Manual Of Forensic Odontology

A Publication of

CRC Press

Taylor & Francis Group

6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300

Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742

© 2007 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business

No claim to original U.S. Government works Version Date: 20111012

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4665-0057-0 (eBook - PDF)

This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint.

Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers.

For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright.com (http:// www.copyright.com/) or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users. For organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by the CCC, a separate system of payment has been arranged.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Visit the Taylor & Francis Web site at http://www.taylorandfrancis.com and the CRC Press Web site at http://www.crcpress.com

EDITORS

Edward E. Herschaft, BA, DDS, MA, DABFO Editor in Chief; Professor, University of Nevada – Las Vegas (UNLV), School of Dental Medicine; Professor Emeritus, Medical University of South Carolina, College of Dental Medicine; Forensic Odontologist, Clark County Coroner’s Office, Las Vegas, Nevada; Past President, American Society of Forensic Odontology; Past Vice-President and Fellow, American Academy of Forensic Sciences; Past Vice-President, American Board of Forensic Odontology

Marden E. Alder, DDS, MS, DABFO Editor, Professor, University of Nevada – Las Vegas (UNLV), School of Dental Medicine (Retired), Former Director, Center for Education and Research in Forensics, Department of Dental Diagnostic Science, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; Consulting Forensic Odontologist, Bexar County Medical Examiner’s Office, Past President, American Society of Forensic Odontology; Fellow, American Academy of Forensic Sciences

David K. Ord, BS, DDS Editor, Assistant Professor, University of Nevada – Las Vegas (UNLV), School of Dental Medicine, Chief Forensic Odontologist, Clark County Coroner’s Office, Las Vegas, Nevada, Member, American Society of Forensic Odontology; Associate Member, American Academy of Forensic Sciences

Raymond D. Rawson, BS, DDS, MA, DABFO Editor, Adjunct Professor, University of Nevada – Las Vegas (UNLV), School of Dental Medicine and University of Nevada School of Medicine, Emeritus Professor, University of Nevada System, Forensic Odontologist, Clark County Coroner’s Office, Las Vegas, Nevada, Member, American Society of Forensic Odontology, Past Chairman, Odontology Section and Fellow, American Academy of Forensic Sciences, Past President, American Board of Forensic Odontology

E. Steven Smith, BS, DDS Editor, Professor, University of Nevada – Las Vegas (UNLV), School of Dental Medicine, Professor Emeritus, Northwestern University School of Dentistry, Chief Forensic Odontologist, Clark County Coroner’s Office, Las Vegas, Nevada, Past President, American Society of Forensic Odontology, Fellow, American Academy of Forensic Sciences

(Dr. E. Steven Smith passed on Monday, October 16, 2006 after a long illness. Steven will be missed as a friend and leader in dental education, forensic odontology and oral medicine. After a long career at the Northwestern University Dental School he served as the first Dean of the UNLV School of Dental Medicine and was the Director of the Nevada Crackdown on Cancer Initiative which gathered demographic information about teenage tobacco usage and provided educational programs to encourage cessation of tobacco products among this population. Steve was a charter member of the Psi Omega Chapter of OKU at the UNLV School of Dental Medicine and served as its President for 2005-2006. Dr. E. Steven will indeed be missed and it is with tremendous regret that we must add another asterisked name of ASFO leaders who are deceased to the list in the ASFO Manual 4th edition . EEH, MEA, DKO, RDR)

ConTribUTorS

Marden E. Alder, DDS, MS, DABFO

Susan G.S. Anderson, DMD

Douglas M. Arendt, DDS, MS, v

David C. Averill, DDS, DABFO

Robert E. Barsley, DDS, JD, DABFO

Gary L. Bell, DDS, DABFO

Gary M. Berman, DDS, DABFO

Mark L. Bernstein, DDS, DABFO

Hugh E. Berryman, Ph.D.

C. Michael Bowers, DDS, JD, DABFO

Ashley Bradford, BA, MAR

Mary A. Bush, DDS

Peter J. Bush, BS.

Bryan Chrz, DDS, DABFO

J. Curtis Dailey, DDS, DABFO

Robert A. Danforth, DDS

Sheila M. Dashkow, DDS

Thomas J. David, DDS, DABFO

Stacey Davis, FBI/CJIS Management Analyst

Richard L. Dickens, DDS, PhD

Joseph A. Dizinno, DDS

Robert B. J. Dorion, DDS, DABFO

Scott R. Firestone, DDS

Adam J. Freeman, DDS

Tadao Furue, BA *

Ingrid Gill, JD

Gregory S. Golden, DDS, DABFO

Arthur D. Goldman, DDS, DABFO *

Bernard L. Harmeling, DMD, DABFO *

Edward F. Harris, PhD

Arnold Hermanson, DDS

Edward E. Herschaft, DDS, MA, DABFO

Jeremy A. Herschaft, JD, LLM

Mitchell M. Holland, PhD

L. Thomas Johnson, DDS, DABFO

Gene A. Jones, DDS, MSD

Jane A. Kaminski, DDS

Isaac Kaplan, DDS

John P. Kenney, DDS, MS, DABFO

Thomas C. Krauss, DDS, Diplomate Emeritus ABFO *

Cathy A. Law, DDS, DABFO

Elisabeth Latner, Constable (Hamilton, Ontario)

Philip J. Levine, DDS, MA, MS, MSM, DABFO

William R. Maples, PhD, DABFA *

Curtis A. Mertz, DDS, DABFO *

John D. McDowell, DDS, MS, DABFO

James B. McGivney, DMD, DABFO

Raymond G. Miller, DDS

Harry H. Mincer, DDS, MS, PhD, DABFO

Gene L. Mrava, BSME, MS

Ann L. Norrlander, DDS, DABFO

David K. Ord, DDS

Diane T. Penola, RDH, BS, MA

Lawrence J. Pierce, DDS

Haskell M. Pitluck, JD

Iain A. Pretty, BDS (Hons), MSc, PhD, MFDS RCS(Ed)

Raymond D. Rawson, DDS, MA, DABFO

Richard A. Rawson, JD

Bruce R. Rothwell, DMD, MSD

David R. Senn, DDS, DABFO

Harvey A. Silverstein, DDS, DABFO

Donald O. Simley, DDS, DABFO

Brion C. Smith, DDS, DABFO

E. Steven Smith, DDS *

Richard R. Souviron, DDS, DABFO

Duane E. Spencer, DDS, DABFO

Norman D. Sperber, DDS, DABFO

Frank M. Stechey, DDS

Paul G. Stimson, DDS, MS, DABFO

David Sweet, DMD, PhD, DABFO

Kelly Testolin, JD

Warren Tewes, DDS, MS, DABFO

D. Clark Turner, PhD

Gerald L. Vale, DDS, MPH, JD, DABFO

Allan J. Warnick, DDS, DABFO

Richard A. Weems, DMD, MS, DABFO

Michael H. West, DDS

Edward D. Woolridge, Jr., DDS, DABFO

Franklin D. Wright, DMD, DABFO

Deceased *

PAST PRESIDENTS

AMEriCAn SoCiETY oF ForEnSiC oDonToLoGY

2006 - 2007 Douglas M. Arendt, DDS, MS, DABFO

2005 - 2006 David W. Johnson, DDS, DABFO

2004 - 2005 J. Curtis Dailey, DDS, DABFO

2003 - 2004 Gary M. Berman, DDS, DABFO

2002 - 2003 Marden E. Alder, DDS, MS, DABFO

2001 - 2002 Jeffrey R. Burkes, DDS, DABFO

2000 - 2001 Philip J. Levine, DDS, DABFO

1999 - 2000 David Sweet, DMD, PhD, DABFO

1998 - 1999 Richard H. Fixott, DDS, DABFO

1997 - 1998 John D. McDowell, DDS, MS, ABFO

1996 - 1997 William M. Morlang, DDS, ABFO

1995 - 1996 David C. Averill, DDS, DABFO

1994 - 1995 Robert E. Barsley, DDS, JD, DABFO

1993 - 1994 Peter F. Hampl, DDS, DABFO

1992 - 1993 E. Steven Smith, DDS **

1991 - 1992 George Burgman, DDS **

1990 - 1991 Frank A. Morgan, DDS, DABFO

1989 - 1990 Edward E. Herschaft, DDS, MA, DABFO

1988 - 1989 Wilbur B. Richie, DDS, DABFO **

1987 - 1988 James A. Cottone, DDS, MS, DABFO

1986 - 1987 Haskell Askin, DDS, DABFO

1985 - 1986 Norman D. Sperber, DDS, DABFO

1984 - 1985 Thomas C. Krauss, DDS, Diplomate Emeritus ABFO **

1983 - 1984 Gerald M. Reynolds, DDS, DABFO

1980 - 1983 Edwin E. Andrews, DMD, MEd, DABFO

1979 - 1980 George Morgan, DDS

1978 - 1979 Paul G. Stimson, DDS, MS, DABFO

1977 - 1978 Edward V. Comulada, DDS, DABFO **

1976 - 1977 Curtis A. Mertz, DDS, DABFO **

1974 - 1976 Lester L. Luntz, DDS, DABFO **

1971 - 1974 Robert Boyers, DDS, LTC, DC ** ** Deceased

guide to the numerous tasks performed in the execution of forensic dental casework. Additionally, it is a reference guide to forensic resources available to both the practitioner new to the field and the experienced forensic dentist.

Serious students of the subject should use this book to grasp the challenges of the varied and changing forensic science of forensic odontology and be enticed by this effort to pursue further knowledge of the discipline. To assist the reader in understanding the outcomes desired by reading respective sections of the text, we have added outcome assessments (learning objectives) for each chapter. These appear at the end of each chapter and reflect the didactic, psychomotor and affective skills required to perform the tasks demanded of a forensic dentist. Additionally, a color atlas of typical examples of forensic dental evidence and case-based material is included as a resource.

Finally, a caveat is given to all who read this text and practice forensic dentistry. The conclusions and opinions of every practitioner are critical to the overall fairness and justice that affects the lives of real people. Following the Hippocratic Oath, the health care practitioner promises to do no harm to those who seek help and the forensic practitioner takes the added burden that their opinions will be accurate and correct or others will surely be harmed. In the forensic odontologist’s deliberations, there should never be a sense of shame or failure if one has to follow the example of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and report that “there is insufficient information for a determination.”

There is no room for personal opinion based on emotion, instinct, prejudice, subjectivity or anything less than careful scientifically based study. Accepted techniques and procedures should be used for all opinions and those techniques should be exercised in such a way as to demonstrate careful competency.

It is important to continue the process of developing new techniques and procedures. However, proven techniques founded on evidence based science should always be the primary basis of our opinions. New techniques can be validated concurrently. It is recommended that the practicing forensic dentist maintain a standard policy to perform casework and case presentations by employing at least two standard techniques. Additionally, one developing technique can be added if appropriate to the situation.

A person’s freedom or life should never be jeopardized by sloppy or inexpert forensic dental casework or opinions. There is a high standard demanded for the practitioner in forensic dentistry. One way to maintain that high standard is through mentoring or sharing one’s work product with at least one other competent practitioner for review.

It is often appropriate to include students and always appropriate to include less experienced dentists in mentoring experiences and casework by experienced forensic odontologists. These individuals should not make the decisions and should be considered participants to learn and advance their abilities and provide insight through inquiry. All practicing forensic dentists have had to learn through participation in field work and our discipline should stand out for sharing and cooperative advancement.

The justice system in the United States is based on an adversarial approach to the resolution of legal questions brought before the courts. Competitive criticism among the forensic experts called to assist in this arena can not and should not be tolerated. Disagreement and difference of opinion, yes! Competitive criticism of colleagues and peers, however, is unbecoming and detrimental to the overall credibility of the discipline of forensic dentistry.

We hope and trust that you find this manual helpful in your endeavors to understand the discipline of forensic odontology and function effectively as a scientifically founded, ethical and eager participant in the field.

Edward E. Herschaft, BA, DDS, MA

Marden E. Alder DDS, MS

David K. Ord, BS, DDS

Raymond D. Rawson, BS, DDS, MA

E. Steven Smith, BS, DDS

September, 2006

ACKnoWLEDGEMEnTS To THE FoUrTH EDiTion

The editors wish to acknowledge the support and understanding of our families, and peers. The effort to produce this textbook required many sacrifices from the former and selfless willingness to share knowledge from the latter. Their help provided the environment necessary to complete this project. They are examples of the loved ones and colleagues who enable all of us to provide assistance to the community of man by the practice of our discipline of dental science.

Our thanks to all those who have contributed to this book with their knowledge, experience and patience. They have thereby helped us make this endeavor possible. The first three editions of the ASFO Manual of Forensic Odontology were the stepping stones for this current effort. We acknowledge the foundation that these works provided the current editors as we endeavored to maintain their ability to disseminate the most current evidence based information in the field of forensic odontology

Special appreciation is directed to the text’s peer review committees led by Drs. Iain Pretty and David R. Senn and to the efforts of Dr. Katherine M. Howard, Dr. Nikki R. Norton, and Ms. Nipa Patel in formulating and standardizing the reference sections of the text.

Drs. Raymond J. Johansen and C. Michael Bowers are acknowledged for providing an electronic version of their text Digital Analysis of Bite Mark Evidence Using Adobe Photoshop as a supplement to the 4th edition of the ASFO Manual of Forensic Odontology. This material can be accessed through a secured area of the ASFO web site for those individuals who have obtained a copy of the 4th edition of this Manual.

We would like to acknowledge the American Board of Forensic Odontology for providing the editors with current guidelines for various procedures in forensic odontology. These guidelines have been established by the working groups of the ABFO and are continually monitored and updated as evidence based information concerning respective procedures becomes available.

Everyone involved in this project deserves equal credit and appreciation for their contributions which were often acquired under duress during dangerous, emotional, traumatic and stressful situations involving terrorist acts, natural disasters or tragedies resulting from human error or criminal activity. EEH, MEA, DKO, RDR, ESS x

G:

H:

I

J:

K:

Police agencies are involved in gathering dental evidence when crime scene investigators need assistance developing a case which may require identification of a missing individual or includes a tooth fragment or tooth mark on skin or an inanimate object. Contact local police departments and specifically talk to crime scene analysts or investigation bureau detectives.

Child protective service agencies require the availability of a trained forensic dentist. Their activities are independent of the coroner’s or medical examiner’s offices because the victims they represent may not be decedents. Develop contacts that will introduce you to child protective service investigators and additionally, advocates for battered women and their organizations and shelters.

District attorneys, public defenders, and civil attorneys are resources for involvement as a forensic dental consultant or expert witness. Review past cases involving dental evidence and inform appropriate officials of your interest.

Joining the AAFS and the ASFO will establish your commitment and enthusiasm for the discipline of forensic dentistry. The former organization has eleven sections representing the major sub-disciplines of forensic science. There are over 5000 members of the AAFS in the United States and abroad. Each year, the February meeting of the AAFS is held in a different region of the United States. The majority of active forensic dentists belong to the Odontology Section of the AAFS. Currently, there are 424 members of the Section.

Membership levels vary from Student to Fellow and advancement within the organization is based on research, case work and contributions to the knowledge base of forensic odontology. The AAFS membership includes distinguished experts from various fields. It publishes the Journal of Forensic Sciences six times a year and its membership directory is a valuable aid to the dentist starting in this discipline. The AAFS Newsletter includes a calendar of multi-

disciplinary training programs and meetings.

The ASFO has its annual meeting in conjunction with the AAFS. This organization’s goal is to provide entry level dentists and others interested in this discipline an opportunity to receive training and interaction with its more experienced members. The one day annual meeting consists of presentations on topics specifically targeted to aspiring odontologists. The quarterly ASFO Newsletter contains articles and commentary on diverse subjects in the field and social information on members, their activities, and approved training programs. Additionally, this publication contains a current listing of scientific articles published in numerous peer reviewed journals. Both the AAFS and ASFO provide seed grants for worthy start-up research projects in the field of forensic dentistry.

Currently, there are no full time training programs available in the United States for postdoctoral degrees in forensic dentistry. A week long training program in forensic odontology is offered by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. An extensive course on various aspects of forensic dentistry is offered bi-annually by the Southwest Symposium on Forensic Dentistry. This is sponsored by the University of Texas Health Sciences Center Dental School in San Antonio, which has also initiated a program whereby practicing dentists who want more comprehensive information and practical experience in forensic dentistry than is feasible during the symposium can participate in a one-year fellowship in this discipline. Refer to Appendix B for further details and contact information.

McGill University offers a certificate program in forensic dentistry since 2004. It comprises 24 weeks of theory and assignments taken on the web, in addition to two weeks of hands on practice in identification and bite mark evidence at the Laboratoire de Sciences Judiciaires et de Médecine Légale in Montreal. The latter is believed to be the first forensic laboratory under legislative authority in North America. Refer to Appendix B for further details and contact information.

Other continuing education courses and workshops have been offered by local, regional and national components of the American Dental Association and the American Academies of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology and Oral Medicine. International meetings, symposia and conferences dealing with forensic dental issues have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia and Southeast Asia.

The Bureau of Legal Dentistry (BOLD) is a forensic odontology laboratory at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. This Canadian laboratory is dedicated to fulltime forensic dental research and graduate teaching. The faculty and staff at BOLD apply modern forensic techniques and laboratory analysis to dental evidence to assist in the resolution of legal issues. BOLD is a resource for practicing forensic odontologists and other forensic scientists who deal with teeth, bones, saliva, DNA and dental records (Appendix B).

The Laboratory for Forensic Odontology Research (LFOR) was established in 2006 at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo, School of Dental Medicine. The LFOR faculty is actively engaged in forensic odontology research and associated fields (forensic anthropology, chemistry and geology). Educational activities consist of a senior selective course for dental students and courses which fulfill continuing dental education requirements. Student internships and research projects are mentored by the LFOR faculty. The mission of the organization is to advance research methodology and techniques in forensic research and to educate and disseminate knowledge in this field. The LFOR program also has access to facilities available at SUNY at Buffalo, including the South Campus Instrumentation Center in the School of Dental Medicine and the Gross Anatomy Cadaver Donation Program in the Medical School.

After gaining some experience with involvement in forensic dental cases, the individual maturing in this discipline can develop slide, Microsoft PowerPoint and lecture presentations concerning the subject. Newcomers can purchase a slide collection from the American

Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO). Dental and law enforcement groups are always interested in providing good speakers the opportunity to present to their constituents. These groups need to have regular continuing education. Information related to the forensic dentist’s role as a facilitator in legal problems involving identification, bite mark analysis, mass disaster identification and problems of human abuse are always well received.

One’s first forensic case is often referred by a local agency. The excitement of becoming part of an actual investigation, however, can be fraught with hidden dangers. The dentist involved in a forensic setting must clearly understand that he or she is not an advocate for the agency or the individual that engages their services. The dentist’s quest should be to accurately evaluate and render an opinion that is free from personal bias or agendas. It is normal to want to make the case for the law enforcement or prosecutorial agency that has requested your expertise. The caveat in this situation is to remain neutral. Any true professional understands this role. Do not permit local friendships to influence judgment.

Often the forensic dentist’s opinion is demanded long before the entire dental investigation has been completed. Resist the urge to answer to this request. Defer a response until there is certainty that the opinion to be offered is based on all of the material required to make a scientific determination of the facts. Do not hesitate to consult a more experienced forensic dental mentor, colleague or Diplomate of the ABFO.

The ABFO certifies individuals who have reached a specified level of experience and training. Application for certification is voluntary and applicants are granted Diplomate status after successful application, review of case documentation, personal references, and completion of a three day didactic and practical examination. One hundred and thirty three dentists in the United States, Canada and Europe have attained Diplomate status in the ABFO. Of these, 90 are currently affiliated with a legal agency and/or are active in case work and consulting.

CHAPTER 2

HUMAN IDENTIFICATION

“A complete life may be one ending in so full an identification with the oneself that there is no self left to die.” Bernard Berenson – American art critic (1865-1959)

Introduction

Discovery of an unidentified body requires a significant effort on the part of public authorities to reach a resolution. It is important for the family and other loved ones to come to an understanding and proof of the loss of someone important in their life. It is fundamental to our society based on law to have scientific proof before death certificates can be issued, insurance payments assigned, public benefits allowed, or estate and marital issue resolution.

The key statement here is proof not opinion. There needs to be a high degree of scientific certainty related to the determination of identity of remains. Tragic errors are not common in forensic dentistry, but there are dramatic examples of misidentification. Each case is important and has significant ramifications if manipulated or misunderstood.

The process of identification and the specific method used depends somewhat upon the circumstances. If a sudden death of a known individual occurs, it is common to depend upon personal recognition for identification. Thus, a parent will commonly identify their son or daughter as the victim of an accident or overdose.

It is difficult to precisely determine the number of misidentifications caused by personal recognition, but it has been estimated that as many as 30 percent of identifications by this method are in error. That error can be caused by the emotion of difficult circumstances. There are cases of purposeful misrepresentation of the identity as well as simple mistakes and it is always best to have a scientific confirmation to anyone’s statement of identity.

It is always important to remember the basic principles of identification:

- The identification of victims must be accurate, and based on scientific principles.

- It takes training, organization and experience to identify victims accurately

- The difficulty of identification increases exponentially with the number of victims.

The process of identification should start with gaining as much information as possible about the person represented as unknown remains. Age, gender, stature, race, and medical history are issues with which the forensic dentist and physical anthropologist can assist. Fingerprints and DNA determination are known to be reliable and will be discussed in detail.

The thorough evaluation of the human dentition of an unidentified person could be accurately referred to as an oral autopsy. Complete dental identification involves processing antemortem and post mortem information, doing a comparison of the information, forming an opinion and preparing a report of the findings. It must be emphasized that, when dealing with the post mortem dental evidence the forensic dentist must secure the proper authority to collect and process the dental evidence. A coroner or medical examiner must give permission for the dentist to view, chart, photograph, videotape, or surgically remove the jaw segments. It may also be necessary to gain access to the oral cavity with incisions just as the physician medical examiner who evaluates internal organs. Failure to gain such approval may place the dentist at risk for legal action.

The American Board of Forensic Odontology Body Identification Guidelines should be followed in all forensic dental identification cases and can be found at www.abfo.org and in Appendix C. These guidelines provide an excellent source of information for novice and expert alike in the collection and preservation of post mortem dental evidence, sources of antemortem data, protocols for the comparison of antemortem and post mortem evidence, and categories and terminology for body identification.

Radiography is certainly an essential diagnostic tool, but ultimately, the visual and photographic inspection of the condition of the dentition is basic and fundamental. Every attempt should be made to protect the viewable condition of the face, and there are methods to facilitate that visual inspection. Mouth props, bite blocks and retractors are useful and intraoral probes and lenses have been described and used to good effect. In some cases the resection of jaws is well justified and there are approaches other than the standard incision at the corner of the mouth that can protect the facial architecture for potential viewing for family or funeral services.

The condition of every tooth should be recorded. Missing teeth should be noted and where possible, antemortem or post mortem changes indicated. We have found that once the oral autopsy is concluded, it is difficult to reacquire the victim remains to verify information. It is always best to thoroughly record the evidence at the time of examination and to depend upon that information to guide the search for identity. This situation is particularly critical in the mass disaster setting, because of the difficulty associated with multiple handling of the remains.

A standard chart should be completely filled out for every unidentified set of remains. When dental records come into the examiners control, they should be translated to that standard chart format so that errors in charting can be minimized. The various methods of charting are a constant source of irritation and error and can greatly complicate the process of identification.

Ultimately, the comparison of radiographic features represents a gold standard for identification, but the use of chart recordings is most often the screening method that leads to that final comparison. Standardization of charting is very important to accurate identification by dental experts. Harvey described the history and development of dental charting in his textbook, Dental Identification and Forensic Odontology. In 1861 Zsigmondy modified an old system and developed the quadrant notation also known as the Palmer system. This method is still used today in the United Kingdom, parts of the United States of America and Japan.

By 1891 Haderup used the + and – sign to precede the tooth number for upper or lower arch. The upper right central incisor is represented by the symbol 1 + and the upper left central incisor would then be represented as + 1. This was useful for the typewriter and teletype. A number of Scandinavian and other European countries adapted to this method.

The Universal System was basically developed when Parreidt abandoned quadrants in 1882. Although not used universally, despite its name, it is taught in many dental schools in the U. S., Canada, and the United Kingdom. It is time for the adoption of a universal system and it is amazing that there are still U.S. dental schools teaching different systems.

It is also time for an easily accessed central repository for dental and other information for all missing persons. The U. S. Department of Justice publishes the National Incidence Studies of Missing, Abducted, Runaway, and Throwaway Children (NISMART2) at http:// www.missingkids.com/en_US/documents/ nismart2_overview.pdf

Additionally, the National Dental Image Repository (NDIR) provides an image repository for law enforcement agencies in the United States that wish to post supplemental dental images related to National Crime Information Center (NCIC) Missing, Unidentified, and Wanted Person records in a Web environment (refer to Chapter 3, Multiple Fatality Incident, Dental

Photographs are taken at all 27 possible positions. Each photograph has a unique orientation, slightly different from all others. The 27 negatives should be contact printed. The best match is selected from the contact prints. The corresponding negative is then enlarged to life size. Measurements taken from the skull give information to allow the skull photograph to be enlarged to life size. The mesiodistal dimension of several teeth taken as a group is one of the easiest to measure dimensions that can be used to enlarge the photograph to life size.

Attention is now turned to the antemortem photograph. If possible, the original negative is obtained. If this is not possible, the antemortem photograph is photographed to yield a negative. The negative will be blown up to life size. Note the teeth that are visible on the antemortem photograph. Measure these same teeth on the skull. Use this dimension to enlarge the antemortem negative to life size. The negative is placed in an enlarger. The enlarger may have to be turned so that is projects on the wall, to accommodate the amount of enlargement.

Kodak Fine Grain Release Positive Film is exposed on the enlarger.

Release positive is a transparent plastic type of film that can be exposed on an enlarger; the resulting print is a transparency suitable for superimposition. The two life size photographs necessary for the superimposition are now ready. The life size photograph of the skull is secured on a flat surface. The transparency with the life size print of the antemortem photograph is now placed on top of the post mortem film. The transparency is now precisely positioned to allow maximum overlap of similar anatomical features.

The experience and judgment of the forensic dentist is now used. Points of comparison in a photographic superimposition are rarely as significant as even one amalgam restoration in a regular dental identification. The concordance of the following features is noted: outline of the skull compared to the soft tissue outline of the face, nasal aperture to nose, orbit to eye, brow ridges to eyebrows and forehead, zygomatic process to cheek bone support, and most important, exact

Figure 2-4: The axes and points established Figure 2-5: Skull placed in bowl on lazy for later comparison Susan.

superimposition of the teeth in both size and angular position.

Gross discrepancies between the two films will serve to rule out the individual as the deceased. If the discrepancies are minor, there may have been an error in selection of the proper photograph of the skull. Another skull photograph may be selected, enlarged and printed, and then superimposed. In offering an opinion in this type of identification, the forensic odontologist must be very careful. When all anatomical details match, but no other detail rich feature is found, the choice of a consistent with opinion is most appropriate.

The presence of a detail rich feature such as brow furrow, skeletal trauma or obvious skeletal disfigurement may allow the forensic investigator to give the opinion of positive identification by the superimposition of skeletal and photographic images. For courtroom testimony, the properly oriented antemortem and skull life size photographs can be mounted side by side. Two video cameras are then placed at identical distances from the photographs and focused, one on each photograph. A stereo optic camera set up is then hooked up between the cameras and the photographs are then superimposed over each other and videotaped at this same time.

If there are problems with the antemortem photographs (blurring, fading, over or underexposure, etc.) it is possible to recover lost detail or sharpen unclear detail using computer enhancements of the photographs. There are many such techniques, but E.I. DuPont Co. in Delaware has the equipment and techniques to attempt to enhance otherwise unacceptable photographs. It is desirable to gain experience in facial superimposition when there are other scientific methods of identification available.

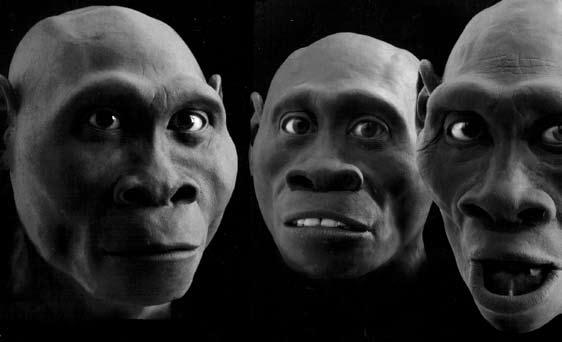

Facial Reconstruction

Facial reconstruction is another useful method of indicating possible identity. The basic process is illustrated in the following figures and the workup must be considered subjective. There has been extensive work to establish the normal soft tissue thickness at various

anatomic points on the skull. These thickness values are known for different race types, both sexes and various age ranges, but they must be considered average values statistically.

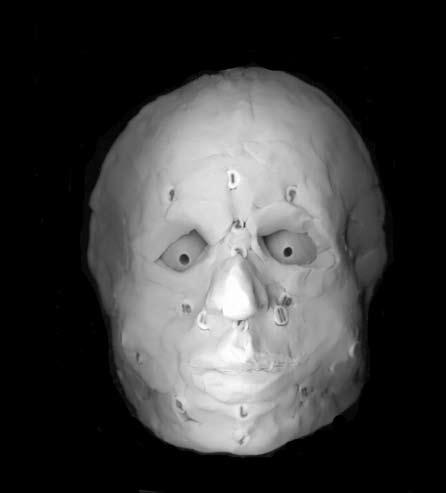

The skull can provide useful information regarding the sex, age and racial type of the unknown individual. DNA evidence can now confirm this information so that the facial reconstruction is as accurate as possible. Once this basic information is ascertained the process of facial reconstruction illustrated in Figures 2-7 through 2-11 can be undertaken. Essentially, standard points are located on the skull and depth markers are attached to the skull at each of these points. Charts published in the anthropologic forensic literature and provided in Appendix D of this text are used to determine tissue depths on the skull based on age, sex and racial characteristics observed.

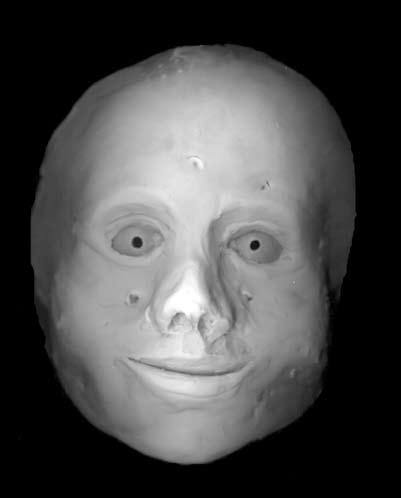

There are various ways of reproducing the skull, so that the reconstruction can be accomplished on material other than the skull. Three dimensional imaging or various impression techniques can be used to protect the original skeletal evidence. The various accepted anatomic points can then be marked with erasure material or clay of the average thickness for that individual anatomic point. The tissue between those points is then built up until the face takes shape. The most subjective aspect of the whole process relates to the eyes, nose, lips, ears, and hairline and style. Once the reconstruction is finished it can be photographed and published in an effort to gain attention.

If an identity is unknown and skeletal material is present, then a facial reconstruction will possibly allow for a public recognition of a missing person. More scientific methods can then be used to provide a positive identification.

General Technique

All materials are laid out on a table where they can be undisturbed until finished. Forensic dentists would be well advised to try several reconstructions to gain appreciation for the possibilities and difficulties of this important technique.

Figure 2-10: Illustration of the process of adding clay until the general facial contours are finished. The difficult decisions are regarding the expression wanted, e.g., closed lips, smile, frown, or sneer

Figure 2-11: The final result will certainly depend upon the skill and experience of the reconstruction artist. When finished, the creation can be scanned or photographed for public display and/or publication.

1892, the British anthropologist, Sir Francis Galton established that fingerprints were not only unique and individual but permanent. His calculations determined that the probability of two different individuals having the same fingerprint were1to 64 billion.

Galton is credited with defining the identifying characteristics of fingerprints. These Galton

details were modified by Sir Edward Henry in 1901 and remain the basis for the Henry Classification System which is still used for the non-computerized classification of fingerprints in English speaking countries.

The use of fingerprints in the United States began in 1902 when the New York Civil Service Commission fingerprinted job applicants.

Identification of criminals also began in New York the following year when the State prison system commenced the routine practice of fingerprinting its prison population.

Throughout the 20th century the science of fingerprinting became firmly established and recognized not only as a means of resolving issues of identification in criminal and civil legal settings but for its uses in military identification as well. Repositories of fingerprint information were created, managed and shared among legal agencies through data bases established by the FBI Identification Division and such foreign agencies as INTERPOL.

In 1999, the Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS) was established by the FBI, Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division. This system permits fingerprint information to be matched through automated computer searches which have the ability to rapidly scan all fingerprint records in the files for a match (Figure 2-12). Once the proper information is acquired, it can then be electronically transmitted to the requesting agency. As of this printing of the ASFO Manual of Forensic Odontology, the IAFIS system is the largest repository of fingerprint information in the world with over 47 million subjects in the Criminal Master File.

There are other sources of fingerprint information and some states keep their own files of non-criminals. Nevada takes fingerprints on all workers in the gaming industry and the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms records fingerprints on licensed firearm dealers and owners of Class III and IV weapons.

The system, which is in service 365 days a year, incorporates the fingerprint information with corresponding criminal history information which has been submitted voluntarily by state, local, and federal law enforcement agencies. It has been instrumental in helping police and civil agencies resolve questions of identification involving missing individuals, amnesiacs, homicides, robberies, mass disasters and other criminal and civil issues.

The IAFIS services provided law enforcement includes the following areas:

-Ten-Print Based Fingerprint Identification Services:

- Criminal Ten-Print Fingerprint Submission

- Civil Ten-Print Fingerprint Submission

- Latent Fingerprint Services

- Subject Search and Criminal History Services

- Document and Imaging Services

- Document.

- Fingerprint Image Services

- Photo

- Remote Ten-Print and Latent Fingerprint Search Services

Many medical examiners have access to digital fingerprint recording equipment and crime laboratories in most jurisdictions have access to cabinets and equipment that can recover fingerprints from inanimate objects. (Figure 2-13)

Although the unique, individual and permanent features ascribed to fingerprints by Galton make them tremendously advantageous as an identification tool, there are some disadvantages to having this method as the sole means of identification. In the forensic setting, a body may be discovered in a decomposing, burned or skeletonized status. Thus, fingerprint retrieval from the epidermal soft tissues for comparison in the IAFIS or any other data base would be precluded.

Dental Identification

General Dental Participation

There are many ways in which the private practicing dentist and his or her team members can be active participants in forensic dentistry within the framework of their own dental practice. Recognizing and reporting the signs

the view that it is presently of limited use in establishing identification through dental means. In the absence of an organized database of dental characteristics, the Board’s position is that conventional dental records, such as dental radiographs would provide more useful information in many cases.

Recognizing, Documenting and Reporting Suspected Cases of Abuse and Neglect

The importance of the dental team’s role in recognizing, documenting and reporting suspected cases of abuse and neglect cannot be overemphasized. Because 65 percent of all physical child abuse and 75 percent of all physical domestic violence results in injuries to the head, neck, and/or mouth, the dental professional is often the first person to render treatment to abuse victims. This provides us with the opportunity to interrupt the chain of events that threatens the life and well being of the victim. By learning the signs and symptoms of abuse, knowing how to document what is seen, and by fulfilling our legal duty to report suspected cases of abuse, the dental professional may help to mend a family in distress or save the life of a helpless child or adult. This topic is treated in more detail in Chapter 5 - Human Abuse.

Participating in DMORT or State Identification Teams

Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team (DMORT) is a federally funded organization consisting of civilian volunteers in the forensic specialties, including dentistry. It is currently a part of the Department of Homeland Security. When a coroner’s office asks for help in dealing with a disaster that overwhelms the resources of the local death investigation agency, DMORT may deploy a team or teams of its members to assist. The team members become federal employees when activated. Membership in DMORT provides private practicing dentists with the opportunity to obtain training and forensic experience, while still continuing their private practice. However, the number of DMORT positions is limited, and vacancies are not always immediately available.

In some states dental identification teams also exist at the state level to assist local coroners when needed. California, for example, has the California Dental Identification Team (CALDIT), which will function as part of the Coroners Mutual Aid Program. This team is composed of dentists who are affiliated with local death investigation offices and are experienced in the investigation of mass fatality incidents.

Nevada set up a state dental identification team funded through the Department of Emergency Management (FEMA). It maintains equipment palletized and housed at the coroner’s office in Las Vegas, but is a state-wide resource and available to FEMA.

Response to Bioterrorism, and the Provision of Emergency Health Care

The events of September 11, 2001, followed by the October anthrax contamination of the United States mail, forcefully demonstrated that our nation is vulnerable to major acts of terrorism, including those involving biologic agents. Organized dentistry has proposed that our profession join in the ongoing efforts to:

- Develop an effective response to acts of bioterrorism.

- Fully utilize the knowledge and skills of health care workers in a major disaster in order to assist medical workers in providing care for the injured.

Efforts are underway to develop legislation authorizing dentists, in a federally declared emergency, to perform various procedures that are normally outside of the dental practice acts. There are related efforts to provide appropriate immunity from legal liability for these actions. Action is also being taken to develop an emergency system of registration in advance of need to identify those individuals who have taken the necessary training and are qualified to serve as voluntary workers in a major emergency.

As these programs are developing, dentists are encouraged to use existing resources to improve their knowledge and skills in emergency medicine. For example, courses are now available in emergency medical care for dentists in the armed forces, and are beginning to also become available in the private sector. Related training can also be taken at institutions that offer paramedic training programs, as well as shorter courses offered by the Red Cross. Courses dealing with emerging medical diseases and bioterrorism are available in continuing education programs offered at dental schools and dental society educational programs. Dentists who avail themselves of these educational opportunities will gain knowledge that may ultimately benefit patients in the office, family members at home, and may also benefit the community at large.

Forensic Imaging Techniques

Photography

Photography is used by the forensic dentist to document clinical findings in identification, person abuse and bite mark cases. The well-made photograph surpasses, but does not replace, written or verbal descriptions or sketches because photographs are more accurate, graphic, objective and verifiable. Photographs capture perishable or transient evidence. They allow case reconstruction for investigators and assist in illustrating findings to jurors and colleagues. They provide the technically accurate working materials in bite mark analysis. Photography can also be used to discover unsuspected findings by extending the range of human visibility, employing such techniques as microphotography, infrared and ultraviolet photography.

As with all scientific and evidence photography, the objective is to standardize a technique to produce consistent and accurate results. Artistic composition is sacrificed in favor of sharp, well exposed, labeled images that provide a true and accurate representation of what was observed by the investigator. To affect this result, the forensic dentist must have background knowledge of photographic

theory and must be accomplished in the use of his or her equipment. As is the nature of forensic dentistry, the photographer and the equipment must be constantly in a ready state for instant implementation.

Luntz cites three reasons why the forensic dentist must be photographically self-reliant:

- Police may not be available to make needed photographs

- Police may not be trained or equipped to make close-up photographs

- Chain of evidence is shorter

Additionally, an illustration composed directly by the forensic dentist renders a more accurate interpretation of the dental findings than one produced by an intermediary instructed to take the picture. Therefore, photography, which is merely an adjunct in most fields of dentistry, is absolutely integral to the practice of forensic odontology. Further, detailed discussion of this topic is found in Chapter 6 -Technological Aides in Forensic Odontology.

Radiography

Dental radiography is of prime importance in the identification of human remains. The comparison of high quality antemortem and post mortem radiographs whether film-based or digital provides a multitude of maxillofacial, tooth and dental restorative characteristics distinguishable to an individual which may be observed and compared. Radiographic images are objective and much less susceptible to human error when compared to written dental charts and records. In fact, it is common procedure for the dental images in a forensic case to serve as the gold standard whenever there is a discrepancy or suspected error in the patient’s antemortem written record or charting, and in the miscoded post mortem record.

Most forensic odontologists will agree that it is often the case that a single dental radiographic image can lead to a positive

neck. Efforts should be made to radiograph the post mortem specimen with panoramic radiography. However, with badly fragmented and/or missing parts, this may not be feasible. Consequently, when attempting to emulate antemortem panoramic views with post mortem intraoral radiography it may be helpful to reverse the beam direction by placing the film or sensor on the buccal or facial and directing the beam from the lingual. This is especially true if you are using anatomical rather than restorative features for the comparison.

Exposure Energy With Forensic Specimens

Exposure energy sufficient to obtain images of proper density is often greatly reduced in forensic specimen due to the lack of normal tissue overlying the dental structures. Accordingly, either the exposure time or mA setting should be reduced by one-third in most cases and by as much as one-half in skeletonized and burned remains to avoid images that are overly dark.

Film Processing

Film processing procedures and machine maintenance is often overlooked when conducting forensic analysis, particularly in mass disaster settings where a certain amount of chaos and urgency may be a factor. Indeed, due to the serious medico-legal issues involved in the usual forensic case, this can be a critical mistake with severe consequences even beyond that of the normal dental private practice setting.

Proper use of fresh chemicals and following the manufacturers’ recommended processing steps will help ensure images of high quality that will remain so over great lengths of time. Shortcuts such as using higher processing temperatures with shorter developing time or an inadequate film wash such as with the cheaper processing units will result in failure and discoloration of the image over time. The endodontic setting of many film processors can also create films which are not of sufficient archival quality. This error is particularly serious in that it is immediately apparent and

may only be observable over a certain period of time.

Another common mistake involves outdated daylight loaders in which the colored filter is inadequate to prevent film fog with many of today’s faster film speeds. The color filter should be a dark, ruby-red and should not be used directly under fluorescent lighting in order to avoid film fog. Additionally, remember that time is an important factor with daylight loaders. Film left unwrapped for lengthy time periods within a daylight loader may become fogged. It is also essential that images be mounted and labeled as soon as the series comes out of the dental film processor to eliminate an incorrectly labeled film series which would very lead to misidentifications.

Forensic Image Comparison and Image Viewing Conditions

Even with the highest degree of image quality, detailed dental structures cannot be clearly observed when films are held up to ceiling lights and open windows for viewing. Post mortem and antemortem image comparison should be done under proper viewing conditions, particularly when the dental findings are small and bone structures, pulp chambers and root patterns must be seen and compared. This requires a properly sized or masked X-ray view box in a room with subdued background lighting. Images compared on computer monitors should also be done in subdued lighting and the eyes should be adjusted to the subdued lighting.

Issues with Duplicated Radiographs

Most dentists in the United States orient dental films on the view box and in film mounts with the orientation dimple of the film facing upward; away from the view box surface. This establishes the orientation of the film series as if the viewer is facing the patient.

However, a very common concern in forensic dentistry is the improper orientation of duplicate antemortem radiographs where the dimple of the original film can be seen, but not felt. Even if it is assumed or proven that the duplicating film was oriented properly during duplication,