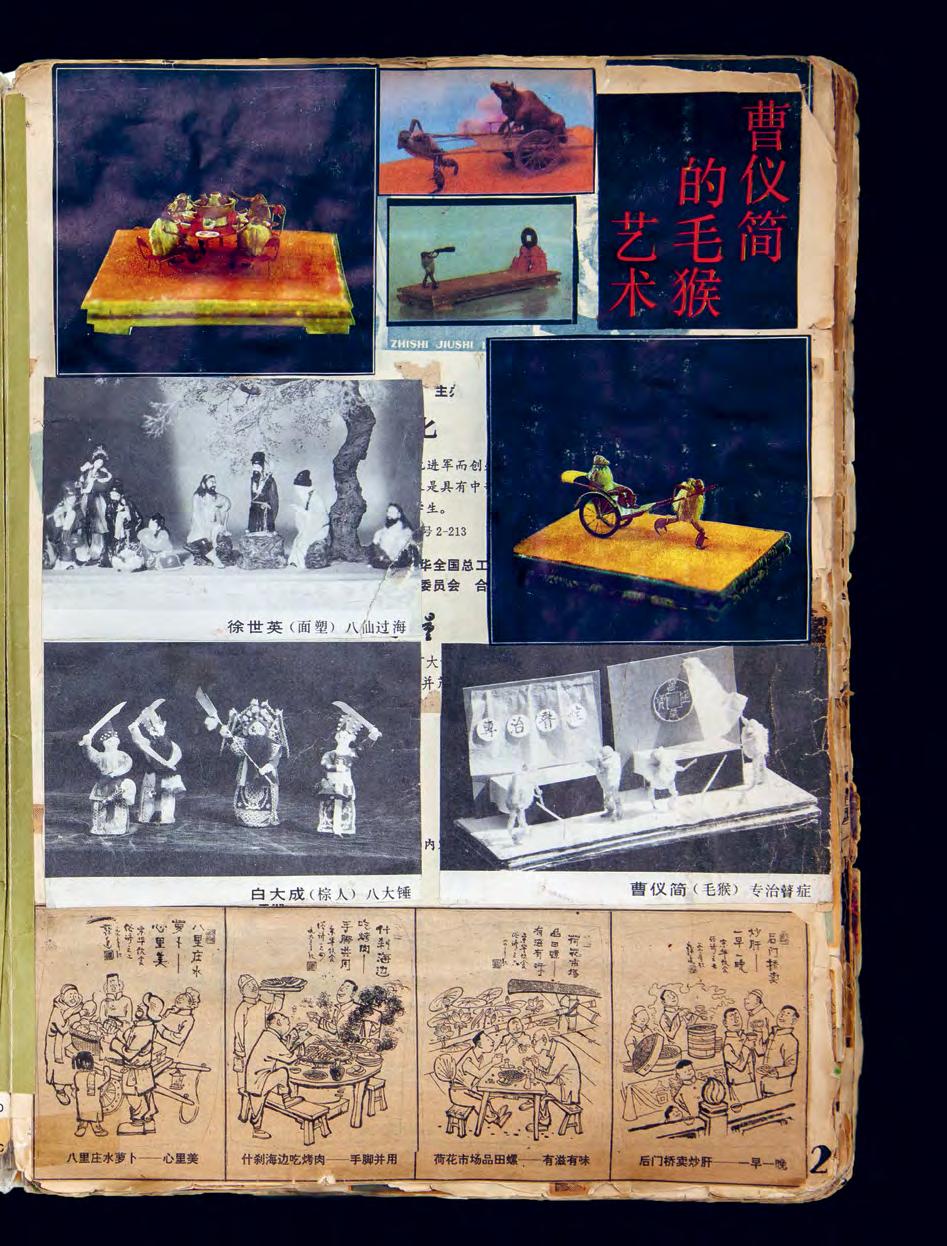

The Art of the Hairy Monkey

毛猴的艺术

毛猴的艺术

Rediscovering Beijing’s Máohóu Tradition Through the Work of Master Qiu Yísheng and the Photography of Simon Wald-Lasowski

在邱贻生大师的作品与西蒙·瓦尔德-拉索夫斯基的摄影中 重访北京毛猴传统

A half-inch monkey greets the capital, With lifelike craft, it mirrors folk and rite. In subtle plainness, new meanings rise, Two humble herbs outshine the finest gem.

— Hu Jieqing (Beijing, 1905–2001)

半寸猢狲献京都, 惟妙惟肖绘习俗。

——胡絜青 (北京,1905–2001)

Dear Reader,

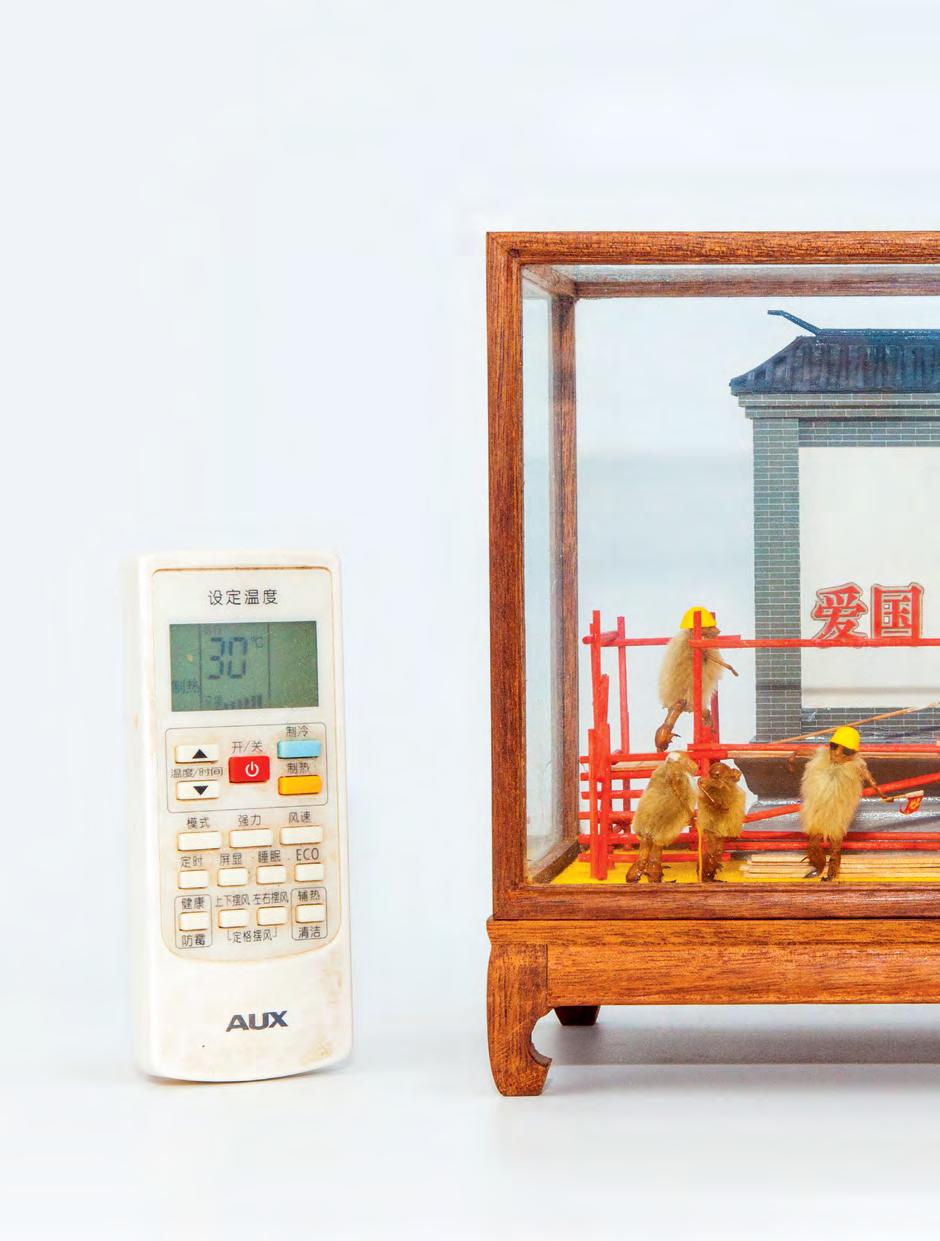

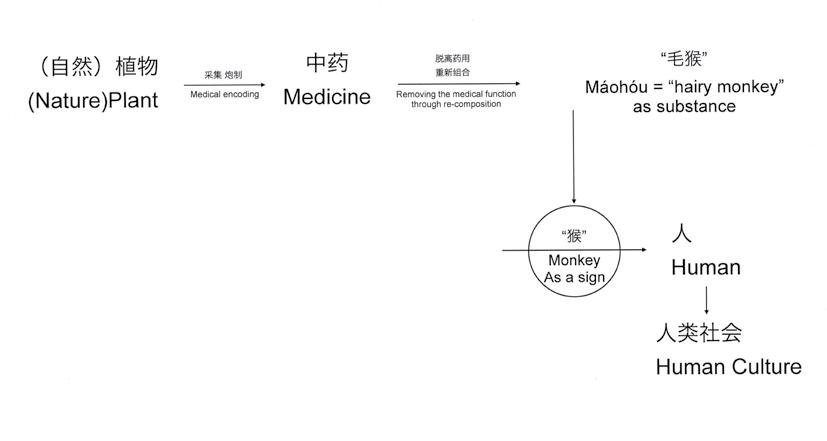

This publication emerged from a desire to share, archive, celebrate and recontextualise the work of the Chinese master Qiu Yísheng 邱贻生 , 1 an artist practicing the intriguing art of máohóu 毛猴 , with “máo 毛” meaning “hair” or “fur” and “hóu 猴 ” meaning “monkey”.

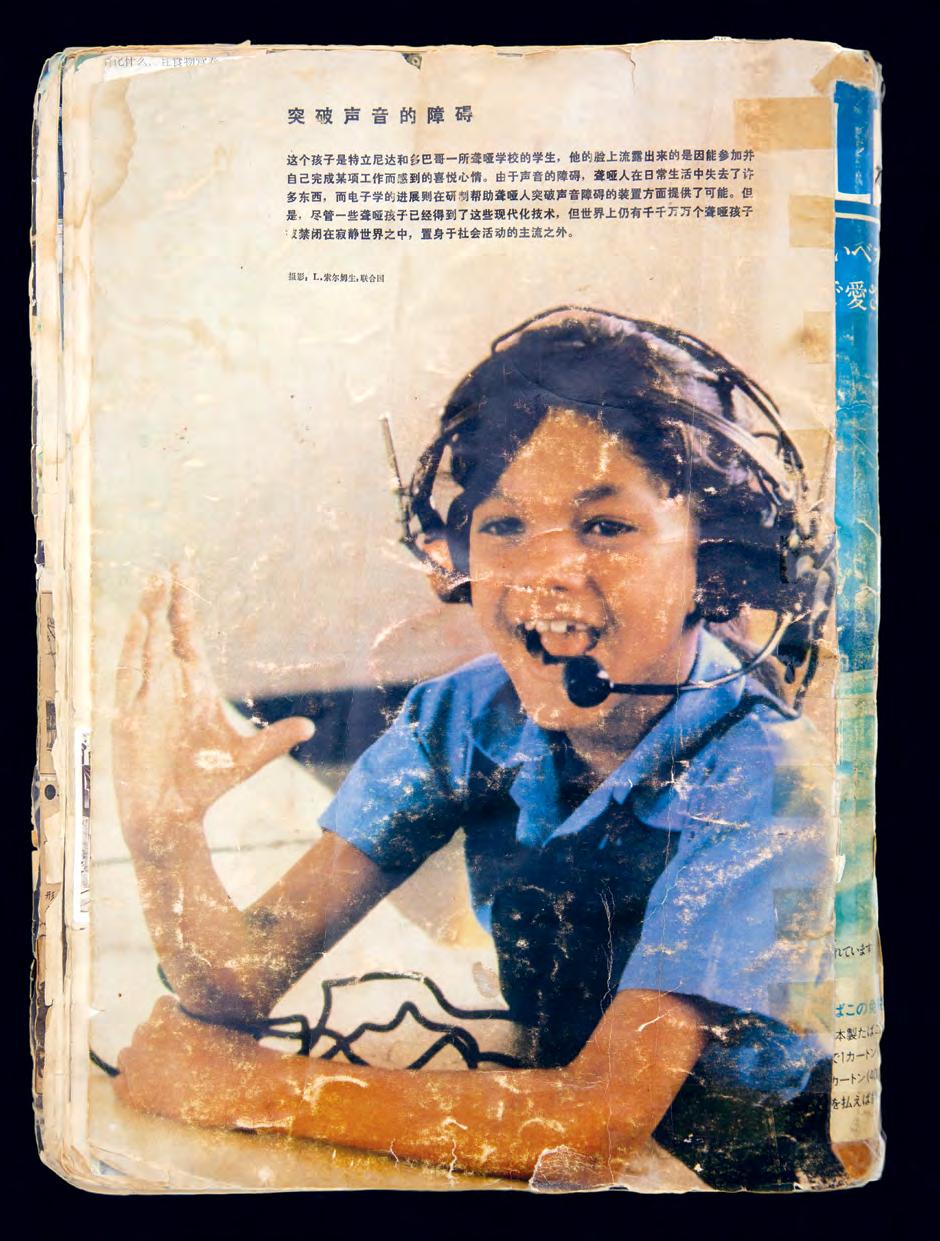

The “hairy monkey” tradition is a meticulous miniature folk art form that originated between 1820 and 1850 in Beijing. In 2009, máohóu as an art practice was added to the list of Beijing’s intangible cultural heritage, yet it remains a relatively obscure practice, unknown to many Beijing locals, let alone international audiences.

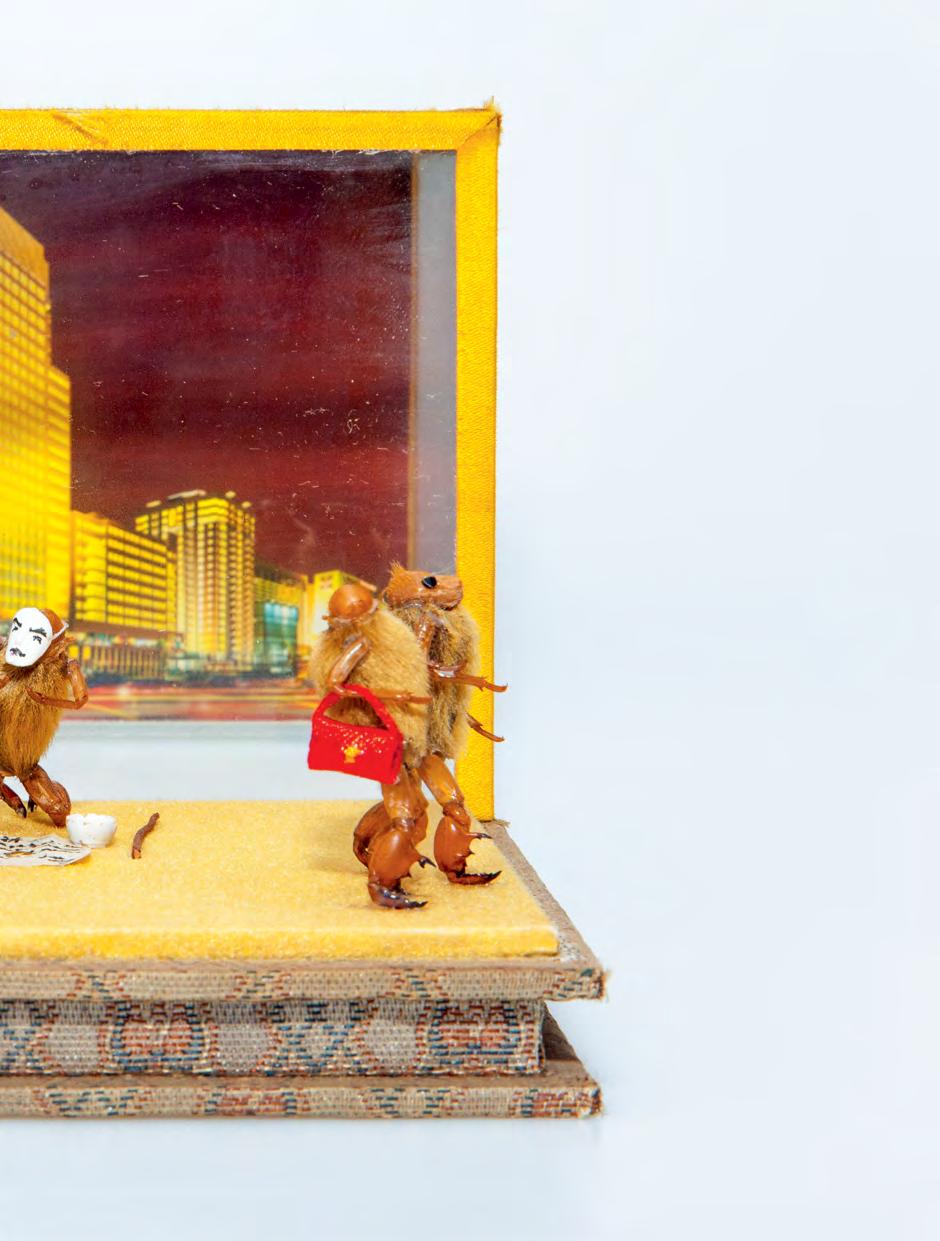

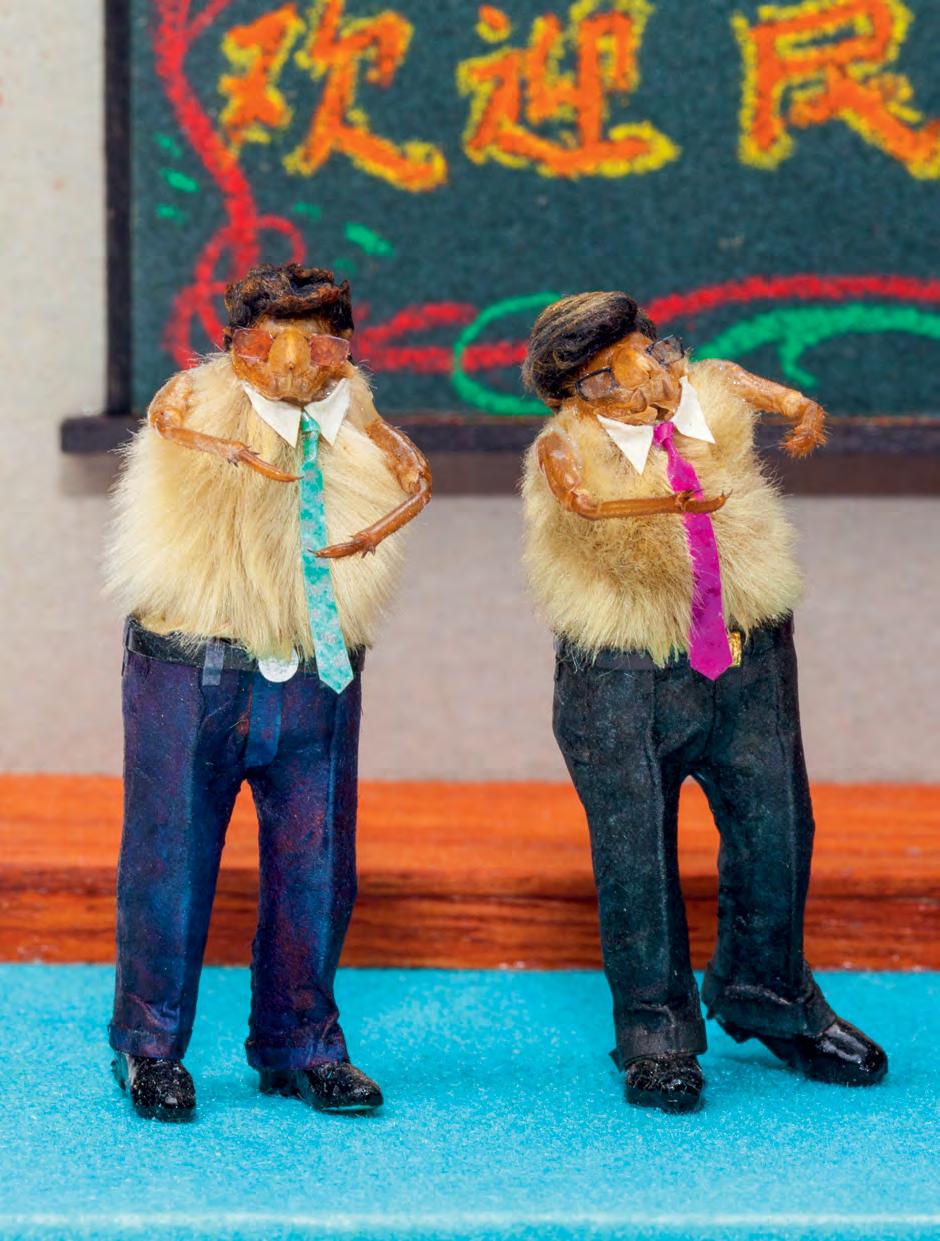

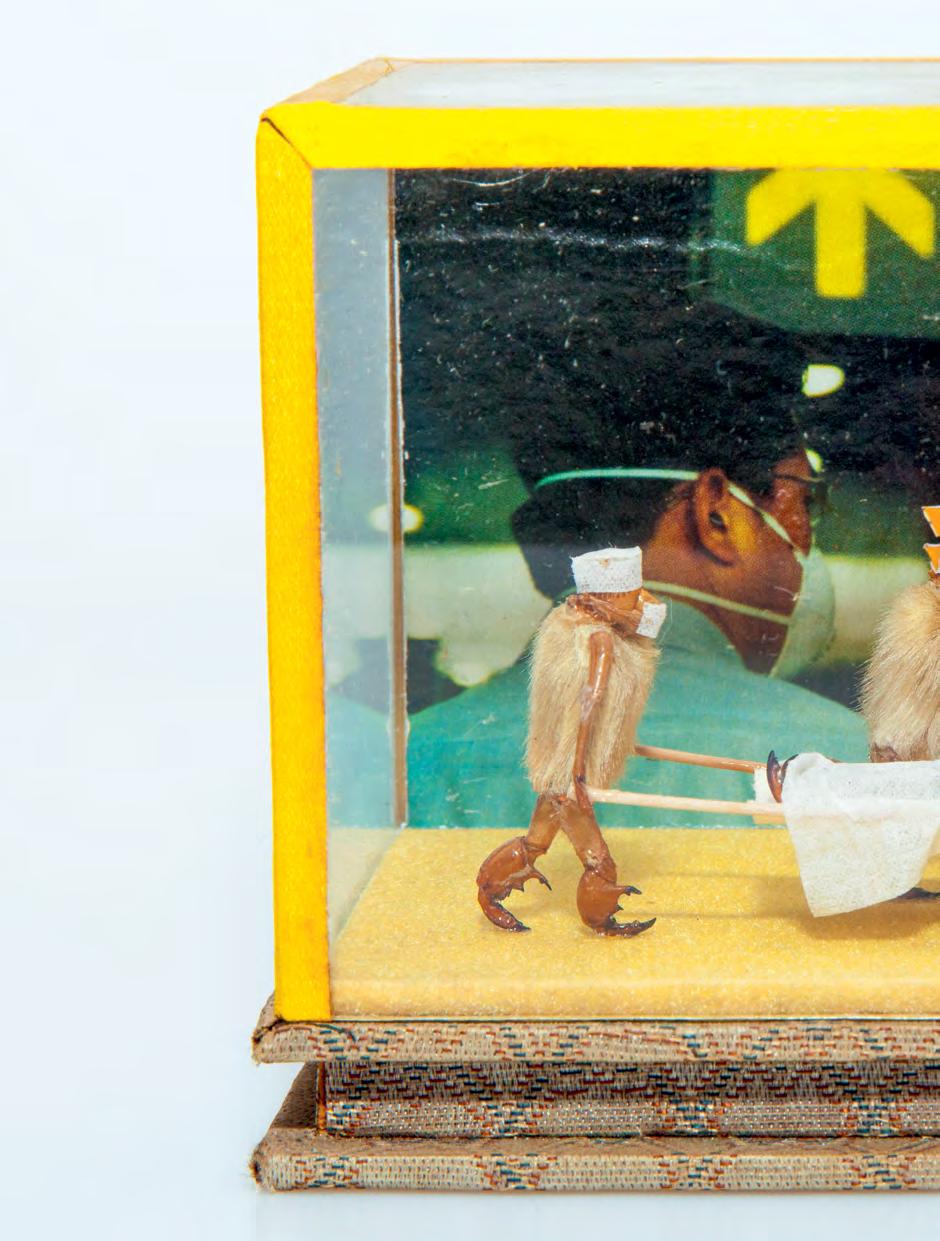

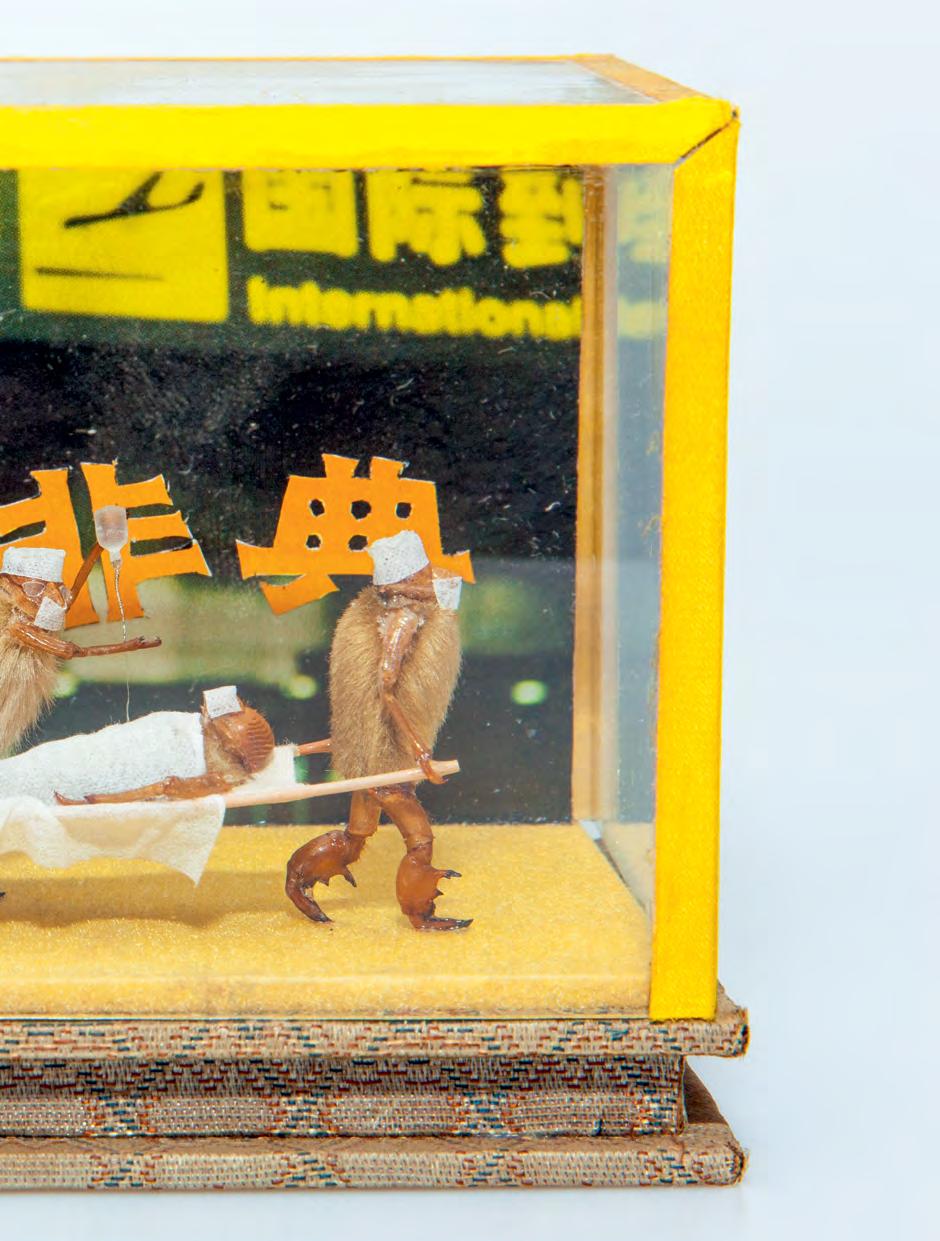

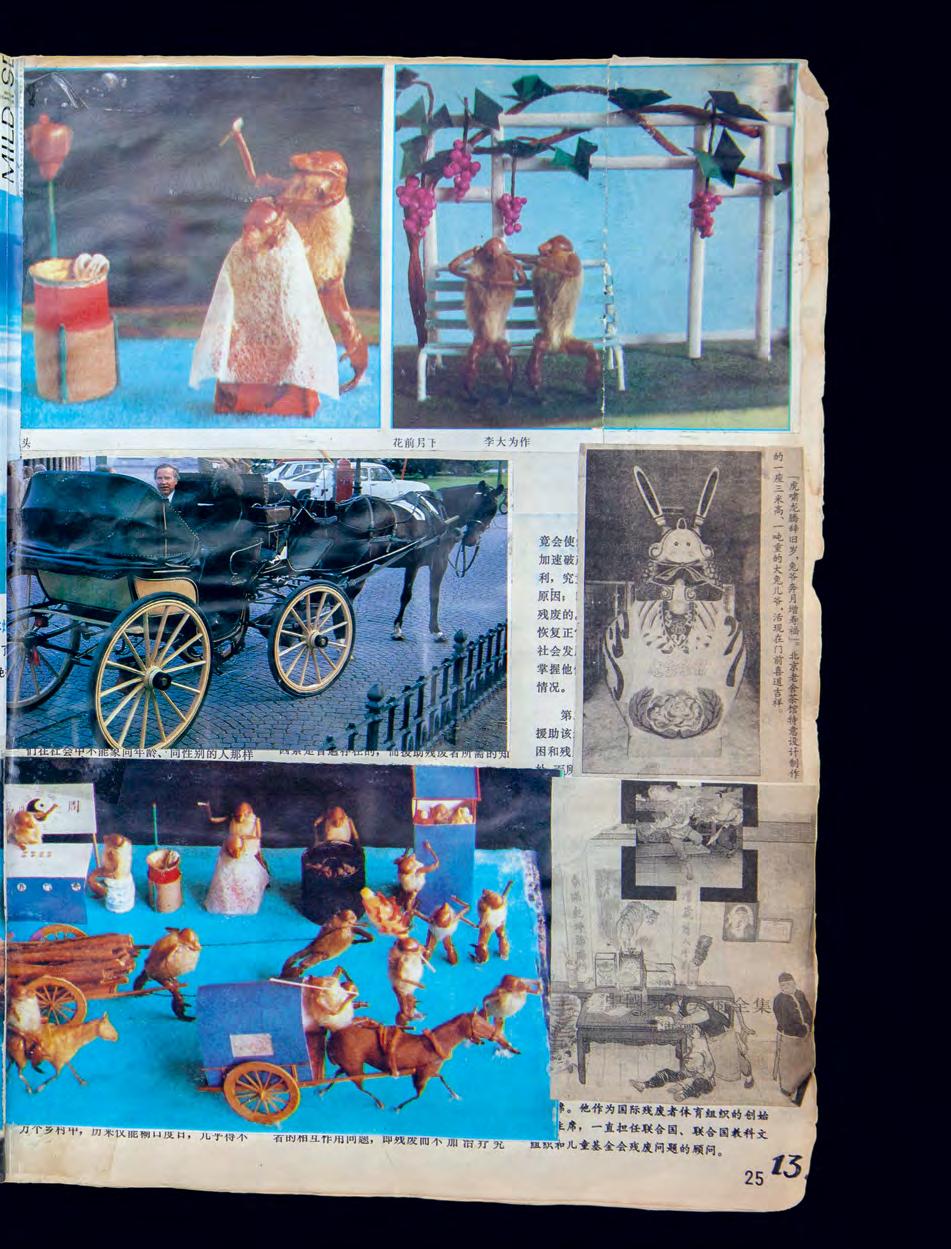

Máohóu are anthropomorphic insect figures measuring approximately four centimetres in height. They are primarily made from cicada shells and the fluffy winter buds of magnolia flowers, both raw materials used in traditional Chinese medicine. The first máohóu monkey was created by a herbal medicine apprentice as a caricature of his employer; more about its origins later. Therefore, in essence, this fascinating folk art form carries a playful and subversive spirit.

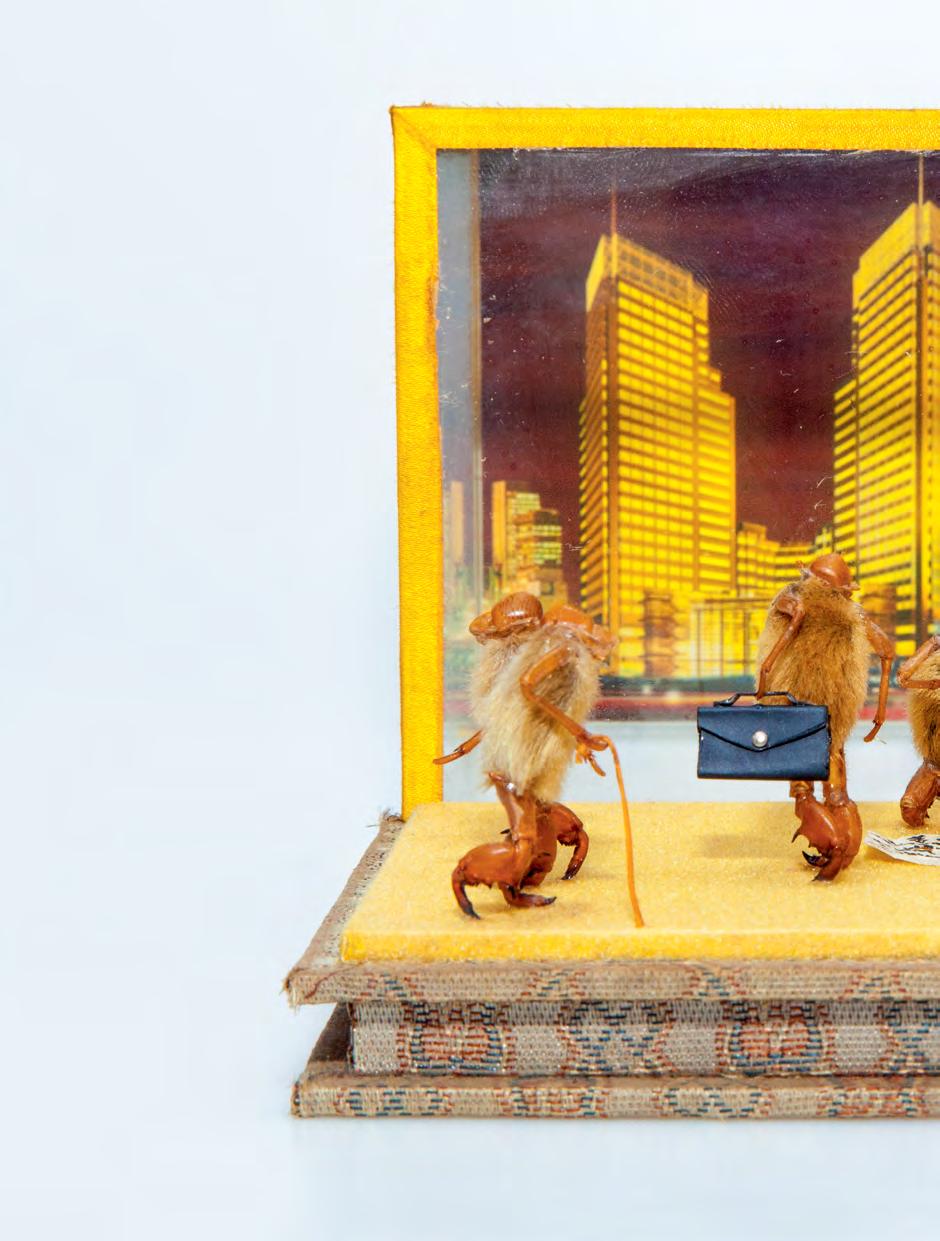

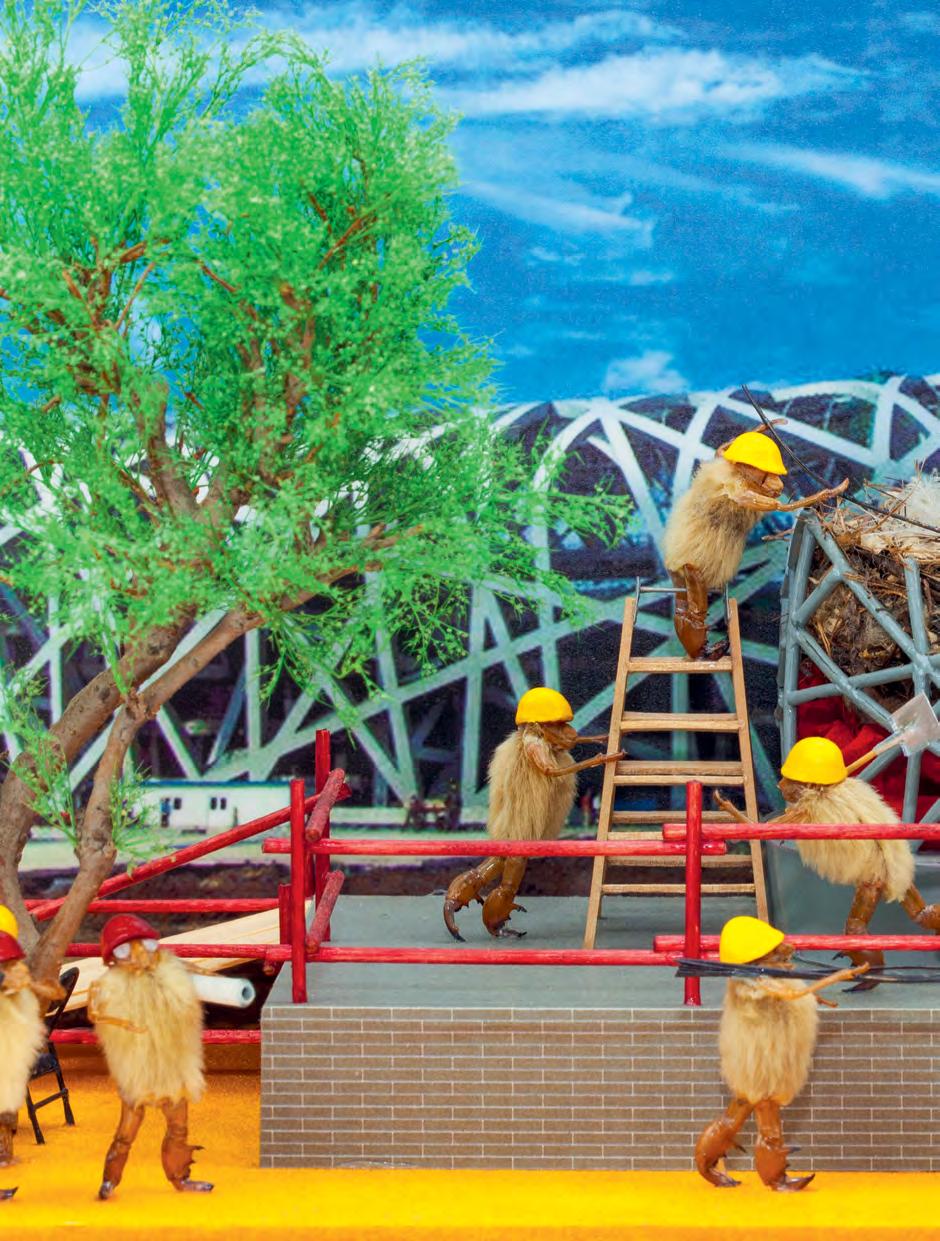

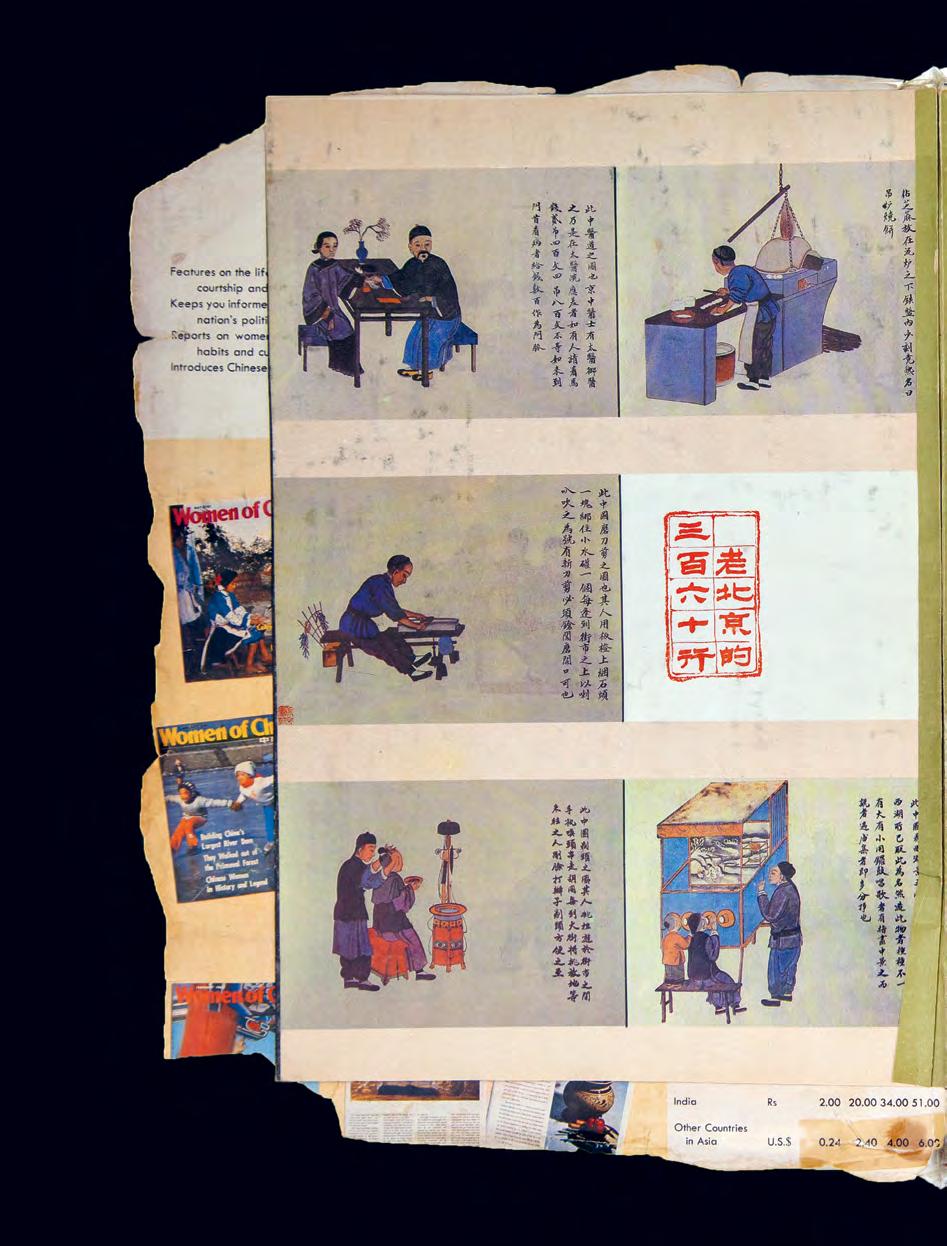

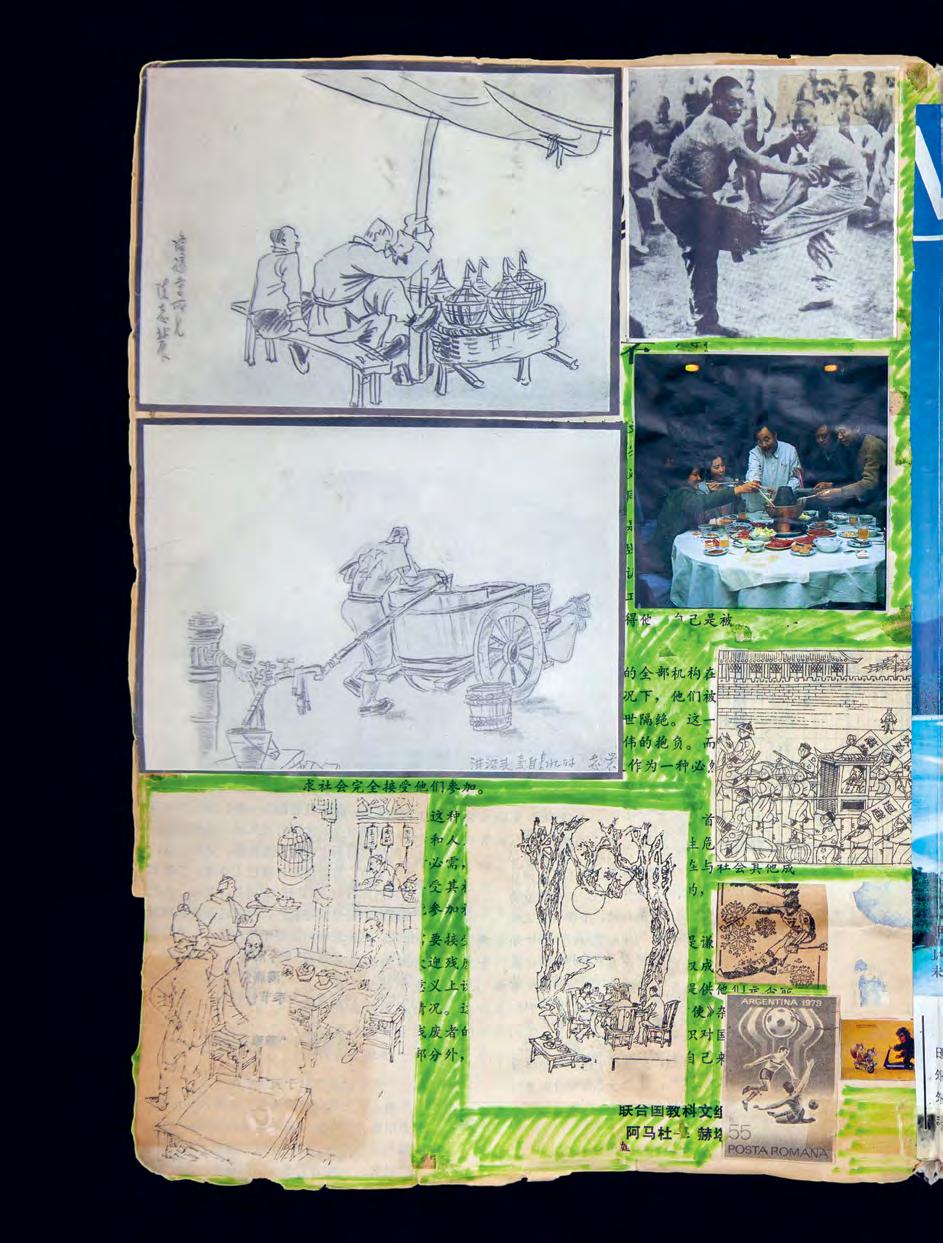

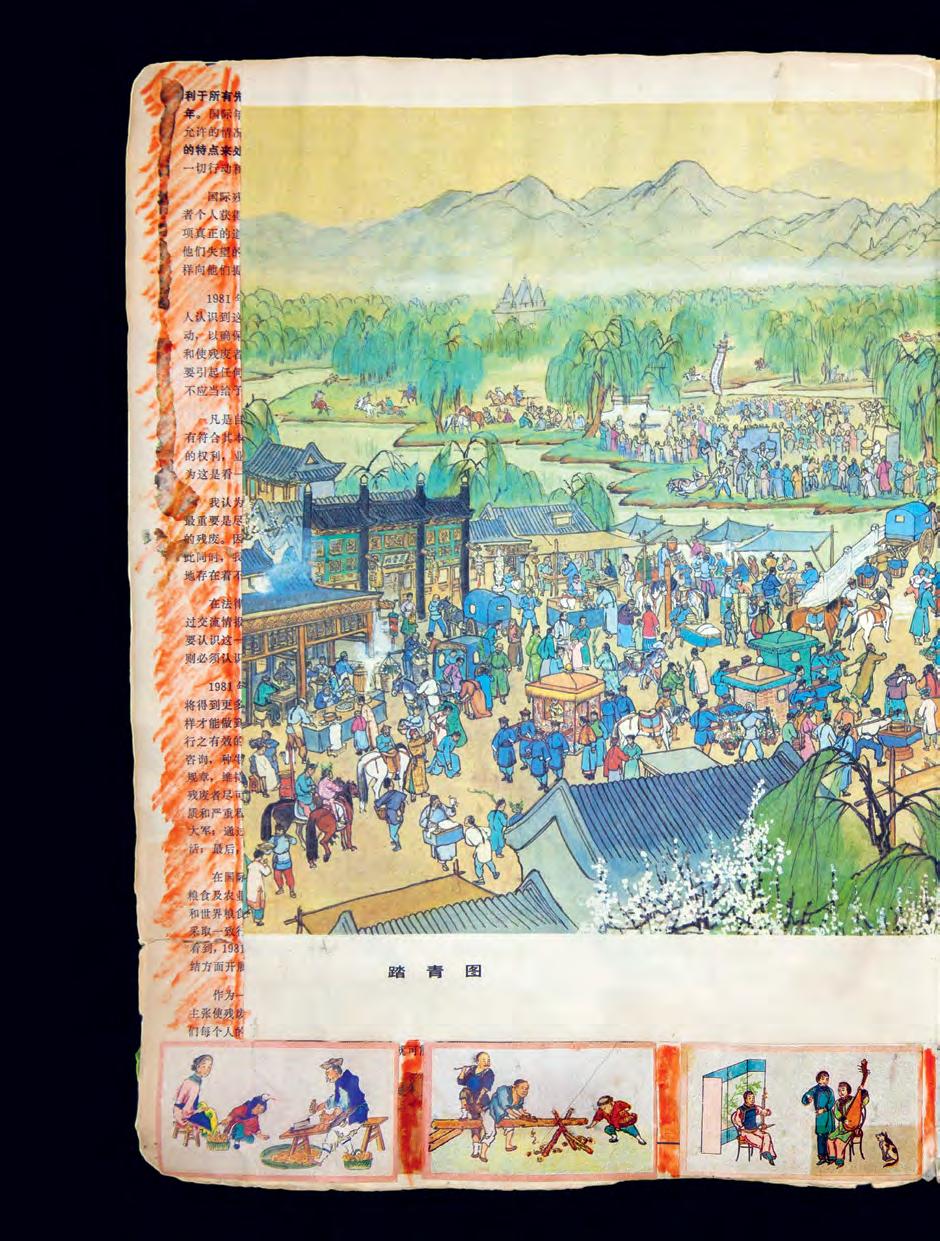

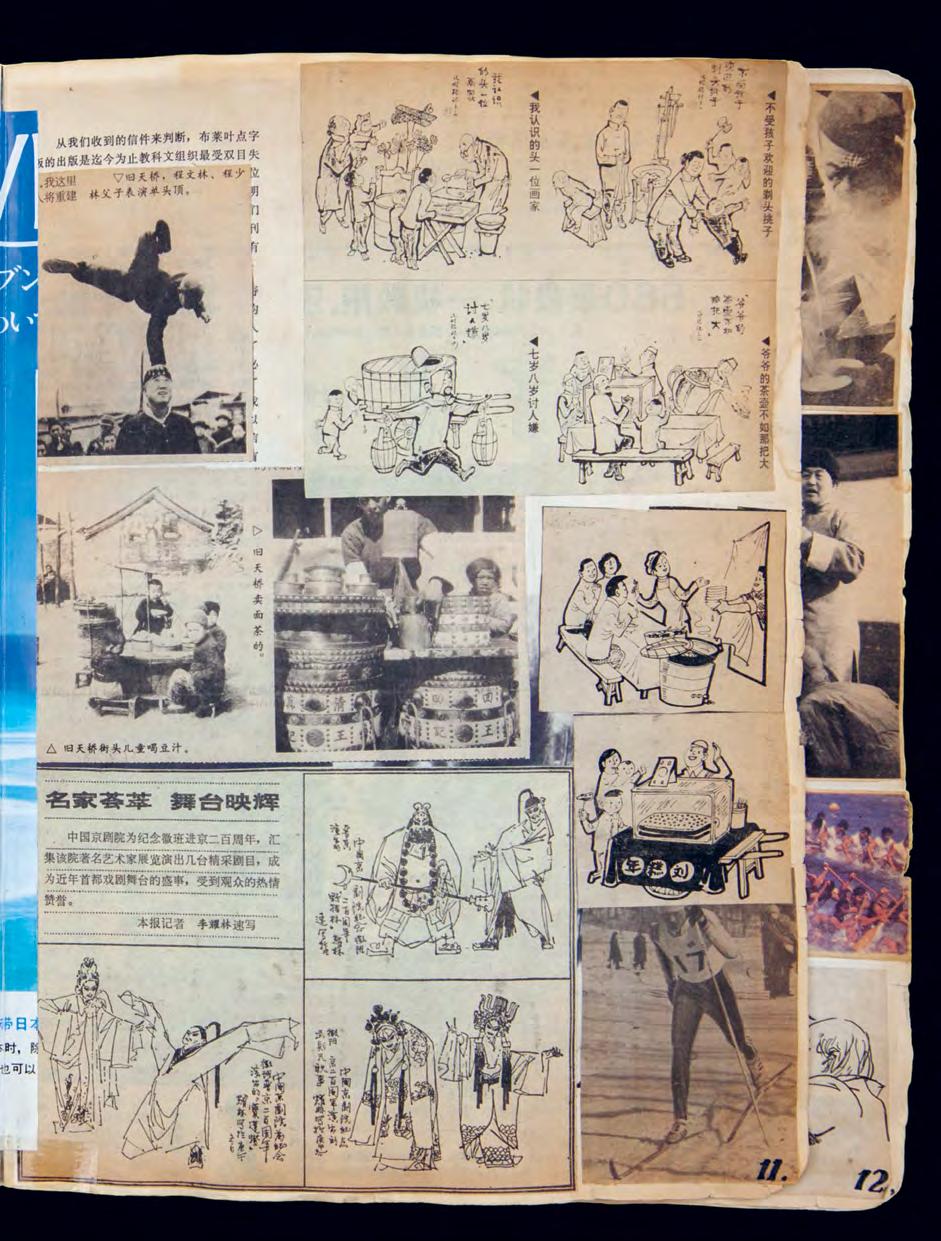

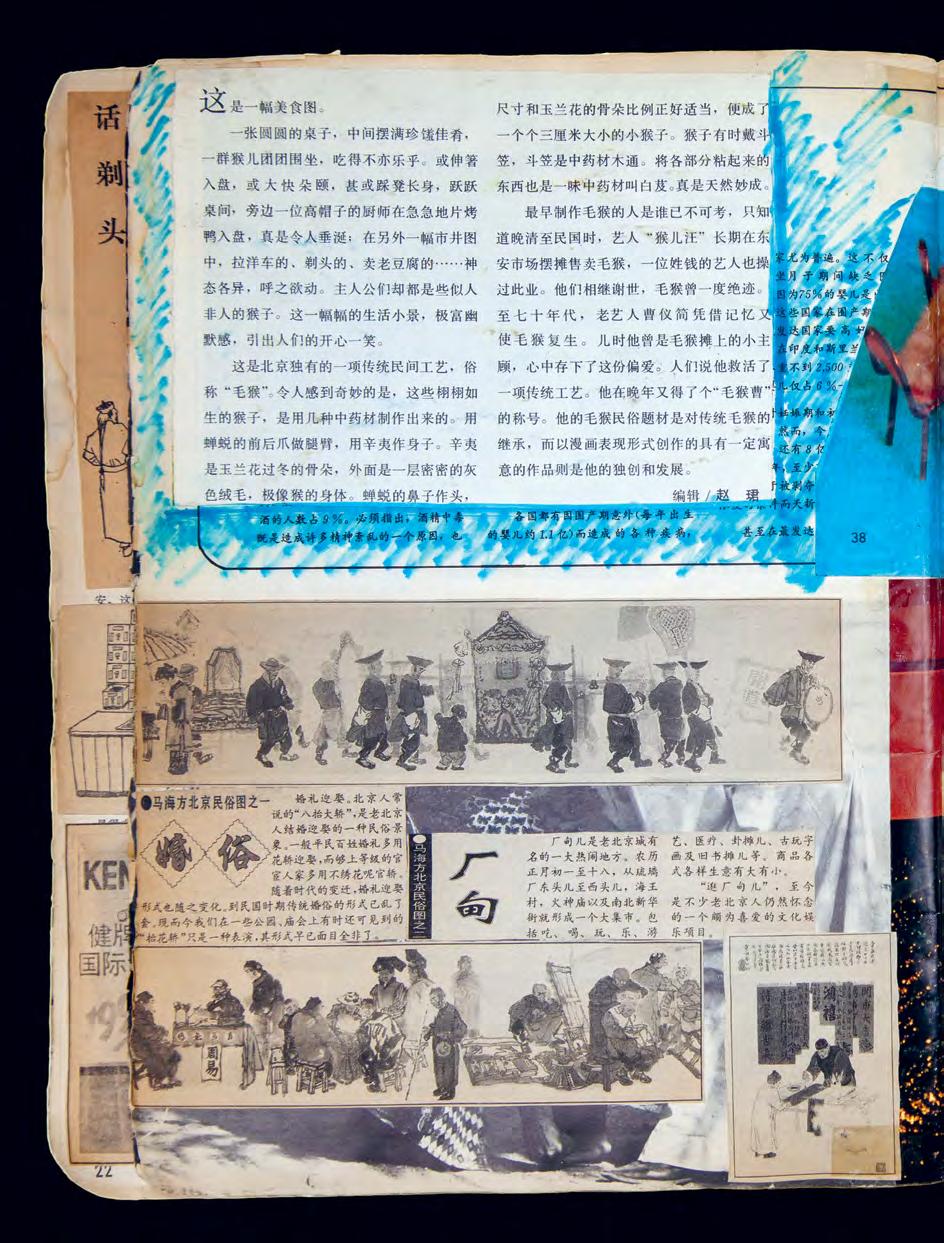

Traditionally, máohóu characters act as performers in dioramas that convey historical, cultural and societal customs. These miniature tableaux depict scenes of folklore, martial arts, acrobatics, music, opera and dance. They also portray historic Beijing street vendors, craftsmen and professions such as barbers, knife grinders, night soil collectors (human waste), water carriers, cart pushers, candied fruit sellers and fortune tellers. They preserve Beijing’s rich customs of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and The Republic of China (1912–1949) by presenting them for newer generations. Rich in humour and wit, the hairy monkeys express joy, anger, sorrow and happiness, reflecting the many facets of daily life and the collective consciousness of old Beijing.

Master Qiu Yísheng, who became a friend and with whom I shared many moments, feels that to honour the social critique origins of the art, máohóu should represent contemporary scenes and not just replicate ancient customs.

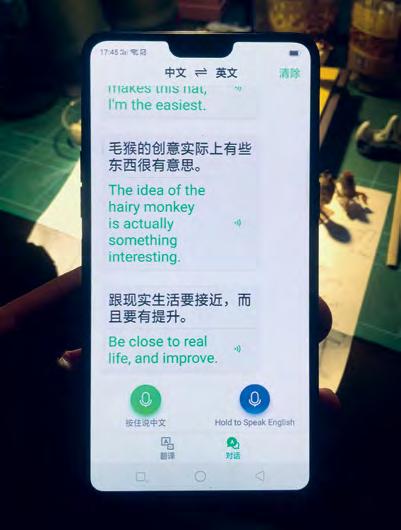

My Mandarin is non-existent, as is his English. Because of this language barrier, we had to rely heavily on translation applications. Through our smartphone conversations he told me: “One should absorb heritage and connect it to contemporary society; if you stick to old styles, it’s just a replica of a replica.”

Indeed, he is one of few máohóu masters to create tableaux dealing with contemporary life in China. After all, the art of the hairy monkey is about observing human life and reshaping it in miniature. The fusion of ancient techniques and modern themes such as overconsumption, corruption and gentrification struck me as very relevant, transcending the narrow categorisations often associated with traditional folk art. A few of Qiu’s tableaux have been sold to trustworthy collectors, but the bulk of his collection is intended to be kept intact in a museum for posterity. We hope this intention can come to fruition in the years ahead.

But let us take a step back, and allow me to share the context of how this publication came about.

In February 2019, I found myself in Beijing, meandering through a vibrant, outdoor festival during Lunar New Year. I had arrived in China a couple of weeks earlier for a six-month residency at the Institute for Provocation. 2

As the Year of the Pig began, the initial bubbling excitement of being submerged in an unfamiliar environment gave way to more complex emotions.

前言,

本书源于一个愿望:去分享、记录、礼赞并重新阐释中国 手工艺大师邱贻生的作品。他从事的是一门独具魅力的 艺术:毛猴。这项精巧的民间微缩艺术最早出现于 1820 年至 1850 年的北京。2009 年,毛猴被列入北京市非物 质文化遗产名录。时至今日,它仍相对冷门,许多北京本 地人都并不了解,遑论国际观众。

毛猴是一种约四厘米高的拟人昆虫小偶,由蝉蜕与冬季

的玉兰花茸毛花苞制成。这些原料本是传统中医药材。第 一只毛猴由一位药铺学徒所制,用以讽刺他的师傅(关于 起源的细节稍后会详述)。因此,追根溯源,这一奇妙的 民间艺术自诞生之初便带着顽皮与反叛的气质。

传统的毛猴常作为人物出现在立体模型之中,用来演绎历 史、文化与社会习俗。这些微缩场景重现了民间传说、武 术、杂技、音乐、戏曲与舞蹈,也描绘了老北京街头的百业 百态:剃头匠、磨刀匠、掏粪工(清除粪便)、送水工、推 车夫、卖冰糖葫芦的小贩、算命先生等。毛猴以幽默而机 智的方式呈现出老北京百姓的喜怒哀乐,反映日常生活的 多样面貌与集体心境,亦向后世保留和展现了清代与民国 时期北京的风俗脉络。

邱贻生先生——这位后来我们逐渐熟识并成为朋友的毛 猴手艺人——始终认为,为了回应毛猴艺术诞生之初所蕴 含的社会批判精神,作品不能仅仅停留在再现清代与民国 时期的生活,而应映照当下现实。我不懂中文,他也不会 英文。我们只能依赖翻译软件沟通。他曾通过手机软件上

的对话告诉我:“要吸收传统,同时让其与当代社会发生 联系。如果拘泥于旧样,那无非是复制的复制。”

事实上他是为数不多敢于创作现代题材毛猴场景的手工 艺人之一。毕竟,毛猴的精髓正是在于观察人类生活,并 以微缩的方式再造。古老技艺与现代主题的碰撞,譬如讽 刺过度消费、腐败与城市改造,让我深感其现实意义;它 超越了传统意义上的民间艺术范畴。

邱贻生的部分作品已被可靠的收藏家购得。不过他希望自 己的大部分作品能够完整保存,进入博物馆得以传世。我 们衷心期盼这一心愿能够在不久的将来实现。

在此之前,请允许我先回溯,谈谈这本书的缘起。

一次幸运的邂逅

2019 年 2 月,正值春节,我身处北京,在一个热闹的户外 庙会上闲逛。那时我到中国不过数周,刚刚开始在激发研 究所为期半年的驻留。

随着猪年的到来,起初那种沉浸在陌生环境中的兴奋逐 渐被更复杂的情绪替代。我很快意识到自己以往对中国 的想象是多么狭隘。我感到羞愧,不得不承认,自己曾不 自觉地吸收了许多偏见,而它们正不断被我的所见所闻 推翻。成长于 20 世纪 80 年代的欧洲,我潜移默化地继 承了一种对中国的恐惧。冷战的余音,以及随之而来的当 代全球政治话语,给我灌输了一个扭曲而简化的中国形 象:世界的廉价工厂、残酷的独生子女政策,缺乏细节和 复杂性。然而,当我在北京街头看到无数温柔、充满爱意 的父母时,那种“冷酷、无情的中国父母”的刻板印象瞬 间被击碎。

面对自身的无知,我选择直面这种不适。我开始有意识地 审视并拆解那些早已在心中扎根的欧洲中心主义偏见。

这个“去学习”的过程既必要,也让我觉得焕然一新。 言归正传!

春节假期期间,艺术驻地那支温暖可爱的团队回家与家人 团聚了,就像数百万北京打工人离开首都返回各自省份一 样。很多个夜晚,我独自走在驻地附近空旷、积雪覆盖的 胡同里,想象自己是后末日电影中的孤独角色。大多数商

I quickly realised how narrow my image of China had been. I felt ashamed to admit the extent to which I had absorbed prejudices and beliefs that were being constantly contradicted by what I was witnessing. Growing up in Europe in the 1980s, I had unconsciously inherited a certain fear of China. The echoes of Cold War ideology, and later, contemporary global politics, had fed me a distorted, simplified view, lacking nuance and complexity. I had internalised a dismissive image of China as the world’s cheap factory, the country of the cruel one-child policy, a place stripped of humanity. Yet, for example, seeing so many tender, loving parents on the streets of Beijing challenged the stereotype of the strict, emotionless Chinese parent. Faced with my own ignorance, I leaned into the discomfort. I began intentionally confronting and deconstructing the Eurocentric biases that had quietly taken root within me. The process of unlearning felt necessary and refreshing.

Anyway!

During the New Year break, the warm and lovely team of the art residency had gone home to their families, as do millions of Beijing residents who leave the capital for the provinces. For many nights, I strolled the empty, snowy hutongs3 surrounding the residency, imagining myself as a solitary character in a post-apocalyptic movie. Most of the shops and restaurants were closed. It felt ghostly and daunting. I hadn’t made any local friends yet, and my main companion was Lulu, the hutong’s grandmother cat (adopted by the previous artist-in-residence) that slept on my bed at night.

I experienced profound moments of loneliness. One day, I surprised myself by feeling drawn to a group of boisterous, alpha-male British tourists, if only to talk to someone who shared a common language. (For someone living in Amsterdam, large groups of loud men are usually associated with trouble, hooligans or bachelor party mayhem, which I tend to steer clear of!) I began to realise that six months away from my loved ones might prove challenging.4 However, this feeling of isolation was greatly softened when, on a crisp sunny day, I stumbled upon a Lunar New Year market in a park.

It was the Year of the Pig festival and the entire park was bursting with life and colour. My senses were highly stimulated. I wandered around, alongside loving families, absorbing new andunfamiliar smells and sounds. I saw countless pig characters in all sizes and materials, funfair attractions in the form of motorised snow tanks and bulldozers for children, dancing dragon acrobats, trees covered in red paper lanterns and aunties wearing super swaggy outfits. Then, a peculiar gift stall caught my eye. On a table, small bell jars were filled with anthropomorphic insect-like figures dancing or juggling. These jars seemed to be sold as decorative souvenirs. I had a visceral reaction of wonder upon seeing these bizarre creatures, which I found charming due to their size and intricate details, yet also slightly repulsive in their alien-like, slimy appearance. At the back of the stall were complex dioramas displayed in large glass cases. They depicted bustling street scenes with dozens of interacting figures, including a tableau of a New Year’s market, capturing the very atmosphere I was immersed in with uncanny precision.

I kept on exploring the market but these odd characters left a strong impression on me. Weeks later, at the end of the holidays, when the residency team returned from their home provinces, I eagerly asked if they could tell me more about these figures. To my surprise, no one had heard about them. We searched online in an attempt to identify what I had seen, but my clumsy descriptions yielded no results. After all, how does one describe such strange and unusual creatures? Luckily, after asking around through the residency’s network, a friend who was interested in folk art was able to put a name to these elusive figures. They were called máohóu, which literally means “hairy monkey”.

店和餐馆都关门了,街道显得阴森而令人发怵。当时我还 没有结识任何本地朋友,唯一的陪伴是一只名叫露露的 胡同老猫(前一位驻留艺术家收养的猫),它夜里总是蜷 缩在我的床上。

孤独感一度扑面而来。某天,我竟意外地被一群吵闹的 英国“阿尔法男”游客吸引,只因为我渴望用共同语言交 谈。(对住在阿姆斯特丹的人来说,成群的吵闹男人往往

意味着麻烦、流氓或单身派对的喧嚣,我一向避之不及!) 我开始意识到,六个月远离至亲的生活或许会十分难熬。

但在一个寒冷而晴朗的日子里,当我偶然闯入公园里的春 节庙会时,这种孤独感大大缓解了。

那是猪年的春节,整个公园洋溢着生命力与斑斓色彩,我 的感官完全被调动起来。我与无数温馨的家庭并肩而行, 沉浸在陌生的味道与声响中。眼前满是形态各异、材质不 同的猪形象;为孩子们准备的雪地摩托和迷你推土机;舞 龙队伍腾挪翻跃;树木上挂满了红色灯笼;阿姨们则身着 格外时髦的服饰。就在此时,一个奇特的礼品摊位吸引了 我的目光。几只小玻璃罩安放在桌上,罩内拟人又似虫的 小偶在跳舞或玩杂耍。这些玻璃罩似乎是作为装饰性纪 念品出售的。看到这些怪异的“生物”时,我心中涌起一 种本能的惊奇。它们微小的体型与繁复的细节令人着迷,

但外星人般的黏滑外观又让人隐隐生出排斥。在摊位后 方,更大的玻璃匣子里展示着更复杂的场景,描绘了熙攘 的街市,数十个小偶彼此交织。其中的一个场景正是“新 年庙会”,诡异而精准地再现了我身处的氛围。

我在庙会上一路闲逛,但那些奇异的小偶始终在脑海中 挥之不去,留下了深深的烙印。几周后,假日结束,驻地的 伙伴们从家乡归来,我迫不及待地询问他们是否知道这 些小偶摆件。让我惊讶的是,无一人听说过。我们尝试上 网搜寻,却因我笨拙的描述一无所获。毕竟,要如何形容 这样怪异而稀奇的事物呢?幸而,通过驻地的朋友圈子 打听,一位热衷于民间艺术的朋友终于揭晓了它们的名 字:“毛猴”。字面意思是“毛茸茸的猴子”。

由于毛猴的起源并无正式文字记录,我们今天所知的大 多来自代代相传的故事。以下的研究主要汇编自我与毛猴 传承人邱贻生的对话,以及我的同事蔡昕媛发给我的若 干中文文章的数字化翻译。由于几乎没有相关的英文资 料,我只能在有限的信息之上,尽力汇总与梳理我对这一 艺术形式的了解。

毛猴是一种小众的民间讽刺艺术,诞生于北京。在汉族文 化中,猴子象征聪慧、机敏与吉祥,因此自古便在文学、艺 术及建筑中频频现身。

从词源上看,“猴”与“侯”同音, 由此生发出许多妙趣横 生的双关。例如“封侯拜相”一词,意为“被封为侯爵并 拜为宰相”。“宰相”是皇帝之下最高的官职。它象征着社 会地位上升、仕途成功、获得政治权力或学术成就。在这 种背景下,毛猴已超越了一个奇巧小偶的范畴,成为象征 志向与成就的吉祥物。因此,它有时会被赠予科举在即的 孩童,寄托对他们前程似锦、人生顺遂的殷切期望。

传说,毛猴诞生于清代道光(1820–1850)或同治年间 (1856–1875)。在北京城外宣武门大街的一家名为“南庆 仁堂”的药铺,掌柜5脾气暴躁,常常呵斥、欺压伙计。一 天,一名正在抓药的学徒无端受到了掌柜的责骂,心中郁 愤难平。当天傍晚,他在烛光下清理蝉蜕时,忽然发现蝉

Since no official written records about máohóu’s origins exist, much of what we know comes from stories handed down through generations. Given the absence of English-language resources about this art form, the following account was compiled from conversations with the máohóu master Qiu Yísheng and digitally translated articles in Mandarin sent to me by my colleague Augustina Cai.

Máohóu, the “hairy monkey”, is an obscure, satirical folk art from Beijing. In Han Chinese culture, monkeys symbolise cleverness, charm and auspiciousness. They have long been admired and represented in literature, art and architecture.

Etymologically, the word hóu 猴 , meaning “monkey”, sounds like hóu 侯 , meaning “marquis”. This phonetic proximity, as you can imagine, has inspired many puns. Among them the phrase 封侯拜相 (f eng hóu bài xiàng), meaning “to be conferred the title of marquis and appointed as prime minister”, the highest official position under the emperor. The phrase represents social ascension, career success, political power or scholarly achievement. In this light, the máohóu becomes more than a whimsical figure: it serves as a symbolic blessing for ambition and achievement. This is why máohóu figures were sometimes gifted to children preparing for the imperial exams, expressing hopes for their future rise in status and success in life.

According to legend, the birth of the hairy monkey occurred during the Qing dynasty, during either the Daoguang period (1820–1850) or the Tongzhi period (1856–1875) in a herbal medicine shop called Apothecary of Benevolent Celebration (Nán Qìng Rén Táng) on Xua nwu ̌ ména , a main street just outside of Beijing. The apothecary owner5 was famed for his tyrannical temper, often bullying and shouting at the employees. One day, a young apprentice mixing medicine was unfairly scolded by his boss, leaving him frustrated. That evening, while cleaning cicada sloughs by candlelight, he noticed that the pointed head of the cicada resembled his employer’s sharp-nosed face.

Still upset, he channelled his frustration into crafting a small, comical, human-like figure using magnolia buds for the body, cicada shells for the limbs and head, and báij , a traditional herbal adhesive, to hold it all together. The result was a lively little monkey that mocked the apothecary and amused his colleagues. And thus, the first máohóu was born!

Upon seeing the odd little figure, the shopkeeper recognised a business opportunity. He instructed his workers to set aside the materials, selling them as “monkey ingredients” for families to craft toys. The low cost, accessible materials and simple crafting process made máohóu popular; even the poorest families could afford one for their children. Since the process of concocting traditional medicine took a long time, people could also make hairy monkeys while waiting for their orders to finish simmering. Customers adored these figurines, and the máohóu quickly became a hit in Beijing.

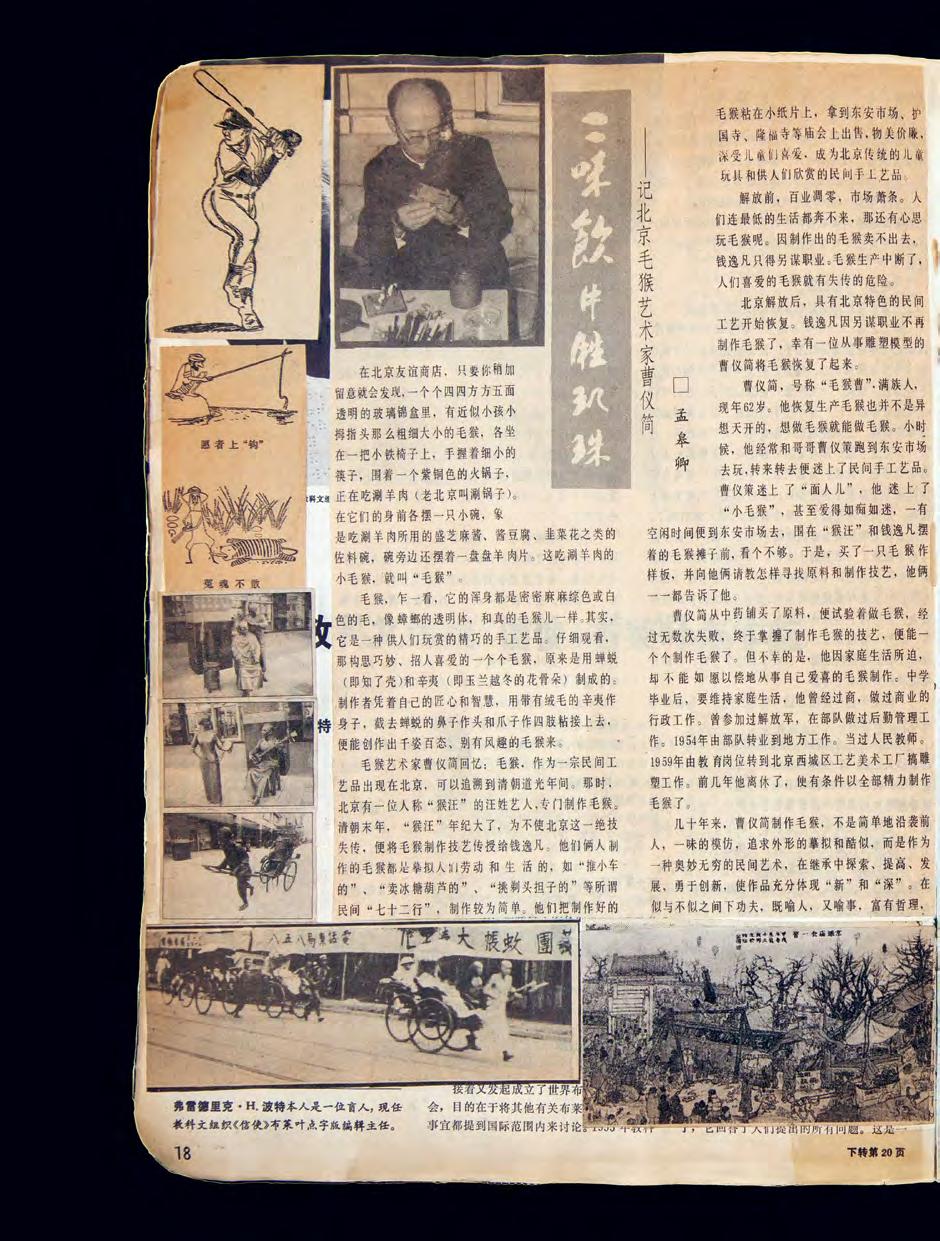

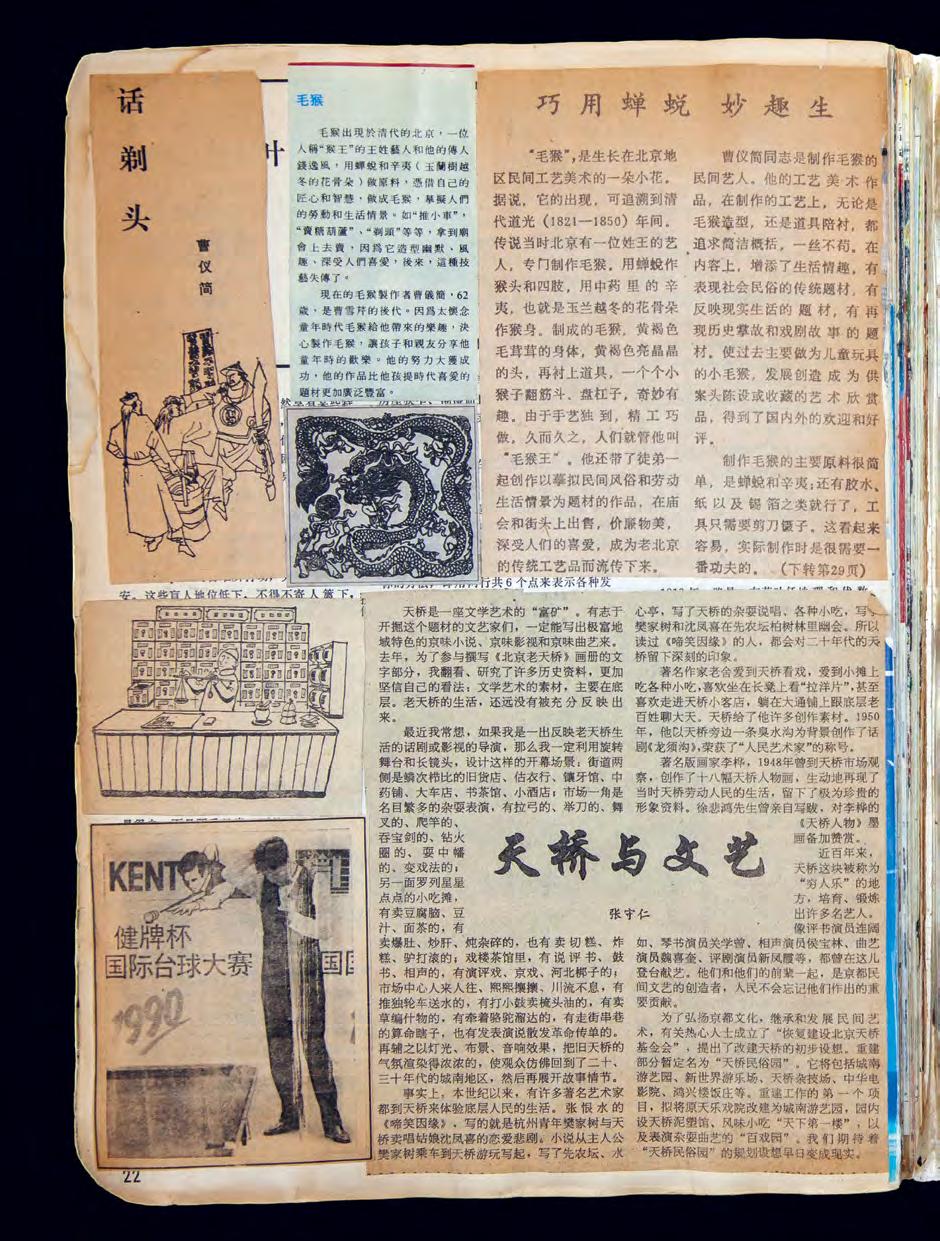

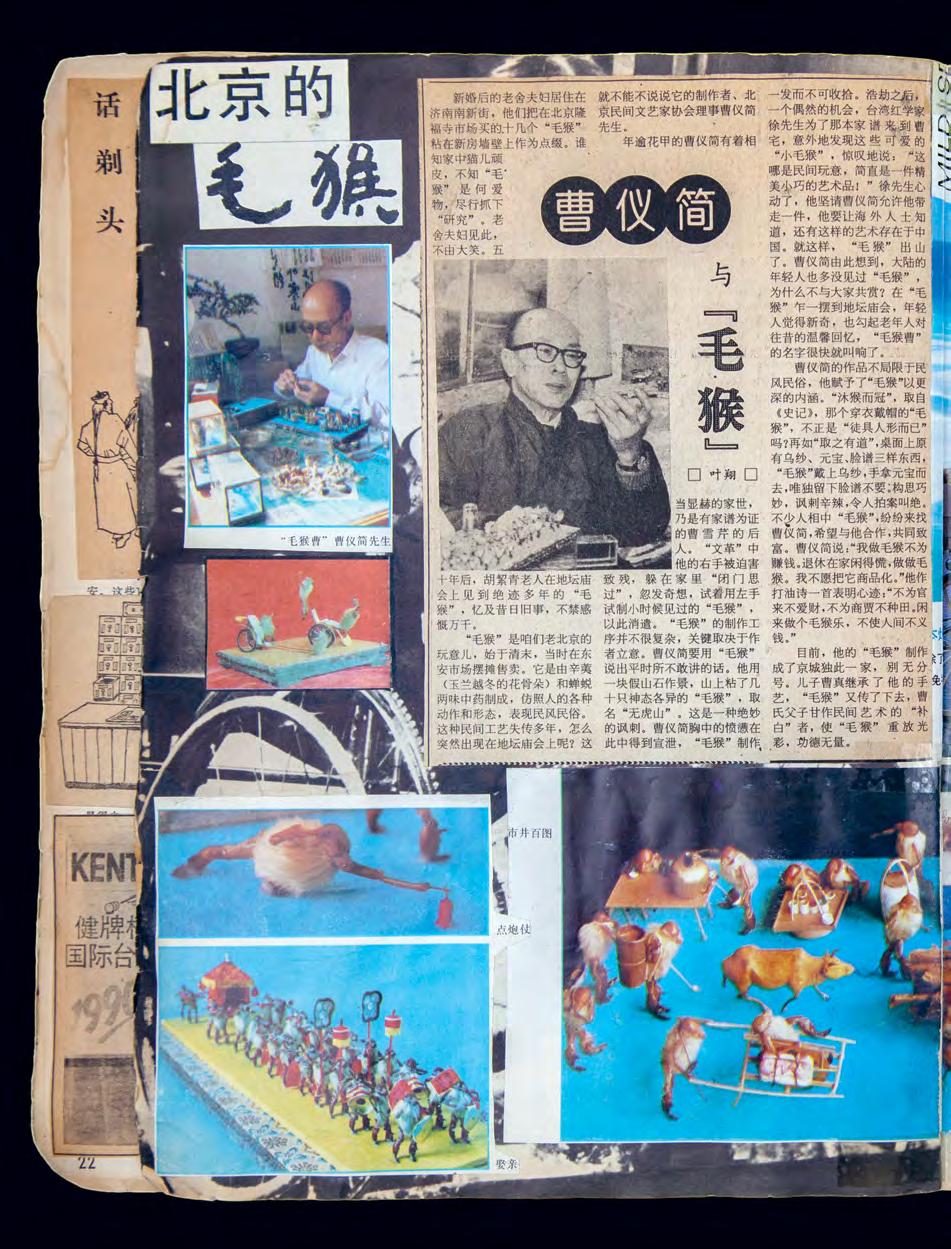

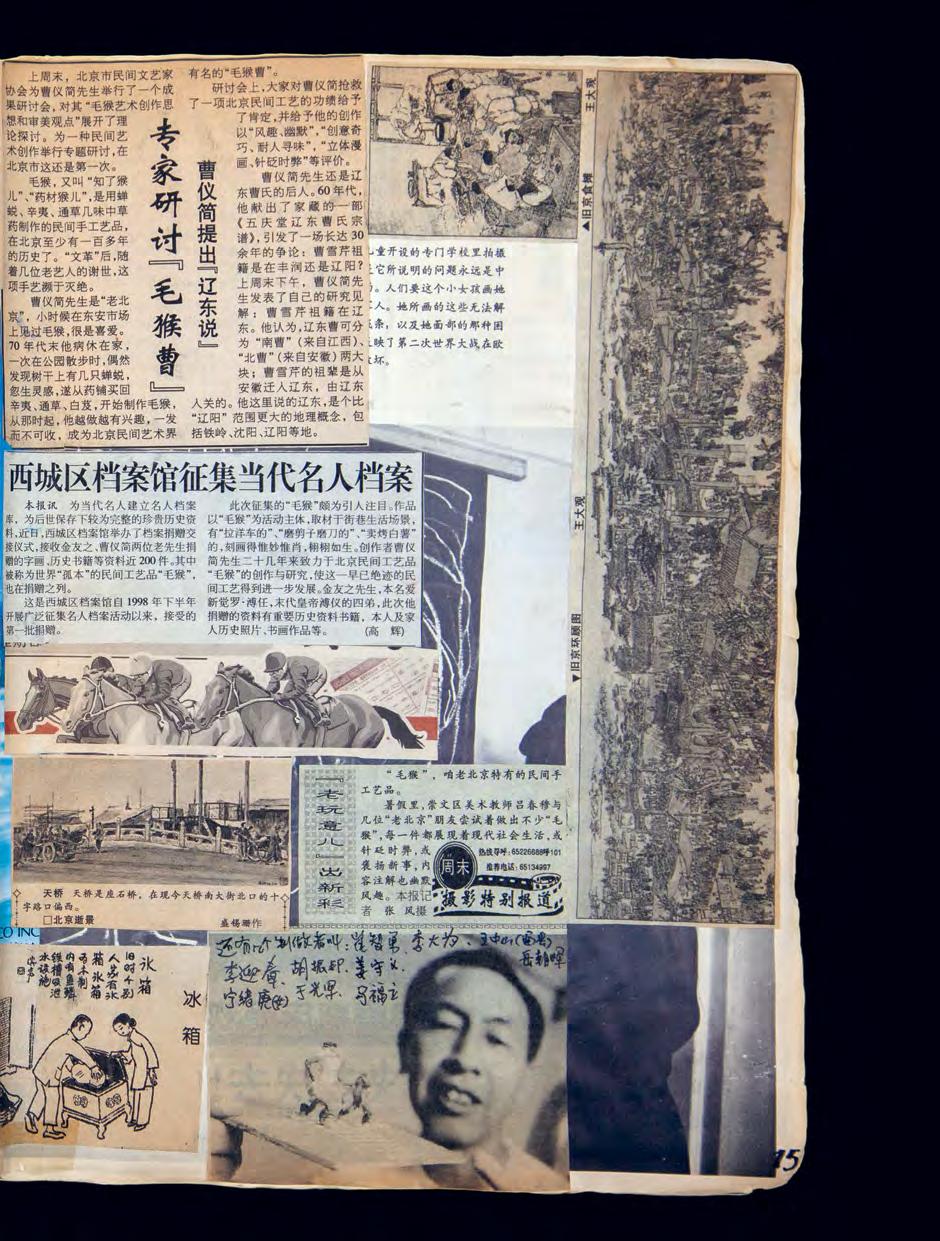

Over time, this humble craft evolved into the intricate yet unlikely folk art it is today. Skilled artisans elevated the form by recreating scenes from daily life, posing the monkeys in lifelike postures that mimicked human actions through precise body language. Without eyes, each figure relied entirely on the angles of limbs and the tilt of the body to express emotions, requiring expert craftsmanship. At old Beijing temple fairs, buying monkey materials and making máohóu was a cherished New Year tradition. Máohóu figures captivated many generations through their timeless allure, but sadly had nearly vanished by the 1960s, until Cáo Yíjia ̌ n6 曹仪简, who later became Qiu Yísheng’s master, reignited the art form with new life energy.

Representing countless professions and walks of life, Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n’s works were rich in wit and humour, reflecting old Beijing customs but also portraying modern social life, bringing the máohóu into the now. Some of Cáo’s máohóu figures went beyond aesthetic charm and carried political significance. For example, his diorama Amity is set against the backdrop of the Nanjing massacre, exposing and condemning the war crimes of Japanese imperialism in China.

壳尖尖的头部酷似掌柜那张尖嘴猴腮的脸。气未平的他 便把怒气化为巧思,用玉兰花苞作身、蝉蜕作四肢与头, 再用白芨(一种传统药材胶质)粘合,捏制了一个滑稽可 笑的小人偶。做出来的人偶像一个活灵活现的小猴子, 既讽刺了药铺掌柜,又逗乐了同伴。于是,第一只毛猴诞 生了!

看到这个古怪的小偶,掌柜立刻意识到其中的商机。他吩 咐伙计将这些材料单独留出,打包成“猴料”,供家庭自 制玩偶。由于成本低廉、材料易得、制作简单,毛猴很快 流行开来;即便是最贫困的家庭,也能为孩子做一个。而 且中药熬制的时间很长,人们在等待时正好可以顺便制作 毛猴。顾客们对这些小偶爱不释手,毛猴迅速成为北京的 热门玩意儿。

随着时间推移,这门小手艺逐渐发展为复杂而独特的民

间艺术。技艺娴熟的手工艺人们重现日常生活的场景,通 过精准的肢体语言将小猴摆出逼真的人类姿态。它们没 有眼睛,仅凭四肢的角度与身体的倾斜来传达情绪,这需

要极高的技艺。在老北京的庙会上,购买“猴料”、制作 毛猴曾是人们珍视的新年习俗。毛猴的魅力曾打动过许 多代人,但到 20 世纪 60 年代几乎销声匿迹。直到曹仪 简(后来成为邱贻生的师傅)为其注入新的生命力,毛猴 才得以复兴。

曹仪简的作品囊括了无数职业与生活场景,机智风趣,既 再现了老北京的风俗,也描绘了当代社会,让毛猴真正走 入当下。他的一些毛猴作品更超越了单纯的审美趣味,饱 含政治意义。例如,组景《亲善》以南京大屠杀为背景, 揭露并谴责了日本帝国主义在华的战争罪行。他那富于隐 喻与批判的风格,深刻影响了新一代毛猴手工艺人,并将

毛猴手艺拓展成一种新的艺术体裁。他的作品也因此在 国内外广受赞誉。

如今,这些神秘的小猴子已被公认为北京独特的纪念品。 与一般儿童玩具不同,毛猴组景是供人观赏的陈设之作。 它们常出现在春节集市、庙会和民俗文化节中。单个毛猴 通常被放在小玻璃罩内售卖,而更复杂的立体模组则多 用于展览欣赏,很少出售。在这些节庆场所之外,毛猴组 景几乎难得一见,除非专门去寻找。或许是因为在这座两 千多万人的大都市里,真正的毛猴手工艺人已寥寥无几。

这带有讽刺意味的玩具/工艺/艺术形式背后的故事让我 十分着迷,我迫不及待地想了解更多。在驻地团队的帮助 下,我们联系上了毛猴手工艺人邱贻生,他邀请我们去他 的家和工作室做客。一走进他的空间,我顿觉亲切。不拘 一格的室内陈设,摆满了各式各样的奇异雕塑与小物件。

F16 战机模型旁,一个苏格兰高地人木 偶夹在毛绒骆驼纪念品之间,一尊非洲雕像靠着列宁套 娃与摇头足球运动员!这种跨越年代、文化、符号与质感 的怪异并置,让我想起自己那些五花八门的收藏,仿佛回 到了家。我惊叹于,两个天南地北的陌生人竟有如此相似 的审美趣味。

邱贻生先生与我分享了他如何投身这门艺术,如何与师傅 相识的经历。看到他珍藏的大量精美毛猴组景,我倍感振 奋,为其海量作品出版一本书的念头也随之萌生。由于关 于毛猴的出版物十分稀有,邱贻生欣然答应了我们的提 议,希望借此让更多人认识这一罕见的民间艺术瑰宝。

His style and approach, rich in metaphor and criticism, profoundly influenced new generations of máohóu makers and expanded the craft into a new artistic genre. His work became celebrated both at home and abroad.

Today, these enigmatic monkey figures are recognised as souvenirs unique to Beijing. Unlike typical children’s toys, máohóu dioramas are contemplative display pieces. They appear at Lunar New Year markets, temple fairs and folk cultural festivals. They are mostly sold as single characters in small bell jars, while more elaborate dioramas are displayed for admiration but rarely sold. Outside these festive locations, máohóu dioramas are seldom seen unless specifically sought out. Perhaps this is because there are only a handful of máohóu artists in a city of more than 21 million inhabitants.

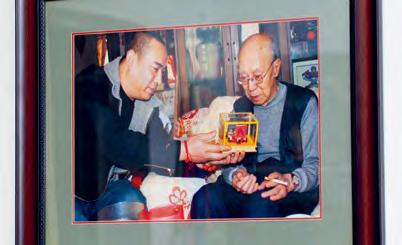

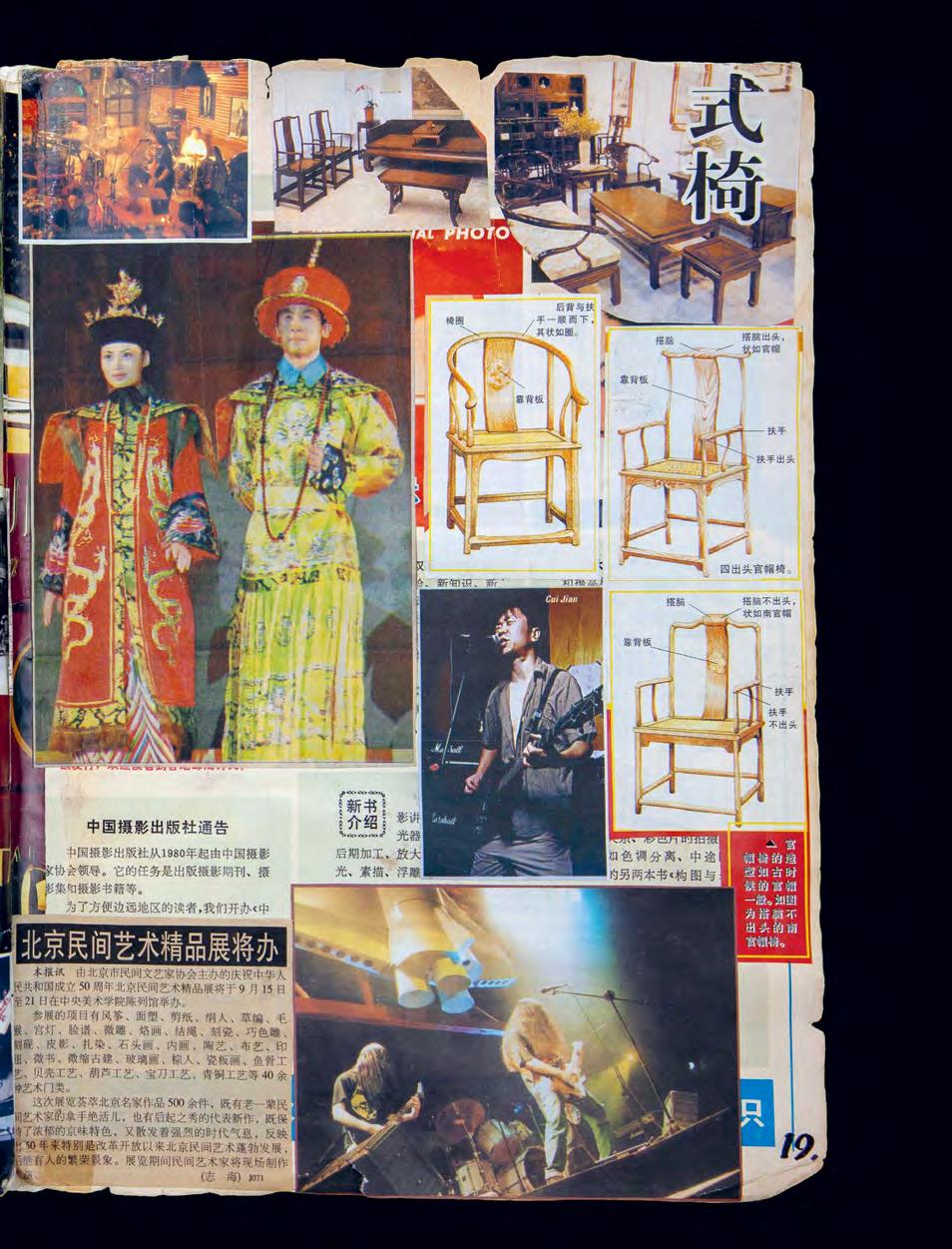

Fascinated by the cheeky backstory of this satirical hybrid toy/craft/art form, I was eager to learn more. With the support of the residency team, we contacted the máohóu master Qiu Yísheng, who invited us to his home and workshop. Entering his space, I felt an immediate kinship. His eclectic interior brimmed with strange sculptures and knick-knacks. He had placed a nautilus shell next to an F16 model plane, a Scottish highland nutcracker next to a furry camel souvenir, an African statue next to a Lenin matryoshka doll and a bobble-head footballer! These bizarre juxtapositions of eras, cultures, symbols and textures reminded me of my own collections of eclectic objects and made me feel at home. I marvelled that two strangers on different sides of the world shared similar aesthetic sensibilities.

Master Qiu Yísheng shared the stories that led him to dedicate his life to his art and how he met his master. Seeing his archive of intricate máohóu dioramas was exhilarating, and the idea to make a book about his impressive body of work started to emerge. Since very few publications exist on the subject, Qiu welcomed our proposal to spread the knowledge about this rare folk art gem.

The spirit of máohóu craftsmanship is deeply rooted in perseverance. The art of the hairy monkeys nearly disappeared between the 1940s and 1980s and was on the brink of extinction but resurfaced thanks to a handful of devoted artists. According to Qiu, about ten máohóu masters still practice in Beijing today, along with some retirees who, having learned the craft in their youth, have returned to it as a pastime. Despite growing interest, few young practitioners are willing to dedicate their lives to the máohóu as many prefer quick results and settle for mastering only the basic monkey-gluing techniques. Some even copy well-known designs for mass production, diminishing the value of the art form. But whereas making a single hairy monkey is simple, building an entire diorama requires painstakingly slow, careful work.

The craft requires meticulous care and the process of gathering máohóu components is intricate. Miniature figures are composed of cicada exoskeletons7 and yùlán magnolia flower buds, both ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine. Cicada shells, known as 蝉蜕 (chán tuì), are used, among other things, for their anticonvulsant and sedative properties — or to make the monkey’s heads and limbs! The ideal shells are golden, large and not rain-damaged. They are found on trees in spring or early summer. Dirty shells must be cleaned meticulously through a process called “purifying the shell”. Magnolia buds, known as 辛夷 (x n yí), are covered in grayish-brown fuzz and resemble a monkey’s body. Used to treat nasal congestion, asthma, anxiety and toothaches, they are best harvested during the twelfth lunar month. If picked too early, they are not full enough, resulting in weak bodies; picked too late, they crack and crumble.

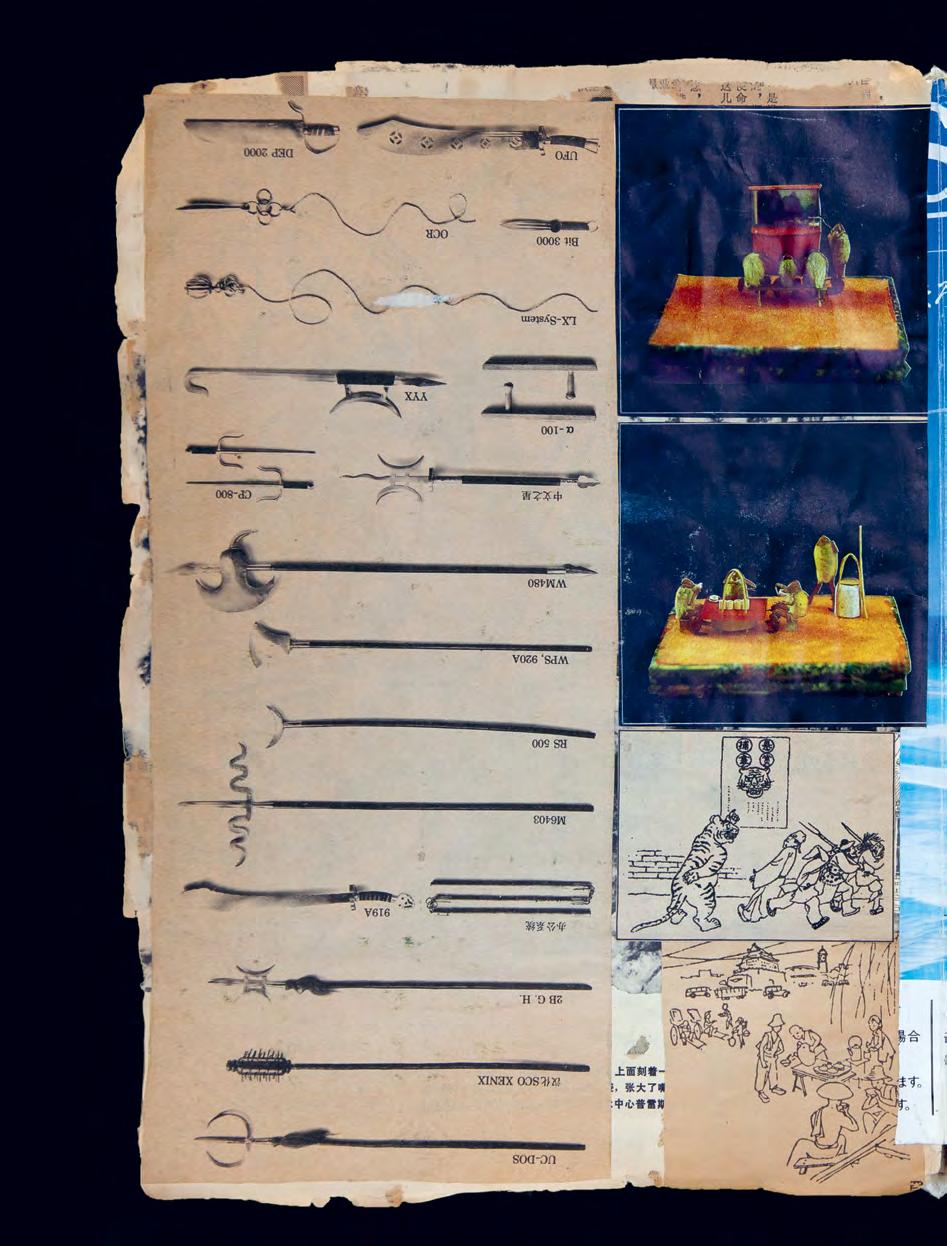

Traditionally, the glue used to bind all the parts together was made from a Bletilla orchid, or urn orchid, called 白芨 (báij ), which when crushed and heated with water creates a natural adhesive. Props were often sculpted using Akebia quinata, commonly known as chocolate vine, prized for its soft, wood-like texture. The tools used to sculpt the hairy monkeys have remained humble throughout the history of the art form: knife, scissors,

简单的材料,复杂的手艺 毛猴的精神在于坚持。20 世纪 40 至 80 年代,毛猴手艺 几乎消失,濒临灭绝,却因少数几位痴心匠人的守护而重 获新生。邱贻生说,如今在北京还有十名左右的毛猴手工 艺人仍在坚持创作。有一些老人,他们年轻时学过这门手 艺,退休后又重新拾起,作为闲暇消遣。尽管关注度有所 提升,但愿意将一生奉献给毛猴的年轻人凤毛麟角。许多 人追求速成,只停留在最基本的“粘猴子”技法;甚至有 人抄袭流行的造型进行批量生产,令这门艺术的价值大 打折扣。然而,制作单个毛猴或许简单,但要营造出一个 完整的立体模型组,却需要极为缓慢而细致的工夫。

毛猴制作要求高度的细心与耐心,光收集毛猴材料本身 就十分繁琐。微缩小偶的身体由蝉蜕与玉兰花苞构成,这 两样原料同时也是传统中药材。蝉蜕有镇痉、安神等功 效,在毛猴制作中被用来做头部与四肢。理想的蝉蜕要 呈金黄色,个头大,且未经雨水损坏。它们多在春季或初 夏采集自树上。脏污的壳必须经过一道被称为“净壳”的 工序,细致清理。玉兰花苞,也叫“辛夷”,外覆棕灰色茸 毛,形似猴身。它在中医中用于治疗鼻塞、哮喘、焦虑与 牙痛。最佳采摘时间是农历腊月。若摘得太早,苞不够饱 满,身体显得瘦弱;太晚则会裂开、易碎。

传统上,用于粘合各部件的胶来自白芨捣碎后加水加热 即可生成的天然黏合剂。道具往往以木通藤雕刻而成,这 种植物材质柔软,极适合造型。毛猴制作所需工具自始至 终都很朴素:小刀、剪刀、毛笔与镊子。然而,如今透明胶 水与现代材料大多取代了自然材料白芨与木通。当代的手 工艺人也会用电动雕刻工具加工木材或塑料,并不断发明 DIY 方法以制作更复杂的道具。

毛猴的制作并无统一的标准,每位匠人都会确立属于自 己的方法,无论是题材还是视觉上。有的专注于历史题 材,有的则关注现实问题。但通常,创作者会先在心中构 想场景,再去挑选最合适的蝉蜕与玉兰苞,以塑造出恰当 的猴子姿态。

毛猴在形态上的细节可以千差万别。邱贻生老师向我展 示了他在造型上的一些创新:他为毛猴加上发型、手袋、 眼镜与裤子,使其美学表现有所突破。我还见过另一位手 艺人制作的猴子鼻头通红。在我看来,这种处理突出了小 丑般的滑稽感,却减弱了那份怪诞的真实感。毛猴本已是 对人类的讽喻,何必再添一层戏谑?

在我看来,邱老师作品中的某些角色带着温和、俏皮的 能量,而另一些则散发着鬼祟、油滑的气息。他们过度阳

brushes and tweezers. However, clear synthetic glue and modern materials have largely replaced natural ingredients like Bletilla and Akebia. Contemporary masters also use rotary tools to carve wood or plastic and regularly invent DIY methods to shape increasingly intricate props.

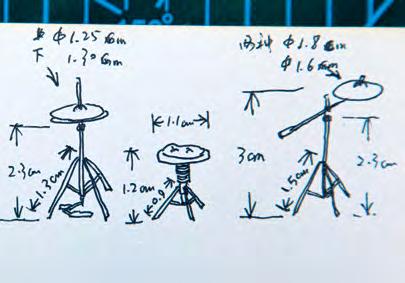

There is no standardised method for making a máohóu; each artist defines their own approach, both thematically and visually. Some masters choose to focus on history, others on contemporary issues. Yet it is common practice for masters to first envision scenarios before selecting the cicada shells and magnolia buds that will help create the right poses for the monkeys.

Details in a máohóu’s anatomy can vary and Master Qiu Yísheng shows me examples of his innovations regarding the monkeys’ appearance. He has introduced hairstyles, bags, spectacles and trousers, pushing aesthetics into new territory. I’ve seen some monkeys by another maker with red noses, which, to me, accentuates the clownish aspect and makes the figure feel much less uncanny. The máohóu is already a form of human parody, why add another layer of ridicule?

To me, some of Master Qiu Yísheng’s figures have a gentle, cheeky energy, while others ooze shady, sleazy vibes. They are hyper-masculine, vile characters with money and power who seem repulsive due to their superior attitude and toxic behaviours, rather than their “insect-ness”. Their liveliness reflects the amazing observational and sculpting skills of Qiu, who, with subtle details, animates characters full of spirit and psychological complexity.

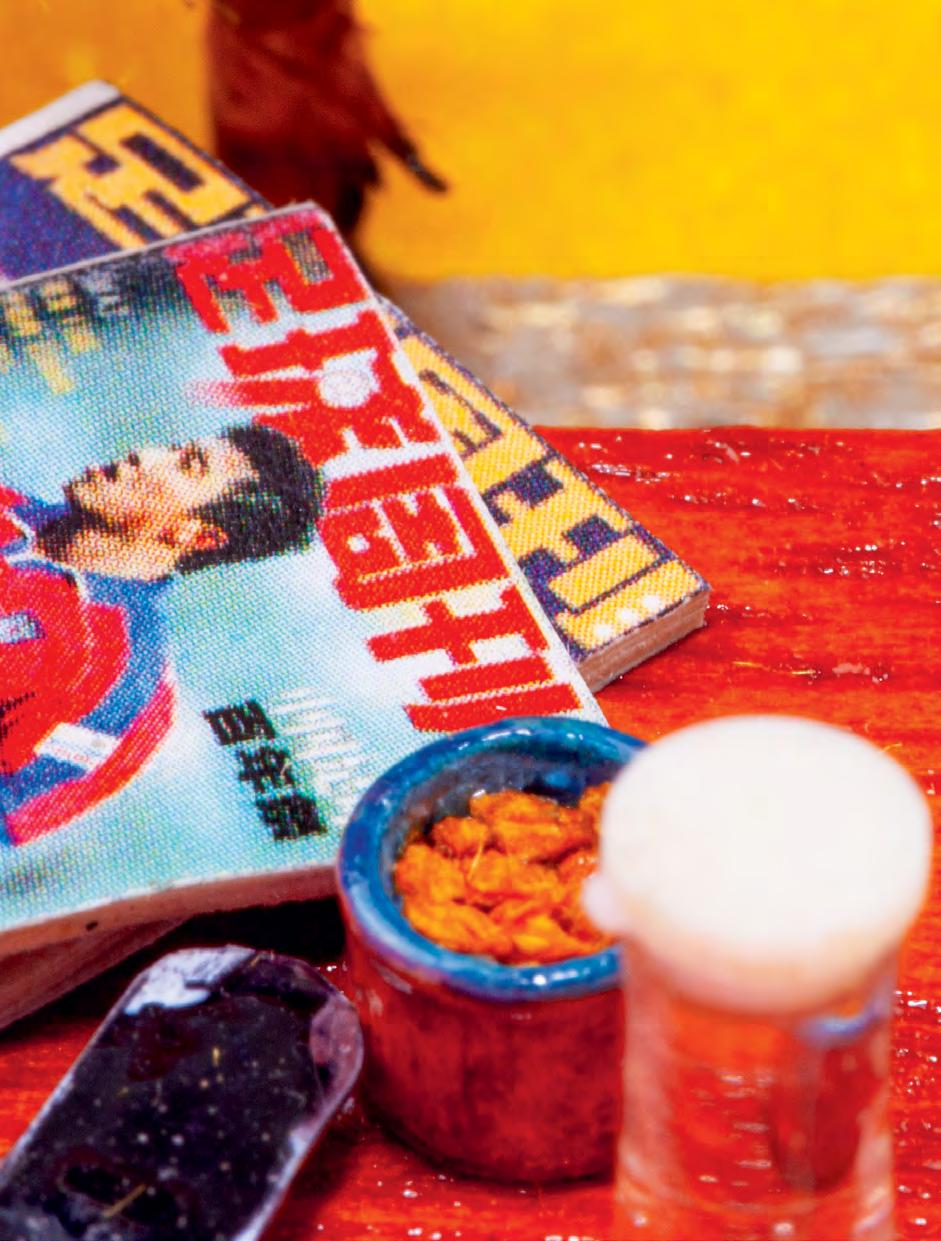

Despite the uncanny energy of the figures themselves, much of a máohóu master’s artistry lies in crafting objects, environments and furniture for them. I read in an article that “for a craft invented as a joke, it has a lot of rules”, and one main rule is that everything must be handmade. As Qiu tells me, he has always liked sculpting, a fact confirmed in an online feature about his work: “Qiu Yísheng’s prolific hand is praised by his peers. He transforms paper boxes and fallen branches into desks, chairs and even guitars. He also collects broken glass, cotton swabs, and

plastic. In Qiu’s eyes, this rubbish becomes the future stage for a máohóu performance. His work is admired as an environmentally conscious form of folk art.” 8 This act of reappropriating materials resonates with my own artistic practice, where I also seek to recontextualise mass-produced objects or highlight their often undervalued beauty.

Far more than whimsical curiosities, máohóu have evolved from simple toys to complex dioramas carrying philosophical and sociopolitical commentary. Artists use symbolic imagery, cultural references, puns and rhymes to embed subtle meanings, many of which may be lost on outsiders or non-Mandarin speakers like myself.

Máohóu dioramas traditionally reflect ethics and morals by reimagining Chinese myths and tales which express values such as humility, teamwork and community. These classic narratives, with the anthropomorphic hairy monkey as the new protagonist, weave philosophical Confucian virtues such as benevolence 仁 (rén), righteousness 义 (yì), propriety 礼 (l ˇ ), wisdom 智 (zhì) and sincerity 信 (xìn) into artistic form. They blend moral teaching with folk creativity, using humour to make the lessons more engaging and memorable.

In Master Qiu Yísheng’s works, however, satire often takes precedence over traditional moral lessons, just like in his master’s work. While comical on the surface, his thought-provoking pieces invite viewers to look deeper, beyond the charm and wit, into the contemporary realities they reflect or challenge. The meanings behind some of the master’s dioramas are explored in an interview featured in this publication. This gives a peek into his ideas and creative process.

刚且卑劣,充满金钱与权力的气味。令人厌恶的并非它 们的“虫性”,而是那种高高在上的姿态与恶劣行径。这 些角色的栩栩如生正体现出邱老师非凡的观察与造型功 力。着力于细微之处,他塑造的角色不仅充满神韵,还蕴 含着复杂的心理层次。

除了毛猴的逼真怪诞,一位毛猴传承人真正的功力还体现 在制作物件、环境与家具上。我曾在一篇文章里读到: “这门起源于小玩笑的手艺,却有着不少严格的规定。” 其中最主要的一条便是所有东西必须手工完成。邱贻生 告诉我,他一直喜欢做雕塑。网络上的一篇报道也这样 评价他:“邱贻生的娴熟技艺受到同行高度认可。他能把 纸盒和枯枝变成桌椅甚至吉他。他还会收集碎玻璃、棉

签与塑料。在他眼里,这些废弃物都是未来毛猴舞台的 素材。因而,他的作品也被视为一种具有环保意识的民间 艺术。”这种对材料的挪用行为也呼应了我自身的艺术实 践:我同样试图为批量生产的物件赋予新的语境,或强调 它们常常被忽视的美感。

毛猴早已不止是让人好奇的古怪玩物,而是发展为承载 哲思与社会评论的复杂组景。手艺人们借助符号性的意 象、文化典故、双关与谐音,巧妙地将意义植入作品中。然 而,对外来者或如我这般不懂中文的人来说,许多内涵恐 怕难以捕捉。

传统的毛猴组景通过重新想象中国神话与传说来表达伦

理与道德观念,彰显谦逊、协作与群体价值。拟人化的毛 猴成为新主人公,演绎这些经典叙事,将儒家哲学的传统 美德——仁、义、礼、智、信——融入艺术表达。结合了民

间创造力和幽默的道德教化,让人难忘。

然而,在邱贻生的作品中,讽刺往往优先于传统道德训 诫,就像他的师傅一样。看似滑稽,实则发人深省。他的 作品越过机智风趣,邀请观者直面其所反映或挑战的当 代现实。本书中收录的访谈,以及我们通过手机对话的片 段,揭开了部分毛猴组景的含义,也让读者得以窥见其思 想与创作脉络。

我认为,毛猴传统,尤其是邱贻生的作品,可以与法国画 家奥诺雷·杜米埃怪诞讽刺的漫画相类比。这些漫画揭露 了 19 世纪后法国大革命时期律师、法官与资产阶级的腐

败与滥权。杜米埃也关注普通人和工人阶级的日常生活。 他的作品影响了先锋派对“日常”与“平凡”的兴趣,更进 一步启发了梵高在《吃土豆的人》中对农民生活原真而充 满共情的刻画。邱贻生的一些作品也让我联想到乔治·格 罗斯对二战前德国富裕精英、军人和政客丑恶嘴脸的勾 勒。从这个角度看,以日常生活场景为核心、饱含社会意 识的毛猴传统也可以被纳入更广阔的艺术史语境:激发 批判性思考、用讽刺挑战现实的艺术运动。

毛猴大约诞生于 1820 至 1850 年间,奇妙的是,这与摄 影术的发明几乎同时(1826 至 1827 年,由约瑟夫·尼塞 福尔·涅普斯完成)。无论是立体模型还是摄影,都源自 同一种冲动:对“凝固瞬间”的渴望。那些将昆虫小偶的 动作定格的静态场景,可以看作是早期纪实摄影的雕塑 化版本。

用一种强调静止的媒介去记录静止的场景,似乎有些矛 盾。然而,我相信,我的微距摄影为这些凝滞的场景重新 注入了运动。放大的视角让我们的目光更靠近主体;我们 被吸入场景,不再悬浮其上,而是参与其中。哪怕只是片 刻,我们不再是旁观者,而成了毛猴世界里的一员。

出版过程与日渐深厚的友谊

本书中的影像拍摄于 2019 年炎炎夏日的北京,耗时两周 多。我在邱贻生老师的客厅里搭建了临时影棚。因为有棚 拍经验,我的操作十分谨慎。在观察了我一天之后,邱老 师开始信任我能妥善对待他那些极其脆弱的作品,并允 许我记录下了大约七十个毛猴组景。在连续数日拍摄这 些小剧场后,那些毛猴仿佛真的活了过来。我得以一窥邱 老师在无数透过放大镜工作的时间里,为物质注入生命 力的过程。他说:“要把握作品的精髓,你必须把自己置 于场景之中。越接近毛猴,就越能与它们交流。如此我们 才能感受它们的喜怒哀乐。”

我们的交流依赖手机上的翻译软件、笑容与手势。尽管语 言不通,但凭着对怪诞物件与讽刺的共同兴趣,我们建立 起联结。也因为都喜欢玛丽亚·凯莉、说唱与 R&B 音乐而 更加亲近。第一次拍摄时,邱老师把玛丽亚·凯莉的专辑 《 Honey》一连播放了五遍。我非常喜欢!接下来几周,

I feel that the máohóu tradition, especially in the hands of Master Qiu Yísheng, parallels the grotesque caricatures of Honoré Daumier, who exposed the corruption and abuse of power by lawyers, judges and the bourgeoisie of postrevolutionary 19th-century France. Daumier also focused on the lives of ordinary people and the working class. His work influenced the avant-garde’s fascination with the mundane and the banal, leading to Van Gogh’s crude yet compassionate depiction of peasant life in The Potato Eaters.

Some of Qiu’s figures also remind me of George Grosz’s repulsive portrayals of the wealthy elite, military and politicians of pre-World War II Germany. In this sense, the máohóu tradition, centred on scenes of daily life and imbued with a sharp social awareness, can be seen as part of a broader historical movement in art that sought to provoke critical thought and challenge the status quo through satire.

The birth of the máohóu, estimated between 1820 and 1850, curiously coincides with the invention

of photography (1826–1827, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce). Dioramas and photography share a common impulse: the desire to fix a moment in time. The static tableaux of insect figures frozen in motion can be seen as sculptural equivalents of early documentary photographs.

The act of documenting a motionless scene with a medium that heightens stillness can seem paradoxical. Yet I believe that my macro photographs help restore movement to these immobile scenes. Magnification draws our eyes closer to the subject; we are submerged in the tableau, our gaze no longer hovering above but joining the action. For a moment, we cease to be spectators and become one of the hairy monkeys ourselves.

The publication process and a growing friendship

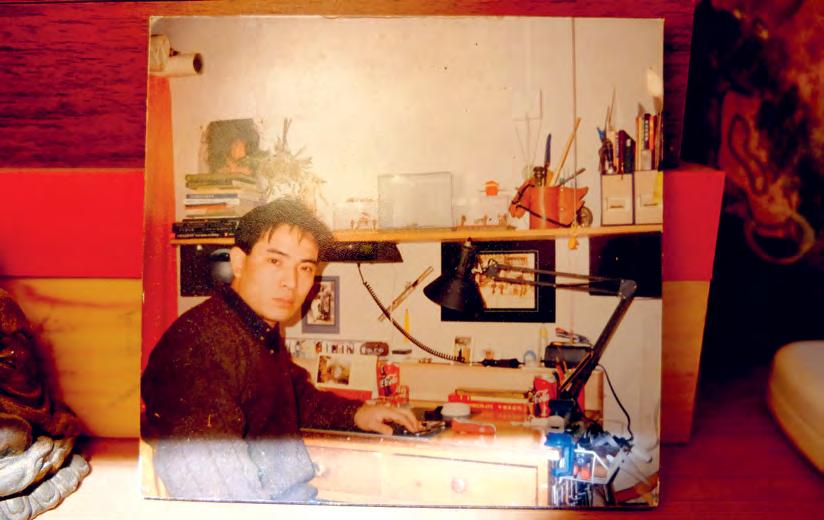

The photos for this publication were taken over a period of two weeks in a makeshift studio in Master Qiu Yísheng’s living room during a warm, Beijing summer in 2019. Having a background in studio photography, I worked with precision. After observing me for a day, Qiu trusted me to handle his extremely fragile work with care. He allowed me to document about seventy of his dioramas. After I spent days photographing the tableaux, the hairy monkeys started to feel eerily alive. I glimpsed what Qiu might experience through the countless hours he spends behind his magnifying glass, breathing life into matter. He says: “To grasp the essence of the work, you have to put yourself in the scene. The closer we approach the máohóu, the better we can interact with them. Then we can feel their happiness and sorrows.”

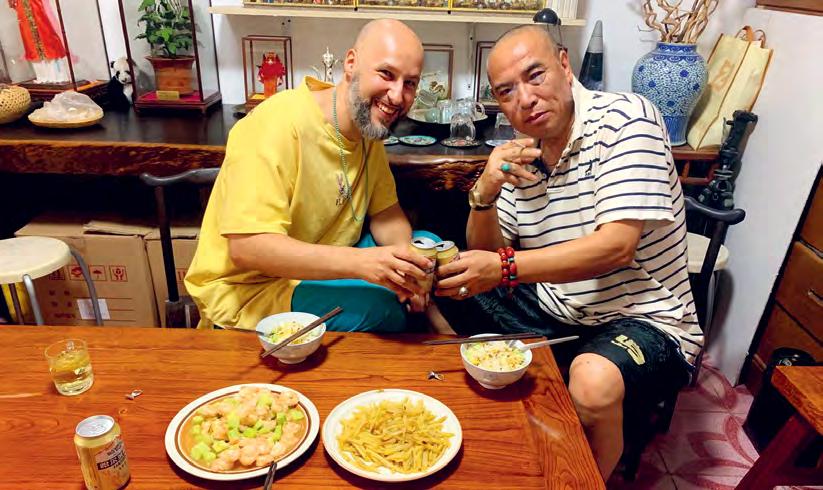

Our communication relied on smartphone translation apps, smiles and gestures. Though we shared no spoken language, we bonded through a love of grotesque objects and satire. But we also bonded through our mutual appreciation of Mariah Carey, rap music and R&B. During the first documentation session, Master Qiu Yísheng blasted Mariah’s album Honey five times in a row. And I loved it! In the following weeks he often played contemporary rap music while slowly working on his meticulous craft. He told me that his practice is so slow and

他常常在专注于精细工艺时播放当代说唱音乐。他告诉 我,他的创作节奏如此缓慢而细致,需要节奏强烈、充满 活力的音乐来调和能量:“我喜欢英文歌,虽然听不懂歌 词。歌词越听不懂,反而越觉得美。我需要快速的节奏, 那种反差能启发我。”这完全颠覆了中国传统手工艺人只 听笛声禅乐的刻板印象。

拍摄间隙,我们常一起去做些小小的“探险”。我们去拜 访了他两位朋友的工作室:一位是京剧脸谱大师,另一位 是北京剪纸传承人。我们探访了“鬼市”跳蚤市场:一个 每周举行的户外夜市,摊贩上的物件要靠买家的手电筒 光束才能看清。这营造出了一种迷人而戏剧性的阴森氛

围,仿佛物品成为舞台上的演员。我们还去了一家特别的 商店买了一只“会唱歌的蟋蟀”。

邱老师还常常为我做些美味佳肴,例如炒蟹、凉拌黄瓜。

有一次,我随他和朋友们在餐馆尝试了炸蚕蛹和臭豆腐。

他们半开玩笑地想“考验”我,但因为早已习惯法国奶酪 的气味,我吃得兴致盎然,反倒让整桌生日宴宾客大为 惊讶。

我笑着想起第一次见面的场景。而几个月后,我们在他家 中随性地打着赤膊工作。这是酷暑里北京中年男人的惯 常做法。没有拘谨,只有熟悉与自在。邱贻生先生慷慨地 向我敞开家门,与我分享他的艺术。我感念他的信任,也因 能够将这份弥足珍贵的民间遗产呈现给读者而激动万分。

需要说明的是,我并非想自称为毛猴领域的专家,本书也 不会对这种艺术形式及其不同传承人进行全面综述。本 书甚至并未收录邱贻生老师的全部作品。我与出版方选

择主要聚焦于他的当代组景,以此展现一位手艺人在技艺 巅峰时期的创作,通过精选的场景构建出一条观看路径, 而不是编纂一本完整的档案专著。

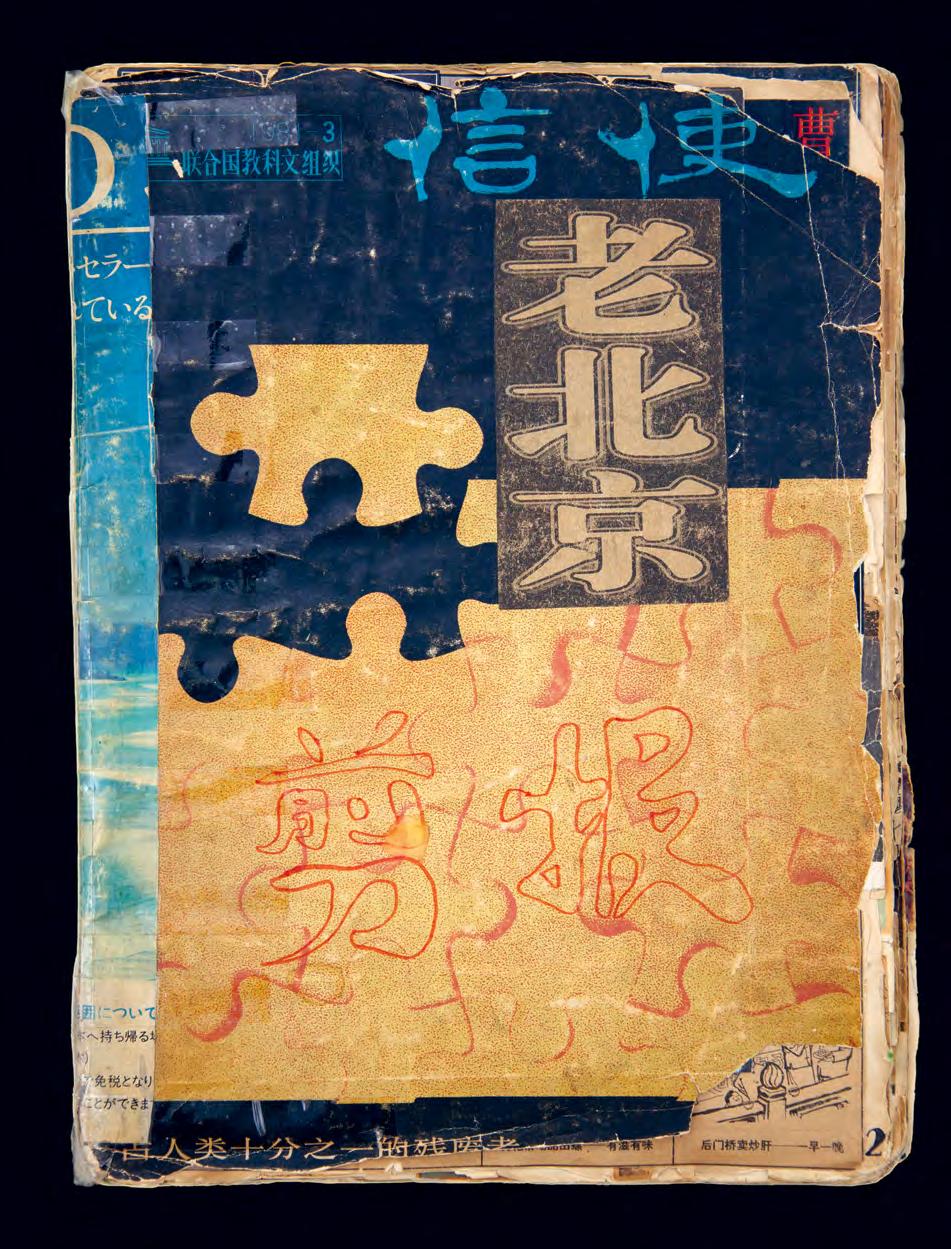

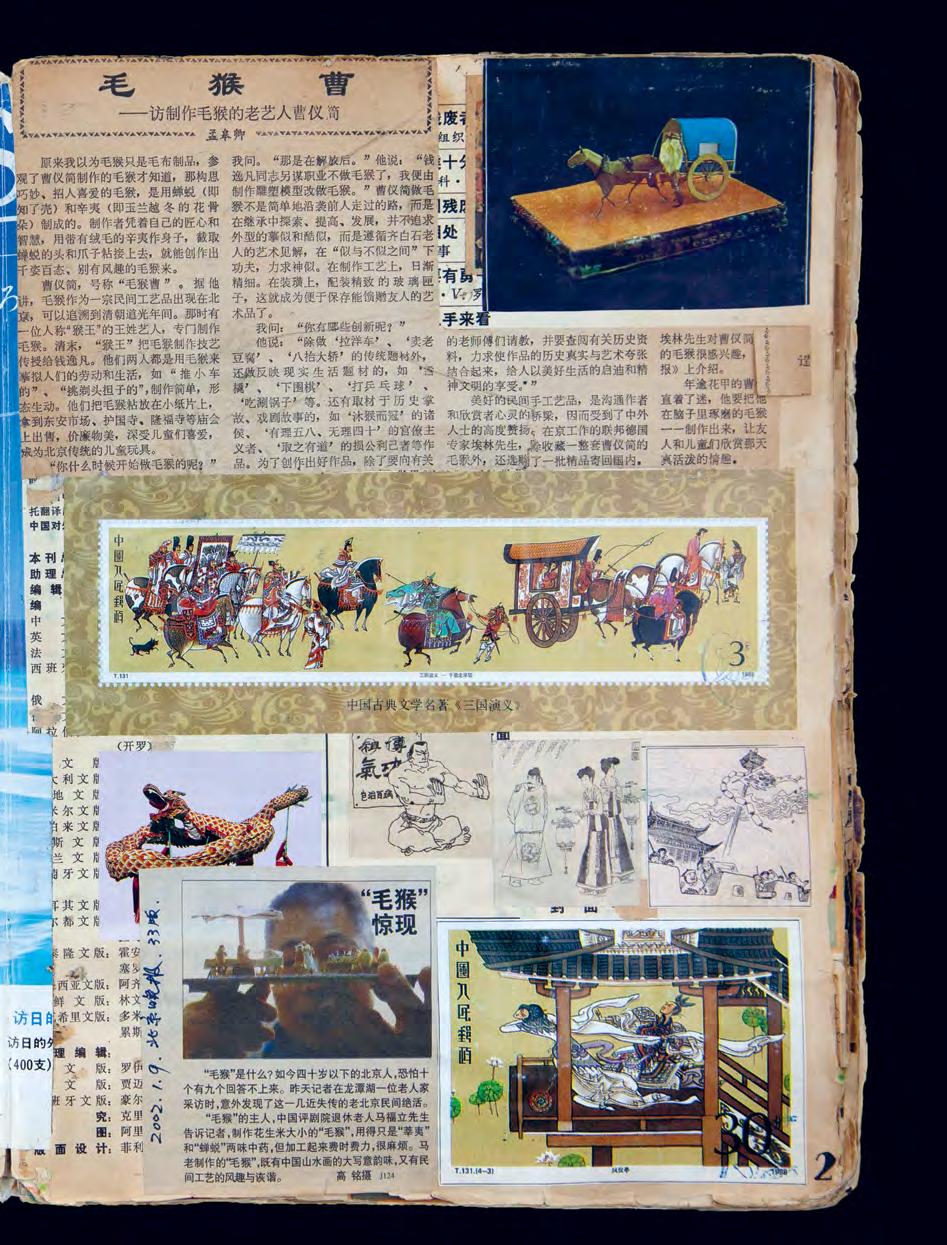

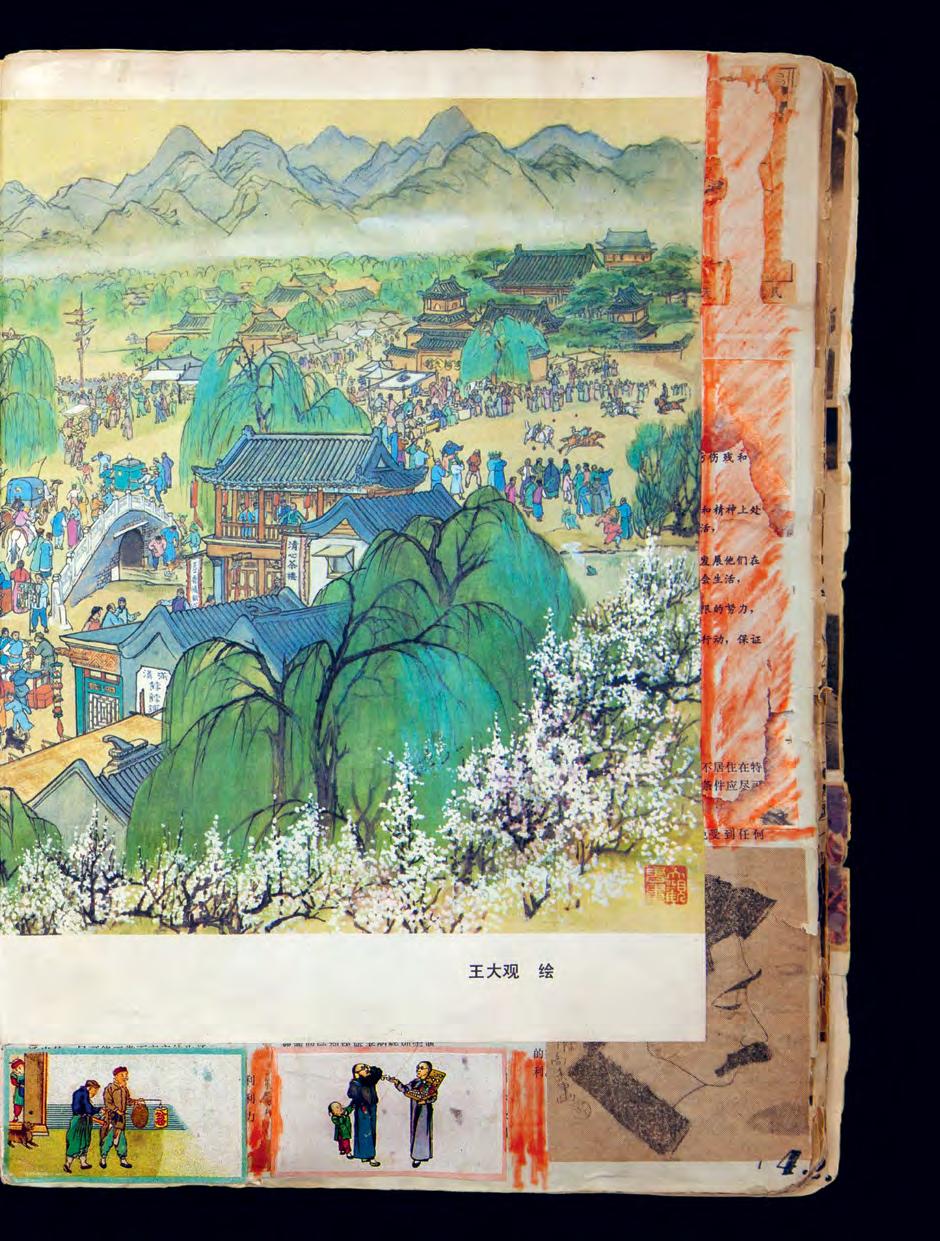

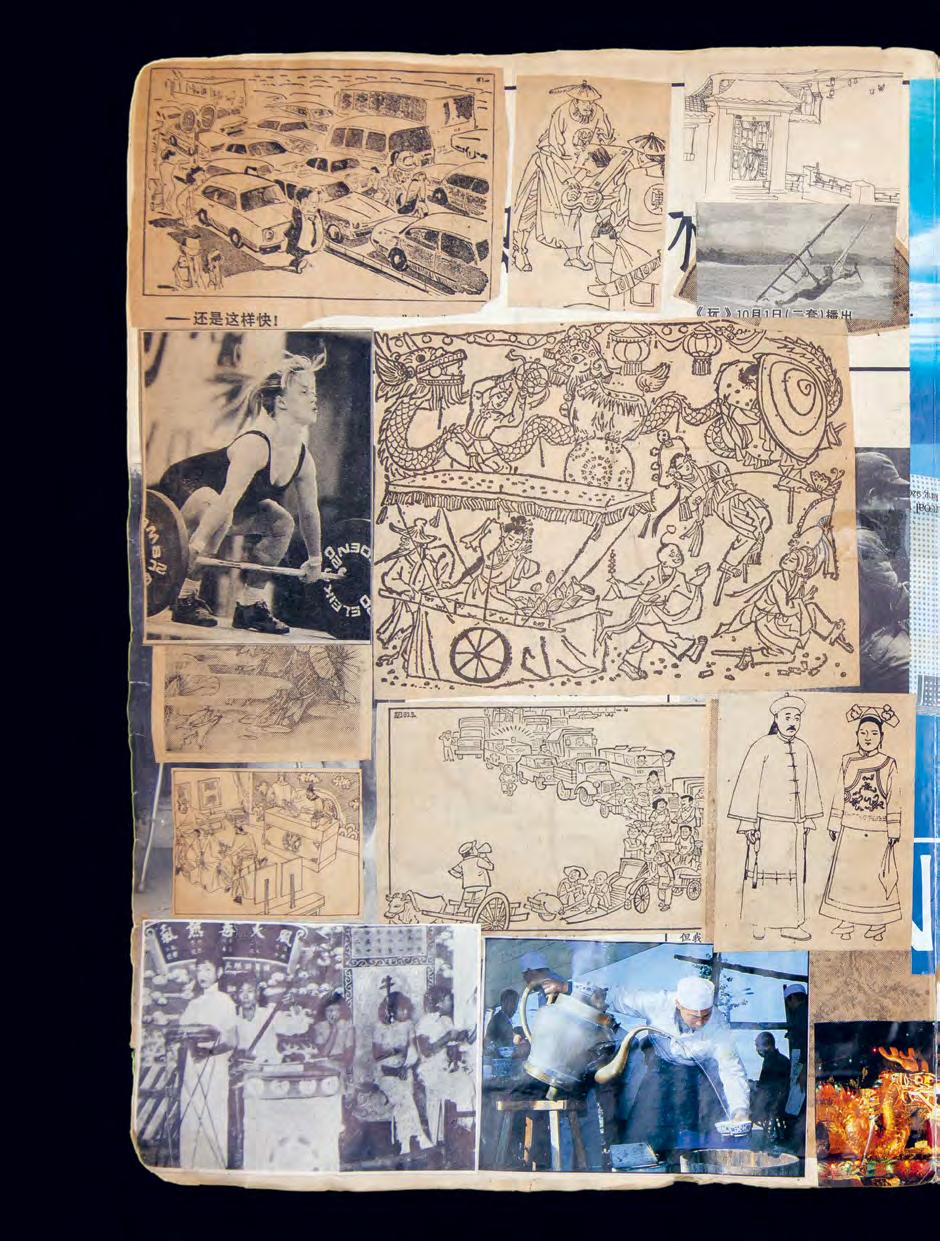

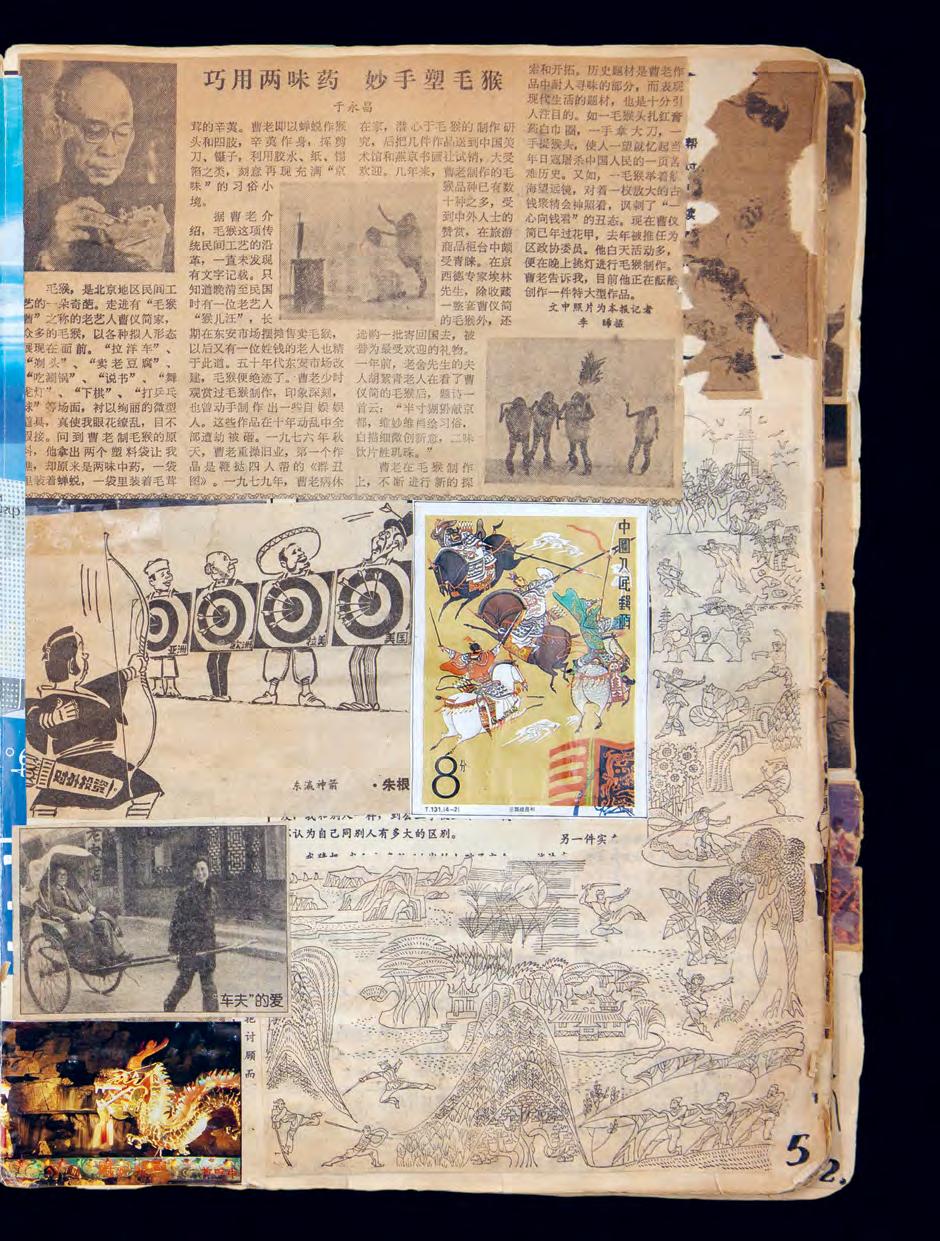

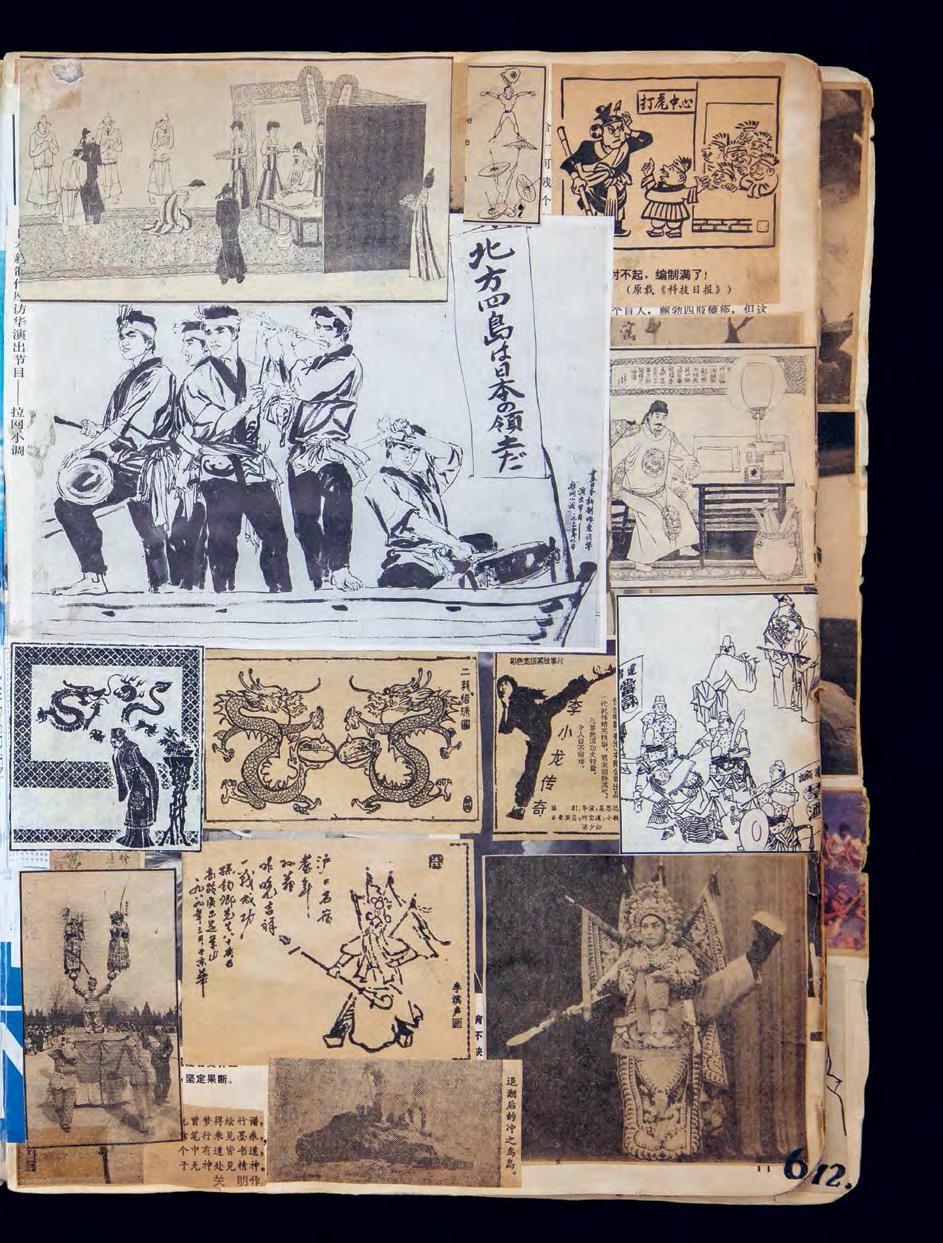

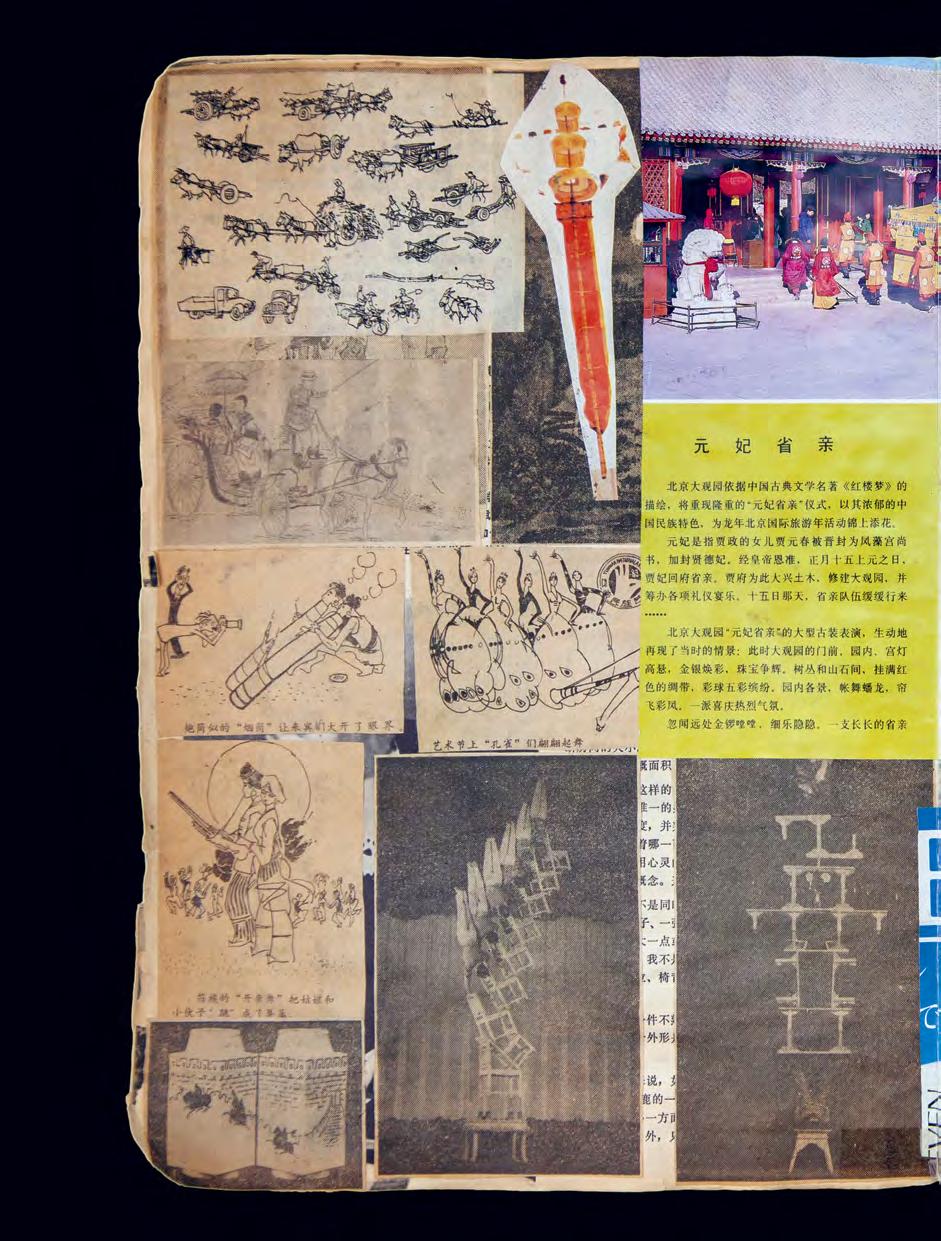

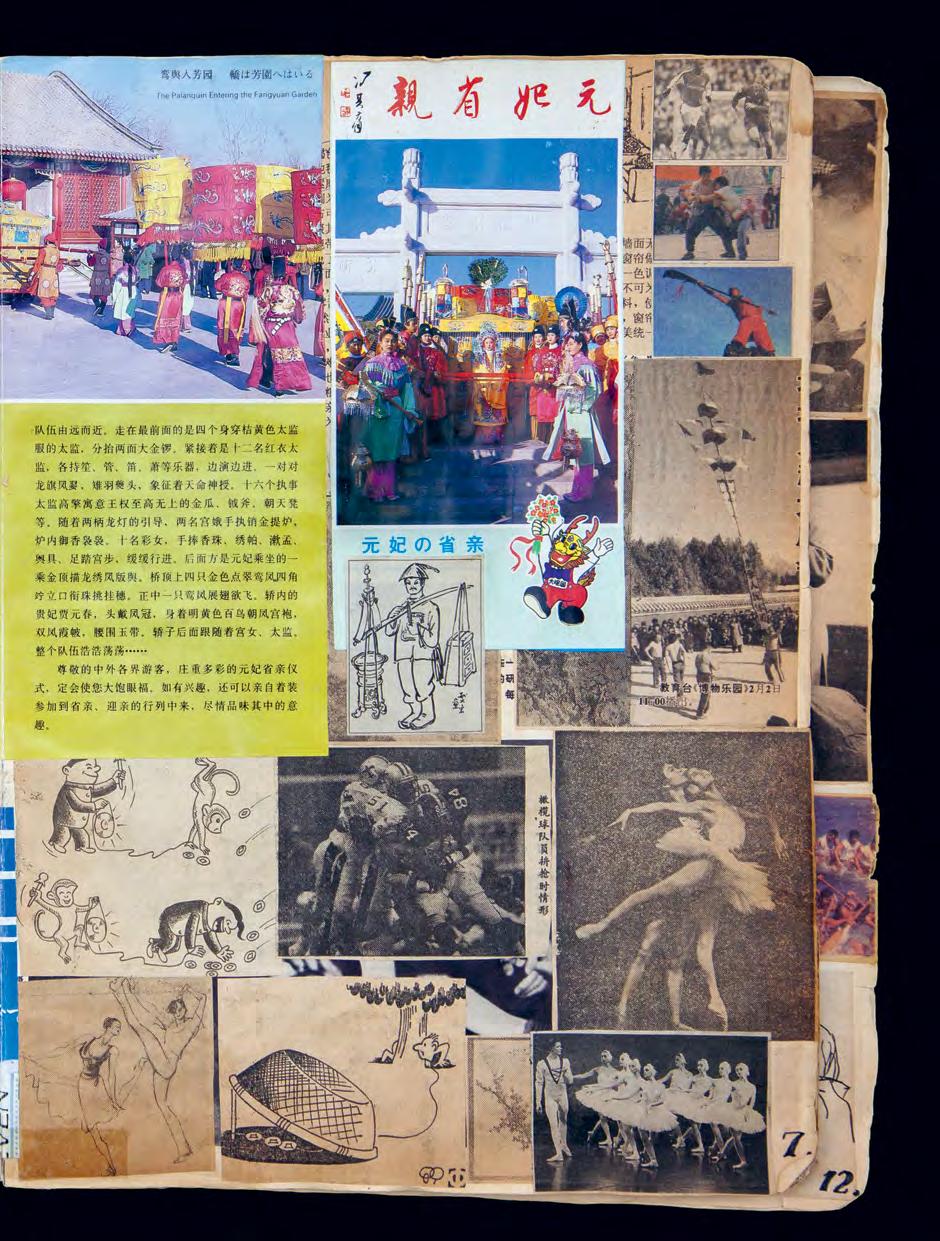

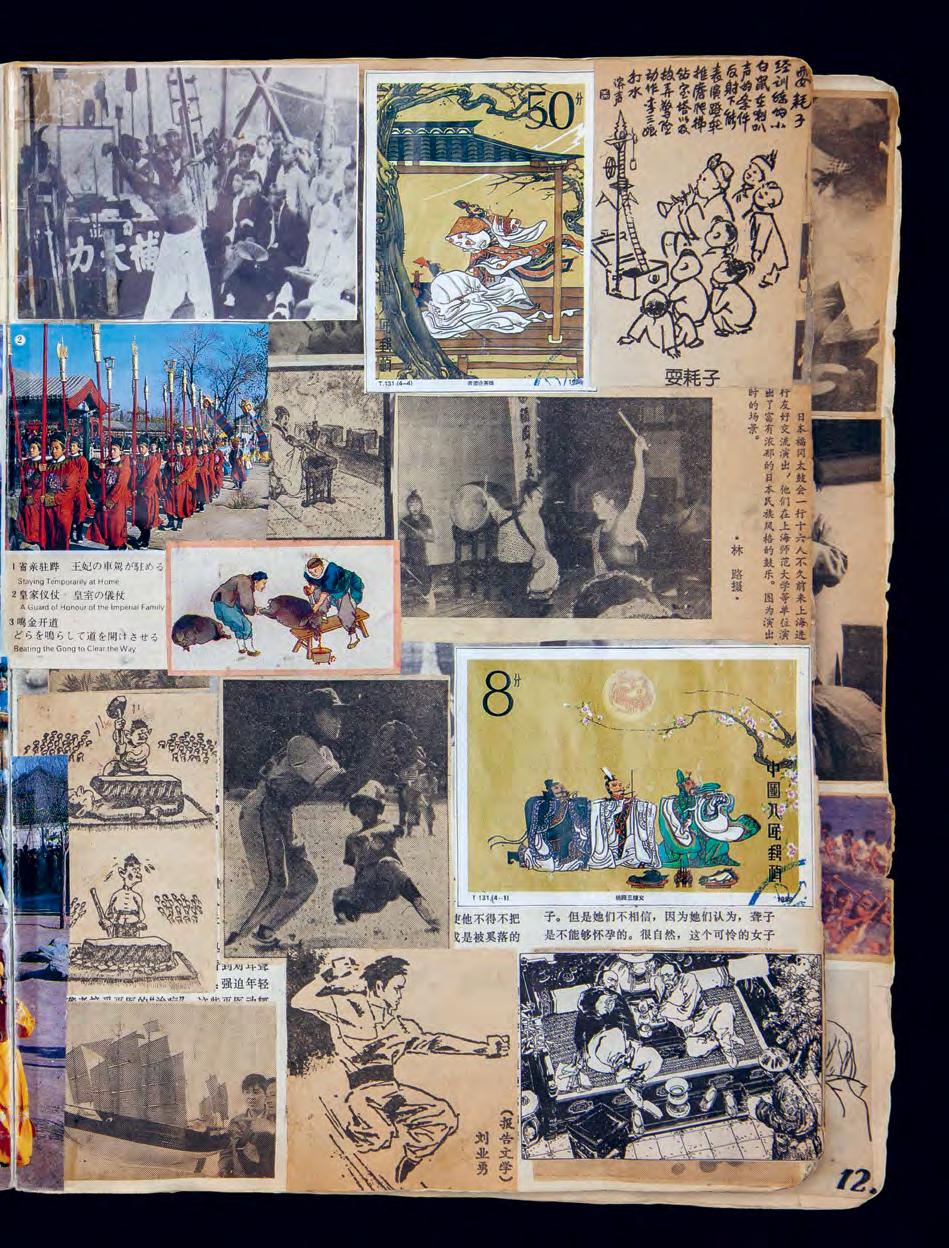

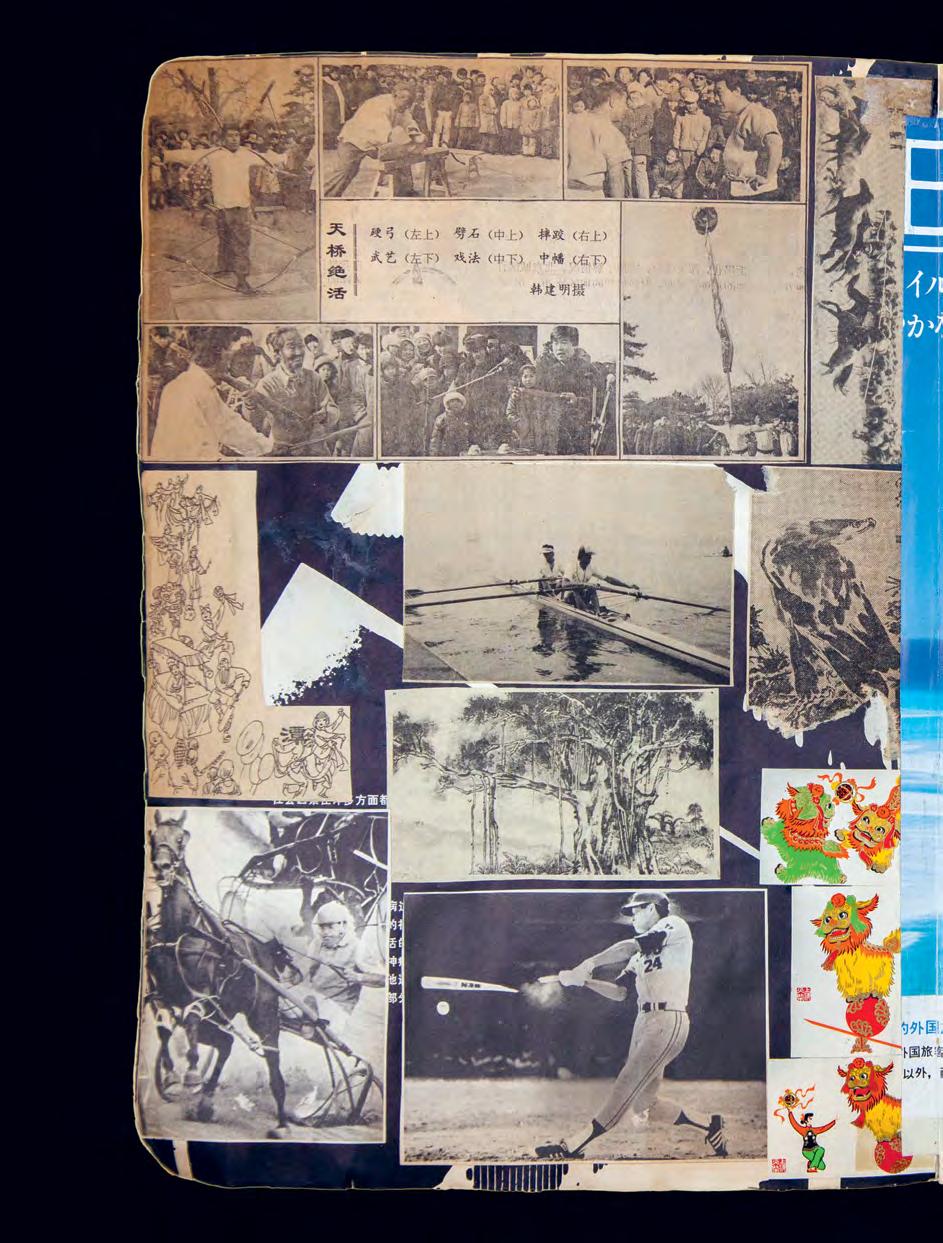

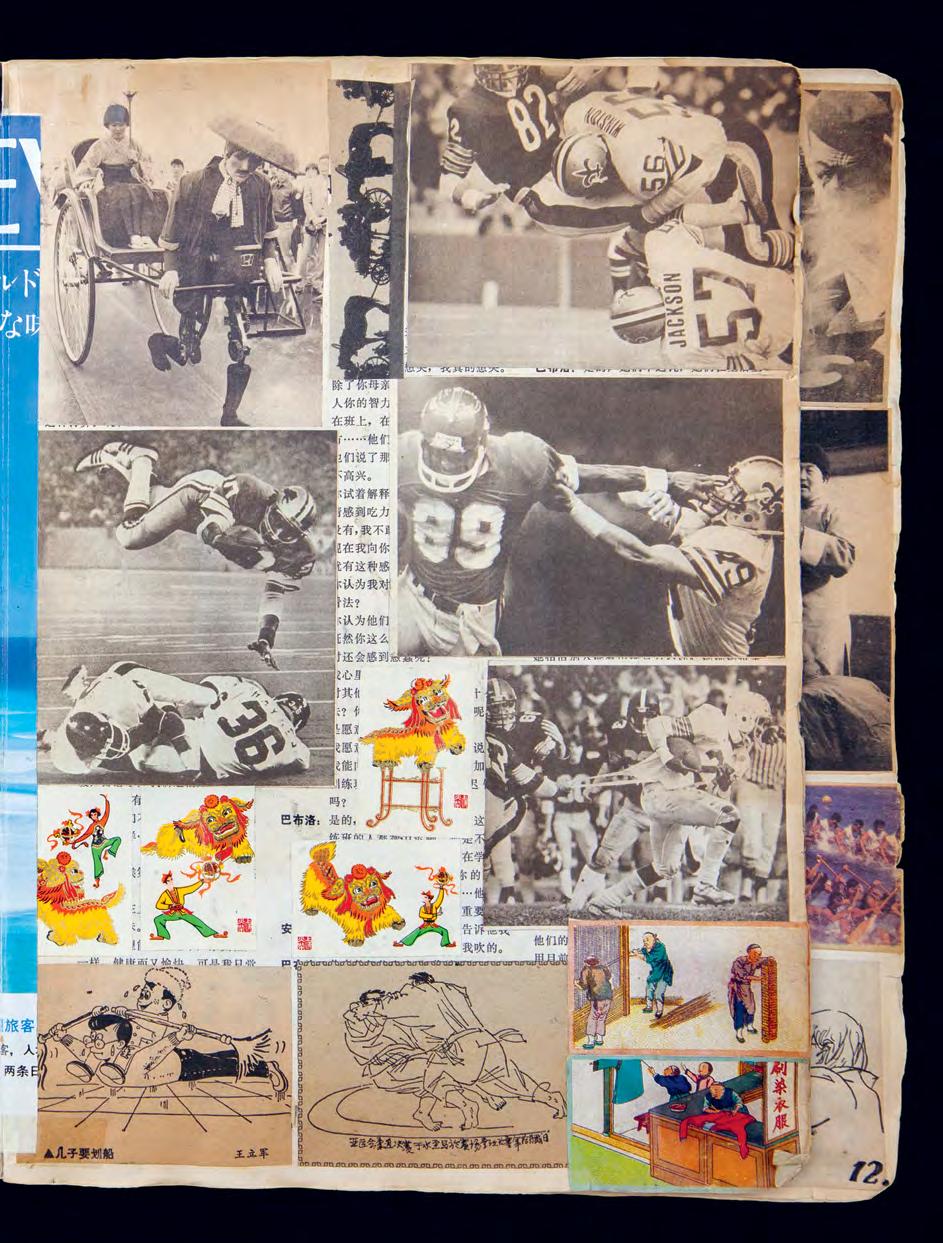

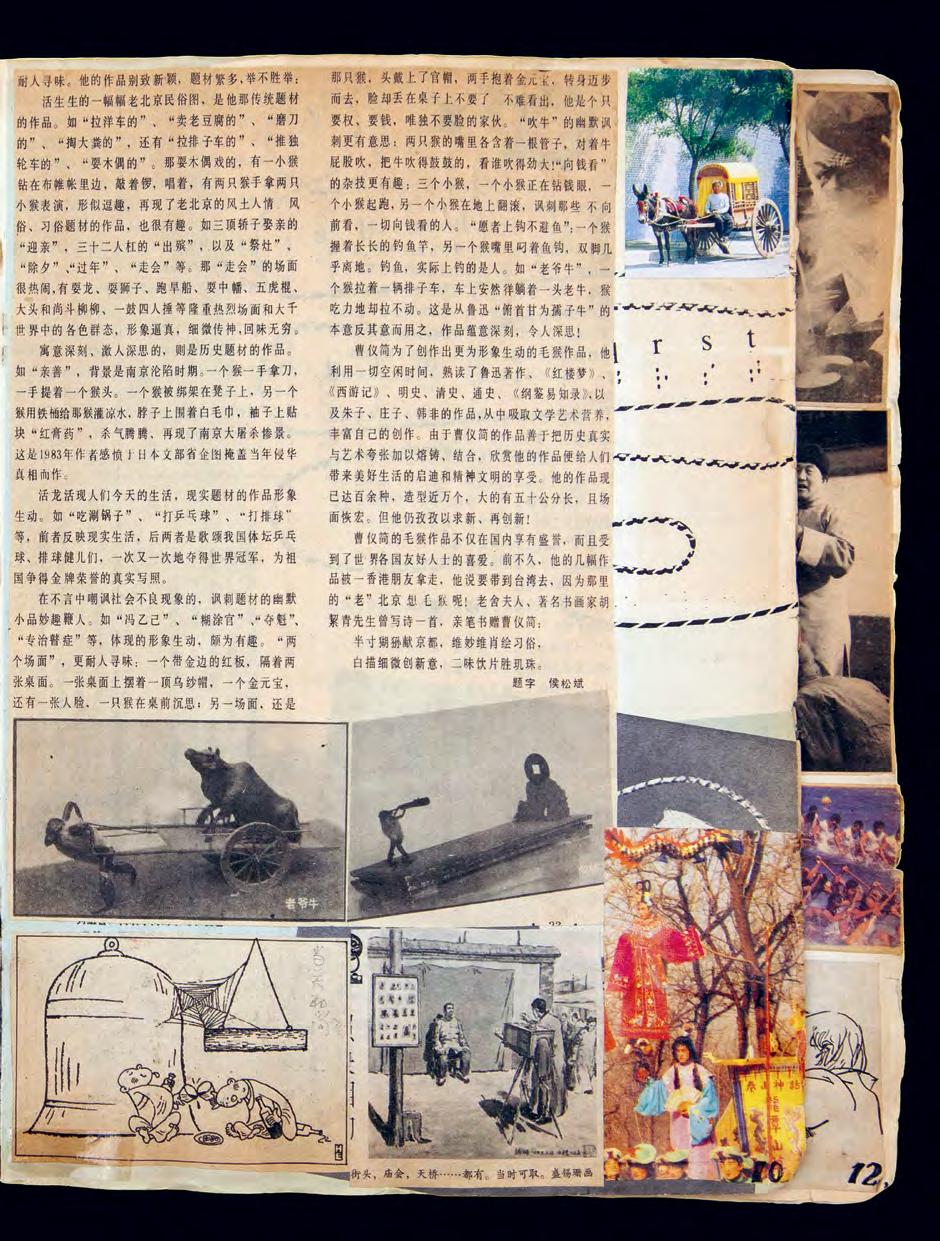

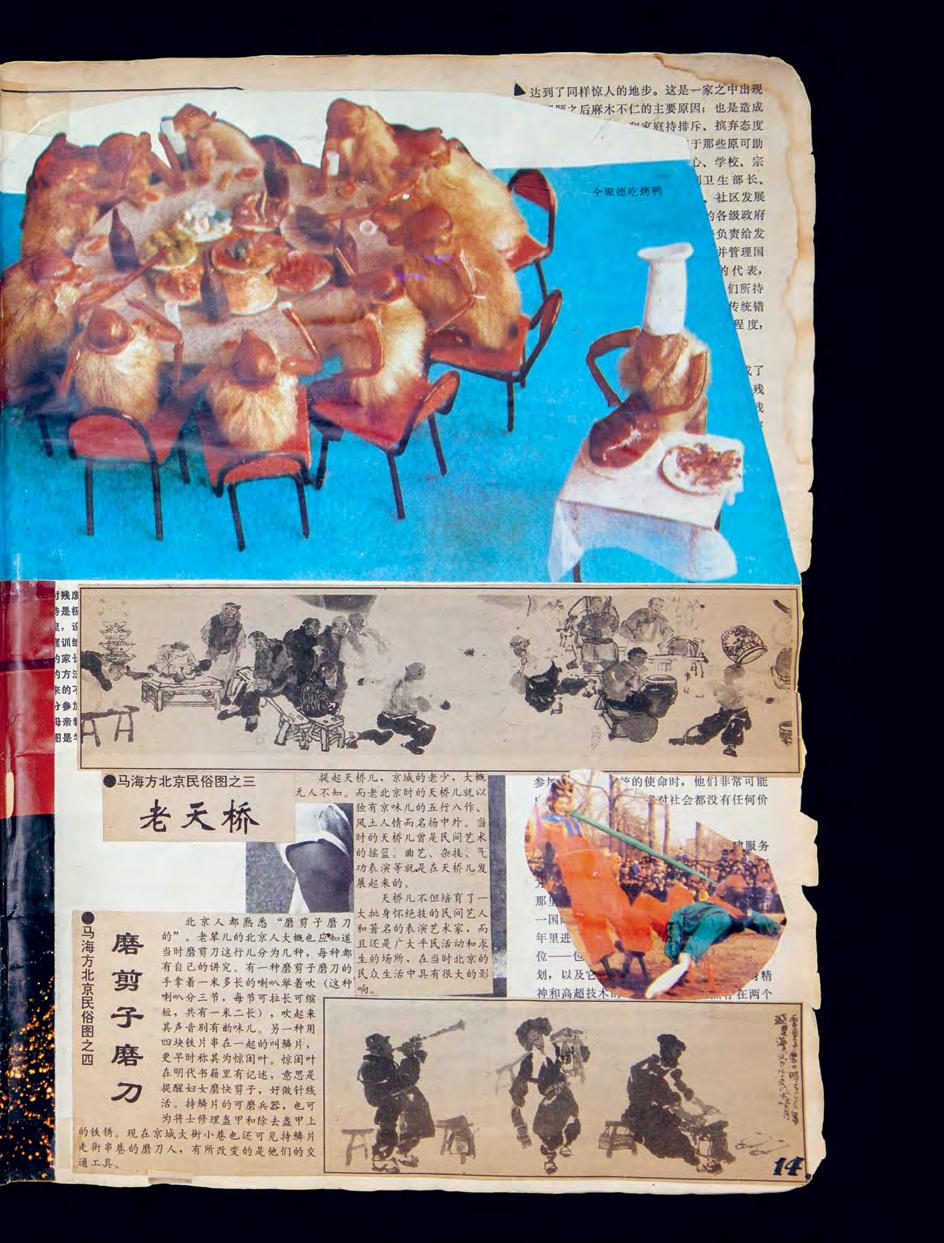

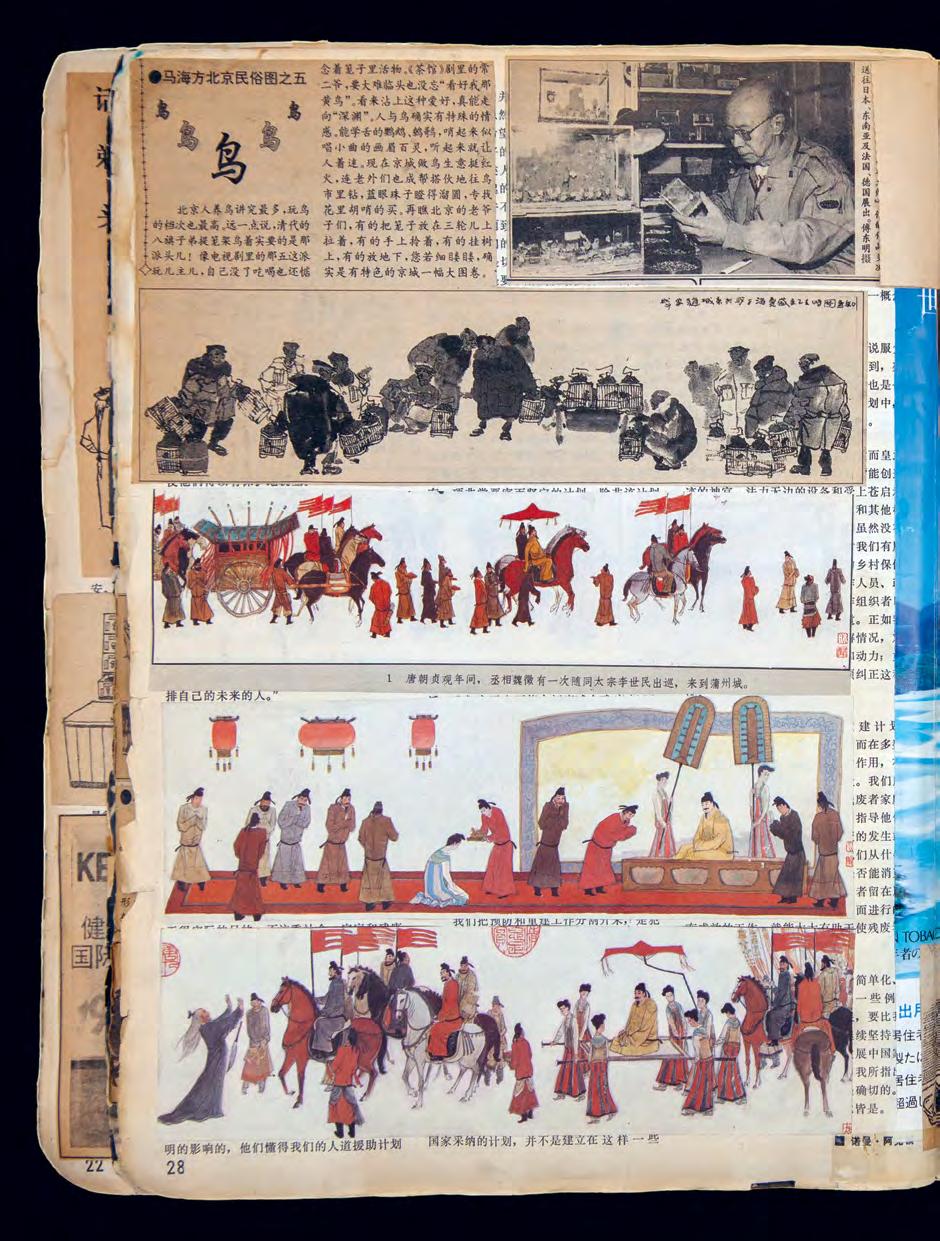

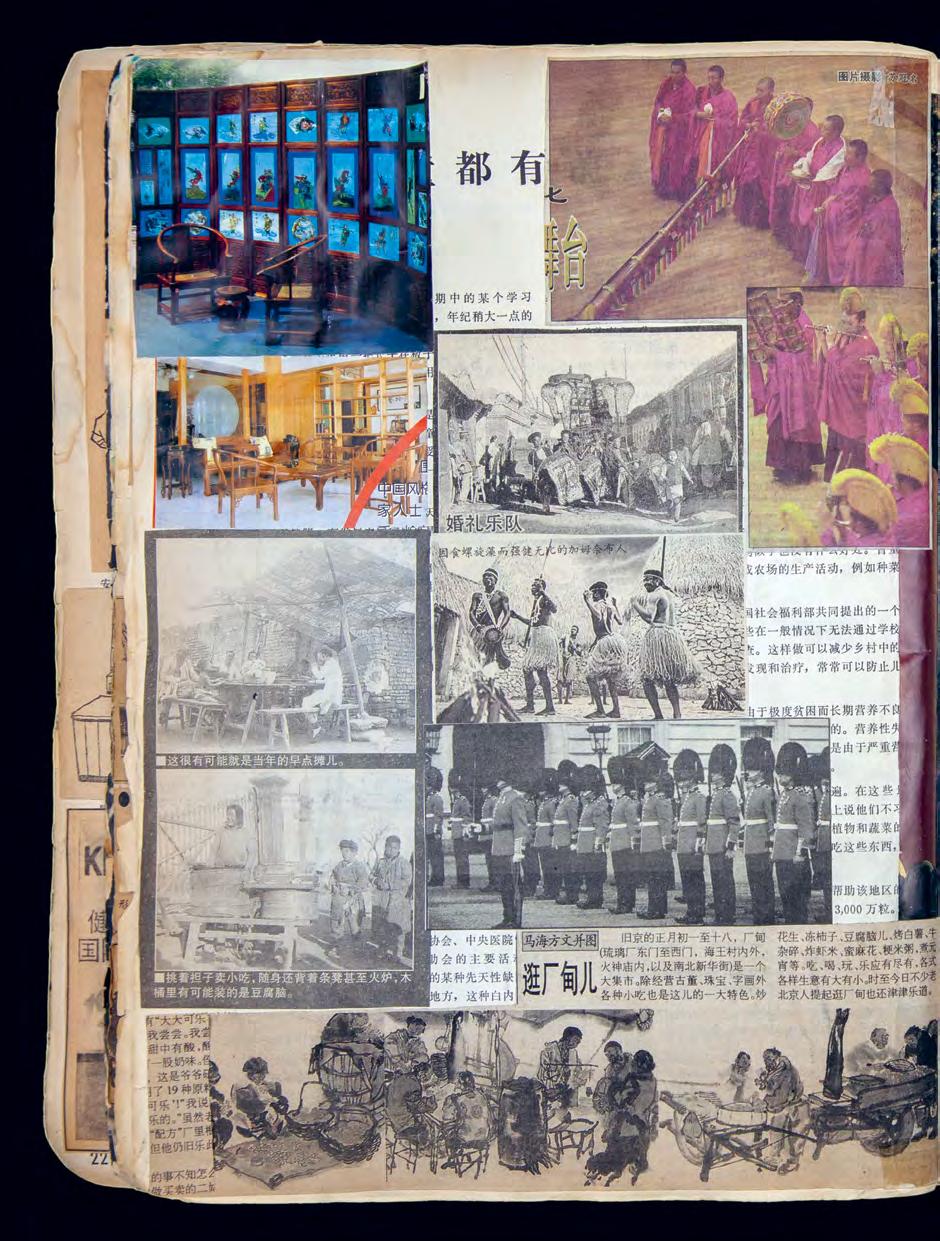

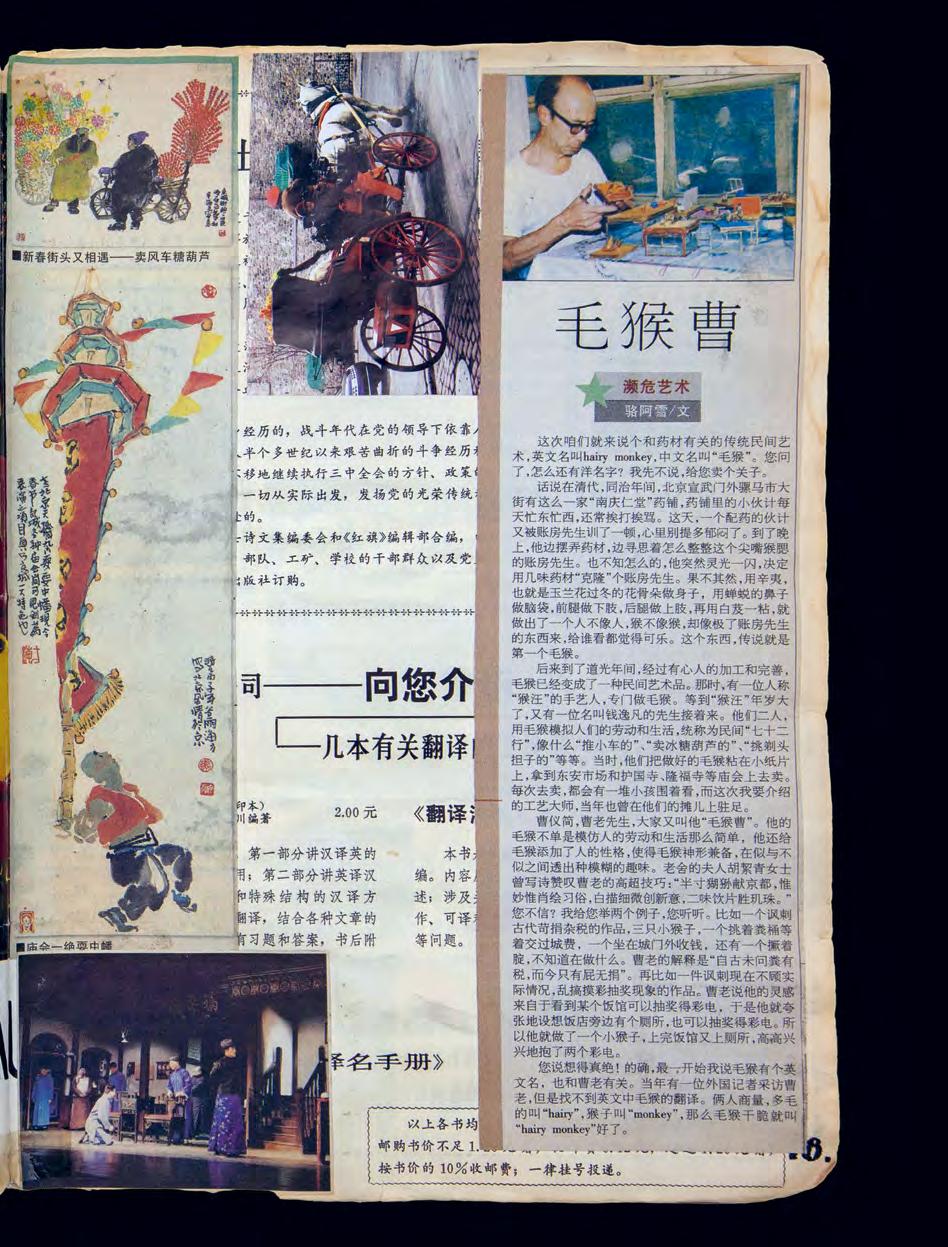

本书还收录了一份研究资料剪贴簿的影印本。这是邱贻 生老师多年的积累,其中包括大量关于毛猴大师曹仪简 的文章。正是通过这些拼贴所展现出的执着与热忱,曹 老师才在拒绝多年之后最终被打动,收他为徒。这本剪 贴簿既是宝贵的研究材料,也是一扇视觉窗口,带领我们 回到另一个时代。本书中的访谈部分进一步介绍了剪贴 簿的背景。

呈现被忽略的事物

在北京遇到的许多当代艺术家,其实都对毛猴并不熟悉。

造成这一现象的原因可能有许多,例如这门手艺的稀有或 是城市的体量之大。但我也想知道在所谓的高雅艺术的 圈子里,对民间艺术的轻视是否仍然在起作用。

在中国的文化历史里,文人艺术与民间艺术始终存在着 明确的区分。前者是士大夫阶层以诗文、书画、琴艺寄托 情感与修养的方式;后者则是由普通工匠或民间艺人创 造的实用或装饰性作品,强调技艺的精湛。这种根植于社 会身份与思想取向的差异,至今仍在无意识地影响着文 化从业者对不同艺术形态的理解与评判。类似的等级观, 同样在西方艺术体系中顽固地延续着。

而作为一个外来者,我以一种天真而好奇的目光看待毛 猴——不受既有文化语境的束缚;同时,作为一个试图打 破艺术门类边界的艺术家,我得以从全新的角度理解这 种艺术形式。对我而言,邱贻生老师的创作早已超越了通 俗意义上的“民间艺术”。我的朋友与合作者蔡昕媛,也 在本书的文章中进一步展开了这一思考。

作为一名视觉艺术家,我常常质疑在一个已经充斥着影 像、物件与内容的世界里,不断制造新东西是否真的有价 值。我并不总有强烈的生产欲望,而更愿意去凸显、欣赏

或重构那些被忽视的事物,尤其是那些可能在信息洪流 中消失而我们视而不见的对象。我的实践常常根植于挪

delicate that he needs loud, upbeat music as a way to balance his energy: “I love English songs even though I don’t understand them. The less I understand, the more beautiful it feels. I need fast rhythms. That contrast inspires me.” So much for clichés about Chinese traditional craft masters only listening to Zen flute music!

During photo shoot breaks we would go on small adventures. We visited the workshop of two of his friends, one of whom is a Chinese opera mask master and the other a Beijing paper-cutting artist. We explored the ghost flea market: a weekly outdoor night market where items are revealed through the light of a potential buyer’s flashlight. This creates a beautiful, gloomy, theatrical experience where objects seem to become actors on a stage. We went to a specialised shop to buy a singing cricket.9

Master Qiu Yísheng cooked me delicious meals of boiled crabs and spicy cucumber salad, crispy duck and Sichuan-style potatoes. We once ate fried butterfly larvae and stinky tofu at a restaurant with his friends. They were playfully testing me, but being used to French cheese, I gobbled up the stinky tofu easily, impressing the whole birthday party table!

As we both were casually working topless at his house, in the “tradition” of middle-aged men during hot Beijing summers, I had to smile, thinking of our first official meeting months earlier. Familiarity had set in, and no more formalities felt required. Qiu generously opened his home and shared his art with me. I am grateful for his trust and thrilled to share this incredible piece of Beijing’s folk heritage with you.

To be clear, I do not claim to be a specialist in the subject of máohóu, and this publication does not attempt to offer a comprehensive overview of the art form or its various masters. It does not even present the full body of Master Qiu Yísheng’s work. Instead, the publisher and I have chosen to focus primarily on his contemporary dioramas, showing the work of a master at the top of his craft, creating a journey through selected scenes rather than compiling a complete archival monograph. This publication also features

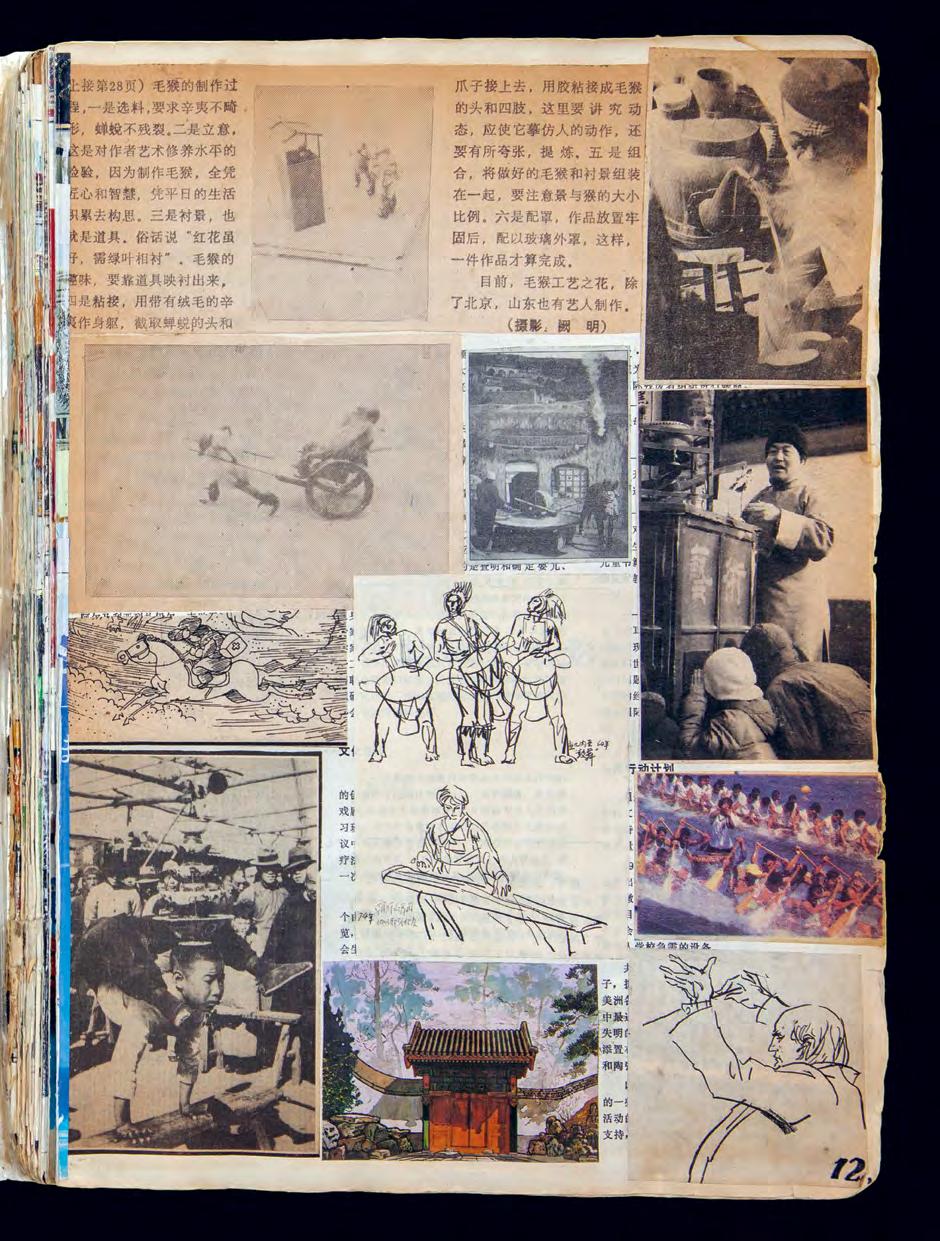

a facsimile of a research scrapbook that Master Qiu Yísheng compiled over many years, collecting articles on the work of the máohóu master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n. It was Qiu’s devotion to the craft, expressed through these collages, that ultimately persuaded Cáo, after years of refusal, to accept him as an apprentice. The scrapbook offers both valuable insight and a visually compelling window into another era. Additional context about this scrapbook can be found in the interview with Qiu included in this volume.

The máohóu art form was unfamiliar to many contemporary Chinese artists I met in Beijing. This may be due to several factors, such as the relative rarity of the craft and the vastness of the city. Yet I wonder whether a certain disinterest in folk art within high-art circles also plays a role.

In Chinese cultural history, distinctions have often been drawn between literati art — the art of scholar-officials, who integrated poetry, calligraphy, painting and music as expressions of personal sentiment — and folk, craft or popular traditions, which tend to emphasise skill and technique. These differences, rooted in the social status and intellectual orientation of the respective makers, still linger today, often unconsciously, in the ways cultural practitioners perceive and value different art forms. Similar hierarchies persist in the Western art world as well.

As an outsider with a naively curious eye, unbound by Chinese cultural references, and as an artist who seeks to dismantle the boundaries between categories, I was able to see the máohóu in a new light. To me, Master Qiu Yísheng’s work transcends the narrowing label of folk art. My dear friend and colleague Augustina Cai expands on this idea, among others, in her essay included in this publication.

As a visual artist, I often question the value of continuously adding material to a world already saturated with images, objects and content. I don’t feel a constant urge to produce, but rather want to highlight, appreciate or reframe overlooked

用与采样:通过 DIY改造与拼装,让俗气的装置或奇特 的小物件成为讽刺的、颠覆性的装置、影像或雕塑中的 角色。

我对毛猴艺术的迷恋,正是我个人世界的自然延伸。它 融合了色彩斑斓、可爱与游戏性的同时,又带有怪诞与批 判,这种张力深深触动了我。从这个意义上说,本书既是

我对邱贻生先生作品的由衷致敬,也可以看作是一本艺术 家书,回应了我实践中反复出现的一些主题:社会讽刺、 怪诞感、消费主义、贪欲与旺盛的活力。书中的许多毛猴 都荒唐地沉醉于过度之中!

微缩化

偶尔,邱贻生老师会延展乃至突破毛猴创作的传统规范, 把实物大小的器物直接融入场景。这种越界的行为造就 了我最钟爱的一件作品:毛猴们抽着微型香烟,同时坐在 真正的香烟上。那种比例的错置令人瞠目,让人联想起乔 纳森·斯威夫特《格列佛游记》的荒诞反转。另一组场景则 描绘了毛猴化身为计算机病毒与杀毒软件,它们以蒸汽朋 克海盗的形象在一张 CD-R 光盘上厮杀。

尽管我多以旁观者的身份记录着,但偶尔也会放纵自己, 添上几笔。我把真实物件放进场景,让它们像故障般荒谬 地闯入画面。这些附加物随手取自邱老师家中,在画面中 像坠落人类世界的异星残骸。尺度的强烈对比恰恰凸显 了毛猴作品超凡脱俗的缩微技艺。一颗樱桃砸在乒乓球 桌上,一节 AA 电池出现在古玩市场,一根烟斗横在篮球 场上,或者我的拇指悬在《最后的晚餐》之上。邱老师知 晓这些小插曲,并慷慨给予我充分的创作自由。

这些充满趣味的尝试让我开始反思“微缩”本身的意义与 力量。我虽非学者,却成长于思想与文化典故交织于日常 的环境。我的父亲是一位知识分子,总能在表面毫不相干 的事物间穿引出令人惊讶的关联。这塑造了我自由联想的 思维方式,也引出了我接下来的思考。我曾读过让·鲍德里 亚的一段话,与毛猴的观念颇有相关性,尤其是在当代中 国崛起为世界大国的背景之下。他在《物体系》中谈到电 子产品时写道:“在一个以扩张、延伸与空间化为特征的 文明里,微缩化似乎成了一种悖论。”

借由毛猴,我逐渐明白,在这个令人窒息的快节奏世界 里,微缩艺术所蕴含的静谧之力。这些微小的造像以极致 的细腻与精确,讲述着人类故事与社会批评。它们邀请我

objects, especially those at risk of vanishing in the flood of information to which we’ve grown numb. My practice is rooted in reappropriation and sampling. Through DIY modifications and assemblages, tacky gadgets and odd curiosities become actors in satirical, subversive installations, films and sculptures.

My fascination with the art of máohóu feels like a natural extension of my world. Its fusion of the colourful, the cute and the playful with the grotesque and the critical resonates deeply with me. In that sense, while this book is a heartfelt tribute to the work of Master Qiu Yísheng, it can also be seen as an artist’s book that touches on some of the recurring themes in my own practice: social satire, the uncanny, consumerism, gluttony and exuberance. So many of these hairy monkeys are obnoxiously drunk on excess!

On a few rare occasions, in a move that stretches, or even breaches, the traditional rules of the art form, Qiu has incorporated full-sized objects into his tableaux. This transgressive act resulted in one of my favourite dioramas: it features monkeys smoking miniature cigarettes while sitting on real ones. The scale illusion is mind-boggling, a comic inversion reminiscent of Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift. Another tableau shows máohóu computer viruses and antiviruses battling as steampunk pirates atop a CD-R.

Although documenting the work primarily as an observer, I allowed myself a few cheeky moments. I placed real-life objects into some of Qiu’s scenes, creating glitchy, absurd intrusions. These additions of items found randomly around his home appear in the images as crashed alien objects from the human realm, emphasising through their contrasting scale the extraordinary miniaturisation of his work. A cherry lands on a ping pong table, an AA battery shows up at an antique market, a pipe lies across a basketball court, or my thumb hovers over the Last Supper. Qiu was aware of these interventions and gave me his blessing to envision the book with full creative liberty.

These playful experiments led me to reflect on the meaning and power of miniaturisation itself. I’m not an academic, but I grew up in an environment where ideas and cultural references were part of everyday life. My father was an intellectual who often made unexpected connections between seemingly unrelated topics. This inspired a kind of free association thinking which leads me to the following point. I once came across a quote that struck me as relevant to the idea of the máohóu, particularly in the context of China’s rise as a global power in contemporary times. Jean Baudrillard, writing about electronics in The System of Objects , observed: “To miniaturise may seem paradoxical in the context of a civilisation of extension, expansion and spatialisation.”

Through máohóu, I came to understand the quiet strength of miniature art in today’s overwhelming, fast-paced world. These tiny figures express human stories and social critique with immense care and precision. They ask us to slow down and to pay attention. In the age of industrialisation, where many feel detached from the handmade and from local traditions, Master Qiu Yísheng and his peers offer a unique counterbalance by embodying regional characteristics, personal expression and historical depth. Their work as artists becomes a gentle yet radical gesture reminding us to reconsider what we value, what we call beautiful and what we choose to preserve.

Qiu regularly teaches the basics of the máohóu craft to children. One day, as he guided me through the process of making my first hairy monkey, he said that if I wanted to, I could start a máohóu tradition in Europe. The tradition, he explained, is about reflecting the habits of our time. It is not just a commentary on Chinese society, but ultimately a meditation on the human condition. This, in turn, reminded me of when my sister Elisa came to visit me in Beijing. At a hostel during her travels, she remarked, “How nice that you have fish! Why are there often aquariums at the entrances to establishments?” Someone responded, laughing, “We don’t care about the fish. For good fortune, water needs to keep moving; we just don’t want the water to stand still.”

— Simon Wald-Lasowski

们放慢脚步,学会专注。在工业化时代,许多人已经与手 工劳动、本地传统渐行渐远。而邱贻生先生和他的同道 之人,恰恰提供了独特的平衡:他们的作品承载着地域特 色、个人表达与历史厚度。在这个意义上,他们作为艺术 家的实践成为一种温和却不失激进的提醒,促使我们重 新追问:什么值得珍视,什么才是真正的美,以及什么值 得保存。

邱老师常面向儿童教授基础的毛猴制作。有一天,在指导 我制作我的第一个毛猴时,他说,如果我愿意,完全可以 在欧洲建立属于自己的毛猴传统。他解释说,这项传统的 意义在于反映我们当下的时代特征。它不仅仅是对中国社 会的评论,更终究是一种关于人类境遇的沉思。这让我想 起我妹妹埃莉莎来北京看我时,在路途中的一家旅馆里, 她问到:“你们这里养鱼真好!为什么很多店铺门口都会 放水族箱?”有人笑着回答:“我们并不在意鱼。为了吉 利,水必须保持流动,我们只是不愿让水停下。”

——西蒙·瓦尔德-拉索夫斯基

注释

1 邱贻生(1961 年 2 月 7 日,出生于北京)。关于其生平背景,请参阅 本书所附的访谈。

2 激发研究所(the Institute for Provocation, IFP)是一家位于北京的 独立艺术机构与项目空间,成立于 2010 年。通过理论研究和艺术实 践的结合,激发研究所旨在以合作的方式联结跨领域的知识,激发 文化交流与生产。基于对独立艺术机构在社会中的动态性的思考, 激发研究所发起并支持多种形式的实践活动,包括驻地、项目研究、 研讨会、展览、工作坊、出版等。我在 IFP 的驻留得到了荷兰蒙德里 安基金会(Mondriaan Fund)的慷慨资助,该基金会是关注荷兰视 觉艺术与文化遗产的公共基金。

3 胡同是北京特有的狭窄街道或小巷,被许多本地人(尤其是老一 辈)视为首都民俗文化的家园。自 20 世纪中期起,许多胡同被拆除 以修建新道路与建筑。但近年来,胡同逐渐被列为保护地,以保存这 一中国文化遗产的重要组成部分。

4 数月之后,在驻留结束时,我带着仿佛北京已成为“第二故乡”的感 觉离开。我很幸运地收获了许多真挚的友谊,开始能与当地人通过 肢体动作无拘束地开玩笑。六个月的时光如同一生,我常常困惑自 己真正的归属在哪里。如今回望这一经历,我满怀温情与感激。

5 关于起源故事存在不同版本。有的版本认为讽刺对象是药铺掌柜, 另一些版本则是账房先生。

6 到 20 世纪 60 年代,毛猴工艺几近失传。曹仪简大约八九岁时, 东安市场有一位被称为“毛猴汪”的小贩在卖毛猴。曹被深深吸引, 一看就是几个小时。回到家后,他开始模仿所见,不到几个月便熟练 掌握,作品几乎与“毛猴汪”的出品难分伯仲。然而,此后数十年, 由于种种原因,曹仪简未能全身心投入毛猴创作。直到20世纪70年 代中期,他已年过六十,才真正开始专注于毛猴艺术。他不仅继承了 传统技艺,还不断创新,拓展了毛猴的艺术表现。他的猴子形象栩 栩如生、充满魅力,很快博得人们的喜爱。他的毛猴题材广泛,涵盖 古今:卖冰糖葫芦、烤串、操作拉洋片、拉黄包车、街边理发、踢足 球与打乒乓球、吃火锅、跳迪斯科等等。

7 外骨骼(exoskeleton)是昆虫坚硬的外部结构,用来支撑与保护身 体。蝉以若虫的形式自地下钻出,在蜕皮后成长为成虫,长出翅膀与 完整的身体。昆虫不会通过伸展皮肤来变大,而是在旧骨骼下生长 新的外骨骼。所谓蝉蜕,在科学上称为“蜕皮壳”(exuviae),即蝉从 若虫阶段蜕变为成虫后留下的外壳。

8 据央视网(CCTV)200 6 年2 月 10 日发布的一篇网络文章。

9 早在公元前 500 年,文人就已赞美蟋蟀的鸣声。后来,富人开始将它 们养在笼中。至唐代,宫廷妃嫔便会豢养这些鸣虫来排解寂寞。历 史上,爱蟋蟀的人们会将其安置在专门雕刻的葫芦中,或由竹子、金 属、檀木等制成的精美笼具中。如今,看到年长的老人自豪地在城市 广场携带他们的“会唱歌的蛐蛐”,仿佛置身一场声音的决斗,这又 是一个地方传统在现代中国仍然鲜活延续的美好例证。

Notes

1 Master Qiu Yísheng 邱贻生 (born 7 February 1961 in Beijing). For additional biographical context, see the interview with him later in the book.

2 The Institute for Provocation (IFP) is a Beijing-based independent art organisation and project space founded in 2010. Combining theoretical study with artistic practice, IFP aims to foster cross-disciplinary knowledge and stimulate cultural exchange and production through a collective approach. IFP organises and supports various activities, including artist residencies, research projects, discussions, exhibitions, workshops and publications, devoting attention to the evolving relationship between independent art spaces and society. My time at the IFP was generously supported by the Mondriaan Fund, which is the public fund for visual arts and cultural heritage in the Netherlands.

3 Hutongs are narrow streets or alleys typical to Beijing and recognised by many locals (especially the older generations) as the home of the capital’s folk culture. Since the mid-20th century, many hutongs have been demolished to make way for new roads and buildings. More recently, however, hutongs have been designated as protected sites in an effort to preserve this aspect of China’s cultural heritage.

4 Months later, at the end of the residency, I left Beijing feeling as if it had become a second home. I had been fortunate to form many meaningful friendships and felt no restraint in playfully joking with locals through gesticulations. Six months felt like a lifetime, and I often found it confusing to remember where my life truly belonged. I look back on this experience with great tenderness and appreciation.

5 There are variations in the origin story. Some versions name a despotic apothecary shopkeeper (掌柜), others an oppressive bookkeeper/accountant ( 账房先生)

6 By the 1960s, máohóu craftsmanship was nearly extinct. When Cáo Yíjia ̌ n was about eight or nine years old, a street vendor known as “Monkey Wang” sold máohóu figures at the Dong’an Market in Beijing. Cáo was captivated and would watch for hours. After returning home, he began imitating what he had seen. Within a few months, he had mastered the skill, and his work became nearly indistinguishable from Monkey Wang’s. However, for decades, for various reasons, Cáo couldn’t fully commit himself to the máohóu craft. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s, after he had turned 60, that he found the time to focus on it. Not only did he inherit traditional techniques, but he also innovated and expanded the artistic expression. His monkeys were vividly lifelike and charming, easily winning people’s affection. The themes of his máohóu works were diverse, spanning past and present: monkeys selling candied hawthorns, grilling kebabs, operating magic lantern shows, pulling rickshaws, giving roadside haircuts, playing football and table tennis, eating hotpot and disco dancing.

7 An exoskeleton is a hard outer covering that helps support and protect the insect. Cicadas emerge from underground as nymphs, a juvenile stage in their life cycle. Beneath their skin, they grow their wings and adult body. Insects do not stretch to enlarge; instead, they grow a new exoskeleton beneath the existing one. The shed skins, scientifically called “exuviae”, are what remain when the insect molts from the nymph stage into adulthood.

8 According to a CCTV article published online on 10 February 2006.

9 Writers celebrated cricket songs as early as 500 BCE. Later, the wealthy began keeping crickets in cages. As early as the Tang dynasty, concubines in the palace kept these sound-producing insects as companions to ease their loneliness. Historically, cricket lovers housed their pets in specially molded gourds or elaborately crafted cages made of bamboo, metal or sandalwood. Watching elderly men proudly carrying their singing crickets in city squares felt like witnessing a charming battle of sounds, another beautiful example of how local traditions continue to thrive in modern China.

The following text is transcribed from a recorded conversation between Master Qiu Yísheng 邱贻生 and Simon Wald-Lasowski, with live translation support from Augustina Cai. The conversation took place in Beijing on 17 June 2019 and has been edited for clarity and readability.

Simon: During our conversations you mentioned making things by hand since childhood. What did you create before discovering the máohóu?

Qiu: I started doing handicrafts when I was really young, around four or five years old. I enjoyed making children’s toys on my own. As I grew older, working with my hands came naturally. I used string to make slingshots and, later, carved replica guns from wood. That was during middle school, around fifth grade. I loved experimenting with new projects; it gave me a sense of pride, and the results were quite nice. Friends would ask me to create items for them, and sometimes they’d even give me little rewards in return.

Later, in middle school, I became interested in painting. I was curious about different art movements and wanted to explore them. I experimented with different styles: copying work, trying my own versions and following methods I’d read about. But since I was self-taught, without a teacher’s guidance, my work had its flaws. Real painting requires a holistic understanding. Around 1982 or 1983, I made a more serious decision to really pursue painting. I wanted to break through and achieve something meaningful.

By 1986, I had become particularly interested in oil painting. I went to visit my brother, whose friend was planning to apprentice with a master. I wanted to do the same. His friend was a very skilled oil painter. But something unexpected happened, a pleasant surprise, you could say. Suddenly, I saw a sculpture of máohóu at his house! That moment changed everything. I instantly felt drawn to the hairy monkey, it just entered my heart. I stopped thinking about oil painting and decided to follow this path instead. I had a strong feeling that I could dedicate my life to it. That’s how it all began!

From then on I dedicated myself to studying the hairy monkey, primarily because of its unique appearance. How to describe it? It’s simply adorable! And the key is that its form is entirely made of natural materials. This aspect left a profound impression on me. I continued my research and eventually, in 1987, tried making one myself. That was my first real attempt.

Then, about a year later, I saw a máohóu made by Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n 曹仪简 at a temple fair. He wasn’t my master yet, but his work really moved me. His monkeys came to life. They told stories. It felt like they could express what was in your heart, as if the monkey was using its fur to convey emotions.

Simon: Can you describe how you met Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n and how you became his disciple?

Qiu: Well, it was like this. I started to have more contact with Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n. I was always talking to him, asking questions and seeking his guidance. I hoped he would be willing to teach me about the art of making máohóu. He was a truly kind and generous person, open-minded and always willing to listen. What else can I say? I admired him deeply.

Over time, we developed a very strong relationship. I felt a deep sense of awe and respect towards him. In Chinese tradition, when someone wants to fully commit to a craft or discipline, it is customary to formally apprentice under a master. I continued studying under his guidance informally for years, following his example and learning through observation and dialogue. But when I expressed the desire to become his disciple, he just laughed and brushed the idea aside.

Eventually, I learned the reason why he kept putting it off. He told me that many young people today no longer have faith in folk traditions. He believed they lacked the patience and determination needed for something so time-consuming and detail-oriented. He worried they wouldn’t be able to commit the time required for the many tedious parts of the process: from shaping and assembling the monkey figures to the long, repetitive finishing steps. He didn’t want to waste his energy on someone who might give up.

以下访谈节选自邱贻生与西蒙·瓦尔德-拉索夫斯基的一次 对话录音,现场由蔡昕媛提供口译。对话发生在 2019 年 6 月 17 日的北京,本文在整理时对内容进行了适度编辑,以 便阅读。

西蒙: 之前的对话中你提到自己从小就开始动手做东 西。在接触毛猴之前,你都做过什么呢?

邱贻生: 我很小的时候,大概四五岁,就开始做手工了。 我喜欢自己动手做一些小孩的玩具。随着年纪渐长,动手 对我来说越来越自然。我会用绳子做弹弓,后来还会用木 头刻仿真枪械。那大概是初中五年级的时候吧。我特别喜 欢尝试新东西,这让我很有成就感,做出来的东西也挺像

模像样。朋友们常会让我帮他们做,有时还会给我一些小 奖励。

再后来,中学时我对绘画产生了兴趣。我对不同的美术流 派很好奇,也想去尝试。我会临摹作品,也会照着自己的想 法修改,或者跟着书里学到的方法去画。但因为我是自学, 没有老师的指导,作品里自然有不少缺陷。真正的绘画需要 系统性的理解。大约在 1982 或 1983 年,我下定决心更认 真地投入绘画实践。希望能够突破,实现有意义的成绩。

到了 1986 年,我开始对油画特别感兴趣。那时我去看望 哥哥,正好他有个朋友打算拜师学画。我也想一起。他那 位朋友本身就是很有水平的油画家。但意料之外地,也可 以说是个惊喜:我在他家看到了一件毛猴雕塑!那一刻, 一切都改变了。我瞬间被毛猴吸引,它一下子走进了我的 心里。我立刻放下了对油画的执念,决定改走这条路。我 有一种强烈的感觉:我能为它奉献一生。就是这么开始 的!

从那以后,我决定专心学习毛猴,主要是因为它独特的外 观。怎么形容呢?它就是单纯得让人着迷!关键在于,它 完全是用天然材料做成的。这一点给我留下了深刻的印 象。我继续钻研,并在 1987 年第一次尝试自己动手做毛 猴。那是我真正意义上的第一件作品。

大约一年后,我在庙会上看到了曹仪简大师做的毛猴。那 时我还不是他的徒弟,但他的作品深深打动了我。他的猴 子仿佛活了起来,会讲故事,好像能表达出你内心的情 感,借着那一身毛发在传递情绪。

西蒙: 你能讲讲你是如何遇见曹仪简老师,又是如何 成为他的弟子的吗?

I told him again and again how serious I was. I must have asked to apprentice under him dozens of times. Still, he continued to politely decline. There were many moments when I felt deeply disappointed, but I never gave up hope. My desire only grew stronger with time. Then, at the end of 2007, I made what I considered my final attempt. I remembered that I had something important, something personal: a clipping book I had compiled myself.

Since 1986, I had been saving everything I could find that mentioned Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n: articles from newspapers, journals, magazines and books. I cut them out and pasted them into a book, organising them carefully. I asked a woman from the Chinese Folk Arts Association, who was close to him, to pass the book along and convey my request once more. I sincerely appreciated this older sister for passing on my clippings.

This book made a deep impression on the master. He was moved, so much so that his eyes filled with tears. My determination and perseverance had persuaded him, and that was the moment he finally accepted me. On the second day of the second lunar month in 2008, traditionally the day when the dragon raises its head, I officially became a disciple of Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n.

There were many witnesses present during the ceremony, including representatives from the Beijing Folk Art Association, the Beijing Toy Association, the National Art Museum of China and the China Association of Arts and Crafts. They all came to congratulate me. It was unforgettable.

From then on, I became determined to preserve traditional culture and Chinese folk arts. My long-held wish had finally been fulfilled.

Simon: How was the process of learning the art of the máohóu? How often did you meet with Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n? Did you observe him at work, or did he teach you practical skills, for example?

Qiu: Learning the craft from a master isn’t something that happens overnight. My process

involved over thirty years of continuous practice, with twenty of those years dedicated to apprenticeship. The journey was definitely arduous and demanding, but at the same time, it was filled with deep joy and meaning. In the world of máohóu making, this so-called “journey” is about being immersed in the spirit of the master — his attitude, his complete dedication to the craft and his commitment to making the monkey “speak”. I was deeply influenced by that spirit.

Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n’s teaching style was unique. He used to say to us younger folks, “You already have your own ideas and skills, so I won’t teach you technique.” What he meant was, he acknowledged that we had our own paths, just as he had his. He gave us the confidence to trust in our own ideas. And while he didn’t break down the steps or methods directly, he inspired us in other, subtler ways. He didn’t pass things down formally, but he shared stories and insights that lit the path ahead.

Simon: Do you remember any specific stories he shared?

Qiu: Sometimes, while casually chatting, he would tell a joke. But in the middle of the joke, he’d pause, and within that pause, there was a story, a lesson. That’s how he guided us. He’d give you a hint or a nudge on a technique but it was never too obvious. In creativity, everyone needs their own path, but an experienced master can save you years of trial and error. What he had figured out over ten years, he might share in a single sentence, and that could save you ten years of searching.

He was calm, open and incredibly generous with his knowledge. Even outside of craftsmanship,

邱贻生: 一开始只是和曹仪简老师联系上了。我总是和 他聊,问问题,寻求指导。希望他能教我毛猴的技艺。他 是一个真正善良、宽厚的人,心胸开阔,总是愿意倾听。我 对他怀有非常深的敬意。

随着时间推移,我们越来越熟悉。我对他满怀敬畏与尊 重。在中国的传统里,如果一个人想要真正投身于一门手 艺,就要正式拜师。我在他身边学习了很多年,通过观察 和交流来模仿他的做法。但每次我提到想正式拜他为师, 他总是笑笑,就把这事搪塞过去。

后来我才知道,他之所以一直推辞,是因为他担心现在的 年轻人对民间传统没有信心。他觉得他们缺乏耐心与恒 心,而毛猴这门手艺既耗时又琐碎,从捏制小猴到组装场 景,再到繁复的收尾工序,都需要长久投入。他不愿意把 精力浪费在那些可能半途而废的人身上。

我一次又一次地告诉他我是真的想学,正式提出拜师的 请求,恐怕不下几十次。但他依旧婉拒。那时候我常常感 到很失落,但从未放弃,反而越发坚定。直到 2007 年底, 我下定决心做最后一次尝试。我想起自己有一样重要的东 西,一件很私人的东西:一本亲手整理的剪贴簿。

从 1986 年起,只要有关于曹老师的报道,不论是报纸、 期刊、杂志还是书籍,我都剪下来,整整齐齐地贴在一本 册子里,精心归类。我请中国民间文艺协会的一位前辈帮 忙,把这本剪贴簿转交给曹老师,并再次替我转达拜师的 心意。我非常感激这位姐姐的帮忙。

这本书给曹老师留下了极深的印象。他很受触动,甚至湿 了眼眶。是我的坚持与诚意打动了他。就在那一刻,他终 于答应收我为徒。2008 年农历二月初二——“龙抬头”的 日子,我正式拜在曹仪简大师门下。

在拜师仪式上,来了很多见证人,北京民间文艺协会、北 京玩具协会、中国美术馆以及中国工艺美术学会的代表 都到场祝贺。那一刻,我终生难忘。

从那以后,我立志要守护传统文化与中国民间艺术。自己 多年未竟的心愿,终于实现了。

西蒙: 学习毛猴这门手艺的过程是怎样的?你和曹 仪简大师多久见一次面?你是通过观察他工作来学 习,还是他直接传授给你具体技法?

邱贻生: 向一位师傅学习,并不是一朝一夕的事情。我 的创作生涯持续了三十多年,其中二十年都在跟随师傅 学习。这条路确实艰辛,也非常耗费心力,但同时也充满 了喜悦与意义。在毛猴这门艺术里,“学习”更多意味着 沉浸在师傅的精神之中——他的态度,他对技艺的全身心 投入,以及他让毛猴“开口说话”的执念。这种精神深深 影响了我。

曹仪简大师的教学方式很特别。他常常对我们年轻人 说:“技法我就不教你们了,你们已经有自己的想法和功 夫。” 他的意思是,他认可我们各自有自己的道路,就像 他有他自己的道路一样。他让我们学会相信自己的想法。

虽然他不会把步骤和方法直接拆解讲给你,但他会用更 微妙的方式启发你。他不会正式的传授,而是通过讲故 事、分享见解,照亮前路的方向。

西蒙: 你还记得他讲过哪些具体的故事吗? 邱贻生:

有时候,他在闲聊时会给你讲个笑话。但在笑话 的停顿里,往往藏着一个故事,一段教诲。这就是他引导 我们的方式。他可能会给你一点暗示,或轻轻点拨一招, 但绝不会说得太明白。在创作上,每个人都需要走自己的 路,但一位有经验的师傅能帮你省去许多年的摸索。他可 能十年才悟出的东西,能在一句话里告诉你,而那句话足 以让你少走十年的弯路。

he offered guidance: recommending what books to read, how to frame a problem at a specific stage, or how to see something ordinary from a completely different angle.

So in terms of creative inspiration, I truly gained a lot from him. I even joke that I got a kind of “discount”, that’s not quite the right word, but it captures the idea. I received so much insight and wisdom.

Simon: How do you come up with your ideas for máohóu scenes?

Qiu: Some of my ideas come from casual conversations with friends. There’s a Chinese saying: “Spoken without intent, but heard with intention.”

Take a piece like Monkey Looking in the Mirror. It began during a casual meal with someone mentioning Zhu Ba jiè looking in a mirror. (Zhu Ba jiè is a character from Journey to the West , a monstrous half-human, half-pig figure known for his laziness, gluttony and lust).

That image led me to a thought: monkeys also look in mirrors, but they’re not human. So, what happens when a monkey, dressed like a person in a top hat, bow tie and briefcase, stares at its reflection? It becomes satire. It mocks the surface of respectability hiding inner hollowness. No matter how they look at themselves, the reflection shows only darkness.

This work is about those who look human in form but not in spirit. Once the heart becomes corrupted, only the shell remains. This irony, the appearance of humanity without its substance, is what I wanted to explore. When someone has lost their true nature but still believes they are whole. Look in the mirror, do you see a person, or just a form?

That’s the idea behind the hairy monkey: finding a spark of inspiration and using it to create a humorous story with irony and depth. The máohóu shines when it reflects back uncomfortable truths. Like, are we just going through the motions of being “human” without really living up to it?

Master Cáo Yíjia ̌ n always said: “Calm your mind and think deeply. Don’t rely on trendy slogans or follow the crowd. That kind of work lacks depth.” Much of my inspiration comes from old Chinese sayings, passed down for generations. They carry weight, wisdom and sometimes a kind of bitter humor. This piece began with one such phrase and the quiet stories it reveals when you truly reflect on it.

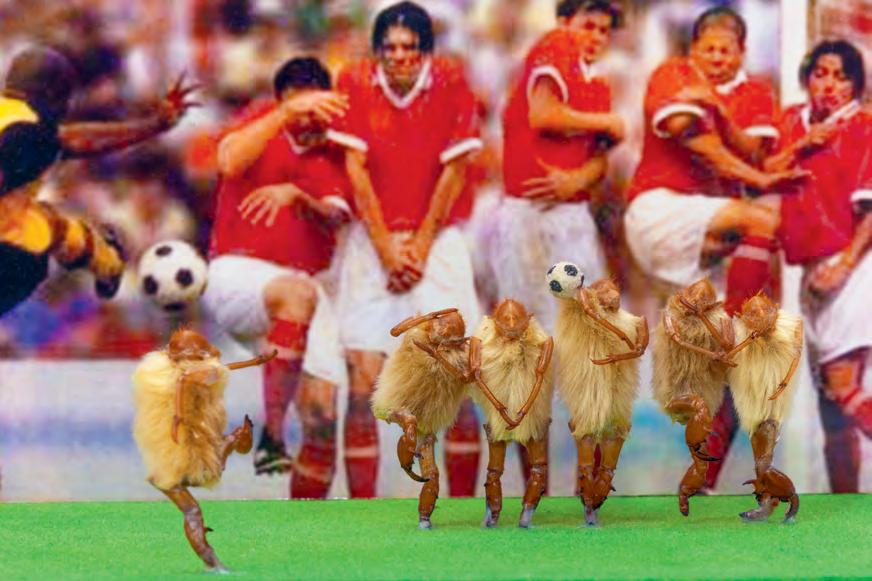

But some of my pieces also start in a light manner. For instance, one time I saw a humorous photo of football players in awkward positions, scared to be hit by a penalty ball. I just imitated the movements of the players with the monkeys and that created an instant sense of joy. There was no specific theme, really. Just fun. And then there was the time I saw the Last Supper hanging in a friend’s home. I looked it up online and found all kinds of versions, some serious, some humorous, some very clever, and I thought, why not make a version using monkeys?

Over the years, living mostly alone, your thoughts start to move differently. Sometimes I just sit and smoke and let my mind wander. I observe something for hours, then start noticing things others might have overlooked. That’s also where inspiration comes from. That’s how these things evolve. They begin somewhere small, then shift and grow. The sources of inspiration can be broad, diverse and unexpected. What matters is what you do with them.

Simon: You were also telling me about one of your earlier, let’s say, conceptual pieces, based on neither an historic reconstitution nor an existing story, where one hairy monkey is

他为人沉稳、开阔,又极其慷慨地分享知识。不仅在工艺 上,甚至在其他方面他也会给我指点:比如推荐读哪些 书,如何在某个阶段思考问题,或者怎样从完全不同的角 度去看待一个普通的事物。

在创作灵感上,我真是从他身上获益良多。我甚至常开玩 笑说,自己好像拿到了某种“优待”,虽然这个词未必恰 当,但大致就是这个意思——我从他那里得到的智慧与启 发,实在是太多了。

西蒙: 你的毛猴创意通常是怎么产生的?

邱贻生: 有些灵感来自日常和朋友的闲聊。中国有句俗 话:“说者无意,听者有心。”

比如那件《猴子照镜子》,就是一次随意的饭局上,有人

提到“猪八戒照镜子”。(猪八戒是《西游记》里的角色, 一个半人半猪的怪物,以懒惰、贪吃、好色著称。)

这个形象让我联想到:猴子也会照镜子,但它们不是人。

那么,当一只穿着礼帽、打着领结、提着公文包的猴子,对 着镜子看时,会发生什么?这就成了讽刺。它讽刺那些外 表光鲜、内心空洞的人。不论它们如何看自己,镜中的倒 影都只有黑暗。

这件作品要表达的,是那些“形似人而神不像”的人。一

旦内心腐化,就只剩下一个外壳。这种讽刺——有人的样 子,却失去了人的实质——正是我想探讨的。当一个人已经 丢掉了本性,却还以为自己完整无缺。那么照照镜子,你 看到的究竟是一个人,还是一具空壳?

这就是毛猴的意义:找到一丝灵感,用它去编织一个幽默 却带 有讽刺和深度的故事。毛猴最动人之处,就在于它能 照见那些让人不安的真相。比如,我们是否只是在机械地 扮演着‘人’,却并未真正活出作为人的意义?

曹仪简大师常对我说:“要静下心来,深入思考。不要 靠时髦的口号,不要随波逐流。那样的东西是没有深度 的。” 我的许多灵感都来自代代相传的古老俗语,它们有 分量,有智慧,有时还带着几分辛辣的幽默。这件作品就 是从这样的一句话开始的,当你真正去反思时,就会生出 许多安静却深刻的故事。

当然,也有些作品的起点很轻松。比如有一次,我看到一 张搞笑的足球照片,球员们在点球前摆出各种滑稽的姿 势,害怕被砸到。我就让毛猴模仿这些姿势,立刻产生了 一种欢乐的感觉,并没有什么主题,只是单纯的好玩。还 有一次,我在朋友家看到《最后的晚餐》,于是上网查,发 现各种版本:有的严肃,有的幽默,有的非常巧妙。我想, 那为什么不用猴子来做一个版本呢?

这些年来,我大多独自生活,思维方式也慢慢发生了变 化。有时候,我就一个人坐着抽烟,让思绪飘散,或者长 时间凝视某个东西。渐渐地,就会注意到别人忽略的细 节。这也是灵感的来源。许多东西就是这样发展起来的: 它们起初很小,后来不断转变、扩展。灵感的来源可以很 广泛、多样甚至出乎意料,但关键是你如何去使用它们。

西蒙: 你之前还跟我提过一件比较早期的作品,可以 说是观念性的,它既不是历史重现,也不是现成故事 的改编:一只毛猴在一根燃烧的香烟上撒尿。这件作 品想表达什么?

peeing on a burning cigarette. What does it represent?

Qiu: The inspiration for this piece comes from real life. Many of my works are condensed from everyday experiences or problems I’ve encountered. This one, for example, is called Quick Thinking. I suddenly felt the urge to make it based on moments I’ve observed while working in factories or other environments.

Quick Thinking is about how people react in emergencies and how quick thinking can bring safety. It’s based on three types of people you often see in a crisis. First, there’s the one who just follows the rules step by step, even when things go wrong. Then there’s the one who yells a lot, “all talk, no action”, but doesn’t actually help. And finally, there’s the person in the middle, the one who steps up, thinks fast and solves the problem. That’s the figure I wanted to depict: someone quick-witted in a crisis. It was simple but meaningful, and fun to make!

Simon: While walking in your neighbourhood, I overheard people shouting “máohóu” when they saw you. Are you becoming the living embodiment of these figures? What is your relationship to the hairy monkey?

Qiu: Yes, it’s true, people call me the old monkey sometimes, but it doesn’t bother me. From the very beginning, I’ve been deeply immersed in the máohóu. When my parents were alive they worried when I stayed up all night working. They used to say, “Don’t stay up so late.” Some friends were sceptical, asking what I was doing with these monkeys. But others encouraged me. They saw that I had found something I truly cared about. That made all the difference.

The máohóu, the hairy monkey, has become a root in my life. I can’t live without it. For thirty years I’ve thought about it every day. In the creative process, your mind is constantly asking questions. At any given moment, you’re wondering whether a particular experience could become a piece of work. Even when I go out to relax, it’s always in the back of my mind. I’ve even dreamed about solving technical challenges in my sleep, it’s that deep.

The máohóu has brought me immense joy, not only through making it, but also through the people I’ve met. I’ve made many friends through this little monkey. The creative process isn’t always easy. You hit a wall sometimes with technical problems, artistic blocks or emotional setbacks. But then you talk to someone, or try a different approach, and you move past it.

Simon: One of your friends told me during a dinner at the restaurant that the hairy monkey is different from other traditional Beijing crafts. What is your opinion on this?

Qiu: Definitely. What makes máohóu different is its use of natural materials. It’s not like other Beijing crafts that are more artificial, constructed or man-made. Máohóu has a unique relationship to the materials. It’s about combining nature’s wonder, organic matter, with human ingenuity to create something artistic. You don’t invent from scratch, you transform.

In Chinese folk art, the focus is on making use of what’s available, whatever is at hand.1 The hairy monkey is a perfect expression of that. It embodies the spirit of folk art at its finest. It teaches resourcefulness and creativity. You draw from your surroundings and your knowledge to say something personal. You take nature’s wonders and humble materials and transform them into something lively, humorous and full of character.

Simon: And there is the satirical aspect of the máohóu, which other crafts don’t have, right!?

Qiu: And then a lot more!

Simon: Even though you create a lot of contemporary scenes, you still create many scenarios that take place in older times. Why is that?

Qiu: Because the hairy monkey was so deeply loved by the people of old Beijing, I’ve devoted much of my energy to portraying everyday life in the city, its slower, more orderly rhythm. That pace wasn’t chaotic; it had a natural structure, something everyone accepted and understood. In the deep alleys of hutongs, life had a distinct

邱贻生:这件作品的灵感来自生活本身。我的很多创作, 都是从日常经历或我遇到的问题里提炼出来的。比如这 一件,我给它起名叫《机智》。当时就是突然有了冲动去 做,因为我在工厂等地方工作时,常常观察到类似的场景。

《机智》讲的是人在紧急情况下的反应,以及“机智”如 何带来安全感。它其实影射了三类人:第一类,只会按部 就班,哪怕事情出了岔子,还是机械照做;第二类,就是光 喊不干,嚷嚷得很响,却根本帮不上忙;第三类,就是能站 出来、动脑筋、迅速解决问题的人。我想表现的就是第三 种:在危急时刻能机智应对的人物。作品很简单,但有意 思,也很有意义,做的过程也很开心。

西蒙: 在你家附近散步时,我听到有人看到你就喊 “毛猴”。你是不是已经成了这些形象的化身?你和 毛猴的关系是什么?

邱贻生: 是啊,大家有时会喊我“老猴”,但我不在乎。 从一开始,我就完全沉浸在毛猴之中了。以前父母还在世 时,总担心我熬夜做东西,说“别搞到这么晚”。有些朋友 质疑我,觉得我整天弄这些猴子有什么用。但也有人鼓励

我,他们看得出我是真心喜欢这件事。正是这种理解与支 持,起到了决定性的作用。

毛猴已经成了我生命的根。没有它,我都活不下去。三十 年来,我每天都在想它。在创作过程中,脑子里不断冒出 问题:这件事能不能做成一个作品?那段经历能不能转化 成场景?即使出门散心,它也总在心里。甚至我做梦时都 会梦到解决技艺上的难题,可见它对我影响有多深。

毛猴给我带来了极大的快乐,不光是制作的过程,还有 因为它而结识的人。我交到了许多朋友。当然,创作并不 总是顺利的。有时会遇到技术难关、创作瓶颈,或者情绪 低落。但你和别人聊一聊,或者换个角度尝试,就能慢慢 走出来。

西蒙: 我记得在一次饭局上,你的朋友说过:‘毛猴 和其他北京传统工艺不一样’。你怎么看?

邱贻生:

确实如此。毛猴的独特之处就在于它的天然材 料。它不像其他北京手工艺品,多是人工制造或合成的。 毛猴和材料之间有一种特别的关系:它把大自然的奇妙、

texture. Courtyards were packed with families, and daily routines followed an informal but consistent rhythm. You’d hear bells ringing outside your courtyard, and each bell meant something different. Without even seeing them, you’d know: that’s the fan seller, that’s the vegetable man, maybe the sugar-candy vendor. These sounds weren’t just noise, they formed a pattern that shaped the day. It was soft, slow, but well-organised.

That kind of life is fading now, but I am eager to create works that preserve its feeling. The humour, the routines, the rhythm of ordinary people, it’s not just nostalgia. It’s about keeping alive the quiet beauty of a life that moved at its own pace.

Simon: There are only a few representations of women characters in your work. Most of the hairy monkeys seem to be men. Why is that?

Qiu: People often ask why there aren’t more women in my pieces and joke with me: “You always make these talkative male monkeys.” And it’s true, there is humour in that. But during the feudal era, women rarely appeared in public life. Business, trade, even street performance, all that was handled by men. So most of the characters I depict when I create scenes from old Beijing — doctors, chefs, vendors — just happen to be male. It’s not really a conscious choice; it reflects the reality of that time. Though I am thinking of some concepts for pieces manifesting femininity that haven’t been realised yet.

But actually the máohóu itself, it’s just a monkey. It doesn’t have a fixed gender. That’s what makes it magical; it’s a playful form used to reflect human life, often with humour, sometimes with a bit of critique or even filial piety. Its body may look stiff or awkward, but it’s full of spirit. It interacts with you. The way it stands, its clothing, its pose, all of that tells a story without needing words. That’s where the real value lies: not in how perfect it looks, but in the feeling it gives. Those who love the monkey understand it instinctively. That shared, silent understanding, that’s the real magic.

Simon: How do young people respond to the máohóu today?

Qiu: To be honest, most young people aren’t that interested in máohóu. Unless they come from a family with some connection to tradition or crafts, they don’t really see the value. It is time-consuming and labour-intensive and doesn’t make much money. My daughter likes the monkey, she finds it interesting, but she doesn’t love it the way I do.

That said, there are exceptions. Two young students from Taiwan often visit me. Their families combine tradition and modern thinking, and they’re genuinely interested. They’re curious and willing to learn with patience. So you never know. The spark can still be passed on, even if it’s rare.

I think that playing with the máohóu is valuable though, especially for children. They can learn not just to follow instructions, but to express and give shape to their own thoughts. Unfortunately, many children today, especially in China, grow up in systems that encourage imitation, not exploration. My mind is not totally free either, after so much traditional education. I’ve taught foreign kids, and often they’ll immediately ask questions, experiment and take risks. Chinese kids can be more cautious, afraid of doing it “wrong”. That’s why I think máohóu can teach something about freedom in creativity. And it’s just so fun!

Simon: Do you think audiences outside of China will understand or appreciate the hairy monkey, even without knowing the cultural background that it is rooted in?

Qiu: Maybe. But I don’t worry too much about that. People are curious about different cultures. The máohóu started here in Beijing, but its spirit, using everyday materials to tell stories, is universal. In a way, it’s like masks people collect. Some were brought back from abroad just because they looked cool. Some were gifts. But each one carries the ethnic beliefs of the people who made them. That’s what I find interesting, how culture travels through form and colour, through small, handmade things.

There are no real boundaries between ethnic groups. If someone uses a monkey to express their culture that’s fine. It’s a personal way to connect with tradition. But máohóu, this particular kind of monkey, that’s from Beijing. That’s where its pride

天然的物质,与人的聪明才智结合在一起,创造出艺术。 它不是凭空发明,而是转化。

在中国民间艺术里,核心精神就是“就地取材”,利用身 边随手可得的东西。 1 毛猴正是这种精神的完美体现。它 教人们智慧和创造力:从环境、从学识里汲取资源,表达 个人的东西。你把大自然的奇妙与朴实的材料,转化成鲜 活、有趣、充满个性的作品。

西蒙: 毛猴里有一种讽刺的意味,这是其他工艺里 没有的,对吧?

邱贻生: 对,还有更多!

西蒙: 尽管你创作了很多当代题材的作品,但还是有 不少场景发生在过去的年代。为什么呢?

邱贻生: 因为毛猴曾经深受老北京人的喜爱,所以我投 入了很多精力去描绘那时的日常生活,那是一种更缓慢、 更有秩序的节奏。它并不混乱,而是有一种自然的结构, 大家都习惯并接受。

在幽深的胡同里,生活有一种独特的质感。四合院里挤满 了家人,日常作息虽不成文,却自有规律。你会听到院外 传来的叫卖声,而每种声音都代表着不同的行当。即便没 看到,你也知道:那是卖扇子的,那是卖菜的,也许还有卖

冰糖葫芦的小贩。这些声音不仅仅是噪音,它们组成了生 活的节奏。温和、缓慢,但井然有序。

这种生活正在消失,但我渴望通过作品把它的感觉保留下 来。那份幽默、那份日常、那份普通人的节奏,它不仅仅 是怀旧,而是要延续一种自有步调的生活之美。

西蒙: 在你的作品里,女性角色出现得很少。大多数 毛猴似乎都是男性,为什么?

邱贻生: 人们经常问我,为什么作品里女性不多,还打 趣我,‘你老是做这些絮絮叨叨的男猴子’。的确,这有 些讽刺。在封建社会,女性很少出现在公共生活中。无论 是经商、做买卖,还是街头表演,基本都是男人在做。所 以当我创作老北京题材的场景时——比如郎中、厨子、小

贩——自然大多都是男性角色。这并不是刻意的选择,而 是那个时代的现实。不过,我也在考虑做一些展现女性气 质的作品,只是还没实现。

其实,毛猴本身就是猴子,它没有固定的性别。这正是它 的神奇之处:它是一种游戏化的形式,用来映照人类生 活,常常带着幽默,有时带点批判,甚至还有孝道。它的 身体可能显得僵硬或笨拙,但却充满了灵气,它会和你互 动。它的站姿、衣着、动作,全都能讲述故事,而无需言 语。真正的价值并不在于它看起来有多完美,而在于它传 递的感觉。喜欢毛猴的人,会本能地懂得。这种心照不宣 的理解,才是毛猴真正的魅力。

西蒙: 今天的年轻人对毛猴的反应如何?

邱贻生: 说实话,大多数年轻人对毛猴并没有那么感兴 趣。除非他们的家庭和传统或手工艺有某种联系,否则他 们很难体会其中的价值。毛猴太耗时、太费工,而且赚不 到什么钱。我的女儿喜欢毛猴,觉得有趣,但她的热爱程 度远不如我。

当然,也有例外。有两个来自台湾的年轻学生经常来找 我。他们的家庭里传统与现代思维并存,他们是真的有兴 趣,也愿意耐心学习。所以谁也说不准,这个火种还是能 传下去的,哪怕很稀有。

我觉得玩毛猴对孩子特别有价值。他们不仅能学会照着 说明做,还能学会表达,把自己的想法变成形象。不幸的 是,今天很多孩子,尤其是在中国,成长的环境更鼓励模 仿而不是探索。我自己也一样,接受了那么多传统教育, 思想并不完全自由。

我也教过外国孩子,他们常常一上来就会提问题、做实 验、敢于冒险。而中国孩子会更谨慎,怕“做错”。这是为 什么我觉得毛猴能教给人创造力的自由。而且它真的很 好玩!

西蒙: 你认为不懂毛猴文化背景的国外观众,也能理 解或欣赏它吗?

lies. My monkeys are mine. You won’t find them in Africa or Oceania. They’re rooted here.

Simon: You surround yourself with objects. Do some of those feel like friends to you? Or do you believe that they have some kind of soul or spiritual energy?

Qiu: I’ve always been drawn to shapes and colours. The form of these tiny sculptures or the way they’re put together speaks to me more than what they portray. I don’t always know why. My interest in collecting these knick-knacks and trinkets mostly comes from their shaping and sculpting.

Simon: How do you experience this book project and working together with me?

Qiu: Honestly, I’m not especially curious about people in general. But when I meet someone serious about their craft, I want to talk to them. If someone claims to love something but lacks real commitment, I keep my distance. My friends are all grounded, people who care deeply about their work. They’re not chasing trends. They just quietly do their thing.

These days, too many people want fast results or flashy attention and sadly it’s the loud ones who get noticed. Those who work hard usually stay at the bottom. They don’t boast. They don’t look for shortcuts. I respect that. Real work takes time, and you can’t fake sincerity.

Once, someone came to me bringing gifts, seeking guidance. He was motivated by personal gain, hoping to make some money from máohóu. I told him to go home. I’m not interested in that kind of energy. I’d rather work with someone inexperienced but with a true heart than with someone looking to exploit tradition for profit.

So your attitude towards your work is something I really admire. These qualities are missing in many people today, because, honestly, modern life makes people too restless. Especially after thirty years of reform in China, money has become a symbol of status. It’s complicated. Perhaps in the future, when people are wealthier, this mindset will change. I hope more people like you will then emerge, people who are willing to work hard and leave something meaningful for society.

邱贻生: 或许吧。不过我不太担心这个。人们总是对不 同文化感到好奇。毛猴起源于北京,但它的精神——用日 常材料来讲故事——是普遍的。从某种意义上,它像人们

收集的面具。有的面具是因为外观酷,被人从海外带回来 的;有的是礼物。但每一个都承载着制作者所属族群的信 仰。这就是我觉得有趣的地方:文化通过形式与色彩、通 过这些小小的手工物件流传。

民族之间其实没有真正的界限。有人用猴子来表达自己的 文化,这没问题,那是一种和传统的个人连接。但毛猴,这 种特定的猴子,只属于北京。这就是其骄傲所在。我的猴 子是我的,你不会在非洲或大洋洲找到它们。它们根植于 这里。

西蒙: 你身边摆放着许多物件。你会把它们当作朋友 吗?或者你相信它们拥有某种灵魂或精神能量吗?

邱贻生: 我一直被形状和色彩吸引。那些小雕塑的形态, 或它们组合在一起的方式,对我来说,比它们具体表现什 么更能打动我。我自己也不总知道为什么。我收集这些小 摆件、零碎的兴趣,主要还是出于对造型和雕琢的喜爱。

西蒙: 你怎么看待这本书的项目,以及和我一起工作 的经历?

邱贻生: 老实说,我平常对人不算特别好奇。但如果遇到 一个真正对自己的手艺认真投入的人,我就很想和他交 流。如果一个人自称热爱某件事,却没有真正的投入,我就 会保持距离。我的朋友都是脚踏实地的人,他们深切得在 乎自己的工作。他们不追潮流,只是安静地做事。

现在太多人想要快结果、图热闹。可惜往往是那些声音最 大的被看见,而真正努力的人常常留在底层。他们不吹嘘, 也不走捷径。我尊敬这一点。真正的工作需要时间,你装 不出真诚。

我记得有一次,有个人带着礼物来找我,想请我指点。他的 动机是为了赚钱,从毛猴里捞点利益。我直接让他回去。我 对这种心态没兴趣。我宁愿和一个没有经验但有真心的人 合作,也不想和只想利用传统牟利的人打交道。

所以我很欣赏你对工作的态度。这种品质在今天的人身上 已经不多见了。老实说,现代生活让人太浮躁。尤其是经 过三十年的改革开放,钱成了地位的象征。这很复杂。或 许将来,人们更富裕了,心态才会改变。我希望那时会出现 更多像你这样的人,愿意踏实做事,为社会留下有意义的 东西。

西蒙: 我希望这本出版物不仅仅是一部关于毛猴的 传统书籍。我在想,可以加一些更有趣的照片,比如 制作过程,或者在毛猴旁边放一些物件做参照。你觉 得怎么样?

邱贻生: 完全没问题。不同的视角和想法,正是让世界丰 富多彩的原因。每一个想法都应该有被表达的机会。

西蒙: 你曾说过,在毛猴上花的钱比你从中赚到的 还多。这种状态其实很像很多当代艺术家的生活:他 们把全部热情投入作品里,但往往得不到多少物质回 报。这对你来说会困扰吗?

邱贻生: 在这个过程中,我学会了坚持。这就是我的人 生。我可以失去其他一切,但不能失去它。我们没必要非

Simon: I’d like this publication to go beyond a classic book about the máohóu. I’m thinking of adding playful photos on the process or objects placed beside the máohóu for scale. How does that sound to you?

Qiu: That’s totally fine with me. Different perspectives and ideas, that’s what makes the world vibrant and diverse. Every idea should be given a chance to be expressed.

Simon: You told me that you have spent more money on the hairy monkey than you have earned from it. That approach is actually quite similar to how many visual artists live. They pour their whole passion into their work, yet often receive very little material reward in return. Does that ever bother you?

Qiu: I’ve learned perseverance through this process. This is my life. I could lose everything else, but not this. We don’t have to be rich and powerful, I don’t care for luxury or status. Actually, in modern times, if you don’t live extravagantly, you can still have a good life. Sure, more money might help me realise certain ideas or take on more ambitious projects. But I’m content. What brings me the most happiness isn’t material, it’s the joy others feel when they see the work, that spark of recognition. That feeling is priceless. No luxury can replace it. The joys I’ve found through this work, and the connections it’s brought me, are irreplaceable.

Simon: How do you envision the future of your work and the preservation of the máohóu tradition?

Qiu: I often wonder whether my work will endure. Maybe I made something years ago that no longer satisfies me, but at the time, I poured my heart into it. I still revisit those pieces, notice their flaws and reflect on how to better express the monkey’s spirit. It’s not that I’m unhappy with the work itself, but I see where things could grow, how to make future pieces more refined. The key is capturing that essence of the monkey, a kind of liveliness or character that’s hard to describe in words. In my work I don’t want to break the mould of the tradition, I want to innovate within it, by giving

the monkey, for example, hair, a suit and human legs. I want to give viewers a fresh feeling.

If I sold my dioramas one by one, they’d soon vanish. But if I donate them to a museum or institution, they can be preserved as a whole, not just as decorations, but as living reflections of thought, humour and history. That’s my hope. But which museum would take them? We’ll see.

I believe the máohóu tradition should be passed on, but not just through copying. It must carry responsibility, a sense of public good. Craft techniques can be taught, and as they say “practice makes perfect”. But if you’re only repeating the same forms, even with new subjects, you’re still stuck in the same thinking. Your core remains unchanged. That doesn’t mean much. You are just replicating. So the challenge lies in the mind, the intention behind the work. Art requires imagination, and that’s not something everyone has. If you want to leave something lasting, it has to reflect your own ideas. That way, even after you’re gone, your thoughts remain.

Craft has its rules; art has no boundaries. Not everyone can elevate craft to art, but everyone can try. As the saying goes: “Live until you’re old, learn until you’re old.”