Tariq Allana, Associate Director, Art Heritage

With the graduation ceremony concluded, an artist steps into an uncertain world—no longer a ‘student’ but immediately labelled, willingly or not, a ‘professional artist’. The artist must now confront an art world shaped by market forces and institutional expectations, while simultaneously grappling with the deeper task of building a practice that evolves, innovates, and matures over time.

Many young artists turn to residencies and fellowships as a way to sustain their practice and receive institutional validation, yet navigating these opportunities— particularly for South Asian practitioners— has historically been challenging, with funding, geography, and language often becoming significant barriers. Such platforms offer exposure to new cultures, methodologies, and peer networks; create time for reflection, experimentation, and intellectual exchange; and provide mentorship through sustained

engagement with artists and scholars. Most importantly, they build confidence at a formative stage—allowing emerging practitioners to define an identity and test new directions.

For the mid-career artist, the outcome of a well-placed opportunity is somewhat different: with a developed body of work and multiple series already matured, the need is not initiation but renewal.

A reset gives time to pursue new ideas, undertake deeper research, explore unfamiliar materials and mediums, and confront or extend earlier work – all in the pursuit of avoiding creative stagnation. Institutional support at this later stage enables the artist to take stock of their practice, recalibrate priorities, and move forward with greater clarity and focus. It is not surprising, then, that such moments of support serve as inflection points that can reshape the direction of a practice and deeply influence how an artist’s future

work is both conceived and perceived.

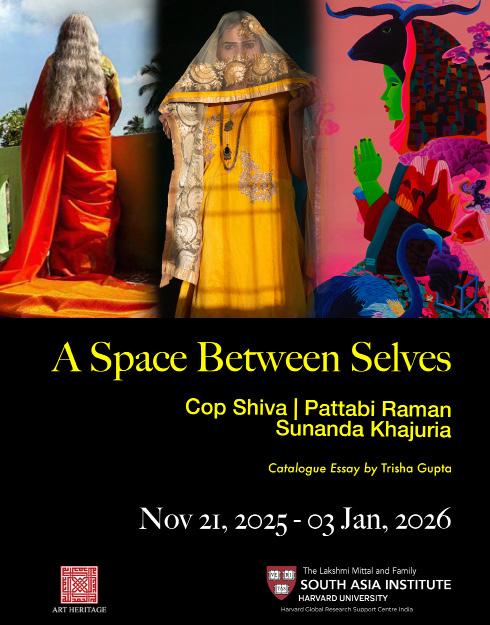

A Space Between Selves brings together works by three mid-career artists— Cop Shiva, Pattabi Raman, and Sunanda Khajuria—all of whom were Fellows of The Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute’s Visiting Artist Fellowship at Harvard University. Cop Shiva’s photographs explore impersonation and masquerade, using photography to examine identity’s fluid boundaries between the ordinary and the performative, the rural and the urban. Pattabi Raman’s lens traces the assertion of identity where myth and reality intersect, revealing transformation as spiritual, existential, as well as exploring identity in the context of erasure. Finally, Sunanda Khajuria’s practice moves across cultures, geographies, and interior states, articulating a visual language that is spiritual, precise, and rooted in journeys of transformation.

The Visiting Artist Fellowship at the Mittal Institute is premised on the idea that artistic practice flourishes through sustained research, cross-cultural dialogue, and engagement with new intellectual environments. This vision aligns with Art Heritage’s longstanding commitment to supporting artists at pivotal moments in their careers and providing a liminal space between experimentation and public engagement. A Space Between Selves stands as both culmination and continuation—a testament to artistic growth nurtured across institutions, geographies, and modes of inquiry.

Trisha Gupta

Why do we make images?

The question may seem vast and openended — and yet, few would dispute that a primary motivation for art is the desire to represent life. To re-present it, if you will.

“Drawings form the basis of humankind’s earliest record of itself,” wrote the art teacher Ron Bowen in his classic drawing manual Drawing Masterclass (1992).

That impetus — to record and represent reality — only grew stronger with the invention of photography. Susan Sontag’s era-defining book On Photography, which won her the National Book Critics’ Circle Award for Criticism in 1977, argued that a photograph was an image like no other. The very nature of the photographic process meant that it wasn’t just an interpretation of reality, it was a trace of it: “something directly stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask.” And yet no record we make, especially of ourselves, is neutral. Every record is also a reshaping.

The art historian and critic John Berger responded to Sontag in a 1978 essay titled Uses of Photography, where he saw a prophetic quality in the naming of the world’s first mass media magazine: Life. Apart from the title’s obvious capaciousness (Berger wrote), reading it alongside the magazine’s very first images — a newborn baby with the caption Life Begins — seemed to suggest not just that the pictures inside were about life, but that they were life.

The first permanent photograph to have survived was taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. Creating View from the Window at Le Gras took Niépce a wooden box camera, a pewter plate coated with naturally occurring bitumen and closely supervised exposure to sunlight — a process that lasted anywhere between eight hours and seven days. Two centuries later, that once laborious process of making a copy of reality has become so effortless and so widely accessible as to begin to deplete our sense of it being a

little bit magic.

And yet, when one thinks of all these things together, it should come as no surprise that image-making remains deeply enmeshed with identity. Derived from the Latin ‘idem’, meaning ‘the same’, the word ‘identity’ means the state of being the same.

That meaning may seem surprising now, especially to anyone born after the mid1990s, since the more common usage of ‘identity’ now suggests precisely the opposite. Claiming an identity is how one describes one’s difference from others: think of ‘identity politics’, a term first used in 1985. The idea of ‘identity theft’, first used in 1995, only makes sense if one’s individual identity is understood as something unique. And yet the idea of identity is about sameness, too. Not to be tautological, but positing one’s difference from something or someone often requires being the same as something or someone else.

The Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute at Harvard University, the three artists in A Space Between Selves are united by a persistent interest in these questions of sameness and difference. While their explorations of identity take different routes – photojournalism, photoperformance and painting — each of their oeuvres raises compelling questions about

the relationship between performance and interiority, collective and individual, self and other.

***

For Pattabi Raman, who spent seventeen-odd years as a photojournalist with the New Indian Express before turning freelance, the identities he documents are straightforwardly those of the communities he seeks out: non-mainstream, marginalised, yet strengthened by collectivity. The series In No Man’s Land, for instance, is a portrait of the Agariyas: 60,000-odd people from the Miyana, Sandhi, Ahir, and Chunvaliya Koli communities who earn a precarious living making salt in the Little Rann of Kutch, a saline desert off the coast of Gujarat. The Agariyas get their name from the large salt pans called ‘Agar’ which they prepare manually, pumping sub-soil brine into them from underground wells, and raking for days until evaporation leaves behind white crystals of salt. Many Agariyas suffer tuberculosis, skin diseases, and blindness from salt exposure. The harshness of their lives is exacerbated by poverty, lack of access to education and healthcare, as well as environmental and legal challenges to their very existence.

Seeking to encourage salt production immediately after independence, the Indian state made licenses unnecessary

“And yet the idea of identity is about sameness, too. Not to be tautological, but positing one’s difference from something or someone often requires being the same as something or someone else.”

- Trisha Gupta

Pattabi Raman, In No Man’s Land - The seasonal migrants of Kutch series, 2008

Hahnemühle Studio Enhanced Matt paper

14.3 x 21.5 inches

for farming salt on less than 10 acres, leaving the history of Agariya labour undocumented — though it contributes nearly 30 per cent of the country’s salt. Policy changes in the last 50 years have made the community’s existence less and less tenable. In 1973, the Little Rann was declared a sanctuary for the endangered Indian wild ass. Nothing further happened until 1997, when the government stopped renewing the traditional leases of Agariya salt workers. (Private companies, sadly

but unsurprisingly, continued to receive approvals.) A decade later, in 2006-07, the forest department issued eviction notices. The Agariyas have since attempted to organise and make a claim to “seasonal community rights” under the Forest Rights Act. But their very identity – and that of their land and their produce — remains a matter of contention. “Agariyas are categorised as a de-notified nomadic tribe but have been living in the Rann for more than 75 years so can qualify as “other

Pattabi Raman, In No Man’s Land - The seasonal migrants of Kutch series, 2009

Hahnemühle Studio Enhanced Matt paper

14.3 x 21.5 inches

traditional forest dwellers” under the Forest Rights Act,” Ravleen Kaur wrote in Scroll in 2021. Does the land with salt pans come under the revenue department or the forest department? Is salt a forest product or a mineral?

Raman’s pictures are spare, judicious, distant enough to look lyrical — and yet his black and white brings out the unrelenting elemental quality of Agariya lives. A severe sun casts long shadows

onto barren expanses of mud desert. The ground is cracked into a thousand pieces. Even water here loses its liquidity to harden into encrustations of salt. The absence of infrastructure or architecture – barring the barest tent made of gunny bags — leaves the human form silhouetted against sky, soil, water. Agariyas are their land.

“I went to Kutch because I watched a very short video in which an [Agariya] woman used a piece of broken mirror to catch

the light and signal to her husband that food was ready,” Raman said in a telephone conversation from Pondicherry, where he lives. “I couldn’t believe people were still communicating like that.”

While Raman may have imagined an ancient, pre-technological identity for the Agariyas, his camera reveals otherwise. We see a girl curve gently, affectionately, towards her bicycle. A boy seems to cradle his transistor radio. A ghaghra-clad woman stands, arms akimbo, atop a loaded tractor. A man and his family of four sit gleefully aboard a twowheeler. In image upon image, they inhabit industrial modernity. It is just that the machines they have access to have been around for a century, or two – long enough to seem, literally, part of the scenery.

Raman’s second photo-series also portrays a group on the margins — not geographically or technologically, but in terms of their gender and sexual identity. The images are of the transgender community of Tamil Nadu, taken over Raman’s multiple visits to Koovagam: a massive festival held annually in April-May, commemorating a Mahabharata story. Aravan, one of Arjuna’s sons, agreed to sacrifice himself to ensure victory for the Pandava army in the battle of Kurukshetra. Before he died, though, he wanted to experience marriage. Since no mortal woman was persuadable, the mangod Krishna transformed himself into a beautiful woman called Mohini and married

Aravan. The day after the marriage was consummated, Aravan sacrificed himself to Kali. A heartbroken Mohini mourned her widowhood before she transformed back to Krishna.

At Koovagam, thousands of transwomen gather to dress up as Mohini, marry Aravan and mourn his heroic death, all in a matter of days. The re-enactment of the myth condenses joy and suffering, fulfilment and deprivation, lust and devotion into a ritual outpouring that is the very embodiment of Emile Durkheim’s ”collective effervescence”. Raman first visited Koovagam in 2006 with a Coolpix camera. He returned in 2008 to shoot his first photo-essay. The current pictures – from trips made in 2014, 2017 and 2022 — reveal a community at ease with itself and yet profoundly self-conscious. While Raman’s images are a document, the creation of images is itself integral to the cementing of an Indian transgender identity. To be photographed is to turn the hidden into the visible, the shameful into the proudly proclaimed. “Earlier, I was one of the only Indian photographers there, and people were shy to say they were visiting Koovagam. There was an element of mockery. It was like going to see an animal in the zoo. People were not seeing the human side. Two decades later, the vibe has transformed,” Raman agreed. “I have

Pattabi Hahnemühle

photographed the Gay Parade in New York and Chennai; the Koovagam dynamic is totally different. They feel blessed to be transgender. If they were born again, they would want to be the same.”

“[My transgender subjects] are not like me. I never feel proud about anything in my body,” Raman laughs. “A transwoman feels

proud that she has breasts. They display the self.” His images depict various phases of the festival – and in every phase, the self is performed. “By staying in a lodge in Viluppuram, I get to know transgenders who also stay there and commute to the temple daily,” he said. “Many portraits are taken in the lodge.” In one striking image, a transwoman pressed up against an

aquarium becomes half-fish herself. Unlike a mermaid, though, the lower half of her body remains human, while her face is replaced by the reflected pink gourami’s. Raman makes shapeshifting magic out of the moment. Sometimes the lodge is the site of more painful forms of shapeshifting – we see one transwoman getting her chin hair tweezed, resting her head on another’s lap, utterly vulnerable and yet necessarily trusting remaking the self together.

The beauty treatments are in preparation for the Miss Koovagam beauty pageant, a modern-day innovation that is itself now 25 years old. In Raman’s pictures, the pageant itself appears all shimmer and glory. Statuesque participants in brilliant silk saris twirl and parade, framed in the light of a hundred screens.

In the next stage of the festivities, thousands of transgenders marry the god Aravan in individual wedding ceremonies conducted by the priests of the Kuttantavar temple. Fascinatingly, in a reversal of the myth, there is no shortage of brides for Aravan here. It is the groom who must be a pretend one. The priests – bare-bodied cis men — stand in for the divine bridegroom, conferring upon each transgender bride all the recognizable identifiers of married Hindu womanhood. We see one priest’s hand reaching out to put a vermilion mark upon one bride’s forehead, and another tying a thali (auspicious thread) around

another bride’s neck. As transwomen watch each other go through a muchawaited ritual, the mood is intense, even sombre. But Raman’s images also capture an openness that one might never find in a socially-sanctioned heterosexual wedding: one bride hands her priest-groom a bundle of cash, while another looks deliberately away from her ‘husband’ in the climactic moment, pouring all her clenched energy into a selfie.

The last phase of the proceedings involves

Aravan’s death, leading to ritual widowhood for all the “Aravanis”, as Tamil transwomen call themselves (instead of the common pan-Indian term hijra). It feels strange to see the ordinary, long-term indignities of widowhood expressed in this dramatic, extraordinary and temporary form. As with the wedding rites, what is most memorable about the widow moment is the crush of bodies, the collective performance of grief, the emotions of one feeding off the other. And yet, these feelings are not fake. They are, as a ritual sensorium always is, deeply

cathartic.

Each transwoman at Koovagam may take great pride in her individual physical appearance and identity, may be deeply invested in the performance and recording of her own rites of passage — and yet that identity derives much of its strength from the collective solidarity of other bodies like hers. Difference, too, needs the strength of sameness.

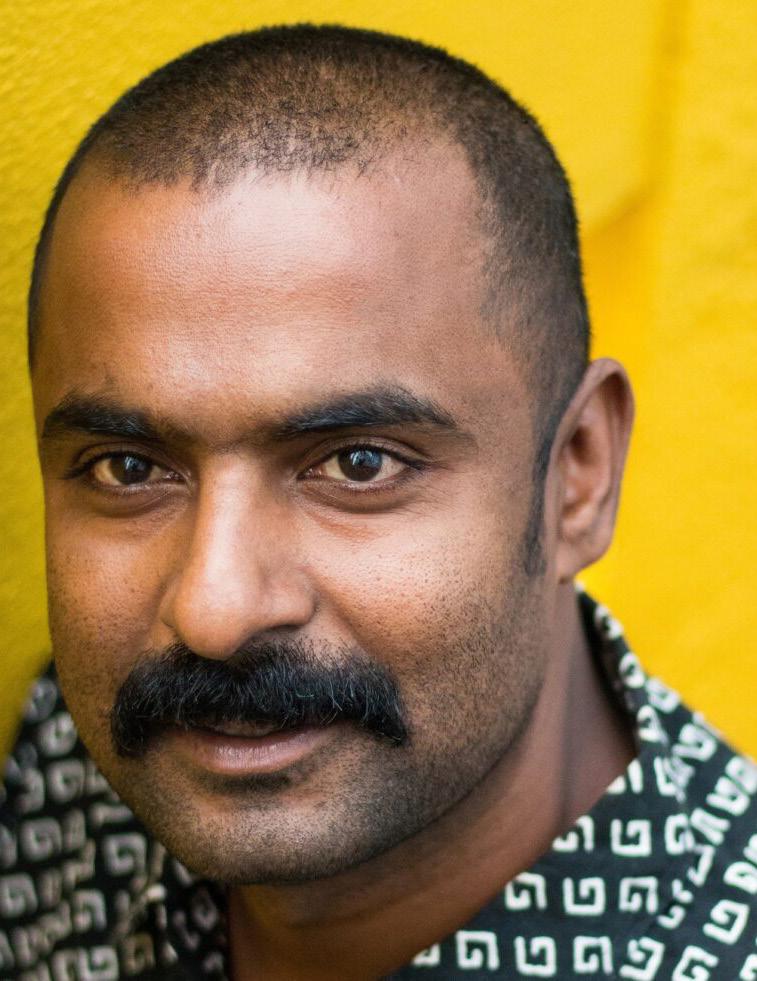

If Pattabi Raman’s images capture what the sociologist Erving Goffman famously called “the performance of the self in everyday life”, photographer Cop Shiva’s work has been a long engagement with performing someone else. The artist’s fascination with masquerade, with the possibility of multiple selves, seems no coincidence once one knows his biography. ‘Cop Shiva’ is the moniker adopted by Shivaraju BS, who grew up in rural Karnataka and worked in the police force for 17 years before his unusual crossover into the creative world. The work on display here is drawn from three different projects, threaded through by Shivaraju’s interest in the relationship between public and private selves, between interiority and performance.

The Being Gandhi images are of Bagadehalli Basavaraj, a schoolteacher from Chikmagalur district in Karnataka.

When the pictures were first exhibited in 2012-13, Basavaraj had been dressing up as Gandhi for 13 years, and Cop Shiva had already been photographing him for two and a half. Basavaraj grew up in a poor family in Kadur, where a small temple to the ‘Father of the Nation’ (built soon after his assassination in 1948) still stands. So it is perhaps not surprising that he was drawn to Gandhi’s principles early. But it was later in life that he started dousing himself in silver paint and walking around nearby villages in his Gandhi get-up: barebodied, with a white dhoti, round-rimmed spectacles and a wooden stick. It was embodiment, not caricature.

Yet when I wrote about that 2013 show (also held at Art Heritage), I singled out the silver paint as creating a Brechtian ‘alienation effect’ within Basavaraj’s performance, always underlining that this was not Gandhi. Not Gandhi who stood in a rural classroom next to a chart depicting the real man, not Gandhi sitting on a bench amidst a crowd of schoolchildren, not Gandhi on a bicycle at the head of a troop of motorcyclists.

Twelve years later, it seems to me that the gap between Basavaraj and Gandhi has lessened – or perhaps the gulf between Gandhi and us has widened? The semiironic quality I once attributed to the images has been replaced, at least in my gaze, by something sadder. What leaps

out at me now are the reactions of the people in the frame with Basavaraj — the bored schoolchildren, the judgemental girls, the laughing burka-clad woman, the glumly suspicious teenaged boy – and the Gandhi-lookalike’s stoic, even sad visage. The real historical Gandhi was almost always grinning in pictures, or at the very least animated. Barring a few instances, one saw him talking and laughing with those around him, touching others and being touched. What Cop Shiva’s pictures reveal to me now is that Basavaraj brought his own feeling of alienation to his Gandhi — being Gandhi allowed him to be a little outside his own time and place. Gandhi is an identity but also an escape, a disguise.

Cop Shiva’s second series, I Love MGR, appears more straightforward than the Gandhi images. Perhaps because Vidyasagar (the subject of the pictures) impersonated the late actor-politican MG Ramachandran in a manner more familiar to us than Basavaraj’s — making a concerted attempt to look exactly like his hero, for instance? Or perhaps these images feel warmer and simpler than Being Gandhi because one doesn’t see members of the public responding to the faux-MGR? What is undoubtedly moving is the impersonator’s home setting, the easy presence of his giggling wife and thoughtful child.

More than Basavaraj, however, Vidyasagar

Cop Shiva, Being Gandhi series, 2012

Hahnemühle Photo Rag Bright White Fine Art paper

35 x 52 inches

depended on the masquerade for his sense of self. Cop Shiva has said in older interviews that Vidyasagar never left home without his MGR look on. In one of the images not on display here, we see that even his wedding photograph has Vidyasagar looking like MGR. Who, then, was the private Vidyasagar? Like many celebrity-lookalikes in India, does the obsessive mimicry of some public persona gradually change the impersonator’s private persona? What is the link between the physical and the emotional self? What is identity, really, but an assemblage of looks and gestures, hairstyles, clothes, a verbal tic or two?

These are questions that animate this show as a whole, and we will return to them when we come to look at Sunanda Khajuria’s paintings. But before that, let us look at the final set of images from Cop Shiva. These are photographs he started taking during the Covid pandemic, when he went back to his childhood home, the village of Ramanagara (part of Indian film lore for being the hilly shooting locale of the 1970s superhit film Sholay). The series features a stocky woman, standing, viewed either from behind or above, in a variety of domestic and rural settings. In each image she wears a bright sari of a different hue, a mass of silver-grey hair descending down her back in soft waves.

It turns out that the muse is his mother. “I was living with my mother after 19 years. She was 62 and I was 39 at the time,” Shivaraju told me in a telephone interview. “She had had a tumour surgery and was recovering. I had built a house for her – the green house [in the pictures]. And every day she would bathe and wear a fresh sari… I wanted to capture this passion. So I started taking pictures, seeing my mom like an artistic sculpture.”

And yet, he was appalled when an upscale fashion magazine wanted to facilitate a ‘collaboration’ between his mother and a designer sari label. For him, his mother’s passion for brightly coloured saris is personal, historical, non-monetisable. “She has a collection of some 450 saris now! But when I was young, we were not well off, she would have two saris, one to wear and one to wash. For a special occasion, she would borrow,” he recalls. Cop’s desire to imbue this work with his mother’s identity is simple, yet effective. “I placed her in the places she belongs to – the rocks, the house, the land, her favourite temple, her friend’s house,” he said. Later, he named the series My Mother and Her Many Technicoloured Sarees.

If one keeps this biographical context aside for a moment, what is most striking about the images is twofold: first, that the woman is not young, and second, that her face remains hidden. The hiding is not

coquettish, unlike many a reluctant muse. No hand, veil or sari pallu is held up as a defense against photographic capture: the woman simply faces away from the camera, and even her body does not perform for it. (It is disturbing to realise how rare this has become — a set of images that does not make a seductive appeal to the viewer. What was once limited to advertising’s visual aesthetic is, in the Instagram age, the norm for all images — even those we create ourselves.)

But Cop is too self-reflexive to pretend that the subject is unaware of the camera. His mother’s folded arms and the arrangement of her saris suggest deliberate staging, not candid shots. But all we are allowed to see is her back and head, and a sari often trailing away from her. There is something uncanny about the images; after all, the ghostly figure in a sari is a fixture of the Indian imagination. But isn’t that because the sari-clad woman with her hair open to the sun is also a fixture in all our memories?

With this series, Cop Shiva moves away from a search for individuality in the lookalike to exploring the universality in a very particular person. In a sea of people striving to look different, the power of these images lies in the fact that she could be anyone.1

Sunanda Khajuria’s art also opens up questions of identity. In fact, Khajuria’s career reveals an ongoing engagement with that subject on at least three different planes.

On the first plane is Khajuria’s (perhaps unconscious) resistance to a pre-existing collective identity. An India-born artist who has adopted a great deal from Chinese painting traditions, her style challenges any simple mapping of artistic identity onto geographical or cultural origins. Raised in Jammu, Khajuria received her Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from the Institute of Music and Fine Art there before getting an MFA from the Delhi College of Art. It was a 2011 art residency in China, though, that changed the course of Khajuria’s career. “Immediately captivated” by Chinese landscape painting, she went on to spend three years studying Chinese traditional ink art and language in Hangzhou, and over a decade “immersed in China”. Having recently completed her PhD from Wuhan Technical University, Khajuria remains inspired by the “philosophical depth and layered symbolism” of Chinese aesthetics. “I see my work less as belonging to a single national tradition, more as a dialogue between civilizations,” she told me in an interview.

The second (more conscious) plane is a corollary to the first: Khajuria’s strong sense of her art as an expression of individuality. She calls her work “deeply autobiographical” – i.e. drawing on her experiences, while also conceiving of all “art as a form of self-discovery” – i.e. drawing on her imagination. “As I create, I uncover layers of my own identity and emotions that may not be immediately apparent,” she explained. “In that sense, my work exists at the intersection of autobiography and introspective exploration.”

Being born into a particular place and time once meant that an artist would train in the linguistic, aesthetic and philosophic traditions of that particular civilisation. In the modern era, the artist came to view that sort of deeply embedded training as a constraint on individual self-expression — not as equipping them with an understanding of the collective with which they must speak.

By this measure, Khajuria’s subjectivity is unabashedly postmodern: claiming the idea of tradition, while in practice picking and choosing from it whatever elements she likes. “I view tradition not as a static artifact to be preserved, but as a living, breathing river… My Indian heritage provides the foundational grammar of

1It should come as no surprise that in 2019, Cop Shiva paid tribute to Vidyasagar (who had died in 2015) by photographing himself made up as MGR, nor that his most recent solo show, ‘No Longer a Memory’ (held at Bangalore’s Gallery Sumukha in May-June 2025) was a photo-performance series, with the artist and his mother Gowramma staging all manner of playful double acts, from wrestlers to porters, cops, even gods.

my expression—its narratives, spiritual inquiries, and vibrant sensibilities,” she told me. “China has infused this grammar with a new vocabulary of restraint, harmony and the poetry of emptiness. In this crosscultural space, I explore universal human conditions—migration, displacement, the quest for equality.”

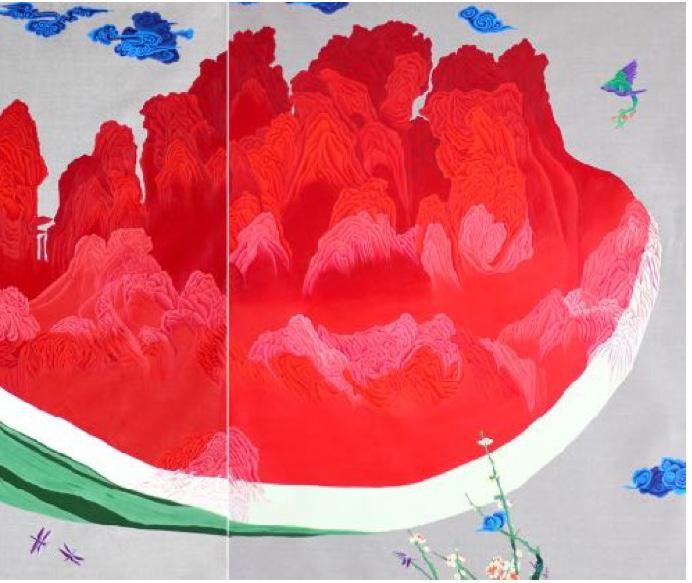

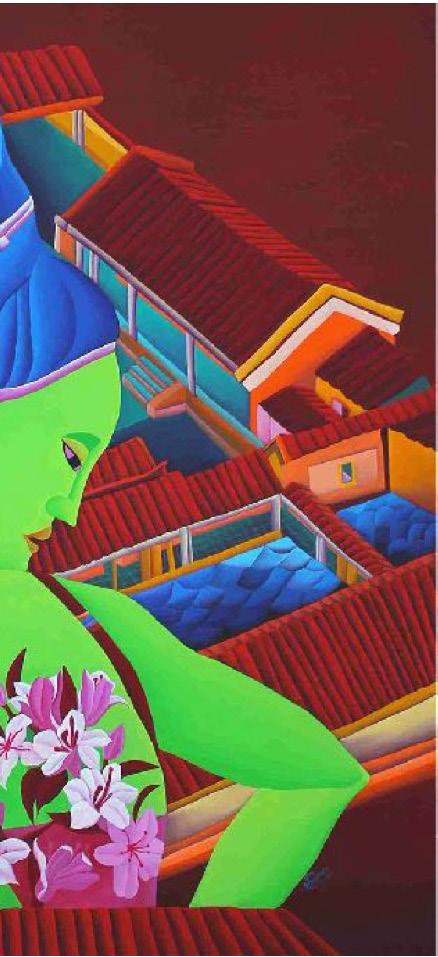

The mood feels meditative or melancholy, but there is nothing raw or emotional here. All surfaces have a polished sheen, and an almost eerie serenity. Formally, Khajuria seems to enjoy playing with negative space, scale and composite forms. The Chinese silk scroll paintings have a gauzy, translucent quality, the plain silk material of the background either unpainted or visible through the bodies of most humans and most fauna. In contrast, the acrylic paintings are characterised by large, flat areas of jewel-like colour. Khajuria attributes her compositional choices to the specific principle of ‘balanced emptiness’,a core tenet of Chinese art and literary theory. “I learned that the void is not a lack, but an active element,” she explained. “The empty spaces in a Chinese landscape are what give the solid forms their weight and meaning. This has fundamentally changed my approach, allowing me to blend intricate detail with powerful, unspoken narrative, where what is left unsaid resonates most deeply.”

The third plane on which Khajuria

addresses the identity question is imagery, starting with the female figure or face that is so often her narrative centre, usually in a luminous green. “The female form is my primary vessel because it embodies the universal principles of creation, resilience, and spiritual depth. While it began as a mode of self-expression, it has evolved into a symbolic representation of consciousness itself,” Khajuria clarified. “The pervasive use of green serves as a visual language for growth, harmony, and the life force that connects all beings.”

Symbolic motifs are aplenty, often partaking of the scale-play I mentioned earlier. So a shoe becomes a boat in which a human figure is adrift, while a boat elsewhere is held aloft by a pair of small birds. Birds –cranes, blue jackdaws, a kingfisher, even a peacock – are everywhere, as are the tiny stylised clouds traditionally seen on embroidered Chinese jackets (at least two paintings here incorporate the jacket itself).

Even beyond these ubiquitous birds and boats and shoes, Khajuria’s work is strewn with suggestions of travel. But more than migration (which one associates with groups) or displacement (which would be involuntary), the protagonist expresses an individual desire for travel. In Stars and the Soul (2021), for instance, a female figure sits inside a suitcase, her face masked, her green hands raised theatrically above her

“Identity as a theme has no dearth of contradictions.

So Raman’s work draws power from his subjects being outliers, but also from their sense of themselves as a community. Shiva’s images are a search for identities hidden under frontally presented ones; the iconic and the staged somehow still leaves room for secret selves. Khajuria’s deep immersion in a civilisational philosophical aesthetic results in a playful, expressive style.

In every image, an identity is not just recorded but performed. Yet every performance makes them a little more themselves.”

- Trisha Gupta

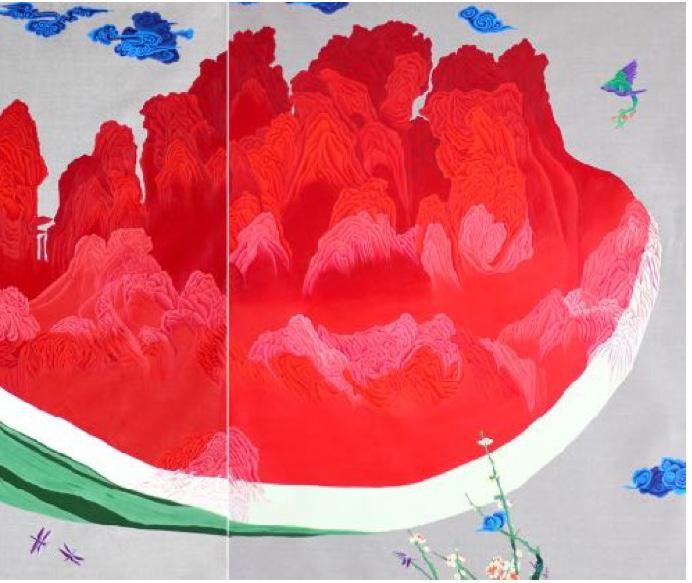

head while a bicycle nestles next to her. In Between Earth and Sky (2023), a woman and a small blue monkey look out towards what is somehow simultaneously a huge slice of watermelon and a boat containing a crimson red skyline.

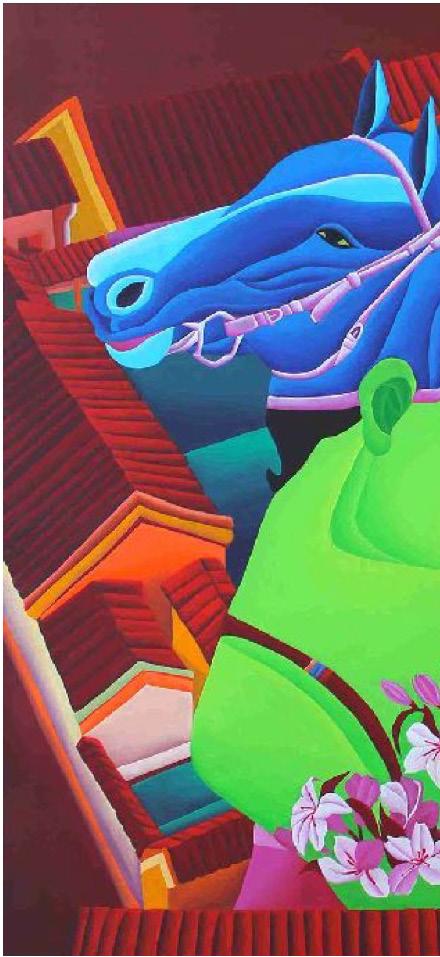

While giving the human face and body primacy, Khajuria specialises in amalgamations that could well represent “the life force that connects all being”. Heads become bodies, humans become animals, inanimate objects seem animate, and faces merge with masks… The topknot on a woman’s head is also a brilliant blue horse (Longings for Home, 2015); the jacket and ice-blue stole draped around another woman’s shoulders contains hills, houses and a whole herd of mountain goats (Frozen Day, 2015).

“By integrating motifs from Indian and Chinese traditions into composite figures, I seek to dissolve the boundaries between the human, the natural, and the cultural,” Khajuria told me. “This [lets me] explore identity not as a fixed state, but as a fluid, interconnected ecosystem.”

It makes sense, then, that the facial features and headgear of Khajuria’s human figures look South Asian or African, while the masks are taken from the Peking Opera

tradition. The traditional Chinese wooden shoe appears often as a motif, but never on the feet of the woman in the painting – she wears sneakers, or ballet pumps. She is the cosmopolitan subject, choosing aspects of different traditions. If identity is now just an assemblage of features and gestures, costumes and vocal patterns, then of course we can each select our own.

I began this essay with a dual idea: that to create an image is a way of recording reality, but to record something is always also to rework it – and ourselves.

Put another way: the artist’s identity, and their reasons for creating an image, necessarily shapes the image they create. But conversely, those images also recreate the identities of those depicted in them – and the artist’s own identity as well. This is as true of the ‘documentary’ photography of Pattabi Raman (who never appears in his own pictures) as of the ‘performative’ photography of Cop Shiva (who increasingly does). And it is certainly true of Sunanda Khajuria, each of whose paintings both is and is not a self-portrait.

Identity as a theme has no dearth of contradictions. So Raman’s work draws

power from his subjects being outliers, but also from their sense of themselves as a community. Shiva’s images are a search for identities hidden under frontally presented ones; the iconic and the staged somehow still leaves room for secret selves. Khajuria’s deep immersion in a civilisational philosophical aesthetic results in a playful, expressive style.

In every image, an identity is not just recorded but performed. Yet every performance makes them a little more themselves.

Trisha Gupta is a film, art and literary critic with experience in journalism, academia and translation. Her published writing for the media (since 2007) can be read at http://www.trishagupta.blogspot.in. She has an M.Phil in cultural anthropology from Columbia University and taught writing at OP Jindal Global University until 2024. She has translated the poetry of Kedarnath Singh and received a PEN x SALT grant to translate Krishna Sobti’s Delhi memoirs (both from Hindi to English). She lives in Delhi and is working on her first nonfiction book.

@chhotahazri (X and Instagram)

Sunanda Khajuria’s (b. 1979, Jammu) practice explores transformation and identity between cultures, places, and states of mind. Her residencies and doctoral research in China deeply influenced her, introducing her to Taoist thought and Chinese ink traditions. Merging Indian and Chinese aesthetics, she developed a visual language that is simultaneously spiritual, precise, and conceptually grounded in the idea of transformation.

Sunanda Khajuria holds an MFA degree from the College of Art, New Delhi (2005), and a Ph.D. in Fine Arts from Wuhan University of Technology, China (2024). She has received numerous honours, including the Second National Award by the Chinese Government (2024), the Princess Sirivannavari Fellowship (Thailand, 2020), and the Suzhou Art Award (2017). In 2020–2021, she was a Visiting Artist Fellow at Harvard University’s Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute. Her work has been widely exhibited with solo exhibitions including I Have Lost Me: Birds of Passage (2022) and Moving Landscapes (2016), Art Heritage, New Delhi; and group shows at the International Triennial of Graphic Art Bitola, Macedonia (2025), ASEAN Culture and Art Creation Season-6, Xiamen, China (2025), Geumgang Nature Art Biennale, South Korea (2025) and the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (2023). Her work has also been featured in Art & Deal magazine (cover and interview, 2022) and Harper’s Bazaar India Art Issue (2022).

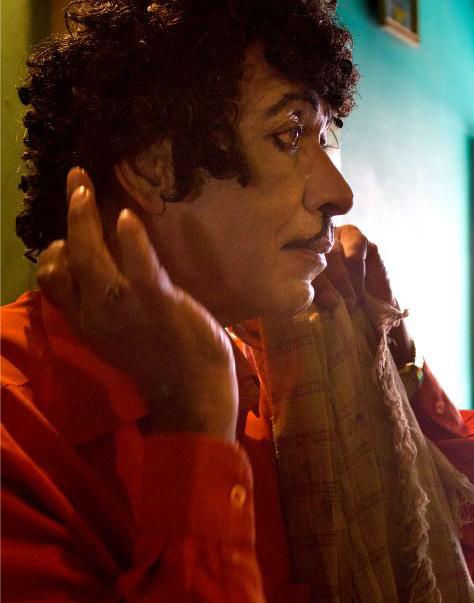

Pattabi Raman

14.3

Pattabi Raman (b. 1977, Pondicherry) is a documentary photographer. His photoessays address socio-economic, cultural and environmental issues, including documentation of the impact of the Sri Lankan Civil War on the lives of the affected Tamils, the aesthetics of India’s rampant multiplex revolution amidst globalization and the documentation of educational opportunitites for children with special needs.

Pattabi Raman holds a B.Sc. in Zoology from Pondicherry University (1998), an M.Sc. in Biochemistry from the University of Madras (2000), and studied at the Tisch School of the Arts, New York (2013). His work has been exhibited at the Kolkata International Photography Festival, Kolkata (2019) and the National Media Centre, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, New Delhi (2016). He has received numerous fellowships, including the Visiting Artist Fellowship, South Asia Institute, Harvard University (2020–21), the Magnum Foundation Human Rights Fellowship, New York (2013), and the Climate Change Media Fellowship, WWF-India (2017). Raman’s accolades include the National Award from the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India (2016), and the Appan Menon Memorial Award (2012), among others.

At the core of Cop Shiva’s (b. 1979, Karnataka) practice lies the idea of impersonation and masquerade—the adoption of ‘another’ as a means of reflection and aspiration. His photography explores the complexity of identity, moving fluidly between the rural and the urban, the ordinary and the performative. A former policeman turned artist, Shiva directs his eye toward those who thrive as they transition and transform, embodying multiple personas—real or imagined—in distinct or concurrent states.

Cop Shiva is a self-taught artist. His solo at Art Heritage, My Life is My Message, was in 2013; more recent solos include No Longer a Memory, Gallery Sumukha, Bangalore (2025); The Street as Studio, The Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute Gallery, Harvard University, USA (2023); Urban Ecstasy, Konstepidemin Gallery, Gothenburg, Sweden (2019); and Being Gandhi: The Art and Politics of Seeing, Duke University, USA (2017). Group exhibitions include For the Love of, INKO Art Center, Chennai (2025); The Month of Photography Tokyo, Japan (2024); Poetics & Relation, Under the Mango Tree Gallery, Berlin (2024); and Illuminations, Art Heritage, New Delhi (2021). He has participated in major art fairs such as Art Mumbai (2025), NADA Miami (2023), and India Art Fair (2022) with Art Heritage, New Delhi. His fellowships include the Iapsis–Swedish Art Grant (2017), Pro Helvetia Swiss Art Council Award (2018), and the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute Fellowship, Harvard University (2023)

Located in the iconic Joseph Allen Stein–designed Triveni Kala Sangam in New Delhi, Art Heritage is dedicated to advancing modern and contemporary Indian art. We seek to foster both the appreciation and acquisition of art, creating a deeper engagement between artists and audiences.

Over nearly five decades, Art Heritage has presented more than 650 exhibitions and 450 catalogues, celebrating the work of distinguished masters and emerging voices from India and abroad. Our exhibitions often showcase less frequently represented medium within the Indian gallery ecosystem, such as printmaking, ceramics, and photography. Essential to our programming are educationally focused public talks, webinars, scholarly essay and curated walkthroughs that encourage accessibility and dialogue.

Through our initiatives, we support furthering artistic discourse essential to a vibrant and evolving democracy.

The Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute at Harvard University (the Mittal Institute) connects Harvard and South Asia. The Institute works with faculty members, students, and in-region institutions and experts to advance and deepen the understanding of critical issues shaping South Asia and its global impact.

It facilitates scholarly exchanges among Harvard faculty, students, international specialists, and visiting academics, sponsoring lectures and conferences across Harvard and South Asia by distinguished academic, governmental, and business leaders whose work contributes to a better understanding of the region’s challenges. The Institute also supports student engagement through grants for language study, research, internships, and student organizations.

Formally recognized as an academic institute in 2013, the Mittal Institute now serves as Harvard’s premier center for regional studies, cross-disciplinary research, and innovative programming on South Asia. Working with Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and their diaspora populations, it is building a vibrant community of scholars and practitioners advancing South Asian studies.

Through grants and fellowships, the Institute supports faculty and scholars in advancing research that builds intellectual bridges between Harvard and the region. Extending this commitment to creative exchange, the Mittal Institute’s Arts Program connects South Asia’s vibrant artistic world with Harvard’s intellectual and cultural ecosystem through dedicated fellowships, research initiatives, and public events.

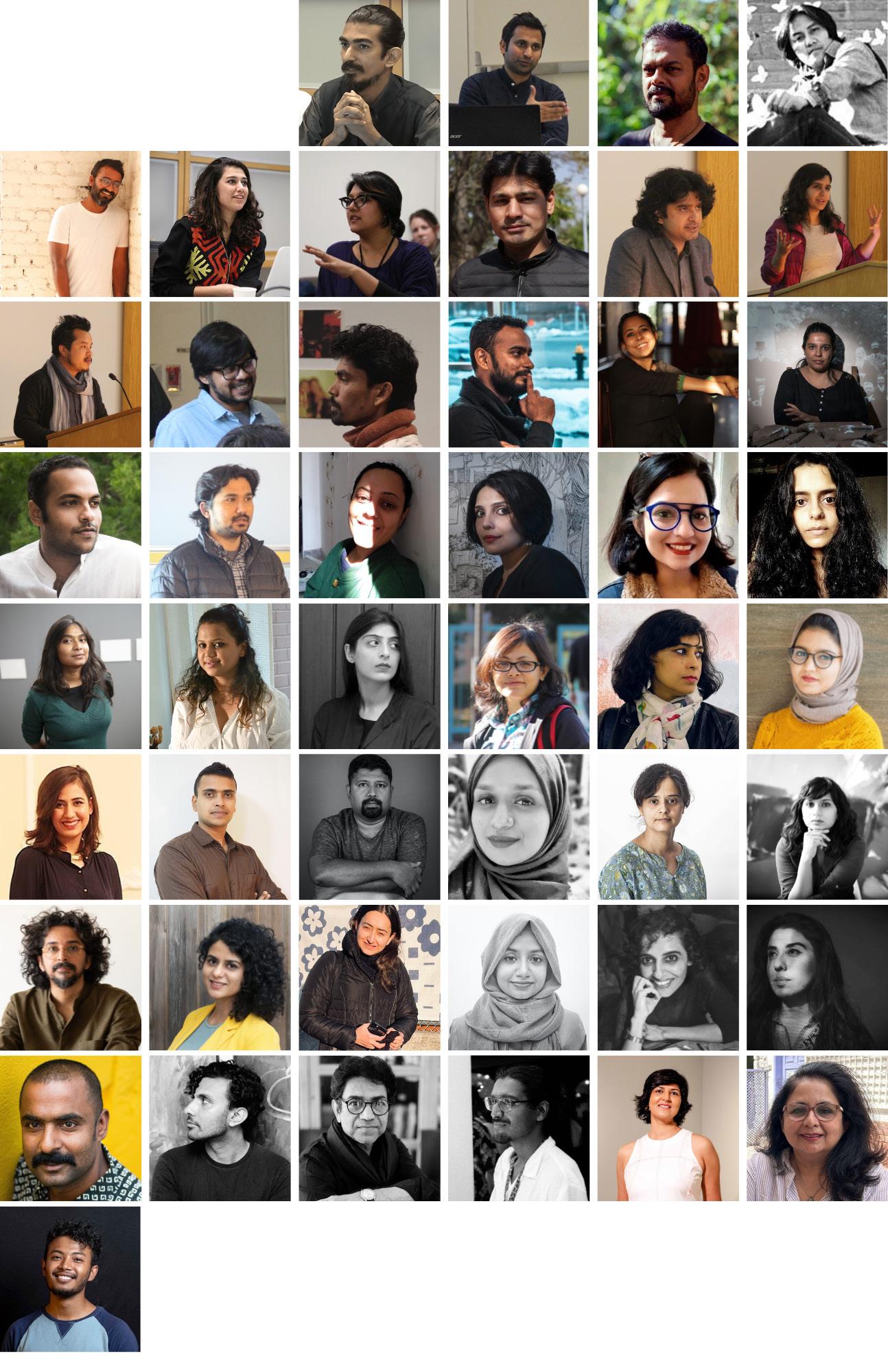

The Mittal Institute’s Arts Program annually offers the Visiting Artist Fellowship (VAF) to four mid-career artists from across South Asia through a competitive process and invites them to Harvard’s campus for eight weeks.

The VAF differs from a typical artist residency program in that it is research-centered, providing artists with the vast resources of Harvard’s intellectual community to enhance their artistic practice. The VAFs spend their time on campus researching a topic of their choice, guided by a Harvard faculty mentor, as well as presenting a solo show of past work at the Institute. They receive access to Harvard’s physical and digital libraries and archives, Harvard and local museums, and a diversity of classes, events, talks and lectures.

The experience aims to help South Asian artists deepen their work and the themes they explore, while exchanging ideas with the university community. The Mittal Institute also works with the fellows to amplify their work in different ways, including with presentations, an exhibit, and through featured profiles on Mittal Institute’s website and newsletter.

For ten years, the Mittal Institute’s Visiting Artist Fellowship has brought visionary artists from across South Asia to Harvard University, creating a rare space where artistic practice meets academic inquiry. Since its inception, the program has hosted over two dozen fellows from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and beyond, each using their eight weeks on campus to research, reflect, and expand the boundaries of their work. As the Mittal Institute marks this milestone, we celebrate a decade of creative dialogue, cross-disciplinary learning, and the enduring impact these artists have made within Harvard and throughout the global South Asian arts community.

Visiting Artist Fellows 2015 - 2025

We are indebted to all who have been involved in making the exhibition A Space Between Selves possible.

Art Heritage

Alekh Nayak, Sangeeta Singh, Shankar Nagesia, Shubha Paliwal

Mittal Institute

Monika Setia, Shreya Majumdar, Angarika Datta, Sushma Mehta, Amit Chaudhary, Carlin Carr

Wall Text Patel Brothers

Construction Pappu, Yadav