A History of Excellence

A History of Excellence

By James Zug

Copyright: 2019 © The Haverford School

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of The Haverford School.

ISBN: 978-0-578-57324-3 The Haverford School 450 Lancaster Avenue Haverford, PA 19041

Cover and book design by Veronica Utz, Veronica Utz Graphic Design

PREFACE 1

PROLOGUE 2

CHAPTER ONE

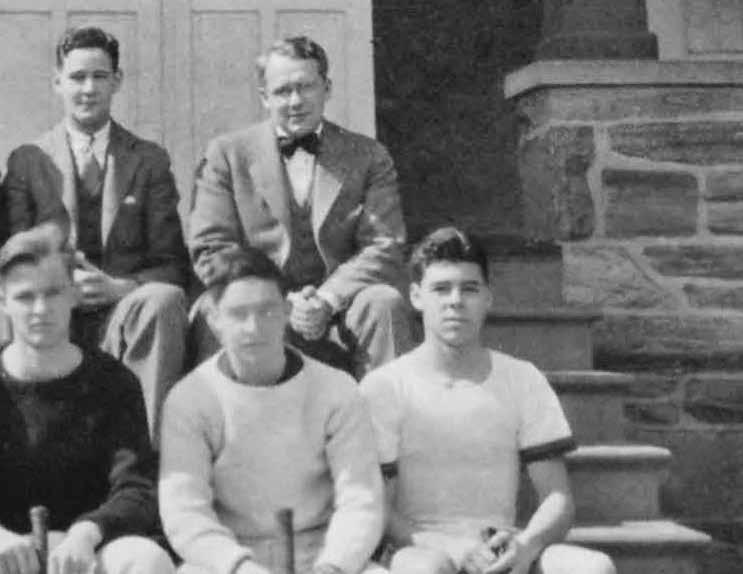

Quickens the Eye and Faster of Foot | 1912-1938 4

CHAPTER TWO

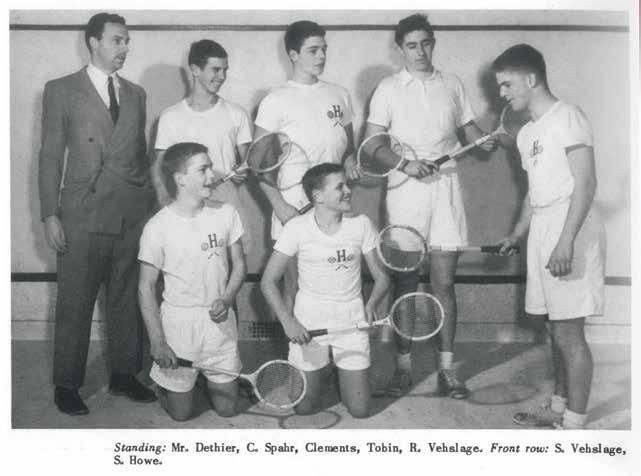

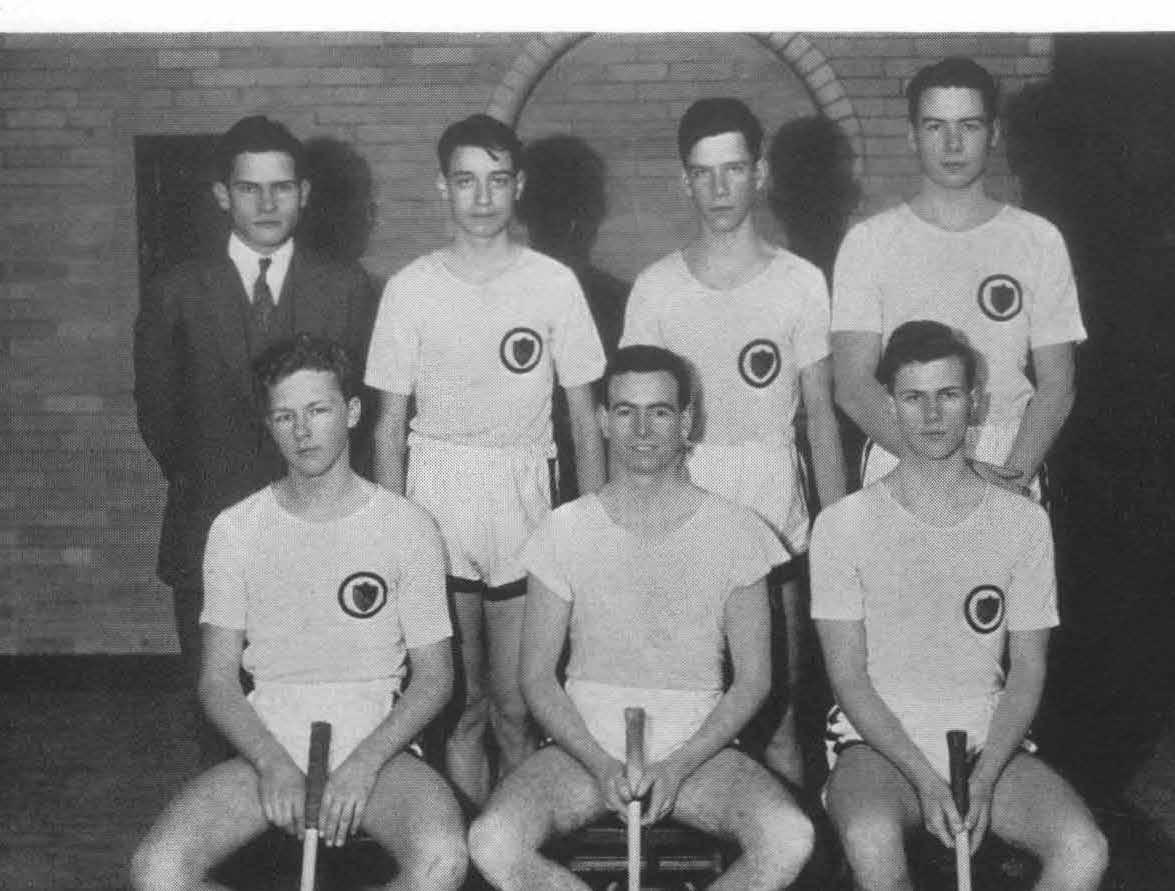

Dethier is Under the Table | 1938-1965 14

CHAPTER THREE

Strength of Character | 1965-1978 30

CHAPTER FOUR

The Khans of Haverford | 1978-1989 46

CHAPTER FIVE A Flash Pace | 1989-2009 66

CHAPTER SIX

Nationals Meant Everything | 2009-2016 76

CHAPTER SEVEN

National Champions | 2016-2019 92

APPENDIX 103

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 178

SPECIAL SECTIONS

ALUMNI | Indefatigable Play 24

EPISCOPAL | Leave the Van Running 40

CHOATE | Lombardi 60

TOC | Volley Figure Eight 86

Preface

“Haverford Squash has a rich and deep tradition that is rooted in great character and great characters. It is about as unique as they come. It is incomparable.”

— Bo Dixon ’61, headmaster 1987-1992

“I always looked at Haverford Squash as quality. The alumni and the students were always outstanding. Never at any time during my tenure was I anything but absolutely proud of everyone in the program. The strength of the squash alumni was a sustaining part of the school. The program was a significant part of Haverford’s culture. All the values. You knew where you stood.”

— Joe Cox, headmaster 1998-2013

“The Haverford School has established an extraordinary record of success in squash that places us without a doubt among the very best programs in the country. It was a Haverford School family that created the Justi Cup to honor the best squash team in America every year, and one of the proudest moments of my headmastership came in 2017 when the boys won the Justi Cup for the first time. I look forward to seeing the Justi Cup return home many times in the years to come as Fords Squash continues to build its national reputation for sportsmanship and success.”

— John Nagl, headmaster 2013-present

Prologue

Like the ancient elements of earth, air, fire and water, there are four essentials of Haverford squash.

Earth is the facilities. There were the original three 1931 courts in Ryan Gymnasium and then the unloved late arrival, the fourth court: paneled, dusty, slightly smaller. The courts had metal beams running across the top that sucked up errant balls; lobbing was a dangerous art. The floor was rough, sandpapery. It was hot. The courts, situated over the swimming pool and next to the wrestling room, were thick with heat and humidity. Sometimes the walls would sweat with moisture. It was claustrophobic—a narrow gallery above the enclosed space but no natural light except the large oval window at the top of court two facing Lancaster Avenue. The doors into the courts had a tiny, square plastic window. To signal a change of players, you had to rap the door hard with your racquet: tap, tap, tap, a voiceless password to enter the court.

The courts were a beloved home, nonetheless, redolent with memories. The niveous walls, the floor, the dusty door, the fire-red lines, the smear of scuffed ball marks along the side walls—squash’s fingerprints. The old ladder board stood near the gallery stairs. The white tags, ringed with metal, numbered one to thirty. Each boy’s tag rose and fell according to the results of challenge matches. The ladder was a manual barometer of everyone’s standing on the team.

Then the new 2000 gym. It has the same number of courts (the smallest number among almost every program Haverford faces). They were gorgeous: light and airy, high-ceilinged, glass-backed walls, a two-tiered gallery. It was where the boys drilled, practiced, hit, played challenge matches, faced other schools. It was where the boys became men.

Air is excellence. It is the unparalleled, superlative record. No program at Haverford can match squash’s curriculum vitae: the national reputation, the titles, the incredible post-Haverford performances. The squash teams have captured forty-nine Inter-Ac titles, by far the most for any athletic program at Haverford (for comparison, wrestling has thirty-six, soccer thirty-one, football twenty-six and lacrosse nineteen). Haverford has the best high school squash program in the world. It has won more titles in the Inter Academic League—the world’s toughest high school squash league—than any another school. It has completed a dozen undefeated seasons. It has produced many individual national champions in high school, college and adult play in both singles and doubles; players who led their collegiate teams to national titles; a few have become U.S. Squash Hall of Famers. Leadership is central to the program. Haverford has produced more collegiate men’s squash team captains than any other school in the country.

Each year, having beat all the best high school teams in the Mid-Atlantic and New England, Haverford claimed the mantle of unofficial national champion. But it would only count once there was an official competition. The National High School (founded in 2004 by a Haverford family) and the National Middle School (founded in 2008) championships finally created a method to declare who actually is the best. Haverford has won both tournaments, the only Inter-Ac team to do so.

Fire is the competition. The matches against league rivals, against New England prep schools, against collegiate sides. The agonizing losses, the nail-biting escapes, the easy trouncings. There is nothing a teenage boy will take more seriously than playing for his school. The crucible of matches: name against name up on the white board, mano-a-mano, a gladiatorial sport, the small serried ranks of numbers going sideways until the end. Always win the last point.

Water is squash itself. It flows through every part of the story. The boys are playing a game, a simple sport that consists of a ball, a bat and four walls. Teenage boys invented the game in the 1850s at a high school

outside London and ever since schoolboys have loved it. A passion for squash flows through everything, from the boys who hit their first-ever ball on the Haverford courts at the suggestion of a coach to those seniors who graduate having hit tens of thousands of balls on the court.

In medieval times, people believed there was a fifth element, a quinta essentia or quintessence. Popular among alchemists, quintessence was thought to be a celestial medium that formed the stars and planets, a heavenly element. The quintessence of Haverford squash is friendship.

In 1947 the Haligoluk reported on the team: “This year’s success was very much due to the exceptionally fine bunch of fellows on the team.” It could say that every year. The friendships with the coaches, who always are more mentors than simply on-court technicians. It is the conversations on the dark early evening rides home in the vans, battling traffic coming back to the Main Line, the old train trips to New Haven, the overnight stays at Choate or at the nationals. The quintessence is a deep, enduring fraternal love based on sharing the air, earth, fire and water of Haverford squash.

Quickens the Eye and Faster of Foot

1912-1938

The February 1913 issue of the Index, the Haverford School student newspaper, contained a first-hand report of the sinking of RMS Titanic by Jack Thayer 1912. His father died in the tragedy; Jack and his mother survived. Jack was one of just forty or so people who jumped from the ship and lived—once in the water, he clambered on top of an overturned lifeboat. Five years later he married Lois Cassatt, the granddaughter of the founder of The Haverford School, Alexander Cassatt.

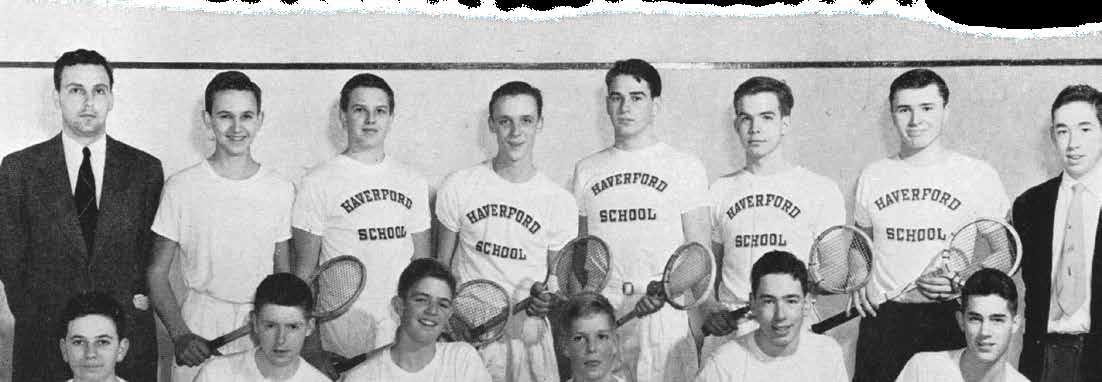

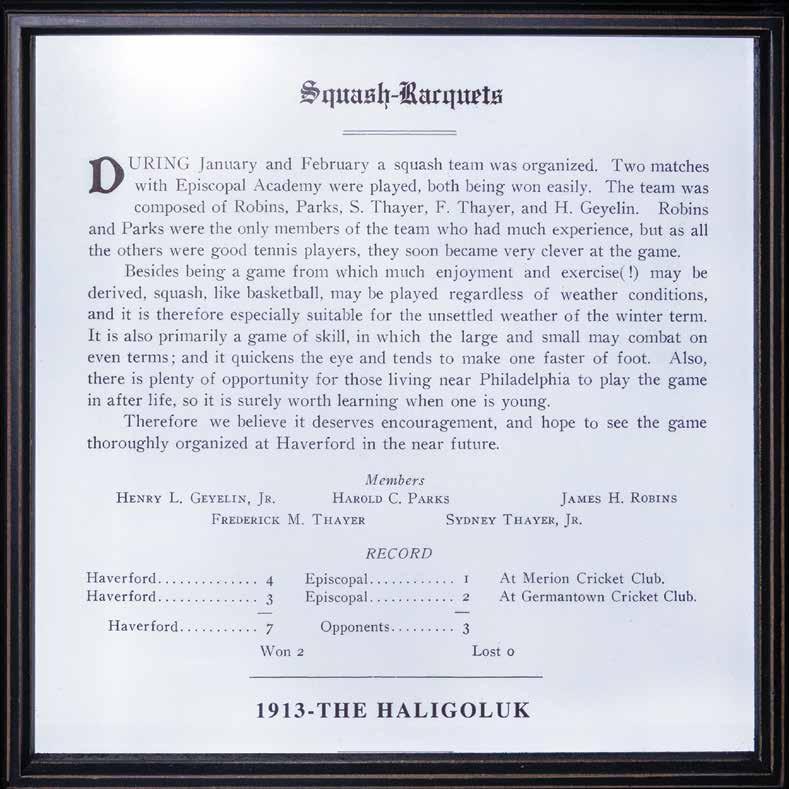

A bit less newsworthy in that issue was a short article that mentioned a squash match that was held at Merion Cricket Club. It was against Episcopal Academy and resulted in a 4-1 victory for Haverford. In February, Germantown Cricket Club hosted a second match against EA, and again Haverford triumphed, 3-2.

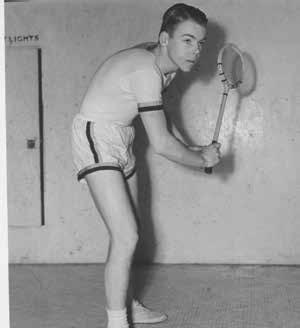

The June issue of the Index dilated on the squash team’s origins. Five students started the team. “Kink” Robins 1913 and “Pawks” Parks 1913 “were the only members of the team who had much experience, but as all the others were good tennis players, they soon became very clever at the game.” Joining Kink and Pawks were Henry Geyelin 1914, Sydney Thayer 1914 and Teddy Thayer 1912 (the younger brother of Jack Thayer).

The Index explained why squash had a bright future at Haverford: “Besides being a game from which much enjoyment and exercise may be derived, squash, like basketball, may be played regardless of weather conditions, and it is therefore especially suitable for the unsettled weather of the winter term. It is also primarily a game of skill, in which the large and small may combat on even terms; and it quickens the eye and tends to make one faster of foot. Also, there is plenty of opportunity for those living near Philadelphia to play the game in after life, so it is surely worth learning when one is young. Therefore we believe it deserves encouragement, and hope to see the game thoroughly organized at Haverford in the near future.” Despite the litany of advantages inherent in the sport of squash, it didn’t take hold at Haverford and sixteen years went by before the game re-emerged on Lancaster Avenue.

In the winter of 1929-30, a gaggle of boys again launched a team. Matthew Baird assisted, but it was, like in 1913, a student-driven initiative. The leaders were the Sargent brothers, Win ’29 and Tanny ’32. Both were active at Merion, and Tanny was one of the highest ranked players in Philadelphia. The team’s first match was at Princeton against their junior varsity. They lost 4-2, but it was considered a good result, according to the Index: “This was a remarkable showing for a schoolboy team, since there are 700 men playing squash at Princeton right now.”

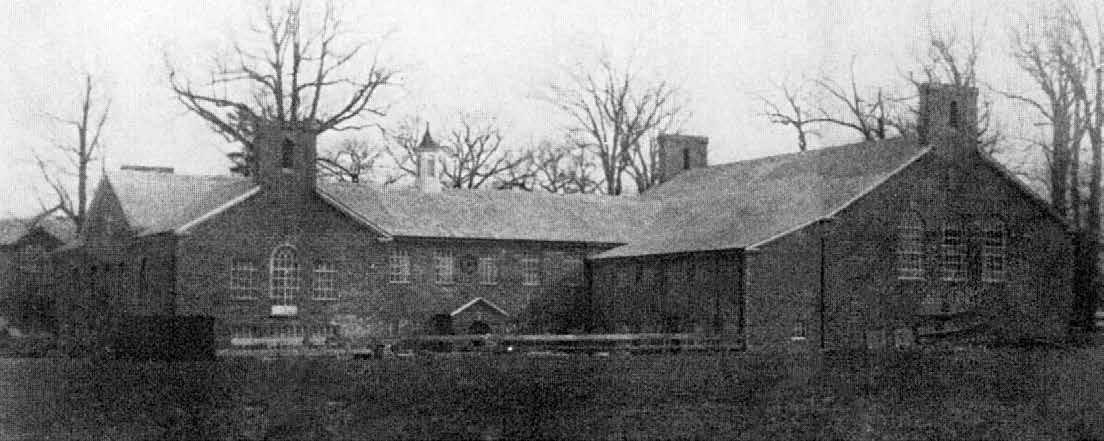

Why did squash reappear in 1930? Squash courts were coming to the campus. In 1902 when the school moved across the street from Haverford College’s campus to the estate of Samuel Austin, it turned a carriage house and stables into a rudimentary gym. It was not pleasant. The sidelines of the basketball court were right up against the wooden walls of a cricket shed. Bleachers were only at the ends, under the baskets, and spectators were protected by wire screens that ringed the end lines. “It was not a lot of fun playing in the old cage,” said Jim Burdick ’39. The side wall was six inches from the out-ofbounds line, and the heavy steel mesh, which extended from the floor to ceiling, wasn’t really that enjoyable to crash into.” An observer in the

1920s described the Austin carriage house as “a veritable fire trap. The floors are not unsafe, but they vibrate and sway when athletics are in progress. The lighting and ventilation are poor. The locker rooms and shower accommodations were inadequate when the School was smaller, but are woefully inadequate now. The basketball court is so small that there is no room for spectators at the sides of the court, and the accommodations at the ends are so limited that only a small proportion of our boys can watch the games, and it is necessary to phone the headmasters of competing schools, warning them of the limited space for their adherents.” There was never a question of adding squash courts to such a situation.

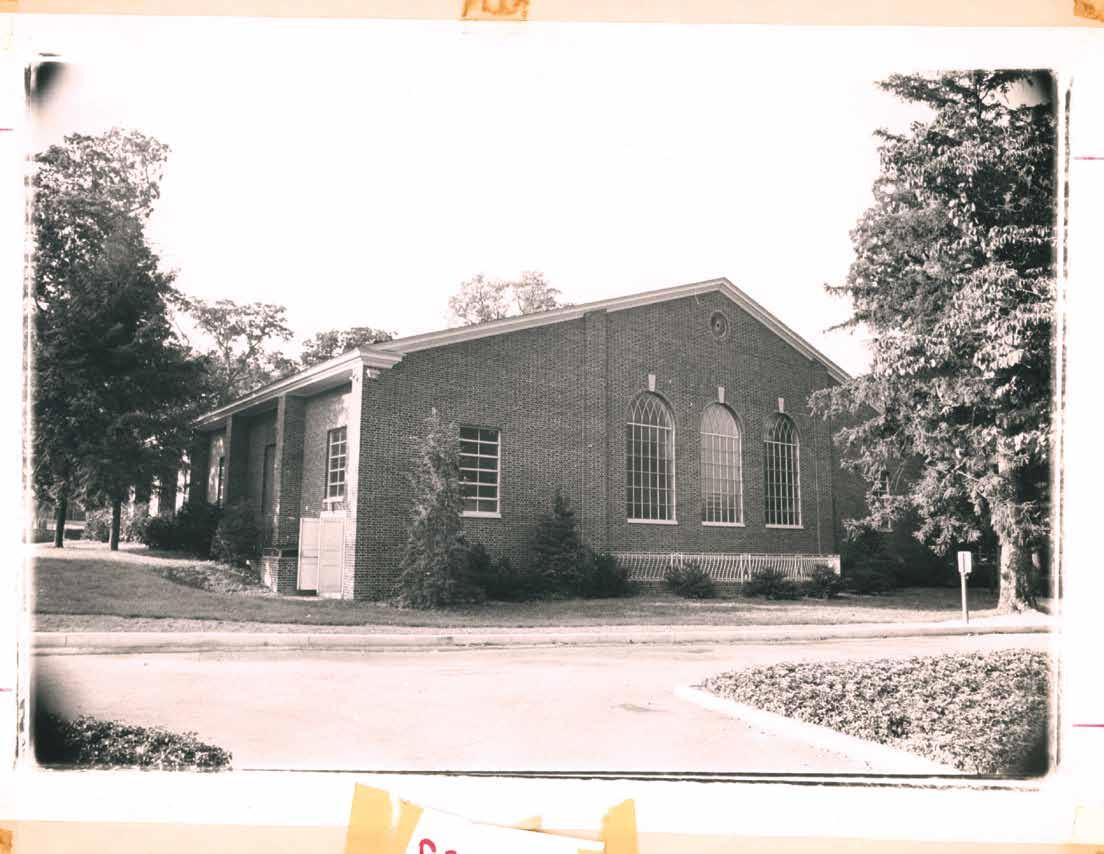

In the spring of 1929, the school made a major announcement. It was launching its firstever capital campaign and building its firstever structure from scratch—a gym. It started off brilliantly. Over 400 alumni gathered for a grand launching dinner, with speeches by headmaster Buck Wilson, chair of the board Logan MacCoy 1902 and Major General Smedley Butler 1898, which raised $135,000. But it took more than two years to complete the fundraising because of the Great Depression. In September 1930 the school broke ground on the gym. Over the next months, the construction ensued: they started pouring

concrete on the first of November. “The boys have had an absorbing interest in the whole project from its inception,” wrote the Haverford Alumni News-Letter in December 1930. “Large numbers of them have crowded around the building to watch the workmen before school starts in the morning, at the recess period, after lunch and as soon as classes are over in the afternoon.”

In June 1931 at the forty-seventh annual commencement, the school dedicated the Lillie B. Ryan Memorial Gymnasium. It was the best gym in the region and the largest building on Haverford’s campus. The Virginian brick glowed in the light filtered by the surrounding oak trees (only three trees were lost in the construction). Ryan boasted 32,000 square feet of space: a state-of-the-art swimming pool, a basketball gym that seated 1,000 spectators (no more steel mesh) and a giant space used initially for gymnastics and fencing but that during the Second World War was turned into the home of Haverford wrestling. “I thought I was in heaven,” said Jim Burdick. “When I first went into the new gym, I said, ‘Don’t wake me up.’”

On the east side of Ryan were three squash courts. The sport was on the rise: most city and country clubs in the area had courts and other schools were developing teams. Episcopal Academy opened their squash facility in November 1930 with a stand-alone building with two courts.

Although Ryan was not officially dedicated until June, the courts were ready in mid-winter. The April edition of the alumni magazine mentioned the finished squash courts: “The third unit of the building contains on the main floor three squash courts which have been built in the manner and according to the standards required by the National Squash Association.” That winter Haverford played a busy schedule, with home-and-away matches against Penn Charter, Episcopal, Hill School and a squad of Princeton alumni.

In the earliest years, Haverford performed at an extraordinarily high level. In 1887 Haverford helped found the Interacademic Athletic Association, along with Delancey School, Episcopal Academy, Germantown Academy and Penn Charter. In 1934 squash became an Inter-Ac sport. (The squash league was initially called the Philadelphia Junior Squash Racquets League, then the Philadelphia & Suburban Junior Squash Racquets League, and finally the Metropolitan Philadelphia Interscholastic Squash Racquets League; non-Inter-Ac schools were able to participate in its first years.) Haverford had a stranglehold on the Inter-Ac from the start, winning the league title for the first eleven years.

The dominance was impressive, considering how much the game was growing. Squash came to the fore at the turn of the century in Philadelphia—the world’s first squash association and league started there in 1903. In the 1920s the game spread rapidly across the Eastern Seaboard as high schools, colleges and clubs started building courts and fielding teams. Despite the Great Depression, the game accelerated: a men’s intercollegiate squash championship was started in 1931, and a national doubles championship was begun in 1933.

Haverford didn’t lose to Episcopal until 1945. Penn Charter proved to be stiffer competition, and the Maroon & Gold sometimes lost or tied them 3-3—it wasn’t until 1960 that official InterAc dual matches were seven-man events, not six. In February 1934 the Index called Penn Charter “our bitter rivals” and the matches were quite fierce and close.

Germantown Academy has never had a strong squash program. Haverford started playing GA in 1934 and every match was a 6-0 blanking. In 1938 the Patriots managed to earn its first individual win, in a 5-1 loss. Haverford topped GA twenty-four straight times. In 1951 GA shuttered their program, only resuming in 1975. Haverford beat them sixteen more times before they finally disappeared from the fixtures list in 1984.

Unlike every other sport at the school, Haverford’s squashmen regularly played collegiate teams. The tradition began in that first season in 1930 when, they faced off against Princeton’s junior

A cocky Episcopal team, coached by Darwin Kingsley, benched Tom Page, and George Bell played #2 in our second match v. EA. Early in the first game, I inadvertently whacked George’s ankle at the T, and he could barely move. I won the game and, given the overall team match was actually close, we had a crowd watching. Unfortunately he recovered and took the next three games pretty handily. We lost to EA 4-3.

— George Wood ’75

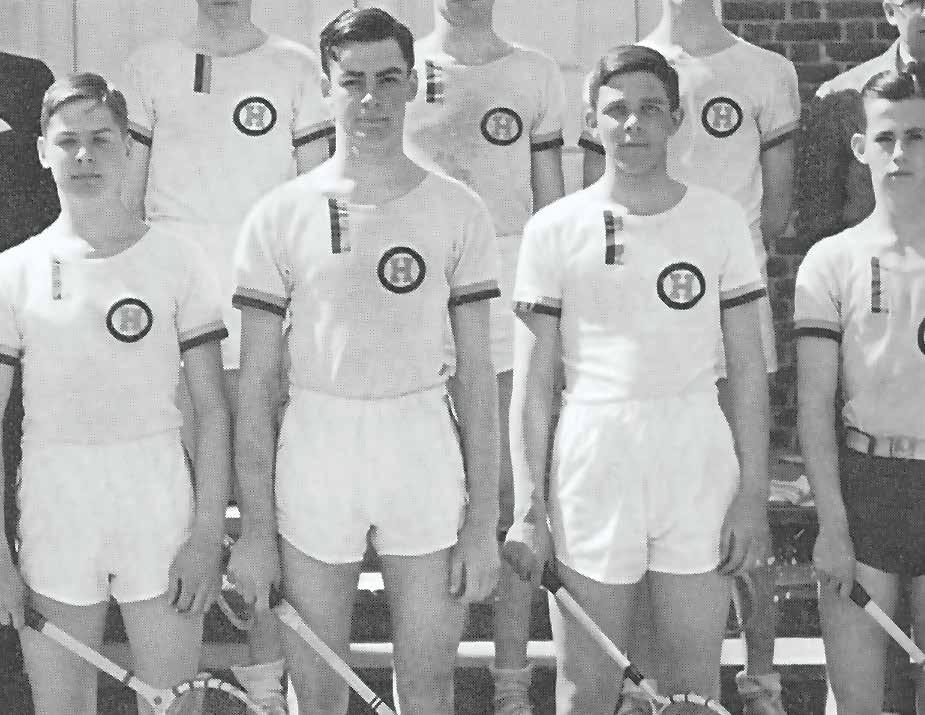

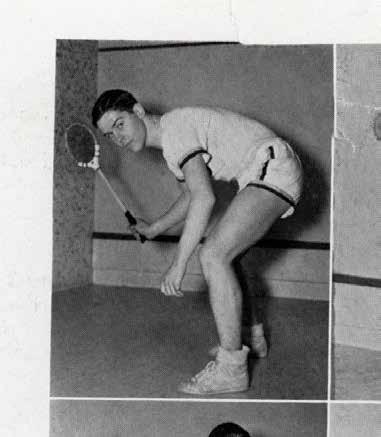

Haverford Squash A

sneakers. One wrestler in the early 1980s was notorious for patrolling the mats at squash practice time. “You learned by osmosis,” said Terry Spahr ’84. “I remembered seeing my brother Chris grabbed and twisted up into a pretzel by a wrestler, with the stern injunction ‘Don’t walk on my mat.’ After that, I wasn’t afraid of the perimeter.”

George Gerhard Miller ’55 succeeded Charlie Dethier. Although he descended from two

South Carolinian signers of the Declaration of Independence (Arthur Middleton and Edward Rutledge), Miller had a strong British accent. He was born and raised in England because his father, Philippus Miller, an Egyptologist, taught at Oxford. In 1948 the family returned to the U.S., and Miller attended Haverford before going to St. George’s School. He was in the class of 1959 at Penn, where he ran on the track team and then worked at a Philadelphia investment firm. In 1962 he returned to Haverford to teach English under the English master Bob Jameson. Miller eventually chaired the English department upon Jameson’s retirement in 1971. Later Miller became the head of the middle school. (In 1980 he left Haverford and

was the head of school at Lawrence Country Day School in Long Island and the American School of Guatemala in Guatemala City; he also worked at private schools in Kathmandu, Nepal, Vladivostok, Russia and Eleuthera, Bahamas. He died in September 2014 at the age of seventy-eight.)

Miller was a fitness maven. A member of Merion, he was a vigorous tennis player and cricketer—along with Tanny Sargent ’32, he restarted Merion’s cricket program—and played a lot of squash doubles. An early adaptor of running, he often ran barefoot around the perimeter of the Great Lawn at Merion and sometimes went for pre-dawn laps on Haverford’s track. “He was no-nonsense,” said Peter Classen ’70. “He’d have us doing court sprints ad nauseam. He was very into fitness. We all hated it.” Miller was famously the first person anyone knew to take up Nautilus weight training. “He loved exercise,” remembered Hobie Porter ’72. “His idea of practice was to take out the better players and play them, get a work out. It was almost like a challenge match.”

Miller so loved Haverford’s squash program that he created a most improved award in 1971.

One of the more surprising coaches in the squash program was Mike Mayock. A middle school math teacher, Mayock ran the middle school program from 1972 through 1984. He also was the varsity football coach in 1970-76 and 1983-87.

“Coaching squash at Haverford was a blast,” he said. “It was about talented players with great attitudes.”

“Mr. Mayock was my first Haverford squash coach,” said Wistar Wood ’79. “It seemed so out of place to have the varsity football coach—probably the most respected man in the athletic department—coaching the fourteen-year-old squash team. I was flattered to have his attention, as he was so important on campus. I will never forget the one-on-one lessons we would have on court four (that’s the far one, which was constructed from sheets of what seemed to be plywood and made a ‘thwack’ sound when the ball struck it, and it was COLD on that court). Mr. Mayock was about six foot five and 240 lbs and he would stand on the T and could seemingly reach either side wall with one stride. Getting him off the T was impossible. A great lesson for me to keep the ball along the walls and try to get the opponent BEHIND you.”

In the 1970s some of the fiercest matches quietly happened

on Saturdays at Ryan. Bo Dixon ’61, an English teacher at Haverford and later headmaster, and Mayock, would battle it out on the squash courts. “We’d play on Saturdays and Sundays and during vacations,” said Dixon. “He was built like a tight end and I was like a point guard. We’d have amazing matches. I’d be exhausted. It was painfully early in the morning. ‘I’m glad I’m going back to school tomorrow,’

I’d say to myself, ‘so I don’t have to do this again.’ Whoever won that weekend wouldn’t stop letting the other guy hear about it. We’d have big arguments. We didn’t budge an inch and we went after it. Whoever lost would say, ‘Let’s do another best of five,’ and the winner would say, ‘No, I’m done, I want to savor this one.’ It was carnage. Dixon and Mayock— we were total plumbers but we had great fun.”

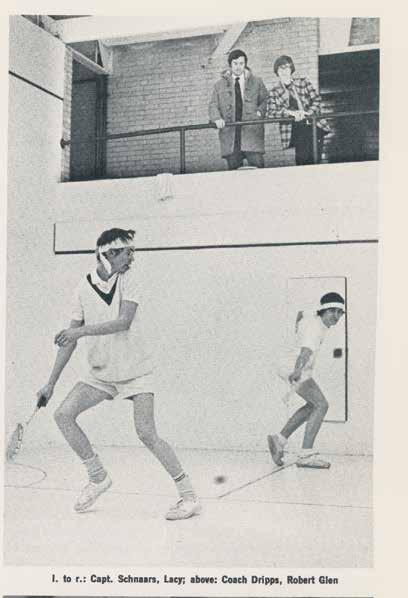

In 1973 Miller stepped aside and Craig Dripps ’65 took over. The fourth alum to helm the squad, Dripps slowly rebuilt the program. He added matches to the fixtures list—going from under a dozen to up to nearly twenty. “Mr. Dripps was a good motivator,” said George McFarland ’77. “We all liked him. He was a player’s coach. He was cool. We respected him.” Dripps had a robust Haverford pedigree. His father, Graham Dripps, was in the class of 1939 and his son, Wes Dripps, was in the class of

Haverford Squash A

He had come to Lancaster Avenue in fifth grade. He played tennis, almost going undefeated for the Fords one year and sat on the bench with the football team (getting inducted with the 1964 team into the Haverford Hall of Fame). He captained the tennis team at Denison. After serving in the Navy for three years, he came back to Haverford in September 1972. He initially taught ancient history and then math; and he started coaching junior varsity tennis. “George Miller was a real character,” said Dripps. “He was hilarious, a Renaissance guy. We played tennis a lot together over at Merion. When they asked me to take over the squash program, I had never picked up a racquet. I didn’t know anything about squash. I was quick to learn that squash is not the same as tennis. I couldn’t make my own team. But Neil Buckley had never wrestled a day in his life—he was an inspiration for me. I figured

out that I could analyze their game, their opponent’s game. I could inspire them. I was able to relate to the kids and get along with them. I could teach them how to win.”

An inflection point came in the middle of the decade. At first the team continued to struggle against other league opponents like Penn Charter and Episcopal. “The match [against PC] was very depressing to both the team and Mr. Dripps,” the Index reported in February 1974, “for the team failed to procure a single game throughout the entire match.”

In 1976 the so-called Drippermen defeated EA twice, an emphatic 6-1 the second time. At the end of the season, the Fords could claim the Inter-Ac title, based on having won more Inter-Ac individual matches than Chestnut Hill, but the final dual match, Haverford v. Penn Charter, would determine it. If the Fords won 7-0 or 6-1, the title would come back to Lancaster Avenue for the first time since 1964; 5-2 was a tie with CHA; 4-3 meant CHA won the title. Just before the match, Tom Woodward ’76 at No.5 fell ill, and junior Jim Buck ’77 was called up from the junior varsity for only his second varsity match ever. Buck at No.7 won 3-0 and the Fords captured the dual match 6-1. “Coming off the court,” said Buck, “Craig gave me a hug and shook my hand and said, ‘You’ve just gotten yourself a varsity letter.’”

The same scenario occurred the following year, with both teams splitting matches 4-3, and this year, each had the exact same number of total Inter-Ac match wins. That 4-3 loss to CHA—with a No.2 Joe Somers ’77 out with an injury and George McFarland ’77 losing a tough match to CHA’s Bill Ramsay at No.1—was the last loss to an Inter-Ac school until 1994. “It was a tough one,” said Craig Dripps ’65. “Joe had a separated shoulder. Do you default his position or move everyone up? We moved everyone up and lost 4-3.”

Geordie Lemmon ’79 was much like Ben Heckscher ’53 or Ned Edwards ’76 (who played on the varsity in eighth grade in 1972 before

1965-1978

“My single memory of Haverford squash is that of not playing,” he said. “I was never good enough to make the team.”

The Mellor brothers were a remarkable trio. Three brothers—Rick ’63, Doug ’65 and Steve ’71—all served as captain of the team. It is the only time in Haverford history that three brothers were all captains of the same sports team. Later on, Rick worked as a squash pro at the Tennis & Racquet Club

— Wistar Wood ’79 going to Westminster) or Larry Terrell ’66—another outstanding young Haverford player and future national champion who left early for boarding school. Lemmon played on the team in eighth and ninth grade and halfway through tenth grade before departing for Exeter. “All I really recall was how cold the courts were,” he said, “and they were next to the wrestling room, which was really hot.” Another future national champion was Jamie Heldring ’74. He didn’t get a varsity letter.

All of the great players in the Inter-Ac seemed to come from Merion Cricket Club. This was particularly true in the years before us when the Episcopal greats played there. My great inspiration there was Tom Page from EA, who would let me challenge him for his court after his workout (Merion courts booked in forty-minute intervals, and it was hard to get court time on weekends as a junior player, so even five minutes of someone’s court time was precious). Tommy would play me left-handed, or he would spot me several points, or he would just hit forehand rails, something to keep it competitive; always a thrill to play with him. When Haverford School held varsity practices, Dripps and Haines would send Merion members to Merion to practice together, since courts at Haverford were scarce, particularly since no one wanted to play on court four. So routinely the contingent practicing daily at Merion was Wood, Clothier, McFarland, Bogle, Thornton, Harrity, etc. Weird to think about now, but I think the coaches had us return to Ryan gym afterwards for team bonding; the team never felt split between “us and them,” although it could have easily.

and the Harvard Club of Boston. Their father, Eddie Mellor ’34, played basketball and tennis at Haverford (and later squash doubles at Merion).

George McFarland ’77 had one famous victory in this era. McFarland had played basketball in ninth grade, but then new head basketball coach Ray Edelman arrived, bringing in very good players, and McFarland switched to squash, a sport he had played at Merion. He developed a long rivalry with Episcopal’s No.1 John Nimick. A future U.S. Squash Hall of Famer, Nimick played on EA’s varsity for five years and had never lost.

Until their senior year. At EA, the Fords had won 5-2, but in the second dual match at Ryan Gym, Haverford blanked EA 7-0, the first time it had bageled the Churchmen in fifteen years. McFarland trained hard prior to the match with assistant coach

“It was a great match,” said Wistar Wood ’79. “It was the first shutout against EA in a long, long time. George Haines had instructed McFarland to move Nimick up and back with drop shots and deep rails, since Nimick was a big guy and making him move around was the best way to wear him out. It worked. A great victory for George, who never beat Nimick again (we were all teammates at Princeton) and a remarkable shutout of EA which had been so dominant in prior years with the Pages, Havens and Bell, etc.”

Another bete noire of EA was Joe Fabiani ’78. He started squash with Norm Bramall at the Cynwyd Club, who taught him to “do your homework” and spend time hitting solo. Beginning in 1967, Episcopal hosted an InterAc individual tournament at the end of the season.

No Haverford player won it until Fabiani clawed his way to victory in 1978.

George Haines. “We spent a week getting ready,” said McFarland. “He crafted a game plan. I had to wear John down, minimize errors, long points. I was on cloud nine after winning. John was gracious. After shaking hands, George gave me a hug. I took off my shoes and socks and had blisters all over my feet.” McFarland was down 7-1 in the fifth game but came back to win.

After that, the dam broke: a Haverford boy won it every year but one until the event was stopped after 1991.

“Haverford squash players were a different breed from the wrestlers and swimmers,” said Dripps. “No other sport generated that many leaders as adults, successful men with strength of character. Everyone was exceptional.”

Joe Fabiani, Craig Dripps, Bob Clothier and Wistar Wood.

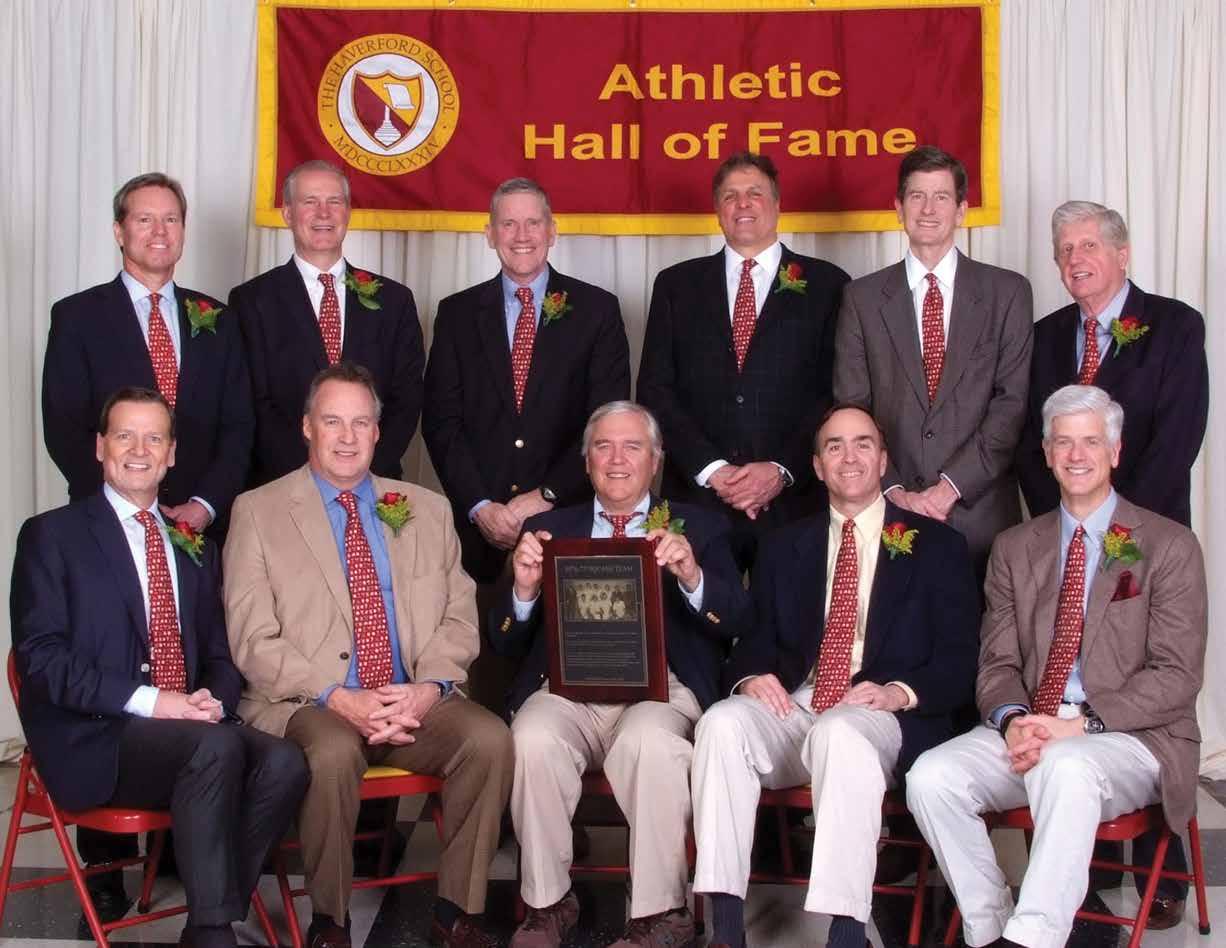

The 1976-77 team gathered for their Haverford Athletic Hall of Fame induction in February 2016 (Back row, l-r) Gerry van Arkel ’79, Wistar Wood ’79, Steve Loughran ’78, Joe Fabiani ’78, Bob Clothier ’79, and Ted Rauch ’57; (front row, l-r) John Bogle ’77, Joe Somers ’77, Craig Dripps ’65, George McFarland ’77 and Jim Buck ’77

Episcopal Academy

Leave the Van Running

The origin of the word

rival is in the Middle French word rivus, meaning a person who drinks from the same brook as another. It indicates a relationship, a camaraderie, a partnership of equality as much as simply a person to compete against.

For a century, Episcopal and Haverford have drunk out of the same squash stream. It has almost always been a one-sided rivalry, with one school dominating for long stretches.

Episcopal Academy

| Leave the Van Running

From 1913 until 1945, the Fords maintained a remarkable streak in which they remained unbeaten against the Churchmen with twenty-six wins and two 3-3 ties.

After a post-war slump, Haverford revived. In 1953 the Fords broke a fiftynine match EA win streak and then lost just once to the Churchmen in the next eight years. Then another bottoming-out, as Episcopal went on an epic tear in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Maroon & Gold lost every match to the Churchmen from 1967 to 1976.

Led by a string of brother tandems (and threesomes)—Bottger, Havens and Page—and future national champions like Bob Callahan, Gil Mateer and John Nimick and coached by U.S. Squash Hall of Famers like Darwin Kingsley, Diehl Mateer and Tom Poor, EA was a juggernaut.

“Sometimes when we played EA,” said Pete Classen ’70, “we’d arrive on their campus and joke and say ‘leave the van running—we’ll be right back.’”

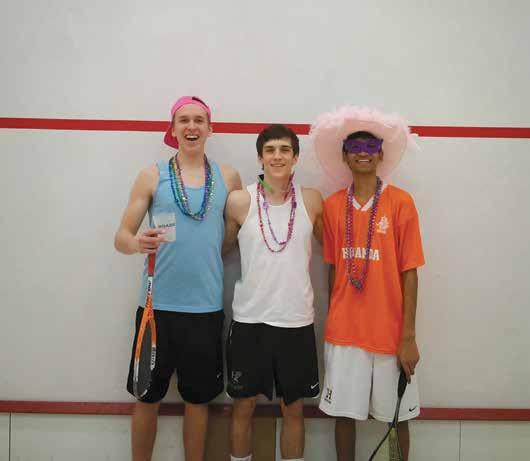

TOC | VOLLEY FIGURE EIGHT

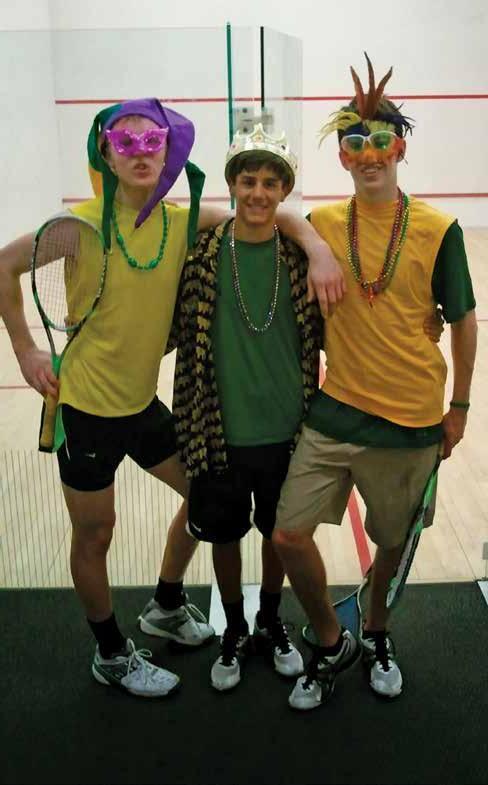

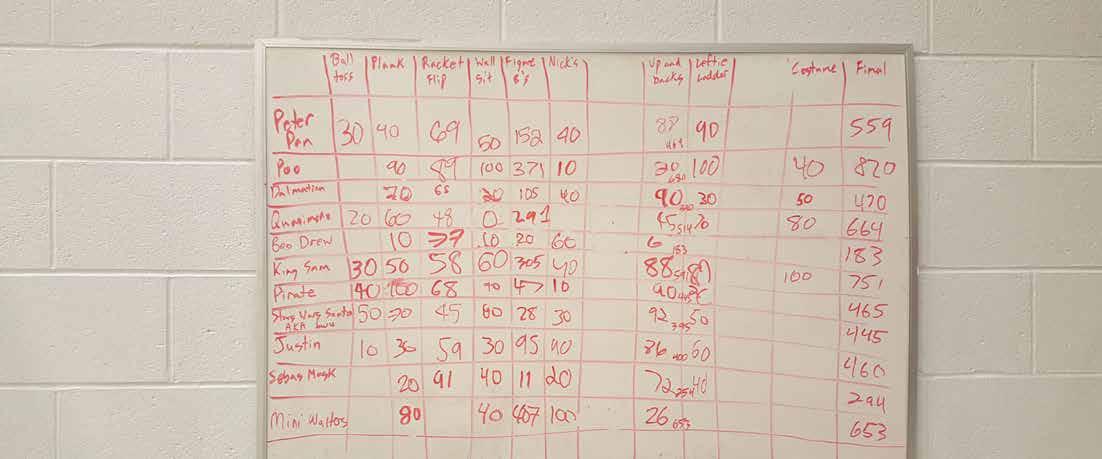

During Andrew Poolman’s tenure as head coach, the most memorable day of the year was the day of the Tournament of Champions. It started during winter break or the reading period before exams in January. There were no matches scheduled, and Poolman created a great afternoon practice. It was named after the Tournament of Champions, the pro event in Grand Central Terminal each January.

It was a wonderful way to have some good team bonding,” said Poolman. “Some good fun and bring the entire team together. Everyone looked forward to it.

Some of the events were a crazy skills competition like how many times you could flip your racquet in a minute to how close could you roll a ball from the back wall and have it stop near the front wall. Each year the captions picked a theme like Mardi Gras or USA.

“TOC was definitely a fun little concoction that Mr. Poolman started when he took over as coach,” said B.G.

Lemmon ‘12. “It was always either during or just after our winter break, which coincided

with the real Tournament of Champions in NYC. Each year there would be a different theme. The day would consist of competitions from who could hold the longest plank, longest wall sit, do the most figure eights in a row, most targets hit on the court, etc. It was a nice way to get excited about the game again during the long winter break as the season hits the ground running right when school started again. There were points allocated for the best costume, and then there was a winner by the end who essentially just got bragging rights, but it was such a blast.”

“The Haverford School Tournament of Champions resembled the Grand Central tournament in name and name only,” said Jay Losty ‘15. “The seniors on the team chose the theme for the year’s TOC, and everyone decked themselves out in costume. The event was used as a de-stresser before the big competitions like the National High Schools. The TOC involved a dozen or so different competitions, which ranged from conventional to absurd. Dylan Henderson ’14 was the man to beat for the most racquet flips in a minute competition. Paxton Moore ’12 held the record in push-ups. Thomas Walker ’14

was the several times champion of the longest wall-sit competition (over five minutes). My claim to fame was the volley figure eight competition, in which I held an undefeated record during my five years on the team, with a high score of 213 volleys in a row. The most sought-after title, however, was the costume competition, in which B.G. Lemmon managed to place runner-up almost every year.”

7

National Champions 2016-2019

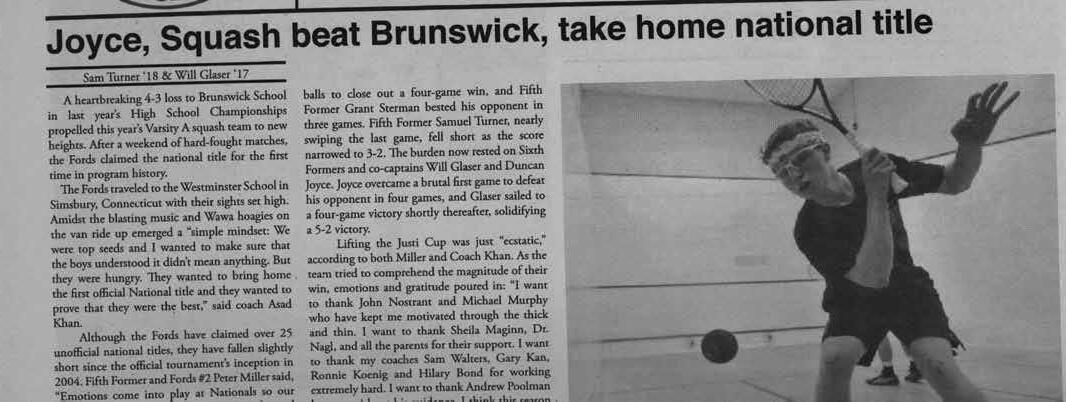

In 2017 Haverford finally claimed its first official National High School title.

Coaching the squad was Asad Riaz Khan. A national junior champion at U12, U17 and U19 levels in Pakistan, Khan had grown up in Karachi, then Islamabad. He was the fourth of four brothers—his older brother Imran came over to the States long before Asad and worked at a number of Philadelphia clubs. Asad attended Denison, playing No.1 all four years. After graduating in 2010, he coached at the Pittsburgh Golf Club and Shady Side Academy, played on the professional squash doubles tour and assisted his brother Imran at Malvern Prep. In 2015 he took the middle school boys to the National Middle Schools; the following year, when Bill Strong retired, he became the full-time middle school coach and led the team to the middle school national title. When Poolman retired after the 2016, Khan took over the program.

In his first season, Khan brought the long-sought national title to Lancaster Avenue. “I added more drills, more fitness and more focus,” Khan said. “My philosophy was ‘team first.’” A number of players on the team trained especially hard all summer, pointing towards a rematch. Khan also started a new tradition. In 2018 the team started going to Baldwin to play the girls there in an exhibition match during their spirit week.

Ironically, the matches at the Nationals were played at Westminster, a boarding school in Connecticut, but after its skeins of failure against Taft and Avon, playing at Westminster turned out not to be a negative. Justin Shah ’16 texted the team from Virginia on Friday afternoon. “Good luck this weekend,” he wrote. “It’s getting too long without a title. Please smack Wick.” The boys were loose. Duncan Joyce ’17 brought an X Box and the boys played FIFA 16 in his hotel room.

Haverford plowed through to the finals, winning 7-0 over Harriton Lower Merion, 6-1 over St. George’s and 7-0 over Belmont Hill.

The 2016-17 national championship team celebrated on the glass court at the U.S. Open at Drexel in October 2017: (front l-r) Tyler Burt ’18, Nick Parente’19, Duncan Joyce’17, Carter Joyce ’20 and Yeshwin Sankuratri ’20; (back row l-r) athletic director John Nostrant, Peter Miller ’18, Spencer Yager ’19, Sam Turner’18, Grant Sterman ’18, Jack Burton ’18, Christian Shah ’20 and head coach Asad Khan.

On Sunday 12 February 2017, the Maroon & Gold faced Brunswick again. Tension was high. “Let’s get it,’ texted Shah. “Rematch city,” responded Duncan Joyce. “The rivalry with Brunswick was real,” said Peter Miller ’18. “They were just like us, the same sort of kid. We knew them well, we had played against them in tournaments for years.” “We were super nervous,” said Duncan Joyce. “We wanted to win so badly. The year before was so awful.”

This time, it wasn’t close. The top five Fords won. Not a single match went beyond four games. Peter Miller knocked out Wick’s hero from the previous year, Max Finkelstein 11-9 in the fourth. “The team was pushing you,” said Spencer Yager ’19. “Everyone was going nuts. You were playing for your team, for a national championship. There was so much adrenaline.”

Duncan Joyce ’17 grabbed the clinching match. He came off after the first game having been blown away by Tyler Carney. “He was a bit rattled,” said coach Asad Khan. “I told him, ‘You’re playing a guy who likes to hit the ball hard. Instead, play angles, start lifting the ball, delay shots. Don’t go short too early. Bore him.

Hold your shots and then go for drops.’” Joyce won the next three games.

Up in the fourth, he squandered two match balls. Then Joyce delicately feathered a soft forehand drop off a shot of Carney’s. Carney responded but his drive was poor.

It was bittersweet for Khan. He had discussed with his father his goal of winning the national title but five months earlier, back in October, his father had suddenly died, at the age of sixty-five, from heart failure. Maybe the most poignant scene at that moment was back on campus at Haverford.

The referee said, “Stroke to Joyce.” Joyce and Carney shook hands and briefly hugged. The team poured onto the court. Tears of joy and relief flooded out among the parents. A century of aspiration had concluded, finally, with a victory.

That Sunday afternoon, Andrew Poolman took his two young boys over to the empty gym to run around. He was following the livescoring feature at US Squash’s website on his phone. While his children played on court, he watched the Fords win the title. “I was so elated for the boys,” he said, “and for Asad. Winning the national championship—it was so amazing.

Haverford

Finally, an official title: (l-r) Grant Sterman ’18, Peter Miller ’18, Spencer Yager ’19, Will Glaser ’17, Duncan Joyce ’17, Bill Wu ’17, Sam Turner ’18 and Christian Shah ’20.

But at the same time, this was exactly why I had stepped down. It was a winter Sunday and my new priority was to be with my family.”

Sean Hughes ’16 was following it on his phone. “I was reloading the page on US Squash’s website,” he said. “I was so happy and for them to beat Brunswick was great. I texted them all right after it happened.”

The next morning Duncan Joyce ’17 posted on social media a photo of him sleeping with the Justi trophy.

The season ended with a perfect record. Haverford had won eighty-one of ninety-one individual matches. A four-course dinner at Merion concluded the season. The parents made miniature national championship banners, just like the official one, complete with grommets, for the kids and pendant necklaces for their mothers. Then in October, US Squash invited the squad to celebrate on the glass court at the U.S. Open.

The glory didn’t last that long. The first match of the 2017-18 season came in early December against

Brunswick in Greenwich. The Bruins thrashed the Fords 8-1, giving an early hint that repeating as national champions was going to be hard. “Resiliency has become the early theme, as this squad has encountered challenges right out of the gate,” wrote Brant Henderson ’74.

At the 2018 National High Schools, the team made the finals but lost 5-2 to Brunswick. Finkelstein at No.1 topped Peter Miller ’18 11-4 in the fifth; only Grant Sterman ’18 at No.3 and Quintin Campbell ’21 at No.7 grabbed wins. Christian Shah ’20 lost 11-8 in the fifth at No.6. It was an anti-climatic moment in another way as well. The match was held at Philadelphia Cricket Club, but unlike the tremendous atmosphere two years earlier, it was fairly subdued there that Sunday afternoon. Many people were focused on another athletic event occurring just a couple of hours later: the Philadelphia Eagles playing in Super Bowl LII.

In 2019 the Fords again made the finals, but barely: in the semis, the Maroon & Gold went down 3-2 against St. Paul’s, with two very tight five-game losses. But the squad clawed back for a 4-3 victory, with sophomore Quintin Campbell at No.4 clinching the win 11-9 in

Haverford Squash A Chronicle of Excellence

consecutive year. Only Campbell could pull off a win (11-8 in the fifth); Christian Shah ’20 at No.3 came back from a 2-0 deficit only to lose 11-9 in the fifth. Later in the spring, Khan stepped down from his position and moved to Buffalo to coach at Nardin Academy.

The National Middle Schools, founded in 2008 and always hosted at Yale’s Payne Whitney Gymnasium, took a couple of iterations to take hold. In the beginning, Haverford had an unsettled attitude, as did many Inter-Ac schools, about the tournament. Some years it sent a team, some years it didn’t. A squad went in 2010; winning two matches, it made it to the finals before losing to Brunswick 4-1. In 2011 it lost again to Brunswick 4-1 and finished fourth. In 2012 it didn’t send a team. In 2013 parents hired Luis Sanchez to take the boys. Sanchez had worked at Rockaway Hunting Club, New York Sports Club, the Greate Bay in Atlantic City and was presently at Berwyn Squash. He had come to Lancaster Avenue as a substitute Spanish teacher for the middle and upper school and had assisted Andrew Poolman.

With Sanchez’s help, Haverford, seeded two, lost a heartbreaker in the semis to Pingry 3-2 and beat Springside Chestnut Hill 5-0 to come in third.

Coach Bill Strong was reluctant to send a squad. He came from an era when squash was just another activity for the three-sport middle school athlete, not something that consumed their lives. In the fall of 2013, when talk came around again about if the middle school team would go to the Nationals, Strong wrote a long, thoughtful letter to the boys’ parents:

I was Haverford’s Varsity coach about 15 years ago when a Haverford School Mom, Melinda Justi, single-handedly created the High School Nationals through her own persistence. While I was the Varsity Coach, Haverford enthusiastically participated from the very beginning and the HS Nationals filled an important

Parents play a key role in supporting their student athletes. TOP (back row, l-r) Genie Logue, Laina Driscoll and Lindsey Page; (front row) Jamea Campbell, Karen Zimmer and Katharine Joyce. MIDDLE (hoisting the Justi Cup l-r): Paige Yager, Barbara Miller, Ruchira Glaser, Katharine Joyce, Jamine Shechter, Stacey Turner and Sherry Wang. BOTTOM (l-r): Shailen Shah, Rick Campbell, Sam Baker, Raju Sankuratri, Kevin Leahy, Gary Zimmer and Gary Herbert.

void in creating a way for HS teams from different regions to compete interscholastically. We always looked forward to the opportunity to see how we would fit into the national HS pecking order, and the trip was a solid end of year team-bonding experience.

While I see the HS Nationals as being very beneficial, I’ve never had the same feeling about the MS Nationals. My major reservations towards the MS tournament are as follows:

1. I see MS team squash as being more developmental than highly competitive and I don’t see a tangible benefit in participating in a National MS Team Tournament as a proving ground against all other schools. There will be time for that in High School.

2. I worry that participation in the MS Nationals will dilute some of the novelty of the boys’ HS Nationals experience in upcoming years especially since both events are held at Yale. If a boy does a couple trips to the MS Nationals at Yale, he could be a lot less jazzed when he gets the chance again in the Upper School.

3. Year in and out we get solid competition from the local schools (e.g. EA/ CHA) that we play twice a year each. It isn’t as though we have to travel to New England to get good team competition.

4. The boys who are good enough to play on our MS Nationals team are the same guys who are playing a healthy number of tournaments during the rest of the year and are already getting frequent tournament competition. Too much maybe? Playing an additional tournament doesn’t provide much value-added and it’s at a venue (Yale) which the boys have been to, and will be at, countless times in their junior careers. It’s not as though geographic and collegiate horizons are being broadened by attending.

5. It’s not helpful to miss another day of school on top of the other days that are missed due to other squash tournaments. Despite my objections to the event, I do recognize that the boys seem to want to participate and I will not be the killjoy who dictates they cannot go.

I will leave my reservations to your consideration and you can determine their merit. If the parents (you) decide to take the team, I will leave it to the

parents to make the arrangements and run the show at Yale assuming the school administration has no objection to this arrangement—I will check with Mr. Greytok about this.

If you decide to go, I’ll be happy to work with you in arranging the ladder, coordinating challenge matches prior to the trip, if necessary, etc.

The parents wanted to send the team and through Andrew Poolman hired Jamie Macaulay to temporarily coach the team. Macaulay grew up on Unst, one of the Shetland islands in northern Scotland, population 600 with one squash court. As a teenager he trained fulltime in Edinburgh, went to university and then got into coaching: the Scottish junior squad, the national team at the World Deaf Championships and at a club in Glasgow. He came to the U.S. in 2010 and helped set up the Scozzie junior program at Fairmount (he was the SCO and Paul Frank, from Australia, was the auZZIE). Many of the kids on the Haverford team trained at Scozzie and worked with Macaulay. He trained the team for a quick fortnight before the Nationals.

“We had a team of real characters,” said Macaulay. “Tyler was the joker, the teaser. He amped the guys up before the finals. Sam was the calming influence. The morning of the final he could talk people off the ledges. Christian Shah ’20 was the baby. Grant was always happy and relaxed, reliable and firm. Spencer was creative. He’d come up with ridiculous, audacious shots. He’d figure out when we’d meet for breakfast. Peter was the leader. It all flowed through him. Haverford held these guys as leaders. The other teams had talented athletes. Our guys had big shoulders.”

The Maroon & Gold won their first two matches 5-0, then beat Bronxville 4-1. The night before the final, the parents were downstairs at the hotel restaurant, and the boys played Hotel Tag, skidding across marble floors and running up and down stairwells.

In the final, the Fords outlasted Greenwich County Day School 3-2. Spencer Yager ’19 at No.4 and Grant Sterman ’18 at No.1 both lost in five close games, but Sam Turner ’18 at No.2, Peter Miller ’18 at

No.3 and Tyler Burt ’18 at No.5 all came through convincingly with victories. “Tyler stepped on court and was intense,” Macaulay said. “He hit the ball hard and ran hard. His match fired up the team.” Turner was predicted to lose, but he came through with an upset. “It was one of the best matches I’ve seen him play,” Macaulay said. “He was composed under pressure. He calmed down because of the pressure. He didn’t look discomforted. Just poised. It was incredible to watch.” Turner clinched the victory. Grant was in the middle of a tough fivegamer, but in hindsight the bubble had burst and his match wasn’t needed.

After the match everyone went for pizza. “We were in shock,” said Macaulay. “That was the overarching emotion. We talked through what had happened over the last three hours. These young men were a bit quiet, looking at their medals. They unrolled the blue poster and put it on the table and looked at it for fifteen minutes. Wow. This was six young men. This is what it meant to be a Haverford boy.”

They had won Haverford’s first official national squash team title. Three years later these players would help Haverford win the National High Schools. “They had broad shoulders,” said Macaulay. “You wanted them in the fox hole with you.”

In 2015 the middle school team lost in the semis to Brunswick 4-1 and then to Calvert 3-2 to come in fourth.

In 2016, with a new coach, Asad Khan, the team battled with a minor snowstorm. Two schools in Division I pulled out, including Brunswick. Haverford, sensing an opening, dashed in. They cruised with two straight 5-0 wins and then two 4-1 wins, topping Bronxville in the semis and Springside Chestnut Hill in the finals. Quintin Campbell ’21 clinched the third match in the finals on the glass court, overcoming Mac Aube who he had never beaten before. “It felt really good,” said Khan. “I had trouble believing we had won it.”

Ron Koenig replaced Khan as the middle school coach. Koenig had grown

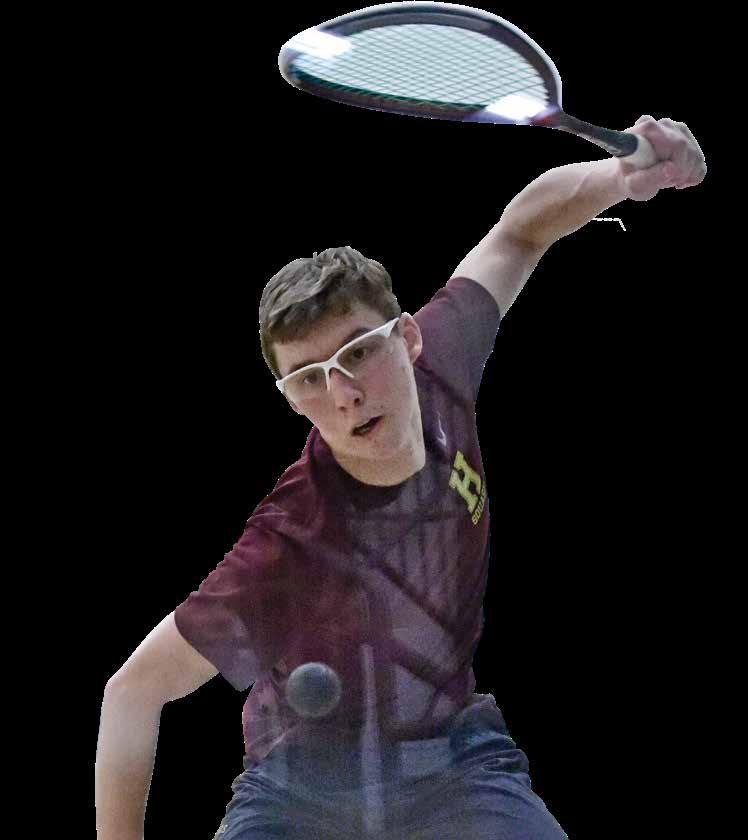

(left) Post-game hug: at the 2019 National High Schools, Yeshwin Sankuratri ’20 is greeted by teammates Spencer Yager ’19, Robert Driscoll ’20 and Carter Joyce ’20 after coming off court. Right top: Christian Shah ’20; right middle: Quintin Campbell ’21.

up in Frankfurt, Germany and was a badminton player. He briefly played squash in high school at Suffield Academy in Connecticut. After college at Temple, he started coaching squash in the Philadelphia area, including at Malvern Prep. “Middle school squash is high energy,” Koenig said. “It is the last period of school, and so some of practice is simply to get them to run around. I tried to build a team, make sure it was about sportsmanship and leadership—the big picture.”

In 2017 Haverford lost in the semis 5-0 to Brunswick A and then topped Brunswick B 3-2 for third place. It was a riveting final match, with Quintin Campbell ’21 at No.1 surviving 12-10 in the fifth.

In 2018 Haverford lost in the finals to Brunwick 5-0. Only one match went beyond three games. “Brunswick was extremely deep,” said Koenig. “We were younger. It wasn’t that close.”

In 2019 the Fords romped to a third national title, losing just one match over the weekend and blanking Bronxville 5-0 in the final. This time, Haverford was much stronger—only one match went beyond three games. “We were better on paper,” Koenig said, “but you never know.” The third win was Graeme Herbert ’24 at No.3. “We didn’t want to celebrate too much—it is not like the National High Schools.”

It was, though, a milestone to remember. In Haverford Squash’s ninety-first season, the team again made history, reaching the finals of the National High Schools and winning the National Middle Schools. The program, again, was the best in the country.

(right) The latest champions: (l-r) Drew Glaser ’24, Jamie Stait ’25, Ethan Lee ’24, Wills Burt ’23, Graeme Herbert ’24 and Owen Yu ’23.

Another snowy day getting into the van: (l-r) Spencer Yager ’19, Peter Miller ’18, Will Glaser ’17 and Bill Wu ’17.

HEAD COACH

Matthew Baird, III (1929-30)

H. Dony Easterline (1930-36)

Van Horn Ely, Jr. ’24 (1936-39)

Charles P. Dethier (1938-65)

William M. Prizer, Jr. ’39 (1941-44)

William White (1940-47)

George G. Miller ’55 (1965-73)

Craig R. Dripps ’65 (1973-78)

George E. Haines, Jr. (1978-79; 1980-89)

William A. Strong (1979-80; 1989-2010)

Andrew S. Poolman (2010-16)

Asad R. Khan (2016-19)

Haines

Kahn

Miller

White

Prizer

Dethier

Dripps

Easterline

Poolman Strong