SFYou: Dr. María Ignacia Barraza

The assistant professor teaches and cherishes Latin American literature

Nimmervoll • Staff Writer

Noeka

PHOTOS: Courtesy of María Barraza

PHOTO: Courtesy of Kia Porter

María Ignacia Barraza is an assistant professor in the department of world languages and literatures in the faculty of arts and social sciences at SFU. This semester, she’s teaching “Modern World Literatures 104W” and “World Literature 410,” with the special topic of Latin American Literature. Her research involves “the Spanish literary generations of 1898 and 1927, 19th and 20th century Latin American poetry and prose, as well as film and the visual arts.”

In an interview with The Peak, she tells us where it all began. Born and raised in Argentina, Barraza always held close to her upbringing surrounded by Latin American culture and literature. “I’m very proud of my Argentinian roots,” she says. When she moved to BC at 11, she was the kid with her “nose in a book.” She adds, “I always knew my vocation would have something to do with Spanish language and Hispanic cultures and literature.”

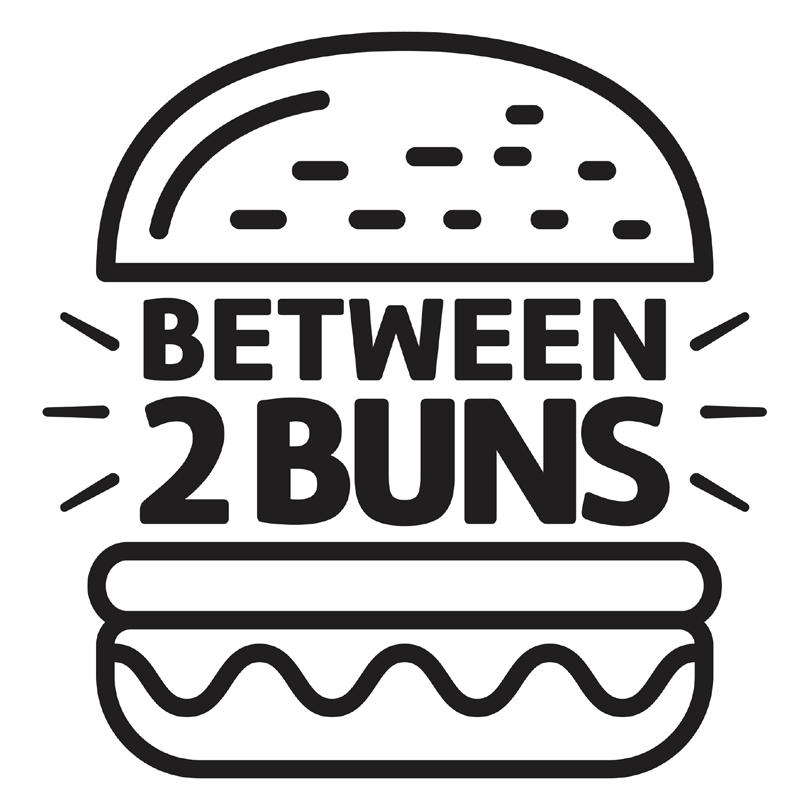

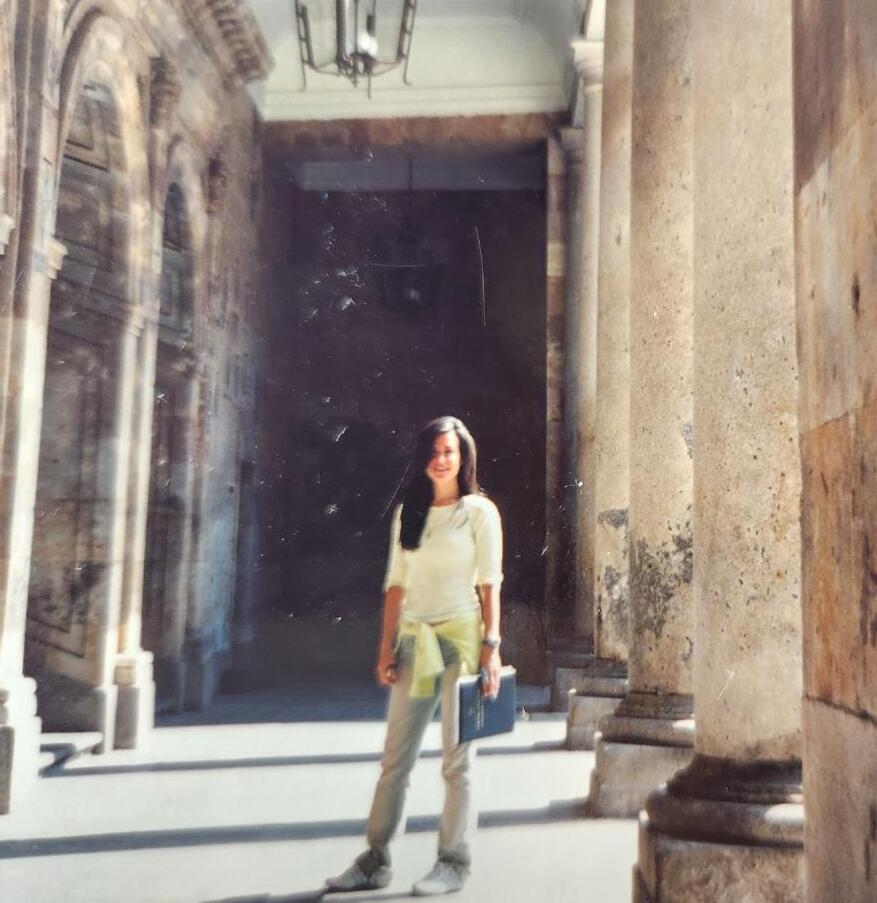

After getting her bachelor’s degree in English literature at SFU, Barraza decided to apply to the University of Salamanca in Spain, longing for adventure. “That little girl in me said, ‘You’ve got to do something to continue this search for knowledge in Latin American history and culture and literature.’” Barraza recalls how surprised she was when she was accepted into “one of the most prestigious universities” specializing in the subject.

Moving away from home at the age of 25 to pursue her education was not easy, but the immersion in Salamanca was an unforgettable experience. “I was very family-oriented, very Latin American in that sense, but I moved away on my own.” She never regretted taking that leap of faith for her education, either: “I encourage anybody who has that little voice in their head or heart that is telling them, ‘This is what I think I want to study’ — follow it.”

While Latin American literature wasn’t offered as a course when she studied here, Barraza now highlights Latin American literature for SFU students. “The Latin American ‘boom,’ perhaps, is the most exciting for me,” she says. “That’s when the world started to pay attention” to Latin American authors. This period began in the 1960s, in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution of 1959, and lasted until the 1970s. Barraza explains this was a period characterized by political themes, which included many “writers who were very much on the side of the Cuban Revolution” and efforts to uplift marginalized voices. Authors of the “boom,” which was notably dominated by men, began experimenting with writing techniques and produced many great works.

That little girl in me said, ‘You’ve got to do something to continue this search for knowledge in Latin American history and culture and literature.’

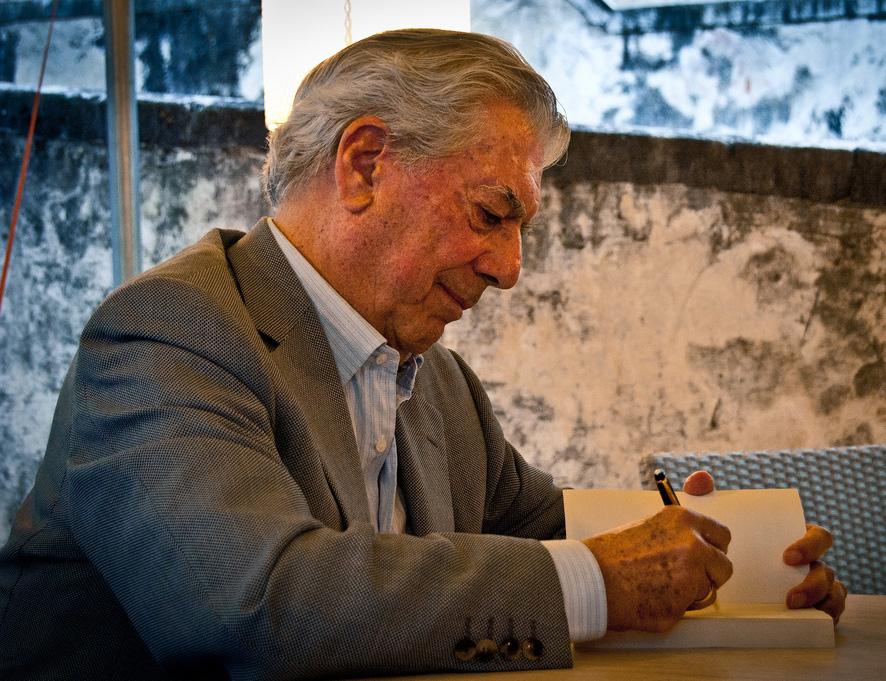

The literature as a whole was highly imaginative, often exploring time as non-linear, incorporating multiple narrative perspectives, and using magical realism, the defining genre of this time and another of Barraza’s favourites. First used by Cuban author Alejo Carpentier in the 1940s, magical realism employs elements of surrealism and otherworldliness within realistic settings. When authors such as Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru), Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia), Carlos Fuentes (Mexico), and Julio Cortázar (Argentina) became global celebrities (“wearing cool sunglasses,” Barraza quips), it marked a period of expansion of the literature and culture of the time.

However, Barraza cautions against the tendency for the “boom” to be presented as the “peak” of Latin literature. The periods that came before are just as fascinating, and not representing them is “misleading.”

The seeds of the “boom” and magical realism started long before. As a pushback against colonial narratives, modernismo was born. Modernismo was a 19th century movement that emerged from the desire of Indigenous Latin Americans to have a distinct artistic voice, free from Spanish colonizers and “colonial literary legacy.” Inspired by European literary movements of romanticism, parnassianism, and symbolism, modernismo highlighted the Latin American perspective.

Teaching Hispanic literature in the world literature and languages department requires translating the texts to English. In the classroom, Barraza highlights “the way that texts travel

and change and are accepted.” Sometimes, she will place the Spanish and English texts side by side and discuss the implications of the translation.

In personal reading, Barraza always goes back to the original text. “There’s something about the musicality of Spanish, especially in poetry,” she reflects. The 19th century Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío, considered the father of modernismo, is an author whose work she reads aloud to her students in the original Spanish. She tells them to close their eyes and listen to the ornate language. “Most of them don’t speak Spanish, actually. But it’s about the emotional impact of poetry and literature that students feel,” she says.

Barraza also reflects, “I think it would be wonderful if, moving forward, SFU could continue expanding options for students — for instance, creating opportunities for interdisciplinary work across different units. That way, students can gain a broader understanding of the region in all its richness.”

Barraza takes care to note that Latin Americans are “a mixed culture, mixed people, both racially, but culturally, linguistically, even religiously.” She adds that she tries “to give students an idea of the complexity of it all.”

One of Barraza’s joys of teaching is “highlighting obscure, unknown authors.” She mentions Oliverio Girondo, a 20th century Argentinian poet who published seven books in his life, using surrealism and “weird” imagery tied to the ultraism movement. He was a vanguardist, one of the avant-garde innovators who broke away from artistic traditions of the time. “Highlighting him and bringing him to my students, I see them get excited about authors that they’ve never heard about. And that makes me super happy,” she gushes.

The Peak asked Barraza for her recommendations:

Magical realism

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez is canonical for a reason, as it’s “hands down” Barraza’s favourite in this genre. The story follows a town’s turbulent history, told through the lives of seven generations of the Buendia family who have been there through it all.

Latin classic work

The poetry of Rubén Darío, who Barraza vows “every student should read.” Specifically, she recommends his poem “To Roosevelt,” written in 1904. The poem marks the time when the Panama Canal was being built in the US. “It’s so relevant today with the whole Trump and the US and expansionism. It’s as if he wrote it two weeks ago,” she says.

Underrepresented authors

Barraza adores the Cuban Juana Borrero and the Uruguayan Delmira Agustini, who brought themes of sensuality into the modernismo movement.

Oliverio Girondo’s early 20th century poetry collection Scarecrow and Other Anomalies “is guaranteed to make you feel less alone,” according to Barraza. “He is one of my favourite poets, yet remains little known beyond the Hispanophone world. You won't regret reading him!”

Contemporary authors

Laia Jufresa, and her book Umami: a story of private griefs in a Mexico City neighbourhood. The Argentine Samanta Schweblin’s short stories are also a favourite.

While she won’t be teaching the selected topic on Latin American literature next semester, Barraza always includes Latin American texts in her courses. In Spring, she’ll continue teaching Modern World Literature 104W, as well as World Literature 400: Early Literary Cultures.

PHOTOS: Daniele Devoti / Wikimedia Commons and Bernard Gotfryd / Wikimedia Commons

Carlos Fuentes (top) and Mario Vargas Llosa (bottom)

Many of the stories told in the documentary were deeply personal, with several of the children of this community — now Elders — recounting their struggle with identity, racism, and belonging due to their mixed-race heritage.

The Handmaiden is filled with both the subtle and the grotesque, juxtaposing tenderness against violence.

LESBIAN POWER

Need to Know, Need to Go

Explore the various histories and cultures of Latin America

LUCAIAH SMITH-MIODOWNIK · NEWS WRITER

COMIC BY SOFIA CHASSOMERIS

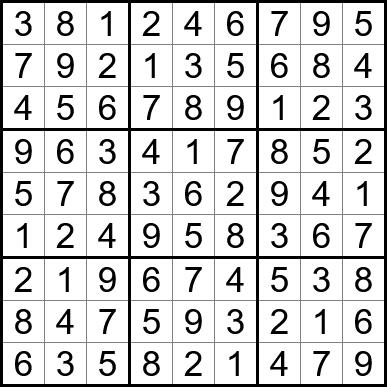

SUDOKU