U19 U23 WORLDS

U.S. FOURS WIN AT U19 + U23 WORLDS

GOOD KNIGHT

2025 Henley Royal Regatta

TRADE IN. TRADE UP.

Stay in Command for Fall Racing.

Upgrade to the latest CoxBox® GPS model with a $150 trade-in value on your current unit.

Whether you’re still using a legacy CoxBox or simply due for a refresh, now’s the time to step up to the latest generation of CoxBox GPS — engineered for today’s demanding crews and racing edge.

Why make the switch?

• Built-in GPS: Speed, split, distance, and real-time feedback

• LiNK Logbook App integration: Wireless data transfer & session review

• Same trusted audio system, redesigned for modern performance

• Backed by a new 2 year warranty and reliable customer service TRADE IN YOUR OLD COXBOX AND GET $ 15 0 OF F THE LATEST COXBOX GPS

Mens Senior 1x Matthew Finley

At the Canadian Henley

Mens U23 LtWt Riley Watson

Winner Womens U17 1x Natalie McClure

At 25 Lbs. the Lightest Singles in Production

• Less Drag, More Speed

• Lighter Feel, Higher Stroke Rate

• Easier to Carry

Follow Rowing News on social media by scanning this QR code with your smart phone.

FEATURES

Revenge of the Lights

Shunned by the Olympics and World Rowing, rowers of “normal size” are posting sensational times, racing to exciting finishes, and occasionally beating the big boys.

BY ANDY ANDERSON

Wyatt Allen Interview

He was named Coach of the Year after Dartmouth went undefeated in the regular season and won silver at Eastern Sprints and bronze at the IRA. “There is no substitute for internal competition and the way that can raise the level of performance.”

BY CHIP DAVIS

DEPARTMENTS

25 QUICK CATCHES

News 2025 World Rowing Under 19 Championships

2025 World Rowing Under 23 Championships

2025 Royal Canadian Henley Regatta

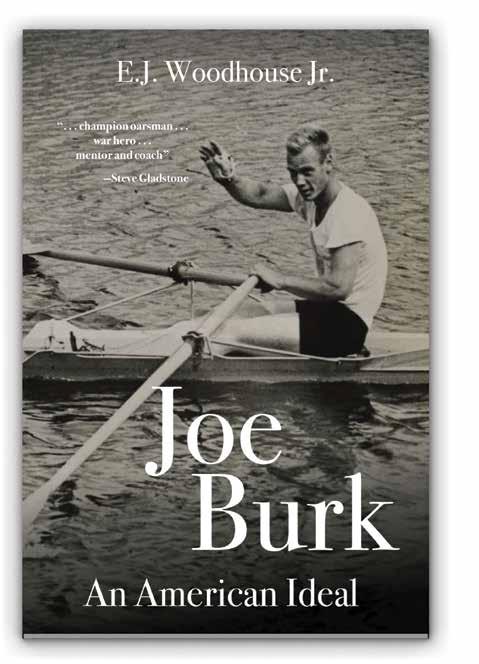

Joe Burk, American Ideal

57 TRAINING

Sports Science A Polarized Path to Success

Coxing The Golden Rule of Coxing

Recruiting Subtle But Important Differences

Fuel From the Front Lines of Sport Nutrition Research

Training Six Pillars of Performance

Coach Development Coaching for the Long Game

Doctor Rowing

FROM THE EDITOR

CHIP DAVIS

Purposeful Conflicts of Interest

If you work in the sport of rowing and you don’t have conflicts of interest, you must be new.

From our school crews to our summer clubs to our universities to our camps, sculling groups, and erg gyms, anyone who does anything in our sport beyond just rowing the boat will be tasked with working for one set of interests while having a personal conflicting interest. A situation in which the aims of two or more parties are incompatible is the definition of a conflict of interest.

It also describes a regatta.

We all want our crew to win; only one can. But our greater interest, fundamental to the integrity of the sport, is that the fastest crew wins. By holding themselves to that greater interest, organizers and volunteers who are alumni and supporters of participating crews can still work at regattas and make them fair. The desire for our crew to win and the principle that winning means being the fastest crew is rowing’s confluence, not conflict, of interest.

The desire for our crew to win and the principle that winning means being the fastest crew is rowing’s confluence, not conflict, of interest.

When we asked Dotty Brown to write about Ed Woodhouse’s new book about legendary oarsman and coach Joe Burk, she initially disqualified herself because she had helped Woodhouse and promoted his book.

But our greater interest is to inform the rowing community of the great tale of Joe Burk, who coached Harry Parker and espoused sculling while putting together the fastest eights in the last century (a formula very much in contemporary favor).

So Brown’s piece (page 32) isn’t impartial but it serves our readers by acquainting them with an inspiring rower and coach, thereby enhancing their enjoyment of our sport.

As a former captain of the Dartmouth lightweights, I bleed Green, and in assigning the two features in this issue (as well as writing one of them), I lined up blatant conflicts of interest.

My interview with Dartmouth coach Wyatt Allen tells the story of his quarter-century journey from club novice to Olympic champion and now the IRCA Coach of the Year in a way I hope inspires other athletes and coaches to continue their own rowing journeys.

In Andy Anderson’s celebration of the heights lightweight rowers have reached recently, we recognize the excellence achieved within a segment of our sport that hasn’t let lost support at the Olympic level slow it down on collegiate and international racecourses.

Serving our community with these stories is the confluence, not conflict, of our interests.

The Gifts of Rowing

Thank you for the “Quick Catches” piece on Coach Ry Hills. I am incredibly grateful to have worked with Ry, and there is no one more deserving to have her rowing legacy recognized.

Thank you also for “The Virginia Paradox” by Tom Matlack in the July issue. I sat down to read it expecting to take away a few nuggets from Coach Biller’s coaching style, perhaps learn a bit more about UVA’s team culture, but the end product was much more profound.

Mr. Matlack summed up so much that I love about our sport (and more specifically, club rowing). The article is a wonderful reminder of our sport’s gifts: its incredible capacity to teach, forge deep relationships, and become better human beings while connecting with something much greater than self.

Doug Welling Head coach of rowing Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine

Overlooked coxswain

Doctor Rowing was right to call attention to the spectacular season that the Trinity men’s eight had, but to end his article with “It was a special year for a special group of guys” was a miss. He was even a coxswain at Trinity, and yet with this one sentence, he left out Alenka Doyle, the woman who coxed that boat and was the Intercollegiate Rowing Coaches Association Coxswain of the Year.

I have made that same mistake before, along with talking about the eight athletes in the boat, instead of the nine (just like The Boys in the Boat movie did with the line “We weren’t eight; we were one.” (Poor Bobby Moch, unless he meant to leave out the three seat).

I think Alenka deserves a shout-out to correct this error.

Chris Tolsdorf

Program director, head girls coach Unionville Rowing Club Pocopson, Pa.

Doctor Rowing replies:

You are right, Chris. Thanks for the reminder. Coxswains, be they girls or boys, women or men, are athletes, too. I won’t go as far as to say, “They are the real boat movers,” as many a coxswain believes. But it’s not an eight; it’s a nine.

Independent review of the ActiveSpeed - Sander Roosendaal, founder of the rowing analytics site rowsandall.com, takes a deep dive into the ActiveSpeed. Radley

Large Configurable Display (2, 4 and 6 fields)

Optional Wireless Impeller & Accessories

Easy Data Transfer via the DataFlow App

$445 $495

Another Golden Four

The U.S. men’s under-23 four of Ryan Martin, Wilson Morton, Sam Sullivan, and Lyle Donovan replicated the U.S. Olympic four’s gold medal, leading start to finish, at the World Rowing Under 23 Championships in Trakai, Lithuania.

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY

Dartmouth College freshman Cosmo Hondrogen won a silver medal in the lightweight varsity at the 2025 IRA National Championships and then switched back to sculling to win another silver at the 2025 World Rowing Under 23 Championships in the lightweight single in Trakai, Lithuania.

Silver Streak

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY

FOCUS ON THE FINISH LINE WE’LL TAKE CARE OF THE REST!

Planning your next regatta? Nathan Benderson Park makes it easy. Seamless booking and complete logistical support means you can concentrate on the competition, not the complications.

BENEFITS OF BOOKING AT NBP

Permanent, Purpose-Built World-Class Rowing Venue

Ample Trailer Parking with Easy In and Out, 1 Mile from I-75

Course Setup & Management by On-site Professional Staff

Premier Safety & Emergency Services Coordination

550-Acre Park with 400-Acre Lake

Plenty of Tent & Vendor Space and Unobstructed Course Views

Parking & Traffic Flow, Course Maps, Practice Schedule

Location: 5 Miles from Airport. Walking Distance to Hundreds of Shops and Restaurants in a Safe Neighborhood. Minutes Away from the World’s Best Beaches

PLAN YOUR REGATTA!

NathanBendersonPark.org

NATHAN BENDERSON PARK

5851 Nathan Benderson Circle, Sarasota, FL

QUICK CATCHES

North American Crews Win Medals at World Rowing Age-Group Championships

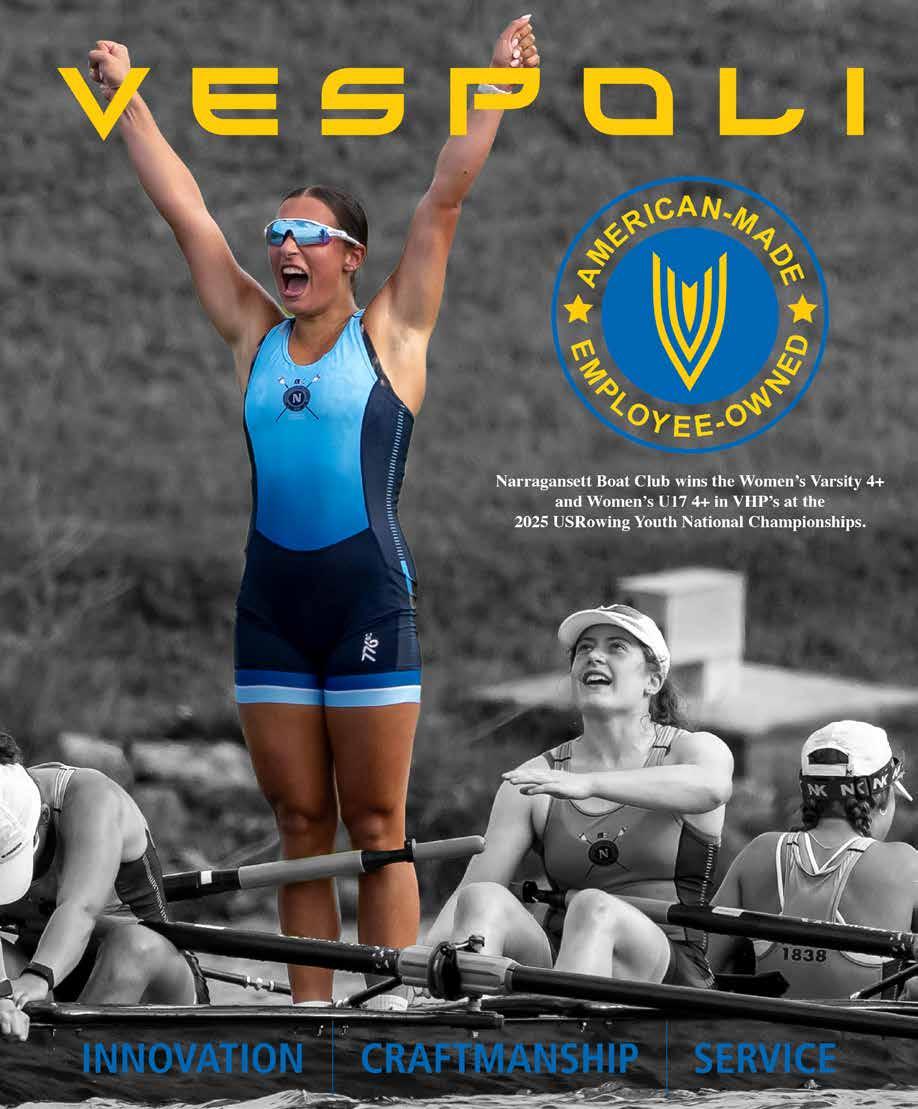

U.S. crews won three U19 medals and two at the U23 worlds, led by gold-medal performances by the women’s U19 four and men’s U23 four.

North American crews won medals racing against the world’s best agegroup rowers at the 2025 World Rowing under-23 and under-19 championship regattas this summer.

Canada’s Ciana Della Siega and Novella Rusman won bronze in the women’s

U19 pair, while their compatriots also won bronze in the women’s U23 eight.

U.S. crews won three U19 medals and two at the U23 worlds, led by gold-medal performances by the women’s U19 four and men’s U23 four.

Records Set at North Tahoe

Over 100 competitors took to the flat water—”at least flat for Tahoe, there were some boat wakes”—to race the Short Course, Long Course, and Ultra Long Course, in early August in Tahoe Vista, Calif. A total of 13 course records were set in coastal and flat-water boat classes. Youth entries tripled from the previous year, and team-points trophies were awarded for the first time. Blair Island Aquatic Center won the masters trophy, and Redwood Scullers won the youth trophy.

The U.S. women’s U19 four won gold at the 2025 World Rowing Under 19 Championships.

QUICK CATCHES

British oarsmen ruled the water in Trakai, Lithuania, winning all three men’s sweep events—pair, four, and eight—at the World Rowing Under 19 Championships, August 6 to 10, after winning both eights and topping the medal table at the World Rowing Under 23 Championships in Poznan, Poland, July 23 to 27.

The age-group regattas bring together the world’s best under-19 and under-23 rowers to compete for their countries and to develop as international athletes. Most Olympic champions race at one or the other or both of World Rowing’s junior (U19) and pre-elite (U23) championships at some point in their careers, leading up to glory at the Games.

2025 World Rowing Under 19 Championships

The U.S. women’s U19 four of Claire Van Praagh, Lauren Dubois, Lia Nathan, and Teagan Farley won gold for the first time for the U.S. since 2018 at the 2025 World Rowing Under 19 Championships.

“What it took to get here was more than just the four of us,” Van Praagh said afterward on the awards dock. “It was our coaches at USRowing, it was our coaches at home—shout out to Sidwell Friends, Deerfield, Groton School, and RowAmerica

Rye—they pushed us to be great, they pushed us to get here. It hasn’t been just one summer of work to get here; it’s been years of work.”

Van Praagh’s boatmates echoed her gratitude, mentioning their appreciation for their families, their communities, and their teammates in the quad, the eight, and alternates for pushing them to be great.

The win was the second U19 gold medal for Van Praagh, Dubois, and Nathan, who won in the U.S. women’s under-19 eight in St. Catharines, Ontario, when the event was held on the Canadian Henley course last year. Nathan and Van Praagh will continue as teammates next year as members of the Class of 2029 at Stanford University.

The U.S. women’s under-19 eight raced through the field in the final to win silver after finding themselves in last place in a tightly packed dramatic final. The crew of Stefania McMasters, Kathryn Dahl, Alexis Gormley, Eden Alfi, Zara Taylor, Ana Ciechanover, Caitlin Cecere, Madeline Glover, and coxswain Avery Harries-Jones worked its way up to third place going into the final 500 and then passed Australia to finish second behind Great Britain.

The U.S. men’s four finished fourth, and Tony Madigan finished fifth overall, in the men’s single sculls. The men’s eight finished eighth.

Romania is no stranger to a women’s final at any international championship, and the U19 worlds was no exception. Teodora Lehaci and Denisa Mihaela Vasilica impressed throughout the regatta and won gold in the final that included the Canadian bronze U19 pair. The U.S. did not have an entry.

Greek junior sculler Varvara Lykomitrou continued her impressive international career with more golds. Having won European and world U19 gold in the double scull last year, she mixed it up this season and has now become European and world U19 champion in the single scull as well as world U23 champion in the double scull.

Coached by Giovanni Postglione, Lykomitrou was second to Spanish sculler Esther Fuerte Chacon for the first half of the final but made her move in the second half, crossing the finish line with a an open-water margin.

2025 World Rowing Under 23 Championships

Great Britain ended the 2025 World Rowing Under 23 Championships on top of the medal table after defending both its men’s and women’s eights titles, and adding women’s quadruple sculls gold to the women’s four title. Under-23 rowers in 239 crews from 53 nations competed in Poznan,

BIG NEWS >>>

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY.

This year’s silver marks the 19th-straight medal for the U.S. in the women’s U23 eight, which has earned a spot on the podium in every year of the regatta.

Poland, from July 23 to 27.

The U.S. men’s under-23 four of Ryan Martin, Wilson Morton, Sam Sullivan, and Lyle Donovan won gold, leading from start to finish. The win in the U23 event was a first for the U.S.

“I had so much trust in these guys to execute their race,” said Sergio Espinoza, coach of the four. “They did everything we asked of them, and it paid off. I’m just so proud of them and all of our coaches. Huge thank-you to Josy Verdonkschot, Casey Galvanek, Jesse Foglia, and Brett Gorman for all their work and support; it has made a major impact.”

Dartmouth College freshman Cosmo Hondrogen, fresh off of a silver-medal performance in the varsity lightweight eight at the IRA national championship, won silver at U23 worlds.

Hondrogen captained Oakland Strokes as a youth oarsman, winning silver at the 2023 USRowing Youth National Championships, and earning a spot on the 2023 U.S. Junior National Team.

The men’s U23 eights field featured 14 countries, the biggest field in the regatta’s history, and the kind of full field World Rowing would like to have in the Olympic regatta (which will require doubling up by rowers—as the Romanian women did so successfully in Paris—because of the cap of 438 athletes set by the IOC).

Despite the novel field size, the result was the same as it’s been since 2018, with the British men’s U23 eight winning for the sixth straight year. The U.S. men’s U23 finished fifth in the A final, more than seven seconds behind Great Britain. Canada came in sixth in the B final.

Great Britain, with its deep well-funded and -organized national-team system, also defended its U23 title in the women’s eight in a field of 10 countries.

Coached by Texas alumna and current associate head coach Gia Doonan, the U.S. crew of coxswain Honor Warburg, Joely Cherniss, Áine Ley, Ella Wheeler, Natalie Hoefer, Kathryn Serra, Annica Ford, Taryn Kooyers, and Maeve Heneghan won silver for the second year in a row.

The Canadian crew of Mira Calder, Maylie Valiquette, Ellexi Fulton, Annika Goodwyn, Janette Peachey, Isobel Campbell, Cait Whittard, Gabriella Worobec, and Victoria Grieder, won bronze.

This year’s silver marks the 19thstraight medal for the U.S. in the women’s U23 eight, which has earned a spot on the podium in every year of the regatta. The under-23 championships replaced the Nations’ Cup regatta for pre-elite rowers in 2002 and became an official World Rowing championship in 2005 (no event was held in 2020 because of Covid).

During that stretch, the U.S. National

Team senior/Olympic eight achieved its 11-year undefeated streak of Olympic, world-championship, and World Cup gold medals (2006 to 2016) and also experienced its current losing streak of no world-championship wins and no Olympic medals of any color since 2019. Canada’s women’s eight won gold at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics in 2021 and silver at the 2024 Paris Games.

“It has been great watching this crew come together over the last few weeks,” said Katie Bahain-Steenman, coach of the Canadian women’s under-23 eight.

“Some of these women met each other for the first time less than eight weeks ago and are leaving here with friendships that I expect will last a lifetime. The crew was supportive of one another and ready to race when we got to race day. They grew throughout the week of competition and put their best race out there for the final race.”

Para rowing made its U23 debut at this year’s championships, marking the first time in history that an international underage regatta included events for Para rowers.

Next year’s World Rowing Under 23 Championships are scheduled for the last weekend in July in Duisburg, Germany.

The U.S. women’s under-19 eight raced through the field in the final to win silver.

QUICK CATCHES

Community Rowing, Inc.’s Simeon John.

PHOTO: CONNOR SCHAFER.

Rowers Flock to Canadian Henley for Summer Climax

Before Covid, the popular regatta opened up more spaces to junior crews to meet demand. Now the regatta needs to find room in its packed schedule for more senior events.

The 141st Royal Canadian Henley Regatta returned to pre-Covid levels of popularity this year with over 2,000 entries from 129 clubs.

“It’s good to see that we’re back,” said regatta chair Peter Scott. “We had some fantastic weather. We were cranking them out every six minutes. We can put three on the course at a time.”

The regatta needed that capacity, and more, as the North American rowing community flocked to St. Catharines, Ont. for the culminating experience of summer racing on Martindale Pond.

Rowing Canada composite crews took first and second place in the Brock University 25th Anniversary Trophy race for women’s championship eights.

“It was a good experience for our squad,” said Canadian National Team head coach for women, Tom Morris, “one we hope to continue into the future seasons.”

California Rowing Club won the

Craig Swayze Memorial Trophy for men’s senior eights, ahead of a composite crew of Canadian athletes, a pair of Wisconsin high-performance eights, and Greenwich Crew. Canadian Henley continues to attract increasing numbers of big American clubs and high-performance camps.

Before Covid, the regatta opened up more spaces to junior crews to meet demand, Scott said, and now the regatta needs to find room in its already packed six-day schedule for increased demand for senior events.

There were “quite a bit of boats on the waitlist,” Scott said, including eight for the under-23 men’s eights.

The regatta can run about 100 races a day, but going from three heats advancing to the final to adding a fourth heat requires two semifinals to set the final, something the regatta couldn’t make work this year.

“A storm changes everything, and it’s taxing on the volunteers to race after 6

p.m.,” Scott said. “We have a solid, steady volunteer group coming back every year. It’s a reunion, one big happy family—really nice to see smiles everywhere.

“We’re proposing a bunch of changes for next year—not sure how many will go through,” said Scott, who mentioned the demotion of lightweight rowing and the introduction of mixed rowing on the international level as trends for the regatta to watch. “We’ll have a discussion over the winter.”

Community Rowing, Inc.’s Simeon John hauled away lots of silverware by racking up three wins: the Anthony ‘Tony’ Novotny Trophy for men’s under-19 singles; the Dave Cornelius Memorial Trophy for the men’s lightweight single dash; and the R.G. ‘Bob’ Dibble Memorial Cup for men’s 64-kilogram singles. John then faced the other way to cox the CRI entry to fourth place in the men’s eight dash.

Notre Dame, St Catherines Rowing Club, Buffalo Rowing Club, and OKC Riversport line up .for the second heat of the men’s U23 lightweight four at Canadian Henley.

The Business of College Sports Spins the Coaching Carousel

At St. Joseph’s University, reduced rowing support led men’s head coach Mike Irwin to leave for the Naval Academy and women’s head coach Gerry Quinlan to go to Fordham.

The coaching carousel spun over the summer as the continuing impact of the rapidly changing business of college sports led several rowing coaches to switch jobs.

Not changing is Wisconsin, where the five-year agreements of men’s head coach Beau Hoopman and women’s coach Vicky Optiz were extended through May 2030.

Negative effects of the changing college-sports environment included St. Joseph’s University’s losing both men’s head coach Mike Irwin and women’s head coach Gerry Quinlan, as the university makes broad budget cuts in the wake of school consolidation.

The university purchased the University of the Sciences in 2022 and Pennsylvania College of Health Sciences in 2023 to expand nursing programs and incurred significant debt. As a result, cuts have been made across the university, and despite having already endured recent budget reductions, St. Joe’s rowing programs learned last spring of more cuts to come.

In the women’s program, the number of annual scholarships was reduced from four ort five to just one. Other reductions in rowing support led men’s head coach Mike Irwin to accept a coaching position at the United States Naval Academy and women’s head coach Gerry Quinlan, who led the near doubling of the men’s and women’s programs over 26 years, to become head women’s coach at Fordham.

Quinlan said he’s going somewhere willing to maintain investments in rowing, picking up a team with good support, and working for an athletic director who wants to win. Although he feels bad for the young team at St. Joe’s, he didn’t want to be complicit in how the university is treating rowing, he said.

Of his new position, also in the Atlantic 10 Conference, he said, “I’m excited to see where Fordham can go. The support is great, and the kids seem really motivated.”

Despite heading opposite directions on Interstate 95 this fall, Quinlan and Irwin plan to continue to run the Navy Day Regatta together.

Another Atlantic 10 program, The University of Dayton, found a new women’s rowing head coach in Adam Herrick, who

with the hiring of Mara Allen as a head coach two years ago, and now by Kansas with the hiring of Andy Derrick

Neither Allen nor Derrick was looking to leave their roles at successful programs when their new schools came knocking. Allen had been a key member of NCAAwinning staffs at Cal and Texas before UCF hired her away with an opportunity she couldn’t pass up, despite being pregnant and having to move halfway across the country.

Last spring, her UCF program swept the finals of the Big 12 championship at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota, which UCF uses as a sort of second home course. The championship is the first outright Big 12 title in UCF athletics history. As this issue went to press, Terry Mohajir, UCF’s director of athletics, announced a two-year extension of Allen’s contract through the 2030 season.

“I’m excited to see where Fordham can go. The support is great, and the kids seem really motivated.”

—Gerry Quinlan

joins the Flyers for the 2025-26 school year from Three Rivers Rowing Association in Pittsburgh, where he was also the head coach of Carnegie Mellon University Rowing, a club sport. From 2015 to 2020, Herrick was the head coach of West Virginia University men’s crew, also a club program.

The St. Joe’s situation is different from the changes affecting athletic administrations run as businesses. For some rowing programs, the changes have been beneficial, since a more professional approach to athletics can result in attractive compensation for head coaches, expansion of scholarships for rowers, and the allocation of more resources to rowing.

In the Big 12, one of the “big four” football conferences, the opportunity to be nationally competitive in an NCAA championship sport for relatively little money (the top 10 college football coaches are paid over $10 million; the top college rowing coach makes $300,000) was seized first by the University of Central Florida

“I am very excited for the future of UCF Rowing and UCF athletics,” Allen said. “I’m very thankful to Terry for this opportunity. We have a lot of work ahead of us, but I truly believe in what is possible here.”

Relatively new Kansas athletic director Travis Goff also believes in what is possible at his Big 12 school and has hired six new head coaches—including for both football and rowing—in his first four years on the job.

Derrick, who has made a career of establishing a new team culture and improving results at each program he’s led, wasn’t looking for his next job while coaching Gonzaga to four appearances at the last five NCAA Division I championships, despite having only 10 of the then-possible 20 full scholarships to offer.

The Kansas search committee called Derrick to see who might be available as Goff sought to improve the Jayhawks’ rowing results. As they described plans for the program, they caught Derrick’s interest, and before he knew it, he was on campus for a second visit and getting ready to accept an offer that would require moving across the country within weeks.

When he told Kansas he hadn’t actually applied for the job yet, the response was: “That’s not how we find head coaches.”

QUICK CATCHES

A Rowing Coach and a Gentleman

A new biography highlights the character of Joe Burk, whose life straddles 60 years of American rowing and who was admired for his integrity, modesty, fairness, and work ethic.

Ask anyone who has read The Boys in the Boat what crew came in second to the University of Washington in the 1936 Olympic trials and typically they have no clue.

Even if the reader is from Philadelphia. The answer is the University of Pennsylvania, and rowing in that eightoared shell was Joe Burk. He also came in second in the single sculls.

With his dream of competing in the 1936 “Hitler Olympics” dashed, Joe Burk persevered. He corresponded with boatbuilder George Pocock in Seattle about technique. He trained by himself on a creek near his New Jersey home to sustain a punishing rate of 40 strokes per minute.

And he became the greatest American single sculler–racing handily toward the 1940 Olympics.

When those Games were canceled, he turned his drive and determination to battle and became a war hero. Then, for two decades, he coached crew at Penn, fostering one champion after the other.

Still, few know Joe Burk’s story.

Ed Woodhouse, whose own rowing career came within a few degrees of separation from Burk’s, has just finished the first comprehensive biography of Burk—Joe Burk: An American Ideal , now available through Amazon.

“I started thinking about all of the coaches that I’d known,” said Woodhouse,

who rowed at Harvard. “And I realized that my Harvard coach, Harry Parker, was really a product of Joe Burk. And Joe Burk was in turn a product of Rusty Callow and George Pocock. And George Pocock plugs right into the great English watermen, the early scullers.

“And that got me thinking: This guy sits astride 60 years of American rowing in the 20th century.”

Also compelling to Woodhouse was Burk’s integrity, his sense of fairness, and his work ethic–character traits that resonate in the country today.

“I thought, here’s an honorable man, literally the American ideal. He was a throwback to a time when the idea of coaches was not that they were winning football games. It was that they were creating character in the athletes they coached.”

Woodhouse rowed at Kent School and then at Harvard, where his undefeated freshman eight, coached by Harry Parker, won the Thames Challenge Cup in 1974 at Henley Royal Regatta. His crew was written up by Sports Illustrated , which called it the “Rude and Smooth.”

At 6-foot-2 and 183 pounds, Woodhouse was the smallest of the “big, strong crew” that included Al Shealy, Rick Cashin, and Tiff Wood. Those men continued rowing and winning medals. Woodhouse, whose father had just died, went to law school instead.

“While I was hoping to continue to try to make the national team, I realized I had to just get on with it.”

After earning his degree at the University of Virginia, Woodhouse devoted his career to practicing law. Always haunting him, however, were the words of a Harvard section leader who graded a biography he wrote for class.

“What do you plan to do after graduation?” he had asked Woodhouse. “I said, ‘Well, I’m going to law school.’ And he said, ‘God, don’t do that. You ought to be a writer.’”

Three years ago, Woodhouse, 72, began researching Burk. While he read every news story he could find about him, the strength of his book is the many interviews with rowers who knew Burk, from Fred Lane, stroke of the 1955 boat that won the Grand Challenge Cup at Henley, to Luther Jones, a Penn freshman under Burk in 1968, the

Joe Burk served in the United States Navy after the 1940 Olympic Games were cancelled.

year before Burk retired.

Woodhouse himself has long known many of these rowers. He also spoke with such champions as Gardner Cadwalader, Reed Kinderman, Ken Drefuss, Howard Greenberg, Gregg Stone, and Lyman Perry.

“I thought, here’s an honorable man, literally the American ideal.”

—Ed Woodhouse

All these men respected Burk, even when his point system worked against them.

“They’re remarkably uniform in their devotion to Burk,” Woodhouse said.

Woodhouse believes that Burk’s use of science to remove bias from his coaching is another reason to call him an “American ideal.” Burk would use a mechanical light system to measure rowers’ leg pressure in the boat and shuffle crews by flipping cards to seat the men for practice races—methods designed to select his racing crew more fairly.

“It’s hard to find truly objective scientific acts that all can agree on, and that makes Burk’s effort that much more admirable,” Woodhouse said. Burk’s use of data for decision-making risked reducing his own authority.

Burk also stands out for never holding a grudge. Woodhouse recounts a 1966 incident between Burk and Harvard coach Harry Parker, whom Burk had mentored a decade before at Penn. Harvard had just trounced Penn on the Schuylkill.

“Ever the gentleman, Burk comes up to Parker, sticks out his hand, and says, ‘Congratulations, Harry.’

“In response, Harry says, ‘Well, that settles scores.’”

The Penn captain who witnessed the scene said his jaw dropped at Parker’s apparent bitterness. But “the old master,” said Woodhouse, “took no offense.“

In researching his book, Woodhouse traveled from his home in Virginia to places that revealed something about Burk’s character. One was the Rancocas Creek, near the farm where Burk grew up and attended a Quaker primary school. The Rancocas is where Burk challenged himself to go ever faster, developing his distinctive and unconventional short, rapid stroke.

“Walking that ground and seeing how it looks, how it flows, all of that was a very important piece of seeing how solitary it was,” Woodhouse said.

The Quaker influence on Burk was also huge—“that sense of modesty, self-effacement, evenness of temper, regardless of circumstance,” Reed Kinderman observed.

Another pilgrimage was to the remote rustic cabin that Burk and his wife built by hand in Montana after he retired

from Penn. In traveling there, he followed the route–from the Spokane airport through Idaho to winding Wyoming roads near the Canadian border–that so many of Burk’s protegés also took to visit him until he died in 2008 at 93.

“I kept wondering, What was Joe doing finding that place, since he’d spent most of his life on the East Coast? And what I finally concluded was he was coming back West to the land of Rusty Callow and lumberjacks, to the land of George Pocock. I think it was, in a way, his spiritual homage to those two mentors.”

DOTTY BROWN is the author of Boathouse Row, Waves of Change in the Birthplace of American Rowing, which includes a chapter on Joe Burk. She pointed Ed Woodhouse to Philadelphia resources for his book

REVENGE OF THE LIGHTWEIGHTS

SHUNNED

BY

THE OLYMPICS AND WORLD ROWING, ROWERS OF “NORMAL SIZE” ARE POSTING SENSATIONAL TIMES, RACING TO EXCITING FINISHES, AND OCCASIONALLY BEATING THE BIG BOYS.

STORY BY ANDY ANDERSON

PHOTOS BY LISA WORTHY

Quick! Which crew had the fastest time in the finals at this year’s Intercollegiate Rowing Association regatta? You wouldn’t be wrong if you said Harvard. But the Harvard heavies finished second to Washington, the winners of the varsity eight race.

My friends, you are looking at the wrong Harvard crew. It was the Harvard lightweights who raced the 2,000 meters in a course record of 5:29.62.

The Harvard heavies were also very fast, but they finished in 5:30.75. And Washington, the heavyweight national champions, were 5:29.78, a whisker behind the lights.

Lightweights with the fastest time? In the A finals, yes.

(It’s only fair to point out that the California heavyweights, who missed the A finals with a crab near the end of their semifinal in atrocious conditions, made up for it the next day in the B finals by flying down the course in a time of 5:24.04. In fact, five of the crews in the heavyweight B finals went under 5:29.)

Are the times between the heavyweight and lightweight finals comparable? Can lightweights beat heavyweights?

No, not at the top levels. At virtually all colleges, the squads compete in practice, and although lightweights might take a piece or two throughout the season, on race day, they are faster only rarely.

Despite getting booted from the Olympics and suffering chronic financial, administrative, and admission malnourishment, lightweight rowing continues to thrive—even beating heavyweights in time (IRA, Harvard) and place (Henley Diamonds, Finn Hamill)— and provide exciting, fast racing for normalsize people.

In 1974, when FISA, the predecessor of World Rowing, introduced lightweight men’s events in its championship program, it was to create fair racing opportunities for men under 72.5 kilograms (159.8 pounds) because of the competitive advantage of size in rowing, which is akin to the athletic advantage of males over females.

It was also an acknowledgment that many of the world’s countries could not field oarsmen as tall and heavy as the men who were filling the openweight events. Lightweight rowing, which began at the University of Pennsylvania in 1917, attracted athletes of more normal dimensions.

Women’s lightweights were added

to the FISA program in 1984 for women under 59 kg (130 lbs). The exhibition events in Montreal that year were the first time women raced the “men’s distance” of 2,000 meters in international competition. Before 1984, it was believed the longer distance was too strenuous for women. Similar attitudes had kept track events for women to no longer than 1,500 meters. That same year, Joan Benoit from Maine disproved that belief, winning the first Olympic marathon for women.

In 1996, after an international campaign to add lightweight events to the Olympics, the men’s and women’s doubles and the men’s coxless four were included.

In the eight Olympics that included lightweights, the men’s and women’s events featured some fantastic racing. The London Olympics of 2012 were acclaimed because of South Africa’s triumph in the men’s coxless four—the first, and still only, gold medal won by an African nation in Olympic rowing.

Top-level rowing was spreading to new continents—just as the Olympic movement had hoped. At the world championships, athletes from Turkey, Chile, Japan, Portugal, Guatemala, and Mexico began pushing for medals. Rowing’s appeal was growing, even if at the Olympic level the South Africans remained unique.

Yet after the 2016 Rio Olympics, for the sake of gender parity, the men’s light coxless four was axed from the Olympic program and replaced by the open women’s coxless four. Result: Seats for lightweight athletes fell from eight to four.

Then, in March, the International Olympic Committee and World Rowing seemingly drove another nail into the coffin when they decided there will be no lightweight events at the 2028 Olympics.

Even before that decision, rowing federations had stopped supporting lightweights, focusing instead on events that were in the Olympics.

The men’s lightweight eight was last contested in 2015. The legendary Italian lightweight eights, which won 13 gold medals and seven straight from 1985 to 1991 and were an inspiration to all rowers, were now ancient history.

With this year’s decision eliminating the possibility of winning Olympic medals, virtually all countries rolled back their support for lightweights, even at worldchampionship regattas.

I first paid attention to collegiate rowing when I was in high school. In that era, there was a widely circulated rumor that Steve Gladstone’s Harvard lightweights could beat Harry Parker’s Harvard heavies.

The 1971 lightweight crew was dubbed “The Superboat,” and they showed their speed by winning all their races, including a victory over heavyweight Kingston Rowing Club in the Thames Challenge Cup at Henley.

Was the rumor true? I’ve heard it told both ways, but there’s no question that these crews were very competitive. It doesn’t happen often, but there are occasions, like at this summer’s Henley, when lightweights can beat heavyweights.

Just because, once in a blue moon, lightweights can defeat heavies doesn’t justify their exclusion, however. World Rowing posted a piece on its website celebrating “the mental toughness propelling former lightweights to openweight success.”

That’s a weak justification for the decision to get rid of lightweights. Just because a few have made a successful move to openweights doesn’t mean it was the right thing to do. What about all those who’ve been left behind?

I worry that young rowers who are still growing will look around and conclude that rowing is a sport for really big people only. Smaller, average-sized athletes may be discouraged from even trying rowing—the sport that teaches so many lessons and offers so many rewards.

The Harvard lightweights who dazzled at this year’s IRAs clearly benefited from a strong tailwind, which one coach described as “close to detrimental in that it whipped up the water into a furious boil.”

Nevertheless, this year’s Harvard crew was unworldly. They won the Goldthwait (HYP) Cup, the Eastern Sprints, the IRA, and capped it off by winning the Temple Challenge Cup at Henley, beating Oxford Brookes, a crew that had seemed invincible. In the 2024 Temple finals, Brookes had vanquished previously undefeated Harvard in the semifinals, the crew’s only loss that year.

How did the Harvard lightweights climb to the top of the podium? They’re a unified, hardworking team and a very strong group of guys, coach Billy Boyce said. The boat’s average 2K erg time: 6:14–with two studs under 6:10. That’s real power for men who must balance the scale at 155 pounds on race day.

As is the case with so many top college crews these days, it was an international boat—two oarsmen from the UK, two from California, one each from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Canada. At Henley, the South African switched out for a Brit. The coxswain, Anya Cheng, was from Boston. (Delicious footnote: Anya had to race her sister, who was coxing the UVA men in the quarterfinals. Sister seat race!)

It isn’t just Harvard that has internationals filling its lightweight boats. Dartmouth, second at the IRA, had two oarsmen who came to the States to study and row at an Ivy League college. The Big Green had a Brit and a U23 Norwegian. But Dartmouth also had two Californians— stroke Ryan Tripp, who raced in the U23 lightweight double in 2023, and Cosmo Hondrogen, who returned from Poznan, Poland, in July with a silver medal in the U23 single.

“How did they race?” I asked Boyce, about Harvard.

Their strength and the source of their speed, he said, was the transition from the high strokes to the base. They didn’t take more than 25 high strokes at the start, they got up to speed in that 25, and then just kept it going.

“It seemed like we would almost go faster when we shifted the rate down; the splits would often show that. In the minute after shifting, we would usually take a length. We don’t plan big moves, because with a planned move, there’s a natural tendency to wait for it and then take your foot off the gas afterward. Our mantra was ‘Go fast and keep going fast.’”

Their racing at Henley (available on YouTube) followed that pattern. They had tough races against two Dutch crews, Aegir and Nereus, and when they would draw level at the Barrier (about 650 meters), they would keep going.

“When we nosed ahead of Brookes at the Barrier, I knew we were going to win.”

But no 2,112-meter race is ever easy. They were pushed the whole way. The margin at the finish line for both the semifinal and the final was less than a length.

Only once has lightweight rowing had a threepeat at the IRA, when Cornell won in 2006, ’07, and ’08. With a boat that had only one senior oarsman and a senior coxswain, Harvard will be gunning for a third consecutive title. But you can be sure there are other rising programs that will push hard to take the Crimson down.

Beginning this year, the men’s and women’s lightweight pairs and quads have been dropped from the world championships.

Great Britain’s superb crew of Emily Craig and Imogen Grant missed a bronze at Tokyo by one-hundredth of a second. Their return three years later at Paris to win gold by 1.72 seconds was one of the great stories from the Olympic rowing venue. The loss of the lightweight doubles means that races like the women’s double in Tokyo, where the first five women’s crews were within a second, are finis.

“Henley is our world stage,” Boyce said. Without lightweight events at the Olympics, competing for the Temple Cup is as close as lightweight athletes can get to showing their speed on a big stage.

Coach Trevor Michelson of Dartmouth echoes this, noting that the Eastern Sprints league is virtually all that is left for lightweight athletes. The upside, if you want to call it that, is that if you are a lightweight-sized person, the Sprints colleges are it. That results in their boats getting faster and faster. It’s the premier venue for lightweight rowing in the world.

How to explain these improvements in boat speed?

Coach Michelson points to erg scores getting better. The usual reasons for how athletic performance keeps improving—better equipment, training methods, nutrition, and data analysis via telemetry—have been boosted by another factor: Freshmen are allowed to row varsity. Kids take gap years. They are older and have trained more.

“What that really means is that the JVs are going to be faster. They are much closer to varsity boats than they used to be, pushing varsity boats harder in practice. The times for JV crews bear that out.”

Michelson observes that none of the 2025 IRA lightweight varsity-medal winners—Harvard, Dartmouth, and M.I.T.—even qualified for the IRA in 2022.

“In the lightweight world, there is more emphasis on development and teaching. It’s not all about recruiting. Look how rarely a heavyweight program moves from the bottom to the top of the league. Compare that with lightweights. There’s a lot more movement up the ranks.”

Perhaps the biggest shocker from this

year’s Henley Royal Regatta was that a former lightweight from New Zealand, Finn Hamill, beat Olli Zeidler, the reigning Olympic champion in the single, in the semifinals of the Diamond Sculls.

If you watch the race on YouTube, you’ll see that the German blasts off from the start and takes what looks like a commanding two-length lead at the Barrier, the way he does in all the big races.

But Hamill never gave up and drew even with the four-time winner of the Diamonds in front of the Enclosures, and then passed him to win by a length.

Hamill is no rookie, and it’s clear from watching him race that he’s not intimidated by being behind. He obviously has a tremendous motor that just doesn’t slow down. There was rough water in his race with Zeidler, but Hamill handled it well, as befits someone who, last September, won the 4K coastal men’s single event. Hamill was not intimidated by the 6-foot-8 German, having beaten the Dutch Olympic bronze medalist Simon Van Dorp the day before.

I asked Finn about being a lightweight and racing against heavyweights.

“I’ve always lined up against people much bigger than me, so I have had to work very hard on technical aspects. I used to grab with my shoulders at the catch; I’ve worked hard to be more relaxed.”

He has done just that. Perhaps because he is also a coastal-rowing champion who knows how to stay calm when the water is roiling, you can see that he doesn’t let bad water bother him.

Of his race against Zeidler, he said: “I knew I’d be well off his pace in the first half of the race. I could tell that he had shot out, but then he stopped moving. I couldn’t believe that I was right with him. And then when I raised the rate to 41, I didn’t need to turn my head to see him; I was there. And then I was moving past him, just trying to keep it going.”

For his part, Zeidler posted on Instagram that after taking 11 months off after the Olympics he was not disappointed in his racing.

“Two wins and then a defeat reflect an honest result,” he said. “It’s utopian to think you can just show up and win without proper months-long preparation.”

Even in defeat in the finals the next day against another Dutch sculler, Melvin Twellaar, Hamill kept pushing

the rating up and moving back in the second half of the race. Moreover, all his terrific performances in the single came despite also racing in the double sculls, an event that he and his partner, Ben Mason, 6-foot-2 and 210 pounds, won. How would you like to face an Olympic medalist in your second race of the day?

Hamill, who rows at Waikato Rowing Club on the North Island, follows a training program different from that of most other Kiwis.

“I probably have the least amount of volume during the racing season. I do a lot of high-intensity.”

At Henley, there are no weigh-ins and no lightweight events. Lightweights relish the opportunity to race with full bellies. Hamill was “about 175.” The last time he rowed as a lightweight was 2023, when he won a silver medal in the lightweight single at the world championships.

“Before the Rio Olympics, New Zealand had a very good lightweight program, the best of which was a coxless four, but once the Olympics dropped the event, Rowing New Zealand did, too.

“It was only because of the efforts of Matt Dunham that lightweight rowing was kept alive in New Zealand through to Paris. In the end, RowingNZ wouldn’t select a crew to race in 2024, which ended my dream of racing the lightweight double at the Olympics.

“With lightweight now becoming a thing of the past for Olympic rowing, we have to step up against the bigger guys. I was very sad to see lightweight events go. They were such competitive events.

“I love all rowing and boats—sailing, coastal rowing, even Beach Sprints. My goal is to compete at the LA Games. My doubles partner and I will trial in August for the world championships.”

Will we see him at the 2025 worlds in the double?

The affable 23-year-old has a lot of rowing ahead of him. He won the Head of the Charles and the Head of the Schuylkill championship singles events and loved those races. He’ll be back in the U.S. this October.

Don’t bet against this former lightweight.

ANDY ANDERSON, a.k.a. Doctor Rowing, has been coxing, coaching, and sculling for 55 years. When not writing, coaching, or thinking about rowing, he teaches at Groton School and considers the fact that all three of his children rowed and coxed—and none played lacrosse—his single greatest success.

Fast and Furious

The whole lightweight league has gotten faster in the past five years. Until this year, the IRA course record was 5:33. Take a look at these swift performances.

The Eastern Sprints records:

2007 Dartmouth—5:38.9. This held up for a long time.

2023 Princeton—5:35.4

2024 Harvard (in heat one)—5:34.7

2024 Penn (in heat two)—5:34.2 (and Princeton—5:34.9)

The 2007 record held for 16 years and then in two years, the course record was broken three times by four crews by almost five seconds.

The IRA records:

2012 Harvard—5:33.06

2025 Harvard—5:29.62 (Dartmouth—5:32.25)

The 2012 lightweights record held for 13 years and then got broken by 3.44 seconds by Harvard and 0.8 of a second by Dartmouth.

The Lake Carnegie records:

2018 Princeton—5:35

2024 Yale and Navy—5:34.3 and 5:34.5

2025 Harvard—5:28.5. Fastest lightweight eight time!

Overall, the league got a lot faster in 2023, then faster again in ’24 and ’25.

THE

INTERVIEW

WYATT ALLEN

HE WAS NAMED COACH OF THE YEAR AFTER DARTMOUTH WENT UNDEFEATED IN THE REGULAR SEASON AND WON SILVER AT EASTERN SPRINTS AND BRONZE AT THE IRA. “THERE IS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR INTERNAL COMPETITION AND THE WAY THAT CAN RAISE THE LEVEL OF PERFORMANCE.”

INTERVIEW BY CHIP DAVIS

Olympic champion Wyatt Allen knows a thing or two about developing rowing potential into rowing victories, having lived the experience as an athlete before becoming a coach.

Allen learned to row in the club program at the University of Virginia, and his prowess earned him the opportunity to row with U.S. National Team aspirants training at the time under Kris Korzeniowski and Mike Teti in Princeton. Soon, he was assigned to the sculling group to mature before being fed into the meat grinder of selection for the eight and four, the priority boats.

He developed so well, as both a sculler and sweep oarsman, that he won the Diamond Challenge Sculls at Henley Royal Regatta in 2005, the year after winning Olympic gold in the U.S. men’s eight, an event in which he won bronze at the 2008 Beijing Games.

Allen’s coaching career began at the University of Washington in the 2008-09 season. There, he was an assistant on the IRA-winning staff, part of UW’s threeboat sweep of the national championship. He then moved down to Berkeley to coach the Cal freshmen under his Olympic coach Mike Teti, and again his crew won the IRA.

After that, more job offers came in,

and Allen took the head coaching job at Dartmouth, a struggling program at the time. “Dartmouth is where good coaches go to become mediocre,” a competitor told him. This year, Allen’s Big Green beat that coach’s varsity multiple times during an undefeated regular season that culminated in the Dartmouth varsity heavyweights’ winning a silver at Eastern Sprints, bronze at the IRA, and advancing to Saturday’s semifinal of the Ladies’ Challenge Plate at Henley Royal Regatta.

For all that and more, Allen was honored by his peers as the 2025 Intercollegiate Rowing Coaches Association Coach of the Year.

Rowing News: You’ve been the head coach of the Dartmouth heavyweight program for 11 years and had some success along the way, but 2025 was your best year yet, after a good but ultimately disappointing year last year. What were the differences this year that led to the undefeated regular season, medals at Sprints and the IRA, and an impressive run at Henley?

Obviously, it starts with having a talented group of guys returning for the year. Last year was a disappointing end for the guys in the 1V, and the returners out of that boat came back this year and responded to the disappointment in just

the way you would hope—by doubling down on their training and approach to this year. We also had a strong core return out of a medaling 2V and a fifth-place 3V, which created a deep competitive group this year.

Senior leadership from guys like Munroe Robinson, Julian Thomas, Miles Hudgins, and Sammy Houdaigui was a huge piece of the year. And then having Billy Bender return from the Olympics and add his leadership and rhythm in stroke seat was critical as well.

Rowing News: You were a big oarsman, winning the Henley Diamonds in the single and Olympic gold in the eight, you run a big program that races five eights, and your varsity this year was a boat of really big oarsmen. What’s the Wyatt Allen “big” approach all about?

I don’t know if there is an actual “big” approach I follow or subscribe to. I do believe in the importance of carrying a big roster in terms of depth and competitiveness. There is no substitute for internal competition and the way that can raise the level of performance for a group. It also helps a program be more consistent year to year.

When I arrived in 2014, it seemed that Dartmouth would have a good recruiting class or two, then the talent

would fall off for a year or two, and then pick up again. We really made an effort to stabilize things and become more consistent, starting with our recruiting, and hopefully leading to our on-the-water performance.

In terms of the physical size of our rowers, it really depends year to year. This year’s 1V crew was tall and physical. I suspect that next year we will be smaller physically. I remember Kevin Sauer at Virginia saying to me as an undergrad that “the oar really doesn’t care how tall you are; it cares only about the force you’re able to generate.” That’s an oversimplification, of course, but it’s stuck with me a long time.

Rowing News: Your former assistant John Graves is now the women’s head coach at Dartmouth and has led a remarkable resurgence of that program. You seem to have a successful working relationship with lightweight coach Trevor Michelson, who just won silver at IRAs. How much does a high-functioning boathouse environment contribute to one squad’s success, and vice versa?

It’s a total cliché, I know, but this year was a perfect example of a “rising tide raises all ships.” It was great to come down to the boathouse each day and see all three programs excited and motivated by the prospects in front of them. And it was special to have the lightweight and

heavyweight 1Vs win medals within a few minutes of each other at the IRA.

On the coaching front, I’ve learned a ton from Trevor and John, and the same is true of the way our coaching staffs work together. They’re all friends and willing to share and work together.

Rowing News: IRA and U.S. National Team watchers complain about the predominance of international recruits in top college crews, but your varsity had six Americans. Are you doing something different than your top competitors, or did it just work out that way?

We’re not doing anything that different from what our competitors are doing. Every year, we go out and recruit the best group we possibly can. For us, that has typically been two or three internationals and the rest domestic, which creates a nice balance to our roster.

Rowing News: What do you wish a younger you knew early in your coaching career?

I would describe myself early in my career as a “more is always better” kind of coach. That came out of coaching freshmen, where you can get away with that. They’re young, durable, and you have them for only one year.

I’ve learned to pace the year better the longer I’ve coached. Don’t get me wrong: I believe you have to train a lot and hard. But by being a little more strategic in how

many times we ask them to go all out in a week, for example, we’ve been able both to get more out of our guys and to make it more sustainable for them over a four-year period.

Rowing News: What do you wish the rowing community knew about what you’re doing at Dartmouth?

Two things, and they’re related. One: sculling. We have a big group of our guys rowing in singles and doubles a big part of the fall, and often in the spring. There’s no better place for small-boat rowing than the Connecticut River in the fall, and we do everything we can to take full advantage of it.

Two: We are proud of the number of guys who are pursuing rowing at the highest level when they graduate. We just had five current or recent grads take part in the U.S. National Team senior camp. It sounds like we may have two athletes selected to this year’s eight. And we’ve had a pretty consistent group of guys training with Mike Teti at California Rowing Club.

The sculling has helped create skills and opportunities for the guys when they graduate, and it’s very cool that these guys have something left in the tank after four years, both in terms of energy and passion for the sport.

NECK BUFF

2-layer neck gaiters will protect you throughout the seasons. Stretchguard fabric with extreme 4-way stretch for optimal comfort. Super soft, silky feel that is lightweight and breathable. 100% performance fabric, washable and reusable.

$20

PERFORMANCE FABRIC SHIRTS

ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

TEAM SALES

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

SWEATPANTS

HOODED SWEATSHIRTS

IRELAND ROWING

CANADA ROWING

AUSTRALIA ROWING GERMANY

TRAINING

A Speed Skater’s Polarized Path to Record-Breaking Success

High performance in sports like rowing requires long sessions of low-intensity training over a long period of time and high-intensity training sessions at or around race pace.

It’s the time of year when coaches are making plans for the new season.

Athletes are returning from summer vacation, sculling camp, or competitions with national teams. Recruits are available for the first time and need to be integrated into the team. Coaches have analyzed past seasons and are considering how to improve.

During the preparatory phase of the new season, repeating the strategies of previous years won’t yield different results or the improvements necessary to stay on top. It’s important to learn from past experience and the approaches of other coaches, not just of rowing but other sports.

Autumn head races are an ideal way to make this preparatory phase exciting and goal-oriented. They also provide an initial indication of how things are going. Since head races are even more aerobic than our typical 2,000-meter sprint distance, it’s essential in practice to focus on volume and low-intensity training.

A few years ago, Ohio State’s crew trained up to 200 kilometers a week in

its highly successful campaign to win several national championships. At the international level, under coach Dick Tonks, New Zealand pushed the limit of what was thought possible through enormous training.

Such training loads require increasing the rowing distance gradually over an extended period. In addition, athletes must have ample time to recover and their health should be monitored carefully to ensure they’re adapting properly.

In my new book, Rowing Science, physiologists Brett Smith of New Zealand and Gunnar Treff of Germany explain the benefits of polarized training.

“Polarized” means that training occurs at two extremes, with the majority conducted at low intensity over long periods, interspersed with high-intensity sessions that match or exceed competition speed.

Nils van der Poel, the former Swedish speed skater who is the current world and Olympic record holder and 2022 Olympic champion at 5,000 and 10,000 meters, has developed a training program that seems

beyond human capability.

“In my last two seasons, I regularly skated 240 laps at 30 seconds weekly,” he stated in describing his regimen.

Translation: He skated 96 kilometers every week at his 10-kilometer race pace— equivalent in rowing to 20 km at worldrecord pace, every week.

Van der Poel’s preparation for this level of endurance exercise included a grueling 16-month aerobic-training phase, during which he spent an average of 33 hours a week cycling, running, and crosscountry skiing. During one of these weeks, his training logs show, he cycled at 260 watts three times for seven hours and at 250 watts two times for six hours.

Van der Poel incorporated recovery periods longer than what we’re accustomed to in rowing. For example, he trained only five days a week during both aerobic and anaerobic training phases and took two days off. In addition, he monitored his health meticulously and extended his rest if his body did not recover sufficiently or he became ill or injured. Afterward, he increased his training to full volume slowly

SPORT SCIENCE

TRAINING

over several days.

Even during the anaerobic training phase when he was skating 48 intervals per day at race pace, he maintained long aerobic sessions. He divided the intervals into two sets of three times eight laps each, with a 30-minute “break” on the stationary bike at 220 watts. After the interval session, he rode for another two and a half to three hours at 200 to 220 watts. Thus, the ratio of highintensity to low-intensity training was 24 minutes to 220 minutes.

What can we learn from van der Poel’s example?

High performance in sports with race times similar to those in rowing requires a solid aerobic base, achieved through long training sessions at low intensity over a long period of time as well as a sufficient number of training sessions at or around race pace.

It’s important to tailor your training to the level of expected competition. Not everyone needs to push the envelope of human performance, but you’re deluding yourself if you think you can skip hard work and achieve outstanding results.

An interesting aspect of van der Poel’s training approach was that during the competition season he limited his training on the ice to skating at race pace. All his endurance training was performed off the ice, and his long recovery sessions after intense intervals were done on a bike.

Van der Poel has stated that he wanted to internalize the skating technique at race pace by repeating the same step sequences during practice that he had to perform during races.

Although rowing is very different, perhaps rowers should consider internalizing specific techniques for racing speed more deeply and doing more basic endurance work in other sports.

To those wondering how van der Poel managed to repeat so many highintensity intervals with body and mind intact, this statement is revealing: “To me, the challenge was not about suffering but finding a way to endure hardships with ease.”

COXING

The Golden Rule of Coxing

Good coxswains make other coxswains look good. Follow that policy and you’ll make the whole team faster— and maybe make a friend or two.

Few things will affect your experience on a team as much as your relationship with your fellow coxswains on the water, and few things can affect your experience and your whole team so positively or negatively.

While it’s unrealistic to think that a group of coxswains in competition with each other will be close friends all the time, it’s important to maintain a friendly and positive working relationship.

I hope you make a lifelong friend (or two or three) in the stern of the boat next to you, but even if you don’t, you can have great practices and a positive relationship on the water.

“The best coxswain groups are the most collaborative. That’s where the learning happens,” said Matt Hanig, assistant coach and recruiting coordinator with MIT women’s openweight crew.

On the water, make sure you communicate effectively. The most important thing to watch is tone. If you snap at a teammate on the water in the heat of the moment, your rowers will react to that. It takes focus away from practice and from what you’re trying to do collectively and puts all eyes instead on your emotional state.

“Because you have a microphone, everyone knows when there is tension or a lack of communication,” Hanig said.

If there’s a moment of potential conflict—say, getting cut off at a turn take a deep breath and focus on solving the problem rather than reacting to it.

There’s a big difference between communicating well and reacting in anger or out of insecurity. In the above example, ask for more room rather than shouting to your teammate that he cut you off.

A golden rule of coxing is that good coxswains make other coxswains look good. If there’s a collision, a clash, or a drill done out of time, your coach often won’t care if it’s your fault or not; she’ll know only that you’re part of a practice that isn’t going as intended. But this doesn’t make you powerless in the situation.

Coordinate with the other coxswain about the timing of drills or about the line you’re going to take before you begin a piece or how much room you need around the turn. Show your boat that you’re in control of the situation, regardless of whether other coxswains are. Some programs have walkie-talkies, some coxswains use hand signals, and some coxswains just shout to each other— whatever you need to establish that you’re on the same page as your teammates.

“The best coxswain groups develop a shorthand to coordinate on the water,” Hanig said.

In a side-by-side practice, make sure you understand the plan and what parts of practice are and aren’t competitive.

VOLKER NOLTE, an internationally recognized expert on the biomechanics of rowing, is the author of Rowing Science, Rowing Faster, and Masters Rowing. He’s a retired professor of biomechanics at the University of Western Ontario, where he coached the men’s rowing team to three Canadian national titles.

“The best time to communicate with another coxswain is when you are spinning and before your coach has given instruction,” said Lizzie Mitchell, associate head coach of Boston University women’s rowing, “so you know where the other boat is pointed, what the other coxswain is doing for steering, and how she is communicating the workout to her boat.

“That way, if the coach needs results or is trying to compare, you are giving the rowers the best opportunity to show their ability by running a clean practice together.”

In this regard, make sure you understand what parts of practice are and aren’t competitive. This is especially relevant on a river with currents or turns that offer definite advantages. Is the coaches’ goal to keep the boats side by side or is the goal to see which boat gets out ahead? Know this, and coxswain harmony will follow.

Everybody loves good side-by-side racing, but you should know when and where that’s appropriate.

“Take a step back and understand that for your boat to go fast you need another boat to go fast next to you,” Mitchell said. “In order to do that, the coxswains need to understand each other.”

Off the water, make sure you treat your fellow coxswains with respect. Don’t engage in trash talk, even if your rowers do. Stay professional and above it. And don’t put your rowers in a difficult position by grilling them on your fellow coxswain’s strengths and weaknesses. Instead, work on internalizing the feedback you get and have confidence in your own strengths.

Best case: You’ll make a fast friend or two as you keep the boats side by side.

“I’ve worked with coxswains who had the 1V and 2V and were best friends,” Hanig said. “They developed their relationship over time and got to where the coxswain who was the best fit for those crews had the boat—and they made the team faster because of it.

“I feel like that’s a great thing to strive for.”

ROBBIE CONSULTING

Helping rowers worldwide get scholarships

Helping high school rowers and families navigate the university recruiting process- Coaches and parent groups reach out to us!

Robbie Consulting will meet your team, coaches and parents at your home club or school. Go to www. robbieconsulting.com to get in touch and schedule a visit www.robbieconsulting.com 1-614-330-2879 • Robbie@robbieconsulting.com

“His assistance was essential to get prepared for such a big step and to get to know the school and team I would compete for.”

rowers - indorowers - coastal rowers open ocean rowers - coxies - coaches race/regatta officials

1,788 members in 45 countries

connecting individuals with member groups - regattas - galleries news - events - forums - rowing club links

today - it’s

HANNAH WOODRUFF is an assistant coach and recruiting coordinator for the Radcliffe heavyweight team. She began rowing at Phillips Exeter Academy, was a coxswain at Wellesley College, and has coached college, high-school, and club crews for over 10 years.

TRAINING

Parsing Those Subtle But Important Differences

Choosing a university is a once-in-a-lifetime decision that in the end may come down to gut feeling—where you believe you’ll thrive both on the water and in the classroom.

Selecting the right university as a student-athlete involves far more than comparing rankings or visiting beautiful campuses. When academics and athletics are on a similar level at your final choices, the decision often comes down to subtle but important differences that can shape your experience significantly.

Practice Schedule and Academic Fit

One of the most overlooked factors is how the rowing program’s schedule aligns with your intended major. Does the team train primarily in the mornings or afternoons? That choice can determine which classes you can take each semester—and whether you can stay on track academically without constant scheduling conflicts.

Internship Opportunities

Some universities and rowing programs encourage internships, while others see them as a distraction. Certain internships may require you to be away from the team during the fall non-traditional season. If career experience is a priority, make sure the coaching staff supports and accommodates that goal.

Coaching Staff Dynamics

During recruiting, your primary contact is often the lead recruiting coach. But don’t overlook the rest of the staff. Do they seem unified and supportive or disconnected? A cohesive coaching team can make a world of difference in your development and daily environment.

Trusting Your Instincts

In the end, many decisions come down to gut feeling—where you believe you’ll thrive both on the water and in the classroom. Having a trusted advisor who works solely in your best interest can make this process far less overwhelming, whether you’re joining a top-tier program, a developing squad, or a competitive club team.

Choosing a university is a once-in-alifetime decision. Take the time to evaluate not just the obvious factors but also the details that will shape your four years—and beyond.

From the Front Lines of Sport Nutrition Research…

…the latest about caffeine, cocoa powder, mouth rinses, alkaline water, supplements, and eating disorders

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) is a professional organization whose 14,000 members are sports medicine doctors, sports dietitians, exercise scientists, sports psychologists, and other health professionals who work with athletic people. ACSM’s annual convention is a hotspot for the latest sport nutrition research. Here are some interesting highlights:

The Female Athlete Triad and its three symptoms—loss of monthly menstrual period (amenorrhea), eating disorder, and stress fracture—were recognized first in 1992. Since then, sports-medicine professionals have educated female athletes that amenorrhea can be a sign of being unhealthy, chronically under-fueled, and at high risk for stress fractures.

Despite educational efforts, the prevalence of eating issues has increased. Prevalence rates vary depending on the sport. An estimated two percent to 25 percent of female athletes have an outright eating disorder; seven percent to 61 percent have disordered eating; 10 percent to 59 percent have irregular menses; two percent to 75 percent have low bone-mineral density, and two percent to 100 percent consume inadequate calories to optimize performance.

These numbers are disturbing. All athletes (male and female alike) who struggle with food and weight should seek guidance from a sports nutritionist so they

ROBBIE TENENBAUM coached at the NCAA level for over 30 years and with the U.S. Junior National Team for eight. He now helps rowers and families navigate the university recruiting process.

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY.

can fuel better, perform better, and reduce their risk of injury.

Consuming too few calories is a problem not just for female athletes. Male athletes also are known to under-eat. In a study with college cross-country runners, 57 percent of the men presented with symptoms of low testosterone, suggestive of having too little energy available to support both exercise and normal body functions.

Physique-focused sports (such as gymnastics, figure skating, dance) and non-physique-focused sports (football,

and one tablespoon of brown sugar or sweetener of your choice in one cup of milk heated in the microwave oven. Drink to a healthful recovery!

A survey of supplement use among college athletes showed—no surprise— that those who took the most supplements perceived them to be safe and effective. Not always the case. Look on the label for NSF Certified, USP Verified, or Informed Choice.

All athletes (male and female alike) who struggle with food and weight should seek guidance from a sports nutritionist so they can fuel better, perform better, and reduce their risk of injury

rugby, hockey) showed a similar prevalence of disordered eating, a study revealed. Even power athletes had signs of being poorly fueled. Please notice your brain chatter that suggests food is fattening and reframe the thought to food is fuel, fundamental for enhancing performance.

Deep-colored red, blue, and purple fruits (purple grapes, black currants, blueberries) are rich in anti-inflammatory polyphenols called anthocyanins. These bioactive compounds can impact athletic performance positively. For example, a female endurance runner who consumed a high dose (420 milligrams) of black currant anthocyanins for a week had substantially lower lactic-acid levels after completing a one-hour run. Other research supports positive performance benefits from anthocyanins. Enjoy a lot of deeply colored fruits and veggies.

Cocoa powder is another good source of health-protective polyphenols called catechins. Cocoa powder can be added easily to (sweetened) milk for a recovery beverage.

To make cocoa into chocolate milk, dissolve one tablespoon of cocoa powder

Seventy-two percent of male and female athletes from a variety of sports took some form of sport supplement, with caffeine being the most popular, a survey reported. Athletes get (expensive) supplement information commonly from social media. A sport dietitian can help you find less costly alternatives to highpriced commercial brands at a grocery store.

An enticing blend of supplements containing ashwagandha, arjuna, rhodiola, beetroot, and cayenne showed no benefits (compared to placebo) for CrossFit athletes. What sounds good can be a waste of money.

Swishing a carbohydrate mouth rinse is a strategy known to improve endurance performance. Carbohydrate activates receptors in the mouth that stimulate reward centers in the brain, making exercise seem easier. Mouth rinses can be bothersome to carry during exercise, and the act of rinsing the mouth disrupts normal breathing. Preliminary research suggests carb-containing strips that dissolve in the mouth can do the same job as a mouth rinse, resulting in a faster eight-mile time trial, compared to a rinse with just plain water. Carbs feed both brains and muscles.

Eating before and during a round of golf helps maintain normal blood glucose, which reduces mental and physical fatigue, thereby helping golfers play better. All athletes should plan ahead to make sure the right foods are in the right place at the right times.

High-school runners assume they will improve as freshmen in college. Not always the case. The average 800-meter run time of the top 50 high-school seniors improved about 0.45 seconds during freshman year. Only 51 percent of the runners ran faster. Statistics from 2013 to 2016 show three of the four high-school graduating classes averaged slower times. Could sports nutrition education change this trend?

Caffeine is known to enhance cycling performance, but it’s unclear whether it can help simultaneously with a strength test—and what would be the best dose. Subjects consumed a beverage with no caffeine (decaf coffee), a moderate dose of caffeine (220 milligrams), or a high dose (450 milligrams). (Starbuck’s 16-ounce Grande has about 300 milligrams of caffeine.)

The high dose contributed to better performance for both aerobic and anaerobic exercise. Each athlete has differing sensitivities to caffeine, so learn the dose that works best for you. More is not always better.

Habitual coffee drinkers who enjoy a moderate dose of caffeine are able to maintain normal hydration levels. Caffeine is not as dehydrating as once thought. Both moderately caffeinated beverages and water have similar hydration properties. Not so beverages that are highly caffeinated.

Alkaline water is probably no better for athletes than plain water. Following 10 hours with no food or water (to induce under-hydration), subjects drank 500 milliliters of either alkaline or regular water and performed intense exercise one hour later.