Find some of Canada’s finest authors, photographers and artists featured in every issue.

is to promote Canadian culture by bringing world-wide readers some of the best Canadian literature, art and photography.

Devour: Art and Lit Canada

ISSN 2561-1321

Issue 021

Summer 2025

5 Greystone Walk Drive Unit 408

Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M1K 5J5

DevourArtAndLitCanada@gmail.com

Poetry Editor – Bruce Kauffman

Review Editor – Shane Joseph

Prose Editor – Brian Moore

Photography Curator – Mike Gaudaur

Feature Photographer – Bob House

Editor-in-Chief – Richard M. Grove

Layout and Design – Richard M. Grove

Dear Readers:

Welcome to this 21th issue of Devour: Art & Lit Canada. As usual we are bringing you some of Canada’s most talented writers, poets and photographers.

As always, thank you to our ongoing faithful section editors. In no special order, thanks to Brian Moore, Bruce Kauffman, Shane Joseph and Mike Gaudaur. Thankyou to all of the contributors that make Devour a success.

We hope you will let not only your Canadian but also your international readers, family, and friends know about this all-Canadian magazine. See you between the pages.

Richard M. Grove otherwise known to friends as Tai.

– Canada Coast to Coast to Coast – Photography Curator –Mike Gaudaur – p. 8–13, 49, 50, 51, Back Cover

– Feature Photographer – Bob House – p. 6, 14–19

– Canada in Review – Editor – Shane Joseph and Reviews – p. 20–31

– Poetry Canada – Editor – Bruce Kauffman, Poems and Pics – p. 32–79

– Photographs by Anna Di Nardo – p. 80–85

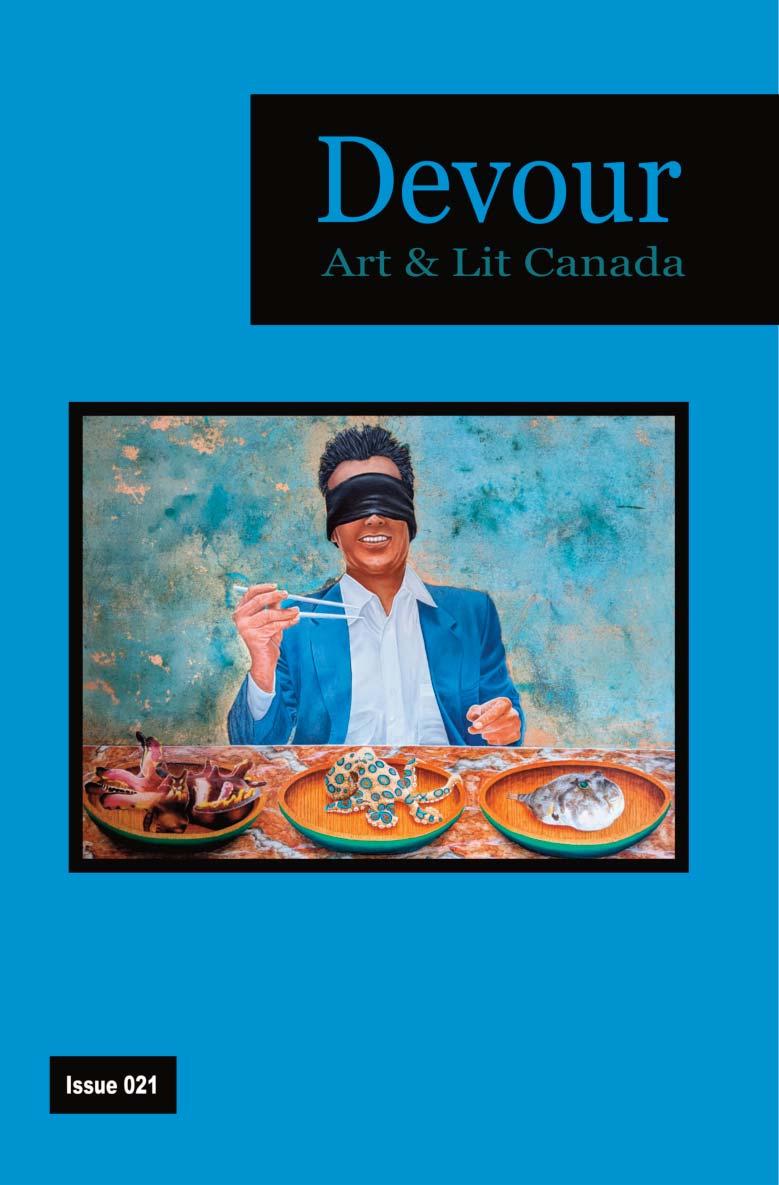

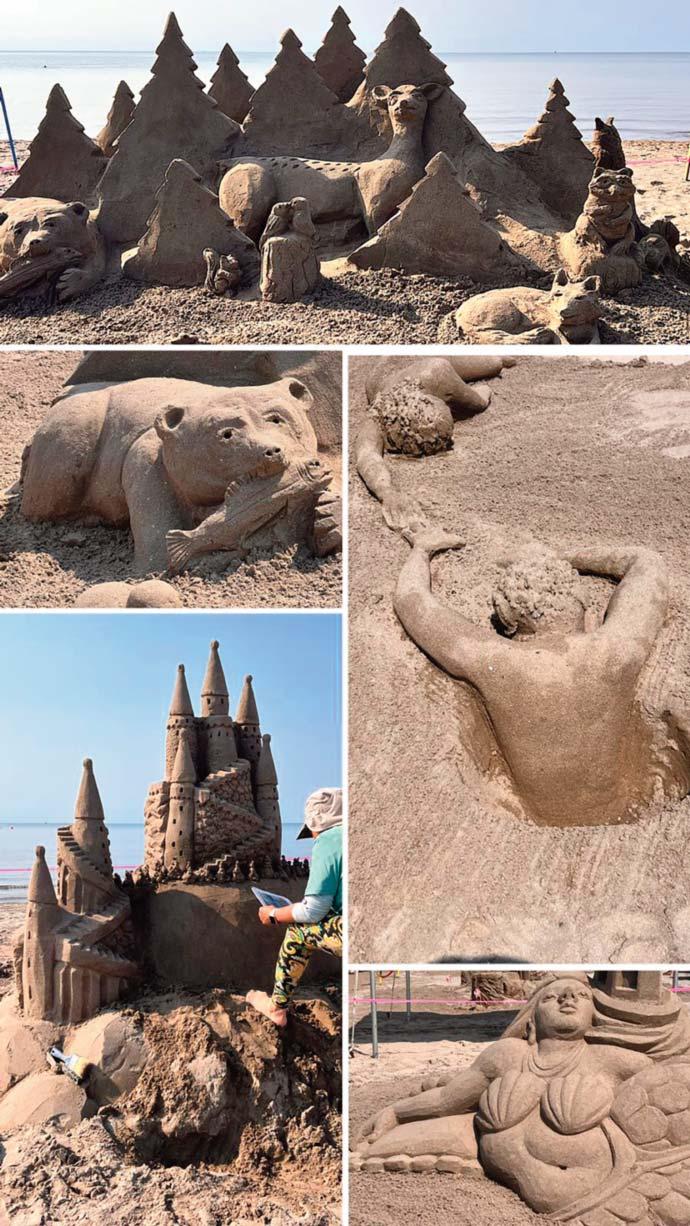

– Surrealism at its Satirical Best: : Bob ‘Omar’ Tunnoch , Artist / Musician / Songwriter – Essay by Richard M. Grove – Front Cover, p. 4, 86–91

– CanLit Essays on CanLit Authors

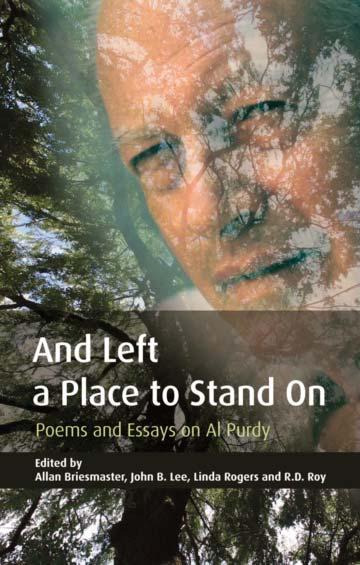

– A Miguel Ángel Olivé Iglesias review essay on: CanLit Poet John B. Lee in a Few Pages – p. 92–96

– A Richard M. Grove review essay on: FourSquare Poems by James Deahl – p. 97–103

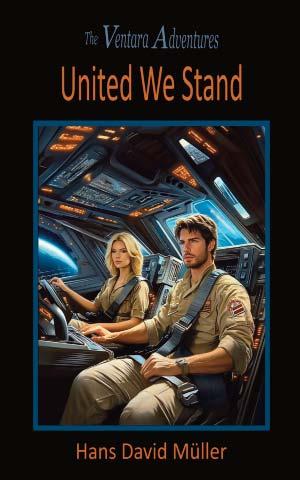

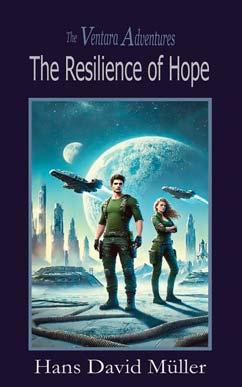

– A Brian Way review essay on: And One for All by Hans David Müller – p. 104–108

– A Anna Mutala review on: The Ventara Adventures by Hans David Müller – p. 109

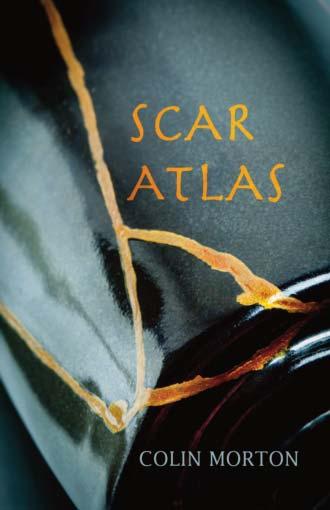

– A Richard M. Grove review essay on: Scar Atlas by Colin Morton – p. 110–113

– Canada in Prose – Prose Curator – Brian Moore – p. 114 – Story Heights by Mathea Treslan – p. 115–120

Photography Curator Mike Gaudaur

After more than four decades of making images that show what something looks like, I am gradually shifting towards making images that show more of what things feel like. I find that the images I capture are more graphic and minimalist. However, I think it is my processing of images that is changing even more. I am less concerned about ensuring that every little detail is clear and sharp, and more concerned about enhancing a mood and

guiding viewers to see just what it was that caught my eye with nothing to distract them. With this collection of images I have been experimenting with colour grading that shifts tones to enhance mood.

Mike has spent the past 12 years teaching photography during school terms and photographing on safari during the term breaks. Online training and countless late nights of experimenting resulted in Mike developing a full complement of digital skills. After returning to Canada he was able to formalize his training and become an Adobe Certified Expert in Photoshop. Mike is a never ending learner, experimenter, explorer. His learning didn't stop with Photoshop. He naturally grew into working with Lightroom, On 1 Perfect Photo Suite, and the Nik Software collection. His advanced skills in the digital technology have allowed him to push his photographic style even further.

You can find Mike at: https://www.mikegaudaurphotography.com/ or contact him by email at, mike.gaudaur@gmail.com

Since discovering the joys of the photographic medium in the summer of 1974, I have dedicated an enormous amount of energy to ensuring the acceptance of photography as art. As a forum for creative expression, I am constantly sharing my work through workshops, lectures, and exhibitions.

I believe that truly understanding the magnitude of the medium goes beyond simply picking up a camera and exposing film. It also involves appreciating the classic photographers who helped shape photography into what it is today. I’ve always been intrigued by both the quality of their work and the somewhat bohemian lifestyle of greats like Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and Walker Evans, to name just a few. I’ve spent a great deal of time immersed in their expressive creativity, especially during photography’s formative years.

With over 50 years of experience behind the camera, I honed my skills during the analogue era, shooting film and spending countless hours in the darkroom, before grudgingly transitioning to the digital world in 2004. I operated a commercial photo studio and gallery in downtown Belleville for 20 years.

I’ve also served as Chair of the Quinte Arts Council and sat on the Board of the Quinte Ballet School of Canada. My photographic and fine art interests are wideranging, including landscapes, dance, portraits, and fashion. I have had the privilege of exhibiting my work in numerous gallery shows at the BPL Library Galleries. I continue to enjoy talking about photography and sharing it with anyone willing to listen.

Instagram: @bobhouse49

Book Review Editor

Shane Joseph

Dear Readers:

In this edition, we feature reviews on a range of genres: novels, memoir, and poetry. The novels take us to distant lands: Morocco, Egypt, Chile, Panama and India; and from time as distant as a hundred years to two thousand five hundred years ago. The memoir and poetry ground us back home in Canada, ranging from the Prairies to the West Coast – so get ready to travel.

Shyam Selvadurai’s Mansions of the Moon covers the life of Prince Siddhartha, who went onto become the Buddha, narrated from the point of view of his abandoned wife, Yasodhara. It is a tale of women’s early emancipation struggles against a rigid patriarchy in India, rather than a how-to guide for achieving Nirvana.

In Tiaris, author D.M. Buehler takes us via a 14-year-old Canadian teenager into the mangrove swamps of Panama, and then swings us in a time loop back a hundred years to the building of the Panama Canal. The human and environmental costs of this mega project, which has propelled global maritime trade, are laid bare.

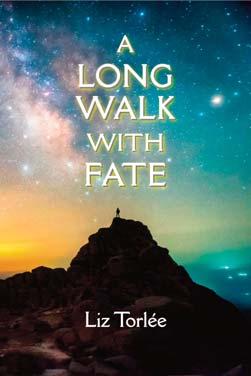

Liz Torlee returns to her favourite subject of Fate, when characters from her two previous novels, and some new ones, come full circle in A Long Walk With Fate. Her characters finally understand who they are and how they connect despite coming from different ends of the planet. Guilt and Forgiveness duel it out across Morocco, Egypt, Chile and Canada until one of those imposters wins.

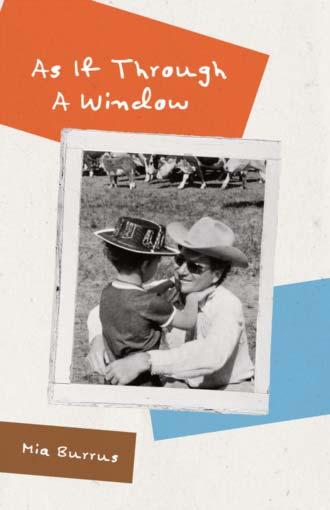

In the short memoir of her father, As If Through A Window, Mia Burrus takes us into the life of a prairie rancher and her quest to discover the identity of a mystery man whom everyone knew, except her.

Rounding up the reviews is a collection of poetry, Bonememory, by Alberta poet Anna Veprinska, in which she explores topics as diverse as Ukranian Matryoshka dolls, secret Indigenous burial sites in Kamloops, and the practice of Prayer. Canada’s colonial past and Auschwitz are boldly compared and the question is asked: “How much of this country is an unmarked grave?”

We hope you enjoy these thought-provoking reads this summer!

Shane Joseph Book Reviews Editor

Author: Liz Torlée

Publisher: Blue Denim Press

ISBN: 9781998494118

Number of Pages: 250

Published Year: TBR October 2025

Reviewed by Janet Trull

Where do we come from? Where do we belong?

Author Liz Torlée examines the way these essential questions haunt her characters as they seek answers around the globe. A Long Walk With Fate weaves universal themes of love, forgiveness and belonging into a fast-paced narrative. Readers who have come to expect international intrigue in Torlee’s first two novels (The Way Things Fall, and In Love With The Night) will not be disappointed. Her diverse characters are fiercely loyal, emotionally fragile, and sometimes self-destructive.

Meet Aiden Quinn. Growing up in Vancouver amid the detritus and chaos of his mother Maggie’s drug addiction, he struggles to trust the adults in his world until he is adopted by his aunt, Dorothy, who raises him as her own. When Dorothy dies, Aiden starts connecting the dots of a mystery that began before he was born. Photographs and strange coincidences lead Aiden into the depths of a shadowy past. Puzzle pieces seem irretrievable until he discovers a possible connection to the identity of his father.

Is Aiden related to the famous Canadian artist, Steven Farrow? Could his own artistic talent be part of a familial heritage? The author deftly brings together a deep appreciation of visual arts and world history as Aiden is transported from Canada to attend an art festival in Morocco. In this vibrant setting, relationships meander into dark and complex alleyways. Aiden, distracted with issues of anger, abandonment and youthful folly, stumbles through a maze of confusing possibilities. Along the way he must reconsider the motives of both allies and adversaries, confront his ghosts, and learn to trust in fate.

“The lives of the people they had loved in the past and would love in the future — all were meant to intersect, fuse inextricably together,” Torlée writes. Her characters become endearing as their struggles and demons are revealed, confronted and resolved. Like a river, the theme of belonging carries them along on a turbulent current of self-discovery. “Guilt is the heaviest of burdens,” writes Torlée, “but the inability to forgive is heavier still.”

A Long Walk With Fate reminds the reader how much lighter life’s journey is when we release our burdens. Lukas, a character with the wisdom of a much older person, completes the metaphor of a jigsaw puzzle when he says, “You think one piece goes in an empty place. It’s got the right colours, so you try to make it fit, but it won’t go in. It belongs somewhere else.” The world seems vast and lonely when you are seeking a place to belong, but home is never farther away than your very own heart.

Liz Torlée lived in England and Germany before emigrating to Canada. Much of her writing is rooted in the idea of fate and the mythology of the night sky — fascinations since she was a child. Her love of the mystical beauty of desert landscapes has inspired many of the settings in her novels. Liz and her husband live in mid-town Toronto. Her previous novels on the exploration of the theme of Fate are The Way Things Fall (2020) and In Love With The Night (2022).

Janet Trull is the author of two critically acclaimed collections of short fiction, Hot Town and Something’s Burning, published by At Bay Press. Her essays and awardwinning stories have appeared in the Globe and Mail, and Toronto Star, among others. Her latest novel, End of the Line (Blue Denim Press), was released in 2023.

Author: Mia Burrus

Publisher: AoS Publishing

ISBN: 9781998662463

Number of Pages: 73

Published Year: 2025

Reviewed by Felicity Sidnell-Reid

Review

“The singular act of the weekend was tossing your ashes in the summer breeze. They fell into the startlingly green grass. I see you still when I see the prairie—all horizon. Though you, too, are gone the way of the bison, you are there in the grass, you are the grass, the prairie, the past.”

“This little book” is how Mia Burrus, poet and multimedia artist, describes her memoir of her father Étienne Burrus, his life and passions. It may be little, but it is extraordinarily rich in its mixture of forms; poetry, pictures, photographs, letters, documents and recollections from a variety of voices including the author’s. These fascinating vignettes take the reader on a “voyage of discovery” that draws a picture of Étienne and the ranch in the semi-arid Palliser triangle that absorbed his energies for half his life. It also follows his daughter’s search for the man behind “Mr. B”, a character “well-known to others but a mystery” to her.

The book is available for pre-order at: https://www.aospublishing.com/mia-burrus

Mia Burrus lives in the country north of Cobourg in a restored one-room schoolhouse, where she writes and creates collage/bricolage. She has published a poetry chapbook, What I Don’t Know, and several of her artworks were chosen for recent juried shows at local galleries. Visit her own gallery, www.miaburrus.com.

Felicity Sidnell-Reid is the co-host/producer of the radio series, Word on the Hills, on 89.7 FM. Alone: A Winter in the Woods was released by HBP in 2015. The Yellow Magnolia in 2021, followed by The Many Faces, Aeolus House, in 2022. Her short fiction and poems have been published in both print and online journals, and in anthologies.

Author: Anna Veprinska

Publisher: University of Calgary Press

ISBN 9781773856100 (hardcover)

ISBN 9781773856117 (softcover)

Number of pages: 99

Published Year: 2025

Reviewed by: Patrick Connors

You may have seen a wooden Matryoshka doll. It is actually a set, gradually decreasing in size, stacked inside each other.

In the poem “Matryoshka”, Veprinska depicts such a doll from her native Ukraine displayed in glass in a sitting room. She uses it as a metaphor to show that the narrator’s mother wants to become a grandmother.

The doll is also shown to be a figure of protection, of sharing the weight of life. We sense the strength of women, and know this is a theme of civilization. It is as simple as an artefact in a living room and as complex as a beautifully crafted poem.

Inherent to this nurturing strength is an underlying fierceness. “Each matryoshka grips/both broom and spear.//Each (fertile or not) is sliced with glory, with howl.”

Here Veprinska made a literary allusion to the great poem “The End and the Beginning” by Wislawa Szymborska. She has successfully adapted it to the current era.

Rather than let us believe our nation is exempt from terrible history, the author ends the first section of the book with “Shoes”.

This describes the discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous people found at a former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. The reader should recall how this inspired memorials across the country featuring the shoes of children.

The narrator compares this to piles of shoes viewable at the Auschwitz Museum. There is no pretty way to write about genocide.

Three times in the poem, including the final line, Veprinska repeats the same uncomfortable question about Canada: “How much of this country is an unmarked grave?”

In “Vowels for God –”, the reader will notice the end stop after the title. This foreshadows a number of Em dashes, and one more end stop, amongst the text. Most of the poems in Bonememory have very standard, even minimal punctuation, or else very experimental line forms. It is clear this piece is unique.

This poem is about prayer, the practice of asking for something and waiting for the desired outcome. It is communication with God while being present in the world and all that it contains.

Veprinska came up with this captivating personification of barriers to prayer and battles of spiritual warfare:

“...I became convinced an imperceptible bird (maybe a hawk?) had theived the night words from my mouth, tucked them into its plumage –a pickpocketing plea vessel – and winged away.”

The final stanza begins with the format change of prayers to handwritten notes, since birds cannot read. I consider my own early, often handwritten, drafts to be a plea to God, a confession of my lack of clarity, my prayer to be given the perfect words.

The poem ends with the ordering of vowels: “o, a, e, u, i, y.” Perhaps, like the birds, I am not meant to understand. But I am compelled to wonder, and I surrender to the mystery.

Anna Veprinska is the author of Empathy in Contemporary Poetry after Crisis. She was a finalist in the Ralph Gustafson Poetry Contest, has been shortlisted for the Austin Clarke Prize in Literary Excellence, and received an Honourable Mention from the Memory Studies Association First Book Award.

Patrick Connors is the author of The Other Life and The Long Defeat, both published by Mosaic Press. He was one of four poets featured in Bottom of the Wine Jar, published by SandCrab Books in 2017, and launched in the beautiful pearl of Gibara, Holguin Province, Cuba.

Author: Shyam Selvadurai

Publisher: Penguin

ISBN: 9780143462354

Number of Pages: 402

Published Year: 2023 (originally published in 2022)

Reviewed by: Shane Joseph The Review

The life of the Buddha, told mainly from the point of view of his wife Yasodhara, reveals him as human, fallible, and not such a nice guy.

Siddhartha is an unhappy royal (Prince Harry comes to mind), son of the rajah Suddhodana of Kapilavastu, constantly pondering the secrets of the human soul and disinterested in the trappings of royalty. He drifts from following the suicidal precepts of the Nigantha ascetics (fast until you die) to the Maharajah-turned-ascetic Maha Kosala’s Truth of Truths philosophy of moving from Atman (soul) to Brahman (God) via intermediate stops at the Mansions of the Moon (Limbo) and Land of the Father (Heaven). He finally lands on the concept of the Middle Way where nothing is permanent and everything is changing.

He marries his cousin, Yasodhara, falls out of favour with his father, and is posted on hardship assignments to remote corners of the republic, but always delivers stellar results, despite his boredom. They are childless for the first ten years of their marriage before a son, Rahula, is born. Grandpa Suddhodana is overjoyed because his nephew Mahanama is set to inherit the kingdom as Siddhartha is considered weak and interested in loftier ideals than meting out punishments to maintain rule by fear. Sidhartha, as the legends corroborate, finally escapes Kapilavastu to take up the life of a wandering samana (ascetic) and earns Yasodhara’s enduring disappointment for being betrayed.

The novel begins ten years later, when Yasodhara learns that Siddhartha, now a renowned holy man in the land and to whom many miracles have been attributed, will

be passing by Kapilavastu. It is at a time when Suddhodana is close to death, and his household of women, per the custom, will be turned out of the palace to return to their ancestral lands. The book constantly returns to the plight of women and their subjugation to men. Widowed or single women have only two options: become courtesans or bonded slaves.

Yasodhara and her mother-in-law strike out for a third option: become samanis (female ascetics) and join Siddhartha’s band of samanas, many of whom are the husbands or sons of the abandoned women. But herein lies the kicker: Siddhartha does not want them. His verdict is that “a samana path that includes women will soon wither and die.” He fears that the detached love the samanas practice will soon deteriorate into a possessive love if women re-enter their lives.

Despite many battles and palace intrigues that dot the story, the central conflict is how Yasodhara carves out a role for women to play in the ascetic life that dominates society in the republics of the Middle Country, now known as India. But it is a pyrrhic victory, for what they achieve is another lopsided role, with more rules for the women than for the men. You could say the women arrive at the Mansions of the Moon but need to work harder to reach Brahman.

Selvadurai has used extensive research and inserted Pali words (there is a glossary at the back) to paint a vivid picture of life in the times of the Buddha. This reconstruction of life, laws, customs, values, beliefs, and the evolving philosophy of Siddhartha are the most endearing features of the novel.

Shyam Selvadurai is a Sri Lankan-Canadian novelist who wrote Funny Boy (1994), which won the Books in Canada First Novel Award, and Cinnamon Gardens (1998). His YA novel, Swimming in the Monsoon Sea won the Lambda Literary Award in the Children’s and Youth Literature category in 2006. He lives in Toronto.

Shane Joseph is a Sri Lankan-born, Canadian novelist, blogger, reviewer, short story writer and publisher. He is the author of eight novels and three collections of short stories. His latest novel, Victoria Unveiled – in Search of Sentience, was released in September 2024. For details, visit his website at www.shanejoseph.com.

Author: Deborah M. Buehler

Publisher: Ridgecrest Books

ISBN: 978-1069129918

Number of Pages: 308

Published Year: 2025

Reviewed by Josée

Sigouin

The Review

In Tiaris, When the Oceans Kissed, Deborah M. Buehler deftly weaves historical fiction with a coming-ofage story, along with threads of fantasy in the form of time travel. Fourteen-year-old Tiaris has just started to fit in at school in Canada when her mother, a biology professor, receives funding to spend her research year in Panama. Despite Tiaris’s initial reluctance to follow her parents, she is granted greater freedom than at home and begins to enjoy her new environment.

A dug-out canoe excursion through a mangrove forest turns topsy-turvy. Tiaris finds herself flung a hundred years into the past. A seer in Panama City had previously warned her to stay away from the mangroves, prophesying that she would not be able to find her way home. Tiaris must now adapt to radically different circumstances. She not only witnesses history in the making— building the Panama Canal—but also lives through the political, sociological, and ecological upheaval caused by the mega-project. The ruling class treats manual workers like expendable labour, barely human. They foster a divideand-conquer atmosphere between groups of migrant labourers lest they unite to demand safer and more equitable working conditions. The commercial expediency of shipping faster across continents gobbles up large swaths of fragile ecosystems, concomitantly silencing the oral traditions passed across generations by the rainforest’s human stewards.

Tiaris is named after a small Central American bird, commonly known as the Yellow-faced Grassquit. Like her sociable namesake, she quickly makes friends with Gianni, a teen lured from Barbados by the prospect of paid work, and Carmen, a talented, young herbalist. Tiaris learns to clean, cook, care for a child, and “manage up” her demanding boss to earn a living until she can fulfill the requirements of a legend that promises to return her to her time. Tension ratchets up as an embittered foreman thwarts her plans at every turn.

The Isthmus of Panama has held geopolitical importance for as long as humans have inhabited the Americas. Building the Panama Canal, originally a French endeavour, led to the USA-assisted liberation of Panama from Colombian rule. The canal’s successful completion by the USA in 1914 yielded substantial savings in moving commercial and military vessels between the powerful nation’s coasts. A 1977 treaty ceded control of the Panama Canal Zone to the Panamanian government, becoming fully effective at the end of 1999. Twenty-five years later, more geopolitical tensions erupt when US President Donald Trump alleges that China holds too much power over the canal and threatens to regain control.

Buehler's luminous prose conveys Tiaris’s astonishment at discovering pristine Panamanian forest destroyed in building the canal. The story’s pace is propulsive. Will Tiaris find her way back, or will she remain forever trapped in another time and place?

Author bio

D. M. Buehler is an author, ecologist (Ph.D.), research analyst and teacher (B.Ed.). She weaves together extensive knowledge of biology and birds, careful research on the history of the Panama Canal, and a touch of fantasy to create a captivating story in her debut novel Tiaris: When the Oceans Kissed

Reviewer bio

Josée Sigouin is French Canadian and lives in Toronto/Tkaronto with her Chinese Canadian husband and two sons. Her debut novel, Our Fifth Season, where murder derails love, will be published by Blue Denim Press in October 2025. Josée also enjoys cycling, gardening, and welcoming birds to her tiny garden.

Poetry Editor: Bruce Kauffman

Photo Editor: Richard M. Grove

Bruce Kauffman lives in Kingston and is a poet and editor. His latest collection of poetry, an evening’s absence still waiting for moon, was published in 2019. He facilitates intuitive writing workshops, and hosts the monthly and the journey continues open mic reading series begun in 2009, and also produces & hosts the weekly spoken word radio show, finding a voice, on CFRC 101.9fm he began in 2010.

becoming as a day leaves it becomes neither shadow nor invisible but paints itself instead as the hue of every colour in a next coming day

centre in its very centre – at its heart but still emanating through is any particular thing’s essence each thing ever changing but original essence remains untouched and no different the acorn the oak

blue after Julia McCarthy’s “All the Names Between” blue comes to us to remind when another colour leaves or when we are looking away or when we believe we don’t dream in colour or in a ravaging world or day when all other colours are too much or not enough

Ana Johnson apj.ajohnson@gmail.com

Kingston, ON

Launching from the Kingston Yacht Club

Kayaking along Lake Ontario

Into the throat of the Cataraqui River

Among the elements

One paddle splash after another

Bass breath shimmering

On my torso twisting

Muscle spasms

One more, then another

Right, left, right

Some days at the wind’s wrists

Surfing the waves

Other days, flat

Flickering on quiet lucid

Emerald and blue

Diamond speckles

Mirrored clouds

And under the verdant Bascule Bridge

Hums and sways of shadowy vehicles

Echoing on the naked water

A far away splash moves in my ear

And I’m swallowed into a drafting call into the void Into the beginning And the end of time.

Alanna Veitch alanna.veitch.av@gmail.com

Kingston, Ontario

I’m told that I’m quiet, but inside my mind my voice echoes across chambers not yet, perhaps never, audible.

It’s as if I am yelling –across tables and spaces I thought were vacant enough to house my words.

So, what is it to be quiet? What is it to be loud? What is it to be these convictions bound by what our voices allow and what our bodies permit us to experience and escape?

And escape we surely have! Competing for airspace while I continuously fall towards near silence.

I’ve always lived within this category: quiet and stuck reaching, but not quite landing.

Sometimes, I have a promising beginning but any sound I produce soon trails as if I must be departing somewhere.

And I’m not terribly fond of leaving or of competing –of trying to snag a spot in the space above and between us, so

I’ve become terribly curious about what happens to the utterances that have left my body but stayed nestled close beside and quiet.

This is it to be bound by what my voice allows and what my body permits me to experience and escape.

Anna Panunto antod@sympatico.ca

Montreal, Quebec

Sugar maple, Black maple Red maple trees. Ah, the syrup of education! How tasty it was!

Let me concoct my own breakfast of knowledge with forgotten fruits and yellow birch.

The Madmen in suits re-inventing the supposed wheel. Perhaps, it stopped turning long ago.

The falsely learned…. by Master teachers of modern times. Haunted ghosts.

Leave them in the cemetery, they say!

Iron masks ripped apart Injustice, changing the needle of time.

Hold on to your weapons- boiled sap!

And know when to throw the buckets

For the long-horned beetle has already made its way…. Oh, those poor maple trees of yesterday!

Brian T. W. Way btwway@gmail.com

Rednersville, ON

sunny ways my friends sunny ways… have faith in your fellow citizens my friends they are kind and generous open-minded and optimistic and they know in their heart of hearts that a canadian is a canadian is a canadian —justin trudeau victory speech 2015

our sunny prince of shadows cast ever in the flair of that pater-star and yet first-past-the-post & gender woke legalized both dying and wacky smoke a senate by merit instead of cloak and child poverty diminished indigenous drums let sound climate and carbon arrested as that wuhan bug crept round but canceled by crystal blight toxic rumour and trumpet of doom as canadian and canadian and canadian marked down their gritty choice shadow hushed in the heart of noon

di Nardo Sutton, Quebec 01

Quebec 02

Bruce Cudmore cudmorebk@gmail.com

Rockport, ON

My Gardener

It starts with a dream of rows in thawed earth

loosened by tines, enriched and mixed in chanted prayers;

seeds counted and nestled into warm welcoming furrows and scrapes of dirt and gentle pats and trickled water and treasure sought;

provisions I can already taste, and I can feel your careful hands

working. All things tenderly imagined will come alive when they’re ready, and they’re never ready without you.

Christopher Black

January 16, 1950 - June 05, 2025

Campbellford. Ontario

Where is the grave of War, my friend? Does it lie upon a mountain high, or in a desert vast, Or down below a troubled sea, seething with the past, Oh, can you tell me, quickly, and there me quickly send, For then I’ll know it’s over now and Peace again descend.

They say it is a monster, a nightmare roused awake, Ready deep within us, ugly, deadly, dark, To spread chaos universal and snuff life’s feeble spark, That feeds on sorrow, hatred, heartache, And drinks deep to quell its hunger from a blood-filled lake.

And if no grave exists where rots its stinking head, Then surely we must slay it, rid the world of pain and death, But what’s been done to do it, or do I waste my breath, On a quest that’s more than urgent, one I cannot shed, But nor you nor they me answer, just weep for all dead.

Editor’s Note: I was in the communication process with Chris after accepting his poem in mid-June. In mid-July, his life companion, Gail, discovered the thread of emails and contacted me with the news that he had passed. Again, here, my condolences to her, his family, and friends.

I did ask if she would think it was appropriate to still publish the poem I’d already accepted from him. She said, ‘Yes’.

I also asked if I could include the link to the very touching funeral notice that described him & his life for anyone interested. And Gail agreed. Here it is: https://www.cardinalfuneralhomes.com/obituaries/mr-christopher-charles-black/ Bruce

David Malone maldc4@hotmail.com

Kingston, Ontario

The Cormorant

Black as a crow, you often hear, or a raven, but the sleeker cormorant is also black.

Low over the unusually still surface of the water he came, and I on my back just as still on it.

So still you could hear it embrace the first heat of the sun, toward which he flew.

I was thinking of being older – sixty now –and of how I’d known, really known, so few people in life.

(When my brother turned sixty at least that many attended the gathering.)

He mustn’t have seen me till he was right upon me, a slight turning as I turned my head.

Just the tip of a wing, that’s all (a slight mark on my brow, that’s all); though startled, he kept on towards the sun.

Awkward fliers, I’ve always thought, but superb divers (as water birds rather made for that);

and the distance, searching and searching –as I have searched and searched –they can swim beneath!

Still and black as sun-splashed glass, whereas the day before when I’d swum, with the winds hard from the south, swells of six feet tipped white.

So what had scored me the day before were like the roarings, it felt, of the primordial deep.

For all that, still the touch of the bird’s wing was the more hurtful thing.

Codrina Ibanescu

codrina.ibanescu@gmail.com

Etobicoke, Ontario

Leave your regrets For the grave

For tomorrow rays burn

As brightly as your Hearts desire And fortune favours the brave

Do not wallow in malaise

Put each foot in front of the other

And mark your path with grace For tomorrow doesn’t bother itself

With thoughts of yesterdays

One blink of an eye And yesterday is gone

Leaving no room for sorrow

No stones left unturned

Can be turned again, tomorrow

Breathe and learn to follow

The carvings left behind

Ease your heart and soul –For today is the horizon

Of a new state of mind

Dinh Le Doan dledoan67@gmail.com

Beaconsfield, Québec

From their lofty heights, the stars have been gazing down at us for hundreds of thousands of years. And they do not stop gazing, for they’re still amazed by what they find, at what we become: Our star-like brilliance that animates as it shines. Perhaps our vast distances to the stars are only short arm lengths

on their scales. And our immense millennium is less than a blink

of their eyes. We are thus in the stars’ laps or cuddling gazes still. And yet we have begun

to cry out questions on our origin. Where did we come from? How did we get here?

To the furthest stars and beyond them we have been gazing back, hungry for answers.

DVE McBride

dayle.mcbride@sympatico.ca

Amherstview, Ontario

Privation

Overhead contentious winds guide spirit and cloud Words rustle between the trees

They know this story too well Across the road survey stakes pierce tender soil

Hectares sectioned off to be land –reinvented Yet another subdivision with chain-link fences in every shade of metal; vegetation removed to make room for newer vegetation Easier if we pretend the stand of pines was never there

Elizabeth Hill elizzhill@gmail.com

Toronto,

Ontario

I sweep your hairs from the stairs, and pick them from my tea, but your hairs in my heart will always be with me.

Eva Kolacz

eva.kolacz@gmail.com

Victoria, BC

Stepping into the Immortal Forest for my mother

I’m still in possession of the room you lived in.

On the table stands the jar with forget-me-not flowers, in the corner easel with your unfinished painting, the brushes and paints suddenly abandoned, still there.

Recently

I stretched the walls of the room, you know how they shrink over time, first losing colours, then, all the juices keeping them alive.

And I stripped the skin of the walls from shadows which easily can turn into black holes fit so well for backstage dramas.

That day of early autumn was not different from other days of early autumn except for the maple tree shading leaves on the sidewalk.

And for a moment I existed in a spinning carousel of golden smoke and mist.

I picked up one leaf and placed it in your hand when you were just about to step into the immortal forest of silence.

Toronto, Ontario

Gordon Gilhuly ggilhuly@rogers.com

Woodstock, New Brunswick

last touch

this last touch of winter, like a travelling salesman, unpacking all its laces and white cloths, spreading them everywhere, giving the maidenly trees long gowns of trailing white:

a sudden slant of yellow, early spring wildflowers, flung across the thwarted winding sheets of snow

whispered gossip of a little stream the sky ripped open by scars of blue across the tract of clouds

Keith Inman inman@vaxxine.com

Thorold, Ontario

the sun stretches across clay tiles

to wake the yellow wall like a burst of pollen

above the glass table with its page-marked book

and half-filled cup of coffee gone cold

while the jade in the corner bides time

Katerina Vaughan Fretwell

kfretwell@cogeco.ca

St.

Catharines, Ontario

In grade 11’s Yeats and Eliot feast, I raged, “It’s all about death and war!” The teacher kicked me out for that class.

In the hall, The Second Coming –gaze blank and pitiless as the sun and The Hollow Men –This is the way the world ends Not with a bang but a whimper –

Caught in a maelstrom at those words, I was already mourning my family fatally swamped by booze and smokes. The lines gripped me like the choke-hold swimmer’s carry.

Only the feisty lifeline from Dylan Thomas tossed me a fight: Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

English class soon over, the preppies sauntered out, followed by prim Miss Luchterhand.

Unaware how heart-chosen words capsized me, they could not fathom that my truculent protest

proved that poems whirled inside me –decidedly not “Ho-hum, shall I wear paisley or silk shantung for Saturday’s date?”

“The Waste Land” echoed the preppies: What shall I do now? What shall I do?...

Pressing lidless eyes and waiting ...

Kathy Robertson kathyrobertson0234@gmail.com

Kitchener, Ontario

It’s been a year since you soared above a starry night into the arms of the universe;

since we made love like it was your last day on earth because it was;

since attendants carried you from our home on a quilt-cradled stretcher to an awaiting hearse;

since I went to bed alone wrapped in your pajamas;

since you promised to return as a cardinal and, oh, you did! You did!

Now it’s Spring your irises emerge through the awakening earth like butterflies shedding their shells because it’s been a year.

K.V. Skene kv.skene@gmail.com

Toronto ON

From the far edges of the galaxy’s curve

we cup eternity travel from the beginning of time to the end of everything we love circle the world’s edges claim them for ourselves like a god plays with gravity stretching the infinitesimal to the universal and still be still believe if only for a nanosecond in every wild and wordless thing that ever was and is and breathed in the chaos still determined to dig deeper and deeper

build higher and higher locate the genesis of our accelerating dismay and follow its snarled strands back from their knotted beginnings to their fraying ends

high overhead and still tethered to our mothership what we think we dread is not will never be some rough beast with a terrible hunger but our slouching selves still sound asleep beneath a strawberry moon

Honey Novick

creativevocalizationstudio@hotmail.com

Toronto, Ontario

Chloe Cooley is her name

Chloe Cooley’s significance unnoticed by fame

But

Chloe Cooley made history, her story

Her story changed the laws of Canadian slavery

Because of Chloe Cooley, Canadian slavery came to an end

Her story was something no one could portend

Sold like chattel and property without a quiver

She was sold across the Niagara River

Fortunately witnessed and then reported

By Peter Martin, a Black Loyalist

This was a story he couldn’t resist, told

To Lt. Gov. John Graves Simcoe

Of the sale of this human cargo

So…

To pass the Act

No turning back

Time to pass the “Act to Limit Slavery”

Upper Canada, in 1793

The act was passed within a year

Stoking the flames of some people’s fear

Setting up legislature on this land

The first and ONLY act the British Colonies had at hand

This limited slavery

Done with patience, fortitude and a lot of bravery

Until full abolition was passed in 1834

Truly a human condition that only some people abhor

Yet, this was a victory galore

Back to Chloe Cooley….fearless, peerless, It’s time to honor her with gratitude and fame

We’ve learned a little of what encompasses this name

Chloe Cooley

It is our duty to say her name…….

John B. Lee johnb.leejbl@gmail.com

Port Dover, Ontario

a little plaster bust of Goethe occupies a place of honour on my desk though with every movement of my writing hand with every shiver of my arm he topples like a dreidel slowing to a stop he tumbles into one of Dante and they tremble as they fall like kings surrendered in a game of chess, to me each clack resounding it seems as though I were a vandal tipping tombstones in a yard of graves where poets lie in grassy silence made from a model of the world of words a miniature where every sentient breath is pushing smoke

I purchased the one in a tourist shop in Florence the other at a museum in a house in Munich where Goethe lived and they seem to watch me while I write though they are both of them blinded by time like memories that are mine alone or dreams I’ve dreamed without recall

I have their books closed up upon a shelf like rooms in darkness, occupied I hear a door ajar a silent footfall on a vacant floor an empty rumour of the presence of a quiet voice where Virgil’s hand is reaching through the empty air like candle snuff a withering and redolent inquiring of light no longer there

Mia Burrus miaburrus@gmail.com

Baltimore, Ontario

By the time the Canadian Pacific Railroad was completed in 1885, only 23 homesteads had been claimed along the 400 miles from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan to Calgary, Alberta. Captain John Palliser, a British government surveyor, had surveyed the area in 1859 and deemed much of the area a semi-desert, unfit for agriculture.

But at the turn of the century, it flashed its green riches for a few wet years, blinding all who saw it to its true nature, and the prairie filled with new immigrants. Then it dwindled back to its usual dry dullness. By the 1930s many homesteaders had walked away their farms.

excerpt from As If Through a Window, AoS Publishing, 2025

sovereignty was our made-up tale hammered bronzed burnished over a few short centuries hardened into coin du realm hollow at its core

freedom was the emptied plain the unbroken wind-whispering sea of grass (Palliser’s Triangle – the palest yellow on the map) soon enough railroaded and fenced soon enough fetters and false hope

Rebecca Clifford becca.clifford@gmail.com

Caledonia, Ontario

Dry summers of unrelenting sunshine, the permanent press of a clean blue sky,

a late luncheon of ripe cheese, fresh loaves, crusty from the oven, olives brined or not. And wine, wine about 3 weeks borne, in any old bottle Marcello could lay

his hands on. Wine with no personal pedigree, more a sassy grape juice with attitude that knew someone important or had a rich uncle in local government or at the butcher shop.

Then, that sweet accordion playing nothing in particular, lolling through the evening’s

cool of the cafés, spilling onto the blue cobblestones. The wine always takes me

to the evening respite but I’m pulled there only after the red poppies, nodding in the oil and linseed breeze, and the round gloss of sonic-scented yellow lemons first catch

my attention.

In response to William Blair Bruce’s Landscape with Poppies, 1887 oil on canvas, Art Gallery of Ontario.

Robert Currie currie.robertdm@gmail.com

Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan

Too tired to read any longer, I watch the dragonfly circle, hover, and land on my thumb, its wings shining like coins fresh from the mint. A narrow, purple cord with eyes, it remains there while I slowly drop my hand to rest on my knee, the dragonfly as still as the stone that gleams at the water’s edge.

Here on the shore of the lake we reside—the dragonfly and I— at ease in the kingdom of August, hours sliding to dusk, days growing shorter, summer falling away, both of us content to remain a while in sunlight and shadow as clouds drift by. I feel now that I know what it means to be touched by the hand of God.

Teresa Hall thallartist@gmail.com

Scarborough, Ontario

Along the dry riverbed they trotted with their heads held down, dust swirling in their hoofprints upon hot cracked ground. Their manes caked with dirt and lifeless, strength nearly gone yet still they came across the plain steadfastly moving on; as generations had gone before, now nearly the last of a dying breed, almost a part of folklore. Ingrained in the land and the land in them. Could they make it to the end? The stallion called softly then led them to the fell; their destination reached, drank deeply from the well.

Steve Noyes snoyes@vanisle.net

Victoria, British Columbia

He had been gone for years when I entered the log cabin with a peaked roof, at the edge of his widow’s property. No power inside, so I had to creak the double doors open. With an inhibition akin to breaching an Egyptian tomb, I braced for chaos. My eyes adjusted. Syrupy firewood smell. At the roofline, among infiltrating blackberry vines, a snaking phone-line which he cut in one of his foul furies because he no longer wanted to be reached, or because he was absolutely convinced that the same guy who prowled inside his computer was inside the phone.

He would lose track of time, fiddling and fixing trimming and shimming, and she’d call down saying Supper’s on. Perhaps. I wouldn’t want to make things up. There’s a leaning heap of long-handled tools, hoes, shovels, rusted secateurs now only good as a kind of tongs, and blunt axes, their blades jammed onto too-narrow hafts —a bloody wonder he didn’t kill someone. He sharpened them with an antique rasp. Five skill-saws. Most folks just have one. A grease-gun, a word I’d only seen in print before, now reified. Innumerable paint-cans whose contents had solidified.

I hefted his limp slingshot, and with a grim smile thought of the aging, addled boy who sighted the power-pole and let fly, trying to take the hydro-workers down. All projects stopped, he came to the cabin to be alone, to sit on the grubby Styrofoam cooler, watch the sun shoot rays through the roof-chinks and make bright patches on the cement floor. I thought I might find him here, but I got lost in this inventory. Time to sort out all this machinery and these tools into lots, bang the dust off, display them on tarpaulins on the lawn before the early bargain-hunters come.

Susan Smith essaysmith69@gmail.com

St. Catharines, Ontario

The storm is still roaring. Waves three times my height beat the beach, churning the colour of sour cocoa.

Another three hours to go to high tide so I don’t dare predict — could be bluster or could scrape the whole building to the sea, tottering, bobbing, dropping chunks of itself all the way to Mexico.

I am making bread while I wait.

I’ve never known what the world needs of me but hunger is a rare gift of certainty —

as is knowing I could spend the whole day with neighbours picking rocks and rotted coconuts from the parking lots — what the old ones do when a baffling tantrum has passed.

When we’ve collected the rocks together we will lay one on another, new beachside limit of our hopeless fiefdom.

We will bring out of sanctuary beach chairs hidden in stairwells.

We will set wind and water our enduring challenge: Swipe away our concrete slabs our salt-pocked windows, ruined gardens.

Pitch us in the bin of what’s forgotten.

We pick rocks. We break bread.

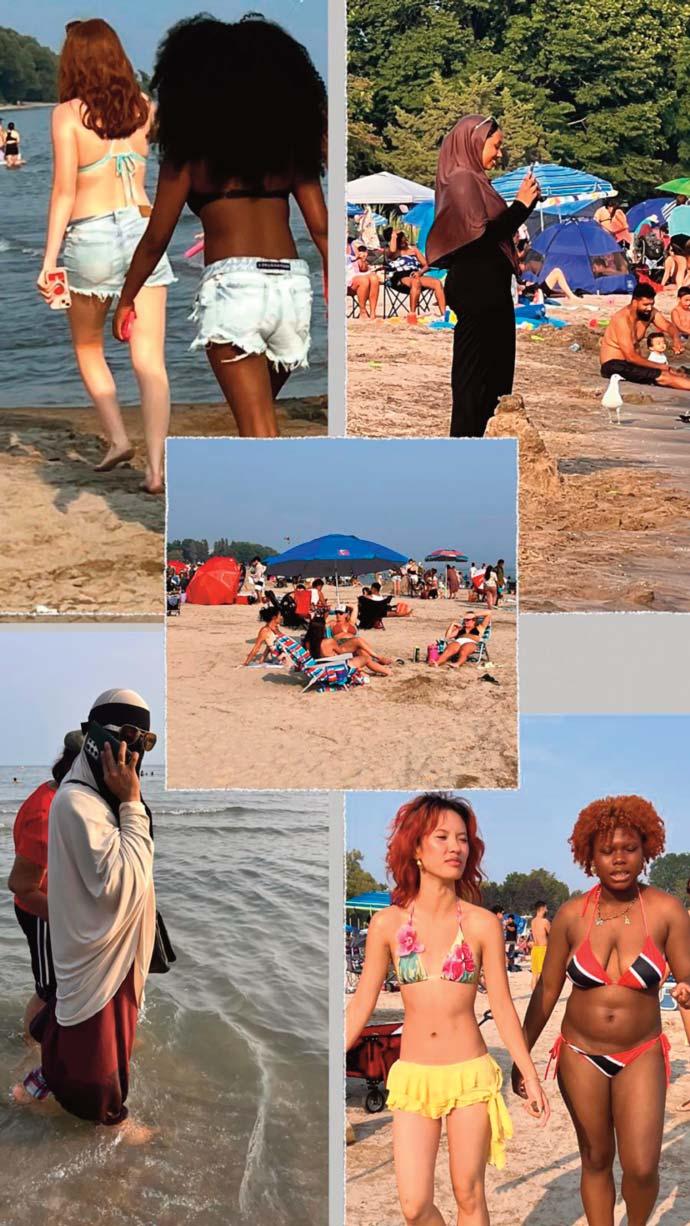

Richard M. Grove

RichardGroveTai@gmail.com

Brighton Ontario

August 7th – Presqu’ile

The weatherman calls for 32°C today, there’s no rain in sight.

I’m walking a familiar path through the woods, it feels like the forest is holding its breath, less like the middle of summer, the beginning of an ending. The air is heavy.

Except for the deep rooted trees everything droops with fatigue. Brown tipped leaves charter along the path, grasses, wildflowers, and ferns bow low, gasping, pilgrims nearing the end of a long journey. No birds sing in this dry heat.

No squirrels scamper.

A passing dog pants heavily, seeking shade from a sun that offers no respite.

Yanlan Yu elaine.yu@lifetech.com

Toronto, Ontario

The Tulip blades like fresh jade, breaking through the rock.

Soon they’ll wear gold, violet, pearl-white so ancient, and serene.

I love them as much as Rilke’s roses so deep, and luminous.

Yet you’ll never know how they think of you in verses layer upon layer.

“A leaf is in the puddle over there…”

They murmur sometimes, in self-surround cosmos exhaling fleeting sorrow from a dream a sigh of fragrance.

Anna Di Nardo

Artist / Musician / Songwriter

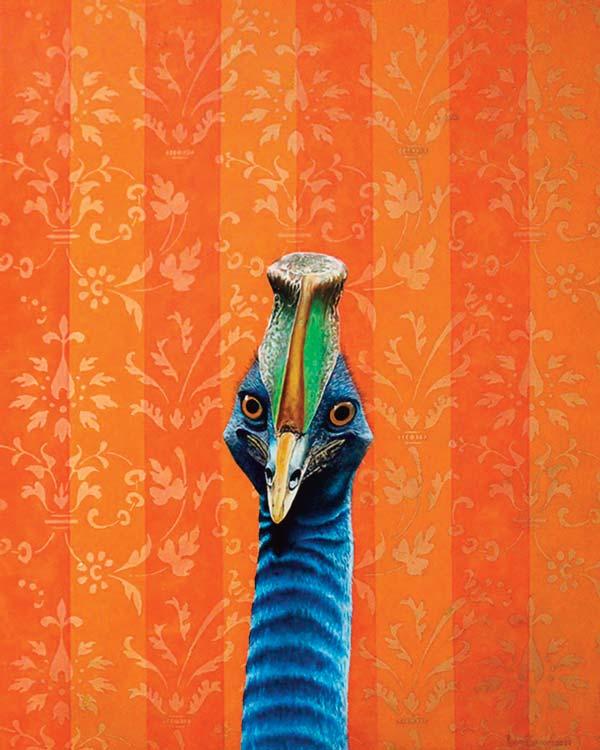

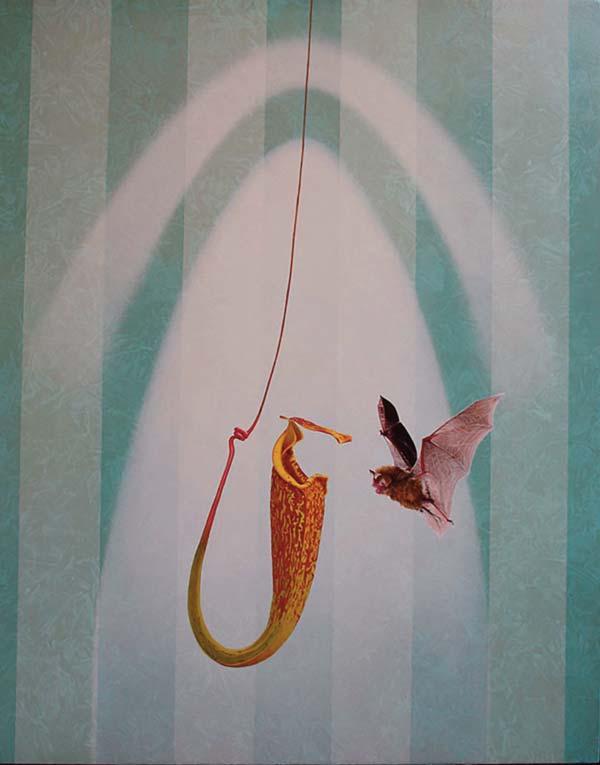

Bob Tunnoch, born in 1953 in Ottawa, is known to friends as Omar—or, in his own playful email sign-off, “Omartian, Rebel without a Planet.” He is not just a stunning Canadian-born surrealist painter but also a blues musician. A two-time Juno Award–winning songwriter and founder of the band Fathead, his music career is well documented elsewhere. You can look it up on Wiki later; they have the full story.

For me, I am interested in Bob Tunnoch the artist. Let’s get the pedestrian details out of the way first: he has been a member of the Society of Canadian Artists and the Colour and Form Society, and he is currently a member of the Ontario Society of Artists. He was a featured artist in the International Contemporary Artist publication (2013) and Arabella magazine’s 2021 issue as an “Artist to Collect.” He has won many awards, including the First Award of Excellence, Best in Show, at the Society of Artists International juried show.

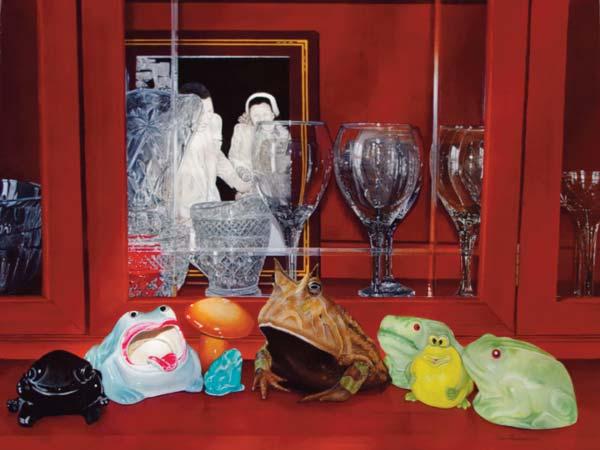

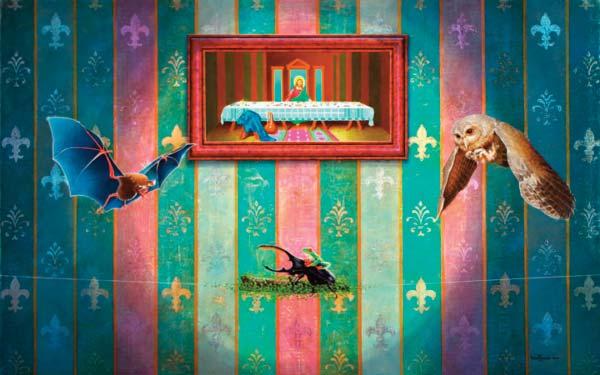

He might at first appear to be a kind and calm farmer, but lurking behind his rural persona you would never guess he had the intellect and wit of a philosopher, quietly conjuring paintings with a complex understanding of life’s sometimes perilous juxtapositions. His unassuming demeanour suggests a life rooted in the mundane rhythms of country living, but behind that presence lies the mind of a true surrealist painter, following in the historic footsteps of Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) and René Magritte (1889–1967). His mind sparks with a thinking process as unpredictable as one of his dreamlike canvases. His use of vibrant colours, attention to detail, and surrealist subject matter leaves viewers stunned by juxtapositions that flirt with life and death. As you will witness in his paintings, he draws ingenious inspiration from the natural world. His superrealistic style is filled with meticulous detail and thought-provoking combinations of images.

Through works like “Sushi Roulette,” Tunnoch explores social commentary by presenting a blindfolded man, smiling from ear to ear, as he prepares to eat from bowls containing a flamboyant cuttlefish, a blue-ringed octopus, and a pufferfish. Each is beautiful in its own way, but each is lethally poisonous. Unlike Russian roulette, there is no blank chamber—every choice ensures a catastrophic result. With biting irony, Tunnoch satirizes humanity’s reckless consumer appetite and willful blindness, turning irresistible consumption into a fatal gamble with only one outcome. This work reminds us that consumerism, however alluring, can have perilous results if our indulgence is not exercised with care.

In a former life, decades ago, I was a corporate art consultant and would not have hesitated to advise any collector to add Tunnoch to their collection.

Thank you, Bob “Omar” Tunnoch, for brightening our world with your thought-provoking paintings.

You can find Omar at: www.bobomartunnoch.com

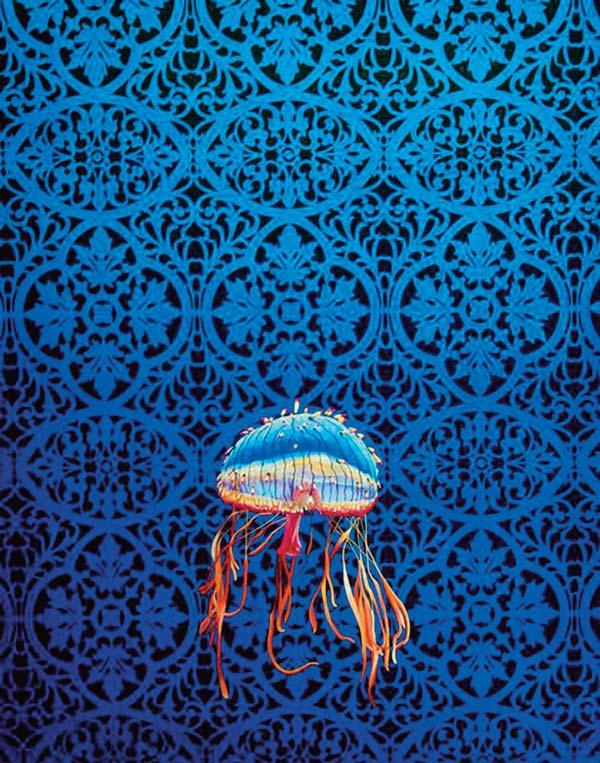

In Session, Carnivorous Plant Choir

The Last Supper, Conflict of Interest

Prof. Miguel Ángel Olivé Iglesias. MSc

Author, Poet, Writer, Editor, Translator, Lit Essayist

General VP of the Canada Caribbean Literary Alliance

“I am grateful to have had the opportunity to write the poems that visit my desk and flow through my pen. I am simply a vessel, and I am thankful when the muses visit…” John B. Lee

How do I synthesise Canadian Poet Laureate John B. Lee’s oeuvre in a few pages? Lee’s writing gift has made him a recipient of as many awards as humanly possible. He has tirelessly crafted piece after piece in his long, prolific career. He has written nearly about everything with unique perspective and penmanship.

I have written some seven reviews about John B. Lee as a poet and as an editor too. I might write seven more in the years to come. What keeps me coming back to his work is his genius to take words and tame them and make them his own, almost as if he reinvented them, and then gently eased them onto the pages in tender, flowing sentences that mesmerize readers and reviewers like me. Whether the themes are the world

around him, his travels, family, friends, visits, sex and so on, we will always have the sentient writer (the man who is not a poet, just someone who writes poems, according to him) in constant exploring and strumming of the silence that he well knows “is the light the poem shadows from.” (from a poem by Lee)

His incursion in LitLand has left for us a fully detailed map of fine books with great poems for us to read, take in and become a part of their charm, one that appeals to us once we are caught up in their mystique. A note of advice: read twice; read three times if you have to but then you will be lit by that creatively red-hot furnace of words harmonically, essentially shaped into pieces we will not forget.

Roger Bell’s Foreword to John B. Lee’s formidable book This is How We See the World (Hidden Brook Press, 2017) illustrates further into the poet: “Wherever John Lee takes us… be it China, Thailand, Korea, Baffin Island… or the shores of our great lakes, readers will be aware of the archetype of his journey. Yes, the physical voyage has weight, but it is really the interior journey, the progress of the soul, that counts. While he so fluently details the world around him, Lee is more deeply in search of the ch´i, the vital force… something just beyond the circle of light.”

In my book When the Muses Visit: My Twenty Favourite John B. Lee Poems. An Annotated Selection (Wet Ink Books, 2024), I dared list poems I considered landmarks in my modest view. Poems such as How Beautiful We Are, I Wake to Breathe Your Beauty In, Kissing the Darkness when the Pages Close, I Too Can Show the Way, One Leaf in the Breath of the World, The Place Where Poets Pause, An Afterness, Taken, The Sad Mathematics of Our Lives and So, this is a place of places, reveal Lee’s rich, insightful poetic tessitura to enter realms from where he brings back the magic of letters. In doing so, he becomes

a magician of a higher order, a moulder and giver of meanings we never thought of, yet he unravels both worlds and meanings for us. The above titles alone—and a myriad of others—tell us of his broad thematic spectrum, as he covers love, poetry itself, a philosophical optic of things, his travelling recollections, fatherhood (read his section in Fathers & Sons by Richard (Tai) Grove, Don Gutteridge and John B. Lee. Black Moss Press, 2022), etc.

Precisely about his poems in the book I said: “I had the chance to read about John B. Lee’s feelings as a father. I remember his comments on the poem “The Sad Mathematics of our Lives” and what he said about his beloved son, “… my own experience as a young father carrying the precious bundle of my son in my arms, fallen asleep in the car, carried from car to house to be deposited in the cottage bed ... these images return to me... The sounds of the night, the shelter of my own loving arms cradling my child, the passage of time which cannot be held back…”

His impact rolls way beyond my humble favouritism. In my book In a Fragile Moment (Hidden Brook Press, 2020), I stated, “Lee keeps the language very much alive and holds it in his genius poet hands to pour out excellent products…” in reference to his poem Bread, Water, Love (John B. Lee’s chapter “Bread, Water, Love” from These Are the Words by George Elliott Clarke and John B. Lee (Hidden Brook Press, 2018).

Another of his many books, Into a Land of Strangers (Mosaic Press, 2019), sings to family roots, life, sacrifice and honor. Lee takes words, touches them and – like King Midas turning things into gold – waxes them into indelible witnesses, and erects them as mementoes of events and lives past. Bernice Lever reminds us that “John B. Lee’s lines flow smoothly from one fresh metaphor to the next.” and Roger Bell says about him: “I encountered a writer of greater scope, and poetry even more profound and wide-ranging, than I

was accustomed to… John Lee’s wide and deep observations of this wondrous life… the gravitas he brings to his visions of this world.”

This is a digest of Lee’s work. Nonetheless, it would be incomplete without a brief approach to one of his latest books, Do Songbirds Know Where They’re Singing. Every book carries in its bosom—a word so aptly meaning “source of thoughts and emotions”—the experience, feelings, anecdotes and creative touch of the author. Do Songbirds Know Where They’re Singing, a 2025 Wet Ink Books fresh publication, is filled from cover to cover with a deep, strong, affecting, reverential aura only a few chosen can condense so intensely and pass on to the reader so effectively despite years elapsed. John B. Lee is one such poet. This is a book of poems memorialising the sequels of a war that devastated the human race and stole the lives of numberless soldiers, Canadians included.

John B. Lee is not only a poet. He is an essayist, lecturer, professor, editor, thinker and humble human being. Regarding my review about his Into a Land of Strangers, a surprising anecdote made my day and led to the review. John B. Lee emailed me to ask if I was willing to write a review about a book he was about to publish. He said “I am wondering if you might be willing to review this book. If not, if you’re too busy, don’t worry about it at all.” A great poet asking a friend, so politely, so humbly, if I might be willing! Greatness and unpretentiousness in one man! Lee is every inch a modest man too despite his triumphant parade across LitLand.

The above example is proof of his modesty, and what we read in the lines and between the lines of Do Songbirds Know Where They’re Singing is evidence of his intention with the book and his profound sentience: “… a collection of homage to people he knew (his father-in-law, his Uncle) and closely related to, which adds a personal urge that will appeal to many, and to people, mostly and sadly young boys, who fought in the war and lost their lives. The poet’s sensitivity was aroused instantly by the atmosphere surrounding [a] gravesite he visited.” (Taken from my essay “Bird Songs of Tribute: I Remember… A Review on Do Songbirds Know Where They’re Singing by John B. Lee. Wet Ink Books. 2025).

Lee’s comments about life and writing, to mention two areas, leave significant material behind to ponder and reexamine the very nature of our world and lives. Existence and its labyrinths are a core vein in the poet’s construal of reality, a vein which he masterfully populates with poetry. About these motifs, Lee said, “I want, in poems… the spirit to surround and be surrounded by an interplay between the deep wells of the self and the stars beyond the farthest stars we might dream…” (Taken from John B. Lee’s essay “Even at the Worst of Times” in And Left a Place to Stand On, Hidden Brook Press, 2009).

Lee is a milestone in the rich mosaic of Canadian poetry, literature, culture, broadly viewed as human input and shaping of a heritage that is handed over from the past to us and will outlive this generation, next generations. Lee’s contribution and adherence to the long-standing tradition of celebrating nature – awesome, edifying, unavoidably present, whether we see it or not, whether we want to see it or not, is transcendental. No better remark to close my review than George Whipple’s calling John B. Lee “The greatest living poet in English.”

Thank you, John, for my few pages striving to enclose your huge contribution to CanLit.

by James Deahl

Published

by Aeolus House

Review essay by Richard M. Grove (Tai)

James Deahl’s Four-Square Poems is quite a remarkable poetry collection, a republishing of four previously smaller books that bridges history, nature, and the complexities of human emotions. Each section of the book comprises long, interconnected poems that weave personal experiences, cultural heritage, and philosophical musings into a cohesive narrative. This analysis explores the four primary sections: In the Lost Horn’s Call, No Star Is Lost, North of Belleville, and last but not least, North Point and will hopefully bring the reader into a greater understanding of the CanLit voice of James Deahl.

Let me start by commenting on what I think is the significance of the dedication that James placed at the start of the book:

Although each of the four poems that comprise this volume is dedicated to a specific person, I would like to take the liberty of honouring my three wives:

Shirley Deahl

Gilda L. Mekler

Norma West Linder

May they have found peace and comfort in Heaven.

The dedication is deeply personal and I feel it serves as an emotional and philosophical framework for the entire collection. By honouring his three late wives; Shirley Deahl, Gilda L. Mekler, and Norma West Linder, James places the book as both a literary endeavor and a deeply reflective tribute to the most intimate three relationships of his life. The significance of this dedication can be analyzed through several lenses. It seems to me that James’ dedication is a profound acknowledgment of the central role these women played in his life and creative journey. By including them collectively in the dedication, he elevates the importance of their presence and influence on his life. The phrasing, “May they have found peace and comfort in Heaven,” reflects his grief and longing not just his hope for their eternal rest. This sentiment resonates throughout all four collections represented in the book. For example, in No Star Is Lost, the James reflects on eternal connections, saying, “Not so much grief, / but a recognition of limitation.” His acknowledgment of limitation mirrors the human struggle to accept loss while cherishing the enduring impact of love.

In No Star Is Lost, the love Deahl shares with Gilda Mekler is explored through lines like, “pure love endures forever,” emphasizing how love transcends physical existence. Similarly, in North Point, the wilderness he loves and the relationships he honours converge in metaphors like “a man lost in time” among trees shaped by the elements.

By dedicating the book to his three wives, Deahl invites readers to consider the complexities of relationships across time. The mention of all three women together suggests not just romantic love, but also a broader exploration of partnership, influence, and shared life experiences. This layered view of relationships is a recurring theme in In the Lost Horn’s Call, for instance, the poet reflects on misunderstandings and struggles, writing, “Ah, woman, slipping into nebula, you are bone,” an acknowledgment of both the ephemeral and the eternal nature of human connections.

Let me finish by saying that the dedication, therefore, might be thought of as a reminder of the imperfections and strengths in love, an undercurrent that enriches the emotional weight of the entire book. I hope it is not too much to conclude that the dedication is more than a ceremonial gesture but it is an emotional and philosophical cornerstone for the collection.

In the Lost Horn’s Call is the first section. It serves as a poignant opening to James’ book, reflecting on the social turbulence of the 1970s and the personal anguish that marked the poet’s own life during this period. Written during a time of gendered discord and societal uncertainty, Deahl’s imagery often oscillates between chaos and tranquility.

The opening lines:

The clarity of snow is cut by the thin edge of the land,

evoke stark imagery that mirrors the raw emotional landscapes explored in the section. The juxtaposition of nature’s beauty with human discord is a recurring motif, as seen in the poem “Toronto, 1976”, where the city is transformed into a “cosmology,” emphasizing humanity’s struggle to find harmony within urbanization.

From the poem entitled “One” James demonstrates his mastery of portraying the simplest perceptions in such a poetic way that one has to stop and be there. Many observers may have simply overlooked a leaf in motion.

imperceptible motions of leaf to sky to water

The finite resettling of light to lake proceeds downward along crevices of still air

In the distance the work of rock and time is a fragile passion

A few ducks rise among foamings at the ferry docks

In the poem entitled “Three” a particularly evocative moment is the observation of human relationships, captured in lines like:

She is Liberty striding over the dead.

James merges the personal and political, invoking historical figures like Delacroix’s Liberty while grounding the imagery in intimate, tactile moments.

The section No Star is Lost is dedicated to the late Gilda Mekler, his second wife. This section reflects on themes of love, loss, and memory, traversing landscapes both physical and metaphorical. The prologue introduces a contemplative tone reminding the reader that time is finite but anchored by the mystery of eternity. This philosophical perspective frames much of the narrative in No Star Is Lost

The section traverses specific geographies, such as the Appalachian Mountains and the coal-mining communities of West Virginia, where Deahl’s ancestral roots lie. In “Hiorra”, the poet explores the impermanence of human existence, using vivid imagery like:

bare trees showing the fallen house, to emphasize the passage of time and the erasure of once-vital lives.

Deahl’s treatment of the natural world is both reverent and even sorrowful. He acknowledges the harshness of nature, yet celebrates its resilience and capacity for renewal. The section’s title suggests an optimism rooted in the belief that nothing, whether a star or a memory, is ever truly lost.

Deahl is known for his long poems. “Camp Chapel” is a four page poem that blends nature, memory, and mortality into a meditation on time’s passage, where sorrow yields to beauty and remembrance.

But no star is lost, not even here where time and rain mark our losses.

Here is a perfect stanza to illustrate how Deahl deals with sorrow, beauty and remembrance:

Not so much a sadness, but a longing for forfeited innocence comes with the rain to these brown woods, comes in the quiet between rain drops. Not so much guilt, but regret, touches the heart like an unattainable lover or the hand of a childhood friend not seen for fifty years.

This section is a departure in form and tone, composed largely of haiku that capture the transient beauty of Canadian landscapes. Dedicated to Deahl’s grandson Felix Girard, the section reflects generational continuity and the cyclical nature of life.

Deahl’s haiku are steeped in imagery that celebrates the stark beauty of the Canadian Shield. For example:

Smoke from a highrise straight into frozen air— fields of bitter weeds.

This poem juxtaposes urban and rural settings, creating a dialogue between human encroachment and the timeless natural world.

The haiku’s brevity belies their depth, with each poem functioning as a meditation on existence, temporality, and the relationship between humanity and nature. The final haiku in this sequence:

Mississippi River frozen bank to bank— Orion strides across.

This simple haiku underscores the poet’s fascination with cosmic forces that mirror the vastness of the natural world.

Let me finish this section by quoting this haiku, in my mind the best of the batch. I have been there and heard that and felt it to the deep core.

Crack of noon cannon echoed by the bells of Pointe-Gatineau across grey water.

This section is dedicated to Norma West Linder whom I had the pleasure of meeting many times and published two of her books. The section pays homage to the Canadian wilderness and its symbolic resonance in shaping national identity. Inspired by Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven, Deahl uses vivid imagery to explore themes of resilience, transformation, and the search for a deeper understanding of self and country.

In “The Jack Pine”, Deahl draws on the iconic image of the lone pine shaped by wind and storm. The poem presents the jack pine as emblem and survivor, embodying resilience, stark beauty, and spiritual pilgrimage. Here are a few line:

Always a renegade pine shaped to wind and storm. This, then, is our station, our emblem and point of pilgrimage.

The jack pine, fireborn years ago when lightning flashed a forest into ash, waits at the border of water and stone —

Similarly, in “Burnt Country, Evening”, Deahl captures the regenerative power of nature, observing that:

Infernos burn, and as luck would have it, a painter records, and life returns without his help. Creation’s wild song echoes down the billions of years since that first fiery act of love.

This section’s centerpiece is “Algonquin Park”, a richly descriptive poem that likens the forest to a cathedral where “October’s flames soar.” Here, Deahl seamlessly blends sensual imagery with philosophical inquiry, asking:

In the quiet of dusk, one ponders the origin of evil. How could our separation from goodness arise? Can evil exist without us? Could cloud and lake have also fallen?

Deahl’s reverence for the land is tinged with an awareness of humanity’s flawed relationship with nature.

After reading these four books bound into one collection; Four-Square Poems, one has to simply say that Deahl’s style is characterized by both its linguistic richness and intellectual depth. His use of imagery is vividly vibrant as well as metaphorically descriptive but always accessible. For this James Deahl you go onto my list of top ten best living Canadian poets.

published by Wet Ink Books

Review essay by Brian T.W. Way

The hum of the Star Fire’s engines filled the cockpit with a soothing rhythm as Riz Talon adjusted the navigation controls. His sharp eyes scanned the glowing holographic map, tracing the edge of the Zetarian Empire’s territory—uncharted space for most Federation ships but familiar ground for the Galactic Trio. Outside, the vast expanse of the galaxy stretched endlessly, each star a silent witness to their daring missions. Kael Ventara leaned over Riz’s shoulder, his jaw tight. “Do we have confirmation on the meeting’s location?”

And so begins another dramatic chapter in this second volume of Hans David Müller’s YA fantasy series, The Ventara Adventures (the first novel in the series was The Resilience of Hope, this second, United We Stand). While independent of the first, this volume continues with the rollicking escapades of the previous tale’s Musketeers, the so-labelled ‘Galactic Trio’, Kael Ventara, Riz Talon and Mara Steeler, all ranked officers of the Galactic Federation as they war against the ubiquitous trickery and malevolent forces of the treacherous oligarch, Emperor Dominus Tiberius.

As a sub-genre of the Romance Novel, Science Fiction has its origins in the seventeenth century. While many earlier, even ancient texts from Gilgamesh to the Mahabharata, even the Holy Bible, imagine other-earthly domains with supernatural elements, the stage for Science Fiction was really set in the Age of Enlightenment with dual arrivals: the establishment of narrative prose fiction as a legitimate genre and the explosion of a scientific revolution in Astronomy, Mathematics and Physics. Kepler’s Somnium, Godwin’s The Man in the Moone and even Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels all vie for the prize as the first pure tale of Science Fiction, but Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is, arguably, the true origin of the genre. There, scientist Viktor Frankenstein brings to life the new Prometheus, supernatural, alien, abandoned, cerebral, engaging the reader in a discourse that explores the very essence of what it means to be human, to be a creator, a parent, God. Afterwards, speculative writings by Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, Asimov and Clarke, Heinlein, Bradbury, Burroughs, Dick, Le Guin and many others emerge in every society, every culture. And in Space Odessey, Star Wars, Blade Runner, Star Trek, Alien and such, film and television popularized the genre even more. Whatever its cultural iterations or relative quality, Sci-Fi always remains intellectual in nature, with science, imagined or actual, with ideas and issues at its core, (and, of course, the human response to same). By the mid-twentieth century, it also spliced itself into fiction aimed at an adolescent market. Heinlein wrote a series of ‘Rocket Ship’ books for Scribner in the 1940s, a deluge of Bfilms aimed at teenagers filled matinee screens, and the likes of Tom Swift, Flash Gordon, and Buck Rogers blasted into print and celluloid. Like all innovative and enduring literature written for children, effective YA SciFi never condescends to its audience, always remaining both simple and complex, always inventing and reinventing folk story, legend and myth, always challenging the human imagination with the prospect of new ideas and old wisdoms (or lack thereof).

And with the U.S.S.R.’s launch of sputnik in the late 1950s, the ‘space race’ was initiated and Science Fiction seemed neither quite as fanciful nor as out-of-joint as once it did.

As a YA novel, Müller’s United We Stand is truly a sponge, absorbing, blending and occasionally manipulating aspects of the Sci-Fi canon from all directions of the fictional galaxy but, mostly, one senses, from that world envisioned across the silver screen. In its speed, armament and maneuverability, the slick battleship Star Fire is certainly a nod toward space-craft such as the Millenium Falcon, USS Enterprise or Battlestar Galactica; as with those spaceships, the Star Fire becomes a personified character in the fiction, alive and active: “High above Lumina, Riz led a squadron of fighters against the imperial fleet. The Star Fire darted through enemy lines, its sleek frame outmaneuvering

larger, more cumbersome ships.” The three principal heroes of the novel, Ventara, Talon and Steeler, like daring Jedi knights, engage their enemies with sword and blasters, certainly an echo of Star Wars’ many duels with lightsabers and blaster-pistols and, further back, the swashbuckling conflicts of Dumas’s eternal inseparables, Athos, Porthos and Aramis, although D’Artagnan, the principal protagonist of that classic novel, never materializes. Queen Anne, the Queen of France, (aka Princess Leia!) does, though, in the form of Princess Quann of Lumina, a determined champion of justice and hope. All of the protagonists are recognizable in act, deed and beliefs, the good promoting the ideals of freedom and fairness, the bad, such as Tiberius or Loanus (like the villainous Cardinal Richelieu or the archetypal Sith Lord Vader), seeking domination and control. The familiar mantra of The Three Musketeers is repeated numerous times throughout the book and becomes an overt theme of the novel. As Zane remarks in one of his speeches: “In the vast expanse of our galaxy, no world stands alone; each is a vital part of the cosmic whole. Together, we embrace the creed of ‘All for one, and one for all’.”

United We Stand dramatically offers most of the other aspects typical of YA Science Fiction. Space travel is a given, exploring strange new worlds, seeking out new life, going where no-one has gone before. From the desert landscapes of Duneara and the moon-scapes of Luna, the setting is partly embedded in Earth’s Solar System, and partly in distant alien worlds, in particular Quann’s home-world of Lumina where a clandestine espionage plot is underway auguring the rise of greater, darker conspiracies. This fusion of genres, in this case Science Fiction and the Spy-Thriller, is also often a feature of YA SciFi, often providing a complex arena in which the beliefs and values of the characters are tested. In this case, the Galactic Trio burrow into the villainous conspiracy, unwavering to their ideals. Structurally, the plot of United We Stand unfolds episodically, one dramatic event unwinding, then another, then another, a cinematic novel, frame by frame chattering through disparate scenes and adventures, robotic at times, but apropos, stylistically mimicking the kind of piecemeal text some AI program might write today. Its movement is also reminiscent of the classic cliff-hanger style employed in so many of the juvenile books of the 1940s and ‘50s, or even of the serial-matinees that ran Saturday after Saturday in movie theatres, dire, life-threatening events halting in mid-action to lure audiences back from week to week, then plunging forward into the story once again.

The characters in United We Stand fit comfortably, faithful to this

Romance genre, true, singular, unchanging, determined to follow whatever ‘force’ they have chosen for their life’s path—the good are good and the evil, notso-much. This is the singular, defined formula of Romance literature, staunch, unflinching caricatures, not soul-searching as much as belief-driving. Although Dumas’ Musketeers show difference (Athos is a drunk in a failed marriage, Porthos, a dandy, and Aramis, a womanizer), for the most part, like the ‘Galactic Trio and the triad from Star Wars, they are solid, one-dimensional and ever-true as if forever frozen in carbonite; similarly, the plot-lines are determined, predictable. Following this path, United We Stand leans toward the didactic often telling more than showing and always promoting a defined set of values. The views of its principal characters, those who conquer the villains of this galaxy, are iterated routinely, without doubt or hesitation—heroism, courage, honesty, friendship, loyalty, resolve. The reader is told about such values over and over. Speeches by Princess Quann, Ambassador Zane, General Thorne and others continually reinforce these creeds, and interlocutory epilogues between each chapter appear as brief moralistic poems, akin to propaganda posters that might have been glued to the worn brick walls of the 1960s’ Berlin where Müller grew up: for example, between Chapters 4 and 5:

When we stand united with new allies, our strength transcends boundaries, our resolve becomes unshakable, and no force in the galaxy can break the will of unity. Together, we are a force of unwavering determination, unstoppable in the face of any challenge.