Assessing the Likely Impact of Competition Policy Actions

Comments by John Kwoka Professor of Economics, Northeastern University, Boston

OECD Competition Committee

Paris 16 June 2025

Comments by John Kwoka Professor of Economics, Northeastern University, Boston

OECD Competition Committee

Paris 16 June 2025

• There is widespread agreement about the importance of ex ante assessments of competition policy actions

• These are useful in evaluating agency effectiveness, often by an external authority

• Also useful to agency itself for improving internal resource allocation

• There is also widespread agreement that the basic method for anticipating such effects is careful assessment of past experience and past effects

• Theory tends to be too sensitive to assumptions for useful results

• Only rarely is there a past experience that is exactly on point

• Typically therefore, agencies rely on a collection of past experiences that capture broad tendencies of relevant experience

• Use of broad tendencies is crucial for efficient assessments, but these must be compiled and synthesized carefully in order to produce statistically reliable estimates for policy applications

• There are different methods and different amounts of evidence for each type of antitrust offense

• For cartels, there is vast amount of data from past experiences

• For abuse of dominance, little systematic evidence

• Evidence regarding mergers lies in between

• My focus will be on mergers

• 2014 OECD guidance : 3% price effect for 2 years

• This is widely used, but with considerable country variation

• US and Mexico assume 1%, while EU, Hungary, Turkey assume 5%

• Several countries use ranges, often between 1% and 6%

• I will review best current economic evidence of price effects of relevant mergers

• My review supports a predicted price effect greater than 3%

• Merger studies as well as studies of cartels and abuse of dominance all face similar methodological issues to ensure statistical reliability

• Adequate number of observations

• Observations that do not suffer from selection/bias/distortion

• Good controls for other possible influences

• Sufficiently similar experiences: industries, products, time frame, etc.

• Should not examine only what is measurable, but also longer-term effects, non-price issues, etc.

• Despite these cautions, much of the literature on mergers examines relatively shorter term price effects, and this is what we know the most about

• I will review two very important methodological advances in impact assessment of mergers

• Merger retrospectives

• Meta-analyses

• Merger retrospectives are designed to control for other possible influences on observed price changes

• This can be accomplished in several ways, up to and including complex case-specific modeling and structural estimation

• Short-cut method for doing this is “difference-in differences”

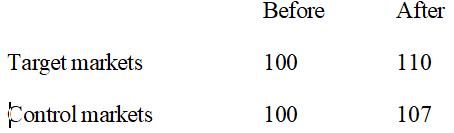

• Difference in differences measures the overall price increase in merger markets, then subtracts out effects of other causes based on price changes in otherwise similar non-merger markets

Merger retrospectives in practice

• First merger retrospective was conducted by FTC in 1980s

• These have become common techniques over past 25 years

• They have been important in many policy applications

• For example, FTC conducted retrospectives of several consummated hospital mergers in 1990s after losing court challenges

• Retrospectives showed these mergers to be anticompetitive, leading to revised and successful court strategy for challenging such mergers

• But merger retrospectives do have limitations as well

• Generally evaluate one merger at a time, so there is selection issue

• Tend to focus on one or two measurable effects, especially price

• More common in industries where data is more readily available

• Not necessarily randomly selected cases

• Until recently, not synthesized into generalized result

• To synthesize the collective implications of merger retrospectives, metaanalyses are now being employed

• Meta-analyses compile and synthesize results of all or many retrospectives

• Criteria for including studies involve data quality, adequacy of controls for other causes, publication, etc.

• It remains necessary to reconcile differences in time periods, levels of aggregation, format, metrics, etc.

• But in principle, meta-analyses offer insights across all studies

• Produce results that are more general than any one or a few specific retrospectives, not subject to idiosyncratic results

• They do have some limitations such as focus on specific industries, measurable effects, etc.

• Meta-analyses are the major innovation of past 10 years

• My initial meta-analysis in 2015 appears still to be as large and robust as any

• That study compiled all published retrospectives of U.S. mergers

• 60 published studies covered 42 distinct mergers and 119 products in almost 20 industries

• All were put into common format in order to obtain general results

• Key analysis reported that post-merger prices rose by average of 7.2%

• Prices rose in substantial majority of cases (about 80%)

• These results are after controlling for other possible causes

• Companion meta-analysis of retrospectives on groups of mergers collectively showed average price increase of 5.4%

• These covered hundreds of mergers across numerous industries, not just those that were most “policy-relevant”

• These results have been broadly confirmed by other studies reported in Background Note

• Olsen et al report effects on large number of mergers between 5% and 7%

• Ashenfelter-Weinberg study of 5 mergers finds 3-7% price rise

• Mariuzzo et al find only modest increases overall in EU, but large increases for mergers in concentrated industries

• Two studies of consumer/package goods show smaller effects, but these are all mergers, not just policy-relevant ones

• Overall, best evidence is that price effects of “policy-relevant mergers” average between 3% and 7%, centered around 5%

• This comes from hundreds of studies, thousands of mergers, conducted by numerous researchers, all controlling for other possible causes

• This average effect is first important result

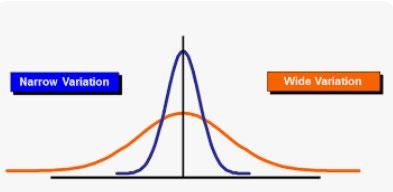

• However, policy application must be careful since any single average value can arise in different ways

• If most observations tightly bunched at average, then the average value is good summary statistic and can be applied generally

• But if data are widely distributed, so many observations are significantly larger or small than the average, then use of average will make mistakes, possibly in both directions and some potentially costly

• My study found substantial variation

• Estimates of price increases range between 0.7% to 29.4%

• Outcomes also include some price decreases, but only as large as 4.9%

• Similarly wide range of effects are reported in Mariuzzo et al, with minimal average value but effects in 10-20% range for concentrated markets

• This variation is the second important result

• It does not imply that results are of no use, only that they require careful use to minimize effects of possible errors

• Several possible strategies for careful policy application

(1) Median of data may be better than mean since it captures “typical” case

• My study found average price increase of 7.2% but median was 5.9%

(2) Use of lowest quartile number ensures “conservative” estimate

• “Conservative” means deliberate underestimate of the size of effects

• In my study, this was 3.5%, well below both the mean and median (3) Different metrics according to characteristics known to affect magnitude

• By industry:

• Olsen finds largest price distortion in healthcare, airlines

• My study found largest distortion in hospitals, publishing, airlines

• Thus, for such industries, policy might consider using a larger percentage effect

• By characteristics:

• Largest price effects arise in the most concentrated industries

• Effects most pronounced where entry barriers are high/moderate

• Thus, for mergers in high concentration industries, one could use larger percent, and even greater where barriers are substantial

• Best point estimate of the price effects of policy-relevant mergers is 5%

• Important reminder: considerable variation requires careful application of this estimate

• Price distortions are only one aspect of competitive effects of mergers

• There also may be adverse effects on quality

• Innovation effects, especially over time, are important

• Deterrence factor may be most important of all

• Many fewer studies of these other effects, which are more difficult to assess

• Recommendations for improving policy

• Conduct more merger retrospectives

• Greater focus on nonprice outcomes