COMMODORE

VICE COMMODORE

REAR COMMODORES

TREASURER

REGIONAL REAR COMMODORES

Great Britain

Ireland

Northwest Europe

Northeast USA & East Canada

Southeast USA Brazil

West Canada & Northwest USA

California, Mexico & Hawaii

Northeast Australia

Southeast Australia

New Zealand & Southwest Pacific

South Africa

ROVING REAR COMMODORES

Fi Jones

Reg Barker

Phil Heaton

Moira Bentzel

Derrick Thorrington

Charles Griffiths

Stewart Henderson

Alan Leonard

Willie Ambergen

Bruce Bachenheimer

Peter Farkas & Patty Moss

Silvio Ramos

Liza Copeland

Jonathan Ganz

Kim & Simon Forth

Scot Wheelhouse

Viki Moore

John Franklin

Steve Brown, Guy Chester, Thierry Courvoisier, Andrew Curtain, Wiebke & Ralf Gerking, Michael & Anne Hartshorn, Lars & Susanne

Hellman, Jurriaan Kloek & Camila de Conto, Stuart & Anne Letton, Brian & Helen Russell, Sarah & Phil Tadd

PAST COMMODORES

1954–1960 Humphrey Barton

1960–1968 Tim Heywood

1968–1975 Brian Stewart

1975–1982 Peter Carter-Ruck

1982–1988 John Foot

1988–1994 Mary Barton 1994–1998 Tony Vasey

SECRETARY

EDITOR

ADVERTISING WEBSITE

1998–2002 Mike Pocock 2002–2006 Alan Taylor 2006–2009 Martin Thomas 2009–2012 Bill McLaren 2012–2016 John Franklin 2016–2019 Anne Hammick 2019–2024 Simon Currin

Rachelle Turk, secretary@oceancruisingclub.org (UK) +44 20 7099 2678, (USA) +1 844 696 4480

Emily Winter, flying.fish@oceancruisingclub.org advertising@oceancruisingclub.org oceancruisingclub.org

INTRODUCTION

THE 2024 AWARDS

Chris Jones

Heather Richard

Fabian Fernandez

Larissa Clark & Duncan Copeland

Michael Sadlier

Andy & Sue Warman

Miranda Baker

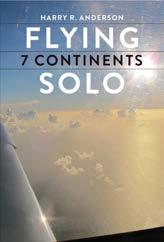

Harry Anderson

Alexander Ramseyer

Daria Blackwell

Richard Freeborn

Tom & Vicky Jackson

Cyrus Allen

Romy McIntosh

Lane Finley

Neil McCubbin

Olivia Bennett

Susanne Huber-Curphey

Brian F Russell

Ralf & Wiebke Gerking

Irene & Peter Whitby

Nicky Barker

Stephen Foot

David Southwell

Thierry Courvoisier

Marea & Rendt Gorter

Stuart Letton

Tim Riley

Vivienne Mack

Malcolm Robson

REFLECTIONS

PACIFIC CUP REGATTA

DIFFERENT HORIZONS

A JOURNEY WITH PURPOSE

A DELIVERY TRIP

GOING THE WRONG WAY

MEDICAL EMERGENCY

SOLO VOYAGE TO SEVEN CONTINENTS

WALLIS AND FUTUNA CLEW BAY

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF CAPTAIN COOK

THE EASY WAY SOUTH

MELBOURNE TO OSAKA RACE

THE REPUBLIC OF CABO VERDE

MONTENEGRO TO TUNISIA

FRENCH POLYNESIA TO BRITISH COLUMBIA

SUSTAINABLE TRAVEL

LA LONGUE ROUTE

NOTES FROM THE NORTH RAGGED ISLANDS, BAHAMAS OFF THE BEATEN TRACK IN INDONESIA

SIX CLUBS AND A CRUISE

WATER MUSIC’S LAST ACT OSTAR 2024

GAIA IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC

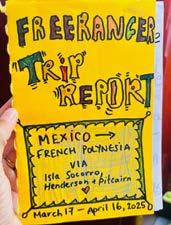

ESCAPING THE SEA OF CORTEZ SNOWBIRD RUNS THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE ACROSS THE ATLANTIC FROM THE ARCHIVES

BOOK REVIEWS

OBITUARIES & APPRECIATIONS

SENDING SUBMISSIONS TO FLYING FISH

ADVERTISERS IN FLYING FISH

The Berthon team is close knit, more of a family, backed by a strong and secure group. We are passionate about our yachts and delivering the best possible service to our clients.

With local offices around the globe, we’re here to guide you, connecting you to our amazing Berthon fleet of yachts. You’ll feel the Berthon difference – a warm, collaborative approach, where making the purchase and sale process an enjoyable one, is simply part of who we are.

€4,250,000 + VAT | Mainland Spain

2016 from the board of the legendary Nigel Irens, she comes with North 3Di sail wardrobe, full carbon build and hence she is ferociously quick. Masses of accommodation for living well and no leaning.

UK | +44 (0)1590 679222 | brokers@berthon.co.uk

US $1,195,000 + VAT | Mainland Spain

2015 splash, immaculately specified for bluewater, and massively well sorted through 3 caring ownerships. Automated rig, interior watchkeeping, she’s perfect for a couple and 4 guests to do the world aboard.

UK | +44 (0)1590 679222 | brokers@berthon.co.uk

€1,500,000 | Mainland Spain

#12 of this capable, no fuss, does what it says on the tin, bluewater cruising yacht from Team Oyster in 2009. Proper sailing rig, serious nautical makeover in 2022.

UK +44 (0)1590 679222 | SPAIN +34 639 701 234 brokers@berthon.co.uk

£1,650,000 | Palma de Mallorca

Conceived and built for family sailing and regattas in 2008. She delivered. 2022 saw her back at her build yard for new engine, Lithium Ion, improved interior layout, rig work, new North sails and stacks else.

UK | +44 (0)1590 679222 | brokers@berthon.co.uk

UK | SCANDINAVIA | SPAIN | USA brokers@berthon.co.uk | berthoninternational.com

As the files for this edition of Flying Fish are handed to the printers, I can reflect on the stories and adventures that will be revealed to fresh eyes as you navigate your way through the pages. Thank you to everyone who has torn themselves away from varnishing gunwales or servicing winches to write articles, it is a huge act of generosity for which all of us are the beneficiaries: thank you.

Readers, you have many a treat in store: from Harry Anderson’s remarkable voyage to seven continents (page 88) or honorary member Susanne HuberCurbey’s second time sailing La Longue Route (page 164), there are enviable descriptions of exploring Indonesia (page 190) and the Bahamas (page 180) as well as a reminder not to race past the Cabo Verde (page 135). Things don’t always go to plan, quick thinking and responding to adversity are an essential part of the ocean sailor’s toolkit. Stark reminders of how this can happen to anyone are shared very movingly by Miranda Baker (page 81) and Stephen Foot (page 215), among others.

But the unsung heroes of producing a publication such as this are the generous, knowledgeable, hard-working and completely charming group of proofreaders who have carefully read every word of this 320-page journal. Even in the face of tight turnarounds and several megabytes worth of text, they have carved out time to pore over each article, correcting misplaced punctuation, rearranging sentences and bringing clarity to such a variety of stories.

Jenny Taylor-Jones, daughter-in-law of Mike (whose obituary can be found on page 308), has taken over the baton of drawing the chartlets. I hope you will agree that the results are excellent and there’s not a continent that she hasn’t had to outline, such is the variety of voyages undertaken in this edition.

My final vote of thanks is to Anne Hammick, from whom I have taken the baton of editorship. The journal evolved immeasurably under her guardianship and her contribution remains woven throughout, including masterminding the book reviews (page 271). I am particularly grateful to Anne, together with Beth Bushnell, for their sensitive and assiduous efforts in sharing stories of those dearly departed members (page 289). As a Club we mourn their passing, but to learn more about their lives, lived so fully, is a real privilege.

Whether you have accrued several years of membership or are flying your burgee for the first time, we encourage you to get involved in whatever way appeals. If you are just setting sail, would you like a mentor? If you are actively cruising, how about becoming a Roving Rear Commodore, presenting a webinar or writing an article? Why not attend an event, and if there doesn’t seem to be one on your patch, we can help you organise something! Or if – as you read these pages – you lament a misplaced apostrophe or a glaring typo, perhaps you might like to help us proofread?

Fair winds!

Emily Winter, Editor

flying.fish@oceancruisingclub.org

For only the second time, the Annual Dinner took place in the US. The historic Conanicut Yacht Club, Rhode Island, provided a perfect setting to congratulate the 2024 Award winners. Sadly, not everyone was able to attend in person, those that couldn’t either nominated someone else to receive their award in lieu or supplied pre-recorded messages and will be – or have already been –presented with their awards at other locations on their cruising routes. Ted Rice, as Master of Ceremonies, ensured the momentum was maintained and the gathered crowd didn’t get too engrossed in conversation!

Bruce Bachenheimer kindly volunteered to record the occasion and photographs taken during the ceremony are reproduced courtesy of him. Club Secretary Rachelle Turk and Regional Rear Commodores Janet Garnier and Henry DiPietro, together with local volunteers, ensured the smooth running of the event.

Thanks are due to Amy Jordan, who has seamlessly stepped into the role of Chair of the Awards sub-committee. Together with her panel of judges they had the unenviable task of fielding nominations.

The history and criteria for all the awards, and information about how to submit a nomination online, can be found at oceancruisingclub.org/Awards.

The OCC Lifetime Award

The OCC Seamanship Award

The OCC Jester Award

The OCC Award (members)

The OCC Award (open to all)

The Vasey Vase

The OCC Port Officer Service Award

The OCC Events & Rallies Award

The OCC Environment Award

The OCC Water Music Trophy

The Qualifier’s Mug

The David Wallis Trophy

The Vertue Award

Victor Wejer

Pip Hare

Jacqueline Evers

Zdenka Griswold

Bill Weigel

Jesse & Sharon James and the Trinidad Operations Centre

Bob Bradfield

Tim Riley & Carol Osborne

Cristian Yanzer

Reg Barker

Ivar Smits & Floris van Hees

Carla Gregory & Alex Helbig

Fabian Fernandez

Elisabeth & Wim van Blaricum

Pam MacBrayne & Denis Moonan

In 2024, neither the OCC Barton Cup nor the Australian Trophy were awarded.

First presented in 2018 and open to both members and non-members, the OCC Lifetime Award recognises a lifetime of noteworthy ocean voyaging or significant achievements in the ocean cruising world.

In a characteristically self-effacing way, Victor Wejer has dedicated this Award to all those who have joined him in safely assisting over 100 sailboats undertaking the Northwest Passage (NWP), in particular to his dear friend Peter Semotiuk. Peter was the recipient of the OCC Award of Merit for his support of Arctic sailors in 2014.

The NWP is an under-explored region and for good reason: harsh Arctic conditions with extreme temperatures, unpredictable weather patterns and perilous navigation in its ice-strewn waters. To the amateur skipper, the NWP concentrates the mind like nowhere else because the challenges are so varied: the great distance to be travelled in a tightly defined season; the spottiness of charting; the endless coast, much without shelter; the variations in weather (usually cold and contrary); the grinding need always to be moving; and that alien interruption, pack ice. For over 20 years, Victor Wejer has been offering free and timely ice, weather and routing advice to OCC members and other cruisers transiting the NWP and facing these challenges. He has become known as the Guardian Angel of the NWP, instrumental in assisting a safe passage, looking after you day and night.

There seems to be no part of the NWP of which Victor does not have intimate knowledge, no part of the course that he cannot see better than you, even though you are in it and he is on a computer in a basement in Mississauga! There is no hour of the day he cannot be consulted and no wrinkle he has not smoothed many times before. Moreover, these intimate, knowledgeable and entirely free exchanges have been available to anyone who cares to establish contact.

In this way, Victor has done more to enable safe and timely NWP transit than any other single resource. Victor’s Yacht Routing Guide to the Northwest Passage is now in its 12th edition and can be downloaded free of charge from the Pilotage Foundation website (rccpf.org.uk/pilots/191/Periplus-to-Northwest-Passage).

Prior to 2019, according to International Maritime Organisation (IMO) code, Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) regulations dictated that boats were required to have ice class hulls plus many other things which would prevent recreational boats from sailing freely in polar waters. This prompted Victor to set up a Correspondent Group formed of experienced specialists and delegates from World Sailing, national sailing authorities, international cruising clubs and IMO member countries. Many OCC members were among the participants. As a result of this collaboration, in late 2020, the Polar Yacht Code was born.

During the pandemic of 2020–21, only one sailing boat transited the NWP, skippered by Peter Smith, the famed inventor of the Rocna anchor. Canada revoked his permit halfway through his transit, Victor stepped in and (remotely) guided him for the rest of route to Greenland.

With help from Ted Laurentius (Port Officer for St John’s, Newfoundland), they found him a good maritime lawyer to escape punishment.

Last year, Victor embraced new technologies and, in addition to his regular advice and monitoring service, he hooked up for live group video conferences with OCC boats as they traversed the NWP. Several non-OCC boats chose to join the Club as a result. His videocasts are all archived on the OCC website (oceancruisingclub.org/webinars) and demonstrate how much Victor’s support is appreciated by those hardy souls venturing to the loneliest cruising ground on earth.

In 2024, Randall Reeves completed another NWP transit supported, of course, by Victor. As a token of his thanks, Randall commissioned some local Inuit youngsters of Red Fish Art Studio in Cambridge Bay (redfishartsociety. com) to make a trophy from a piece of thin steel sheet, painted with a dedication. The Red Fish has clocked up an impressive mileage of its own. Having travelled from San Francisco, it got snared in the Canadian Postal strike, returning to California before being re-sent from Newfoundland when Randall returned to Moli.

Not only does Victor have a talent for helping people with their safe transit of the NWP, he also has an elegant way with words in his humble acceptance of this well-deserved award:

“Canada’s High Arctic is a destination filled with beauty, wilderness and seclusion; a place to reconnect with nature and with your own soul. It’s the perfect antidote to life in the current fast lane. A journey through Canada’s High Arctic takes you through a world like no other. While many Arctic adventures leave you breathless, there’s something about sailing this largely untraveled Arctic frontier that leaves you speechless, too. This unexpected Award has left me almost speechless, relying on the lyrics of Stan Rogers’s “Northwest Passage” for these words:

Ah, for just one time I would take the Northwest Passage

To find the hand of Franklin reaching for the Beaufort Sea;

Tracing one warm line through a land so wild and savage

And make a Northwest Passage to the sea.

Victor Wejer was unable to travel to Newport to collect his Award, but Gerd and Melissa Marggraff, with a recording of Stan Rogers’ Northwest Passage (youtube.com/ watch?v=TVY8LoM47xI) blaring out in the Conanicut Yacht Club, received the award on his behalf.

A presentation was made to him in May 2025 near his home in Toronto by OCC highlatitude sailor and his close friend, Richard Hudson, Issuma.

Donated by Past Commodore John Franklin and first presented in 2013, this award recognises feats of exceptional seamanship and/or bravery at sea. It is open to both members and non-members.

Pip Hare was one of 40 entrants in the 2024 Vendée Globe race, the ‘greatest sailing race around the world, solo, non-stop and without assistance’, racing aboard Medallia, a foiling IMOCA 60.

On Sunday 15 December 2024, at 2145utc, 800 miles south of Australia and lying 15th, Medallia was dismasted. Fortunately, Pip was uninjured and the dismasting happened in daylight, which made the immediate aftermath marginally easier. Pip’s first priority was ensuring the hull’s safety. Armed with a hacksaw and gloves, she removed most of the rig managing to save the boom, furlers and one outrigger in the process. Her swift action ensured that the hull remained intact; she then set to erecting a jury rig. After only three hours Medallia had a new mini-mast (the outrigger, set vertically with a forestay and two backstays) rigged with the trysail and was making way towards Australia. In a 35-knot southerly wind and following sea Medallia made 4 knots for the first 24 hours, the ‘slow boat to Australia’ as Pip’s blog hailed it.

Over the next 13 days, Pip made improvements to the rig, adding an extra sail and carrying out routine checks of all parts to ensure that it wouldn’t fail her again. She did all this whilst alone, in up to gale-force winds, and providing daily video messages to her followers and sponsors.

On 28 December in amazingly positive spirits, Pip made landfall in Melbourne with her sights set on shipping Medallia back to Europe and campaigning the Vendée Globe again at the next iteration.

One often reads of yachts being abandoned mid-ocean for a lesser reason than dismasting and doubtless Pip’s team and the Vendée Globe organisers could have effected a rescue for her and the yacht. But instead Pip determinedly and single-handedly raised a jury-rigged mast and sailed the 800 miles north to Melbourne, an inspiring figure of determination and seamanship to all those who follow in her wake.

Although she was unable to attend the Award ceremony in Newport, a video recording of Pip’s acceptance speech was shown at the dinner in which she thanked the OCC for recognising her with this award:

“I know that you all know what seamanship is. When any of us go to sea, we must acknowledge and recognise all of the bad eventualities that might happen to us when we cross oceans. We have to take responsibility for ourselves, for our crew, for our boat in a way that people don’t always have to on the land. When I dismasted I was 800 miles south of mainland Australia, almost halfway between Australia and Antarctica, and it never occurred to me that I would ask someone else to rescue me. Once I had cut the wreckage clear, I was not in any danger. I was not where I wanted to be and I knew it would be some task to get to the land, but all of that was within my gift. I had the necessary tools, the necessary equipment and the necessary training, and we had thought about what we would do if that happened. It wasn’t the way I wanted to finish the Vendée. It is still beyond devastating when I think of it, four years of training and preparation and then to dismast halfway round is brutal, but sharing the onward journey in my slow boat series, sharing with people how I jury-rigged the boat and how I took responsibility

for myself and got back to Australia was important to me to get over the disappointment and to show that the story didn’t just end there. I am really honoured that you have chosen to give me this award in recognition of that.

Thank you very much.”

Pip’s Facebook page with all the entries from the Vendée Globe, including the ‘Slow Boat to Australia’ posts, is at facebook.com/PipHareOceanRacing. She also has a website piphare.com.

Donated by the Jester Trust as a way to perpetuate the spirit and ideals epitomised by Blondie Hasler and Mike Richey aboard the junk-rigged Folkboat Jester, this award recognises a noteworthy single-handed voyage or series of voyages made in a vessel of 30ft (9.1m) or less overall, or a contribution to the art of single-handed ocean sailing. It was first presented in 2006 and is open to both members and non-members.

Jacqueline Evers’s love affair with sailing began aged 10, spending countless hours on the Frisian lakes in The Netherlands. At 18, she set off sailing with her friend in a Grinde on bigger lakes and the sea. She ventured further into the world of competitive sailing, working for a sailmaker, was a flotilla leader and skipper, then skippered a women’s racing team. Sailing evolved from a hobby to a passion and way of life.

As she reached her fifties, Jacqueline decided to leave the rat-race for the serenity of the oceans and to bring her lifelong dream to sail solo around the world into reality. In October 2020, she bought Loveworkx, a 27ft Grinde built in 1977, a boat she was familiar with from her youth, easy to sail solo and relatively easy to maintain and repair, especially with so few luxuries on board (no fridge, freezer, watermaker, shower or rollerfurler).

It took nearly three years for Jacqueline to raise sufficient funds, prepare Loveworkx for safe ocean sailing and acquire the necessary additional skills for her adventure. In 2021

she started solo sailing on her Grinde, in 2022 she did her first sail across the English Channel to Lowestoft, in 2023 she set sail. Her husband and son support her journey and said: “Follow your dream, we will follow you”. They visit her from time to time.

So far, Jacqueline has sailed from The Netherlands to New Zealand via Spain and Portugal, the Cape Verde Islands, a 22-day Atlantic crossing to Trinidad, Grenada, Bonaire, the San Blas Islands, Panama, a 30-day crossing to the Marquesas, the Tuamotus and the Society Islands, a 16-day passage to Tonga and, finally, a 17-day passage to New Zealand.

Her nominator cited the historical significance of this award:

“Jacqueline is continuing the formidable achievements and tradition of the Club’s female solo sailors crossing oceans in small yachts. Her boat Loveworkx, a 27ft Grinde, is not much bigger than Ann Davison’s Felicity Ann in which she was the first woman to sail single-handed across the Atlantic in 1952. Ann Davison flew back to England to be one of the Club’s founders at its first meeting in 1954 and thus it is appropriate that Jacqueline’s efforts should be recognised in connection with the Club’s Platinum jubilee.” Jacqueline’s account of sailing solo from The Netherlands is documented on YouTube @sailingloveworkx.

The Club’s oldest award, dating back to 1960, the OCC Award recognises valuable service to the OCC or to the ocean cruising community as a whole. It was decided in 2018 that the OCC Award should be split into two categories, one going to a member, normally for service to the OCC; the other, open to both members and non-members, for service to the ocean cruising community as a whole. Both (and in 2024 were) can be awarded to multiple awardees.

Previous Vice Commodore Zdenka Griswold joined as an Associate member in June 2009, qualifying for full membership two years later with a passage from the Galapagos to Marquesas with her husband Jack aboard their 42ft Valiant Cutter, Kite. They were appointed Roving Rear Commodores in 2014 and, during the course of their

Jack and Zdenka enjoying lobster, Matinicus Isle, Maine

Four OCC boats gathered in La Réunion in 2014: Fi & Chris Jones (Three Ships), Roger Block & Amy Jordan (Shango), Jack Griswold ( Kite), Jake & Jackie Adams (Hokule’a) and Zdenka

seven-year circumnavigation, proposed many new members from a variety of countries. On returning home to Maine in 2016, she and Jack were appointed joint Port Officers for Portland. They still found time for a cruise most years, covering the eastern seaboard of North America from Newfoundland to the Caribbean.

In 2017 Zdenka joined the General Committee and was elected a Rear Commodore two years later. Somewhat reluctantly, she agreed to become Chair of the Publications sub-committee, where the editors of Flying Fish and Newsletter considered her the perfect ‘boss’, never interfering but always ready with constructive advice if asked. Having co-edited the Cruising Club of America’s journal Voyages for five years this advice was based on practical experience. In 2019 she was also appointed Chair of the OCC Governance committee, which is tasked with the running of the Club including overseeing the actions of the Board/Directors. Then in 2021, at a time when many clubs were shrinking in the wake of Covid, Zdenka also took on the Membership brief. Numbers increased by 11% during her three years in post.

Zdenka invariably saw the bigger picture and, when standing for Vice Commodore in April 2024, wrote:

“The world is never still. Climate change, a pandemic, natural and man-made disasters inform blue water cruising plans worldwide. These challenges are balanced by unsurpassed opportunities to visit beautiful and often isolated places, learn from local people and cultures, and slowly and sustainably explore far and wide. The OCC works hard to provide support, guidance and inspiration, striving to do so most effectively under each unique set of circumstances.”

The description of this award, ‘recognising valuable service to the OCC’ is truly exemplified by Zdenka’s many contributions, all undertaken with diligence, wisdom and an enormous smile.

Ernie Godshalk accepted the award on Zdenka’s behalf at the Award ceremony and was able to deliver it to her the following day. It was with great sadness that just three weeks later, on 27 April 2025, it was announced that Zdenka had passed away at her home in Portland, Maine. A full obituary can be found on page 289. Zdenka

Bill Weigel and his wife Helen joined the OCC in 2015 to take part in the first Suzie Too Rally in the Western Caribbean. They continued cruising between the Caribbean and their home waters in Maine until 2018 when they sailed their Whitby 42, Alembic, across the Atlantic to participate in the OCC Azores Pursuit Rally. They enjoyed several seasons in Northern Europe returning each winter to Maine to pursue their passion for skiing. More recently, Bill and Helen have been cruising in northern New England with a different boat, Chase n Sadie, named after their first two grandchildren.

Over the past five years Bill has worked tirelessly, unremunerated, on the OCC’s digital systems. In the early days of lockdown, Bill volunteered his project management and IT skills to co-ordinate the development of our website, database and app. Since then, he has worked hard with our various committees and contractors to continuously refine and improve our digital presence and has done so in an exemplary fashion. Always the diplomat, Bill has had to juggle the demands of our members and our General Committee within the constraints of our budget and the technology. His knowledge of the technology and his ability to manage contractors has been, and continues to be, invaluable to the Club. Through his endeavours we have state of the art digital platforms.

This award, which can go to either a member or a non-member, recognises valuable service to the ocean cruising community as a whole.

In July 2024, in a magnificent show of humanity overcoming bureaucracy, Trinidad officials did everything they could to help those cruising yachts fleeing Hurricane Beryl. As the Category 5 hurricane approached Grenada, many crews wisely decided their safest option was to get out of the way and take their yachts to Trinidad. Their AIS tracks formed a solid block as they converged heading south. Not everyone had time to jump through the usual bureaucratic hoops and clear out of Grenada, but the instructions from Trinidad were loud and clear: it did not matter; “come anyway . . . even if you have pets on board,

just come and we will take care of you when you get here . . .” (Don’t try this without a hurricane!)

As nearly 200 yachts descended on Trinidad, the island prepared. Jesse James, Vice President of the Marine Services Association of Trinidad and Tobago (MSATT; previously known as YSATT), winner of quite a few tourism and yachting awards, and the mainstay of yachting information in Trinidad, was at the centre of co-ordinating the response for all the incoming yachts fleeing Beryl. This influx of yachts involved a lot of extra work for authorities. Jesse, together with his wife Sharon, set up a pop-up Operations Centre, which included all the main services such as Immigration, Customs, Port Health and the Government Vets together under one roof, to ensure all the necessary papers could be filled out as easily as possible and the necessary documents could be photocopied. This saved everyone a huge amount of hassle, especially as Jesse recruited volunteers from the local business community to assist with filling out the arrival forms. To make things even easier, the Coastguard announced that any yacht not wishing to land, could take safe shelter as the hurricane went by, and then return to whence they came without formalities. They wanted to know who and where they were, but there was no paperwork.

The yachts had to spread out to find suitable places to anchor, they stretched all the way down to Carenage. The bays they used are not normally yacht anchorages and the Coastguard, Customs and police put on extra patrols to make sure all anchorages were secure as well as providing extra security on the land side.

News of the hurricane was all over the local TV as Jesse went on two morning shows and explained what was happening and lobbied to get relief supplies to assist the islands that were devastated by Hurricane Beryl. As a result, the relief effort was tremendous. NGOs, local community groups, local businesses, individuals, the business community in Chaguaramas and church groups all responded. Cruisers even set up a GoFundMe fundraiser which helped to raise funds to assist. About 45 of the sheltering boats stayed to help ferry supplies back to the affected islands. These included four large catamarans from Trade Wind Yachts in St Vincent as well as many private yachts. Trinidad, with Jesse James the driving force, has set an exceptional new standard in dealing with yachts escaping a hurricane and in facilitating them leaving again with emergency supplies for the devastated area. Let’s hope his experience is not called upon anytime soon.

While sailing in Scotland, Bob Bradfield discovered that whilst the official charts were adequate for navigating between the main ports, they had very little detail of hazards in the beautiful out-of-the-way anchorages, channels and bays that he wanted to visit in his cruising yacht, Antares. So, Bob started to survey the bays and anchorages in western Scotland properly so that he and fellow cruisers could enjoy visiting them safely. In 2011, he published the first Antares charts which included accurate surveys and pilotage guidance for 40 anchorages. By 2016 he had produced 309 accurate large-scale charts and each year he adds around 60 more from the surveys that he completes whilst exploring the Western Isles. The 2025 batch of updated charts was released in January and includes an incredible 755 large scale charts. This is a not-for-profit retirement project for Bob and he charges an admin fee of just £20 (less if you are renewing) for the full set of large-scale charts.

Anyone who finds themselves lucky enough to be cruising the Western Isles of Scotland is likely to be asked “have you got Bob’s charts on board?” They truly are an indispensable aid for cruisers piloting this region. Looking only at the official charts you would be foolhardy to attempt many of the most beautiful anchorages. Yet the Antares charts enable safe pilotage around the rocks and other hazards and have opened up the most interesting parts of the region.

On hearing of his award, Bob wrote:

“I know that the OCC is firmly in touch with the needs of its members and, indeed, the yachting community as a whole, as was evidenced by the amazing support it provided during Covid. So this award really is a very special honour, although I have to say that I was somewhat surprised as ‘Scotland’ and ‘Oceans’ are words that don’t sit comfortably together! I have sailed in every ocean and cruised in some dramatic areas – Chilean Patagonian, the Antarctic Peninsula and Spitzbergen stand out. But crossing the Atlantic has been my only cruise of OCC qualifying length and I did find it rather tedious – checking the GPS with the sextant was the chief form of entertainment! So, in ‘settling down’ in such a fantastic cruising area as Scotland, I know from firsthand experience that it is one of the very best, worldwide, especially for those, like me, who find too much heat to be sapping of energy and who derive as much pleasure from the changing moods of the sky as from the more tangible scenery. I feel incredibly lucky to have stumbled across such a wonderful hobby, that I absolutely love and am addicted to, and that others seem to find useful. So awards of this kind, while neither needed nor sought, are the icing on a very rewarding cake.”

Donated by past Commodore Tony Vasey and his wife Jill, and first awarded in 1997, this handsome trophy recognises an unusual or exploratory voyage made by an OCC member or members.

Some might say that an east-to-west transit of the Northwest Passage (NWP) is no longer particularly unusual or exploratory, but the two-handed passage made by new OCC members Tim Riley and Carol Osborne as recounted in their article (see page 254) is more than worthy of recognition.

Always interested in water as a means of reaching remote places, Tim started out as a sea kayaker but, in a quest to go further and remain drier, this gradually evolved from the kayak, to a 20ft Swallow yacht in which he met Carol. The quest continued with an old Ovni which took them initially on a ‘delivery’ of the yacht from Essex to Milford Haven via, of course, Shetland and St Kilda, and later to North Norway.

They had been pushing the boundaries of what was feasible in smaller vessels for years before a chance arose to buy a Boreal 47 which had become available in the UK. They realised that opportunities like this did not come up often, so raided the coffers and upgraded, becoming proud owners of Lumina. She is well suited to more serious exploration, with her dry doghouse, endurance and resilience capabilities. Without wasting too much time getting to know the boat they made a shakedown voyage to Svalbard in 2023. Next on their bucket list was the NWP.

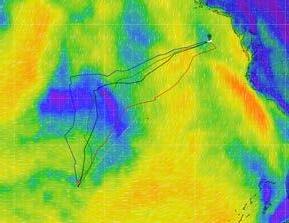

After crossing from Scotland to Greenland in May they cruised the west coast of Greenland to Upernavik before crossing Baffin Bay to Pond Inlet to begin the transit proper. It wasn’t long before they encountered serious ice.

As Tim says, “the press would let you believe that there is no ice in the Arctic these days”, but clearly this is far from true and at one stage it looked as though they might have to turn back. With commendable persistence and good seamanship, they reached Nome in mid-September, having hand-steered from

Cambridge Bay after their autopilot failed. With masterly understatement Tim remarked, “Four-hour watches are not too bad double-handed once you get used to it but when you have no autopilot they are very tiring.”

On receiving the award, Tim humbly said: “We did not set out to do anything too intrepid so are deeply honoured to stand amongst our heroes in receiving this award.”

With the yacht now in Alaska they are looking forward to a relaxing season exploring and cruising before deciding where to head onwards. When the world is your oyster it does create some dilemmas: across the Pacific, Cape Horn, Panama, Northwest Passage again – what a choice! We look forward to hearing where Tim and Carol decide is next (yachtlumina.co.uk).

Introduced in 2008, this award is made to one or more OCC Port Officers or Port Officer Representatives who have provided outstanding service to both local and visiting members, as well as to the wider sailing community.

Cristian de Lima Yanzer was appointed Port Officer Representative for Lagoa dos Patos, Brazil in February 2024. His nomination didn’t take long to be approved by the General Committee. He ticked all of the boxes! Not only is sailing Cristian’s passion, he is also an airline pilot with a keen interest in pilotage. Together with his wife Andrea, he seeks out and collates safety issues and important navigation information which he uploads on to Navionics, ensuring visitors less familiar with his home waters are as safe as possible.

Cristian and Andrea are proud to call Veleiros do Sul Yacht Club, one of the most important sailing schools in Brazil, their home club. It has a long and enviable reputation in sail training, with a disproportionate number of sailors from the club participating in the Olympics, representing Brazil (sometimes securing podium positions).

But if thousands of contributions to Navionics and assisting numerous OCC members were not sufficient to attract the attention of Awards sub-committee members, Cristian’s contribution to the response to the deadliest and most devastating floods in the history of the city of Porto Alegre in May 2024 certainly did. A full account can be read in Jurriaan Kloek’s article for the September 2024 Newsletter (oceancruisingclub.org/members/Newsletters).

Cristian was a leading force in the rescue efforts started by the local sailing clubs named Velejadores Solidários (or ‘Support by Sailors’); together they saved countless lives. Using their own dinghies and motorboats, the team ventured to remote villages sometimes retrieving people from roofs, sometimes using empty fridges as floatation devices, sometimes assisting the Brazilian navy to offload supplies when their ship could not reach shallow waters. When not on the water, Cristian and his team organised the collection and distribution of food and other essential supplies

Clockwise from top left: Cristian together with the group Velejadores Solidários (‘Support by Sailors’) taking hot meal to people’s homes during cleaning process; Helping the Navy to unload 90 tons of goods donated from other Brazilian states; Fellow sailors saving a horse near Pelotas city; Rescuing an elderly lady from her home (her daughter said she hasn’t seen her smile for years due to a stroke);

One of the kitchens working at full power helped by the organisation, All Hands and Hearts; Rescuing a baby

for people in need. During these floods, across all regions of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, at least 169 people were killed, 806 others were injured and 56 were left missing. At least 580,000 others were displaced from their homes. Flood damage occurred in 431 of the state’s 497 municipalities. At least 90 per cent of businesses suffered partial or total losses.

As the area gets back on its feet, Cristian has resumed his pilotage efforts in his sailing yacht, Viking. Her retractable keel is ideally suited for measuring even the shallowest of depths, ensuring that OCC members visiting Lagoa dos Patos in the future will be able to navigate these waters safely.

This award, open to all members, recognises any member, Port Officer or Port Officer Representative who has organised and run an exceptional rally or other event.

When then Rear Commodore Reg Barker was asked to organise the OCC’s Platinum Anniversary celebrations, the remit was loose but the focus was on one large gathering. Reg quickly realised that this had several disadvantages, the main one being that very few of the Club’s 3,000+ members would be able to attend the main function. Never one to shy away from a challenge, he instead decided on a year of gatherings, spread across the world, to aptly celebrate the global nature of the Club.

The concept was simple but Reg needed all hands on deck! He started marshalling event organisers early and set about ensuring there would be events held across the globe to coincide with the usual migratory patterns of ocean sailors. In late 2022 he wrote to all the Regional Rear Commodores and the Port Officer team asking everyone to do their best to host a party/get-together/cruise-in-company in their area at some point during the anniversary year. Many agreed with alacrity. Some required a little more prompting. But the number and spread of events promised at this stage did not fit Reg’s plan for a year’s worth of celebrations around the world so he wrote individually to numerous members to find people willing to organise and host events. Months of hard work and hundreds of emails paid off and in 2024 there were over 80 Platinum Anniversary events ranging from lunches and pot-luck suppers to mini-meets and cruises-in-company. In addition, there were innumerable informal get-togethers of crews in anchorages and harbours, brought together by the OCC burgee and the Platinum Anniversary flag. The vast majority of the ‘formal’ events were organised by OCC members or PO/ PORs but some were run by, or in conjunction with, sister clubs, e.g. the Royal

Cruising Club (RCC), Irish Cruising Club (ICC), Cruising Club of America (CCA), Seven Seas Cruising Association (SSCA), and Salty Dawgs Sailing Association (SDSA) through links forged by Reg and other members.

Reg advised each of the event organisers on how to plan, advertise and arrange the accounting for their events and kept a close eye on all the planning cycles, prompting when it was clear that things were falling behind time. In addition to the events, he organised the printing and sale of the Club’s 70th Anniversary flag (which had kindly been designed by Alex Blackwell), the photo and cocktail recipe competitions and a monthly article in the e-Bulletin and numerous ad-hoc emails to the membership to keep everyone updated.

Not only did Reg’s efforts ensure the Platinum Anniversary was suitably celebrated, he did so at a time when the Club’s usual annual events in the aftermath of Covid were in danger of dwindling. In all, during 2024 there were 46 official events, attracting some 1,500 attendees. But these headline figures do not come near to conveying the sheer amount of effort Reg put in to marshalling the milestone.

Presented for the first time in 2021, the OCC Environment Award was suggested by OCC member Jonathan Webster as a memorial to HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. It recognises cruisers who contribute towards the environment, or cruisers who raise issues pertinent to the environment especially where ocean cruising is concerned.

Ivar Smits trained as an industrial engineer and Floris van Hees as a lawyer and had busy corporate jobs and busy lives, but they became convinced that fundamental changes are needed to ensure that future generations can live in harmony on a healthy planet.

It was these insights that shaped their plan to quit their jobs, sell almost everything they owned, and leave behind their family, friends and lives in Amsterdam. They were on a mission to find solutions to sustainability challenges: solutions that work in practice and which could be shared widely and for free. And so ‘Sailors for Sustainability’ was born.

During their eight-year circumnavigation aboard Lucipara 2 they clocked up visits to 38 countries and travelled over 56,000 miles. They have published 67 sustainable solution stories, sent 61 newsletters, created 145 videos, given 25 radio interviews and numerous presentations covering climate breakdown, biodiversity loss, pollution and social inequality. A book, Overstag, about their mission to further promote sustainable lifestyle choices is their most recent addition to the mission.

The solutions they cite cover a wide range of environmental and social topics. For example, they

described how young French Polynesians are saving coral reefs, how Scotland is leading the way in tidal energy, how an island community made their island fossil-fuel free and energy independent, and how turtles are being saved in Cape Verde. By sharing these positive real-life stories, they promote lifestyle choices that respect the environment and lead to a more equitable society. But, most importantly, they spread a message of hope. In times when so many news items are negative, their sailing trip has inspired and continues to inspire individuals, communities, and companies to change their habits and accelerate positive change (sailorsforsustainability.nl).

Presented by Past Commodore John Foot, and named after his succession of yachts all called Water Music, this set of meteorological instruments set into a wooden cube was first awarded in 1986. It recognises a significant contribution to the Club in terms of providing cruising, navigation or pilotage information and is open to members only.

The Water Music Trophy recognises a significant contribution to the Club in terms of providing cruising, navigation or pilotage information. Although ‘The Marshall Islands’ by Carla Gregory and Alex Helbig (Flying Fish 2024) was written as an account of their visit to the archipelago rather than with pilotage information in mind, there’s no doubt that it will be of considerable interest and practical use to those following in their wake. Indeed, their mouthwatering photos and patent enthusiasm for the islands are certain to encourage more OCC members to visit in the future: “We had spent a fabulous 2½ months in one of the most remote areas of the Pacific, an unspoilt archipelago almost lost in time.”

Alex and Carla met in the Maldives on a small island in south Ari Atoll called Dhidhoofinolhu in 1994. At that time the resort was called Ari Beach, a ‘no news, no shoes’ island, quite different to the luxury resorts of the Maldives today. Alex was working in the watersports centre during the high season and in Cannobio in Italy during the summer months. After 10 months travelling the world they settled in the UK, building up funds and immersing themselves in the sailing world, becoming members of Speedbird Offshore Yacht Club, a British Airways club, where they both qualified as yachtmasters. Carla went on to become Commodore and then Chairman and Alex a cruising instructor. When they bought their dream boat, a Van de Stadt designed Trintella 45, in 2012 ‘Ari B’ seemed the obvious choice for a name both of the boat and their next adventure. Their journey has taken them across the Atlantic via Cape Verde, the Caribbean, Cuba, Colombia and San Blas before transiting the Panama Canal, then across the Pacific. They explored French Polynesia for most of the pandemic, then sailed to New Zealand via Fiji for a major refit. Nearly 18 months later they circled back north to Tonga via Minerva, Fiji, Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands.

Carla and Alex were unable to attend the Awards ceremony in Newport, but joined the Whangārei BBQ where Mary Schempp-Berg presented them with their award:

“We love Flying Fish, which gives us countless hours of engagement and enjoyment, so it’s doubly rewarding to receive recognition for our contribution to a publication we value so highly.

We are humbled to have been nominated for an award and most certainly never expected to win one, so we will find a prominent place aboard Ari B to display the trophy. No doubt it will be a great talking point when fellow OCC members pop over for a drink!”

Carla and Alex are currently cruising the islands of Fiji before heading back to New Zealand for the cyclone season. They write a very readable blog at sy-arib.com.

Presented by Admiral (then Commodore) Mary Barton and first awarded in 1993, the Qualifier’s Mug recognises the most ambitious or arduous qualifying voyage published by a member in print or online, or submitted to the OCC for future publication.

Fabian Fernandez is one of very few Malaysian sailors to undertake a short-handed circumnavigation in a sailboat. In his webinar for the OCC 2024/25 series (oceancruisingclub. org/webinars) he explained some of the cultural, linguistic and financial barriers that he faced. His 1,800-mile double-handed qualifying passage began in Langkawi and ended in the Maldives; one of only two members who quote Langkawi as the starting point for a qualifying passage!

As an Asian sailor, Fabian found himself in a minority group at almost every port. He contributed an article to the December 2024 Newsletter (oceancruisingclub.org/members/Newsletters), in which he summarised some of the highlights of his route, particularly the fantastic welcome he received in South Africa, where the Malaysian flag was flown in his honour. Fabian received great support from his OCC mentor in America, Fabio Mucchi.

Once his trade-wind circumnavigation is complete he hopes to prepare a new boat, Courage, for a more arduous Northwest Passage and Figure of 8 circumnavigation of the Americas. Fabian looks likely to be a regular fixture in the pages of Flying Fish and perhaps on the roll call of OCC Award recipients too. Let’s hope so!

“Sailing has changed my life, and I want to share that experience with others. I hope this award helps inspire more people to embrace the sea, take on new challenges, and discover the freedom that only sailing can offer.”

Wim and Elisabeth

Presented by the family of David Wallis, Founding Editor of Flying Fish, and first awarded in 1991, this silver salver recognises the ‘most outstanding, valuable or enjoyable contribution’ to the year’s issues. The winner is decided by vote of the Flying Fish Editorial sub-committee.

It is never an easy task to single out a single article from a journal packed with tales of intrepid cruising and sailing escapades, but Elisabeth and Wim van Blaricum’s name appeared on each of the editorial team’s ballot paper for their article ‘Bengt in Chile’. This followed on from their equally gripping ‘Bengt in the South Seas Towards Chile’ which appeared in Flying Fish 2023/2.

“This ticks all the boxes, being a thoroughly enjoyable account of cruising remote and potentially difficult waters accompanied by some excellent photos”, “Wim and Elisabeth are exactly the sort of people that I like to meet while cruising” and “An excellent account of a wellplanned and successful cruise in one of the few unspoilt areas of our crowded planet”.

Perhaps extra brownie points were earned by the Editorial sub-committee because despite Wim and Elisabeth not writing in their first language, their articles have required less red pen than many submissions to Flying Fish by native speakers.*

Elisabeth and Wim van Blaricum hail from Göteborg on the Swedish west coast. Elisabeth was raised at sea (her parents were crab and lobster fishermen),

* Although of course we truly don’t mind wielding the red pen, and would far rather hear about fellow member’s adventures, typos and all!

and sailed extensively along the Swedish coast. She purchased her own sailing boat, Betty Boop, a Triss, when she was just 17 and made no secret of telling her three children that she intended to live on a boat as soon as they left home. This dream was realised when she met Wim from Dordrecht in The Netherlands, who also has three children.

Between 1984 and 1988, Wim sailed around the world in 24ft, Anna. Meeting a Swedish girl on Tahiti meant settling in Sweden. Many years later, he met Elisabeth and in 2012 they decided to sell their respective houses and buy a cottage in the country. But Elisabeth wasn’t ready to give up her dream of living on a boat, a determination which resulted in Bengt, a steel Bruce Roberts 44 Offshore (built by Bengt Matzén in his garden in Stockholm between 1987 and 2001); they moved aboard in 2013.

Bengt left Sweden in 2016 and sailed around the Atlantic, a test for both crew and boat. After a year in the Azores they continued westward, via the Caribbean, Panama and Rapa Nui, arriving in Polynesia in 2020 which was to become their playground for three years. Since then, they have sailed to Valdivia in Chile, with overland trips to Argentina, Bolivia and Peru, before sailing back to Polynesia.

At the end of their article they mention “the long crossing to Polynesia”, and in late November 2024 emailed Flying Fish to say that they’d reached the Gambier Islands after a 33 day, 3,926 mile passage from Valdivia, downwind all the way: “a great passage under two poled-out head sails. Now we have to get used to the tropics again!” After hauling out in Raiatea during March/April, they plan to continue to Samoa, Tonga and New Zealand in October. The question is, what will they choose to write about for their article in Flying Fish 2025?

If these two articles only served to whet your appetite, they write eloquently and regularly on their blog (sailblogs.com/member/bengt), in Swedish but readily translatable.

Members who become aware of achievements that may merit recognition should check the full criteria and requirements for each award and then complete the online nomination form (oceancruisingclub.org/Awards). You will need to provide details of both yourself and your nominee, and a short rationale for the nomination: awards@oceancruisingclub.org

Marion, MA. USA to St Davids Head, Bermuda at 50 years, is the oldest offshore race designed specifically for Corinthian cruising sailors.

H ADVENTURE – A 645 NM bluewater adventure from historic Marion, Massachusetts to the turquoise waters of Bermuda managed in the most safe and supportive way.

H CRUISER FRIENDLY FOCUS – No professional crews or high tech race boats. Focused on family crews, shorthanded teams and cruising designs.

H COMMUNITY AND CAMARADERIE – You’ll meet like-minded sailors, share stories, and become part of a welcoming offshore community.

H FAIR HANDICAPPING – The race uses state of the art VPP programs to rate boats ensuring the best available handicapping system.

2027 being the 50th Anniversary of the Marion Bermuda Race will be celebrating over the next two years with special videos, promotional events and human interest stories. The 2027 race will be a not to be missed experience, one you will talking about for years to come.

For more information, visit our website at marionbermuda.com, and be sure to sign up for our race eNewsletter. Also visit our Facebook page and YouTube channel. If you have a specific question, please email race@marionbermuda.com for a prompt response.

by Spectrum Photo

by Chris Jones (s/v Pyewacket)

Husband of OCC Commodore, Chris has brought his wisdom to Flying Fish several times over the years. His articles include “Around Iceland” in Flying Fish 2018/1, “Sail Indonesia” in Flying Fish 2010/1 and “Galapagos Update” in Flying Fish 2006/1.

As my run up to four score years looms ever closer, the urge to reflect on past experiences of ocean cruising becomes as pressing as annual boat maintenance. So, with the toolbox back in the locker, here goes.

It all started back in October 1989 when I managed to get 12 days off work, as head of a residential outdoor education centre, to help deliver a Sweden Yacht 38 from Holyhead to Las Palmas in Gran Canaria. A few months previously I’d also completed the Observer Round Britain and Ireland Race, with another OCC member, in a Dufour Arpège 29. Clearly, we had a very supportive staff team at work! More to the point, why did the owner of that fine Sweden Yacht, which he planned to sail in the ARC, not want to sail the boat down to the Canaries himself? That seemed strange but for some reason, he preferred that we did it and it turned out to be an opportunity for me to participate in a 1,000-mile non-stop passage. I felt reasonably confident that with three of us on board, rather than just two on the Round Britain and Ireland Race, the passage couldn’t be more difficult . . . or could it?

The Sweden Yacht was equipped with a compass, both VHF and SSB radios, a trailing Walker log and a sextant together with the appropriate sight reduction tables. There was also an autopilot on board, but sadly it was rendered inoperative soon after we left Holyhead. A surge in electromagnetic interference when attempting to transmit via a faulty SSB radio may have been the culprit, but it could have been any number of faults. Anyway, by that time it was too late to do anything about it. The skipper was a reasonably experienced ocean sailor so, in a heady cocktail of naivety and bravado, the three of us agreed that we could hand steer all the way by adopting a ‘3 hours on / 6 hours off’ watch system – or at any rate, we’d give it a go!

The memories of that passage are still as clear as day. A smooth start, to lull us into a false sense of security, was followed by a northeasterly gale developing as we crossed Biscay. We stood our lonely three-hour watches driving through the stormy black night, concentrating only on the dim light of the compass as a large quartering sea sent spray into the cockpit at regular intervals. After 36 hours a hot southerly wind arrived, wafting with it the aromatic scent of

herbs and pine, to announce the proximity of northern Spain somewhere over the far horizon. The sky cleared and picking a star to steer by at night as the heavens rotated above was pure joy. We navigated by dead reckoning and a sun sight, when conditions allowed, and after 10 days land appeared over the horizon. We found ourselves on track but well ahead of our estimated position. We’d obviously underestimated the effect of the south-going Portugal current. Landfall was reluctantly sweet.

Over the subsequent years navigation became a little easier. Used in comfortable parallel with well-established methods of navigation, technology moved on and GPS and radar became widely adopted on many ocean-going yachts. However, chart tables were still well named and the RYA programme of theory and practical courses enabled us to match our growing experience with a welldeveloped system of ability verification.

When we bought our Gitana 43 Three Ships in the United States in 1999, Fi and I thought that sailing her non-stop from Florida back to Caernarfon in Wales with a couple of friends wouldn’t be too much of a problem. We’d only sailed her for a few hours, but we spent a couple of weeks prior to departure carrying out the necessary maintenance. We fitted a Monitor windvane and a Garmin 128 GPS, so together with the compass and an occasional sun or star sight we were able to track our progress.

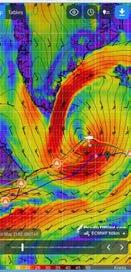

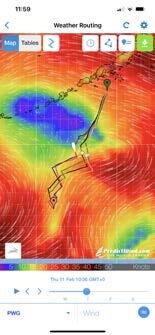

Two days out from Fort Pierce in Florida the power amp on the SSB radio failed and once more we were unable to transmit but we could still hear Herb Hilgenberg giving updates to other vessels nearer the coast. No worries, I’d been there before! Without any way of getting weather forecasts for our area, we dealt with what we were given. Little did I realise that we were about to experience first-hand two phenomena we had only hitherto understood in theory: an ocean current called the ‘Gulf Stream’ and a meteorological event known as a ‘Polar Front’. At first surprising, the appearance of tidal stream separation lines 1,000 miles from land, unpredictable back eddies and the sudden formation of fog banks associated with significant water temperature changes, indicated the edges of the Gulf Stream. We sat in the flow on the southern edge and made good progress for a couple of days until the stream spat us out into a countercurrent back eddy. That slowed things down a bit.

The next lesson was heralded by black clouds and a waterspout on the northerly horizon. “This must be the polar front,” we thought and we were not wrong. A 3D collision lay ahead between the rising air of a warm, moist, southerly air mass and a cold, dry air mass to the north. The result was 12 hours of hyper convection during which we passed through an unforgettable string of violent thunderstorms, accompanied by St Elmo’s fire and a mindnumbing lightning show. While all this was going on, the helm could only

crouch behind the wheel while the crew all tried to hide in the heads to get as far away as possible from the mast! When we finally emerged on the north side of the front, stormy conditions persisted and an on-going lightshow provided a dramatic backdrop in the southern sky for several days. This apparently was all part of the game.

Less part of the game – and totally unexpected – was running over an unlit fishing net at night 300 miles off the west coast of Ireland. The skipper of the trawler, lying at a safe distance, was sympathetic but unhelpful. Fortunately, Fi was prepared to adopt a more proactive approach. With a safety line attached, she dived over the side into the long, 3m swell, swam under the boat, braced her feet on the bottom of the hull and tugged the offending rope from around the rudder. It’s true that she does rather enjoy swimming but that dip certainly earned her a chocolate biscuit.

When we anchored off Caernarfon Bar 33 days and 4,300 miles from Fort Pearce to wait for the rising tide, we were rather surprised to find that none of us wanted to get off. We had all been completely absorbed by the peaceful routine of living at sea, 24 hours a day, working together to manage the trials and tribulations associated with an ocean crossing. We were reassured by our ability to cope.

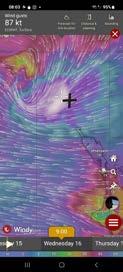

Importantly, I realised we had gained a valuable insight into the power, unpredictability and behaviour of an intense weather system. At the time, the learning was off the scale but it was invaluable during subsequent ocean passages. Predicting the actual way that phenomena such as the ITCZ (Intertropical Convergence Zone), frontal boundaries, cut-off lows, short-wave troughs and coastal katabatic thunderstorms may develop lies beyond the capacity of broadbrush shore-based advice from a weather routing service. At the end of the day, we realised that when we were on passage, it was up to us to adopt a strategy based on what we saw ahead, based on our understanding of how and why a weather system might behave. A ready supply of good fortune was, of course, always a bonus.

By 2002, we’d been operating Three Ships as a commercial sea school for a couple of years and we decided to enrol on the ARC, thinking it would be an interesting event for our crew of four previous customers, one of whom was a 72-year-old Master Mariner whose bucket list included crossing the Atlantic under sail. As we prepared for the passage in Las Palmas, we were berthed next to a couple with a brand new Beneteau 40. The wife looked distinctly nervous. When I enquired as to whether she felt able to cope if the skipper fell overboard, he immediately appeared in the companionway and announced

Taking a sight

that, unlike ours, his vessel had a sugar scoop stern and autopilot, and that if he fell overboard his wife could easily start the engine and back the boat up – and that was the end of the conversation. I’m glad to say that they did arrive safely in St Lucia but his approach was very different from ours and as far as we know they never sailed the boat out of Rodney Bay after that crossing.

By way of contrast, our crew had been very specific about how they wanted to experience the passage. This involved a watch system with hand steering all the way, on-deck sail management and using traditional methods of navigation, none of which posed a problem with six of us on board. The navigation was aided hugely by having a Master Mariner who was willing to lead three of us taking our daily ‘sun-run-sun’ sights, a delight from which we all derived great satisfaction. And no one went overboard, accidentally or otherwise!

On reflection it seems that commercial events such as the ARC are open to anyone with the motivation and wherewithal to apply. Crews are supported by some initial guidance and safety stipulations, though the effectiveness of this preparation and backup will always be up for debate and will depend on to whom you talk. On our passage, the crews of the vast ARC fleet were instructed to keep in touch via small SSB radio nets. Each net had an appointed net controller who was supposed to report the position of their vessels to ‘shore control’ each day via sat phone. Once we were all at sea it soon became evident that sitting below on the radio on a regular schedule, regardless of sea conditions, was not what several of the volunteer net controllers had bargained for. Some role renegotiation soon followed. Exactly what ‘shore control’ would have done with the position information had an incident occurred remained unclear and in fact several serious problems did occur during the passage. These sadly included a death on one vessel and a broken rudder on another, the latter resulting in the boat being abandoned. Fortunately, all the incidents were managed adequately within the fleet via the radio nets and with the support of a participating sail training vessel.

It was sometime later, having crossed the south Pacific Ocean, that I remembered why I was first attracted to the OCC by this ethos to co-operatively problem solve: a disparate fleet of ocean cruisers coming together in a shared appreciation of the freedom of being on the open ocean.

The reality is that humans have been crossing oceans for millennia in all manner of craft and for all sorts of reasons, but the ocean is still the ocean. Recently, a neighbour of ours had heard that we had done some long-distance sailing and, in general conversation, enquired as to whether any of it was dangerous and whether we stopped each night to go to bed. My reply ‘all of it is potentially dangerous’ and ‘we sail 24/7’, seemed to surprise him. This response illustrates an issue often mentioned by crews when recounting their experience to friends after returning from a first ocean passage. How can we expect anyone to understand the distance, isolation and demands associated with crossing one of the greatest wildernesses on the planet unless they too have been there? For newcomers, some serious research and very well-considered preparations may be the only solution.

So perhaps it’s worth reflecting on how the way that folk used to go ocean cruising fits with a contemporary approach to the activity. As we know, oceangoing yachts didn’t always have an engine, usually employed hand steering or a windvane and mariners navigated by a combination of dead reckoning and astro navigation. Communication was managed via VHF and SSB radios. For some purists this still defines one end of a continuum, the other end of which might be a yacht with a powerful engine, driven by a powered autopilot, equipped with a rig where all lines lead back to the cockpit and fitted with a 24/7 internetaccessible comms suite (e.g. Starlink). Nowadays, strategic decisions relating to the likely weather conditions on passage seem to be delegated to a distant on shore ‘weather router’. However, this can have certain limitations at times of greatest need. We even heard one ‘weather router’ direct a sponsoring vessel into an area of more favourable winds where a significant counter-current reduced their expected 24-hour run of 130 miles to just 80 miles. Not ideal.

Nowadays, with course plotting, radar, depth and AIS all displayed simultaneously on one screen – assuming the power supply is maintained –one person can, in theory, be on watch below decks monitoring a screen while all the other crew members play on social media or sleep. Who knows if this approach will become common practice or remain a rarity, but the prevalence of widespread screen obsession in everyday life is undeniable and the impact of such preoccupation among crews on passage is yet to be documented. The ultimate decision on determining the style of an ocean passage and where it sits on this historic, and constantly evolving, continuum is intensely personal and remains the responsibility of whomever takes on the role of skipper for the passage.

Unsurprisingly, looking back on our 96,800-mile leisurely circumnavigation, it was how we equipped the boat that had the greatest impact in time of greatest challenge. The Monitor windvane drove the boat for days on end and we didn’t end up fitting an electric autopilot until we arrived in New Zealand some six years and 25,000 miles down the track. (Even then it was only because our time in New Zealand was to be spent coastal cruising, as we circumnavigated South Island and beyond, rather than undertaking offshore passages.) Watching the Monitor handle a variety of wind directions and conditions, while the boat sailed in complete harmony with the ocean, was a delight and it seems strange that such equipment is apparently less popular among ocean cruisers today.

Our next favourites were a forward scanning echo sounder and foldable composite mast steps. This combination made navigating in poorly charted shallow coastal waters very straightforward. One person standing on the first set of spreaders spotting colour changes in the water while the helm kept a close eye on the seabed profile via the EchoPilot in the cockpit was all we needed, even when negotiating the narrow, potentially hazardous, entrance passages around the Tuamotu atolls. We also adopted similar tactics when looking for leads through 30% ice off the east coast of Greenland, though on that occasion the crew on the spreaders needed rather different dress! It’s true that it may be possible to obtain similar information today via Google Maps or equivalent –but is that really what an adventure is all about?

Radar is great for spotting and tracking squall development and, together with the forward scanning EchoPilot, facilitated passages through poorly charted waters in many of the south Pacific Island groups. At the other extreme, in thick fog the radar accurately identified the break in the high ground signifying

the entrance to Prinz Kristiansund in southern Greenland. Fortunately, we also received a VHF report from an ice reconnaissance aircraft telling us that visibility was perfect once we got a mile out from the entrance. All this time, communications within the maritime community still worked well, depending on propagation, via SSB radio nets. The ability to talk to a dozen or more vessels, some 800 miles ahead and others a similar distance astern, was comforting, informative and an interesting challenge. Things have clearly moved on, but it would be interesting to know if the fishermen in the fiords of South Island, New Zealand, when running out of toothpaste or needing to arrange a crew change, have abandoned Mary’s ‘Bluff Fisherman’s’ SSB radio net in favour of setting up a WhatsApp group – I guess anything is possible. In any event, a simple, flexible approach to using the most appropriate equipment on board for the job in hand has always worked well for us and hopefully will continue to do so for others.

What motivates crews to venture out into this oceanic wilderness is eternally open ended and as old as the hills. Today this might vary from the traditional ‘because it’s there’ to buying a spot on a commercial round-the-world rally and regarding it as a ‘potentially bloggable tick on social media’. However, regardless of the motivation, it still comes down to the skipper to ensure that the vessel and everyone on board is adequately prepared for the passage, whatever that may entail.

When we had crew who were new to long-distance cruising, the rapid shift of an overstimulated screen-driven brain into the simplicity of life on a threeweek ocean passage was sometimes seen as boredom. However, we found that

the calming impact of concentrating for a while, taking turns hand-steering the boat for two or three hours in rotation for a couple of days and nights, led to a reassuring sense of confidence, if only in the knowledge that should the autopilot fail the crew knew that we could continue to keep the boat running in the right direction. And we shouldn’t underestimate the value, for any of us, of feeling the boat’s motion through the pressure on the wheel or weight on the tiller, of having the time to experience the revolving night sky, of seeing shooting stars or a fragmenting meteorite fall to earth in a shower of bright green sparks and, maybe, of smelling the breath of a whale as it surfaces alongside.

Of course, things can – and do – go wrong and this is where we found identifying a workable ‘Plan B’ came in (commonly known as problem solving before the problem arises). In conversation with other cruisers we heard of many varied problems, and the following examples relate only to navigation and vessel handling issues, rather than to catastrophic disaster: the motherboard failed on an integrated navigation system; chart details on a plotter disappeared after crossing the international date line; and nearby lightning strikes took out all the instruments. Total or partial electrical failure was often resolved by applying the mantra ‘connection, connection, connection’; and engine failure, the loss of battery power after a controllable ingress of water, and rigging and sail damage all occurred for any number of reasons. The phasing out of paper charts between 2025 and 2030 will make dealing with instances relating to the loss of navigation instruments that much more difficult and how navigation training will be adapted to accommodate the move to ‘Electronics First’ remains to be seen. Similarly, the training programme for the RYA Yachtmaster® Ocean qualification – with its emphasis on manual astronavigation – will also need significant revision to fit the ‘Electronics First’ mould. Interestingly, for me, the more often we were faced with problemsolving challenges, the more I came to rely on an intuitive response rather than succumbing to an avalanche of mind-numbing potential options. On one occasion we had an engine problem which had me completely baffled. I could not figure out how to solve it, so I finished my watch and went to bed. Two hours later at 0400, I woke up with the solution, squeezed down into the engine compartment and fixed it. The brain is a wonderful tool given the time and space to work without distraction, although that too may fall into disrepair by constantly resorting to AI models such as Chat-GPT to solve our problems.

Thankfully, most ocean passages are completed without incident and, for us, remain one of the precious jewels in the crown of our sailing experience. At best they have been rounded off with spontaneously arranged social gatherings with other like-minded cruisers and have provided us with some of the most memorable moments and enduring friendships in our cruising life. This perhaps underpins why, when making landfall, we may have felt that moment bittersweet – the satisfaction of a challenge completed and the sadness associated with a journey that has come to an end.

I think that the following two quotes sum up my views on long-distance cruising: “It is always better to travel in harmony with our surroundings in the company of like-minded friends, than to arrive” – and – “True success is measured only by our effort and participation when faced with uncertainty and challenge”. We are all captains of our fate, and we can but sail on the winds we are given.

Bon Voyage! And never run out of chocolate biscuits.

by Heather Richard (s/v Carodon)

Heather wrote to Flying Fish shortly after the 2024 deadline had passed, we are pleased to report that over a year after finishing the race, Julius is now fully immersed in his oceanography studies – and they are both still sailing: finedayforsailing.com.

My three kids and I had long dreamed of racing in the Pacific Cup Regatta from San Francisco to Hawaii aboard Carodon, our 43ft aluminium sloop. Carodon is a 50-year-old one-of-a-kind cruiser, loosely based on a classic Sparkman & Stephens design. The race was cancelled in 2020 due to the Covid pandemic and our life and livelihood were upended for a few years. By the spring of 2023 I had started thinking about the race again. My middle son, Julius, was on track to graduate high school in June 2024 and start university as an oceanography major shortly thereafter. Oceanography is natural to him having grown up entirely living on boats in the idyllic little waterfront town of Sausalito, California, with an ecosystem rich in aquatic life. He already owned his own sailboat, a Pacific Seacraft Flicka 20, worked as a sailing instructor, was cocaptain of his high school sailing team, had been an open water diver since the age of twelve, was an avid fisherman and had sailed the Pacific coast from Port Townsend, Washington to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. In fact, he had never actually lived on land.

It seemed a fitting high school graduation present to a budding oceanographer to give him the gift of crossing an ocean – even if it proved a stretch for me to take that much time off work, not to mention the expense. The original crew we had lined up for the 2020 race (including his two siblings), now had summer commitments, so the two of us decided to doublehand the 2024 race. I selfishly thought that if I knew he could turn and turn-about with me across the Pacific I would not worry about him as much in the future when he might decide to sail his own boat offshore. It was potentially also the last quality time sailing together – he might want to do his own thing after college! And, the race could serve as our qualifying voyage for OCC membership because, although we had both clocked up many thousands of sea miles, neither of us had done a non-stop ocean passage that far offshore. Carodon and Captain ‘Mom’ with passengers

It was a good thing that I started musing about the race early in 2023 because the prep took a full year to accomplish. The rules, equipment requirements and inspection checklists specific to this race have been developed over many years in response to the unique challenges of crossing the Pacific in mid-summer. There is potential for intense fog and heavy traffic just offshore along the northern coast of California, a chance of typhoons rolling off Mexico, a notorious squall alley for a large portion of the course and no medical services once you get past the US Coast Guard’s helicopter range. All create serious challenges, with lessons learned from mishaps in past races dictating the long list of requirements to enter now. I had 276 items on the list and approximately US$10,000 to spend before we were allowed over the starting line, and that was for a boat that was already well-equipped and outfitted to US Coast Guard chartering standards! Carodon is also our family home (for myself and three kids), so there were a lot of things to remove for the race. Plus, we had to take the required safety-atsea courses, beef up on our offshore first aid skills, and get health checks and prescriptions for just-in-case medication. On top of all that, I had to plan for crewing and outfitting the boat for the delivery home without my son, who would be flying back in time for his first day at university.