Raymond A. Cloyd

Western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis, is native to the southwestern region of the United States and has spread since the 1970s, becoming a major insect pest of the horticultural industry (Bailey, 1938; EPPO, 1989; Morse and Hoddle, 2006). Western flower thrips is documented in greenhouse pest management literature as early as 1949 (Pritchard, 1949). However, western flower thrips was not considered a major insect pest of greenhouse-grown horticultural crops until the 1980s when greenhouse producers started experiencing economic losses associated with direct and indirect plant damage (EPPO, 1989; Glockemann, 1992; Jensen, 2000a; Brodsgaard, 2004). The temperature, and abundance of plant material in greenhouses provide conditions that are suitable for the development and reproduction of western flower thrips (Robb, 1989). In addition, the distribution of infested plant material is the primary means by which western flower thrips populations have spread worldwide (Brodsgaard, 1993; Kirk and Terry, 2003).

Western flower thrips is one of the most important thrips species associated with greenhouse-grown horticultural crops worldwide.

Western flower thrips is one of the most important thrips species associated with greenhouse-grown horticultural crops worldwide (Kirk and Terry, 2003). Western flower thrips feeds on a wide-range of greenhouse-grown horticultural crops including ornamentals, vegetables, fruits, and herbs (Brodsgaard, 1989a; Gerin et al., 1994;

Helyer et al., 1995; Tommasini and Maini, 1995; Parrella and Murphy, 1996; Lewis, 1997a; Reitz, 2009; Cloyd, 2009a). Western flower thrips is a difficult insect pest to manage in greenhouse production systems due to several biological parameters:

1. short life cycle (egg to adult)

2. high female reproductive potential (fecundity)

3. broad host range (including a variety of ornamental and vegetable plants)

4. transmission of plant viruses

5. development of resistance to insecticides (Jensen, 2000a; Reitz, 2009)

Western flower thrips are approximately 0.078 inch long, light-brown, elongated, with piercing-sucking mouthparts.

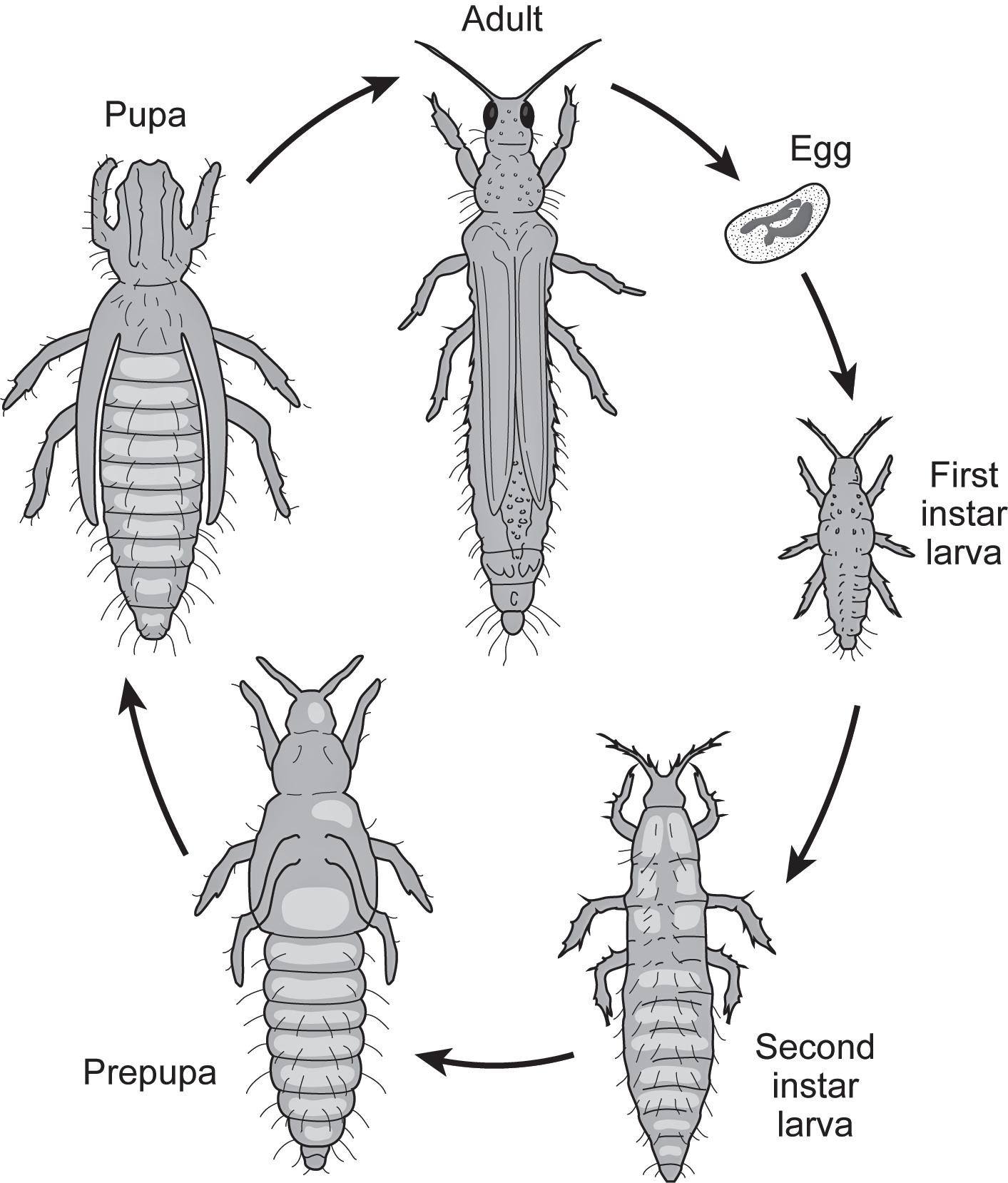

Western flower thrips are approximately 0.078 inch long, light-brown, elongated (Fig. 1), with piercing-sucking mouthparts (Bailey, 1938; Chisholm and Lewis, 1984; EPPO, 1989; Hunter and Ullman, 1989). The life cycle consists of an egg, two larval instars (first and second), two pupal stages (prepupa and pupa), and an adult (Fig. 2). In general, the life cycle,

from egg to adult, can be completed in 2 to 3 weeks (Robb et al., 1988; Ananthakrishnan, 1993; Tommansini and Maini, 1995; Mound, 1996).

However, development time depends on temperature. For instance, the life cycle can be completed in 7 to 13 days at temperatures between 79 and 84°F (Lublinkhof and Foster, 1977; Robb et al., 1988; Gaum et al., 1994; Tommasini and Maini, 1995).

Western flower thrips females are larger than males and vary in color from yellow to dark-brown, whereas males are pale yellow

(EPPO, 1989; Robb, 1989; Robb and Parrella, 1989). Females can live up to 45 days and lay between 25 and 230 eggs during their lifetime, although females usually lay (oviposit) an average of 40 to 50 eggs (Bailey, 1938; Robb, 1989). The number of eggs laid by individual females depends on temperature with 130 eggs laid at 68°F and 230 eggs laid at 81°F (Robb, 1989). Adult females feed on pollen and nectar to obtain carbohydrates, proteins, sterols, and vitamins (EPPO, 1989; Gerin et al., 1999) required for reproduction (Trichilo and Leigh, 1988; Brodsgaard, 1989a; Oetting, 1991; Higgins, 1992). Western flower thrips feeding on plants containing elevated concentrations of nitrogen resulting from overfertilization access abundant levels of amino acids and proteins, which enhances female reproduction (Ananthakrishnan, 1993).

Females typically lay eggs underneath the epidermal layer of leaf surfaces, or in flower or fruit tissue, which protects the eggs from exposure to insecticides and biological control agents (EPPO, 1989; Lewis, 1997b; Brodsgaard, 2004). Larvae emerge (eclose) from eggs in 2 to 4 days (Cloyd, 2010a) and feed on leaves (Fig. 3), flowers, and fruits

(Thoeming et al., 2003). The first instar larvae are present for 1 to 2 days and the second instar larvae are present for 2 to 4 days (Robb et al., 1988). However, high temperatures will reduce development time of the larval stages. Second instar larvae, in general, are more active and feed more than first instar larvae (Tommasini and Maini, 1995).

Second instar larvae migrate toward the base of a plant and then enter the growing medium in containers to pupate (Thoeming et al., 2003; Steiner et al., 2011; Holmes et al., 2012). Western flower thrips will also pupate in the soil underneath benches, in leaf debris, on the plant, and in the flowers of certain plants, such as chrysanthemum, Tanacetum × grandiflorum (Fransen and Tolsma, 1992; Jacobson, 1997; Bennison et al., 2002; Broadbent et al., 2003; Buitenhuis and Shipp, 2008). There are two pupal stages: prepupa (Fig. 4) and pupa (Fig. 5) that take approximately 5 days to complete development (Arzone et al., 1989; Robb, 1989; Daughtrey et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2007). Pupal stage survival is influenced by growing medium or soil type and pH.

Second instar larvae migrate toward the base of a plant and then enter the growing medium.

Fig. 4. Western flower thrips prepupa. (Courtesy R. Cloyd— © APS)

Fig. 5. Western flower thrips pupa. (Courtesy R. Cloyd— © APS)

In addition, pupation depth depends on growing medium or soil type (Varatharajan and Daniel, 1984). The pupal stages do not feed and are protected by their location in soil or growing medium from insecticides applied to plants to manage populations of feeding larvae and adults (Bailey, 1938; Robb, 1989; Robb and Parrella, 1989; Tommasini and Maini, 1995; Kirk, 1997; Seaton et al., 1997). Adults eclose from pupae after approximately 4 to 6 days (Robb et al., 1988). Western flower thrips adults (Fig. 6) have narrow fringed wings but have limited flying ability (Bailey, 1938). Adults can be dispersed throughout a greenhouse by air currents associated with horizontal airflow fans or from wind entering greenhouse openings from outside (EPPO, 1989; Robb and Parrella, 1989; Mound, 1996; Daughtrey et al., 1997).

Western flower thrips adults use the color of leaves and flowers and/or plant-based volatile compounds to locate plants.

Western flower thrips adults use the color of leaves and flowers and/ or plant-based volatile compounds to locate plants (Brodsgaard, 1989b; Teulon et al., 1999; Blumthal et al., 2005). Adults are attracted to certain wavelengths of flower colors, including yellow, blue, and white, and plant-based volatile compounds such as (E)- β -farnesene and para-anisaldehyde (Teulon et al., 1993; Manjunatha et al. ,1998; Koschier et al., 2000; Davidson et al., 2012). Adults are also attracted to flowering plants including chrysanthemum, Tanacetum × grandiflorum (Fig. 7); Transvaal daisy, Gerbera jamesonii (Fig. 8); marigold, Tagetes spp. (Fig. 9); and rose,

Fig. 6. Western flower thrips adult. (Courtesy R. Cloyd—© APS)

7. Chrysanthemum plants are susceptible to western flower thrips. (Courtesy R. Cloyd—© APS)

(Courtesy

Rosa spp. (Fig. 10) (Walker, 1974; Yudin, et al. 1987; Vernon and Gillespie, 1990; Kirk, 1997; Daughtrey et al., 1997; Terry, 1997; Bennison et al., 1999; Bennison et al., 2002; Blumthal et al., 2005; Avellaneda et al., 2022).

Western flower thrips larvae and adults feed in terminal leaf growth or unopened flower buds (EPPO, 1989; Robb and Parrella, 1989). Hence, feeding damage is not noticed until leaves expand (Fig. 11), flowers open (Fig. 12), or fruit matures (Pearsall, 2000; Cloyd, 2009a). In addition, feeding locations on plants protect western flower thrips from exposure to insecticides and biological control agents (Bailey, 1938; EPPO, 1989; Robb, 1989; Tommasini and Maini, 1995; Mound, 1996; Jensen, 2000a; Brodsgaard, 2004; Egger and Koschier, 2014; Kirk et al., 2021).

Western flower thrips larvae and adults feed in terminal leaf growth or unopened flower buds.

Western flower thrips have a haplodiploid breeding system where females develop from fertilized eggs and males develop from unfertilized eggs (Robb and Parrella, 1989; Moritz et al., 2004; Kumm and

11. Feeding damage on pepper leaves caused by western flower thrips. (Courtesy R. Cloyd—© APS)

Moritz, 2010). Females must mate to produce females, whereas unmated females only produce males by parthenogenesis (Bryan and Smith, 1956; Higgins and Myers, 1992; Heming, 1995; Mound, 1996; Moritz, 1997). The sex ratio (females: males) depends on population density with males, in general, more abundant at low population densities, whereas females are more abundant at high densities. High population densities of western flower thrips in greenhouses increases the probability of females encountering and mating with males after a period of time (maturation) following adult eclosion (when adult emerges after the final molt). In addition, high population densities result in an age structure that consists of young females producing mostly females. However, as adult females age, males are produced regardless of population density (Higgins and Myers, 1992).