Life is written

THE

LUCKY

STORY OF A

MAN

Claudio Sabbatini

This book celebrates the life of Claudio Sabbatini, a man who has lived an extraordinary life and is a gifted, engaging story-teller. He now lives with dementia, which can cause memories to become tangled. Even without dementia, discrepancies often arise in the historical recollections of individuals.

In recording Claudio’s life, we encountered some discrepancies and tangled recollections. Where it was not possible to resolve them, we shared the story as told by Claudio. Think of this as his assisted autobiography. The stories are mostly told by Claudio, with assistance from family and friends. It is a private history, intended for close family and friends.

Written by Jennifer McNeice

Acknowledgements

Many people have contributed to the telling of Claudio’s story.

Claudio’s partner Lyn was present at all of his interviews and added a lot of additional information. She made an enormous effort to obtain further details and photos from family and friends.

Claudio’s daughters, Isabelle and Sharon, were also interviewed. They were helpful and generous with their recollections.

Claudio’s grandsons, Rick and Max, wrote about their memories in entertaining contributions, and Rick went out of his way to provide photographs.

Contents Introduction 3 Contents 3 We had a good life 5 War is shocking 7 Life is written 13 There was no future in Italy 15 We learned about life and how to survive 19 You have to work hard 23 Family means a lot 27 Enjoy life 35 She’s a good helper 41 A good life 43 Reflections 47 Notes 50 Introduction

Designed and printed by Pressroom Philanthropy Level 19, 41 Exhibition St, Melbourne, VIC 3000. pressroomphilanthropy.com.au

Pictured left, every morning Claudio buys the paper and enjoys a pre-breakfast ice cream.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 3

4 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

We had a good life

At first, Claudio’s words paint a charming picture of another place and time.

We walked along Via San Nicola and up the hill to the Piazza della Borsa and played basketball in the piazza. In summer we swam in the Adriatic Sea at Barcola, near the Habsburg’s Miramare Castle. Sometimes, on a fine day, we rode in a cable-hauled tram on the steep funicular railway to Villa Opicina. From there we could see everything: all the vines, the hills and the beautiful coastline of Trieste. It was very nice.

My mother, Leonilda (nee Obran), was Austrian and my father, Bruno Sabbatini, was Italian. He was a widower and my half-sister from his first marriage was much older than me. She moved away to Ancona.

We had a good life. My father was a quartermaster, responsible for ship supplies. He worked for Lloyd Triestino. Our only problem was that he was away a lot. He might be away on the ship for a month and then we might only see him for three or four days before he went away again.

Even the blot of his father’s absence didn’t dull the sparkle of Claudio’s view of his early life. But darker shadows were looming. Claudio could see all of his childhood world, but his world was getting bigger and it was rapidly closing in.

Pictured left, clockwise from top left, Claudio’s mother Leonilda nee Obran; Claudio’s father Bruno Sabbatini; Claudio with bicycle; Leonilda and Claudio.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 5

Pictured below, view of Trieste from Villa Opicina.

6 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

War is shocking

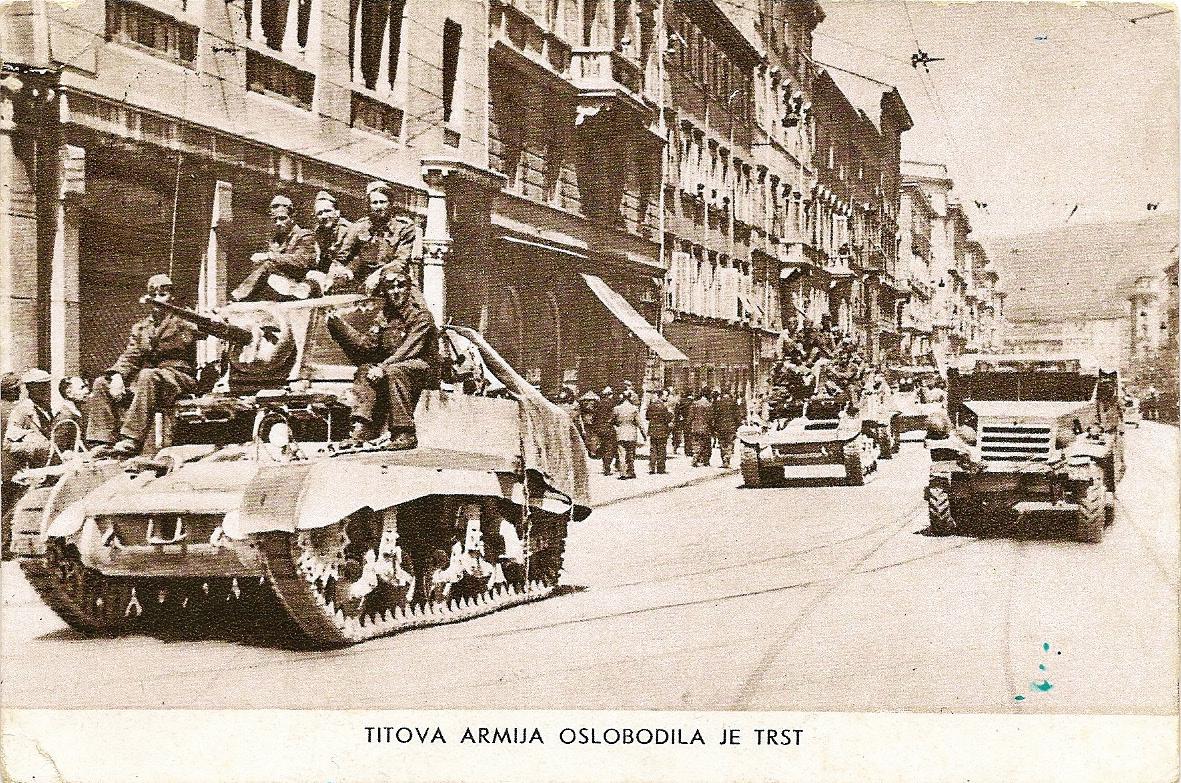

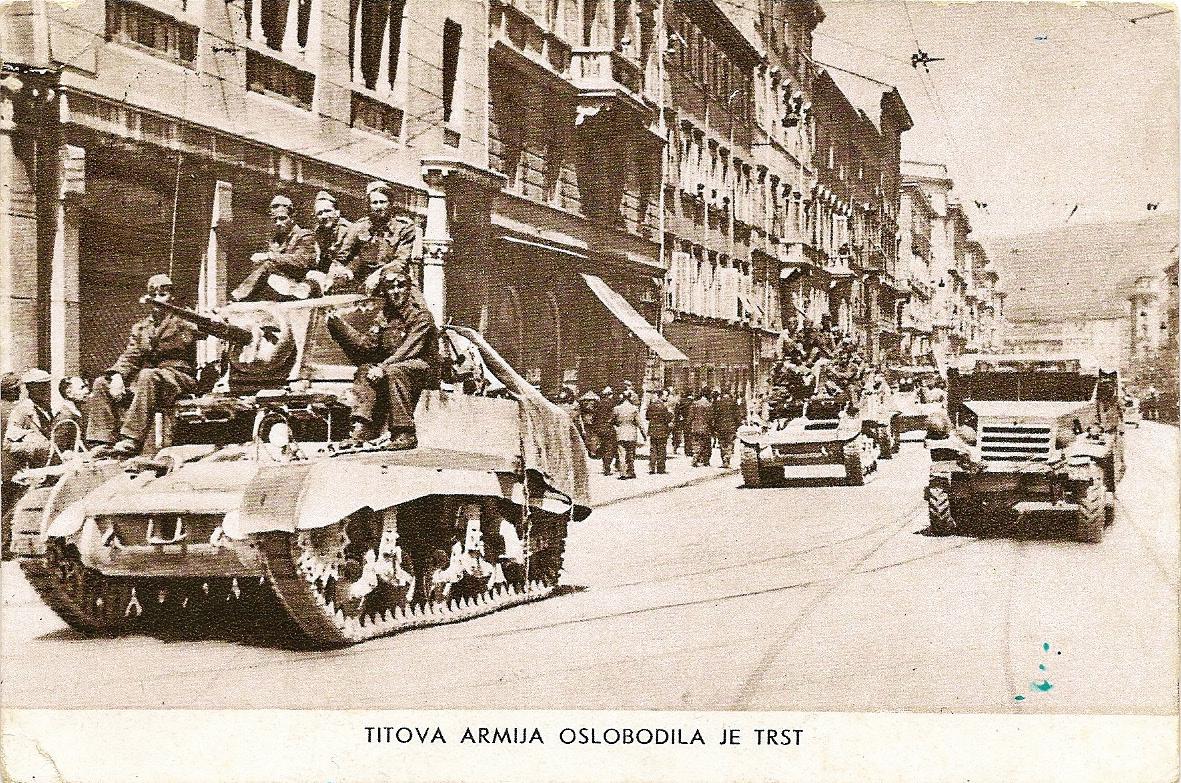

Trieste had been part of the Habsburg AustroHungarian Empire. However, the deep-water port and associated industry was strategically important for merchant and passenger ships, and it was heavily contested. Italy, to the south, and Yugoslavia, to the east, both wanted Trieste. In 1918, after the First World War, Trieste was annexed to Italy. Mussolini, the Fascist leader, was supported by the Blackshirt squads and took control of Italy in 1922.

I was six years old when the Second World War started, and seven when Italy joined the war in 1940, as one of the Axis powers.

In 1943 my father was on a merchant ship carrying supplies to Africa. He couldn’t refuse because it was the only job he had. The Allies torpedoed the ship and he died. I don’t know the name of the ship and I don’t have any memories of time I spent with my father. I was very young when he died, and he was always working, poor bugger.

In October 1943, Italy joined the Allies and declared war on Germany, but Nazi troops occupied, and effectively ruled, Trieste. So, the Allies still attacked Trieste. Claudio does not remember the Nazis in Trieste.

Life was very tough after my father died. There was no welfare or widow’s pension. We always lived on the top floor of the building and there were no lifts. We walked up and down five flights of stairs several times a day. It was good training.

When you lose your parents, it is a very hard life. We couldn’t afford to have a shower in the house. Instead, we walked fifteen or twenty minutes to the public ablutions block. You shower, shave and do everything in there. It was busy. In the house, there was a bucket for a toilet. We closed it up with a lid and took it downstairs to the street. A night truck would come to empty it and take everything away. It was shocking. I must have smelt.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 7

Pictured left, from top, tanks in Trieste; Claudio always lived on the top floor of the building, including this residence in via della Madonnina.

8 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

War is shocking

School discipline was like a military operation. Two children sat at each wooden desk and the teacher stood above us at a lectern. If you wanted to talk to the teacher, you had to raise your hand and you might have to wait for ten minutes. By the time she asked me, ‘Yes Mr Sabbatini, what would you like to say?’ I might have forgotten.

There was no other talking in the class. It was very quiet. I was usually well-behaved, but sometimes I might want to show off. If I overdid it, the teacher would whack me with a cane as she walked past.

I liked school because I liked learning about history and everything, including how to behave. There was always pressure to do well because if you didn’t pass the exam you would have to repeat the whole year. I must have done okay because I was interested and I won a scholarship to do my apprenticeship at the technical college.

I used to walk to and from school every morning. Sometimes I walked with my mother, and when we passed the patisserie with all the creamy pastries and cakes, I would press my face against the window.

Claudio presses his face against the computer screen in our online interview, his eyes open wide with excitement.

My mother would say, ‘Come on, come on!’ because we couldn’t afford them. When she cooked meals for me, I asked if she was having some but she often said, ‘I’m not hungry.’ She was looking after me. Lucky boy.

There was a soup kitchen for people who couldn’t afford to have a proper meal. We took a bowl and lined up in a queue to get a ladleful of soup. I would eat it all but it wasn’t enough, so I took the bowl and got back in the line. Sometimes I got away with it and sometimes they said, ‘You’ve been here before. Get out!’ When you’re hungry, you’re hungry. And when you’re young, it is even worse. But I was lucky. I got some food.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 9

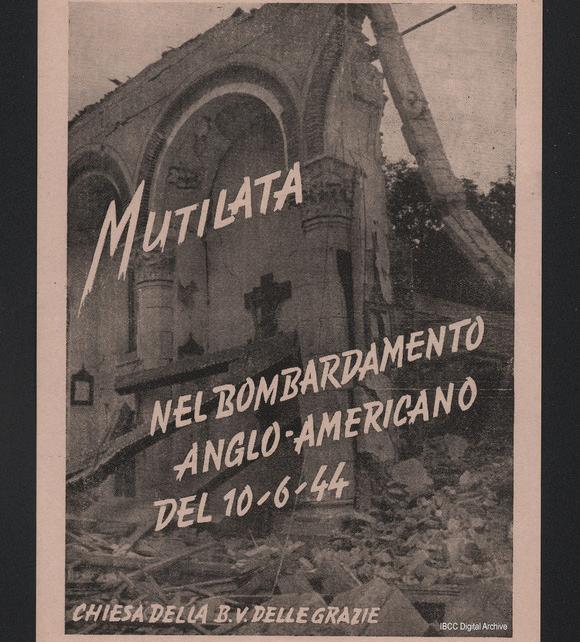

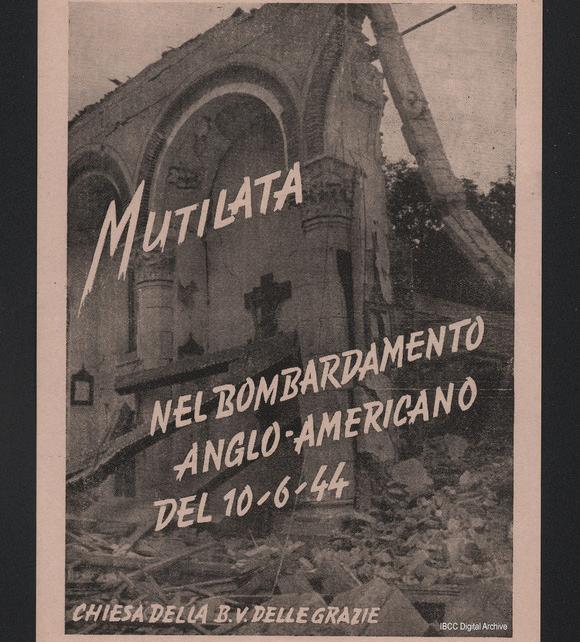

Pictured left, clockwise from top, Claudio at school c1940 (standing far right); Claudio at his confirmation; leaflet about bombing of Trieste.

War is shocking

Life is often measured at the extremes. While adversity tests character, our response to it reveals character. Claudio frequently speaks of a hard life but sees himself as lucky. He focuses on the best part of any situation.

The air raid sirens would go ‘Waaahhh! Waaahhh!’ if there was a plane in the area. Some days there might be several sirens and some days there might be none. It could happen at any time, day or night. When we heard the sirens, everyone ran into the tunnel that had been built for trains and trams. There were enormous, heavy sliding doors to open and close it.

Everyone was crowded inside, and we were scared. We might have to stay there for two or three hours, or longer, until another siren gave the all-clear. It was horrible. No food, no toilets, nothing. But it was war, so you take it as it comes. Usually, everyone went to the tunnel when we heard a siren. At one stage there were days and days of false alarms when we went to the tunnel but nothing happened. Some people became complacent and ignored the siren. They stayed home. Then one day the Allies bombarded Trieste and hundreds of people died. They were mostly women and children because the men were in the war. Shocking. Terrible. War is shocking. There will never be peace in this world.

On 10 June 1944 the Allies dropped 400 bombs on Trieste. Hundreds of people died and thousands were injured.

In 1945 New Zealand soldiers liberated Trieste and made Tito evacuate. I didn’t see them but I remember it. That was a good time. We had freedom.

The war had finished but Tito, the Yugoslav dictator, still wanted Trieste. Allied servicemen stayed in Trieste for a long time, waiting for things to settle down. Otherwise, Tito would have tried to take over.

10 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

War is shocking

The border kept changing, sometimes by as much as 14 miles. In some areas of Trieste, you might be living in Italy one day and Yugoslavia the next.

Although the Germans surrendered to the New Zealand troops, Yugoslavia claimed the city of Trieste. A peace treaty signed in 1947 created the Free Territory of Trieste, comprising two zones. The northern zone included the city and was administered by the Allies. The southern zone was administered by Yugoslavia. The Free Territory existed uneasily until 1954 when 523 square kilometres, including part of the northern zone, were granted to Yugoslavia and 236 square kilometres, including the city, were granted to Italy.

The English, American and New Zealand servicemen used to go the NAAFI (Navy, Army and Air Force Institute) for the music and something to eat. My mother worked there, cleaning up the tables. To make some extra money, she used to collect the cigarette butts from the ashtrays and put them in a bag to take home. I would help her to cut the filters off with a razor blade, unwrap the butts and separate the ashes from the tobacco. My mother rewrapped and sold the tobacco. It was a terrible life. I feel sorry for her.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 11

Pictured below, bombing of Trieste 10 June 1944.

12 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Life is written

One day, I went with my mother to a friend’s farm in Istria, not far from Trieste. I was about nine years old and I couldn’t swim but they gave me an inflatable floatie ring. I put it around my waist and jumped into the dam. But I wasn’t very smart, because I jumped head-first instead of feet-first. The floatie slipped off. It stayed on the surface and I went all the way down. Luckily the farmer saw me go in. He picked me up and got me out.

When I was about eleven years old, the housekeeper and I went to collect firewood in a nearby forest. We picked up what we could find and put it in a rucksack to take home. She was older, about 40 years, and would have been more sensible. But we were some distance apart when I saw a red thing under a tree. It was a Breda Italian hand grenade. I decided to pull it apart and keep it as a souvenir.

It wouldn’t come apart so I banged it against a tree. But nothing happened. Then I banged it against a pillar on a bridge. Still nothing happened. So, I thought, ‘That’s enough!’ and I threw it away. The grenade hit a tree, rebounded and landed at my feet. Then something happened. The grenade exploded and shrapnel made many holes in my feet and body.

The housekeeper started screaming. She was watching over me but she couldn’t do anything for my injuries. Within ten minutes, some Kiwi soldiers just happened to be passing in a jeep. They took me to hospital. My mother came and felt all over my body to make sure I had all my limbs. Then she whacked me and said, ‘You stupid boy!’

I was lucky that God was looking after me. Life is written from the day you are born to the day you die.

Above, watch Claudio talk about the grenade.

Pictured left, from top, Claudio found a red Breda hand grenade; New Zealand soldiers in Trieste.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 13

Scan to watch video

14 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

There was no future in Italy

I left school at around 14 years of age. I did well and was excited to win a scholarship that allowed me to do an apprenticeship at a technical school for three years. Each year I learnt a new trade: auto-mechanics, carpentry and electrics. Then I worked at the Fiat Motor Company factory, assembling the cars that they sell.

There were a lot of cars parked on the roof. During lunchtime another apprentice and I used to race each other. It was lucky we didn’t go over the side. It was five storeys high. We would have killed ourselves and someone else. When you are young, you don’t realise how stupid you are. You do silly things.

If I was taking a girl to the cinema or theatre it was, ‘Yeah, yeah. Aspettami dentro il cinema,’ (meet me in inside). Because I didn’t have the money to pay for it.

To earn some extra money, I worked as an extra in the opera. When they needed someone, a large number of teenagers would line up. The manager always chose me because I was tall and goodlooking. The operas were performed at Castello di San Giusto in summer and at Teatro Verdi in winter.

In Aida I had to carry a female slave across the stage on top of my shoulders. I enjoyed the company and I was paid well for it. I learnt all the songs by hearing them. And I have continued to enjoy opera my whole life. It was a lovely job when I was working during the day at Fiat.

Then Fiat got the contract to supply the auxiliary motors to the migrant ships Australia, Oceania and Neptunia. I worked on the team that did that. We assembled all the pieces and installed them on the ships.

In 1952, when I was nineteen, I knew there was no future in Italy. You get up at half past six in the morning to walk and walk to the shipyard because there is no bicycle. You work all day where they treat you like a slave and then you walk home. It was a long day and there was no money to enjoy life.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 15

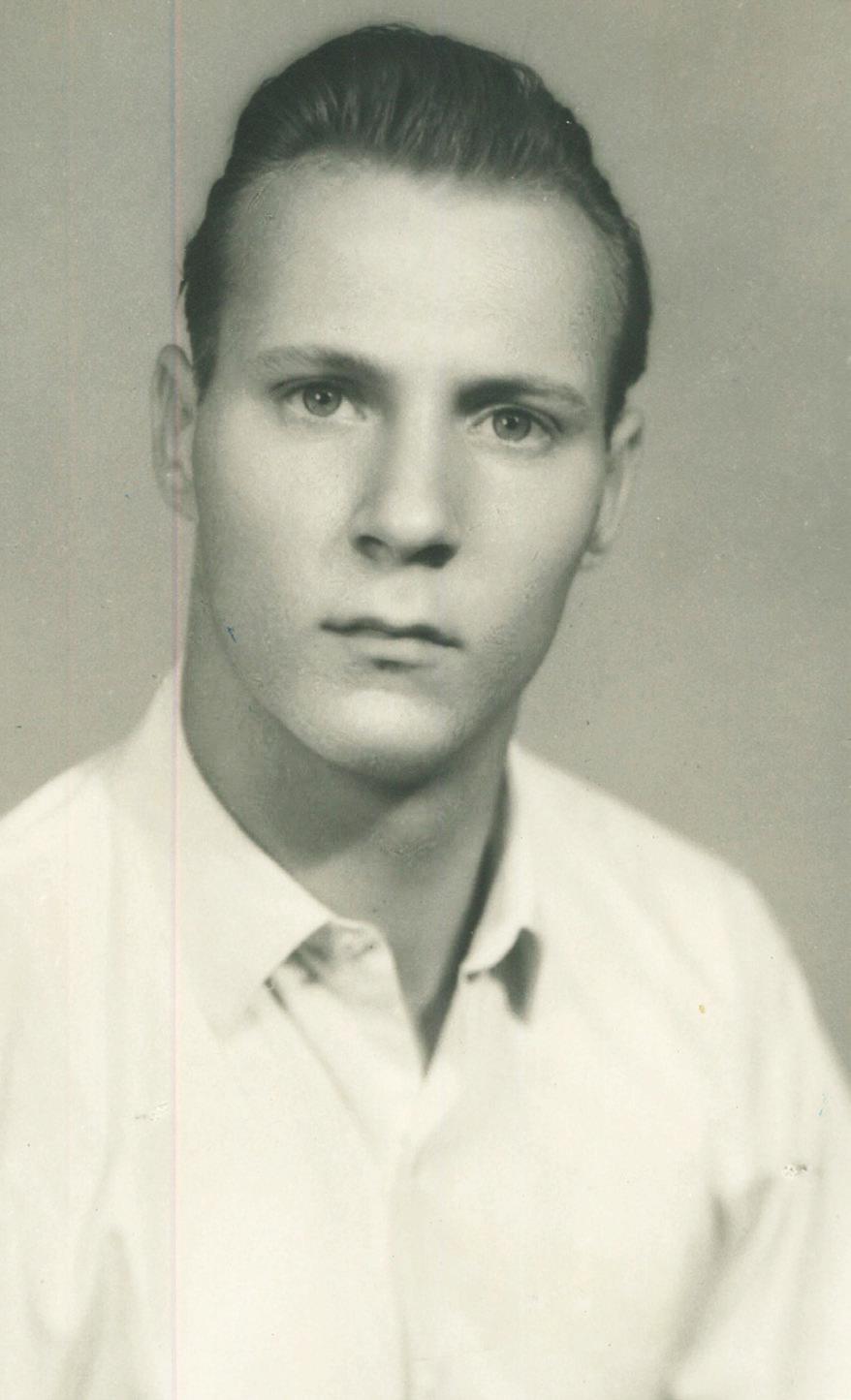

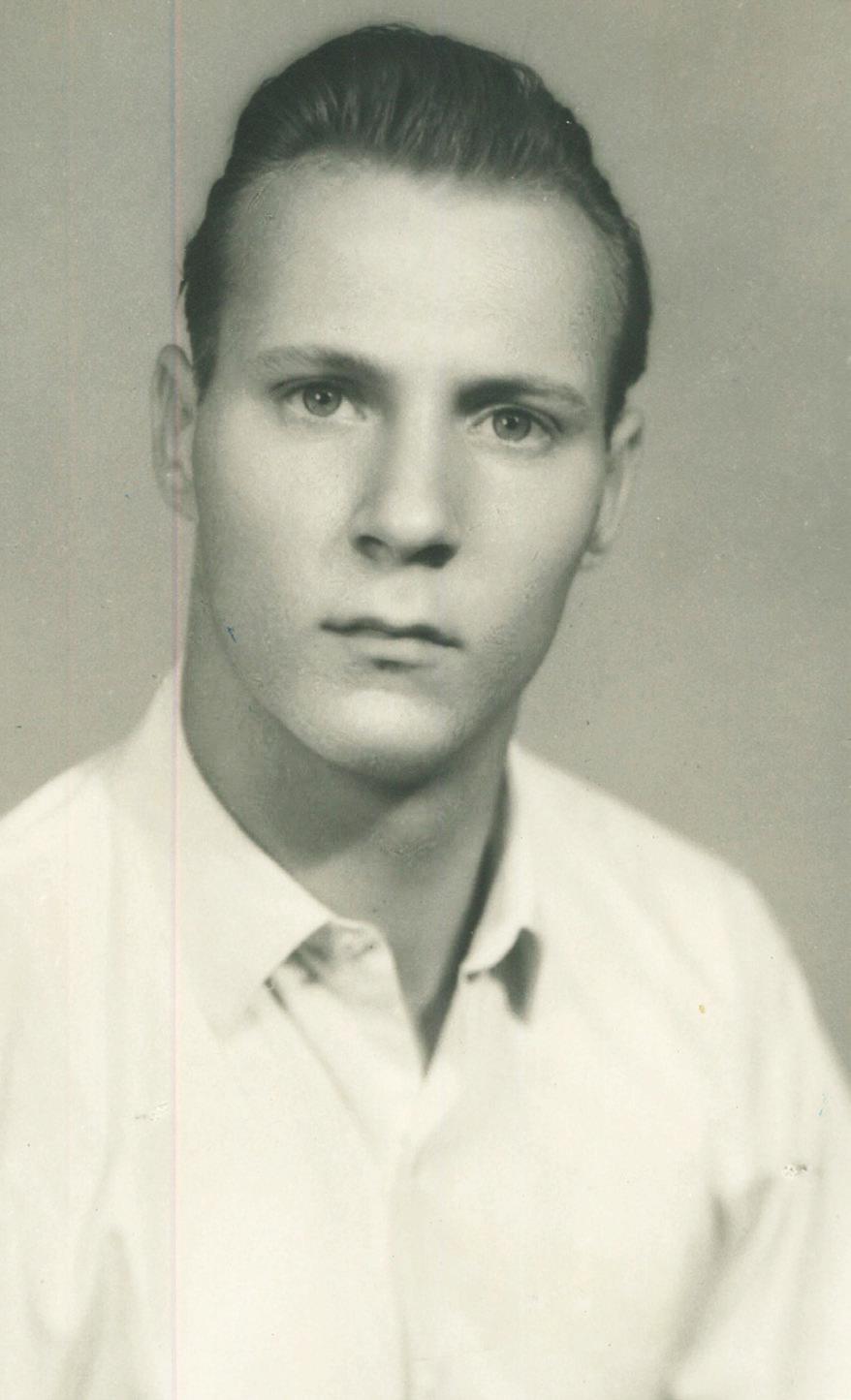

Pictured left, clockwise from top left, Claudio worked as an extra at Teatro Verdi; Claudio 1 September 1951; Lloyd Triestino pamphlet for sister ships Australia, Oceania and Neptunia; postcard of the Australia

There was no future in Italy

I decided I wanted to leave Italy and there were a few places to choose from. I didn’t want to go to Argentina under the dictatorship of Juan Peron. I already had enough of Mussolini the dictator. I didn’t want to go to South Africa because of the racial tensions in the apartheid era. Canada was too cold and icy.

Australia needed young people. I had heard of Australia but I didn’t learn much about it at school. I thought it was a small island and I imagined having a house on the water where you come home from work and go through the house to your little dock with a boat.

I didn’t know it was a continent. But I thought Australia must be a good place because they named a ship after it!

It was hard for my mother when I left. She thought she would be alone and she gave me a medallion that said, ‘Safe travels.’ It was on a gold chain. I told her that I would bring her down to Australia, and I did. Two years later when I was settled, I called her down to Australia and she got a job here.

I travelled on the Sydney in March 1952. On the ship, there was a French lady named Paulette. I had a friend who could speak French and I asked him how I could communicate with this lady and ask her to go for a walk.

Claudio makes his decades-old polite request in French, then translates.

‘Would you like to come tomorrow at 10 o’clock on top of the deck to teach me French?’

She said, ‘Oui.’ So, in the morning I met her, but she said ‘No French. I am going to teach you English.’

Claudio’s partner, Lyn, sometimes refers to Claudio’s charm. She quips that Paulette was one of the reasons the trip was so good. Claudio responds with discretion.

I was a nice-looking bloke then.

16 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

There was no future in Italy

The long voyage to Australia took thirty days but it was a good experience. There was free food, beautiful dancing and lots of women. The ship docked at Fremantle in Western Australia, then went on to Point Nepean in Port Phillip.

They took us ashore and said, ‘Girls this way, boys that way.’ When we were separated, they said, ‘Boys, get undressed. You’re going to have a shower.’ It was very scary because we thought of the gas chambers in Nazi Germany. Then a lot of dust came out. But it was a delousing shower.

Foot and mouth disease had been discovered among passengers from Italy who arrived in Canada. Australia introduced precautions days before the Sydney’s arrival. Migrants arriving in Melbourne were taken to the Quarantine Station at Point Nepean where they had antiseptic treatment, and their clothes and luggage were fumigated. The Graziers’ Association of Victoria wanted the Minister for Health to ban migrants who came from affected areas.

When the Sydney arrived, the quarantine facilities were already overwhelmed by passengers from the Neptunia. The Sydney had to wait in the bay for four hours and, when it was allowed to berth, it was closed completely for 24 hours and nobody was allowed to disembark. Then seven buses carried 209 passengers to the quarantine station.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 17

Pictured below, Claudio’s immigration index card 1952.

18 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Then we went to Bonegilla, near Albury. It was a long trip on the train. It was an old army camp and all the huts had numbers. You had to make sure you remembered your number because all the huts looked the same.

The food was good. There was meat! In Italy we had meat twice a year, at Christmas and at Easter. We couldn’t afford it because my mother was a widow. At Bonegilla I had mutton for breakfast, lunch and dinner. I was happy.

That was good at first, but after a while you get tired of the same thing.

We had mutton with mashed potatoes and peas, but it was tasteless. The food was simple, without the herbs and flavours we have in Italy.

I lived in a room with four single men and double bunk beds. I was lucky I got the top bunk. That meant I had to climb up every night and climb down if I needed to go to the toilet in the night. The ablutions block was very primitive. It was like an old horse stable made of tin and timber, with partitions. It was shocking but I was young and had strong blood. I survived.

In the mornings we would all stand in the assembly area and one man stood on a bench. He would call out, ‘Who wants to pick strawberries? Who wants to cut cane in Queensland?’ All those things. Then one day he said, ‘Who wants to work on the railways?’

Being an engineer, I thought it would be good to fix trains and that sort of thing. So, I put my hand up to work on the railways. After one month at Bonegilla they put me on a train. I was by myself initially, but I started talking to people and made friends.

Despite the language barrier at that time, it seems perfectly natural that Claudio found a way to communicate with fellow travellers. Even now, he frequently illustrates his story with gestures and sound effects, such as the moving train. He also has the type of charm that would allow him to easily make friends with strangers. He is likeable, engaging and good-humoured.

We learned about life and how to survive

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 19

Pictured left, from top, Claudio revisits Bonegilla railway station; Claudio worked in a three-wheeler cart or ‘trike’, similar to this one, at Willbriggie.

We travelled for hours and hours to Narrandera in the middle of nowhere. I call it the Never-Never. There was nothing there.

A man named Bob Cow came to meet me. I didn’t speak English but I looked up ‘cow’ in my translation dictionary. I couldn’t call him Mr Cow, so I called him Bob. We got in his truck and he drove to Willbriggie. There used to be an Aboriginal mission station there.

Bob’s house at Willbriggie was a small weatherboard house. I thought it was an ordinary house. Then he showed me my tent. The tent was 30 or 40 metres from the house and it wasn’t very big. It had four poles, one in each corner. There was another thick tarpaulin on top to help stop the rain from getting into the tent and to protect from the sun as well. Inside there was just enough room for a mattress on the ground, a stool, a Coolgardie safe and my luggage. There was no table or chair. I had an enamel plate to eat from. There was a toilet outside. It had newspaper but no toilet rolls.

The Coolgardie safe was used to store food. It had a wooden frame covered with wire mesh. An iron tray filled with water sat on top and a hessian bag hung from the tray and over the sides of the frame and mesh. The hessian soaked up the water and, as the water evaporated, it cooled the inside of the safe.

Another man worked there too. He was already there before me and he lived in a different tent. He was from southern Italy, but his dialect was so strong that we couldn’t understand each other. I learnt English the hard way. Every week a pamphlet would arrive. It had stick figures to match words. A stick figure pointing at itself was ‘I’. A stick figure pointing away was ‘you’ or ‘they’.

There was a lot of canned food. I was fed up with it and I wanted to get some fresh food. There were a lot of rabbits, but I couldn’t get them. So, I walked and hitchhiked 22 kilometres to Griffith, and bought a .22 rifle and bullets.

When I got back to Willbriggie, I wanted that good fresh food, so I sat under a tree with the rifle. When a rabbit came out, ‘Boom!’ I shot him and skinned him.

20 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

We learned about life and how to survive

Then I had to eat him straightaway. We didn’t have refrigeration, so I ate everything at once.

One day I was walking along and suddenly a crocodile ran in front of me and ran up a tree. I got him, ‘Boom!’ I said to Bob, ‘Look, crocodile!’ He said, ‘Oh no, goanna!’

There was a big river, the Murrumbidgee River, so we went fishing a lot. One day I caught a big fish. I think it was a trout. But I didn’t have refrigeration, so I gave it to Bob to take home.

In Italy we cook with lots of olive oil but I didn’t have any at Willbriggie. So, one day I went to the shops at Griffith. I got olive oil and potatoes. I peeled the potatoes and cut them up in bits and pieces and put them in the frying pan with olive oil. Then the olive oil was all gone, so I added more olive oil. Then more olive oil. I was pleased to have olive oil but I overdid it. I was on the run for a week.

On the railway, I replaced sleepers. We travelled in a three-wheeler cart and we used a rowing action to make it move. When a train came, we had to jump out, take everything out and pull them off the tracks. After the train passed, we had to put everything back again. It was hard yakka. We were paid every fortnight. When I got my first pay cheque, I was very happy. In Italy I had to work for more than a month to earn that much. I like Australia!

Again and again, Claudio is positive despite hardship.

The heat was shocking. There were no showers. The only way to wash was to jump in the dam. There was no fresh water. We would get a canvas water bag from Bob’s house and hang it up for our drinking water. After a couple of days, it was hot water. I tell you what, it is amazing the life I passed through. But still, I like it and I like Australia. That’s why I stayed here. I enjoyed it and I’m very happy that I decided to migrate to Australia.

It was very lonely. There was no radio, no television and no-one to speak Italian with. The contract was for two years, but after one year I had had enough.

We learned about life and how to survive

Above, watch Claudio talk about the crocodile. Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 21

Scan to watch video

22 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

You have to work hard

I had a friend in Sydney. He said, ‘Come to Sydney. There’s a beautiful bridge. You will love it!’ One day I was fed up with my life up at Willbriggie and I packed up all my gear. There wasn’t much gear. I hitchhiked to Griffith and went on the train to Sydney. I loved Sydney, but I didn’t love it too much because it was congested.

Then a friend in Melbourne said, ‘Come to Melbourne. They have little Italy in Carlton!’ So I left Sydney and came to Carlton in Melbourne. It was the best thing I ever did. Carlton is a little Italy.

I shared a room with some other boys and I worked for Dunlop. My first job was fixing tyres. It was hard yakka. Then they put me to another job, painting golf balls. There was a big machine and I moved the balls from one tray to another. I did that all day.

Claudio demonstrates moving his arms back and forth in front of him from one side to another.

I used to go home at the end of the day and say ‘G’day boys, how did your day go?’

Claudio is still moving his arms.

But it was good money because the more balls you paint, the more money you get.

Next, I worked as a bricklayer’s labourer. I had to carry all the bricks to the bricklayer. It was beautiful on the ground floor, but when they got to the second floor, I had to haul all the bricks up to them. It was hard work.

Then a friend said that I should work in construction because I could read the drawings and I could speak Italian. There were different areas of construction like bricklaying and concreting. I chose concrete. It was during the Olympics in 1956 and I named the company Olympic Paving. Later it became Prefabricated Concrete and Terrazzo.

I started with a team of five men and I used a small shed at the back of my house in Thornbury. My work started at a quarter to six in the morning, to organise the jobs and tell the boys where to work.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 23

Pictured left, from top, Tullamarine Jetport 1970s; Claudio’s car was similar to this Chevrolet Impala.

Pre-fabricated terrazzo is a panel that can be used for toilet partitions and wall cladding. I manufactured it in Thornbury. We put it on the truck and the boys took it to the job and installed it.

I did all the quoting. It was terrible when I didn’t have a car. I spent many hours getting to the job on a bus or train. My work day usually finished at six o’clock in the evening. That’s life. You take it as it comes and do everything you can to make money.

As the business grew, we started doing bigger construction jobs. I bought land at 3–5 Sheppard Street, Thornbury and built a factory there. We had three or four teams of men and an office girl to take all the calls. I managed everything to make sure it was under control. If you want to make money, you have to work hard.

In the 1960s I bought a second-hand Chevrolet convertible because I thought I would like to show off. In the summertime it was beautiful to open the roof and feel the fresh air. And show off! You can do that when you’re young. I loved it.

We competed with Luigi Grollo quoting on some of the jobs. Luigi Grollo was a very short little man, and he was often covered in cement dust. Cement dust got everywhere. It stuck on my lungs and I got mesothelioma, but it hasn’t affected me. The doctor said I will die with mesothelioma, not from it.

Luigi never measured a job. Maybe I was pedantic. I used to measure precisely in each direction with a tape measure and work out the square yards. Luigi never did that. He just stepped it out this way and that way, and he always used to beat me on price. I said, ‘Luigi, there are two things. Either you are too cheap on your quotation or you have bloody long feet.’

We worked on Tullamarine Jetport, as it was known when it opened in 1970. The foyer and toilet partitions were all pre-fabricated concrete and terrazzo walls.

24 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

You have to work hard

There were other jobs installing wall cladding and toilet partitions in Melbourne city buildings, including the Commonwealth Centre Building, Collins Place and the Rialto. Lyn tells a story from the early days of her relationship with Claudio. They had walked to Southbank in Melbourne after seeing a show.

It was romantic with all the lights. We went past one of the big hotels and Claudio said, ‘I would like to take you into this hotel.’ I pictured a little round table in the corner with a rose and a glass of champagne. And he said, ‘I would like to show you the toilets.’ Claudio had done the terrazzo in the toilets and he wanted to show me on our romantic date.

Claudio continues.

The architect that I usually worked with would call me to quote on the jobs. One day he called with a big job. It was for Parliament House in Canberra and our quote for $3.1 million was accepted. Then we dealt directly with Canberra for the three-year contract. I felt great when we got that contract. It was a lot of money but a job like that has prestige.

We did terrazzo stairs and landings in different parts of the building, including landscape areas. I planned and supervised the manufacture of the panels in Thornbury and we sent a team of stonemasons and labourers to work in Canberra. I appointed one of my top men as the foreman there.

We also laid Carrara marble as a sub-contractor for Melocco Pty Ltd. There is a big mountain in Italy, called Carrara Mountain. It is all white and made of marble. They cut the marble and slice and polish it and send it all over the world.

There were many trips to Canberra, two or three times a month for three and a half years. When the job was done, we received many compliments for our work. It was hard work and everything had to be spot on. But we did it well and that helped to build our reputation and grow the business.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 25

You have to work hard

You have to work hard

Lyn spoke about a visit to Parliament House in 2017. We had a private tour and an archivist interviewed Claudio for 45 minutes. She said that Parliament House was like the Olympics of artisans. They only chose the very best. The architect was Italian and every part of the project was meticulously researched.

Claudio finishes:

Angela and I gave the business to our son. We also helped our daughters with their mortgages, to make everything equal. I can’t take it with me.

It is good remembering the things you did to provide for yourself and the family. Family will always be family. The more satisfaction you give to the family, the more satisfaction you get back.

Pictured below, Claudio tells the story about painting golf balls.

26 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Scan to watch video

Family means a lot

I met Angela at a dancing hall in Melbourne. She was with a friend and I was with a friend. We sat down and started chatting and started liking each other. Everything is written. She was born in Italy and came here with her family. Australia was a good country for migrants. She grew up in Shepparton, but had moved to Melbourne to work. In my opinion if you have the deposit for a house, you should put the deposit on a house and pay it off. It might take 30 years, but in 30 years you have something. If you pay rent, then after 30 years you have nothing.

Angela and I got married and bought a weatherboard house at 74 Pender Street, Thornbury in the mid-1950s. It was on a quarteracre block on the high end of the street and had beautiful city views. We subdivided the block.

We were naturalised in 1959. If you migrate to a new nation, you have to join the club and become a citizen. I didn’t want to go back to Italy. I like Australia.

We have three children, one boy and two girls. Being a father is good because your family expands. And if you have a boy, you think now the Sabbatini name will continue for another generation. Then we had two girls and I was happy with my family and didn’t need any more.

I didn’t see a lot of my father because he was working and I didn’t see a lot of my children because I was working. I worked on Saturdays too. My ex-wife Angela basically raised the children. She was a good organiser.

On Sundays we might go for a walk together, get ice-creams and have a chat and a laugh. In the evenings we would talk about what everyone did during the day and how they were going. We had good conversations, but there comes a time when the kids want to be doing other things, not talking to the old man.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 27

28 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Family means a lot

Isabelle recalls an amusing incident when she was about ten years old. She sat at what she described as their meagre family bookshelf and pulled out two illustrated books. They were The Joy of Sex and Dante Alighieri’s Inferno. She looked at the pictures for a long time, until she felt a shadow looming over her. Claudio was standing there. He didn’t utter a word, but she knew what the body language meant. She handed back the books.

Claudio continues:

My mother used to say the normal things that mothers say, ‘Don’t do this. Don’t do that.’ As a father I did the same. I would call the family together to get things done and I had high standards. I wanted to show my children how to have a good life. When they were very young, I told them to be careful, to socialise with friends, to choose good friends and not to be led astray, and normal things like that. As they grew up, I was known to say that you can’t take it with you so you might as well enjoy it; that when one door closes, another door opens; and that life is written.

We didn’t have a lot of money to go out in the early days. Even though I was making good money, a lot of it was tied up in the business. Sometimes we celebrated birthdays with family and friends. Everyone came for dinner and Angela would make a cake. Angela made all sorts of cakes, including baked ricotta cakes and everything. I liked all the cakes and I always liked to have the last piece. I still have a sweet tooth.

Then we moved to 9 Conifer Place, Lower Templestowe from about 1971. We built a large house on a hill. An architect designed the house with our input. It was interesting to have a house designed to suit us. We used subcontractors to do most of the work. I did all the concrete for the foundation, floors and pavements. There was a square, sunken bath. I think it was Carrara marble. Sharon liked being closer to horse-riding. We stayed there for about twenty years. After I retired, we moved to twenty acres at Hurstbridge. The house had bullnose verandahs.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 29

Pictured left, from top, Claudio, Angela and Bruno; Claudio with frontend loader at Lancefield.

Family means a lot

We went to the Mornington peninsula with other families for summer holidays. At first, we rented a small house. In the late 1960s we built, with another family, two units at Christopher Court in Rye, from bits and pieces.

Claudio was very resourceful and the family joked about his ability to find things. He loved kerbside collections and on one occasion retrieved a painting from a house that was to be demolished.

We swam at Anthony’s Nose at Dromana. We went water-skiing and fishing and played golf. We built a bigger holiday house on one acre at Bella Vista Drive, Tootgarook around 1980. That is where I live now. I moved here after the divorce.

In the 1970s we also had a hobby farm at Lancefield. Angela grew up on a farm and she liked it, so we had about 200 acres at Lancefield in partnership with another family. It was very rural and isolated. We kept Hereford and Black Angus cows to keep the grass down. Angela liked the cows and she knew what to do on a farm. I liked to be a mechanic because that was what I trained for. We went to Lancefield on some weekends and I did the digging and building fences and heavy jobs. The children picked up rocks and helped to clear the land for cultivation.

Isabelle remembers a childhood of incredible experiences. There were always lots of friends and family of all generations around. The children had fun days at the beach. When three or four families joined fishing trips at night, using nets, they enjoyed a sense of cultural tradition. As teenagers they were introduced to ski resorts. Above all, they were blessed with considerable freedom: at the beach, in parks and on the farm, and able to grow very naturally. Isabelle sees that as characteristic of her parents and probably of Claudio’s own upbringing.

Claudio continues:

Having children improves your life. All the children improved my life. When my children got married, I felt lucky and happy to have the family united with a new family. I said to my children, ‘Enjoy your life, and come and see me when you have time.’

30 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Family means a lot

Now I also have five grandchildren so the Sabbatini name will expand further. Bruno has three boys and Isabelle has a boy and a girl. Family means a lot. It is part of life and when you have a family, you have to support them. I did my best to make a good life for the family, by working hard.

My mother died in 1979 at 74 years of age. A mother is a mother. When your mother dies it is a very big loss to any son or daughter. But you can’t do anything about it. The only good thing was that she didn’t suffer. She just died quickly at home from a heart attack. It is worse if you have to suffer in pain for months or years. I have said to Lyn many times, ‘I would rather die from a heart attack.’

Claudio’s grandson, Rick, wrote about his memories of Nonno Claudio.

From the looks of any photo of us with Nonno in the 1990s, he’s perpetually riding a tractor or a mower, with Max or me balanced between his knees. He’d have us take the wheel while he looked on with an air of amused satisfaction, his leathery work-worn hands resting on his thighs, steady, at ease. When I see photos of him from his younger days, he’s always lifting, chopping, incinerating, hauling something he’s shot or reeled in.

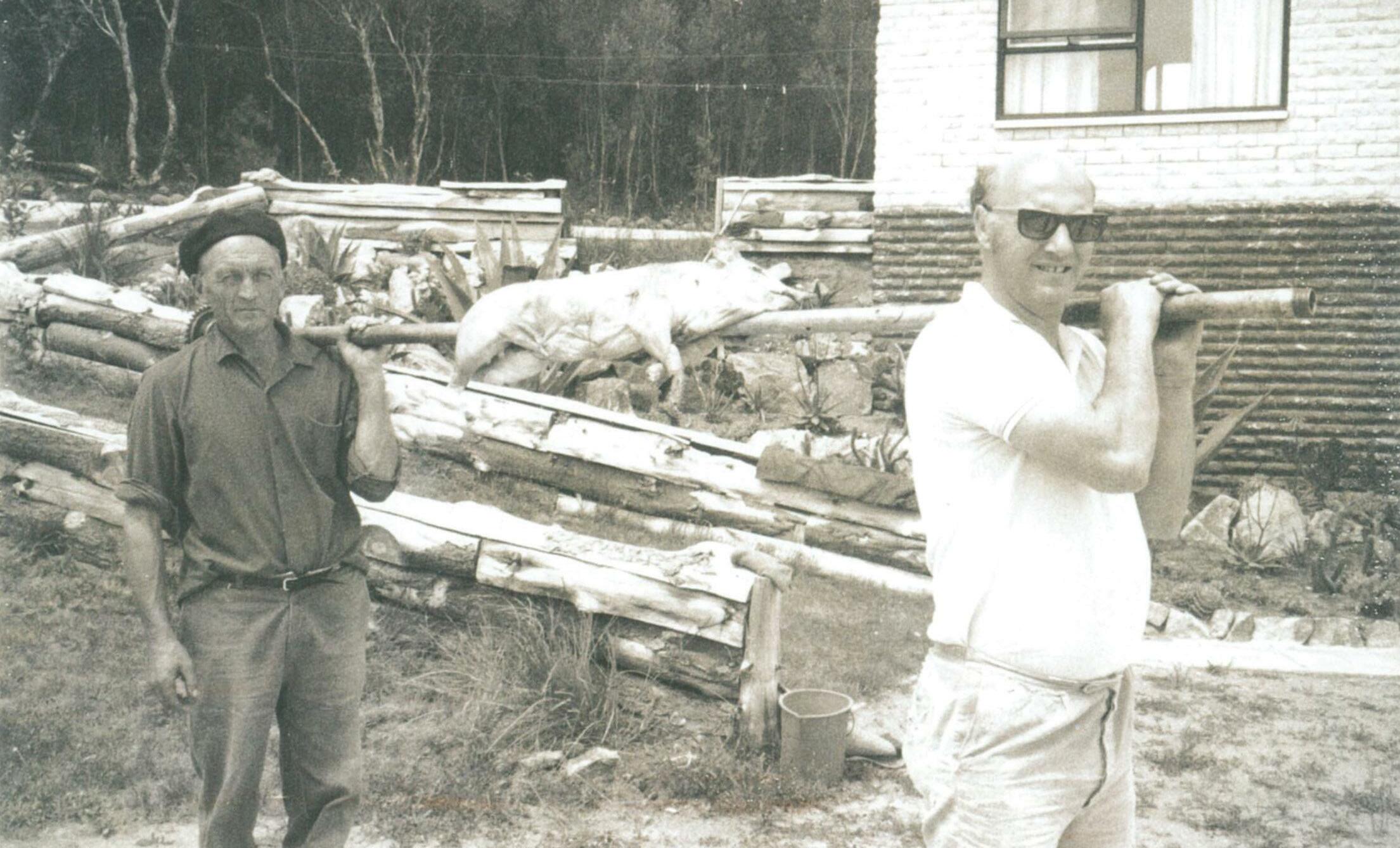

It seemed like every other year he was building a house from the ground up. Sometimes I see his bricklayer mate Peter in the frame, the signature beret perched artisanally. I was up in Wodonga recently, driving past the Bonegilla migrant centre where Nonno stayed when he first arrived in Australia all those years ago. The food was apparently so bland that the Italians rioted.

Nonno told me that one of the first things he did was go and buy a .22 so he could shoot rabbits and live off them instead of tinned bully beef. That seems like a very Italian manner of doing things, something I strive to emulate in my own way.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 31

Family means a lot

I imagine him crouching over a small campfire at dusk, cooking spindly rabbits for dinner along the rail works in the middle of nowhere, far from the ancient stone city of Trieste. Far from the ruins.

Claudio’s grandson, Max, wrote about one of Claudio’s ongoing jokes.

When I was a child, Dad used to take Rick, Jack and I to visit Nonno at his house on the hill in Tootgarook.

Nonno had a classic stunt that he liked to pull. He’d walk down from the house to greet us, and as the car emerged from ascending the steep driveway he’d stiffen his legs, boggle his eyes and protrude his dentures out through his lips like the horrible pharyngeal jaws of an eel. He’d grunt and groan like a zombie for added effect. It never failed to elicit hysteria in my siblings and me.

On one occasion it wasn’t until the end of our visit that we realised the denture trick hadn’t made an appearance. We stood beside the car about to leave.

‘Hey Nonno, can you do the teeth-thing?’

He became slightly serious, even a little dismissive of the idea.

‘No, my teeth are real now. So I can’t pop them out anymore.’

We were a little disappointed but accepted his explanation. We said our goodbyes and hopped in the car. As we mounted the steep driveway we turned back to wave and found Nonno trudging stiff-legged behind the car, his eyes boggling wildly and his dentures protruding from his mouth. We were practically paralysed with laughter.

32 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Pictured right, from top, the house at Templestowe; Peter and Claudio preparing a spit at Christopher Court, Rye; Claudio with Rick and Max at Hurstbridge 1995.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 33

34 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Enjoy life

I didn’t ski in Italy. We couldn’t afford it. I started skiing in Australia when I was young, before we had the children. When the children were older, I introduced them to skiing, and I skied again with Angela and our friends. I love skiing. It’s good when you slalom.

But skiing is dangerous and the older you get, the more dangerous it is if you fall down. When I was in my fifties we went out and the snow was very icy. At that time, we had no protection. That was when I decided not to ski again. I said, ‘No, I would like to live longer’. Which I’m still doing.

When I had a boat, I used to go water-skiing. It’s beautiful. I loved water-skiing especially when you go like this (sideways movement and noises) and then…(tumbling action). At least when you fall you don’t hurt yourself in the water. When you are young, you can do good things. You can afford it physically.

My friend Robbie and I zig-zagged each other when we were water-skiing, crossing over each other’s ropes. One time we had an accident. When you’re young you do stupid things. Like the hand grenade. In life everything is written from the day you are born, to the day you die.

Claudio has lived large and lived fully, although he often expresses a harsh view of his younger self. He also enjoyed golf, squash, tennis and pistol shooting. I liked the competition in pistol shooting. Someone would call ‘Pull!’ (Claudio makes the noise of a moving clay pigeon) and you had to be quick because it could go anywhere. Then you would shoot, and celebrate if you thought it was a good shot.

I used to have hunting holidays with a group of friends, including John, Robbie, Venancio and Gabe. We went to Ivanhoe in New South Wales or to Princess Charlotte Bay on Cape York in Queensland. It was rugged bush. We would set up a big campsite and hunt for rabbits, ducks, quail and pigs. We took boats to go fishing.

Above, watch Claudio talk about clay shooting.

Pictured left, from top, Claudio on a hunting trip; Claudio shot a deer in New Zealand.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 35

Scan to watch video

Enjoy life

There was great camaraderie between Claudio and his male friends. Claudio says that, if he was out with the boys, he always had to watch out because the friends were always playing pranks on each other. Lyn remembers how they loved to see each other and shared many laughs. She talks to John, one of Claudio’s friends who joined him on hunting trips. John laughs a lot as he speaks affectionately about Claudio.

He was the one we had to watch out for because of his pranks. Claudio was always up to tricks. He was a menace.

One time, after we had been hunting wild pigs, I was in my sleeping bag in the back of an enclosed ute, because I was scared of the pigs. Claudio shut me in the back, then he got in the cabin and drove around, bumping me up and down. He was mad!

We used to set up a shower arrangement under a tree. But once, at Cape York, Claudio secretly rigged it with gelignite from his work. I was enjoying a shower when he detonated it with a battery-operated control. I was completely covered in the sand that exploded around me. On those trips Claudio lost all his manners! But he was a good fella!

Claudio no longer remembers these pranks, but the stories appeal to his sense of humour.

One time I went to New Zealand for a hunting holiday, and stayed at an isolated farm on the South Island. It was so remote that they used a helicopter to get to the shops at Dunedin. I went up and down the hills for ten days looking for a deer. I couldn’t find a deer. I found one on the last day and it took me all day but I finally got it. We cut the meat from the body to cook and we took the head off and I brought it home on the plane. You couldn’t do it now. I was young and stupid. I wouldn’t do it now. The deer’s head is mounted on the wall in my house at Tootgarook.

Social activities were characterised by a strong Italian flavour and community.

36 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Enjoy life

My company contributed money to help build the Veneto Club in Bulleen. I had plenty of money then because I was in business. It opened in 1973 and all the Italians used to congregate at the Veneto Club. It was a place to talk. There was a lot of chatting.

Angela and I spent a lot of time there. The men would sit around a table chatting and playing cards while the women would talk to each other about different things. We played cards, talked with each other and made lifelong friends. I had hunting holidays with some of the men.

We had fun telling each other off. I enjoyed the conversation, the company, the humour and talking to each other about life. It was nice. I like to hear about somebody’s life and the things they have done.

Later, Lyn was particularly struck by the Italian spirit and attitude to music.

Claudio belonged to the Italian Club at Rye. We used to go there for New Year’s Eve every year. There was so much food. The entree would have been enough. There were prawns and salad and big rockmelon and prosciutto. Pasta came next. Then a roast meal, chicken with vegetables and salad. Then dessert.

Claudio chuckles, ‘Too much’, before Lyn continues.

The Italian spirit is amazing. About 200 people attended every New Year’s Eve. In an Australian environment people were usually hesitant to dance until there were several couples on the dance floor. But twenty years ago, these Italian people were in their sixties, seventies and eighties, and as soon as the band picked up their instruments and played the first chord, everyone got up and filled the dance floor.

Quite a few of the women were opera trained. Suddenly the people at one table would start to sing. Or Etta might stand up and everyone would join in. Then there would be a little break before the people at another table started to sing, in between the band’s sets.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 37

Enjoy life

It was like something from a movie, with all this beautiful singing and wonderful operatic arias. That happened every year.

The men were beautiful dancers. Everyone would still be kicking their heels up at midnight.

And we used to play cards with a group of friends at different houses. Even playing cards, between deals, someone would start singing Ave Maria for example.

Claudio interjects, ‘Enjoy life’.

Claudio loved to sing. One beautiful October day the water sparkled as we got on the ferry at Sorrento with another couple. We were the only ones on the top deck and Claudio started singing Sorrento (Torna a Surriento, Come Back to Sorrento). It was like something out of an Elvis Presley movie.

Prompted by Lyn, Claudio sings Sorrento. He is strong, confident and expressive. Then he continues:

It is good to play an instrument. I used to play guitar. it is beautiful. I loved it but I can’t play anymore. My finger is stuck.

He points to the little finger on his left hand. It has been stuck in a 90-degree bent position for at least twenty years.

It just happened. It was not an accident. I can only wash my face with the other hand. With this hand I would stick the finger in my eye. But I can do everything else. I can do anything.

He strokes Lyn’s hair.

Pictured right, from top, Claudio and his friends set up large campsites for their hunting holidays; Claudio contributed money towards building the Veneto Club in Bulleen.

38 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 39

40 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

She’s a good helper

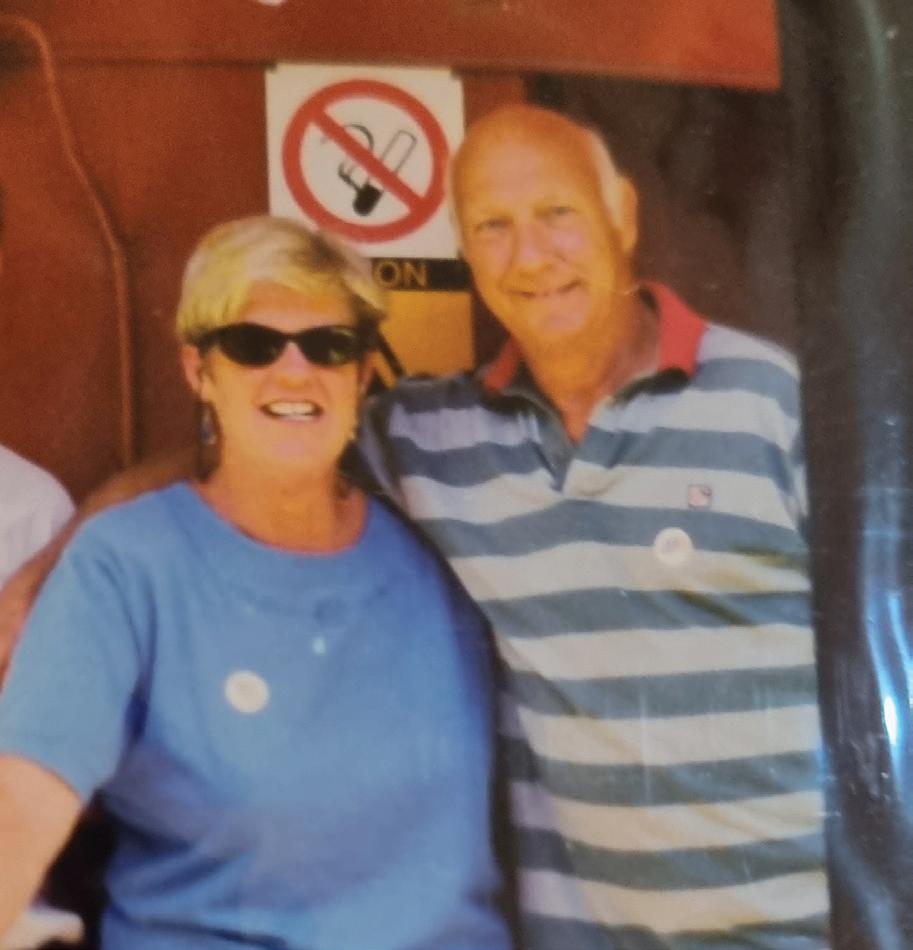

When asked how he met Lyn, Claudio starts to talk about an earlier cruise he took with another lady. Lyn has a quick sense of humour. She laughs heartily and takes up the story. In 2000 she went on a safari trip to Cairns with her friend Ellen. Their fellow travellers were mostly couples.

When I saw Claudio, I said to Ellen, ‘Have a look at this bloke. He’s a bit of alright. I wonder where his missus is.’ He had big blue eyes.

It was obvious there were some sparks flying. As we sat around a campfire in the evening Claudio would gesture to me to go for a walk. I always asked Ellen to come with us.

At the end of the trip I said to Claudio, ‘It’s lovely, but you’re too old and you live too far away.’ He is 21 years older than me. I had just come out of a long-distance relationship and I didn’t want to do that again. I just said, ‘Goodbye.’ Perhaps not quite like that.

They stayed in touch, despite some confusion and strained conversations.

In May 2001 I planned a trip from Wodonga to Melbourne with another friend. When it fell through, I decided to call Claudio.

He gave me a lovely weekend. We went dining and dancing on the Saturday night, and on Sunday we went to the Portsea Pub for lunch, then walked on the beach. He’s never walked on the beach with me since. I came back the next weekend, just to check if it was really that good.

Claudio interjects, ‘To find out if she was dreaming.’

Lyn still had doubts about their age difference. Pressed for an honest opinion, her friend Ellen also thought Claudio was too old.

The long-distance relationship continued for six years while Lyn worked full-time as assistant principal at Baranduda Primary School, near Wodonga. She sometimes came to Tootgarook in the holidays and Claudio came to her during the term.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 41

Pictured left, from top, Claudio and Lyn in Egypt 2008; Lyn and Claudio met on a safari trip in 2000; Lyn and Claudio in Canada 2015.

Lyn emphasises Claudio’s generosity.

Some gifts were practical: the dishwasher because he didn’t like to do dishes; the bigger heater because mine was too small; the skylight because the kitchen was too dark; and the Nissan X-trail because my Ford Falcon XR6 was too low to be comfortable for his tall frame in his seventies.

Other gifts were romantic, like the Tahitian black pearl on a gold chain that Claudio gave me for my 50th birthday. When I needed to shorten the chain, Claudio asked me to keep the extra piece. It was the chain his mother gave him when he left Italy.

After Claudio was diagnosed with dementia in 2006, I resigned from my full-time job and did casual relief teaching (CRT). In Wodonga I came home every lunch time and sometimes took Claudio back to school with me. He did lots of jobs to help around the school.

After a school excursion to Bonegilla, Claudio gave talks to the children. They were spellbound by the imposing man with an accent who had lived in those conditions.

When we were at Tootgarook, I did CRT at Sorrento Primary School. Eventually that became too far away from Claudio. In June 2018, I stopped teaching and came to Tootgarook permanently.

Claudio thanks Lyn for her assistance.

She’s a good helper and a lovely lady. Lyn is very beautiful for looking after me. She is a good companion and I like her sense of humour.

42 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

She’s a good helper

A good life

We went to Egypt in 2008 and stopped over in Abu Dhabi for a few days with friends. I’ve always been interested in ancient things. And it’s amazing. It’s all desert but at the same time it’s very attractive. And how did they build the pyramids? They didn’t have cranes. How did they get the stones up to the top? Apart from that, where did they get the stone from? It’s amazing.

Claudio and Lyn have travelled. There was a Rhine Danube tour in 2010. A trip to Italy with Lyn’s cousin in 2012 included a few days in Trieste. Lyn had a reunion in Canada in 2015, so they travelled with two of Lyn’s friends for two weeks. A Kimberley trip in 2017 included a cruise from Darwin to Broome. They have seen many places in Australia. Claudio sums it up:

A good life.

Travel was curtailed from 2020.

During the COVID lockdowns we walked around the block and in the garden.

Lyn tells more about their lockdown experience.

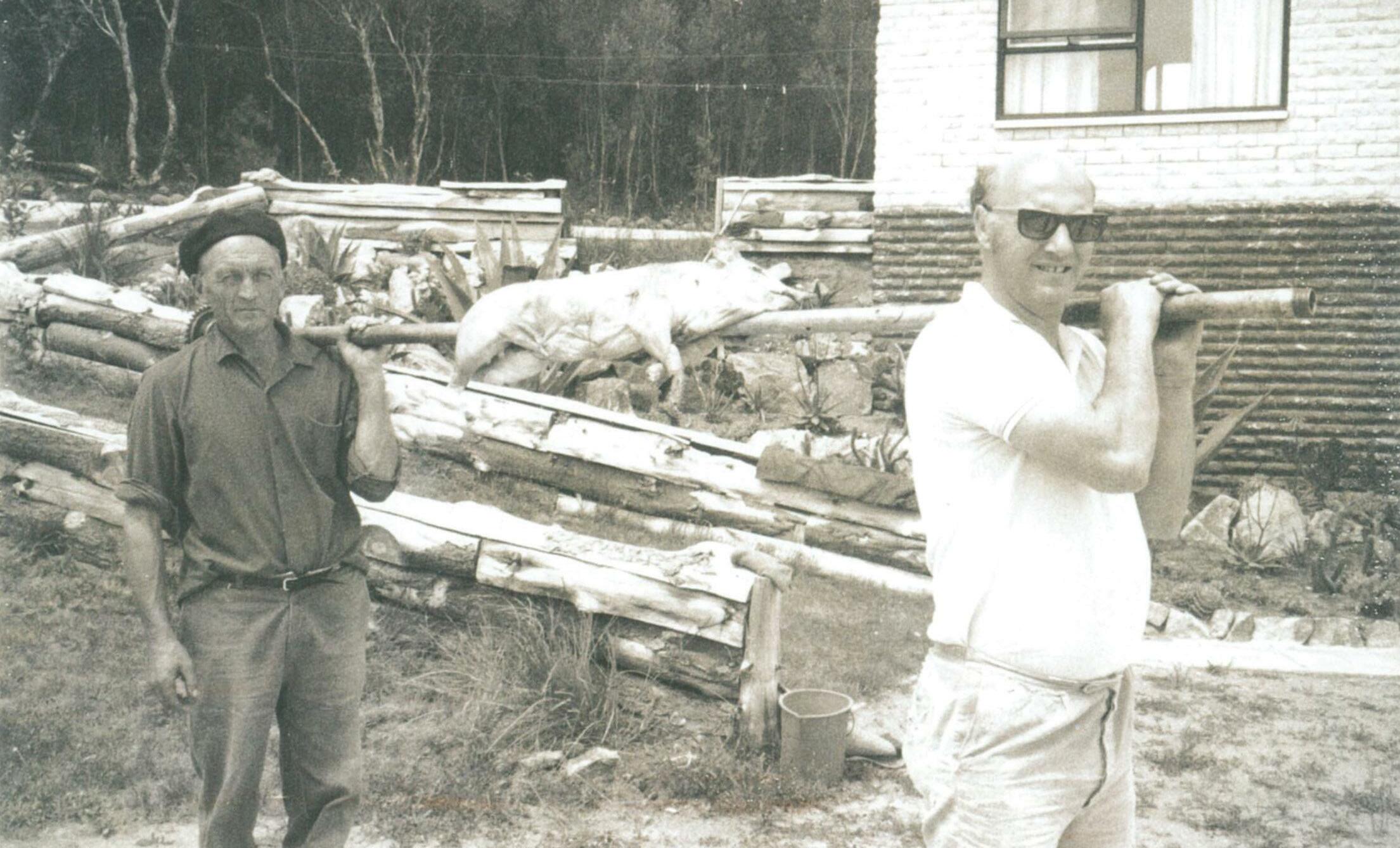

Living on one acre saved us. I asked our neighbour, Michael, to help me cut down two dead trees. That expanded into a huge project. We were outside for several hours every day for two and a half months, and cleared a large area. Between us, we cut down and dragged trees, cut and stacked firewood, and Claudio mulched the rest.

A landscaper offered us a trolley that goes on the back of the ride-on mower. That made everything so much easier. The project kept us sane, busy and active.

Another activity was stimulating and helped us to stay connected to people. My Italian class stopped during the lockdowns. But a group of us continued to work together, with Claudio as our guide. We mostly met on Zoom, and visited each other’s houses when we were allowed to. Claudio was a great help to all of us and my friends still talk about how grateful they are for that experience.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 43

A good life

Lyn planned a series of events to celebrate Claudio’s ninetieth birthday in October 2022.

The first was to be with my family and we booked a house at Daylesford. However, floods prevented people from getting there, so the event was postponed until February 2023 and will happen soon.

On Claudio’s birthday, we celebrated with family at Kirks on the Esplanade, in Mornington. There were about thirty people. Two weeks later, thirteen friends came for a catered dinner at Tootgarook, with many staying over for a few days. A few weeks later, we stayed at a house in Marysville with four friends we met on the Rhine Danube cruise. Every year the group meets for a week together, in a house or on a houseboat.

My friend Ellen wrote a poem for Claudio’s ninetieth birthday. One of the verses was:

‘I said he was too old. I said he was too old.

Then I realised he is not that old.’

Claudio’s shed is approximately 800 square feet of man-cave heaven. At one time it included a lathe and a stack, approximately five feet high of Lazy Susan trays divided into sectors for different components. It still has the block and tackle he used for his boat, and a comfortable chair he calls his throne. A plain modern wardrobe from Lyn’s old house blends with decorative old cabinets and desks. Dozens of small, old tin filing drawers are stacked neatly on desks, each tin meticulously labelled. Now, as Claudio’s memory fades, it might take twenty minutes to find something but he still knows exactly what

is in here.

44 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Pictured right, from top, Claudio at a pyramid in Egypt 2008; Claudio revisits a former apartment building at 7A via della Risorta, Trieste in 2012; Claudio mulching at Tootgarook; Claudio and family at his 90th birthday 2022 (one grandson absent); meticulous organisation in Claudio’s shed.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 45

46 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Reflections

Dementia

I cannot understand why they said to me, ‘Now you have dementia.’ To me, I remember almost everything. I don’t know why they reckon I’ve got dementia.

Lyn tells Claudio that his short-term memory is affected and he doesn’t always remember what happened five minutes ago.

Oh yeah, that’s true. But I thought that was a normal thing as you get older. I remember significant things that you don’t take for granted. Did you have breakfast? Yes. Did you have a cup of tea? Yes. Did you get out of bed? I don’t remember. Getting older is terrible.

I don’t like having dementia but I can’t help it. Even the doctor says as you get to my age you get dementia because your brain is overworked.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 47

Pictured left, from top, Claudio at Tootgarook January 2023; undeterred by weather Claudio is ready to walk for newspaper and icecream.

Reflections Happiness

Claudio walks to the shop most mornings to buy the paper and an ice-cream. He is not deterred by inclement weather, and enjoys the ice-cream before breakfast.

When asked about happy events in his life Claudio talks about the contentment found in everyday life.

Be happy your whole life. Living is a good thing. Be happy doing what you are doing, and that encourages life.

I’m happy with my life. Absolutely. I have a good lady to look after me.

The only thing I wish for myself is to stay fit and healthy the way I am, and after that, in ten years I might get a letter from someone in England to say, ‘Happy 100 years sir!’ And I want my children around to say ‘Happy birthday, old man.’ It will be a big party. I can have a drink for that party. Enjoy life. I wish for the people that I love to maintain their health, well enough to look after me!

He jokingly tells Lyn not to hit him.

I’m very lucky that I met a lovely lady like Lyn. There were many times that I was excited: when I got my scholarship at school, when I got my apprenticeship, and after that when I became a tradesman.

Lyn explains that Claudio is quite emotional.

He cries if he watches a sad movie. But when he talks, he sees things from a purely pragmatic point of view. He doesn’t discuss emotions.

48 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man

Reflections Know of my dreams

I would like people to know of my dreams. Coming to Australia was the most important thing. In Italy you work, but you don’t get enough money to survive. I couldn’t see a future there for me. We struggled.

When you want to know about a person’s life, find out what he was doing, whether he likes that, what he likes to do, and get more involved in their personal life. People always like to find out from me what I was doing and what I like and so forth. I’ve had a hard life but I got a good life. I like it. I’ve got a beautiful lady to look after me.

I’m lucky that I migrated to Australia. Life is pretty hard to explain. You find people that have good lives, people that have bad lives, some people have medium lives. But the life that you have is only a personal life the way that you make it. In my opinion, I could be wrong, if you do your best in every part of life, you will have a better future. I’m very happy with where I am now. You make the best of what you’ve got. It is all written.

Claudio’s attitude to life is positive and inspiring. Is there a contradiction between life being as you make it and as it is written? I seek clarification. Is it about doing your best but accepting the things you can’t control? No. Does it mean we can’t control what happens to us, but we can control how we respond? No, it is difficult to explain.

We go around in circles until I understand that Claudio is comfortable with duality. The two ideas are so self-evident as to defy explanation.

Make the best of your life.

Life is written.

Life is Written: the story of a lucky man 49

Notes

We had a good life

– In Trieste, Claudio’s family lived at Via del Bosco, Via Risorta and Via della Madonnina.

War is shocking

Trieste bombing, 10 June 1944, https://ilpiccolo.gelocal.it/trieste/cronaca/2014/06/14/ news/cosi-il-10-giugno-44-trieste-si-sveglio-sotto-le-bombe-1.9423562

– New Zealand soldiers liberated the city in 1945, https://www.smh.com.au/national/atragic-history-that-brought-thousands-of-triestini-to-australia-20120325-1vsib.html.

Gianfranco Cresciani, Trieste goes to Australia, Gianfranco Cresciani (Lindfield NSW: 2011). Difficult to read with eight-line sentences and page-length paragraphs.

– www.britannica.com

There was no future in Italy

– There is a five-storey Fiat building in Turin, with a race-track on the roof.

The Australia, Oceania and Neptunia were Italian liners built at Cantieri Reuniti dell’Adriatico Shipyards for Lloyd Triestino Lines. They were launched in 1950 and 1951. http://ssmaritime. com/MS-Australia-and-Sisters.htm

– Museums Victoria has an article about the three ships. https://museumsvictoria.com.au/ article/the-lloyd-triestino-trio/

Leonilda arrived on the Oceania in July 1954 when Claudio lived at 106 Flinders Street, Thornbury. NAA: K269, 4 Jul 1954 Oceania, Incoming passenger list to Fremantle, page 12 of 30. https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au

– ‘Migrants taken to quarantine’, The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 21 Mar 1952, 3, https://trove.nla. gov.au/newspaper/article/248744851

‘50 quarantined at Woodman’s’, Sunday Times (Perth), 23 Mar 1952, 1, https://trove.nla.gov. au/newspaper/article/59542517

– ‘Wharf tangle over quarantine plan’, The Age (Melbourne), 29 Mar 1952, 4, https://trove.nla. gov.au/newspaper/article/206209901

‘Foot and mouth disease’, The Herald (Melbourne), 29 Mar 1952, 1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/ newspaper/article/246047223

– Index Card, NAA A2571, Sabbatini Claudio, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/

Luigi Sabbatini from Trieste, born 17 Apr 1932, was also on the Sydney, but Claudio did not know him and said he is not related.

We learned about life and how to survive

Bonegilla opened to assisted immigrants in 1947.

– Short video about Bonegilla, https://dl.nfsa.gov.au/module/1599/

‘Riot alert Bonegilla’, The Argus (Melbourne) 19 Jul 1952, 1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/ newspaper/article/23185723

– ‘Willbriggie block’, The Murrumbidgee Irrigator (Leeton, NSW), 29 Jun 1926, 6, https://trove.nla. gov.au/newspaper/article/155884956

You have to work hard

Email received 27 January 2023 from Denyl Cloughley, Director, Design Integrity and Special Collections Unit, Department of Parliamentary Services.

Family means a lot

Certificates of Naturalization, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 25 Jun 1959 (Issue No. 37), page 2237, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/240999380/25981285

– Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, Leonilda Sabbatini, death certificate index, 26853/1979.

Includes information supplied by family members.

– Templestowe Cemetery, Clay Beam section, row C, grave 8, Leonilda Sabbatini https://www. gmct.com.au/deceased/3118061

Enjoy life

– The Veneto Club opened in 1973, https://www.venetoclubmelbourne.com.au/history

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

50 Life is Written: the story of a lucky man