The Murillo Bulletin

Journal of PHIMCOS

The Philippine Map Collectors Society

Basilan Special Issue October 2025

The Philippine Map Collectors Society

Basilan Special Issue October 2025

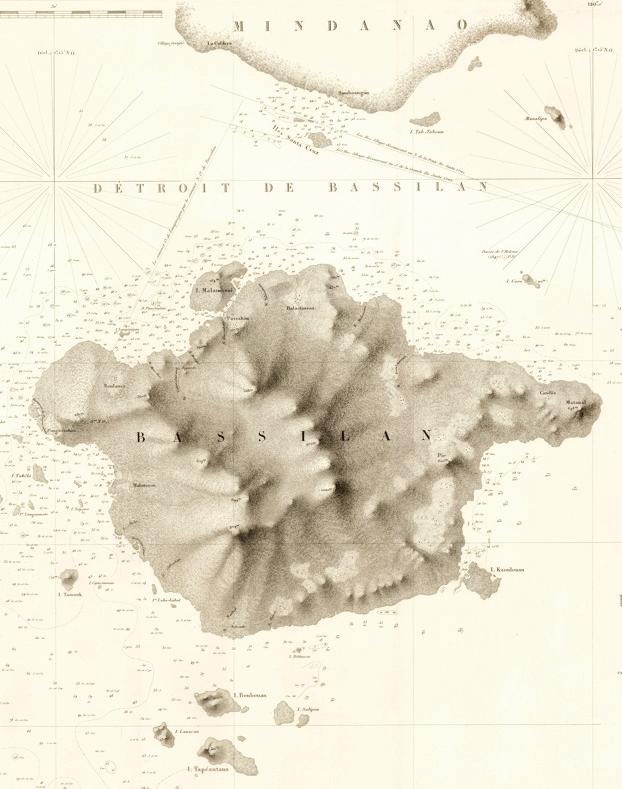

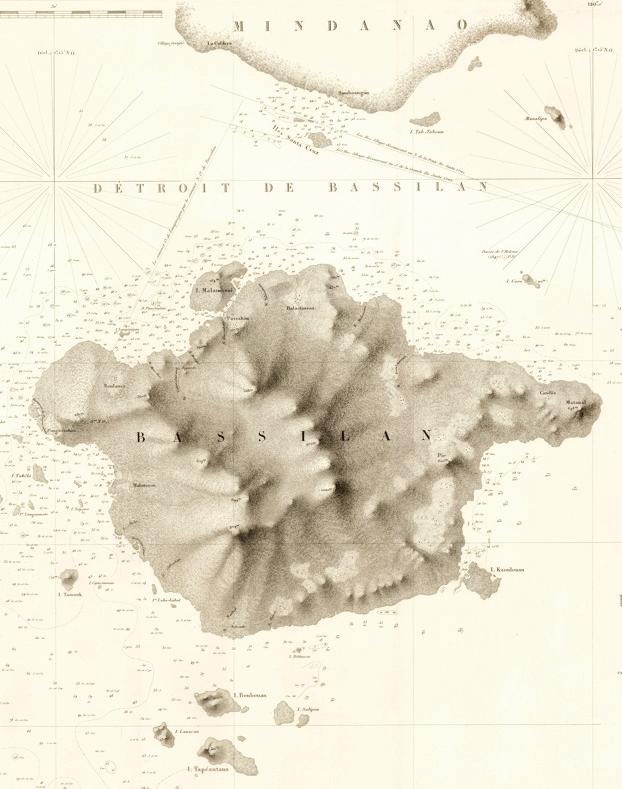

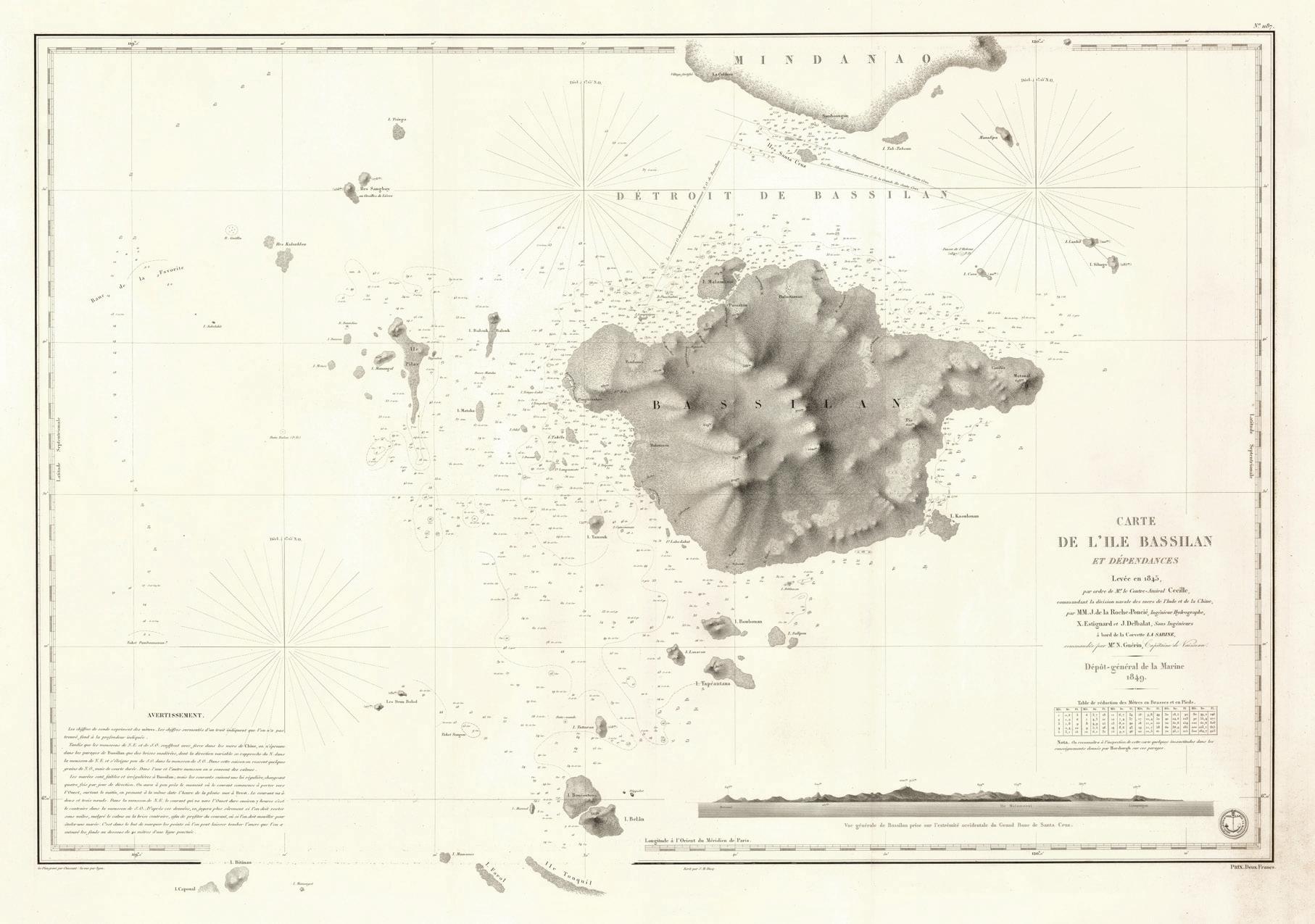

Front Cover: Detail of Basilan from Carte de l’Ile Bassilan et Dépendances Levée en 1845 Dépôt -général de la Marine, Paris, 1849 (image courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps)

It is with profound gratitude and honor that I extend my warmest greetings to the Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS) and the readers of The Murillo Bulletin. This publication is more than a journal, it is a vessel of memory, a repository of heritage, and a celebration of the narratives that maps so vividly preserve.

Maps are not only geographical tools, but also testimonies of identity, heritage, and human experience. They tell us where we have been, what we have endured, and the countless possibilities that lie before us.

Basilan’s cartographic journey is deeply interwoven with the Austronesian maritime heritage. Long before European cartographers traced our islands onto their maps, our ancestors were already skilled navigators of seas and winds, guided by the stars, the tides, and indigenous spatial knowledge passed down through generations. This legacy lives on in the identity of the peoples of Basilan – communities who have always understood that to journey across waters is to connect, to trade, to share, and to survive.

The Tagima Quincentennial Historical Marker reminds us of Basilan’s place in the larger narrative of global encounters and exchanges. It af�irms that our island was not on the periphery of history, but at its very crossroads. It was here that worlds met – seafaring traditions, cultural exchanges, and encounters that shaped both local and global destinies.

Through PHIMCOS and The Murillo Bulletin, this story of Basilan through the maps, a �irst of its kind, is of utmost importance to us. It �inds resonance beyond our shores. It con�irms what we have always known but found limited evidence – that we played a remarkable role in the world, a role we seek to reclaim.

Mabuhay ang PHIMCOS! Mabuhay ang ating kasaysayan at kultura!

MUJIV S. HATAMAN Governor

“Indigenous” is a word thrown around a lot. Used to denote a sense of being “native”, of being almost endemic. Though its de�inition has been muddled in this country to imply a sense of inferiority or even somehow being deserving of pity, the word indigenous is most often associated with a people, a language, and an identity.

What I would like to focus on, however, is on the other aspect of “indigenous”. That of place. This word is also especially equipped, possibly more than any other that comes to mind, in tying people to a place.

It is this connection between people and place, between soul and soil, that is so dear to our people. In the long story of Mindanao, and the struggle of the Moro people, regardless of the complexities, we always return to the land and our connection to it. We are born on it, sustain ourselves from it, and eventually return to it.

As such, this showcase of the history of Basilan through historical maps over the decades and centuries, cannot be overstated in its importance. Whilst some may see crude drawings, not nearly as accurate as today’s satellite imaging, those who understand the connection between land and people can appreciate the true value behind this great work.

Much like seeing a loved one during their younger days ‒ before you have had the opportunity to meet them, seeing depictions of Basilan stirs all sorts of complicated feelings, from a kind of melancholy to a poignant sort of happiness. It is a mixture of seeing an island so different from how we know Basilan today, and yet, all the same, recognizing home.

Having this collection of illustrations of Basilan as well as their accompanying descriptions also provides the unique opportunity to read and understand our beloved province from the eyes of its visitors through the centuries, through travelers and settlers taking the time to document the island. With the turbulent recent history only decades ago characterized by con�lict, it is refreshing as a native of Basilan to be able to read on perspectives about the island from a time even before the era of infamy we seem to have been cursed with and today strive so hard to continue to leave behind.

Above all, however, the maps, simple as they may seem, give us a powerful and wonderful reminder: that our island and our people have existed long before us, and ‒ God-willing ‒ will exist long after us. It won’t be long before our stories and narratives join the rest of our ancestors who walked, prayed, and dreamed on this land.

On behalf of Anak Mindanao Foundation, I would like to thank the wonderful people who put this together. By letting us see ourselves in the past, we can continue to hope for the future.

Centuries from now, what “maps” will be made about our humble island? One can only hope that the illustrations to follow show us a province that is happy, contented, and digni�ied.

AHMED IBN DJALIV T. HATAMAN Executive Director

The Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS) is not only a club for collectors of antique maps and prints. We are also committed to informing our members and the public on the importance of cartography in understanding the geography and history of the Philippines, especially those parts of our archipelago that are not as well- known as they deserve to be. Consequently, we were delighted when one of our board members, Felice Noelle Rodrig uez, offered to give us a presentation on ‘The History and Mapping of Basilan and the Basilan Channel’ in collaboration with Peter Geldart, another of our board members.

The presentation was made at the PHIMCOS meeting held on the 13th of November, 2024. Our guests of honor were Mayor Sitti Djalia Turabin Hataman of the City of Isabela and her husband, Congressman Mujiv S. Hataman, who is now the newly- elected Governor of Basilan. Mayor Dadah started the proceedings with a lively and highly personal account of growing up in Isabela, the interesting cultural traditions of her home, and the successful attempts she has made to improve her city and to promote the recent growth and development of Basilan.

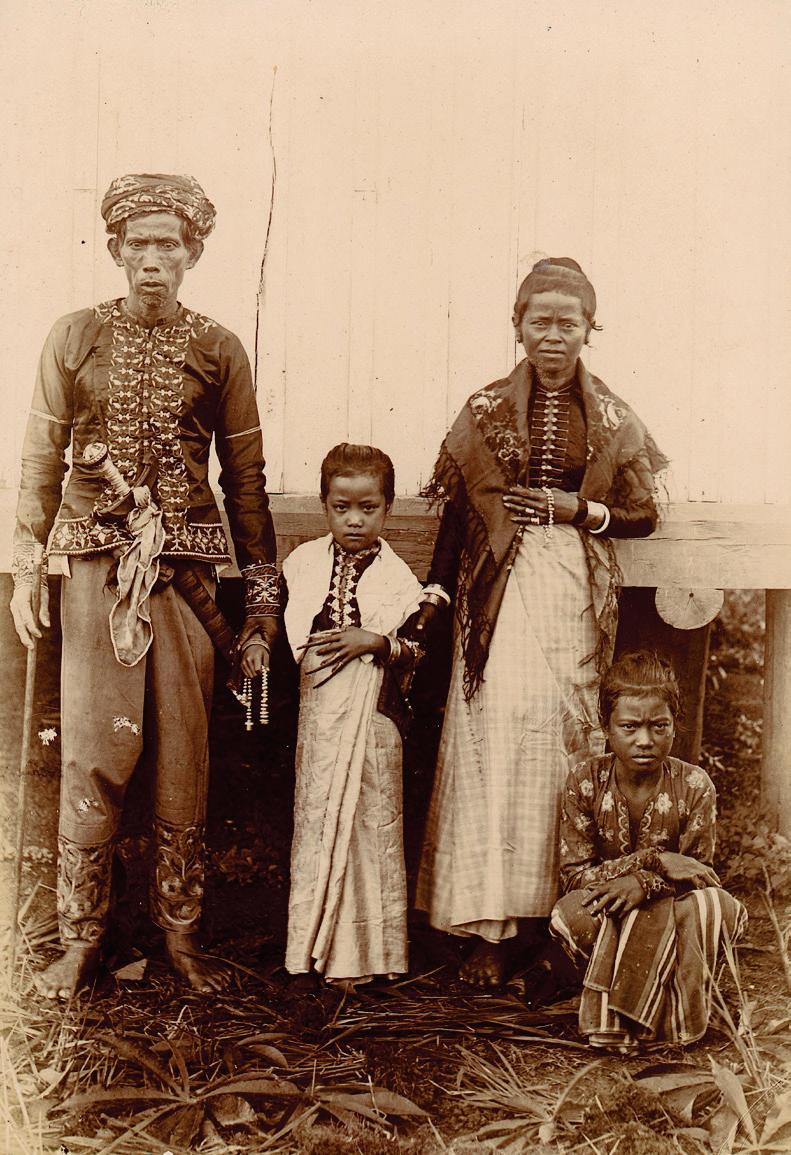

The island has a long and colorful history. The indigenous population of Yakan, Tausug, Sama and Iranun has interacted with European sailors heading to the Spice Islands; the Spanish governors and soldiers in Zamboanga, across the Basilan Channel; the neighboring sultanates of Sulu and Maguindanao; French would- be colonisers; explorers, traders, missionaries, ethnologists and naturalists; American administrators and plantation owners; and Japanese invaders. Sadly, in recent decades Basilan has been severely affected by the atrocities committed by the Abu Sayyaf Group which gave the island a bad reputation as not being safe for visitors.

Today peace has returned to Basilan and the City of Isabela, and Major Dadah has led the political, economic and cultural revival of her home. She has provided generous sponsorship from the City for this special issue of The Murillo Bulletin, and arranged additional sponsorship from the Provincial Government of Basilan, Pahali Malamawi Beach Resort and Anak Mindanao . We thank all of you, and we hope that this publication will make a meaningful contribution to your efforts to allow Basilan to regain its image as the Treasure Island of the Southern Philippines!

Jaime C. González President

Philippine Map Collectors Society

My Basilan

by Mayor Sitti Djalia Turabin Hataman

Magandang gabi po sa ating lahat. Assalamualaikum!

IWISH TO EXPRESS my gratitude to the Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS), headed by Mr. Jimmie González, for the opportunity of getting all of you to know Basilan ‒ my Basilan, and our Basilan!

As we learn about Basilan through maps and historical pictures, please know that we are rediscovering Basilan together. Yes, although I am a Basileña, I know about the history of Basilan only through Wikipedia ‒ not always a reliable source ‒ and from the stories told by my elders. That is why, when I was asked to make a presentation to PHIMCOS, I was apprehensive. But as I told Dr. Felice Noelle Rodriguez, although I cannot talk about Basilan from the perspective of history, I can tell you about Basilan through my own experience. This will help you to put a face on the old maps and relate them to stories about life in Basilan.

I grew up in Basilan, and with hindsight I realize that it really was a life in the community. Much of what I appreciate about Basilan now comes from having had the opportunity of being raised not just by my immediate family but by the whole community itself.

Today we have many madrasahs or traditional schools for Arabic and Islamic education, but in my time there were very few madrasahs. We learned the Holy Qur’an and about Islam at home, usually with the help of knowledgeable elders of the community called guru (teacher). I grew up with many grand- aunts as my gurus and learned from them through the home teaching we call Pagpangadji Ha Lihal. Pangadji is learning and the lihal is a folding wooden stand for the Qur’an. Sometimes there would be 10 to 15 children learning, and although our guru would be cooking in the kitchen she would know if any student made a mistake. She would correct us ‒different chapters and different verses ‒ because the guru memorized the Qur’an, and when she heard a mis- pronunciation, wrong tone or other mistake from any student, she corrected us. We did not have formal educational institutions; our gurus were themselves the institutions.

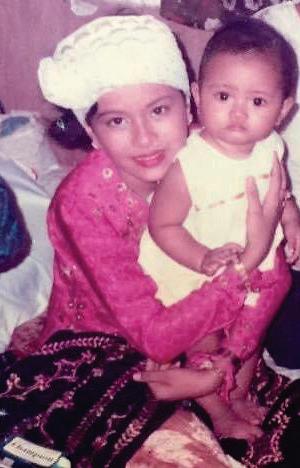

This is a picture of a younger cousin during her Paggunting, a Muslim ‘baptism’ when a child’s hair is ceremonially cut. Practically everybody is there, family and neighbors, with my grandfather leading the ceremony and performing the rituals.

They told us they were not able to go abroad to study, and said they did not know much about Islam. In fact, I can read the Holy Qur’an and I can read Arabic, but I do not understand the language and need to have a translation. Being able to read but not able to understand is quite something! They said: ’You know in our time we knew only Bismillah irahman irahim, ’in the

This is my Pagtammat , a Tausug graduation ceremony for reading the Qur’an

Name of Allah, the most Gracious, the most Merciful’, but it was already a heavy burden for them to carry. That was the Islam of their time.

As for my education, I am a Claretian! Yes, I am a proud Claretian (member of the Congregation of Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary), and always share my story. I first learned about Jesus Christ and then about Mohammad (Sallalahu Alaihi Wasallam). I studied in a Catholic school, and I had access to Bible stories before having access to the Holy Qur’an. I share this because I know that many people are unable to imagine Basilan with Christianity, and I meet people who are surprised to know that I have Catholic friends and know about Christianity.

When I was already based in Manila there would be instances, such as the Mamasapano incident (a shootout between the police and Malaysian terrorists in Maguindanao del Sur) that people would talk about as a Muslim- Christian conflict. It was not! I grew up with Christian friends, Christian neighbors and Christian relatives through intermarriage, and it was not an issue for us. In barangay fiestas, Christian households do

not serve lechon because they know that Muslims will be attending, or they place it in a corner away from the table. And at Ramadhan, Eid’l Fit’r and Eid'l Adha our Catholic and Christian friends join us. So it is simply not an issue between Muslims and Christians.

In the 1990s, after graduating, I became part of a non- government organization through the invitation of my husband, Congressman Mujiv Hataman, who was then a young activist in Basilan. Before becoming ‘politicians’ we were development workers, and we are still development workers. As Mayor, I am responsible for spending government money for development work, and assisting other municipalities in caring for the more than 300 former members of the Abu Sayyaf Group that have returned to Basilan.

When Mujiv became a congressman we transferred to Manila, and for me that was the unveiling of Basilan. When you are uprooted from your home you start to look at it from a new perspective, and I was blessed to meet people who reintroduced Basilan to me. Here I would like to mention Ms. Marian Pastor Roces.

˂ Here I am leading a Community Development and Basilan Agricultural Training Program

When I was Congresswoman of Anak Mindanao, together we organized a travelling exhibition ‘Muslims of the Philippines: History and Culture’. That was when I saw Basilan from a different perspective.

Because I am a Tausug ‒ actually Tausug - YakanSama - Iranun ‒ I was always sure I knew my textiles. I would proudly show Marian our habul tyahi- an (embroidered skirts) and our tennun (woven fabrics), and she would say ’Hmmm, that is so far from and incomparable to the old ones’. It took years of listening to her before I understood and began to see that they are not just pieces of cloth. Textiles are my identity, not handicrafts but our heritage. Our weavers are not factory workers, who can produce meters and meters of cloth. The value lies in the traditional art and weaving skills which must not be compromised by mass production. More than the design and patterns, the value is in the technique. The tapestry in the Yakan tennun and the Tausug pis syabit (handwoven cloths) are two of only five techniques of their kind used in Southeast Asia.

Once I went to Malaysia at the invitation of a friend who asked me to bring an item from Basilan for a fund- raising auction. I brought a tennun and explained it, using my new appreciation; it was auctioned for the equivalent of Php.120,000.00, far more than its selling price in Basilan. But more than the monetary value, it gave me a sense of dignity I had never felt before. Back in Basilan I tell our people this story so they can realize that how we are treated and valued depends on how much we know about ourselves, because if we know the value of our identity we can narrate it and people will see it.

The mat called baluy in Tausug and tepo in Sama is ‘just a mat’ until we see it from a different light, starting by asking our elders. Around three years ago we found a master mat weaver in barangay Marang - Marang. She was the only remaining weaver when we discovered her, but was willing to teach others, and now we already have 30 weavers in that barangay.

When we asked for the names of the designs, the names they told us were translations of the colors and patterns of the weave. Only when we asked if there was an old name did the tepo reveal itself. For example the pattern kyaman buddih is apparently one of the hardest to make, and when I asked what it meant the reply was ’Oh, it’s utang na loob (gratitude)’. Then the old woman said, in Tausug, ’ Awun panumtuman, di katungbasan misan sin ñawa’ , meaning ‘a token that cannot be replaced even with one’s life’. You can imagine the honor if somebody gives you that kind of tepo. They also explained that tepo are what the bride brings to the marriage as her contribution to the family. That is how beautiful these symbols of our identity are.

Another of our cultural traditions that is being introduced to a wider circle of visitors is the great variety of Sama and Tausug food. Heirloom dishes include oko- oko, rice cooked in a whole sea urchin shell; utak- utak, a spicy fish cake with grated coconut; junay, rice with burnt coconut meat and spices wrapped in banana leaf; panyam, a deep- fried pancake made of glutinous rice, brown sugar and coconut milk; putli mandi, steamed balls made of glutinous rice or cassava filled with sweetened coconut; and jaa, also known as lokot- lokot, a crispy fried pastry made from glutinous rice flour and sugar which is usually served on special occasions such as Eid’l Fit’r.

The pangalay, the traditional Tausug ‘fingernail dance’, is seen as a dance performance, but viewing it through my new lens I realized that the pangalay is not a just a dance. Although introduced to the world as such, the pangalay ‒which, according to Marian, may have come from the Sanskrit words pang alay ‒ is actually an offering. This makes sense because our ancestors believed in the spirits from another realm. They believed that all creations have spirits, and performed the pangalay not as a dance but as an offering of goodwill to these spirits. That is why, traditionally, the one who performs the pangalay appears to be in a trance, with no choreography, just moving to her own rhythm and flow. People

will place their offerings, nowadays usually cash, on the performer because she serves as the medium to the spirits. But let me emphasize: this is not Islamic. This is cultural. This is Tausug.

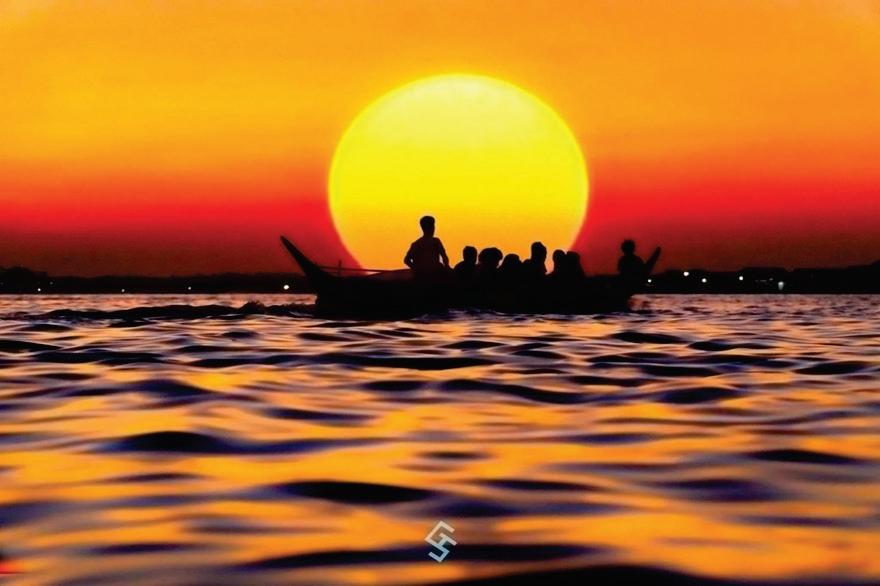

And of course I must mention our boats. The sakayan, small outrigger boats used by fishermen, are a symbol of our local fishing communities and their reliance on the sea for sustenance. We now have the annual Sakayan Festival. Our festival in Isabela City in April used to be called the Cocowayan Festival, but we changed the name to give tribute to our connection with the water, the very core of our identity. We have an old Sama saying that ’ the land is for the dead, the water is for the living’. Our Sakaya n Festival is a celebration of how the different cultural communities arrived in Isabela and made it our home.

Another beautiful story illustrates our connection to water. We once met an elderly Yakan who described the community she came from. Marian asked if she knew of a family who came from the same area, and I was amazed by her answer: ‘ Huun. Hangka masjid kami, hangka tubig kami’ meaning ‘Yes, we are of one mosque, we are of one water’. The depth of our identity is beyond beautiful, if we only knew.

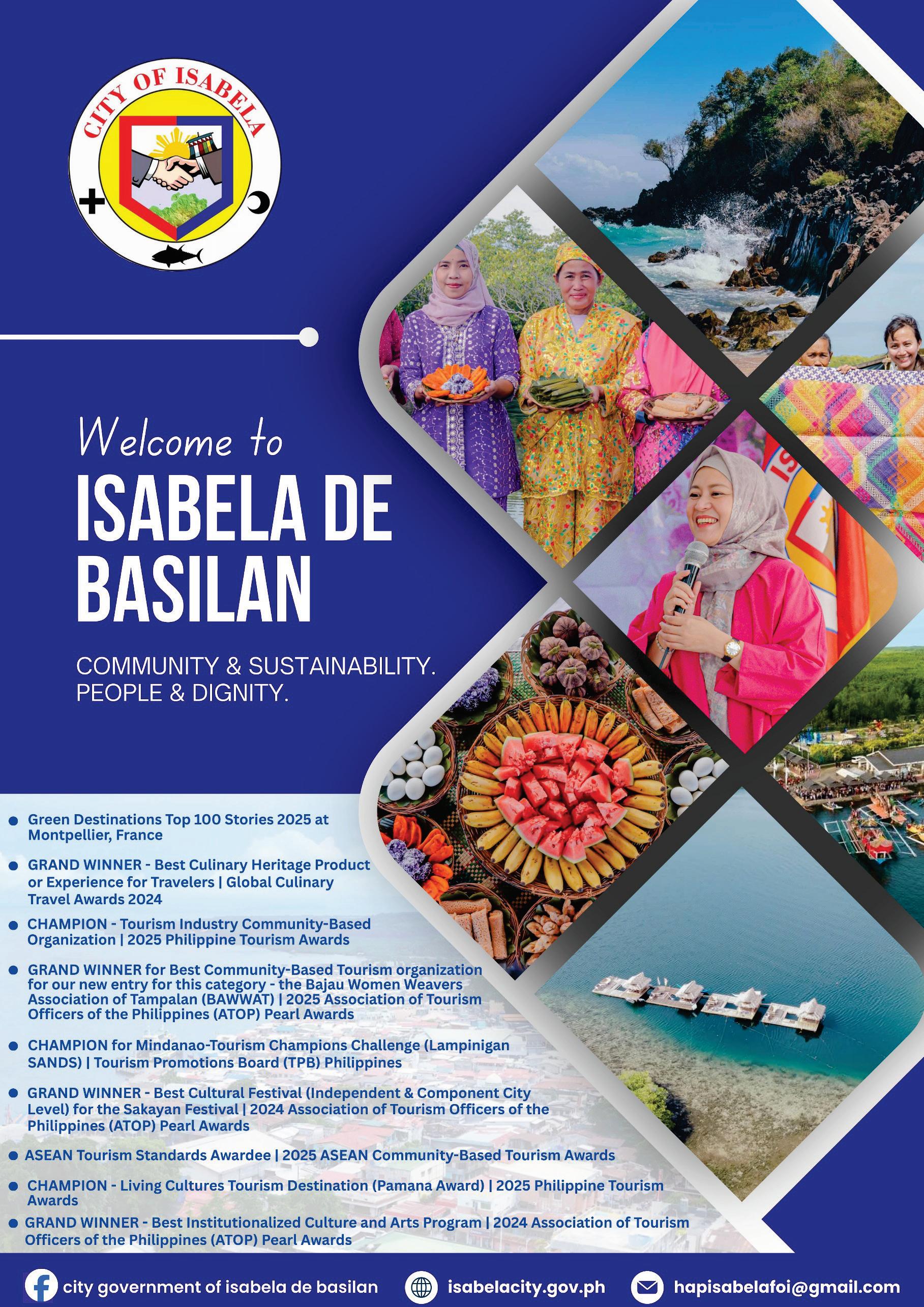

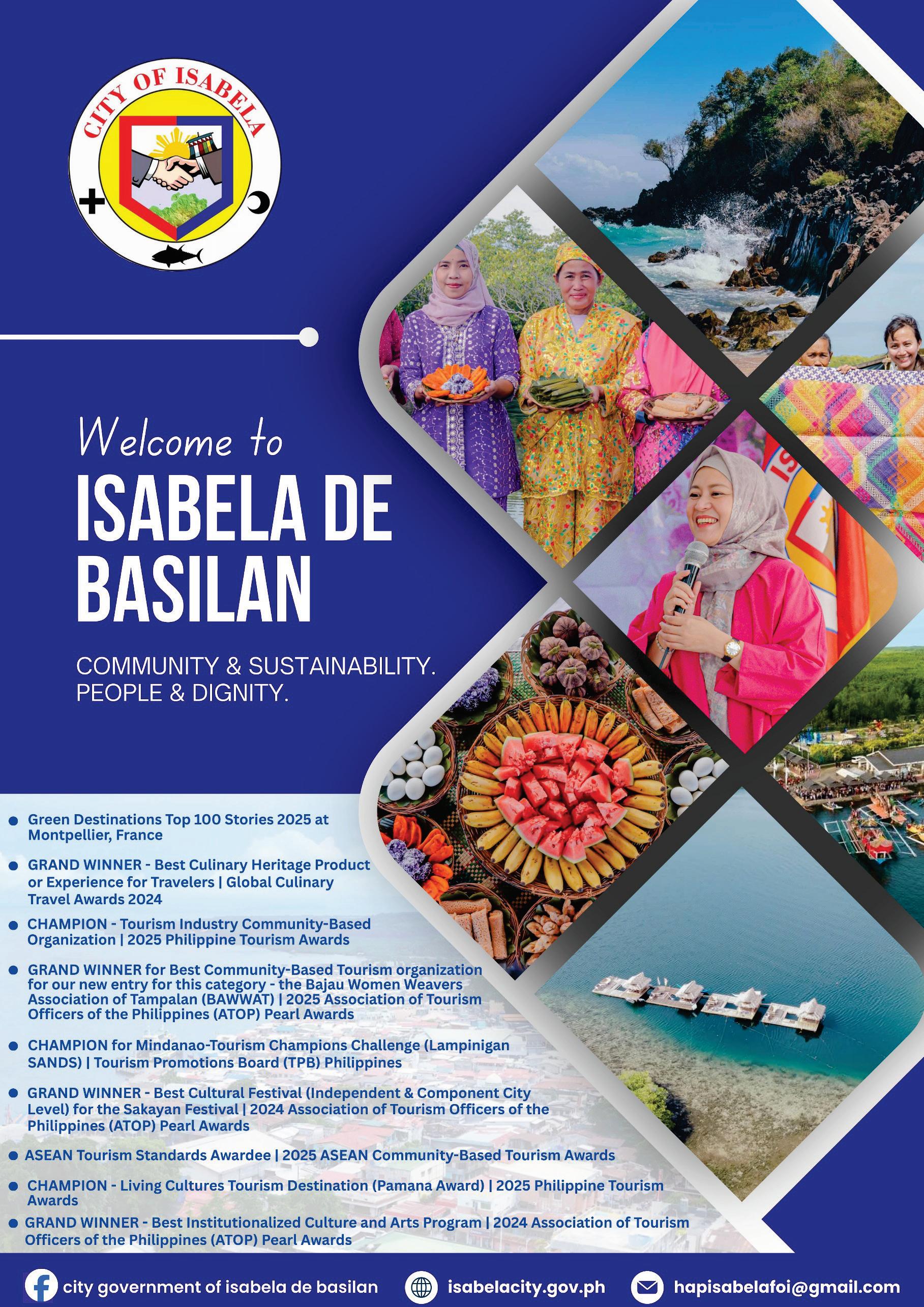

Let me proceed to the Basilan we are creating today, with the focus on Isabela, my city. We are the only ISO- certified LGU (local government unit) in the entire Region IX (Zamboanga Peninsula). We were also the only city in Region IX to be awarded the Seal of Good Local Governance (SGLG) in 2023, and one of only two (the other being Dipolog) to receive the SGLG in 2024. As for tourism, in 2018- 19 we used to receive around 20,000 to 30,000 visitors in a year, but in 2022 our tourist and visitor arrivals went up to 370,000, and in 2024 they increased again to 513,000.

Every year, the National Competitiveness Council ranks cities and municipalities based on five pillars: (1) Economic Dynamism, (2) Government Efficiency, (3) Infrastructure, (4) Resiliency, and (5) Innovation. In 2018, Isabela City ranked only 108 out of 113. But in 2022, we were the 3rd Most Improved in Competitiveness throughout the country, jumping to 45th rank, and in 2024 Isabela City made it to the Top 15 Most Competitive Cities in the whole of Mindanao. And what we

are most proud of, and thankful for, is our Poverty Incidence: in 2018 poverty among families was at 41.8 %, but by 2024 it had dropped to only 10%.

So, this is Basilan and the Isabela City that we are creating and will continue to create with your help. I say this because it is so very important to us. When people ask me what I have done I reply that all these beautiful things are happening in Isabela because of all us in the city. I always attribute the improvements to the fact that we started connecting with our own identity.

It is important for us to see where we came from, and it is important for us to be able to set a direction. We need to understand where we are coming from and what we have achieved. I always say that for a people like us who have suffered so much, not just our image, but actual lives lost to conflict, lessons must be learned from the realities of the past decades. As I say, it is very importa nt for us to know and reconnect with our great past. We must remember what a great people we once were, because only then can we be great again.

This article is an edited transcript of the speech delivered by Mayor Dadah as an introduction to the PHIMCOS meeting on ‘The History and Mapping of Basilan and the Basilan Channel’, held on November 13, 2024.

Malamawi Island, Isabela City, Basilan for inquiries please contact

Hotline: 0917 133 - 9036

Email : pahalimalamawi@gmail.com

Facebook: Pahali Resort

by Felice Noelle Rodriguez & Peter Geldart

Sa ibabaw ng tubig

Mga isla’y hiwaláy, Sa pusod ng daigdig Lahát ay magkakaugnáy.

‒ Paring Bert S.J.

On the surface of the waters

Every island seems isolated, In the heart of the universe Everything is interconnected.

‒ Albert E. Alejo S.J.

The story of Basilan is best told through the island’s connections with other lands, made possible by the bodies of water that surround it

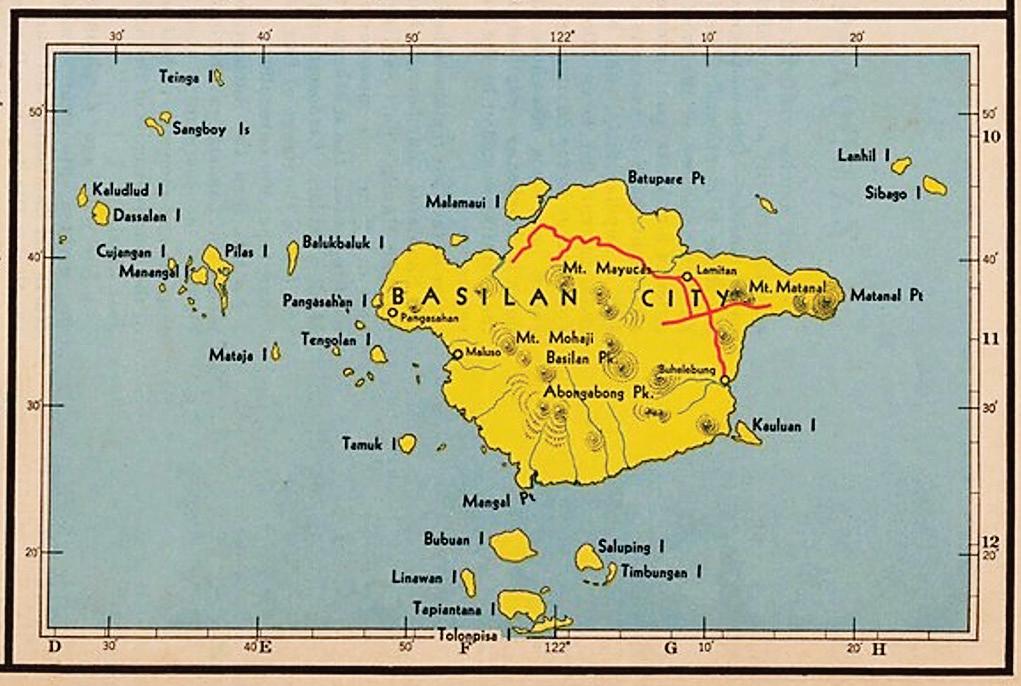

Located off the southwestern coast of Mindanao, Basilan is connected to the City of Zamboanga to the north by the Basilan Channel or Basilan Strait, which is about 17 nautical miles (31 km.) wide at its narrowest point. The Basilan Strait was once described as the great highway for ocean traffic. Its military importance was due to its strategic position as ‘one of the two main approaches to the mainland of Asia from the SW Pacific’. (1)

The Sulu Sea to the north and northwest links Basilan to the Pilas Islands nearby and, further afield, to the Cuyo Islands, Cagayan Islands, Palawan and all the way south to the Turtle Islands and Tawi- Tawi. The islands of Bubuan and Tapiantana, south of Basilan, are also part of the province of Basilan. The Sulu Archipelago lies further south, like a string of beads from the tip of the Zamboanga Peninsula to the north of Borneo, with the major islands being Basilan (the northernmost), Sulu and Tawi- Tawi. The Celebes Sea, to the east of the island, encompasses the western part of the Sulu Archipelago and northern Kalimantan, the southern part of Mindanao, the Sangihe islands and the Minahasa Peninsula of Sulawesi.

Lying between latitudes 6°15' N. and 7°00' N. and longitudes 121°15' E. and 122°30' E., Basilan is a hilly island with undulating coastal areas and a total area of 1,266 sq. km. The highest mountain is Puno Mahaji (aka Mount Mahatalang or Basilan Peak), located near the centre of the island to the southeast of Isabela City, with an

elevation of 971 m. above sea level. Isabela City, the island’s largest city and its administrative center, has a population of over 130,000 and lies on the northwestern shore of the island adjacent to the small island of Malamawi.

Historical importance

The indigenous inhabitants are the Yakan, part of the Sama ethnic group. A linguistic theory by A. Kemp Pallesen puts the Samal (often recorded in documents as Samal Laut or Lutao) in the Straits of Basilan and the Zamboanga region all the way back to 800 AD. (2) The Yakan subsequently moved to the interior, but the Samal also lived in the coastal areas. Later arrivals, mainly in the coastal areas, were the Tausug from the Sultanate of Sulu, the Subanen from the Zamboanga Peninsula, and the Iranun (also c alled Illanun, Illanaon, Lanun or Illano). And in the Spanish and American colonial periods others came, built houses and plantations, and began to call Basilan home.

In his study of the possible Cham origin of Philippine scripts, the historian Geoff Wade indicates a possible connection between Basilan and Cambodia, since the Chinese Song Dynasty work Zhu- Fan Zhi (‘A Description of Barbarian

Nations’) by Zhao Rukuo, completed in 1225, includes ‘Bo - si- lan’ in a list of Cambodia’s ‘dependent countries’. (3)

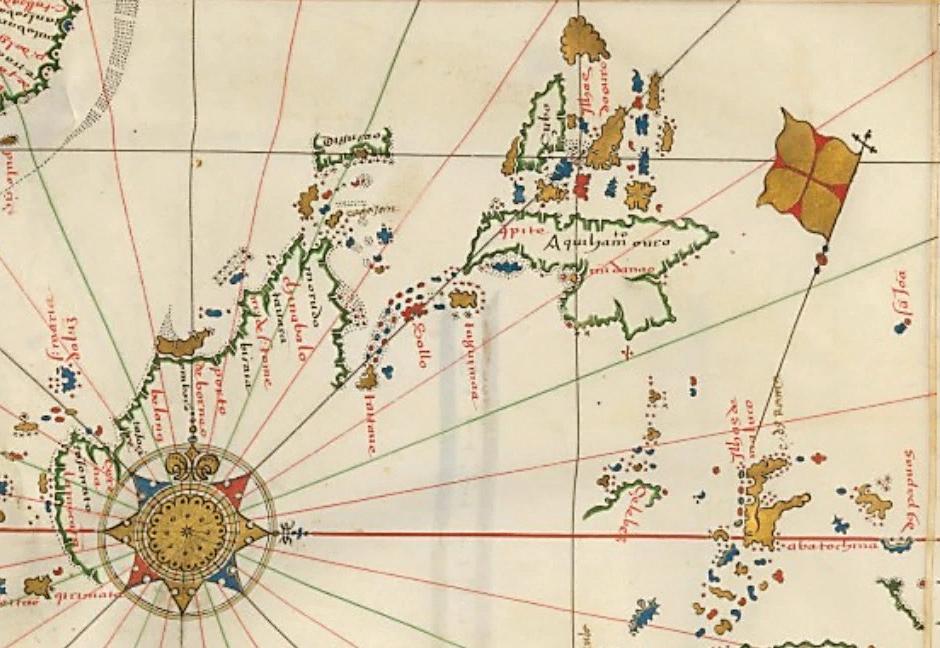

The Zamboanga Peninsula, Basilan Island and the Strait have long been important features for navigators and cartographers, especially for European explorers sailing for the Spice Islands. As explained by Miguel Rodrigues Lourenço of the Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, in the 16th century Portuguese navigators would use the tip of the Zamboanga peninsula as a landmark. He describes the course of their voyages from Malacca to the Moluccas as follows:

A rutter [the Livro de Marinharia de Bernardo Fernandes ] of 1548 indicates that ships proceeding from Melaka inbound to Maluku via Northern Borneo should approach the boqueirão de tagima (the Strait of Basilan), which they should cross, navigating from there to the Sangihe Group, Siao and Ternate. From this we can ascertain that modifications made in the toponymic description of the Zamboanga peninsula and the Sulu Sea derive from a pract ice of navigation along Northern Borneo towards the Sulu archipelago and then through the Basilan Strait, already established by the mid-sixteenth century.(4)

Detail from the Carta Castiglioni attributed to Diogo Ribeiro, c. 1525 (Estense University Library )

Detail from Terza Tavola by Giacomo Gastaldi, woodblock edition, 1554

Detail from map of Asia by Everts Gijsbertsz , 1599 (State Library of New South Wales )

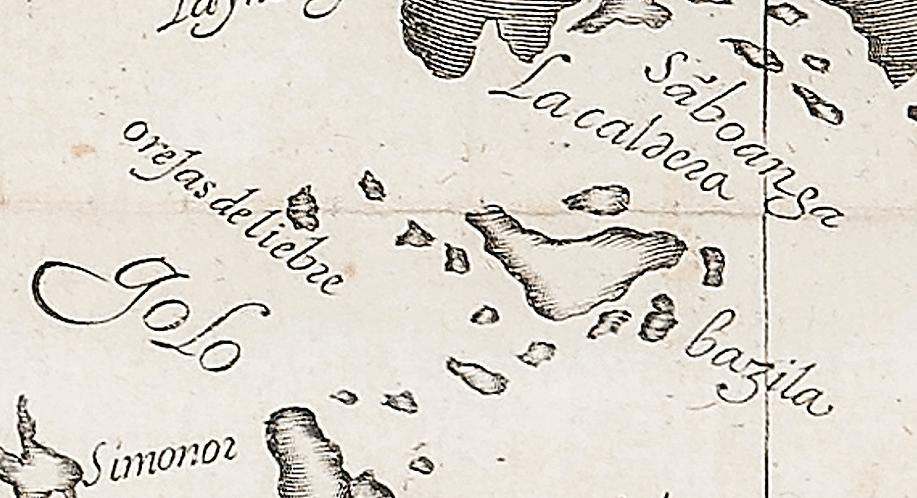

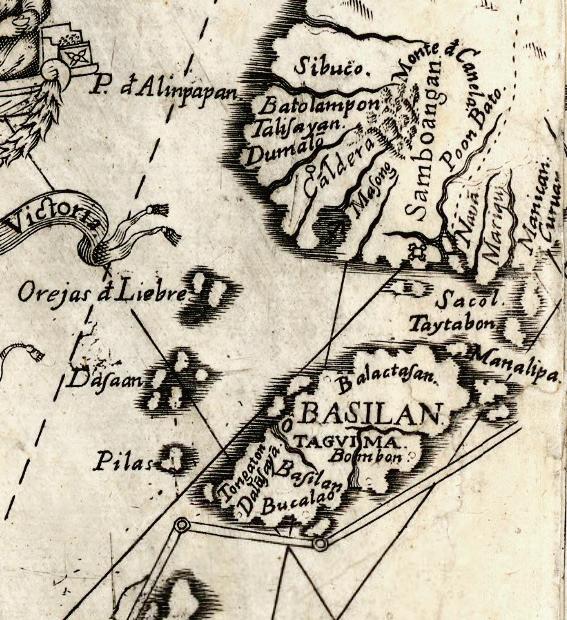

Detail from Planta de las Islas Filipinas by Marcos de Orozco, 1659 (Rudolf J.H. Lietz / Gallery of Prints , Manila )

Detail from the map of Sulu by Antonio Pigafetta, c.1525 (Yale University Library )

Detail from Urbano Monte’s mappamundi, c.1587 (David Rumsey Historical Map Collection )

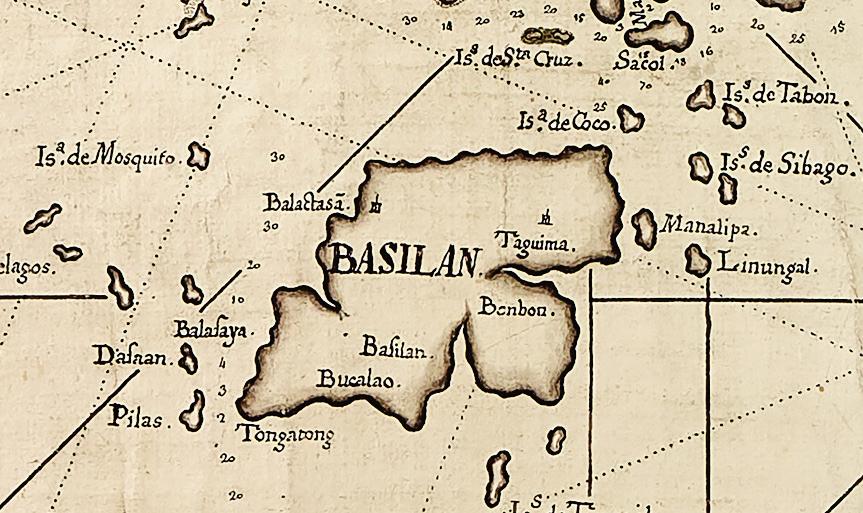

Detail from Carta particolare del Isola Mindanao … d’Asia Carta XI by Robert Dudley , (1646) 1661

Detail from Nieuwe Afteekening van de Philippynse Eylenden geleegen in de Oost -Indische Zee by Johannes II van Keulen, 1753

Navigators travelling westwards from Polomolok or Cotabato towards Zamboanga or Basilan were guided by Mount Matangal, a volcano at the eastern end of the island described as follows: ‘ The eastern headland [of Basilan] is long and has a picturesque, conical peak, called Mount Matangal, which rises about 648 meters above sea level. This peak is a very prominent landmark, visible to a great distance from all points in the Celebes Sea and in the Straits of Basilan. ’ (5)

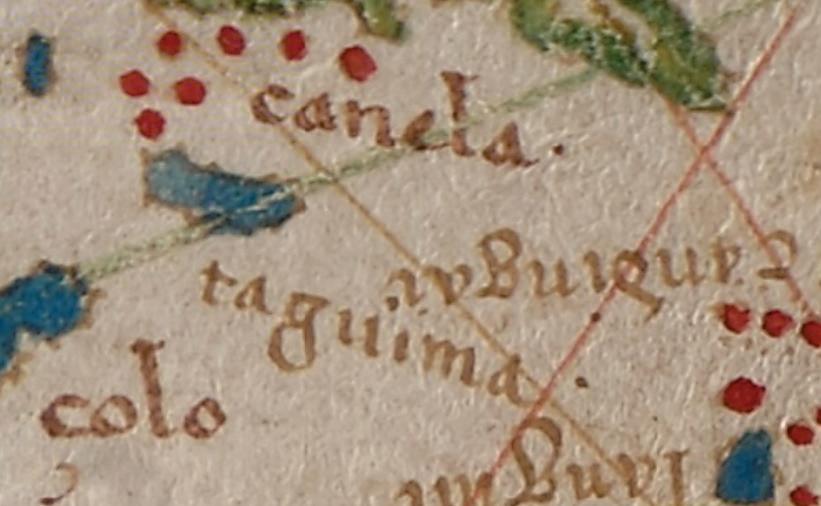

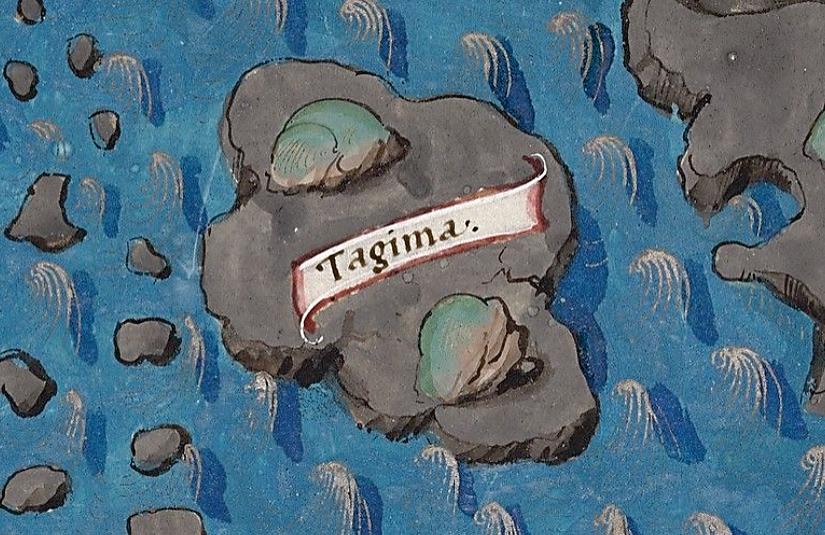

On early European maps the island of Basilan is given the name ‘Taguima’, with variant spellings thereof. The Carta Nautica delle Indie e delle Molucche by Nuño García de Toreno ‒ the first map to be created after the return of the Magellan- Elcano expedition in 1522 ‒ and the Carta Castiglioni (c.1525) attributed to Diogo Ribeiro show ‘Taguima’ In his map of the Sulu islands, included in his account of the expedition, Antonio Pigafetta opts for ‘Tagima’, which he calls the ‘Island of Pearls’. (6)

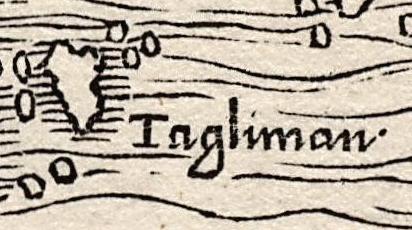

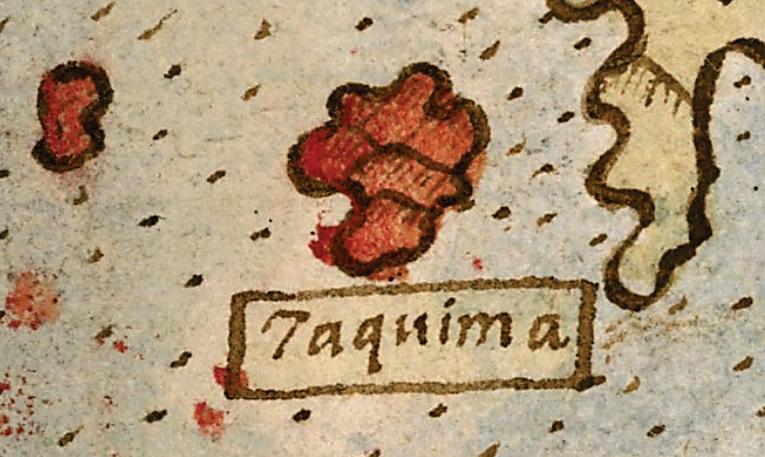

Giacomo Gastaldi uses ‘Taguima’ on his map India Tercera Nova Tabula (1548), but ‘Tagliman’ on his map Terza Tavola (1554) (7) and ‘Taguina’ on his map Terza Parte Dell'Asia (1565). The world map published by Gerard Mercator in 1569 has both ‘Tagima’ and ‘Taguima’ , and Urbano Monte’s global map of c.1587 has ‘ Taquima’. Portuguese manuscript portolan atlases by Fernão Vaz Dourado (c.1560) retain the name ‘tagima’, as does the 1598 manuscript atlas by Martin Llewellyn; but a 1599 manuscript Dutch portolan of Asia by Evert Gijsbertsz shows ‘tigima’ .

In his 1646 chart of Mindanao, Robert Dudley names the island ‘ Taginio o Tagimio’(8) ; A Chart of the Tradeing part of the East Indies (1672) by John Thornton uses ‘Taguna’; and A Chart of the Eastermost part of the East Indies (c.1677) by John Seller has ‘Tagyma’. The maps and globe gores published in the 1690s by Vincenzo Coronelli show ‘Tagyto’, and in 1717 a map by Paolo Petrini uses the name ‘Tanquna’. (9) Some have speculated that ‘Taguima’ was derived from the Tagihamas or ‘people of the interior’, as they were called by later Tausug and Samal arrivals, but we believe that, according to oral tradition, the name may have been the name of a local chief. The toponym subsequently became that of a settlement on the island.

A new name, ‘ Bazila’, appears on the Planta de las Islas Filipinas engraved by Marcos de Orozco in Madrid in 1659. The map was published in 1663 in the Labor evangélica by Fr. Francisco Colin, S.J., in which he provides the following description of ‘Basilan’:

Away from the mainland of this island of Mindanao, the government of Samboanga holds an extensive region across the range of mountainous islands that occupy the sea near the great island of Borneo, to which place our weapons also go. The largest, and closest to Samboanga, being only three leagues away, is that of Basilan, which lies at six and a half degrees; its shape is almost round.

It spans fourteen leagues. Its largest population is in the eastern part, where they are already vassals of His Majesty, and baptized; and although the effective tribute payers have never exceeded three hundred, there will be two hundred more as they are s lowly trying to submit themselves to the yoke of the Faith, and exercise obedience to the Spanish government. It is a fertile land of fruits, not only those common to these Islands, but also others particular to Malacca in India, such as the durian, the mango, and others of equal bounty. And so this Island of Basilan is part of the presidio and the new settlement of Samboanga.(10)

Detail from the Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas by Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde, 1734 (Library of Congress )

Both ‘Basílan’ and ‘Tagíma’ appear on the manuscript Mapa de la Isla de Mindanao of c.1683 held in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, and ‘Bassilan’ is on an untitled and undated manuscript map in the Museo Naval in Madrid, described as Navegación al sur de la Ysla Mindanao (c.1700). However, in their Carta Chorographica del Archipielago de las Islas Philipinas of 1727, Francisco Diaz Romero and Antonio de Ghandia (aka Echeandia) revert to ‘Taguíma’ The magnificent Carta Hydrographica y Chorographic a delas Yslas Filipinas produced by Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde in 1734 uses both names for the island: ‘Basilan’ (in capital letters) above ‘Taguima’ (in slightly smaller capital letters). Maps of the Philippines by Johannes II van Keulen published in Amsterdam in 1753 identif y Basilan as ‘ Taguna’ or ‘Tacuna’ (11)

The name Basilan may derive from the island’s iron ore deposits. As Tausug traders from Jolo came to Taguima to purchase high- quality magnetic iron ores, which they used to make swords and pirahs (knives), the island became known as the source of basih- balan, the Tausug word for magnetic iron.

Alliances and offensives

Alliances of datus from various parts of Basilan would shift from time to time from the late- 16th to the 18th centuries. In 1578 Governor- General Francisco de Sande sent a war expedition to Brunei under Captain Esteban Rodriguez de Figueroa, who asked the Sultan of Sulu for a treaty of friendship. Raja Pangiran initially rejected the request, but subsequently capitulated and ‘acknowledged himself and his descendants vassals of his Majesty Don Philip, King of Castile and Leon, and as a token of his fealty and vassalage gave twelve pearls and thirty- five taels of gold in his own name and in the name of his subjects of the islands of Jolo, Tagima, Samboangan, Kawit, and Tawi- tawi, these being his dominions’. (12)

In 1602 a raiding fleet was put together to attack the Visayas, comprising 50 war vessels from Ternate, Sangil and Tagolanda, and at least 60 from Maguindanao. ‘ The whole expedition was under the joint command of Raja Mura, Bwisan and Sirongan, who were calling up 100 fighting men from each of their villages. They had invited Liguanan, the principal datu of Basilan, to join

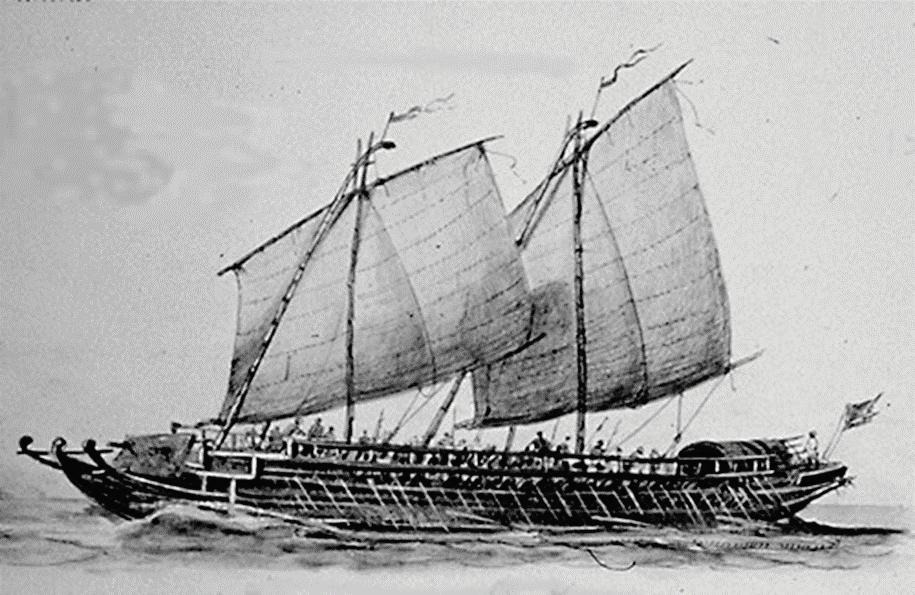

Illustration of a late-18 th century Iranun lanong warship by Rafael Monleón (public domain )

them, and Liguanan had called an assembly of the datus of his island and of Zamboanga at which it was agreed to add 35 sail to the Magindanau fleet. ’ (13)

In 1624 the reigning Raja of Sulu, Batara Shah Tangah, sent an embassy to Manila to ask Spain for help in his dynastic struggle against his cousin, Badasaolan ‘who had established his power among the Samals of Basilan Island’. Although they were fishermen, the Samals ‘proved themselves respectable fighters when aroused, and Badasaolan apparently succeeded in arousing them’. However, ‘with the help of the Spaniards, Badasaolan was induced to listen to reason, and [in 1626] after complicated negotiations Bata ra’s successor, Raja Bungsu, was installed as unchallenged lord of all the Sulus’ (14)

Sultan Kudarat of Maguindanao maintained lucrative trade routes with the Sulu Archipelago, and maintained offensives against the Spanish from his base at Lamitan in Basilan. The settlement was crushed by General Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera in 1637, one year after the Spanish fort in Zamboanga had been established, and the Yakan leading the local resistance retreated inland.

From Datu Ache, the prime minister of Raja Bungsu of Jolo, who was sent to make peace overtures, Corcuera demanded ‘the surrender by Jolo of all claims to the island of Basilan and its outright annexation by Spain’, but the Raja’s reply was ‘who demands Ba silan from the Sulus demands war, not peace’. (15) Corcuera accepted the challenge, defeated Raja Bungsu, and occupied Jolo.

In order to counter the threat posed by the Chinese rebel general Koxinga , Spain withdrew from Zamboanga in 1662, but returned to Fort Pilar in 1719. Although the Moro raids continued, in 1725 Jolo ceded Basilan to Spain: ‘ With a Chinese trader named Ki Kuan acting as intermediary, a treaty was actually signed in 1725 establishing trade relations, providing for the ransom and exchange of captives, and ceding the island of Basilan to Spain. ’ (16) After his accession two years previously, in 1737 Sultan Alimuddin of Sulu signed an improved version of the Ki Kuan Treaty. This so - called Valdés Tamón Treaty added two important articles to the earlier convention: ‘ It was to be an offensivedefensive alliance, and the signatories made themselves responsible for infractions of the peace by their respective subjects. ’ (17)

New arrivals

The proselytisation of Basilan started in earnest in 1637 with the arrival of Jesuit missionaries from Zamboanga. Fr. Francisco Lado, S.J., the first missionary assigned to Basilan, established a mission at Pasanhan / Pasangan (later Isabela), near the mouth of the Aguada River. Fr. Lado was able to establish a relationship initially with

the population of Lutao (the Spanish name for Sama living on the coast) and afterwards with the Yakan after the death of their chieftain Tabako. However, stirred up by Kudarat, in 1644 ‘the attitude of the Lutaus of Basilan became so threatening that the Jesuits there had to be withdrawn’ (18) .

In 1667 Fr. Francisco Combés, S.J. published a detailed description of the island:

Distant three leagues of sea and stretched along in front of Zamboanga is seen the Island of Basilan, twelve leagues in circumference. It is the garden of Zamboanga; for from it comes the entire supply of fruit and table delicacies, bananas, gabes (an edible root) [taro], sugar cane, which is found as thick as a man’s thigh and twelve feet long, lanzones, a small fruit which is found but in few parts … in general appearance like a nut covered by a rind which is flexible and contains within three or four cells so sweet and delicate a substance that a person can eat a basketful without hurting the stomach nor surfeiting the taste. All that is found in the other islands abounds here, and of its products the markets of Zamboanga are filled.

The abundance of rice is very great. The earth is fertile and convenient for the people to cultivate, so that the greater part are engaged in tilling the soil; from the surplus they supply the entire Lutaya nation. … Even though this island is smaller, it has the resources and conveniences of many rivers and an abundance of nipa with which it supplies the population of Zamboanga with roofing for their houses in as much as it cannot be found nearer. In the chase it abounds with deer and wild hogs, the former of the same beautiful color and skins as in Jolo. The timber is of the hard variety suitable for building and cabinet work, of which the island is the main source of supply for Zamboanga.(19)

In the 18th century, the rise of the Sulu Sultanate increased the demand by the Tausug for goods to trade with the Chinese and the British, and for slaves. This led to the growth of Sama / Lutao and Iranun settlements across the region, including Maluso on the west c oast of Basilan, where the inhabitants were employed as traders and fishermen. In 1746 the Dutch occupied Maluso and established a fortified base called Port Holland. The following year they attacked the settlement of Taguima but were defeated a nd expelled from Basilan by Datu Bantilan of Sulu. Today Port Holland is retained as the name of a barangay in the municipality of Maluso.

From Maluso the Iranun launched slave raids on Zamboanga, the Visayas and Southeast Asia. The raids would continue well into the 19th century, as recounted by James Francis Warren:

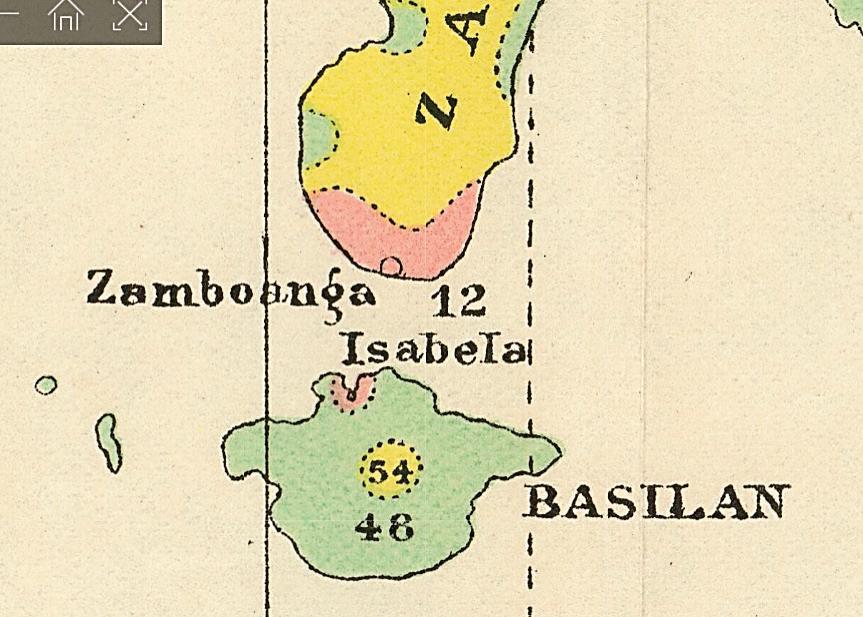

Detail from Mapa Etnografico del Archipielago Filipino by Ferdinand Blumentritt, 1890; the map shows areas populated by ‘Hispanic Christians and Filipinos’ (pink), ‘New Christians and Infidels ’ (yellow) and ‘Moros ’ (green) (Smithsonian Institution )

The Maluso Samal of Basilan harried the settlers of Zamboanga who attempted to trade with Cotobato. Houses beyond the presidio walls were scattered, and the Samal often attacked them at night. … The raids made it impossible for towns -people to fish and, ironically, Zamboanga became dependent on its assailants, the Samal of Maluso, for fresh supplies.(20)

As slave raids became more frequent, the native Yakan in Basilan retreated into the island's interior; their biggest coastal settlement was at Lamitan, on the northeastern shore, away from the routes of the pirate raiders from Sulu and Maluso to Zamboanga. The main trade goods supplied by the Yakan for export were forest products such as lumber, honey and beeswax, kangan (thinly woven cloth) and rice.

Warren explains further:

Trade between the Sultanates of Sulu and Cotabato was based on rice, … between a sultanate that had limited contact with the outside world and one which controlled the external trade of the region, and between an area endowed with rice and one which had little. … Rice was also shipped to Jolo in large quantities from Basilan and the outer islands of Cagayan de Sulu and Palawan. On Basilan, rice was grown by the Yakan or agricultural Sama, who resided inland on the eastern and northern parts of the island. … As agriculturalists, the Yakan were dependent on maritime stranddwelling Samal and Taosug for trade items vital to their life and culture such as salt, pottery, iron tools, brassware and opium … . In return, upland rice and forest products were brought to the Taosug at coastal villages.(21)

During this period the demography of the area changed because of the eruption of Mount Macaturin (Makaturing) in 1765. This displaced many of the Iranun, originally Maranao people, from their homelands around Lake Lanao in central Mindanao. Some of the Iranun occupied parts of the western and southern coasts of Basilan. (22) Together with the movement of the Iranun southwards, there would also be a shift of the centre of boat- building activity from Cotabato to the Sulu Archipelago. As Basilan and its nearby islands were especially rich in shipbuilding materials, the Samal of Maluso became celebrated boat- builders.

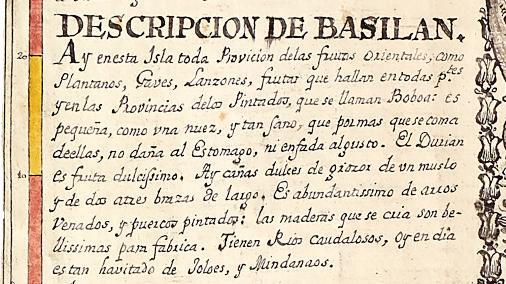

Details of Basilan Island and its accompanying description from Mapa dela Isla de Mindanao by Nicholas Norton Nicols, 1762 (United Kingdom Hydrographic Office)

Nicholas Norton Nicols, an enterprising English merchant, first visited the Philippines in 1750- 54 and became convinced that the cultivation and export of commodities such as indigo and cinnamon from Mindanao could become a source of great profit for Spain. He converted to Catholicism and in c.1757 produced a ma nuscript map of Mindanao that shows Basilan.(23) In 176162 Nicols was put in charge of an expedition to Caraga by the acting Governor- General, Archbishop Manuel Antonio Rojo, and on his return to Manila he drew two manuscript maps which were captured by the Royal Navy and are now held in the archive of the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office.

Norton’s Mapa dela Isla de Mindanao depicts the island of Basilan with Balactasa, Taguima, Bonbon, Basilan, Bucalao and Tongatong shown as towns on the island. (24) The map also includes a panel with descriptions of Mindanao and Jolo, and the following description of Basilan (which is clearly copied from that written by Fr. Combés):

This island has a full supply of oriental fruits, such as bananas, taros, and lanzones , a fruit that is found everywhere here and in the provinces of the Visayas, where it is called boboa; it is small, like a walnut, and so healthy that no matter how many you eat, they neither trouble your stomach nor irritate your tastebuds. Durian is an exceedingly sweet fruit. There are sugarcanes with the thickness of a thigh and two to three fathoms [1 2 to 18 feet] long. There is a vast abundance of deer and native pigs; the timber grown there is wonderful for woodworking. There are fastflowing rivers occupied during the day by Joloese and Mindanaos.(2 5)

Alexander Dalrymple, who was employed by the Honourable East India Company (EIC) and would in 1795 become Hydrographer to the Admiralty, visited and surveyed the Sulu Archipelago on each of his three voyages to the Philippines: in charge of the Cuddalore in 1761- 62, and of the London in 1762 and again in 1763- 64. The coasts and some topography of ‘Basseelan’ are shown on A Map of part of Borneo and The Sooloo Archipelago. (26) In addition, his chart of The Sooloo Archipelago, which uses the spelling ‘Baseela n’, has a line of soundings along the west coast and shows the towns of ‘Maloza’ and ‘Gubawang’. ( 27)

On his visits to Sulu Dalrymple was accompanied by the geographer and EIC cartographer James Rennell who, in an unpublished account titled Journal of a Voyage to the Sooloo Islands and North West Coast of Borneo, wrote about his voyage in 1762- 63. Two copies of the manuscript have survived, and both have footnotes by Rennell and annotations added by Dalrymple.

One of Rennell’s footnotes reads: ‘ These Slaves are the inhabitants of part of the Philippines Islands that are taken Prisoners by the Illanians, a Savage people inhabiting the North part of Mindanao. Some of the Illanians are now settled at Basseelan & Sooloo from whence they fit out their Privateers. ’ To this, Dalrymple has added: ‘ Greatest part are not Slaves purchased but Vassalls, Natives of Sooloo and the Islands. ’ ( 28)

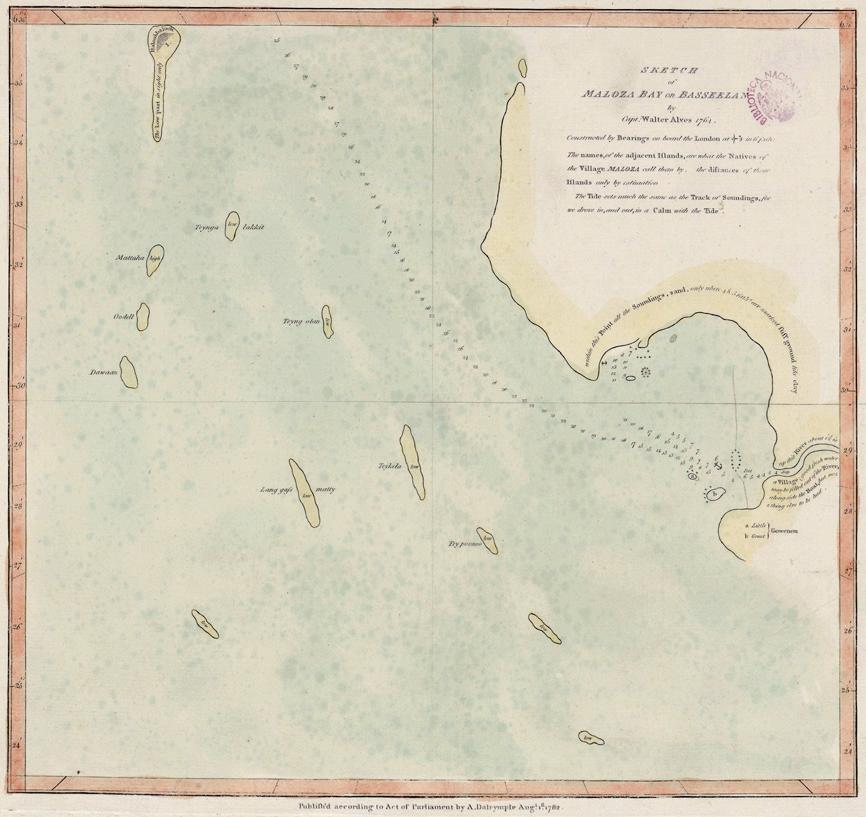

In 1764 Walter Alves, the captain of the London, produced a Sketch of Maloza Bay on Basseelan, a chart of the bay of Malosa (today Maluso), on the southwest coast of Basilan. The chart, which was published by Dalrymple in 1782, shows lines of soundings, anchorages, and the mouth of a river

Sketch of Maloza Bay on Basseelan by Walter Alves, published by Alxander Dalrymple, 1782 (Biblioteca Nacional de España )

leading to the village, with a note reading ‘up this River about 1- ½ is a Village; good fresh water may be filled out of the River alongside the Boat, but nothing else to be had’. ( 29)

Thomas Forrest, a navigator and employee of the EIC, explored the Sulu archipelago and the south coast of Mindanao in 1774- 76 on a voyage of exploration from Balambangan to New Guinea in the galley Tartar. The untitled map published in the book he wrote about the expedition shows ‘Baseelan’, and Forrest records that on 19 November, 1774 ‘we saw the island of Basilan … an island belonging to Sooloo, and about the same size’; two days later he visited Basilan ‘ where I was told by Tuan Hadjee's people, there was choice of good harbours’.(30) In writing about Zamboanga, he states that ‘ the passage between Samboangan and the island Basilan, … being narrow, the Spaniards prevent Chinese junks from passing this way to Magindano’. (31)

In 1792 the Philippines was visited by the fiveyear expedition to South America and the Pacific Ocean led by Alessandro Malaspina in the corvettes Descubierta and Atrevida with the aims of making scientific observations, reporting on the state of Spain’s overseas possessions, and producing accurate charts of their coastlines. The expedition left Manila in mid- November for the return voyage to Cadiz and arrived in the Basilan Channel on 22 November, where they anchored off the harbour and fort of Caldera. ‘ We could already see, stretching from west to east, much

of Basilan Island, which is notable for its hummocky hills, particularly one near its eastern end which has just the shape of a Chinese Mandarin’s hat. ’ ( 32)

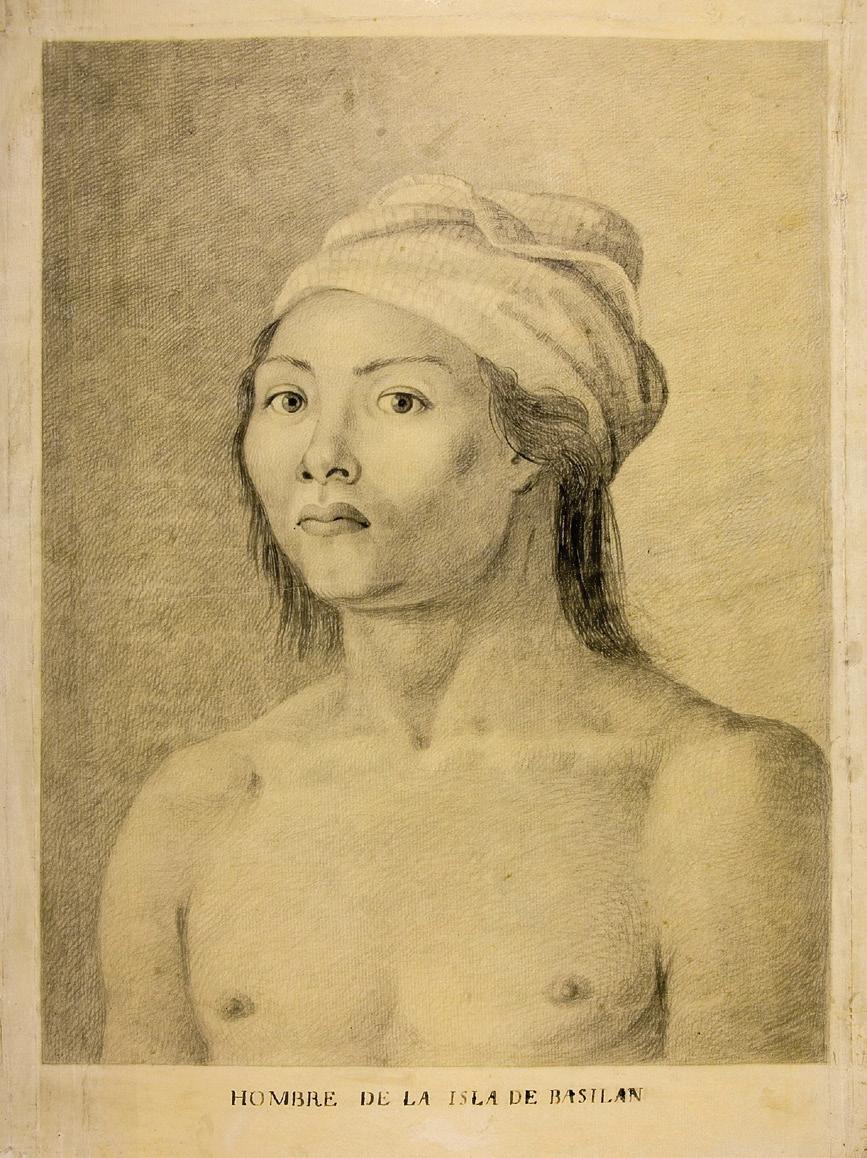

They enjoyed the hospitality of the Governor of Zamboanga, and undertook a hydrographic survey of the channel, concluding on 29 November with ‘some bearings on the islets bordering Santa Cruz, so as to join the outer points of our survey with the extremities of the island near Basilan [i.e. Malamaui]’.( 33) Juan Ravenet, an Italian painter and engraver, joined the Malaspina expedition where, as one of the artists on board, he was commissioned to paint portraits of the people they encountered and scenes from daily life. These include a sketch of a man from Ba silan wearing a kind of turban. ( 34)

Sketch of a man from Basilan by Juan Ravenet , 1792 (Archivo del Museo Naval de Madrid )

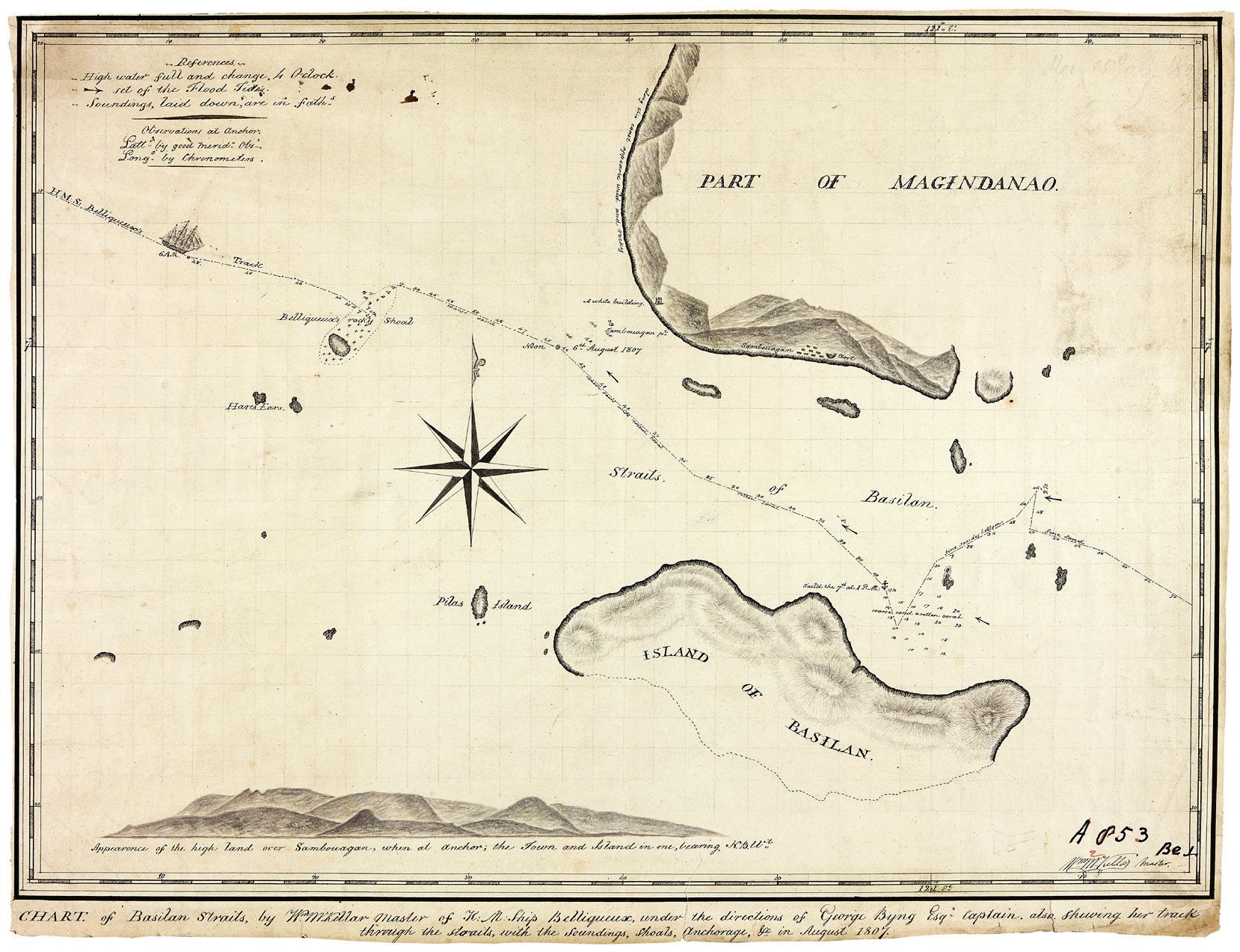

In 1807 the Royal Navy 64- gun, third rate ship of the line HMS Belliqueux (Captain George Byng, later Viscount Torrington) sailed through the Basilan Strait. Belliqueux was part of the English squadron based at Madras under Rear- Admiral Sir Edward Pellew which undertook operations against the Dutch in the East Indies. The Master, William M. Kellar, drew a manuscript chart showing the ship’s track from 5 to 7 August, including the dangerous ‘Belliqueux Shoal’ to the

northeast of Teinga Island (west of Zamboanga), the north of Basilan, soundings and hydrographic details. (35) The chart was subsequently published in The Naval Chronicle (36)

In his pilot book, the India Directory, first published in 1809- 11, James Horsburgh describes Baseelan Island as ‘high, and extensive, separated from the S.W. end of Mindanao by a good channel, called the Strait of Baseelan’. He records the islands of Manalipa or Coco Island, Sibago, Tabtaboon a nd Boobooan. The Directory has separate entries for (a) Samboangan, ‘a small Spanish settlement on the Mindanao shore, at the North side of the strait, where water and refreshments may be procured’; (b) the Santa Cruz Islands; (c) the Channels South of Baseelan; (d) Tapeantana Island and its channel; (e) Belawn island; (f) the islands of Tattaran and Lanawan; (g) Tamook Island; (h) Mataha South Point; (i) Peelas ‘the largest of the islands that lie near Baseelan’; (j) Ballook Ballook island; (k) the Sangboy islands ‘called sometimes the Hare’s Ears’; and (l) the island of Teynga. (37)

The Directory also has a lengthy entry for the Maloza River, which it describes as having two

small islands and the village of Maloza. The river is ‘not a good watering place, for vessels not well armed’, the reason for which is recounted in an interesting footnote:

In March 1793, the Anna ’s longboat made three trips to this river for water, and twice went up to the village; the inhabitants seemed very friendly, and the fisherman we had as guide endeavoured to persuade us to land, assuring us that we would be well treated at the village, that there were only women and children in it, the men being out fishing. This apparently seemed to be the case, for few men were seen, but plenty of women came to the boat with fowls, &c. to barter with the crew for handkerchiefs, knives and trinkets. I, however, discovered from one of the boats crew, who had landed and understood the language, that there were more than 100 armed men concealed behind the bushes, and he overheard two persons appoint the time when an attack was to be made on the boat. But fortunately their design was frustrated, for like true assassins, they had not courage to make the attack, because three Europeans in the boat kept arms constantly in their hands.(38)

By the 19th century the French were also familiar with Basilan. In 1819 Zamboanga was visited by the French Expédition d'Asie under the command of Captain Pierre- Henri Philibert in his flagship, the frigate La Rhône . Philibert’s chart of the Basilan Strait is acknowledged as a source in the title of the Carta Esferica y Plano Topografico de las Yslas Filipinas produced by the cartographer Ildefonso de Aragon in Manila in 1820

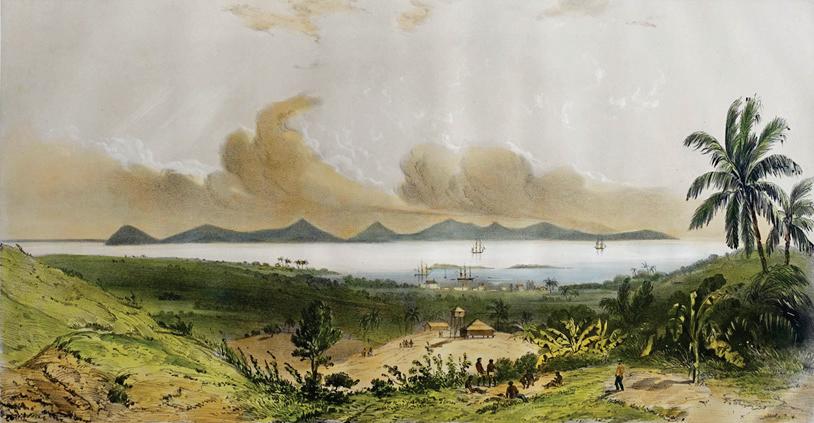

In 1839 the explorer Jules- Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville visited Zamboanga during his second circumnavigation of the world, including a voyage to Antarctica, in the corvettes Astrolabe and Zélée . The artists on the expedition produced a number of fine drawings during their stay, including a spectacular view of the Détroit de Bassilan from a vantage point above the city.The hydrographer Clément Adrien VincendonDumoulin accompanied the expedition, and his charts include a Carte de L'Archipel Solo, dated

July 1839, which shows the expedition’s track from Sulu to Basilan and through the Basilan Channel. After Dumont d’Urville’s return to Paris, the drawings were published in 1846 in the Atlas pittoresque , part of the massive 24- volume account of his voyage, (39) and VincendonDumoulin’s charts were published by the Dépôt des Cartes et Plans de la Marine.

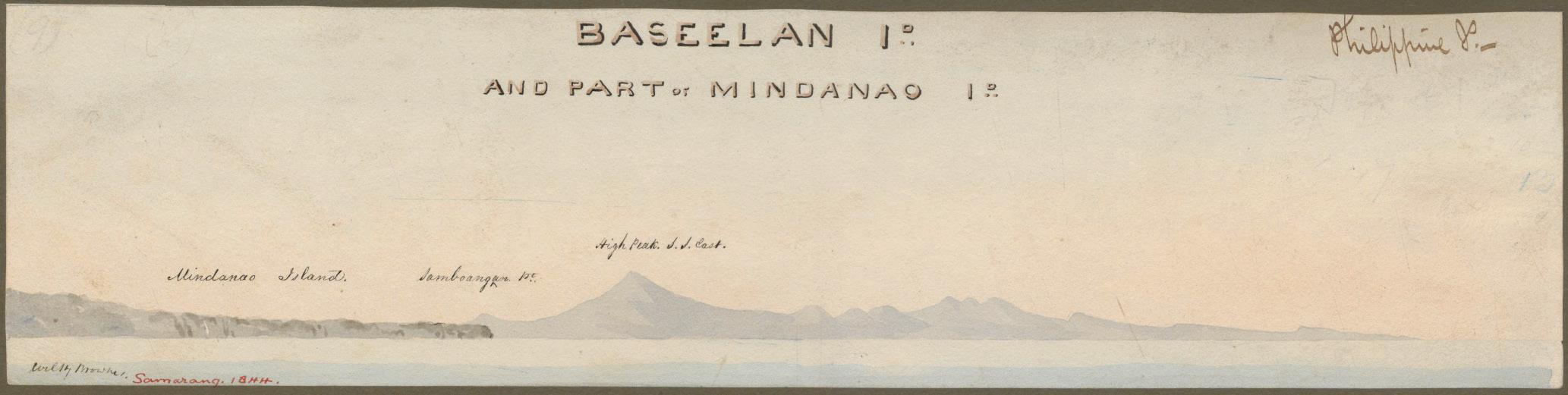

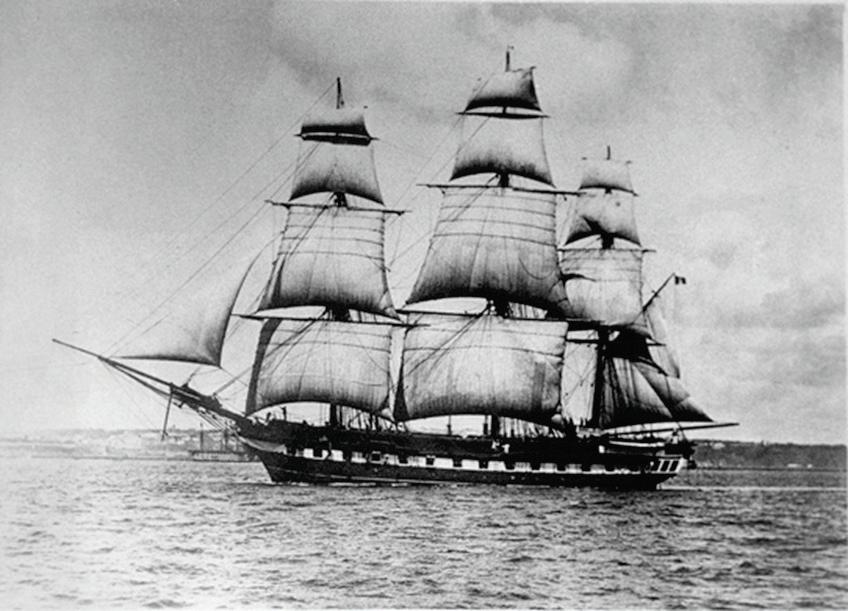

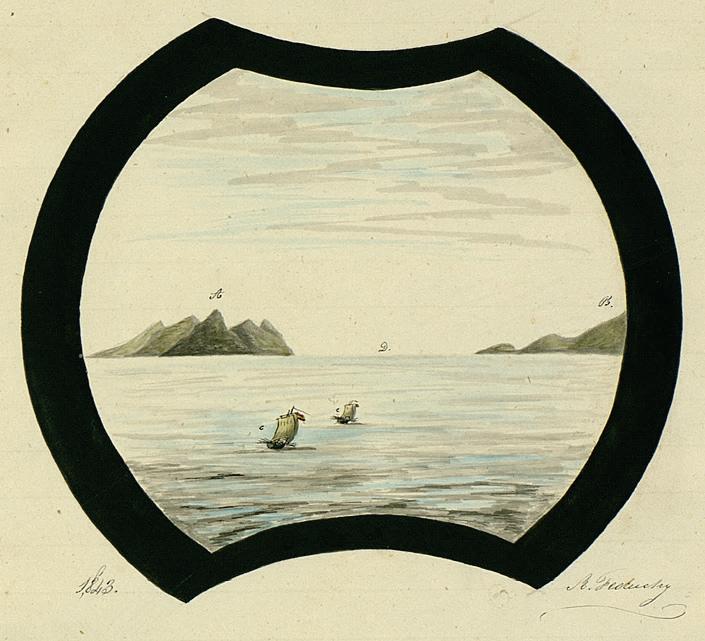

Captain Sir Edward Belcher was o ne of the Royal Navy surveyors active in Asia after the First Opium Wa r. After conducting the first detailed survey of Hong Kong in 1841, Belcher was transferred to HMS Samarang, in which ship he undertook surveying work in Borneo, Japan and the Philippines until 1846; his account of the voyage was published in 1848. ( 40) In 1844 Samarang called at Zamboanga, from where W.H. Browne, a midshipman on the ship, painted an attractive watercolour view of Basilan, with Zamboanga Point in the foreground. (41)

Samarang touched at Basilan on 21 April, 1844 and made two more visits, in March 1845 and March 1846 described below. During these visits Frank Marryat, another midshipman on the ship, made a number of drawings of local costumes and scenery that were also published in 1848. (42)

The French Blockade

In 1844 the French Foreign Minister François Guizot decided to send a plenipotentiary to China to negotiate a treaty comparable to the 1842 Anglo - Chinese Treaty of Nanking and the creation of a naval station. The Lagrené Mission, named after its head Joseph Théodose de Lagrené, obtained its principal objectives with the signing of the Treaty of Whampoa in 1844 The mission was also tasked with gathering information on Singapore, Java and Cochin China, and the search for a territory to occupy in Southeast Asia. Guizot instructed Lagrené to use ‘the naval resources at his disposal to find a favourable spot satisfying the following requirements: near the Chinese Empire, a vast enclosed port, an isolated position that is easy to defend, a healthy climate and abundant good water’. (43)

Two factors quickly narrowed the search to the southern Philippines. The first was the mission entrusted to Commander Théogène François Page in the corvette Favorite, who had concluded a trade agreement with the Sultan of Sulu on 23 April, 1843, and was especially familiar with Basilan. The second reason for the choice of Basilan was the strong support of Dr. Jean Mallat,

‘a strange character, vain and ambitious, but of rather mediocre ability’. (44) Mallat, who had spent eight years in the Far East as a merchant in Canton and as a physician in Manila, had published a preliminary work on Basilan (45) that earned him the support of the Minister of the Navy, Rear Admiral Baron Armand de Mackau. Although Mallat’s information on Basilan had been gathered from various, sometimes contradictory, sources, ‘Mackau asked him to join Lagrené’s mission as a scientific and linguistic auxiliary for the secret operations in the Sulu archipelago, [with] the official designation of ‘colonial agent’, a comfortable salary, and the promise of 200 hectares in the new occupied territories’. (46)

Jean Mallat de Bassilan (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

In October 1844 Admiral Jean- Baptiste Thomas Médée Cécille, in command of the French squadron in Asia, sent Commander Nicolas François Guérin in the corvette Sabine on a secret reconnaissance mission, with Mallat and two hydrographers on board. On 23 October the ship arrived in Maloso Bay, where ties with the local chief, Datu Usuk, were renewed. But an ‘unfortunate clash’ took place on 1 November between a shore party in search of potable water and the local inhabitants. An ensign and a sailor from the Sabine were killed, and three others taken captive. A week later Sabine was joined by the corvette Victorieuse (Commander Rigault de Genouilly), but instead of negotiating directly with Usak for the release of the captives, Guérin delivered a message vowing vengeance if the prisoners were maltreated and another ‒ signed by Mallat without authorisation ‒ announcing that ‘in the name of France … we today take possession of the Basilan Islands and its dependencies’. (47)

Guérin then headed to Zamboanga to request the intercession of the Spanish Governor, Don Cayetano Suarez de Figueroa, who was happy to help and secured the release of the prisoners in exchange for 1,000 piastres- worth of cargo and 2,000 piastres in cash. But Guérin was not satisfied. Anxious to obtain ‘compensation’ for the double killing, on 18 November he declared a blockade of the island, and informed not only the Governor of Zamboanga but the Sultan of Sulu as well. The latter declared that ‘as the people of Basilan broke away from my sovereignty, it is only just that the French punish them’. (48) On 27 November 160 men from the two corvettes mounted a retaliatory attack, which failed (with two killed and several wounded) because of the fortifications built by the islanders on advantageous ground.

Meanwhile Figueroa protested the blockade, sent armed faluas (49) as a warning, and alerted Manila. Governor- General Narciso Clavería sent the frigate Esperanza to Basilan, where it arrived a day after Admiral Cécille’s flagship, the frigate Cléopâtre , with Lagrené also on board. Although, as an experienced diplomat sceptical of acquiring a settlement in a region beleaguered by piracy, Lagrené was in favour of withdrawing , Cécille convinced him to pursue the conquest of Basilan with its ‘wonderful port’ of Malamawi. The French ignored correspondence with the Spanish authorities, and on 13 January, 1845 the Basilan chiefs, at a meeting aboard the French steam corvette Archimède , affirmed the ‘absolute independence of the island vis- à - vis Spain’. A week later they drew up an agreement whereby for the following two years they would cede the island to France exclusively, upon request:

Friendlier than Maloso’s datus , the same Balagtasan datus that had struck an agreement with the Spanish the year before explained to Admiral Cécille in January 13, 1845 that they were loyal neither to Spain nor to the Sulu Sultanate: on their way to Zamboanga, they merely used the Spanish flag, and displayed anot her one when they went to Sulu. These datus were the Panglima Tiran, his brother-inlaw Arak Tao Marayo, and Imam Baran.(50)

To resolve the issue of Sulu’s sovereignty, on 4 February the fleet moved to Jolo where the young Sultan Mohamed Pulalou ‘apparently debilitated by opium’ agreed to a conditional arrangement notwithstanding his ‘religious scruples’. (51) The agreement provided that within six months Basilan would be ceded to France in exchange for 100,000 piastres (500,000 French francs). It was signed on 20 February, subject to ratification by the king of France

However, the French navy still wanted revenge, and on 27- 28 February the fleet launched a retaliatory attack on Maluso, driving the inhabitants into the mountains, burning 150 houses, destroying the stocks of rice and the banana plantations, and chopping down the giant coconut trees. On 2 March the fleet left Sulu, with the Archimède carrying the Sultan’s letter to France, the Cléopâtre sailing to Macao with Cécille, and the Sabine returning to Manila.

Cécille tried his best to get the treaty of cession ratified, and recommended that Basilan be occupied. His report was submitted to the Conseil des Ministres on 30 June, 1845, which decided in favour of taking possession of the island and allocated the nec essary budget. But on 26 July King Louis Philippe reversed the decision because of the location, the climate and the presence of pirates and ‒ perhaps more importantly ‒ because he did not want to compromise his negotiations with Queen Isabella II of Spain with whom he was negotiating the marriage of his youngest son, Prince Antoine d’Orléans, Duke of Montpensier, to the Queen’s younger sister, the Infanta María Luisa Fernanda de Borbon.

‘ The decision was tactfully conveyed to Cecille on August 12; he was given a mission to look for another territory not within European trade routes to China but ‘around the Japan waters’. As for Mallat, on standby duty, who had miserably failed to hoist the French flag on foreign soil, he was recalled several days later. ’ (52) On 9 April, 1845 Mallat sent a furious letter from Manila to the Minister blaming Cecille, followed by a long report sent to the Minister from Rochefort on 13 May, 1846. (53) On his return to Paris, Mallat published his magnum opus, a two - volume work on the history, geography, habits, agriculture, industry and commerce of the Philippines, with lavish lithographs of local scenes and costumes and an accompanying atlas of maps.(54) He would subsequently be known as ‘Jean Mallat de Bassilan’, an honorific title that may have been granted to him by Emperor Napoleon III. (55)

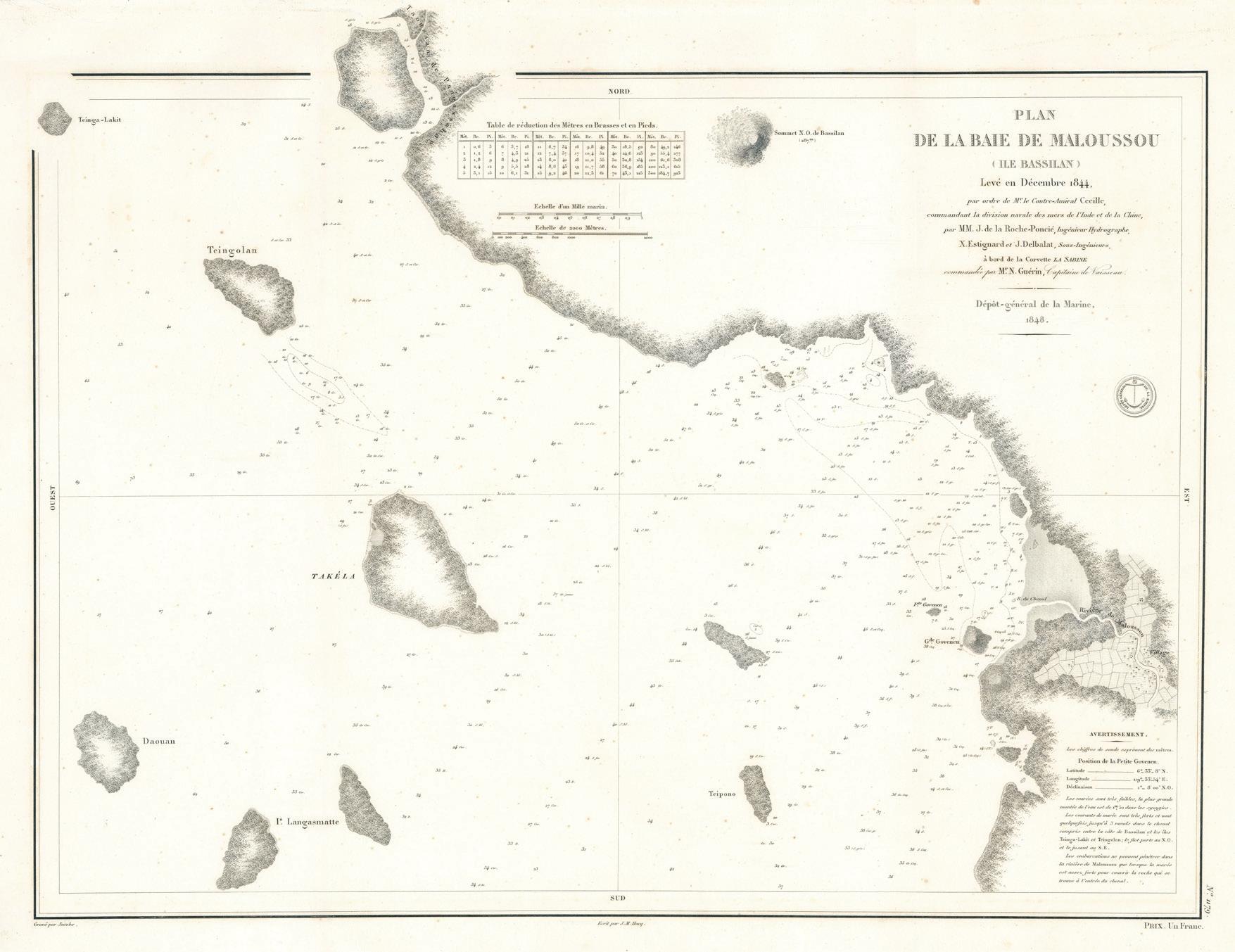

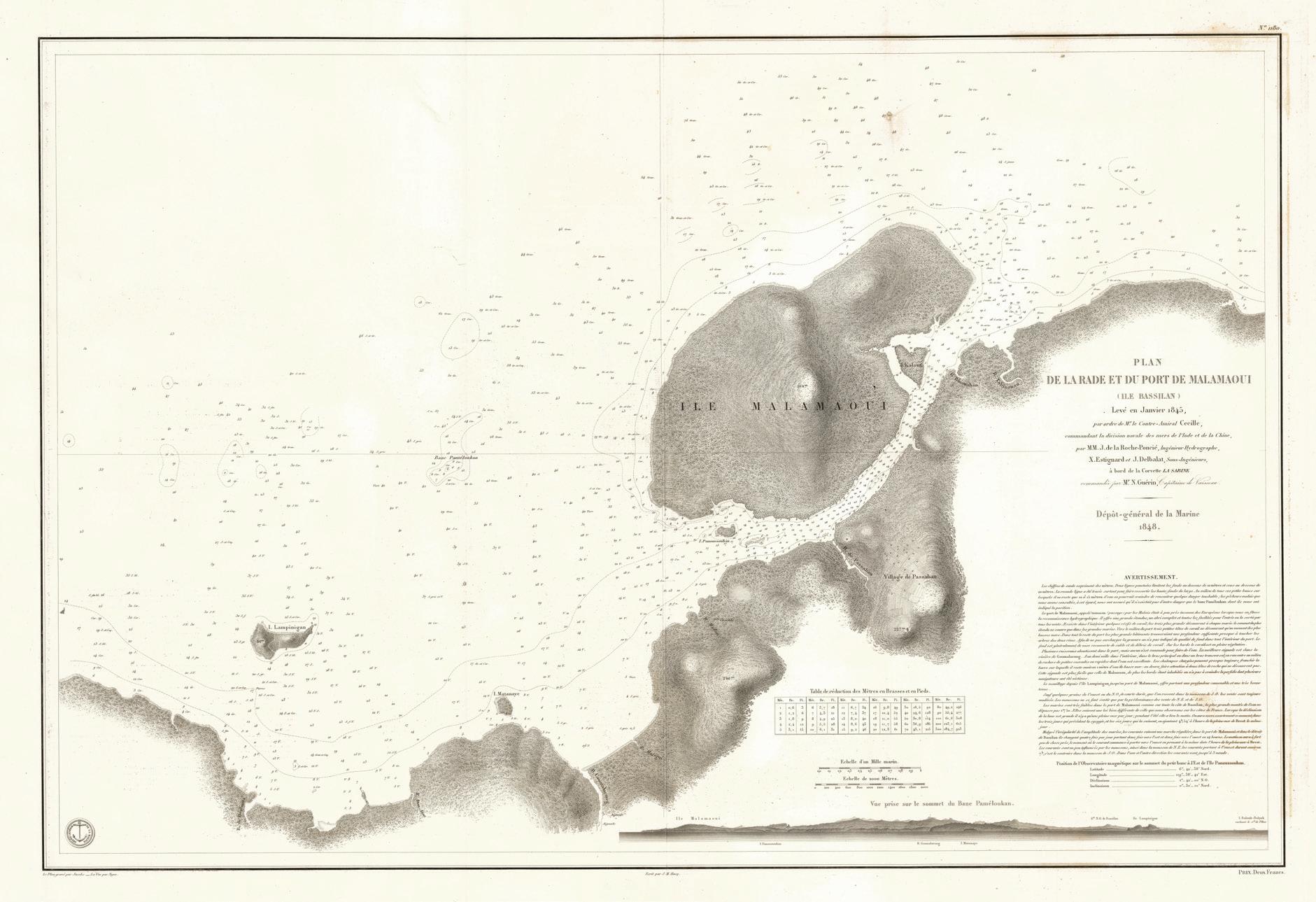

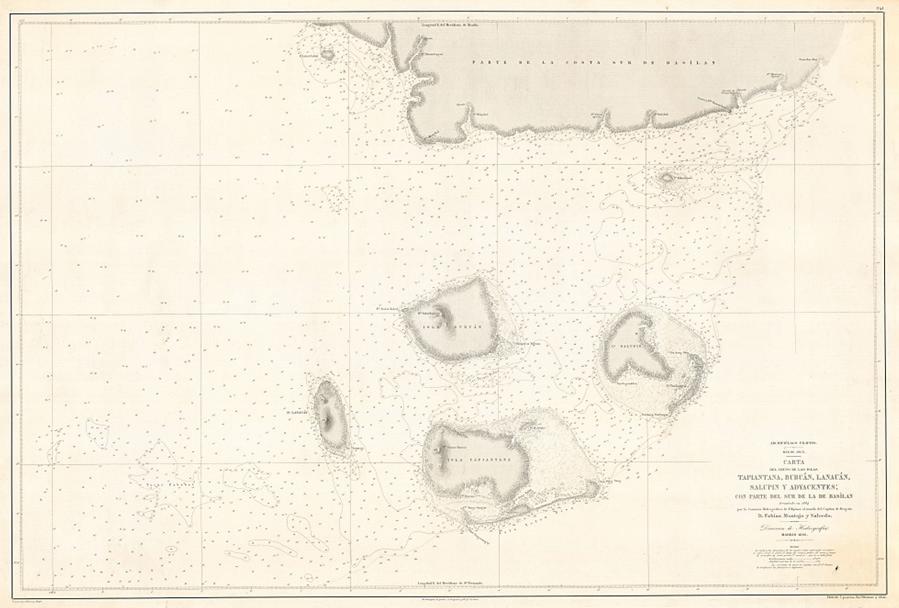

An important legacy of the French blockade were three charts of Basilan produced by the hydrographers on board the Sabine. A large- scale chart of Maloso Bay was made in December 1844;(56) a nother large- scale chart, of the rade (harbour) and port of Malamawi, was made in

King Louis -Philippe by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (Château de Versailles )

January 1845;(57) and a chart of the whole island of Basilan with its adjacent islands and the Basilan Strait was completed in 1845. (58) The charts, which show the coastlines, shoals, islands, numerous soundings, anchorages, ports, towns and villages, rivers and topography, were published by the French Dépôt- général de la Marine in 1848 and 1849, and were subsequently copied (in whole or in part) by the British Admiralty, the Spanish Dirección de Hidrografía and, as late as 1902, the U.S. War Department. In December 1844 the French surveyors also produced a chart of the Zamboanga anchorage, including the Santa Cruz islands. (59)

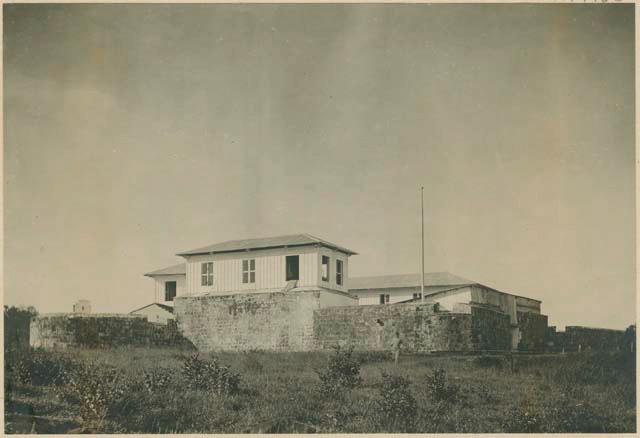

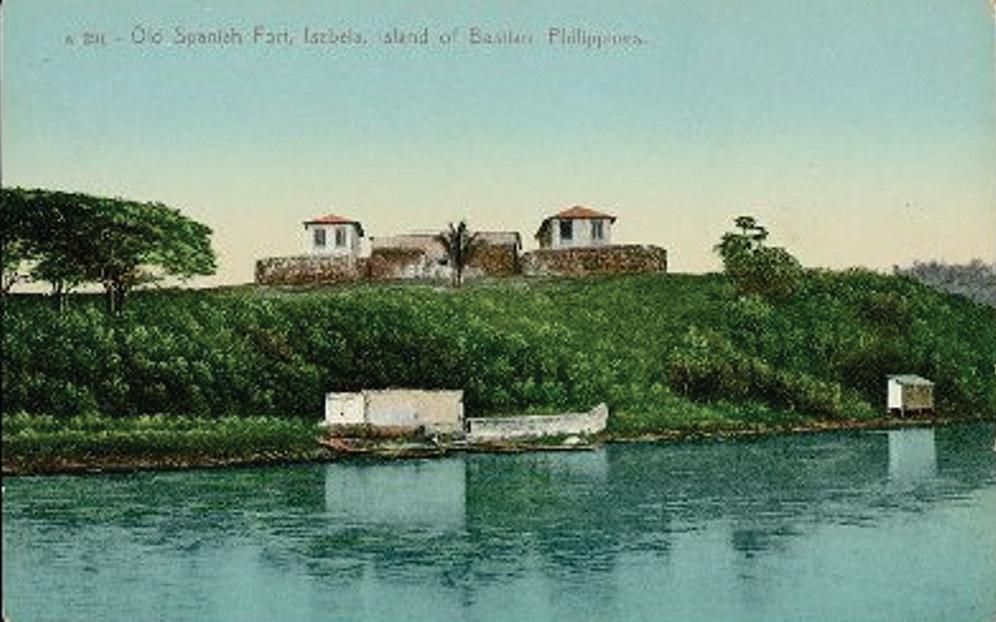

The Spanish garrison had left Basilan in 1762, during the British occupation of Manila, and did not return that century. But with the departure of the French in 1845, the Spanish reoccupied Basilan and immediately started building a fort as a defence against Tausug pirates and any further attacks by Europeans. On 10 July ‘the marine commander of Zamboanga, Mr. Ramón Lobo, and the district governor, Mr. Cayetano Figueroa, visited [Pasanhan] and gave it the name of Isabela in honour of Queen Isabella II’. (60)

Carte de l’Ile Bassilan et Dépendances Levée en 1845 , Dépôt -général de la Marine, 1849 (images courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps )

Plan de la Baie de Maloussou (Ile Bassilan) Levé en Décembre 1844 , Dépôt -général de la Marine, 184 8

Plan de la Rade et du Port de Malamaoui (Ile Bassilan) Levé en Janvier 1845, Dépôt -général de la Marine, 184 8

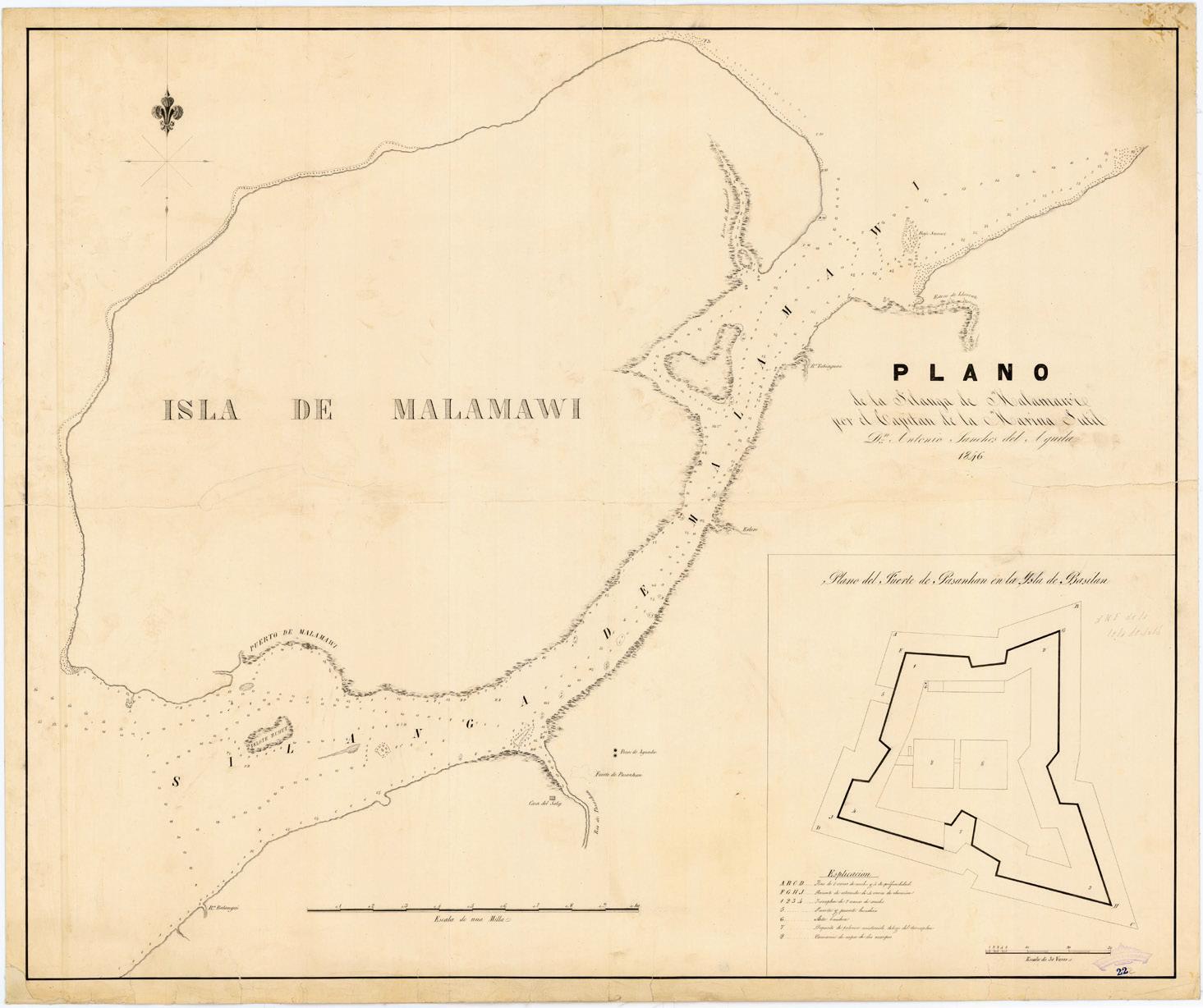

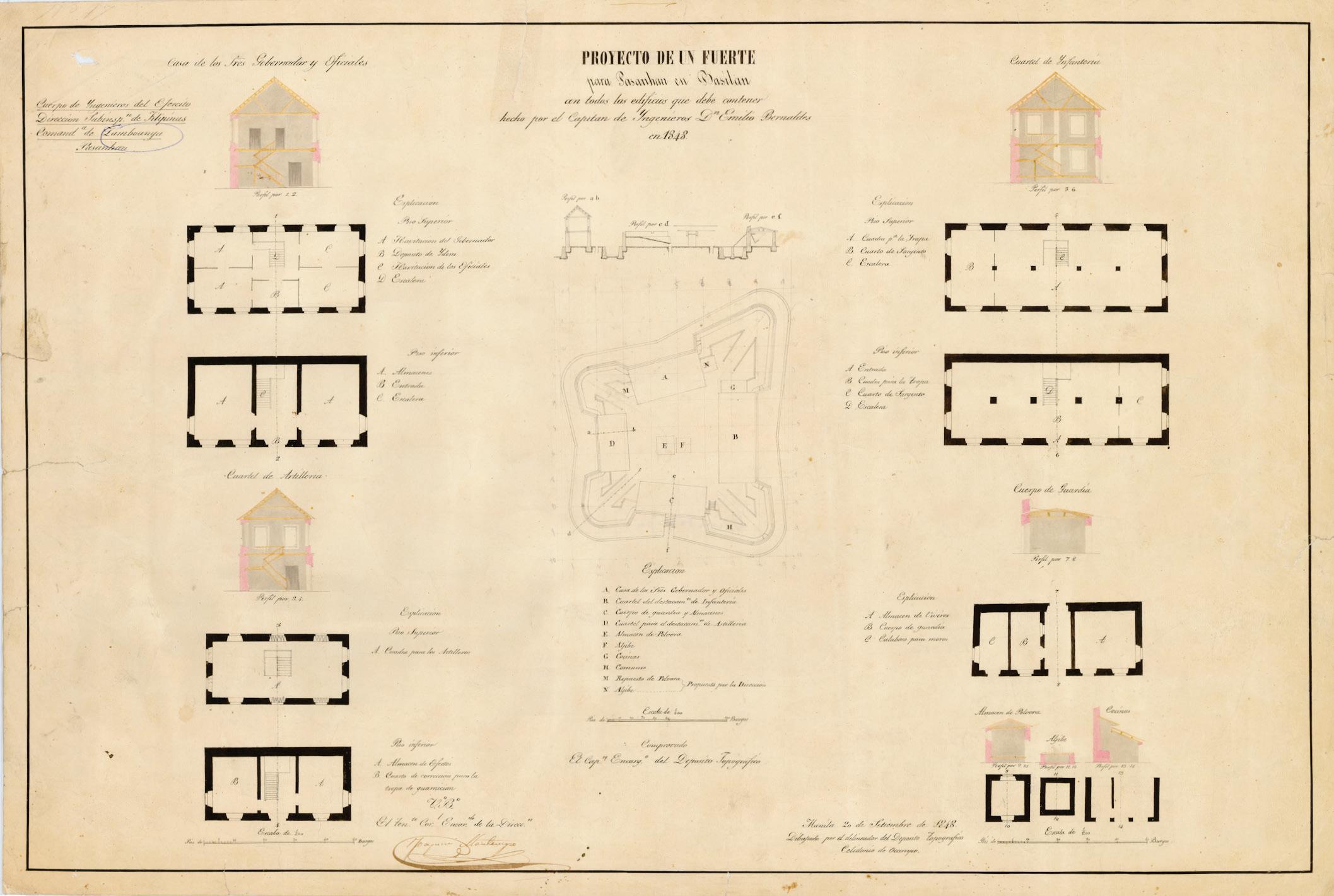

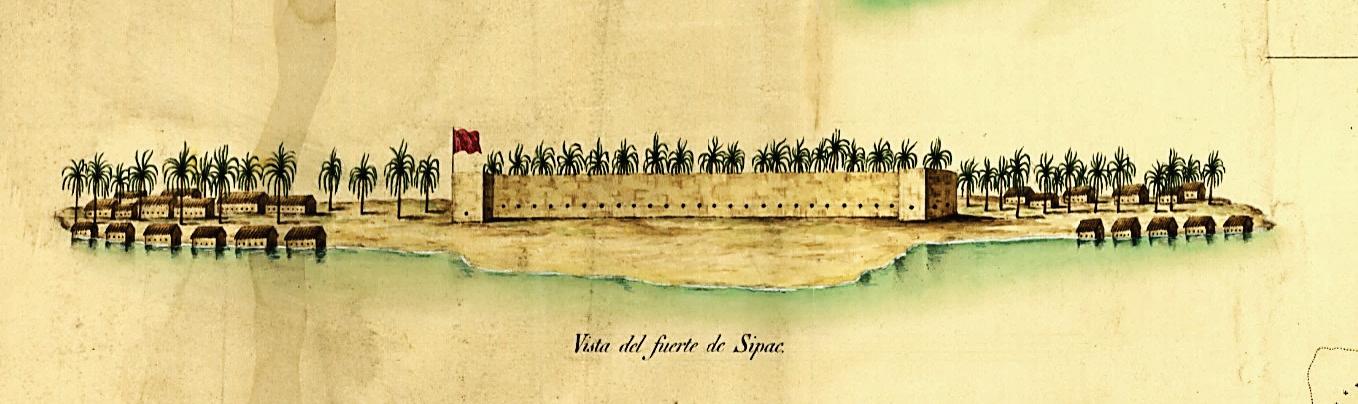

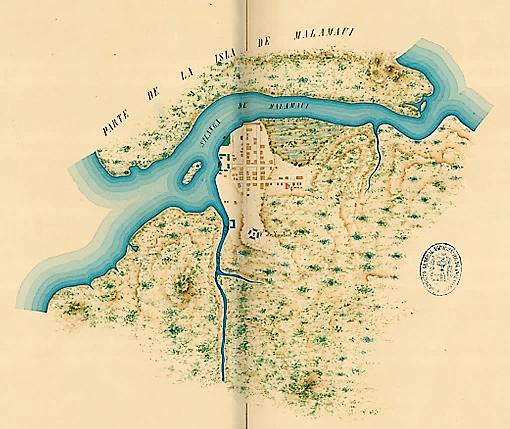

Construction of the fort followed the detailed plans and elevations made by the engineer Emilio Bernaldes, as drawn by the draughtsman Celedonio de Ocampo. (61) The plan of the fort is also shown as an inset in a map of Malamawi produced in 1846 by Capitan de la Marina Sutil Don Antonio Sanches del Aguila. (62) As well as the Fuerte de Pasanhan (the fort), the map shows the Puerto de Malamawi, north of Islote Buhut in the Silanga (channel) de Malamawi; the Casa del Salip (house of the Sheriff); the Rio de Pasanhan; and two Pozos de Aguada (wells).

Belcher recorded the fort’s construction when HMS Samarang visited in early March 1846:

On the morning of the 3rd we found ourselves off the western end of the Island of Malavi, which forms, by the canal within it, the Port of Pansañhan, a new settlement by the Spaniards on Basilan. … [After landing] I reached the entrance to a strongly stock aded fort, within the lines of which the more substantial walls of stone and mortar were in the course of erection. The Fort of Pasañhan is situated about forty feet above the sea level, and by clearing away the trees intervening, commands the two entrances on the east and west of the Island of

Malavi. The interior accommodation within the fort is intended to provide for a garrison of sixty .

Plano de la Silanga de Malamawi por el Capitan de la Marina Sutil Dn. Antonio Sanches del Aguila with inset Plano del Fuerte de Pasanhan en la Ysla de Basilan , 1846

(Archivo Cartográfico de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército )

Proyecto de un fuerte para Pasanhan en Basilan con todos los edificios que debe contener hecho por el Capitan de Yngenieros Don Emilio Bernaldes en 1848

(Archivo General Militar de Madrid )

Fresh water is scarce, but this important treasure was discovered not very distant, by one of the Officers of the garrison during our sojourn. Near the water the ground is still very swampy, but this will shortly be filled in, and in all probability form the jetties to the new town, which, if judiciously managed, may be rendered one of the most valuable ports in these seas. …

For a long period Basilan has supplied Mindanao with fruit, vegetables, cattle, poultry &c., and if the native population, which are Mahomedan, are once brought to friendly terms, Pasañhan must become the principal resort of the whalers frequenting these seas; but it should be freed from the disabilities under which penal settlements labour, and be under a separate Government, favouring commerce, and totally disconnected with Samboanga.(63)

The ship’s Assistant Surgeon, Arthur Adams, also wrote about his visit to Basilan and provides us with a view of the density and beauty of the forest before the coming of the plantations:(64)

[In March 1846] I had an opportunity of catching a glimpse of some of the scenery of the island, and thus it happened. While lying off Passan, a new establishment of the Spaniards on the island, I had occasion to visit the Commandante. … On my expressing to obtain some specimens of the Flying-Foxes, which are very numerous in the island, a little expedition was immediately planned … into the interior of the forest behind the fort.

Having advanced a considerable distance into the wood, and traversed some of the most romantic glades I had seen, even in the tropics, without observing anything but a wild pig, and a small species of civet cat, we came to the banks of a small, deep, still, dark -coloured river, with the lofty trees meeting over our heads, and crowded with pigeons. Here, as if to compensate ourselves for our disappointment in not meeting any Galeopitheci [colugo or flying lemur], we all eagerly commenced firing at the poor doves, and the result was the death of a considerable number, and among them several Vinagoes [green-pigeons] with splendid metallic-green plumage.

The ground in this part of the forest was literally over-run with a small black, agile, species of

Lycosa [wolf spiders], many of which had a white, flattened, globose cocoon affixed to the ends of their abdomens. It was most amusing to watch the earnest solicitude with which these jealous mothers protected the cradles of their little ones, allowing themselves to fall into the hands of the enemy, rather than be robbed of the silken nests that contained their hapless progeny.

While staying at Basilan, I had an opportunity of observing the animal of Ovulum volva [sea snail], in a living state. … From the foot being rather narrow, and folded longitudinally upon itself, this animal, no doubt, is in the habit of crawling upon, and adhering to, the slender, round, coral-branches, and fuci [seaweed], in the manner of certain other Ovula and many Dorididae [sea slugs].

By 1846 Basilan had become a successful trading post for Zamboanga, as evidenced by a letter dated 19 February, 1846 from Governor- General Clavería informing Madrid that on 18 January he had received news from Zamboanga of ‘the satisfactory state of the new Pansanhan Establishment on the island of Basilan, where a profitable market has been established for the merchants of Zamboanga’; the reply from Madrid conveying the Queen’s pleasure at the news is dated 3 August 1846. (65)

Balanguingui is a small, swampy island east of Jolo which became a centre of piracy: ‘ The Balangingi Samal lived … in a dozen or more villages scattered along the southern Mindanao coast, the southern shore of Basilan, and on the islands of the Samalese cluster of which Balangingi was dominant. Taosug datus increasingly retained neighbouring groups of Samal as slave raiders. ’ (66)

However: ‘ In 1848, Governor- General Narciso Clavería y Zaldúa organized an amphibious campaign to capture Balanguingui and to end the rampant piracy once and for all. He raised a substantial force comprising 19 warships and three regular infantry companies, supplemented with more vessels and auxiliaries from Zamboanga. ’(67) On 16- 22 February, 1848, the Spanish expedition routed the pirates and destroyed their forts, for which Clavería was awarded the Cross of San Fernando and made Count of Manila and Viscount of Clavería by Queen Isabella II.

Fort Isabella II was completed in 1848, and shortly thereafter Spanish troops from Isabela (with naval support from Zamboanga) attacked and razed the Tausug base at Maluso. After a failed counter- attack, wooden fortifications were built around the Maluso población (town), and the majority of the Tausug and Samal settlers opted to remain. Another attack on Balanguingui by Don Pedro Gonzalez in September 1853 completed the depopulation of the Samal islands. The leader of the Samal, Panglima Taupan, and his ally Datu Jalaban Dasido fled to Lantawan on the south coast of Basilan, where they eventually surrendered to Spanish troops in July 1857.

On 12 September, 1849 a decree was passed by the Spanish government designating the extension of the province of Zamboanga: ‘ The islands of Basilan and Pilas, their adjacent lands and the rest of that archipelago … will form an integral part of the province of Zamboanga. The head of said province will be, from December 1st, the new town of Isabela located in the port of Malamawi (Island of Basilan). ’ (68) This designation was revised in July 30, 1860 by a Royal decree creating a Political- Military Government for the island of Mindanao and its adjacent areas. The government was divided into six districts, of which ‘the sixth formed is the Spanish possessions in the archipelago of Jolo and Basilan, taking the name of the latter island’. (69)

The German ethnologist and naturalist Carl Gottfried Semper spent seven years exploring and studying the Philippines and Palau, including many of the islands. He arrived in Manila in 1858 and, after his return to Germany in 1865, he wrote extensively about his travels and the

biodiversity of the region. (70) As reported in 1898: ‘ During a residence of seven months [from August 1859 to March 1860] at Zamboanga and on Basilan, in addition to his zoological and other scientific researches, he studied the anthropology and ethnology of the Mohammedan Malays living there. ’ (71) He was fascinated by marine fauna, collected a great number of fossils in the Philippines, and wrote that ‘ everywhere on the shores of the islands [including Basilan] occur raised coral limestones [that] are continuous with the living reefs’. (72) ‘ He was especially struck with the phenomena on the islet of Lampinigan, close to Basilan, where trachytic (really basaltic) talus above high water is cemented by coral, and a waterworn cave containing a pothole exists over 20 feet above the level of the highest tides. ’ (73)

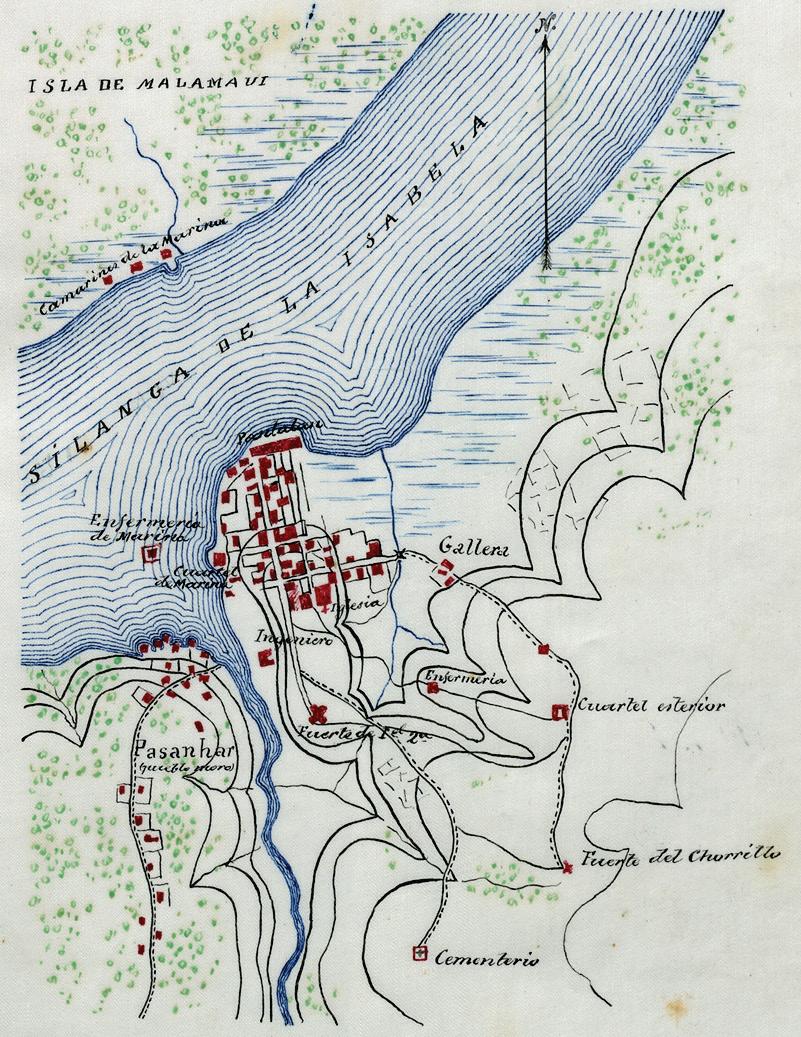

The town of Isabela grew rapidly. In 1862 Juan Nepomuceno Burriel drew a beautiful manuscript map, Recocimiento de la Isabela de Basilan, now held in the Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Map Collection at the Newberry Library in Chicago. (74) The map, at a scale of 1:10,000, shows the town of Isabela and the surrounding region, with the Camarines de la Marina (navy cabins) on the north shore of the Silanga de la Isabela. Pasanhar (sic ) is identified as the pueblo moro (native village), and across the river is the new town with a network of streets and houses between the shore and the Fuerte de [ Isabela II ]. The following buildings and locations are named: Pantalan (small dock); Enfermería de Marina (naval infirmary), offshore; Cuartel de Marina (naval barracks); Iglesia (church); Gallera (cockpit); Ingeniero (engineer); Enfermería (infirmary); Cuartel esterior (outer barracks); Fuerte del Chorríllo; and the Cementerio (cemetery).

de la Isabela de Basilan by Juan Nepomuceno Burriel, 1862 (Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Map Collection, Newberry Library )

According to Warren: ‘ In 1860 the Spanish Navy acquired 18 steam gunboats from England, to be used to repress piracy and slave- raiding. Isabela became the navy's principal steamship post in the South, and from there and Balabac nine or more gunboats regularly patrolled the Sulu Sea. ’ (75) A book published in 1876 describes the buildings of the naval station: ‘ The command house is made of wood and nipa. The [roofs of the] Marine Corps barracks, the storage rooms, kitchens, and workshops are made of nipa, and their walls are made of tabique Pampango. ’ (76)

Tabique pampango was a thin wall made of interlaced pieces of wood and bamboo and given a coating of lime mixed with sand. (77)

When the Jesuits had been expelled from the Spanish Empire in 1768 their missions (including Basilan) were assigned to the Augustinian Recollects. The Jesuits returned to Zamboanga in 1862, by when only one Augustinian missionary remained. To quote Fr. Pa blo Pastells, S.J., superior of the Zamboanga mission and a famous historian of the Philippines:

When the Recollects announced that they were going to leave the mission of Isabela de Basilan, Father [José Fernández] Cuevas was forced to appoint Father [Francisco] Ceballos to the vacant parish. Father Ceballos took over this mission on 1 December [1862], when the incumbent Recollect left for Zamboanga. From the very first moment one could see that one of the foremost difficulties about to be met within these missions was how to reconcile two duties, both equally sacred but seemingly incompatible: on the one hand the necessity for the missionary to reside in the parish which he administers, and on the other, the obligation which he has as a religious of the Society to confess frequently.

The priest of La Isabela was completely alone, even without a lay Brother to keep him company and help him. Although it was possible to remedy this latter problem quite soon, the former was not so easy to resolve because of a lack of personnel. Consequently, it

could be observed that in the case of such stations, aside from the necessary number of priests for the administration, an additional one was needed who could travel to different places either to hear the Confessions of our men, or to substitute for them on occasions like a triduum, spiritual exercises or sickness. He would certainly never be at a loss for work among the Christians and the non-Christians. Although not all rules could be observed, it can nevertheless be said that, taking into account t he special circumstances of these missions, the most essential ones were kept.(78)

Another attractive map of Isabela was produced by the Spanish Cuerpo de Yngenieros del Ejército (Army Corps of Engineers) in Zamboanga in 1880. The Plano del pueblo de la Ysabel c on el Fuerte de Ysabel 2ª en la Ysla de Basilan, at a scale of 1 : 5000, shows a grid of four main streets, houses, naval installations, the church, the fort and part of Malamawi (79)

Plano del pueblo de la Ysabel con el Fuerte de Ysabel 2ª en la Ysla de Basilan Cuerpo de Yngenieros del Ejército, 1880 (Servicio Histórico Militar)

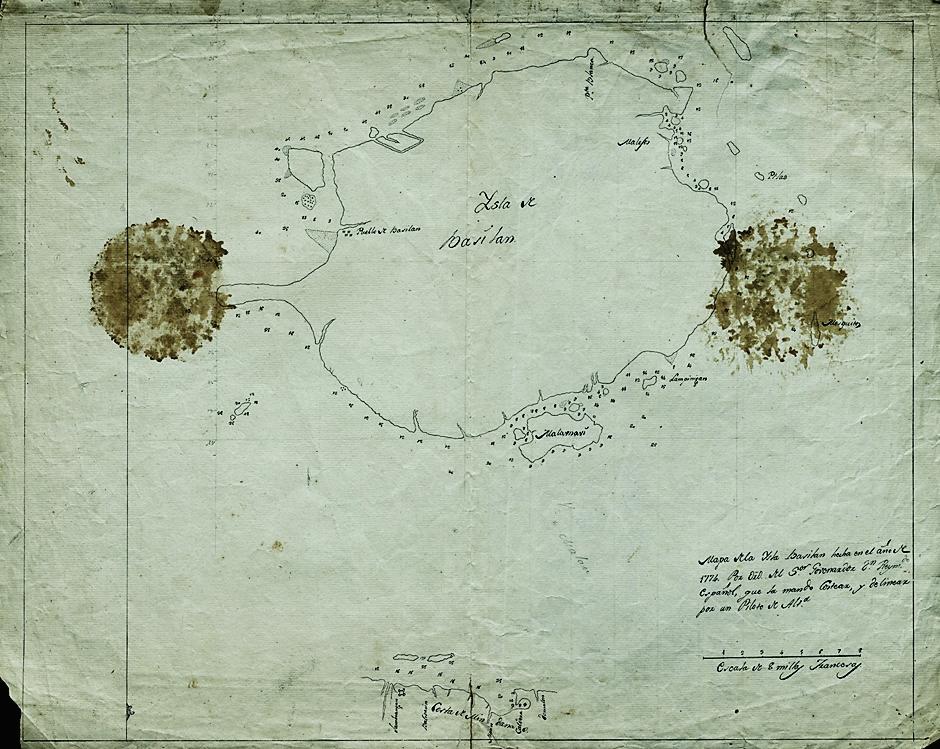

Although the first known Spanish sea chart of Basilan ‒ a manuscript chart showing soundings along all of its coasts ‒ was made on the orders of the Governor of Zamboanga Don Raimundo Español in 1774, (80) detailed Spanish charts of the area would not appear for another 80 years. The first Spanish marine charting agency, the Depósito Hidrográfico, had been founded in Madrid in 1770. In 1797 its functions were complemented by another agency, the Dirección de Hidrografía, charged with printing pilot books and engraving charts from the surveys made by the government’s hydrographic commissions. In 1854, in order to undertake new, accurate surveys of the Philippines to replace those dating back to the Malaspina expedition in 1792, the Comisión Hidrográfica de Filipinas was established under the leadership of navy lieutenant Claudio Montero, an experienced cartographer.

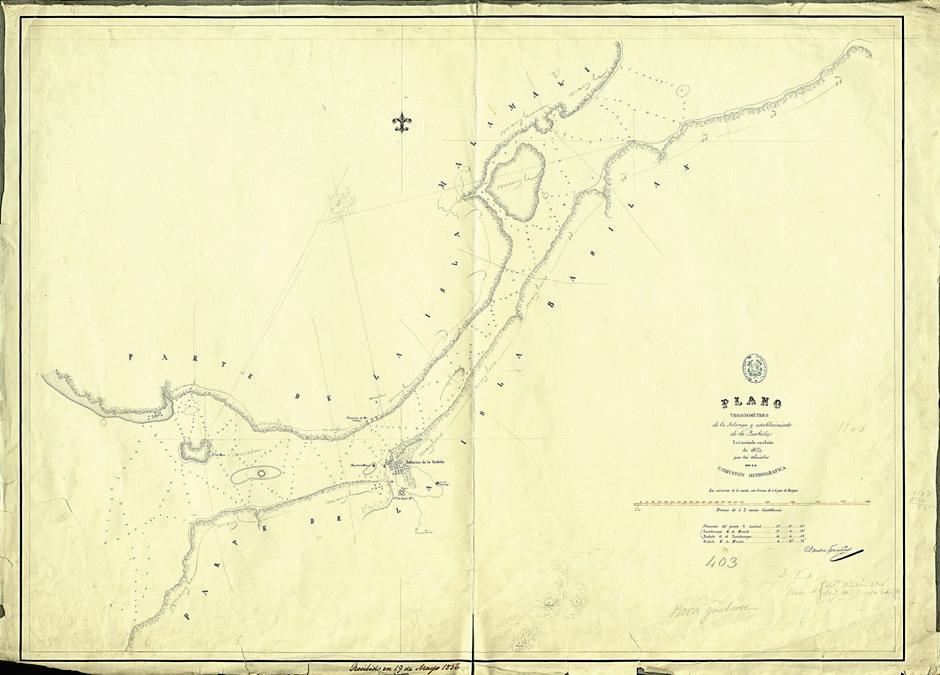

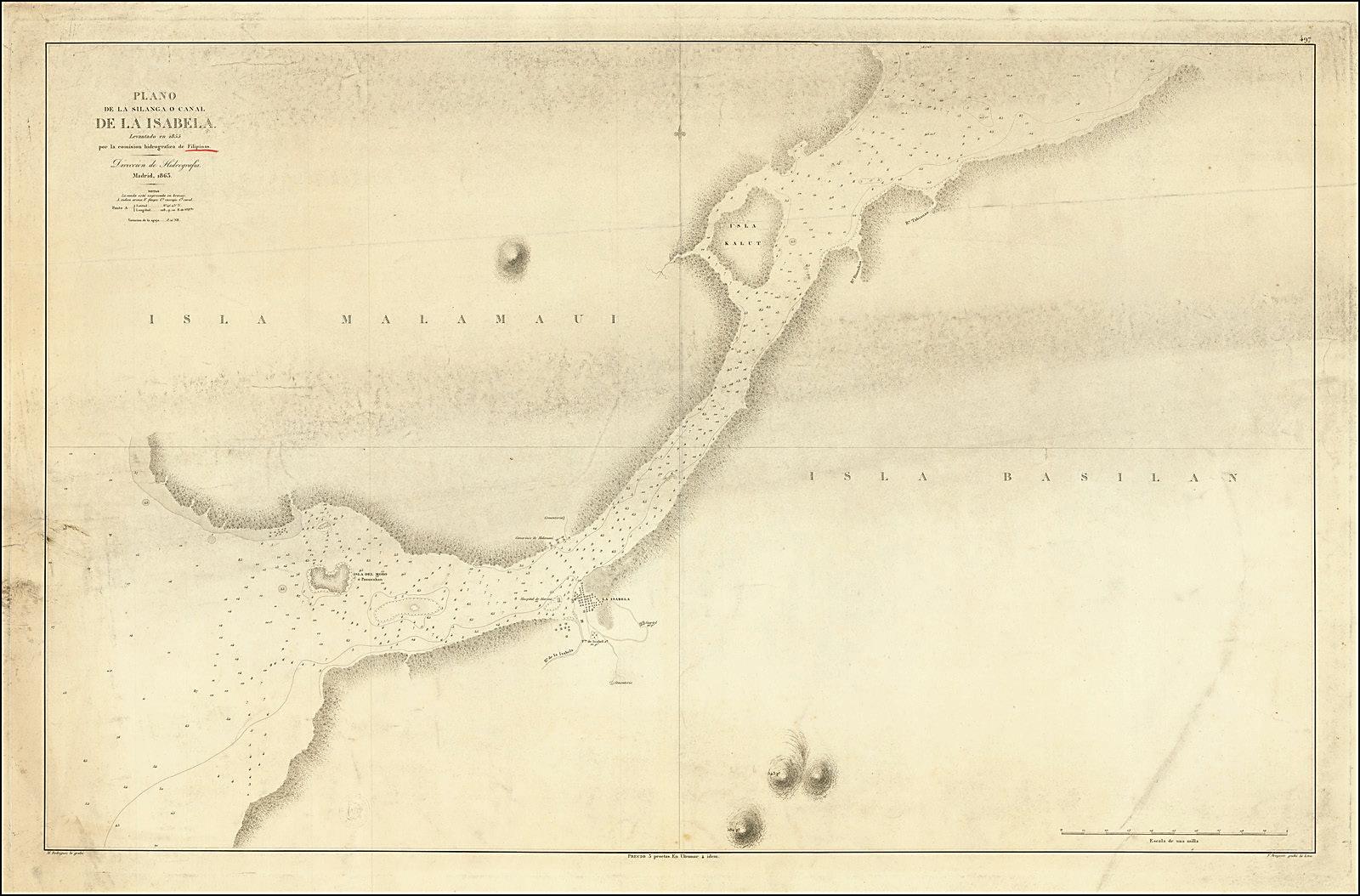

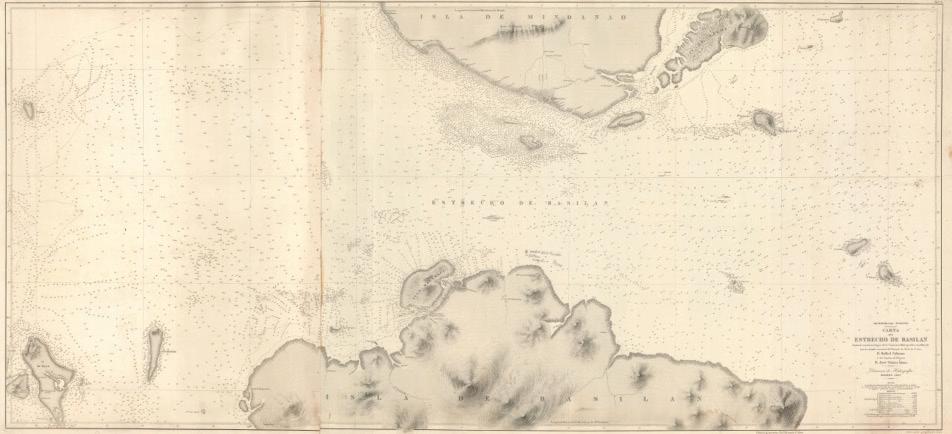

The following year Montero produced a Carta Esférica del Estrecho de Basilan L evantada en 1855, published by the Direccion de Hidrografía in 1862;(81) and a Plano Trigonométrico de la Silanga y establecimiento de la Ysabela Levantado en el año de 1855, of which two manuscripts are held in Madrid. (82) The latter chart was published by the Direccion de Hidrografía in 1863 as Plano de la Silanga o Canal de la Isabela Levantado en 1855 (83) A smallerscale chart, Carta Esférica de la Parte Sur de la Isla de Mindanao con el Estrecho é isla de Basilan, published by the Direccion de Hidrografía in 1859, specifies that the shaded coastline of Basilan Island is from ‘ el Contra- almirante Cecille en 1845’. (84)

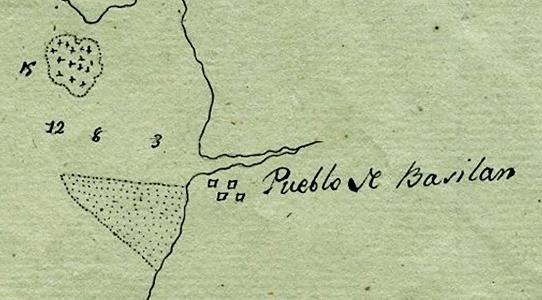

(Left) Mapa dela Ysla Basilan hecho en el año de 1774 Por Orden del S or . Gobernador Dn . Reymdo Español with (above) detail of the Pueblo de Basilan (Archivo del Museo Naval de Madrid )

In 1869 Montero was promoted to Captain and returned to Spain. The Comisión Hidrográfica de Filipinas was reorganised, but continued its work despite shortages of personnel, ships and instruments. In 1874 the Direccion de Hidrografía copied and published C écille’s chart of Malamaui. (85)

In 1879 the Comisión Hidrográfica de Filipinas produced a chart of the Pilas islands to the west of Basilan, (86) and in 1884 it produced a chart of the southern coast of Basilan with the islands Tapiantana, Bubuán, Lanauán and Salupin to its south. (87) . And in 1884- 85 it produced a much larger and more detailed version of Montero’s 1855 chart of the Basilan Strait, published by the Direccion de Hidrografía in 1887. (88) As well as numerous soundings throughout the strait and other hydrographic details, the c hart also shows the topography of the northern part of Basilan.

A feature of 19th- century marine cartography was that the various national charting agencies would cooperate and copy each other’s charts, with attribution, to ensure that seamen had the most accurate and up- to - date information. This is exemplified by British Admiralty cha rt no. 961, Sulu Sea Philippine Islands / Basilan Channel, published in February 1866, which states that it was: ‘Surveyed by Capt. Sir Edward Belcher, R.N.C.B. 1847 / The Eastern part of Mindanao is from the Spanish Chart of 1862. / The C oast in hair line is enlarged from the Spanish Chart by Coello, published 1852.’ A later edition (October 1870) does not mention Coello, but states ‘Basilan I. East of Balactassan and West of Lampinigan Land soundings from the French Survey of 1845’.

Plano Trigonométrico de la Silanga y establecimiento de la Ysabela Levantado en el año de 1855 (Archivo del Museo Naval de Madrid )

Plano de la Silanga o Canal de la Isabela Levantado en 1855 por la comision hidrografica de Filipinas , Direccion de Hidrografía, Madrid, 1863

Carta del estrecho de Basilan formada con los trabajos de la Comisión Hidrográfica en 1884 y 85 Dirección de Hidrografía, Madrid, 1887

Carta del grupo de las islas Tapiantana, Bubuán, Lanauán, Salupin y adyacentes; con parte del sur de isla de Basilan / levantada en 1884 por la Comisión Hidrográfica de Filipinas , Dirección de Hidrografía, Madrid, 1886 (Archivo Cartográfico de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército )

Basilan in the late - 19th century

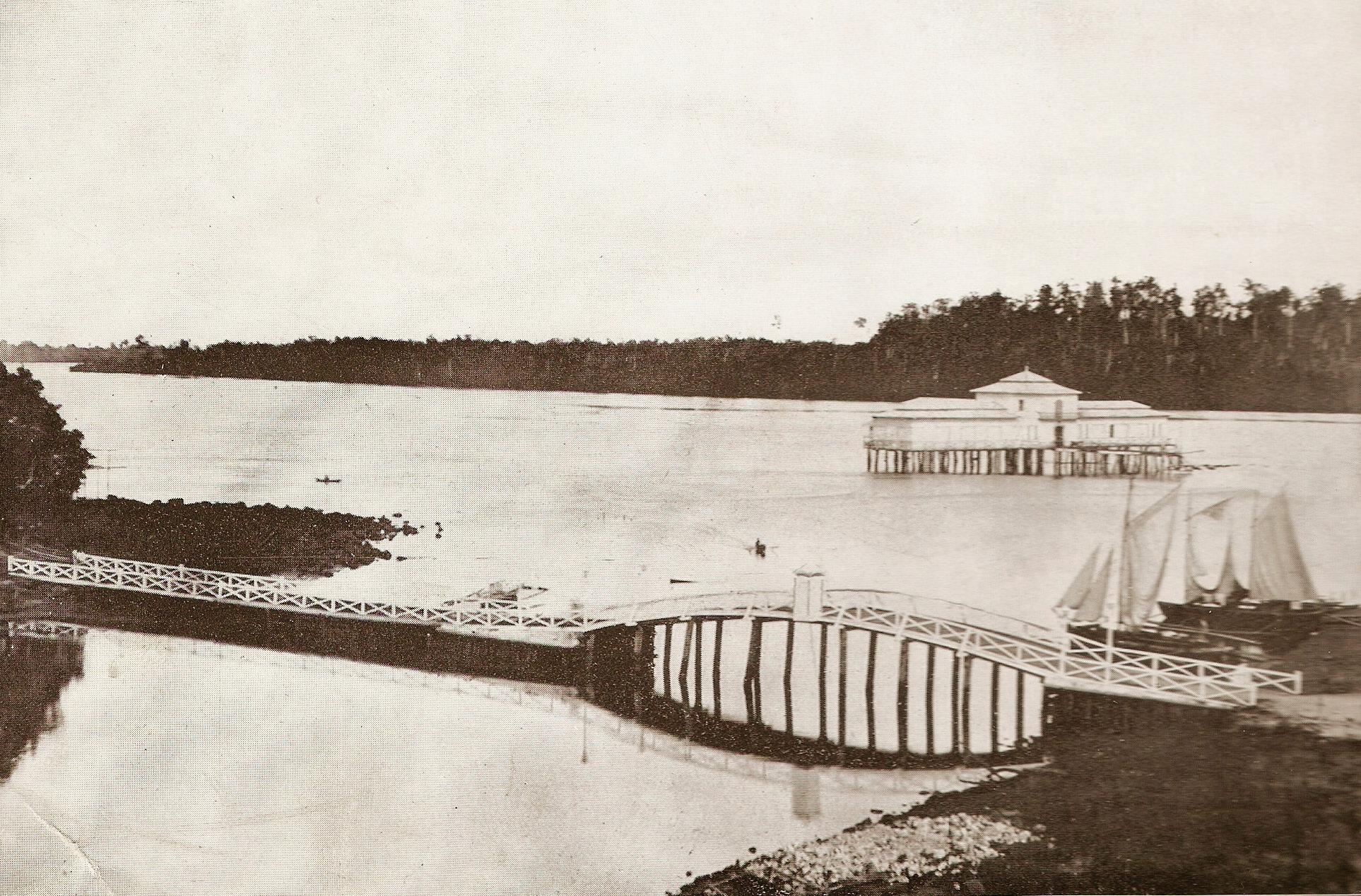

Towards the end of the 19th century Basilan became important as a coaling station for the steamships that were increasingly replacing sailing ships, notably for the suppression of piracy across the Sulu Sea. For example, on 23- 26 October, 1874 HMS Challenger visited Zamboanga during the first global marine research expedition, sponsored by The Royal Society. (89) The ship visited Zamboanga again in late January 1875, and on 3 February proceeded to Isabela to load coal. The coaling wharf on Malamaui was described as ‘merely a rough

‘wooden jetty’ , and as it was ‘difficult to find anything to which attachments could be made’ the ship was tied to a pile of ‘ large flat stones’. (90)

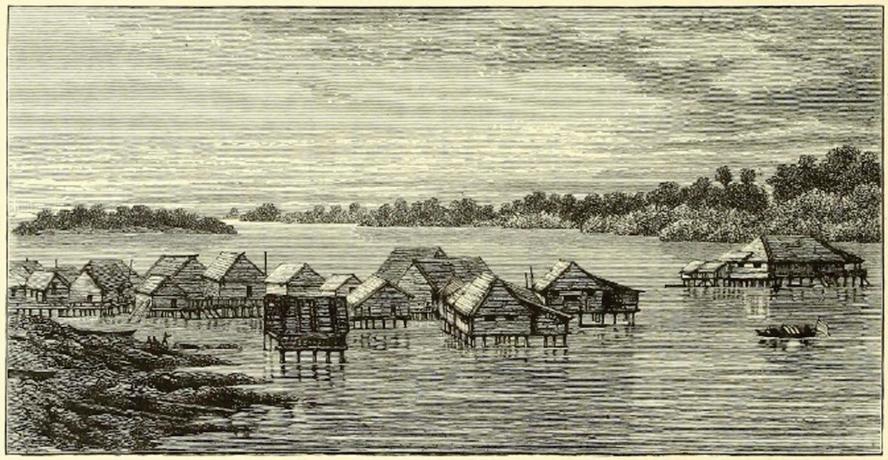

Henry Nottidge Moseley, a British naturalist who was one of the expedition’s scientists, visited Basilan and reported:

Opposite Zamboanga , across a narrow strait, was the island of Basilan, and t here a community of Moros had built houses that stood quite isolated from the shore on piles projecting from a shallow bay. They had been built close together, and many were connected by broad, ricketty gangways. The main house ‒or main part of a house ‒ usually stood on three rows of piles, and out -buildings were supported by others where needed. There was always a platform in front of the entrance to the house, and behind it might be another shelf to carry a canoe.(91 )

Libraries and Archives)

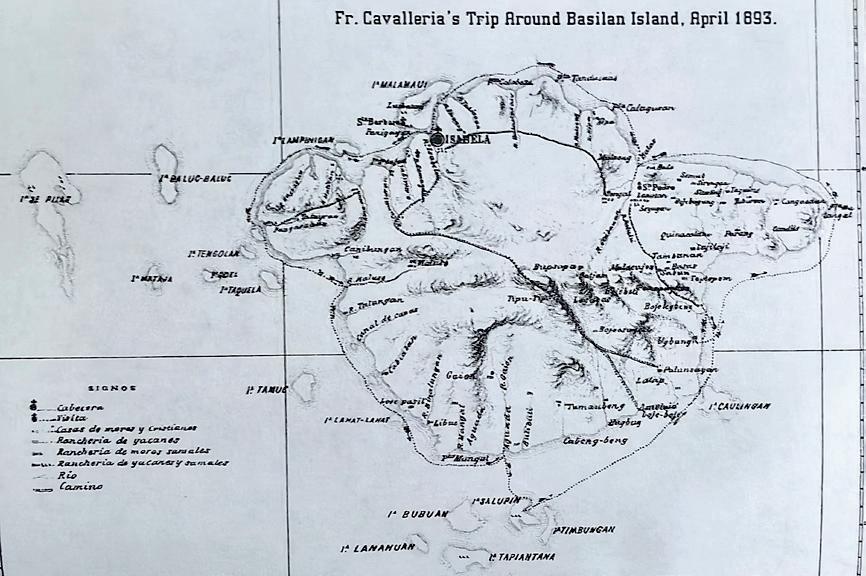

Map of Fr. Cavalleria’s trip Around Basilan

(Archives of the Philippine Province of the Society of Jesus )

On 23 August, 1891 Fr. Pablo Cavalleria, S.J., a Jesuit missionary, wrote to his Mission Superior about a trip he planned to make around Basilan. In the letter he describes the island: