Choosing a Medicare Plan Isn’t Just About Coverage; Better Health

TRAVEL: 36 Hours in Kauai, Hawaii, D5

HOLIDAYS: Bright Nights prepares for 31st season, D9

EXHIBIT: ‘Magical Beings in Picture Book Art’ at Carle Museum, D9

TRAVEL: 36 Hours in Kauai, Hawaii, D5

HOLIDAYS: Bright Nights prepares for 31st season, D9

EXHIBIT: ‘Magical Beings in Picture Book Art’ at Carle Museum, D9

Every fall, millions of Americans face the same daunting question: Which Medicare plan is right for me?

By Sarah F ernandes Health New England

The answer, too often, is reduced to a checklist: hospital coverage, prescription benefits, maybe dental or vision. But for many older adults, especially those navigating chronic conditions, caregiving responsibilities, or cultural barriers, the real question isn’t just about coverage. It’s about fit.

Fit means more than matching a plan to your medical needs. It means finding a plan that understands your life—your routines, your relationships, your values. It means choosing a health plan that reflects who you are, not just what you need.

What “Fit” Means to You

The right fit might mean access to a care team that speaks your language or understands your cultural background. It could also mean help with transportation to appointments, or mental health support that doesn’t feel like an afterthought. It might mean knowing that your plan includes wellness programs that help you stay active and connected, or simply that someone from your community— not thousands of miles away—will pick up the phone when you call with a question. These factors make the difference between feeling cared for and feeling lost in a system, which can be overwhelming.

The Limits of Coverage

Traditional Medicare covers a lot, but it doesn’t cover everything. And it doesn’t always make it easy to navigate care. That’s where Medicare Advantage plans come in, offering additional benefits, such as dental, vision, and hearing, and more coordinated support. But even among those plans, your experience can vary widely.

Why Fit Goes

Beyond Benefit

Health isn’t just clinical, it’s personal. It’s shaped by where you live, who you care for, how you move through the world. That’s why Health New England, your local not-for-profit health plan for almost 40 years, has built a

model of care that reflects the everyday realities of life in Western Massachusetts.

That means:

Wellness programs that help you stay active and socially engaged.

• Support services that make it easier to manage chronic conditions or get to appointments.

• Care coordination that helps you navigate specialists, prescriptions, and follow-ups.

Community investment that ensures your plan is rooted in the same neighborhoods you are.

It’s not just about what’s covered. It’s about how you’re cared for. Some health plans prioritize convenience.

Others focus on cost. But a few, like Health New England, your local health plan, are working to build something deeper that’s rooted in connection, trust, and understanding. Finding Your Fit

If you’re reviewing your Medicare options this year, consider asking a few different questions:

• Does this plan reflect my values and priorities?

• Will I feel supported, not just medically, but emotionally and logistically?

• Does my plan know and invest in my community here in Western Massachusetts? Because when your health plan fits, it doesn’t just cover you. It empowers you. And that’s something worth choosing.

Sarah is dedicated to helping people get the right Medicare coverage for their

Aging changes the human body in myriad ways. But even with those changes, seniors’ bodies have many of the same needs as the bodies of their younger counterparts. Exercise is one thing the human body needs regardless of how old it is. But some exercises are better suited for particular demographics than others. Walking, for example, is an ideal activity for seniors, some of whom may be surprised to learn just how beneficial a daily stroll can be.

Walking strengthens

The Mayo Clinic notes that regular brisk walking strengthens bones and muscles. Intensity is important when looking to walking to improve muscle strength. A 2015 study published in the journal Exercises and Sports Sciences Reviews found that achieving a 70 to 80 percent heart rate reserve during workouts lasting at least 40 minutes four to five days per week can help build muscle strength. GoodRx defines heart rate reserve as the difference between your resting and maximum heart rate, so it’s important that seniors looking to walking to build muscle strength exhibit more intensity during a workout walk than they might during a recreational stroll.

Overweight and obesity are risk factors for a host of chronic illnesses, including diabetes and heart disease. The Mayo Clinic notes walking can help seniors keep pounds off and maintain a healthy weight. In fact, SilverSneakers® reports that a 155-pound person burns around 133 calories walking for 30 minutes at a 17-minutes-per-mile pace. A slight increase in intensity to 15 minutes per mile can help that same person burn an additional 42 calories.

It’s long been known that walking is a great way for seniors to reduce their risk for cardiovascular disease. In fact, a study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society noted in 1996 that walking more than four hours per week was associated with a significantly reduced risk of being hospitalized for cardiovascular disease. How significant is that reduction? A 2023 report from the American Heart Association indicated people age 70 and older who walked an additional 500 steps per

day had a 14 percent lower risk for heart disease, stroke or heart failure. In addition, the Department of Health with the Victoria State Government in Australia reports walking also helps seniors reduce their risk for colon cancer and diabetes.

Researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health note that replacing one hour of sitting with one hour of a moderate activity like brisk walking can have a measureable and positive effect on mental health. The researchers behind the study, which was published in the journal Psychiatry in 2019, saw a 26 percent decrease in odds for becoming depressed with each major increase in objectively measured physical activity.

Walking can benefit all people, but might be uniquely beneficial for seniors. Walking is free, which undoubtedly appeals to seniors living on fixed incomes, and it’s also a moderate intensity activity that won’t tax seniors’ bodies. Such benefits suggest walking and seniors are a perfect match.

Physical activity is a valuable tool in the fight against chronic disease and other conditions.

In fact, the Cleveland Clinic highlights physical activity among its nine ways to prevent disease in an effort to live a long and rewarding life. Children, adolescents, young adults, and even men and women in middle age may not face too many physical hurdles when they try to exercise, but seniors are not always so lucky.

Aging men and women with mobility issues may wonder if they can reap the rewards of physical activity, and thankfully there are many ways to exercise even if getting up and going isn’t as easy as it might have been in years past. Sometimes referred to as “aerobic exercise” or simply “cardio,” cardiovascular exercise is an umbrella term that encompasses a wide range of physical activities that raise the heart rate and improve endurance. Seniors with mobility issues can look to various forms of cardio for inspiration as they seek to be more physically active without compromising their overall health.

Walk your way to a healthier you

issues because it need not be physically demanding and it’s safe to walk just about anywhere. Walking in a place such as a local park can be particularly good for older adults because they can take periodic breaks on benches if aches, pains or stiffness is affecting their ability to keep moving.

Take up swimming

Walking is a form of cardiovascular exercise that is ideal for older adults with mobility

Swimming might be tailor-made for seniors with mobility issues because it’s a great workout and exercising in water tends to be less taxing on muscles and joints. The Cleveland Clinic notes that swimming promotes heart health, strengthens the lungs, helps to burn calories, and builds muscle, among other benefits. And many seniors find swimming is just as fun in their golden years as it was in their youth, which means aging adults might not face problems with motivation when the time comes to get in the pool.

Use an exercise bike or portable pedal exerciser

Cycling is a wonderful exercise but one that seniors with mobility issues may feel is no longer possible. If doctors advise against riding a traditional bike, an exercise bike or portable pedal exerciser can provide many of the benefits of cycling without as great a risk for accident or injury. A portable pedal exerciser can be carried to a park, where seniors can still spend time in the great outdoors, which is one of the most appealing reasons to get on a bike and go.

Take beginner yoga or tai chi

HelpGuide.org notes that gentle yoga or tai chi can help to improve flexibility and reduce stress and anxiety. Though yoga and tai chi can provide as much demanding physical activity as individuals allow, beginner classes in each discipline don’t require much movement but do provide enough for seniors hoping to be less sedentary. Even seniors with mobility issues can find safe and effective ways to be more physically active. Prior to beginning a new exercise regimen, seniors with mobility issues are urged to discuss activities with their physicians.

here are many reasons to welcome the arrival of winter each year. The holiday season, recreational activities like skiing and snowboarding, and the undeniable beauty of snow-covered landscapes are just some of the reasons to look forward to winter. Winter certainly has its positive attributes, but some may shudder at the thought of colder temperatures and shorter hours of daylight. In fact, some people dislike the cold so much they take to the road each winter and make for locales noted for their mild temperatures. Snowbird is a term used to refer to individuals who depart their homes around the beginning of winter so they can spend the ensuing months in warm climates. Snowbirds often are retirees, but the flexibility of remote working has enabled more and more working professionals to become snowbirds, too. Those considering a pivot to the snowbird lifestyle can consider these tips to make that transition successful.

Find the right locale

Those new to the snowbird lifestyle might assume anywhere that isn’t cold will fit the bill, but warm weather isn’t the only variable to

consider when choosing where to spend your winters. Many snowbirds spend several months at their winter destinations, so you will want somewhere that can accommodate the lifestyle you’ve grown accustomed to. First identify your priorities and then consider variables like the accessibility of nightlife, the availability of recreational activities and opportunities to socialize. A warm but especially remote location might appeal to some, but those who like to get out might do best spending their winters in a more vibrant locale.

Get a firm idea of the cost

Though there’s ways to save on the snowbird lifestyle, it can be costly. Whether you plan to rent a winter home or purchase a second home, there’s notable costs that come with each approach. The costs of renting might seem more straightforward, as renters may think a deposit and monthly rent is all the added expense. But snowbirds who plan to work during the winter will need to consider the tax implications if they will be living and working in a different state or province. Buying a second home also comes with its own tax implications, so it might be best for aspiring snowbirds to work with a certified financial professional who

can help them navigate those costs. Certain locales may be tax-friendly for retirees, who also can work with a financial professional to identify locations where the financial implications of snowbirding might not be too significant.

Don’t forget your pets

Pets merit consideration when pondering the feasibility of the snowbird lifestyle. If you plan to rent lodgings for the winter, you must find a pet-friendly option, which can prove difficult depending on the type and size of your pet(s). Pets’ comfort also merits consideration. If you have a dog, a winter residence with access to a yard or nearby dog park should be a priority. And some complexes that specialize in offering winter lodgings may restrict pets or charge hefty fees to allow them.

Don’t forget your current home

Snowbirds also need to arrange for the homes they live in most of the year to be looked after. If you plan to rent your primary home over the winter, that might come with hefty tax implications. If not, someone will need to look after the home while you’re gone. Snow removal and security are two notable components of winter home care that will need to be arranged before you head for warmer locales.

The snowbird lifestyle is tailor-made for people who prefer year-round warm weather. But several variables merit consideration before adults can commit to the snowbird lifestyle.

The human body undergoes an assortment of changes over the course of a lifetime.

Some of those changes are visible to the naked eye, but many more are not. The body’s changing needs in regard to nutrition is one alteration that people cannot see.

A nutritious diet can be a building block of a long and healthy life. Nutritional needs change as the body ages, and recognition of those changes can help people rest easy that their diets are working in their favor and not to their detriment.

Calorie needs

The body requires fewer calories as individuals reach adulthood. That’s because muscle mass begins to decrease in adulthood while fat increases. The National Institutes of Health notes that

muscles use more calories than fat throughout the day, so it makes sense that a body experiencing a decline in muscle mass will require less calories than one in which muscle mass is on the rise. No two individuals are the same, and some adults exercise more than others. So it’s best for adults to consult their physician to discuss their own calorie needs and then adjust their diets based on such discussions.

The American Heart Association notes aging adults’ calories should come from nutrient-dense foods like vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean meat, and low-fat dairy. This recommendation aligns with adults’ declining calorie needs, as nutrient-dense foods contain ample amounts of protein, vitamins and/or minerals but do not contain a lot of calories.

Water needs

It’s vital for aging adults to make a concerted effort to drink water each day. The

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion notes that the sensation of thirst declines with age. Aging adults who are unaware of that unique biological reality may be risking dehydration because they are not compelled to drink water throughout the day. The Cleveland Clinic notes that dehydration can contribute to dizziness, weakness and lightheadedness, among other symptoms. Those symptoms can be particularly menacing for older adults, who are at increased risk for potentially harmful falls even if they are not dehydrated. The body still needs water as it ages, and seniors taking certain medications may need more than usual due to medication-related fluid loss. These are just some of the ways nutritional needs change with age. Adults are urged to pay greater attention to diet as they age and make choices that can counter age-related changes in their bodies.

By Sarah Bahr

The New York Times

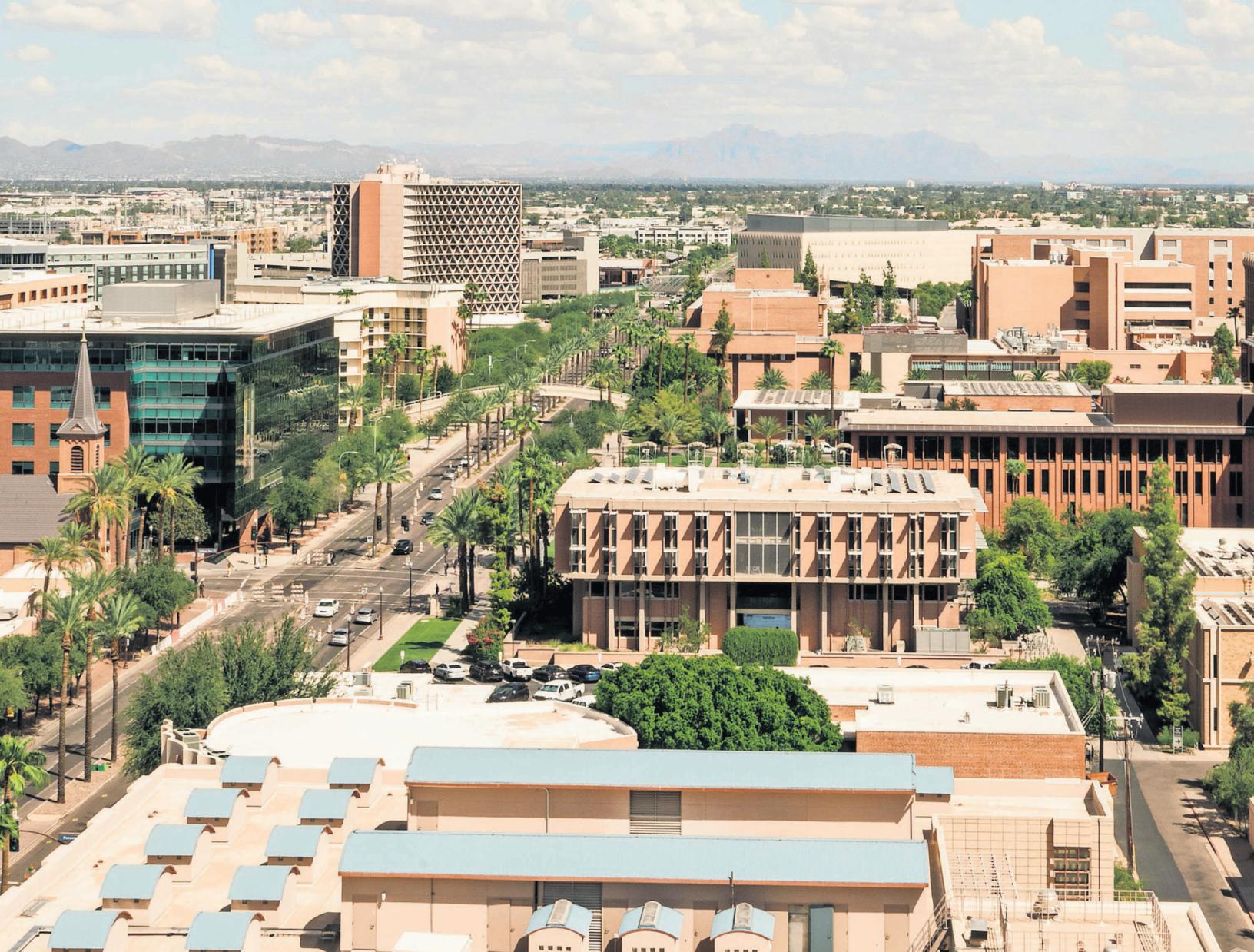

On a sweltering, 100-degree morning in Tempe, Arizona, Roger Weinreber made his way across the street from his apartment to the woodworking studio on the campus of Arizona State University.

“Hi, Roger!” a young woman wearing a striped crop top and olive cargo shorts said as he walked in. “Nice to see you!” “Good to see you,” he replied. He set a black wire sculpture he had made down on a wooden table covered with long brown boxes and orange and blue spring clamps.

A handful of the class’s 11 students had already gathered, and he walked around, chatting with them. But Weinreber isn’t a student. He’s their teaching assistant — who celebrated his 80th birthday.

“The students love Roger,” said Damon McIntyre, an instructor for that morning’s advanced wood shop class, whom Weinreber has worked with for the past 2-1/2 years. “He’s such an asset.” Weinreber is one of 373 residents at Mirabella, a retirement community that opened at Arizona State in 2020. They live in the heart of campus in a 20-story high rise and take classes, attend athletic and performing arts events, sit on thesis committees and help international students practice their English skills. For retirees, university retirement communities offer the option to indulge their passion for lifelong learning in an environment that allows for intergenerational interaction with younger students.

“It’s interesting to see their thought process, and to recognize the difference between my generation and subsequent generations,” said Weinreber, who moved to Mirabella with his wife, Mary Weinreber, 80, in 2023.

“Things that I might take for granted, they look at and say, ‘What?’” Since the 1990s, at least 86 of these communities have opened across the country, including the Village at Penn State in State College, Pennsylvania; University Commons at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor; and Vi at Palo Alto at Stanford University in California.

There has been a particular boom in the past 15 years, said Andrew Carle, an adjunct lecturer on aging and health issues at Georgetown University, who developed a website to track them.

“Some of us are looking at 20, 30 more years,” said Carle, 66. “So we want to do something other than just play another round of golf.”

Many Mirabella residents, all of whom are at least 62, volunteer as teaching and lab assistants; participate in the university’s pen pal program, which pairs them with college-age students; or serve as informal mentors, allowing them to pass on the knowledge they’ve acquired in their careers to the next generation, said Lindsey Beagley,

with us, which is nice,” she added. “But I guess for them, it’s in a nonjudgmental environment. I’m not their mom.” University retirement communities appeal to the baby boomer generation, people born between 1946 and 1964, because it is not only one of the most well-educated, but the most social, Carle said. It also helps that boomers — who make up approximately 20% of the U.S. population — control more than half the nation’s wealth.

Indeed, one of the biggest advantages to a university of having a retirement community on or near its campus is financial, Carle said, citing revenue from land leases, name and licensing rights, contract services such as

month. The entry fee is 80% refundable to residents or their estate if they leave the community.

“Baby boomers did well for themselves, and now they’re willing to spend,” Carle said.

“We can have a separate conversation about who can or cannot afford senior living,” he added. “But university retirement communities are actually a great deal if you look at their pricing — it’s almost always about the same as traditional senior living in the same market, but you’re getting tremendously more value for it.”

That was Cindy Adams’ thinking.

“We had to raise our budget about $100,000,” said Adams, who said Mirabella’s full

in which older adults offer a listening ear to anyone who approaches. Those days have been especially rewarding.

“They will come up and say, ‘Can I pet the dog?’” she said of her Cavalier King Charles spaniel, Winnie, whom she brings along. “But they really just want to talk. I’ve talked to kids who were homesick, or going through whatever personal situation, and they were afraid to talk to someone because they might be judged. And we’re not going to judge.”

Even residents who don’t seek out students find them in their midst: Many are employed at Mirabella, where about 70 students work as technology assistants, valets, and health care and dining

attend and to know that they appreciate it so much.”

There has also been concern that the presence of older adults on campus would kill the vibe at universities like Arizona State, which has long had a party school reputation. In fact, in 2022, the senior living community sued an on-campus bar and concert venue, Shady Park, asserting that its noise levels were excessive. (The suit was later settled, and the case was dismissed. Shady Park closed in August.)

For Bailey, though, his experiences at Mirabella “have fundamentally changed the way I view making music and community.” He is working to create a nonprofit that partners with retirement communities and university music programs to create musician-in-residence positions. Karis Houser, a 21-yearold neuroscience major at Arizona State, said she found the idea of older adults taking classes alongside undergraduates “really cool.”

“It’s great that they’re keeping their brains active,” she said. It remains to be seen whether university retirement communities will prove as popular with future generations of retirees, Carle said. Technology, he said, will make it easier for them to live alone and still have their daily needs met.

“Whether that’s good or bad is for social scientists to assess, but it could result in less of a need to physically gather in any singular location, including a URC,” he said.

42, Arizona State’s senior director of lifelong university engagement. Approximately 80% hold at least a master’s degree, and 19% are retired university faculty. That’s not to say they don’t still get first-day-of-school jitters.

“I took a Spanish class last semester, and it was me and 12 teenagers who were 18, 19. I thought, ‘Oh, how’s this going to go?’ But they were all very friendly and respectful and engaging,” said Cindy Adams, 76, a former regional CEO for the American Red Cross who moved into a two-bedroom apartment at Mirabella with her husband, Bill Adams, 78, last fall. “They’re very free to talk

medical staff and shared services such as food, maintenance, security and transportation.

At a “highly integrated” university retirement community, he said, these benefits can exceed $2 million per year, often for land or space that was not otherwise being used. Entry fees at Mirabella start at $490,600, on top of monthly fees that start at $5,541. The most expensive unit, the deluxe two-bedroom penthouse on the 20th floor with a den and a mountain view, goes for $8,838 per month, plus an entry fee exceeding $1 million. By contrast, the median cost for independent senior living in Arizona is about $2,700 a

spectrum of continuing care, including assisted living and memory care units, was a selling point. “But you save your whole life, and then there’s a time to spend.”

For Adams, the draw was not only the variety of classes offered, but the opportunity to live among younger students and participate in campus activities.

“It’s almost like working full time again with all the things that we’re involved in here,” said Adams, who edits an online newsletter for the university retirement community, chairs its welcome committee and acts in its drama group. She also volunteers twice a month with the school’s friendship bench program,

employees, as well as in other roles. Four music, dance or theater graduate students each year are afforded free housing in the community in exchange for giving regular performances.

For students like Caleb Bailey, a doctoral student studying classical guitar performance who is the artist-in-residence program coordinator, the recitals are an opportunity to not only experiment, but to do so for an enthusiastic audience.

“There’s been a really good turnout for all our concerts so far,” Bailey, 27, said of the hourlong performances, which can attract more than 200 residents. “It’s motivating to have so many people

For now, though, communities like Mirabella are booming. As of mid-October, 94% of its independent-living apartments were either reserved or being lived in, with the community on track to be full by the end of next summer, said Tom Dorough, 59, the executive director of Mirabella. (Deluxe two-bedroom apartments with dens are the most popular.)

For engaged residents like Weinreber, the teaching assistant, going to school forever — and learning just as much, if not more, from his mentees as he imparts — is a dream.

“I’m not going anywhere” Weinreber said as he headed off to check in with another student. “I just love it here.”