America Ferrera

MY NAME IS AMERICA, and at nine years old, I hate my name. Not because I hate my country. No! In fact, at nine years old I love my country! When the national anthem plays, I cry into my Dodger Dog thinking about how lucky I am to live in the only nation in the world where someone like me will grow up to be the �rst girl to play for the Dodgers. I do hate the Pledge of Allegiance though, not because I don’t believe in it. I believe every word of it, especially the “liberty and justice for all” part. I believe the Pledge of Allegiance to my bones. And at nine years old I feel honored, self-righteous, and quite smug that I was smart enough to be born in the one country in the whole world that stands for the things my little heart knows to be true: we are all the same and deserve an equal shot at life, liberty, and a place on the Dodgers’ batting lineup. I hate the Pledge of Allegiance because for as long as I can remember there is always at least one smart-ass in class who turns to face me with his hand over his heart to recite it, you know, ’cause my name is America.

The �rst day of every school year is always hell. Teachers always make a big deal of my name in front of the whole class. They either think it’s a typo and want to know what my real name is, or they want to know how to pronounce it (ridiculous, I know), and they always follow up with “America? You mean, like the country?”

“Yes, like the country,” I say, with my eyes on my desk and my skin burning hot.

This is how I come to hate American History. Not because I don’t love saying “the battle of Ticonderoga” (obviously, I do). But because no teacher has ever been more excited to meet a student named America than my �rst American History teacher.

He has been waiting all day to meet me, and so to commemorate this moment he wheels me around the classroom on his fancy teacher’s chair, belting “God Bless America” while a small part of me dies inside.

His face reminds me of Eeyore’s when I say, “Actually, I like to go by my middle name, Georgina, so could you please make a note of it on the rosterpaper-thingy? Thanks.” When he has the gall to ask me why, I say something like “It’s just easier,” instead of what I really want to say, which is “Because people like you make my name unbearably embarrassing! And another thing, I’m not actually named after the United States of America! I’m named after my mother, who was born and raised in Honduras. That’s in Central America, in case you ’ ve never heard of it, also part of the Americas. And if you must know, she was born on an obscure holiday called Día de Las Américas, which not even people in Honduras know that much about, but my grandfather was a librarian and knew weird shit like that. This is a holiday that celebrates all the Americas—South, Central, and North, not just the United States of. So, my name has nothing to do with amber waves of grain, purple mountains, the US �ag, or your very narrow de�nition of the word. It’s my mother’s name and a word that also relates to other countries, like the one my parents come from. So please refrain from limiting the meaning of my name, erasing my family’s history, and making me the least popular kid in class all in one fell swoop. Just call me Georgina, please?” I don’t say any of this, to anyone. Ever. It would be impolite, or worse, unpatriotic. And as I said before, I love my country in the most unironic and earnest way anyone can love anything.

I know just how lucky I am to be an American because every time I complain about too much homework my mother reminds me that in Honduras I’d be working to help support the family, so I’d better thank my lucky stars that she sacri�ced everything she had so that my malcriadaI self and my �ve siblings could one day have too much homework. It’s a perspective that has me embracing Little League baseball, the Fourth of July, and ABC’s TGIF lineup of

wholesome American family comedies with more fervor than most. I feel more American than Balki Bartokomous, the Winslows, and the Tanners combined, and I believe that one day I will grow up to look like Aunt Becky from Full House and then Frank Sinatra will ask me to rerecord “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” as a duet with him because I know all the words better than my siblings.

So I let it slide when people respond to my name with “Wow, your parents must be very patriotic. Where are they ACTUALLY from?” This is a refrain I hear often and one that will take me a couple of decades to unpack for all its implications and assumptions. I learn to go along with the casting of my parents as the poor immigrants yearning to breathe free, who made it to the promised land and decided to name their American daughter after the soil that would ful�ll all their dreams. After all, it is a beautiful and endearing tale. Only later do I learn to bristle and push back against this incomplete narrative. A narrative which manages to erase my parents’ history, true experience, and claim to the name America long before they had a US-born child. Never mind that they’d already had a US-born child before me and named her Jennifer. Which is both a much more American name than mine and one I would kill to have on the �rst day of every school year.

But I am nine and I do not think too much about narratives and my parents’ erased history. I think about my friends and getting to go over to their houses, where we play their brand-new Mall Madness board game and search Disney movies for the secret sex images you can see if you know where to pause the VHS. I think about how cool it would be if my mom ever let me actually sleep over at a friend’s house and how that will never happen because she’s convinced all sleepovers end in murder and sexual assault. I think about how cool it would be if my friend was allowed to sleep over at my house and how that will never happen because her parents, who are also immigrants, happen to agree with my mom about the murder and sexual assault thing. I think about how when I’m in junior high and look more like Aunt Becky I will have a locker and decorate it with mirrors and magazine cutouts like all the kids on Saved By the Bell. I think about how I will grow up to be a professional baseball player, actress, civil rights lawyer, and veterinarian who will let her kids go to sleepovers. And I think about boys. Well, I think about one boy. A lot.

Aside from having a challenging name, I feel just like all my friends. Even all the things that make my home life di�erent from my friends’ home lives seem to unify our experience. Sure, my parents speak Spanish at home, but Grace’s parents speak Chinese, and Muhammad’s parents speak another distinct language that I can’t name, and Brianne’s Filipino parents speak something that sounds a little like Spanish but isn’t. My favorite part of going over to my friends’ houses is hearing their parents yell at them in di�erent languages and eating whatever their family considers an after-school snack. Brianne and I consume an alarming amount of white rice soaked in soy sauce while we stretch in the dark, listening to her mom ’ s Mariah Carey album.

Speaking Spanish at home, my mom ’ s Saturday-morning-salsa-dance party in the kitchen, and eating tamales alongside apple pie at Christmas do not in any way seem at odds with my American identity. In fact, having parents with deep ties to another country and culture feels part and parcel of being an American. I am nine and I truly belong. By the time I reach ten, this all begins to change.

The �rst person to make me feel like a stranger in a strange land is the �rst boy I ever love. I am six years old when I fall in love with Sam Spencer.II And the full agony of loving him is bursting out of my tiny bones and pulsing through my tiny veins. He has very silky, soft brown hair that is almost entirely short except for the rat’s tail that dangles down the nape of his neck. I sit behind Sam on the magic carpet at reading time, and I try to be sneaky about braiding his rat’s tail. Whether we are making pizza bagels or building castles in the sandbox, all my little six-year-old mind can focus on during Ms. Wildestein’s kindergarten class is braiding Sam’s hair, talking to Sam, and sitting near Sam. With every passing year, new boys and girls are added to our class but my heart remains fully devoted to worshipping at the altar of Sam Spencer. By the time we are in third grade, I am aware that other girls also think Sam is one of the cute boys, but I am secure in the deep foundation we have built starting back in kindergarten. When I sit next to him at lunch, he does not tell me to go away, and that has to mean something. I don’t need to tell him I love him or need him to declare his love for me. I just need to sit next to him on the reading carpet and stand as close to him in the lunch line as possible. I’m ful�lled with making him laugh from across the classroom by taking my long brown hair and turning it into a mustache and

beard on my face. I think of him as mine, because my heart says he is. What more proof do I need? I never imagine that our relationship will ever need to be spoken about.

One day, we, the students of Ms. Kalicheck’s third-grade class, are lined up after lunch. I am locking arms and sti�ing giggles with my girlfriends Jenna and Alison when Sam taps my shoulder. This is unusual. He is not often the initiator of our conversations. I turn to him very attentively and wait. He opens his mouth to say, “I like Jenna more than you. Do you want to know why?”

The masochist in me answers too quickly. “Why?”

He says, “Because she has blue eyes and lighter skin than you. ”

He turns around and rejoins his group of boys. I stand there frozen. Ice-cold. Learning how fast a heart beats the �rst time it is crushed by love, how quietly skin crawls the �rst time its color is mentioned, how wet eyes become when they realize for the �rst time that they are, in fact, not blue, like Jenna’s, the color Sam likes better. I stand there wishing to return to the moment before Sam taps me on the shoulder, before I learn that it would be better to not look like me, at least if you want the �rst and only boy you ’ ve ever loved to love you back. Which I do.

Shortly after, I learn that it is also better not to look like me if you don’t want to be singled out at school and questioned about your parents’ immigration status.

It is 1994, and California just voted in favor of Proposition 187—an initiative to deny undocumented immigrants and their children public services, including access to public education for kindergarten through university. There is fear inside the immigrant community that their children will be harassed and questioned in their schools.

I am in third grade and do not know or understand any of this. Nonetheless, my mother pulls me aside one day when she is dropping me o� at school and says, “You are American. You were born in this country. If anyone asks you questions, you don’t need to feel ashamed or embarrassed. You’ve done nothing wrong. ”

I am so confused, but I take my mom ’ s advice and feel the need to spread it. I mention to some of my friends that people might be asking them questions and that they shouldn’t be afraid, they’ve done nothing wrong. They stare blankly at

me and then go about their hopscotch. None of my friends seem to know what I’m talking about. I have the sneaking suspicion that their parents did not pull them aside to have the same talk. While I am grilling some more friends on the playground about whether they’ve been questioned about being American, a big kid I don’t know interrupts me to say, “They don’t care about us. It’s just Americans like you. ” My mind short-circuits. Americans like me? What does that mean? I wasn’t aware there were di�erent kinds of Americans. American is American is American. All created equal. Liberty and justice for all. I manage to say something to the big kid, like, “Oh,” and I never talk about it at school again. I never talk about it at home either. But I do spend some time wondering what the big kid means by “Americans like you. ”

Is it about my name? Is it the salsa music at home? Maybe this has something to do with my skin and my non-blue eyes again. That’s ridiculous, we don’t separate Americans by the color of their eyes. Do we? Are there di�erent words for di�erent kinds of Americans? Am I half American? Kind of American? Other American? I am nine years old, and suddenly I am wondering what do I call an American like me.

As I grew older, I got better at recognizing when someone was trying to tell me that I was not the norm and that I didn’t really belong in a given place, which seemed to be just about everywhere. The Latina clique would call me “that wannabe white girl who hangs out with drama kids and does lame Shakespeare competitions” to my face because they thought I didn’t understand Spanish. I let them believe that so I could keep eavesdropping. My AP English teacher would excuse my tardies because she assumed I was bused into the neighborhood like most of the other Latino kids. “Bus late again?” she would ask. I’d drop my eyes, take my seat quickly, and never really con�rm or deny. The truth was I lived a few blocks from school but hated waking up early. Her assumption that a kid who looked like me didn’t really belong in this neighborhood bought me a few extra hours of sleep a week, so I let that one slide.

I may have been a whitewashed gringa in Latino groups, but I was downright exotic to my white friends; especially to their parents, who were always treating

me like a rare and precious zoo animal. They’d ooh and aah at my mother’s courageous immigrant story, then wish out loud that my hardworking spirit would rub o� on their children. They particularly loved having me around when they needed something translated to their housekeepers or gardeners. Seeing such a smart and articulate brown girl was like seeing a dog talk. They were easily impressed.

Even at home I walked a �ne line between assimilating to American ways enough to make my mom proud, and adapting in ways that would disgrace and shame her. For instance, bringing home straight-A report cards was a good thing, but attending late-night coed study groups to achieve said A’s was shameful and likely to turn me into a drug-addicted, pregnant high school dropout. Decoding people’s expectations and then shape-shifting into the version of myself that pleased them the most became my superpower.

Shape-shifting was a useful skill to possess as an aspiring actress, but it didn’t stop people from labeling and categorizing me. In fact, when people found out that my dream was to become an actress, they made it their duty to remind me of who I was . . . and who I wasn’t.

Family members would say to me bluntly, the way families are prone to do, “Actresses don’t look like you. You’re brown, short, and chubby.” Classmates would say, “You have to know someone to catch a break, and you don’t have any connections to the industry.” Teachers, hoping they could steer me toward a more sensible career path, would simply ask, “What’s your backup plan?” But I wasn’t sensible, I was an American, damn it! An American who wholeheartedly believed what she’d been taught her entire life: that in America no dream is impossible, even if you are a short, chubby Latina girl with no money or connections! What was wrong with these people? Didn’t they know that in America fortune favored the dreamer willing to work hard? I mostly felt sorry for them and their lack of imagination, and went about working to make my dream come true.

I acted wherever anyone would let me—in school, the local community college, and free community theater programs. I spent one summer riding three buses to get from the Valley to Hollywood in order to play Fagan’s Boy #4 in a community theater production of Oliver! I babysat kids, looked after my

neighbors’ pet pig, and waitressed to pay for acting workshops. It was impossible to know which opportunity would open a door to my career, especially in LA, “where there are so many scams designed to take aspiring actors’ money, ” as my mom liked to warn me. But I threw myself and my hard-earned cash at every single opportunity that came my way. And to everyone ’ s surprise, including my own, a few doors started opening for me when I was still only sixteen years old.

To nobody’s surprise, except my own, Hollywood was not as ready for me as I imagined. I thought the hard part was getting through the door, and I was sure that as soon as Hollywood saw me in all my glory, passion, and optimism they’d roll out the red carpet and alert the press: America’s new sweetheart has arrived!

Somehow the boxes I resisted being shoved into during my childhood were even tighter and more su�ocating in Hollywood. The �rst audition I ever went on, the casting director asked me if I could “try to sound more Latina.”

“Ummmm . . . do you want me to do it in Spanish?” I asked.

“No, no, do it in English, just sound like you ’ re a Latina,” she clari�ed.

“But I am Latina, soooo isn’t this what a Latina sounds like?” I asked.

“Okay, never mind, honey. Thanks for coming in, byeeee,” she said as she waved me toward the door. It took me far too long to understand she wanted me to speak in broken English. And instead of being sad that I didn’t get the part, I was angry that she thought sounding Latina meant not speaking English well.

Even after I’d had some great successes with Gotta Kick It Up! and Real Women Have Curves, two movies that allowed me to play Latina characters who were not just broad stereotypes, I was constantly coming up against people who thought it was silly for me to expect to play a dynamic and complex Latina who was the main character in her own story. Even some of the people I paid to represent me did not believe in my vision for my career. When I was eighteen I told my manager that I was sick of going out for the role of Pregnant Chola #2 or the sassy Latina sidekick. I wanted him to send me out for roles that were grounded and well written. I wanted to play characters who were everyday people with relatable hopes and dreams. His response was “Someone needs to tell that girl she has unrealistic expectations of what she can accomplish in this industry.” And the saddest part was that he wasn’t wrong. I mean, I �red him, but he wasn’t wrong.

After hustling for years to break down doors and working my hardest to prove my talent and grit, I had to admit that the stories I wanted to tell and the characters I wanted to play were virtually invisible from our cultural narrative. I have been supremely lucky to get the opportunities to play some wonderful, authentic, and deep characters, but if I look around at the vast image being painted about the American experience, I see that there are so many of us missing from the picture. Our experiences, our humor, our dramas, our hopes, our dreams, and our families are almost nonexistent in the stories that surround us. And while growing up that way might turn us into badass-Jedi-mastertranslators-of-culture who are able to imagine ourselves as heroes, villains, or ThunderCats, we deserve to be truly re�ected in the world around us.

For seventeen years, I’ve had a front-row seat to the impact that representation has on people’s lives. I’ve met people who’ve told me that Real Women Have Curves was the �rst time they ever saw themselves on-screen, and that my character, Ana, inspired them to pursue college, or to stop hating their bodies, or to mend broken relationships with a parent.

I’ve heard from countless young people who came out to their parents while watching Ugly Betty, and young girls who decided they could, in fact, become writers because Betty was a writer.

And, most common, I hear from all kinds of people that they gain con�dence and self-esteem when they see themselves in the culture—a brown girl, a braceface, an aspiring journalist, an underdog, an undocumented father, a gay teen accepted by his family, a gay adult rejected by his mother, a store clerk getting through the day with dignity and a sense of humor, a sisterhood of girls who love and support one another, and, yes, share magical pants—simple portrayals that say in resounding ways, you are here, you are seen, your experience matters.

I believe that culture shapes identity and de�nes possibility; that it teaches us who we are, what to believe, and how to dream. We should all be able to look at the world around us and see a re�ection of our true lived experiences. Until then, the American story will never be complete.

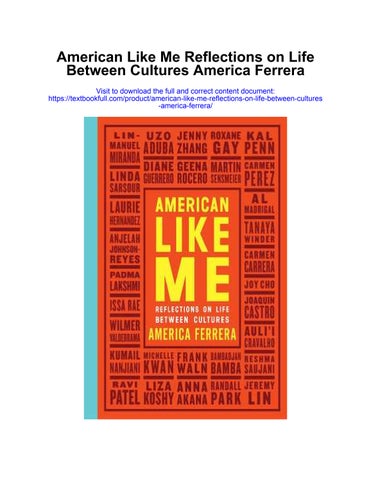

This compilation of personal stories, written by people I deeply admire and fangirl out about on the regular, is my best answer to my nine-year-old self. My plan is to �nd a time machine and plop this book in her hands at the very

moment she �rst thinks, What do I call an American like me? I’ll tell her to read these stories and to know that she is not alone in her search for identity. That her feelings of being too much of this, or not enough of that, are shared by so many other creative, talented, vibrant, hardworking young people who will all grow up to transcend labels and become awesome people who do kick-ass things like win Olympic medals, and run for o�ce, and write musicals, and make history that changes the country and the world. And it won’t matter what people called them, because the missing pieces of the American narrative will be �lled in and rewritten and rede�ned by Americans like her, Americans like you. Americans like me.

I spoiled

II. Name changed to avoid awkward Facebook interactions.

Reshma Saujani is the founder and CEO of Girls Who Code, ran for Congress in 2010 as the �rst Indian-American woman to do so, and is the proud daughter of refugees. She is the author of Women Who Don’t Wait in Line and the New York Times bestseller Girls Who Code: Learn to Code and Change the World.

Reshma Saujani

WHEN I ORDER THE grande chai latte at Starbucks, I almost always lie. It’s a white lie, as innocent and airy as the foam on top of the drink, and it’s been carefully constructed to make all our lives easier.

“Can I get your name, ma ’am?”

“Maya,” I say e�ciently, pulling out my credit card.

The barista is a teenager with lavender-streaked hair and eyeliner so exquisite and precise, I wish for a �eeting moment I had chosen a more mysterious name, one that might impress her, as exactly nothing seems to do. She scrawls Maya on the side of the cup with her Sharpie and I think about Maya. The real Maya whose name I stole for my Starbucks order.

She happens to be my niece. She’s a beautiful �fteen-year-old who has no idea I borrow her name regularly. But I do this because the baristas can spell and pronounce it correctly every single time.

“Reshma, you won’t �nd your name there,” my mother tells me.

R-E-S-H-M-A. I whirl the squeaky cylinder kiosk around and around, searching for my name in the rows and rows of key chains. They are pink, pale blue, neon green, and black. Printed with gold lettering on each is what seems like every possible name that could be granted to a ten-year-old girl shopping for school supplies at a suburban-Chicago Kmart in 1985:

RACHAEL, RACHEL, RACHELLE, RAINBOW, RAMONA, REBECCA‚ REGINA, RENE, RHIANNA, RHONDA, RITA,

ROBERTA, ROBIN, RORY, ROSANNE, ROSE, ROSEMARY, ROWENA, RUBY, RUTH . . .

The not-my-names dangle in front of me like shiny ornaments on a cruel Midwestern Christmas tree. Two di�erent spellings of Rachel are o�ered, and to me, a young girl with a surprising sense of justice, this seems fair. There are at least two Rachels in my class at school, but I have never met a Rory or a Rowena, so it doesn’t seem just that these names glitter past me on my search for Reshma. I am incredulous that somebody out there in America named their daughter Rainbow; enough somebodies, in fact, that each and every girl named Rainbow gets a key chain with her quirky, adorable name on it.

“In Bombay you would be able to �nd a Reshma key chain,” my mother tries to console me.

Reshma, it turns out, is like Rachel in India. It is as common and standard a name as they come half a world away. But here in the United States, it is more acceptable to name your daughter Rainbow. My mother is right. There is no Reshma printed in gold, jangling on a hook for me. I check the boy-name section, just in case, but I do not �nd myself there either.

At this moment in time, there is no useless plastic object that could mean more to me. Seeing my name re�ected on a cheap trinket would have changed my world. For years to come, I would grow used to this. I would never meet a Cabbage Patch doll with my name—though I did come across one named Rowena in my time. I never read a book about a brown-skinned girl named Reshma, and I never saw another mother wearing a sari and bindi in Kmart.

For a person like me who has run for public o�ce twice and worked on several political campaigns, it is not advisable to admit to lying. But my Starbucks lie is just the �rst of many harmless assimilations I have perpetrated in my life. I have cultivated several everyday methods for making my name roll o� someone else’s tongue. At times, I can be jaded about hearing my name butchered over and over again, but I am pragmatic enough to know that you might not have seen my name before, and you might stumble when you try to spell it or pronounce it.

I grew up in Schaumburg, Illinois, a suburb connected to Chicago by a major interstate that brings people there to shop at one of the largest malls in America or happily disappear into a cavernous, endless IKEA. Schaumburg is close to the airport and populated with hotels, golf courses, and restaurants like P.F. Chang’s, Outback Steakhouse, and Red Lobster. It wasn’t a terrible place to grow up, but for a young brown girl, it was terribly lonely.

Ironically, when you are the only one of your kind, it is di�cult to be authentic. You are unique. You don’t blend in. This should make it easier to be the real you. Because there’s no one like you. But, instead, this is isolating. You are so unique that they don’t make a key chain for you. You will never blend in. You can’t disappear into the crowd. I remember wanting to be white, wanting my key chain so I could unlock the secret to �tting in, having friends, and being happy. My life would be better, I thought, if only I had blond hair and ate at McDonald’s like everyone else. But Hindus don’t eat beef, so I was stuck with vegetable curry, which meant I was always scrubbing my hands and face. I was convinced my classmates could smell it on me (because they taunted me and told me all the time they could smell it on me). I brought white-girl food (bologna, cheese, and mustard on white bread) in my paper-bag lunches at school and kept my head down around Easter and Christmas. A lot of quiet e�ort went into ensuring that no one found out I didn’t pray to Jesus. White wasn’t necessarily perfect or better in my mind. But it was normal. It had a key chain, a presence, a home in Schaumburg, Illinois.

My parents came to Illinois from Uganda in 1972 after literally throwing a dart at a map of the United States to choose where to start over. The Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expelled them—and all other people of Indian descent—from the country. My parents were both born and raised in Africa. It was all they ever knew. They had engineering careers and a rich community of friends and family. And, suddenly, they were given ninety days to leave.

Before they threw the dart that landed on Illinois, they were denied access to several other countries. The United States was the only nation that would have them. My father immediately began looking for a job as a mechanical engineer and was promptly told by a recruiter that he should Americanize his name and lose the accent. My dad, Mukund, became Mike. My mother, Mrudula, became

Meena. And a few years later, when he was working in a factory and she was working at a cosmetics counter, Mike and Meena had me.

And named me Reshma.

“Why didn’t you guys give me a normal name?!” I remember asking this for the �rst time around the age of ten. I was reading Sweet Valley High books and contemplating how easily they could have made me an Elizabeth or a Jessica. Because even though my parents’ name changes may have helped them get jobs, it didn’t stop our house from getting regularly egged and TP’d by the kids at school. As we attempted to cover the spray-painted words dot head go home o� the side of our house, I couldn’t help but wonder if maybe they could change my name too.

I marveled at what it would feel like to wave your hand and transform everything. One day, Mukund was suddenly Mike. From that day forward his name was on a key chain. A person could simply authenticate himself as an American and enjoy the American-size horizon of possibilities that came with it. Why shouldn’t I blink my eyes and reopen them as a Rebecca?

True to cultural form (at least if you ’ re Indian), my parents didn’t talk about personal decisions, emotional hardships, or the numerous dilemmas of safety and identity they must have faced in their young adult lives. They were political refugees with young children, living in a town where they were almost the only Indians. This could not have been easy. More than once, we were told to go back to our own country—a country I was not connected to at all but for my name.

And yet, my parents didn’t push their culture on me. Of course I ate vegetarian with them in our house and accepted their paci�st ideals. But they never taught me their language. Reshma was my only connection to the �ne, exotic, colorful fabric of a country I didn’t understand. Even my parents grew up removed from India, the children of immigrants themselves, coming of age in Uganda, living as Indians away from India. Sometimes I pondered that they must have given me an Indian name out of loneliness. Maybe it was just nice to utter an Indian name every single day, to count one more Indian person living among them in Schaumburg.

Reshma, I have since learned, means silken; she who has silky skin, and I can’t help but wonder if Mike and Meena were aware of this de�nition. Have they

come to understand its irony like I have? Do they remember the moment the girl with the silky skin became the girl with the thick skin?

It was a schoolyard �ght and her name was something like Melissa. I have changed it to protect her privacy, but names are important, so I use this one as a substitute. Melissa and her friends often called me names and made fun of the color of my skin. It happened all the time. I became very good at using the middle school tactic of pretending to laugh and be in on the joke. I would ignore how much it hurt and allow them to make fun of me more. Be a good girl, like your parents taught you. Hindus are pacifists. Don’t fight back. Better to deny myself my anger. Easier to focus on my extreme desire to just be white. But when Melissa told me to meet her in the back of the school for a real �ght that day, an impulse awakened in me to �ght back.

Maybe my sudden chutzpah came from the fact that it was the last day of eighth grade. Summer had �nally arrived, and high school was looming. I could start over there. This was my opportunity to stop hiding from them—and myself. To stop wishing to be white, and to start being me.

I arrived at the designated spot behind the school and was met by Melissa, a tennis racket, and a plastic bag full of shaving cream. And also almost every member of the eighth-grade class. Before I could even set down my backpack, they were coming at me. Knuckles crashing into my eye, I blacked out almost immediately.

A few days later, I walked across the stage in my eighth-grade graduation ceremony sporting a black eye and a new attitude. I wasn’t going to try to be white anymore. I was brown. And for the �rst time, I was ready to embrace it.

When I started my freshman year at Schaumburg High School a few months later, I volunteered to start a diversity club. I knew I was going to have to be an active member of the community to defend myself—to find myself. So I created Schaumburg High’s PRISM, the Prejudice Reduction Interested Students Movement. Names matter, and I wasn’t kidding around when I came up with that one. My con�dence was still a little shaky, and I was still struggling to �nd a way to be proud of what made me di�erent (or “diverse,” as the kind, liberal, white teachers in suburban Chicago liked to call it then). Yet I somehow knew

that activism was my avenue to �ghting prejudice and �nding a way to be brave about being me.

One of PRISM’s �rst big events was an assembly where the students of color stood onstage in front of the whole school while the rest of the mostly white students sat in the audience, invited to ask us questions. This was purely my idea. To make a zoo animal of myself and all the other “diverse” kids. There we stood in front of the microphones, Schaumburg High’s Indian, black, Latino, and Asian kids, ready to take questions about our identities, our parents’ cultures, our souls. Looking back, it seems like this could have been a traumatizing event for a ninth grader, but it was my way of stepping out. I was determined to open a dialogue. I was ready to stand in front of a very white room and shine a spotlight on my very brown face. The questions poured in like bullets from a �ring squad:

“Were you born with a dot on your head?”

“Are there terrorists in your home country?”

“Are you an American citizen?”

“How many Hindu gods are there?”

“Do you bathe in curry?”

Despite the vaguely racist questioning, I was proud of what I had organized. I wanted to “reduce prejudice,” and the sometimes-insensitive curiosity hurled at me that day was a starting place. And it changed my thinking. It positioned me as the Indian girl who wasn’t ashamed. In fact, it actually created a framework for how I discussed my culture with white people for the rest of my life (“Ask me questions,” I still tell them). And for the �rst time, I was publicly expressing some pride in who I was. And I managed to assemble an entire community of fellow kids without key chains.

I was beginning to learn that bravery is like a muscle, and once you �ex it, you can’t stop. And being authentic requires a lot of bravery. We closed out the PRISM assembly doing a step dance to Aretha Franklin on the loudspeakers, singing the lyrics “Pride, a deeper love! Pride, a deeper love!” This dance was fundamental to everything in my future. I was no longer going through the motions of trying to �t in. I was literally parading my true self right there for all

the white kids to see. Pride and bravery were magical feelings, and I wanted more of them.

Years later, when I ran for political o�ce for the �rst time, I was exercising my bravery again. I had enjoyed several years of a lucrative career at a Wall Street law �rm but longed to make my life more about helping to build communities and improving the future of this country. I wanted to push myself. And much like barging into Schaumburg High to start a diversity club, the idea of running for public o�ce felt good—like I was �exing that bravery muscle again. So I bravely quit my job. I bravely ran for Congress. And I bravely lost by a landslide.

But I did it authentically, as myself, as Reshma. In the early stages of campaigning, I was told to change my name to Rita, given the advice that people are more likely to vote for you if they can pronounce your name. But my bravery had brought me this far. I wasn’t going to stop now. I could never turn my back on Reshma to become a Key-Chain Rita. And losing authentically allowed me to articulate something I was passionate about. I wanted to �nd a way to address the fact that American girls are often raised to value perfection over bravery. They want to be Sweet Valley Jessicas instead of Schaumburg Reshmas. So I ran my campaign on a platform of bringing computer science into every classroom and making sure girls were given equal access to learning coding. I focused on this because the process of learning to code—building something from the ground up, using trial and error, failing and starting over—allows you to see for yourself that perfection is pretty pointless. And bravery leads to wonderful things.

I should know. After the election loss, I had the gall to start a national nonpro�t called Girls Who Code, and I don’t even know how to code, myself.

But thanks to my childhood, growing up with two very brave immigrants as parents—who just like me were children of immigrants in Uganda—I now know it is more important than ever to be brave and proud of my identity, to own my role in changing the world, one election loss at a time.

Yes, I did run for o�ce again a few years later. And yes, I lost again. But bravery is contagious.

On election day, I was running around in the rain shaking voters’ hands up to the very last minute. I met a woman—I did not catch her name—who was rushing to the polls. As she passed by me, I smiled and said, “Who are you voting for today?”

She hesitated, �ustered but kind. Embarrassed she couldn’t pronounce it correctly, she fumbled out an uhh as she frantically pulled one of my �iers from her bag.

“This woman, ” she said as she pointed at my name on the piece of paper.

Even though she needed a cheat sheet to remember who she was voting for, I couldn’t help but swell with pride that I had an Indian name. I couldn’t help but think of my parents. When they chose to name me Reshma, did they dream of a world where it would be unthinkable to go by Rita instead? I had spent years assimilating as a child, and for the �rst time, I thought I knew why my parents named me Reshma.

Maybe they didn’t want me to blend in as much as I thought. They blended in so I wouldn’t have to. They paid the ultimate price for my authenticity. They gave up their community, their careers, their language, their own names. These were the steep taxes they paid to make a better life for me. Assimilating in the ways my parents did can invite accusations. Changing your name and hiding your accent could be seen as passive or fearful gestures. But my parents’ immigrant experience reveals the great reserves of bravery and pride they had in order to survive in a new country with no familiar community of support. I think my parents are the bravest people I know. They traded in their names for the freedom and privilege I experience every day. Because of them, I have the platform to be brave. They built the stage I stood on at the PRISM assembly. They laid the groundwork for a little girl named Reshma to grow up and become the �rst Indian-American woman to run for Congress. They changed their names so I wouldn’t have to.

And while I plastered campaign signs all over my district in New York with bold block letters reading RESHMA, they were still signing “Mike” and “Meena” at the bottom of birthday cards and letters. Even though they had initially Americanized their names purely for their résumés, Mike and Meena eventually

took a very strong hold—as names have a tendency to do. And now even their closest friends and family members call them by their American names. My husband, Nihal, who is of Indian descent himself, calls them Mike and Meena.

Sometimes Nihal and I watch Bollywood movies with our two-year-old son, Shaan, in the hopes he will learn some of the language. I want him to delight in the music and color, and somehow absorb the culture I did not grow up in. He watches with bright wide eyes, and I consider how he will never see my parents as the struggling refugees walking the �ne line of sacri�ce and assimilation. To Shaan, they are not Mike and Meena. They are the people with loving arms who bring him red lollipops and soccer balls, who light up his whole face every time he sees them.

To Shaan, Mike and Meena are Granddad and Nana.

But to me, they will always be the people who made it possible for a girl named Reshma to grow up in America and name her son Shaan—the Sanskrit word for pride.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

107. Año 1540. El Magnífico Caballero P��� M���� (1500-1550) nació en Sevilla, donde aprendió latín; en Salamanca, leyes. Esgrimía diestramente y se carteaba con Vives en latín elegante. Fueron muchas veces premiados sus versos, agudos y dulces. Trató mucho á don Fernando Colón, á don Baltasar del Río, obispo de Escalas, que despertó en Sevilla las buenas letras. Llamábanle el astrólogo por su afición á las matemáticas y astrología. Sobrevínole una gran enfermedad de la cabeza que le duró toda su vida. Fué alcalde de la Hermandad del número de los hijodalgos, contador de S. M. en la Casa de la Contratación, y veinticuatro. Comía poco y no dormía más de cuatro horas. Nombróle Carlos V su cronista (1548). Murió de cincuenta años, siendo enterrado en Santa Marina. Celebróle con un epitafio Arias Montano, que le tuvo en su mocedad por padre y maestro. Fué uno de los escritores más celebrados en su tiempo, y aun hoy en día de los más eruditos y sabrosos, de estilo sencillo y claro, apacible y castizo. Escribió la Silva de varia lección, Sevilla, 1540, obra que declara muchos puntos de erudición, á la manera de las Noches Áticas, de Aulo Gelio, muy celebrada y traducida en varias lenguas. Historia imperial y cesárea, esto es, de Carlos V, Sevilla, 1544. Colloquios ó diálogos, Sevilla, 1547. Laus Asini: ad instar Luciani et Apuleii, Sevilla, 1547.

Parenesis ó exhortacion á la virtud, de Isócrates, traducida de la versión latina de Rodolfo Agrícola. Fragmentos y Memorias, que quedaron en la biblioteca de Gonzalo Argote de Molina.

108. La biografía y retrato véase en F.co Pacheco y M. Pelayo, Ilustr. esp. Rodrigo Caro, en los Claros varones, dice que nació en 1500, y que le consultaban pilotos y mareantes, que le escribieron Ginés de Sepúlveda y Erasmo (Epíst , l 25, 26, á su hermano Cristóbal, y á él la 27). Fué alabado de los más famosos escritores. Al fin del Ms. colombino de la Hist. de Carlos V se lee, de puño y letra de Colmenares: "Murió Pero Mexía, autor desta historia, año de 1551... Fué infelicidad de este príncipe y de la nación española que no la acabase, para que no hubiera caído en manos de fray Prudencio de Sandoval, ya que el señor Rey D. Felipe II no advirtió en honor de su padre encargarla á don Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, con que tuviéramos la mejor historia por el asunto y por el escritor, que acaso hubiera en el mundo, fuera de las sagradas...". Rosell: "Mexía, como historiador, fuera de las lisonjas que prodiga al César y que le hace llamar siervos á los vasallos, adolece de cierto amaneramiento en la elaboración de los períodos y en el uso de los sinónimos, con que, sin duda, pretende esclarecer más las ideas; pero es buen hablista, escritor claro y vigoroso; hábil en la manera de disponer su asunto. No deja de ser feliz en la elección de las palabras y no menos en el empleo de las metáforas y comparaciones, como al referir el incendio de Medina... Algunas veces incurre en afectación, y otras, por evitar este defecto, se arrastra con demasiada languidez; pero no debe olvidarse que sus largos padecimientos necesariamente habían de debilitar su espíritu y que no habiéndole dejado la muerte terminar su obra, tampoco le daría tiempo para perfeccionarla".

E� D���� C�������� P���� M����.

(Pacheco. Libro de Retratos)

Silva de varia lección, Sevilla, 1540, 1542; Zaragoza, 1542; Amberes, 1544; Sevilla, 1547; Zaragoza, 1547; Venecia, 1550 (en ital.); Valladolid, 1551; París, 1552; Venecia, 1553; Zaragoza, 1554, con 5.ª y 6.ª partes anónimas; Amberes, 1555; Lyon, 1556 (dos edic., cast. é ital.), 1557, 1558, 1561 y 1563; Sevilla, 1563; Amberes, 1564; Londres, 1566-1569 (en ingl.); Sevilla, 1570; Lérida, 1572; Sevilla, 1587; Madrid, 1602; Amberes, 1604; Madrid, 1643, 1662, 1673, con la traducción de la Parenesis Mambrini da Jabrino tradujo al italiano las 4 partes, Lyon, 1556. Jerónimo Giglio añadió una continuación, Seconda silva, Venecia, 1573. Reprodújose, en Venecia, Silva rinovata di varia lectione di Francesco Sansovino, Mambrino Rosseo et Bartholomeo Dionigi, 1616. Según Andrés Escoto, se tradujo al francés y se le añadieron varios libros. Antonio Verdier, autor de la Bibliotheca Gallica, cita una traducción de Lyon, 1576, después dos veces reimpresa. En 1643 publicó Claudio Grugnet una versión de la Silva (Rathomayi, por Jorge Loysellet), que comprende además tres diálogos de nuestro autor. Hay ediciones francesas de la Silva de 1570, 1577 y 1580 y otras muchas, según Verdier. Nic. Antonio dice haber visto una obra francesa titulada Leçons diverses de Guyon de la Nauche suivant celles de P. Messia et de du Verdier, 2 vols., Lyon, 1610. Se hicieron dos traducciones al inglés y una al alemán (Ticknor). Historia imperial y cesárea, Sevilla, 1544, 1545, 1547; Basilea, 1547 (en latín); Amberes, 1552; Sevilla, 1554; Amberes, 1561; Venecia, 1561; Sevilla, 1564; Amberes, 1578. Tradújola al italiano Alfonso de Ulloa y Luis Dolce. Coloquios ó diálogos, Sevilla, 1547; Amberes, 1547; Zaragoza, 1547; Sevilla, 1548, 1551; Venecia, 1557 (en ital.); Amberes, 1561; Sevilla, 1562; Venecia, 1565; Sevilla, 1570, 1580, 1598; Madrid, 1767, con la Parenesis. Laus Asini: ad instar Luciani et Apuleii, Sevilla, 1547; Amberes, 1547, 1566; Sevilla, 1570, 1576. Hay versión francesa anónima é italiana de Alfonso de Ulloa: Raggionamenti di Pietro Messia, Venecia, 1557, 1565, con la Filosofía de Juan de Xarava, traducida por el mismo Ulloa. Historia del Emperador Carlos V, empezada tres años antes de su muerte (1549) y dejada en el libro V: hay tres copias en la bibl. del Conde-

Duque de Olivares y otra que tenía Diego de Colmenares, hoy de la Bibl. Colombina. Sandoval se aprovechó mucho de ella sin citarla. En 1852 Cayetano Rosell publicó lo tocante á las Comunidades (que forma el l. 2 de la Hist. de Carlos V) en la Bibl. de Autor. Esp., ts. XXI y XXVIII. Pero Mexía, Relación de las comunidades de Castilla, Bibl. de Aut. Esp., t. XXI. Consúltense: M. Menéndez y Pelayo: El magnífico Caballero P. M., en La Ilustración Española y Americana (1876), páginas 75, 76, 123, 126. F.co Pacheco, Libro de Retratos, y copiado por L. Villanueva, en Semanario Pintoresco Español de 1844, págs. 405, etc.

109. Año 1540 Comedia Fenisa, Sevilla, 1540, ó, como puso Moratín, Coloquio de Fenisa, y así se publicó en Valladolid, 1588, reimpresa por Gallardo en El Criticón, núm. VII, Madrid, 1859; Salamanca, 1625 (Bibl. Nac.), reimpresa por Bonilla en la Revue Hispanique, 1912. "Llama extraordinariamente la atención, dice Bonilla, que Moratín dijese de esta Comedia que "está escrita... con poca invención y ninguna elegancia; no merece particular examen". Es, por el contrario, una de las piezas más lindas del viejo repertorio, y se distingue por la fluidez de su versificación y por la delicadeza de su espíritu, aunque ciertamente la acción sea bien sencilla y breve. Así lo comprendió también el pueblo, y no se explicaría de otro modo que la obrita hubiese podido subsistir hasta bien entrado el siglo XVII, cuando la exuberante lozanía de Lope y sus continuadores había borrado casi por completo el recuerdo de las antiguas farsas". En el códice de la Bibl. Nac., Colección de autos sacramentales, loas y farsas del siglo ���, hay un Colloquio de Fenisa á lo divino (núm. 65) y otro de Fide ypsa (núm. 66), calcados sobre el anterior y conservando muchos versos del original. Dicha Colección fué publicada por L. Rouanet en la Bibliotheca Hispánica, ts. V, VI, VII y VIII.

Las preguntas que el emperador Adriano..., Burgos, 1540.—J���� �� B���������, natural de Santo Domingo de Silos, publicó Justino claríssimo abreviador de la historia general del famoso y excellente historiador Trogo Pompeyo, Alcalá, 1540; Amberes, 1542, 1586,

1599 Libro del Metamorphoseos y fábulas del excelente poeta y philósofo Ovidio (Salvá); 2.ª ed., Sevilla, 1550 (Salvá); Amberes, 1551, 1595; Madrid, 1622. Gaulana, comedia en coplas (Hern. Colón). H��� �� C���� publicó Las leyes de todos los reynos de Castilla: abreviadas y reduzidas en forma de Repertorio decisivo por orden del A. B. C., Alcalá, 1540; Medina, 1553.—El valenciano D������� C������� publicó Don Valerian de Hungría, Valencia, 1540. Pongo en 1540 la Relación del Sitio del Cuzco, y principio de las guerras civiles del Perú hasta la muerte de Diego de Almagro (1535 á 1539), Ms. de la Bibl. Nac., publicado en Madrid, 1879. Varias relaciones del Perú y Chile (Libr. rar. y curiosos).

B��������� D���, estudiante legista, de Valladolid, publicó en 1540 y 1548 Los emblemas de Alciato Traduzidos en rhimas Españolas. Las Instituciones imperiales, de Justiniano, elegantemente vertidas del latín, Tolosa, 1551; Salamanca, 1614. Examen de la Composición Theriacal de Andromacho, traducida de Griego y Latín en Castellano y comentada por el ���������� L����, Burgos, 1540.

—J. P������ escribió Anales de Aragón desde el año 1540... hasta el año 1558, Zaragoza, 1705. A������ P���, aragonés, de Alfocea, publicó Grammaticae annotationes in IV et V Ant.

Nebrissensis libros, Zaragoza, 1540, 1555. Caenotaphium in obitu Caroli V Imp. Caesaraugustae celebrato, ibid., 1558.—Quaestiones logicae sec. viam Realium et Nominalium, Alcalá, 1540. F���

F�������� R���, de Valladolid, benedictino, publicó Index... in Aristotelis Stagiritae opera, quae extant, y Judicium de Aristotelis operibus, 2 vols., Sahagún, 1540. Regulae CCCXXXIII intelligendi Sacras Scripturas, Lyon, 1546 J������� S������ publicó la Primera parte de la Carolea, trata las victorias del Emperador Carlos V, Valencia, 1540. Segunda parte de la Carolea, Valencia, 1540. Caballería celestial de la Rosa fragante, Valencia, 1554; Amberes, 1554: libro de caballerías á lo divino. Segunda Parte de la cauallería de las hojas de la Rosa Fragante, Valencia, 1554. Primera y segunda parte de la Carolea, Valencia, 1560.—L��� V�����, autor de las más antiguas tablas anatómicas, publicó In Anatomen corporis humani tabulae quatuor, 1540. L��� �� V���������, mallorquín, canónigo de Mallorca, publicó De Legatis, Alcalá, 1540.

110. Año 1541. G������� S�������� R�������� ��

M��� (1520-1569) nació en Lisboa, adonde acababan de llegar de Zafra su padre el doctor J. Rodríguez, llamado para médico del rey de Portugal don Juan III, y su madre, que ya iba preñada, doña María de Mesa. El año 1527, viniendo la infanta doña Isabel de Portugal á casarse con el emperador Carlos V á Castilla, acompañóle como médico el dicho doctor, trayendo á Gregorio Silvestre de siete años, el cual, á los catorce de edad (1534), entró al servicio de don Pedro, conde de Feria, y en su casa se aficionó á las poesías de Garci-Sánchez de Badajoz, que la frecuentaba, dándose además á la música de tecla. Á los veintiocho de edad comenzó á tener nombre entre los que se preciaban de componer los versos españoles que llamaban Ritmas antiguas y los franceses Redondillas, á los cuales se dió tanto por el amor que tuvo á Garci-

Sánchez, á Bartolomé de Torres Naharro y don Juan Fernández de Heredia, que no pudo ocuparse en las Composturas italianas, que Boscán introdujo en España en aquella sazón, y así imitando á Cristóbal de Castillejo dijo mal de ellas en su Audiencia de Amor. Pero después, con el discurso del tiempo, viendo que ya se celebraban tanto los sonetos, tercetos y octavas, compuso algunas cosas dignas de loa, y si viviera más tiempo, fuera tan ilustre en la

poesía italiana como lo fué en la española. En 1541, viviendo en Montilla, ganó por oposición el cargo de organista de la catedral de Granada, contrayendo después la obligación de escribir cada año para las fiestas nueve entremeses y muchas estancias y chanzonetas. Casó con la guadixeña Juana de Cazorla, teniendo de ella varios hijos, entre ellos Juan (1547), Luis (1552), Paula (1567) y Mayor (1569). Era hombre de muy agudo ingenio y donaire y muy estimado en la ciudad. Fué muy amigo de Barahona de Soto, decidido italianista. Murió el 1570, de cincuenta años, de una calentura pestilencial con tabardete. Escribió muchas obras amorosas y no menos obras espirituales por su cargo de organista, obras morales, una glosa á las coplas de Jorge Manrique y á otras muchas, y gloriábase de ser glosador más que poeta.

111. Publicaron sus Obras la viuda, doña Juana de Cazorla, y sus hijos, Granada, 1582, con su vida, escrita por Pedro de Cáceres y Espinosa; Lisboa, 1592; Granada, 1599. Poema de Proserpina, Granada, 1599. Discurso, de Pedro de Cáceres y Espinosa, en sus Obras: "Nació Gregorio Silvestre en Lisboa, en el año de 1520, entre los dos últimos días del dicho año, que tienen la advocación de los dos Santos, por los cuales llamado así. Yendo su madre doña María de Mesa, preñada desde Zafra, donde antes vivía, por haber sido el Dr. J. Rodríguez, su padre, llamado entonces para Médico del Rey de Portugal, y estuvieron en servicio del Rey hasta el año de 27, que viniendo la Infanta doña Isabel de Portugal á casarse con el Emperador Don Carlos V á Castilla vino por su Médico el dicho

Doctor, trayendo á Gregorio Silvestre de siete años, como parece en el privilegio que en este mismo año les concedió el Emperador á ellos y á sus descendientes. Siendo Silvestre de casi catorce años vino en servicio de Don Pedro, conde de Feria, do á la sazón florecía entre los Poetas Españoles Garci-Sánchez de Badajoz; y como siempre la casa del Conde fuese llena de curiosidad, y visitada con los escritos de aquel célebre Poeta, participó tanto de lo uno y de lo otro, que se preciaban de componer los versos Españoles que llaman Ritmas antiguas, y los franceses Redondillas. Á las cuales se dió tanto, ó fuese por el amor que tuvo á GarciSánchez y á Bartolomé de Torres Naharro y á D. Juan Fernández de Heredia, á los cuales celebraba aficionadamente, que no pudo ocuparse en las Composturas Italianas que Boscan introdujo en España en aquella sazón. Y así, imitando á Cristóbal de Castillejo, dijo mal de ellas en su Audiencia (de Amor). Pero después, con el discurso del tiempo, viendo que ya se celebraban tanto los Sonetos y Tercetos y Octavas... compuso algunas cosas dignas de loa: y si viviera más tiempo, fuera tan ilustre en la Poesía Italiana, como lo fué en la Española. Con todo eso intentó una cosa bien célebre, que fué poner medida en los versos Toscanos, que hasta entonces no se les sabía en España: la cual pocos días antes intentó el cardenal Pedro Bembo en Italia; como parece en sus Prosas, y lo refiere Lodovico Dolche en su Gramática. Y que en España no se supiesen, ni la trujesen los que trujeron la Poesía Toscana á ella, parece en que Castillejo aún no supo la medida Española de arte mayor; pues queriendo conferir la una y la otra, introduce á Juan de Mena diciendo de las Trovas Italianas: "Juan de Mena, cuando oyó | La nueva trova pulida, | contentamiento mostró; | Caso que se sonriyó | Como de cosa sabida. | Y dijo: "según la prueba, | Once sílabas por pie | No hallo causa por qué | Se tenga por cosa nueva, | Pues yo también las usé". De suerte que Castillejo quiere probar que las composturas de Juan de Mena y Juan Boscán son una misma, pues constan de once sílabas... por no entender la medida de los pies; la cual se descubrió en España en esta sazón; y en Granada Silvestre fué el que la descubrió... y por esto se dijo dél: "Y que por vos los versos desligados | De la Española Lengua, é Italiana | Serán con la

medida encadenados; | Deberos ha de aquí la castellana | Más que la Griega debe al grande Homero | Y al ínclito Virgilio la Romana". De aquí ha venido la medida de los endecasílabos á hacerse en España por jambos tan comúnmente que no hay quien la ignore... Murió en el año de 1570 siendo de cincuenta años, poco después de la rebelión de Granada, de una calentura pestilencial con tabardete. Murió también el mayor de sus hijos en aquella sazón; y vive el menor. De sus hijas la una entró Monja, sin dote, porque era diestra en la Música de tecla, y hacía versos aventajadamente. Las otras quedaron con su madre. Fué Silvestre de agudo ingenio; y en conversación hablaba muy discretamente, casi siempre con dichos agudos y donosos Hablando una vez á ciertos amigos en compañía de Juan Latino, dicen que habló á todos y no á él... y quejándose Juan Latino dello, dicen que respondió: "Perdone, Señor Maestro, que entendí que era sombra de uno destos Señores". Dícese también que uno de los que entonces componían en Granada le hurtó un Soneto, y vínoselo á enseñar por proprio, y preguntarle qué tal le parecía... "¿Qué le parece?—Que me parece". Disgustado con el Conde de Miranda porque le hablaba de vos, no le había visitado muchos días, y que como una vez le encontrase el Conde en la calle, le dijo: "—Señor Silvestre, ¿por qué no vais á mi casa vos?— Señor, por eso". De lo cual se rió el Conde, y entendiéndole procuró emendarse de ahí adelante... Otros muchos y muy discretos (donaires) hay suyos, que por ventura juntará algún curioso. La pintura de su cuerpo y rostro fué extraña, y tanto que le llamaban monstruo de Naturaleza, porque doquiera era notado entre muchos hombres, aunque de estatura mediana Era hombre descuidado de su atavío corporal, como casi siempre lo son los que, ocupados en mayores cosas, no se acuerdan de sí. Tuvo por Mecenas y favorecedor de sus escritos á D. Alonso Puertocarrero, hijo del Marqués de Villanueva: al cual hizo muchas coplas y sonetos, aunque parecen pocos. Y á D. Alonso Benegas, al cual hizo una elegía á la muerte de su mujer... Tuvo por particulares amigos los que entonces eran famosos en Granada, el singular abogado Luis de Berrío; á D. Diego de Mendoza, y á Fernando de Acuña, honra de la Poesía de España; el Maestro Juan Latino, doctísimo en la

Gramática Latina y Griega; el gran traductor Gaspar de Baeza, y el Bachiller Pedro de Padilla, habilidad rara y única en decir de improviso, y á pocos inferior en escribir de pensado; y al Licenciado Luis de Castilla, que le escribió una Carta, á la cual respondió con otra; y al Licenciado Josef Fajardo, hombre insigne en las Matemáticas y Lenguas Latina y Griega, Hebrea y Caldea y Arábiga, del cual hay ciertos sonetos en loa de Silvestre, y al Licenciado

Macías Bravo, y otros muchos que escribieron en su loor algunos versos. Escribiéronle Cartas Poéticas el famoso Pedro de Padilla, y George de Montemayor, y Francisco Farfán, el indio, y la que más se estimó en aquellos tiempos, fué la de Luis Barahona de Soto, el cual también fué uno de sus particulares amigos Parte de sus obras se han conservado, y parte están perdidas. Escribió muchas obras espirituales, así por ser él aficionado á religión, como por darle ocasión la iglesia mayor, donde era organista; obligándose por sólo su gusto cada año á hacer nueve Entremeses y muchas estancias y chanzonetas: en el cual oficio sucedió al famoso Maestro Pedro Mota, complutense, y al Licenciado Jiménez, que hizo el Hospital de Amor, que imprimió por suyo Luis Hurtado de Toledo; que éstos también tuvieron cargo de escribir estos Entremeses para las fiestas más célebres de la iglesia mayor; aunque al uno y al otro supo aventajarse sin comparación alguna. Escribió Obras morales muchas, una glosa á las coplas de D. Jorge Manrique. Glosó otras muchas cosas, y tuvo para esto particular ingenio, más que para otra cosa; y así lo solía él decir, que no era Poeta, sino glosador. Escribió muchas obras amorosas, teniendo por sujeto casi desde su niñez á una dama llamada doña María, cuya calidad, por razonable respeto, no se explica. Murió esta Señora el mismo año que Gregorio Silvestre, mes y medio antes que él... Sintió mucho Gregorio Silvestre la muerte de doña María; y así dicen que se determinó á hacer muchas canciones á su muerte á imitación del Petrarca; y pienso que hizo una ó dos... y como murió tan presto no pudo pasar adelante con su intento. Está enterrado en la iglesia del Carmen". Epitafio: "Yace en esta iglesia chica | Y entre sus piedras aquel | De quien la fama infiel | Más entiende que publica. | Mas pues ella no lo explica, | Pregúntaselo al Laurel, | Al Moral, Lirio y

Clavel, | Y á mil Glosas que por él | Hacen nuestra España rica" Las obras de Silvestre están divididas en cuatro libros. El libro I contiene: Diez Lamentaciones, que acaban en el fol. 23; cinco sátiras; multitud de glosas, canciones, etc., todo con coplas castellanas. El libro II: Fábula de Dafne y Apolo; Píramo y Tisbe; La visita (de cárcel) de Amor; La residencia de Amor. El libro III: Glosas y canciones de moralidad y devoción; dos romances devotos; glosa sobre las coplas de don Jorge Manrique. El libro IV contiene los versos que dicen á la larga y al través, endecasílabos, etc.; sonetos, y la Fábula de Narciso, en octavas.

Gregorio Silvestre, Poesías, Bibl. de Aut. Esp., ts. XXXII y XXXV. Consúltense: D. García Peres, Catálogo razonado biográfico y bibliográfico, etc., Madrid, 1890. H. A. Rennert, en Modern Language Notes (1899), t. XIV, cols. 457-465. F. Rodríguez Marín, Luis Barahona de Soto, etc., Madrid, 1903, págs. 32-35.

112. Año 1541. F������ �� O����� (1499?-1555?), zamorano, hijo de Lope Docampo, que lo fué de Diego de Valencia y de la portuguesa Sancha Garzia Docampo, estudió en Alcalá con Nebrija y otros maestros, fué nombrado canónigo de Zamora y por Carlos V cronista imperial. Las Cortes de Castilla de 1555 pidieron al Emperador se le señalase sueldo para que pudiese acabar su historia, sin ocuparse en las obligaciones de su canonjía. Ambrosio de Morales alaba su mucha diligencia y trabajo y la grandeza de su estilo, continuando su obra. Dañóle el crédito que dió al seudo Beroso, publicado por aquel tiempo. De las cuatro partes que pretendía escribir, tan sólo un pedazo de la primera acabó con

el título de Los quatro libros primeros de la Crónica general de España, Zamora, 1544. Quiso llegase esta primera parte hasta Jesucristo; pero dejóla en los Escipiones, y se publicó en Zamora, 1544; con el quinto libro en Medina, 1553. No es gran historiador cuanto al fondo, sus noticias son poco seguras y el estilo nada tiene de particular.

113. Estos cuatro, de los cinco libros, se los sacó un impresor, según da á entender Florián en carta á Juan de Vergara. Dice que enmendó muchas cosas para la edición siguiente; pero habiendo fallecido antes de darla, fué publicada, completa ya en sus cinco libros, por Ambrosio de Morales, en Alcalá, 1578; Valladolid, 1604 Había antes publicado por primera vez la crónica llamada de Alfonso el Sabio, en 1541. Cita á Juan de Viterbo y su Beroso y á Manethon, obras ya desechadas antes de él. Véase Nicerón, Hommes illustres, París, 1730, t XI, págs 1-2, y t XX, págs 1-6 Las quatro partes enteras de la Crónica de España, de Alfonso X, Zamora, 1541; Valladolid, 1604; extracto del ms. original de la Coronica ó grande Estoria general de Espanna. En fabla antigua comenzada á copilar no tempo do Rey Don Alfonso X, precioso códice acabado en la era de 1403, hoy propiedad del librero Vindel, Madrid; está en galaicoportugués. Los quatro libros primeros de la Crónica general de España, Zamora, 1544; Zamora (sin fecha); Medina, 1553, con el 5.º libro; Alcalá, 1564. Los cinco libros primeros De la Coronica general de España que recopilava el maestro Florián de Ocampo, Alcalá, 1578; Valladolid, 1604. Crónica general de España por Florián de Ocampo, Ambrosio de Morales y Fr Prudencio de Sandoval, Madrid, 1791-93, 15 tomos. Consúltese: G. Cirot, Les Histoires générales d'Espagne entre Alphonse X et Philippe II (1284-1556), Bordeaux, 1905, págs. 97-147. Su biografía, en la Biblioteca de escritores que han sido individuos de los seis colegios mayores, por José de

Rezabal y Ugarte, págs 233-8; y en la impresión de su Crónica de 1791.

114. Año 1541. B����� �� G����, racionero de Toledo, publicó Dos Cartas en que se contiene, cómo sabiendo una señora que un su servidor se quería confessar: le escribe por muchos refranes, Toledo, 1541, con otras dos, una que dice le dió Juan Vázquez de Ayora; otra impresa en Toledo. Salió la obra con el título de Cartas en refranes, con las coplas de Jorge Manrique, los refranes de H Núñez y con los de Mal-Lara: Toledo, 1541; 1545 (sin lugar); Venecia, 1553; Medina, 1569; Alcalá, 1570; Sevilla, 1575; Amberes, 1577; Sevilla, 1577; Huesca, 1581; Alcalá, 1581; Huesca, 1584; Alcalá, 1588; Madrid, 1598; Bruselas, 1608, 1612; Lyon, 1614; Madrid, 1614, 1617, 1619; Lérida, 1621; Madrid, 1632, 1864. Arcadia de Jacobo Sannazaro, Toledo, 1547, hecha la prosa por el canónigo Diego López de Toledo y el verso por el capitán Diego de Salazar: así lo dice el editor Garay en el prólogo, añadiendo que él mismo retocó los versos; ibidem, 1549; Salamanca, 1578. Inéditas quedaron otras traducciones de la Arcadia por Juan Sedeño y por Jerónimo de Urrea (Gallardo, núms. 3900 y 4120); los manuscritos, en la Bibl. Nacional.

M����� L��� �� O������, de este pueblo, canónigo burgalés, secretario del ilustrísimo cardenal don Francisco de Mendoza, obispo de Burgos, publicó el grandilocuente libro que tituló La Historia que escribió en latín el Poeta Lucano, sin lugar ni año de impresión; después en Lisboa, 1541. Las ediciones de Burgos, 1578 y 1588, llevan además la Historia del Triunvirato, y va dirigida "al ilustrísimo señor don Antonio Pérez, secretario del estado de la Magestad Cathólica del Rey don Phelippe Segundo". Tanto la traducción como la historia original suya están escritas en estilo elevado, magnilocuente, cual lo pedía el poeta traducido; pero sin el menor rastro de mal gusto. Gran fidelidad en la versión, propiedad en las voces, muchas poco usadas, pero de hondo casticismo; es uno de los mejores libros escritos en romance.

M���� A����, natural alemán, publicó Tratado muy útil y provechoso para toda manera de tratantes y psonas afficionadas al contar, Valencia, 1541. Libro primero, de arithmética algebrática, en el qual se contiene el arte Mercantival, con otras muchas Reglas del arte menor, y la Regla del Algebra, vulgarmente llamada Arte Mayor ó Regla de la cosa: sin la qual no se podrá entender el décimo de Euclides ni otros muchos primores, assí en Arithmética como en Geometría, Valencia, 1552. A������ B���� tradujo el Diálogo, de Sepúlveda: Diálogo llamado Demócrates compuesto por el doctor Juan de Sepúlveda, Sevilla, 1541.—El ������ D����� C����� ��

M������� publicó el Libro del arte de las Comadres ó madrinas y del regimiento de las preñadas y paridas y de los niños, Mallorca, 1541: primera obra de obstetricia en España y de las más notables de la antigüedad.—F��� J��� �� �� C���, dominico talaverano, publicó La Historia de la Iglesia, que llaman Eclesiástica y Tripartita, Lisboa, 1541; Coimbra, 1554. Diálogo sobre la oración..., Salamanca, 1555. Suma de los Mysterios de la Fee de Fr. F.co Titelman, ibid., 1555. Chronica de la Orden de Predicadores, Lisboa, 1567. Treinta y dos Sermones, Alcalá, 1568. Epitome de Statu Religionis, Toledo, 1611; Madrid, 1613, 1622. Directorium conscientiae, Madrid, 1620; Toledo, 1624, 1626, 1628, 1631; Madrid, 1648. Enquiridio ó manual del cavallero christiano, de Erasmo, Lisboa, 1541. C�������� �� E������ publicó De causis corruptae eloquutionis, 1541. De verbis exceptae actionis. De verbis impersonalibus, etc. De naturalium nominum ratione lucubratio. De viris latinitate praeclaris in Hispania La Historia Eclesiástica de Eusebio Cesariense, Lisboa, 1541. F�������� �� �� F����� publicó Grammatica Methodus, Alcalá, 1541.—Libro artificioso para todos los pintores, Amberes, 1541. L��� L����� �� Á����, médico de Carlos V, publicó Vergel de Sanidad (¿Alcalá, 1541?). Remedio de cuerpos humanos y silva de experiencias y otras cosas utilíssimas, Alcalá, 1542; Venecia, 1566. Libro de pestilencia curativo y preservativo, ibid., 1542. Antidotario muy singular de todas las medicinas usuales y la manera cómo se han de hacer, ibid., 1542. Libro de las quatro enfermedades cortesanas, que son

Catarro, Gota arthética, Sciática, Mal de piedra , Toledo, 1544

Libro de experiencias de medicina, Toledo, 1544. Regimiento de la salud; de la esterilidad de hombres y mugeres, y enfermedades de los niños, Valladolid, 1551. D�� A����� R��� �� V����� († 1549)

nació en Olmedo, fué benedictino, doctísimo teólogo y perito en lenguas orientales; predicador de Carlos V, á quien acompañó en el viaje de 1540 á 1541 á Flandes y Alemania; obispo de Canarias y erasmista, procesado por la Inquisición (1537, de levi, ad cautelam). Escribió, con ocasión del casamiento de Enrique VIII de Inglaterra con Ana Bolena, Tractatus de matrimonio Regis Angliae, con Philippicae Disputationes viginti adversus Luterana dogmata, per Philippum Melanchthonem defensa, Antuerpiae, 1541 Collationes septem cum Erasmo Roterodano habitae (Nic. Ant.). Véase M. Pelayo, Heterodoxos, t. II. Vergara: "Erasmi usque ad invidiam percupidus". Vives: "homo [Greek: γνησίος ὲρασμϰός]". Al. Valdés: "aventajando á los demás en erudición y piedad, no podía menos de favorecer las buenas letras y la sincera religión". Bonilla cree que tradujo parte de los Coloquios de Erasmo (véase Luis Mexía, 1528). F��� M����� �� S������ (1501-1567), jerónimo zaragozano, publicó la primera Rhetórica en lengua castellana, Alcalá, 1541, para uso de predicadores. Tratado de la forma que se debe tener en leer los autores, ibid., 1541. Tratado para saber bien leer y escrivir, pronunciar y cantar letra assí en latín como en romance, Zaragoza, 1551. Libro apologético que defiende la buena y docta pronunciación que guardaron los antiguos, Alcalá, 1563; Madrid, 1587. Primera Parte de la Ortografía y origen de los Lenguajes, Alcalá, 1563, 1567 Manera para poner en ejercicio las reglas de retórica. Tratado de los avisos en que consiste la brevedad. Origen de los lenguajes, Alcalá, 1567. Dejó mss.: Libro de poesía y espirituales conceptos. Prontuario para saber las costumbres y usos del monasterio de S. Engracia en Zaragoza. Breve summa lamada Sossiego y descanso del ánima, Alcalá, 1541.

115. Año 1542. M����� �� A��������� ó �� ������ N������ (1492-1586), por haber nacido en

Barasoain del Valle de Orba, cerca de Pamplona, hijo de Martín de Azpilcueta y de doña María, el más célebre de nuestros canonistas y moralistas, de la misma familia de San Francisco Javier, fué canónigo regular de Roncesvalles, estudió en Alcalá y Tolosa, donde enseñó Cánones, así como en Cahors, y á pesar de ser extranjero le quisieron nombrar consejero del Parlamento de París, cosa que no aceptó. Volvió á España y obtuvo por oposición la cátedra de prima de Cánones en Salamanca, que regentó catorce años; pero llamado por Juan III de Portugal, enseñó otros diez y seis en la Universidad de Coimbra, renunciando á la mitra que le ofrecía. Convencido de la inocencia del Arzobispo de Toledo, Carranza, Felipe II le nombró su abogado en Valladolid y en Roma, donde vivió el resto de sus días, ayudando al Cardenal Penitenciario apostólico por orden de Pío V y siendo obsequiado por Gregorio XIII que le visitaba en su casa, por su discípulo el cardenal Pedro Deza y por toda la Corte pontificia. Varón sapientísimo y santísimo por su mortificación y virtudes, tenía un juicio maravilloso para desenmarañar cuestiones morales y una portentosa erudición. Sixto V le hizo extraordinarios funerales y el pueblo le honró en su muerte como á santo. Manejaba el castellano con la limpieza y brío de los mejores de su tiempo. Son notables, entre sus

muchas y autorizadísimas obras, el Tractado de alabanza y murmuración, Coimbra, 1542; el Tratado de la Oración, Horas canónicas y otros divinos oficios, Coimbra, 1545; el famosísimo Manual de Confesores, Coimbra, 1553, el Comentario resolutorio de usuras, Salamanca, 1556, y el Capitulo veynte y ocho de las Addiciones del Manual de Confessores, Valladolid, 1566.

M����� �� A���������.

(Salesa lo dibuxó. D.n Mn.l Salv.r Carmona lo gravó)