hat does a man do when he is on the verge of commit ting suicide? Right when he has nothing, when there is no food on his table and he watches his children starve, what does he do? That is when he becomes a rickshaw driver. Not by choice, but by necessity,” says Majeed Ghauri. As chairman of the Awami Rickshaw Union, day in and day out he hears the trials and tribulations of rickshaw drivers. These are his people, and they give him his mandate.

The centre of this world of rickshaw drivers is Lytton road. And this is where the battle for the future of the rickshaw is being waged. Where a small group of companies are trying to electrify Pakistan’s three-wheeler market, and convince the rickshaw driving population that they should swap in their regular petrol and CNG rickshaws for ones with electric batteries. And they are getting closer.

The Punjab Excise Taxation & Narcotics Control Department has moved a summary to amend the Motor Vehicle Ordinance (1965) and Motor Vehicle Rule (1969) to allow the registration of electric rickshaws, but it has still not been passed. The summary was approved by the Punjab Cabinet this month, and awaits a debate by the Assembly before it can be approved. It remains an agenda item every time the Assembly does meet, and the closer Pakistan does come to achieving some semblance of political stability, the closer we get to the summary being approved. That said, if the Punjab Assembly comes around to it, electric rickshaw registration could be a done deal any day.

The only question is, will the rick shaw drivers bite?

There are close to one million three- wheelers manufactured by over 45 automobile manufacturers in Pakistan, and electric

rickshaws provide an opportunity to reset the entire market. “Internal combustion engines cannot be converted to electric. Simple as that. It’s not a conversion issue. You cannot put electrons in a carburetor and say that this will henceforth run on electricity. You will need to build a proper electric vehicle.” Hasan Mian, Founder and CEO of YES Electromo tive, told Profit

This is where many of these 45 companies have picked up on the scent of opportunity. Rickshaw drivers want more economically feasible vehicles. We saw that with the introduction of CNG rickshaws back in 2005-07, which have by now almost entirely replaced petrol rickshaws. Running these vehicles on. And the demand for cheaper transport and cheaper running costs is only going to increase with rising inflation. The first of these companies to have their electric

of the Awami Rickshaw Unionrickshaw takeoff will reset the clock, and become the hegemon. But the question is, will these rickshaws be cheaper?

If you were to go out and buy one today, an electric rickshaw is at the very least two to three times more expensive than its conventional counterpart. So what are some of the available options?

Firstly, Profit took Sazgaar’s electric rickshaw as the basis for comparison. This is because it is the most widely available commercial three wheeler on the market. The electric rickshaw comes in three different models: base, mid tier, and high tier. These retail for Rs 720,000, Rs 825,000, and Rs 925,000 respectively. How much more expen

sive are they in comparison to their combustible engine counterparts? Based on our market research, Profit found that the average petrol rickshaw in comparison retails for roughly Rs 275,000.

However, for a fair comparison we utilised Sazgaar’s Deluxe and Royal Deluxe rick shaws. These two retail for Rs 315,000 and Rs Rs 344,800 respectively. Averaging out everything to account for different possible purchase combinations, the average electric Sazgaar retails for Rs 493,433 more than its combustible counterpart. This amounts to a 60% premium.

That is problematic, very problematic actually. Rickshaw drivers constitute perhaps one of the most, if not the most, price-sensitive segments in the automotive industry. You know what’s more problematic? This is where the battle between idealism and reality first takes place.

“Unless there is an outright ban on petrol rickshaws, I do not think electric rickshaws will be successful. 10-15% of drivers will switch. At max you will see 20% of them switch.”

Ghauri told Profit. In contrast, Mian told Profit that “Electrification makes perfectly good sense from an economic and environmental point of view”. How do we reconcile these two juxtaposing points of view? Cost is the lowest common denominator between both arguments so let’s start from there.

“A regular rickshaw consumes Rs 1,500 per day, that is Rs 45,000 a month, and Rs 500,000 annually. It is a vehicle that you buy for Rs 350,000 which gives a bill exceeding the price of the vehicle itself in just 10 months after purchasing it. Electric rickshaws in contrast have the potential to bring down the cost to 20% of that.” Mian told Profit. This and its comparables are the linchpin of the argument that electric rickshaws make to prove their superiority over their combustible engine counterparts. This is also the first thing that Profit will look to put to the

What does a man do when he is on the verge of committing suicide? Right when he has nothing, when there is no food on his table and he watches his children starve, what does he do? That is when he becomes a rickshaw driver. Not by choice, but by necessity

Ghauri, Chairman

So, are electric rickshaws cheaper? We already have our answer for the shortterm in terms of up-front costs, so let’s look at how they fare in the long-run before we get back to this.

The aforementioned Deluxe Mini Cab and Royal Deluxe may vary in terms of engine displacement but they both have an average of 32 kilometre per litre of petrol consumed. Utilising a price of Rs 224.8 per litre for petrol, they incur a cost Rs 7.025 per kilometre. Now onto our electric contestants.

Methodology (feel free to skip):

Profit sought to find the cost per kilo metre as well for the electric contestants to make the comparison fair. Here Profit took the tariff rates provided by the Islamabad Electric Supply Company (IESCO). Why IESCO in

of YES Electromotiveparticular? They just had the easiest navigable website. Take cues Lahore Electric Supply Company (LESCO), please.

Profit then looked at the rates for all res idential and commercial units available. Here it is important to note that electricity tariffs in Pakistan work on a slab basis. What does that mean? That means the tariff levied on you, in your bill, for a unit of electricity consumed depends upon the slab you fall in. The slab that a customer falls in depends upon the overall units of electricity consumed. The more units of electricity you consume, the more you will be charged per unit, and vice versa.

Profit utilised all residential and commer cial rates to account for all use-case scenarios. Interesting tidbit about which slab users are actually using electric rickshaws later on.

Profit multiplied the Rs kWh (the cost of a unit of electricity consumed) for all slabs with the total battery capacity for all three of the electric variants. The battery capacities that were multiplied were also adjusted for inefficiencies that occur in transmission between the charger, battery, and discharging. Profit accounted for 10% inefficiency recom

mended by Zubair Khaliq, Director and CEO Multiline Engineering. This allowed us to find the total cost of charging the batteries of the rickshaws from 0-100. We then divided the cost by the total range the batteries could provide to find the cost per kilometre. What were Profit’s findings?

Electric rickshaws were cheaper than their conventional combustion engine coun terparts irrespective of the tariff slab. How much cheaper? At minimum the rickshaw driver would reduce his fuel cost per kilometre by 68.01% or Rs 4.8 per kilometre travelled, and at maximum the rickshaw driver would save 93.3% or Rs 6.55 per kilometre travelled. How much does this translate into when running the rickshaw day to day?

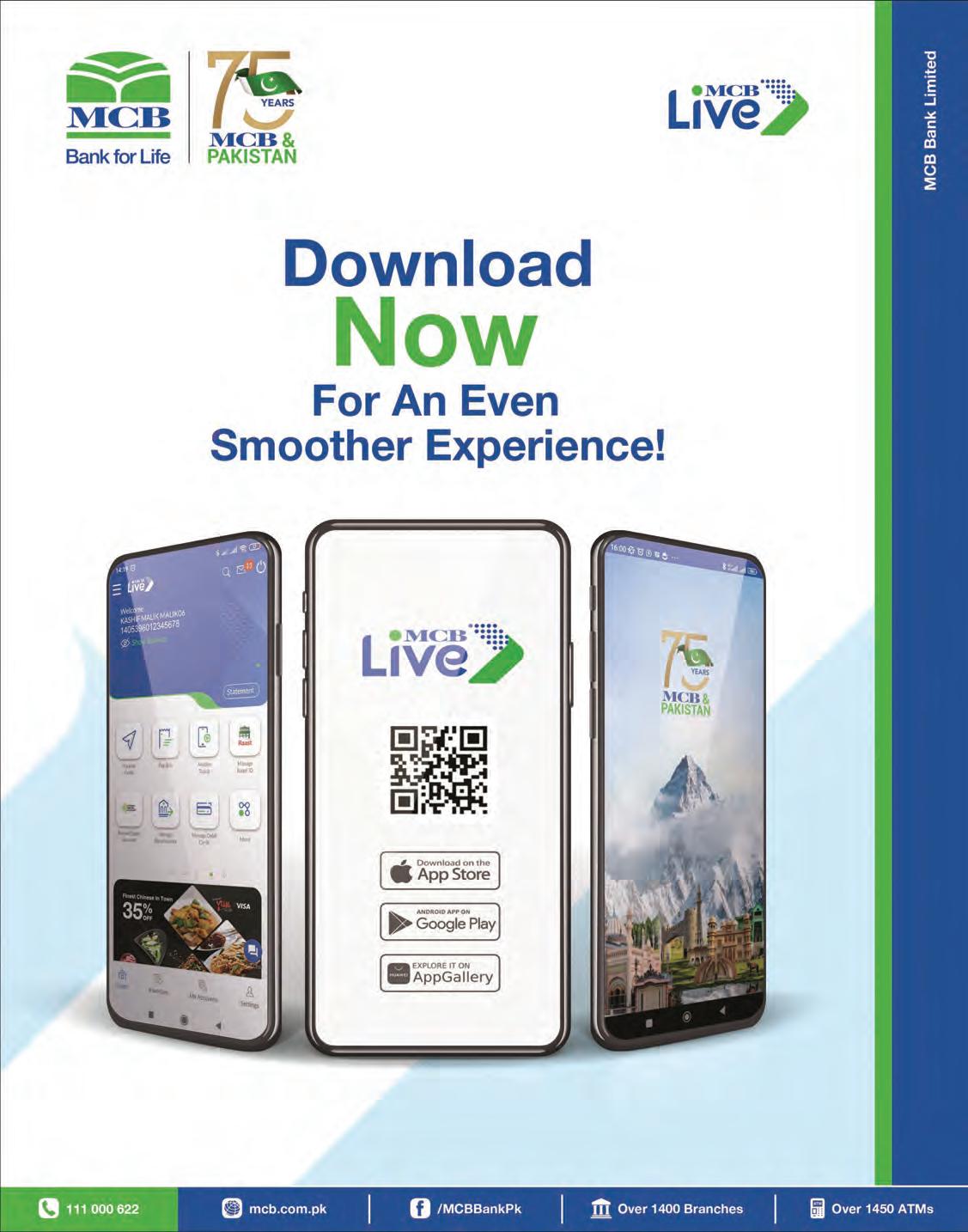

The base model has a charging time of 4 hours and covers a total distance of 100 kilometres on a full charge. The mid and top tier models both have charging times 5 hours and cover 160 kilometres and 210 kilometres on a full charge respectively. Given the charging times, Profit assumed that each variant could be used for two trips a day, utilising the complete range of the batteries for each trip, given the total 8 and 10 hours needed to charge them twice. Profit found that given these assumptions, the rickshaws at minimum would save Rs5,733 per week and at maximum could also provide Rs16,516 worth of savings if used instead of their combustible engine counterparts.

Finally, Profit sought to identify the payback period the rickshaw driver would have to meet in order to pay-off the premium associated with their more expensive rickshaw based solely on the savings from switching to electricity from petrol. This calculation was in line with Profit’s assumptions that the electric rickshaw would be driven twice a day. Furthermore, we assumed that it would be utilised for six days a week. Why six? Irrespective of whether it was used directly by the driver or leased out, we took the liberty

test to see whether these electric rickshaws can take off or not.

Internal combustion engines cannot be converted to electric. Simple as that. It’s not a conversion issue. You cannot put electrons in a carburetor and say that this will henceforth run on electricity. You will need to build a proper electric vehicle

Hasan Mian, Founder and CEO

If you ask a rickshaw driver to pay Rs 600,000-650,000 for a rickshaw and they have a son who’s come of age, then they are likely to ask why not just get an additional conventional rickshaw for their son to add to the family’s income stream?

Waseem Akram, Director at the Transport Planning Unit in the Punjab Transport Department

to assume that the owner of the rickshaw, not the driver, would not want to be associated with it for all seven days of the week.

In identifying the premium, we averaged the prices of Deluxe and Royal Deluxe. We did this because we wanted to account for the chances of the buyer opting for either of the two variants. The average price worked out to be Rs 329,900 between the two models. This average price was then subtracted from each individual electric rickshaw to identify the premium that would sought to be recouped via the savings.

Profit found that the earliest the buyer could payback this amount was 36 weeks whilst the latest would be 68 weeks. Beyond the requisite time period, the savings will then magnify the profits the owner will enjoy. How much? We do not know because Profit did look into the fare cost charged to passengers

per kilometre driven as there is no such fixed amount across Pakistan. So, all good then? Not really.

Firstly, everything centres around rick shaw drivers saving additional expenses they would have otherwise incurred by switching to electric. However, that is largely it. There is no guarantee that rickshaw drivers will be able to charge higher fares to their passengers for the utility of riding this newer and fancier rickshaw simply due to the nature of the market they put in. Subsequently, the entire sales pitch to rickshaw drivers is then that they can enjoy lower operating costs in exchange for a one time higher upfront cost.

“This is a unique economic entity which makes you poor and keeps you poor as an individual and as a society. It bleeds income. Having a low upfront cost, you have basically acquired a ball and a chain.” Mian tells Profit

The question then is, will they bite?

“If you ask a rickshaw driver to pay Rs 600,000-650,000 for a rickshaw and they have a son who’s come of age, then they are likely to ask why not just get an additional convention al rickshaw for their son to add to the family’s income stream?” Waseem Akram, Director at the Transport Planning Unit in the Punjab Transport Department, told Profit. These are valid reservations. What about the savings from the cost of operations? Well, these might be very hard to explain to customers. If for nothing else, because rickshaw drivers have alternatives to electric already.

“LPG rickshaws have the same benefit, electric rickshaws are not novel in any way. Their only benefit is that they reduce pollution, and so they’d help us in getting rid of smog. You can have a conventional rickshaw fitted with an LPG kit for Rs 15,00020,000 and you would save signifi cantly more money.” Ghauri told Profit

“The only downside is that the LPG cylinders are hazardous. If the Gov ernment could give us access to OGRA (Oil & Gas Regulatory Authority) cer tified cylinders then that would be a better alternative to electric rickshaws altogether.” Ghauri continued.

It is very clear that irrespective of the additional cost savings, rickshaw drivers either lack the means to fork out the capital needed to purchase these expensive vehicles or already have other things they would rather allocate the same amount of money on. However, it’s not like companies are not cognisant of this. “In our society where you have high interest rates and there is a lack of abundant cheap financing. The two and three wheel market is not served by banks, it is served by informal finance with very high interest rates. When you have a high upfront cost and lower operational costs then spreading the cost over an easy instalment plan would allow us to overcome a key hurdle in electrifica

tion.” Mian told Profit

So, where are our banks? The modern banking system’s raison d’être after all is to bridge financing gaps. One can even ask why rickshaws aren’t incorporated into existing car financing schemes. Profit even confirmed with Muhammad Iftikhar Javed, Business Head of Secured Lending at Bank Alfalah, that a repayment schedule for a three-wheeler loan, if it did exist, would be “100% identical” to that of a car financing loan.

However, there is a good reason as to why most of us have never seen a bank adver tise rickshaw financing schemes in any form of media.

Okay to start off. Banks are not big on this for a myriad of reasons. “The banks don’t get involved in 3-wheel financing as they deem it too risky. However, the opportunity is there for banks to step in and take a big chunk of the market.” Hameed told Profit . So, are there no lenders at all to reduce the cost of buying a vehicle at all? Profit asked Hameed about the matter to which he responded that “The three wheel finance market is currently run by individual investors and dealers.”

Who are these dealers and investors that operate in the absence of banks? Your local Joe’s to be honest. They can be your friends, family, affluent neighbours, or just your local loan shark. There is no set defini tion or archetype for who these lenders are because they all operate in the informal sec tor. The only commonality is that they charge higher interest rates than banks, but they also cater to the rickshaw drivers in manners that banks cannot.

“They deal with them based on their specific requirements, they handle the courts and police stations, and they resort to phenti when required to recover the rickshaw.” Javed told Profit . “All of this is not possible for banks to do.” Javed continued. Assuming banks were to get in on this, there are still many problems that would need to be addressed.

“Rickshaw buyers are generally going to be uncomfortable with the documentation banks require. Most people are unable to meet the terms and conditions for having a car financed, how will they (banks) convince rickshaw buyers to sign up? How will rickshaw buyers produce guarantors for their loans?” Akram told Profit . Again these reservations are completely understandable. “Buyers in this segment are unlikely to have very established businesses. In the cases that

they do, those businesses are unlikely to be properly documented. This will create repayment challenges.” Javed echoed similarly to Profit

Irrespective of this, rickshaw companies will likely have to convince the banks in some way to entice them. Why, you ask? It goes back to the higher cost of informal financing. “If we assume that banks provide any product to you today at a cost of 18%. The same thing if your friend, neighbour, or anyone in the informal sector provided you, then they would provide you the option to have split over six instalments. However, when they do it, the cost will shoot through the roof.” Mian told Profit . Is there a practical example of this that would help everyone understand things better? Ghauri explained to Profit how a typical rickshaw buyer goes about financing their purchase, “Family members will lend you Rs 50,000-60,000 to help you out, and when you go to a dealer then they will provide you with the oppor tunity to split the remaining Rs 70,000 over a few instalments. People end up pooling finances like this and happily buy rickshaws, however, they end up paying Rs 400,000 or so for something that originally cost them Rs 250,000.”

The informal sector provides our electric rickshaw companies with a unique problem. “What will someone buy when they have expensive instalments? Whatever is cheaper upfront. Whenever something has a higher initial cost, you need formal financial institutions to get into the game to spur sales.” Mian told Profit . So, whether they like it or not, electric rickshaw will somehow have to woo the banks.

However, let us assume that somehow all of this does manifest and we have rickshaw buyers signed up to purchase the fancy electric rickshaws through a bank. Will it work then? “You will only have 25% of rickshaw drivers meet any repay ment obligation. No rickshaw driver will fulfil the repayment obligations

Currently the biggest hurdle we face is that the provinces are not allowing the registration of electric 3-wheelers. This is quite bizarre as there is a federal electric policy in place yet our customers still face registration issues

Ammar Hameed, Director at Sazgaar Engineering Works

after the second or third payment. You will eventually have a political leader forgive the debt taken on by rickshaw drivers, leaving the banks in ruin. Ghauri told Profit . “At best you will have 50,000-70,000 rickshaws on the road through any financing scheme” Ghauri continued.

So we have our answer. However, herein lies the solution as well. Utilising a conventional to finance rickshaws is not just a bad business decision but it would also be unfair to do so. “It would be unjust to the rickshaw driver if you were to attempt this sort of financing at today’s cost of 21%” Javed told Profit

What if we tried something bespoke for all of this? This would not be entirely uncharted territory for banks after all. “Banks lent billions of rupees in the previous 3-4 years for low-cost housing. This was a very high risk segment for 3-5 marla houses. However, with that the banks were satisfied with the credit guarantees provided by the Government of Pakistan, State Bank of Paki stan, and the Pakistan Mortgage Refinance Company.” Javid explained to Profit . “This would not be a normal product. It would be a special product that would need to be operat -

ed on a project basis with the Government and State Bank of Pakistan being directly involved for it to work.” Javed continued.

Let’s do a recap now. What have we learnt? Banks don’t serve the rickshaw mar ket because they don’t want to be caught in the quagmire. In their absence, the informal sector serves the market but charges very high interest rates. Large repayment amounts incentivise buyers to only go for those prod ucts that have smaller upfront costs. How ever, can banks do it? Yes, they have done something similar. The only thing is that they need Governmental level guarantees and support to do so. Is the Government interested in this? Yes. Perhaps someone just needs to perform the matchmaking role between the Government and the requisite entities needed for the space to take off?

ground. The companies,thankfully, are cognisant of this as well. What are they doing apart from potentially wooing the State and financial institutions? Well, they are try ing to devise creative business plans. Let’s run through a few that Profit found when researching for the piece.

“We are planning on launching a battery swapping model in which the driver does not own the battery and instead he rents it out. Once the battery is dead they can head over to the nearest battery station and replace their battery in a matter of seconds. This will help with the overall cost of the vehicle as the battery motor and controller are the costli est items. More importantly the driver will not have to wait for their vehicle to charge.”

So, where are we at now? Well, ceteris paribus, electric rickshaws are not going to take off at their current retail prices. Changes will be needed in the external environment to get this off the

Elsewhere, Mian told Profit that, “Selling to individuals is problematic so we have lined up fleet operators in Lahore and Karachi to whom we will roll out our product.”

Perhaps the note to end this is a tidbit that Profit found when researching for this piece. This is also why we looked at all electricity slabs and not just the lowest. When talking to the sales team for an electric rickshaw, Profit inquired with them about the current set of customers, and if any customer would be willing to be inter viewed. Profit was humorously surprised at the response, “Sir, it will be hard for us to put you in contact with them. Most of the non-corporate customers (they only men tioned two companies) are very wealthy individuals who value their privacy.” When Profit inquired why such wealthy individuals were buy ing rickshaw of all things, we were told that “They have just bought the rickshaws to have their domestic staff fetch their groceries because of the novel ty the rickshaw provided.” n

It seems we don’t have lift-off

They deal with them based on their specific requirements, they handle the courts and police stations, and they resort to phenti when required to recover the rickshaw

here does the money in your wallet come from? It starts in the cotton-field. All over Pakistan, in the Kapas belt that stretches across southern Punjab and into Sindh, farm workers bend low to pick cotton seeds. They fill the wicker baskets on their backs until they are full before loading them onto carts, cars, and trucks that transport them for processing. The cotton is sent for ginning, turned into bales, and eventually spun into yarn.

Yet somewhere in the middle, when the cotton is being separated from the seeds it grows on, something else happens. Little bits of cotton stay stuck to the seeds. While the rest of the fine, white, fabric gets spun and turned into clothes and other items, these little strands that stay stuck to the seed are called ‘cotton waste’ — and this is where your money comes from.

You see, all bank notes are printed on something called ‘security paper.’ This is a special kind of paper that incorporates features that can be used to identify or authenticate a document as original such as watermarks and magnetic strips. Essentially it is paper with “built-in” identification features. Academic transcripts, degrees, birth certificates, and bank notes are all printed on this cotton paper.

And that is where our story starts. The sole supplier of security papers in Pakistan is the Security Papers Limited (SEPL). Through a myriad of connections, the company is owned and managed indirectly by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). For decades, it has been the only company providing these papers and has maintained profitability. Last year, in the wake of Covid-19, the SEPL faced a rare jolt. Dividends went down, some shareholders expressed unhappiness, and the company had to see through low gross margins. Now, the company’s chairman has told Profit that they are looking to de-risk their investments and in crease their capacity so they can diversify their customer base. So what happened, and how is SEPL going to fare in the years to come?

The SEPL was incorporated in 1965 as a Private Limited Company. Up until this point, money in Pakistan was either produced at the Pakistan Mint in the shape of coins or it was printed on imported security paper. The same was true for things like bonds and college degrees. In 1967, however, things changed. The SEPL became a joint venture between Pakistan, Iran, and Tur-

key with the latter two holding 10% ownership each while Pakistan controlled a majority 40% share.

WThe company began commercial pro duction in 1969 and immediately became the main source in Pakistan for security papers.

As a national strategic industrial organiza tion, it produced the paper that was used to print prize bonds, defense savings certificates, non-judicial stamp papers, passport papers, cheque Books, and even ballot papers.

As the population grew, the demand for such paper increased as well. A new state-of-the-art Paper Machine (PM-2) was commissioned in 2003 which gave SEPL the capability to produce high-quality specialized banknotes and other security paper of interna tional standards. Over the years, the company continued to expand and improve its facilities and plants. It installed a Reverse Osmosis Plant, commissioned new power plants, and upgraded its existing manufacturing facilities. In 2019, capacity enhancement of the existing PM-2 was done through in-house development which resulted in the highest ever production in 2020. Currently, the company can supply over 5,000 tons of security paper per annum — which is expected to be tested when the company is given the orders to produce ballot papers for this year’s general elections.

The company’s main client, however, was and has always been the Pakistan Security Printing Corporation Limited (PSPC). The PSPC is responsible for printing banknotes and prize bonds. Interestingly enough, the PSPC is not just a customer of the SEPL but also has a 40% shareholding in the company. The PSPC was controlled by the finance ministry until 2017, when it was acquired by the SBP for Rs 100.49 billion.

After the acquisition, PSPC now only prints banknotes and prize bonds while the remaining printing of official documents, passports, certificates are done by NSPC, Nadra and other government departments. Since then, the SBP has controlled the PSPC with its governor serving as chairman of the corpora tion, and indirectly also controlling the SEPL. This gives the central bank complete control not just over the printing of money but also the management of the paper it is printed on.

And because PSPC holds 40% shares in SEPL, the chairman of SEPL is also a nominee of PSPC, Mr. Mohammad Aftab Manzoor. The previous chairman of SEPL, Mr. Muhammad Haroon Rasheed, became the managing director of PSPC. Recently, a new CEO was appointed at SEPL, Mr. Imran Qureshi on 15th

September, 2022, in place of Mr. Mohammad Arshad Butt, who was also a nominee of PSPC. PSPC withdrew the nomination of Mr. Butt after which he had to leave

ur role has simply been to provide security papers to the State Bank of Pakistan. There is a long history behind this, but at the end of the day this is what the SEPL has been doing”, says Aftab Manzoor, chairman of the company. A seasoned banker, he does not run the company which is the job of the CEO. However, he knows the ins and outs of the business of security papers in the country. “This is a very profitable company providing an essential service”.

In that he is correct. The SEPL has generally been a financially healthy institution. But it is worth looking at some of its recent financials. During the financial year 2021-22, the SEPL had sales of Rs 5,147 million against volumes of 4,176 tonnes, registering a minor growth of 2.91%. It’s EPS declined to Rs 16.47 against Rs 24.61 the previous year. The company has a paid-up capital of Rs 592 million, free float of 40%, and a market capitalization of almost Rs 6 billion.

It also announced a 100% dividend (Rs. 10 per share) against 90% the previous year. However, when considered as dividend payout, this only forms 62%. Over the past few years, the company has not increased its dividend payouts as its EPS has increased. Consider the following table.

“The investments in Shariah Compliant Mutual Funds had generated attractive returns during 2017. However, in the subsequent period the returns on these funds were affected by the performance of the equity market”

We see that for the past 7 years, the company has given dividends around Rs 8-10 per share even when the company registered EPS of over Rs 20. When these are compared with the cash flow of the year at the end of every subsequent year, it raises the question why is the company not giving out higher dividends in the past few years and instead keeping hold of liquid cash. The company has said that much of this has not been payable as dividends and it has also faced the crunch because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“One also needs to understand the circumstances of last year. Other than the bank notes, the requirement for our security paper for passports and educational certificates etc was low due to Covid and travel restrictions”, the company secretary said in a response to Profit

That said, things may also be looking up. In the current year FY23, the company

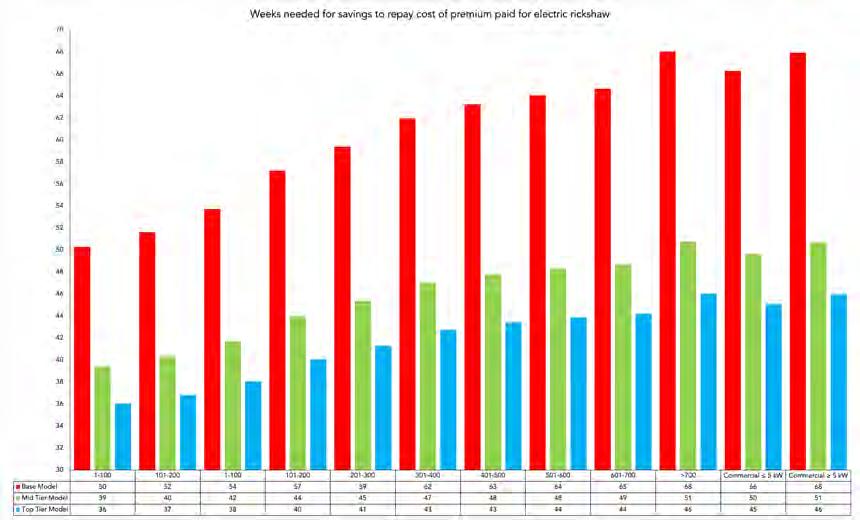

A closer look at the annual reports show that in 2017, almost Rs 600 million was poured into six different mutual funds. The units invested in 2017 and their value in 2022 can be seen from the table.

units in NBP Islamic Sarmaya Izafa Funds, Meezan Balanced Fund and Meezan Strategic Allocation Plan-1 in the Financial year 2021 and 2022 by more than Rs 500 million approx. and also substantially trimmed the ratio of investments in fixed income securities Vs. Mutual Funds from 53:47 in FY 2020 to 73:27 at present. Kindly note that these investments are in top rated mutual funds which are expected to generate attractive returns in the long run” explains the company secretary in a response to Profit

has also managed to secure a big order from the Election Commission of Pakistan for the supply of secure Watermark Ballot Paper, which is an effort towards diversification of their products and customer base. Our sourc es tell us this order will have a sales volume of over 2000 tons which can result in higher profitability for the company this year.

The Company has Rs 6,545 million as reserves as at June 30, 2022 depicting a positive and healthy financial status. The Company has Rs 1,785 million of fixed assets as at June 30, 2022, constituting 20% of total assets of the Company. Total inventory of Rs 561 million was reported.

A closer inspection of the company’s in vestments and standing is also worth taking a look at.

The first thing worth exploring is the company’s investment trends. In 2017, SEPL increased its investments in mutual funds to Rs 1,502 millions from Rs 904 millions, an increase of almost Rs 600 million. Today, five years down the line, the total value of the invest ment in these mutual funds have declined to Rs 802 million, a staggering loss of almost Rs 700 million, not accounting for the potential profits that are lost.

From the table, we see that by 2022, investments from three mutual funds were completely pulled out (although they pulled out very late) and partially put into the three remaining funds. A closer look at the partic ulars of the three mutual funds shows that SEPL increased its units of investment into these funds even though all of them showed a decline in their absolute value.

As of Nov 2022, the three mutual funds in which over Rs 800 m of cash is invested by SEPL have given the following absolute returns since mid of 2017: NBP Islamic Stock Fund (-12.89%), Meezan Islamic Fund (-20.01%), and NIT Islamic Equity Fund (-33.19%). These figures should raise enough doubts in shareholders about SEPL’s ability to manage its investments.

The mutual funds loss is alarming. If the SEPL, instead of investing in mutual funds, had invested the Rs 1.5 billion in a fixed income instrument with a stable interest rate of 11-12%, in five years, that investment would have easily given over Rs 1 billion in returns, bringing the original investment to over Rs 2.5 billion — money that could have gone towards dividends.

“The investments in Shariah Compli ant Mutual Funds had generated attractive returns during 2017. However, in the subse quent period the returns on these funds were affected by the performance of the equity market. Furthermore, we had redeemed

Essentially, the company invested in these funds at a time when they were hot on the market, but the subsequent years saw a dip. “If you know the history, everyone made a lot of money off these funds a few years ago. Our investment portfolio was a well-thought out decision looking at the climate of the time, but in the subsequent years we lost money,” explains the company’s chairman. “That said, our investment committee is looking to invest the surplus we have in safer avenues. A decision has been made to de-risk”.

This was further explained by the company secretary who said a board level investment committee closely monitors the per formance of these investments. “Earlier, the Committee had decided to hold on to these investments because things were getting bet ter, so hopefully, we would be able to recover losses, if any, in due course of time. Further more, this matter also came under discussion at the recently held Annual General Meeting of the Company wherein it was suggested that the Company should also consult industry experts in this matter. Accordingly, we have established contacts with some investment advisors who will present various options to our Investment Committee to manage these investments”, reads the response.

Then there is the question of land holdings. The SEPL has two parcels of land in Ka rachi: one in Malir halt and the other in DHA. The first consists of freehold land of 20 acres and 60 square yards at Jinnah Avenue, Malir Halt. On this parcel of land is the registered office and factory of SEPL. It also includes the offices and factories of SICPA Pakistan

“There have been some challenges in the recent past. I’ve already mentioned that the demand for passports went down and that is also something that needs to be understood. While we are the sole providers of security papers in Pakistan, this is not a commodity product. We are totally dependent on the orders that the SBP places with us”

Aftab Maznoor, chairman

(sole producer of security ink) and PSPC (sole printer of banknotes). A 20 acre piece of land is huge, but according to SEPL’s annual report of 2022, it has the remarkable value of just Rs 231,000. That is clearly a misrepresentation, and some shareholders have apparently com plained that the land should be revalued.

“We have three units in Malir, PSPC, one which makes ink, and the FPL. The gov ernment gave a special grant for this zone and this land can only be used for those purposes. We have seen this in the world of banking before, where some defaulting clients had properties in the middle of town but they had a specific purpose. It is the same case with our land. Frankly, revaluation is only done when a company is having issues like bank loans, and we have ample facilities. These properties cannot be used to pay dividends either, so revaluation makes no sense for us” says Aftab Manzoor.

He is not wrong. Security Papers is categorized as a Key Point Installation Category 1-A by the government of Pakistan. As a Key Point Installation 1-A, no structure can be raised at least within 200 yards of the company without the prior clearance of the KeyPoint Intelligence Division (Inter Services Intelligence). Also, the Category 1-A is a key point whose structure or services are of the highest importance to the war potential and whose total loss or severe damage might have disastrous effects on the both national war efforts (owing to the lack of any alternative source).

The question then is, does the ac counting standard IAS 16 apply to this key installation point? According to International Accounting Standards 16 (IAS 16), which deals with Property, Plant, and Equipment, companies are required to account for their properties either at a cost or revaluation model.

The revaluation done every few years gives a fair market value to the fixed assets. According to the note in the Annual Reports of SEPL, the company is using a cost model in this regard.

The second parcel of land is a leasehold area of 1,193 square yards with a building at Plot No: 25-B, Central Avenue, Phase II, DHA Karachi. According to sources, this house is used for the residence of ex-CEOs of Security

Papers. This has also been a point of conten tion for shareholders. The book value of this land as of recent reports is only Rs 417,000, which also means that the cost model used by the company gives a 1,193 square yards house in DHA Karachi a higher book value than 20 acres of land in prime commercial area of Malir Halt.

“The Company had acquired this house for the residence of the Chief Executive Officer in 1979. The Company has provided this facility to its CEO in line with the best prac tices whereby a number of good companies have extended similar facilities to their CEOs.

This property is a good real estate investment by the company (investing in real estate is a normal practice by corporates) and will be revalued if and when required by the company for any strategic reason”, the company secretary told Profi. While this one may raise more eyebrows than the land in Malir because of its use, there is nothing really inappropriate about it — although it makes sense why shareholders would be peeved.

It should be noted that rental accom modation can also be provided to the CEOs without the need to buy a whole house in a prime location, which also gives no rent or returns until and if it is sold. No doubt the property is a good real estate investment, but it would help to give a more fair value to the shareholders and public, whether or not the company intends to sell it anytime soon.

If we consider the past 25 quarters of the company, a time period of around 6 years, we see that the average gross margins of SEPL have been stable at around 36%. This stability in margins is because SEPL is the sole supplier of security papers with a stable clientele and demand.

But if we look at the past two quarters of the company, 1QFY23 and 4QFY22, we see that these margins have declined to 23.8% and 19.9% respectively. It raises the question: how is it that a manufacturing company which enjoys a sole monopoly and stable demand for its products suddenly experiences a sharp decline in gross margins?

“We have gross margins in an excess of 20%. Dips and rises are all a part of business, but even at this point we clearly have a situation where we aren’t just floating,” says Manzoor.

“There have been some challenges in the recent past. I’ve already mentioned that the demand for passports went down and that is also something that needs to be un derstood. While we are the sole providers of security papers in Pakistan, this is not a commodity product. We are totally dependent on the orders that the SBP places with us”.

If we consider the sales and cost of sales of these two quarters, we see a Rs 140 millions increase in cost of sales in 4QFY22 followed by a Rs 70 million decrease in the next period, whereas the sales revenue has declined in both of the last subsequent quarters. Why has the cost of sales increased while sales revenue has relatively declined? A possible explanation is that since security papers operates at a cost-plus-margins pric ing strategy, it didn’t raise its margins as its costs increased.

Surely, when Profit reached out to the company for a comment about the low margins in the last two quarters, they said that this decrease in margins happened because of a price review discussion going on currently for their main products with their major customer. They also said that they expect the margins to improve after the discussion concludes towards the end of this year.

This comment by the company suggests that the second quarter of FY23 will also report poor margins and only in the 3rd quarter the shareholders may get to see higher margins. This will also affect the overall financial performance of the company for FY23. Pricing discussions are normally done before the period starts so that the company enjoys stable revenues in the near future, but for some reason it has been over 2 quarters (half a year) and there has been no agreement on pricing by the company with its main customer.

The SEPL regularly posts profits, and gives its shareholders dividends. However, it is clear that there is more that could be done with the company. While there have genuinely been some conditions out of the hands of the management, more controls of margins and better investments could make a company that has been profitable for a long time even more profitable. The company is in a sweet position where it is the sole proprietor of security papers in Pakistan. While it is doing well, with the advantages it has, it should aim to do better. n

Our policymaking over the last few decades, if not more, has largely been devoid of any rational economic thought. Economic problems are solved not by thinking them through, but through band-aids, and knee-jerk reactions. Fixing the price of any commodity, or service is one such tool that has been abused to no end and has consistently led to unfavorable economic outcomes for the country, and the population at large. Whether it be fixing the price of an agricultural commodity, an energy source, medicine, or a mundane service –there has never been a case where a price floor or a price ceiling has led to better economic outcomes for the consumer. It mostly leads to the creation of an ecosystem where a chosen few benefit from the inefficiencies in the system, while welfare loss is borne by the consumer.

In a price floor, the government sets a minimum price below which any commodity cannot be sold, eventually making the government the buyer at that specific price to ensure the price doesn’t decrease further. Due to such a price floor, the consumer cannot benefit from lower prices and has to buy more expensive products relative to what they can buy if there wasn’t a price floor. A relevant example here is the support price that is given for wheat in the country. Devoid of any economic rationale, sup port price for wheat is rooted in the desire to ensure food security. However, food security cannot be attained through a price floor only. It needs massive investment in the supply chain, and stor age infrastructure, such that any surplus can be stored so that it can be utilized in subsequent years when stocks are running low.

To ensure food security, the local price of wheat was higher than international prices for a large part of the last decade, with even the poorest segments of society paying a high price for wheat. The government, to ensure the presence of a price floor, became the largest buyer of wheat, borrowing heavily from financial institutions to make such purchases, only for the same to be either wiped away or smuggled. As international prices increased,

it only took a few months before there was a shortage of wheat locally as suddenly stocks started disappearing, or were smuggled away to banks on the arbitrage available between local and international prices. Similarly, as recent floods have demonstrated, millions of tons of wheat stocks have been lost as they were not stored in adequate facilities, and were simply lying out in the open, exposed to nature’s elements.

The objective of ensuring food security was noble nonetheless, but the tool used to ensure that same was not appropriate, resulting in a transfer of wealth from the most vulnerable households, and the government to a few specific segments. In effect, a price floor takes away the incentive to invest in improving yield, productivity, or supply chain infrastructure resulting in long-term productivity losses, as the benevolent government keeps funding such purchases with more debt.

Due to such distortion in the market when prices increase, the government institutes price monitoring committees, as the district commissioners get opportunities for photo-ops, not realizing that price increases are more of a supply chain problem that can be fixed with supply chain infrastructure and sound economic policy rather than photo-ops. The cycle continues till another commodity becomes the flavor of the week, and photo-ops are repeated.

Another example is price ceilings, where a government fixes the price of the product, above which it cannot be sold. In such a scenario, a shortage of that product is imminent resulting in more welfare losses for the consumer, while the government can proudly pretend that a price ceiling is actually working while the available quantity dries out at the fixed price. A recent example of the same is how the government fixes the price of medicine. Considering the largely inelastic nature of medicine, a strong regulatory regime is certainly essential, however, it is also important that the same regime is nimble, and works for consumer welfare through encouraging investment in infrastructure, and backward linkages. Attacking the lowest hanging fruit of price creates more problems than it solves.

As the PKR has depreciated significantly against many global currencies during the last six months, the active pharmaceutical ingre dient of many medicines which is imported has also increased in price, resulting in a higher cost of production. However, as the retail price is fixed, beyond a certain threshold it doesn’t make economic, or financial sense to produce much medicine, resulting in potential shortages. There exists a moral argument that medicine should continue to be sold even at losses during times of crisis – that is certainly true, however, the same is not sustainable. This is where heavy investment in supply chain infrastructure and technology is essential to localize critical raw materials to reduce dependence on the import of key medicine. However, due to an archaic and anti-competitive regulatory regime, there has been massive divestment from the pharmaceutical segment in the country. As hypothesized earlier, price ceilings cause more problems than they solve.

The writer is an independent macroeconomist and energy analyst.

Fixing prices is an easy win for the short term, and for photo-ops. Fixing the supply chain which results in better prices, and better welfare outcomes for consumers and produc ers alike is a complex policy-oriented process. Any government serious about fixing issues needs to stop relying on fixing prices to fix problems. The problem isn’t prices, the problem is fixed prices. n

Not many saw it coming. But, in retrospect, perhaps they should have.

Last week, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) jacked up the benchmark policy rate by 100 basis points (bps) to 16%, leaving many marketwatchers flabbergasted.

Most surveys in the run-up to 2022’s last scheduled Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting predicted that the central bank would leave rates unchanged. Not a small majority; a vast majority.

They were wrong, yes; but, according to most experts on the matter, they cannot be blamed for being wrong. And there’s something wrong somewhere when a decision of this magnitude is warranted but still unex pected.

In 2022, the MPC convened eight times to decide the policy rate. In January and March, it decided to maintain the inter est rate at 9.75%. In April, earlier than scheduled, the MPC announced an emergency meeting and rate hike of a whopping 250 bps, followed by a 150 bps rise in May and a 125 bps rise in July.

During this time, Reza Baqir, the former governor of the SBP retired, Murtaza Syed stepped up as acting governor; and the country battled political instability with a change in government. Following three meetings resulting in hikes, the interest rate was then at 15%.

In August, Jameel Ahmed, a veteran central banker was appointed as the Governor of SBP. The MPC decided to keep the rate un changed in the August and October meetings, before the hike in November.

Cumulatively, this means a 625 bps

rise in the calendar year 2022 alone, making the SBP one of the most aggressive rate-hiking central banks in the world during 2022, behind countries like Hungary, Sri Lanka, and Colombia.

To add to this, Pakistan has the seventh highest interest rate in the world, in the list with countries like Argentina, Zimbabwe, Ukraine, Angola, Iran, Ghana, and Uzbekistan.

It is also important to note that the last time the policy rate was this high was in July 1998 when the central bank set the interest rate to 16.5%. This was just some time after the Chagai nuclear tests Pakistan conducted resulting in sanctions and restrictions on the country’s economy.

The finance minister at the time was Sar taj Aziz, who was later followed by Ishaq Dar in November 1998. You may be wondering why this piece of information is relevant here. It is because Dar prides himself on his experience in dealing with the International Monetary Fund

The SBP has hiked the policy rate by 625 bps in 2022, bringing it to a 24-year high to battle inflation and suppress imports - but is it too little, too late?

SBP was compelled into increasing the policy rate for several reasons. First, it had been behind the curve with its reactive stance, and was forced to catch up as inflation, especially core inflation, continued to march upwards. A second compulsion came in the form of pressure from the IMF, which believescorrectly - that Pakistan’s policy framework is still too lax viz the external account challenges it faces

(IMF). “I have been dealing with the IMF for the last 25 years; I will deal with it,” he balked, referring to any potential reservations by the lender on Pakistan’s policy settings prior to the annual meetings organised by the IMF and World Bank in October 2022 shortly after taking over the finance ministry.

It is also relevant because many observ ers say that, keeping in mind the upcoming IMF review, it is likely that the MPC decided to hike the policy rate to show more macroeco nomic and monetary prudence – hoping for a smooth review, which remains pending.

“The decision of the last two MPC meetings to keep the interest rate constant might have given this impression to markets that this time too the SBP will not increase the rate. However, we also need to keep in mind that a policy rate increase is also an underlined requirement that the Government of Pakistan needs to meet before the IMF’s 9th review. The SBP cannot continue indefinitely with negative policy rates,” says Abid Qaiyum Suleri, the executive director of the Sustainable Develop

ment Policy Institute (SDPI).

“SBP was compelled into increasing the policy rate for several reasons. First, it had been behind the curve with its reactive stance, and was forced to catch up as infla tion, especially core inflation, continued to march upwards. A second compulsion came in the form of pressure from the IMF, which believes - correctly - that Pakistan’s policy framework is still too lax viz the external account challenges it faces,” says Sakib Sherani, Former principal economic adviser, Ministry of Finance and ex-member Prime Minister’s economic advisory council.

Hafeez Pasha, economist, former finance minister, and academic, however says that inflation remains a primary reason for the rate hike.

“Core inflation was approaching 15%. This statistic is linked more to demand and is a better indicator of demand. The MPC ideally tries to keep the policy rate slightly positive in relation to the core rate of inflation,” says Pasha. Core inflation increased since the previous MPC meeting further to 18.2% and 14.9% year on year in rural and urban areas respectively.

Sajid Javed Amin, economist and found ing head of Policy Solutions Lab also believes the SBP wants to show its commitment to

controlling inflation.

“A key reason behind rising policy rates is to increase the cost of importing,” says Pasha. The Current Account Deficit (CAD) has continued to moderate during September and October reaching $0.4 billion and $0.6 billion respectively. Cumulatively, the current account deficit during the first four months of FY23 fell to $2.8 billion, almost half the level during the same period last year.

Sherani agrees: “As much as inflation, a key concern for SBP is the continuing pressure on the balance of payments. Despite the reduc tion in the current account deficit in recent months, imports need to be contained further.”

Whatever the actual reason is, there is no getting past the fact that the SBP is sending mixed signals to the market, evident not only in way-off-the-mark predictions in surveys, but in the MPC’s statements.

A month ago, the SBP said “headline inflation is still projected to gradually decline through the rest of the fiscal year, particularly in the second half,” adding that inflation would fall towards the upper range of 5-7% medi

To some extent, the fiscal and monetary consolidation will be achieved by hiking policy rates. However, the question arises of how to balance the social spending in an economy that is already facing the threat of stagflation (growth forecast 2%, high inflation persistent) and consolidating vs consolidation through policy measures

um-term target by the end of FY24.

In the November statement, the SBP said: “The momentum of inflation also picked up sharply, rising by 4.7% (m/m). As a result of these developments, inflation projections for FY23 have been revised upwards.” But then adds that, “while inflation is likely to be more persistent than previously anticipated, it is still expected to fall toward the upper range of the 5-7% medium-term target by the end of FY24”.

These statements contradict each other as the SBP is saying inflation will gradually recede, while still saying inflation estimates have been revised upwards. Moreover, the medium-term targets of 5-7% are consistent and there seems to be no upwards revision in this regard.

It is important to consider why the market did not expect a rate hike. Why did the market expect the SBP to take sentiment or politically-driven decisions as opposed to statistics and economic fundamental-driven decisions? This is not a comforting question.

“The market was surprised, even though it wasn’t a surprise for me as I expected the SBP to hike nominally when inflation rises. Growth has slowed down and so the mar ket was expecting the SBP to align its goals towards growth. However, one can say that the SBP is now prioritising targeting inflation. There is a divergence in priorities between the market and the SBP,” says Amin.

To tackle this issue, Amin suggests that the SBP needs to be clear in its communica tion regarding inflation. “Well-designed and well-structured communication with the market may be more important than the policy rate at this point in time.”

However, in order to tackle inflation, rate hikes may or may not be the right way forward.

“Theoretically speaking SBP is still behind the curve. Practically speaking further hike in interest rate may not be very fruitful,” says Suleri.

He adds: “Rate hike will not address the problem of inflation. Ours is a cost-push inflation, triggered by certain external factors. Domestically, Supply chain disruption due to floods has also contributed to it. However, SBP needs to contain the demand to insulate the value of the rupee against the dollar coming under pressure. One can argue that hiking the policy rate is important at this stage to ensure the value of the rupee does not nosedive against the dollar.”

Echoing the sentiment, Pasha argues that the causes of inflation aren’t necessarily generated from higher demand. “It is primarily cost-push. Higher fuel prices result in higher electricity tariffs. With the upcoming gas tariffs, pressure will build up,” he says.

“If anything, aggregate demand has gone down while investor sentiment is also negative. People are unable to spend, which means the

problem is on the cost side,” adds Pasha.

While the policy rate has been hiked, any expert on the subject will tell you it is important for monetary and fiscal policies to work in concert to contain inflation. Keeping the flood situation in mind, it will be difficult for the government to cut back on government expenditures to keep a lid on the fiscal side.

“To some extent, the fiscal and monetary consolidation will be achieved by hiking policy rates. However, the question arises how to balance the social spendings in an economy which is already facing the threat of stagflation (growth forecast 2%, high inflation persistent) and consolidating vs consolidation through policy measures,” says Suleri.

Pasha however feels that the decision to hike the policy rate will add to aggregate demand.

“It is important to note that this rise in interest rates will contribute more to demand pressure as the cost of debt servicing goes up. We have to renew maturing domestic debt of Rs 19 trillion. Adding a 1% point to the interest rate means higher debt servicing costs. This is an additional cost on the budget and increases the deficit,” he says.

Policy levers can be confounding, and finding a balance is not easy most of the time. This was the last scheduled MPC meeting for 2022, which has been a rollercoaster ride for monetary policy amidst a multifaceted economic crisis. For most, 2023 does not look like it will be any easier – but it remains to be seen if, at the least, the apparent gulf between expectations and action, as well as policies and realities, can be bridged.

And most importantly, between action and reaction.

There’s a saying on the street: Larai ke baad yaad aney wala muqqa apne munh par maar dena chahiyay.

n

It is important to note that this rise in interest rates will contribute more to demand pressure as the cost of debt servicing goes up. We have to renew maturing domestic debt of Rs 19 trillion. Adding a 1% point to the interest rate means higher debt servicing costs. This is an additional cost on the budget and increases the deficit

Well-designed and wellstructured communication with the market may be more important than the policy rate at this point in time

Sajid Javed Amin, economist and founding head of Policy Solutions Lab

By Momina Ashraf

By Momina Ashraf

Palwasha Minha.

e come from very humble middle class families. We used to save up all year to travel within Paki stan but now we get travel for free even internationally. UAE has become like our second home and we have officially established our business there. Now we even have really good friendships in all the countries we go to for work,” says Rizwan Takkhar, who runs a photography business with his wife

Such a lifestyle would be familiar to consultants or diplomats with fancy university degrees, but Minhas and Takkhar are none of these. In fact, both of them are college dropouts who found their rags to riches story in the wedding photography business in Pakistan.

Pakistanis take knot-tying seriously. From food to guests to decor to clothes, everything is a careful curation and a project of a lifetime. Consequently, Pakistani matrimony is a serious business. You can not invest poorly in it and definitely can’t keep the business (the marriage) to yourself only. What’s the point of grandeur if it’s not a spectacle for the public? Pics or it didn’t happen!

There are a few problems in calculating the size of the pie when it comes to the wedding industry. For starters, we will go out on a limb here and say that the wedding industry is in fact one of the biggest industries that there are in Pakistan. However, this is not one holistic industry like steel or cement. It is an amalgamation of many smaller businesses and sectors. Just think, for a second, about what goes into the average Pakistani wedding.

At the very core you have the venue and catering. On top of that, you can then expect

the decor and flower arrangements. Then you have the clothes that the bride, groom, and guests wear to the events. And then there are the little details like cards, gifts, makeup, event planning and mithai. By the time all of the additions are made, it ends up being a pretty heavy bill — a massive flux of economic activi ty all directed by matrimony.

There is very little data for how big the industry is in Pakistan, but a peak across the border gives us some insight. In India, About 60,000 crore worth of jewellery is bought every year for weddings, 5000 crore worth of hotel rooms are booked every year, and about 10,000 crore worth of apparels are bought every

year. In 2016, Rs. 3.68 trillion was the estimat ed business the Indian wedding market made, according to a KPMG report. A more recent report from this year has indicated that the wedding industry is in fact the fourth largest industry in the country — competing with the likes of steel, textiles, and energy.

Out of this, a very small slice goes to the business of wedding photography. A 2022 report in the Times of India puts the share of wedding photography at a mere 3% of the overall cost of a wedding. However, when the big bucks are flowing even 3% can be a hefty sum. And with countless talented people out there looking to make a name for themselves, the field in the wedding photography business in Pakistan is lively, thriving, and lucrative.

The big events with a full day coverage goes up to Rs 250,000 per day. Mul tiply that with the number of days for each wedding, and multiply that with the number of weddings in the wedding season alone, and you have a booming business. And all you need to start off is a camera and some willingness to scrap it out.

It’s not a quick money-making scheme. Starting a photography business is like any other business. One invests a lot, emotionally and financially, before having the ball roll in their court. “Initially, I used to do events for my friends and family, and their friends and family. I used to charge really less and take whatever the client offered me. The events were small-scale home-based events and so I took whatever I was offered. I was just looking for work back then,” says Natasha Zubair, a young fashion photographer based in Lahore who does photography on the side. “When I started, the other bigger photographers in the event used to be quite patronising sometimes. They’d see a young girl with a camera and not take me seriously and tell me what to do rather than letting me go with my own flow,” she continues. But eventually in four to five years, Zubair developed a clientele that preferred her specific aesthetic and her schedule is now mostly jam packed.

“My standard rate for the couple shoot is

When I started, the other bigger photographers in the event used to be quite patronising sometimes. They’d see a young girl with a camera and not take me seriously and tell me what to do rather than letting me go with my own flow

Natasha Zubair, fashion photographerPhoto by Natasha Zubair

Rs 60,000 which includes 70 photos. I charge a little higher than the market price because I touch up all my photos as a fashion photo shoot,” says Zubair who encourages her clients to book her three to four months prior to the event.

Other than emotional investment, there is a huge financial investment in the business as well which often goes unnoticed. Minhas and Takkhar helped Profit break down some of the tangible costs of the business. “Just one camera costs somewhere around Rs 400,000500,000 and its lens costs an additional Rs 200,000-250,000. Both the camera and lens

start obsoleting within two years so a new one needs to be purchased. Hard drives and memory cards each cost Rs 30,000-35,000 and at least two need to be bought every month because saving the data is an integral part of the business. Other than that, if you have a team to cover a bigger event each person is paid at least Rs 10,000-20,000 per event. Then there is album printing cost and rents and maintenance of the studio which vary,” explains Takkhar.

“You can start off your career as a photographer with just one camera, but that means you’re working under someone in a team. But eventually you have to incur all

these costs to keep your business running,” says Minhas who also started off working for someone else.

Because at the heart of the big fat desi wedding is a marriage, everything is not just about money. “We meet our clients at least two times before the photoshoot so they get comfortable with us. On event days they spend more time with us than their families so we develop a deep bond. We get to know their stories and so we personally feel like doing more than what we are required to,” describes Takkhar. “We have made so many last minute visits to Liberty Market to get flowers and jewellery because the bride didn’t like the original ones,” he adds.

Photoshoot is a mini-event in itself. There are unprecedented problems that the photographer has to deal with. “We have a strong family system so we’re dealing with more than just the couple. For example, grooms often come late to the shoot because of the sehra bandhi ritual at home. By the time they reach the golden hour has passed and then we have to resort to studio lights,” says Mahwish Rizvi, owner and founder of Monochrome studio in Karachi.

From the clients’ point of view also, the money seems to come very late in their requirement. Noor ul Huda said she had no problem paying Rs 150,000 for her barat because her photographer Muaz Chugtai went above and beyond for her. “My location changed three times. Initially I wanted to do it in haveli in old Pindi and Muaz went ahead to sort the permission issue days ahead of the event. On event day permission wasn’t sorted so we decided to do F-9 park in Islamabad. I had to come from Pindi and the distance was too much. Muaz was already present at F-9 park but came all the way to the event venue in Garrison hall in Rawalpindi because we both knew there was no way I could make it on time,” recalls Huda.

Similarly, Haider Umar and Maryam Haider who got married in October 2022 made last minute changes because of bad

customer

We meet our clients at least two times before the photoshoot so they get comfortable with us. On event days they spend more time with us than their families so we develop a deep bond

Rizwan Takkhar, photographerPhoto by Rizwan and Palwasha

experience. “Initially we had decided to go ahead with the same photographer for our nikkah as well as the wedding events. But the photographer took very flashy and posed photographs of us on nikkah. A mobile camera could have done a better job. We had limited options in Quetta but we still desperately looked for other options. Although our wedding photographer charged us almost double what our nikkah photographer was supposed to charge, the experience went well so we didn’t care about the money,” recalls Haider, who paid Rs 45,000 per day for their wedding.

Although lucrative, the wedding pho tography market is becoming highly saturated. The previous generation of traditional studio photographers are still in the business but what sets the new age photographers apart is their niche aesthetic and style

“Money doesn’t last you in the business, your passion, vision and creativity does,” says Rizvi, who has been in the business for more than 10 years now. She says that she constantly has to be innovative with her aesthetic because the market is based on Instagram which is very

volatile to change. “We were doing instagram reels type videos before they were even a thing. Now we are working on another style which no one else is doing in the market,” she says. Rizvi is extremely selective with her clients because she goes to each shoot herself with her team. It’s about giving your clients something which others cannot.

Having a unique style is really important and showing that on instagram is even more. Zubair recalls the time she bagged her major client, Bakhtawar Bhutto, who liked Zubair’s instagram feed and reached out for her engagement shoot.

More than creating a unique style, it’s

also important to ride the wave at the right time. A lot of style inspiration comes from international photographers and even Bollywood. “When Anushka Sharma and Virat Kohli’s wedding video came out, everyone here wanted to have the same vibe. Brides wanted to have a similar entrance of coming alone or with just their parents, rather than coming with a whole group of girls. Similarly, Alia Bhatt’s style is very popular these days,” says Minhas, giggling away with Takkhar while discussing wedding trends.

Similarly, Huda mentioned that she started her research a year ahead. “I ordered my lehnga and decided on my photographer a year before the wedding. Everything had to go hand in hand for the Sabyasachi style vintage wedding I wanted. My photographer (Chugtai) had the traditional aesthetic that I was looking for and he delivered perfectly on my big day too,” says Huda who had each and every moment for the photoshoot preplanned. “I could not afford to have a designer lehenga of my choice, so the photoshoot was something I did not compromise on to create the full vibe of my dreams,” she adds.

As the wedding season of the year approaches again, all eyes are on everything festive, especially the photographers. With the growing internet and smartphone penetration, the idea of projecting life online is also becoming bigger. Although photography is quite an old profession, in today’s instagram-savvy world, the photography business has reached newer heights, and many niches. The flourishing wedding business has proved two things - Pakistan’s economy is ready to embrace the service sector and the younger lot can gain financial independence earlier than their parents did.

But all is not glitter and gold, it’s also sweat and blood, as many desi weddings actually are. While we know that weddings won’t ever end in Pakistan, we also know how the free market works. To stay relevant, the wedding photography business must innovate and create, because the other option is just one instagram DM away.n

Money doesn’t last you in the business, your passion, vision and creativity does

Mahwish Rizvi, visual artist/ photographer at Monochrome StudioPhoto by Monochorome Studios