The Sea Education Association (SEA), based in Woods Hole, MA, USA, offers ocean studies programs for undergraduate, gap year, and high school students.

The Sea Education Association (SEA), based in Woods Hole, MA, USA, offers ocean studies programs for undergraduate, gap year, and high school students.

This past summer, a group of students immersed themselves in one of the ocean’s most dynamic and threatened regions, the central Pacific, as part of a three-week seminar. Framed around the challenges facing Pacific Island nations, the seminar centered on the intersection of marine conservation, climate change, and science communication, offering students a unique opportunity to explore both the scientific and cultural dimensions of ocean health.

“SEA Quest” is a three-week online seminar for high school students. This summer’s program focused on the Pacific Ocean, marine conservation, and environmental communication. This magazine is the capstone of this seminar.

Throughout the course, students gained a multi-layered understanding of marine ecosystems and how they are being altered by human activity. They studied the latest scientific research on coral reef decline, learning how rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification are causing widespread bleaching and reshaping reef biodiversity. In tandem, they explored the science behind plastic pollution, both its sources and its long-term ecological consequences, as well as the complexities of proposed solutions like bans, recycling reforms, and emerging cleanup technologies. Guest lectures added additional layers of expertise and perspective Plastics researcher Dr. Kara Lavender Law introduced students to microplastic distribution studies and the modeling tools used to trace debris across ocean currents. Dr. Heather Page, a coral reef ecologist, discussed the vulnerability of reef systems and how localized protections can buffer against global stressors. Captain

of Pacific Island communities.

Current undergrad students Olivia Hines and Resh Mukherjee shared their experience of their study abroad voyage with SEA from Aotearoa New Zealand to Tahiti. They guided the students through the timelines of the program, and each presented their study topic, providing deep insight into their topics while giving the students a taste of college academics.

Students also engaged deeply with cultural perspectives on ocean stewardship. Writer and reef fisheries scientist Dr. Shreya Yadav, based in Hawai‘i, spoke on the traditional knowledge systems that guide sustainable marine use in Polynesian communities. Her session emphasized the importance of respecting and integrating Indigenous ecological knowledge into modern conservation policy, a recurring theme throughout the

seminar These discussions led students to reflect on the role of cultural resilience and local leadership in addressing the global climate crisis.

Her perspective helped students better understand the human dimensions of climate change and the resilience of Pacific Island communities.”

A particular focus of the course was on science communication With guidance from Rich King and senior editor Rebecca Kessler at Mongabay, students analyzed how marine science is reported and how language shapes public understanding of environmental issues. We examined examples of storytelling, from personal narratives to data-driven investigative pieces, and practiced translating technical content for a general audience. This skill-building exercise underscored that conservation isn’t just about data, but about conveying urgency and possibility in ways that resonate.

As part of the seminar, each student selected a recent peerreviewed scientific study related to the Pacific Ocean and transformed it into a piece of science journalism. This assignment challenged students to translate complex research into clear, engaging narratives for a general audience applying the communication strategies they had studied throughout the course. Topics

ranged from sperm whale vocal clans to threats for sea turtles, the effect of fisheries, and ocean microplastics, reflecting the diverse interests and growing expertise of the group

This issue of SEA Writer aims to inspire curiosity and deepen understanding of the Pacific Ocean by sharing stories that blend science, culture, and conservation Through student voices and expert insights, it highlights the region’s ecological richness and the urgent challenges it faces, encouraging readers to see the ocean not just as a vast expanse, but as a living, interconnected world worth protecting.

Caitlyn Sullivan

Vakarė Berankytė is an upcoming sophomore at Klaipėda Lyceum Living near the Baltic Sea, she is deeply aware of its pollution and is determined to make a difference. Passionate about marine conservation, she hopes to one day volunteer with organizations dedicated to protecting the world’s oceans and their marine life, while inspiring the next generation through working with children.

Abdellah Bouberima is a high school student in Sėtif, Algeria, completing both the Algerian Baccalaureate in Mathematics and the French Baccalaureate with a specialization in History, Geography, Geopolitics, and Political Science. He is a Junior Reporter at Youth Journalism International and a Yale Young African Scholar Abdellah is the founder of the Sėteifan Model United Nations.

Amaya Gray is an incoming freshman at Bronx High School of Science in NYC. She is extremely passionate about biology and astronomy She hopes to one day travel the world and go to space

Caitlyn Sullivan is a upcoming senior at Woodinville High School, WA. She is passionate about animal conservation and research. She hopes to revisit Mongolia and learn more languages

Bess Van Slyke is an upcoming senior at Austin High School, TX, who is passionate about cheerleading and marine biology She grew up along the Gulf of Mexico which sparked her love for the ocean! She hopes to travel and scuba dive all over the world when she is older.

Penelope Wainwright is an upcoming high school junior at Springside Chestnut Hill Academy, PA. She has a passion for marine life and illustration and hopes to one day travel outside of the East Coast to see the beaches of the world!

Liya Murdoch is an upcoming senior at Stuyvesant High School in NYC. She is extremely passionate about coral reefs and gymnastics. She hopes to try scuba diving and skydiving.

Saydee Westman is a upcoming homeschooled senior in high school on Long Island, NY She is extremely passionate about conservation and writing. She hopes to one day visit the cloud forests of Papua New Guinea that first inspired her love of wildlife!

"Introduction” essay by Caitlyn Sullivan pp. 4-6

Author biographies by editors p 7

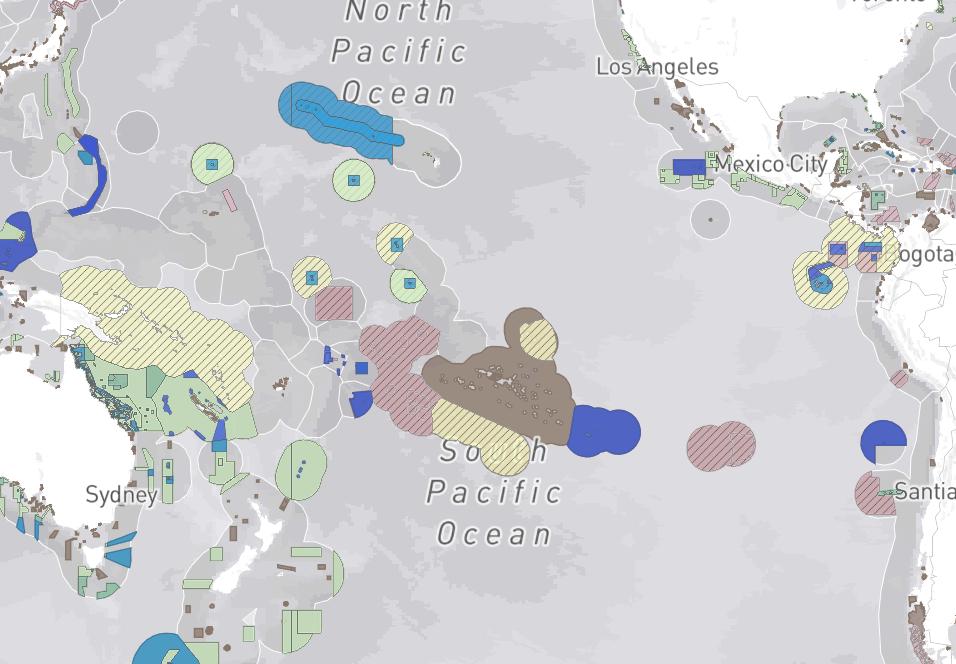

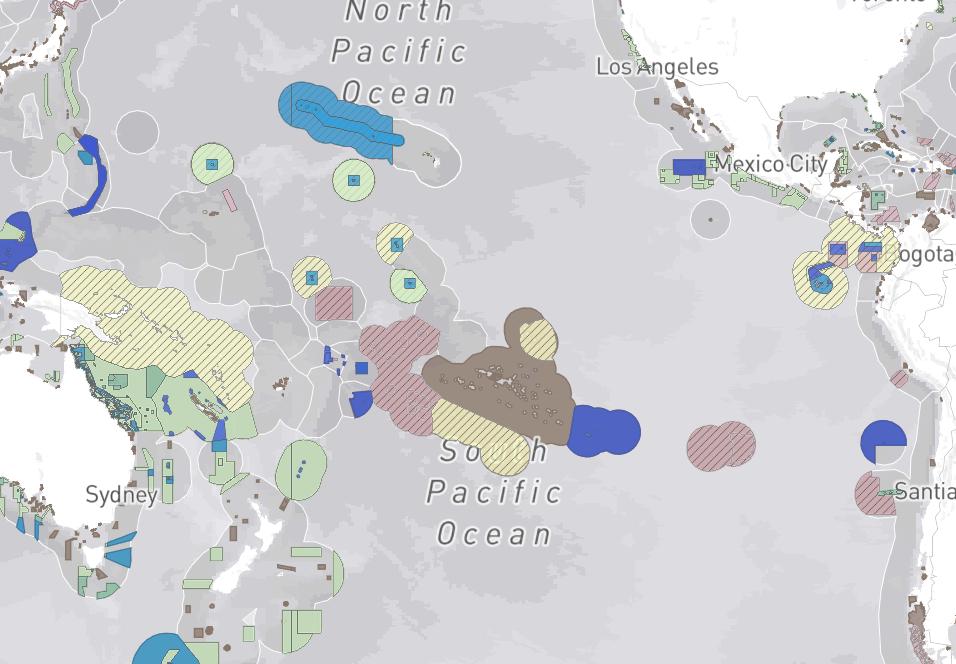

“Pacific Ocean” map by Penny Wainwright pp. 10-11

“Before It’s Lost: Island Knowledge That Could Shape Climate Resilience”

“Guano Saves the Reef: Inside the Radical Restoration Efforts Bringing Birds and Balance Back to the Chagos Archipelago”

“Analysis and Discovery of Pollutants in Pacific Ocean Sharks”

“Tracking dFAD Threats to Sea Turtles”

“Through a Turtle’s Eyes”

“Baleen Whales: The Connector of the Ocean”

science journalism by Amaya Gray pp. 12-14

science journalism and art by Penny Wainwright pp. 15-18

science journalism and art by Liya Murdoch p. 19-22

science journalism by Vakarė Berankytė pp. 23-25

fiction by Vakarė Berankytė pp. 26-27

science journalism by Saydee Westman pp. 28-31

“Most of the world's whale populations...” poem by Saydee Westman p. 32

“Where Pacific Fisheries Overlap”

“The Role of El Niño in Rising Global Temperatures in 2023"

“The Faceted Sides of Sperm Whale Conservation”

science journalism by Bess Van Slyke pp 33-35

science journalism by Abdellah Bouberima pp. 36-39

science journalism and art by Caitlyn Sullivan pp. 40-44

“Behind the Scenes: Meet Our Guest Speakers”

“What We Can Do about the Health of the Pacific Ocean and Its People”

“When the frigate birds fly inland, we know a cyclone is coming.”

This is a saying that has been passed down by the people of Tonga for generations. The interesting thing is that this wasn’t just a story; it was a real warning sign. Like a natural warning system, known to scientists and islanders alike as traditional knowledge, or TK.

Dr Patrick Nunn, based at the Australian Centre for Pacific Islands Research and the lead author of this work by a large international team, compiled past research, stories, and cultural traditions regarding the Pacific Islands for their study: “Traditional Knowledge for Climate Resilience in the Pacific Islands” (published in WIREs Climate Change in 2024) The purpose of this paper is to explain how TK helps island communities withstand climate change, and why it should no longer be ignored.

Pacific Island communities (such as Fiji and Vanuatu) have been around for more than 3,000 years. They have had to deal with many climate disasters: giant storms, rising seas, floods, droughts, etc , and have done so without any modern technology. Instead, they

by Amaya Gray

have observed nature and learned from their past experiences. However, over time, their knowledge has been mostly ignored, mostly by Western governments, but also by the communities that it came from. During the era of colonization, Western peoples began disregarding TK as unscientific and too “old-fashioned.” Many modern climate plans still don’t incorporate any TK. Instead, they refer to outside resources (experts, models, tools, etc ) that may not be suitable for the local land and culture.

This paper argues that that was a grave mistake, as TK has allowed island communities to survive and adapt to climate change for centuries.

To explain how this Pacific TK works, the authors divided it into 3 “tiers”:

1 Direct Climate Information – For example, being able to tell that a storm is coming based on behavioral changes in birds, bugs, or plants.

2 Survival – For example, learning how to grow food during droughts or how to build houses strong enough to withstand powerful storm winds.

3 Other Traditional Knowledge – It may not be directly about the weather, but still matters for climate resilience.

Dunn and his team offer two examples of traditional knowledge at play:

by Amaya Gray

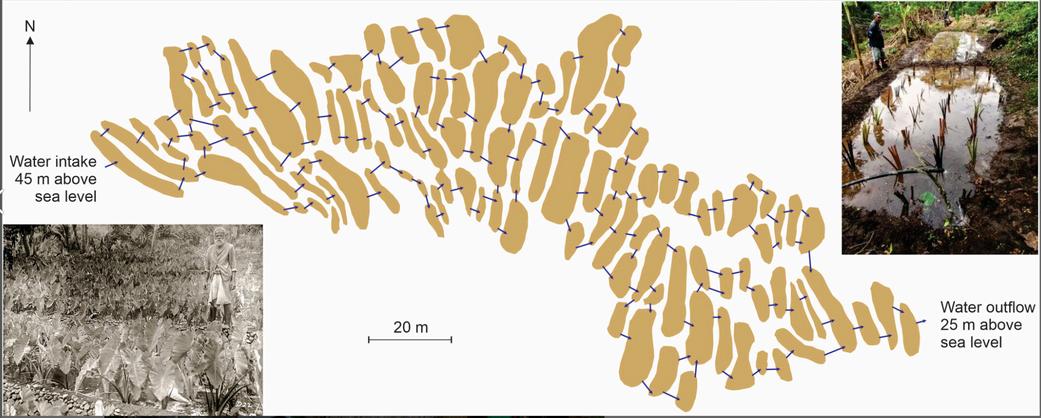

Taro Terraces in Fiji. These are like small garden systems that collect water and help grow food when there is a drought. They also help slow/stop erosion.

Cyclone Houses in Vanuatu. These are traditional round houses made primarily of thick thatch and wood, which allows them to bend, instead of breaking, when faced with strong winds.

Dunn and his team also mention a few natural signals, such as frigate birds flying inland means a storm might be coming; and breadfruit trees fruiting heavily right before extreme weather All of these things had to be learned through generations of observing nature.

E pala le ma’a, ‘ae lē pala le tala. Stones decay, but stories do not.”

The authors put a lot of stress on the fact that TK should be preserved and respected, as it is useful, now more than ever. For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic, many island communities returned to more traditional methods of farming and water collection when they noticed other systems breaking down, and it was effective

However, this knowledge is vanishing. Fewer and fewer young people are taught about it, and the older generations that have this knowledge don’t always have an opportunity to pass it on.

In the paper, Dr. Nunn says: “We’re at a turning point. If we don’t act now to document and support traditional knowledge, we may lose it forever.”

According to another expert (not connected to the research), Dr. Singh, TK is more than facts it is identity, culture, and survival. In the end, the paper makes a

by Amaya Gray

strong point: people are so busy searching for new and innovative climate solutions, while some of the best ones have been trusted and tested for thousands of years.

In the paper, they share a Samoan proverb that seems to perfectly this idea: “E pala le ma’a, ‘ae lē pala le tala.”/“Stones decay, but stories do not”—a reminder that traditional knowledge, once dismissed, may be the key to our survival.

Patrick D Nunn, Rani Kumar, Fane Areki, Eloni Bulehite, Teresia V. Areki, Suliana Faupula, and Joseph Kuridrani, “Traditional Knowledge for Climate Resilience in the Pacific Islands ” WIREs Climate Change e871 (2024): doi.org/10.1002/wcc.882.

James D Ford, Lea Berrang-Ford, Tristan Pearce, Frank Duerden, and Barry Smit, “Climate Change Policy Responses for Canada's Inuit Population: The Importance of Adaptive Capacity ” Global Environmental Change 20, no 1 (2010), pp 177–191. www.sciencedirect.com.

The cycle of life within island ecosystems is a subject of enduring fascination in the scientific world. Small ecological changes can trigger cascading effects across habitats. One powerful example of this lies in island restoration. Could the recovery of a series of islands not only boost seabird populations but also enhance coral reef resilience in the face of a warming climate? This was a question that fascinated seabird ornithologist Dr.

Ruth E. Dunn, who specializes in birds like terns, boobies, and puffins, and her team of coral experts, while they were investigating the benefits of island restoration in the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean.

Seabirds are a geographically isolated taxa, meaning a group of related animals, and one of the most threatened as their island homes deteriorate. Breeding grounds are relied upon heavily to sustain population numbers but will not function correctly if there is not a sufficient amount of prey. As the islands and their reefs are impacted

by Penny Wainwright

by Penny Wainwright

populations increased with the intake of guano-derived nitrogen, and when dissolved into coral and zooxanthellae, that nitrogen wildly enhances their health and growth.

The way Dunn’s research team has acted in the Indian Ocean has proven quite common with other research groups. When this study was published in 2023, researchers on over 1,000 islands have since attempted invasive mammal eradications with very successful resu s. Dunn and her colle that “in com other restoration actions, such as native species translocations, [eradications] have aided the recovery of hundreds of native island taxa worldwide.”

In New Zealand, these same efforts have led to restored seabird populations, guano-fertilized nearshore marine habitats after seabirds return, and increased macroalgal diversity. When removing rats from islands in the Indian Ocean, teams have gotten overwhelmingly positive results in higher nitrogen isotope values, faster fish growth rates, and differing benthic community structure in comparison with those where rats have decimated seabird populations

Nutrient-rich seabird guano fertilizes the tropical seas and land, which without it are nutrient-poor.”

The presence of rats on islands lessens the possibility of birds like the lesser noddy, sooty tern, and red-footed booby returning to breeding grounds. The islands in the Indian Ocean that the team researched with rats had a higher probability of hosting zero pairs of seabirds at breeding areas than islands without rats. Now knowing the pros of seabird guano, the team understands they need the rats eradicated.

Seabird guano enters adjacent nearshore marine ecosystems as fertilizer via direct defecation and groundwater discharge. And while human activity will increase the susceptibility of corals to bleaching, seabird-derived nutrients will deliver ratios of nitrogen and phosphorus that are widely beneficial to coral physiology. Healthy coral, in turn, boosts the fish populations. More fish spawn and are drawn to healthy reefs, and Dunn’s team found that cont'd >

the fish species that can be found in the Chagos Archipelago help the reef’s good health remain on track. Parrotfish, in particular, are grazers that keep harmful algae off the coral, allowing it to thrive and grow. Parrotfish are a taxa that is essential to these reefs, but will not return to them until the seabirds return to the skies.

Island restoration is essential, it’s clear, because the researchers have proved it boosts the seabird populations wildly. Seabirds are the keystone to the cycle of life on islands, and as gross as it might sound, their poop restores the beauty to the Indian Ocean, bringing green back to land, colors back to our coral, and fish back to the waters.

I had the privilege of being able to interview Dr. Dunn on this study, and she felt that the articles she and her team have put out “have been quite well received.” Island restoration is an expensive project,

by Penny Wainwright

so she is very happy that the response from contributors has been overwhelmingly positive, and they receive the financial support they need. However, just knowing about the importance of island restoration and taking action to bring attention to the vitality of seabirds can help drive this movement forward. Because when the seabirds return, so does island life, and every voice that spreads their story brings us one step closer to restoration.

R E Dunn, et al “Island Restoration to Rebuild Seabird Populations and Amplify Coral Reef Functioning.” Conservation Biology 39, e14313 (2025): doi.org/10.1111/cobi.14313.

M Philippe-Lesaffre, et al “Recovery of Insular Seabird Populations Years after Rodent Eradication.” Conservation Biology 37, e14042 (2023): doi org/10 1111/cobi 14042

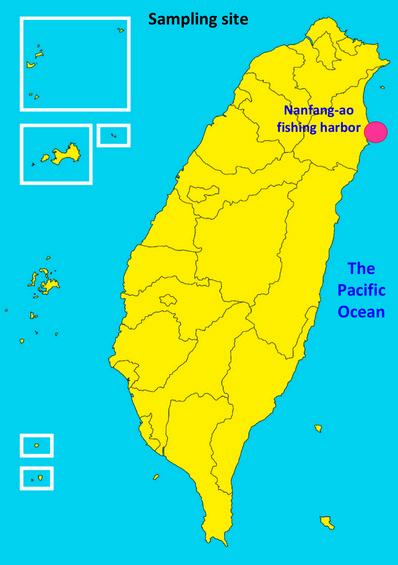

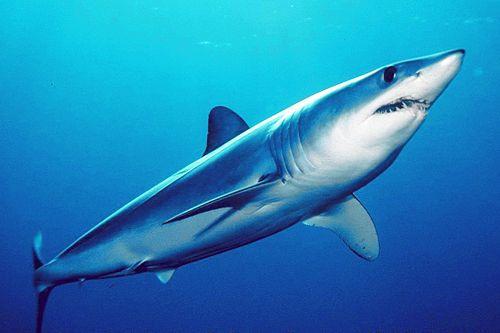

In the Pacific waters, a shark glides through currents hidden with microscopic threats Invisible to the eye, these pollutants accumulate inside one of the ocean’s most powerful creatures. What happens when top oceanic predators become victims of human waste?

A recent study has examined just this problem. Lead researcher MingHuang Wang and his team dive into the contamination crisis quietly unfolding in sharks. Their research reveals how microplastics and phthalate esters are reshaping marine life from the inside out.

Wang and his team decided to focus on multiple species of sharks at a time, compared to previous studies, which only focused on one. This study also integrates the analysis of microplastics (MPs) and phthalate esters (PAEs), underscoring the relationships of different pollutants in marine organisms. The research team wrote that, “Addressing the sources of these pollutants, understanding their distribution and impact, and implementing effective management strategies are critical steps toward

by Liya Murdoch

preserving marine ecosystems and ensuring the health of marine organisms and humans.”

MPs and PAEs in marine environments are a severe threat to sharks as they cause biological disturbances and affect their survival. This can disrupt entire ecosystems due to sharks' role as a top predator.

The irresponsible disposal of trash into oceans leads to the degradation of plastics, creating many microparticles called

the urgent need for better pollution management and conservation.

Sharks serve as valuable species that provide us with significant insights into oceanic plastic pollution and its impact on marine ecosystems.”

Sharks serve as a valuable species that provides us with insights into oceanic plastic pollution and its contamination in marine ecosystems Plastics can serve as carriers for PAEs by transferring them into marine organisms. PAEs are extremely harmful to marine organisms, as they disrupt the endocrine system The disruption of this system can lead to reproductive

by Liya Murdoch

and developmental issues

Wang and his six colleagues sought to find the severity of human activities on top oceanic predators by investigating MPs and PAEs in a variety of different shark species Their findings demonstrated the prevalent contamination in at least one location of Pacific Ocean sharks. Fishing vessels in the Eastern waters of Taiwan caught twelve sharks for the study. The researchers recorded each shark's gender, length, and weight. This study had limited application due to its single location and focus on only a few shark species.

To analyze microplastics in the stomachs of the sharks, Wang and his team transferred the stomach contents of each shark into individual beakers and

Plastic particles found in the sharks ranged from two to thirty-one particles. The researchers found that the majority of microplastics ingested by the sharks were blue fibers They also observed a large variety of MPs, indicating the complexity and diversity of MPs in sharks. Approximately two million fibers are discharged into marine ecosystems each year, many of which are from synthetic textile products. These fibers are easily ingested by smaller organisms and can move up the food chain to harm a wide variety of marine life Plastic fibers can even pass through the gills of marine organisms.

The researchers found PAE concentrations in all sharks and learned that the total concentration

collected the microplastics. The researchers cataloged the characteristics of each particle To measure PAEs in shark stomach tissue, the researchers prepared, purified, and analyzed the stomach samples.

Wang and his team found MPs in the stomachs of all twelve sharks.

by Liya Murdoch

was the highest in the sharks compared to any other fish. The most common PAEs found were DEHP and DiNP, which are commonly used in plastics These chemicals can affect the nervous system and cause inflammation. The team found that sharks are exposed to plastic pollutants mainly through their diet. Surprisingly, they also found no significant correlation

between the MP and PAE levels

Wang and his team gained exciting insight into the diversity of microplastics. The team also developed an understanding of the specific types, colors, shapes, and other characteristics of microplastics found in sharks.

The researchers noted that plastics enter the ocean through many diverse sources, stating that, “The lack of a significant correlation between MPs and PAEs indicates nuanced exposure pathways.” This study reveals the alarming levels of pollutants in sharks, highlighting the urgent need for conservation strategies. Leading the charge are Pacific Island nations, which are employing strategies such as creating shark sanctuaries and marine protected areas. Furthermore, many individuals and corporations are working on reducing their plastic consumption and pollution

“Protecting Sharks in the Pacific ” The Pew Charitable Trusts (March 24, 2015): www pewtrusts org

Max Scheiner, “The Mega Impact of Microplastics: The Reality of the ‘Great’ Pacific Garbage Patch ” Common Home (April 17, 2024)” commonhome georgetown edu

Wang, Ming-Huang, Chih-Feng Chen, Yee Lim, Frank Albarico, Wen-Pei Tsai, Chiu-Wen Chen, and Cheng-Di Dong “Microplastics and Phthalate Esters Contamination in Top Oceanic Predators: A Study on Multiple Shark Species in the Pacific Ocean ” Marine Pollution Bulletin 206 (September 2024): 116769 doi org/10 1016/j marpolbul 2024 116769

by Liya Murdoch

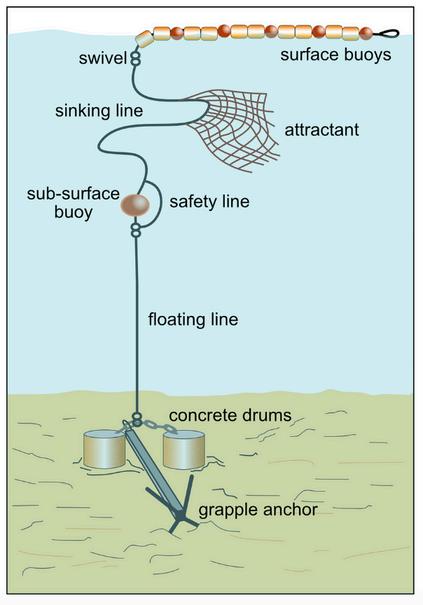

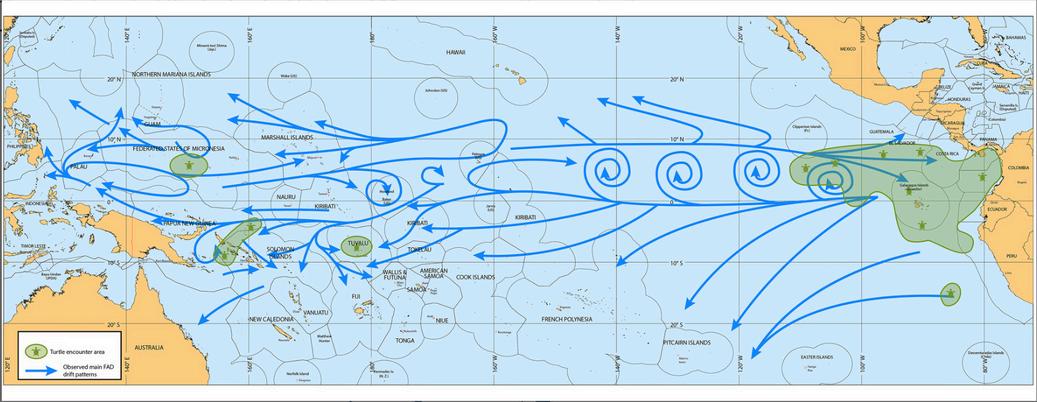

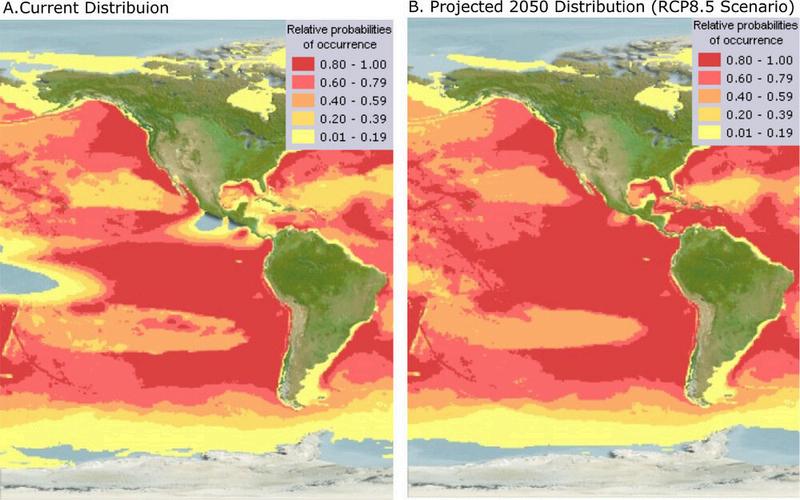

Every year, tens of thousands of Fish Aggregating Devices (dFADs) are released into the Pacific Ocean. These floating rafts, made of bamboo, buoys, and netting with tails that can extend up to fifty meters below the surface, are widely used in the multi‐billion‐dollar tuna fisheries. But a recent study, published in Conservation Biology, shows that many of these dFADs are silently drifting into the critical habitats of endangered leatherback and hawksbill sea turtles.

The research, led by Lauriane Escalle of the Pacific Community’s

Oceanic Fisheries Programme, combined large‐scale ocean simulations with fisher knowledge to map dFAD drift. The results revealed that up to sixty percent of dFADs released in equatorial regions could enter essential turtle habitats, including nesting beaches and key foraging zones. Leatherbacks have suffered population collapses of over eighty percent in the Pacific, with some groups shrinking by about five percent annually since the 1980s. Hawksbills, once targeted for their shells, are now classified as “Critically Endangered” by the IUCN, with some Pacific nesting sites recording fewer than 100 nests each

g y sea turtles entangled in the submerged appendages.”

Since real‐world drift data is scarce, the team ran Lagrangian

simulations of more than eight million virtual FADs across Pacific currents. They tested two scenarios: one assuming widespread deployment across the tropical Pacific, the other reflecting current fishing practices.

This makes dFADs efficient tools for industrial fishing, yet also dangerous magnets for non‑target species.”

by Vakarė Berankytė

Even under present‐day patterns, a significant percentage of dFADs entered key leatherback foraging grounds, and high connectivity was seen with nesting zones in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands.

To validate their models, researchers interviewed forty-seven experienced tuna fishers from Ecuador, Spain, and Croatia, who had worked with dFADs for decades. These fishers provided maps of drift patterns and turtle encounters that closely matched the model predictions “The areas of interactions described by fishers were broadly similar to the ones we identified in the literature and with expert opinion,” the authors report. However, actual entanglement rates remain largely unknown, as abandoned dFADs drift unmonitored for months or even years, often washing ashore as marine debris.

Escalle’s team, made up of fisheries scientists and

oceanographers from institutions including NOAA and the University of New South Wales, urges urgent action: phasing out entangling designs, adopting biodegradable materials, and imposing spatial restrictions to keep dFADs away from turtle habitats. They warn that “nonentangling and biodegradable dFADs could still arrive in turtle zones so other management options could also be considered.” With up to 65,000 dFADs deployed annually in the Pacific alone, their plastic components also contribute significantly to marine pollution. This research is a reminder that protecting endangered species isn’t just about banning harmful practices it’s about rethinking tools we already use. Without better oversight, thousands of dFADs will continue to drift through the open ocean, quietly threatening species already teetering on the edge.

by Vakarė Berankytė

L Escalle, et al “Simulating Drifting Fish Aggregating Device Trajectories to Identify Potential Interactions with Endangered Sea Turtles Conservation Biology 38, no 6, e14295 (2024): doi org/10 1111/cobi 14295

NOAA Fisheries, “Leatherback Turtle Profile”: www fisheries noaa gov

The Ocean Cleanup, “Marine Debris”: theoceancleanup com

The sun burns bright overhead, but ahead of me a patch of shade drifts lazily with the current. It’s a strange shape, not like the floating logs or seaweed I sometimes find shelter beneath. Tiny fish dart through it, feeding on the green fuzz that clings to its belly. More fish swarm in, each chasing the one below it. The shadow seems alive with food, a little oasis in the endless blue. I circle closer, cautious yet hungry, unaware of the danger hanging just out of sight.

I push my way out of the warm sand, leaving the nest behind as moonlight guides me to the sea. The first wave lifts me, weightless for the very first time. I swim on instinct alone, the wide Pacific stretching endlessly ahead There are no paths, no markers only currents to carry me toward the promise of food and safety, somewhere far beyond the horizon.

by Vakarė Berankytė

A sudden tug yanks me backward. I twist and kick, but something tightens around my flipper Panic rises as I thrash, only to feel more lines catch on my shell. I pull harder but the harder I fight, the more the lines dig in. Above me, the floating shadow drifts on, indifferent, its nets swaying in the current like silent traps waiting for the next victim.

Waves push me onto a quiet beach scattered with ropes, nets, and plastic. I slip free from the last pieces of tangled line, but the sand is full of more debris. I rest, tired but alive, wondering how many of us ever make it back to the open sea and how many are lost to these drifting traps

I am one turtle among many, part of a lineage older than mountains. For millions of years, our kind has crossed the world’s oceans But now the waters are full of floating hazards. If we act with care, the paths we follow can remain safe for generations to come.

by Vakarė Berankytė

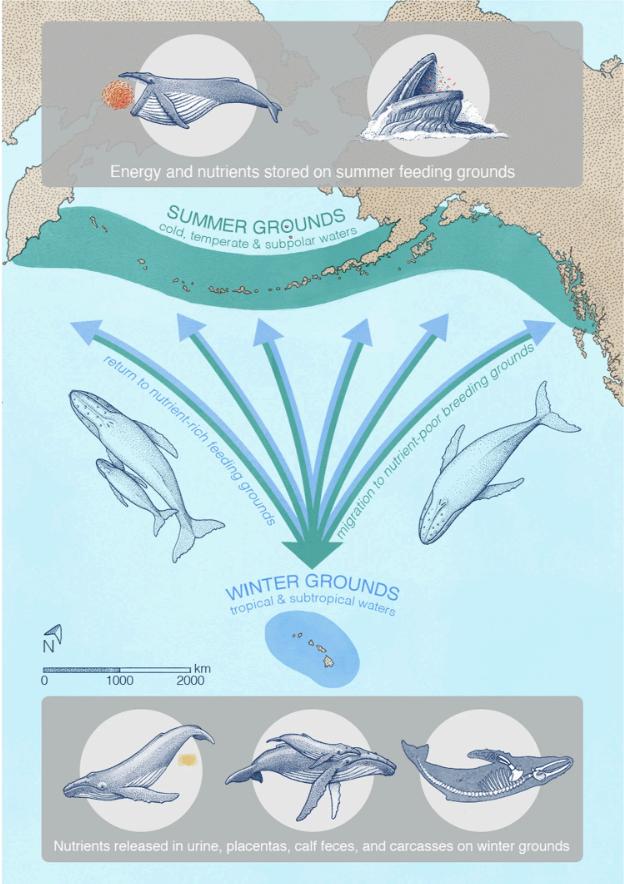

We often think of plants as the lungs of the planet, these (long distance migratory animals) operate like the circulatory system. -Joe Roman

You wouldn't think that whale excrement could ever become fascinating, but this year Joe Roman, a conservation biologist, and his colleagues managed to accomplish just that by publishing a study examining the nutrient output from baleen whales.

When baleen whales migrate they transport nutrients from high latitude feeding grounds to lower latitude tropical and subtropical winter grounds, connecting distant ecosystems Determined to explore just how important these whales are to the oceans they argue that “baleen whales provide the largest long distant nutrient subsidy on the planet,” and “Even an individual whale can have a substantial impact on the breeding grounds.”

The team decided to include five baleen whale species: humpback whales, gray whales and southern, North Atlantic, and North Pacific

by Saydee Westman

right whales All of these species have clear and regular annual migratory patterns. The researchers have called their journey “The Great Whale Conveyor Belt.” However, there are variations in this migration. For example, they currently believe that males and infertile female whales do not migrate to the breeding grounds. In addition to this, mothers and calves will have a more restricted migration in order to preserve energy and avoid predators.

Nutrient subsidies are the transportation of nutrients across different ecosystems. The group of scientists used spatial data to track the amounts of nutrients such as nitrogen (primarily from the urine of

by Saydee Westman

and supplies nutrients to the deep sea community. Scientists believe that these nutrients potentially play a major role in the ocean’s carbon cycle.

multiple assumptions or simplifications.”

Roman and his team used publicly available data that had spatial data as well as aerial and sea sightings from surveys to gather information on the whales. The team of researchers focused on multiple well known breeding and feeding grounds to collect these data In addition to this, they modeled the high and low latitude grounds using multiple observations, adding an additional fifteen degrees latitude to account for migration This gave the researchers a close estimate to the number of nutrient subsidies given off by the whales.

However, even the team admits that their results have “considerable uncertaint ” and “Any global analysis of thi ing past and prese ws, requires

To give an example of this, the group realizes that their study does not include every breeding ground and therefore does not include all of the nutrient results. They assumed the sex ratio was 50:50 in the calves produced and since males and females present different levels of nutrients this also changes the results. The group also used the same body mass and placenta weight for all adults and used slightly uncertain estimates to find their population size and which females were pregnant/nursing. The placenta protein percentage was also an assumed estimate using the human placenta as a reference.

The group of scientists used spatial data to track the amounts of nutrients such as nitrogen and carbon that comes from carcasses, placentas, and urine.”

Joe Roman and his team hope that future research will be done, such as including other baleen whale species in the study, the collection of more “direct measurements of the impact of migratory whales on chlorophyll-a concentration,” which is defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as a measure of the amount of algae and cyanobacteria growing in a water body Further understanding of the whale’s protein

catabolism (how they break down protein) will also be helpful to future research. When asked about his next steps in migration baleen whale research Roman told me: “We can estimate how much nitrogen goes into these systems (the ecosystems the whales interact with), but can we follow that nitrogen through the algae and the phytoplankton into the fish or into the coral reefs?”

Roman explained that they next want to look at these higher populated areas of baleen whales analyzing the phytoplankton, coral, and zooplankton to see if they contain nitrogen from distant areas the whales have migrated from and how much.

In conclusion, even though more work is needed to fully understand the complexities of baleen whale migration and its nutrient movement, Joe Roman’s team has provided great insight into the importance of whale migration and how they positively impact and connect distant marine ecosystems.

Sadly, due to previous commercial whaling, whale populations have plummeted. Thanks to persistent conservation efforts since the 1970s, whales have been rebounding, however, a study in 2019 suggests that after 2050 humpback whale populations will decline due to climate change. This decline will undoubtedly have a negative impact on the world, because going with the whales are

their nutrients, the connection between oceans, and the gear that makes everything keep turning.

by Saydee Westman

Rohan Chakvartay, “The Great Whale Conveyor Belt (Cartoon) ” MongaBay (May 13, 2025) news mongabay com

Uko Gorter, Illustrated images of each baleen whale species ukogorter com

Joe Roman, et al., “Migrating Baleen Whales Transport High Latitude Nutrients to Tropical and Subtropical Ecosystems ” Nature Communications 16, no 2125 (2025): doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56123-2.

Southwest Fisheries Science Center, “Why Do Whales Migrate? They Return To The Tropics To Shed Their Skin, Scientists Say,” NOAA Fisheries (2022): www fisheries noaa gov

Vivitskaia Tulloch, et al “Future Recovery of Baleen Whales is Imperiled by Climate Change.” Global Change Biology 25, no 4 (2019): 1263-81 doi/10 1111/gcb 14573

“Most of the world's whale populations remain depleted since the advancement of commercial whaling.”

- Joe Roman, et al. 2025

Taking, taking, taking the whales leave, not by choice, not by fate leaving by fate would be a whale closing its eyes falling softly to the sea floor giving its body to its village no, these whales leave by force never to sea the ocean again never to produce a next generation of whales to grace the waters, and supply the village village of reef and deep sea ecosystems village of the small, the phytoplankton and seemingly invisible fueling, feeding, nourishing these creatures need the whales but their resources sink sinking with the death of each gentle giant as we keeptaking, taking, taking.

Author’s Note:

Even though commercial whaling was for the most part banned in 1986, we still have to come to the harsh reality that most of the damage was already done, and now with many whale populations significantly reduced, especially the North Atlantic right whale with only about 370 individuals left, it is now our time to act If you're interested in contributing to conservation efforts to help save these whales Joe Roman recommends supporting the New England Aquarium’s Right Whale research.

by Saydee Westman

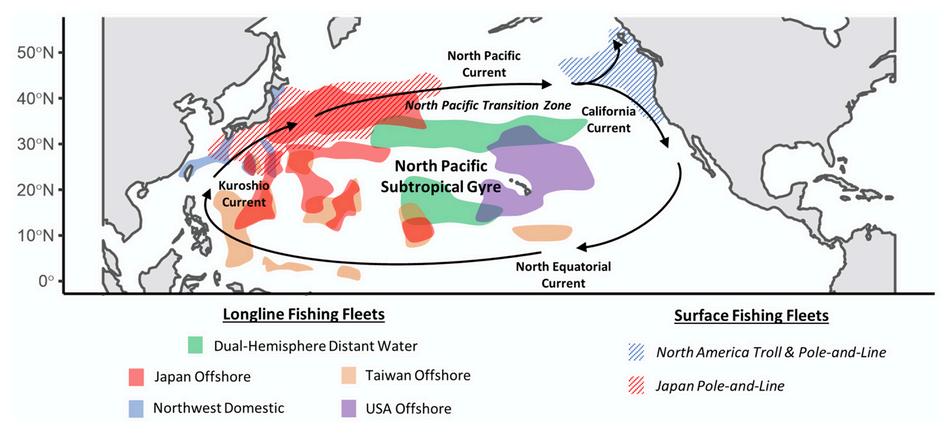

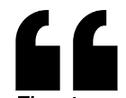

any forces govern the Pacific seas, where human activity, ocean events, and ecological relationships meet to control the overlap and interactions of fishing fleets. However, this balance is in trouble as a result of people not understanding the factors that control it. Without understanding these factors, we limit our ability to manage, and work to conserve species that live in the Pacific Ocean, such as the albacore tuna.

This report explores the factors that influence how these fisheries overlap and interact across the Pacific, revealing the temporary and highly influenceable nature of them. The results of this article call for more research on these factors so that the fisheries can be managed in ways that consider them. A research team led by Timothy H. Frawley explains this limited knowledge of how to effectively govern the tuna and other species: “The management and conservation of tuna and other transboundary marine species have to date been limited by an incomplete understanding of the oceanographic, ecological and socioeconomic factors mediating

fishery overlap and interactions, and how these factors vary across expansive, open ocean habitats.”

Prior to this article being written, it was known that the overlap and interactions of fisheries in the Pacific was affected by many factors, such as ocean conditions. However, how these factors affected this was unknown. This study is therefore trying to answer the question of how these factors influence the overlap of fisheries. Specifically tuna fisheries as well as those of other species in the Pacific, date back thousands of years. The study in this article takes place in the Pacific Ocean, which is the largest and deepest of the five oceans on Earth, and is known for its high biodiversity

by Bess Van Slyke

species distribution models, which predict the distribution of albacore tuna based on different factors. With these methods, the researchers conducting this study were able to find that these factors such as habitat preference, ocean conditions, and fishing gear types caused the overlap of activities across different fisheries to fluctuate and vary over time due to the prevalence of these factors

Factors such as habitat preference, ocean conditions, and fishing gear types caused the overlap of activities across different fisheries to fluctuate and vary over time.”

They explain “We find that fishery overlap varies significantly across time and space as mediated by: (1) differences in habitat preferences

by Bess Van Slyke

between juvenile and adult albacore; (2) variation of oceanographic features known to aggregate pelagic biomass; and (3) the different spatial niches targeted by shallow-set and deep-set longline fishing gear."

The results found in this study are important as they show how these factors, like habitat, ocean conditions, and human activity, influence how different fisheries interact and overlap while catching fish such as albacore tuna in the Pacific Ocean. Learning about this is important as it impacts how we understand and manage fish stocks, specifically in things such as harvest rotation.

T H Frawley, et al “Dynamic Human, Oceanographic, and Ecological Factors Mediate Transboundary Fishery Overlap Across the Pacific High Seas ” Fish and Fisheries 25, no 1 (2023): pp 60–81 doi org/10 1111/faf 12791

Fisheries, NOAA “Pacific Albacore Tuna | NOAA Fisheries ” NOAA, 22 May 2021, www fisheries noaa gov/species/pacificalbacore-tuna.

by Bess Van Slyke

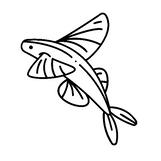

The year 2023 recorded a significant and alarming rise in global temperatures, catching worldwide researchers’ and policymakers’ attention. Although all agree that long-term climatic changes are mostly due to greenhouse gases caused by human activities, episodic natural climatic variabilities largely contribute to global patterns of temperatures, too Among these natural variabilities, the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) plays a central role through episodic fluctuations in atmospheric and oceanic temperatures in the equatorial Pacific, subsequently

having great impacts on global-scale climate and weather systems.

The Pacific Ocean plays a central role in the dynamics of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation and is home to some of the Earth’s most diverse and sensitive ecosystems. Societies living in Pacific Islands with deep relationships with the ocean for cultural, economic, and culinary reasons are especially sensitive to the consequences of climate change. Understanding the role of El Niño in amplifying increases in temperatures in the past few decades will help in developing effective measures for ocean conservation and communicating the need to combat these issues.

by Abdellah Bouberima

The 2023 Global Warming Spike and ENSO’s Role

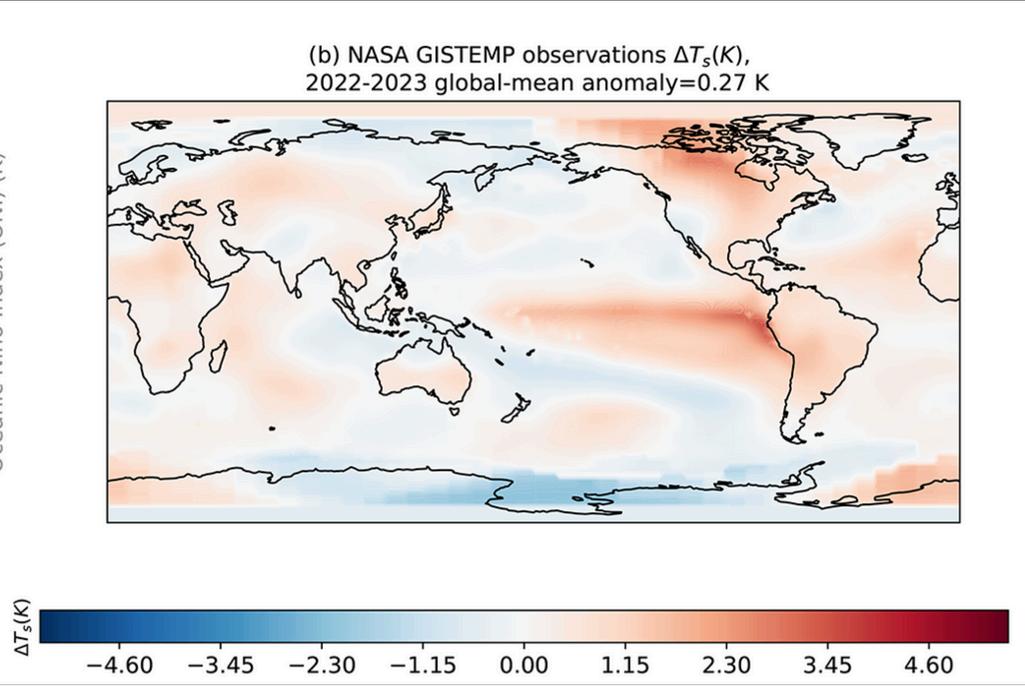

Raghuraman et al. (2023) confirm that the unusually high temperatures recorded in 2023 are largely due to the onset of a strong El Niño event. When referring to the periodicity of El Niño events, reference is made to the relaxation of trade winds to enable the progression of the cold waters, usually resident in the eastern Pacific, to migrate to the east and subsequently cause a temporary rise in global near-surface temperatures. One figure from their study clearly shows that 2023’s global mean surface temperatures rose nearly 0 2°C higher than the average for previous El Niño years. This illustrates how human-driven greenhouse gas emissions have raised the baseline temperature of the planet, meaning El Niño events now occur in an already warmer world. Consequently, their impacts are magnified, exacerbating heat extremes, coral bleaching events, and disruptions to marine ecosystems.

The combined effect of anthropogenic climate change and temperature anomalies from El Niño poses considerable danger to the Pacific’s marine ecosystems. Coral reefs, often described as the “sea rainforests,” are particularly sensitive to changes in temperature. Small increments in temperature are

enough to bring about extensive bleaching phenomena with a potential to threaten biodiversity and the livelihoods of millions that are economically dependent upon healthy reef systems. Ocean acidification, another consequence of elevated CO levels, compounds the problem by weakening coral skeletons and affecting shell-forming organisms. Fisheries also suffer, as El Niño disrupts nutrient upwelling in the eastern Pacific, reducing fish populations and impacting food security for coastal communities. Marine species such as seabirds, whales, and tuna face cascading ecological effects, altering migration patterns and food availability.

2

by Abdellah Bouberima

This illustrates how human-driven greenhouse gas emissions have raised the baseline temperature of the planet, meaning El Niño events now occur in an already warmer world.”

For countries located within the Pacific Islands, these climatic changes present numerous cultural and economic dilemmas. Sustaining traditional fishing industries, the tourism industry, and coast protection programs are compromised and require immediate adaptive management programs that combine Indigenous information with science-based principles.

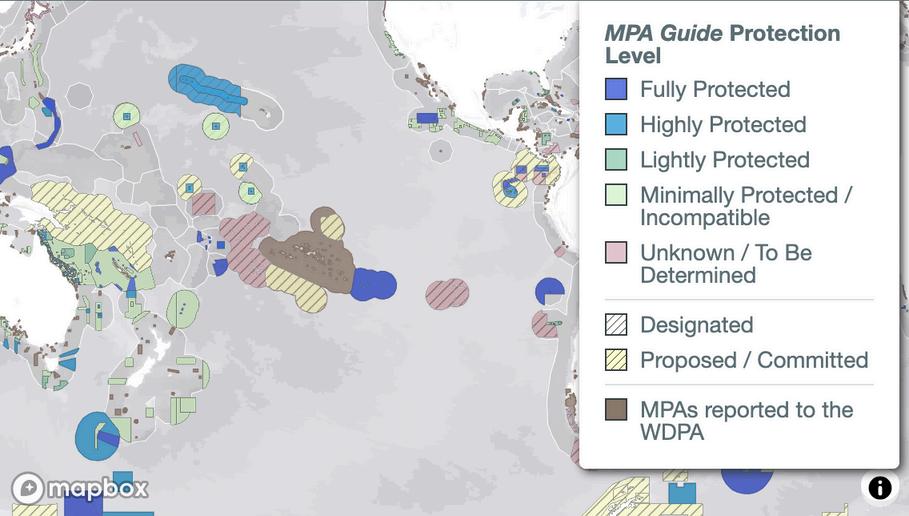

This latest trend of warming seen in 2023 highlights the need for adaptive conservation measures that are data-driven and informed through science studies. Measures like setting up marine protected areas (MPAs), localized pressure reduction like pollution and overfishing, and systematic recording of baseline oceanographic data to track these systems are important measures for effective management Institutions like SEA, which manages ships like the SSV Robert C. Seamans, are important in tracking oceanic conditions and making policy recommendations. Conservation, however, embodies both science and societal challenges. Complications in management efforts are aggravated with issues like deep-sea resource exploitation, plastic pollution, and sea-level rise. With the aim to formulate effective measures, it is crucial to bring

by Abdellah Bouberima

together scientists, policymakers, and local societies to secure ecological integrity and cultural heritage preservation.

Defining the Problem: It is equally important to communicate the nuances of climate science and ocean protection to a global community through effective research efforts Professionals like Rebecca Kessler of Mongabay and researchers like Dr. Kara Lavender Law and Dr. Shreya Yadav (all SEA Quest speakers this summer) prioritize storytelling strategies and appropriate science communication. Using in-real-time data gathered through Pacific explorations, depicting Indigenous resilience, and visual medium usage can help to bridge the gap between research and public understanding.

Incorporating Indigenous ecologic wisdom from Pacific Islanders adds dimensions to stories about conservation that offer cultural-

based solutions supported through present-day science. This shared approach builds trust and allows people to take ownership of climate resilience efforts.

The global warming seen in 2023 presents a mixture of natural climate variability and anthropogenic warming ENSOrelated events, though episodic, are now emerging in a context where temperatures are higher due to their baselines, so they are more severe in their ecological and social impacts This presents greater vulnerability to coral reefs, fisheries, and coastbased societies in the Pacific region.

As Raghuraman et al. note, “Recognizing the dual influence of natural cycles and human activity is critical to preparing for future events.” Addressing these challenges requires more than scientific insight it demands proactive conservation, cross-cultural collaboration, and effective communication. By deepening our understanding of ENSO and its implications, we can build adaptive strategies that safeguard marine ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.

by Abdellah Bouberima

Shiv Priham Raghuraman, et al. “The 2023 Global Warming Spike was Driven by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24 (2023): doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-11275-2024.

NASA, “El Niño: Pacific Wind and Current Changes Bring Warm, Wild Weather ” (Oct 2, 2024): science.nasa.gov.

Imagine a whale teaching its calf the sound of a dialect, clicks passed from generation to generation that define the family’s identity, shape their movements, and guide survival. This is not science fiction but the reality of sperm whales in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (ETP), where cultural transmission plays a central role in structuring whale populations

A new study led by Ana Eguiguren highlights the importance of socially learned behaviors, particularly within distinct clans, in the

conservation of sperm whales. As climate threats, fisheries, and ocean pollution intensify, conservation strategies must evolve to treat culturally distinct clans not just as a curiosity, but as vital conservation units.

Sperm whales are globally classified as vulnerable by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature); their populations are still reeling from historical whaling. Though the practice ceased in the late 20th century, their slow reproductive rate, one calf every 4–6 years, hampers recovery. Moreover,

by Caitlyn Sullivan

by Caitlyn Sullivan

to threats such as microplastics and persistent organic pollutants.

The team found clan-level differences in response to environmental stressors like El Niño events, suggesting varying degrees of resilience. Moreover, mature males who travel between basins appear underrepresented in data, despite their importance in population connectivity

This study urges a paradigm shift: sperm whale conservation must consider culture.”

This study urges a paradigm shift: sperm whale conservation must consider culture Clans are more than social curiosities; they reflect evolutionary strides that influence demography, behavior, and vulnerability. For example, some clans are more impacted by ocean warming or fisheries than others, pointing to the need for targeted protection.

Understanding how sperm whales learn socially could help conservationists predict their adaptability. In the past, whales shared evasive behaviors to avoid harpoons. Today, similar social learning may help or hinder their response to modern threats.

In terms of policy, many nations already recognize distinct population segments for conservation. The U.S. Endangered Species Act and Ecuador’s

Constitution offer legal frameworks that could incorporate culturally distinct clans. Yet, practical challenges remain, especially the lack of long-term, large-scale data collection within ETP nations Outside researchers highlight the need for equitable collaboration. Tools like Flukebook and autonomous hydrophones offer promising, cost-effective monitoring. Open access to software, multilingual resources, and transnational collaboration such as the emerging "Cachalotes del Pacifico" network are essential Ultimately, incorporating social structure into sperm whale conservation isn’t just scientifically sound it’s morally imperative. Protecting culture in the ocean may be the key to saving its most mysterious giants.

Further Reading

One Earth, “Dominica Creates the First Sperm Whale Reserve, A Win for Conservation and the Climate,” OneEarth.org (May 12, 2025): www oneearth org/dominica-sperm-whalereserve

A Eguiguren, et al , “Integrating Cultural Dimensions in Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus) Conservation: Threats, Challenges and Solutions.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 380, no 20240142 (2025): doi org/10 1098/rstb 2024 0142

by Caitlyn Sullivan

B E H I N D T H E S C E N E S : M E E T O U R 2 0 2 5 G U E S T S P E A K E R S

As a group, we have spent the past few weeks learning about the Central Pacific Ocean and its people. During this process, we discovered problems we are passionate about and came up with ideas that could be valuable help for the Central Pacific Ocean and its people as best we can We hope that readers will use this list as a tool to guide their own sustainability choices. This list is open to individual interpretation and by no means finished. Remember that no action is too small!

We want governments to protect communities at risk from sea level rise, such as by helping climate refugees by providing visas or citizenship. We also want our governments to aid nations at risk from climate change by donating to the Green Climate Fund, which funds climate action in developing countries. We also want governments to enforce further preexisting regulations and MPAs in the South Pacific

We want our businesses and corporations to swap their products and packaging for sustainable alternatives. For example, in 2022, Sprite swapped its iconic green bottle for a more sustainable, clear-bottle alternative. We also want businesses and corporations to cut back or abstain from oil drilling. Oil drilling leads to oil spills, air and water pollution, and habitat destruction We believe that reducing this process is a vital step towards aiding the Pacific Ocean.

As individuals we can practice respectful tourism, such as refraining from disturbing the wildlife or buying shell souvenirs. A specific example we want to practice is not to take shells from the ocean because it harms the habitat If we have extra time, we want to volunteer for local climate organizations or partake in community service, such as picking up trash from local beaches. We also want individuals to try and use eco-friendly products and support eco-friendly businesses. Some examples include buying second-hand or using reusable straws.

If we had money, we would donate to charities for local communities to the Pacific Island nations that are on the front lines of climate change. We would also donate to conservation nonprofits that are committed to protecting our natural environment. For example, some that we like are Conservation International and The Nature Conservancy.

We think further research is needed in ocean acidification, specifically better ways we can minimize this process, gain understanding on how it is affecting the south pacific, and better ways to mitigate its effects. Finding biodegradable materials that are affordable and practical. We want to promote further research in this because we want companies to have fewer obstacles and more motivation towards being sustainable

Wdug into some serious issues in the Pacific pollutants hurting sharks, efforts to bring back bird populations on island atolls, preserving island knowledge to help fight climate change, the threat of drifting fish aggregating devices to sea turtles, and problems with managing albacore tuna. These aren’t simple problems; they’re complex and urgent

This issue of SEA Writer isn’t just a bunch of articles. It’s a wake-up call: the future of the ocean depends on action from everyone.”

This issue of SEA Writer isn’t just a bunch of articles. It’s a wake-up call: the future of the ocean depends on action from everyone. Whether it’s small changes by individuals or big decisions by governments, every effort counts. Knowing the facts isn’t enough we have to use what we learn to make a real difference.

Even though we weren’t out on the ocean, we fully engaged with these challenges by gathering research, expert insights, and different viewpoints. This magazine shows that you don’t have to be

physically there to care or act you just need the will to commit

The ocean won’t heal itself. But if we keep learning, stay driven, and push for change, there’s hope.

This is only the start The ocean needs more voices, more action, and more people ready to step up.

Vakarė Berankytė