestimating the value of these activities for local populations, as has been reported for the Pacific

Fig. 5 TCF resource access fows into sampled coastal households (n = 100). Width of bars refect numbers of times the diferent ways of accessing TCF resources were mentioned by household respondents. Diagram created using SankeyMATIC (2023)

NW, where 26 out of 27 local fisheries were found to resemble subsistence/gift economies rather than “market” economies, with important implications for the assessment of their value and how to manage them (Poe et al., 2015).

Recognizing ‑and Redefining‑ Productive Landscapes on the Puerto Rican Coast

TCF resource-use activities and the value they provide to the region depend on access to ecologically healthy, productive coastal landscapes. LEK contributes to both harvesting and management of these landscapes, for example, purposefully leaving portions of land crab burrows unfished when using traps, taking only a portion of land crabs during a “corrida,” leaving some oysters in mangrove roots to maintain the substrate suitability of the roots (and harvesting carefully with a blunt-edged knife, to not damage the mangrove roots), and leaving some clams

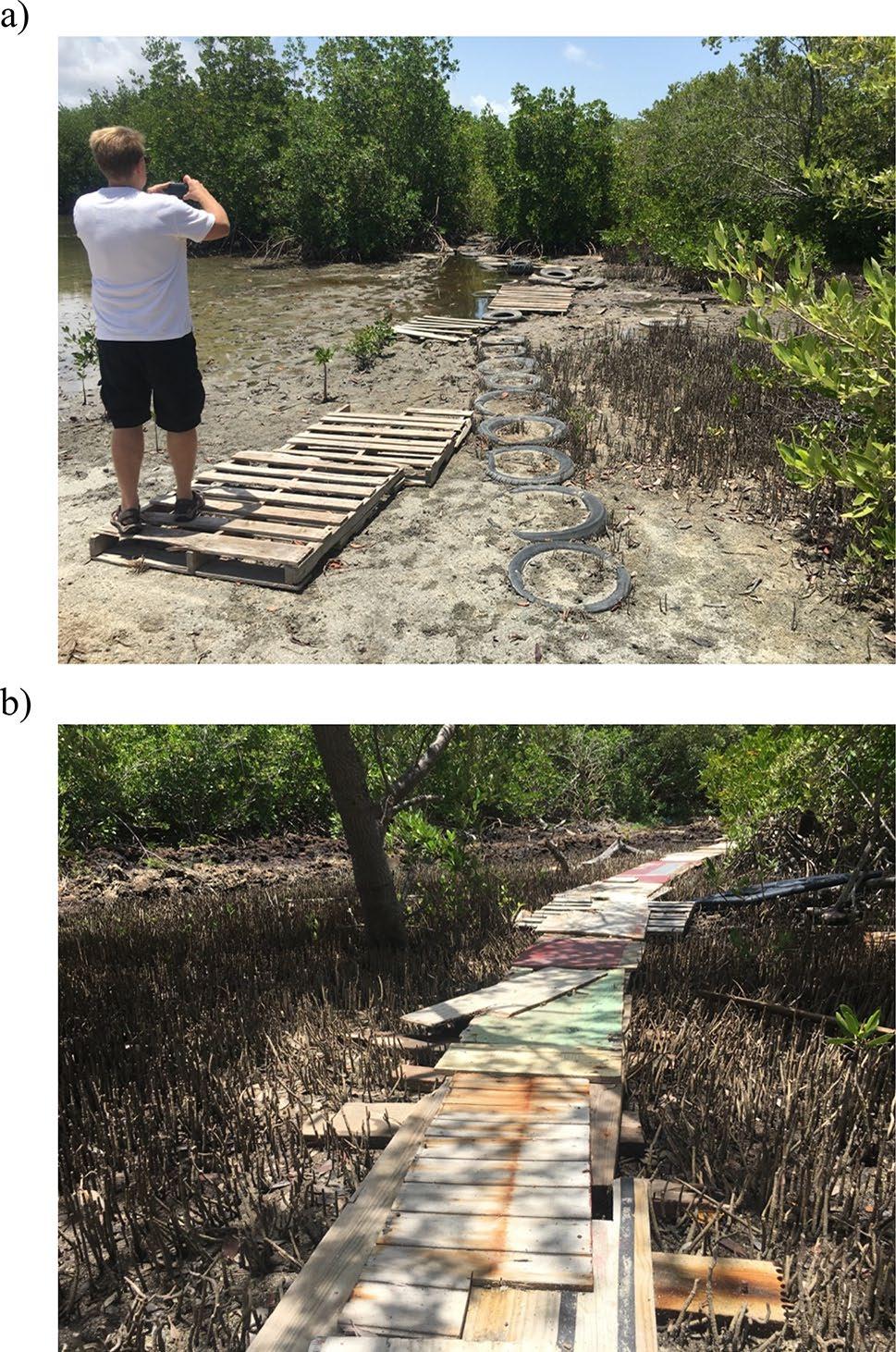

undisturbed in used substrates to maintain productivity. Broader environmental management activities, geared to maintain ecosystem productivity and/or ease of access (e.g. Sutton & Anderson, 2014), include removing debris to improve drainage in productive land crabbing areas, pruning vegetation to maintain water flow in mangrove channels where oysters are harvested, and building and maintaining makeshift board walks (with driftwood and discarded pallets, for example, see Fig. 6) to avoid trampling over productive tidal flats and mud substrates.

The ability to recognize these productive landscapes is an important element of LEK in the study area: what may appear to an outsider as fallow, mixed use, or “unproductive” land can in fact be prime harvesting grounds that bring sustained (and sustainable) value to coastal communities. As a crabber told us (Garcia-Quijano and Lloréns) in July 2018 while he was checking crab traps in near Pozuelo, Guayama (Fig. 7):

“Look here, this is what crabs like: good soil, a lot of food, some dead trees and rotting stuff to eat, and places to hide. This is a treasure for us…. I think this is the reason there were such large “corridas” after the storms because there was a lot of debris and fallen vegetation. This is a good environment for land crabs.”

A few days after this interview, a food truck owner (and former crabber) in the southwestern town of Cabo Rojo remarked over a meal of “Arroz con Jueyes”:

“… it is amazing, people do not know that all this good food that they pay for comes out of those “pastizales” (fallow, overgrown grassy areas) right there, and that “los viejos”(the older folk) catch it for them.”

He then described how disenfranchised older people who are able to catch crabs are especially dependent on them for much-needed cash to supplement meager retirement incomes.

TCF activities, especially land crabbing and coconut harvesting, occur in fallow, mixed use areas near mangroves, around communities, between houses and common areas, and often even in people’s yards (Fig. 7). Recognition of the productive activities that occur in and around coastal backyards has important implications for understanding the costs of coastal dispossession: displacement by industry, gentrification, tourism, or recreation facilities adds to the challenges facing people already in precarious economic straights as they lose backyard livelihoods that are difficult to replicate elsewhere. At the same time, as the holders of valuable local ecological knowledge and food production traditions are separated from their productive ecosystems, the wider society also loses a significant layer of resilience and food security. Our analysis underscores the value of protecting the natural areas around and between communities, even (or especially) mixed use, abandoned, or fallow lands that well-meaning but ill-informed developers or coastal planners might perceive to be unproductive.

Conclusions

Overall, our research indicates that coastal Puerto Ricans derive considerable value from tropical coastal forest resources, showing multiple entanglements with these coastal environments and communities, and wide-spectrum coastal resource dependency. The value generated by TCF resource use thus includes social and cultural acts of production and exchange occurring in households, neighborhoods, and communities, whether resources are sold commercially, bartered, given as gifts, or consumed directly. This value has routinely been underestimated because TCF resource-based activities tend to occur in rural coasts and outside formally reported economic transactions and exchanges, conditions that make it easier for developers to deem these coastal areas unproductive.

The cultural traditions and local ecological knowledge that empower coastal community residents to access valued TCF resources present a unique contribution to human well-being in economically disadvantaged coastal regions such as Southern Puerto Rico. Engaging with TCFs by utilizing a variety of strategies continuously and episodically for harvesting for sale or direct consumption, giving and receiving as gifts, or buying locally, allows community residents to enhance their well-being and resilience in the face of sustained structural disadvantages such lack of access to income and political connections, labor exploitation and discrimination, and environmental injustices. We identified positive relationships between local TCF resource uses and various dimensions of coastal residents’ well-being, including food security and sovereignty, income flexibility, household economic resilience, enjoyment and enhancement of social relationships and social capital, and providing alternative livelihood opportunities for those in most need. Previous research found that TCF harvesters report significantly higher life and job satisfaction compared to other people in their communities, even when controlling for income or wealth (e.g., García-Quijano et al., 2015). As we observed in the aftermath of the recent debt crises and Hurricanes Irma and Maria, the benefits of TCF use and access are augmented in situations such as economic crises or environmental disasters where state or market systems falter and reciprocity networks and social capital gain importance relative to - even temporarily substituting formarkets and money in local economies (Grace-McCaskey et al., 2021; Roque et al., 2020, 2021).

Many southern Puerto Ricans who live in these environments know of the value of TCF resources and have organized to protect access to productive coastal lands and share knowledge about their value (de Onís, 2021; Lloréns, 2021). For example, in an October 2021 phone interview with a community organizer we learned that residents in the village of

San Felipe in Salinas had started organizing to protect coastal lands from outside development using their dependence on land crabs and other TCFs as a rallying point (Fig. 8). A considerable amount of the community outreach and collaboration stemming from our research program has consisted of providing systematically gathered data and “expert” opinion (although our informants are the real experts) to support organizing and court battles by locals to protect these environments from outside development and to secure their access to them (García-Quijano et al., 2013, 2021).

As fishing and coastal foraging often occur as traditional, subsistence, small-scale, or petty commodity economic activities, our results call attention to the value of livelihood strategies that are alternative to the growth dependencies that come with (hourly or salaried) labor in the formal economy (e.g., Jackson, 2020). These strategies can make communities highly resilient both economically and in terms of overall well-being, but only as long as they retain access to a relatively healthy local ecosystem (García-Quijano et al., 2016). A catastrophic loss of resilience can happen if the communities are excluded from access to their local ecosystems by, for example, being displaced by coastal development, gentrification and/or overly tough harvest regulations, or if resources become degraded by pollution, habitat destruction, or overharvesting. As a crabber and community activist commented in 2011:

“Jobs and industries come and go, but as long as the coast is healthy around here, we will never go hungry”.

Acknowledgements We are thankful for the collaboration of many southern coast Puerto Ricans who generously gave us their time and shared their knowledge and experience with us. Without their collaboration this research would not have been possible. The staff of Puerto Rico Sea Grant and of the Jobos Bay NERR provided unending advice and support in the field. We specially want to thank Ruperto Chaparro, Manuel Valdés-Pizzini, Lillian Ramírez, Michelle Schärer-Umpierre, and Angel Dieppa. We thank our dedicated student researchers, Dayanara Soto, Kevin Torres, Neysha Beltrán, Hernaliz Vazquez, Lorence Morell, and Aileen Santiago, from the University of Puerto Rico-Ponce, for their efforts during fieldwork. Alejandro Torres-Abreu, María Cruz-Torres, and the Ethnographic Field School at the UPR-Humacao also assisted our fieldwork. José A. Alvarado provided valuable help in our sampling and analysis.

Authors Contribution All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Authors García-Quijano, Del Pozo, Griffith, and Lloréns contributed to data collection and all authors contributed to analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by García-Quijano and all authors contributed to subsequent versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding This research was funded by a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration- University of Puerto Rico Sea Grant (Project # UPR-2016-2017-006 – R/101-1-16).

Data Availability The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to protect the confidentiality

of ethnographic study participants. They are kept on the corresponding author’s personal repository at the University of Rhode Island. Aggregated or anonymized data can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Informed Consent The study was done in compliance with the University of Rhode Island’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines for studies of human subjects, including processes for informed consent and ensuring confidentiality.

Competing Interests The authors declare no competing interests.

References

Abraham, R., & Lambeth, L. (2001). An Assesment of The Role of Women in Fisheries in Kosrae, Federated States of Micronesia. 3: Secretariat of the Pacific Community Fisheries Section.

Alvarado, J., Gavillán, J., & Germosen-Robineau, L. (2009). TRAMIL ethnopharmacological survey: Knowledge distribution of medicinal plant use in the southeast region of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, 28, 329–339.

Alves, R., Nishida, A., & Hernández, M. (2005). Environmental perception of gatherers of the crab “caranguejo-uçá” (Ucides cordatus, Decapoda, Brachyura) affecting their collection attitudes. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 1(10), 1–8.

Andreas, P. (2014). Smuggler Nation: How illicit trade made America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Angell, C. L. (1986). The Biology and Culture of Tropical Oysters. 13. Manila, Phillipinnes: International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management.

Baine, M., Howard, M., Taylor, E., James, J., Velasco, A., Grandas, Y., & Hartnoll R. G. (2007). The development of management options for the black land crab (Gecarcinus ruricola) catchery in the San Andres Archipelago, Colombia. Ocean and Coastal Management, 50(7):564–589.

Beasley, C. R., Fernandes, C. M., Gomes, C. P., Brito, B. A., Santos, S. M. L., & Tagliaro, C. H. (2005). Molluscan diversity and abundance among coastal habitats of northern Brazil. Ecotropica, 11, 9–20.

Beitl, C. M., Rahimzadeh-Bajgiran, P., Bravo, M., Ortega-Pacheco, D., Bird, K. (2019). New valuation for defying degradation: Visualizing mangrove forest dynamics and local stewardship with remote sensing in coastal Ecuador. Geoforum, 98, 123–132. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.024

Berman-Santana, D. (1996). Kicking Off the Bootstraps: Environment, development, and community power in Puerto Rico. University of Arizona Press.

Biedenweg, K., & Gross-Camp, N. D. (2018). A brave new world: Integrating well-being and conservation. Ecology and Society, 23(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09977-230232

Breslow, S. J., Sojka, B., Barnea, R., Basurto, X., Carothers, C., Charnley, S., Coulthard, S., Dolsak, N., Donatuto, J., GarciaQuijano, C., Hicks, C. C., Levine, A., Mascia, M. B., Karma, N., Satterfield, T. M., St. Martin, K., Levin. P. S. (2016). Conceptualizing and Operationalizing Human Wellbeing for Ecosystem Assessment and Management. Environmental Science & Policy 66, 250–259.

Brusi, R. (2004). Living the Postcard : Place, Community, and The Production of La Parguera’s Landscape. Cornell University. Carrasquilla-Henao, M., & Juanes, F. (2017). Mangroves enhance local fisheries catches: A global meta-analysis. Fish and Fisheries, 78(1), 79–93.

Charnley , Susan, Courtney Carothers , Terre Satterfield , Arielle Levine, Melissa R. Poe, Karma Norman, Jamie Donatuto, Sara Jo Breslow, Michael B. Mascia, Phillip S. Levin, Xavier Basurto, Christina C. Hicks , Carlos García-Quijano , Kevin St. Martin ,. (2017). Evaluating the best available social science for natural resource management decision-making. Environmental Science and Policy, 73, 80–88.

Comitas, L. (1973). Occupational Multiplicity in Rural Jamaica. In Work and Family Life: West Indian Perspectives. L. Comitas, and David Lowenthal, ed. 157–173. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Costanza, R., D’Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R. V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R. G., Sutton, P., & van den Belt, M. (1997). The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital. Nature, 387, 253–260.

Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Giovannini, E., Lovins, H., McGlade, J., Pickett, K., Ragnarsdóttir, K., Roberts, D., De Vogli, R., & Wilkinson, R. (2014). Time to leave the GDP behind. Nature, 505, 283–285.

Coulthard, S., Johnson, D., & JAllister McGregor,. (2011). Poverty, sustainability and human wellbeing: A social wellbeing approach to the global fisheries crisis. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 453–463.

Daly, H., & Cobb, J. (1994). For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Das, S. (2017). Ecological Restoration and Livelihood: Contribution of Planted Mangroves as Nursery and Habitat for Artisanal and Commercial Fishery. World Development, 94, 492–502.

De Onís, C. (2021). Energy Islands: Metaphors of Power, Extractivism, and Justice in Puerto Rico: University of Callifornia Press. Diegues, A. C. (1995). Os pescadores artesanais e a questaõ ambiental. In Povos e Mares. A.C. Diegues, ed. Pp. 131–139. Sao Paulo, Brazil: NUPAUB.

Diegues A. C. (1999). Human populations and coastal wetlands: Conservation and management in Brazil. Ocean & Coastal Management, 42, 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0964-5691(98)00053-2 Dominguez-Cristobal, C. (2008). La politica forestal del manglar en Puerot Rico durante el siglo XIX: El caso del manglar de Jobos, Las Mareas, Caño Grande y Punta Caribe de Guayama. Acta Cientifica, 22(1–3), 67–77.

Donkersloot, R., Black, J. C., Carothers, C., Ringer, D., Justin, W., Clay, P. M., Poe, M. R., Gavenus, E. R., Voinot-Baron, W., Stevens, C., Williams, M., Raymond-Yakoubian, J., Christiansen, F., Breslow, S. J., Langdon, S. J., Coleman, J. M., & Clark, S. J. (2020). Assessing the sustainability and equity of Alaska salmon fisheries through a well-being framework. Ecology and Society, 25(2), 18.

DRNA. (2010). Reglamento de Pesca de Puerto Rico. D.d.R.N.y.A.P. Rico., ed. 40:7949. San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Ellis, J., Friedman, D., Puett, R., Scott, G., & Porter, D. (2014). 2014 A Qualitative Exploration of Fishing and Fish Consumption in the Gullah/Geechee Culture”. The Publication for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, 39(6), 1161–1170. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s10900-014-9871-5

Field, R., Laboy, E., Capella, J., Robles, P. & González, C. (2008). Jobos Bay Estuarine Profile: A National Estuarine Research Reserve. Aguirre, PR.: Jobos Bay NERR.

Foale, S. (1999). Local Ecological Knowledge and Biology of the Land Crab Cardisoma hirtipes (Decapoda: Gecarcinidae) at West Nggela. Solomon Island. Pacific Science, 53(1), 37–49.

Fuller, S. Y. (2021). Indigenous Ontologies: Gullah Geechee Traditions and Cultural Practices of Abundance”. Human Ecology, 49(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-021-00215-2

García-Quijano, C., & Lloréns, H. (2017). What rural, coastal Puerto Ricans can teach us about thriving in times of crisis. Retrieved October 7, 2023 from http:// theco nvers ation. com/

what- rural- coast al- puerto- ricans- can- teach- us- about- thriv ingin-times-of-crisis-76119

García-Quijano, C., del Pozo, M., Griffith, D., Lloréns, Hilda., & Poggie, J. (2021). Coastal Forest Fisheries: A Study of Estuarine Forest Resource Dependency in the Southern Coast of Puerto Rico. Technical Report submitted to University of Puerto Rico Sea Grant (NOAA).

García-Quijano, C., Poggie, J., Pitchon, A., del Pozo, M., & Alvarado, J. (2013). The Coast’s Bailout: Coastal Resource Use, Quality of Life, and Resilience in Southeastern Puerto Rico. Technical Report Submitted to University of Puerto Rico Sea Grant (NOAA).

García-Quijano, C., Poggie, J., Pitchon, A., & Del Pozo, M. (2015). Coastal Resource Foraging, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in Southeastern Puerto Rico. Journal of Anthropological Research, 71(2), 145–167.

García-Quijano, C. G. (2006). Resisting Extinction: The Value of Local Ecological Knowledge for Small-Scale Fishers in Southeastern Puerto Rico Ph.D., Anthropology, University of Georgia.

García-Quijano, C. G. (2009). Managing Complexity: Ecological Knowledge and Success in Puerto Rican Small-Scale Fisheries. Human Organization, 68(1), 1–17.

García-Quijano, C. G., & Poggie, J. J. (2019). Coastal resource foraging, the culture of coastal livelihoods, and human well-being in Southeastern Puerto Rico: Consensus, consonance, and some implications for coastal policy. Maritime Studies, 19, 53–65.

García-Quijano, C. G., Poggie, J. J., & del Pozo, M. (2016). En el Monte También Se Pesca: ‘Pesca de Monte’, ambiente, subsistencia y comunidad en los bosques costeros del sureste de Puerto Rico. Caribbean Studies, 43(2), 115–144.

Giusti-Cordero, J. (1994). Labor, Ecology, and History in a Caribbean Sugar Plantation Region: Loíza, Puerto Rico 1770–1950, Sociology, State University of New York.

Giusti-Cordero, J. (2015). Trabajo y vida en el mangle: “Madera negra” y carbón en Piñones (Loíza), Puerto Rico (1880–1950). Caribbean Studies, 43(1), 3–71.

Glaser, M. (2003). Interrelations between mangrove ecosystem, local economy, and social sustainability in Caeté Estuary, North Brazil. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 11, 265–272.

Govender, Y. (2007). A Multidisciplinary Approach to Understanding The Distribution, Abundance, and Size of The Land Crab, Cardisoma Guanhumi, in Puerto Rico. University of Puerto Rico.

Grace-McCaskey, C., Griffith, D., Llorens, H., Garcia Quijano, C., & del Pozo, M. (2021). Negotiating Political and Moral Economies in the U.S. Caribbean after Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Caribbean Studies, 49(1):3–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/crb.2021.0010

Graeber, D. (2014). On the moral grounds of economic relations: A Maussian approach. Journal of Classical Sociology, 14(1), 65–77. Griffith, D., & Valdés-Pizzini, M. (2002). Fishers at Work, Workers at Sea: A Puerto Rican Journey Through Labor and Refuge. Temple University Press.

Griffith, D., Valdés-Pizzini, M., & García-Quijano, C. (2007). Socioeconomic Profiles of Fishers, Their Communities, and Their Reponses to Marine Protective Measures in Puerto Rico. Miami, FL: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Southeast Fisheries Science Center.

Griffith, D. C. (1999). The Estuary's Gift: An atlantic coast cultural biography (pp 196). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Griffith D. C., García-Quijano, C., Pizzini, M. V. (2013). A fresh defense: A cultural biography of quality in Puerto Rican fishing. American Anthropologist, 115(1), 17–28. Gutiérrez-Sánchez, J. (1982). Características Personales y de Trabajo de Los Pescadores en Puerto Rico. UPR Sea Grant Press, Mayagüez, PR.

Hamilton, L. S., & Snedaker, S. C. (1984). Handbook for Mangrove Area Management. Honolulu, Hawaii: Environment and Policy Institute, East West Center, IUCN/UNESCO/UNEP.

Harries, H. (1992). Biogeography of the coconut Cocos nucifera L. Principes, 36(3), 155–162.

Hicks, C., Levine, A., Agrawal, A., Basurto, X., Breslow, S., Carothers, C., Charnley, S., Coulthard, S., Dolsak, N., & Jamie, and Carlos Garcia-Quijano Donatuto, Michael Mascia, Karma Norman, Melissa Poe, Terre Satterfield, Kevin St.Martin, Phillip Levine,. (2016). Engage key social concepts for sustainability: Social indicators, both mature and emerging, are underused. Science, 352(6281), 38–40.

HyperRESEARCH. (2015). HyperRESEARCH 3.7.3. https://www. researchware.com/. Researchware, Inc.

Jackson, T. (2020). Wellbeing Matters—Tackling growth dependency. An Economy That Works Johnson, J. C. (1990). Selecting Ethnographic Informants (Vol. 22). Sage Publications.

Jones, A. (1985). Dietary Change and human Population at Indian Creek. Antigua. American Antiquity, 50(3), 518–536.

Kawarazuka, N., & Béné, C. (2010). Linking small-scale fisheries and aquaculture to household nutritional security: An overview. Food Secur., 2, 343–357.

Khakzad, S., & Griffith, D. (2016). The role of fishing material culture in communities’ sense of place as an added-value in management of coastal areas. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 5(2), 95–117.

Koenig, C. C., Coleman, F. C., Eklund, A. M., Schull, J., & Ueland, J. (2007). Mangroves as essential nursery habitat for goliath grouper (Epinephelus itajara). Bulletin of Marine Science, 80(3), 567–586.

Kubizewski, I., Costanza, R., Franco, C., Lawn, P., Talberth, J., Jackson, T., & Aylmer, C. (2013) Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress. Ecological Economics, 93, 57–68.

Kubiszewski, I., Zakariyya, N., & Jarvis, D. (2017). Subjective wellbeing at different spatial scales for individuals satisfied and dissatisfied with life. Peer Journal, 7, e6502.

Lloréns, H. (2021). Making Livable Worlds: Afro-Puerto Rican Women Building Environmental Justice:University of Washington Press. Lloréns, H., & García-Quijano, C. (2020) On Mobile Black Ecologies. Keynote Roundtable 2, POLLEN 2020: Contested Natures: Power, Politics, Prefiguration. Retrieved October 7, 2023 from https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZL9OKyVP7E

Lugo, A. (1988). The mangroves of Puerto Rico are in trouble. Acta Cientifica, 2, 124.

Márquez Pérez A. I. (2019). Acaparamiento de territorios marinos y costeros: Dos casos de estudio en el Caribe colombiano. Revista Colombiana De Antropología, 55(1), 119–152.

Mauss, M. (1954). The Gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. London, U.K.: Cohen & West.

Mumby, P. J., Edwards, A. J., Ernesto Arias-González, J., Lindeman, K. C., Blackwell, P. G., Gall, A., Gorczynska, M. I., Harborne, A. R., Pescod, C. L., Renken, H., Wabnitz, C. C. C., & Llewellyn, G. (2004). Mangroves Enhance the Biomass of Coral Reef Fish Communities in the Caribbean. Nature, 427, 533–536.

Nagelkerken, I., Blaber, S. J. M., Bouillon, S., Green, P., Haywood, M., Meynecke, J.-O., Kirton, L. G., Pawlik, J., Penrose, H. M., Sasekumar, A., & Somerfield, P. J. (2008). The habitat function of mangroves for terrestrial and marine fauna: A review. Aquatic Botany, 89, 155–185.

Nikolic, M., Bosch, A., & Alfonso-Melendez, S. J. (1976). A system for farming the mangrove oyster. Crassostrea Rhizophorae G. Aquaculture, 9(1), 1–18.

O’Neill, J. (2002). Ecology, policy and politics: Human well-being and the natural world. Routledge.

Poe, M., Levin, P., Tolimieri, N., & Norman, K. (2015). Subsistence fishing in a 21st century capitalist society: From commodity to gift. Ecological Economics, 116, 241–250.

Pollnac, R., Abbot-Jamieson, S., Smith, C., Miller, M., Clay, P., & Oles, B. (2006). Toward a model for fisheries social impact assessment. Marine Fisheries Review, 68(1), 1–18.

Pollnac, R., & Poggie, J. (2008). Happiness, Well-being and Psychocultural Adaptation to theStresses Associated with Marine Fishing. Human Ecology Review, 15(2), 194–200.

QSR. (2020). NVivo 13. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivoqualitative-data-analysis-software/home. QSR International.

Quijano, C. G., Poggie, J., & Del Pozo, M. (2016). En el monte también se pesca:" Pesca de monte", ambiente, subsistencia y comunidad en los bosques costeros del sureste de Puerto Rico. Caribbean Studies, 43(2), 115–144.

Quiñones-Llópiz, J., Rodríguez-Fourquet, C., Luppi, T., & Farias, N. (2021). Size distribution and sex ratio between populations of the artisanal harvested land crab Cardisoma guanhumi (Decapoda: Gecarcinidae), with the estimation of relative growth and size at sexual maturity in Puerto Rico. Revista De Biología Tropical, 69(3), 898–903.

Robertson, A. I., & Duke, N. C. (1990). Mangrove fish-communities in tropical Queensland, Australia: Spatial and temporal patterns in densities, biomass and community structure. Marine Biology, 104(3), 369–379.

Rodríguez-Fourquet, C., & Sabat, A. M. (2009). Effect of harvesting, vegetation structure and composition on the abundance and demography of the land crab Cardisoma guanhumi in Puerto Rico. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 17, 627–640.

Rondinelli, S., & Barros, F. (2010). Evaluating shellfish gathering (Lucina pectinata) in a tropical mangrove system. Journal of Sea Research, 64, 401–407.

Roque, A., Wutich, A., Brewis, A., Beresford, M., García-Quijano, C., Lloréns, H., & Jepson, W. (2021). Autogestión and water sharing networks in Puerto Rico after Hurricane María. Water International https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2021.1960103

Roque, A., Pijawka, D., & Wutich, A. (2020). The Role of Social Capital in Resiliency: Disaster Recovery in Puerto Rico. Risks, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 11, 204–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12187

Rouse, I. (1992). The Taínos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus. Yale University Press.

Seara, T., Pollnac, R. B., Poggie, J. J., Garcia-Quijano, C., Monnereau, I., & Ruiz, V. (2017). Fishing as therapy: Impacts on job satisfaction and implications for fishery management. Ocean & Coastal Management, 141, 1–9.

Smith, C., & Clay, P. (2010). Measuring subjective and objective wellbeing: Analyses from five marine commercial fisheries. Human Organization, 69(2), 158–168.

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. (2010). Mismeasuring our lives: Why GDP doesn’t add up: Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. The New Press.

Stoffle, B., Stoffle, R., & Van Vlack, K. (2020). Sustainable Use of the Littoral by Traditional People of Barbados and Bahamas. Sustainability, 12(11). MDPI AG: 4764. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su12114764

Stonich, S. (2000). The Other Side of Paradise: Tourism, Conservation, and Development in the Bay Islands. Elmsford, NY.: Cognizant LLC.

Sutton, M. Q. & Anderson, E. N. (2014). Introduction to Cultural Ecology: Altamira Press.

Treviño, M. (2022). The Mangrove is Like a Friend: Local Perspectives of Mangrove Cultural Ecosystem Services Among Mangrove Users in Northern Ecuador. Human Ecology, 50, 863–878. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10745-022-00358-w

Tsing, A. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

Valdés-Pizzini, M. (2006). Historical Contentions and Future Trends in The Coastal Zone: The Environmental Movement in Puerto Rico. In Beyond Sun and Sand: Caribbean Environmentalisms. S.a.B.L. Baver, ed. 44–64. New Brunswick, NJ.: Rutgers University Press.

Valdés-Pizzini, M. (2011) Una mirada al mundo de los pescadores en Puerto Rico: Una perspectiva global. Mayagüez, PR: Sea Grant & Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios del Litoral.

Vianna, G. M. S., Zeller, D., & Pauly, D. (2020). Fisheries and Policy Implications for Human Nutrition. Current Environmental Health Reports, 7, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-020-00286-1

Walters, B., Ronnback, P., Kovacs, J., Krona, B., Hussain, S., Badola, R., Primavera, J., Barbier, E., & Dahdouh-Guebas, Farid. (2008). Ethnobiology, socio-economics, and management of mangrove forests: a review. Aquatic Botany, 89, 220–236.

Zu Ermgassen, P. S., Mukherjee, N., Worthington, T. A., Acosta, A., da Rocha Araujo, A. R., Beitl, C. M., & Spalding, M. (2021). Fishers who rely on mangroves: Modelling and mapping the global intensity of mangrove-associated fisheries. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 247, 106975.

Publisher's Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.