Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmeta.com/product/so-you-think-you-can-think-tools-for-having-intelligentconversations-and-getting-along-christopher-w-dicarlo/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

So You Think You Can Marry an Alien Stargazer Alien Reality Show Brides 1 1st Edition Black Tasha

https://ebookmeta.com/product/so-you-think-you-can-marry-analien-stargazer-alien-reality-show-brides-1-1st-edition-blacktasha/

Power of Ignored Skills Change the Way You Think and Decide 1st Edition Manoj Tripathi

https://ebookmeta.com/product/power-of-ignored-skills-change-theway-you-think-and-decide-1st-edition-manoj-tripathi/

Mindset Changing The Way You Think To Fulfil Your Potential Updated Edition Carol Susan Dweck

https://ebookmeta.com/product/mindset-changing-the-way-you-thinkto-fulfil-your-potential-updated-edition-carol-susan-dweck/

I Think and Write Therefore You Are Confused Tehnical Writing and The Language Interface 1st Edition Vahid Paeez

https://ebookmeta.com/product/i-think-and-write-therefore-youare-confused-tehnical-writing-and-the-language-interface-1stedition-vahid-paeez/

https://ebookmeta.com/product/you-can-you-up-2024th-edition-zoehardison/

The Slightly Greener Method: Detoxifying Your Home Is Easier, Faster, and Less Expensive than You Think Tonya Harris

https://ebookmeta.com/product/the-slightly-greener-methoddetoxifying-your-home-is-easier-faster-and-less-expensive-thanyou-think-tonya-harris/

Chemistry You Can Chomp Super Simple Science You Can Snack on Jessie Alkire

https://ebookmeta.com/product/chemistry-you-can-chomp-supersimple-science-you-can-snack-on-jessie-alkire/

A Deep Sky Astrophotography Primer Creating Stunning Images Is Easier Than You Think 1st Edition Michael O'Brien

https://ebookmeta.com/product/a-deep-sky-astrophotography-primercreating-stunning-images-is-easier-than-you-think-1st-editionmichael-obrien/

Flip the Switch Achieve Extraordinary Things with Simple Changes to How You Think 1st Edition Jez Rose

https://ebookmeta.com/product/flip-the-switch-achieveextraordinary-things-with-simple-changes-to-how-you-think-1stedition-jez-rose/

So

You Think You Can Think

So

You Think You Can Think

Tools for Having Intelligent Conversations and Getting Along

Christopher W. DiCarlo

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham • Boulder • New York • London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 by Christopher W. DiCarlo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: DiCarlo, Christopher, 1962– author.

Title: So you think you can think : tools for having intelligent conversations and getting along / Christopher W. DiCarlo.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “This book offers the reader genuine hope that civility has not been lost to blind, dogmatic beliefs in personal or political ideology and that we can regain our sense of fairness and continue to have discussions about important matters, disagree entirely, but still be able to get along and appreciate discourse over hatred, dialogue over violence, and most importantly, fairness and understanding in our

disagreements on important issues” Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019057259 (print) | LCCN 2019057260 (ebook) | ISBN 9781538138557 (cloth) | ISBN 9781538138564 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Thought and thinking. | Courtesy. | Fairness. | Conduct of life.

Classification: LCC BF442 .D53 2020 (print) | LCC BF442 (ebook) | DDC 160 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057259

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057260

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

This book is dedicated to all of my students past, present, and future.

Too often we give children answers to remember rather than problems to solve.

Levin

Roger

Cover

Half Title

Title

Copyright

Dedication

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I: The ABCs of Critical Thinking Why an Argument Is Like a House Be Aware of Biases Context Is Key

Breathe from Your Diagram

Evidence Analysis of Fallacies

Part II: Applying the ABCs of Critical Thinking to Important Issues

7 Tools for Having Intelligent Conversations and Getting Along

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography About the Author

Introduction

This is the fourth book I have written on the topic of critical thinking, and in each book, I always cover the same series of tools that make up what we might call the critical thinking skill set. I have often wondered why, over the past twenty-five years of my academic career, has critical thinking not been in the curricula of all of the primary and secondary education systems. It has been a great mistake in the education systems of our youth to believe that all our students come prepared with the abilities of knowing how to think. They don’t. At least, most of them don’t. So it becomes incumbent on all educators to take the necessary steps to ensure that all students at all levels of education receive a proper education in how to think about various subjects and important issues. This means that we must teach critical thinking skills at every level of education from preschool to graduate school.

Perhaps some of the reasons that such critical thinking skills are not taught at these levels lie in the very terms that are used within the critical thinking skill set. For example, the very name critical thinking suggests that it involves a type of negative or critical attack on a person’s ideas or beliefs. Who wants to have their ideas criticized or challenged, right? Although it is true that with critical thinking we need to be able to critique all information, this needs to be seen, understood, and accepted as a very positive thing. Unfortunately, we cannot sugarcoat the field of critical thinking by calling it something else. We could try calling it “clear thinking,” “helpful-suggestion thinking,” or “rainbows and unicorn thinking,” but the fact of the matter is that, in order to become

intellectually mature, we have to be prepared to accept criticism of our ideas no matter how much we cherish them or have emotionally invested in them.

Another word that might be considered problematic within the field of critical thinking is the use of the term argument. The very basis of critical thinking requires us to put our ideas into the form of arguments. But the word argument itself is often perceived as having negative connotations, suggesting that people are embroiled in emotionally heated disagreements, and so some might equate the word argument to the act of “arguing.” This is unfortunate, for, as we shall soon see, putting one’s ideas into the forms of arguments is the best possible way to be understood, so there is nothing negative about the use of the word argument in critical thinking.

It is even possible that another common term used in the critical thinking skill set has people confused or uncertain, and that is the use of the term fallacy. For the record, a fallacy is not a penis; it’s an error in reasoning. Although it might sound like the word phallus, I can assure you that a fallacy has very little to do with male genitalia.

Critical thinking skills teach us that there really are better and worse ways to think about things. It really is possible to have intelligent discussions, disagree entirely, and still be able to get along. Due to recent events in the world of politics and the media, the Oxford Dictionary’s Word of the Year for 2016 was post-truth an adjective defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”1 This is an extremely sad commentary on how information is delivered, interpreted, and acted on. By repeatedly stating talking points even if they involved false information politicians are saying whatever they feel is appropriate to make their point. This is done through the excessive use of “echo chambers” a media term indicating the uncritical way in which unchecked and untrue information can be repeatedly stated over and over again until it appears to be factual. In many cases, the false information sometimes referred to as “alternative facts”2 is treated as factual by some news agencies. This is hauntingly similar to what Joseph Goebbels, the Reich minister of propaganda for the Nazis, said during World War II:

If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it. The lie can be maintained only for such time as the State can shield the people from the political, economic and/or military consequences of the lie. It thus becomes vitally important for the State to use all of its powers to repress dissent, for the truth is the mortal enemy of the lie, and thus by extension, the truth is the greatest enemy of the State 3

Once “fake news” or “alternative facts” become accepted as factual, it feeds

on confirmation bias and becomes entrenched in the minds of people who want to believe it to be true. There is supporting evidence indicating that fake news leads to false memories.4 And when the false memories are accepted as true, they can become so entrenched that it is almost impossible to correct. However, in attempting to respond to and correct the falsities, those who wish to fact-check such claims often come under attack as belonging to a grand conspiracy, trying to suppress the truth. Post-truth politics makes considerable use of conspiracy theories. A recent study suggests that conspiracy theorists actively seek out online communities to continuously reconfirm their biases toward a specific conspiracy theory.5 To criticize such conspiracy theories with inconvenient things like facts might lead to accusations of being a member of the “mainstream media” or the “Establishment.” In critical thinking, this is called “insulating one’s argument against criticism.” It is an attempt to make any claim impervious to scrutiny and criticism. We will have none of that in this book and, it is hoped, in society. In order to live in free and just societies, all information is open to criticism and scrutiny without exception. So it’s time to make facts and critical thinking sexy again.

It has unfortunately become quite fashionable today to claim that what people feel about issues should be taken as seriously as the facts about those issues. As we shall see, emotional attachment to specific viewpoints and the facts about the world are often two completely different things. It’s not as though a person’s feelings are not to be validated; they are. However, one’s feelings should be validated only up to the point where they conflict with the facts.

Learning the tools of the critical thinking skill set will allow you to more effectively communicate what it is you believe and why it is you believe it so that people will have an easier time understanding you. In so doing, you will be empowered with the capacity to better understand what people are saying to you and to know the various components of why and what it is they are saying. Your thinking will become better as well because what emerges from your ability to understand and use these skills is an element of diplomacy and fairness when having intelligent discussions and dialogue about important issues. And this will translate into more civil disagreement.

The biggest takeaway from this book is that if people use the critical thinking skill set fairly, they will be more empowered to have meaningful discussions about important issues, disagree entirely, and still be able to get along. Learning these skills will allow us to value discourse over hatred, dialogue over violence, and, most important, fairness and understanding in our disagreements on important issues.

The concept of fairness is the Golden Rule of dialogue and the cornerstone

of critical thinking.

If we play fairly and if the others with whom we disagree play fairly, I will guarantee you that both sides will get the most of what they want. But and this is a very big but both sides must play fairly for this to work. If this were done more often, it would save untold amounts of time, energy, and money. But we can be greedy, self-centered, and stupid, and in so doing decide not to play fairly. There are few values we humans hold dearer than fairness. We have builtin, hardwired fairness detectors within us. As such, when it comes to decisions and judgments, we tend to dispute results less if we believe that they were at least arrived at in a fair and just manner. So if we can be fair even when disagreeing, it will increase our capacity to understand and deal with differences of opinions. In a world where disagreements are going to happen, we need to relearn how to have important discussions that may become emotionally heated but also realize that we can and should still get along. It’s easy to agree and get along, but we have forgotten how to value and use the art of disagreement in civil and political discourse. It is important for us to know that it’s okay to disagree. We need to accept that we’re not always going to agree and that even if we are diametrically opposed to another’s viewpoints, we can still be their neighbor, friend, in-law, coworker, or family member.

You believe climate change is real; she doesn’t. You believe the Democratic political philosophy is superior; he thinks the Republicans know better. You like the Yankees; she’s a Red Sox fan. You’re pro-life; she’s pro-choice. You say, “To-mah-to”; she says, “Shut the up!”6

The biggest takeaway here is that we need to relearn how to think so that we can disagree and still get along, and this requires maturity and diplomacy, but, above all else, it requires fairness. These are not easy traits to develop. In fact, developing and practicing them is one of the toughest challenges we face as inhabitants of a civilized world. Thankfully, the skills of critical thinking provide us with the capacity to be mature, diplomatic, and fair and allow us to disagree in a civil manner. For the majority of us, developing such skills will not happen overnight or in a week or a month. It is something that is ongoing and requires continuous practice, development, and use. But this takes time and a lot of practice, and in today’s Age of Immediacy, with information and opinion just a click away, there seems to be less and less time in which to practice such skills. Perhaps this is one of the reasons so many people are feeling their way through issues rather than thinking critically about them.

Why an Argument Is Like a House

n this chapter, we will consider various aspects of argumentation. First, we will consider what an argument is and why it is a good thing to develop when having any kind of discussion. More often than not, people think that arguments are bad things. This is because we often attribute and associate negative value and bitterness when we hear people “arguing.” So when we read or hear the word argument, it is not surprising that in the minds of many people, it can contain negative connotations. However, quite the contrary is the case. Arguments allow us to construct our ideas in a way that makes it easier for people to understand us. We will also look at different types of reasoning that are used in the development of arguments. For example, we will look at deductive, inductive, and abductive forms of reasoning that help us construct arguments.

WHY AN ARGUMENT IS LIKE A HOUSE

An argument is a good thing. As mentioned above, when we hear the word argument, we often attribute negative associations to it because it calls to mind angry, bitter, and sometimes violent altercations both verbally and physically between two or more people. So, just as the term critical thinking is off-putting to many people because they expect its users to “criticize” their views to the

point of ridicule or embarrassment, so too are negative connotations associated with the term argument. It follows, then, that the first hurdle we must overcome in learning how to think critically involves destigmatizing the very language we must use in order to express ourselves more clearly and effectively. So let me assure you that critical thinking is a wonderful skill for anyone and everyone to have and to use. For it is not focused simply on destructively criticizing the arguments or beliefs of others. It is used equally as much in the constructive development of ideas in order to gain greater clarity and understanding. This is a good thing for both sides of an argument.

So what is an argument? An argument is formed when a person makes a claim that is further supported by another statement. For example, when I state, “I believe Justin Bieber is the greatest pop star of all time,” I am making a claim. However, this claim by itself is not an argument. It requires further support from at least one other statement. For example, I might believe Justin Bieber is the greatest pop star of all time because of his magnificent singing voice. If that were the case, then I would have an argument. My main point, or conclusion, is that Justin Bieber is the greatest pop star of all time. My supporting reason for believing this, or my premise, is that he has a magnificent singing voice. So my argument looks like this:

Justin Bieber is the greatest pop star of all time because of his magnificent singing voice

Now, whether or not this is a good argument or whether or not you agree with this argument is not the point. The point is that I now have an argument, whereas before I simply had a statement. And my argument, just like all arguments, is always made up of two parts: my main point, or what is formally called the conclusion, and my reasons for believing my main point, or what are formally called premises. If you want to be better understood, then you need to put your ideas into the form of arguments. Likewise, if you want to better understand what someone means, try to understand their ideas in the form of arguments.

An argument is essentially the way in which we put together or structure our ideas, beliefs, or opinions so that we are more clearly understood. So the structure of every argument takes the following form:

Premise(s) + Conclusion = Argument

You now know what an overwhelmingly large part of the world’s population does not: the structure of an argument. If any journalist were to walk down any Main Street of any major city in the world with a camera and a microphone and asked people what an argument is, very few would know what you now know.

What you now know is that when you put your beliefs, your ideas, and your thoughts into the form of an argument, it greatly increases the likelihood that people will understand what you believe and why you believe it. This, in turn, opens the door for a greater likelihood of being understood. This will then lead to a greater likelihood of more interesting, productive, and relevant discussions about any issue, from the most mundane to the most sublime. It is often the case that people get into heated disputes because they are simply talking past each other and discussing issues emotionally rather than logically. That is to be understood. Very few schools in the world, from kindergarten to grade 12, teach students how to think. The skill of thinking is simply assumed in most education systems throughout the world. So it is not surprising to find that when we look to our politicians, our statesmen, and our world leaders to demonstrate effectiveness of thinking and clarity of thought, we are often surprised. But it should come as no surprise for those who have seen the erosion of education systems for many decades. So it is time to make critical thinking sexy again. Once we see the value in effective communication and productive dialogue, the skill set of critical thinking will sell itself. But we have a long way to go, so let’s get back to it.

At this point, we don’t have to worry too much about whether we agree with the content of the argument; we’ll get to that later. Right now, the most important point is to stay focused on the structure of an argument.

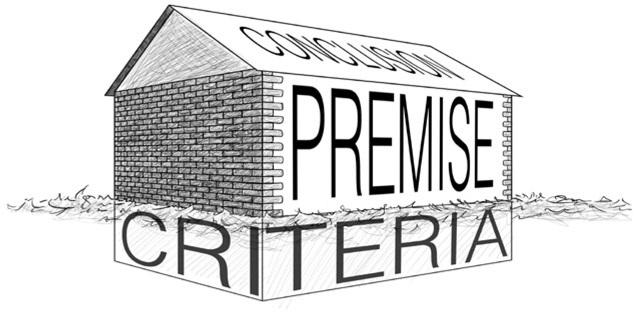

So how is an argument like a house? First, recall that the main point you want to express is called the conclusion of an argument. That’s like the roof of a house. And if you can remember that the supporting statements for your conclusion are called premises, they are like the walls that support the roof of the house. But the premises supporting a conclusion, like the walls of a house, will support the roof only if they are firmly anchored onto a strong foundation. In critical thinking, the foundation is made up of universal criteria.

So, how well the premises satisfy or fail to satisfy the universal criteria determines the extent to which the structure of an argument is sound or solidly supported. So we literally build arguments in ways similar to the construction of houses. Just as you would never build a structure on an impermanent or questionable foundation like sand so too would you avoid developing an argument that could not stand or satisfy universal criteria of acceptability.

Figure 1.1. Argument as House

Your roof (conclusion) may be a relatively innocuous claim: “It is a lovely day today.” Or it could be more controversial: “Elvis was abducted by aliens.” But there is a general rule in critical thinking: the greater the conclusion (roof), the stronger the premises (walls) need to be. All houses (as arguments) must rest on the same foundations (universal criteria). However, not all arguments abide by these criteria as well as others. So their premises (walls) become weakened and prone to imbalance. If premises can be demonstrated to be weak in some respects, the house (argument) becomes increasingly prone to collapse.

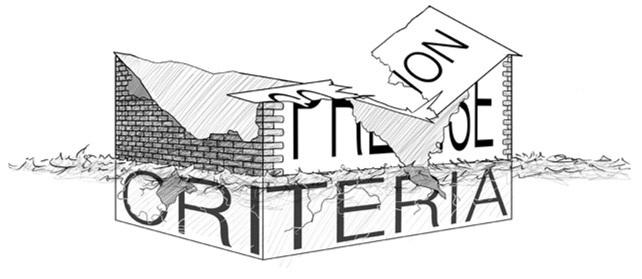

Not all of our arguments will be able to withstand scrutiny. This is simply a fact of life. For those of you who thought you had good reasons or premises to believe that the Tooth Fairy existed and then found out she didn’t, do you still believe in her? Of course not. Your conclusion could not withstand the scrutiny of critical thinking. But that’s okay.

Many of our beliefs come under similar scrutiny and must suffer the same fate. If we are wise, we emerge from the rubble of these fallen houses with the renewed ambition to start building new houses with stronger walls.

Just as old dwellings and buildings eventually age, decay, and become uninhabitable, so too do some of our most cherished beliefs. We may think one way in our youth, but eventually, as we age over time, we may come to see the world in vastly different ways. As we progress through our landscape of beliefs, we inevitably tear down old and weathered ideas to clear the ground for the construction of new and more soundly built arguments.

1.2. Weak Argument

THE FOUNDATION OF AN ARGUMENT CONSISTS OF UNIVERSAL CRITERIA

In order for an argument to be solid and sound, not only must the walls be sturdy, but the foundation must provide the greatest support. There are several universal criteria that make up the foundation. These are consistency, simplicity, relevance, reliability, and sufficiency. In critical thinking, criteria are really just standards of judgment that we use for evaluating or testing our claims and those of others. Fortunately, there is universal agreement about the criteria used to support our premises that effectively and efficiently allows us to speak to one another on a very level playing field. Let’s look at the first and most important of our universal foundational criteria: consistency.

THE MOTHER OF ALL UNIVERSAL FOUNDATIONAL CRITERIA: CONSISTENCY

There is little doubt that the most important of all universal criteria in critical thinking is consistency. So we are going to have to spend a bit of time learning about it. If an argument is not consistent, it is weak and extremely prone to

Figure

collapse. Consistency is so important that it is sometimes referred to as the “mother of all criteria” and the guiding principle of all rational behavior. Aside from a few world leaders, can you think of a time when anyone was ever praised either in speech or in action (think “alternate facts”) for their inconsistencies? We tend to dislike inconsistencies because we understand the world best when we can predict (with some accuracy) the anticipated outcomes of actions. When our expectations are violated, we experience a sense of dissonance and identify (on a very pragmatic level) the negative aspects and consequences of such inconsistencies. There is overwhelming evidence to support the conclusion that all species highly value consistency in communication and behavior.1 This is what I believe to be one of the main reasons why humans and other species universally place so much value on the criterion of consistency. Recognizing and utilizing that future events will be similar to past events involves inductive and comparative reasoning, and it has been hardwired into our DNA for hundreds of thousands of years. Because if our beliefs and actions are inconsistent with the way the world actually works, it often has very drastic and harmful effects. And nature can be very cruel in reminding us of the importance of consistency.

I can remember a time when I was teaching at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, and there was a story in the student newspaper about a group visiting the campus who claimed to be able to live off of nothing but oxygen and light they are called Breatharians. When they came to campus, I went to their display booth in the central student building and questioned them regarding the consistency of their claims. I soon realized that the quickest way to demonstrate the falsity of their claims involved a consistency challenge: I agreed to voluntarily give up my office for several of them to reside in for two weeks without food or water of any kind; however, they could breathe all of the air and leave my lights on all they wanted or even bring in their own special lights. Since it is very difficult for the human body to survive without liquid even for a relatively short period of time it should become apparent fairly early on in this challenge that nature would clearly demonstrate the inconsistency of their beliefs. The purpose of such a challenge is not to be vicious, malicious, or otherwise cruel. The forcefulness of the challenge is used to demonstrate the importance of consistency in how we perceive and understand the world. Since it is inconsistent to claim that a person could live on nothing but light and water for two weeks, one needs to consider how the inconsistency of such a claim could be demonstrated. In other words, how else might we falsify such a claim than through empirical demonstration? As it turns out, such a challenge eventually was taken up by the leader of the Breatharians Jasmuheen, formerly

Ellen Greve on Australia’s 60 Minutes:

Jasmuheen volunteered to appear on Australia’s “60 Minutes” to prove her claims of living on light After 48 hours, her blood pressure increased and she exhibited signs of dehydration She attributed these symptoms to polluted air. The program moved her to a location further from the city, but as her speech slowed, pupils dilated and weight loss continued, the doctor supervising the observation advised the program to quit the experiment before she lost more kidney function, and they did so. Jasmuheen maintains that “60 Minutes” stopped the test because “they feared [she] would be successful.”2

Notice how even in the face of such obvious falsifying measures, Jasmuheen still maintains that it is not her beliefs that are factually wrong but rather the fear of the press (and the rest of the world) that she is correct. Such a challenge clearly demonstrates the power of critical thinking and the importance of consistency. Now if we really want to look at the facts regarding Jasmuheen’s claim rather than her ideological feelings, here they are:

What happens to the human body without food and water? Without food, the body must find another way to maintain glucose levels At first, it breaks down glycogen Then, it turns to proteins and fats. The liver turns fatty acids into by-products called ketone bodies until there are too many of them to process. Then, the body goes into a life-threatening chemical imbalance called ketosis. It’s actually dehydration, though, that has a more immediate fatal effect A person can only survive without water for a matter of days, perhaps two weeks at most. The exact amount of time depends on the outside temperature and a person’s characteristics. First, the body loses water through urine and sweat A person then develops ketosis and uremia, a buildup of toxins in the blood Eventually, the organ systems begin to fail. The body develops kidney failure, and an electrolyte imbalance causes cardiac arrhythmia Dehydration leads to seizures, permanent brain damage or even death Jasmuheen has said, “If a person is unprepared and not listening to their inner voice there can be many problems with the 21 day [fasting] process, from extreme weight loss to even loss of their life ” Science says that the human body cannot survive without food and water for that amount of time, regardless of what the inner voice says 3

Notice again how Jasmuheen tried to insulate her beliefs by blaming failure on the individuals themselves rather than on her health advice. So if an individual is unprepared by not listening to their inner voice, this is what causes health problems and even death, not facts like starvation and, far more likely, dehydration. We must remain vigilant in keeping the onus of proof squarely where it rests: with those who make such extraordinary claims. Jasmuheen’s attempts to heap excuse after excuse on her failed belief system commits what is known as the ad hoc fallacy (a fallacy we will look at more closely in chapter 6). Basically, the fallacy is committed when people refuse to admit when their belief, opinion, or idea has been demonstrated to be false through empirical or scientific means. Instead of admitting to the obvious inconsistencies of their position, they continue to come up with more rationalizations in defense of it.

If you have ever been bothered watching a political figure discuss important issues only to be shown how, at another time, video footage demonstrates that he or she said exactly the opposite and wondered why this bothered you so much, you’re not alone. What you’re feeling is a violation of consistency. We humans, along with a lot of other species, are hardwired to detect inconsistencies. Otherwise, our ancestors never would have survived to the point of allowing you to read this book. Without consistency in our lives and minds, we would live in a horrifically mad world that did not make sense. So when the world feels a little out of sorts to you, you can blame your consistency meter that dwells deep inside of you. This is why it is the most important universal foundational criterion on which we measure the value of our beliefs. For if our ideas are inconsistent from the very beginning, they can have no conviction or sway over anyone. Consistency may not guarantee agreement, but it will definitely produce greater clarity of thought.

In today’s alternate political universe, with alternative facts, post-truth politics, and glib off-the-cuff comments from all quarters, there is a greater need for clarity of thought, empowerment in presentation of ideas, and directness in communication. People need to know when they’re being not only lied to, presented with alternative facts, double-spoken to in a hauntingly similar manner to that found in Orwell’s 1984 but also to be able to call some information what it is: bullshit! And they need to be able to understand the nuances and the qualities of such statements in order to hold others accountable for their beliefs and their actions. I find Harry Frankfurt’s distinction between “lying” and “bullshit” to be useful in outlining why, specifically, for example, President Trump is so good at pitching it:

The liar asserts something which he himself believes to be false. He deliberately misrepresents what he takes to be the truth. The bullshitter, on the other hand, is not constrained by any consideration of what may or may not be true In making his assertion, he is indifferent to whether what he is says is true or false. His goal is not to report facts. It is, rather, to shape the beliefs and attitudes of his listeners in a certain way.4

It could be said that Trump comes from a long, highly esteemed line of “bullshitters,” and he’s not alone in this regard. Let’s remember that there are just as many Democratic bullshitters these days as Republicans, and that’s because politics, in general, has evolved into a game of ideologies and personal agendas. Bullshitting, of course, dates all the way back to ancient Greece.5 During these times, there were a group of philosophers known as the Sophists. The Sophists would travel from town to town, and for entertainment, they would engage in formal debates on practically any topic or subject. It was often

considered the Sophists’ calling card that they would brag about how they could argue the worst case and make it appear more convincing. They were well versed in rhetoric, or the ability to convince somebody of their argument. Rhetoric, or what could also be called the art of persuasion, is important. However, right now, I want to stay focused on the importance of universal foundational criteria and why these act as the basis for what determines an argument to be either good or bad.

Now the Sophists, from which we get terms like sophistry, 6 were extremely adept at tapping into whatever was necessary in order to win the most votes in a debate. If this meant appealing to the crowd’s emotions, so be it. If this meant using pretzel logic or reasoning so twisted that people could not tell whether it was true, so be it. Fortunately for us, perhaps the greatest philosopher of all time, Aristotle, wasn’t impressed with this type of bad reasoning. So he developed some basic rules of thinking that would challenge and falsify the claims of the Sophists.

Aristotle decided there had to be a foundational logic that could cut through this kind of bamboozery and hucksterism that defied consistency and fooled audiences. So he developed some basic principles of classical logic known as the three laws of thought. As you will see in the next three sections, each law provides the basis for the power and effectiveness of the criterion of consistency.

The Law of Identity

This is the first and most basic law. It states that x = x, where x refers in both cases to the same thing at the same time and in the same respect. The truth of this law becomes obvious whenever someone tries to make statements such as “A toothbrush is not a toothbrush” or “A great white shark is a Lazy Boy recliner.” Violating such a law immediately reveals an inconsistency. So if you happen to be swimming in the ocean and you come across a great white shark, don’t try to sit or lie down on it.7

Here are some proper examples of the law of identity:

212ºF = 100ºC

Iceland has witnessed peace for over 50 years = Iceland has not been at war for over half a century

If you don’t eat your meat you can’t have any pudding! = How can you have any pudding if you don’t eat your meat?1

This =

1. Pink Floyd, “Another Brick in the Wall,” from the album The Wall.

2. Robert De Niro, The Deer Hunter.

This law provides a basis for us to understand what things are by what defines them as well as how they are distinguished from everything else. In other words, my computer is not my dog, my dog is not my office door, my office door is not my car, and my car is not my son. Each of these things has unique identities, and we come to know these things through their many properties. To show the absurdity of the results of contradicting this law, imagine a world in which people, statements, and objects randomly changed properties and functions; for example, if you tried to open your car door and it turned into a hippopotamus, if on some days water satisfied thirst but on other days it did not, or if the laws of physics worked only randomly and unpredictably, neither you nor anyone else nor any other species on this planet would be able to predict and exercise any type of control over their environments. In such a bizarre world where everything and its opposite can happen, we can only imagine the absolute horror that would ensue in trying to survive and adapt to such surreal circumstances.

The Law of Noncontradiction

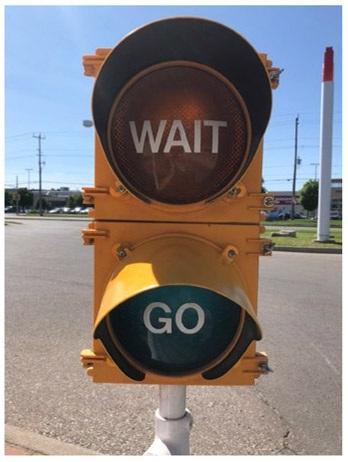

The second law that Aristotle developed to demonstrate the importance of consistency maintains that either a state of being or a statement and its negation cannot both be true. In other words, it is impossible both logically and physically for an object to be entirely liquid and entirely solid at the same time and in the same respect. It is impossible for me to say that I am now both lying and not lying at the same time and in the same respect. In the same manner, we can also say that a statement cannot both be true and false simultaneously. For example, the statement “The Buffalo Bills both won Super Bowl XXV and lost it” is a contradictory statement and cannot be true. The law is basically saying, “You can’t have your cake and eat it too.” You can have your cake, or you can eat it, but you can’t have it both ways. That’s all there is to it. I remember coming through a car wash near my home. At the point of exit, there is a traffic light that has an amber light that says, “Wait” and a green light that says, “Go.” The last few times I came through the car wash, both lights were flashing simultaneously.

Such situations can be confusing (and potentially dangerous) because we are given contradictory commands. Arguments cannot be consistent if parts of them are contradictory.

The Law of Excluded Middle

With this particular law, Aristotle said that any meaningful claim that one thinks or any natural state of being must be either true or false. In other words, there is literally no middle ground. For example, it must be either true or false that you can run a mile in less than two minutes. There is no middle ground allowed in this distinction; either you can do it, or you can’t. Another way of understanding the lack of middle ground is to see this law as being binary. Like the 0s and 1s in computer code, this law is disjunctive in stating that either something is true or it is not. The idea that there is no such thing as being “a little pregnant” demonstrates this law quite well.

Figure 1.3. Contradictory Instructions

So, when taken together, the law of identity, the law of noncontradiction, and the law of excluded middle provide the basis for the universal foundational criterion of consistency. We use these three laws of thought in everyday discussions involving the most mundane considerations to the most sublime ponderings. Consistency is the cornerstone of the foundation of universal criteria because once it is violated, once we discover that an argument’s premises are inconsistent, there is no further need for discussion or dialogue until the inconsistency is recognized, accepted, and corrected.

These three laws are considered the foundations of rational thought because they disallow people from stating unaccountable inconsistencies and contradictions. So, for example, when the newly inaugurated president of the United States, Donald Trump, boldly proclaimed that the pictures of crowds at his inauguration were falsified and that there were well over a million supporters in attendance; that God stopped the skies from raining on his inauguration even though his wife was holding an umbrella and other members in the crowd (including past President George W. Bush) were all wearing plastic ponchos because it was raining; and that the skies opened and the sun shone down on him because of God, these all violate the three laws of thought that underlie the criterion of consistency.8 Yet Trump is such a good marketer that it appears that he believes that by repeating the same claims, people will come to believe them.

One should now be able to see and understand why consistency is the most important universal foundational criterion in support of our premises, which in turn support our conclusion. For example, during the Senate confirmation hearing of Judge Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, President Trump said that Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony was credible and believable, calling her “a very credible witness.” A few nights later while at a rally in Mississippi, Trump began to belittle and ridicule Blasey Ford’s testimony:

“How did you get home? ‘I don’t remember,’” Trump said at the rally Tuesday in Southaven

“How did you get there? ‘I don’t remember,’ Where is the place? ‘I don’t remember,’ How many years ago was it? ‘I don’t know I don’t know I don’t know ’” Imitating Ford, he added, “But I had one beer that’s the only thing I remember ”9

So again we see yet another example of blatant inconsistency. Such inconsistencies strike at the very heart of what it means to think and act responsibly and undermine logic, hence the need to learn the basic skill set of critical thinking. We need to learn or relearn how to think, for in learning how to think critically and responsibly, we empower ourselves and those with whom we associate with the ability to recognize and call out bullshit whenever we encounter it.

The reason that facts are important, evidence is important, and establishing the truth is important is because it holds people accountable who try to use pretzel logic and biased rhetoric in an attempt to circumvent the three laws of thought, which provide the foundational appeal of consistency to our statements. Without these laws of thought, anything goes. Such a world is far too unsettling, disturbing, and dangerous for us to allow this to happen. It is for these reasons (and more) that consistency is the most important of all criteria when it comes to supporting premises.

TYPES OF CONSISTENCY

When it comes to consistency, there are two types: internal and external. If a person’s ideas, beliefs, or opinions possess internal consistency, then it means that they are related to one another and, relative to the set of premises, commit no errors with regard to either of the three laws of thought. In other words, internal consistency refers to the way in which one’s premises are related to and consistent with each other within a particular belief system. However, there are plenty of arguments, beliefs, and opinions that can be internally consistent.

For example, it is easy to display spectacular internal consistency that demonstrates why I believe that the reason my socks go missing out of my clothes dryer is actually due to mischievous elves. If you try to falsify my claim by setting up video cameras, I will tell you that they are invisible. When you set up a web-like array of laser detectors, I tell you that they do not possess mass. You may try to falsify my claim by spreading flour on the ground around the dryer so that we can see evidence of where the elves have walked, but I tell you they can fly and hover. And because of all of these traits, I can demonstrate the internal consistency of why my socks seem to go missing from my dryer. So, no matter how much you try to falsify my belief, I can always come up with disprovable responses to any scrutiny and maintain the internal consistency of my belief in mischievous, invisible, flying elves.

Although this argument may seem internally consistent, the conclusion I have provided that elves steal socks out of my dryer and the premises I use to support this conclusion, that is, that they are invisible, possess no mass, and can fly and hover, do not possess any external consistency with the natural world and our understanding of it. In the attempt to confirm such a claim, we might set up traps, motion-detecting sensors, and video surveillance cameras to provide the

empirical evidence and proof required for people to believe that such things as mischievous elves truly exist. However, when no such evidence turns up, what are we to believe? The lack of evidence has failed to confirm such a conclusion. This then leads us to maintain that, although internally consistent to the believer in invisible, massless, flying elves, this argument bears no external consistency with the natural world. And until such a time that the claimant can demonstrate the existence of such beings that is, demonstrate external consistency with the natural world we have no good reason to believe him. So, without supporting evidence that leads me to conclude that invisible mischievous elves really exist in the natural world, I am not compelled in any way to believe such an argument.

The same applies to the case of the Breatharians that is, their belief system maintains a type of internal consistency. And this is because within their group, there are no fact-checkers around to confirm or falsify their successes other than themselves, and any failures reported to the public will be the result of the individuals themselves rather than the system itself. This type of internal consistency is extremely dangerous because it is insulated against counterfactuals, or any attempts to falsify the set of beliefs. It is only when we start to look for external consistency, that is, consistency between beliefs and scientific facts of the natural world, that we see the breakdown of such a particular set of beliefs. Unfortunately, the external consistency of the Breatharian philosophy led to the deaths of at least three people and countless others who became seriously ill.

One of the quickest ways to spot inconsistency is to identify contradictions. For example, whenever someone makes a universal claim whether affirmative (e.g., “I always do ”) or negative (e.g., “I never do ”), you can demonstrate inconsistency in his or her claims by providing just one counterfactual incident. Think of how many people throughout history have stood for specific values and principles like truth, justice, freedom, and dignity only to be discovered to violate these principles. And think of how many times communities have been shocked to discover the inconsistent behavior of their politicians, physicians, priests, coaches, bosses, teachers, and so on. If our premises are not consistent, they will not be valued, and our house cannot stand and will collapse.

Let’s now turn our attention to the four remaining universal criteria that collectively act as foundations on which to anchor our premises.

Simplicity