08

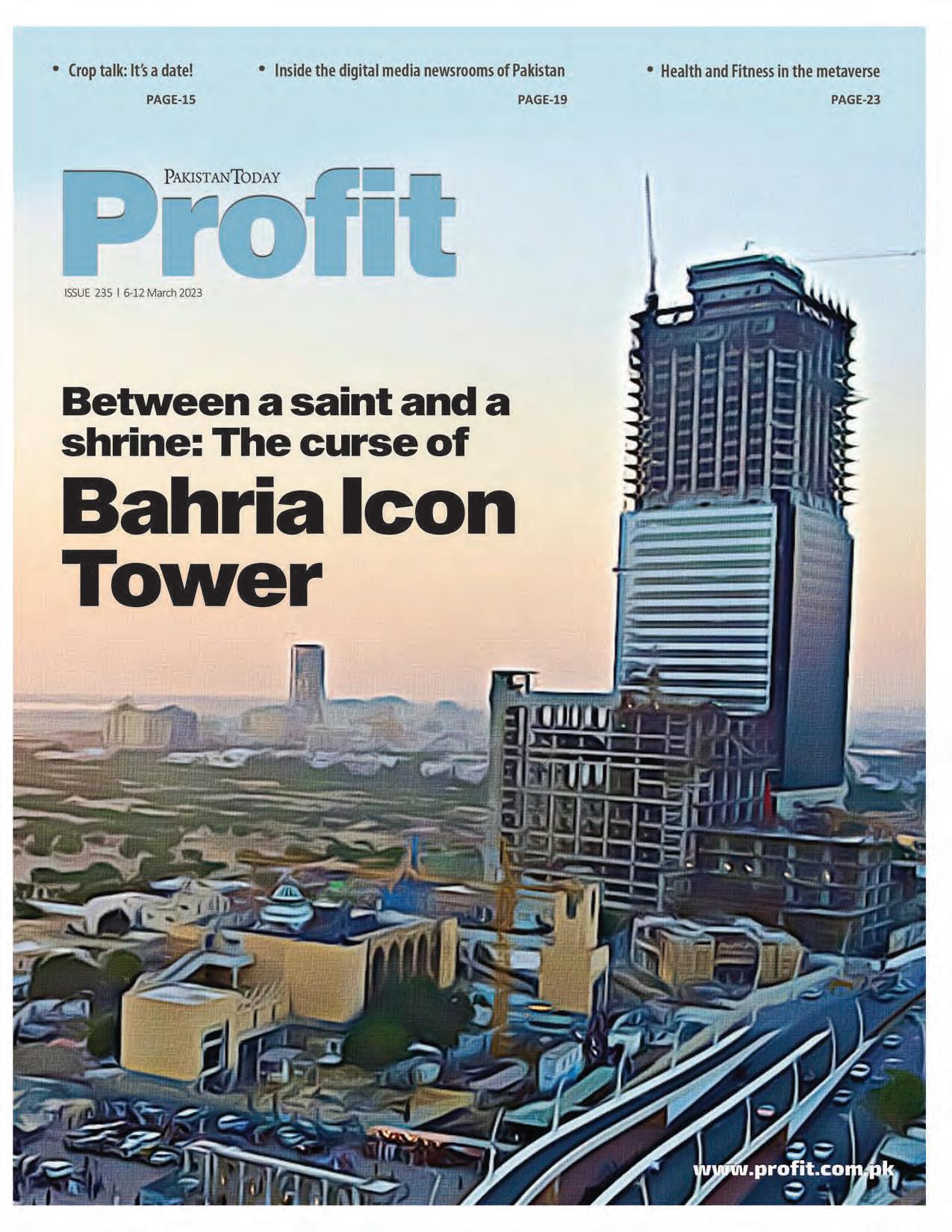

08 Between a saint and a shrine: The curse of Bahria Icon Tower

15

15 Crop talk: It’s a date!

19 Inside the digital media newsrooms of Pakistan 23

23 Health and Fitness in the metaverse

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi I Sabina Qazi

Chief of Staff & Product Manager: Muhammad Faran Bukhari I Assistant Editor: Momina Ashraf

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Ariba Shahid I Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani l Muhammad Raafay Khan

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad | Ahtasam Ahmad | Asad Kamran l Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

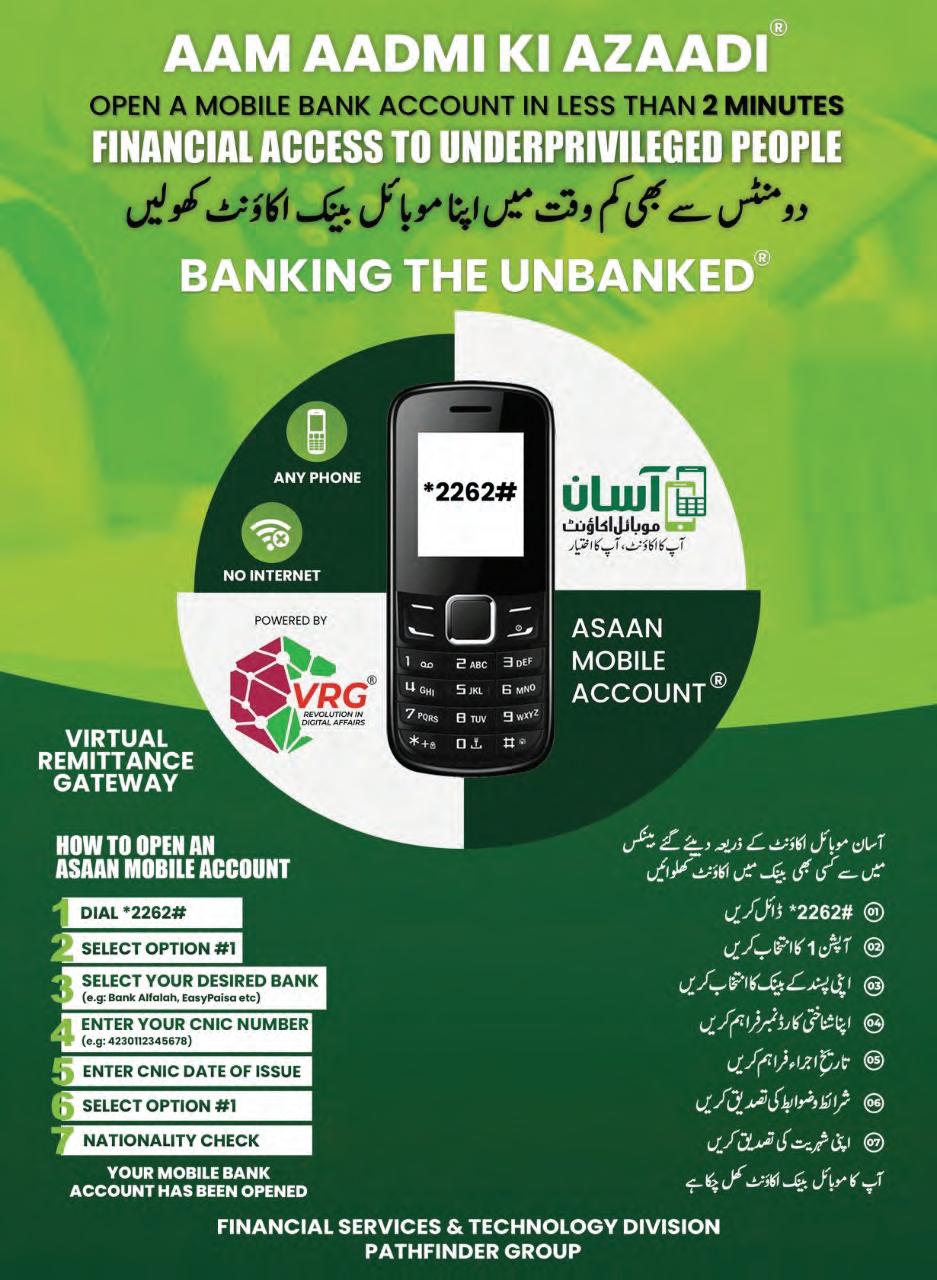

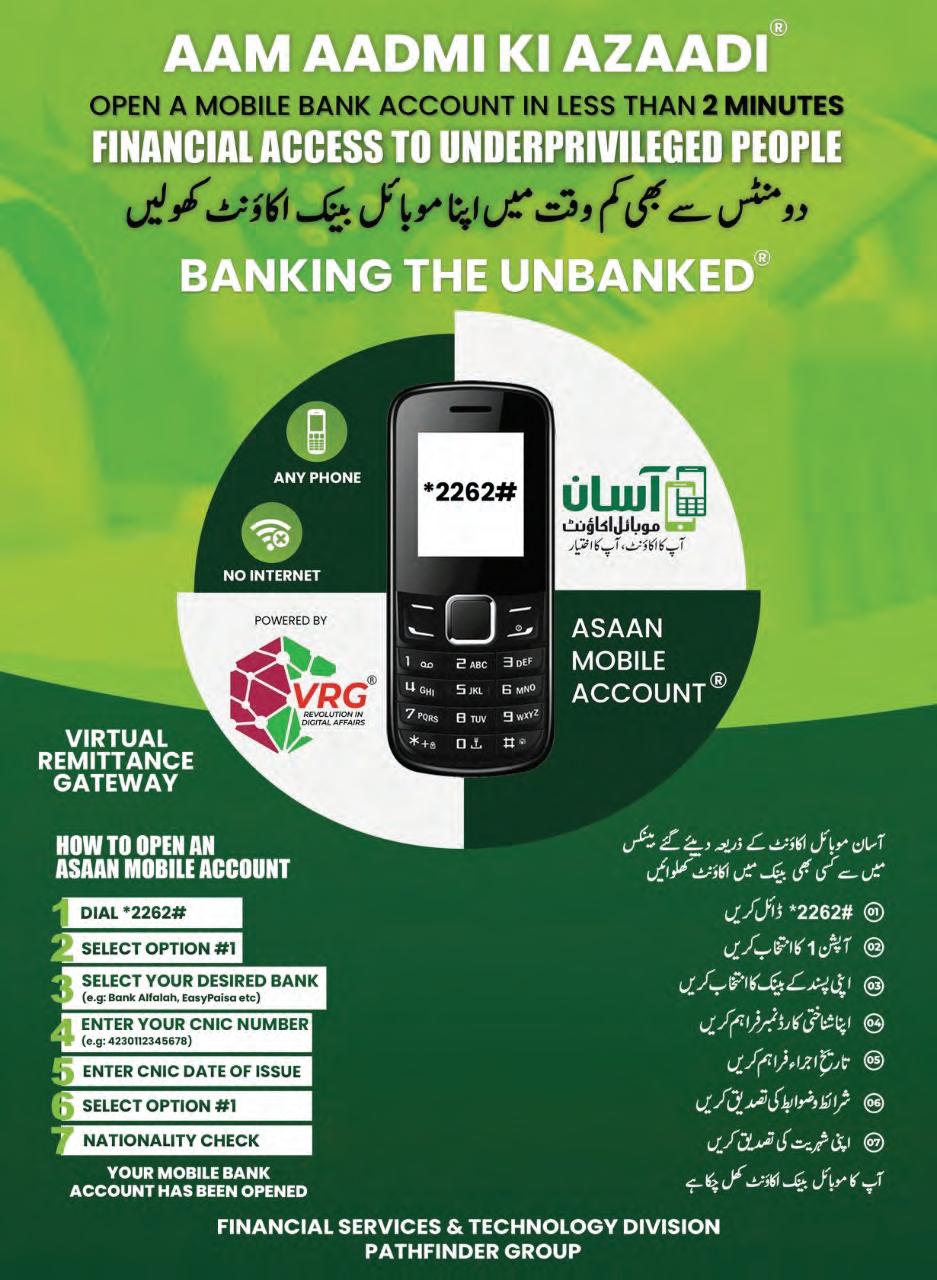

OPEN A MOBILE BANK ACCOUNT IN LESS THAN 2 MINUTES FINANCIAL ACCESS TO UNDERPRIVILEGED PEOPLE

HOW TO OPEN AN ASAAN MOBILE ACCOUNT

1. Dial *2262#

2. Select Option #1

3. Select Your Desired Bank (e.g: Bank Alfalah, EasyPaisa, etc)

4. Enter Your CNIC Number (e.g: 4230112345678)

5. Enter CNIC Date of Issue

6. Select Option #1

7. Nationality Check

Karachi’s patron saint Abdullah Shah Ghazi has been protecting the city from the wild whims and wishes of the Arabian Sea ever since he arrived here as a horse trader in 8 century CE. Sitting atop a hill near the coast, Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s mazar has long served as both landmark and talisman for an entire city. Yet today, it is the saint that needs protection from unbridled real estate development and commercialisation.

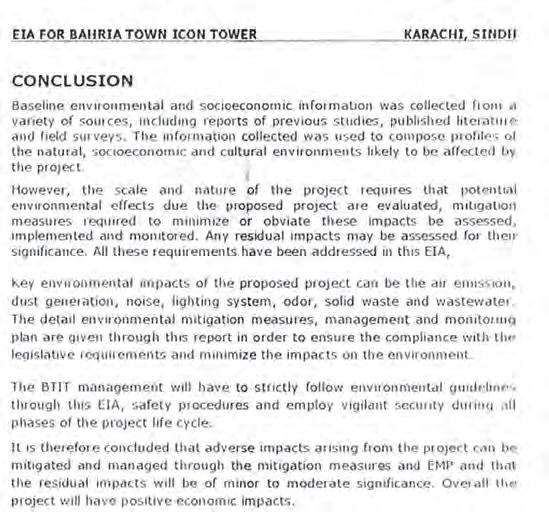

Looming large over the shrine is the Bahria Icon Tower. Billed as Pakistan’s first skyscraper it is a 62-storey tall high-rise project owned and operated by real estate mogul Malik Riaz Hussain’s Bahria Town Group. Gigantic, equipped with a seven-story basement parking, and the tallest building in Pakistan the Bahria Icon Tower is also a ghost-town. And Profit has it on good authority that the meg-project is up for sale but is having a hard time finding

Launched in 2009 the project has undergone a number of controversies and has been on hold since 2021. Once a pet project of Malik Riaz, the tower has in its 13-year history been the subject of court case upon court case. The key dispute is over the four-acre plot upon which the 938 feet tall tower stands. According to a reference in the accountability court, the tower has been built on illegally sold government land. On top of this, there have been serious concerns about its impact on Karachi’s cultural heritage because of the sensitive nature of its location next to a religious shrine, and its role in the ecological deterioration of the Karachi seafront.

So what will become of Pakistan’s tallest building? According to sources close to Bahria Town, back in 2021, Malik Riaz stopped development on Icon tower and started the hunt for a buyer. However, Bahria Town immediately faced two issues with this plan. The first was that there were no real buyers for such a massive project. Banks that might want to buy it as an office building would have trouble because it is a multipurpose residential/commercial structure. The second problem was that even if a buyer had miraculously appeared, the project could not be sold because of all of the pending court cases it was caught in the middle of.

Essentially, the legal quagmires that surround Pakistan’s tallest building mean that such a sale is next to impossible. So is the Bahria Icon Tower too tainted to find any takers? If it is, then how will Malik Riaz and Bahria Town get rid of this thorn in their back? And if the project does continue, how will local residents, investors, and municipality officials deal with such a possibility? Profit

looks at the origins and story of the Bahria Icon Tower. How it came to be, what the problems surrounding it were, and whether it will ever get up and running or not.

When Malik Riaz first envisaged the Bahria Icon Tower there was only one thing on the agenda: It had to be BIG. The icon tower is quite different from any other real estate project that has the Bahria Town stamp on it. In his decades in the real estate business, Malik Riaz has created his own unique brand of development. In an ‘Aik Din Geo Ke Saath’ interview with Sohail Warraich, Mr Riaz explained that the ‘European’ inspiration behind many of his housing projects is a calculated decision that has proven successful in the Pakistani market.

“We go to foreign countries, we see what they have done, we steal the idea and we bring it here,” Riaz said with candour. “That is all there is. Like I just saw the Eiffel Tower recently, so we imported a replica from China and everyone loves it and comes to Bahria Town from far away to see it.” Largely speaking, the success of Bahria Town has been based on ruthlessness, unrelenting tactics, and a complete lack of originality or imagination that makes their projects safe and familiar in many ways.

But the Bahria Icon Tower went against the grain. While a high-rise apartment and commercial building was nothing new to Karachi, it was an ambitious plan particularly for 2009. According to an Environmental Impact Assessment report from the project’s early days, the multi use commercial building project spanning 60 floors with 59 floors of office space and seven levels of basement parking would be completed in 2012 at an estimated cost of Rs 20 billion. Designed to be one of the tallest buildings in South Asia and by far the tallest in Pakistan, the Bahria Icon Tower was a pet-project for Malik Riaz and one that went against the typical Bahria Town philosophy. However, the tower’s journey was not so simple. It was not completed by 2012 owing to rising costs of construction and a number of legal problems that it was in the middle of. Take one problem that the tower faced, for example. To build the basic structure of such a project you need cement, rebar and glass. In Pakistan, cement and rebar is widely available but heavy glass is not. Every single pane of glass in all these buildings under construction was being imported.

This cost has been a major factor in building design in the past. That is why you see so many thick, old school cement construction buildings like Creek Vistas. The only glass

made in Pakistan is the thin clear sheets for residential windows not the tempered heavy and internally tinted, UV treated glass used in skyscrapers. If someone would start a modern heavy glass facility in Pakistan, they would have a lot of business going forward. According to a different source that is high-up in Bahria Town, this was the time when Malik Riaz started having doubts about the project.

Despite these challenges, the building was topped off in October 2017 and is currently the tallest building in Pakistan. However, it was other problems that have resulted in it continuing to be out of use. The biggest issues have been the court cases surrounding it, which make both running and selling the project next to impossible. However in 2020, when Bahria Town started facing cash flow issues particularly in Karachi, work on the tower stopped and the hunt for a buyer started. The only problem was that there were no buyers.

The Bahria Icon Tower has a unique design and features both residential and commercial spaces. The lower floors of the tower are dedicated to retail shops and offices, while the upper floors are reserved for luxury apartments. The tower also has several amenities, including a gym, swimming pool, and cinema. Based on its sheer size alone, the tower even in its current state has become a city landmark. In fact, the very existence of the tower is testament to the rapid growth and development of Karachi in recent years.

As of 2021, the estimated population of Karachi, Pakistan is around 16.5 million people, making it the largest city in Pakistan and one of the largest cities in the world. It is difficult to determine how many people live in apartments in Karachi, as there is no official data available. However, due to the high population density in the city, it can be assumed that a significant portion of the population lives in apartments.

This is where things get complicated. Malik Riaz has been looking for a buyer. The officials at Bahria Town have said that since there are court cases regarding the building they cannot comment on whether or not they are trying to sell, and that even if they wanted to, the court cases would stop them (more on those later). But Malik Riaz isn’t really the sort of real estate developer that lets courts get in the way of his development. The decision to stop work on the tower and look for a buyer came as the result of cash flow issues, according to one source within Bahria Town. However, who would buy the tower? There have only really been two examples of entire buildings being successfully bought out in its entirety. One example was when Bank Al

Habib bought the centrepoint building from TPL Properties in May 2021. Centrepoint happens to be, quite literally, the center of TPL’s ambitions. This is one of the biggest developments in the real estate sector of Pakistan. Some facts about the building: the 28-story Centrepoint, stands 385 feet high, and has been constructed on 26,226 square feet of land. It has 197,810 square feet of rentable space, with the offices on 17 floors (from the 11th floor to the 24th, and the 26th and 27th floor).

In comparison, Malik Riaz’s project has nearly three times the number of stories that the TPL building had. The second example is when Habibullah Khan sold a real estate property in the biggest deal of its kind to Habib Bank. This indicates that the only real buyers for Malik Riaz’s Bahria Icon Tower would be a bank or a very large corporation looking for new offices.

The problem with that is that the tower is multi-purpose and has residential, commercial, and office spaces. This means it can’t exactly be used just as an office building, unless a bank also decides it will provide residence to its employees in the same building. However, the building is significantly bigger than any other project that has been bought out before. Then there is also the Bahria Town reputation in terms of cutting corners in build quality. The most significant problem, however, are the many court cases that plague the project.

The conflict starts from the 3.68 acres of land that the tower has been constructed upon. In June 2019, the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) initiated proceedings regarding the plot of land that the tower had been built upon. The bureau claimed that the original plot was what is known as an ‘amenity’ plot

and had been illegally sold to Bahria Town.

In the world of real estate, an amenity plot is a public property owned and allotted by the government in a particular region or city. These types of plots can only be used for the construction of government offices as well as the establishment of public welfare facilities, such as hospitals, worship places, educational institutions, burial grounds, parking lots, and different types of recreation spots.

Pakistan’s encroachment laws hold that such plots can only be used for public welfare purposes otherwise it would be considered an encroachment. Also, the development authorities in Pakistan can rightfully demolish any illegal construction. In this particular case, the plot was supposed to have been allotted to Bagh Ibne Qasim — which is a park located near the Clifton Beach in Karachi close to the shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi and the current location of the Bahria Icon Tower.

As the case unfolded, it turned out that NAB arrested Sajjad Abbasi, the works and service secretary of the Sindh government for his alleged involvement in the Icon Tower case. In a court statement, he admitted to selling the amenity plot to Dr Dinshaw Anklesaria, who worked as the executive district officer of the revenue department. He was claimed to have sold the plot to Malik Riaz, who then constructed the Bahria Icon Tower on it.

In February 2020, the accountability court of Islamabad summoned Malik Riaz, his son-in-law Zain Malik and other accused persons in a corruption case pertaining to the Bahria Icon Tower. The other accused included Manzoor Qadir Kaka (former chief controller of construction), Ahmad Ali Riaz (former director of and CEO of Bahria Town) and Yousaf Baloch (former senator) among others. The Bahria Icon Tower was perceived as an offshoot of the fake accounts case, and it was the first reference wherein Malik Riaz

had been nominated as an accused person.

According to NAB sources, all the accused persons had incurred a loss of Rs 100 billion to the national exchequer through the illegal allotment of an amenity (welfare) plot of Bagh Ibne Qasim to M/s Galaxy Construction (Pvt) Ltd (Bahria Icon Tower), where the tower itself was erected. NAB filed the reference before the registrar accountability court, which then placed it before the administrative judge, Mohammad Bashir. According to a senior lawyer from the Bahria Town legal team, Malik Riaz would be unaffected by this. He could file an acquittal plea as the evidence against was seen as weak. Nevertheless, this deal would prevent from contesting elections or holding public office as a plea bargain does not waive the conviction. At this point, his lawyer clarified that the real estate tycoon had no such ambitions and was only concerned with the smooth operations of business.

More recently on 15 February 2022, the Accountability Court adjourned the Bahria Icon Tower corruption reference till March 1, without further proceedings due to the absence of judge Muhammad Bashir. According to the report of the Joint Investigation Team (JIT) that also investigated the fake accounts case, the Bahria Icon Tower was an embodiment of the land grabbing and money laundering trends that undergird real estate development in Pakistan.

Finally the Accountability Court (AC) declared October 7 as the date to announce its verdict on the Bahria Icon Tower case against Malik Riaz and others. In the previous hearing, the court had directed NAB to determine if the plot’s value was based less than Rs 500 million. NAB itself had already filed a reference against Malik Riaz and others for the illegal land allotment.

In December 2022, however, it turned out that Malik Riaz got off scot-free in the reference related to the illegal allotment of

“We go to foreign countries, we see what they have done, we steal the idea and we bring it here. That is all there is.

Like I just saw the Eiffel Tower recently, so we imported a replica from China and everyone loves it and comes to Bahria Town from far away to see it”

Malik Riaz, chairman Bahria Town

an amenity plot for his skyscraper in Karachi. This happened when an accountability judge claimed he did not have jurisdiction to hear the case after a change in the law by the incumbent federal government. Accountability Judge Mohammad Bashir, while disposing of the applications filed by the suspects in the BIT reference on the basis of amendments in the National Accountability Ordinance (NAO) introduced by the current government, observed that since he lacked jurisdiction to hear the reference, the case is being remanded to the National Account¬ability Bureau (NAB) for onward transmission to the competent forum.

The project was intended to be completed in 2023. However, the management of Bahria Town seems reluctant to discuss the controversies and developments related to it. Nadia, the spokesperson of Bahria Town informed Profit, “since the project has not been completed yet, nothing can be said about it.” She was hesitant to discuss any aspect of the project, waiting for the project’s eventual completion to answer all questions.

Despite Karachi’s violent local politics, the potential of the Sufi Saint. In times of heartbreak, the saint has greeted his devotees with open arms. People have found prayer, food, music and ultimately, a safe haven at his rendezvous. However in the prevalent kingdom of private developers and imagined concrete jungles, the sustenance of such vibrant social practices is a big question mark. Elite-oriented developed practices have resulted in the increasing gentrification and by consequence,the flattening

In 2019, the National Crime Agency (NCA) of the United Kingdom agreed to a settlement worth £190 million with the family of property tycoon Malik Riaz. The settlement was the largest ever in the history of the NCA, and since it was out of court, came with the stipulation that it did not “represent a finding of guilt”.

To understand this, the NCA is a national law enforcement agency in the UK that investigates money laundering and illicit finances derived from criminal activity in the UK and abroad. If the NCA is investigating a case outside of the UK, it returns the stolen money to the affected state. So if the agency is investigating fraud or money laundering in Pakistan, it will prosecute or make a settlement in the UK and return the money to the Pakistani government.

That is what happened in the case of Malik Riaz. His family had been under a ‘dirty money’ NCA investigation for a while, which reached its conclusion with the £190 million. However, the matter gets murky with the entrance of Special Assistant to the Prime Minister on Accountability Shahzad Akbar, who apparently on the behest of Malik convinced the NCA to settle the matter and return the money to Pakistan.

On Dec 5, 2019, Mr Akbar announced at a press conference in Islamabad that £140m had been repatriated to Pakistan, into the Supreme Court’s account. When asked how the money could be transferred to the SC account, he deflected the question saying that the government, NCA and Mr Riaz had signed a “deed of confidentiality” which prevented him from elaborating on the matter.

So what happened to the money? We don’t quite know, and this is where the web gets really intricate. Essentially, the accusation is that the £140m that was repatriated to Pakistan after Shahzad Akbar’s intervention with the NCA on behalf of Malik Riaz went straight back into the bank account of the property tycoon.

After coming to power, the incumbent PDM government accused former prime minister Imran Khan and his wife Bushra Bibi of accepting billions in cash and hundreds of kanals of land from Bahria Town in return for the help that Khan’s government gave to Riaz during his investigation by the NCA. Interior minister Rana Sanaullah claimed that Bahria Town entered an agreement and gave a 458-kanal land with an on-paper value of Rs 530 million to a trust owned by Imran Khan and Bushra Bibi. The land was donated to Al-Qadir Trust, and the agreement bore signatures of the real estate’s donors and Bushra Bibi.

of social diversity. While signal-free corridors are being built for car-owners, there are no footpaths for the millions who walk to work. While high-rises boast infinity pools, clean water for basic hygiene isn’t available to the people. The Bahria Icon Tower is another example of the classist lens that shapes urban development in Pakistan.

While Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s grave’s site is significantly older, the shrine complex was built immediately after Partition and became a renowned site for pilgrimage.

The street adjacent to the shrine was filled with pilgrims and many vendors selling Ta’wiz, flower garlands

and food. Supplicants, beggars and musicians were widely present. Tolerance was observed for the itinerant and the homeless who were accommodated in the shrine’s precincts. Now, while mammoth shopping malls are being constructed, the streets are being cleared of local vendors who are considered a menace to public security. The developers gained the right to transform the site and according to rumours, incentives for cooperation were provided- involving offers of free pilgrimage trips to Mecca. This offer extended to both patrons as well as visitors.

According to the shrine custodian, a billion rupees were channelled by the developer into the expansion and renovation of the shrine. The shrine has been cordoned off by an enormous boundary wall that demarcates the shrine from the street. Now, visitors have to navigate their way through the cordon protected by Bahria development group’s private security guards. The surveillance is further complemented by tighter restrictions of drug-use and scrutiny of the homeless. Furthermore, there used to be a guest house for the pilgrims who would visit the shrine.

This had been functioning since the past sixty years, but has now been omitted from the new master plan, because of the perceived security threat from the pilgrims. Previously seeking refuge at Ghazi’s shrine, the devotees now find themselves in Riaz’s prison.

In the private developers’ domain, the idea of a public space is becoming increasingly exclusionary.

Between the Bahria Icon Tower and the shrine, a lane stretches from the shrine to the sea. Very often, people would walk across this lane towards the sea, and visit the Play Land and aquarium along the coast. Developed along the lane was a well-organised market for food, seashell trinkets, art work and souvenirs, which the visitors took great delight in. However, the market no longer exists and the sea is also inaccessible from the lane. Now, the lane opens to the Beach View Park where one has to pay for entry. The lane’s hawkers have also shifted to other locations where they complain of reduced earnings. Many have been forced to forego their traditional vocation and acquire jobs with contractors and small businesses in the vicinity. While the Bahria Icon Tower may occur as a symbol of modernity in a despaired Karachi, its physical, economic and social space is largely inaccessible to the non-elites. Such development practices are widening the class-gap.

This project too has been subject to resistance both by residents and local NGOs due to its problematic location between two key historic monuments- the shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi and

the Jehangir Kothari Parade. The opposition lamented that this project would jeopardise the infrastructure of these two historical sites. According to public reviews and local reports, the Bahria Town’s construction juggernaut was enabled by digging up large chunks of Shahrah-e-Firdousi and a section of Sharah-e-Iran. In response to the municipal objections, the company offered to construct an underpass and a flyover in the surrounding area. The flyover project was also financed and built by Bahria Town under the supervision of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC), with an estimated cost of Rupees 1.89 billion. This was unprecedented for a project of such magnitude to be outsourced by a private corporation. It’s also believed that the construction of the flyovers and underpasses had been initiated without meeting the legally mandated environmental assessments. Malik Riaz maintained a close relationship with the former president Asif Ali Zardari, which seems to be a factor of the efficiency and the discreteness through which the project was being executed.

Not only the mazar is affected by this construction havoc. There is also a temple next to the Shrine, the Sri Ratneshwar Mahadev Temple, which is venerated by Hindus and is believed to be 150 years old. The underground temple, predicated on six levels, is on the brink of collapse. Both the shrine and the temple are central to the historic and cultural fabric of Karachi. Therefore, both heritage lovers and advocates raised concerns about the damage incurred to the shrine and temple due to the ongoing excavations. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) also voiced concerns about the construction’s dire impacts on the Mahadev Temple. Similarly, the design of the underpasses violated heritage laws, as the heritage site of Jehangir Kothari Parade was encroached upon and the roof of the Mahadev Temple was damaged. The Jehangir Kothari Parade is a historic emblem, which is now injured and virtually concealed from the road because of the new underpass.

So here is what it comes down to.

In 2009, Malik Riaz envisioned Pakistan’s first skyscraper and wanted Bahria Town’s name on

Project Name: Bahria Town ICON

Developer: Bahria Town

Location: Karachi.

Architect: Arshad Shahid Abdullah (Pvt.) Ltd., Karachi.

Contractors: Habib Rafiq Pvt. Ltd., Atlas Pakistan Ltd., Paragon Constructors Ltd., Yuanda China

Project Management:

AAA-Partnership

Engineer: ESS-I-AAR, Karachi. (Structural), Beg Associates, Karachi. (Structural), WSP, UAE. (Structural)

MP Contractor: Kaaf Engineers

ICT Consultant: ITnIS Consulting

Security consultant: Kroll Inc.

CFA: 2,230,500 m2; (24,000,000 ft2)

Estimated Cost: $250 million (At the time of EIA report)

Car Parking: 7 Floors 1,700 cars & 400 2-wheeler

Floors above ground: 62 Floors

Floors underground: 7/8 Floors

Construction started: 2008

Completion: 2017

it. The project came to life, land was acquired for it to be built on, and over the next decade Pakistan’s tallest building came together story by story. In the middle, people invested in the project by buying files and booking certificates — typical of most real estate projects in the country.

Now, when the project should have been completed and the tower on its way to being occupied, it sits empty collecting dust. Why? Because the land on which it was built became the centre of an accountability bureau trial. The tower over time became enough of a thorn in Malik Riaz’s back that Bahria Town tried to sell the project but couldn’t find any serious buyers on account of the legal maze it is stuck in. On top of that, it has caused havoc because of its location close to a sacred shrine.

But here’s the catch. The 62-story high Bahria Icon Tower is here and it is here to stay. As the tallest building in Pakistan, an investment of this size will not go to waste. Whether Bahria Town is able to extricate itself from this mess or not is yet to be seen. But such a massive construction must be put to good use and not allowed to go decrepit. n

It is the season for dates in Pakistan. With Ramzan around the corner, there will over the next few weeks be a sudden influx of dates being sold on roadside carts and at the checkout counters of department stores. The seasonal novelty and religious symbolism associated with this fruit means that at least once a year dates are everywhere in Pakistan.

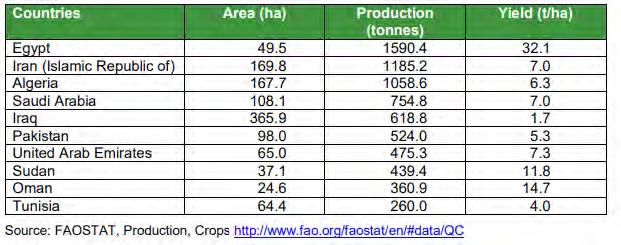

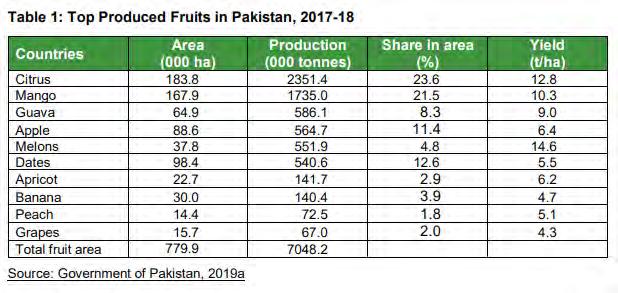

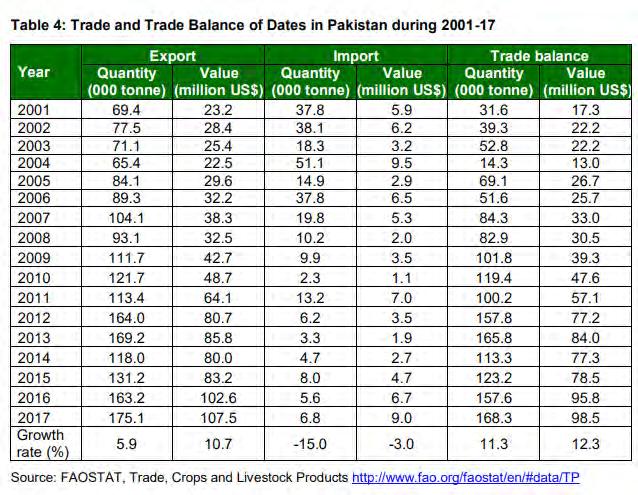

And it is precisely because of this that most people assume that the dates we consume are imported from the middle east. At the very least, the general perception is that dates from Saudi Arabia and Iran in particular are of a higher quality. While this might be true, Pakistan is surprisingly one of the largest producers of dates in the entire world. Globally, 1.25 million tonnes of dates worth US$1.48 billion were exported during 2017. Currently, the top dates producing countries are Egypt, Iran, Algeria and Saudi Arabia, while Iran, UAE, Pakistan and Iraq are top dates exporting countries. On the other hand, India, UAE, Morocco and France are leading importing countries both in quantity and value terms. Pakistan stands at 6th position among the largest date producing countries in the world. In Pakistan dates are grown at 98 thousand ha, with 541 thousand tonnes of production and an average yield of 5.5 tonnes per ha.

Yet there is significant room for improvement in how we manage this crop. According to the latest available statistics, global production of dates was 8.2 million tonnes from more than 1.3 million ha with an average yield of 6.1 tonnes per ha. This means that on average Pakistan produces less dates per hectare than other major producers, but that there is a pretty significant chunk of agricultural land that is dedicated to the production of dates.

By Abdullah NiaziAccording to a report from the planning commission, the yield per hectare in Pakistan declined at the rate 2.1% per annum vis-à-vis international average yield improvement at 0.4% per annum. Pakistan’s yield is now 13% lower than the world average yield. Trade in dates from Pakistan up until a few years ago was doing pretty well — both in terms of quantity and its value at quite a high rate of around 11%. The export of dates from Pakistan had reached $108 million in 2017. However, this was never a sustainable system because of its declining per ha yield in the country. Moreover, Pakistani dates in international markets fetch only 60% of the world average export price indicating issues in its value chain resulting in poor quality dates. Expansion in export along with declining production has reduced the per capita consumption of dates in Pakistan by about 42%, although they are in high demand during the Ramzan season.

So what does any of this mean? Essentially there are two parts to the equation. The first is that Pakistan needs to up its game in terms of how many dates it produces per hectare dedicated to growing them. Whether it is through better farming practices or genetic modifi-

Pakistan is the sixth largest producer of dates in the world. Can we unlock the export potential of this seasonal mainstay?

cation there needs to be a way to get more dates in less space. The second part is that since the date trade has potential in Pakistan as an exportable product, particularly close to Ramzan, it is worth investing in the value chain of the date crop in Pakistan.

But before we get there, it is important to actually understand the crop itself. For starters, it is not like wheat or rice where new seeds have to be planted every sowing season. Dates grow on trees, and that means once a farmer plants a tree there is a maturation cycle before that tree starts giving fruit regularly. Once that happens, then the tree provides a yearly cycle of fruit for a certain period of time.

While dates are neither native to nor a major staple in the Indian subcontinent, the area is still quite rich to farm them. Dates can grow well in very hot and dry climates, and are relatively tolerant of salty and alkaline soils. Date palms require a long, intensely hot summer with little rain and very low humidity during the period from pollination to harvest, but with abundant underground water near the surface or irrigation. One old saying describes the date palm as growing with “its feet in the water and its head in the fire”. Such conditions are found in the oases and wadis of the date palm’s centre of origin in the Middle East. Date palms can grow from 12.7°C to 27.5°C average temperature, withstanding up to 50oC and sustaining short periods of frost at temperatures as low as –5 oC. The ideal temperature for the growth of the date palm, during

the period from pollination to fruit ripening, ranges from 21°C to 27°C average temperature. date palm likes warm climate for a relatively longer period, however, rains during flowering and fruit ripening stages are harmful for this fruit. dates are widely grown in the arid regions between 15oN and 35oN, from Morocco in the west to India in the east or location is at 100 - 200 metres above sea level.

According to the planning commission’s report, “ecologically, the areas well suited to dates cultivation include those where: i) location is at 100 - 200 metres above sea level; ii) prevailing temperature ranges from 3oC to 45oC; iii) rainfall ranges from 200 mm to 250 mm; and, iv) the soils are sandy loam and clay loam. It can also be grown in the soils having high salts. Date palm likes a warm climate for a relatively longer period, however, rains during flowering and fruit ripening stages are harmful for this fruit.”

In Pakistan, in terms of area, dates are the sixth most produced fruit in the country, and also rank sixth in terms of total production. . In Pakistan, date palm is cultivated in arid and semi-arid regions which are characterised by long and hot summers with no or at most low rainfall, and very low relative humidity level during the ripening period. Exceptional high temperatures (± 56 °C) are well endured by a date palm for several days under irrigation. More than 300 date varieties are known to exist in the country of which the twelve most commercially important cultivars are: Karbalaen, Aseel, Muzawati, Fasli, Begum Jhangi, Halawi, Dashtyari, Sabzo, Koharba, Jaan Swore, Rabai, and Dhakki

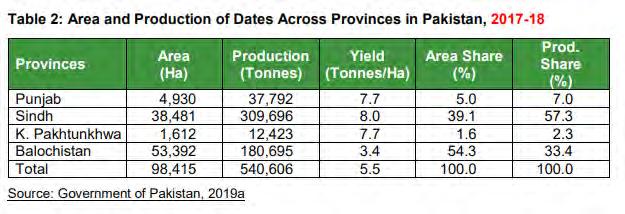

One of the most encouraging aspects is that these regions actually produce very high quality dates. The total production of dates in Pakistan was 540.6 thousand tonnes from 98.4 ha in the year 2017-18 with an average yield of 5.5 t/ha. Balochistan is the major date producing province in Pakistan followed by Sindh. The province of Balochistan produced 33.4% of total production of the country with 3.4 tonnes per ha yield while the province of Sindh produced 57.3% of total production of the country with 8.0 tonnes per ha yield. Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are 3 rd and 4th most producing provinces of the country, but their average yields are much higher than their counterpart most-producing provinces of Balochistan.

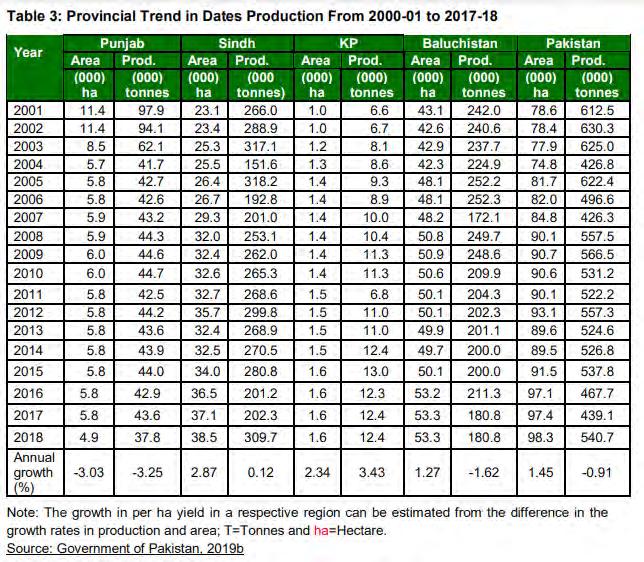

However, despite the export potential, low yields are killing Pakistan’s chances of utilising its dates. Production in Pakistan has decreased from 612.5 thousand tonnes in 200001 to 540.7 thousand tonnes in 2017-18, which produced a negative trend of 0.91% per annum. This decline in production came entirely due to the plummeting trend in yield per ha at a quite high rate of 2.36% per annum, while area under dates has expanded at a rate of 1.45% per annum during the period.

The declining trends in per ha yield of dates are prominent in all provinces, except in KP where it increased at the rate of 1.85% per annum. The highest yield decline came from Balochistan and Sindh, where it plummeted at the rates of 2.89% and 2.75%, respectively,

while decline in yield in Punjab was relatively small and insignificant at 0.22% per annum.

On the other hand, area under dates expanded in all the provinces, except in Punjab where it declined at quite a high rate of 3.03% per annum. The highest increase in area came from Sindh followed by KP where it expanded at the rates of 2.87% and 2.34% per annum, respectively. The area under dates in Balochistan expanded at 1.27% per annum rate (Table 3). As a result of the above two phenomena, the production of dates significantly increased only in KP at 3.43% per annum rate, while in Punjab and Balochistan it shrunk at the rates of 3.25% and 1.62% per annum, respectively. In Sindh, the production increased was only marginally at 0.12% per annum.

This year the situation of already falling production and yield has been further aggravated by the massive flooding that took place in the country last year. The freak monsoon rains triggered by climate change left hundreds of farms under water even months after the rain stopped. In some areas, the flooding was high enough to drown out some of the smaller trees. In almost all of these areas, the force of the water was strong enough to dislodge them from their roots.

And therein lies a massive problem. As was mentioned earlier, dates are a fruit not a crop. That means a tree is planted, it comes to maturation and then it gives fruit every cycle. If the tree is routed from its home, farmers cannot wait for the flooding to go back down and plant new seeds. They will have to plant

sapling and wait years for the trees to grow to maturation and provide the fruit again. For context, it takes a decade for a palm tree to grow fully and start bearing fruit. Once these trees mature they can go on to produce dates for up to 60 years. This means the number of dates forgone as a result of these floods is catastrophic.

Although dates are grown in all the four provinces of Pakistan, its cultivation as a commercial crop is concentrated in few districts in each province which are largely marginal with low crop productivity. Keeping this factor in mind, the planning commission in its report actually made a suggestion that three dates producing clusters i.e., Khairpur as Sindh Cluster, Turbat & Panjgur as Balochistan Cluster and Muzaffargarh be identified as date producing

clusters.

In consultation with stakeholders, several challenges of the date industry of Pakistan from production to harvesting and marketing are identified in this study. On production side, weak research and extension capacities, absence of the mechanism to replace old with new high yielding varieties, lack of nurseries with certified mother-blocks, water scarcity especially in Balochistan cluster, traditional methods of spathes selection and pollination, non-covering of fruit.

According to the planning commission’s suggestions, to overcome these constraints and keeping in view the cluster-specific environment, interventions are proposed at the respective focal point of each cluster for making the dates a competitive and export oriented commodity of Pakistan. These interventions include:

a. Restoration of existing orchards with plants of higher yielding, modern and exotic varieties

b. Training farmers for adopting improved orchard management practices

c. Controlling harvest and post-harvest losses by adopting better pollination strategies and fruit bunch management;

d. Shifting to solar tunnel dates drying;

e. Employment state-of-the-art packaging technologies and linking of stakeholders with markets.

“In order to implement these interventions at the focal points, total project investments needed is US$108.144 million. Out of the total investment, about 28% are proposed to be borne by the federal and provincial governments and remaining 72% by the private sector. The federal government will bear 30% of the total cost, while the provincial governments will bear the remaining 70% through their respective annual development plans. As a result, after the successful implementation of the 5-years long proposed project, it is anticipated that during the 10th year, more than 260 thousand additional dates will be produced from all the production enhancing interventions.”

People don’t consume news the way they used to. Up until the turn of the century, printed newspapers and magazines were a major source of how people stayed informed. Yet from the mid-2000s onwards, the print media was hit by a double-whammy: the advent of private television news channels and the rise of the internet. The story from here on out is a global phenomenon: print media is dying.

That was the story up until a decade ago. In Pakistan as well, the turn of the century saw an influx of private television news channels. Currently Pakistan has around 30 private television news channels. The reality is that very few of them are profitable or a good business idea. Over the years, just like the newspaper industry was kicked to the curb by broadcast television, digital media hosted over the internet is quickly making cable television obsolete as well.

The vast majority of how people consume their news is through the internet and social media. As such, the nature of news has changed. Those hoping to stake a claim in the digital media landscape have to better understand the consumer, fit their patterns, and figure out how to appeal to a generation that consumes, recycles, and forgets information faster than any generation before them simply because of the constant access they have.

Aesthetically pleasing design, clean and

understandable videos, smooth animations, friendly and relatable faces and catchy brand names, the digital news media in Pakistan has tried to make waves and in many ways has succeeded in changing what are considered traditional sources of news. And there is no shortage of hopefuls in the market. The launch of a new digital media platform that promises to “cut through the noise”, “make the news understandable” or become the pioneers of “data-driven and neutral reporting” is a regular occurrence. What is also a regular occurrence are these platforms shutting down. Names like Mangobaaz and Parhlo have gone from prominence to running skeleton operations because of a lack of funds. The question is, can digital news media companies also make money or is influence the only currency they are dealing with? This race to monetize news media content is the million dollar question that plagues both the new and old players of Pakistan’s news media industry. As a more tech-savvy Generation-Z make their weight known as consumers of news, what will the future look like? Profit looks at some of the digital news media outlets operating in Pakistan to try and figure out their financial feasibility and business model.

Aresearch study published by the Open Society Foundations shows that an increasing amount of news coverage on TV is strategically planned to

take advantage of the locations of Peoplemeters (electronic audience measurement tools that determine channel ratings) to boost ratings. There are approximately 680 Peoplemeters in Pakistan; of which half are in Karachi, and the majority of the remainder are in major cities such as Lahore and Islamabad.

With such a model, the content leaves little opportunity to reflect the preferences of a diverse audience. What this means is electronic media simply excludes a large proportion of the population: the audience of rural peripheries, women and gender minorities, and younger ones in families as the TV is traditionally a familial device and its control is dominated by mostly the patriarchs. So there are no surprises there that the news content is made for and by certain audiences only.

That’s where digital media found its first in. On the internet, content is King. While with television and print media you could argue that newsmen could set narratives and decide consumption, the internet provides an equal voice to every single person and allows them to create their own content. Pakistan’s mobile internet penetration stands at 54%, precisely 122 million Pakistanis have access to the internet through smartphones, as reported by PTA in December 2022. This figure tells an interesting story. With more than half of the population’s access to the internet, the digital landscape is fertile soil not just for information and narrative-building, but also for business.

The most obvious thing about digital news media is the different demographic of the

With more than half of the population’s access to the internet, the digital landscape is fertile soil not just for information and narrative-building, but also for business

We have to create other revenue streams such as ad rolls, and paid posts on our social media platforms. This includes content campaigns for third-party organisations, both public and private, who pay us for posting their content. Mostly they send us the content and art pieces to be pushed by us, other times we create it with them. This component makes up to 25% of the total revenue generation, in which each post is charged at about Rs 50,000-100,000

target audience. According to a research study conducted by Gallup, 64% of adults between the ages 18-23 use the internet actively, and 54% of adults from 23 to 30 use the internet actively. The percentage reduces as the age bracket increases, for example, above the age of 50 only 31% use the internet actively.

Therefore, the target audience for digital news platforms is also Gen-Z and millennials. In a conversation with Usra Murtaza, a digital communication strategist who worked as a content producer for the Thought Behind Things podcast, Profit learned that the audience changes with the topic of the content. “For serious news and emerging issues and themes, the audience was around 24-35 and mostly male. The second highest figure audience group was 18-24,” she mentioned. Such an audience range also dictates the quality and style of the content. “For example, more than just topics we have to make sure how it is delivered to the end consumer, it includes the thumbnail design, uploading hours, and the way information is communicated in easy and understandable language,” she explained.

Similarly, in a conversation with Momina Mindeel, Programs Manager at Media Matter for Democracy (MMFD), Profit learnt that despite journalism being a male-dominated field, digital media provides room for female and minority gender groups to voice and broadcast their stories. Below is the gender distribution of 248 respondents, working in various roles from editors to producers, surveyed about the medium they use to broadcast their stories.

Since the audience is different, digital media paves a way for content which usually does not find space in the mainstream media. “TV content is quick and small, so a lot of the news items especially related to entertainment or sports don’t really make it there. That’s the kind of news that

performs really well in the digital wing. Other than that, long-form investigative pieces also find space in digital, rather than TV. Recently, we ran an investigative report on the assets of parliamentarians which included a lot of details. Similarly, interviews with high-profile personalities are only aired in chunks on TV, the full version is uploaded digitally,” said Gibran Ashraf, editor Samaa digital. “We follow the editorial guidelines of the TV channel, but we do maintain somewhat independence by running such content.”

Profit also reached out to Talha Ahad, the founder and CEO of The Centrum Media (TCM). “The content which has done the best are usually those which aren’t really covered traditionally. For example, our series Naked Truth with Julie, a transgender’s commentary on social issues of Pakistan, went viral. Purely political content also performs really well but it’s mostly the long-form documentary series on security and geopolitics that defines our reach and engagement,” explained Ahad.

A lot of the time, content which usually faces censorship or TV or print makes it to digital, but that’s again a hit or a miss. “There are some unsaid lines in Pakistan’s news landscape. Other than that, digital has to deal with international laws as well,” said Ashraf. A lot of the time news get removed or face warnings if they are about the stories which are considered sensitive internationally. “We recently uploaded a video clipping for Afghanistan’s foreign minister in which he said Pakistan should take the responsibility of the police lines bombing in Pakistan and we received a strike from Facebook to take it down,” said Ahad.

Despite fresh content, out-of-thebox stories and applaud-worthy reach, the revenue generation for digital media doesn’t depend on the audience’s response. In Pakistan, the cost per

impression (CPM) is quite low. “YouTube just recently launched shorts and if you get 10 million views on YouTube shorts you earn $900. So per impression, it’s just a couple of cents. It’s the same for the website, just a couple of cents for one impression,” mentioned Ashraf. “We have to create other revenue streams such as ad rolls, and paid posts on our social media platforms. This includes content campaigns for third-party organisations, both public and private, who pay us for posting their content. Mostly they send us the content and art pieces to be pushed by us, other times we create it with them. This component makes up to 25% of the total revenue generation, in which each post is charged at about Rs 50,000-100,000,” elaborated Ashraf. The rest is covered by YouTube and Meta monetization, which does the job well for Samaa, and other digital subsidiaries of TV channels, which easily enjoy more than a couple of million subscribers and a much larger reach.

Digital news in general is looking at better times. “Initially the TV channels would set up a digital wing just for an online presence but now they have realised that it’s a separate means for earning money also. The ad rolls, campaigns and YouTube and Facebook monetisation have made the digital wings independent of their parent organisation revenue-wise. Digital wings actually end up creating extra revenue for the main channels. The CPM rate is comparatively low to international standards, but it does the job of self-sustenance if the reach is over and above a couple of millions,” said Ashraf.

The digital subsidiaries of TV channels earn their initial capital and support from their main channels, confirmed Ashraf. But things are a little more difficult for digital-only platforms. “The initial capital was around Rs 1-2 million which included my savings and some investments and loans from friends and family back in 2016. Today it would cost a lot more to start a digital channel,” said Ahad. Over time, TCM developed its revenue stream

through client servicing. “We take projects from the development sector and corporate sector. But we try to not take too much commercial work, especially with corporations, that doesn’t align with our editorial board.,” he continued. “But the majority of the revenue comes from the services industry, which doesn’t impact the editorial. For example, we have started doing a lot of journalistic training and digital workshops for the communication arms of NGOs,” he mentioned.

For a news channel, no matter what the format is, money-making always remains a challenge as it impacts the credibility of the platform. From the politicisation of TV licensing to capital backing from state institutions, running news in Pakistan is a slippery slope

even for digital news channels. “Every now and then the three major political parties reach out to push certain stories for their narrative. This happened a lot during the time of Imran Khan’s ouster through the vote-of-noconfidence when even the established reached out and wanted to use TCM’s audience to create certain stories around the institution or other parties,” pointed Ahad. “Sometimes the money they offer is so much that we as an organisation could easily relax and not earn any revenue ourselves. But caving in would not leave us any different from the mainstream media,” he elaborated.

That is essentially where the problem with the multimedia form of news also stands. Digital media which is still in its primacy is

opening a lot newer opportunities for young journalists and innovative ways of storytelling. But at the same time, it confronts a dangerous problem. Easy access to the internet and freedom of uploading content has created a threat of disinformation. There is an increasing trend of individual vloggers and YouTubers giving an analysis of the news, without going through an editorial process of fact-checking and impartiality. As internet penetration in Pakistan is growing, it is becoming crucial to note the difference between online activism and digital journalism. A professional field which has historically faced crackdown and threat of decay stands the test of time as it weaves through technological advancement. n

Every now and then the three major political parties reach out to push certain stories for their narrative. This happened a lot during the time of Imran Khan’s ouster through the vote of no confidence when even the established reached out and wanted to use TCM’s audience to create certain stories around the institution or other parties. Sometimes the money they offer is so much that we as an organisation could easily relax and not earn any revenue ourselves. But caving in would not leave us any different from the mainstream media

Talha Ahad, CEO of The Centrum Media (TCM)By Nisma Riaz & Taimoor Hassan

The startup ecosystem in Pakistan ensures the survival of the fittest and AimFit is seemingly taking a lead in this race to the summit. What started as a health and wellness project, with three studios for fitness classes in Lahore

has now become a wellness movement encompassing a spectrum of physical and mental wellness needs beyond just exercise. Over the course of a few years, AimFit has becom b gh89e what they call a lifestyle movement.

After the founders secured $1 million in seed investment in 2020, the company became Pakistan’s first fitness tech company during Covid, branching into digital fitness services.

According to the CEO and co-Founder

Noor Shaukat, AimFit now helps reverse a broad spectrum of lifestyle problems and diseases in women through three primary pillars, including movement, nutrition and mindset coaching.

In the most recent development, AimFit has ventured into a global digital market, whereby they have extended their online fitness and wellness services to Pakistani diaspora. Not just this, but it has also introduced a

new B2B arm that extends fitness consultation services to other companies.

In an interview with Profit, Head of Brand and Marketing at Aimfit Sarah O Munir disclosed that, “AimFit has partnered with companies, including Coca Cola İçecek (CCI), Sapphire and S&P Global, that are looking to improve their employees’ health and wellness but don’t know where to start. We come on board as their fitness consultants, where we run workshops, community events and gamification challenges, and help build a fitness culture at those companies.”

After securing a million dollars of Venture Capital (VC) funding and becoming the first VC-backed fitness startup out of Pakistan,

AimFit left everyone anticipating their next move. For those inquisitively waiting on the edge of their seats to see how a fitness startup would use such a large amount of capital, the answers have arrived.

And what are the answers?

Well, AimFit’s recent B2B expansion, for one, and their digital global expansion. Before we get into the details of the company’s new business developments, let’s first consider what fitness technology is and how AimFit became the first Pakistani wellness company to introduce it. In simple terms, fitness tech is a combination of exercise equipment and virtual reality. It includes wearable technology, such as smartwatches and digital fitness trackers, as well as smartphone applications that help users record and track their fitness. Global fitness trends indicate that the future of fitness is omni-channel. Shaukat observed that people want to be wearing watches and trackers, which then connect with their health tech. You can record gym

workouts on the app, along with the food and calories you consume, having your health history all in one place. Shaukat believes that health and fitness is not just limited to four to five hours that you spend in the gym in a week, but that it has become a 24/7 thing.

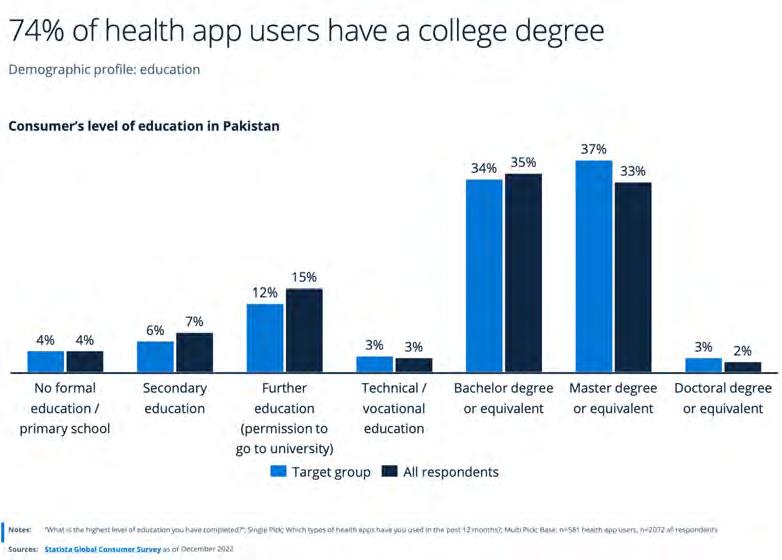

Does the Pakistani market reflect this trend? Well, only a small percentage of it. Even though there are several other fitness and health tech apps, such as FITFLEX, Google Fit, Apple Health and BetterMe that are available for Pakistanis to use, AimFit is the first Pakistani company to do this and cater to women specifically. According to the Statista Global Consumer Survey, 74% of those who use digital fitness apps in Pakistan have a college degree. The Labour Force Survey 2020-21 highlights that only 6.09% of Pakistanis have a degree, post graduate or M Phil/Ph.D. Furthermore, it is pertinent to note that according to the same Statista survey, users of health apps generally fall in the high income stratas. What does this mean? Aimfit is gunning for a niche market in Pakistan, however, within that market, users do align with their general customer demographic.

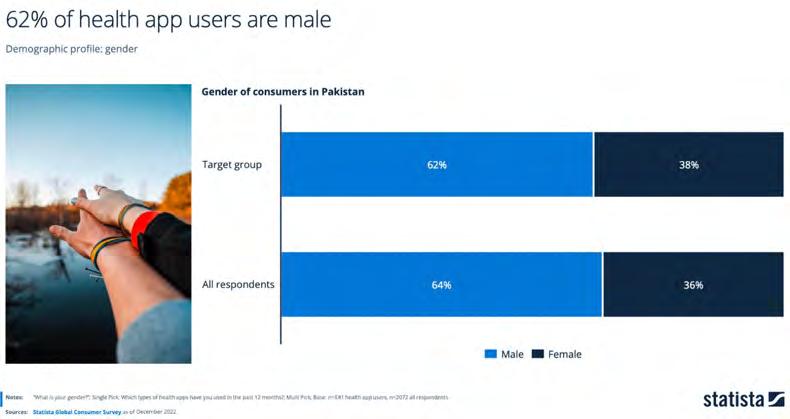

Moreover, 62% of health app users in Pakistan are male. This can be owed to the income disparity between men and women in Pakistan, however, it also reflects the need for more women to utilise this space too.

AimFit has consistently proven to fulfil the need of the hour. How?

One example that best reflects AimFit’s understanding of their customer’s needs and then designing the correct product fit for the market’s unique requirements is the online fitness community they built during the pandemic. “When we started our digital product back in 2020, it was a very weak base. Gyms were shut down but we needed to service the women who were our clients and the app was created as an alternative to serve that purpose. However, since then, habits and adoption have changed and we understand

The difference between other startups and AimFit’s business model is that we are and were sustainable from day one. We operate with a very lean team and will raise our price if our cost is not being met. Anybody who has not learnt that in the last two years has missed out on an important lesson on how we need to build and run sustainable businessesSarah O Munir, Head of Brand and Marketing at AimFit

our market better. So, rather than just facilitating them, by working out online, we also unearthed what barriers women in Pakistan are up against.”

AimFit’s success can be owed to the fact that it is not just an app for workout but a lifestyle management solution. While catering to the needs of women during the pandemic, their approach evolved and with it the solutions they offered also changed completely.

“We are seeing product market fit because we focused on truly building the solution that caters to this market. Our women have a very unique set of challenges, they are constrained by physical and social barriers. Just pointing them towards something that is built in North America and doesn’t take into account their reality, or our socio-economic conditions, our eating habits or the broader culture that revolves around sedentary lifestyle will help no one.” Shaukat shared.

That’s where the pivot has come through for AimFit, whereby understanding what the problem is brings them closer to nailing the solution and figuring out the right price point for right distribution channels for their services. According to Shaukat, that is the reason they have experienced the kind of growth that they did in the past year.

According to Munir, “Most fitness stu -

dios in Pakistan focus on physical health. You go there, you work out but there is no physical fitness without mental wellbeing. And we at Aimfit realised that very early on, so our approach is very holistic.” Munir elaborated upon how AimFit has actively and consciously been building a product for a global audience and has been growing organically.

AimFit believes that movement is an important part of wellbeing, which if used correctly can solve a myriad of our problems as a society. “As you start moving, you also realise other parts of your life you need to focus on, such as eating well, thinking better and connecting with like-minded people to form a supportive community.” Munir added. This was especially important during the pandemic, when social isolation was adversely impacting both people’s physical and mental health. AimFit pulled through by offering women an outlet to exercise, as well as bond, allowing them to fulfil two important physical and social wellbeing requirements.

AimFit’s physical and digital platforms allow women to meet women who are like them. “Pakistan as a society is constructed in a way where women don’t have these outlets to connect, workout and bond together, so through our online and offline communities we create this space for women to find that support, and discuss their problems,

something that our culture doesn’t allow a lot of the time.” AimFit has set out to solve a problem that goes beyond physical fitness, by first identifying what these problems are and then providing solutions that are tailor-made for these very problems.

As mentioned earlier, a very strong pillar at Aimfit is their community. “People can go to any gym but the reason they keep coming back to AimFit is because they have a great bond with our instructors and other women they workout with. The same applies to our online community as well, where we foster these shared experiences because that is what makes fitness and wellness fun.”

Shaukat shared that, “Our three main pillars are supported by our proprietary technology, fitness instructors and mindset coaches. The two biggest problems that we currently address in women are weight loss and depression, along with a list of other problems. However, these two are the main ones that are experienced by about 90% of the women that we work with.”

“Movement is extremely important to fight depression, in fact 50% of our studio audiences come for non-clinical depression. At AimFit, they can come together, partake in group activities, which releases a host of positive chemicals, including endorphins, which help build resilience against stress and other factors that may be triggering their depression.” Shaukat continued. Exercise is known to be a mood booster and when you’re working out with other people, there is a release of oxytocin in the body; the social bonding hormone. So, all three pillars that AimFit works with help support those struggling with depression.

Shaukat relayed that the seed investment gave the company a boost in building their tech team and scaling the tech product. It also bought them more time to establish a product market fit.

“The digital space is heavily influenced by experience at the studio but it was also a completely new ball game.”

Most fitness studios in Pakistan focus on physical health. You go there, you work out but there is no physical fitness without mental wellbeing. And we at Aimfit realised that very early on, so our approach is very holistic

When it comes to expansion, AimFit made two notable moves last year. In April 2022, AimFit ventured into B2B service provision. Corporates are now a part of the company’s clientele, whereby they avail fitness coaching and consultation for their employees’ wellness. “We focus on providing wellness solutions that are lasting, rather than just doing a one-off intervention, where we come over, conduct a yoga class and go home. The companies that we have partnered with have an approach towards health and fitness that extends beyond just giving medical benefits to the employees.” Munir informed Profit.

“Over the course of this past year, we have not just worked with companies, but also partnered with schools and NGOs. The idea here is to build awareness around why investing in your health and wellness is important. We give these companies the right partners because there is a lot of misinformation out there. So, what we aim for is a quality check like all our instructors are trained and we have a function specialist. We don’t send anyone out without a minimum training so, we have people who specialise in workouts and then those who specialise in nutritions, as well as coaches who specialise in mindfulness. So, based on what company or organisation needs we make sure that we partner with the correct expert,” she continued.

It is important to note that rather than just providing services, AimFit comes on board as a partner and thought leader in this space. However, the B2B wing of the company makes up a smaller chunk of the revenues, while the movement pillar, through their fitness studios and online platforms bring in the most money. But the goal is to scale all three.

Shaukat informed Profit that, “We pre-

dominantly cater to women and that is what we started as. We are female first, so talking about maternal health, postpartum health, PCOS and female specific health lifestyle related problems takes precedence over others. The B2B aspect was mostly created because of demand from the market. We do have a lot of people come to us and ask why we are not catering to men. Men also have very similar problems. For that, there is a version of our tech, which is for men, as well through our partner companies. We work there in a bespoke manner so we alter our services to address the needs of the organisation, including the men in the organisation. The B2B space is more gender neutral.”

In terms of revenue, the split is currently 60:40, whereby 60% comes from the studios and 40% from the digital and tech

spaces. Since, the tech wings are priced lower, but also operating on a premium model, quite a few features on our app are open for free.

The second big step that AimFit took since 2020 is global digital expansion.

“Going forward, growth in digital has been faster than growth in studios, which is always the hypothesis because you are not bound by space or any physical infrastructure investment. Hence, we are seeing that growth and we are seeing a global customer base being established there. We know that the true empathic experience is omni-channel but in the near future we expect the digital revenues to definitely grow faster and build a global presence.” Shaukat explained.

Munir added to Shaukat’s point, sharing that, “We already have paying customers outside of Pakistan. In the US, Canada, UK, Europe, Australia, Dubai, and Riyadh. These are the big areas and that’s all been through organic word of mouth. But, primarily these are diaspora Pakistani women, who we believe we know are a key audience for us because they are also struggling with similar issues. Some of them have young kids, they can’t leave them to go out and they also don’t have extended family to look after their kids. We have paying customers in at least 10 different countries at the moment.”

“Since women are joining us from all over the world, we now want to actively target growth in that area. So, the second pivotal point I think has been that we started from scratch when we aimed for a more global audience and we believed we found the right product that works for them. So, now the

goal is to establish our brand and distribution abroad, which is going to be a challenge. We had a brand in Pakistan when we pivoted to digital but of course in new markets we have to start from scratch, which is always a great challenge for us to undertake.” Munir shared. However, she is confident that AimFit’s years worth of learning, especially around organic growth, building and owning their distribution channels, using community, content and social media to grow has equipped it with the skills to make this new development a success. “Now the challenge is to establish ourselves. We know that we can establish ourselves as thought leaders in markets outside of Pakistan.” Munir concluded.

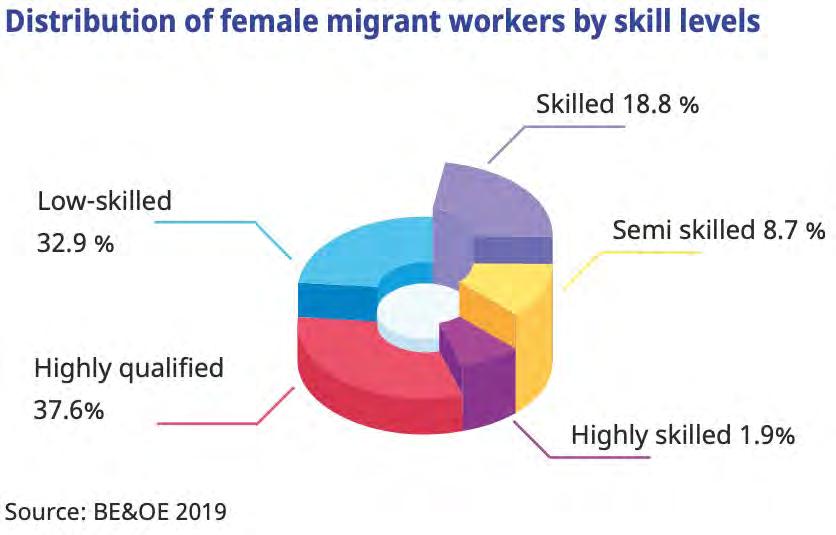

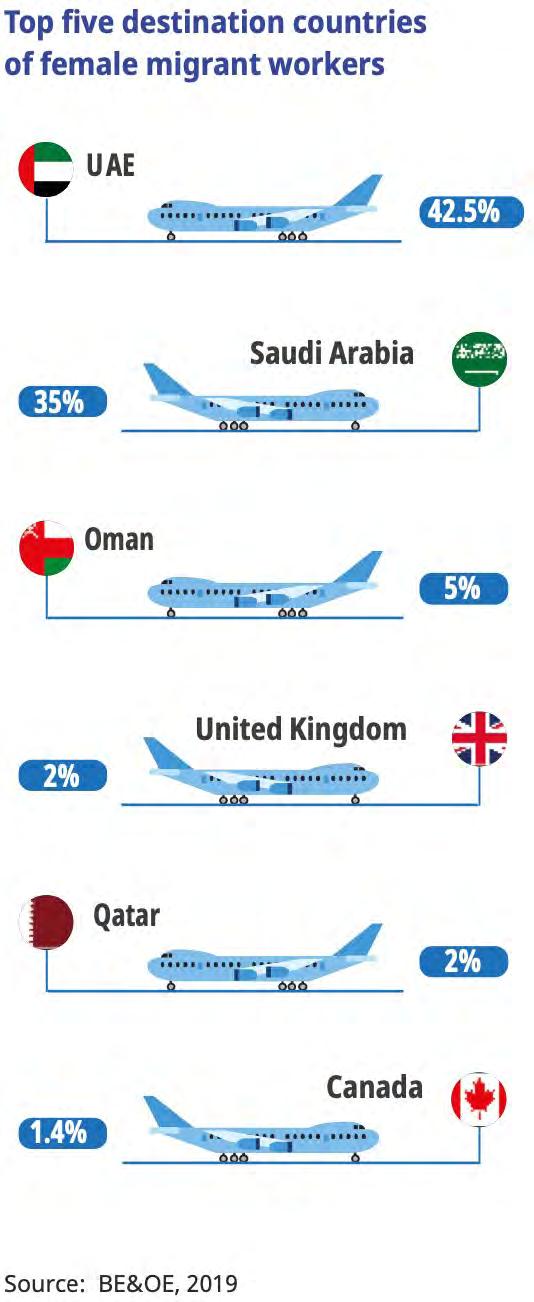

Will their global expansion be a success? Aimfit’s global foray will likely be limited to Pakistani women abroad, at least in the next few years. Looking at data provided by the Bureau of Emigration and Overseas Employment (BE&OE) in 2019, nearly half of all Pakistani females who emigrate abroad are in some form of skilled professional occupation. However, based on the same statistics by the BE&OE, half of all Pakistani women who do emigrate, emigrate to the Gulf States. This is a double edged sword for Aimfit. They can reduce their advertising costs due to the proximity of these emigration destinations, however, anything beyond that looks like a longshot based on the data.

Despite the accessibility of their services, AimFit will require a larger audience to bring about the mindset shift towards healthy living that they advocate. However, a major roadblock in

achieving this is their target market, as highlighted in the first section. Considering the prices of their physical studio services, their product remains inaccessible to many lower middle class women.

When asked how AimFit responds to this criticism, Shaukat shared that, “We have been thinking about that question, as well, over the last few months. The studios were always based for SCCA (upper-middle class and above) because they were in well off areas. We were providing a physical service, which had a certain minimum cost. The goal to build the

digital services and tech wing was to actually cater to the masses.”

Shaukat believes that the online services are designed to be reasonably affordable. However, considering the enormous economic squeeze in the last few years, the lower income strata of society has suffered the worst and sadly, it is also the strata that considers fitness to be a luxury good as opposed to a necessity. “It’s just unfortunate the way things are. When the cure for them becomes such a luxury, prevention is something that will come way after they first accept that cure is something we need to be spending money on.”

“We then had to modify our strategy to respond to the market, so over the last six months even the digital and the tech product has now been modified to serve a more premium audience and we are seeing a better product market fit. The other great thing that has come out is that the product now actually caters to a global audience.” Shaukat continued.

By making it a premium offering for women, who understand the need for it and have awareness regarding health and well-being being an investment in one’s quality of life, AimFit’s product resonates better with a global audience. “The goal eventually is to come back to the mass market. As things improve and their pockets are less squeezed in a few years time, we would love to build a more mass market solution, however, for now we have to respond to changes in the economy.”

On the other hand, Munir believes that AimFit’s digital services are quite reasonably priced. “We have two kinds of packages on

our app. One is for Rs 2000 and the other is for Rs 5000 monthly but if you go to any gym even a single class doesn’t cost you less than Rs 2000. Whereas, in Rs 5000 we give you unlimited access to all of our features. So, by our standards we have been increasing pricing to kind of reflect the market changes but if you compare it to other solutions, it’s still extremely affordable.”

She continued, “Our main barrier right now is kind of that mindset shift. Instead of considering these Rs 5000 as a luxury, we need to think of it as an investment in ourselves. So, I would say this has been our biggest learning and our biggest barrier in some ways to kind of get women to start thinking like that.”

If anything the startup culture in Pakistan has taught us, and we don’t necessarily mean successful startups, it is that raising funds continuously and in big amounts has been an important goal for most tech startups, even at the cost of sustainability. After witnessing consistent growth for the past two years, it is fair to ask whether AimFit will try to raise more VC funding this year. The answer is no.

AimFit is one of the rare Pakistani startups that has a sustainable model, has been raising funds without disclosing and will be doing the same in the future.

Shaukat believes that building a self-sufficient and sustainable business is more

important than attracting funding. “The difference between other startups and AimFit’s business model is that we are and were sustainable from day one. We operate with a very lean team and will raise our price if our cost is not being met. Anybody who has not learnt that in the last two years has missed out on an important lesson on how we need to build and run sustainable businesses”

And how did AimFit crack this code?

Well, for starters, they work with advisors, who run sustainable businesses. This reflects how AimFit is not the same as a lot of the hyper growth companies in the market. “The second kind of part of the puzzle is to really zoom into organic growth. We were able to do this because the pain points are actually so critical.” added Munir.

That being said, AimFit will, however, be raising more money eventually. “It’s always good to have extra money in the bank and we have benefited immensely from raising VC funding and we absolutely want to use it towards growth. We’ll raise not when we need to but when we know we are in the best position to raise. Knowing the right time to approach an investor and to get the right price for your business, we believe, is the best time to raise funding.”

This approach saves them from being dependent on external sources of funding. This is because they come from a brick and mortar business, where profitability is the only means to survive. Shaukat insisted that AimFit has been cognizant of growing organically and sustainably, even in the digital aspect of the busi-

ness. “The best business is one that survives the ups and downs of the market and operates with that principle in mind.” Munir shared.

Shaukat resonated with Munir’s comment, elaborating that, “The best decision we took with the money was to go slow until we found product market fit and we are just about getting there in a few months. We will know that we nailed our product and our product offering. Our goal now is to bring attraction and word of mouth, which actually requires more time and perfection of the product as opposed to money.” According to Shaukat, because they had been monetizing from the start, their parallel goal remained to run a profitable business and use investment to fuel their growth further.

From the beginning, the company’s focus was to achieve growth but without compromising user experience. Their priority remains operating sensibly, indicating that revenue should be enough to cover cost. Therefore, AimFit has been extremely mindful of how and where to spend their funding. n

The nation’s leading economists have once again slammed the government of artificially keeping finance minister Ishaq Dar above his actual market value.

“This guy is an accountant,” said Dr Saleem Hassan, professor of economics at LUMS. “Nothing wrong with being an accountant. But that’s his market value.”

“Don’t get me wrong,” said Dr Faiza Zubair, head of intelligence at Fast Research. “Accountants can, much like, say, engineers or lawyers, make decent finance ministers. But he isn’t that accountant. We know who he is. How he is.”

“The PDM, and the PML(N) in particular, need to let him adjust to his natural market value, which, at best is heading public accounts committee when in opposition, and being parliamentary secretary for finance, once in government.”

“Look at how responsibly the PTI handled this situation,” she said. “They inherited an artificially high commodity in the form of Asad Umar, who was grossly overpaid by Engro. So, yes, they made him finance minister. But then they devalued him to planning ministry, but that is also a critical portfolio, so the party has made the decision to let him settle to be the guy who says ‘Pakistan ki aan hain aap’ before Imran Khan comes to the stage, on days that Faisal Javed is unwell.”

In yet another failed attempt to quietly reach home without prying journalists harassing him, Finance Minister Ishaq Dar Friday finally confirmed that he has indeed had a breakup.

Coerced into a comment over Dollar Rate by the annoying paparazzi, Dar confirmed that the two are no longer together.

“I do not know what happened to Dollar yesterday. Stop asking me the same question over and over again,” a visibly agitated Dar told the media.

“Dollar Rate and I are no longer together. We haven’t been together for a few months now,” he added.

Rumours of the breakup have been running wild on Page 3, after reports that the much touted reunion between the pair in October ended prematurely, culminating a much publicised relationship that has lasted, on and off, for the best part of the previous decade. This prompted widespread claims that the two are, at the very least, on a break.

“We are not on a break. It’s over,” Dar further informed the journalists. “We wanted different things, and mutually decided to end things.”

However, sources privy to the relationship claim that pressures from elderly figures played a huge role in the two going separate ways. When asked if that played a part, Dar replied in the affirmative.

“Jee, Abba nahi maanay.”

‘Dollar