ATTACKER’S CAPABILITIES

XI BOMBER COMMAND IN NORTH AFRICA

B-24D (41-11591)

As detailed below, the Tidal Wave plan had a requirement for five heavy bombardment groups. Two of these were already in the North African Theater of Operations (NATO). The 376th Heavy Bombardment Group, commanded by Col Keith K. Compton, had grown out of the earlier Halverson Detachment and still included aircraft and crews who had flown the original 1942 mission. The 98th Heavy Bombardment Group, commanded by Lt Col John “Killer” Kane, had arrived in North Africa later in the summer of 1942. Both of these groups had seen extensive combat and were familiar with operating conditions in the Mediterranean theater.

The two desert commanders had strained personal relations that complicated the execution of Operation Tidal Wave. “K. K.” Compton was a by-the-book commander, and a teamplayer who was well liked by the senior USAAF commanders in the Mediterranean theater. “Killer” Kane’s nickname stemmed from a comic book character in the “Flash Gordon” series, and not from any particular bloody-mindedness. He was a charismatic but abrasive leader and showed particular disdain for “experts” from Washington who had not seen extensive combat experience on the B-24 bomber. Their differences in command style eventually erupted over the issue of flying techniques, as is described in more detail below.

The low-altitude tactics for the Ploesti mission were first demonstrated by the 201st Provisional Combat Wing in Britain. The commander of this formation, Col E. J. Timberlake, was instrumental in the training regimen for the Ploesti mission. It was the three heavy bombardment groups from this wing that were transferred from the Eighth Air Force in Britain to the IX Bomber Command in Libya for Tidal Wave.

The three groups flew to Libya from Britain in late June 1943.

The 44th Heavy Bombardment Group had seen its combat debut in November 1942 and by early March 1943 had lost 13 of its original 27 B-24s. During the May 14, 1943 mission on the German submarine base at Kiel, the 44th lost five of its 17 B-24s and its gunners were credited with having shot down 21 German fighters. The 44th was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation for its conduct on this mission. The group left Britain for Libya on June 27.

“Lorraine” of the 513th Squadron, 376th Group, piloted by Lt William Zimmerman, is seen here splashing through “Lake Manduria,” an area flooded by a recent rainfall at one of the bases near Benghazi. This aircraft served with the original HALPRO detachment when it was known as “Queen Bee.”

Leading Tidal Wave aboard the B-24D command ship “Teggie Ann” was the 386th Group commander, Col K. K. Compton to the left and leader of IX Bomber Command, Brig Gen Uzal Ent to the right.

B-24D (42-72843) flew with the 512th Squadron, 376th Group but did not take part in the August 1, 1943 Tidal Wave mission. It is the best-known B-24D, preserved at the National Museum of the US Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio.

The 93rd Group had seen its combat debut on October 9, 1942 attacking factories near Lille, France. It spent much of the fall of 1942 attacking German U-boat pens on the Bay of Biscay on the French Atlantic coast. A large detachment from the group was sent to North Africa in December 1942, receiving a Distinguished Unit Citation for operations in that theater. The detachment returned to England in late February 1943 and continued missions in France, the Low Countries, and Germany. The 93rd Group departed the UK on June 26.

The 389th Group was new and inexperienced, departing the UK last on July 2. All five groups were equipped with the B-24D Liberator heavy bomber, but the 389th Group had received a later production series fitted with a ball turret in the belly. Since this had different handling characteristics, this group was assigned a mission slightly separate from the other

groups, attacking the refinery in Câmpina north of Ploesti. In the event, the ball turrets were removed prior to Tidal Wave to reduce weight and drag and permit greater range since underbelly defense was not a high priority on a low-level mission.

Prior to the Ploesti mission, the five groups conducted 1,183 sorties in support of Operation Husky in July 1943. During these missions, 18 aircraft were lost, including ten in combat. The last of these was a mission on Rome on July 19, after which the groups were sequestered for training for the Ploesti mission.

In late March 1943, Lt Norman Appold of the 376th Group suggested using low-altitude tactics to deal with the reinforced concrete train sheds on the Gulf of Messina on Sicily that had proven impervious to previous attacks from normal altitudes. Col K. K. Compton, the group commander, approved the mission to help gain experience in low-altitude tactics. This attack took place on the night of March 29–30. In the event, low overcast obscuring the target prevented the intended attack, but the secondary target of the rail yards at Crotone were successfully bombed. In the wake of this raid, Lt Brian Flavelle suggested a twilight raid to avoid the early morning mists that had foiled Appold’s attacks. This was conducted on April 1, 1943 with Flavelle leading the attack in the lead aircraft “Wash’s Tub.” These two small-scale raids gave the lead Tidal Wave group some confidence that the Liberator could be used in low-level attacks.

The Tidal Wave training program in late July 1943 was intended to show that large formations could safely conduct a mission at low altitude. The training regime was aimed at preparing the five Liberator groups to safely conduct the low-altitude attack while placing as many aircraft over the target in the shortest amount of time possible to minimize losses to enemy air defenses. Individual crews were expected to be able to drop bombs from 300ft (90m) with a maximum circular error of no more than 100ft (30m). A training target was erected in the desert near Soluch, Libya. Training began on Tuesday, July 20 with briefings, followed by

B-24D “Wash’s Tub” (4111636), served with the 514th Squadron, 376th Group at Ploesti, piloted by Lt James Bock. It survived 73 missions and is seen here in September 1943 when sent back to the United States for a bond drive.

A close-up of the nose of “Lorraine” showing the two machine guns added as forward armament on some of the Tidal Wave B-24D for Flak suppression.

Due to the importance of Tidal Wave, the Ninth Air Force installed numerous cameras in the bombers to record battle damage. Here, Capt Jesse Sabin of an USAAF Combat Camera unit makes a final inspection of a camera mounted in the bombardier’s position in one of the B-24D bombers.

practice missions by single aircraft, 6-ship formations, and 12-ship formations. One of the crew members later recounted that:

We ran approximately 12 missions over the replica of the oil fields, approaching, attacking, and departing exactly as we intended doing on the actual raid. Each element was given a specific dummy target … and we practiced until we could bomb it in our sleep. When we finally did get over Ploesti, our movements were almost automatic.

The training program was nearly derailed by the widespread outbreak of amoebic dysentery among the aircrews and ground crews who at the time were living in very primitive desert conditions. Although the worst of the outbreak had abated by the time of the mission, a significant number of the crews were still weakened from the aftereffects of the infection at the time of the mission.

On July 28 and July 29, the entire task force participated in a gigantic mock attack mission, bombing the dummy targets with 100lb practice bombs in a two-minute assault. Besides the training missions, an extensive program of briefings was conducted. Five large models of the target area were prepared with RAF assistance including 1:50,000 scale models of Ploesti, Brazi, and Câmpina. Special navigational aids were provided to each navigator including detailed map references along with photographs and sketches of the main check points along the route to provide explicit visual cues. Each crew received their own target folder that included target map sheets and perspective drawings of their targets at the refineries. The

bombardiers were provided with special illustrations of their specific aim points. It was the most carefully prepared USAAF heavy bomber mission to date.

Capping the preparation was a special 45-minute film that provided an overview of the mission, detailed information for pilots and navigators, and finally a portion devoted to the bombardiers. A later USAAF report summarized the message of the film: The job was tough, although by no means impossible. The mission’s importance justified the risk.

The original plans assumed that the mission would be led by the Ninth Air Force commander, Maj Gen Lewis Brereton, and would include other key officers such as Col Jacob Smart and Col Edward J. Timberlake. In the event, USAAF chief Hap Arnold sent explicit instructions days before the mission that Brereton, Smart, and Timberlake would not take part in the mission since they were all privy to a broad range of top-secret information that could not be put at risk. As a result, Brig Gen Uzal Ent, the head of IX Bomber Command, would lead the mission.

Aside from the crew training, the IX Bomber Command undertook a Herculean maintenance effort on the aircraft. At the start of the training period, 191 aircraft were available but only 131 were operational. The main problem was a shortage of engines since the average time between overhauls for the engines was only 200 hours. After additional aircraft were flown in, and new engines provided, IX Bomber Command had 193 B-24D bombers ready on July 31 out of the 202 on hand.

The main disagreement between group commanders Compton and Kane was over the matter of the optimum flying method for the B-24 bomber. Compton listened to outside experts who advised flying the B-24D on the mission at a high speed to gain optimum lift from the bomber’s Davis wing design. Kane disagreed with this flying technique, arguing that too many of his bombers were suffering from the abrasive desert conditions which resulted in low engine life and high oil consumption. Kane’s group was based deeper in the Libyan desert exacerbating this problem, while Compton’s was nearer the coast. Kane recommended a more cautious application of speed on the approach to Ploesti to minimize bombers aborting the mission due to mechanical problems. In the event, the senior commanders such as Brereton and Ent did not step in and settle the matter, and this dispute remained simmering in the background.

The B-24D Liberators had two major modifications for Tidal Wave. A portion of the aircraft leading the formations had additional .50cal heavy machine guns added in the nose for strafing Flak batteries. In addition, all aircraft received two jettisonable 400-gallon “Tokyo” tanks in their bomb-bay to extend their effective range. Some aircraft also had armor plate added, mostly taken from crashed Allied and Axis fighters.

The bomb loads of the individual aircraft were tailored to their specific targets. All bombs were fitted with delay fuzes since the bombs were dropped from such low altitudes. Of the 1,000lb bombs, most were fitted with one-hour delay fuzes but two dozen had one- to sixhour delay fuzes. The 500lb bombs were mostly fitted with 45-second delay fuzes, but about a quarter had longer delays. The long-delay fuzes were intended to discourage fire-fighters. Many aircraft were issued with boxes of small British incendiary thermite bombs that were carried near the waist gun positions for the gunners to throw out when passing over the targets.

IX Bomber Command Heavy Bombardment Groups, Operation Tidal Wave

Group Commander Nickname Target Operational strength

376th BG Col Keith Compton Liberandos White I 29

93rd BG Lt Col Addison Baker Flying Circus White II, III 39

98th BG Lt Col John Kane Pyramiders White IV 47

44th BG Col Leon Johnson Flying 8-Balls White V, Blue 37

389th BG Col Jack Wood Sky Scorpions Red 26

DEFENDERS’ CAPABILITIES GUARDING THE

BLACK GOLD

The barrage balloon barrier around Ploesti accounted for at least four B-24D bombers during the Tidal Wave raid and damaged many more. The standard German type was the 200m3 Sperrballone, so designated by the volume of hydrogen contained. The original barrier around Ploesti was established by the Luftwaffe but, in October 1942, the Germans turned over responsibility to the Romanian 3rd Balloon Battalion.

Germany’s dependence on Romanian oil after the June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union prompted Berlin’s intense interest in the defense of the Ploesti oil refineries. Romania’s defensive capabilities were quite modest, even after the May 27, 1940 “oil-for-arms” treaty that pledged a steady stream of German weapons in return for Romanian oil. The September 1940 coup by Gen Ion Antonescu set the stage for closer German-Romanian military cooperation, and the following month, the Luftwaffe began to deploy a special Luftwaffe mission to Romania to improve the air defense situation.

Romanian AAA defense

The Romanian army slowly modernized its antiaircraft artillery (AAA) forces through the 1930s, though within the crippling constraints of a threadbare defense budget. On July 1, 1930, the Air Defense Command (CAA: Comandamentul Apărării Antiaeriene) was formed to accelerate the modernization of national air defense. By the late 1930s, Romania had a very modest force of 18 antiaircraft artillery (AAA) batteries equipped mainly with machine guns and small numbers of antiaircraft guns. There were only three fixed site AAA batteries in Bucharest with old French 75mm M1897 guns and one battery each in Braşov and Galaţi with the Škoda 76mm gun. In April 1940, the Prahova valley, including Ploesti, was defended by seven AAA guns, ten 13.2mm machine guns, 132 8mm machine guns, and a single searchlight battery. There were also three fighter squadrons assigned to defense of the oil region.

In 1938–40, efforts were made to improve the situation with new imports.

In 1939, the CAA was reorganized to unify air defense artillery, air defense fighter squadrons, and associated command-and-control networks. The three zones were designated as Air Region I Iasi (Regiunea I Aeriană Iasi), Air Region II Cluj, and Air Region III Bucharest; Ploesti was part of the Bucharest zone. Further centralization was undertaken on October 28, 1940 when

the Air Defense Command was assigned not only the national AAA regiments and air defense regions, but also territorial defense forces and the Passive Defense Service (Apărării Pasive). In February 1941, following the arrival of the first Luftwaffe Flak units, the joint Comandamentul Militar al Regiuii Petrolifere (Military Command of the Petroleum District) was organized under the command of Gen Vintilă Davidescu. This included various border guard, gendarme, and local defense units, as well as antiaircraft artillery. Overall command of the Ploesti Flak force was under Oberst Adolf Gerlach who headed the original Flak Lehr Regiment (Flak Training Regiment) that later became Flak-Regiment.180. Under his command was a Romanian AAA group under Lt Col Gheorghe Turtureanu that at the time included two battalions with seven 75mm batteries and a 13mm HMG battery.

By the summer of 1941, the Romanian air defense force had been expanded to nine antiaircraft gun regiments with 691 AAA guns. A portion of these antiaircraft regiments were assigned to the field army, but three regimental-sized air defense groups (Grupările antiaeriene) were created, named after their basing areas: Bucharest, Moldova, and Şiret. Ploesti fell within the Bucharest zone. The performance of Romanian antiaircraft batteries against Soviet raids in 1941 was mixed. The lack of modern fire controls and radar direction led to heavy wastage of precious stocks of expensive ammunition. Efforts were underway to license produce the Rheinmetall 37mm and Vickers 75mm guns at the Reşiţa and AstraBraşov factories as well as associated ammunition. Even as late as 1942, Romania’s air defense equipment was completely inadequate, as revealed by this Luftwaffe assessment.

Romanian Flak Equipment, 1942

Hotchkiss 13.2mm HMG 200

Oerlikon 20mm 45

Hotchkiss 25mm Mod. 30 75

Rheinmetall 37mm Mod. 18 184

Bofors 40mm 75

French 75mm M1897 semi-fixed 12

French 75mm M1897 self-propelled

76mm Mod. 25

To accelerate the modernization of the Romanian air defense forces in the Prahova/Ploesti region, in January 1942 the Luftwaffe agreed to transfer some of its antiaircraft equipment to Romanian crews. As a result, by the summer of 1942, the Romanian Ploesti defenses had been expanded to three machine gun batteries, 12 20mm batteries, two 37mm batteries, two 75mm Vickers batteries, 18 88mm batteries, and two searchlight batteries. In addition to these new weapons, the Romanian batteries were linked into the German fire control networks. By the summer of 1943, the Romanian national air defense units included 66 heavy AAA batteries, 55 light AAA batteries, 14 machine gun batteries, ten searchlight batteries, and three captive balloon batteries.

At the time of the August 1943 Tidal Wave attack, the Romanian AAA forces in the vicinity of Ploesti consisted of the 5th Air Defense Brigade (Brigada 5 Artilerie Antiaeriană), commanded by Col Ion Rudeanu. This included two regiments, the 7th AAA Regiment (Regimentul 7 Artilerie Antiaeriană) and the 9th AAA Regiment. These two regiments were deployed to supplement their German Flakgruppe counterparts. The 7th AAA Regiment deployed as part of Flakgruppe Ploesti in the immediate Ploesti area with 20 AAA batteries, four searchlight batteries, and a barrage balloon battalion. The 9th AAA Regiment was deployed with Flakgruppe Vorfeldschutz to the northwest of Ploesti in Prahova valley

BG

Intended Bomb Group axis of attack

BG

Targeted refineries

Barrage balloon battery

Romanian 88mm battery

German 88mm battery

Romanian 20mm battery

German 20mm battery

BG

WHITE I

WHITE II

WHITE

WHITE V

BLUE

Ploesti

OPPOSITE FLAKGRUPPE PLOESTI 1943

including Floreşti (two 20mm batteries), Băicoi-Ţintea (two 88mm batteries, two 20mm batteries), Câmpina (four 88mm batteries, two 20mm batteries), and Moreni (one 20mm battery) with a total of 14 AAA batteries and two searchlight batteries.

German Flak defense

In October 1940, the Luftwaffe began to deploy a special mission to Romania for the defense of the Prahova Valley/Ploesti and other key sites. Generalmajor Wilhelm Spiedel served as the Kommandierender General und Befehlshaber der Deutschen Luftwaffe in Rumänien, with his headquarters in the Lupeshtsi suburb of Bucharest. The initial force consisted of Luftwaffe Flak regiments, searchlight units, and Luftwaffe fighter units.

The first significant Luftwaffe Flak unit deployed for the defense of Ploesti in late 1940 was a Flak Lehr Regiment, subsequently renamed as Flak-Regiment.180. This regiment would form the core of the Ploesti air defenses through 1944. By early 1941, it included 16 88mm batteries, seven 20mm batteries, and one 37mm battery.

One of the first efforts by Luftwaffe air defense specialists was the creation of a full-scale decoy, mimicking the appearance of Ploesti at night. This was intended to lure away night bomber attacks. The first of these was created between Koměřu and Albesti, 18 miles (30km) southeast of Ploesti. The site was roughly similar in size and layout to Ploesti with false

Besides the large number of 20mm and 88mm Flak, the Ploesti defenses included numerous machine guns such as this Romanian twin 7.9mm water-cooled machine gun.

Luftwaffe Flak units began moving into Romania in the fall of 1941 to help defend key Romanian facilities including Ploesti. This is a 40mm Flak 28 position near Giurgiu, Romania on February 28, 1941 covering a key military bridge over the Danube on the RomanianBulgarian frontier.

streets and mock-up structures of wood and canvas. The decoy site included a network of street lights to create an appropriate appearance at night. The mock refineries included burn pits, filled with crude oil, that could be remotely ignited to simulate damage. A number of antiaircraft searchlights were deployed around the fake city. When enemy aircraft appeared within 75 miles (120km) of Ploesti, orders were issued to turn off the actual city lights and to turn on the false street lights. When the enemy aircraft were within 37 miles (60km), the searchlights at the dummy site were turned on.

This decoy system was effective against the initial Soviet night raids. It was useless on the July 13, 1941 daylight raid that approached the city from the northeast instead of the usual approach across the Black Sea from the southeast. By late July 1941, the Luftwaffe presumed that the Soviet units had become aware of the decoy city. A second Ploesti decoy was created west of Cioran, about 19 miles (30km) southeast of the Ploesti Decoy No. 1. When Soviet attacks resumed in August, the lights in Ploesti Decoy No. 2 were turned on. The Soviet pilots assumed this was the dummy city and continued toward Ploesti. In the meantime, the lights in Ploesti Decoy No. 1 had been turned on, and the Soviet aircraft bombers attacked this decoy. This ruse lasted until August 18, by which time the Soviet Black Sea Fleet had determined that a second false city had been created. Soviet aircraft avoided the decoys and attacked the real targets. As a result, the Luftwaffe created Ploesti Decoy No. 3 near Brateshanka, 4 miles (7km) west of Ploesti. The three dummy cities managed to confuse the Soviet pilots and to substantially reduce the damage caused by the summer 1941 Soviet air raids. The Soviet attacks petered out after August 1941 due to the advance of the German and Romanian armies along the Black Sea coast and the loss of critical air bases on Crimea in the fall of 1941.

In anticipation of the invasion of the Soviet Union and possible Soviet air attacks, the Flak defenses in the Ploesti area were expanded in the spring of 1941 to divisional size under the direction of Luftverteidigungskommando.10 (Air Defense Command 10), led

by Generalleutnant Johann Siefert. It followed the usual Luftwaffe Flak organization with two regional formations, Flakgruppe Ploesti and Flakgruppe Vorfeldschutz (Perimeter defense), sometimes called Flakgruppe Băicoi. These were reinforced regiments consisting of a Flak-Regiment with associated support units such as searchlights. Flakgruppe Ploesti was responsible for the defenses in the immediate vicinity of Ploesti while Flakgruppe Vorfeldschutz covered the northwest approaches to Ploesti in Prahova valley, mainly in the area of Băicoi and Câmpina. In turn, each group was divided into Untergruppen with one or more Flak battalions (Abteilungen). These battalions typically included five Flak batteries. The usual pattern was to place the heavy batteries, armed mainly with 88mm guns, furthest from the city, followed by another belt of light batteries, armed with 20mm and 37mm Flak guns, for close range defense.

A searchlight battalion (Scheinwerfer) unit was assigned to Ploesti with three batteries in Flakgruppe Ploesti and the remaining battery with Flakgruppe Vorfeldschutz. The organization of the force at the time of the outbreak of the war in the summer of 1941 is depicted in the chart below.

Flakgruppe Ploesti

Untergruppe Ploesti-Ost

HQ, Flak-Regiment.180

Res. Flakabt.904, Res.Flakabt.191

Untergruppe Ploesti-Sud Res. Flakabt.183

Untergruppe Ploesti-West Res. Flakabt.507

Untergruppe Scheinwerfer Res. Flakscheinw.Abt. 909

Flakgruppe Vorfeldschutz (Băicoi)

HQ, Flak-Regiment.229

Untergruppe Vorfeldschutz Ost Res. Flakabt.147

Untergruppe Vorfeldschutz Süd Res. Flakabt.761

The Luftwaffe Flak battalions were deployed in greatest concentration towards the east and southeast of Ploesti. This was the corridor from the Black Sea that was used most heavily by

A Luftwaffe 20mm Flak 30 automatic cannon stationed in a tank farm near Ploesti. These weapons were the most destructive element of Luftwaffe and Romanian defenses during Tidal Wave.

In 1942, the Luftwaffe began to deploy many of its heavier 105mm and 128mm Flak guns to railway carriages to permit them to be moved between objectives. This was one of the 128mm Flak 40 auf Geschützwagen schwere Flak Eisenbahnlafette deployed in a protected siding near BoldeștiScăeni, 9 miles (15km) north of Ploesti and seen here in the fall of 1944.

attacking Soviet bombers in the summer of 1941. The Romanian batteries were positioned mainly to the west and northwest of Ploesti.

On September 1, 1941, Luftverteidigungskommando 10 was redesignated as the 10.FlakDivision. There was considerable pressure to shift inactive Flak units to the battlefront due to critical shortages in Russia. As the threat of Soviet air attack against Ploesti abated in early 1942, the Luftwaffe succumbed to the temptation to shift more responsibility for the Ploesti Flak defense to the Romanians. Some of the Ploesti gun batteries and other equipment was transferred to Romanian control starting in January 1942, as mentioned above. In May 1942, the 10.Flak-Division was detached to Heeresgruppe Süd, though Flak-Regiment.180 remained in the Ploesti area.

The June 12, 1942 raid by the dozen HALPRO B-24D Liberators did little damage to Ploesti but provoked “a panic” in Bucharest and Berlin, according to Romanian accounts. The Luftwaffe began a major reorganization and reinforcement of air defenses around Ploesti. Generalmajor Alfred Gerstenberg, who had served as the air attaché at the embassy in Bucharest since February 1942, was reassigned as the Befehlshaber der Deutschen Luftwaffe in Rumänien in place of Gen Spiedel. Gerstenberg saw the HALPRO raid as merely the forerunner for expanded bomber attacks. Gerstenberg had served as a pilot in the Great War with Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring, and he had considerable political influence in Berlin as a result. He convinced the governments both in Berlin and Bucharest that Allied air attacks against Romania were likely to accelerate in 1943 and that much more elaborate defenses would be required to survive the onslaught. This included not only additional antiaircraft gun and fighter units, but

an integrated air defense network with modern radars. In addition, passive defenses were substantially improved including fortification of the Romanian refineries with blast walls to minimize bomb damage, modernization of the fire fighting forces in the refineries, and the creation of a pipeline around the city to link the various refineries. Gerstenberg also recommended that the defense of Festung (Fortress) Ploesti be unified under Luftwaffe control.

Marshal Ion Antonescu visited Hitler’s forward command post, Führerhauptquartier Werwolf near Vinnitsa in Ukraine on September 23, 1942. In the wake of the HALPRO raid, he urged the Germans to take stronger measures regarding the defenses of the Ploesti/Prahova valley refineries. Over the next few months, a political and economic protocol was prepared, finally signed on June 17, 1943, that led to a significant German commitment to the defense of the Ploesti/Prahova valley oil region in return for fuel concessions from Romania. Part of the agreement was that Romania would cede control of the defense effort to the Luftwaffe.

As a result of these discussions, Hitler agreed to halt the reduction of Luftwaffe Flak units in Romania and to begin their expansion. The 5.Flak-Division under Generalmajor Julius Kuderna was assigned to the Ploesti mission in December 1942. It retained a deployment pattern of the previous 10.Flak-Division based around Flak-Regiment.180 and Flak-Regiment.202. The heavy Flak batteries were gradually modernized in 1942–43 with Würzburg fire control radars. These were used to direct the searchlights at night. As more radars were added, they were directly attached to the heavy gun battalions for fire direction. By the beginning of 1943, there were nine Würzburg radar stations in the vicinity of Ploesti. A further six stations were added during the summer of 1943 as part of the modernization of defenses.

To further reinforce the Flak defenses, heavy 105mm and 128mm Flak batteries, mounted on railcars for mobility, were assigned to the area. The Flak trains (Eisenbahn Flak) were

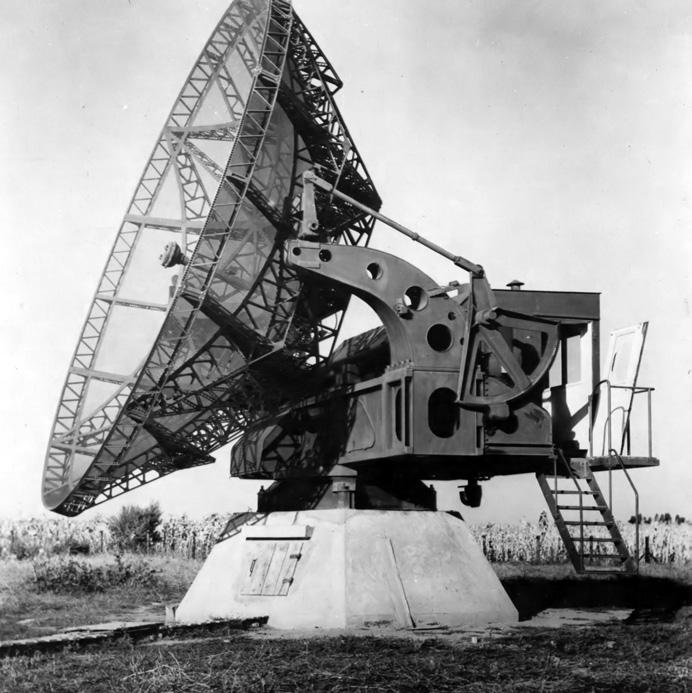

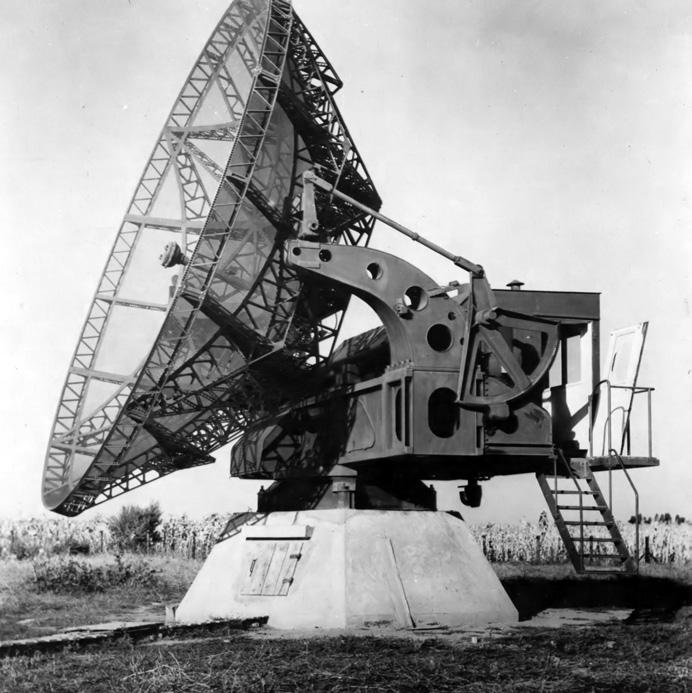

The heavy Flak batteries at Ploesti used the Würzburg gun-laying radar like this one for fire direction.

HUNGARY

SERBIA

OPPOSITE LUFTWAFFE AIR DEFENSE IN ROMANIA 1943:

THE IMPERATOR NETWORK

based at the Crângul Lui Bot railroad station in the Prahova valley and Buda to the northeast of Ploesti.

One of the minor mysteries of the Ploesti defenses was the presence of a Flak train operating along the Câmpina-Ploesti railway line at the time of the Tidal Wave attack. As will be described later, the Flak train engaged the incoming 98th and 44th Bomb Groups. It was called the “Q-Train” in some American accounts, named after German “Q-Ships.”

The bombers’ crews claimed that the train consisted of Flak guns disguised behind false sides, which lowered when going into combat. This actually sounds like normal German Eisenbahn Flak railway cars, which usually had folding sides that were used to give the gun crews a larger work area when operating the guns from stationary positions. However, German Eisenbahn Flak was not designed to operate while on the move. It would be nearly impossible to operate the heavy Flak from a moving train. The American descriptions seem more compatible with a leichte Eisenbahn-Transportschutz-Flak-Abteilung (Light Railway Transport Protection Flak unit) that were used for railway security and generally armed with light Flak cannon. None are known to have been deployed in Ploesti, though it is certainly possible that one was transiting through the area that day. It is also possible that 5.Flak-Division made an improvised light Flak train using available resources. Romanian accounts do mention the German use of 20mm and 13mm automatic cannon on the railways in the Ploesti area. Some accounts refer to this train as “Die Raupe” (The Caterpillar) and indicate that it was commanded by Hauptmann Joseph Brem. Detailed German accounts are lacking.

Romania’s principal indigenous fighter was the IAR 80. These particular aircraft are the IAR 81 variant, designed as fighter-bombers. These were later used in the fighter role and seen here with Escadrila 59 Vt. of the 6 Grupul which took part in the defense of Ploesti in August 1943.

Marshall Ion Antonescu and air force chief Ermil Gheorghiu attend an awards ceremony for Romanian fighter pilots on July 2, 1943. These pilots were veterans of the air campaigns on the Russian Front.

German/Romanian passive defenses in the Ploesti area included static balloons and smoke generators. The Luftwaffe had deployed the Luftsperr-Ballone-Abt.102 to Romania as part of the air defense effort. The standard German barrage balloon was hydrogen-inflated with a capacity of 7,065ft3 (200m3), and was usually flown at an altitude of 6,000–8,000ft (1,800–2,500m). The balloon trailed a steel cable intended to damage or destroy an intruding aircraft. In October 1942, the Luftwaffe turned over responsibility for the barrage balloon barrier to the Romanian 3rd Balloon Battalion (Divizionul 3 Aerostatje). The balloon equipment was deployed in three balloon barriers, one line north of the city, and a double line south of the city. A total of 58 balloons were on hand, but actual operational strength varied. For example, in late July 1943 there were only 18–28 balloons available due to equipment problems, shortage of hydrogen, and a lack of trained crews. On August 1, 1943, a total of 41 balloons were operational.

There was also a static smoke generator battalion with four batteries equipped with a thousand Nebeltopf remotely activated smoke generators to obscure the oil refineries during daylight attacks. These smoke generators were extremely unpopular with the Flak troops since the chemically generated smoke was a serious eye irritant and the smoke obscured the optical fire controls of the Flak batteries.

At the time of the Operation Tidal Wave attack in August 1943, the Ploesti/Prahova valley defenses included 36 heavy Flak batteries with 164 88mm and 105mm guns and 16 light batteries with 210 20mm and 37mm automatic cannon. Of these, the 5.FlakDivision had 42 batteries including five 20mm or 37mm light batteries, 32 88mm heavy batteries, and five 105mm/128mm heavy batteries. It was sometimes claimed that these were the strongest air defenses in Europe, though the Flak commands in Berlin and the Ruhr would have disagreed.

Antiaircraft Artillery in the Ploesti Area, August 1943

5.Flak-Division

Flakgruppe Ploesti

Flak-Regiment.180

Regimentul 7 Artilerie Antiaeriană

Generalmajor Julius Kuderna

Oberst Oskar Bauer

Colonel Gheorghe Turtureanu Flakgruppe Vorfeldschutz

Flak-Regiment.202

Regimentul 9 Artilerie Antiaeriană

Oberst Wilhelm Zabel

Colonel Marius Popeea

PLOESTI’S FIGHTER DEFENSES

Fighter defenses in the Prahova valley/Bucharest area included elements of the FARR (Forţele Aeriene Regale Române – Royal Romanian Air Force) and the Luftwaffe. In general, the Romanian fighter units were assigned the air sector west of Ploesti/Bucharest while the Luftwaffe was assigned the sector to the east.

The FARR deployed four day-fighter squadrons and one night-fighter squadron in the vicinity of Ploesti. Escadrila 45 Vânătoare (45th Fighter Squadron) was part of Grupul 4 while Esc. 61 and Esc. 62 were part of Grupul 6. Two Romanian squadrons were equipped with newer German fighters, the Bf 109G-2 and Bf 110 night fighter, and were based alongside the German squadrons. So they were alternately referred to by German squadron designations. The German pilots were dismissive of the new Romanian Bf 109G squadron and one remarked that: “Most of the Romanian pilots were wealthy boys from the sporty set. They took poor care of their aircraft. Considering how little they flew, they wrecked many Messerschmitts. But every time they got a new one, a bearded Orthodox priest would visit and bless it.” The Germans nicknamed the Romanians flying the smaller IAR 80 fighters as “the Gypsies” and they were regarded as aggressive and daring pilots.

The IAR 80 was an indigenous Romanian fighter that had evolved out of the imported Polish PZL P.24 fighter. It was a low-wing monoplane with a radial engine. A portion of the production had been built in the IAR 81 configuration as a light fighter-bomber. Some of these were modified in 1942–43 by omitting the bomb racks and equipping them with cannon to serve as day-fighters. The text here refers to all versions of this fighter as the IAR 80, though it should be kept in mind that a range of variants took part in the Ploesti fighting.

The Luftwaffe began deploying fighter units to Romania at the beginning of 1941, starting with III./Jagdgeschwader.52 under Maj Gotthard Handrick. The Luftwaffe

A ground crew assists Lt. Mircea Dumitrescu, a pilot of Escadrila 61, Grupul 6 into the cockpit of his IAR 81C.

The pilot of an IAR 80 or IAR 81 waits in the cockpit of his aircraft for the take-off order. The FARR units in the Ploesti area waited on the runway for about three hours on August 1 after having received early warnings from Luftwaffe air defense networks in Serbia and Bulgaria.

fighter force near Ploesti was originally called the Ölschutzstaffel (Oil Defense Squadron). These units saw considerable fighting in the summer of 1941 during the Soviet air offensive against Romania, but after the fall of 1941, it was a quiet sector. Various units rotated through the Ploesti area through 1941–43, some to recuperate and rebuild after the fighting in neighboring Ukraine. By the summer of 1943, the force near Ploesti had been expanded to three day-fighter and two night-fighter squadrons. The most common day-fighter was the Messerschmitt Bf 109G-2, though there were small numbers of the newer Bf 109G-6 in service. The night fighters were primarily Bf 110E and 110F. Gerstenberg believed that the most likely Allied bombing attack on Ploesti would be an RAF night attack, and so he went to considerable pains to build up a night-fighter force. The IV./NJG.4 deployed to Ploesti in the summer of 1943, and was led by a Knight’s Cross night-fighter pilot, Hermann Lütje.

Romanian records indicate that there were 108 fighter aircraft (56 Romanian, 51 German) in the PloestiBucharest area on August 1, 1943. Since it was Sunday, a significant number of pilots and aircrew were away from base at the time of the American raid. As a result, only 57 aircraft (31 Romanian, 26 German) took part in intercepting the American bombers.

Fighter Squadrons in Ploesti Area, August 1943

Unit

FARR

Escadrila 45 Vânătoare

Escadrila 51 Vt. de noapte (12./NJG.6)

Escadrila 53 Vt. (4./JG.4)

Escadrila 61 Vânătoare

Escadrila 62 Vânătoare

Luftwaffe

I/Jagdgeschwader.4

10./Nachtjagdgeschwader.6

11/Nachtjagdgeschwader.6

Aircraft Base

IAR 80

Târgşorul Nou

Bf 110C Ziliştea

Bf 109G Mizil

IAR 80 Pipera

IAR 80 Pipera

Bf 109G Mizil

Bf 110E/F Ziliştea

Bf 110E/F Ziliştea

THE IMPERATOR AIR DEFENSE NETWORK

Luftwaffe forces in Romania were part of a larger network in southeast Europe, and linked together with neighboring commands in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece. One of the most valuable aspects of this network was to provide the various headquarters with early warning of Allied air missions in the region. The Luftwaffe’s Chi-Stelle signals intelligence service monitored Allied air force radio transmissions via a network of radio intercept stations. The stations around the eastern Mediterranean reported to the regional W-Leit Südost command post at Megara near Athens. The station on Crete was primarily responsible for monitoring Allied air force radio channels in North Africa, and had been assigned the task of monitoring the USAAF IX Bomber Command in Libya.

While it has often been claimed that the Luftwaffe knew about the Tidal Wave mission due to decryption of Ninth Air Force radio signals, German accounts suggest that the first warnings of the Tidal Wave mission came from simple radio traffic analysis at W-Leit Südost. In the event, information from the W-Leit Südost station served as early warning to alert the network of radar and observer posts around the Mediterranean and the Balkans when an attack was suspected. Radars of this era had a poor mean-rate-between-failures due to the lack of durability of many of their electronic components. So they were not kept operating on a 24-hour, 7-days-a-week basis. As a result, the radars were only activated when needed. Traditional methods of air early warning were retained including observer posts and some acoustic listening posts.

Beyond the coastal radars, the Luftwaffe had gradually expanded its network of long-range search radars in the Balkans through 1943 on the expectation of Allied bombing missions from North Africa and Sicily. This included stations in Serbia and Bulgaria on the path of the Tidal Wave mission to Ploesti. Information from these stations was passed on to the relevant fighter control centers.

After the June 1942 HALPRO raid, the Luftwaffe began to establish an integrated air defense network in the Balkans which provided early warning of impending bomber attack, monitored Allied bomber missions in the Balkans, and provided radar-directed groundcontrol intercept (GCI) for the fighter force and radar direction for the heavy Flak batteries. This was patterned on the Kammhuber Line in Germany and the Low Countries, though on a much smaller scale. The Romanian network was codenamed Imperator (Emperor), and the radar stations were given Roman names of emperors and historical figures.

The German early warning network in Romania in 1943 consisted of long-range Freya radars with two stationed on the Black Sea coast and a second belt located inland, but also oriented toward potential threats from the Black Sea. Coverage to the north and west was less developed, a gap that would be exploited by the Operation Tidal Wave plan. It is unclear whether Allied intelligence knew of the radar gap to the northwest, or whether it was coincidence that the Tidal Wave route approached via this radar gap.

By the summer of 1943, the Luftwaffe established Jagdfliegerführer (Jäfu) fighter control stations throughout the Balkans. These regional fighter control stations paralleled the Jagddivision (fighter division) command posts used for the defense of the Reich. These stations were able to take advantage of advances in fighter interception technology that emerged in 1943.

Jäfu Rumänien was headquartered at Otopeni air base in the northern suburbs of Bucharest and subordinated to Luftflotte 4. In the immediate area, Jäfu Rumänien was

One form of passive defense used at Ploesti was the dispersal of hundreds of chemical smoke generators around the city to create artificial fog. However, the smoke proved a hindrance to the Flak crews and was not dense enough to obscure the refineries.

The Telefunken FuMG.65 Würzburg-Riese (Giant Wurzburg) radar deployed at Jägerleit Stellung Oktavian located in Săftica. This type of radar was primarily used for ground-control intercept functions as part of the Jäfu Rumänien fighter control network and there were two of these at this site.

supported by two radar stations, Oktavian near Otopeni, and Pompeius, north of Ploesti. These stations had long-range Freya search radars for early warning and Würzburg-Reise radars as height-finders. The I./Nachtrichtung-Regiment.250 in the Ploesti/Bucharest area was responsible for the radar network in the area as well as other elements of the fighter control system. Both day fighters and night fighters were fitted with a transponder that was part of the Y-Führung (Wotan II/Benito) system, a type of radio direction/range system, linked with search radars. This was later followed by the Jägerleit EGON system in 1944. Data from the early warning network was fed to the Jäfu Gefechtstand (battle station) at Otopeni. This data was plotted on a situation map to serve as the basis for a ground-controlled interception process.

Jäfu Rumänien was commanded by Oberstleutnant Bernhard Woldenga but he was on leave on August 1, 1943. As a result, the command center was headed that day by his Ia (chief of operations) Oberstleutnant Douglas Pitcairn von Perthshire. The day-fighter staff was headed by Major Hermann Schultz and the night-fighter staff by Major Werner Zahn. Jäfu Rumänien also controlled the Romanian squadrons via the Romanian fighter control station codenamed Tigrul (Tiger) based at Pipera. Jäfu Rumänien was linked to other Luftwaffe fighter control and radar centers in the region including Jäfu Balkan in Belgrade, Serbia and Jäfu Bulgarien in Sofia.

The Romanian air force had an existing network of passive early warning sites. These consisted primarily of observer posts reinforced by a small number of acoustic listening posts. The two main belts faced the Black Sea and Hungary. In 1942, the Luftwaffe began modernizing this force by providing radio monitoring stations. The first Romanian units

modernized in this fashion were Bateria 286 de pândă radio, stationed in southwestern Romania, and Bateria 282 on the lower Danube. These often proved useful in providing early warning of advancing enemy aircraft, and were linked to the Luftwaffe’s W-Leit Südest signals intelligence network.

The Bulgarian fighter force

The Bulgarski voennovozdushni sili (BVS: Bulgarian Air Force) engaged Tidal Wave both on the inbound and outbound portions of the mission, since the bombers flew over Bulgaria for a portion of the flight. Jäfu Bulgarien in Sofia coordinated the BVS with the Luftwaffe radar and early warning network in the Balkans. The Bulgarian fighters were deployed with the 6th Fighter Regiment (6 iztrebitelen polk) headquartered at Karlovo and divided into three wings (orlyaki) which were in turn each divided into three squadrons (yati). Two of the wings were equipped with the obsolete Czechoslovak Avia B.534 “Dogan” biplane fighter while the third was converting to the new Bf 109G-2 “Strela.” The B.534 were not equipped with an oxygen system, and so their maximum flight altitude was limited.

6 iztrebitelen polk

1/6 iztrebitelen orlyak 612, 622, 632

B.534

2/6 iztrebitelen orlyak 642, 652, 662 B.534

3/6 iztrebitelen orlyak 672, 682, 692 Bf 109G

Karlovo

Bozhurishche

Vrazhdebna

Karlovo

A view of Jägerleit Stellung Oktavian located in Săftica, immediately north of the Oktavian fighter control bunker at the Otopeni air field where Jäfu Rumänien was based. The FuMG.65 Würzburg-Riese air surveillance radar to the left was one of two at the site and was used to locate and track enemy aircraft; the main antenna is folded down in this photo. The Freya-EGON to the right was part of the ground-control interception system, keeping track of friendly fighters via its transponder system. This system was added in 1944.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Sitten haki hän pienestä kaapista istuimensa alta niinikään peltisen teerasian, joka toimitti sokeriastian virkaa, otti kuuman kahvipullon, asettaen sen kainaloonsa, vilkaisi radalle ja sanoi:

"Pane alle!"

Sitten hän taivutti kankean vartalonsa, kunnes kahvi alkoi pulputa pullosta.

"On se työ kahvin arvoinen."

Juotiin, ripustettiin astiat nauloihin jälleen ja alettiin touhuta ylämäessä. Sama äänettömyys, sama asento, sama tyyneys, sama leuan lepääminen rinnalla — näyttipä tilanne miltä näytti. Ja uhkaava se olikin, sillä mahdoton oli saavuttaa enää vauhtia, mikä olisi äsken saatu ilman hankaluutta. Erkki antausi kokonaan Karhulan käskyvallan alle. Hän ei luottanut itseensä nyt. Sitäpaitsi välähtivät mielessä siltapölkkyjen välit, kuin pahan unen muistot heräämisen jälkeen.

Ankara koneen työskentely kulutti puita kovasti. Erkki sai syytää alinomaa, ja ahnaat liekit ahmivat niitä kuin rohtimia. Hiki valui lämmittäjän kasvoilta ja paita oli selässä kiinni vääntömärkänä. Tuntui oikein hyvältä, kun välillä pääsi pikkuhetkeksi tenderiin latomaan uutta pinoa etualalle. Tuuli puhalsi vilpoisesti kosteaan ihoon. Terveenä miehenä hän vielä saattoi nauttia siitä.

Koneisto kävi kaikella mahdollisella voimallaan.

Akkunat tärähtelivät sen iskuista, ilma sihisi ja vinkui luukun rakosissa, kulki ulvoen vetolukkojen kautta läpi valkohehkuisen rovion. Siitä huolimatta hiljeni vauhti alinomaa. Oli tullut muutamien

jännittävien minuuttien, muutamien määräävien kiskonmittojen aika. Mentiin jo niin hiljaa, että olisi pikkujuoksulla saattanut seurata mukana. Oli vaan odotettava, miten kävisi, sillä oli varustauduttu juuri näitä viimeisiä silmänräpäyksiä varten. Mäenharjun yli pääseminen tiesi matkan jatkamista, pysähtyminen takaisin palaamista melkein sinne, mistä oli lähdettykin.

Karhula oli kallellaan lysmäpolvisena, ikäänkuin hän siten olisi tahtonut ainakin ruumiinsa painon siirtää tuolle puolelle kirotun kukkulan, joka tällä tavalla saattoi koetella ihmisen kärsivällisyyttä. Saattoi nähdä, kuinka jotakin hänessä oli aivan kiehumapisteessään valmiina purkautumaan. Ja aivan kuin siihen todellakin tilanteen olisi pitänyt kehittyä, ikäänkuin joku epäilys olisi häntä vetänyt, kumartui hän katsomaan sivuakkunasta. Mutta nyt hän mylvi kuin raivostunut kontio:

"Yh! Menettekös marjailemaan, tuhannen vietävät?" Erkkikin riensi välikköön katsomaan Karhulan raivostumisen syytä. Tornista oli laskeutunut jarruttaja ja noppi jotakin maasta, toinen käveli sivulla ja työnsi muka auttaakseen. Se oli katkera hetki Karhulalle. Hän heristi nyrkkejään avonaisesta ikkunasta ja kirosi, että mäki tärähteli.

"Kömmi tapuliisi!" karjasi hän miehelle, tarttui viheltimen varteen ja antoi pitkän luihauksen merkiksi, että kone oli jo kukkulan harjalla ja palaamisen vaara vältetty.

Ja pianpa taasen alkoivatkin maat aleta ja metsät vilistä. Raskas juna kiisi alas mäkeä kasvavalla nopeudella.

Veturin 375 hytissä ei vallinnut oikea toverisuhde. Erkki sai kokea nöyryytyksen toisensa jälkeen. Karhulan omituisuudet eivät miellyttäneet häntä. Hänessä oli jotakin tavattomasti ärsyttävää, joka kuohutti mieltä. Hänen täytyi hillitä itsessään petoa, joka kiihoitti johonkin kamalaan tekoon, jota hän ei sen tarkemmin osannut määritellä. Ja joka kerta, kun hänen piti tulla yhteen Karhulan kanssa, ahdisti tuo epämääräinen tunne — matkalla, kahden ollessa enimmän. Veturiin astuttuaan olivat he kuin vihityt juuri samallaisiin tehtäviin, joita olivat suorittaneet viikkoja toistensa jälkeen, samoihin asentoihin, samoihin ammattisanoihin. Heidän katseensa kiertelivät höyrykelloon, vesilasiin, radalle. — Toiminta järjestyi niiden mukaan. Kun siinä sitten jostakin syystä rupesi kasvamaan erimielisyys, kääntyivät miesten seljät kuin itsestään vastakkain. Toinen katsoi vasemman olkansa, toinen oikean olkansa yli kumpikin akkunastaan eteensä radalle; siellä etäisyydessä näytti yhtyvän kaksi teräskiskoa, joita myöten heidän veturinsa kolisi eteenpäin. —

Erkki koetti torjua tätä sietämätöntä tilannetta yrittämällä saada keskustelua aikaan, mutta joko Karhula piti sopimattomana tarttua "pojan" tarjoamaan sanaan tai jotenkin tunsi vastenmielisyyttä tällaiseen, Erkin yritys ei onnistunut. Siitäpä alkoi kasvaa peloittava äänettömyys. Erkki ei enään yrittänytkään. Mitäpä siitä, ei kai hän ollut puheita kaupalla. Jos Karhula todellakin piti itseään niin paljon parempana, että katsoi arvoaan alentavaksi käydä keskusteluun, niin eipä suinkaan hän tahtonut häiritä. — Kaikkea muuta hän olisi kuitenkin ennemmin sietänyt kuin tätä. "Onhan Karhula tosin esimieheni, mutta onko mitään syytä käyttää esimiehyyttä tuolla tavalla, kohdella suorastaan halpamaisesti. Millä olen sen ansainnut? Enkö ole tehnyt työtäni säännöllisesti, koettanut kaikin tavoin oppia kunnolliseksi ammattimieheksi, joka kykenisi toimimaan omin päin? Vai onko juuri se Karhulalle vastenmielistä? Pitääkö

minun odottaakin vain hänen käskyään ennenkuin saan mihinkään koskea, toimia kuin joku veivi tai kiertokanki? Ehkäpä hän juuri sitä tahtoo."

Kaikista merkeistä päättäen oli ensi vapaapäivien aikana kattilanpesu. Vesi oli käynyt jo sameaksi, joutui helposti kuohumistilaan, jos kattila oli täynnä ja höyrynmenekki suuri, meni sylintereihin ja teki monellaista kiusaa. Jo monta kertaa oli Karhula kähähtänyt itsekseen, kun sylinterit alkoivat paukahdella. Hän oli riuhtonut auki puhallushanat ja kirota sähissyt hammastensa välistä.

Muuta ei.

"Jos pestään, niin ilmoittakoon, muuten en ole tietääksenikään", päätteli Erkki. "Sanokoon tai viittokoon, mutta nyt minä odotan käskyä."

Tuli vapaapäivä. Ei sanaakaan, kun veturi heitettiin illalla talliin. Erkki oli epävarma; ehkä Karhula oli jotenkin muuten ajatellut.

Erkki nukkui yönsä rauhallisesti, pukeutui aamulla vähän paremmin ja asettui todellakin nauttimaan tästä ainoasta lepopäivästä, mikä heillä oli ajovuorojen välillä. Aamupäivällä hän kuitenkin lähti tallille katsomaan, olisiko mahdollisesti tuotu joitakin määräyksiä ylimääräisellä junalla lähtemisestä. Jo etäältä hän näki, kuinka pilttuun ovi oli auki, työ parhaassa käynnissä: Karhula pesemässä kattilaa siivoojapoikain kanssa. Lattialla kierteli vesiletku, puhdistusreijistä juoksi likainen vesi koneen alle kanavaan. Karhula itse ohjasi suihkua, kuten tavallisesti, pää kallellaan, leuka rinnalla, märkänä ja likaisena. — Ei silmäystä, ei sanaa. Paine nousi molempien mielissä.

Erkki oli aivan suunniltaan palatessaan tallilta. Häntä harmitti tuollainen menettely. Eikö hänellä ollut suuta sanoa? Vai tahtoiko hän kaikkien silmissä heittäytyä poloiseksi, jonka piti yksin raataa likaisessa työssä, silloin kuin lämmittäjä käveli pyhäpukuisena.

Mutta Erkki ei voinut puolustaa omaakaan menettelyään. Olisi kai ollut hänen velvollisuutensa nuorempana kysyä. — Olisiko todellakin? — Rauhaa ei tullut. Uhkamielinen hän oli ollut, mutta oliko syytä matelemiseen. — "Jos menisin hänen luokseen ja tekisin kerrankin puhdasta jälkeä, puhuisin tyyneesti — tai riitelisin, jos se olisi parempi. Loppu tästä vain pitää tulla, tulkoon sitten miten tuleekin." Mielessä pysähteli, jalat veivät pois päin. Hän karkoitti huonot tuulet ja syventyi lukemalla kuluttamaan aikaansa. — "Kerkiääpä tuollaisia munia hautoa pesän lämpymässäkin."

Lähdettiin matkalle taasen, elettiin yhdeksänvuorokautinen ajo. Mäkeä ylös, alas, eteen, taakse, mutkasta mutkaan, halki kylien, keskellä ihanasti hymyilevän kevätkesän luonnon. Hymyttömin huulin. Syvä äänettömyys: "mökön turkkia paikattiin."

Erkki ei voinut enää entiselläkään huonolla tyyneydellä ottaa vastaan Karhulan luukkuihin ja vedensyöttölaitoksiin kajoamista. Jokainen sellainen teko tuntui kuin ruoskan sivallukselta ympäri kasvoja, ja hän puri hampaansa yhteen, mielessä katkera uhka: vielä kerran tämä laukeaa ja silloin…

Mutta eräs tapa ei ollut tänäkään aikana jäänyt Karhulalta pois: suuren kahvipullon yhteisesti tyhjentäminen. Erkin oli vaikea ymmärtää tätä. Ensimäinen kuppi juotiin Tiperon vahtituvan seutuvilla, mäen korkeimmalla huipulla. Olipa paikkaa vähitellen ruvettu kutsumaan Knorrimäeksi, sillä siinä myöskin kuljettaja Sirola

säännöllisesti teki puolikuppisensa. Toinen juotiin Ojakylän tornilta lähdettyä. Samat paikat sopivat paluumatkallakin..

Mutta Erkkiä olivat alkaneet nämä juottelut kiusata. Mitä hän sitä tyrkytteli, joisi itse. Ensin ylimielinen kohtelu, sitten kahvikuppi, aivankuin piiskatulle lapselle piparikakku. Hän oli jo kauvan hautonut mielessään mitä tehdä, nakatako kahvi Karhulan eteen lattialle vai kieltäytyä siivosti ja kohteliaasti.

Noustiin Tiperon mäkeä, kattilassa ankara paine, koneella ankara työ, "hännässä" valtava paino.

Oltiin juuri pääsemässä vastamäestä, ja kun ei ollut erikoista syytä epäillä nousun onnistumista, otti Karhula jo kaapista sokeriastiansa.

Erkki kuuli sokeripalojen kalinan, kannen aukeavan, sillä koneen jyrinään tottunut eroittaa pienenkin äänen, joka on siitä poikkeava, nyt pullon kilisemisen hanojen metalleihin. Juuri silloin alkoi alamäki, ja hänen oli käännyttävä hoitamaan vedensyöttölaitoksia.

Pullo oli jo Karhulan kainalossa. Nyt viittasi hän katonrajassa koukussa olevaa astiaa. — "Ota!" sanoi katse.

Erkki otti sen vastenmielisesti, mielessä: en juo. Siitäpä syystä hän tarttuikin pohjasta, heittäen korvan vapaaksi Karhulaa kohti.

Nyt jo pulppusi kahvi, kuumentaen sormenpäitä. Erkki ei liikauttanutkaan kättänsä. Karhula katsoi pitkään ja viittasi käyrällä sormellaan sokeriastiaa kohden. Erkki ei ottanut, vaan sanoi sen sijaan: "Ottakaa joutuin, polttaa sormiani!"

Karhulan silmät iskivät tulta. Kokonaan käsittämätön oli se mylvähdys, joka läksi pullistuneesta rinnasta. Samassa silmänräpäyksessä kuului jymähdys: Karhulan korko iski avainarkun kanteen.

"Juo!"

Ja Erkki joi.

Hän ei uskaltanut olla sitä tekemättä. Hän joi vapisevin käsin, kyyneleet silmissä, katkerin mielin, vihassa ja kiukussa, joi ja puhkesi puhumaan.

Veturi kiisi kuin riivattu rinnettä alas aivan kuin sekin olisi juonut jonkun hulluksi tekevän pisaran. Karhula repi vuoroin viheltimiä, vuoroin höyrynsulkijaa. Vaunut paiskautuivat kiskoilla, jarruttajat huojuivat torneissaan, sinkoillen seinästä toiseen, kauhistuen kamalaa vauhtia. Varaventtiilit puhalsivat pois kattilan liikaa painetta, joka oli kohonnut huomaamatta riidan aikana. Niin kiisi juna kähisten ja kiskojen liitekohtia hakaten halki metsän kuin saalistaan takaa ajava ärsytetty eläin. Oli onni, ettei ketään sattunut tielle…

Erkki potkasi ilmaluukun kiinni. Varaventtiilit alkoivat vähitellen sulkeutua. Tuli vihdoin aivan tyventä. Kuului vain avatusta pesästä tukahdutettu, nopea huounta. Juna vieri samalla painollaan nopeuden yhä kasvaessa…

Ne olivat kauheat kilometrit, jolloin satoi purevia sanoja niinkuin hauleja kummaltakin puolelta. Mutta tämä ei ollut mikään hävittävä räjähdys, vaan oikeita teitä purkautuva liikakuormitus. Kumpikin pohjimmaltaan kaipasi sovintoa ja se siitä vähitellen rupesi muodostumaankin. Tyynnyttiin, rauhoituttiin sekä käytiin

avomieliseen keskusteluun, tunnustettiin, kuinka oli kyllä vika toisessa huomattu, mutta ei niinkään itsessään. Karhula sanoi monta kertaa hermostuneensa niin kovasti, että hänellä oli ollut täysi työ pidättää itseään kiinni tarttumasta, ja Erkki syytti nuoren mielensä intoa ja harkitsemattomuutta. Ja mitä pitemmälle he tulivat, sen sovinnollisemmalta tuntui. Karhula sanoi sanottavansa katkonaisin, takertuvin lausein, otti loppujen lopuksi pullonsa, asettaen sen kainaloonsa. Ei oltukaan ennen juotu tällaisin mielin…

3 Muutamia vuosia tekeillä ollut Norvamon rata pohjoisessa oli aivan äsken valmistunut. Liikkeen avaaminen aiheutti paljon muutoksia rautatien henkilökunnassa. Tarvittiin suuri joukko virka- ja palveluskuntaa. Tässä muutoksessa tuli Erkki Teräksestä vanhempi veturinlämmittäjä, ja kaikesta päättäen hänen kuljettajaksi nimityksensä ei ollut kaukana. Siihen hän olikin jo täysin valmistunut sillä viime talvena oli hän käynyt veturinkuljettaja-kurssin Helsingissä. Näiden nimityksien aikana oli hänestä tullut kuljettaja Sirolan hyttitoveri.

Tämä oli Erkkiä vanhempi mies, mutta siitä huolimatta nuortea ja reipas. Kaiken iloisuuden ja avomielisyyden ohessa oli hänessä kuitenkin paljon itseensä sulkeutunutta. Oli joitakin kammioita, joihin kukaan ei ollut päässyt katsomaan. Toisinaan valtasi hänet kiivas himo väkijuomiin. Saattoi mennä vuorokausia, jolloin hän ei erikoisesti näyttänyt niitä haluavan, mutta sitten taasen ryöstäysi himo valloilleen, ja hän oli kuin mennyttä miestä. Omituista kuitenkin

oli, että vaikka hän olikin tällä tavalla poissa suunniltaan, tehtävänsä hän siitä huolimatta suoritti nuhteettomasti.

Erkistä oli aina tuntunut raukkamaiselta, että miehet huolensa ja murheensa upottivat lasiin. Hänen oli paha olla nähdessään toverinsa toisinaan juovuksissa. Vaikka Sirola oli silloin erinomaisen hauska toveri, olivat nuo matkat kuitenkin ikävimpiä. Sen hän sanoikin suoraan hänelle.

Sirolalla oli omituisia tottumuksia. Tuskinpa hän enää pääsi Knorrimäen yli puolikuppisetta, ja turmiollisinta oli, ettei hän voinut tehdä matkaa pohjoiseen rajakaupunkiin saamatta "rajantakaista".

Hän oli jo itsekin alkanut tuota kammoksua. Raja kiusasi häntä, ikäänkuin sen takana olisi asustanut kiehtova paholainen, joka lopullisesti oli hänet nielevä kitaansa. Hän oli toisinaan näkevinään rajapyykin kiven vieressä tuhansilla tavoilla nauravan naamaan, ja hän niin hyvin tiesi, mitä se merkitsi: niin pitkällä siis jo oltiin.

Enempi kuin Sirola aavistikaan huolehti Erkki hänestä. Oli aivan kauheaa, että mies tällä tavalla vajosi vajoamistaan. Erkki aivan pelkäsi pohjoisen radan ajovuoroja, eikä ollut koskaan varma, kuinka ne päättyisivät. Saattaisihan Sirola jolloinkin jäädä sinne pitemmäksi aikaa, ohi lähtöajan, tai muuten tulla kykenemättömäksi tehtäväänsä.

Miten silloin selviydyttäisiin? Mutta miten saada hänet pysymään poissa sieltä?

Erään kerran, kun taas oltiin rajalla, ehdoitti Erkki Sirolalle:

"Ei suinkaan sinun ole välttämätöntä mennä itse sinne, laita joku noutamaan."

Kun Sirola epäröi, jatkoi hän:

"Odota täällä, niin minä käyn."

Merkillisen helposti Sirola taipui, ja siitä Erkki ymmärsi hänen ehkä itsekin pelkäävän pahinta.

Näin tämä asia toistaiseksi korjaantui ja ilman mitään erikoisempaa kuukaudet kuluivat. Oli syksy taasen. Erkki oli yhdellä noista inhoittavista matkoista: tulossa rajan takaa konjakkipullo taskussaan. Hän käveli hitaasti sateen liottamia katuja.

"Sinä tulit jo! Saitko?⁰

"Mieluummin olisin tullut tyhjänä.⁰

"Älä, älä!"

Sirolan kasvoilla oli hymy, joka jo kuului hänessä asuvalle paholaiselle. Erkkiä inhotti. Sirola piti silmällä Erkin takkia ja otti vastaan pullon vapisevin käsin. Kurkusta kuului nieleskelemisen korina.

"Hyvä ystävä, älä juo nyt. Älä ainakaan noin paljon!" pyysi Erkki.

Sirolan huulet vavahtivat.

"Anna pullo minulle!" Erkki koetti saada äänensä sydämelliseksi. "Ota siitä jollakin toisella kerralla, jolloin olet levollisempi. Anna tämä nyt minulle!"

Sirola istui alasluoduin katsein, ja Erkki jatkoi:

"Tämän pyynnön teen sinulle ystävänä, jolle ei ole aivan yhdentekevää, juotko sinä tai et."

"Vie!" tuli kuin tuskan parahdus, mutta käsin piteli hän edelleenkin lasista kiinni. "Ei, salli edes tämä lasi!"

Hän joi sen ahmien kuin janoinen eläin, ja Erkki riensi pullon kanssa ulos. Ensi ajatuksensa oli lyödä se rikki rakennuksen kivijalkaan, mutta hän uskoi sentään asian selviytyvän ilman sitäkin, vei pullon omaan kaappiinsa ja pisti avaimen taskuunsa.

Mutta Erkki sai kokea, kuinka turhia kaikki keinot olivat.

He olivat silloin Kunnaan päivystyshuoneella odottamassa kotiinpäin lähtöä etelästä tulevalla matkustajajunalla.

He olivat kumpikin matkastakin väsyneitä, sillä he olivat tuoneet yöjunaa, saapuen Kunnaaseen kahden aikana aamulla. Keskipäivällä oli Erkki vielä nakkautunut päivystyshuoneen rautasänkyyn ja nukahtanut. Herättyään läksi hän talliin kunnostamaan konetta. Sirola istui hytissä tukkihumalassa. Hän oli murtautunut Erkin kaappiin ja juonut pullon melkein tyhjäksi. Erkki tarttui työhönsä ääneti miettien, kuinka olisi nyt meneteltävä, sillä Sirolan ollessa noin ylimmillään oli oltava varovainen.

Syksyinen iltapäivä alkoi jo hämärtyä ja puolipimeän tallin vielä pimeämmässä veturihytissä istui juopunut mies synkkänä ja äänettömänä.

"Jopa annoit lähdön rajantakaiselle," sanoi Erkki huolettoman leikillisesti.

Sirola naurahti tuskin kuultavasti, josta Erkki huomasi oikealla tavalla alkaneensa.

"Perhana vieköön! Mitäs Knorrimäessä? Vettäkö tenderistä?"

"Vasikka!" hönkäisi Sirola.

"Niin juuri, vettä ynisevä vasikka sinä olet, ellet anna pulloa tänne. Loppu Knorrimäessä."

Sirola katsoi väsynein, toljottavin silmin, niinkuin ei olisi heti ymmärtänyt mitä hänelle sanottiin.

"Mitä hittoa minä työnnän kitaani asumattomalla mäellä, ellei minulla ole tinakaulaa kaapissani? Vai luuletko sinä näitä useampia olevan? Ja jos olisi ollutkin, niin kyllä kai sinä olisit ne imenyt."

Sirolassa heräsi epäilys, ja hän tutki tarkoin, minkäverran pullossa vielä oli, käänteli ja katseli sitä vesilasin rasvalampun valossa.

"Ei siitä ole varaa ottaa ollenkaan."

Erkki tarttui pulloon vetääkseen sen pois, mutta Sirola piti sitä lujasti kiinni.

"Kelvoton! Minä lukitsen kaapin ja koetan siten säästää sinulle kunnollisen iltaryypyn vastamäessä, niin sinä kehtaat murtautua ja saada tällaisen häpeän aikaan. Mihin tästä nyt enää on? Silmän voiteeksi!"

Erkki ajatteli kauhulla, mihin tämä olisi päättyvä. Sirola oli juonut huimaavan paljon. Pullo täytyi saada pois ja siten viimeiset ryypyt siirretyksi lähemmäksi kotia. Hän laski matkaa, mikä oli Knorrimäestä Oulankaan. Onneksi ei tarvinnut ottaa puita sillä välillä. Ei hän oikein tiennyt, mistä syystä teki noita laskelmia. Ne vain tulivat mieleen. Saatuaan vihdoin houkutelluksi pullon Sirolalta pani hän sen kaappiinsa, mutta katsoi sitä tehdessä, mitä muuta sinne oli kertynyt aikojen kuluessa: tivistelankakerä, vyyhti sormenvahvuista

männänvarren tivistettä, trasseleita, ruuveja, muttereita… pala köyttä — mitähän lämmittäjä Nevala sillä oli tehnyt?

Hytissä vallitsi alkumatkasta äänettömyys. Ulkona oli puhjennut myrsky. Sade pieksi hytin akkunoita ja salamat välähtelivät taivaalla.

— Erkillä ei ollut syytä epäillä, ettei Sirola tekisi tehtäväänsä, vaikka hän katsoikin eteensä elottomin silmin ja puoleksi makasi suunnanvaihtajan yli. Kädet kuitenkin toimivat tottuneesti kuin määrätyt koneenosat. Kuten tavallisesti juopottelutuulella ollessaan oli hän nytkin enimmän kiusautunut, jos joku seikka asemilla myöhästytti. Siitä syystä oli vauhti hyvä ja he pyrkivät tulemaan asemille ennen määräaikaa.

Niin mentiin halki kylien ja lakeuksien, vinosti vasten painavaa itätuulta, keskellä säkkipimeyttä. Vaunun akkunain tulet luikertelivat tiepuolessa, mättäissä, kivissä ja ojan reunoissa, lyheten, pideten, vääristellen ja tuuli repi höyry- ja savupilviä junan sivulla.

"Piru!" kirkaisi Sirola yht'äkkiä kamalasti, ja Erkki tunsi kylmän väreen karahtavan seljässään.

"Mitä?" kysyi hän niin rauhallisesti kuin suinkin.

"Käyntisillalla, nokikaapin vieressä."

Erkin jäsenet vavahtelivat, mutta hän astui kuljettajan puolelle katsoen muka hänkin ulos.

"Kas vaan, eikö olekin!"

"No, onpa siinäkin 'pasiseerari‘!" jatkoi hän tietämättä mitä sanoa.

Sirola ratkesi nauramaan; se kuului kamalalta tällä hetkellä. —

"Iloinen piru!" — Hän nauroi jälleen.

"Miten niin?"

"Tanssii kuin kone roudan nostamalla radalla… ylös, alas… ylös, alas… noin, noin…"

Ja tietämättä taasenkaan mitä teki, sanoi Erkki:

"Annetaan tahtia sille." Hän alkoi viheltää, vaikka huulensa eivät tahtoneet pariksi sopia.

"Pa— pane puita… täyteen… Me annamme kyytiä sille. Ja anna pullo myös!"

Erkki oli toivonut, ettei hän sitä enää muistaisikaan, mutta huomasi erehtyneensä. Nyt oli mentävä mukaan niin pitkälle kuin suinkin. Hän antoi pullon, johon toinen tarttui kiihkeästi.

"Maljasi, herra Eerikki!" huusi Sirola, sitten hän nosti pullon suullensa ja tyhjensi sen yhdellä siemauksella sekä heitti ulos akkunasta.

Nyt he olivat juuri menossa Paavelan ja Tauvon välisellä kolmipenikulmaisella taipaleella asumattomien kangasmaiden yli, kiipesivät Knorrimäen rinnettä ylös, tai oikeammin kiisivät, minkä kone eteensä otti. Miten oli päättyvä tämä, sitä ei Erkki osannut ajatella, sillä hän eli sanan varsinaisessa merkityksessä silmänräpäyksen kerrallaan. Hän ei kääntänyt hetkeksikään selkäänsä, vaan oli joka silmänräpäys valmiina tarttumaan toveriinsa, jos se olisi tarpeellista. Onneksi kuitenkin Sirola istui

paikallaan, etukumarassa suunnanvaihtajan yli, hullu katse suunnattuna ulos.

"Vihellä niille perkeleille!"

Ei koskaan ollut Erkistä pesä laulanut niinkuin tänä myrskyiltana. Iskujen yhtämittainen kaiku metsässä oli kuin saatanallisen naurun kieriskely korven pimeydessä. Ja kun pesän vihertävänkeltainen kirkkaus huikaisi hänen silmänsä ja saattoi ulos pimeyteen katsoessa tulipallot leimuamaan silmissä, näyttivät ne paholaisen silmiltä mustassa yössä…

Nyt saavuttivat he Knorrimäen huipun ja juna alkoi laskeutua alas, mutta Sirola ei kai huomannut sitä eikä vähentänyt koneen tehoa. Kauhulla katsoi Erkki häntä. Eikö hän todellakaan enää tiennyt mitä teki? Vauhti lisääntyi nopeasti.

"Siinä sivuutettiin mäen harja," sanoi hän, saadakseen Sirolan huomaamaan, missä oltiin.

Sirola tuijotti tylsänä eteensä…

Mitä tehdä nyt? Hänellä ei ollut oikeutta puuttua esimiehensä tehtäviin, mutta mitä seuraisi, jollei yhä kiihtyvää vauhtia pienennettäisi. Nyt jo alkoi veturi heittelehtiä kiskoilla. Pesä ei ulvonut niinkuin vastamäen kiihkeässä ponnistuksessa, vaan läähätti, nyyhki kuin suuri ihmisjoukko olisi tukahdettua itkua itkenyt…

"Nyt on suljettava höyryventtiili!" sanoi hän päättävästi.

Kun Sirola ei vastannut, sulki hän sen. Mutta silloin Sirola kohosi asennostaan ja hänen silmänsä leimahtivat heikossa valossa, joka

peitetyn kattolampun kupuun leikatun raon kautta lankesi hänen kasvoilleen.

"Anna olla auki sen!" karjasi hän ja repäsi venttiilin selälleen.

"Me menemme kohti kuolemaa!"

"Antaa mennä — heee—i!"

Se oli mielipuolen karjaisu, joka saattoi Erkin vapisemaan.

"Ajattele, hullu ihminen: junallinen matkustajia…"

"Vihellä niille, vihellä sen…!"

Mutta nyt painoi Erkki uudestaan venttiilin kiinni. Tästä raivostui

Sirola, hyökkäsi ylös, ja Erkki näki jotakin vilahtavan hänen kädessään. Samassa hän kuitenkin oli kiinni Sirolan ojennetussa kädessä ja tavattomalla voimallaan, joka tällä epätoivoisella hetkellä vaan kasvoi, sai hän väännetyksi kouran auki. Akkuna helähti ja avonainen veitsi lensi ulos. Syntyi hetken kestävä kiivas kahakka. He kiersivät molemmat nyyhkivän pesän edessä. Sirola oli vahvarakenteinen mies, mutta kuitenkin hän herpaantui, ja Erkki sai hänet nujerretuksi lämmittäjän puolelle kattilan ja seinän väliin. Kiivaalla otteella oli hän samassa kiinni jarruventtiilissä, ja junan vauhti alkoi vähetä. Oli jo aikakin, sillä pian alkoi Isonkaaran laskeutuma, jonka alla oli tiessä mutka. Sitä ajatellessa ja vielä äskeisestä ottelusta järkkyneenä täytyi Erkin tukea itseään akkunan pielukseen ja nojata istuimen kulmaan. — Nopeusmittarin viisari hamuili ennen kulkemattomilla alueilla. Hiki virtasi pitkin Erkin ruumista, mutta tällä järkyttävällä hetkellä häntä kuitenkin elähdytti tieto, että vaara oli vältetty. Oli vain saatava Sirola tyyntymään.

Tämä yritteli vielä ylös, kirosi kamalasti, haki housuntaskuistaan jotakin, mutta käsi jäi taskuun ja mies raukesi vähitellen. Ja kappaleen ajan kuluttua kuului ainoastaan örähtelyä… yhä vaisummasti…

Juna saapui Tauvoon. —

4

Näihin aikoihin sai Erkki kirjekortin, johon oli kirjoitettu joustavalla käsialalla: "Olen päässyt Norvantoon. Et usko, kuinka olen iloinen. Irja." — Erkki kirjoitti lyhyesti vastaan: "Tervetuloa!"

Tuo kortti toi mieleen omituisia, valoisia muistoja. Irja, lapsuuden ystävä Tauvosta! Koko heidän monivuotinen, usein katkeillut ja epämääräinen suhteensa, jota hän ei ollut itselleenkään selvittänyt, sukeltausi muistiin. Ja sydän sykki voimakkaammin tapaamisen toivosta.

Erkki otti usein esille Irjan kortin ja katsoi sitä pitkään. Olipa siellä tyttö riemuissaan. Ja olihan siitä räiskähtänyt pieni pisara tännekin.

Miksi oli hän siihen ollenkaan vastannut? Ensi vaikutuksesta kohta, ja olikin se vilpitön tervetuloa. Puuttui vain, että olisi sen saanut kädestä pitäen sanoa.

Eräänä päivänä, ollessaan toimestaan vapaana, meni Irja asemalta postia noutamaan.

Postijunan kuljettajana oli Erkki. Hän oli huomannut Irjan ja tuli alas veturista rientäen luokse.

"Joko sinä olet täällä!"

"Niinkuin näet. Missäs sinä olet ollut, kun ei ole täällä näkynyt?"

"Eteläisellä rataosalla, olen nyt pitkästä kotvasta täällä. — Siis sinä olet tullut." — Erkin äänessä soi hillitty riemu. — "Toivon sinun viihtyvän täällä paremmin kuin Kouvolassa."

Erkki oli muuttunut edukseen sitten viime näkemän. Hänen käytöksessään oli entistä enemmän itsetietoisuutta ja varmuutta, oli vähän laihtunutkin ja silmät syventyneet, mutta kasvoilla kuvastui lujuus ja päättäväisyys. Ja kuinka hän katsoi sieltä korkeudesta.

Irjasta tuntui kuin olisi se aivan kohoksi nostanut. Miten komea! Häntä puki erinomaisesti uusi kuljettajanlakkinsa, joka oli edestä ylös kohonneena ja teki hänet niin erinomaisen reippaan, iloisen ja avomielisen näköiseksi. No, hän tiesi, miten sitä piti pitää päässä.

Erkki viivähti tuskin paria minuuttia, tarttui kädestä ja sanoi:

"Näkemiin. Minä tulen pian."

Samassa oli hän poissa.

* * * * *

Irja käveli malttamattomana asemasillalla. Minuutit kuluivat hitaasti. Viisari valaistussa kellotaulussa asemahuoneen seinällä näytti toisinaan pysähtyneen. Myrsky mylvi puistossa. Kaasulyhty huojui tuulessa, suhisi ja näytti toisinaan sammuvan. Vihdoin läpäsi lumiryöpyn veturin valo ja kinoksia kahlaten vyöryi pikajuna asemalle. — Irja käveli asemasillalla samaan suuntaan.

"Hyvää iltaa!" kuului ylhäältä veturihytistä. Ääni tuli pehmeänä ja lämpöisenä.

Samassa oli koliseva, lumikinosten peittämä veturi ohi ja pysähtyi asemalaiturin päähän. Irja saavutti sen sieltä. Erkki oli laskeutunut alas ja nosti lakkiaan.

"Niinhän sinä kuljet kuin lumivuoren sisällä", sanoi Irja.

"Me olemmekin kyntäneet halki kinoksien, eikä ole kumma, jos niitä onkin vielä osa niskassamme."

"Mitähän, jos jäitkin välille," kiusotteli Irja.

"Eläpäs! Sitäkö sinä toivoit täällä?"

"Sitä!" — Irja nauroi käsipuuhkansa takaa.

"Vai niin! Mutta minä tulin kuitenkin."

"Ja nyt minulla on sinulle eräs ehdotus: sopisiko sinun tulla luokseni tänä iltana?"

"Onko sinulla joku merkkipäivä?"

"Ei, muuten vain. Eräs tuttavani täältä, neiti Lillström tulee myöskin. Se johtui äsken mieleeni, kun tiesin sinun olevan tänne tulossa ja on tällainen huono ja kylmä ilma…"

"Kiitoksia ystävyydestäsi! Kutsuasi et olisi siltä kannalta katsoen voinut paremmin asettaa. Sillä suoraan sanoen: lämmin kahvitilkka ei nyt tee pahaa."

"Sen arvasin."

"Tulenko heti, kun joudun?"

"Tule vain."

Saavuttuaan asuntoonsa riisui Irja nopeasti päällysvaatteensa ja haki puita säiliöstä pannakseen pesään.

Kohta räiski iloinen tuli uunissa ja sen loimussa järjesteli Irja huonettaan ja iloitsi jokaisesta siirrosta, joka somisti sitä. Hymy kaunisti hänen kasvojaan tällä hetkellä.

Hän ei tahtonut kieltää itseltään, että todella odotti Erkkiä. Hän hymähti maltittomuudelleen, mutta samassa vakasivat viime tapaamisien muistot hänet ja hän palautti ne toisen toisensa jälkeen… * * * * *

Nyt hän tuli, kun pystyvalkea oli iloisimmilleen kerjennyt.

"Neiti Lillström ei ole tullut vielä. Hänellä lienee joku este. Mutta voinemmehan odottaa kahdenkin?"

Heidän katseensa yhtyivät…

* * * * *

"Kummallinen on ihmisten elämänjuoksu," puheli Erkki kuin äänellään tarttuen johonkin mielessään kulkevista ajatuksista. "Jos jäisi jotakin näkyvää jälkeä, viivat tai jotakin sellaista, joka tehtyä matkaa kuvaisi, niin saisimme niistä nähdä, kuinka polkumme risteilevät."

"Aluksi ne kuitenkin kulkisivat yhdessä."