In her essay in this issue, writer Ali Cook has a line I keep returning to: “I tried not to be political. But that became impossible. I am political—it’s who I am.”

I’ve thought about that line a lot over the past month, through multiple rereads and a very diligent editorial process. Can anyone really afford not to be political in today’s environment?

I’m also stealing her quote for this editorial; it neatly captures what this issue is trying to do.

It’s no secret that Salient has traditionally leaned left. Every year, a new editor decides for themselves how political they want to be.

As media organisations, the stated goal is impartiality. But personally, I can’t justify that stance. I recognise Palestine as a state. I believe in free dental care. I think public transport should be widely accessible, and I believe the government must do more to house those without a home, regardless of circumstance.

Last year, I thought being ‘political’ as Editor meant extending an olive branch. We worked hard to bring as many politicians as we could onto our podcasts, across the spectrum. We sought out stories that fit a middle ground and did our best to balance political perspectives without shying away from them.

But in an increasingly polarised world, what does it mean to run a media organisation—even one as small and self-aware as Salient—in these times?

This issue is my response.

It is political. It’s often a hard read, and its curation makes my stance on the government clear. That doesn’t mean it’s entirely one-sided.

Did I ever think I’d walk into ACT Party headquarters? No. Yet I did, for a story that the MP I interviewed described as “not about politics.” To my surprise, I found myself agreeing.

There are topics that should be debated—the 2020 Cannabis Referendum, for example. And there are topics that shouldn’t, like the value of a human life.

If I had to summarise this issue in a single question, it would be: what is a human life worth? And to whom?

We only have two features this week. One is self-indulgent: an essay on the Radium Girls, a group of women who have been on my mind for years. It asks what a life is worth when it enters the courtroom in a decaying body.

The other is a long-form feature from Ali Cook, who asks what a life is worth when it contradicts the government’s diplomatic relations. What is it worth to be “tough on crime”—but not for her?

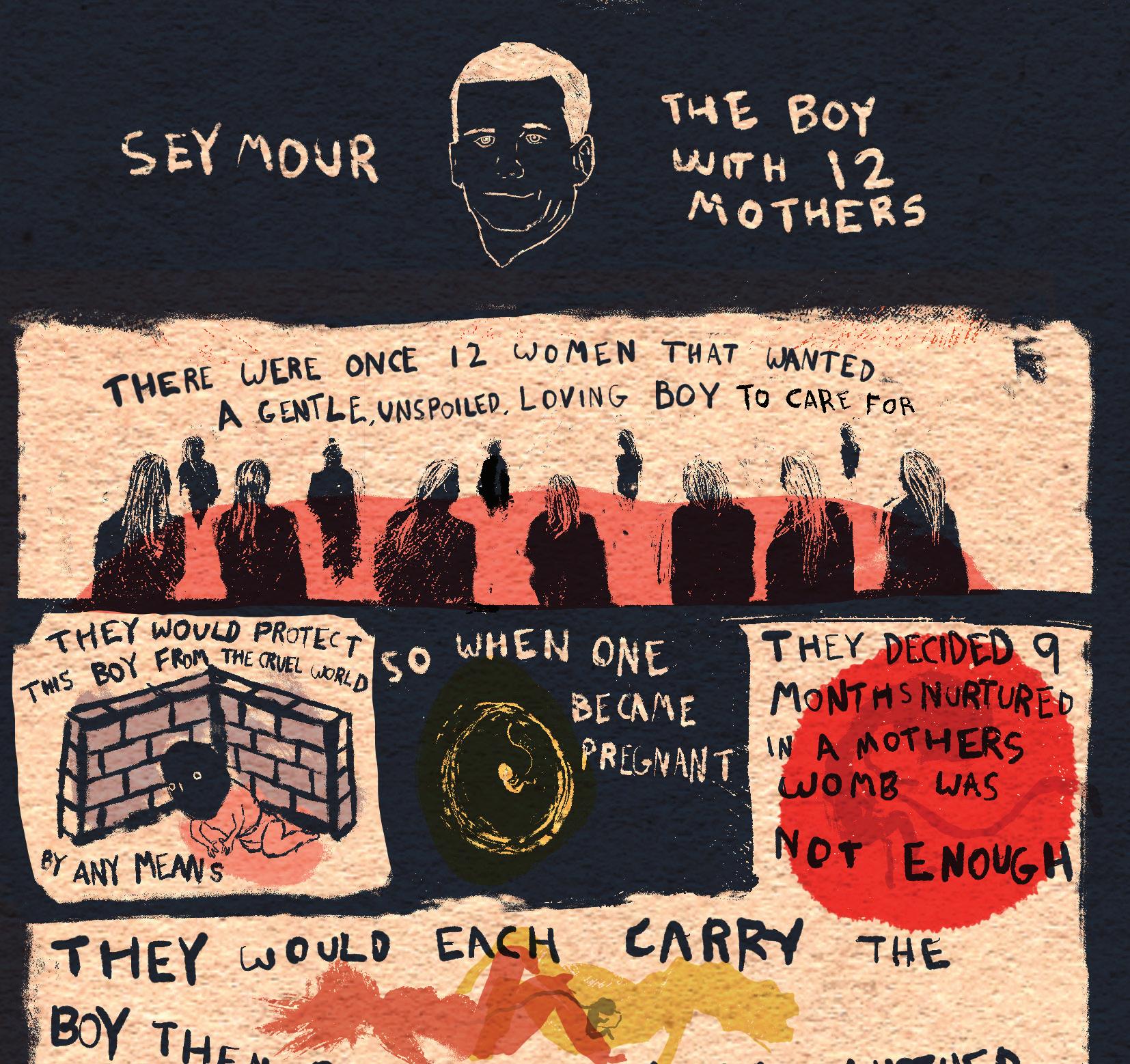

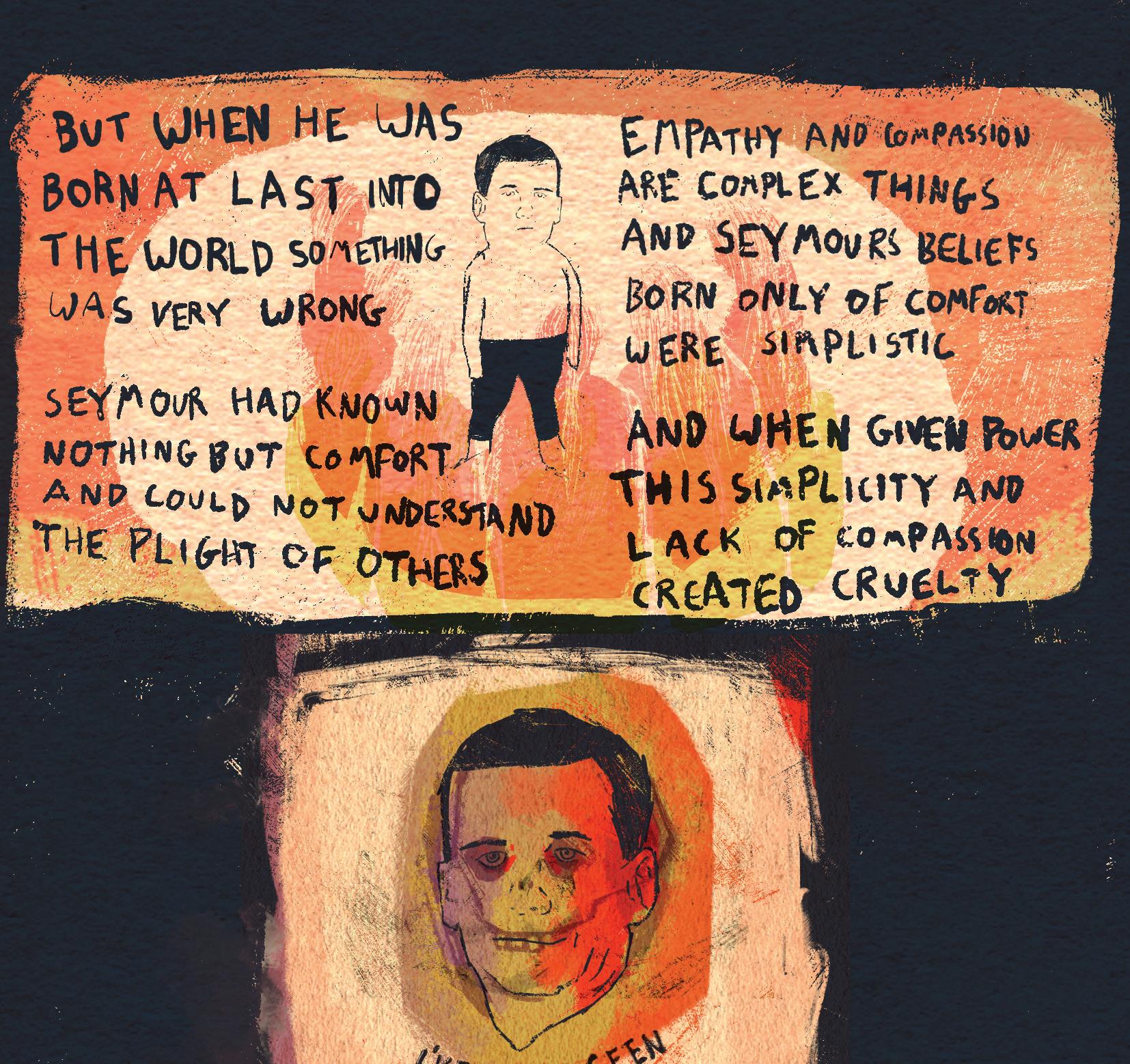

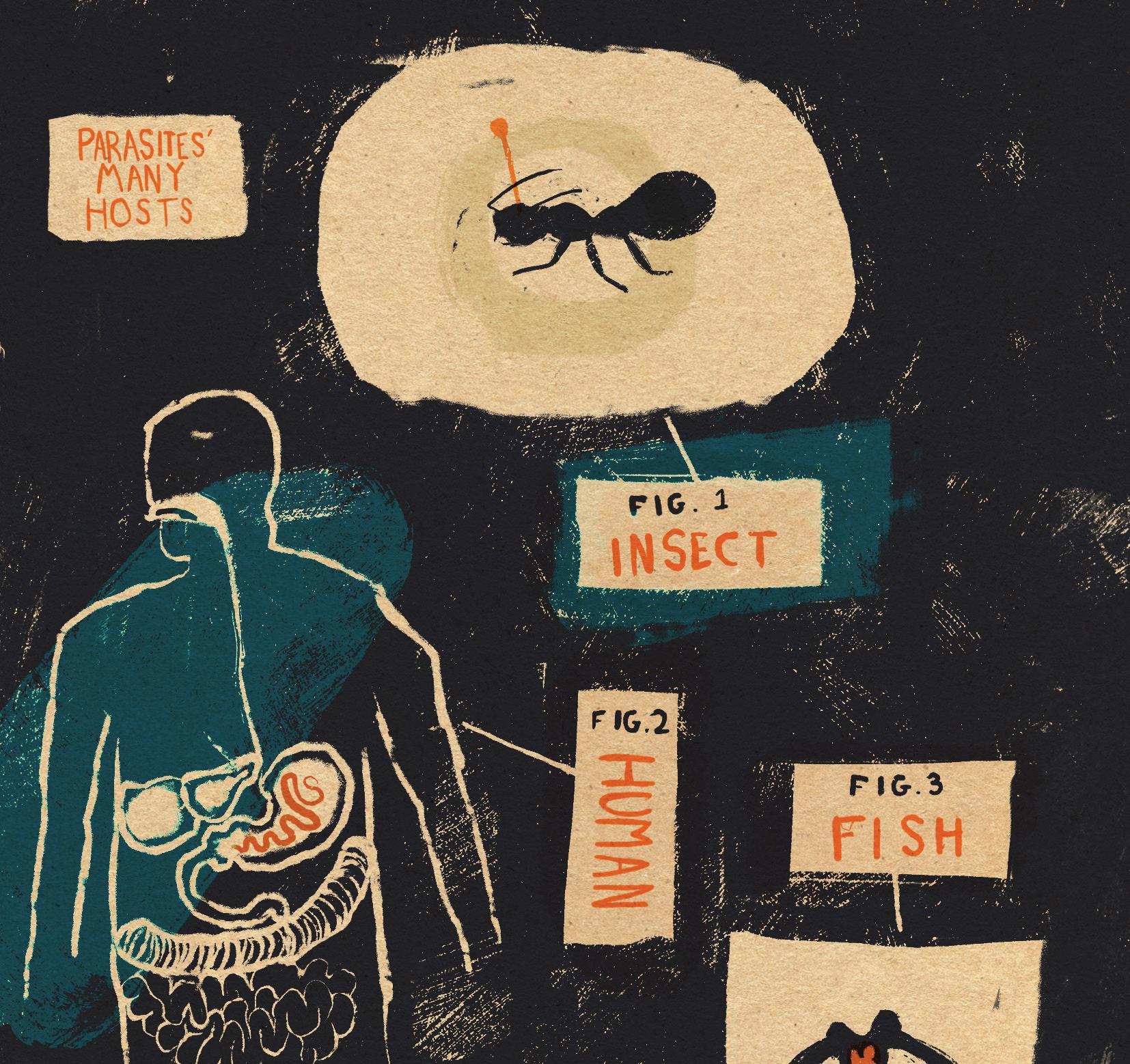

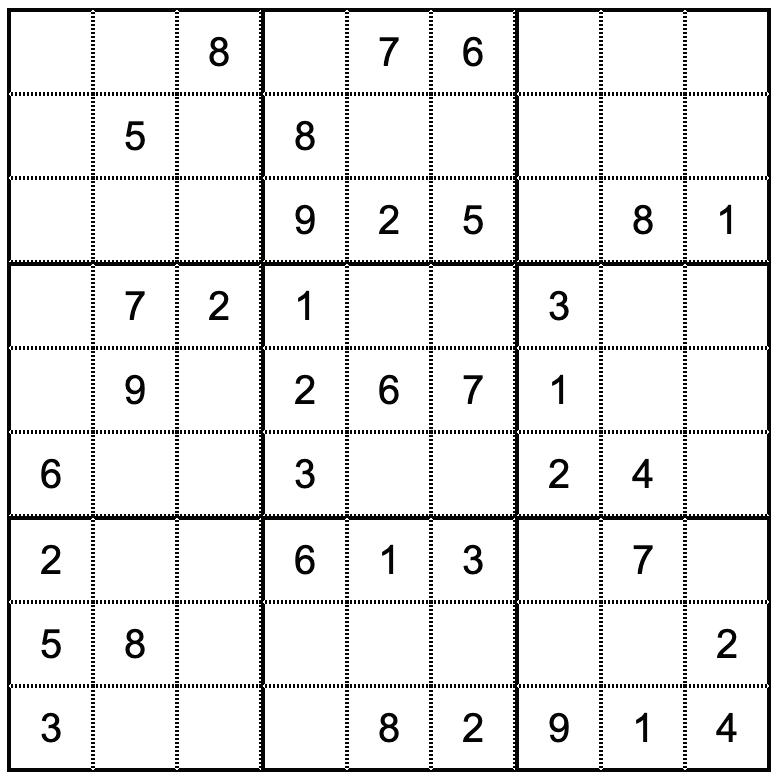

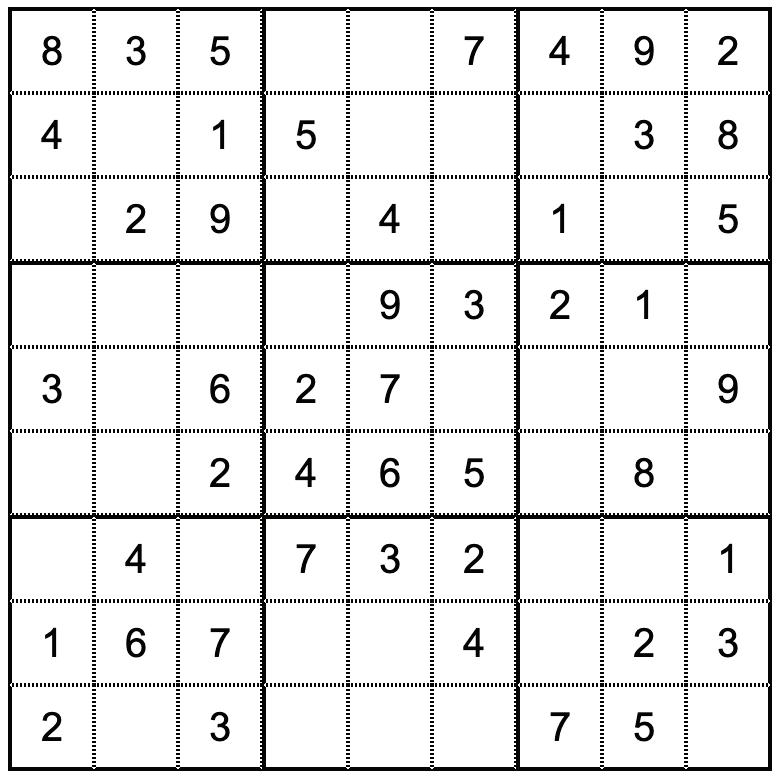

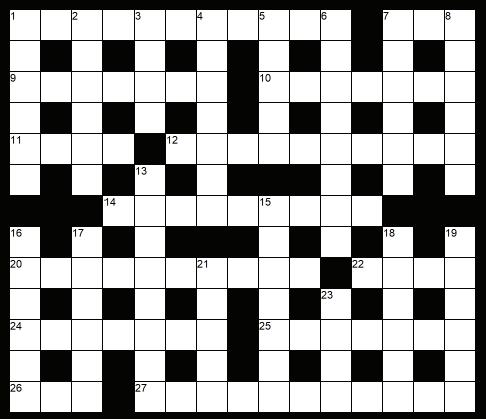

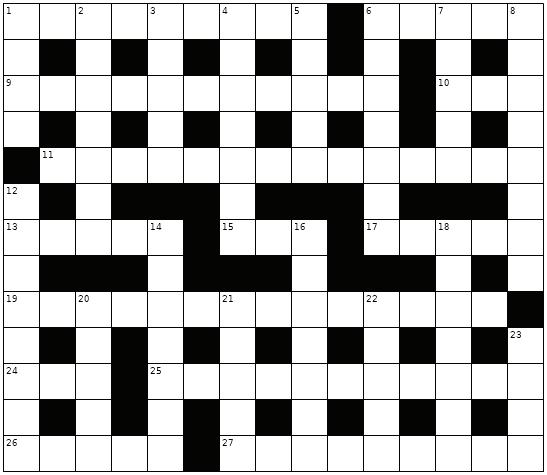

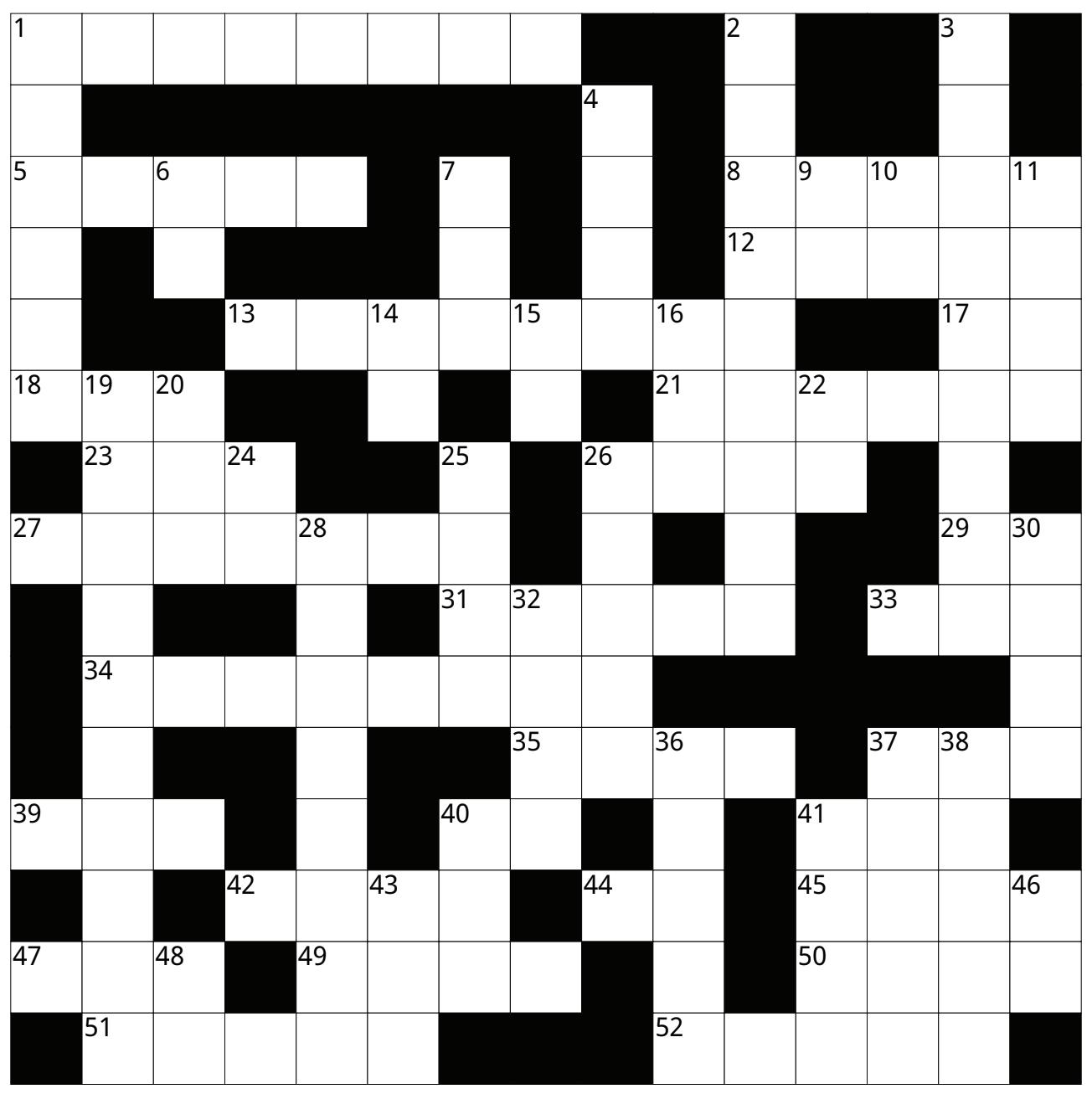

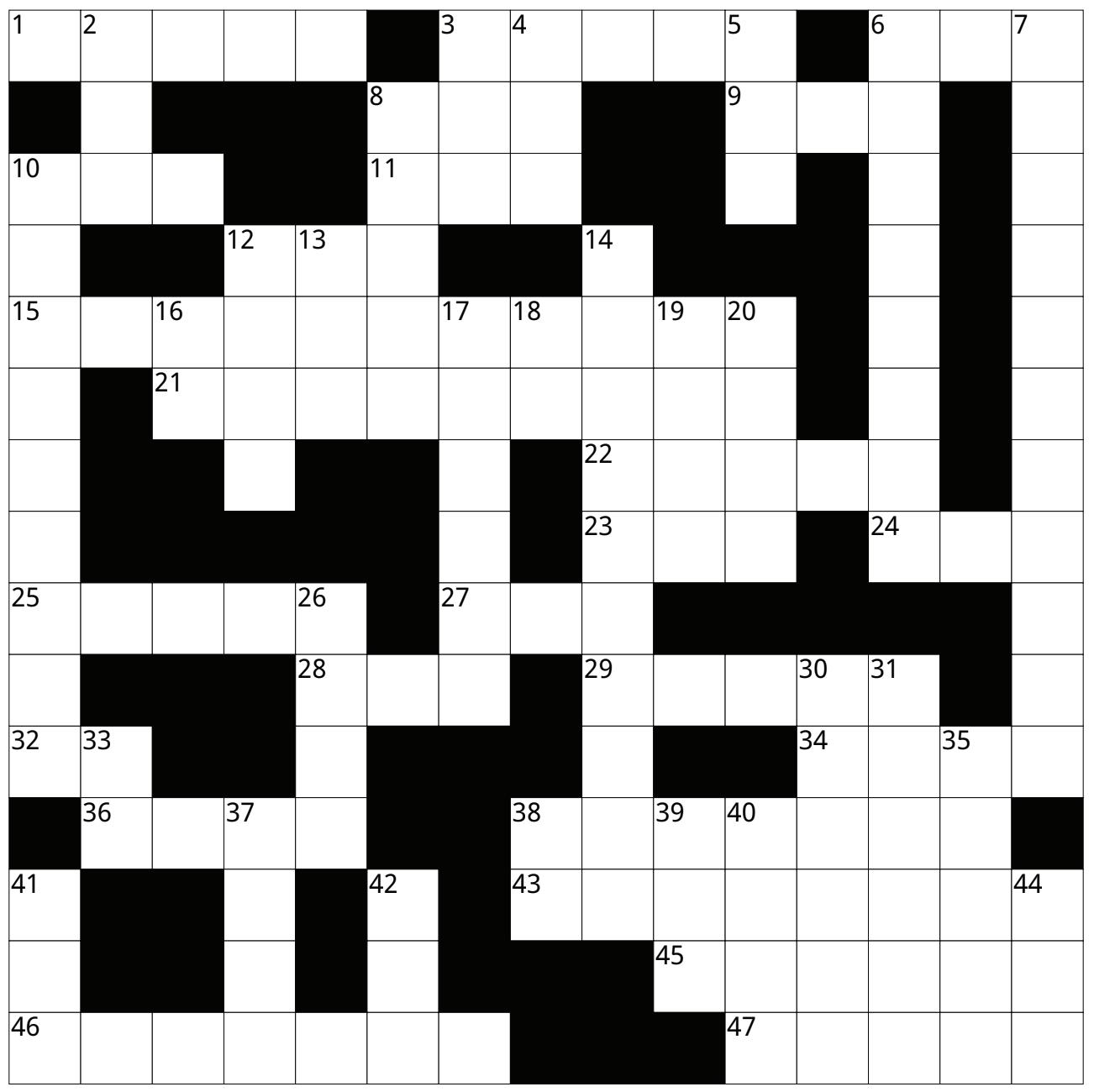

Beyond those, this issue also carries sharp political comics from Brahms Hole, poetry from Holly Rowsell and Isabella Fuller, five crosswords (for those not tempted by the features), and a piece of art Aspen Jackman and I created to recognise the team’s work this year—past and present.

I want to end with thanks: to the authors who trusted me with their work, to the staff who welcomed me, and to VUWSA for their trust. I’ll see you all next year as Editor-in-Chief, no longer just Acting.

And today, I sign off with love.

By Phoebe Robertson

Time: Tuesday 8:30pm

Location: Valhalla

Your favourite, drunkest Aussie punk band is back in Wellington. Fuck having a sensible week: go to a loud, fun, garage-punk show this Tuesday. You might regret it on Wednesday morning; you’ll regret missing out more.

Our Beloved Ditch EP Release w/ Tessa De Lyon and SGP

Time: Thursday 8:30pm

Location: MOON

Our Beloved Ditch have just released a new EP. If they’re not on your radar, they should be: the trio, from up the coast in Te Papaioea, have a distinct, often melancholy, somewhat diffident bedroom-rock/altfolk feel. They’re lovely, unique, and worth catching. Supported by Tessa de Lyons (super lovely dreampop/folk) and SGP.

Time: Friday 9:30pm

Location: Rogue and Vagabond

Big brass section, cumbia beats, irresistible guitar solos, “bilingual bangers”; 11-piece(!) outfit CUMBIA BLAZERA has everything you need for a great dancefloor and a cathartic Friday. Spring in Pōneke kinda sucks. Let the sounds of Columbia and Latin America transport you.

Newtown Record Fair (FREE!)

Time: Saturday 11am - 3pm Community Center, Rintoul St

The Newtown Record Fair is back! Nikki Lou Records and High Voltage Vinyl Wairarapa are hosting; there’ll be merch, vinyl (of course), CDs, tapes, and a carefully curated video-playlist to soundtrack your vinyl hunt. Free entry.

Queer Horizons Presents: Hot Mooch

Time: Saturday 9pm

Location: Valhalla

Queer Horizons—a night of dance music centering Indigenous, queer and queer-allied DJs—has been a recent staple of the Ōtautahi queer dance and music scene. This Saturday, they bring their party experience to Valhalla with Hot Mooch: AAKI, Oil Grace, Mr Meaty Boy and DJ Thank You So Much, throwing a dance party. Come have a kanikani.

KING HOMEBOY, Dear Antler, Adoneye, Electric Tapestry

Time: Thursday 7:30pm

Location: Valhalla

An unmissable genre explosion is taking place at Valhalla this Thursday. Master of 90s hip-hop flow King Homeboy—Pōneke royalty and regular feature outside Cuba St Night n’ Day—will be joined by Antler’s desert rock, Adoneye’s alt-grunge, and ET’s poppsych. Abundance.

Klo-promotions Presents: Koupled

Time: Thursday-Friday, 7pm-10:30pm

Location: Hamodava Cafe

Klo Promotions—a new promoter recently profiled in Salient—wants to show you all the emerging musicians they’ve found. During this rolling, two-day event, park up for a coffee at Hamodava on Cuba and tune into a curated, live selection of some of Pōneke’s best up-and coming artists.

FONZO w/ UNWELL, FRONTA and WHAEA G

Time: Saturday 9pm

Location: MOON

Bristol-based jungle, garage and techno innovator FONZO is visiting Aotearoa, and will be gracing the decks at MOON with three excellent supporting DJs, all for a cool $15. Expect dark, fun breaks that don’t hold back, and a high-energy night on the dancefloor.

Time: Saturday 7pm

Location: 13 Garret Street

Museumofgarrett.com & 13 Garrett Street present: ARCHIVE FUNDRAISER: “an open call for anyone who has interacted with 13 Garrett Street to share your stories with our growing archive.” The iconic building faces earthquake strengthening and potential gentrification—join them to reminisce, archive, create, and dance to live music.

Sunday Jazz (FREE!)

Time: Sunday 5pm

Location: Rogue and Vagabond

I have very exciting news, my friends: as of late last week, the endless benevolence of the Wellington City Council has once again bestowed upon Rogue a licence to sell beer in the park. Grab a plastic beer cup, sit your ass on a foam squab encased in hessian, and soak up the sun. Should you do so this Sunday, you’ll be serenaded by the wonderful jazz of Bert Henderson.

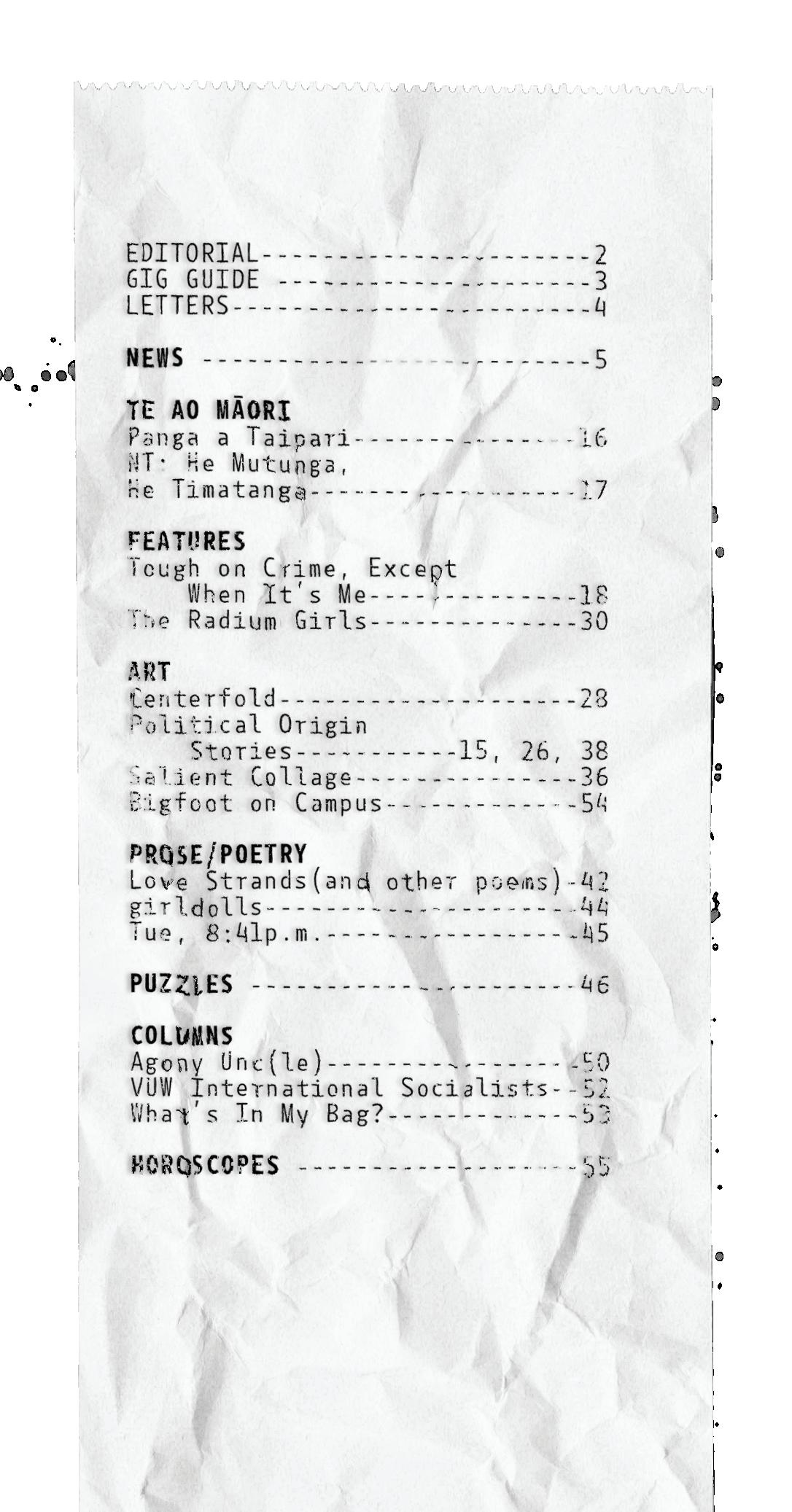

#24: 6 October 2025

EDITOR

Phoebe Robertson (Acting) TE AO MĀORI EDITOR

Taipari Taua

NEWS EDITOR

Dan Moskovitz

NEWS WRITER

Darcy Lawrey

MUSIC EDITOR

Jia Sharma

SUB-EDITOR

Henry Broadbent

COLUMN EDITOR

Georgia Wearing

DESIGNER

Cal Ma

JUNIOR DESIGNER

Nate Murray

FEATURE WRITER

Te Urukeiha Tuhua

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

Teddy O’Neill

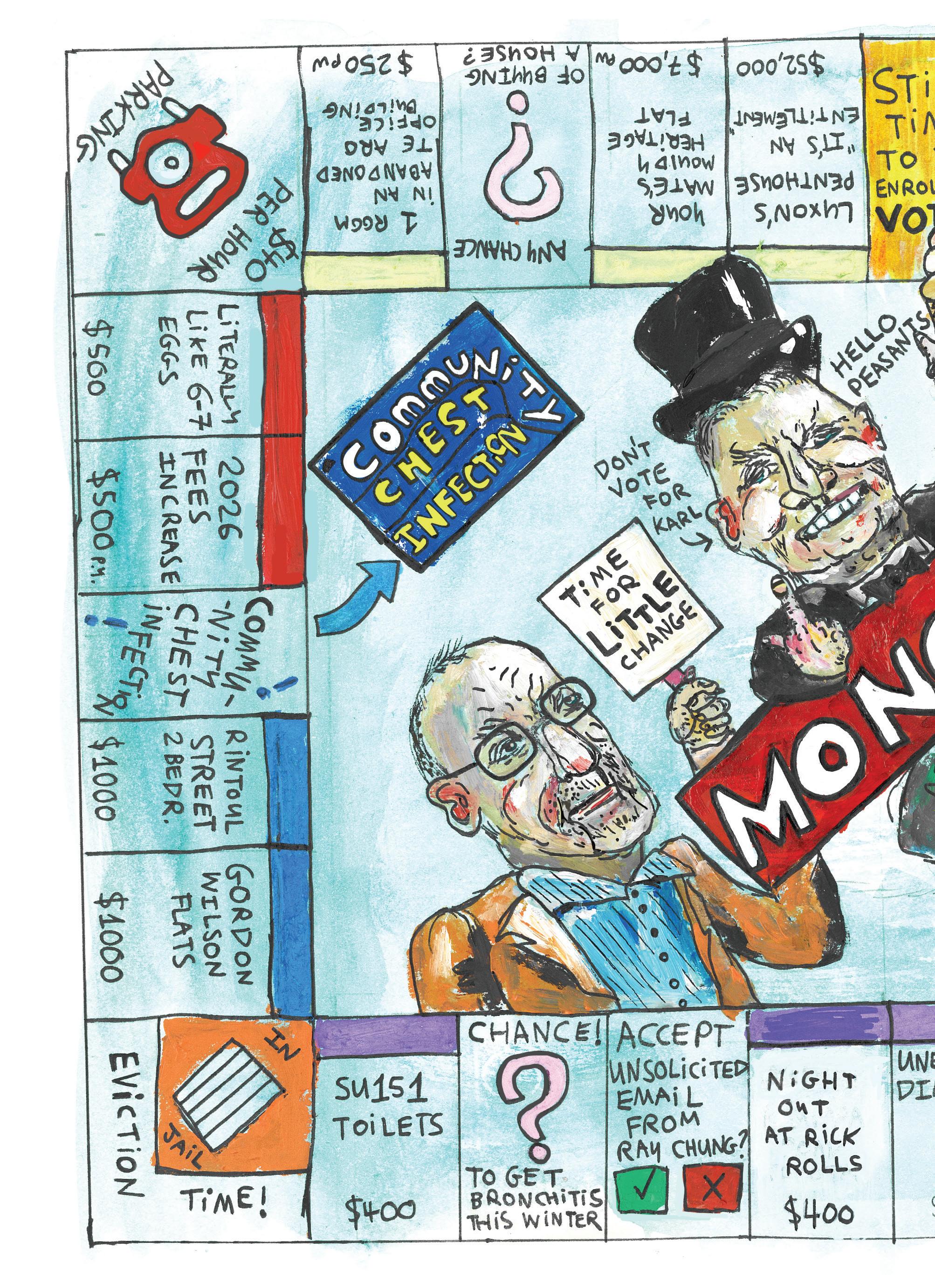

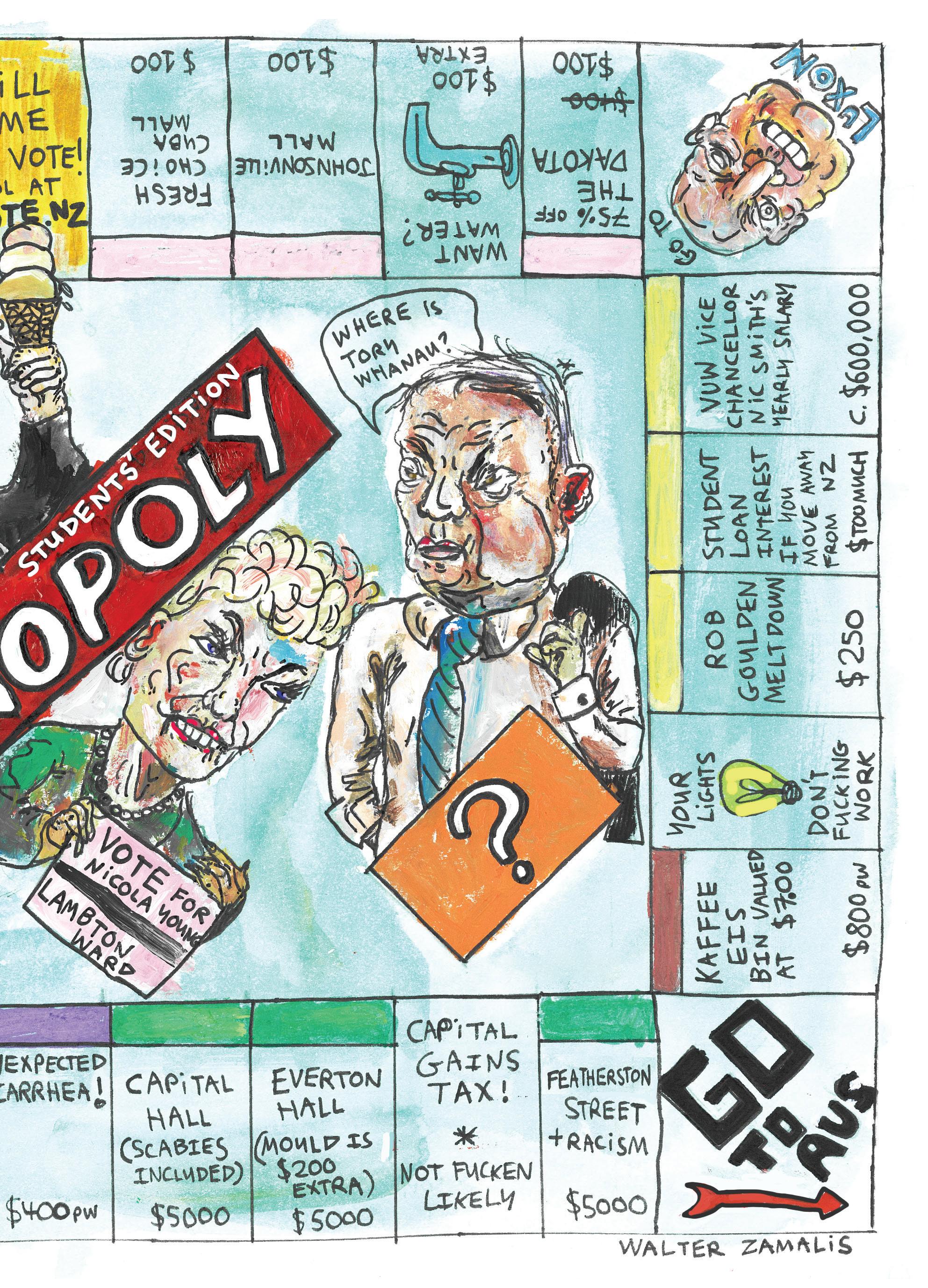

NEWS WRITER/POLITICAL CARTOONIST

Walter Zamalis

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Ryan Cleland

Saad Aamir

Guy van Egmond

CONTRIBUTING CARTOONISTS

Jim Higgs

Sophia Knoef

Brahms Hole

CROSSWORD CONTRIBUTORS

Nil

Julia Corston

Holly Rowsell

Puck

RESIDENT COLLAGIST

Aspen Jackman

CENTERFOLD

Walter Zamalis

DISTRIBUTION

Saad Aamir

ADVERTISING SALES advertising@vuwsa.org.nz

READ ONLINE salient.org.nz issuu.com/salientmagazine

GET IN TOUCH editor@salient.org.nz

Instagram/salientgram Tweet/salientmagazine

Facebook/Salient

LETTERS

Got something to say about the magazine? Want it published? editor@salient.org.nz

Salient is published by, but remains editorially independent from, the Victoria University of Wellington Students Association (VUWSA). Salient is funded in part by VUWSA through the Student Services Levy. Salient is a member of the Aotearoa Student Press Association (ASPA).

Complaints regarding the material published in Salient should first be brought to the VUWSA CEO in writing (ceo@vuwsa.org.nz). Ideally, by motorcycle. A letter can also be sent to the editor, for their response/publication in the magazine. If not satisfied with the response, complaints should be directed to the Media Council (info@mediacouncil.org.nz).

Kia ora koutou,

As the year comes to a close, I want to take a moment to acknowledge you—the Salient team—for everything you’ve carried and everything you’ve achieved in 2025.

This has not been a normal year. The circumstances you found yourselves in were deeply unsettling and placed a weight on your shoulders that no student media team should ever have to bear. It disrupted your work, tested your relationships, and at times must have felt overwhelming. And yet, despite all of that, you kept going.

Issue after issue, you continued to create a magazine that gave voice to students at Te Herenga Waka. You made sure there was still space for humour, critique, art, politics, and storytelling. You kept alive a platform that has been a cornerstone of our student community for generations. That is something extraordinary, and you should all be proud of it.

I know the challenges were immense. You weren’t just working to meet deadlines or fill pages—you were holding each other, keeping the team together, and navigating uncertainty while still showing up to do your jobs. That takes courage. That takes aroha. I want to especially acknowledge the work that often goes unseen: the writers and contributors who kept submitting their stories, the illustrators and designers who poured creativity into each issue, and the staff who showed up for one another when things were tough. It is your collective effort, often quiet and uncelebrated, that ensured Salient remained in students’ hands this year.

Salient has never just been about a magazine on the shelves. It’s about voice, perspective, and community. It’s about giving students the chance to see themselves reflected, to be challenged, and to feel connected. This year, more than ever, you proved that purpose endures—not because it’s easy, but because you believed in it enough to keep going when it was hard.

To the 2025 Salient whānau: thank you. thank you for your resilience, your creativity, and your dedication. thank you for holding fast to the kaupapa of independent student media through one of the most difficult years in its history. And thank you for reminding us all why student voices matter.

When I think about Salient in 2025, I won’t think only of the challenges you faced. I’ll think about the strength, compassion, and determination it took to keep publishing, to keep telling stories, and to keep creating something that belongs to students. That legacy is yours.

Ngā mihi nui to each of you for your mahi this year. What you have achieved, under circumstances no one should have to endure, is remarkable—and it deserves to be remembered.

With aroha and deep appreciation, Liban Ali

This week is Te Wiki o te Hauora Hinengaro—Mental Health Awareness Week!

Boost your hauora hinengaro with your Te Herenga Waka whānau across all three campuses. our University-wide Mental Health Awareness Week programme is full of opportunities to Top Up Together!

Mental health and wellbeing are part of everyone’s journey. Whether you’re working, studying, or simply navigating life, take some time to connect and recharge with others.

Check out the week’s programme at wgtn.ac.nz/ wellbeing-events and follow @vuwequitywellbeing for updates.

Nāu te rourou, nāku te rourou, ka ora ai te iwi—with your food basket and mine, the people will flourish!

By Darcy Lawrey (he/him)

The day I interviewed Aidan Donoghue, the 2026 VUWSA president, he was already getting stuck into the job addressing VicCom, the commerce students’ society. I sat down with him in VUWSA’s long-forgotten Pipitea office to hear how he got to where he is, and what his plans are for VUWSA.

Donoghue grew up in Rotorua, where he was the Head Boy at Fraser High School. On the very last day of year 13 he was selected as the youth MP for Gaurav Sharma, the Labour MP who was expelled from Labour following allegations of bullying; Aiden’s first foray into the political world. He recalls being hounded by a journalist for comment on the MP’s behaviour.

After college, Donoghue headed south for Wellington to study at VUW with his now fiancé, who he met working at McDonalds at age 15.

He gives major credit to his friend William BellPurchas, the VUW Student Board Representative for getting him stuck into politics here in the capital. In 2022 he unionised his workplace, the Taranaki Street McDonalds, which saw him negotiating a collective agreement with the Auckland head office.

That led to a job at the Council of Trade Unions working on fair pay agreements, and then one at NZEI, the primary school teacher’s union. Last year he became the Engagement Vice President at VUWSA, his second time running for the role. This year, he’s got the top job.

He’s both very proud of his win, and of the massive increase in engagement VUWSA has seen this year. “I’m still reeling from it, it still hasn’t really sunk in yet,” he said.

Donoghue believes that VUWSA has the power to be an economic driver of change within Wellington. As an organisation that represents roughly 10% of Wellington’s population, he believes VUWSA has the numbers to throw its weight around when it comes to setting affordable prices for things like rubbish bags.

His primary focus for VUWSA this year is providing increased and improved services for Students. But he’s still keen for VUWSA to keep up its political campaigning, which he thinks will be bolstered by VUWSA engaging more with students through services on campus.

“Politically, the key thing I want to stress is that the student vote is not guaranteed”, he says. “I want to see specific policies from any side of the table which address student concerns.”

He brings the spirit of labour organising to the role. If he could change one law, he’d make union membership opt-out, instead of opt-in. He’s big on community, and says the number one change he wants to make on campus is providing more third spaces and opportunities for students to connect: “More services, more interaction, and just more bang for your buck for student services”.

Donoghue struggles to pick a favourite campus, as studying taxation had him at Pipitea most of the time during his undergraduate study, but he says the food options at Kelburn gives it the edge. You’ll find him most days enjoying a cheese scone at The Lab.

By Darcy Lawrey (he/him)

VUWSA’s election last month saw a massive jump in candidates. It was the first time more than one person ran for President since Tamatha Paul, now the MP for Wellington Central, won in 2018. It wasn’t just a two-horse race either; five candidates contested the role. The increase in competition saw a corresponding surge in complaints about the conduct of candidates.

Matt Tucker, VUWSA CEO, says 17 complaints were made. The last time any substantial complaints were made about candidates in VUWSA’s election was also in 2018. He says roughly half of the complaints this year were made by current members of the VUWSA exec.

VUWSA’s election rules try to prevent any unfair advantage incumbent candidates might get through their public roles. Restrictions are placed on what incumbent candidates can do during the two-week election period, including a ban on appearing in VUWSA’s social media, or in Salient.

Tucker says the rules are “quite open, and [are] about transparency and fairness.” The Returning Officer, who is responsible for the election results, has some discretion in how they are applied.

Complaints against two candidates were upheld, both of whom were incumbent candidates. One was made against Presidential candidate Josh Robinson for using a VUWSA sound system to throw a campaign flat party. The other was against Welfare Vice-President candidate, Aspen Jackman, for an unapproved appearance in a Salient article, once the election period had started.

Jackman, this year’s Equity Officer, was reelected as VUWSA’s Welfare Vice President for 2026. Her vote total was reduced by 2% for her appearance in a Salient article, titled: Women in the Arts. While she thinks it’s fair to make a complaint, she’s “upset” that her votes were reduced “partially because it detracts from the writing in Salient.” She was not aware that she required clearance to appear in the article.

She believes some rules need changing, particularly when it comes to posters. VUWSA prints off 100 posters each for all candidates, but she says some candidates put up “hundreds” of posters. University staff had also made complaints to Tucker about the sheer number of posters plastered across the campuses.

Other behaviour which drew complaints included: a candidate displaying their campaign poster on the information display in The Hub; a candidate handing out cake as a “bribe” for votes, and; concerns that candidates were spending over the spending cap of $100.

It is too soon to say if this year’s historic VUWSA election will also end in the House of Representatives; we can say that Student democracy is back, and it’s scrappy.

Voters’ enrolment records are disappearing into thin air.

The Electoral commission claims that they are being procedurally moved to the ‘dormant role’; te Pāti Māori are pursuing investigation and legal action against the commission. Debbie Ngarewa-Packer echoes the suspicion of many: “This is not a mistake. It’s voter suppression.”

Since July, social media has erupted with angry reports of missing enrolment records, enough that even the mainstream media published a few articles.

Alarmingly, a large chunk of the missing enrolments belong on the Māori roll. Even within a single household, those enrolled on the Māori roll have had to renew their enrolment, while whānau on the general roll are unaffected.

Voters enrolled in advance of the election period should receive a voting pack and postal ballot to assist them in voting.

If you haven’t yet received your voting pack for the local body elections, chances are that your enrolment has silently fallen on the chopping block.

Anusha Guler, the Deputy Chief Executive of Operations at the Electoral Commission, suggests that the missing records have been moved to something called the ‘dormant roll’:

“If we lose touch with you—for example if we get returned mail from an old address—we will try to contact you by email or text to ask you to update your details. If we can’t contact you or don’t hear back from you, you may be put on the dormant roll.”

For all intents and purposes, the dormant roll is rubbish that hasn’t been taken out yet. Although you won’t receive a postal ballot, the dormant roll enables you to vote at in-person polling stations—but as long as you meet voting requirements, you can do that regardless.

However, under recent and widely condemned changes to electorate law, voters will now need to be enrolled at least two weeks in advance of election day.

Perhaps those registering on voting day aren’t “dropkicks”, as David Seymour suggests, but rather the victims of data mismanagement under an increasingly overworked, decreasingly democratic government.

So why the sudden mass migration of voters to the dormant roll? Why are people who have not moved house in years being affected? And if the Electoral Commission was doing their due diligence in making contact, why are so many of us confused?

It’s not my place to make your speculations for you. But seeing as te Pāti Māori are already pursuing investigation and legal action against the Crown, the main thing we can do is make sure our friends and whānau are aware of the possibility that their enrolment, whether from the last few months or decades ago, has gone AWOL.

You can check your enrolment’s status here:

If necessary, information on casting special votes in person can be found on the council website for your electorate.

(he/him)

The future of postgraduate representation at the university remains unclear, with a funding cut to the Post Graduate Student Association (PGSA) enacted for 2026, and VUWSA’s attempt to step in stymied.

The PGSA has struggled for a while now. The organization has little funding and is reliant on volunteers, meaning its ability to provide steady services year on year is limited.

Furthermore, the PGSA focuses primarily on community building, which has come at some expense to its advocacy role. Positions on various boards for postgraduate representatives have experienced ongoing vacancies. This means certain post-graduate course reviews, for example, have no student representation.

VUWSA, who represent undergraduates on these boards, wanted to step in to fill the void.

VUWSA wanted funding—through the student service levy—for a Postgraduate Officer on the executive, and a staff member to support them.

Unfortunately for VUWSA, the Student Levy Advisory Committee decided to only fund VUWSA’s executive member, who would work 15 hours a week.

PGSA Vice-President Events Vladislav Ilin was unimpressed by the decision to only fund an executive member.

“If that person gets busy with their Ph.D or masters, then the position might not be as effective than if you had someone working full time [on postgraduate representation] with KPIs to hit.”

To make matters worse, the position ultimately went unfilled during VUWSA’s executive elections. VUWSA CEO Matt Tucker says VUWSA has options, including holding a by-election next year for the position, or hiring someone to work as the Postgraduate Officer without executive voting rights.

PGSA meanwhile, also sought $68,000 from the Student Levy Advisory Committee to continue their community building while hiring staff to support their executive, and to reduce their reliance on volunteers. They got $15,000.

“They underfund us, and volunteers run out of energy and steam. When that happens, PGSA fails, and there’s no one to represent postgrads”, said Ilin.

“And so the funding gets cut further.”

Illin and his fellow PGSA Vice-President Mariel Lettier think PGSA could only fund one event each month next year, after admin costs are factored in.

This raises the question: how important is community building?

Both Tucker and Lettier agree that, for postgraduates, it’s vital. Postgraduates are predominantly older, foreign, and lack connections in Wellington. If you’re doing your Ph.D as an immigrant in your forties, then there’s not a whole lot of common ground between you and a 19-year-old undergrad from Wellington.

Tucker meanwhile notes how universities like Cambridge and Havard are renowned for their postgraduate culture outside of the classroom.

All of this leaves postgraduate representation in a state of limbo. VUWSA has some—but not an ideal amount—of funding for it, but no staff, exec or otherwise. PGSA’s community building will happen at a reduced rate. The resulting situation is one no one is happy with.

“I’m not sure if what’s happened is necessarily better than the status quo,” said Tucker. “Because with PGSA’s funding cut, they may not choose to do certain things.”

“If they don’t, who will?"

Henry

Broadbent (he/him)

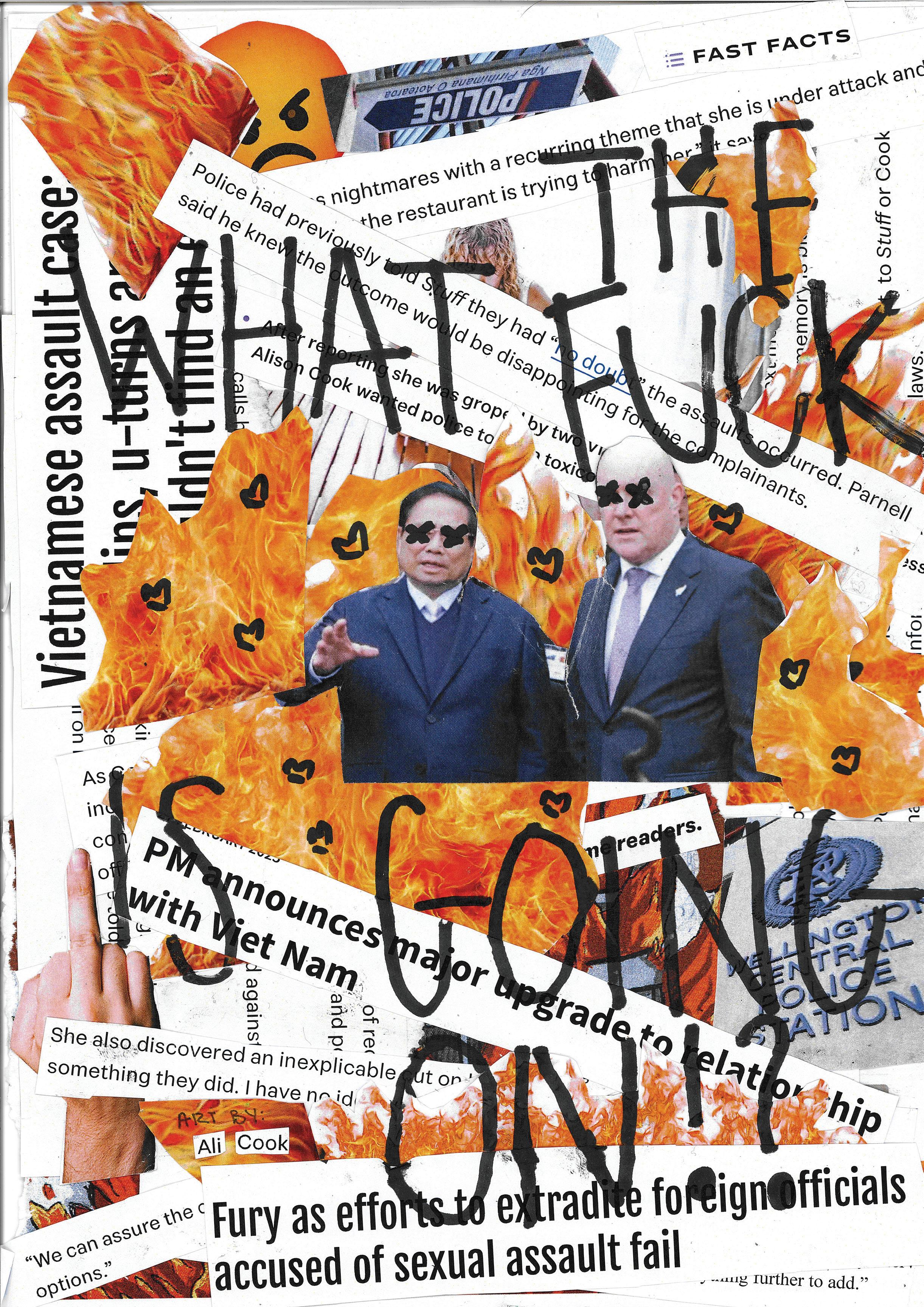

In March 2024 Ali Cook, then 19, was sexually assaulted by overseas officials, members of a delegation representing a Vietnamese policing agency: the Vietnamese Ministry of Public Security. By the time police in New Zealand had established their identities, the men had left the country. New Zealand and Vietnam do not have a bilateral extradition treaty.

In the ~18 months since, Cook has chosen to go public with her experience, in an effort to obtain extradition, and justice. You can read her story, in her words, on page 18, under the title: Tough on Crime, Except When It’s Me.

Much of the reporting on Cook’s story has focused on the question of obtaining justice in the absence of an extradition treaty. On October 2, Stuff reported that the New Zealand Police would not pursue extradition, deeming it “impossible.”

This is despite precedent: the extradition of a Malaysian ex-diplomat in 2014 to face charges of indecent assault in New Zealand—the same charge the men in Cook’s case face. New Zealand and Malaysia also do not have an extradition treaty. In March 2025, the New Zealand Police and the Vietnamese Ministry of Public Security signed an agreement to cooperate on “transnational crime”.

There is another, less headline-grabbing element of Cook’s experience that has led her to seek Parlimentary support: the absence of readily available, publicly funded, non means-tested legal advice for survivors of sexual assault.

Sexual assault survivors in New Zealand have for years reported interactions with an opaque, procedurally complex, and frequently retraumatising justice system. 2021 saw the unanimous passage through Parliament of the Sexual Violence Legislation Act, a significant law reform that altered key elements of the court process identified as likely to retraumatise survivors.

Changes included: enshrining alternate methods of providing evidence; ensuring survivors previous sexual history with defendants is largely off-limits, and; establishing a requirement for judges to actively dispel myths and misconceptions surrounding sexual violence within the jury. Access to privacy, and protection from excessive cross-examination, are also included in the Bill.

This legislation has broadly been seen as a significant improvement, but must be recognised as merely an initial step. Marama Davidson, in a 2021 press release for the Green Party, described the Bill as: “a bare minimum.”

In a New Zealand court setting, sexual assault survivors occupy the position of witness, and will be caled upon for evidence and an impact statement; prosecution itself is taken by the Crown. Alleged

offenders—people accused of sexual violence—are defendants. This means that those accused of sexual offences in New Zealand will, in almost all cases, have access to legal aid and representation in court. Crown prosecutors have the resources of the state. A survivor, by contrast, must navigate the court system without advocacy, representing themselves—unless they can afford to pay for a private lawyer.

To Cook, this represents a glaring omission in our court process for survivors, and a gap that must be closed. This has driven her to produce a policy brief, titled The Case for Independent Legal Advice (ILA) for all Survivors of Sexual Violence. She hopes that it can find a sponsor in Parliament and become a Members Bill, addressing what she sees as an urgently lacking element of our legislation.

The implementation of free, independent legal advice for survivors of sexual violence, Cook notes, has been successfully trialed and implemented in comparable jurisdictions. Programmes are already in place in parts of Australia, Scotland, England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Each of these states has the same common-law basis to their justice system; the successes of these programmes elsewhere makes the absence of any similar initiative in New Zealand particularly conspicuous.

The need for such measures is undeniably acute; sexual violence rates in New Zealand are staggering. A study published in The Lancet in May compared rates of sexual violence in over 200 countries across the last thirty years. Though it holds a specific focus—sexual violence experienced when people are teenagers—the study found that, in New Zealand, ~30% of women and ~20% of men have experienced sexual violence. Globally, those figures are 18.9% and 14.8%, respectively.

Combine that data with what we know about the rate of attrition in sexual assault cases in New Zealand courts (by some estimates only 1% of cases reach conviction), the epidemic of underreporting, and vast existing legal barriers; a stark picture begins to emerge.

A June 2025 Report from the New Zealand Law Society identified significant barriers to accessing justice in New Zealand, and a widespread perception that “in reality, not everyone is equal before the law because not everyone has equal access to the law.”

A legal system is difficult to access and difficult to understand is one that is definitionally unequal. For Cook, addressing this problem seems easy, even obvious. To her, it is less a pioneering effort to make change than something long overdue.

“No survivor of sexual violence should be forced into exhausting self-advocacy just to be heard. Independent legal advice would have spared me that burden. Survivors deserve a system of redress that is simple, accessible, and fair—and it’s time to make that a reality.”

Phoebe

Robertson (She/Her)

When first-term ACT MP Laura McClure stood in Parliament and held up a blurred, nude AIgenerated image of herself, the stunt landed with a jolt. She had deepfaked her own likeness, she says, to force colleagues to confront how easily such images can be made—and how New Zealand law hasn’t kept pace.

McClure did not imagine a career in politics. After university she trained as a pharmacy technician, then spent nearly two decades in her family’s health-and-safety business, gravitating to ACT over time on small-business issues and the End of Life Choice debate. “It wasn’t a chosen career path,” she says.

Deepfakes entered her world through school visits in her education portfolio, where principals and parents began flagging cases. One, she says, involved a Year Nine girl in Auckland— just 13—who was deepfaked and later attempted suicide. The gendered nature of the abuse, she adds, is unmistakable. “Someone has to do something.”

Her members’ bill aims to make it explicitly illegal to create or distribute synthetic sexual images intended to harm a person—closing what she describes as a glaring hole in the Harmful Digital Communications Act (HDCA).

Sharing real intimate images without consent is already a crime; using someone’s face to fabricate them, she argues, can be “far more damaging,” yet is not clearly outlawed. To her knowledge, there have been no successful prosecutions under the current framework for deepfakes.

Rather than chase the technology, McClure borrowed from South Korea’s behaviour-based approach. Regulating the tech is “whack-amole,” she says; the image she showed MPs took minutes to make on a free site with a couple of clicks. “Are you 18? Do you have consent? Done.” The bill, therefore, targets the act of weaponising synthetic images, not the tools themselves.

Getting any members’ bill heard is a lottery— literally. Proposals sit in a “biscuit tin” and rely on the ballot to be drawn. McClure says she deepfaked herself to attract attention across the House. It worked, but it wasn’t easy: “I’m pretty new… it was terrifying,” she says of showing the image in the chamber.

Since then, she’s found unusual allies. McClure says MPs from multiple parties reacted with surprise that the conduct isn’t clearly illegal and expressed willingness to act. The Greens, she says, nearly co-signed before stepping back; te Pāti Māori has been supportive. “this isn’t political. Anyone can be affected,” she says. Her lobbying pitch stresses urgency and asks colleagues to prioritise this bill over their own in the ballot—no small ask in a system where backing one bill can mean sidelining another.

What about ACT’s free-speech instincts?

McClure argues the line is bright. “We already criminalise sharing someone’s nudes without consent,” she says. “Saying it’s okay because it was made with technology makes no sense.” She insists the bill protects legitimate, creative uses of AI by focusing on malicious behaviour: “We want to protect people who use it for good.”

With a maximum penalty around two years, criminalisation would principally send a signal and unlock support pathways. Schools that have dealt with cases lack consistent victim services precisely because the conduct isn’t clearly a crime, she argues. Naming it as such enables police, victim support and other agencies to act coherently. “It says to young people: this is serious.”

McClure places her bill within a broader, overdue update of the HDCA, which she notes is roughly a decade old. Technology will keep moving—today’s deepfake will be tomorrow’s something-else—so she favors faster, periodic reviews to close new loopholes before harms metastasise.

For students, the call-to-action is immediate: email MPs and lend your name to petitions urging the Government to add the issue to its work program, McClure says. And if you’re targeted, do not go it alone—contact Netsafe for takedowns and support, and talk to police. Even under current law, some remedies are available. “Please reach out,” she says.

McClure’s gambit—using a fabricated image of herself to argue for a real law—captured attention because it compressed the issue into a single, unsettling truth: if an MP can be deepfaked in minutes, so can anyone else. Her bet is that Parliament won’t wait for catastrophe to prove the point.

Phoebe Robertson (She/Her)

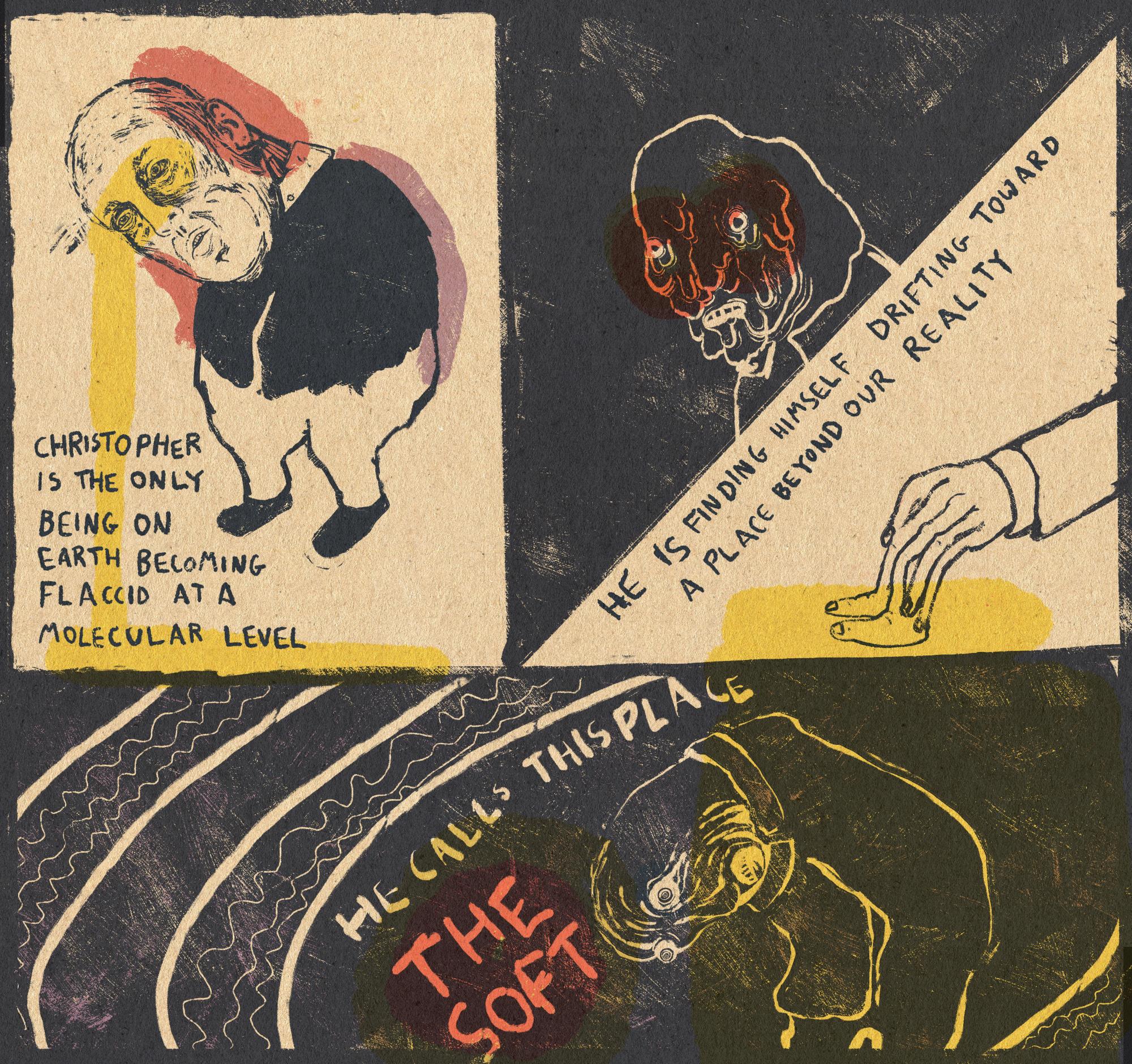

By: Brahms Hole

There’s this opinion piece I’ve had in my mind for a while; since starting back at Salient really. But I’ve been hesitant. What does it mean to beat a dead horse? What does it mean to consistently see men in our headlines, when according to the UN, one woman or girl is killed every ten minutes by an intimate partner or family member?

The trigger for this was small: a few days ago, YouTube took down an AI channel which uploaded nothing but hyperrealistic videos of women, first begging for their lives, and then being shot. The channel had over a thousand subscribers. The videos were made with Google’s new AI software that was supposed to be safeguarded; women’s suffering slipped under the radar.

On February 8, 2025, NDTV reported that nearly 100 women were enslaved in Georgia, tricked into what they thought were surrogacy jobs. Instead, they were injected with hormones, anesthetised, and had their eggs harvested once a month, their bodies treated as warehouses for profit. A “farm.” A farm of women.

What unites these stories—the women wired into egg-extraction machines, the AI avatars executed for clicks—isn’t simply violence. It is the sense that women’s worth is endlessly negotiable. That our suffering is a currency: traded for views, votes, profits.

It is easy to tell ourselves these are outliers. Georgia has its mafia problem. The internet has its radical weirdos. But what is the common denominator? That women, when reduced to symbols, are infinitely expendable.

And what about here, in Aotearoa? We have our own ledger. We average one woman a month killed by a current or former partner. Our Family Court is so clogged that survivors wait years for basic protections. We had the Roast Busters scandal; we had Grace Millane’s murder turned into a pornography of trial detail. Every country finds its own flavour of the same pattern.

We like to call ourselves world leaders in gender equity. In 1893 we became the first country in the world to give women the vote; we put Jacinda Ardern on international magazine

covers. But what is the worth of a woman’s life here, when Māori women are three times more likely than pākehā to be killed by an intimate partner? When frontline women’s refuges operate on bake-sale budgets while Corrections pours millions into prison expansions? When a violent man can be bailed to the same street as his victim because there’s “nowhere else to put him”?

So when I ask “What is our worth?” I don’t mean as individuals—your mother, your girlfriend, your flatmate. I mean systemically. What is the value of a woman’s life, when companies can profit from making fake snuff porn of us, when gangs can extract our eggs like battery hens, when politicians are targeted and receive almost no media attention?

Worth is not abstract. It is measured in clicks, in court delays, in the speed of a police response. It is measured in the difference between how quickly Meta will pull down copyright infringement versus how slowly it removes videos of abuse. It is measured in the fact that Google can create AI capable of faking executions, but not one capable of spotting misogyny.

I keep circling back to politeness. The machinery of disbelief is greased by it. We excuse, we downplay, we say “this isn’t who we are.” And yet it is. It is who we are until we choose otherwise. Until women’s deaths and degradations are not just tragedies, but national emergencies. Until tech companies, courts, and parliaments are made to answer not just for their oversights, but for the premise they operate on: that women’s lives are optional margins in the spreadsheet.

What is our worth? If you take the headlines at face value, it is less than a vote, less than an ad impression, less than a clutch of harvested eggs. The only way to shift that balance is relentless attention. Refusing to let the horror pass as background noise. Naming it, over and over, until the cost of ignoring it outweighs the cost of change.

Because the dead horse is not dead. It is us. And every day, the world tells us what it thinks we’re worth. The only question is whether we keep agreeing.

Across

6. the pā

8. wāhanga o te tau/season

12. tēnā hakarongo mai

14. tree, star of the dead

17. Māori language commissioner

18. te __ o te mano

19. kākā

1. 90 mile beach

2. māori word for door

3. māori word for breeze

4. meeting house

5. te __ o te marea

7. poho

9. te __ o te tini

10. basket of sacred knowledge

11. basket of the arts

13. god of evil

15. basket of ancestral knowledge

16. rata, Waitangi Tribunal

18. turituri

1. What’s the name of the wharenui of our marae?

2. What is the Māori name of the northernmost region of the country?

3. Who is the god of Earthquakes?

4. Who won Te Matatini in 2019?

5. What was the name of Maui’s grandmother who gifted her jawbone to him?

Nei rā te mihi ki a koutou kua whai wāhi ki te kaupapa i te tau nei hākoa ngā aupiki, ngā auheke nōki – nōku te maringa nui. this is your te ao Māori Editor 2025 signing off, good luck on exams and don’t forget: Free Palestine and vote YES to Māori Wards!

taipari taua (Muriwhenua, Ngāpuhi)

As we head into the final stretch of classes for trimester two, I wanted to take a moment to pause and reflect on how the year has been. Initially I thought it would be a fun idea to speak on my own experiences. Instead, I was lucky enough to be surrounded by a wonderful bunch of tauira in the wharekai of Ngā Mokopuna. While sitting down with them, i was able to ask about their experiences, how the year has been for them, what they’re looking forward to over the break, and what excites them about the year to come.

I spoke with:

Rawinia, first-year laws and Māori Studies

Tui, first-year Political Communications

Hinewairua , second-year Māori Studies and i ntercultural Communications

Sophia, third-year Māori Psychology

Kaitlyn, fifth-year Honours Sociology

How has this year been?

For rawinia, who moved here from tāmaki-Makaurau to start her first year of law and Māori studies, she mentioned the year has been “good, super eventful”. Uni life can be challenging for many, but she highlighted the importance of being social and making connections to help her through this year.

Tui, another wonderful first year, described it as “very much treading water.” This is how first year students can often feel— the constant juggling of assignments, while trying to keep your head above it all. Still, she admitted it’s “pretty cruisy compared to high school and having a job”.

In her final year of Honours, Kaitlyn kept it real while commenting on Tui’s view of the year by agreeing with the statement, saying “Me too, it’s definitely like I’m still treading water”.

Sophia, now in her third year, reflected on the growth she’s had this year. “I’ve got a better grasp on balancing work and uni this year, and I feel so much more confident in myself and especially in Māori spaces. i’ve put myself out there a lot more than last year, I’m thankful and feel at peace—socially, at least.”

For her, the community within the Pā has been central to how supported and connected she feels to her fellow Māori tauira.

“Long but eventful,” is how Hinewairua put it. She agreed with the others that social connection really helped her through the year, stating that “without my friends, it’d be boring but I’m glad for the experiences I had this year”.

What are you looking forward to over the break?

After months and months of lectures, deadlines, and readings, everyone was in agreement about resetting themselves and taking time for whānau and friends.

Tui said the break is about “resetting and getting mentally prepared for the following year.”

For Rawinia, it’s all about “taking a mental break, I want to have time for myself again”. She’s also excited about heading up to gisborne to see her māmā; once she’s back she’s moving into a new flat with her best friends. “I’m finally going to have time to myself without feeling super guilty about being on TikTok as well!”

Sophia wants to spend her summer nurturing her soul with raranga, art, and all the “things I love doing but always run out of time for during the trimester.” She also mentioned going home far North, and spending proper quality time with her whānau.

And for our lovely Miss Honours Student, Kaitlyn has one very clear goal for her break “I’m excited to close Zotero.” Iykyk!

With the exhaustion of the current year still very fresh, all tauira spoke about what’s on their minds for next year and what’s motivating them to keep moving forward.

For Hinewairua, the finish line is within reach: “Next year, I’ll be closer to getting my degree, my final year.”

Tui hopes to be “more involved in my community: I really want to keep that connection I have this year, and I hope to dive into it more next year.”

Rawinia is focused on getting herself into her second year of law (she definitely will!)

Sophia has her eyes set on both studies and community. “A successful final year of my bachelor’s, I also really want to serve our tauira Māori in any way that i can, representing them and giving back to the community that has carried me through this degree.”

Kaitlyn on the other hand, she can see the moment clearly “I’m going to be walking across that Ātea and getting my degree.” What I loved the most about sitting with them was their combined sense of hope for the year ahead and their mix of honesty, and humour. While they agreed they’ve been in survival mode the last couple months, they shared the amount of growth they’ve experienced. All of them reminded me that the experiences we have as students aren’t just about classes or grades; they are about the unique experience we have as Māori students, and how we find strength in each other, in our whānau, and the spaces we have on campus.

As this year closes, I feel lucky to have gained a close friendship with these girls throughout the year, but also lucky to have listened to their journeys. Even though this year is wrapping, for our tauira Māori and all of us, while this chapter closes, the next chapter is only just beginning.

TW:

Editor’s note: the below personal essay contains detailed descriptions of sexual assault, mental illness, and the response by both the police and government. It is a heavy read, but it is an exceptionally important one. I personally have never read an essay like it, and working with Ali to put it together over the past month has been one of the biggest privileges of my life. Please, continue carefully, and continue kindly.

Editor's update: the day before we published this issue of Salient, it was announced that the New Zealand Police were no longer pursuing extradition. This essay has not been updated to reflect this; as we believe it is powerful as is.

On March 4, 2024, I was sexually assaulted by members of a visiting Vietnamese delegation. I was an international student from the U.S., far from home but trying to build a life in Aotearoa, a place I believed could be safe for me. The officials—members of Vietnam’s Public Security Ministry, a police agency in their country—were in New Zealand visiting the Royal New Zealand Police College. That same year, in the same delegation, one of the men was later arrested for sexual assault in Chile.

This isn’t just about me. It’s about the legacy of the Ministry of Public Security, a system that shields abusers and leaves survivors to piece themselves back together in silence.

In the months since, I have found myself on the news, my name attached to a case where the ability to even give a statement was constrained by diplomatic ties and political interests. Even the former editor of Salient published a half-ass article about my case without ever consulting me—despite the fact that I am a student at Te Herenga Waka, and this is my life.

So why write this now? Why here? Because until now, I have only shared the full weight of this experience with my therapist. Because even though Stuff reported on my case with care and integrity, mainstream outlets rarely give survivors the room to be vulnerable, to show the messy, painful reality of what comes after. Salient—with the support of its new editor—has given me that platform. This is a wake-up call. The way sexual assault victims are treated is unacceptable.

I write this not just to recount what happened, but to ask you—the reader—to listen differently, to sit with discomfort, to reconsider how you respond to sexual assault allegations in the future. What follows is not polished, not linear. It is my attempt to show you what this has done to me. It’s hard to describe what that time was like, so I’ll give it a shot.

What follows is not polished, not linear. It is my attempt to show you what this has done to me.

I knew I had to go to the police when the assault happened. For me, it wasn’t a question—it was a promise. This wasn’t my first experience with sexual assault, and years earlier I had vowed to never let it happen without consequences again. Now, it was time to keep that promise.

But this case carried an extra layer of fury. The men who assaulted me were politicians, visiting on official business. Around the world, there’s a pattern: powerful men exploit women and walk away untouched. Too often, those accused—or even charged—remain in office, unscathed. Reporting the assault wasn’t just an act of self-protection; it was a refusal to silently accept the status quo.

On March 6, I walked into the Wellington Central Police Station I felt as though I were watching myself from a distance dissociated, yet clinging to a fragile thread of hope. I carried a small paper bag of evidence: my clothes, and the neatly folded bills from the night of my assault. The bag weighed more than it should have, as if it held not just fabric and money but the unbearable weight of everything I could not set down—the shame, the fear, the terror.

The waiting room was empty, oppressively quiet the kind of silence that presses into your ears until it becomes its own sound. I tried to fill it with small, meaningless jokes, forcing out laughter that sounded hollow even to me. Every attempt dissolved into the stillness, leaving only the hum of fluorescent lights and the relentless thud of my heart.

I sank into the hard plastic chair as if I carried two bodies: one, the corpse of the girl I had been; the other, the bruised, breathing shell that remained. The weight was unbearable. An ache no posture could relieve. On my lap, the paper bag lay like an accusation silent, damning, proof that I could neither forget nor explain. I looped the night in my mind again and again, desperate to locate the single mistake, the invisible choice, that might have spared me.

But the past wouldn’t budge. I stood under the shower until the tiles steamed and the water turned cold, scrubbing at my skin until it blistered in patches. I screamed into a towel, into the walls, into the drain—until my throat gave out and all that remained was a rasp. Still, the memory stayed lodged in my body, like a second skin. Reporting felt like the only thing left tethering me to a sense of control—a final , trembling attempt to be heard. I clung to a fragile hope: that someone, anyone, might see me, clearly believe me fully, and act.

An officer led me to a small interview room. I sat across from him, fidgeting as he began to ask questions each one a scalpel. The hours stretched endlessly. I drew diagrams. I recounted the assault again and again. I handed over every scrap of evidence I had. Each repetition felt like both survival and surrender. I needed to be believed. I needed to matter.

But my memory was fractured. I tried to piece it together for the detective: a room thick with alcohol and sweat. Hands where they shouldn’t have been. My voice swallowed by noise. Time bent strangley—seconds folding into themselves, stretching into endless loops. My body froze, unresponsive, while my mind screamed. And then: blankness. A void so deep it felt like falling through air, endlessly, with nothing to grasp.

When I left the station, I felt a fragile sense of relief. Maybe now something will happen. Maybe justice. Maybe I could reclaim a fragment of the life that had been taken from me.

A week later, the phone rang: The men who assaulted me had already left the country. I was told that action would be taken domestically, and that I can expect regular updates. By November, nothing had changed. My case was dismissed.

I hadn’t heard from the police in weeks. No domestic punishments were being enforced. The silence was deafening—not just bureaucratic, but moral. I began to see my case not only as a personal struggle, but as part of a larger, systemic failure. Why do men—especially men with political power—get away so easily?

I began to see my case not only as a personal struggle, but as part of a larger, systemic failure. Why do men—especially men with political power—get away so easily?

In New Zealand, the numbers are stacked against us. Between 2017 and 2023, just 42 percent of the 55,786 reported sexual violence cases progressed to court, and only 12 percent resulted in conviction. Meanwhile, 89.9 percent of sexual assaults went unreported. That means only 4.2 percent of victimisations led to charges, and just 1.2 percent ended in conviction. These figures didn’t just feel systemic—they felt personal. I refused to let my case become another statistic, another instance of a politician escaping accountability. I wanted to shift the narrative—to show that no one, not even a diplomat, is above justice.

So, I reached out to Stuff. If nothing else, I could make my allegations public. I knew that publicity often sparks action, but more importantly, it offered exposure. Maybe prosecution wasn’t possible. But I could still make sure my story was heard.

I sat outside the Kelburn Library and typed an email, the subject line stark and deliberate: “My Story of Diplomatic Misconduct in NZ.” Not long after, I was connected with a journalist named Olivia.

Olivia and I planned to meet on November 5. The night before, I stayed up watching the U.S. presidential election unfold. I watched the votes being counted, state by state, and when the result was announced, I wept. A man found liable for sexual assault had been re-elected as president. Again, I was brought to the same question: Why do men get away so easily—especially men with political power?

...when the result was announced, I wept. A man found liable for sexual assault had been reelected as president.

The next morning, I woke with red, puffy eyes. My mind reeled, trying to make sense of how half a country—my country—could still support him. But I had no choice but to get ready. Olivia was on her way. The moment of sharing my story had finally come.

Olivia sat with me for a long time. She didn’t rush. She asked questions gently, listened carefully and made sure I felt safe. But inevitably the moment arrived. I told her what happened.

The next step was to secure my police file under the Privacy Act—to have documented evidence of the assault before the story went public. I submitted the request on November 8. Under protocol, the police had twenty working days to respond.

In the weeks that followed, I relocated to Auckland to begin my summer internship. The move also brought me into contact with Paula, another journalist at Stuff. We arranged a meeting. Like others before her, she asked about my story—but unlike most, she first made sure I felt safe. It was a small courtesy, but one I rarely received. I was grateful.

Paula explained the next steps: the story was moving forward, but we were still waiting on the police file. By December 9, the statutory response period had lapsed. Still, I’d heard nothing. Frustrated, I rang 555 to follow up. To my disbelief, the dispatcher couldn’t even locate my request—despite the confirmation I’d received weeks earlier.

The next day was Flatmas. After a Secret Santa exchange and a backyard sausage sizzle, my phone buzzed. It was Paula. She wanted to come over—with a camera. I knew instantly what that meant. I’d been bracing for this moment for weeks.

I tipped back the last of my prosecco and ran upstairs. My flatmate followed, helping me choose an outfit and checking every detail. Twenty minutes later, Paula was at the door—with a camera crew.

We turned the lounge into a makeshift studio. Lights of every shape and hue filled the room. A microphone was clipped to my collar, its cord snaking down my blouse; the prosecco wore off immediately. It was time.

Paula began with questions about my assault. I recounted the story as best I could. Then, she told me something I hadn’t heard before. In a statement to Stuff, the Police said they had “no doubt” the crime occurred. They didn’t question it. They believed me.

I froze.

This was the first I’d heard of it—news about my own case, shared with the public before it was shared with me. The police should have told me first. That kind of affirmation, that kind of belief, should have come directly.

Then, she told me something I hadn’t heard before. In a statement to Stuff, the Police said they had “no doubt” the crime occurred. They didn’t question it. They believed me.

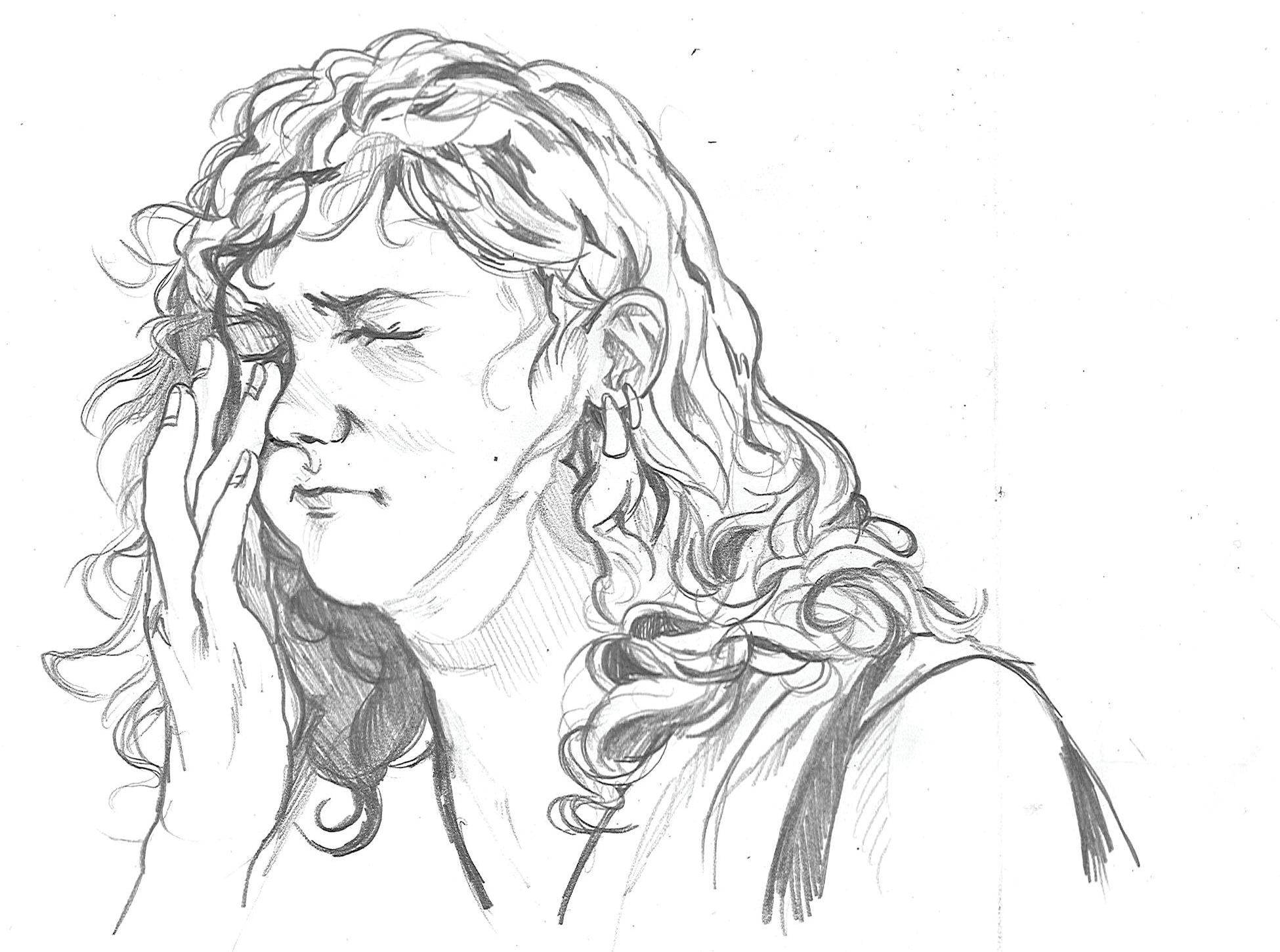

When the interview wrapped, the photographer took portraits around the flat. I asked, half-joking, if I should smile.

“No,” came the immediate reply.

But smiling is my default—a reflex, a mask I wear without thinking. I paused, swallowed the instinct, and let the corners of my mouth fall flat. I could turn it off, at least for the camera.

Once the gear was packed and Paula had left, I tried to rejoin Flatmas. But something had shifted. I excused myself and went upstairs, spending the rest of the day alone, turning over the same thought: what will happen when this goes public?

Night gave way to December 11. Paula had told me the story would run the next day. I woke up with a single sentence in my head: Welcome to your last day of freedom. I knew the risk of coming forward. I knew how easily I could be torn apart.

All I wanted was to move through the world one last time, unremarkable and unseen. I wandered the mall, ate lunch alone, and sat for hours in a café. It felt like a farewell to being ordinary—a final day of existing without a headline attached to my name.

The next morning, December 12, my alarm buzzed at 5:30. My heart was already racing before I opened my eyes. I reached for my phone. The screen flared to life, flooded with messages—people recognising me from the article. The story had been live for just thirty minutes, and already, I was being seen.

Later that morning, Christopher Luxon was discussing my case in a press conference. Winston Peters dodged questions about me. The police had reopened the investigation. Police Commissioner Richard Chambers said that extradition was now being actively pursued.

Something was finally happening.

By December 13, under mounting pressure from the press, police located my privacy request—the very one they had previously claimed couldn’t be found. But none of my files were released. The investigation was now “open’, and that meant access was denied.

The only option offered was to view the CCTV footage from the police station. Once again, I felt powerless. I couldn’t freely read my own statements, nor watch the footage of my own assault on my terms.

Not long after the story broke, I went to a flat party. A guy approached me—I didn’t recognise him, though he insisted we’d met before. Within seconds, he was probing into my trauma, demanding details I had chosen not to share. I managed to slip away before he could push further.

Relief was short-lived. Soon after, an old friend cornered me, led me to a bathroom, and locked the door behind us. She, too, pressed for answers.

I left the party feeling deflated. Conversations that should have been light—our summers, new jobs, the small victories of life—never happened. Instead, people saw only my trauma, as if it had eclipsed every other part of me.

Journalists from all over the world began calling relentlessly. One night, around 1 a.m., I was on the couch, drunkenly devouring McDonald’s, when my phone rang. I glanced at the screen and thought: Really? Now? But I answered anyway. I felt like I had no choice. Giving a statement felt like the only way to reclaim a fraction of control over a story that was otherwise ruining my life.

Giving a statement felt like the only way to reclaim a fraction of control over a story that was otherwise ruining my life.

Slowly, my days were consumed by interviews and endless retellings—from journalists on the phone to strangers in the street. My trauma became inescapable. There was no refuge. I was a trauma-filled girl in the headlines, nothing else.

Leaving the house became impossible. Glances from strangers no longer felt neutral—they felt like accusations. Everywhere I went, I sensed it: people weren’t seeing me. They were seeing my trauma. Eventually, I stopped going out. I developed agorophobia—an anxiety disorder marked by an intense fear of people and public spaces (or so my therapist told me). I ordered groceries to my door, worked from home, and lived off endless Uber Eats. I invented excuses to avoid socialising. Still, a part of me craved control. So, reluctantly, I did what I’d promised myself I never would: I looked at what people were saying about me online.

I was alone in a Wellington hotel room the first time I checked. Perched at the edge of the bed—laptop on my lap, phone in hand, iPad beside me—it was a full-scale, multi-device operation. The MTV Music Video Channel played in the background, a surreal soundtrack to the moment. A bottle of red wine was on its way, a small comfort for what came next.

I opened my laptop and logged onto Twitter. Tweets about my story had appeared from all over the world. My hands shook so violently I could barely type. My heart pounded, every beat loud in my ears. I clicked open the comments, bracing myself—wishing I could look away, but unable to. The first comment hit like a fist: “Damn. I don’t get this chick who looks like she’s pushing 40, claiming to be a 19-year-old student, looking like she’s had four kids. Nobody is that desperate for someone like you.”

My chest froze. My lungs wouldn’t expand. My fingers, hovering over the trackpad, trembled so violently I felt detached from my own body. My mind went blank, then flooded with nausea, panic and shame. A tear slipped down my face and burned; something in my stomach felt hollowed out, as if it had been ripped away. I kept scrolling. I couldn’t stop. Each new message was a blade along the raw edges of myself: “Too ugly to have been assaulted.” “A pig.” “No one would ever want someone like you.” My body flinched with every word. There was doubt, and there were accusations that I was lying for attention or politics—but threaded through that chorus were the other, darker voices. A small number defended the men who had assaulted me; one comment that still sticks is, “It’s what we do, rape someone without talent or virtue like you.”

Others praised the supposed irresistibility of “curvy Western women,” saying they would have done the same. Those messages, many of them coming from accounts based in Vietnam, felt like a different kind of violence. And then a few people went further, fantasizing about capturing me into sex slavery, posting sick, detailed plans. Then the terror escalated. I was cast as an evil American capitalist, a phantom blamed for wars I never fought and histories I had no part in. My body shrank; my breaths came in sharp, shallow bursts. I would dig my nails into my palms, desperate for something to hold onto.

My chest froze. My lungs wouldn’t expand. My fingers, hovering over the trackpad, trembled so violently I felt detached from my own body. My mind went blank, then flooded with nausea, panic and shame.

It’s hard to describe what that time was like, so I’ll give it a shot with loose and fragmented moments: In the months that followed, messages flooded my personal accounts graphic, unrelenting, clawing at me. Every ping of my phone made me jump. Sweat pricked my scalp; my teeth clenched until my jaw ached. I pressed my forehead to the cold desk and rocked, trying to make sense, but sense had abandoned me. The world had become a predator: patient, cruel and endless.

The ACC process required a four-hour psychological evaluation—how fucking lame. But buried inside the clinical language was something unexpected: a record, a mirror: “Ali’s independence has been shattered,” it read, “by the sexual assault that occurred on the other side of the world in a place she was trying to make safe for herself.” Reading that, I saw myself. My thinking destabilized by any trigger, my mood sliding from sadness, to helplessness, to hopelessness. The report called it “depressive symptoms.” I called it trying to stay alive inside my skin.

...buried inside the clinical language was something unexpected: a record, a mirror: “Ali’s independence has been shattered,” it read, “by the sexual assault that occurred on the other side of the world in a place she was trying to make safe for herself.”

I closed my laptop and slid to the floor; the carpet was rough against my knees. The screen went dark, but the words burned behind my eyes. I grabbed the nearest bottle and drank until the walls swayed. I swallowed whatever pills I could find, chasing the fantasy that one might contain an answer, or a cure. I scoured the bottom of every glass and capsule for logic—anything that could explain how strangers could slice me open with a sentence and walk away unbothered. The more I reached, the emptier it became. Only the slow, relentless thrum of doubt remained.

“Ali describes holding an enduring sense of ‘what’s the point in life’ since the recent assault,” the notes continued.

Maybe they were right. Maybe I was too ugly. I replayed the comments until they fused with my own thoughts and their contempt sounded like my reflection. The idea took root: if I could change my body, my face, my voice, my mind—maybe I could change their judgment. Maybe if I were different, the world would finally believe me. I stopped eating. Hunger hollowed me until even breathing scraped like sandpaper, but I welcomed the ache. I wanted a body beyond doubt—thin, beautiful enough to make the violence undeniable. I understood hunger might kill me. I didn’t mind. I only hoped my corpse would be perfect enough to be believed.

“There has been little criminal outcome from either assault,” the report stated. I reread that line until the words blurred. No outcome. No justice. Just me—developing “features of traumatic anxiety.” Hypervigilant, the notes called it. Fearful of being harmed by anyone: the public, peers, even people I thought I should trust. The report noted that I had installed cameras in my flat, that I slept with the lights on. It was true. I lived in a permanent state of startle.

I poured every ounce of attention into my appearance—tracing the shadows under my eyes, the tremor in my hands—sculpting myself into something the world might call worthy. I rehearsed answers in the dark, sharpening every sentence until it bled precision. If I spoke smarter, cleaner, without a stutter, maybe they would take me seriously.

Months blurred into a ritual of self-erasure. I stood in front of the mirror until my legs shook, cataloguing flaws like evidence, peeling myself apart for a version of me that might be believed. Each time I stepped away, the verdict from the glass was the same: too ugly, too undeserving, too insignificant to matter.

As Christmas approached, the media attention that had once forced movement began to fade. And so with it, so did any sense of progress.

On January 23, 2025, the detective on my case called with an update—the first I’d received directly, as promised. Extradition, once a possibility when my case was in the headlines, was no longer on the table. The reason: the crimes, he said, were “not serious enough.”

The words gutted me. How could something be dismissed as “not serious” when it had shattered my life entirely? I broke down crying, right there on the phone. The detective sounded puzzled, almost uneasy. He offered no comfort—just flat finality that left me feeling completely powerless.

I hung up with the detective and texted Paula and Olivia immediately.

I was inconsolable.

Extradition, once a possibility when my case was in the headlines, was no longer on the table. The reason: the crimes, he said, were “not serious enough.”

On February 4, I was finally summoned to Auckland Central Police Station. The police had promised me back in mid-December that I would be allowed to view the CCTV footage of my assault, and now—nearly two months later—they were making good on that promise. It was the only access I was granted. My case file remained sealed. The investigation, they insisted, was still “open.”

I was permitted to bring one support person. I chose Paula. And because I knew this was the only chance I had to prove to the world that my accusations were real, I agreed to let the viewing be filmed and eventually published. But the thought of actually watching what had been done to me filled me with dread. I knew exactly what I was about to see, and I knew the images would burn themselves into my memory forever.

The detective who led us into the small viewing room explained that most of the clips we were about to watch had been taken on the night of the assault, but one had been recorded the following day. Then he looked at me and asked if I was ready.

“Not really,” I said. “But I doubt I’ll ever be.”

He pressed play.

My memories of that night had always been patchy. Alcohol had been forced down my throat, and I’d become intoxicated frighteningly quickly. The hangover that followed was so brutal, so unlike anything I’d ever experienced, that I suspected my drink had been spiked. Still, fragments had stayed with me. I remembered my hair being pulled back as men poured whiskey into my mouth. I remembered an official shoving himself against me. I remembered, the next day, the confusion of discovering unexplained cuts on my nipples.

“I have no idea what happened,” I’d told Stuff at the time. “I know something bad happened.”

Now, here I was, being forced to watch it unfold.

The police had obtained around two and a half hours of relevant footage—fifteen separate videos in total, some captured by CCTV cameras, others filmed on a mobile phone. Eight clips, about forty minutes altogether, directly concerned me. They weren’t time-stamped, so it was impossible to know exactly when in the evening each clip occurred. Still, it quickly became clear why police later said they had “no doubt” that I had been assaulted. I sat in silence, gripping the edge of my chair, hating that what I was seeing matched everything I had feared. Eventually, I asked the detective if I could take a break. When he left the room, I turned to Paula and whispered that I hated being right.

The detective returned with water and tissues. He offered me a blanket, even a stress ball to squeeze. Small comforts against an unbearable truth.

The final videos were taken on a mobile phone inside a karaoke room, away from the CCTV cameras. A man sang, badly, in Vietnamese. The bright lights, his oblivious performance, created a jarring backdrop for what was really happening in that room, most of it just out of sight.

By the end of the footage, the evidence of repeated indecent assault was overwhelming. I asked the detective if I could have another minute. My chest was heaving, my pulse hammering visibly through my blouse. My body remembered the trauma even more fiercely than my mind did.

When it was finally over, Paula and I stepped outside into the heavy Auckland air. The cameras were waiting, just as I’d agreed, and this time I couldn’t hold it back. For the first time, I cried on camera.

When it was finally over, Paula and I stepped outside into the heavy Auckland air. The cameras were waiting, just as I’d agreed, and this time I couldn’t hold it back. For the first time, I cried on camera.

I’d kept myself composed for months. Every interview, every public appearance, every statement—I had forced myself into a posture of strength, determined to look unbreakable. I thought that was what it meant to lead, to advocate, to fight. But as the sobs shook through me, I realised something else: strength isn’t the absence of tears. Crying doesn’t make you weak. It makes you human. And in that moment, I felt painfully, undeniably human.

Through tears, I tried to explain what I had just seen. “It was like watching a horror movie,” I said. “In one sense, it’s almost affirming—I know now I was telling the truth, because I’ve seen it with my own eyes. But at the same time, it’s traumatising. It’s disgusting. I feel like every day I’m living in a mental prison. And they’ll never be in one.”

I feel like every day I’m living in a mental prison. And they’ll never be in one.”

What makes it even harder is that I don’t actually remember any of it. My mind locked the memories away, probably as a way to protect me, so the footage is the only version I’ll ever have. Watching it was disorienting—I could see myself, and yet it felt like looking at a stranger’s life. My body reacted instantly—heart pounding, hands shaking—even when my brain struggled to connect with what I was seeing. It’s a strange kind of betrayal, when your body remembers what your mind refuses to.

That gap—between memory and evidence—has been one of the most difficult parts to live with. I have to carry the knowledge of what happened without the memories that would make it real in the usual way. Instead, I’m left with fragments: the weight in my chest, the panic that surfaces without warning, the girl in the video whose pain is frozen on screen. She is me, and she isn’t.

Within a few days, the interview aired. For once, the reaction felt different. On Twitter, in messages, in conversations, people seemed to respond with genuine sympathy. Maybe it was the tears that did it. Maybe, for the first time, they saw me not as a symbol, not as a headline, not as a case file, but simply as a person.

Three days later, February 7, I was hungover and making slime with a friend when Paula called.

An extradition file was being prepared.

What the fuck?

The day passed with a blur of whiplash and cautious relief. Finally, my sacrifices were pushing something forward.

But the call hadn’t come from the police. They hadn’t told me a thing.

In fact, I had to call my detective a week later to confirm that the extradition file was being prepared. He’d had a week to reach out. He never did.

It was a brutal reminder of their priorities. Information that shatters a victim goes straight to them, but when it benefits police optics, the press can have the story—just not the person at the center of it.

That was the last time I heard about extradition.

When Christopher Luxon broke his silence, it wasn’t to me. It was to the media. On February 27, speaking to media in Ho Chi Mihn City, and reported on by NZ Herald, he claimed he couldn’t “make public comments” for fear of prejudicing the investigation. He reassured the country he was “comfortable we have good levels of engagement between both systems,” that police “had some work to do” but were “actively meeting” in Vietnam. Comfort. Engagement. Work to do. Not justice. Not urgency. Not accountability.

I read those words over and over, searching for any indication that my life—my safety—was the priority. But it wasn’t about me. It was about optics, about maintaining diplomatic smoothness, about keeping headlines quiet. He didn’t say he’d raised my case with Vietnam’s officials, despite traveling there multiple times. He didn’t say extradition was a priority. He didn’t say my life mattered enough to disturb the fragile politeness of international relations.

Only weeks earlier, he had announced what he called a “major upgrade” to Aotearoa’s relationship with Vietnam—elevating ties to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership and promising a “shared ambition to expand cooperation and to do more together across a wide range of priorities.” That public pledge of closer, higher-level cooperation makes the silence on extradition feel sharper: if this partnership truly includes deeper political and law-enforcement ties, where does pressing for the return of alleged offenders fit into those “priorities”?

Is extradition of the officials in question one of these priorities? If not, how can this be reconciled with the Government’s repeated promise to be “tough on crime”? The contradiction is not abstract to me—it is the difference between being a constituency to be courted. and being a person whose safety requires urgent, uncompromised action. The government has a very large hand in extradition. And in my opinion, they’re doing a terrible job. My case crystallized what disenfranchisement means: not just silencing, but erasure. I was useful as a headline, a symbol, a line in a press release. But when real confrontation was required—when someone in power had to demand action—my existence became inconvenient. Disposable.

And yet, I couldn’t speak out. I needed the government. Strategically, I couldn’t afford to be cynical about someone I was dependent on. It’s now September, and I have no idea what’s happening with my case. I tried not to be political. But that became impossible. I am political—it’s who I am.

This is what disenfranchisement feels like—not just in the abstract, but in the daily, grounding reality of being silenced by systems that claim to protect you. I live here. I contribute here. I rebuilt my life here. But when it comes to decisions that shape my future, I am voiceless.

I came to Aotearoa to start over. I moved to Wellington at 17, it felt like a chance to reclaim my life after an earlier assault. And for a time, it worked. From April 2022 until March 2024, Wellington was a kind of utopia. I rebuilt myself here.

Then it happened again. And everything I’d worked so hard to restore was shattered. But I never considered leaving. Not once.

Aotearoa is my home. I won’t let anyone take that away from me. I fought to be here. I stayed because I love living here.

And yet, the cruel unfairness of it all still twists inside me. While I’m left scraping for control—remaking myself in the faint hope that someone might believe me—the men who assaulted me have faced no punishment. None. They continue to live normal lives. They go to work, maintain their high status, and navigate the world with ease. They have families—wives and children who love them, who trust them, and who see them as whole and good. They are able to build relationships, to be seen as human, and to exist without the weight of what they did pressing down on them. According to Radio Free Asia, even media coverage of my assault was blocked in Vietnam.

And me? I have lost my life entirely. My freedom, my trust, my sense of safety, and every feature of my identity— all stolen. I am left in the endless echo of what was taken from me and what could have been.

People love to warn that a false accusation of sexual assault can destroy a man’s life. The far uglier, far more frequent reality is this: when a victim reports a real assault, the world begins to dismantle their existence piece by piece. It wasn’t the assault that broke me the most—it was everything that came after, sanctioned and applauded by the very people who swore to protect me.

They call it justice; I call it a slow, public execution.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual violence, here’s some resources that you can go to:

Safe to Talk Kōrero mai, ka ora National Sexual Harm Helpline 0800 044 334 Text: 4334

Mauri Ora—Student Health and Counselling For counselling and same-day student counselling +64 4 463 5308

Wellington Rape Crisis (04) 801 8973 support@wellingtonrapecrisis.org.nz

Women’s Refuge 0800 733 843 info@refuge.org.nz

NZPC 04-382 8791

Level 4, 204 Willis St, Te Aro, Wellington 6011

By Phoebe Robertson

CW: Medical Neglect, Graphic Content

There’s a photograph I can’t stop seeing:

A small house in Illinois, 1938. A woman, Catherine Donohue, is propped against pillows, her profile pared down by illness until she seems almost to float. Beside her, her husband sits with the dogged neatness of grief—hands folded, shoulders square. A commissioner, pen in hand, leans forward with the anxious impatience of a guest who knows the furniture was not built for cross-examination. And Catherine, queenly even in a cotton nightgown, gives testimony that does not belong to the room at all. It is meant for posterity.

Her words: It is too late for me, but not for you.