Gürsel

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/image-brokers-visualizing-world-news-in-the-age-of-di gital-circulation-zeynep-devrim-gursel/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

News in a Digital Age Comparing the Presentation of News Information over Time and across Media Platforms

Jennifer Kavanagh

https://textbookfull.com/product/news-in-a-digital-age-comparingthe-presentation-of-news-information-over-time-and-across-mediaplatforms-jennifer-kavanagh/

Frontiers Of Digital Transformation: Applications Of The Real-World Data Circulation Paradigm Kazuya Takeda

https://textbookfull.com/product/frontiers-of-digitaltransformation-applications-of-the-real-world-data-circulationparadigm-kazuya-takeda/

Fake News, Propaganda, and Plain Old Lies: How to Find Trustworthy Information in the Digital Age Donald A. Barclay

https://textbookfull.com/product/fake-news-propaganda-and-plainold-lies-how-to-find-trustworthy-information-in-the-digital-agedonald-a-barclay/

Dynamics of News Reporting and Writing Foundational Skills for a Digital Age 1st Edition Vincent F. Filak

https://textbookfull.com/product/dynamics-of-news-reporting-andwriting-foundational-skills-for-a-digital-age-1st-editionvincent-f-filak/

History Year by Year The History of the World From the Stone Age to the Digital Age 2nd Edition Dk

https://textbookfull.com/product/history-year-by-year-thehistory-of-the-world-from-the-stone-age-to-the-digital-age-2ndedition-dk/

Cinema in the Digital Age Nicholas Rombes

https://textbookfull.com/product/cinema-in-the-digital-agenicholas-rombes/

Digital Peripheries The Online Circulation of Audiovisual Content from the Small Market Perspective

Petr Szczepanik

https://textbookfull.com/product/digital-peripheries-the-onlinecirculation-of-audiovisual-content-from-the-small-marketperspective-petr-szczepanik/

Skeletal Circulation In Clinical Practice World Scientific 2016 Roy Kenneth Aaron

https://textbookfull.com/product/skeletal-circulation-inclinical-practice-world-scientific-2016-roy-kenneth-aaron/

Bodies of Work: The Labour of Sex in the Digital Age

Rebecca Saunders

https://textbookfull.com/product/bodies-of-work-the-labour-ofsex-in-the-digital-age-rebecca-saunders/

Introduction

Formative Fictions and the Work of News Images

A messenger walked over to Jackie’s cubicle and delivered a large envelope. Jackie, a photo editor at Global Views Inc., shoved it to a corner of her desk, not hiding her exasperation: “It’s Friday afternoon. The magazines are about to close, and this photographer sends me film!” Jackie worked in the New York office of Global Views Inc. (GVI), a visual content provider. It was March 21, 2003, the day the United States and coalition forces launched a massive aerial assault on Baghdad, what the US military and media referred to as the “shock and awe” campaign. Emphatically Jackie pointed at the envelope full of rolls of film: “Unprocessed film!” Though they had arrived by express courier and had been shot only two days earlier, it was clear that these undeveloped rolls of photographs of protests in California against the imminent Iraq war could not keep pace with the digital news cycle. They were historical artifacts, obsolete even before being developed. Jackie wasn’t going to call a photo editor at Time or Newsweek or any other magazine to tell them about these photographs. She wasn’t going to try to sell them by making an argument that they provided a fresh angle on the state of a nation on the brink of war or that this photographer’s personal vision illuminated something new about antiwar rallies. In fact, the rolls of film didn’t even get processed before the following week, when they were digitized and immediately archived and linked to images of Americans protesting wars past, instantly becoming potential historical images for a future date. Before the end of the first day

of the 2003 American war in Iraq, one thing was certain: this was a digital war.

Jackie is a professional image broker. Her work and that of other image brokers is the central topic of this book. Image brokers act as intermediaries for images through acts such as commissioning, evaluating, licensing, selling, editing, and negotiating. They may or may not be the producers or authors of images. Rather, image brokers are the people who move images or restrict their movement, thereby enabling or policing their availability to new audiences. For example, by not developing the film sent to her immediately, Jackie kept the images on the rolls of film out of circulation for several days. We can think of many different kinds of image brokers—from art dealers to those uploading videos onto YouTube; however, I focus on those who broker news images professionally. These individuals—the people making the decisions behind the photographs we encounter in the news—and the organizations in which they work, whether agencies, publications, or visual content providers, act as mediators for views of the world. Image brokers collectively frame our ways of seeing.1

This is a book about photography and journalism based on fieldwork conducted at a time when the form and the content of both were significantly unsettled. I look back to a period of major technological and professional transformation in the news media, one during which the very infrastructures of representation were changing radically.2 The shift to digital photography and satellite communication on the cusp of the new millennium occurred with shocking rapidity; it allowed photographs to be transmitted from anywhere in the world and made available online almost instantly. Some news publications had printed digital images considered to have unique journalistic value as early as 1998, during the coverage of the war in Kosovo.3 By early 2003, having the capability to transmit digitally was essential for a photographer to even get an assignment in Iraq. At least two of the older veteran combat photographers, who didn’t yet feel entirely comfortable shooting digital images, had gone to Iraq accompanied by young assistants to provide them technical support. Perhaps the starkest monument marking the material changes in the photojournalism industry was a sign placed on the now-obsolete chute that for decades had been used to send rolls of film down to the photo lab at a major US newsmagazine. The sign read: “RIP (Rest in Peace).”

To observe the international photojournalism industry during this time of uncertainty, I conducted over two years of fieldwork at key

nodal points of production, reproduction, distribution, and circulation in the industry’s centers of power: New York and Paris. I use the term nodal point deliberately, because I sought out points of intersection among various actors and institutions, junctions in a system where choices had to be made such as which images to select, which publications to pitch them to, where to make them available, and what to assign to a specific photographer.4 From 2003 to 2005 I conducted fieldwork in the newsroom of a large corporate “visual content” provider (chapter 2); the Paris headquarters of Agence France-Presse (chapter 3), a French wire service; and the editorial offices of two mainstream US newsmagazines (chapter 4). I also attended several key photography events, principal among them Barnstorm (chapter 5), a photography workshop for emerging photographers founded and run for many years by Eddie Adams, an American photojournalist who made several iconic images of the Vietnam war;5 Visa Pour l’Image (chapter 6), the largest annual photojournalism festival, held in Perpignan, France; and several events organized by World Press Photo (chapter 7), an Amsterdambased international platform for documentary photography that organizes the world’s most prestigious annual photography competition and also offers seminars on photojournalism. I began this project because I believed that the manner in which the world was depicted photographically had significant consequences and was an increasingly central part of politics. As I watched what began as a war that had to be covered digitally become a digital war of images, I grew increasingly convinced of the political potential of visual journalism. It is far too important a practice not to be scrutinized and engaged analytically.

A TIME OF RAPID CHANGE

The beginning of the American war in Iraq was a moment when photojournalism as a domain was uncertain.6 This uncertainty stemmed from digitalization. Whereas digitization has been defined as “the material process of converting analogue streams of information into digital bits,” digitalization refers to the way many domains of social life, including journalism and military operations, are “restructured around digital communication and media infrastructures.”7

Photojournalism was transformed not only by digital cameras, online distribution, and the digitization of analog archives, but by the significant institutional and cultural changes that digitalization enabled. The war in Iraq was not just a digital war, but also the first war in which

visual content providers were important image brokers. For example, Global Views Inc., where Jackie worked as part of the news and editorial team, is not a news organization but rather a visual content provider—a corporation that produces licensable imagery and for whom news is just one of many product lines. Hence, regardless of their personal beliefs and motivations, Jackie and her GVI colleagues were producing and selling visual content, commodities that just happened to begin their lives as representations of news. They were not part of the press. Yet during the year that I observed daily work at GVI, I watched Jackie and the rest of the editorial team broker many of the most significant and widely publicized journalistic images of the early war in Iraq. As Jackie edited them for GVI’s digital archive, they were transformed into visual content, available for purchase for a range of editorial and commercial uses. I researched photojournalism as the production and distribution process behind news images increasingly became part of the commodity chain behind visual content.

Another manifestation of digitalization was the change in the very nature of the “photojournalism community.” Amateur digital images such as the Abu Ghraib photos and cell-phone pictures of the 2005 London bombings, rather than the work of professional photojournalists, were the key images that shaped public opinion. Moreover, images in the press, from photographs to cartoons, were not just illustrative of current events but often also newsworthy themselves or even factors in causing events, thereby playing a critical and highly controversial part in political and military action.8

In other words, I studied a very loose community of people collectively engaged in visual knowledge production at a time when the core technologies of their craft, the status of the images they produced and brokered, and their own professional standing amid a growing pool of amateurs and citizen journalists were all changing rapidly. As a result, the professional identity of image brokers, the very value of their expertise, and the ways in which images entered into journalistic circulation were hotly debated topics worldwide. Conducting fieldwork during tumultuous times yielded informants who were constantly questioning and negotiating what their professional world would look like, endlessly debating where their field of expertise began and ended or could be extended.9 This was very fortunate for me as an anthropologist. As long as I was in the right places, there was no need to provoke conversations about the state of visual journalism; I could just listen in on conversations that were already taking place regularly.10

It was also a time when there was a very dominant news stóry that concerned a great many journalists. This book opened with Jackie at her desk a few hours after television news had shown footage of “shock and awe.” However, the dominant news story in question was not just the American war in Iraq, which would in fact go on for almost nine years and was a significant event itself. Rather, the news story that dominated journalism and formed the backdrop of my fieldwork was neither the war in Iraq nor the war in Afghanistan but the “War on Terror.” This was a significant journalistic dominant because this was not an actual war but a discursive construct that as an umbrella term provided semantic coherence for a whole range of activities, both within the United States and internationally. The “War on Terror” is not a single event or an actual war, then, but a war that was actualized, made real, in part by news coverage of it. Throughout this book when I refer to the War on Terror (without quotation marks from here on), it is this mediated idea of a military campaign against terrorism activities that I am referencing. The War on Terror is inseparable from its representations; it is always also a war of images.11

SEPTEMBER 11–13, 2001

Not only are the War on Terror and its representations inseparable, but September 11, 2001, is a key, if controversial, originary moment for both the United States’s military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the professional transition to digital photography. It is common knowledge that there had been terrorist attacks before, even at the same site—the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. The 9/11 attacks were events of a different scale. Similarly, the first digital camera system marketed to professional photojournalists was introduced by Kodak in 1991, but even a decade later, many in the professional world of photography still resisted using digital images because of what they perceived as inferior image quality. However, when the Federal Aviation Administration grounded all flights for three days following the attacks of September 11, 2001, the photojournalism industry was obliged to accept digital transmission regardless of whether the photographs being transmitted were analog or digitally produced images; images could move only digitally. The pace and scale of the digital circulation of news images changed dramatically. The standard of sending undeveloped rolls of film via air, and consequently predigital technologies and scales of circulation, were grounded along with the US airline industry. Only

a year and a half later Jackie was astounded that a photographer shooting a time-sensitive topic such as antiwar protests could possibly send images he had shot in California to New York as film, let alone unprocessed film.

The inseparability of the War on Terror and its representations can also be attributed to the fact that the hijackers who crashed two planes into the World Trade Center launched an attack in the realm of the image world at the same time as their attack on the physical towers and the Pentagon. As has been noted at length elsewhere, this was an act of spectacular terrorism not just because of the images of fireballs and gaping buildings but also because, due to the delay between the two crashes, millions of spectators drawn to their screens to view the aftermath of one attack witnessed the second attack and eventually the crumbling of the towers on live television. Hence, the events inaugurated a new type of spectacular terrorism where a visual assault on spectators magnified the symbolic impact of the physical attack and prepared the way for visual revenge.12 The intertwining of the War on Terror and the worldwide circulation of digital images was perhaps nowhere more evident than in the notorious photographs of American torture in Abu Ghraib prison. However, rather than approach these images as the images of the war, Image Brokers provides the context of a visual and political economy of images in which the Abu Ghraib images were merely some of the most controversial and widely circulated.13

Yet for all the claims about the future of visual news being radically transformed by digitalization and forever changed by the FAA ban, much of the work of the image brokers I observed was structured by ideologies about photojournalism and institutional protocols that had long histories. If I wanted to understand how news images functioned by analyzing image brokers, their work, and the contexts in which this work was performed, I couldn’t simply begin with digital photojournalism. Therefore, this book is on one level an institutional narrative telling the story of technological innovation, a now-historical account focusing on a thin slice of time: the early twenty-first century and the beginning of the War on Terror. Yet on another level it is an attempt to address, through the work of contemporary image brokers, some questions about documentary images and their relationship to political imaginations that long predate digital journalism. Moreover, although this book builds on scholarship about images of suffering and atrocity, I did long-term fieldwork with image brokers to be able to analyze such images alongside frames of everyday life.14 I agree with the critical

importance of analyzing what philosopher Judith Butler calls “frames of war.” Yet each time we focus our scholarship exclusively on conflict photography we risk narrowing our investigation in ways similar to how the US military manages visual access through embed positions. By not focusing exclusively on the coverage of war or of atrocities but rather on the everyday work of images brokers, I hope to render visible how framing mechanisms are always at work—with significant political ramifications—before, during, after, and alongside military action.15

I could not hope to understand how photographs moved and accrued value through their international circulation by studying any one institution or subject matter. So rather than analyze a single object of mass media in a bounded geographical setting—news images of Afghanistan or photographs in the French press—this book focuses on the networks through which international news images move. It highlights the structural limitations and possibilities that shape decisions about news images as well as their use in contemporary ways of worldmaking.

Not all photographs are news images. Certain photographs become news images through their circulation.16 For example, a family photograph of former president of Iraq Saddam Hussein became a news image once it was removed from the album in his palace and circulated as a visual document of an opulent lifestyle, one that interested news publications could purchase for use.17 To understand news images, we need to attend not only to the specific frame in question, with its particular aesthetic and material qualities, whether film or digital, but also to the context in which any particular photograph is produced and the route it travels to become news.18 Though credited to a single individual when credit information is provided at all, a news image is produced by a network. After the photographer’s initial framing of the shot, the final image encountered in a publication has passed in front of the eyes— and, until recently, through the hands—of several decision makers: image brokers and their institutions. The business of news images can be seen as a global industry: the raw material comes from many different locations, the labor is often mobile, and once packaged, the products can travel around the world as complete packages or as material to be repackaged as part of new assemblages. Although on some level this is a commodity chain similar to others, manufacturing news as a product line (journalistic “content”), it is also a genre of knowledge production, a mode of worldmaking through which we understand the times and places in which we live. Hence, news images are very particular products.

LOOKING AT THE WORLD PICTURE

When the photograph shown in figure 1 appeared in the New York Times on October 31, 2005, the caption read, “Taj Mian looked at his village, Gantar, from a Pakistani Army helicopter as he and about 50 of his neighbors were evacuated last week. He had never before left Gantar, which lies in the Allai Valley, one of the areas hit hardest by the earthquake on Oct. 8.” The photograph, taken by American photographer Kate Brooks, is beautifully composed, highly evocative, and what photo editors would call a “very quiet” photograph, one that does not shout death or devastation. It is the type of image that rarely gets chosen for a daily news publication because it does not directly depict an event. It appeared in black and white on page 4 of the New York Times more than three weeks after other images accompanied the news of the earthquake on the front page. By then, the earthquake in Pakistan had become visually recognizable to news followers.

It is a remarkable photograph for being a news image about looking. What it shows is the act of someone looking at a landscape. It is a photograph that allows the viewer to look together with a villager named Taj Mian down at his village a few weeks after it had been destroyed by an earthquake. The image invites the viewer to put herself in the position of Taj Mian, to peek over his shoulder and see what he sees, to imagine how horrific it must be to look down on one’s home and see it in ruins. And yet, if the information reported in the caption is accurate—that Taj Mian had never before left Gantar and therefore presumably never before been on a helicopter—then the blurred image of devastation outside the helicopter window is much more recognizable to the average New York Times reader than to the man in the photograph whose vantage point we are invited to share. The viewer is familiar with aerial shots of rubble if only from prior readings of newspapers, whereas Taj Mian is presumably adjusting his visual repertoire to comprehend a bird’s-eye perspective. Perhaps he is comparing it with views he has seen from hills or mountains he has climbed.

If we read this news image with a critical eye, there can be no pretense that we are seeing through Taj Mian’s eyes. We cannot see as he sees. Rather, the stark frame of the helicopter window underscores that, like Taj Mian, we are looking from a particular place. This photograph about looking shows how what we see is framed.19 The camera is in a particular place. The photographer has found a way of getting herself on a particular helicopter. Her agent in New York has circulated the

1. A villager being evacuated after the October 8, 2005, earthquake in Pakistan. New York Times, October 31, 2005. Photograph by Kate Brooks/Polaris. Used by the kind permission of the photographer.

resulting images, and some have crossed the desk of a photo editor at the New York Times. The photo editor has, perhaps alone, likely in discussion with others, selected this frame to accompany the article alongside which the readers of the newspaper encountered it. Someone has made decisions about its layout and caption. The technologies of image production and transportation, questions of access, and all of the procedures of getting in place to take the photograph in the first place— critical issues left out of the frames of most journalistic images—are hinted at, if not represented, in this photograph.

I draw attention to the mythology of seeing through another’s eyes and all it obscures to emphasize that the act of looking is itself a cultural construction. The ability to see, and to interpret what one sees, as someone else is a powerful fantasy. In 1974 anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously claimed that “the culture of a people is an ensemble of texts, themselves ensembles, which the anthropologist strains to read over the shoulders of those to whom they properly belong.”20 Geertz suggested that societies told themselves stories about themselves and that the anthropologist, too, could learn to read these stories or texts from the perspective of the native over whose shoulder he or she was reading. A little over a decade later another anthropologist, Vincent Crapanzano, convincingly argued that there is no understanding of the native from the native’s point of view: “There is only the constructed understanding of the constructed native’s constructed point of view.”21 In other words, Geertz’s metaphor is a layering of fictions, and, in Crapanzano’s reading of the text that can be read over the native’s shoulder, it is a particularly problematic layering of fictions in which hierarchy and power relations are disturbingly occluded.22

It is precisely such power relations that Brooks’s photograph offers us an opportunity to grasp. I am not claiming that this particular image was taken, brokered, or published with this particular interpretation or intention in mind. Rather, my reading of this digital image underscores the need to remain aware of the layering of decisions, and the complex layering of attitudes and differences that are behind news images. News images have limited journalistic and analytic value if they serve merely to reinforce stereotypes and provoke knee-jerk expressions of pity.23 But if they provoke questions and provide an opening for acknowledging the possibility of difference without assuming a facile understanding of the other, then they can contribute to a nuanced type of knowledge production.

In the last chapter of his book What Do Pictures Want?, entitled “Showing Seeing,” art historian W. J. T. Mitchell draws attention to “a

paradox that can be formulated in a number of ways: that vision is itself invisible; that we cannot see what seeing is.”24 Mitchell then describes an assignment for his students that requires them to show seeing in some way, as if they were ethnographers “who come from, and are reporting back to, a society that has no concept of visual culture.”25 One might read Image Brokers as a manner of taking up the challenge posed by Mitchell’s assignment. This book is about making visible the infrastructures of representation behind the work of image brokers: the institutions, processes, networks, and social relations behind news images. Image Brokers shows how decisions are made about what news audiences see.

News images are an important component of contemporary visual culture. They are complex cultural products. They circulate as representations of reality—photographs of the world as it is—but they are also aesthetic interpretations and commodities.26 They are concrete, fixed things even when digital, yet they also mediate abstract ideas about people, places, and their identities.27 News images perform political and cultural work in the world precisely because they are perceived as truthful, visual facts—facts both in the original sense of things that are made and in the sense of things that provide objective information about the world.28 As I will explain at length, news images are “formative fictions,” constructed representations that reflect current events yet simultaneously shape ways of imagining the world and political possibilities within it. As formative fictions, news images have consequences and play a role in worldmaking. For the large numbers who see them, news images are part of how we construct not just our points of view, but also our very understanding of the world at large in which we formulate our points of view. They influence us today and also have an impact on the way we will assimilate that which we have not yet seen but might see tomorrow.

The very first paragraph of Susan Sontag’s 1977 book On Photography ends with her claiming that “[f]inally, the most grandiose result of the photographic enterprise is to give us the sense that we can hold the whole world in our heads—as an anthology of images.”29 The next paragraph begins, “To collect photographs is to collect the world.” Sontag was specifically addressing material collections of photographs and the ramifications of photographs being tangible physical objects—unlike films and television images, which flicker ephemerally. Over twenty years before Sontag published what remains one of the most widely read texts on photography, philosopher Martin Heidegger claimed that “the fact that the world becomes picture at all is what distinguishes the

essence of the modern age.” He clarified precisely what he meant: “[W]orld picture, when understood essentially, does not mean a picture of the world but the world conceived and grasped as picture.”30 Heidegger is not speaking of photography or of specific pictures of the world but rather of the very idea that the world can be knowable as an object, grasped as a picture. Yet in highlighting the greatest possible stakes for photography—holding the whole world in our heads as an anthology of images—Sontag might as well be picking up Heidegger’s idea of a world picture and asking how photographic technologies contributed to its development and shaped its contemporary forms. It is precisely this kind of a collecting the world in our heads to which news images contribute.

If we return to the image of Taj Mian looking out the helicopter window, it is fairly easy to reflect on the photographer’s physical presence: she must have been somewhere behind him in the helicopter to make such an image. But to reflect on the photograph and its circulation as a news image, one would need to understand the work of the image brokers whose desks it had crossed and the editing practices of the specific institutions involved. One might begin by turning to a photograph like that on the cover of this book, titled “The World on a Wire,” which also offers us the fiction of seeing through the eyes of someone—in this case, a photo editor at a wire service. Before her are hundreds of photographs of news events that she must edit and push out to subscribers around the world, each of whom is in turn making news for some kind of publication. My aim in what follows is not to present a Geertzian reading of the cultural texts before her in an effort to capture her point of view as a native in the photojournalism world, but rather to render visible precisely the processes by which international news images are constructed as cultural texts that shape journalists’ and news consumers’ own points of view. Visualizing world news is not merely about specific representations of particular news events but also about how events are made visible to the mind, how they are imagined by readers.

In the fall of 2001, I conducted research on American news readers’ reactions to images of the attacks of September 11. Many people I interviewed conveyed their difficulty in recognizing the place captioned “ground zero” in news images as a location in New York City or even within the United States. They made comments such as “That looks like Bosnia,” or Lebanon or, forebodingly, Iraq. News images they had seen in the past served as formative fictions, shaping their ideas of these distant places and producing a distance from the events in New York.31 These readers’ reactions convinced me that how a place or population

is imaged affects what one can imagine happening in that place or to that people, hence shaping the sphere of political possibility. Put simply, news images matter.32

Professional image making is central to processes of worldmaking, a term I borrow from philosopher Nelson Goodman. Goodman emphasizes that representations are central to worldmaking and contribute to the understanding but also the building of realities in which we live.33 Moreover, worldmaking involves both ideological and material structures, and it was both of these that I investigated in my research on the international community responsible for providing us with daily visual knowledge of the world beyond our immediate experience. My approach parallels that of journalism scholar Pablo Boczkowski, who underscores that “media innovation unfolds through the interrelated mutations in technology, in communication and in organization.”34 I concur entirely with his insistence that materiality matters in newsrooms.

This project began from a curiosity about photography as a form of journalism. It follows in the tradition of newsroom ethnographies, though my focus was always on images—specifically, ones visualizing international news.35 Walter Lippman’s 1922 classic Public Opinion begins with a chapter titled “The World Outside and the Pictures in Our Head,” and this project began quite simply from a desire to think about how literal pictures of world news were constructed and how they got into the heads of journalists and readers.36 I wanted to understand how news images were mobilized for various publics and the repercussions for both those photographed and the consumers of images. However, I began by asking who was behind the production of news images and soon discovered how little I knew.

One way to research documentary photography has been to consider the individuals involved in a photographic encounter. For example, an investigation might center on the subject or subjects in an image.37 Another way it has been studied is by focusing on the photographers who take these images.38 Yet another approach focuses on audiences’ interpretations, how images affect viewers, often focusing on specific iconic photographs and their uptake by various publics.39 Much compelling work in the field considers photography from several of these perspectives.40 Visual studies scholar Ariella Azoulay has proposed “a new ontological political understanding of photography [which] takes into account all the participants in photographic acts—camera, photographer, subject and spectator—approaching the photograph (and its meaning) as an unintentional effect of the encounter between all of

these.”41 And yet, at least in regards to news images, this list—camera, photographer, subject, and spectator—is not exhaustive. Those left out are the image brokers. In the end, although this book germinated from research on what work news images did in the world, it developed instead to address the work of image brokers behind these images’ production and circulation—work that is typically invisible.

NEWS IMAGES AS FICTIONS

Documentary photographic representations were long believed to be beyond forgery. Soon after photography’s invention and dizzying diffusion in the mid–nineteenth century, photographic realism and the expanding institution of journalism became integrally linked. The term daguerreotype, the name of one of the first photographic processes, came to mean any study that claimed absolute honesty. In the United States, there was widespread “typification of the newspaper as a daguerreotype of the social and natural world.” In fact, the New York Herald newspaper was described in 1848 as “the daily daguerreotype of the heart and soul of the model republic.”42

As my argument will make clear, I consider news images to be particularly rich fictions in the original sense of things that are fashioned or formed. Hence, the key issue for me is not whether news images are honest or manipulated: I begin from the premise that all representations are fictions in the sense that they are constructed.43 The central question I am interested in is how certain fictions circulate with evidentiary or truth value while others do not.

In his book Keywords, cultural critic Raymond Williams informs us that the same Latin root (fingere) that produced the word fiction in the sense of “to fashion or form” also produced feign, underlining the ties between fiction, novels, and news.44 It is precisely this persistence of the threat of deception that makes fiction an interesting category. According to Williams, the word fiction took on particular literary significance in the eighteenth century and became almost synonymous with novel in the nineteenth century as the genre flourished. Terms often beget their opposites, and it was the popularity of novels that led to the invention in the twentieth century of a category of nonfiction, initially used by libraries and those in the book trade. Against the rising tide of novels, Williams explains, this new category of nonfiction was “at times made equivalent to ‘serious’ reading; some public libraries will reserve or pay postage on any non-fiction but refuse these facilities for fiction.”

In other words nonfiction, “serious reading,” is institutionally subsidized and aided in its circulation in ways not extended to novels. Williams, moreover, discusses categories within fiction and highlights a distinction that was made between bad novels, which are pure fictions, and those that are serious fictions, earning this description by telling us about real life.45

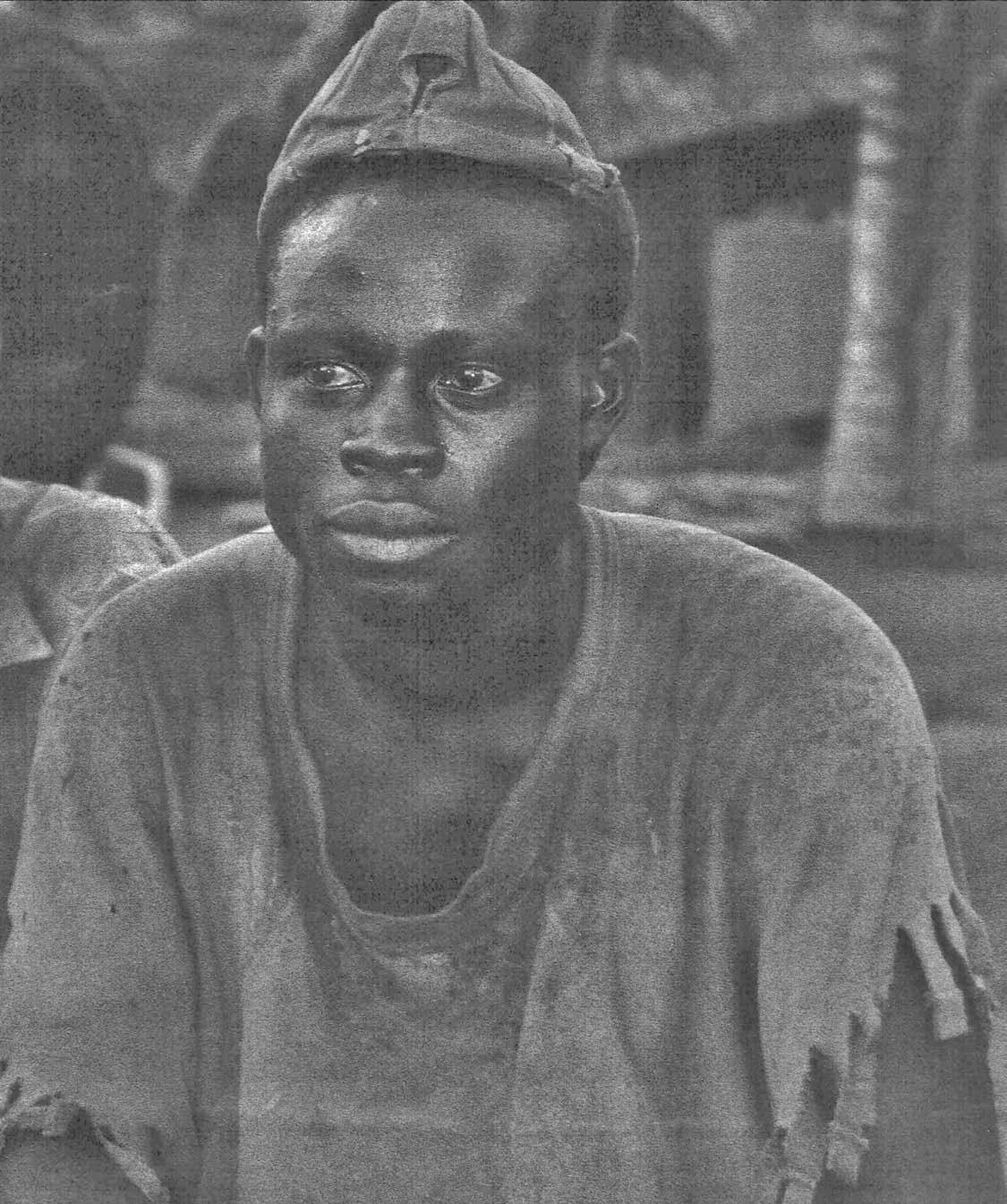

What might such different kinds of fictions look like in journalism? A curious six-paragraph editor’s note appeared in the New York Times on February 21, 2002, announcing that Michael Finkel, a freelancer under contract as a contributing writer to the newspaper’s magazine, would not receive further assignments from the paper.46 A year later Finkel’s trespass was completely overshadowed by writer Jayson Blair’s resignation from the same paper for falsifying information, and the following years brought so many examples that one might claim that this form of public acknowledgment of compromised journalism became a subgenre of the news.47 However, at the time of its publication, the editor’s note regarding Finkel’s article “Is Youssouf Malé a Slave?” was still remarkable. What exactly had Finkel done to be so publicly chastised and fired?

Figure 2 shows the first two pages of the original article as they appeared in the New York Times Magazine on November 18, 2001. Below is an excerpt from the February 21, 2002, editor’s note describing Finkel’s use of fiction:

The article was illustrated with photographs, including one taken by the writer, an uncaptioned full-page image of a youth. On Feb. 13, the writer, Michael Finkel, informed The Times that an official of Save the Children had contacted him to say that in investigating the case, the agency had located the boy in the picture, and that he was not Youssouf Malé [the boy supposedly described in the article]. The editors then questioned the writer and began to make their own inquiries to verify the article’s account. The writer, a freelancer, then acknowledged that the boy in the article was a composite, a blend of several boys he interviewed, including one named Youssouf Malé and another, the boy in the picture, identified by Save the Children as Madou Traoré. Though the account was drawn from his reporting on the scene and from interviews with human rights workers, Mr. Finkel acknowledges, many facts were extrapolated from what he learned was typical of boys on such journeys, and did not apply specifically to any single individual.48

Had he not submitted the photograph for publication, Finkel might very well not have been caught. The rest of Finkel’s article might have been read as “a serious fiction that tells us about real life” in Raymond Williams’s formulation discussed above. Whereas the identification of

FIGURE 2. Opening two pages of an article by freelance journalist Michael Finkel. New York Times Magazine, November 18, 2001. Photograph by Michael Finkel.

the specific boy in the image by the wrong name was undeniably a falsehood. Due to its indexical nature, a photograph of a person is always a fact that applies “specifically to [a] single individual.” For the New York Times, Finkel’s portrait of Malé was pure fiction.

Finkel’s trespass, as the editors explained in their lengthy note, lay in his “improper narrative techniques.” The editor’s note ended with this major national newspaper spelling out to its readers: “The Times’ policies prohibit falsifying a news account or using fictional devices in factual material.” The specific narrative technique that was considered a fictional device was the use of a composite character and the falsification of time sequences that it necessitated.

Were it not for the fact that both youths are part of a larger group that might be considered child slaves, the New York Times would not be interested in the particular stories of either Youssouf Malé or Madou Traoré. The story gets assigned because there is some indication that a particular condition may apply to a collective. Individuals are sought out for interviews as representatives of this collective, and, in fact, there is little room in traditional journalistic representations for particular facts about any noncelebrity individual that do not apply to a collective. The story is what is typical of boys on such journeys. However, at the moment of crafting a photographic representation, and perhaps only at this moment, the journalist must acknowledge the individual as a unique individual and not part of a composite.

Photographic representation pushes journalistic limits in a critical manner, and differently from writing. Susan Sontag draws attention to one peculiarity of authenticity in photographic representation: “A painting or drawing is judged a fake when it turns out not to be by the artist to whom it had been attributed. A photograph . . . is judged a fake when it turns out to be deceiving the viewer about the scene it purports to depict.”49 The particular form of authenticity in news images is due to a specific characteristic of photography: each body in a photograph is highly singular and indexed to a particular individual, and yet many of the bodies in news images—almost all except images of celebrities—circulate as stand-ins for large numbers of bodies sharing the same condition, bodies that are metonyms for social bodies. 50 News images offer points of departure for imagining collectives that are represented but not present in the frame itself. We read about “Iraqis” or “women” or “Brazilians” as composite subjects in journalism every day when clearly the information is extrapolated from specific individuals. These texts can be accompanied by images of identified or unidentified individuals, yet this practice seems ethically

questionable only when a photographic image is explicitly incorrectly identified. Hence, news images circulate based on their ability to contribute to the visual construction of a social body. This is how they function as formative fictions. Yet, as the Finkel case demonstrates, we demand different levels of accuracy in the identification of indexed bodies.

INDEXED BODIES, REPRESENTED SOCIAL BODIES

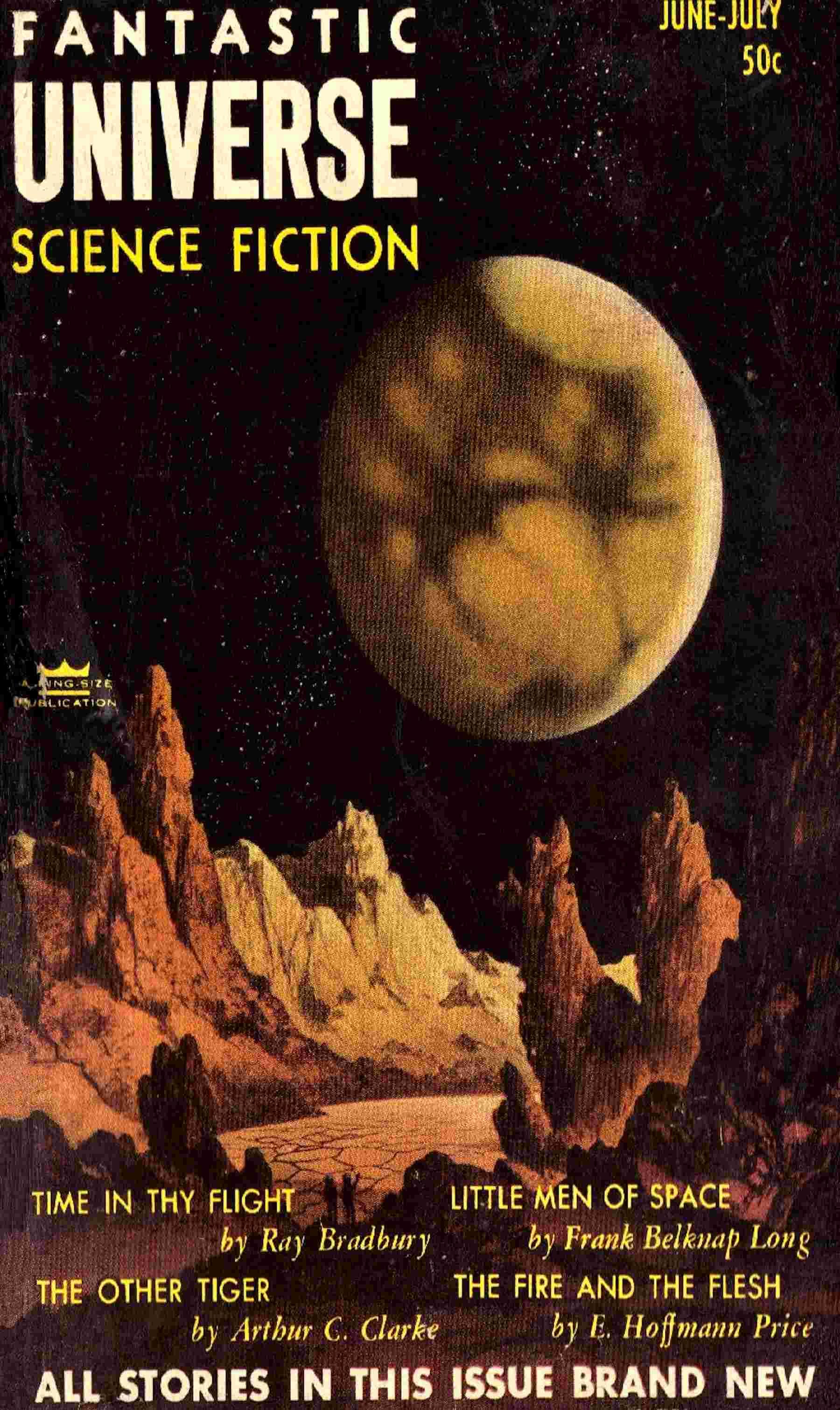

At times a single face can come to represent an entire country’s population. Perhaps the best-known example of this is Steve McCurry’s famous “Afghan Girl” image that appeared on a 1985 cover of National Geographic (figure 3).

Figure 3 is an indexical representation of Sharbat Gula, an Afghan girl who moved to Pakistan as a refugee. Her image initially appeared with no identifying name; she was merely one of 2.4 million Afghan refugees, and one of 350 female students at a school mentioned in the article, as her persistent pseudonym—Afghan girl—reminds us. That particular photograph indexed only her, and yet it also represented Afghan refugees in general.

In April 2002, a year after the War on Terror had commenced and Afghanistan was once again in the news, Sharbat Gula once again appeared on the cover of National Geographic. Cutting-edge biometric technology was used to identify Gula’s irises, and a particular thirtyyear-old woman was confirmed to be the girl in the famous National Geographic photograph. This time Gula was clad in a burqa and held a copy of the portrait of her younger self (figure 4).

A caption tells us, “She had not been photographed since Steve McCurry made her portrait in 1984, and she only agreed to be photographed again—to appear unveiled, without her burqa—because her husband told her it would be proper.” In this cover photograph, she serves as a human easel for the iconic image made of her eighteen years earlier.51 The only visual individuality allowed to her by National Geographic, an entity stricter even than Gula’s husband, is a reference back to their photographer’s encounter with her. Hence, even when she is again on the cover of National Geographic for being the specific individual indexed in the earlier photograph, in the political climate of 2002 when liberating Afghan women was one of the alleged goals of the military operation in Afghanistan, she once again represents the category of Afghan women in general. To return to the language of the New York Times’s editor’s note, her portrait is a representation of what is typical of

Afghan women. Though the 2002 article rejoices that “[n]ow we can tell her story,” we get only the bare details about her, and the writer underscores repeatedly that many share her story. McCurry’s portrait of Sharbat Gula is merely an aggregate of what is portrayed as Afghanistan’s timeless, almost naturalized, plight of despair and poverty. US military operations in Afghanistan that began in October 2001 are not mentioned in the story at all, even though it took the US invasion to render Afghanistan a cover-worthy topic once again.52 Through such images, viewers learn to associate certain places and certain peoples with a certain “look.” Formative fictions are not just aesthetic constructions;

they also shape how viewers imagine certain categories of people and their political horizons.

I am interested in the conditions of the production and circulation by which photographs become news images; these are critical to understanding their meaning and force.53 In fact, what makes news images particularly interesting as objects of study is that they are photographs that circulate as truths but can also accumulate value or jeopardize their credibility through their circulation. Unlike in the mid–nineteenth century, when the very word daguerreotype denoted an honest representation, today, at a time when digital image creation and editing tools are

widely available and used by many different populations outside the press, photographic technologies are not assumed to guarantee veracity. Rather, it is the appearance of a photograph in a news publication of note, or its distribution by a well-known wire service, or its having been taken by a veteran photographer who has been recognized for his journalistic integrity that lends a photograph authority. This is not to say that reputable news publications, wire services, and photographers never have difficulties upholding journalistic ethics. 54 (Think back to the example of Michael Finkel’s photograph.) Rather, the stakes are so high precisely because it is only by circulating through established circuits of news organizations that a digital photograph is conferred legitimacy. Photographs that become news images by circulating in journalistic institutions acquire truth value and become part of the practices of public worldmaking. These news images are formative fictions because they not only illustrate the world as it is but also powerfully influence political possibilities within it and establish parameters for how future events are imaged.

THE TEMPORALITY OF NEWS IMAGES

Much has been written about the peculiar temporality of photographic technologies and their complex relationships to notions of the past, present, and future.55 The time of a photograph always exceeds the moment of its production. However, critical for the work of professional image brokers is the fact that photographs can be produced only now, yet their journalistic importance may very well not emerge until some time in the future. News images can accumulate force through repetition or circulation. They can accrue value because the context in which they are being reproduced has changed. The tremendous challenge facing image brokers as they make decisions today is accurately imagining themselves into the future and making sure that what the world will want to see tomorrow has been anticipated and captured visually today. As many individuals will remind us in the chapters to come, physically being there in time is critical to visual journalism. Image brokers need to ensure not only that they have covered the here and now, but that they will also have covered the futurepast.

News images move differently than other elements of journalism. When a photo editor at a wire service in Hong Kong validates an image, it can be pushed out to subscribers globally and used in publications from Argentina to Zimbabwe, with accompanying captions in dozens

of different languages that can vary significantly. A photo agent might sell a freelancer’s photographs to be published alongside articles on a variety of topics in a range of publications. Or a visual content provider will regularly sell historical images, highlighting the fact that news images can have complex temporalities. It is the visuality of news images that shapes the work of image brokers. This work happens in time, and time is often of the essence. In the chapters to come, we will encounter many moments when speed is critical and a key element in why one photograph circulates and another doesn’t. Therefore, the pace of work is quick. Until very recently, the time it took to move a photograph from one part of the world to another, whether by plane or over telephone wires, was a key factor in determining what kind of a news image it could become and the types of news it might visualize. It is only since the digital circulation of photographs that their transmission is, at least potentially, instantaneous.

These temporal peculiarities of news images pose a methodological challenge to any researcher attempting to study the force of photographs, for it is hard to predict when a particular image might become formative, let alone trying to find ways to observe its influence.56 Yet because image brokers need to plan for the futurepast, their decision processes often involve explicitly anticipating how a photograph might accrue value in the future. Which is to say, I didn’t ask people which images they thought had been important but instead listened to how they imagined a photograph might become significant in the future. My fieldwork was shaped around sites where image brokers regularly made and remade decisions against the background of an uncertain future. Importantly, I was able to find sites where image brokers had to verbalize the rationale for their decisions to others. Therefore, at the nodal points of photojournalism where I worked, brokers’ communicating their decisions and selections during the brokering of news images rendered acts of imagination observable to an anthropologist.57 This also allowed me to study image brokering in real time and within the intense time pressures of the newsroom rather than relying on retrospective interviews. This was particularly important as I studied image brokers trying to visualize a war that everyone said would soon be over before it began and yet continues in many ways as this book goes to print over a decade later. Image Brokers is a study of visual worldmaking at a particularly tumultuous time in newsrooms and the world beyond them.

AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF WORLDMAKING

I was drawn to international photojournalism partly because I entered the discipline of anthropology at the cusp of the twenty-first century, a moment when much intellectual energy was focused on investigating emerging forms of globalization. Photojournalism provided the opportunity to study an industry that had always been built on global interconnections. Moreover, I was interested in systems of description—such as journalism, photography, and the discipline of anthropology—that provide views of the world and make the world knowable.58 No doubt part of this interest stemmed from my daily consumption of news at a time when geographies that had seem bounded and discrete were becoming visibly porous—most dramatically perhaps with the 1989 tearing down of the wall in Berlin. It was also a time when there was much discussion of globalization and transnational flows, as well as migration.

By the time I began my training, anthropologists had for some time been critiquing the reductionist approach of mapping certain cultures onto bounded places inhabited by essentialized peoples.59 Many anthropologists, influenced by critical work in the field of geography, turned to space as a juncture of analysis hitherto more or less taken for granted.60 In other words, when anthropologists designed projects, the typical question asked had always been, and to some extent remains, “Where will you do this research?”—presuming that the answer to the question “Would a particular place be the best way to organize research on this particular problem?” is always yes. Yet this was a time of significant movements—of people, goods, and capital—and anthropologists were grappling with how best to do research at different scales in a world in flux. Because ethnographic fieldwork is cultural anthropology’s primary method, shifting how the discipline thought of objects of study also meant reevaluating the changing contours of the “field” in which anthropological investigation was conducted and the political stakes in the boundaries used to delimit field sites. The power relations inherent in anthropological research that had been discussed in relation to the politics of representation were also discussed in relation to conceptually and practically locating fieldwork itself. Anthropologists Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson argued for foregrounding “the spatial distribution of hierarchical power relations . . . to better understand the processes whereby a space achieves a distinctive identity as a place.”61 They predicted that an anthropology that no longer took for granted

that its objects of study were anchored in space would need “to pay particular attention to the way spaces and places are made, imagined, contested, and enforced.”62 Studying the practices of image brokers and networks traveled by news images seemed one way to answer the challenge raised by Gupta and Ferguson. After all, news images produce knowledge about specific places and have the potential to circulate widely.

Gupta and Ferguson mentioned mass media as “the clearest challenge to orthodox notions of culture”—the traditional assumed isomorphism of culture, territory, and a people—and the following years did see greater attention to ethnographies of media as exemplified by the 2002 publication of two important anthologies, The Anthropology of Media and Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain.63 Yet there was still little in the way of anthropological work on mass-media representations responsible for global-scale place-making. Anthropological research on news and journalism was still relatively novel.64 Today, anthropologists are certainly more critical of place as a stable selfexplanatory concept, but few have taken on place-making itself as a primary object of analysis. How certain places get identified as violent, repressed, exotic while others are perceived as peaceful, democratic, or belonging to the heartland remains an important question for the discipline and is relevant to those interested not just in journalism but also in international politics, humanitarian aid, and tourism—to name just a few domains in which how places are made is directly linked to what types of resources and people circulate through them. We might think of this as an anthropology of worldmaking at both global and more local scales.

Ferguson cautions us against becoming too enamored of novelty and moving too quickly to adapt new methodological approaches to new objects of study. Instead, he suggests we think not of objects of study but rather of relations as constitutive of objects or of objects as a set of practices. Ferguson’s own example of this is his book of essays that addresses “Africa” not as a vast empirical territory, historical civilization, or culture region, but rather as a category “through which a world is structured.”65 Or, as he puts it eloquently elsewhere, “to grasp the work that is done by this category ‘Africa,’ we must understand it as a position within an encompassing set of relations—what I have called a ‘place-inthe-world.’ ”66 My own work on image brokers is precisely about how such “places in the world” come to exist, partly through the production and circulation of images of certain places that get validated as real. It is

not merely that representations feed preconceptions, which in turn shape social realities, but that when images of “Africa” appear in a journalistic context and are captioned as such, they endorse “Africa” as a category that really exists in the world and reify certain sets of relations while making others seem implausible or less significant.

Image Brokers is an attempt to understand the mechanics, infrastructures, and ideologies of worldmaking by which categories such as “Africa” and “the Middle East,” “refugee camps” and “the Muslim world,” are constructed, validated, and circulated. Ferguson defines the world as “a more encompassing categorical system within which countries and geographical regions have their ‘places,’ with ‘place’ understood as both a location in space and a rank in a system of social categories (as in the expression ‘knowing your place’).”67 Photojournalism, then, is a form of worldmaking that involves making the places (in both senses of the term) of various categories of people visible.

A MATERIALIST ACCOUNT OF REPRESENTATION

In the course of designing this research I benefited from the intellectually rigorous conversations that accompany moments of disciplinary turmoil not only in anthropology but also among scholars of visual art and film. While some anthropologists were grappling with how to move the discipline from one that studied cultures in place to one that could investigate cultures of place making, art historians and film scholars were trying to take a more cultural approach to studying visual objects and practices. This book was written during a time when there was a flurry of name changes in academic departments that had hitherto been called “Art History” or “Film Studies” as many scholars debated concepts like visual studies and visual culture. All of which is to say that I found myself in the sometimes terrifying but also tremendously liberating position of studying the upheaval of the photojournalism industry from academic fields that were themselves in transition. Hence, from the beginning this research not only was influenced by interdisciplinary scholarship but also benefited from heated debates about shifting methodologies, “indisciplined” scholarship, and new objects of study both in anthropology and in visual fields.68

In fact, once I had decided to study practices of visualizing world news through the brokering of news images, the most concrete methodological advice I found was in art historian John Tagg’s call for a materialist account of representation:

Another random document with no related content on Scribd: