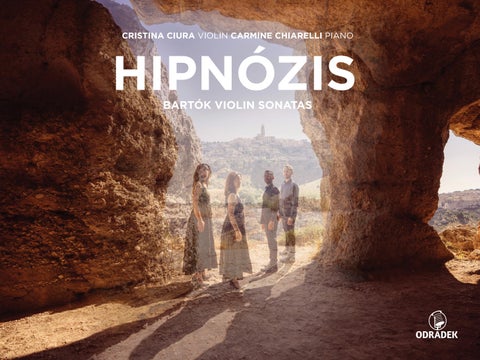

HIPNÓZIS

BARTÓK VIOLIN SONATAS

CRISTINA CIURA VIOLIN CARMINE CHIARELLI PIANO

BÉLA

BARTÓK (1881-1945)

Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1, SZ 75, BB 84 (1921)

1. I. Allegro appassionato 13'31

2. II. Adagio 11'10

3. III. Allegro 10'47

Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2, SZ 76, BB 85 (1922)

4. I. Molto moderato 08'57

5. II. Allegretto 12'06

Total Play Time: 56'34

Cristina Ciura violin

Carmine Chiarelli piano

The first time we listened to Bartók’s sonatas, especially the first one, we were struck by a bolt of lightning. What captivated us was finding a part of ourselves in the pages of these pieces: our wild side, the most instinctive part of our soul that allows us to connect with our origins.

The pages of these works are dense with notes, iridescent colours, sounds that transport us to a transcendental, psychedelic dimension, made up of strong hues and intangible sounds; rough, wild sounds, melodies with an ancestral flavour; moments of intense unease alternating with moments of stasis in which time seems to stand still.

This alternation of tension and release creates a sort of sound ritual, in which the listener is drawn into a state of hypnosis. The repetition of rhythmic cells, the use of dynamics, and the silences dense with meaning generate a flow that absorbs the consciousness, drawing the listener out of time and into a deep, almost archaic inner dimension.

Bartók’s music, despite its complexity, manages to speak directly to the subconscious. It is music that creeps in, that does not ask but demands to be listened to, that envelops and hypnotises. His writing becomes a sensory and psychic experience. The listener is no longer a spectator but part of the creative process, as if in a collective trance.

Nothing is left to chance: every indication is there for a reason, like a mapped-out path to follow. This is what captivated us and drove us to create this work.

Carmine Chiarelli and Cristina Ciura

“The beginning of the 20th century marked a milestone in the history of modern music. The excesses of Romanticism became unbearable to many, and there were composers who had the feeling that the road would lead to something unconscionable, unless we broke with the 19th century. An invaluable help in favour of change, of rejuvenation, came from a certain type of peasant music that until then no one had known.”

At first glance, one could conclude that the author of these lines speaks either from an exaggeratedly nationalistic position or simply does not know what he is talking about. How could “a certain type of peasant music” offer modern music “an invaluable aid”, when already in Mozart’s time and, of course, in Beethoven’s the dissociation between popular music and cultured music was a fact as obvious as it was inevitable? The innumerable cases in which melodies or other popular elements were used to give the music a patriotic air or to embellish it with picturesque effects do not count in this sense. Think, for example, of the effect produced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by the rediscovery of popular music; think of Bizet’s famous Carmen or the later influence of jazz on Ravel and especially on Milhaud, etc.

Nothing could be further from Bartók’s intentions. When he said this, he was referring to a deeper matter, far from paying tribute to the rules dictated by fashion. His intention was not to season music with folkloric condiments, but to absorb and transform its essence into a genuine artistic expression. In contrast, the nationalistic works of his brilliant precursor Franz Liszt, who barely spoke Hungarian, are no more than a cliché. Liszt’s was rather a temperamental affair, a consequence of his noble and fiery spirit, but in no case the fruit of a meticulous study carried out over decades. Bartók, on the other hand, devoted a good part of his life to collecting and classifying folk songs and dances. Together with Kodály, with whom he shared his double vocation as composer and musicologist, he put together an extensive collection of songs that helped him to enter the Budapest Academy of Sciences. Moreover, these studies opened his eyes and allowed him to see beyond the autocratic domains of tonality. In this way he rediscovered modal music, which had been kept alive through folk customs. This made an impression on the composer and became the cornerstone of his compositional system, especially with regard to harmony and the way of arranging the voices.

What brings together the disparity of referents in Bartókian music is rhythm and, by extension, form: “Peasant music proper shows in its forms a quite varied fullness. It is surprising that despite its emphatic force it is totally free of sentimentality and of any superfluous ornamentation. Simple, often rough, but never silly, it is the ideal starting point for a musical renaissance.” But even this second statement is not eloquent enough to convey the extent to which Bartók was aware of the dangers of using material of popular origin: “Some believe that in order to let national music flourish it is only necessary to plunge into folklore and to pour the motive material into certain forms. This opinion is also based on a conceptual misunderstanding: the significance of the themes themselves is overvalued and it is forgotten that only the art of structuring itself is able to flourish from the thematic raw material. Through a balanced combination of these parameters the true creativity of the composer is released.”

Despite his growing popularity as a performer and excellent reputation among specialists, Bartók remained largely unnoticed as a composer for the rest of his life. Theodor W. Adorno writes in 1922 that his work is little known, just in those years in which the author was at the zenith of his artistic career. His pieces were hardly played in concert halls, if at all; his name is found in the pianists’ programmes. Many of his scores are not even accessible. “That is why it is difficult to talk about him,” the philosopher stresses, “and not a few things have to be said with reserve,” although at the same time he places him among the most significant composers of his time.

Bartók’s music reached its peak in the 1920s in terms of its modernity and dissonant aspect. And precisely from this period date his only two Sonatas for violin, composed in 1921 and 1922. Both were dedicated to the Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Aranyi, who lived in London and became a naturalised Briton. She was the grandniece of the great Joseph Joachim, to whom no less than Brahms, Schumann and Dvořák, among others, had dedicated works. Not only do these sonatas clearly manifest everything mentioned above about how Bartók linked popular music with his own, but they are also fiendishly difficult, especially their solo parts. The British impresario, amateur violinist and patron of the arts Walter Wilson Cobbett called them “sonorous fortresses, impregnable to the average ear” and accessible only to one “familiar with the sounds of Hungarian folk music”.

The Sonata No. 1 consists of three movements of classical construction: fast – slow – fast. The form is only classical in its external appearance, because inside it there is a proliferation of constant fluctuations in tempo. The sonorous flow of the first movement resembles more that of a rhapsodic discourse typical of avant-garde music than that of a Classical-Romantic work. The central movement continues with constant temporal oscillations, while in the last movement those elements of Hungarian folk music that Bartók knew how to integrate into his music like no other composer explode in a dizzying way.

His Sonata No. 2 consists of only two movements, thematically related to each other. The first seems almost like an introduction to the lengthy second movement. The latter is structured around the repetition of the initial motif, but in an extremely free and bold manner: “Every vestige of bad convention has fallen away. It has become completely obvious”, comments the German Jewish philosopher once again.

Bartók found his style in the works composed at the end of the second and beginning of the third decade of the last century, a little more than 100 years ago. The integration of traditional elements with their changing rhythms, sometimes rabidly accelerated, syncopations and harmonies of seconds and sevenths beyond any coloristic flirtation with these intervals, reaches its maximum expression here, at the epicentrum of which are precisely the two violin sonatas discussed here.

Antonio Gómez Schneekloth

CRISTINA CIURA

Music has always been part of my life and my family: most of them are musicians. Seeing a violin, a cello, a piano or a harp at home was normal for me. However, I only got involved directly when I was about 10 years old, when, driven by curiosity, I decided to take up the violin under the guidance of my father Angelo, a violinist and teacher. It wasn’t love at first sight, but a love and sense of belonging that grew in me over time and became increasingly intense, to the point that during my teenage years I felt the need to sleep with my violin so as not to be separated from it.

Thanks to my stubbornness, I have always loved challenges, so I soon wanted to tackle increasingly complex pieces of music to test my abilities and overcome my limits. This is where my passion and veneration for composers such as Tchaikovsky, Wienawski and Paganini comes from.

At the age of 18, I graduated with honours from the Niccolò Piccinni Conservatory in Bari, but this was only the beginning. I then attended advanced courses with many maestros, including Felice Cusano, Ulrike Danhofer, Cristiano Rossi, Massimo Quarta and Ilya Grubert. I am grateful to each of them for giving me something important in terms of violin playing and technical training, but the person who played an irreplaceable and substantial role in my personal and musical development was undoubtedly my father, my mentor.

I have gained a wealth of experience working in orchestras, performing as a soloist and collaborating with chamber ensembles, but my fortunate encounter with the ensemble I Solisti Aquilani represented a prestigious and unparalleled opportunity for me from an artistic point of view. The artistic, musical and personal richness of all the members has taught me a great deal and further strengthened certain aspects of my being a musician.

My recent artistic experience with pianist Carmine Chiarelli embodies a renewed desire to tackle important musical pieces with ever-increasing maturity and depth.

Music has always offered me a way to channel, transform and express my torments and joys. The violin has been a faithful companion walking by my side for more than 20 years: it is reassuring to know that whatever happens, I can always open the case, pick it up and rediscover that unchanged feeling of familiarity and serenity.

CARMINE CHIARELLI

My musical journey began at the age of 14, but the piano immediately became a deep vocation, a life choice. After my early studies, I attended the Giovanni Paisiello Music Institute in Taranto, graduating with top marks, honours and a special mention, under the guidance of maestro Paolo Cuccaro.

In 2009, I began to engage with international organisations, studying at the Schola Cantorum in Paris with Maestro Aquiles Delle Vigne and at the Universität Mozarteum in Salzburg with maestro Claudius Tanski. In 2014, I obtained my second level degree with 110 cum laude at the Conservatorio Nino Rota in Monopoli, with maestro Benedetto Lupo. I also attended masterclasses with Ciccolini, Poli, Camicia, Somma and others.

I have performed in Italy and abroad, in prestigious venues such as the Wiener Saal in Salzburg, the Petruzzelli Theatre in Bari, the Ducal Palace in Martina Franca, the Coimbra Auditorium, the Giordano Theatre in Foggia and the Bishop’s College Auditorium in Colombo (Sri Lanka).

Among my most formative experiences are my orchestral collaborations: I have performed concertos by Beethoven and Schumann with the Orchestra del Conservatorio Nino Rota, the Orchestra Filarmonica Pugliese, the Orchestra della Magna Grecia and the Orchestra Sinfonica di Lecce e del Salento, with conductors such as Giovanni Minafra, Maurizio Lomartire and Piotr Jaworski. I have also collaborated with the Petruzzelli Theatre Orchestra and the Festival della Valle d’Itria (2016-2017).

In the chamber music field, I play regularly in a duo with violinist Cristina Ciura and have received awards in national and international competitions.

I continue to experience music as a human and authentic language, capable of creating deep connections and shared beauty. The stage remains the place where I can best express my artistic truth, with respect for the repertoire and the audience.

Born in 1999 in the Principality of Monaco, Slava Guerchovitch is a French pianist raised in a musical family of Soviet immigrants. After studying at the Rainier III Academy of Music in Monaco, he entered the CNSM de Paris, where he obtained his bachelor’s degree in piano with unanimous congratulations from the jury. Slava Guerchovitch is currently studying with the Russian pedagogue Réna Shereshevskaya at the École Normale Cortot in Paris. Winner of numerous international competitions (Epinal, Rome, Bellan, Scriabine, Sète, Claude Kahn...), he is regularly invited to perform in France and abroad: Festival Piano à Saint-Ursanne, La Società dei Concerti di Milano, Festival Musicorum, Artenetra, Piano en Valois, Festival de Menton, Festival Chopin à Paris, Festival Bach à Toul, Les Nuits d’Eté à Saint-Médard-enJalles, Piano à Levens, Festival Max Van der Linden... He collaborates as a soloist and in chamber music with the Monte-Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra, the Bern Symphony Orchestra, the Roma Tre Orchestra, among others. Since June 2022, Slava has been the ambassador of the Sancta Devota Humanitarian Foundation of Monaco.

“Slava Guerchovitch has not only the necessary culture and technique for a career, but also the sound and sensitivity that make him a unique artist.”

Olivier Bellamy

“From the very first notes, there is a signature sound: Slava Guerchovitch, with the significant presence of his touch, his awareness and mastery of the material he shapes, captures the attention and draws the listener into a singular poetic universe. We follow him joyfully; so much so that his approach, so full of life, enriched by a sharp perception of the musical text, served by admirable technical skills, a wide range of colours and an extreme concentration of gesture, embodies necessity and clarity. At 23, Rena Shereshevskaya’s disciple has not finished surprising us…”

Alain Cochard, rédacteur en chef de Concertclassic.com

ITA

La prima volta che abbiamo ascoltato le sonate di Bartók, in particolare la prima, abbiamo avuto una folgorazione. Ciò che ci ha catturato è stato ritrovare una parte di noi nelle pagine di questi brani: il nostro lato selvaggio, la parte più istintiva del nostro animo che ci permette di connetterci alle nostre origini.

Le pagine di queste opere sono dense di note, colori cangianti, suoni che ci trasportano in una dimensione trascendentale, psichedelica, fatta di tinte forti e suoni impalpabili; suoni ruvidi, selvaggi, melodie dal sapore ancestrale; momenti di forte inquietudine alternati a momenti di stasi nei quali il tempo sembra quasi fermarsi.

In questo alternarsi di tensione e rilascio si crea una sorta di rituale sonoro, in cui l’ascoltatore viene sospinto in uno stato di ipnosi. La ripetizione di cellule ritmiche, l’uso delle dinamiche, i silenzi densi di significato, generano un flusso che assorbe la coscienza, trascinando chi ascolta fuori dal tempo, verso una dimensione interiore, profonda, quasi arcaica.

La musica di Bartók, pur nella sua complessità, riesce a parlare direttamente al subconscio. È una musica che si insinua, che non chiede ma impone l’ascolto, che avvolge e ipnotizza. La sua scrittura diventa esperienza sensoriale e psichica. L’ascoltatore non è più spettatore, ma parte del processo creativo, come in una trance collettiva.

Nulla è lasciato al caso: ogni indicazione è lì per una ragione, come un percorso tracciato al quale affidarsi. È questo che ci ha catturato ed è ciò che ci ha spinti alla realizzazione di questo lavoro.

Carmine Chiarelli e Cristina Ciura

“L’inizio del XX secolo segnò una svolta nella storia della musica moderna. Gli eccessi del Romanticismo divennero insopportabili per molti e alcuni compositori ebbero la sensazione che quella strada avrebbe portato a qualcosa di inaccettabile, a meno che non si fosse rotto con il XIX secolo. Un aiuto inestimabile a favore del cambiamento, del rinnovamento, venne da un certo tipo di musica contadina che fino ad allora nessuno aveva conosciuto”.

A prima vista, si potrebbe concludere che l’autore di queste righe parli da una posizione esageratamente nazionalistica o semplicemente non sappia di cosa sta parlando. Come potrebbe «un certo tipo di musica contadina» offrire alla musica moderna «un aiuto inestimabile», quando già ai tempi di Mozart e, naturalmente, di Beethoven la dissociazione tra musica popolare e musica colta era un fatto tanto ovvio quanto inevitabile? Gli innumerevoli casi in cui melodie o altri elementi popolari sono stati utilizzati per conferire alla musica un’aria patriottica o per abbellirla con effetti pittoreschi non contano in questo senso. Si pensi, ad esempio, all’effetto prodotto tra la fine del XIX e l’inizio del XX secolo dalla riscoperta della musica popolare; si pensi alla famosa Carmen di Bizet o alla successiva influenza del jazz su Ravel e soprattutto su Milhaud, ecc.

Niente potrebbe essere più lontano dalle intenzioni di Bartók. Quando disse questo, si riferiva a una questione più profonda, ben lontana dal rendere omaggio alle regole dettate dalla moda. La sua intenzione non era un modo per condire la musica con spezie folcloristiche, ma per assorbirne l’essenza e trasformarla in una genuina espressione artistica. Al contrario, le opere nazionalistiche del suo brillante precursore Franz Liszt, che parlava a malapena l’ungherese, non sono altro che un cliché. Quella di Liszt era piuttosto una questione di temperamento, conseguenza del suo spirito nobile e focoso, ma in nessun caso il frutto di uno studio meticoloso condotto nel corso di decenni. Bartók, invece, dedicò buona parte della sua vita alla raccolta e alla classificazione di canti e danze popolari. Insieme a Kodály, con cui condivideva la doppia vocazione di compositore e musicologo, mise insieme una vasta collezione di canti che lo aiutò ad entrare nell’Accademia delle Scienze di Budapest. Inoltre, questi studi gli aprirono gli occhi e gli permisero di vedere oltre i domini autocratici della tonalità. In questo modo riscoprì la musica modale, che era stata mantenuta viva attraverso le usanze popolari. Ciò impressionò il compositore e divenne la pietra angolare del suo sistema compositivo, soprattutto per quanto riguarda l’armonia e il modo di condurre le voci.

Ciò che accomuna la disparità dei riferimenti nella musica di Bartók è il ritmo e, per estensione, la forma: «La musica contadina propriamente detta mostra nelle sue forme una ricchezza piuttosto variegata. È sorprendente che, nonostante la sua forza enfatica, sia totalmente priva di sentimentalismo e di qualsiasi ornamento superfluo. Semplice, spesso rozza, ma mai sciocca, è il punto di partenza ideale per una rinascita musicale». Ma anche questa seconda affermazione non è abbastanza eloquente per comprendere fino a che punto Bartók fosse consapevole dei pericoli legati all’uso di materiale di origine popolare: «Alcuni credono che per far fiorire la musica nazionale sia sufficiente immergersi nel folklore e riversare il materiale motivazionale in determinate forme. Anche questa opinione si basa su un malinteso concettuale: si sopravvaluta il significato dei temi stessi e si dimentica che solo l’arte della strutturazione è in grado di far fiorire la materia prima tematica. Attraverso una combinazione equilibrata di questi parametri si libera la vera creatività del compositore».

Nonostante la sua crescente popolarità come interprete e l’ottima reputazione tra gli specialisti, Bartók rimase in gran parte sconosciuto come compositore per il resto della sua vita. Theodor W. Adorno scrive nel 1922 che la sua opera è poco conosciuta, proprio in quegli anni in cui l’autore era all’apice della sua carriera artistica. I suoi brani erano raramente eseguiti nelle sale da concerto e il suo nome non compariva nei programmi dei pianisti. Molte delle sue partiture non sono nemmeno accessibili. «Ecco perché è difficile parlare di lui», sottolinea il filosofo, «e non poche cose devono essere dette con riserva», anche se allo stesso tempo lo colloca tra i compositori più significativi del suo tempo.

La musica di Bartók raggiunse il suo apice negli anni Venti in termini di modernità e dissonanza. E proprio a questo periodo risalgono le sue uniche due Sonate per violino, composte nel 1921 e nel 1922. Entrambe furono dedicate alla violinista ungherese Jelly d’Aranyi, che viveva a Londra e divenne cittadina britannica naturalizzata. Era la pronipote del grande Joseph Joachim, al quale non meno che Brahms, Schumann e Dvořák, tra gli altri, avevano dedicato delle opere. Queste sonate non solo manifestano chiaramente tutto ciò che è stato detto sopra su come Bartók collegasse la musica popolare alla propria, ma sono anche diabolicamente difficili, specialmente le parti solistiche. L’impresario britannico, violinista dilettante e mecenate delle arti Walter Wilson Cobbett le definì «fortezze sonore, inespugnabili per l’orecchio medio» e accessibili solo a chi «ha familiarità con i suoni della musica popolare ungherese».

La Sonata n. 1 è composta da tre movimenti di struttura classica: veloce – lento – veloce. La forma è classica solo nell’aspetto esteriore, perché al suo interno si assiste a una proliferazione di continue fluttuazioni di tempo. Il flusso sonoro del primo movimento ricorda più quello di un discorso rapsodico tipico della musica d’avanguardia che quello di un’opera classico-romantica. Il movimento centrale prosegue con continue oscillazioni temporali, mentre nell’ultimo movimento esplodono in modo vertiginoso quegli elementi della musica popolare ungherese che Bartók ha saputo integrare nella sua musica come nessun altro compositore.

La sua Sonata n. 2 è composta da due soli movimenti, tematicamente correlati tra loro. Il primo sembra quasi un’introduzione al lungo secondo movimento. Quest’ultimo è strutturato attorno alla ripetizione del motivo iniziale, ma in modo estremamente libero e audace: «Ogni traccia di cattiva convenzione è scomparsa. È diventato del tutto evidente», commenta ancora una volta il filosofo ebreo tedesco.

Bartók trovò il suo stile nelle opere composte alla fine del secondo e all’inizio del terzo decennio del secolo scorso, poco più di 100 anni fa. L’integrazione di elementi tradizionali con i loro ritmi mutevoli, a volte freneticamente accelerati, le sincopi e le armonie di seconde e settime al di là di qualsiasi flirt coloristico con questi intervalli raggiunge qui la sua massima espressione, al cui epicentro si trovano proprio le due sonate per violino qui discusse.

Antonio Gómez Schneekloth

CRISTINA CIURA

La musica ha sempre fatto parte della mia vita e della mia famiglia: buona parte di essa è costituita da musicisti. Vedere un violino, un violoncello, un pianoforte, un’arpa in casa per me rappresentava la normalità. Tuttavia un approccio diretto è avvenuto solo intorno ai dieci anni quando mossa da curiosità, ho deciso di intraprendere lo studio del violino, sotto la guida del mio papà Angelo, violinista ed insegnante. Non è stato un colpo di fulmine, ma un amore e un senso di appartenenza cresciuti in me nel tempo e che mi hanno coinvolta in maniera sempre più intensa al punto che durante l’adolescenza avvertivo la necessità di dormire con il violino per non separarmene.

Grazie alla mia caparbietà ho sempre adorato le sfide perciò ben presto ho desiderato affrontare pagine di musica sempre più complesse per testare le mie capacità e per superare i miei limiti. Da qui nasce la mia passione e venerazione per autori come Čajkovskij, Wienawski e naturalmente Paganini.

A 18 anni ho conseguito il Diploma col massimo dei voti e la lode presso il Conservatorio “N. Piccinni” di Bari, ma questo ha rappresentato solo un punto di partenza; in seguito ho frequentato corsi di perfezionamento con molti Maestri tra cui Felice Cusano, Ulrike Danhofer, Cristiano Rossi, Massimo Quarta, Ilya Grubert; ringrazio ognuno di loro in quanto mi hanno donato qualcosa di importante inerente al violinismo e alla formazione tecnica ma la figura che ha ricoperto un ruolo insostituibile e sostanziale nella mia formazione personale e musicale è senza dubbio quella di mio padre, il mio mentore.

Ho collezionato molte esperienze lavorando in orchestra, esibendomi in veste solistica e collaborando con formazioni cameristiche ma il felice incontro con l’ensemble de “I Solisti Aquilani” ha rappresentato per me, dal punto di vista artistico, una prestigiosa e ineguagliabile opportunità. La ricchezza artistica, musicale e personale di tutti i componenti mi ha trasmesso molto e ha temprato ancor di più alcuni aspetti del mio essere musicista.

La recente esperienza artistica rappresentata dal sodalizio artistico con il pianista Carmine Chiarelli incarna una rinnovata volontà nell’ affrontare importanti pagine musicali con una sempre crescente maturità e profondità.

La musica mi ha sempre offerto una strada per incanalare, trasformare ed esternare i miei tormenti e le mie gioie. Il violino è un compagno fedele che cammina al mio fianco da più di vent’anni: è rassicurante sapere che qualunque cosa accada, potrò sempre aprire la custodia, imbracciarlo e ritrovare invariata quella sensazione di familiarità e serenità.

CARMINE CHIARELLI

Il mio percorso musicale è iniziato a 14 anni, ma da subito il pianoforte è diventato una vocazione profonda, una scelta di vita. Dopo i primi studi, ho frequentato l’Istituto Musicale “G. Paisiello” di Taranto, diplomandomi con il massimo dei voti, la lode e la menzione d’onore, sotto la guida del M° Paolo Cuccaro.

Dal 2009 ho iniziato a confrontarmi con contesti internazionali, studiando alla Schola Cantorum di Parigi con il M° Aquiles Delle Vigne e all’Universität Mozarteum di Salisburgo con il M° Claudius Tanski. Nel 2014 ho conseguito la laurea di secondo livello con 110 e lode presso il Conservatorio “Nino Rota” di Monopoli, con il M° Benedetto Lupo. Ho inoltre seguito corsi di perfezionamento con A. Ciccolini, T. Poli, P. Camicia, M. Somma e altri.

Mi sono esibito in Italia e all’estero, in sedi prestigiose come la Wiener Saal di Salisburgo, il Teatro Petruzzelli di Bari, il Palazzo Ducale di Martina Franca, l’Auditorium di Coimbra, il Teatro Giordano di Foggia e il Bishop’s College Auditorium di Colombo (Sri Lanka).

Tra le esperienze più formative ci sono le collaborazioni orchestrali: ho interpretato concerti di Beethoven e Schumann con l’Orchestra del Conservatorio “Nino Rota”, l’Orchestra Filarmonica Pugliese, l’Orchestra della Magna Grecia e l’Orchestra Sinfonica di Lecce e del Salento, con direttori come Giovanni Minafra, Maurizio Lomartire e Piotr Jaworski. Ho collaborato inoltre con l’Orchestra del Teatro Petruzzelli e con il Festival della Valle d’Itria (2016-2017).

In ambito cameristico, suono stabilmente in duo con la violinista Cristina Ciura e ho ricevuto riconoscimenti in concorsi nazionali e internazionali.

Continuo a vivere la musica come un linguaggio umano e autentico, capace di creare connessioni profonde e bellezza condivisa. Il palco resta il luogo dove posso esprimere al meglio la mia verità artistica, nel rispetto del repertorio e del pubblico.