Primitive Sublime 1st Edition Maria Mcgarrity

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/modern-irish-literature-and-the-primitive-sublime-1stedition-maria-mcgarrity/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Modern Irish Literature and the Primitive Sublime 1st Edition Mcgarrity

https://textbookfull.com/product/modern-irish-literature-and-theprimitive-sublime-1st-edition-mcgarrity/

Modern Death in Irish and Latin American Literature

Jacob L. Bender

https://textbookfull.com/product/modern-death-in-irish-and-latinamerican-literature-jacob-l-bender/

Irish Urban Fictions Maria Beville

https://textbookfull.com/product/irish-urban-fictions-mariabeville/

Roots of Lyric Primitive Poetry and Modern Poetics

Andrew Welsh

https://textbookfull.com/product/roots-of-lyric-primitive-poetryand-modern-poetics-andrew-welsh/

Imagining Irish Suburbia in Literature and Culture

Eoghan Smith

https://textbookfull.com/product/imagining-irish-suburbia-inliterature-and-culture-eoghan-smith/

Irish Traveller Language: An Ethnographic and FolkLinguistic Exploration Maria Rieder

https://textbookfull.com/product/irish-traveller-language-anethnographic-and-folk-linguistic-exploration-maria-rieder/

Masculinity and Identity in Irish Literature Heroes

Lads and Fathers 1st Edition Cassandra S Tully De Lope

https://textbookfull.com/product/masculinity-and-identity-inirish-literature-heroes-lads-and-fathers-1st-edition-cassandra-stully-de-lope/

Masculinity and Identity in Irish Literature Heroes

Lads and Fathers 1st Edition Cassandra S Tully De Lope

https://textbookfull.com/product/masculinity-and-identity-inirish-literature-heroes-lads-and-fathers-1st-edition-cassandra-stully-de-lope-2/

The Palgrave Handbook of Early Modern Literature and Science 1st Edition Howard Marchitello

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-palgrave-handbook-of-earlymodern-literature-and-science-1st-edition-howard-marchitello/

Modern Irish Literature and the Primitive Sublime

Modern Irish Literature and the Primitive Sublime reveals the primitive sublime as an overlooked aspect of modern Irish literature as central to Ireland's artistic production and the wider global cultural production of postcolonial literature. A concern for and anxiety about the primitive persists within modern Irish culture. The “otherness” within and beyond Ireland's borders offers writers, from the Celtic Revival through independence and partition to post-9/11, a seductive call through which to negotiate Irish identity. Ultimately, the disquieting awe of the primitive sublime is not simply a momentary recognition of Ireland's primitive indigenous history but a repeated rhetorical gesture that beckons a transcendent elation brought about by the recognition of the troubled, ritualistic and sacrificial Irish past to reveal a fundamental aspect of the capacity to negotiate identity, viewed through another but intimately reflective of the self, within the long emerging twentieth-century Irish nation.

Maria McGarrity is a professor of English at Long Island University in Brooklyn, New York. She has been published in journals including the James Joyce Quarterly, Ariel: a Review of InternationalEnglish

Literature, CLA Journal, and The Journal of West Indian Literature. She has published two monographs, WashedbytheGulfStream:the Historic and Geographic Relation of Irish and Caribbean Literature (Delaware, 2008) and Allusions in Omeros: Notes and a Guide for Derek Walcott's Masterpiece (Florida, 2015) and two co-edited collections, Irish Modernism and the Global Primitive (Palgrave, 2009) and Caribbean Irish Connections (University of the West Indies Press, 2015).

Routledge Studies in Irish Literature

Editor: Eugene O’Brien

MaryImmaculateCollege,UniversityofLimerick,Ireland

Seamus Heaney's American Odyssey

EdwardJ.O’Shea

Seamus Heaney's Mythmaking

EditedbyIanHickeyandEllenHowley

Irish Theatre

Interrogating Intersecting Inequalities

EamonnJordan

Reading Paul Howard

The Art of Ross O’Carroll-Kelly

EugeneO’Brien

Wallace Stevens and the Contemporary Irish Novel

Order, Form, and Creative Un-Doing

IanTan

The Art of Translation in Seamus Heaney's Poetry Toward Heaven

EdwardT.Duffy

Masculinity and Identity in Irish Literature

Heroes, Lads, and Fathers

CassandraS.TullydeLope

Modern Irish Literature and the Primitive Sublime MariaMcGarrity

For more information about this series, please visit: www.routledge.com/Routledge-Studies-in-Irish-Literature/book-series/RSIL

Modern Irish Literature and the Primitive Sublime

First published 2024 by Routledge

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158

and by Routledge 4 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprintofthe Taylor &Francis Group, an informa business © 2024 Maria McGarrity

The right of Maria McGarrity to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademarknotice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

ISBN: 978-1-032-28556-6 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-032-28558-0 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-003-29739-0 (ebk)

DOI: 10.4324/9781003297390

Typeset in Sabon by KnowledgeWorks Global Ltd.

Acknowledgments

1 Introduction: Modern Ireland and the Primitive Sublime

2 Performing the Primitive Sublime: The Celtic Revival and Irish Indigeneity

3 James Joyce and the Primitive Sublime: From APortraitofthe ArtistasaYoungManto Ulyssesand FinnegansWake

4 Mid-century Malaise and Desublimation in Samuel Beckett, Flann O’Brien, Kate O’Brien, and Edna O’Brien

5 The Living Dead: The Late Century Resurgence of the Primitive Sublime in Works by Seamus Heaney, Eavan Boland, and Brian Friel

6 Primitive Sublime Terror: Writing New York after 9/11 in Joseph O’Neill, Colum McCann, and Colm Tóibín

Index

Acknowledgments

This book is the product of many years of research and scholarly conversation whether at conferences, archives, or seminar rooms. For all of those folks who aided along the way, please know that I continue to appreciate every opportunity for insight, discussion, and exchange. I wish first to thank my home university, Long Island University in Brooklyn, New York, for several research and travel grants. Especially important was the support I received from the LIU Office of Sponsored Research then under the direction of Anthony DePass. Provost and VPAA Gale Stevens Haynes found means of funding me for many a conference after which I always managed to find a week or two of work in an archive from the National Library of Ireland and the British Library to the Muséeduquai Branlyand the BibliothèquenationaledeFrance. The U.S/U.K Fulbright Commission was central to the completion of the book thanks to my Fulbright award in Irish Literature at the Seamus Heaney Center for Poetry, Queens University Belfast. Glenn Patterson, Rachel Brown, and indeed everyone created an atmosphere of welcome at the Center. I am indebted to Patricia Malone, the valiant collections manager at the Seamus Heaney Center, for providing access to the Heaney archive to listen to their collection of BBC Flying Fox radio interviews from the early 1970s onward. I am indebted to Christian DuPont, Burns Librarian at Boston College, and to James Murphy of Boston

College's Connolly House Center for Irish Programs, for a summer research residence in the Burns Scholar House. It was through the Boston College work that I was able to crystalize a period of desublimation in mid-century for the project. Moore Fellowships and the Moore Institute at the Hardiman Library at the National University of Ireland Galway, and particularly the support of Daniel Carey, were key for providing access to the Abbey Theater Digital Archive which allowed me to look through the notes and typescripts to conceptualize the Celtic Revival chapter. I also wish to thank Muireann O’Cinneide for her scholarly cheer during these fellowships. The NEH Summer Seminar on the Irish Sea Cultural Province at Queens University Belfast, the Manx Museum, and the University of Glasgow under the direction of Joseph Falaky Nagy and Charles MacQuarrie established an important footing that informed my understanding of Irish primitivism related to the medieval period. Kevin Dettmar's leadership of and lasting scholarly munificence after a NEH Summer Seminar at Trinity College Dublin on James Joyce's Ulysses remains a motivating and encouraging force. This seminar was critical for the creation of fundamental insights about Irish primitivism related to the Congo and Roger Casement that are present in the Joyce chapter of this book. I appreciate the access to the Wertheim Study at the New York Public Library, and especially librarian Mary Jones, of the General Research division. Justin Furlong, the Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts, James Harte, Special Collections, at the National Library of Ireland, were both remarkably generous during and after my research visits. I wish to thank Jane Maxwell, Manuscripts Curator at the Library, as well as the Board of Trinity College, the University of Dublin. I must acknowledge the British Library for the access to the Joyce letters in their holdings. For reading the drafts of this book in whole or in part along the way, I must thank Greg Erickson, Beth Gilmartin, Catie Piwinski, Greg Winston, and Joyce Zonana. I must acknowledge the late Claire A. Culleton as a model of scholarly munificence. I thank Palgrave Macmillan for allowing me to reprint aspects of my chapter from our co-edited book on primitivism in the Joyce chapter of this new one. I thank Margaret McPeake for her friendship and her enduring

scholarly insights into Irish Studies. And, finally, thanks to my husband, Larry, aka Lorenzo, who keeps me grounded, makes me laugh, and reminds me of what truly matters every day. With love always, Lorenzo.

1 Introduction Modern Ireland and the Primitive Sublime

DOI: 10.4324/9781003297390-1

In 1874, after scandal drove Sir William Wilde from the comforts of Dublin into a kind of internal exile in the west of Ireland, he published a series of articles on “The Early Races of Mankind in Ireland,” in which he insisted that the Irish “trace the footprints of [the] man we have…the vestiges of his language, and the physical and psychological characteristics still attaching to his modern representatives” (245). Wilde's forceful command presages the concern for and anxiety about the primitive that persists within modern Irish culture. From the latter half of the nineteenth and through the twentieth century, Irish writers highlighted a striking series of encounters with the most ancient elements of Irish culture, identified these elements as primitive manifestations of the indigenous peoples, and uncovered these primitive constructs as an exceptional means of experiencing the sublime. While critics have begun to assert the import and function of Ireland's modern primitives,1 no critic has yet examined the frisson of delight that such encounters engender within Irish modern culture as a whole. Ireland's primitive encounters provoke the sublime while relying on internal and troubling markers of cultural fear in order to create it.

The experience of the sublime is uniquely related to indigenous Irish primitivisms that twentieth-century writers have endeavored to retain as a marker of cultural distinction within the British Empire. It is the proximity to the primitive, which is itself a term that is highly contingent and always in flux, that seems to mark Irish writing, and thereby serves as a means to separate this indigenous eruption of the form from other twentieth-century configurations of primitive fixations. Unlike the English, for example, who move outside of the confines of their national borders to locate the primitive, the Irish most commonly recognize and encounter the primitive at home.2

Examples of primitivism abound in Irish art, which ranges from experiences of global migrants in Ireland to an Irish drive toward comparative indigeneity with such peoples. Works by Colum McCann, Brian Friel, and Jim Sheridan, to name a few, explore these connections and identify and articulate primitive alterities that reside within modern Irish culture. McCann's portrait of destruction in Let The Great WorldSpin, Sheridan's portrayal of an African Caribbean man in In America, and Friel's use of the figure of a returned Irish priest in Dancing atLughnasa manifest a seemingly relentless drive toward the primitive in Irish writing. The construct of primitivism functions variously as a fanciful imagined nostalgic past, as a peril of the alien and unfamiliar, or as a possible illustration of comparative distinction or relation. The notion of the “primitive” within Irish cultural discourse remains a mutable and conditional construct rather than one of consistency or unity (McGarrity and Culleton 1–2). Sinéad Garrigan Mattar explains simply, “Primitivism is the idealization of the primitive” (3). And, as David Brett finds, “Ireland has stood for the primitive” quite commonly in cultural discourse (30). Yet, within these straightforward assertions, there is a fundamental tension, such as when Garrigan Mattar conceptualizes Irish primitivism of the early twentieth century as a form of “proper darkness” (19). She finds that this “darkness… becomes tantalizingly paradoxical” and then asks “how can darkness be ‘proper,’ in the sense of the morally and socially correct, any more than it can be the ‘property’ of any one social grouping?” (19). She underlines a

nexus of possession, identity, and darkness to suggest the unsettled perspectives that create Irish primitivisms; the identification of “primitives,” then, becomes highly subjective and relative to cultural alignments and modes (McGarrity and Culleton 2–3). Garrigan Mattar distinguishes between romantic primitivism evident in wellworn tropes, including, most notoriously, the authentic and pure “Noble Savage” and the modernist primitivism evident in the shifting idealizations of the “brutal, sexual, and contrary” (4). The unique condition of Ireland's position as a British colony with the contingent independence that partition created refracts multiple visions of primitives within and beyond its borders, often as a peculiarly reflected portrait of Irish culture and art.3 A stunning inversion of the so-called “civilized” in Ireland becomes more acutely evident within twentieth-century artistic and literary experimentation. Widely evident during the modernist literary period's pyrotechnic aesthetic modes that shift, destroy, and illuminate boundaries and hierarchies within any conventional cultural formation, Irish writing beyond this period also becomes intensely focused on exploring the notions of self and other, of culture and belonging, at home and abroad. My publication with Claire A. Culleton of IrishModernismandtheGlobal Primitive was a key first step in this endeavor. Yet, the question of the enduring appeal of the primitive remains. What I suggest in Modern Irish Literature and the Primitive Sublime is that the primitive rhetorics within twentieth-century Ireland prevail because of their capacity, or their cogent force, to provoke the sublime. This movement is not merely a casual recognition of Ireland's primitive indigenous history, but a repeated rhetorical gesture that beckons the primitive sublime, a momentary and transcendent elation brought about by the recognition of the troubled, ritualistic, and sacrificial Irish past that consistently emerges in the long twentieth century.

This book will not attempt to impose a stable conception of Ireland's sublime, but rather it will examine its relentlessly unsettled formation(s) and dissipation(s) as they relate to the primitive during the twentieth century. Ireland's notion of the sublime as it becomes

transformed in Irish modernity is distinctively associated with the “dark, uncertain, and confused” elements that distinguish it from mere aesthetic magnificence. In fact, it is this very alienated state of bewilderment and horror in Irish cultural production that ultimately surrenders emotional pleasure in a repeated rhetorical movement that repels and seduces the Irish at once. Jerome Carroll notes that the sublime has “as many interpretations as it has appearances” (171). This notoriously elusive and mutable concept erupts, subsides, and then emerges again in twentieth-century Irish writing. These necessarily plural conceptions of the primitive sublime seem to follow the emerging nation state and its vexed cultural positioning as a former colony that achieves a kind of independence through partition, but remains situated in a challenging cultural nexus due to an enduring colonial legacy. According to Jean-François Lyotard, the sublime is “the only mode of artistic sensibility to characterize the modern” because it serves as an “expressive witness to the inexpressible…. pleasure and pain, joy and anxiety, exaltation and depression” (93). Although Lyotard asserts that this sublime facility emerged after World War II, the cultural turmoil surrounding an emerging Irish nation provoked a sense of sublime terror much earlier. Lyotard's arguments reside amid the network of theorists of the postmodern sublime which include Gilles Deleuze (“The Idea of Genesis in Kant's Aesthetics”), Julia Kristeva (Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection) and Fredric Jameson (Postmodernism, or the CulturalLogic of LateCapitalism). Yet, Lyotard's conceptions of the brutality of the interiority of the sublime are most prescient for this study of Ireland's modern primitive sublime. The notion of the sublime as evident in the primitive specifically in Ireland has been recently established by Luke Gibbons's Edmund Burke and Ireland, in which Gibbons chronicles his colonial sublime around the subaltern revolt against imperial authority. Gibbons reclaims Burke for Irish cultural discourse as an important if problematic figure given his writing against the French Revolution. Gibbons does not attempt a facile recuperation but rather engages with the nuanced complexity of Burke's aesthetic vision as it relates to Ireland's colonial position.

The long history of the sublime reaches back to Longinus and his treatise “An Essay on the Sublime,” written in the first century of the Christian era. The intellectual endurance of Longinus's conception of the sublime as a rhetorical notion reaches from the ancient world through the Renaissance and up until the advent of modernity. Unsurprisingly, the rhetoric of Longinus's sublime becomes key during the eighteenth century's exaltation of both highly stylized expression and reason. Alexander Pope mocks and reveres him at once, Longinus “Is himself that great Sublime he draws” (qtd. In Costelloe 6). The most famed philosophers of the sublime establish dichotomies between the sublime and the beautiful (Edmund Burke) and the inherent relation of the moral sublime (Immanuel Kant). In Irish writing, the conjoining of the primitive and sublime is consequential, even if it often relies on colonial ethnographic notions of culture and meaning. Matthew Rampley finds:

Although the sublime is a recurrent trope in accounts of the “primitive,” a crucial question concerns the limits of sublimity. It therefore becomes urgent to address not simply the obvious racist overtones of Kant, Hegel, and others—this is perhaps the more obvious point of critique—but also the limits of a theory formulated to account for the experiences of the Western subject.

(260)

What seems striking, then, for Irish writers is the degree to which they aestheticize the experience of the sublime through encounters with the primitive. They are both the agents as Western subjects and the objects of the primitive gaze as colonized subordinates in the British imperial endeavor.

The European Enlightenment philosophers were often captivated with consideration of the “others” in the emerging imperial systems at the same time as they endeavored to provide a rigorous intellectual framework for consideration of the human condition: social, material, cultural, and scientific. Edmund Burke is most recognized for his importance in the development of visual

aesthetics. As Sara Suleri notes, “when Burke invokes the sublimity… he seeks less to contain the irrational within a rational structure than to construct inventories of obscurity…. Such [an obscure] intimacy provokes the desire to itemize and to list all the properties of the desired [or sublime] object” (28). The sublime object therefore relates to both a sense of intimacy and obscurity—of the intensely close and the densely opaque. While the visual remains paramount for Burke's work, in a discussion of the “Celto-Kitsch,” one critic observes Burke's import to the development of art reaching into the twentieth century (though he does frame Burke traditionally within the visual approach of spectacle):

The Sublime… a condition of awe and it may be terror before the spectacle of Nature at Her grandest and least humanized, and before the spectacle of human lives attuned to such grandeur. The concept, as first defined by Burke in his Philosophical Inquiry should be regarded as Ireland's principle gift to the discourse of art and nature; as subsequently developed by Kant, it is the lynchpin of Romanticism and, some have argued, the founding moment of an important aspect of modernism.

(Brett 29)

What I suggest is that it is this founding moment of modernism, which as Brett argues was gestured toward by Burke centuries earlier, that becomes critical for Irish writing in the twentieth century in general and its delineations of the primitive sublime in particular. While the philosophers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries examine the nuances of the sublime and its workings in visual art, the phenomenon of the sublime in literary studies has received too little critical attention. The philosophical underpinnings of the sublime and its link with the primitive provide a nexus for further analyzing the literary engagements with the phenomenon. As one critic points out, there is an enduring tension in the primitive sublime: “For Kant the capacity for sublimating terror into an aesthetic experience is both natural and a consequence of

acculturation; the primitive both is and is not capable of experiencing the sublime” (Rampley 260). In Ireland, this fraught negotiation of the primitive as it becomes linked with the sublime suggests the degree to which its depictions navigate, reflect, and refract imperial authority and cultural positioning. Burke himself turns toward the poetic as a means of experiencing the sublime. While this may surprise contemporary readers today, given that Burke's theories are often associated exclusively with external markers, usually landscapes, Ellen Scheible acknowledges language as central to his theories. “In Burke,” she writes, “words occupy a separate space in our comprehension of the outside world, arguably one characterized by fiction and metaphor, yet they are still able to elicit the ‘ideas of beauty and of the sublime’ brought about by nature and art” (235). She explains further: “Because of the curious position of language in the excitation of emotion associated with the beautiful and the sublime, Burke isolates the effect of words on the senses, which eventually leads him to an analysis of poetry” (235). In the twentieth century, scholars and critics have reasserted the continued presence of the sublime and have expanded on Burke's poetic conceptions despite his aesthetics as being somewhat out of fashion as antiquated ideas. Yet, more recent thinkers have conceptualized the sublime not merely as an external encounter of the majestic and awe-inspiring that, in Burke's most well-known form, is also associated with terror; rather, they have expanded it from the conventional external stimulus into a psychological expression of modern interiority. For example, Scheible finds that for Burke the mind “feels,” rather than “thinks,” the sublime (228). Thus, the eighteenth-century “feeling” mind gives way in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries’ fractured interiority and consciousness. It is the sublime of psychological interiority to which twentiethcentury Irish writers seem particularly drawn. The experience of and psychological response to external geographies, however, do afford the catalyst for this movement within Modern Ireland toward the primitive sublime. According to Homi Bhabha, “being in the ‘beyond,’ then, is to inhabit an intervening space, as any dictionary will tell you. But to dwell ‘in the beyond’ is also… to be a part of revisionary

time, a return to the present to reinscribe our cultural contemporaneity; to reinscribe our human, historic commonality” (7). A sense of temporal and geographic duality emerges within the primitive sublime. A particularly critical formation for Irish cultural discourse linking the primitive with the sublime can be traced to the Aran Islands, which is a location that is central for the Revivalists. Heather Clark explains the 1896 journey undertaken by Arthur Symons and W.B. Yeats to Inishmore, the largest geographically of the Aran Islands:

The two spent three days wandering among the cliffs and villages, taking stock of both archaeological ruins and island folk alike in their search for the last vestiges of Irish Ireland. Symons published his observations four months later in an article entitled “The Isles of Aran,” in which he described the islands as primeval, primitive and sublime. …He grasped that the island's allure would always be shadowed by a sense of alienation, “we seemed also to be venturing among an unknown people, who, even if they spoke our own language, were further away from us, or foreign than people who spoke an unknown language and lived beyond other seas” (306).

(30, emphasis added)

The primitive sublime that Symons describes in his essay has enduring consequences for Irish writing through the twentieth century. This notion of belonging amid alienation, of extremes within contained spaces, reverberates from the shores of the Aran Islands and Galway Bay throughout Ireland and even, ultimately as we will see, onto New York harbor. Much like primitivism writ large, the primitive sublime is not a singular, but a plural manifestation. It is not easily reducible to a single framework, but rather transforms within the development of temporal, geographic, political, and psychological networks and perspectives.

The sublime in Irish writing rests upon historical intersections of colonial encounters. This manifestation of the sublime often rests

upon language and rhetorics of politics rather than exclusively space or location. In his work “The Irish Sublime,” Terry Eagleton finds:

If the Irish are the greatest talkers since the Greeks, as Oscar Wilde once remarked with himself well in mind, it is partly because language in a society where print arrived fairly late remains cast in an oral, oratorical mold, partly because discourse is a form of displacement from a harsh social reality, and partly because language in colonial conditions becomes a terrain of political conflict.

(28)4

The centrality of language, as Eagleton describes it, for the Irish sublime is profoundly linked with Ireland's colonial condition. Elsewhere, Eagleton asserts that the Irish Famine was “in Burkean parlance, a sublime event, for the mind-buckling power of the sublime is by no means simply pleasant rhetoric, and if it stirred some to rancorous rhetoric, it stunned others into an appalled muteness” (31).5 While the Famine as a sublime event in Irish cultural history and its enduring memory seems a shocking suggestion even today, Eagleton's assertion of nationally traumatic events in the nineteenth century as sublime prefigures Ireland's twentieth- and twenty-first-century cultural horrors that provoke the primitive sublime.

There are two dominant and related courses that characterize the primitive sublime and that manifest, subside, and then remerge throughout the twentieth century. In the following chapters, these progressions initially emphasize a sense of Irish indigeneity and the desire for connection amid the colonial world as it becomes increasingly fractured, after the Second World War, into postcolonial and neocolonial frameworks. The turn of the twentieth century saw a profoundly influential movement toward native Irish folklore, literary arts, and cultural performance. While the Rising of 1916 becomes immortalized in Yeats's encapsulation of the primitive sublime with his refrain of “terrible beauty,” Irish writers begin to question the immortalization and nostalgia so present in the Revival

fairly quickly thereafter, especially evident in the Revivalist mockeries of James Joyce in his Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939). During the mid-century period after the establishment of the Free State and the Second World War, Irish writing evidences a pronounced desublimation away from primitive alterities and toward the quotidian difficulties of economic conditions and social repression. With the advent of “the Troubles” in the late 1960s, the primitive sublime reemerges with a powerful surge through the fraught cultural dynamics of the period that ended with the hope of the imperfect, yet enduring Good Friday/Belfast Agreement, which established a difficult peace in the North.6 Finally, what I assert stands as the end of the primitive sublime manifests in three post9/11 novels. From then on, the desire for a return to a lost past and the transcendent elation it potentially holds is revealed to be illusory. The opening chapter of this book, “Performing the Primitive Sublime: the Celtic Revival and Irish Indigeneity,” examines the primitive sublime as it emerges during the literary enactment(s) of Irish indigeneity during the period of the Celtic Revival. Due to the dominance of the stage in the creation of a national identity for the Irish, the essential markers of this predominantly dramatic movement become foregrounded in the analysis. W.B. Yeats, Augusta Lady Gregory, and John Millington Synge are the central and most famed practitioners during this period who set their works either within or as refractions of Irish indigeneity that served as a catalyst for the primitive sublime. These writers foreground the avian in their movements toward transcendence that reflect the unique aspects of their engagement with the markers of the primitive sublime. Surprisingly, these writers gesture toward the work of George Bernard Shaw and his commentary on animal vivisection in his stage play, The Doctor's Dilemma. Yeats, Gregory, and Synge seek out ways to negotiate between the modern and the primitive as they collapse the boundaries between the two realms. This reliable penetrability seeks to underscore the ways in which these writers make the contemporary and the historical intersect habitually. They venerate the peasantry in their symbolic recuperation of the

primitive as they suggest that these figures offer a unique capacity to provoke and reflect upon the experience of sublime rapture. The horror at the root of so many of the dramatic works during this time suggests the appeal of sacrifice and violence that seem to repeatedly emerge. This violence and even terror become a seductive mode of cultural engagement that continually attracts the writerly and the public imagination(s).

The following chapter, titled “James Joyce and the Primitive Sublime: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses and Finnegans Wake,” charts the development of Joyce's primitive sublime using the intersecting tropes of the desire for/of the feminine and the African other. Joyce's depiction of his primitive sublime emerges clearly with the transcendence of the final scene of Portrait when Stephen escapes his labyrinth and grows to incorporate Joyce's increasingly sophisticated and nuanced depictions of both the Irish and African figures in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. For Joyce, the primitive sublime is a reflection of the troubling desire for distinction between and fear of communion with other globalized colonial figures and societies. Joyce is aware of the primitive movement within European literature and cultures from the time of his undergraduate days at University College Dublin. He stakes out bold movements against cultural censorship and finds that confrontations with the primitive at home and abroad help to create a sublime vision of Irish identity. Joyce uses the Irish in Africa and especially the work of Roger Casement in both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake to suggest both the Irish identification with and desire for distinction from fellow colonized peoples. The depiction of the Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931 in Finnegans Wake provides a lens into the commonality with and desire for African figures that capture a desecration of and longing for them at once. This tension between the two conflicting sentiments creates Joyce's primitive sublime.

This book's next chapter, “Mid-century Malaise and Desublimation in Samuel Beckett, Flann O’Brien, Kate O’Brien, and Edna O’Brien,” identifies and analyzes the representations of desublimation in Irish writing of the period. These disappointments are related to the

realities of independence and its associated conservative political movements that insisted on placing Irish women in the domestic sphere and squashing progressive social ideas. The reaction to independence within becomes complicated due to the peculiar position of the Republic as officially neutral and the North/Northern Ireland being subject to repeated German bombing campaigns due to its position as a part of the United Kingdom. The period after the Second World War was one of large scale decolonizing movements across the globe. In Irish writing the newly bipolar world amid the collapse of European empires is reflected in an increasing outward migration, often to London, a sense of entrapment at home especially acute for women and artists, and the emergence of an anxiety related to the intersection of globalized “others” and the Irish “self.” Ireland's tenuous cultural position of a newly independent nation that is also a former colony, a part of which remains part of the United Kingdom, creates a sense of profound malaise and disappointment. What seems most salient, however, within this dynamic bricolage of global change and increasing intersection is the virtually complete disappearance of the primitive sublime in Irish writing. The Celtic Revival's privileging of indigenous Irish expressions of primitivism and its capacity, indeed relentless drive, to provoke the sublime, all but evaporates. The Revival became a subject of ridicule in the midcentury. The concerns that manifest in Irish writing from the late 1930s to the early 1960s relate to social suppression and the troubling immanence of cultural provincialism. In Samuel Beckett's Murphy, the hero is caught in an urban labyrinth and wishes after his death to have his ashes flushed down the toilet of Dublin's Abbey Theater during a performance. In Flann O’Brien's often overlooked drama, Faustus Kelley, the hero sells his soul not for starving peasants as in Yeats's Countess Cathleen but rather for his own political advancement and seat in the Dáil, the Irish Parliament. In O’Brien's novel, AtSwim-Two-Birds, the hero seems caught in webs of narrative circuitousness and selfregard that mock the Celtic Revival and Irish history. In Pray for the Wanderer, Kate O’Brien's novel of suppression and censorship, she shows the dangers for an artist in attempting to live freely while in

Ireland. While Kate O’Brien makes her protagonist figure male, Edna O’Brien's CountryGirlsTrilogy, foregrounds the feminine perspective overtly and shows the dangers inherent in Ireland for women as subjects of an oppressive state. In the final novel of O’Brien's trilogy, the enduring anxiety of others reemerges profoundly as a threat to cultural exclusivity and an opportunity for cultural exchange. The peculiar form of Irish independence creates a state reliant on censorship and suppression that is unable to stop cultural exchange and increasing intersection.

“The Living Dead: the Resurgence of the Primitive Sublime in the late Twentieth Century,” the penultimate chapter, analyzes the reemergence of the primitive sublime from the late 1960s through the late 1990s. This chapter examines the rapture of Ireland's primitive sublime related to the reanimation of the Irish corpus from bog and isle to negotiate the specter of political and familial violence within the primitive affiliations manifest in Ireland's broad Viking and Atlantic world histories. Three writers, Seamus Heaney, Eavan Boland, and Brian Friel foreground the troubling connections that rely on primitive alterities drawn from within but profoundly engaging others abroad as they manifest in Irish culture. Heaney's bog poems offer up victims of Iron Age human sacrifice to comment upon his contemporary victims as reanimations of the Troubles in The North/Northern Ireland. Eavan Boland uses frameworks from across the Atlantic world to foreground the very notion of a colony and to examine how the dead necessarily rise again in a postcolonial nexus of cultural interchange. Brian Friel's Dancing at Lughnasa suggests the complexity of the Irish position with his characterization of a priest, “gone native,” who returns to the rural Donegal of 1936 to suggest a moving affinity with colonized peoples and their practice of sacrifice and possession. These writers use the trope of the undead and the practice of reanimation amid the postcolonial world to provide a scathing critique of the enduring costs of colonial violence and to revel in the productive cultural intersections of the globalized world. The avatars of the undead serve as manifestations of the primitive sublime as the resurgence becomes linked with the

Irish self even as it confronts unremitting violence and recognizes another period of lamentable and uncomfortably familiar sacrifice.

The final chapter, titled “Primitive Sublime Terror: Writing New York after 9/11 in O’Neill, McCann, and Tóibín,” examines Irish artistic production set in New York City and published in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. These works reflect on the Irish position in New York City during the period both before and after the events of 9/11. Jim Sheridan's 2002 film, In America, serves as a starting point to suggest how the Irish in New York rely upon depictions of the other to reflect the Irish self in the wounded cityscape. The novels, Colm Tóibín's Brooklyn, Colum McCann's Let the Great WorldSpin, and Joseph O’Neill's Netherland, express the horrors of the twenty-first century through the examination of the Irish in New York beginning in the mid-twentieth century. Brooklyn uses the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust to comment upon the intersection of the Irish in New York in a subtle movement of cultural occlusion and unknowing. McCann's novel, Let the Great World Spin, goes back and forth between the early 1970s, the American experience in Vietnam and the aftermath of the Towers’ collapse, and even to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, to suggest the ways in which the primitive sublime erupts during a tense moment of cultural change. Netherland, Joseph O’Neill's novel, diagrams New York after 9/11 using both a Dutch banker and a Trinidadian entrepreneur as exemplars of cultural intersection that reveal the tense awe of the primitive sublime encountered through another but reflective of the self in the early twenty-first century. Finally, A Ghost in the Throat, Doireann Ni Ghriofa's translation of and reimaged response to the eighteenth-century Irish language poet Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill's“Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire” or “Lament for Art O’Leary” suggests a pivot away from the primitive sublime in a moving examination of personal and cultural loss.

Notes

1. See both Marianna Torgovnick's Gone Primitive and Sinéad Garrigan Mattar's Primitivism, Science and the Irish Revival for further reading.

2. For further reading, see Maria McGarrity and Claire A. Culleton's introduction to IrishModernismandtheGlobalPrimitive.

3. For a discussion of primitivism as an “inversion of the self,” see Michael Bell's Primitivism(80).

4. Eagleton continues, “The term “blarney” is a political one: it derives from the sixteenth-century Earl of Blarney who when called upon to make his submission to Elizabeth I is said to have responded with such a torrent of rococo rhetoric that nobody could work out whether he was submitting or not. If language is important in the colonies, it is among other things a remarkably convenient way of hiding one's thoughts from one's masters” (28).

5. Eagleton further explains, “Christopher Morash has suggested that the great silence which followed in the wake of the Famine has been somewhat overplayed; but the historian Brendan Bradshaw maintains that only one academic study of the event occurred in Ireland between the 1930s and 1980s” (31).

6. This Agreement is known both as the Good Friday Agreement and the Belfast Agreement in the North/Northern Ireland. I am choosing to note both terms to acknowledge and include the perspectives of all communities in Belfast.

References

Bell, Michael. Primitivism. Methuen, 1972.

Bhabha, Homi K. TheLocationofCulture. Routledge, 1994. Brett, David. “Heritage: Celto-Kitsch & the Sublime.” Circa, no. 70, 1994, pp. 26–31, https://doi.org/10.2307/25562734

Carroll, Jerome. “The Limits of the Sublime, the Sublime of Limits: Hermeneutics as a Critique of the Postmodern Sublime.” The JournalofAestheticsandArtCriticism, vol. 66, no. 2, 2008, pp. 171–81, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6245.2008.00297.x

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

He went on to tell me about a question of property concerning two golden heads. There is a mountain called Popa (5000 feet high) standing right in the middle of the plain. We could see it from the back of the house. It is an extinct volcano and is the home of two of the most important Nats in all Burmah. They have lived on Popa ever since about 380 A.D. They were brother and sister, and used to have a festival held on this mountain every year in their honour.

About the middle of the eighteenth century one of the kings of Ava— Bodawpaya—presented to the Popa villagers two golden heads, intended to represent these Nats. At that time Popa village, for some reason, was a separate jurisdiction outside the jurisdiction of the Pagan governor. What happened was that these heads were kept in the Royal Treasury at Pagan for safety, and taken up to Popa every year for the festival and brought back again. Subsequently, Popa came under the jurisdiction of the Pagan governor. Then apparently the Pagan people began to think that these heads really belonged to them, and they were kept in Pagan until the annexation in 1886. After this, our Government, thinking they were very valuable relics which ought to be preserved, sent them down to the Bernard Free Library in Rangoon, where they have been lodged ever since.

Some time ago the Popa villagers sent in a petition that they might be allowed to have their heads back, as they wanted them for the festival. Investigations were started and about a month before my visit Mr Cooper had been up to Popa and there dictated a written guarantee, signed by the principal men of the village (the Lugyis, as they are called), that they would undertake the responsibility of looking after these heads if they were given back to them. Then Mr Cooper came to Pagan and had a meeting of the Pagan Lugyis, asking them to sign a written repudiation of claim, and that's where the matter rested.

I asked Mr Cooper to tell me the story of these famous Nats, in whose honour a coconut is hung up in houses in this part of Burmah just as regularly as we do for the tomtits at home, so that they can eat when they like, and here is the story in his own words as he told it to me at Pagan.

These Nats have a good many names, but their proper names are Natindaw and Shwemetyna, and they used to live in a place up the river

called Tagaung, a thousand years ago. Natindaw, the man, was a blacksmith. He was very strong indeed—so strong that the King of Tagaung was afraid of him and gave orders that he should be arrested. The man (he had not become a Nat then) was afraid and ran away, but his sister remained and the king married her. After some time the king thought of Natindaw again and believed that although in exile he might be doing something to stir up rebellion. So the king offered Natindaw an appointment at the Court, and when Natindaw came he had him seized by guards and bound to a champak tree near the palace. Then the King had the tree set on fire, and Natindaw proceeded to burn up. Just at that moment the queen (Natindaw's sister) came out of the palace and saw her brother being burnt. She rushed into the fire and tried to save him, and failing, decided to share his fate.

The king then tried to pull her out by her back hair but was too late, and both the brother and sister were utterly consumed except their heads. That finished them as human beings, but they became Nats and lived up another champak tree at Tagaung, and there, because they had been so shockingly treated, they made up for it after death. They used to pounce on everyone who passed underneath—cattle and people. At last the king had the tree with the brother and sister on it cut down, and it floated down the river and eventually stranded at Pagan. Well, the King of Pagan, who was at that time Thurligyaung, had a dream the night before that something very wonderful would come to Pagan the next day by river. In the morning he went down to the bank and there he found the tree with the human heads of Natindaw and Shwemetyna sitting on it, and they told him who they were and how badly they had been treated. The king became very frightened and said he would build them a place to live in on Popa. So they thanked him and he built them Natsin, a little sort of hut on Popa, and there they have lived ever since.

Every year the kings of Pagan used to go in state and offer sacrifice to Natindaw and Shwemetyna of the flesh of white bullocks and white goats, and the Popa Nat story is still going on because of the latest development about the golden heads.

It is a Burmese saying that no one can point in any direction at Pagan in which there is not a pagoda, and on many of them in the mornings I saw vultures—great bare-necked creatures—thriving apparently on barrenness.

Lack of water is the great trouble to the villages. The average rainfall in this dry zone (which extends roughly from south of the Magwe district to north of Mandalay) is fifteen to twenty inches.

Tenacious of life, these Thaton villagers of Pagan and Nyaungoo, led into captivity by King Naurata, whose zeal as a religious reformer had been fired by one of their own priests, survived their conquerors. They became, nine hundred years ago, slaves attached to the pagodas, and under a ban of separation, if not of dishonour, they have kept unmixed the blood of their ancestors, are the only Burmese forming anything like a caste, and still include some direct descendants of their famous king.

In the villages there is some weaving and dyeing of cloth, and quite a large industry in the making of lacquer bowls and boxes.

It was not far to walk from the Circuit House to one of the villages,— across the dry baked, brick-strewn earth, past great groves of cactus and through the tall bamboo fence that surrounds the village itself. I passed a couple of carts with primitive solid wheels, and under some trees in the middle of the collection of thatched huts with their floors raised some feet above the ground, a huge cauldron was sending up clouds of steam. Some women were boiling dye for colouring cloth. This was Mukolo village. I called at the house of U Tha Shein, one of the chief lacquer makers, and he took me about to different huts to see the various stages of the work.

First, a "shell" is made of finely-plaited bamboo; this is covered with a black pigment and "softened" when dry by turning it on a primitive lathe and rubbing it with a piece of sand-stone. Then the red lacquer is put upon the black box with the fingers, which stroke and smear it round very carefully. In Burmese the red colour is called Hinthabada, from a stone I was told they buy in Mandalay. The bowls now red are set to dry in the sun, and next are placed in a hole in the ground for five days,—all as careful a process as that of making the wine of Cos described in Sturge Moore's Vinedresser.

When they are exhumed after hardening, a pattern is finally engraved or scratched on the lacquer with a steel point and a little gold inlaid on the more expensive bowls.

I was going from house to house to see the different stages of the work, when I heard a pitiful wailing and came upon the saddest sight I had yet seen on my journey. The front of a thatched hut was quite open. A mangy yellow pariah dog was skulking underneath, and some children were huddled silent upon the steps leading up to the platform floor. There lay a little boy dead, and his mother and grandmother were sorrowing for him. The grandmother seemed to be wrinkled all over. Her back was like a withered apple. She moaned and wailed, and tears poured from her eyes. "Oh! my grandson," she cried—"where shall I go and search for you again?"

She was squatting beside the little corpse and pinching its cheeks and moving its jaws up and down. "You have gone away to any place you like— you have left me alone without thinking of me—I cannot feel tired of crying for you."

And a Burman told me that the child had died of fever, and that the father had gone to buy something for the funeral. He added, "The young woman will never say anything—she will only weep for the children. It is the old woman only that will say something."

CHAPTER V

MANDALAY

Christmas morning at Mandalay was bright, crisp and cold, with just that bracing "snap" in the air that makes everyone feel glad to be in warm clothes. On such a day the traveller feels a sense of security about the people at home—they must be comfortable in London when it is so jolly at Mandalay!

I was drawn by some Chinese characters over a small archway in Merchant Street to turn up a narrow passage between high walls, which led me to a modern square brick joss-house. There were several Chinese about

and I got to understand that the temple was especially for all people who were sick or ill, and I went through the very ancient method of obtaining diagnosis and prescription.

BURMESE

PRIEST AND HIS BETEL BOX.

An English-speaking Chinaman told me that this temple was "the church of Doctor Wah Ho Sen Too," who lived, he added, more than a thousand years ago, and had apparently anticipated the advantages of Rontgen rays.

The American who is watching in Ceylon the formation of pearls without opening of oysters, is yet far behind Doctor Wah Ho Sen Too, to whom all bodies are as glass. The stout Chinaman grew quite eloquent in praise of this great physician, explaining with graphic gestures how he had been able to see through every part of all of us, and follow the career of whatever entered our mouths.

In front of the round incense-bowl upon an altar, before large benevolent-looking figures, was a cylindrical box containing one hundred slips of bamboo of equal length (if any reader offers to show me all this at Rotherhithe or Wapping, I shall not dispute with him but gladly avail myself of his kindness). I was directed to shake the box and draw out at random one of the bamboo slips. This had upon it, in Chinese characters, a number and some words, and I was told that my number was fourteen. Upon the lefthand wall of the temple were serried rows of one hundred sets of small printed reddish-yellow papers. I was taken to number fourteen set and bidden to tear off the top one, and this was Doctor Wah Ho Sen Too's prescription.

I have not yet had that prescription made up; to the present day I prefer the ailment, but I asked the English-speaking Chinaman what the medicine was like, and he told me that it was white and that I could get it at Mandalay. When he was in South America Waterton slept with one foot out of his hammock to see what it was like to be sucked by a vampire, but I am of opinion there are some things in life we may safely reject on trust, declining taste of sample.

I went from the joss-house of Merchant Street to the Aindaw Pagoda, about the middle of the western edge of the city, a handsome mass, blazing with the brightness of recent gilding. From "hti" to base it was entirely gilt, except for the circle of coloured glass balls which sparkled like a carcanet of jewels near the summit. Outside the gate of the Aindaw Pagoda, where some Burmans were playing a gambling game, a notice in five languages— English, Burmese, Hindostani, Hindi and Chinese, announced, "Riding, shoe and umbrella-wearing disallowed."

The Queen's Golden Monastery at the south-west corner of the town is a finer specimen of gilded work, built in elaborately-carved teak, with a great

number of small square panels about it of figure subjects as well as decorative shapes and patterns. Glass also has been largely introduced in elaborate surface decoration at the Golden Monastery, not in the tiny tessarae of Western mosaic but in larger facets, giving from the slight differences of angle in the setting, bright broken lights almost barbaric in their richness. No one seems to know where all the coloured and stained glass that is so skilfully used in Burmese temples came from—whether it was imported or made in the country.

The priests were returning to the monastery with bowls full of food from their daily morning rounds, but there were very few people about at all, and the place was almost given up that day to a batch of merry children, who came gambolling round me, some of them pretending to be paralysed beggars with quaking limbs.

It was very different at the Maha Myat Muni, the Arrakan Pagoda, which was thronged with people like a hive of bees. This pagoda includes a vast pile of buildings and enshrines one of the most revered images of Buddha, a colossal brass figure seated in a shrine both gorgeous and elaborate, with seven roofs overhead. Of shrines honoured to-day in Burmah the Arrakan Pagoda is more frequented than any except the Shwe Dagon at Rangoon, and is approached through a long series of colonnades gilded, frescoed, and decorated with rich carving and mosaic work. They are lined with stalls of metal-workers, sellers of incense, candles, violet lotus flowers, jewels, sandalwood mementoes, and souvenirs innumerable, among which the most fascinating to the stranger are grotesque toy figures, with fantastic movable limbs, which would make an easy fortune at a London toy-shop, and before long will doubtless be exported and gradually lose their exotic charm.

Passing through this Vanity Fair I at last reached the shrine, and in the dim interior light I climbed up behind the great figure and followed the custom of native pilgrims in seeking to "gain merit" by placing a gold-leaf upon it with my own fingers. At all hours of every day human thumbs and fingers are pressing gold-leaf upon that figure of Gautama. Outside in the sunlight white egrets strutted about the grounds, and close by was a tank where sacred turtles wallowed under a thick green scum. A swarm of ricesellers besought me to buy food for the turtles, and their uncomfortable persistence was, of course, not lessened by patronage. The overfed animals

declined to show their heads, leaving the kites and crows to batten on the tiny balls of cooked rice.

Now close to this turtle-tank and still within the precincts of the temple was a large structure, evidently very much older than the rest of the buildings—a vast cubical mass of red brick with an inner passage, square in plan, round a central core of apparently solid masonry. Against one side of this inner mountain of brick-work was the lower half of a colossal figure, also in red brick, and cut off at the same level as the general mass of the building. Whether the whole had ever been completed or whether at some time the upper half had been removed, I could not tell. It was as if the absence of head and shoulders cast a spell of death, which surrounded it with a silence no voice ventured to dissipate, and with the noise and hubbub outside nothing could have more strikingly contrasted than the impressive quiet of this deserted sanctuary.

That Christmas afternoon, as already told, I left Mandalay on my way to Bhamo, returning afterwards for a longer stay.

Far away, beyond Fort Dufferin on the other side of the city, rises Mandalay Hill which I climbed several times for the sake of the wonderful view. In the bright dazzle of a sunlight that made all things pale and fairylike, I passed along wide roads ending in tender peeps of pale amethyst mountains. I crossed the wide moat of Fort Dufferin, with its double border of lotus, by one of the five wooden bridges and, traversing the enclosure, came out again through the red-brick crenelated walls by a wide gateway, and re-crossed the moat to climb the steep path by huge smooth boulders in the afternoon heat. It was as if they had saved up all the warmth of noon to give it out again with radiating force. At first the way lies between low rough walls, on which at short intervals charred and blackened posts stand whispering, "We know what it is to be burned"—"We know what it is to be burned." They were fired at the same time as the temple at the top of the hill over twenty years ago; but the great standing wooden figure of Buddha, then knocked down, has been set up again, though still mutilated, for the huge hand that formerly pointed down to the city lies among bricks and rubble.

The Queen's Golden Monastery and the Arrakan Pagoda were hidden somewhere far away among the trees to the south of the city. Below, I could

see the square enclosure of Fort Dufferin, with its mile-long sides, in which stands King Thebaw's palace and gardens, temples and pavilions, and I could see the parallel lines of the city roadways. Mandalay is laid out on the American plan, with wide, tree-shaded roads at right angles to each other. Nearer to the hill and somewhat to the left lay the celebrated Kuthodaw or four hundred and fifty pagodas, whereunder are housed Buddhist scriptures engraved upon four hundred slabs of stone. The white plaster takes at sunset a rosy hue, and in the distance the little plot resembles some trim flower-bed where the blossoms have gone to sleep.

BURMESE MOTHER AND CHILD.

One of the loveliest things about Mandalay is the moat of Fort Dufferin. In the evening afterglow I stopped at the south-west corner, where a boy was throwing stones at a grey snake, and watched the silhouette of walls and watch-towers against a vivid sky of red and amber and the reflections in the water among the lotus leaves. Each side of the Fort is a straight mile long, and the moat, which is a hundred yards across, has a wide space all along the

middle of the waterway quite clear of lotus. But moat and walls are both most beautiful of all at sunrise. The red bricks then glow softly with warm colour, and against their reflection the flat lotus leaves appear as pale hyaline dashes.

Within, upon the level greensward, you may find to-day a wooden horse —not such a large one as Minerva helped the Greeks to build before the walls of Troy, nor yet that more realistic modern one I have seen in the great hall, the old "Salone" of Verona—but a horse for gymnastic exercises of Indian native regiments of Sikhs and Punjabis. Strange barracks those soldiers have, for they sleep in what were formerly monasteries with halls of carved and painted pillars.

I was asking the whereabouts of the only Burmese native regiment and found it just outside Fort Dufferin, in "lines" specially built. It is a regiment of sappers and miners. On New Year's Day Captain Forster, their commanding officer, put a company of these Burmans through their paces for me. In appearance they are not unlike Gourkhas, sturdy and about the same height, and like the Gourkha they carry a knife of special shape, a square-ended weapon good for jungle work.

King Thebaw's palace stands, of course, within the "Fort," which was built to protect it. It is neither very old nor very interesting, and the most impressive part is the large audience hall. The columns towards the entrance are gilded, but on each side the two nearest the throne are, like the walls, blood-red in colour, and the daylight filtering through casts blue gleams upon them. It was not here, however, that the king was taken prisoner, but in a garden pavilion a little distance from it with a veranda, and according to a brass plate let into the wall below:—

"King Thebaw sat at this opening with his two queens and the queen mother when he gave himself up to General Prendergast on the 30th November, 1885."

I was talking one day with an army officer in a Calcutta hotel about Burmah, and he told me how he himself had carried the British flag into Mandalay with General Prendergast, and that it had been his lot to conduct the Queen Sepaya (whom he declared does not deserve all that has been said against her) to Rangoon, and he gave her the last present she received in Burmah. She was smoking one of the giant cheroots of the country and he gave her a box of matches.

I had never quite understood the annexation and that officer explained it as follows:—"We knew the French were intriguing—that Monsieur Hass, the French Ambassador at Rangoon, was working at the Court—and we got at his papers and found he was just about to conclude a treaty with Thebaw. The chance we seized was this—a difference between Thebaw and the Bombay Burmah Trading Company. For their rights in forest-land in Upper Burmah they paid a royalty on every log floated down. Now other people were also floating logs down, and Thebaw claimed several lakhs of rupees from the Bombay Burmah Company for royalties not paid. The Company contended they had paid all royalties on their own logs, and that the unpaid monies were due on other people's timber, and we seized the excuse and took Mandalay in the nick of time, defeating the French plans."

The most noticeable feature of the Mandalay Bazaar is the supremacy of the Burmese woman as shopkeeper. The vast block of the markets is newly built and looks fresh and spick and span, though without anything about its structure either beautiful or picturesque. It is like Smithfield and Covent Garden rolled into one, and given over entirely to petticoat government. I am told there are close upon 200,000 people in Mandalay, and those long avenues of the great bazaar looked fully able to cope with their demands. There is the meat-market, with smiling ladies cutting up masses of flesh; the vegetable-market, with eager ladies weighing out beans and tamarinds; the flour and seed-market, with loquacious ladies measuring out dal and riceflour and red chili and saffron powder; the plantain-market, with laughing ladies like animated flowers decorating a whole street of bananas; the silkmarket, with dainty ladies with powdered faces enticing custom with deft and abundant display of tissues and mercery,—and yet this does not tell one half of the Mandalay Bazaar. I have not even mentioned the flower-market, with piquant ladies—fully alive to the challenging beauty of their goods—

selling roses or lotus, with faces that express confident assurance of their own superior charms.

Perhaps it is not hardness—perhaps it is merely some lack of appreciation in me—but in spite of all that has been said or written in their praise, I could not find those Burmese women as charming as the shop-girls of London. I admit that they have a very smart way of twisting a little pink flower into the right side of their hair, and although I have seen a great many sleeping upon the decks of river steamers, I never heard one snore. Many men find wives, I was told, in the Mandalay Bazaar, and they are said to make excellent housekeepers. One perfectly charming little woman I did see, the wife of an Eurasian engineer (or is not "Anglo-Indian" now the prescribed word?), but she looked too much like a doll; and while a real doll who was a bad housekeeper would be unsatisfactory enough, a good housekeeper who looked like a doll would surely be intolerable.

Thinking of dolls brings me to the marionettes which still delight the Burmese people. They have long since gone out of fashion in England, "Punch and Judy" shows fighting hard to keep up old tradition; in Paris, the "Guignol" of the side alleys of the Champs Elysees are nowadays chiefly patronized by children, and you must go further East to find an adult audience enjoying the antics of dolls. Marionettes had a vogue in ancient Greece, and in Italy survived the fall of Rome. Even in Venice the last time I went to the dolls' theatre I found the doors closed, but in Naples they flourish still, and at the Teatro Petrilla in the sailors' quarter I have seen Rinaldo and Orlando and all the swash-buckling courage of mediæval chivalry in animated wood.

At Mandalay there is the same popular delight in doll drama, and one evening I watched a mimic "pwe" for an hour. The story was another version of that which I had already seen acted by living people. The showman had set up his staging in a suitable position, with a wide and sloping open space before it, and there was the same great gathering of young and old in the open air, lying on low four-post bedsteads or squatting on mats, while outside the limits of the audience stalls drove a thriving trade in cheroots and edible dainties. How the people laughed and cackled with delight at the antics of the dolls! These were manipulated with a marvellous dexterity, and seemed none the less real because the showman's hands were often visible as

he jerked the strings. I walked up to the stage and stood at one end of it to get the most grotesque view of the scene. A long, low partition screen ran along the middle of the platform. Behind this, limp figures were hanging ready for the "cues," and the big fat Burmese showman walked sideways up and down, leaning over as he worked the dancing figures upon the stage. The movements were a comic exaggeration of the formal and jerky actions of the dance, but the clever manipulation of a prancing steed, a horse of mettle with four most practical flamboyant legs, was even more amusing.

The parts of the dramatis personæ were spoken by several different voices, and the absence of any attempt to hide the arms and hands of the showman did not diminish the illusion, while it increased the general bizarre character of the scene rather than otherwise, and was an excellent instance of the fallacy of the saying—Summa ars est celare artem.

Blessed be the convention of strings! The success of a marionette show, as of a government, is no more attained by a denial of the wire-puller's existence than the beauty of a marble statue is enhanced by realistic colouring.

CHAPTER VI

SOUTHERN INDIA, THE LAND OF HINDOO TEMPLES

A long line of rocks and a white lighthouse in the midst of them—this is the first sight of India as the traveller approaches Tuticorin, after the sea journey from Colombo. He sees the sun glinting from windows of modern buildings, the tall chimney of a factory and trailing pennons of "industrial" smoke. Far to the left, hills faintly visible beyond the shore appear a little darker than the long, low cloud above them. Then what had seemed to be dark rocks become irregular masses of green trees. Colour follows form—

the buildings grow red and pink and white, and the pale shore-line a thread of greenish-yellow. The sea near Tuticorin is very shallow, and the steamer anchors at least four miles out, a launch crossing the thick yellow turbid water to take passengers ashore. On nearer view the lighthouse proves to be on a tree-clad spit or island, and to the left instead of the right of the harbour. Near the jetty I saw large cotton-mills, and passed great crowds of ducks (waiting to be shipped to Ceylon), which dappled the roadside as I made my way to the terminus of the South Indian Railway. At first the train passes through a flat sandy country with little grass, but covered with yellow flowering cactus, low prickly shrubs and tall palmyra palms. The shiny cactus and sharp-pointed aloe leaves seemed to reflect the bright blue of the sky, and by contrast a long procession of small yellow-brown sheep looked very dark.

Presently the ground changed to red earth and tillage. Then we passed more aloes and bare sand and a few cotton-fields. A thin stream meandered along the middle of a wide sandy bed, and a line of distant mountains, seen faintly through the shimmery haze of heat, seemed all the while to grow more lovely. Taking more colour as the day advanced they stretched along the horizon like the flat drop-scene of a theatre, abruptly separate from the plain. After passing several lakes like blue eyes in the desert some red sloping hills appeared to make a link in the perspective, and I reached my first stopping-place, the famous Madura.

First I drove to that part of the great temple dedicated to Minachi, Siva's wife, and then to the Sundareswara Temple dedicated to Siva himself under that name.

The typical Dravidian temple, the Southern form of the Hindoo style of architecture, consists of a pyramidal building on a square base divided externally into stories, and containing image, relic or emblem in a central shrine. This Vimana is surrounded at some distance by a wall with great entrance gateways or Gopuras, similar in general design to the central building but rectangular instead of square in plan, and often larger and more richly decorated outside than the Vimana itself. Then there is also the porch of the temple or Mantapam, the tank or Tappakulam, the Choultry or hall of pillars and independent columns or Stambhams, bearing lamps or images.

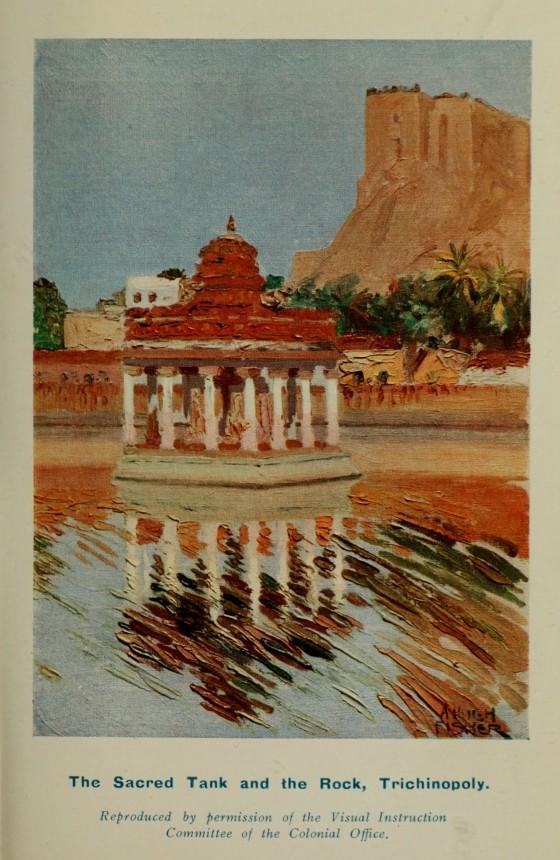

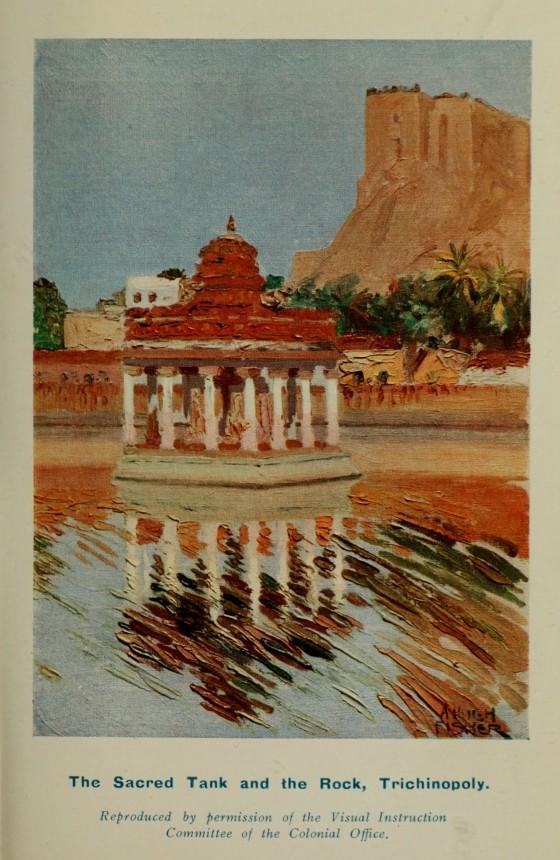

The Sacred Tank and the Rock, Trichinopoly.

It was a vast double door some distance in front of me, beyond a series of wide passages and courts, a colossal door larger than those two of wood and iron at the entrance to the Vatican, where the Swiss guards stand in their yellow-slashed uniforms with the halberds of earlier days, doors with no carving save that of worms and weather, but, like the one before me, more impressive by tremendous size and appearance of strength than the bronze gates of Ghiberti. It was a portal for gods over whose unseen toes I, a pygmy, might crane my neck. The vast perspective in front, the sense of possible inclusion of unknown marvels commensurate with such an entrance, a mystery of shadow towards the mighty roof,—all made me stand and wonder, admiring and amazed. Porch succeeded porch, with statues of the gods, sometimes black with the oil of countless libations, sometimes bright and staring with fresh paint. Dirt mingled with magnificence and modern mechanical invention with the beauty of ancient art. Live men moved everywhere among the old, old gods.

Walking along a corridor, astounded at its large grotesque sculptures, I noticed at my elbow two squatting tailors with Singer sewing-machines, buzzing as with the concentrated industry of a hive of bees. I wished that a prick of the finger would send them all to sleep, tailors, priests, mendicants and the quivering petitions of importunate maimed limbs.

Neither Darius nor Alexander, had they been able to march so far, could have seen Madura, for, after all, these temples are not yet so very old, but Buonaparte— Ah! he of all men should have seen it! I think of him on his white horse, gazing with saturnine inscrutability at the cold waves of carved theogonies surging, tier on tier, up the vast pyramids of the immense gopuras, till the golden roofs of inner gleaming shrines drew him beyond.

Brief—oh how much too brief—was the time permitted me to spend at Madura, for the same night I was to reach Trichinopoly.

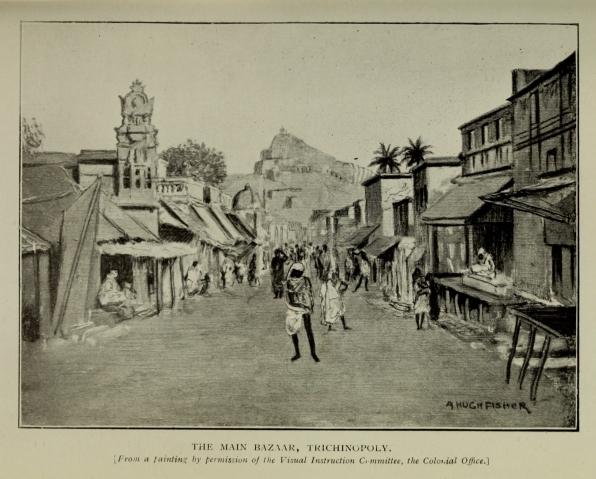

I dressed by lamplight and was on the road just at dawn, driving through the poorer quarter of the town. By a white gateway of Moorish design, erected on the occasion of the last royal visit, and still bearing the legend

—"Glorious welcome to our future Emperor"—I entered the wide street of the main bazaar at the far end of which the "rock" appeared.

Trichinopoly, inside this gate, is entirely a city of "marked" men, the lower castes, together with the Eurasians and the few European officials living outside its boundaries.

The great bare mass which rises out of the plain to a height of 273 feet above the level of the streets below, was first properly fortified in the sixteenth century, under the great Nayakka dynasty of Madura, by which it was received from the King of Tanjore in exchange for a place called Vallam; and after being the centre of much fighting between native powers and French and English, it passed quietly into the hands of the latter by treaty in 1801.

From the roadway at the foot a series of stone stairways leads to the upper street, which encircles the rock and contains a hall from which other stairways lead up to a landing with a hundred-pillared porch on each side of it. In one of these lay in a corner with their legs in air a number of bamboo horses, life-size dummies, covered with coloured cloths and papers for use in the processions. On a still higher landing I reached the great temple (whither the image of Siva was removed from its former place in a rock-temple at the base of the precipice), which Europeans are forbidden to enter.

THE MAIN BAZAAR, TRICHINOPOLY.

By engaging a man in a long argument with Tambusami as interpreter, about certain images visible as far within as I was able to see from the landing, I managed to rouse a desire to explain rightly, so that he made the expected suggestion and took me twenty yards within the forbidden doorway. Deafening noise of "temple music" filled the air, the most strident being emitted from short and narrow metal trumpets.

Twenty yards within that stone doorway guarded by the authority of Government embodied in official placards fastened on the wall! Shall I divulge the mysteries within? Indeed it would fill too many of these pages to spin from threads of temple twilight a wonder great enough to warrant such exclusion of the uninitiated.

Yet another flight of steps leads up round the outside to a final series roughly cut in the rock itself, rising to the topmost temple of them all, a Ganesh shrine, whence there is a grand view over the town and far surrounding plain.

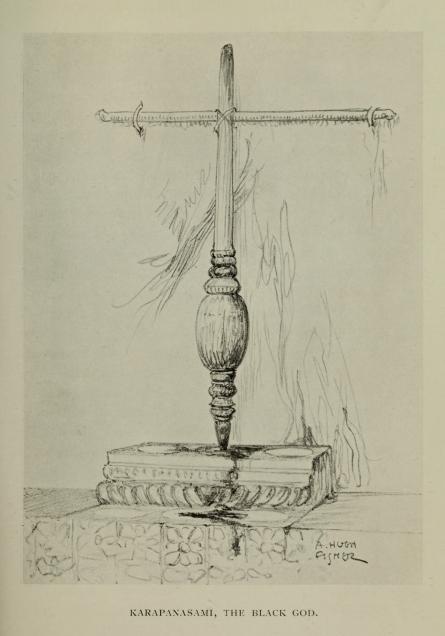

Among the smaller shrines in the streets the one which seemed to me the most curious—was that of the "Black God, Karapanasami," a wooden club or baluster similar in design to those carved in the hands of stone watchmen at temple gates. Wreathed with flower garlands it leaned against the wall on a stone plinth and was dripping with libation oil. I was told that Karapanasami may be present in anything—a brick, or a bit of stone, or any shapeless piece of wood.

Among the native people, quite apart from the would-be guides who haunt the temples, those who speak a little English seem proud to display their knowledge and ready to volunteer information. Before a statue of Kali in a wayside shrine a boy ventured to say he hoped I would not irritate the goddess, adding, "This god becomes quickly peevish; it is necessary to give her sheep to quiet her."

That afternoon I painted the "Tappakulam" or tank at the base of the great rock with the dainty "Mantapam" or stone porch-temple in the middle of it, working from the box seat of a gharry to be out of the crowd, but their curiosity seemed to be whetted the more, and Tambusami was kept busy in efforts, not always successful, to stop the inquisitive from clambering the sides of the vehicle, which lurched and quivered as each new bare foot tried for purchase on the hub of a wheel.

The dazzling brilliancy of the scene was difficult to realize on canvas, for beyond all other elements of brightness a flock of green parrots flying about the roof sparkled like sun-caught jewels impossible to paint.

KARAPANASAMI, THE BLACK GOD.

The next morning I dressed by lamplight, and it was not yet dawn when Tambusami put up the heavy bars across back and front doorways of my room at the dak bungalow for the safety of our belongings during a day's absence. Old Ratamullah, the very large fat "butler," watched us from his own house a little further back in the enclosure, as in the grey light we started to drive to Srirangam, and before the least ray of colour caught even

the top of the Rock we saw a group of women in purple and red robes getting water at a fountain. The large, narrow-necked brass jars gleamed like pale flames, the colour of the words John Milton that shine from the west side of Bow Church in Cheapside.

Outside the houses of prosperous Hindoos I noticed, down upon the red earth, patterns and designs that recalled the "doorstep art" practised by the peasants in many parts of Scotland. The dust of the day's traffic soon obscures the patterns, but at that early hour they had not yet been trodden upon. Brass lamps glimmered in the poorer huts, but we were soon away from Trichinopoly and crossing the long stone bridge over the Cauvery. The river was very wide but by no means full, and scattered with large spaces of bare sand. Over the water little mists like the pale ghosts of a crowd of white snakes curled and twisted in a strange slow dance.