EARLY YEARS

My flying career nearly came to an early and spectacular ending. Shortly after my first solo in a Tiger Moth, aged 17 and a few days, my instructor (a veteran of the Royal Flying Corps) decided to introduce me to aerobatics. After some loops and barrel rolls he inverted the aircraft to demonstrate the effect of negative G in straight and level flight. As my weight was taken up by the seat harness I felt something rip and realised that the buckle had sheared from the lap strap. This left me hanging on to the cockpit coaming with my hands and with my feet wedged under the instrument panel.

The instructor interpreted my yells down the Gosport tube, the means of communication between the front and back cockpit where I was positioned, as cries of sheer delight. When the aircraft was turned the right way up I was able to explain my discomfort which reflected the lack of a parachute and our close proximity to the mud in Langstone Harbour. We returned to Portsmouth Airport, now an industrial estate, landed and the instructor inspected my harness. “Not a word to anyone sonny,” he said. Happily, this early scrape did not dim my ambition to join the Royal Air Force.

My mother, sometimes prone to exaggeration, claimed this aspiration stemmed from observation of the Battle of Britain from Dene Park just south of Horsham where I was born. Only one year old at the time of that great battle, such precociousness can be safely denied. However, four years later now living in Walmer just south of Deal in Kent I can vividly remember Doodlebugs (V-1 flying bombs) overflying towards London, some of which were shot down or crashed nearby with a deafening explosion. My mother and I sheltered under the kitchen table as there was no bomb shelter in the garden. I retain a vivid impression of ships burning in the Channel and recall the sky darkened by a vast armada of aircraft, far too many to count. In later years I learnt that these aircraft and gliders were on their way to Arnhem as the first airborne assault of Operation Market Garden. And in Deal I first encountered Americans cruising around in their DUKWs, an amphibious assault vehicle, presumably as part of the D-Day deception plan. A friendly wave was often rewarded with a shower of ‘candy’.

When I was born in July 1939 my father was at sea as captain, Royal Marines, on board HMS Cumberland, a County-class heavy cruiser. He endured a long and arduous commission which included service in the South Atlantic, the Mediterranean and on Arctic convoys including the disastrous PQ17 which suffered the most grievous losses – 24 out of 35 merchant ships were sunk after the Admiralty ordered the convoy to scatter. The quality of father’s service was recognised by the award of the MBE (Military Division). On returning to England in autumn 1943 he was posted to the Royal Marines Barracks at Deal where my sister was to be born and where we lived together as a family for the first time. But not for long, as in late 1944 father was posted as second-in-command of a Royal Marines infantry battalion serving in north-west Europe where he remained until the end of the war.

A short spell at Lympstone, now the RM Commando Training Centre, followed before we moved to Portsmouth in January 1947 where my education continued at Boundary Oak Prep School, an establishment not then noted for pastoral care. Beatings were run of the mill, boxing was mandatory and many of the masters were, with the benefit of hindsight, psychologically disturbed – possibly as a consequence of wartime service and what we now know as post-traumatic stress. I survived and left with a sound grounding in the ‘three Rs’ and a reputation as a good boxer having won my weight in inter-school competitions. Boxing taught me an early and valuable lesson. Rather fancying myself with my fists, I intervened in a fight when I saw a bigger boy bullying a friend. For my pains I in turn got beaten up. From this I deduced that electing to punch above your weight was not necessarily a good idea when given choice – a lesson of contemporary strategic and military relevance.

My parents planned for me to go on to Christ’s Hospital at Horsham. But in 1951 father was posted to Malaya as second-in-command of 40 Commando, Royal Marines. He took command a year later and was away for the best part of three years. Father decided I should stay at home and I was entered for Portsmouth Grammar School through common entrance examination. I joined PGS in the summer term of 1953 and to my surprise entered the A-stream which was full of academically gifted boys. Consequently I took my O levels shortly before my 15th birthday and my A levels two years later.

By contemporary standards my childhood was amazingly free and unrestricted, possibly because my father, a stern disciplinarian and very tough man, was away for much of the time leaving me in the care of my mother. She had trained as a nurse at St George’s Hospital then beside Hyde Park Corner and now the Lansdowne Hotel. She was an unconventional woman, entirely self-reliant with no interest in material things. She happily existed

on the bare necessities of life which were selected purely on their utility. On the other hand she was a voracious reader who in the 90 years of her life accumulated an amazing fund of general knowledge. Well into her seventies she could still demolish The Telegraph and Times crossword puzzles before lunch and she was the meanest of Scrabble players. Kind to a fault she nevertheless expected me to look after myself as indeed did my father. Thus from an early age a bicycle gave me the freedom to roam far and wide with my mother rightly assuming I would come home when hungry. As a schoolboy I was a keen supporter of Portsmouth Football Club when crowds of 40,000 were the norm at Fratton Park as Pompey ruled the roost in the First Division. Going to matches alone I cannot remember ever being frightened or experiencing crowd trouble. As I grew older I started to transfer my sporting allegiances to rugby and cricket, interests that survive to this day. But I still follow the fortunes and misfortunes of Portsmouth FC as an ingrained habit, and a fat lot of good that’s done them.

I enjoyed my three and a half years at PGS. The quality of teaching was superb and discipline maintained with firmness and fairness by masters who dominated by strength of personality rather than random and underserved beatings which I still associate with my prep school days. PGS was unashamedly meritocratic and educated boys from a wide mix of family backgrounds which generated an early and sympathetic social awareness to the benefit of all. Grammar schools were a great engine of social mobility – a reality of life ignored by the patrician socialists who helped to do away with them. My academic progress was unspectacular with cricket and rugby the principal focus of my energy, while girls from Portsmouth High School became something of a distraction. But I made some memorable friendships, among them Rudyard Penley. He entered the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst about the same time as I joined the RAF and was the first Sandhurst cadet to be commissioned directly into the Parachute Regiment. Sadly he was killed a few years later while participating in a parachute jumping competition. Also at PGS the teaching of an outstanding master, Ted Washington, developed my passion for history which over the years has concentrated mostly on military aspects with a special interest in the Georgian Navy as a result of many visits to HMS Victory and an early taste for the novels of C S Forrester. Years later my interest was reinvigorated by a naval friend who introduced me to the fascinating and exquisite tales fashioned by Patrick O’Brian. However, as a schoolboy I was also addicted to Biggles books by W E Johns, sadly no relation, which probably explains my early interest in

aviation. But I can also well recall my excitement at seeing for the first time a jet aeroplane flying at high speed and low level. I must have been about 12 at the time. The aircraft was a Supermarine Attacker of the Fleet Air Arm displaying at the RNAS Lee-on-Solent.

After joining the Combined Cadet Force at PGS – scouting offered the only escape – I transferred to the RAF section and eventually won a flying scholarship. This involved 30 hours flying, dual and solo, to achieve a Private Pilot’s Licence. I started on 1st August 1956, three days after my 17th birthday, and finished the course by the end of the month. At the same time I received the good news that I had passed my A levels, which together with a clutch of O levels, gained me exemption from the Civil Service Commission Navy, Army and Air Force Entry examination. My ambition to join the RAF, undimmed by early proximity to accident statistics, was now firm and I started the process of application with medical and flying aptitude tests at RAF Hornchurch and selection testing for a cadetship at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell.

My father’s friends could not understand why I did not want to follow him into the Royal Marines and fly with the Fleet Air Arm. For my part, badly bitten by the flying bug, it seemed to me that the service whose whole raison d’être centred on flying was the best place for a career in military aviation. Apart from condemnation as a black sheep by father’s pals, I have to admit that my childhood influence on his career was wholly negative. While at Deal in 1944 my parents took me to tea with his commanding officer and wife who lived in a Georgian house with a long, gently sloping lawn. For amusement, and out of adult sight, I played with a heavy garden roller. Unfortunately, with gravity proving the stronger, I lost control of the roller which accelerated down the lawn to smash into smithereens an ancestral statue much loved by the colonel.

Two years later at Lympstone my parents left me in the car while they enjoyed drinks in the mess after a Sunday church parade. Like the lawn at Deal, the car park had a distinctive slope such that when I released the handbrake – with nothing better to do – gravity again took control propelling the car backwards to achieve sufficient momentum for an effective and square-on collision with another vehicle. Both were prominently and undeniably damaged. The other car was owned by my father’s latest CO.

In my last year at home father decided to teach me poker. At first Sunday evenings passed pleasantly enough as we played for matchsticks until eventually I accepted his suggestion that we moved on to real money. Three weeks later I was in debt to the tune of two month’s pocket money and called quits.

Father’s comment was uncompromising. “You will never be any good at cards and you are a hopeless bluffer. My strongest advice to you is never gamble at cards.” I accepted his counsel and recouped my losses in my final Easter holiday with part-time employment as the stoker on Southsea miniature railway. It didn’t take long for my hands to blister from shovelling coal and I sought advice from the driver, a retired Welsh coal miner. “Go behind that bush,” he said “and pee on your hands. That will toughen them up.” And it did.

In early December 1956 a letter arrived from the Air Ministry requiring me to report to the Royal Air Force College Cranwell on 9th January 1957 for enlistment, this subject to my parent or guardian’s consent as I was just under the 17½ entry age limit to the college. My father signed with alacrity and took me to Moss Bros on The Hard outside Portsmouth dockyard where he bought me a suit, an overcoat and a pair of black shoes. “That’s the last you get out of me,” he said “you are now on your own.” He meant it as he stayed true to his word.

Some more words on my family background. My mother was the second daughter of a rich New Zealander who came to England for medical reasons just before World War I. He decided to stay and took up farming only to become a casualty of the economic crash in 1929; he was declared bankrupt in 1931. Thereafter he lived in a small terraced house in Horsham where my mother and I spent the first three years of my life. I remember my grandparents with great affection which probably points to the fact that I was a spoiled brat. The circumstances of my mother’s childhood also probably explains the fierce streak of independence which remained with her to the end of her life. Shortly before her death in hospital suffering from emphysema, she was asked if she had any allergies. “Yes,” replied mother “I am allergic to men with beards.” These were her last recorded words.

My father came from a less privileged background and a long line of Royal Navy seamen. He told me that one of his forebears had served on HMS Victory at Trafalgar. It is a fact that a ‘Johns’ was on the nominal roll of the crew in October 1805, but I have never verified the truth of this ancestral boast. His own father joined the Royal Navy as a boy seaman in 1898, retired as a chief yeoman of signals in 1922 and died shortly after of throat cancer. During World War I he was at sea throughout the conflict serving for the most part on the battleship HMS Hibernia. He was mentioned in despatches ‘in recognition of distinguished services during the war’. His death left my father as the eldest of three children with my grandmother, from memory a rather unpleasant and domineering person, looking to him as the principal

breadwinner for the family. Father was academically gifted with a particular bent for mathematics and the sciences as demonstrated by his distinguished examination achievements at the Royal Grammar School High Wycombe where he was considered a strong candidate for a university scholarship. However, grandmother insisted that he left school at 17 to take up employment as a bank clerk. This he tolerated for six months before enlisting in the Royal Marines without telling his mother. Subsequently my father paid her a portion of his income until she died in 1960.

After recruit training father served in HMS Suffolk on the Far East Station for two years before he was awarded a King’s Commission as a probationary second lieutenant. He passed out top of his training batch and was presented with a ceremonial sword for meritorious examinations by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. Far more than I was to achieve. He excelled at rifle shooting and, after World War II, captained the Royal Marines team and represented England at international events.

Following service with 40 Commando in Malaya and the Canal Zone he returned home as second-in-command of the Royal Marines barracks at Eastney in Portsmouth where we lived together for three years before I joined the RAF. In April 1957 he was told that he would be prematurely retired as a consequence of manpower reductions required by the Sandys Defence Review. Of his contemporaries he alone had not attended Staff College. He left the RM in August that year, two months before the announcement of a ‘golden bowler ’ scheme which would have made a significant difference to his financial wellbeing in the later years of his life. Short-changing service people who have given long and distinguished service to their country in war is by no means a new phenomenon.

Father never spoke about his wartime experiences and the only time he showed emotion was during a TV programme on the war at sea which explained the significance and dangers of Arctic convoys. As the story of PQ17 was told he spat out one word: “Shameful”. He died in 1977. His obituary in the Globe and Laurel, the journal of the Royal Marines, concluded:

“At the end of the day the real test of a man’s worth is his behaviour in adverse circumstances. When the going got rough it was a wonderful thing to have competent, tough, and utterly reliable Johnno at one’s side.”

I deeply regret not having learnt more about my father in his lifetime.

ChApter 2 CRANWELL

The aim of the RAF College was to train the future permanent officer cadre of the service. Some 300 flight cadets were resident for a course lasting three years with pilots going through basic and advanced flying training so that, on graduation and commissioning, they went straight to operational conversion units. Navigator flight cadet training followed a similar pattern while ground branch cadets (administrative and supply) completed their own specialist courses.

The first two terms at Cranwell were tough. The new intake was accommodated in the South Brick Lines (now demolished) – five new cadets with a mentor from the entry above. The daily routine was focused on drill (foot drill for the first term), kit cleaning and preparation, and academics which provided some welcome relief from other pressures deliberately applied to test resolve and commitment. In the second term, having passed off the square in foot drill, arms drill was introduced. However, before then our .303 Lee Enfield rifles, personally issued and retained for 2½ years, had to be burnished. Woodwork was bulled (spit and polished) with a mixture of ox blood and black shoe polish to the necessary high-gloss mahogany-coloured finish. On parade the first arms drill movement taught was ground arms which removed the bull from one side of the weapon to be replaced that evening with a further application of boot polish. I think my entry (No.76) was the last to endure this absurdity which was stopped on order from the Air Ministry but not before arms drill was mastered and the entry was judged fit to parade with the rest of the college.

Elsewhere a number of other hurdles were encountered. The first visit to the swimming pool, constructed within a World War I edifice, involved climbing into the rafters and jumping into the deep end; no-one asked if you could swim and some couldn’t. First term boxing against a flight cadet of approximate weight and height from another squadron was put on as after-dinner entertainment for the rest of the college. Some flying careers were inevitably lost to injuries incurred during the two-round slugging contest. Soon afterwards the junior entry was welcomed by the senior entries at a guest night

after which the juniors were obliged to entertain their seniors in the college lecture hall. Failure to provide adequate amusement earned a forfeit of fiendish ingenuity or physical discomfort. Walking 14 miles in the dead of night to recover drill boots from the satellite airfield at RAF Barkston Heath – placed there without the knowledge of the owner – in time for the morning drill parade was no joke.

The final hurdle at the end of the second term was survival camp held in the Hartz Mountains in Germany. Preliminary exercises concentrated on orientation and map reading with ever-increasing long marches in sections of a dozen or so to build up stamina and to test leadership. All of this was the preparation phase for a five-day escape-and-evasion exercise in three-man teams. Enemy forces were the German border guards, German customs police and British soldiers. We moved only at night from rendezvous (RV) to RV for further briefing on our ‘escape route’. If captured, the evaders were returned to their starting point to start all over again. Rations (emergency Mk 5 packs) sufficient for three days marching were provided which assumed that some ingredients could be ‘brewed up’. But as lighting fires in a densely forested region was forbidden, the entry returned home fit and certainly the leaner for a spot of leave before the start of the third term.

While the parade ground and academic subjects split between science and the humanities filled at least half the working day, sport of all disciplines, ranging from traditional activities – rugby, football, cricket etc – to the notso-common individual events within athletics and pentathlon, filled any spare time. With some 300 extremely fit young men, the majority medically fit for flying duties, it was not surprising that there was a wealth of sporting talent in the college. Cranwell more than held its own against the vastly superior numbers at Sandhurst. More importantly sport was the great mixer which brought together flight cadets from all levels within the college and from different squadrons, albeit inter-squadron sports competitions were fiercely contested, and on the rugby field, certainly not for the faint-hearted.

Discipline was rigidly enforced. Although expulsion was the ultimate punishment, restrictions or ‘strikers’ in the jargon of the day, confined miscreants to the bounds of the college with five extra parades a day; all involved a change of uniform and inspection with additional drill on two of the parades. A rather juvenile prank involving the assistant commandant’s car landed me and twelve others in hot water such that for some of us a greater part of our second term was spent on restrictions. Once on ‘strikers’ a spot of misplaced blanco could be punished immediately with two extra days by the inspecting

duty under officer. The challenge was to keep kit in a condition to pass inspection on both restrictions and entry drill parades. This forged a bond in adversity with roommates also under punishment. As all of us in my hut were charged and found guilty for our ‘impertinence’ with the assistant commandant’s car, we fashioned a production line of uniform and kit preparation which was a very model of the efficient use of time and space. Most regrettably two of the five of us, Euan Perreaux and Malcolm Maule, were killed in flying accidents after leaving Cranwell.

During our first two terms at Cranwell the flight commander in charge of all three flights within the junior entry was eminently forgettable. He was obsequious to his superiors and in awe of his senior NCO, one Flight Sergeant Jack Holt. Peter Symes, fellow flight cadet and old friend, described FS Holt as “a tall, barrel-chested Yorkshireman with a ruddy face sporting a stubby ginger moustache, hence his nickname ‘bog brush’. There was theatre in the man. While criticism was expressed with crystal clarity, its volume could reverberate. When drill was merely excellent he would glare in disdainful silence, amble off for a few paces, pause for effect and look to the heavens beseeching divine assistance. His pace stick was a designator as precise as any laser at marking out errant cadets. His invective was often spiced with brilliant metaphor and he drew some of his ammunition from circumstances of the Cold War, much of it unrepeatable in these days of political correctness. Certainly his dynamism, sheer force of personality and total commitment to his training duties left an indelible impression on the 1,300 or so cadets who passed through Cranwell in his years of service there.” Today a memorial is placed in a wall of the college bearing the inscription:

JACK HOLT MBE BEM

CADET WING FLIGHT SERGEANT 1952-1961

REVERED BY FLIGHT CADETS OF THAT ERA

If Jack Holt was the dominant influence in our day-to-day life within the junior entry, the college ethos with its clear focus on the development of commitment to the service was maintained with flinty resolution by the commandant and the assistant commandant. For most of my time at Cranwell these appointments were filled by Air Commodore D S Spotswood and Group Captain H N G Wheeler. Both were highly decorated for operational service in World War II with a brace of DSOs and several DFCs between them. The inner steel of the Cranwell hierarchy was of the highest quality and had no

trouble in dealing with mischief-making by high spirited flight cadets as I found out to my cost.

I did not enjoy my first year at Cranwell. The stern discipline, ruthless punishment of the most trifling misdemeanour, drill and then more drill with the fiercest attention paid to the most trivial details – as I judged them – was far removed from the familiar comforts of my home and school. Moreover, 24 hours basic navigation training, stuck down the back end of a tail-wheeled Valetta, was for me poor compensation for misfortunes of my own making suffered elsewhere within the college. But, and it is a very big but, like it or not I was learning self-discipline and to take strength from adversity while cultivating that certain bloody-mindedness which is the bedrock of determination to succeed. And I was making friendships, ever-strengthening during three years together as flight cadets, that have endured to this day.

The second and third years at Cranwell concentrated on professional development with the satisfactory completion of basic and advanced flying training earning pilots their ‘wings’ and navigators their brevets. Although my second year got off to a disappointing start, for the most part my memory is of much fun and laughter as we moved towards the goal of our passing-out parade as commissioned officers. In parallel with this process the ground-training syllabus aimed to exercise steady and controlled development of cadets towards the attainment of their commissions. For most of us this was a rather bumpy ride. The suspension rate was high, for example in No. 76 Entry only half of those who entered completed their training at Cranwell. In 1957 RAF manpower was in the order of 200,000 with National Service in full swing. Cadets could be suspended for a wide variety of reasons not to mention self-exclusion by those who found the regime at Cranwell intolerable. But given National Service manpower there was no problem in manning a front line of 11 commands worldwide and the instructional staff could afford to be choosy. Indeed, flight cadet scuttlebutt had it that a trip with the chief flying instructor at Barkston Heath was an automatic ‘chop ride’. This probably was the consequence of the wing commander being forced to bail out on his first flight with a cadet.

To correct a probable picture of a spartan existence, the second and third years at Cranwell permitted a gradual relaxation of the rules that governed the life of a ‘crow’ – a member of the junior entry. Selection for a sports team ensured some time away from the college while the occasional long weekend permitted absence from the compulsory Sunday morning church parades. During term time cadets attended a wide range of single and tri-service demonstrations and hosted incoming visits from foreign military academies, most

notably by the first class of cadets from the newly established United States Air Force Academy at Colorado Springs. Comparison of the Cranwell/Colorado Springs training convinced me that Cranwell was the easier and more enjoyable experience, a judgement warmly endorsed by contemporary USAF cadets who I was to meet again in the years ahead. Leave periods, coinciding with school holidays, were not holidays by definition. Cadets had to visit service installations, RN and Army as well as RAF, and participate in some authorised activity. My choice was offshore sailing and I am certain that my education benefited from early exposure to the traditions and attitudes of our sister services.

Off-duty, local pubs were guaranteed steady trade while invitations to dances at teacher’s training colleges – Lincoln and Retford come to mind –provided at least some opportunity to enjoy female company. Given the comparative geographical isolation at Cranwell, and with Sleaford out of bounds to flight cadets, the pleasures of off-duty relaxation were critically dependent on the availability of private transport. Cadets from their third term onwards were allowed to keep cars in the Cadet Wing garage, an old hangar in East Camp, long since demolished, which housed a remarkable collection of vehicles. A few contemporary sports cars and saloons financed by generous and rich parents represented the top end of the market. But by far the majority of vehicles were ‘bangers’ some of pre-war vintage characterised by mechanical under-reliability and questionable roadworthiness. Most bore the scars of misadventures with a few being obvious write-offs having suffered damage beyond economic repair. During their time as flight cadets, most suffered the indignity of a long trudge back to the college after a breakdown or prang. That no-one was killed in the days before ‘drink-drive’ and seat belts remains to me one of the sweet mysteries of life.

While I, and most of my friends, departed with a sense of pride and achievement, a minority within the entry to this day remain bitterly critical of a regime within which as much time was spent on the drill square (let alone in the preparation of kit) as was devoted to flying and other professional instruction. Although this imbalance of training effort was to continue for a few more years, the eventual replacement of the Piston Provost and Vampire/ Meteor by the Jet Provost introduced single-type flying training through to wings standard with a commensurate shortening of the course length. Within a decade the flight cadet entry was phased out to be replaced by the Graduate Entry Scheme in 1971.

A university degree became a prerequisite for a direct route permanent commission in the RAF. Like many other Old Cranwellians I was not

convinced by the rationale for such an abrupt change which apparently was based on the belief that the attainment of a degree was an essential precondition for a successful career. Failure to tap into this fashionable trend would leave the RAF at a disadvantage as other professions and our sister services sought to attract high quality candidates with proven intellectual capability for officer training. For my part I felt that the service was distancing itself too far from young men who would have preferred to fly military aircraft on leaving school rather than at the end of three years of abstract study of subjects many of which were of little relevance to a career in the RAF.

An obvious solution was for the service to introduce a programme which would allow officers to study for a degree, useful and valuable to the RAF, as their career progressed and at a time of their own choosing. Forty years later I was in a position to do something about this.

ChApter

ChApter 4 NIGHT FIGHTING

The Javelin OCU was based at RAF Leeming in North Yorkshire. The course started with two weeks ground school with pilots and navigator/radar operators learning the technical intricacies of the aeroplane. This fortnight also gave pilots and navigators (normally referred to as nav/rads) the chance to sniff around each other before deciding to pair up as constituted crews which would be posted to a front-line squadron at the end of the course. No surprise that none of the nav/rads seemed eager to join up with a 20-year-old guinea pig with only 320 hours in his logbook. But eventually Flying Officer David Holes, with a night-fighter Meteor tour under his belt, decided he would give me a go; my lucky break as he was the best nav/rad on the course. Before our first flight together he shook my hand and wished me the best of luck before he lowered himself into the rear cockpit. That was the start of a very happy association that saw us through the OCU and a full tour on 64 Squadron, first at RAF Duxford with subsequent moves to RAF Waterbeach and RAF Binbrook. Night fighting was a team effort. The nav/rad would commentate to the pilot once a target had been picked up with sharp instructions to manoeuvre the aircraft into an attack position. The pilot flew the aircraft with the highest achievable degree of accuracy in response to the navigator’s commentary which controlled speed, rate of climb and descent and turning performance. Speed increase/decrease instructions required 50 knots plus or minus; the huge, variable airbrakes could produce remarkable deceleration. ‘Starboard hard’ demanded a forty-five degrees bank level turn; harder and ease required 15 degrees addition or subtraction. Climb and descent instructions meant 2,000 feet rate of climb/descent. Each command required a precise flight configuration either singly or in combination. Within these broad parameters crew team work steadily developed to achieve ‘kills’ against evading targets on the darkest of nights. Training focused on visual identification of a target before engagement with either guns, or later on, Firestreak air-to-air missiles. The range of identification varied according to the light conditions. Pitch black and the aircraft would be closed to well under 100 yards before the pilot could make an accurate visual identification. On other nights the moon

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

of Insects get their living off this industrious creature. Another bee, Stelis nasuta, breaks open the cells after they have been completely closed and places its own eggs in them, and then again closes the cells with mortar. The larvae of this Stelis develop more rapidly than do those of the Chalicodoma, so that the result of this shameless proceeding is that the young one of the legitimate proprietor—as we human beings think it—is starved to death, or is possibly eaten up as a dessert by the Stelis larvae, after they have appropriated all the pudding.

Another bee, Dioxys cincta, is even more audacious; it flies about in a careless manner among the Chalicodoma at their work, and they do not seem to object to its presence unless it interferes with them in too unmannerly a fashion, when they brush it aside. The Dioxys, when the proprietor leaves the cell, will enter it and taste the contents; after having taken a few mouthfuls the impudent creature then deposits an egg in the cell, and, it is pretty certain, places it at or near the bottom of the mass of pollen, so that it is not conspicuously evident to the Chalicodoma when the bee again returns to add to or complete the stock of provisions. Afterwards the constructor deposits its own egg in the cell and closes it. The final result is much the same as in the case of the Stelis, that is to say, the Chalicodoma has provided food for an usurper; but it appears probable that the consummation is reached in a somewhat different manner, namely, by the Dioxys larva eating the egg of the Chalicodoma, instead of slaughtering the larva. Two of the Hymenoptera Parasitica are very destructive to the Chalicodoma, viz. Leucospis gigas and Monodontomerus nitidus; the habits of which we have already discussed (vol. v. p. 543) under Chalcididae. Lampert has given a list of the Insects attacking the mason-bee or found in its nests; altogether it would appear that about sixteen species have been recognised, most of which destroy the bee larva, though some possibly destroy the bee's destroyers, and two or three perhaps merely devour dead examples of the bee, or take the food from cells, the inhabitants of which have been destroyed by some untoward event. This author thinks that one half of the bees' progeny are made away with by these destroyers, while Fabre places the

destruction in the South of France at a still higher ratio, telling us that in one nest of nine cells, the inhabitants of three were destroyed by the Dipterous Insect, Anthrax trifasciata, of two by Leucospis, of two by Stelis, and of one by the smaller Chalcid; there being thus only a single example of the bee that had not succumbed to one or other of the enemies. He has sometimes examined a large number of nests without finding a single one that had not been attacked by one or other of the parasites, and more often than not several of the marauders had attacked the nest.

It is said by Lampert and others that there is a passage in Pliny relating to one of the mason-bees, that the Roman author had noticed in the act of carrying off stones to build into its nest; being unacquainted with the special habits of the bee, he seems to have supposed that the insect was carrying the stone as ballast to keep itself from being blown away.

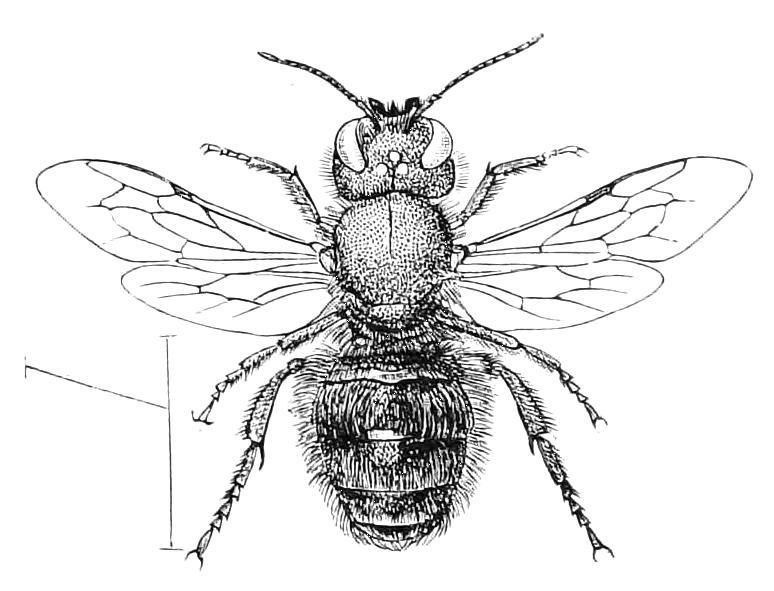

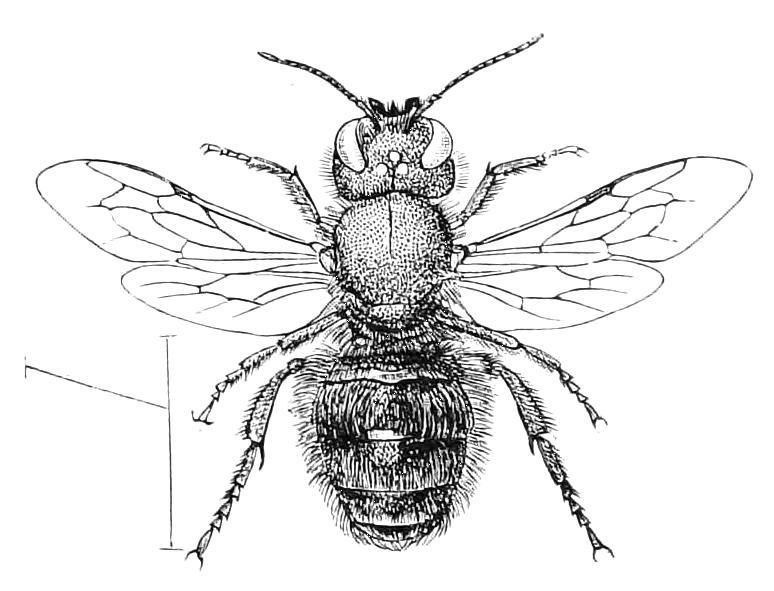

The bees of the genus Anthidium are known to possess the habit of making nests of wool or cotton, that they obtain from plants growing at hand. We have one species of this genus of bees in Britain; it sometimes may be seen at work in the grounds of our Museum at Cambridge: it is referred to by Gilbert White, who says of it, in his History of Selborne: "There is a sort of wild bee frequenting the garden-campion for the sake of its tomentum, which probably it turns to some purpose in the business of nidification. It is very pleasant to

Fig. 20 Anthidium manicatum, Carder-bee. A, Male; B, female.

see with what address it strips off the pubes, running from the top to the bottom of a branch, and shaving it bare with the dexterity of a hoop-shaver. When it has got a bundle, almost as large as itself, it flies away, holding it secure between its chin and its fore legs." The species of this genus are remarkable as forming a conspicuous exception to the rule that in bees the female is larger than the male. The species of Anthidium do not form burrows for themselves, but either take advantage of suitable cavities formed by other Insects in wood, or take possession of deserted nests of other bees or even empty snail-shells. The workers in cotton, of which our British species A. manicatum is one, line the selected receptacle with a beautiful network of cotton or wool, and inside this place a finer layer of the material, to which is added some sort of cement that prevents the honied mass stored by the bees in this receptacle from passing out of it. A. diadema, one of the species that form nests in hollow stems, has been specially observed by Fabre; it will take the cotton for its work from any suitable plant growing near its nest, and does not confine itself to any particular natural order of plants, or even to those that are indigenous to the South of France. When it has brought a ball of cotton to the nest, the bee spreads out and arranges the material with its front legs and mandibles, and presses it down with its forehead on to the cotton previously deposited; in this way a tube of cotton is constructed inside the reed; when withdrawn, the tube proved to be composed of about ten distinct cells arranged in linear fashion, and connected firmly together by means of the outer layer of cotton; the transverse divisions between the chambers are also formed of cotton, and each chamber is stored with a mixture of honey and pollen. The series of chambers does not extend quite to the end of the reed, and in the unoccupied space the Insect accumulates small stones, little pieces of earth, fragments of wood or other similar small objects, so as to form a sort of barricade in the vestibule, and then closes the tube by a barrier of coarser cotton taken frequently from some other plant, the mullein by preference. This barricade would appear to be an ingenious attempt to keep out parasites, but if so, it is a failure, at any rate as against Leucospis, which insinuates its eggs through the sides, and frequently destroys to the last one the inhabitants of the fortress. Fabre states that these

Anthidium, as well as Megachile, will continue to construct cells when they have no eggs to place in them; in such a case it would appear from his remarks that the cells are made in due form and the extremity of the reed closed, but no provisions are stored in the chambers.

The larva of the Anthidium forms a most singular cocoon. We have already noticed the difficulty that arises, in the case of these Hymenopterous larvae shut up in small chambers, as to the disposal of the matters resulting from the incomplete assimilation of the aliment ingested. To allow the once-used food to mingle with that still remaining unconsumed would be not only disagreeable but possibly fatal to the life of the larva. Hence some species retain the whole of the excrement until the food is entirely consumed, it being, according to Adlerz, stored in a special pouch at the end of the stomach; other Hymenoptera, amongst which we may mention the species of Osmia, place the excreta in a vacant space. The Anthidium adopts, however, a most remarkable system: about the middle of its larval life it commences the expulsion of "frass" in the shape of small pellets, which it fastens together with silk, as they are voided, and suspends round the walls of the chamber. This curious arrangement not only results in keeping the embarrassing material from contact with the food and with the larva itself, but serves, when the growth of the latter is accomplished, as the outline or foundations of the cocoon in which the metamorphosis is completed. This cocoon is of a very elaborate character; it has, so says Fabre, a beautiful appearance, and is provided with a very peculiar structure in the form of a small conical protuberance at one extremity pierced by a canal. This canal is formed with great care by the larva, which from time to time places its head in the orifice in process of construction, and stretches the calibre by opening the mandibles. The object of this peculiarity in the fabrication of the elaborate cocoon is not clear, but Fabre inclines to the opinion that it is for respiratory purposes.

Other species of this genus use resin in place of cotton as their working material. Among these are Anthidium septemdentatum and

A. bellicosum The former species chooses an old snail-shell as its nidus, and constructs in it near the top a barrier of resin, so as to shut off the part where the whorl is too small; then beneath the shelter of this barrier it accumulates a store of honey-pollen, deposits an egg, and completes the cell by another transverse barrier of resin; two such cells are usually constructed in one snail-shell, and below them is placed a barricade of small miscellaneous articles, similar to what we have described in speaking of the cotton-working species of the genus. This bee completes its metamorphosis, and is ready to leave the cell in early spring. Its congener, A. bellicosum, has the same habits, with the exception that it works later in the year, and is thus exposed to a great danger, that very frequently proves fatal to it. This bee does not completely occupy the snail-shell with its cells, but leaves the lower and larger portion of the shell vacant. Now, there is another bee, a species of Osmia, that is also fond of snail-shells as a nesting-place, and that affects the same localities as the A. septemdentatum; very often the Osmia selects for its nest the vacant part of a shell, the other part of which is occupied by the Anthidium; the result of this is that when the metamorphoses are completed, the latter bee is unable to effect its escape, and thus perishes in the cell. Fabre further states with regard to these interesting bees, that no structural differences of the feet or mandibles can be detected between the workers in cotton and the workers in resin; and he also says that in the case where two cells are constructed in one snailshell, a male individual is produced from the cell of the greater capacity, and a female from the other.

Osmia is one of the most important of the genera of bees found in Europe, and is remarkable for the diversity of instinct displayed in the formation of the nests of the various species. As a rule they avail themselves for nidification of hollow places already existing; choosing excavations in wood, in the mortar of walls, and even in sandbanks; in several cases the same species is found to be able to adapt itself to more than one kind of these very different substances. This variety of habit will render it impossible for us to do justice to this interesting genus within the space at our disposal, and we must content ourselves with a consideration of one or two of the more

instructive of the traits of Osmia life. O. tridentata forms its nest in the stems of brambles, of which it excavates the pith; its mode of working and some other details of its life have been well depicted by Fabre. The Insect having selected a suitable bramble-stalk with a cut extremity, forms a cylindrical burrow in the pith thereof, extending the tunnel as far as will be required to allow the construction of ten or more cells placed one after the other in the axis of the cylinder; the bee does not at first clear out quite all the pith, but merely forms a tunnel through it, and then commences the construction of the first cell, which is placed at the end of the tunnel that is most remote from the entrance. This cavity is to be of oval form, and the Insect therefore cuts away more of the pith so as to make an oval space, but somewhat truncate, as it were, at each end, the plane of truncation at the proximal extremity being of course an orifice.

The first cell thus made is stored with pollen and honey, and an egg is deposited. Then a barrier has to be constructed to close this chamber; the material used for the barrier is the pith of the stem, and the Insect cuts the material required for the purpose from the walls of the second chamber; the excavation of the second chamber is, in fact, made to furnish the material for closing up the first cell. In this way a chain of cells is constructed, their number being sometimes as many as fifteen. The mode in which the bees, when the transformations of the larvae and pupae have been completed, escape from the chain of cells, has been the subject of much discussion, and errors have arisen from inference being allowed to take the place of observation. Thus Dufour, who noted this same mode of construction and arrangement in another Hymenopteron (Odynerus nidulator), perceived that there was only one orifice of exit, and also that the Insect that was placed at the greatest distance

Fig 21 Osmia tricornis, ♀ Algeria

from this was the one that, being the oldest of the series, might be expected to be the first ready to emerge; and as the other cocoons would necessarily be in the way of its getting out, he concluded that the egg that was last laid produced the first Insect ready for emergence. Fabre tested this by some ingenious experiments, and found that this was not the case, but that the Insects became ready to leave their place of imprisonment without any reference to the order in which the eggs were laid, and he further noticed some very curious facts with reference to the mode of emergence of Osmia tridentata Each Insect, when it desires to leave the bramble stem, tears open the cocoon in which it is enclosed, and also bites through the barrier placed by the mother between it and the Insect that is next it, and that separates it from the orifice of exit. Of course, if it happen to be the outside one of the series it can then escape at once; but if it should be one farther down in the Indian file it will not touch the cocoon beyond, but waits patiently, possibly for days; if it then still find itself confined it endeavours to escape by squeezing past the cocoon that intervenes between it and liberty, and by biting away the material at the sides so as to enlarge the passage; it may succeed in doing this, and so get out, but if it fail to make a side passage it will not touch the cocoons that are in its way. In the ordinary course of events, supposing all to go well with the family, all the cocoons produce their inmates in a state for emergence within a week or two, and so all get out. Frequently, however, the emergence is prevented by something having gone wrong with one of the outer Insects, in which case all beyond it perish unless they are strong enough to bite a hole through the sides of the bramble-stem. Thus it appears that whether a particular Osmia shall be able to emerge or not depends on two things—(1) whether all goes well with all the other Insects between it and the orifice, and (2) whether the Insect can bite a lateral hole or not; this latter point also largely depends on the thickness of the outer part of the stem of the bramble. Fabre's experiments on these points have been repeated, and his results confirmed by Nicolas.

The fact that an Osmia would itself perish rather than attack the cocoon of its brother or sister is certainly very remarkable, and it

induced Fabre to make some further experiments. He took some cocoons containing dead specimens of Osmia, and placed them in the road of an Osmia ready for exit, and found that in such case the bee made its way out by demolishing without any scruple the cocoons and dead larvae that intervened between it and liberty. He then took some other reeds, and blocked the way of exit with cocoons containing living larvae, but of another species of Hymenoptera. Solenius vagus and Osmia detrita were the species experimented on in this case, and he found that the Osmia destroyed the cocoon and living larvae of the Solenius, and so made its way out. Thus it appears that Osmia will respect the life of its own species, and die rather than destroy it, but has no similar respect for the life of another species.

Some of Fabre's most instructive chapters are devoted to the habits and instincts of various species of the genus Osmia. It is impossible here to find space even to summarise them, still more impossible to do them justice; but we have selected the history just recounted, because it is rare to find in the insect world instances of such selfsacrifice by an individual for one of the same generation. It would be quite improper to generalise from this case, however, and conclude that such respect for its own species is common even amongst the Osmia. Fabre, indeed, relates a case that offers a sad contrast to the scene of self-sacrifice and respect for the rights of others that we have roughly portrayed. He was able to induce a colony of Osmia tricornis (another species of the genus, be it noted) to establish itself and work in a series of glass tubes that he placed on a table in his laboratory. He marked various individuals, so that he was able to recognise them and note the progress of their industrial works. Quite a large number of specimens thus established themselves and concluded their work before his very eyes. Some individuals, however, when they had completed the formation of a series of cells in a glass tube or in a reed, had still not entirely completed their tale of work. It would be supposed that in such a case the individual would commence the formation of another series of cells in an unoccupied tube. This was not, however, the case. The bee preferred tearing open one or more cells already completed—in

some cases, even by itself—scattering the contents, and devouring the egg; then again provisioning the cell, it would deposit a fresh egg, and close the chamber. These brief remarks will perhaps suffice to give some idea of the variety of instinct and habit that prevails in this very interesting genus. Friese observes that the variety of habits in this genus is accompanied as a rule by paucity of individuals of a species, so that in central Europe a collector must be prepared to give some twenty years or so of attention to the genus before he can consider he has obtained all the species of Osmia that inhabit his district.

As a prelude to the remarks we are about to make on the leaf-cutting bees of the genus Megachile it is well to state that the bee, the habits of which were described by Réaumur under the name of "l'abeille tapissière," and that uses portions of the leaves of the scarlet poppy to line its nest, is now assigned to the genus Osmia, although Latreille, in the interval that has elapsed since the publication of Réaumur's work, founded the genus Anthocopa for the bee in question. Megachile is one of the most important of the genera of the Dasygastres, being found in most parts of the world, even in the Sandwich Islands; it consists of bees averaging about the size of the honey-bee (though some are considerably larger, others smaller), and having the labrum largely developed; this organ is capable of complete inflection to the under side of the head, and when in the condition of repose it is thus infolded, it underlaps and protects the larger part of the lower lip; the mandibles close over the infolded labrum, so that, when the Insect is at rest, this appears to be altogether absent. These bees are called leaf-cutters, from their habit of forming the cells for their nest out of pieces of the leaves of plants. We have several species in Britain; they are very like the common honey-bee in general appearance, though rather more robustly formed. These Insects, like the Osmiae, avail themselves of existing hollow places as receptacles in which to place their nests. M. albocincta frequently takes possession of a deserted wormburrow in the ground. The burrow being longer than necessary the bee commences by cutting off the more distant part by means of a barricade of foliage; this being done, it proceeds to form a series of

cells, each shaped like a thimble with a lid at the open end (Fig. 22, A). The body of the thimble is formed of large oval pieces of leaf, the lid of smaller round pieces; the fragments are cut with great skill from the leaves of growing plants by the Insect, which seems to have an idea of the form and size of the piece of foliage necessary for each particular stage of its work.

Fig 22 Nidification of leaf-cutting bee, Megachile anthracina A, one cell separated, with lid open; the larva (a) reposing on the food; B, part of a string of the cells (After Horne )

Horne has given particulars as to the nest of Megachile anthracina (fasciculata), an East Indian species.[30] The material employed was either the leaves of the Indian pulse or of the rose. Long pieces are cut by the Insect from the leaf, and with these a cell is formed; a circular piece is next cut, and with this a lid is made for the receptacle. The cells are about the size and shape of a common thimble; in one specimen that Horne examined no less than thirtytwo pieces of leaf disposed in seven layers were used for one cell, in addition to three pieces for the round top. The cells are carefully prepared, and some kind of matter of a gummy nature is believed to be used to keep in place the pieces forming the interior layers. The cells are placed end to end, as shown in Fig. 22, B; five to seven cells form a series, and four or six series are believed to be constructed by one pair of this bee, the mass being located in a hollow in masonry or some similar position. Each cell when completed is half filled with pollen in the usual manner, and an egg is then laid in it. This bee is much infested by parasites, and is eaten by the Grey Hornbill (Meniceros bicornis).

Megachile lanata is one of the Hymenoptera that in East India enter houses to build their own habitations. According to Horne both sexes take part in the work of construction, and the spots chosen are frequently of a very odd nature. The material used is some kind of clay, and the natural situation may be considered to be the interior of a hollow tube, such as the stem of a bamboo; but the barrel of a gun, and the hollow in the back of a book that has been left lying open, have been occasionally selected by the Insect as suitable. Smith states that the individuals developed in the lower part of a tubular series of this species were females, "which sex takes longer to develop, and thus an exit is not required for them so soon as for the occupants of the upper cells which are males." M. proxima, a species almost exactly similar in appearance to M. lanata, makes its cells of leaf-cuttings, however, and places them in soft soil.

Fabre states that M. albocincta, which commences the formation of its nest in a worm-burrow by means of a barricade, frequently makes the barricade, but no nest; sometimes it will indeed make the barricade more than twice the proper size, and thus completely fill up the worm burrow. Fabre considers that these eccentric proceedings are due to individuals that have already formed proper nests elsewhere, and that after completing these have still some strength remaining, which they use up in this fruitless manner.

The Social bees (Sociales) include, so far as is yet known, only a very small number of genera, and are so diverse, both in habits and structure, that the propriety of associating them in one group is more than doubtful; the genera are Bombus (Fig. 331, vol. v.), with its commensal genus or section, Psithyrus (Fig 23); Melipona (Fig. 24), in which Trigona and Tetragona may at present be included, and Apis (Fig. 6); this latter genus comprising the various honey-bees that are more or less completely domesticated in different parts of the world.

In the genus Bombus the phenomena connected with the social life are more similar to what we find among wasps than to what they are

in the genus Apis The societies come to an end at the close of the season, a few females live through the winter, and each of these starts a new colony in the following spring. Males, females and workers exist, but the latter are not distinguished by any good characters from the females, and are, in fact, nothing but more or less imperfect forms thereof; whereas in Apis the workers are distinguished by structural characters not found in either of the true sexes.

Hoffer has given a description of the commencement of a society of Bombus lapidarius. [31] A large female, at the end of May, collected together a small mass of moss, then made an expedition and returned laden with pollen; under cover of the moss a cell was formed of wax taken from the hind-body and mixed with the pollen the bee had brought in; this cell was fastened to a piece of wood; when completed it formed a subspherical receptacle, the outer wall of which consisted of wax, and whose interior was lined with honeysaturated pollen; then several eggs were laid in this receptacle, and it was entirely closed. Hoffer took the completed cell away to use it for museum purposes, and the following day the poor bee that had formed it died. From observations made on Bombus agrorum he was able to describe the subsequent operations; these are somewhat as follows:—The first cell being constructed, stored, and closed, the industrious architect, clinging to the cell, takes a few days' rest, and after this interval commences the formation of a second cell; this is placed by the side of the first, to which it is connected by a mixture of wax and pollen; the second cell being completed a third may be formed; but the labours of the constructor about this time are augmented by the hatching of the eggs deposited a few days previously; for the young larvae, having soon disposed of the small quantity of food in the interior of the waxen cell, require feeding. This operation is carried on by forming a small opening in the upper part of the cell, through which the bee conveys food to the interior by ejecting it from her mouth through the hole; whether the food is conveyed directly to the mouths of the larvae or not, Hoffer was unable to observe; it being much more difficult to approach this royal founder without disturbing her than it is the worker-bees that carry on

similar occupations at a subsequent period in the history of the society. The larvae in the first cell, as they increase in size, apparently distend the cell in an irregular manner, so that it becomes a knobbed and rugged, truffle-like mass. The same thing happens with the other cells formed by the queen. Each of these larval masses contains, it should be noticed, sister-larvae all of one age; when full grown they pupate in the mass, and it is worthy of remark that although all the eggs in one larval mass were laid at the same time, yet the larvae do not all pupate simultaneously, neither do all the perfect Insects appear at once, even if all are of one sex. The pupation takes place in a cocoon that each larva forms for itself of excessively fine silk. The first broods hatched are formed chiefly, if not entirely, of workers, but small females may be produced before the end of the season. Huber and Schmiedeknecht state that though the queen provides the worker-cells with food before the eggs are placed therein, yet no food is put in the cells in which males and females are produced. The queen, at the time of pupation of the larvae, scrapes away the wax by which the cocoons are covered, thus facilitating the escape of the perfect Insect, and, it may also be, aiding the access of air to the pupa. The colony at first grows very slowly, as the queen can, unaided, feed only a small number of larvae. But after she receives the assistance of the first batch of workers much more rapid progress is made, the queen greatly restricting her labours, and occupying herself with the laying of eggs; a process that now proceeds more and more rapidly, the queen in some cases scarcely ever leaving the nest, and in others even becoming incapable of flight. The females produced during the intermediate period of the colony are smaller than the mother, but supplement her in the process of egg-laying, as also do the workers to a greater or less extent. The conditions that determine the egglaying powers of these small females and workers are apparently unknown, but it is ascertained that these powers vary greatly in different cases, so that if the true queen die the continuation of the colony is sometimes effectively carried on by these her former subordinates. In other cases, however, the reverse happens, and none of the inhabitants may be capable of producing eggs: in this event two conditions may be present; either larvae may exist in the

nest, or they may be absent. In the former case the workers provide them with food, and the colony may thus still be continued; but in the latter case, there being no profitable occupation for the bees to follow, they spend the greater part of the time sitting at home in the nest.

Supposing all to go well with the colony it increases very greatly, but its prosperity is checked in the autumn; at this period large numbers of males are produced as well as new queens, and thereafter the colony comes to an end, only a few fertilised females surviving the winter, each one to commence for herself a new colony in the ensuing spring.

The interior of the nest of a bumble-bee (Bombus) frequently presents a very irregular appearance; this is largely owing to the fact that these bees do not use the cells as cradles twice, but form others as they may be required, on the old remains. The cells, moreover, are of different sizes, those that produce workers being the smallest, those that cradle females being the largest, while those in which males are reared are intermediate in size. Although the old cells are not used a second time for rearing brood they are nevertheless frequently adapted to the purposes of receptacles for pollen and for honey, and for these objects they may be increased in size and altered in form.

It may be gathered from various records that the period required to complete the development of the individual Bombus about midsummer is four weeks from the deposition of the egg to the emergence of the perfect Insect, but exact details and information as to whether this period varies with the sex of the Insect developed are not to be found. The records do not afford any reason for supposing that such distinction will be found to exist: the size of the cells appears the only correlation, suggested by the facts yet known, between the sex of the individual and the circumstances of development.

The colonies of Bombus vary greatly in prosperity, if we take as the test of this the number of individuals produced in a colony. They never, however, attain anything at all approaching to the vast number of individuals that compose a large colony of wasps, or that exist in the crowded societies of the more perfectly social bees. A populous colony of a subterranean Bombus may attain the number of 300 or 400 individuals. Those that dwell on the surface are as a rule much less populous, as they are less protected, so that changes of weather are more prejudicial to them. According to Smith, the average number of a colony of B. muscorum in the autumn in this country is about 120—viz. 25 females, 36 males, 59 workers. No mode of increasing the nests in a systematic manner exists in this genus; they do not place the cells in stories as the wasps do; and this is the case notwithstanding the fact that a cell is not twice used for the rearing of young. When the ground-space available for cellbuilding is filled the Bombus begins another series of cells on the ruins of the first one. From this reason old nests have a very irregular appearance, and this condition of seeming disorder is greatly increased by the very different sizes of the cells themselves. We have already alluded to some of these cells, more particularly to those of different capacities to suit the sexes of the individuals to be reared in them. In addition to these there are honey-tubs, pollentubs, and the cells of the Psithyrus (Fig. 23), the parasitic but friendly inmates of the Bombus-nests. A nest of Bombus, exhibiting the various pots projecting from the remains of empty and partially destroyed cells, presents, as may well be imagined, a very curious appearance. Some of the old cells apparently are partly destroyed for the sake of the material they are composed of. Others are formed into honey-tubs, of a make-shift nature. It must be recollected that, as a colony increases, stores of provisions become absolutely necessary, otherwise in bad weather the larvae could not be fed. In good weather, and when flowers abound, these bees collect and store honey in abundance; in addition to placing it in the empty pupacells, they also form for it special receptacles; these are delicate cells made entirely of wax filled with honey, and are always left open for the benefit of the community. The existence of these honey-tubs in bumble-bees' nests has become known to our country urchins,

whose love for honey and for the sport of bee-baiting leads to wholesale destruction of the nests. According to Hoffer, special tubs for the storing of pollen are sometimes formed; these are much taller than the other cells. The Psithyrus that live in the nests with the Bombus are generally somewhat larger than the latter, and consequently their cells may be distinguished in the nests by their larger size. A bumble-bees' nest, composed of all these heterogenous chambers rising out of the ruins of former layers of cells, presents a scene of such apparent disorder that many have declared that the bumble-bees do not know how to build.

Although the species of Bombus are not comparable with the hivebee in respect of the perfection and intelligent nature of their work, yet they are very industrious Insects, and the construction of the dwelling-places of the subterranean species is said to be carried out in some cases with considerable skill, a dome of wax being formed as a sort of roof over the brood cells. Some work even at night. Fea has recorded the capture of a species in Upper Burmah working by moonlight, and the same industry may be observed in this country if there be sufficient heat as well as light. Godart, about 200 years ago, stated that a trumpeter-bee is kept in some nests to rouse the denizens to work in the morning: this has been treated as a fable by subsequent writers, but is confirmed in a circumstantial manner by Hoffer, who observed the performance in a nest of B. ruderatus in his laboratory. On the trumpeter being taken away its office was the following morning filled by another individual The trumpeting was done as early as three or four o'clock in the morning, and it is by no means impossible that the earliness of the hour may have had something to do with the fact that for 200 years no one confirmed the old naturalist's observation.

One of the most curious facts in connection with Bombus is the excessive variation that many of the species display in the colour of the beautiful hair with which they are so abundantly provided. There is not only usually a difference between the sexes in this respect, but also extreme variation within the limits of the same sex, more

especially in the case of the males and workers; there is also an astonishing difference in the size of individuals. These variations are carried to such an extent that it is almost impossible to discriminate all the varieties of a species by inspection of the superficial characters. The structures peculiar to the male, as well as the sting of the female, enable the species to be determined with tolerable certainty. Cholodkovsky,[32] on whose authority this statement as to the sting is made, has not examined it in the workers, so that we do not know whether it is as invariable in them as he states it to be in queens of the same species. According to Handlirsch,[33] each species of Bombus has the capacity of variation, and many of the varieties are found in one nest, that is, among the offspring of a single pair of the species, but many of the variations are restricted to certain localities. Some of the forms can be considered as actual ("fertige") species, intermediate forms not being found, and even the characters by which species are recognised being somewhat modified. As examples of this he mentions Bombus silvarum and B. arenicola, B. pratorum and B. scrimshiranus. In other cases, however, the varieties are not so discontinuous, intermediate forms being numerous; this condition is more common than the one we have previously described; B. terrestris, B. hortorum, B. lapidarius and B. pomorum are examples of these variable species. The variation runs to a considerable extent in parallel lines in the different species, there being a dark and a light form of each; also each species that has a white termination to the body appears in a form with a red termination, and vice versa. In the Caucasus many species that have everywhere else yellow bands possess them white; and in Corsica there are species that are entirely black, with a red termination to the body, though in continental Europe the same species exhibit yellow bands and a white termination to the body. With so much variation it will be readily believed that much remains to be done in the study of this fascinating genus. It is rich in species in the Northern hemisphere, but poor in the Southern one, and in both the Ethiopian and Australian regions it is thought to be entirely wanting.

The species of the genus Psithyrus (Apathus of many authors) inhabit the nests of Bombus; although less numerous than the species of the latter genus, they also are widely distributed. They are so like Bombus in appearance that they were not distinguished from them by the earlier entomologists; and what is still more remarkable, each species of Psithyrus resembles the Bombus with which it usually lives. There appear, however, to be occasional exceptions to this rule, Smith having seen one of the yellow-banded Psithyrus in the nest of a red-tailed Bombus. Psithyrus is chiefly distinguished from Bombus by the absence of certain characters that fit the latter Insects for their industrial life; the hind tibiae have no smooth space for the conveyance of pollen, and, so far as is known, there are only two sexes, males and perfect females.

Fig. 23 Psithyrus vestalis, Britain. A, Female, x 3⁄2; B, outer side of hind leg.

The Bombus and Psithyrus live together on the best terms, and it appears probable that the latter do the former no harm beyond appropriating a portion of their food supplies. Schmiedeknecht says they are commensals, not parasites; but it must be admitted that singularly few descriptions of the habits and life-histories of these interesting Insects have been recorded. Hoffer has, however, made a few direct observations which confirm, and at the same time make more definite, the vague ideas that have been generally prevalent among entomologists. He found and took home a nest of Bombus variabilis, which contained also a female of Psithyrus campestris, so that he was able to make observations on the two. The Psithyrus was much less industrious than the Bombus, and only left the nest somewhat before noon, returning home again towards evening; after about a month this specimen became still more inactive, and passed entire days in the nest, occupying itself in consuming the stores of honey of its hosts, of which very large quantities were absorbed, the Psithyrus being much larger than the host-bee. The cells in which the young of the Psithyrus are hatched are very much larger than those of the Bombus, and, it may therefore be presumed, are formed by the Psithyrus itself, for it can scarcely be supposed that the Bombus carries its complaisance so far as to construct a cell specially adapted to the superior stature of its uninvited boarder When a Psithyrus has been for some time a regular inhabitant of a nest, the Bombus take its return home from time to time as a matter of course, displaying no emotion whatever at its entry. Occasionally Hoffer tried the introduction of a Psithyrus to a nest that had not previously had one as an inmate. The new arrival caused a great hubbub among the Bombus, which rushed to it as if to attack it, but did not do so, and the alarm soon subsided, the Psithyrus taking up

the position in the nest usually affected by the individuals of the species. On introducing a female Psithyrus to a nest of Bombus in which a Psithyrus was already present as an established guest, the latter asserted its rights and drove away the new comer. Hoffer also tried the experiment of placing a Psithyrus campestris in the nest of Bombus lapidarius—a species to which it was a stranger; notwithstanding its haste to fly away, it was at once attacked by the Bombus, who pulled it about but did not attempt to sting it.

When Psithyrus is present in a nest of Bombus it apparently affects the inhabitants only by diminishing their stores of food to so great an extent that the colony remains small instead of largely increasing in numbers. Although Bombus variabilis, when left to itself, increases the number of individuals in a colony to 200 or more, Hoffer found in a nest in which Psithyrus was present, that on the 1st of September the assemblage consisted only of a queen Bombus and fifteen workers, together with eighteen specimens of the Psithyrus, eight of these being females.

The nests of Bombus are destroyed by several animals, probably for the sake of the honey contained in the pots; various kinds of small mammals, such as mice, the weasel, and even the fox, are known to destroy them; and quite a fauna of Insects may be found in them; the relations of these to their hosts are very little known, but some undoubtedly destroy the bees' larvae, as in the case of Meloe, Mutilla and Conops. Birds do not as a rule attack these bees, though the bee-eater, Merops apiaster, has been known to feed on them very heavily.

The genera of social bees known as Melipona, Trigona or Tetragona, may, according to recent authorities, be all included in one genus, Melipona. Some of these Insects are amongst the smallest of bees, so that one, or more, species go by the name of "Mosquito-bees." The species appear to be numerous, and occur in most of the tropical parts of the continents of the world, but unfortunately very little is known as to their life-histories or economics; they are said to