1st

Edition

Berry Ph D Christopher Farquhar Ph D Mary Ann

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/china-on-screen-cinema-and-nation-film-and-culture-s eries-1st-edition-berry-ph-d-christopher-farquhar-ph-d-mary-ann/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Thesis Writing for Master s and Ph D Program Subhash Chandra Parija

https://textbookfull.com/product/thesis-writing-for-master-s-andph-d-program-subhash-chandra-parija/

What you need for the first job besides the Ph D in chemistry 1st Edition Benvenuto

https://textbookfull.com/product/what-you-need-for-the-first-jobbesides-the-ph-d-in-chemistry-1st-edition-benvenuto/

Living an Examined Life Wisdom for the Second Half of the Journey James Hollis Ph D

https://textbookfull.com/product/living-an-examined-life-wisdomfor-the-second-half-of-the-journey-james-hollis-ph-d/

Absence in Cinema The Art of Showing Nothing Film and Culture Series 1st Edition Remes

https://textbookfull.com/product/absence-in-cinema-the-art-ofshowing-nothing-film-and-culture-series-1st-edition-remes/

Discovering the Social Mind Selected works of Christopher D Frith 1st Edition Christopher D Frith

https://textbookfull.com/product/discovering-the-social-mindselected-works-of-christopher-d-frith-1st-edition-christopher-dfrith/

A Country Called Prison Mass Incarceration and the Making of a New Nation 1st Edition Mary D. Looman

https://textbookfull.com/product/a-country-called-prison-massincarceration-and-the-making-of-a-new-nation-1st-edition-mary-dlooman/

Film Studies second edition An Introduction Film and Culture Series Sikov

https://textbookfull.com/product/film-studies-second-edition-anintroduction-film-and-culture-series-sikov/

Atlas of High-Resolution Manometry, Impedance, and pH Monitoring Sarvee Moosavi

https://textbookfull.com/product/atlas-of-high-resolutionmanometry-impedance-and-ph-monitoring-sarvee-moosavi/

The effect of the binary space and social interaction in creating an actual context of understanding the traditional urban space 2nd Edition Ph. D. Candidate Mustafa Aziz Mohammad Amen

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-effect-of-the-binary-spaceand-social-interaction-in-creating-an-actual-context-ofunderstanding-the-traditional-urban-space-2nd-edition-ph-d-

China on Screen CINEMA AND NATION

FILM AND CULTURE SERIES: JOHN BELTON, GENERAL EDITOR

Film and Culture: A series of Columbia University Press

EDITED BY John Belton

What Made Pistachio Nuts? Early SoundComedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic

HENRY JENKINS

Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition oJSpectacle

MARTIN RUBIN

Projections ojWar: Hollywood, AmericanCulture, and World War II

THOMAS DOHERTY

Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy

WILLIAM PAUL

Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy oJthe '950S

ED SIKOV

Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity

JAMES LASTRA

Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts BEN SINGER

Wondrous Difference: Cinema, Anthropology, and Turn-ofthe-Century Visual Culture

ALISON GRIFFITHS

Hearst Over Hollywood: Power, Passion, and Propagandain the Movies

LOUIS PIZZITOLA

Masculine Interests: Homoerotics in Hollywood Film

ROBERT LANG

Special Efficts: Still in Search ojWonder

REY CHOW

Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema

The Cinema ojMax Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure oJWoman

Black Women as Cultural Readers

SUSAN M. WHITE

JACQUELINE BOBO

PicturingJapaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity,Japanese Film

DARRELL WILLIAM DAVIS

Attack ojthe Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema

RHONA J. BERENSTEIN

This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in theJazz Age

GAYLYN STUDLAR

Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond

ROBIN WOOD

The Sounds ojCommerce: Marketing Popular Film Music

JEFF SMITH

Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture

MICHAEl ANDEREGG

Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, '930-'934

THOMAS DOHERTY

MICHELE PIERSON

Designing Women: Cinema, Art Deco, and the Female Form

LUCY FISCHER

Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and AmericanCulture

THOMAS DOHERTY

Katharine Hepburn: Star as Feminist

Silent Film Sound

ANDREW BRITTON

RICK ALTMAN

Home in Hollywood: The Imaginary Geography ojHollywood

ELISABETH BRON FEN

Hollywood and the Culture Elite: How the Movies Became-American PETER OECHERNEY

Taiwan Film Directors: A TreasureIsland

EMILIE YUEH-YU YEH AND DARRELL WILLIAM DAVIS

Shocking Representation: Historical Trauma, NationalCinema, and the Modern Horror Film

ADAM lOWENSTEIN

Chris Berry and Mary Farquhar

China on Screen CINEMA

AND NATION

Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester. West Sussex

Copyright © 2006 Columbia University Press All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Berry. Chris. '959China on screen cinema and nation / Chris Berry and Mary Farquhar_ p. cm. - (Film and culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. [SBN 1}: 978-0-23'-'3706-5 (alk. paper) ISBN 10: 0-231-13706-0 (alk. paper)

[SBN 1}: 978-0-231-13707-2 (pbk. alk. paper) [SBN 10: 0-231-13707-9 (pbk. alk. paper)

1. Motion pictures-China-History. I. Farquhar. Mary Ann. 1949- [I. Title. Ill. Film and culture. PNI993·5·C4B44 2006 2005053930

8

Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Lisa Hamm C 10 9 87 6 5 4 3 2 I P10 98 7 65432

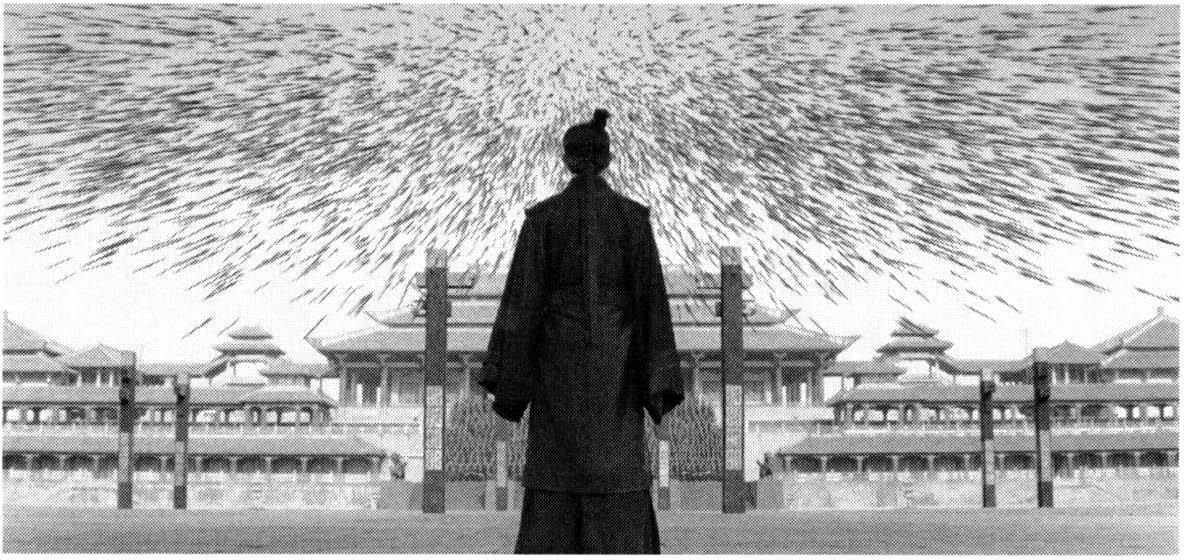

Cover and title page photo: From Hero (2002/2004). directed by Zhang Yimou. visual effects by Animal Logic © EDKO Film. Used with permission. Special thanks to Jet Li. Elite Group Enterprises. and Animal Logic.

List of Illustrations

FIGURES 2.1 a-2.1d. The fisherwoman confronts the foreign merchant in Lin 2exu(1959)

FIGURE2.2 Li Quarud's The Opium War(1963)

FIGURES 2.3a-2.3c The ending of Yellow Earth(1984)

FIGURE2.4 Wen-ching threatened in City oJSadness(1989)

FIGURE2.5 Communicating by notes in City oJSadness

FIGURE3.1 The lovers in Love Eteme(1963)

FIGURE3.2 The woman warrior in A Touch oJ2en(1971)

FIGURE3.3 Tan Xinpei in Dingjun Mountain(1905)

FIGURE3-4 The heroine in The White-haired Girl(1950)

FIGURE3.5 Ke Xiang in Azalea Mountain(1974)

FIGURES 3.6a-3.6e On the execution ground in Azalea Mountain(1974)

FIGURE3.7 Twelve Widows March West(1963)

FIGURE4·1 Tomhoy(1936)

FIGURE4.2 Xiao Yun from Street Angel(1937)

FIGURES 4.3a-4.3c Deathbed scene in Street Angel(1937)

FIGURE4-4 On the town walls in Spring in a Small Town(1948)

FIGURE4.5 Family reunion in Spring in a Small Town(1948)

FIGURE4.6 Xianglin's wife in New Year'sSacrifice(1956)

FIGURE4.7 Oyster Girl(1964)

FIGURES 4.8a-4.8h Family reconciliation in BeautifUl Duckling(1964)

FIGURE4.9 A family meal in Yellow Earth(1984)

FIGURE4.10 Cuiqiao's wedding night in Yellow Earth(1984) I05

FIGURES·l The ending of Two Stage Sisters(1964) II4

FIGURE5.2 Yuehong shows off her ring in Two Stage Sisters(1964) II6

FIGURES S.3a-S.3d Inspired by her teacher in Song of Youth(1959) II7

FIGURE5-4 Joining the Communist Party in Song of Youth(1959) II8

FIGURES s.sa-s.sc Admiring glances in The New Woman(1935) 121

FIGURES s.6a-s.6f At the nightclub in The New Woman(1935) 123

FIGURE5.7 Deathbed scene in The New Woman(1935) 124

FIGURE5.8 Gong Li in Raise the Red Lantern(1991) I28

FIGURE6.1 Kwan Tak-hing as Wong Fei-hung 146

FIGURE6.2 Jackie Chan as Wong Fei-hung in Drunken Master(1978) 147

FIGURE6.3 Chow Yun-fat in A Better Tomorrow 1(1986) 154

FIGURE6-4 Celebrations in The Story ofQiuJu(1992) 161

FIGURES 6.sa-6.sg The final scene in The Story ofQiuJu(1992) 162

FIGURE6.6 Execution in Hero (2002/2004) 166

FIGURE7.1 Airport good-byes in The Wedding Banquet (1993) 177

FIGURE7.2 Simon and Mr. Gao in The Wedding Banquet(1993) 179

FIGURE7.3 The young master rides Jampa in Serfs(1963) 182

FIGURES 7-4a-7-4f Jampa rides the horse in Serfs (1963) 183

FIGURE7.5 The sky burial in Horse Thief(1986) 185

FIGURE7.6 Religious observance in Horse Thief(1986) 186

FIGURE7.7 Adopting Dai ways in Sacrificed Youth(1985) 187

FIGURE8.1 Bruce Lee in The Big Boss(1971) 199

FIGURE8.2 Belt action in The Way of the Dragon(1972) 202

FIGURES 8.3a-8.3c Imitating Bruce Lee and John Travolta in Forever Fever(1998) 221

Acknowledgments

WITHOUT THE support of various funding bodies, this project would not have gotten offthe ground. We are grateful to the Australian Research Council, which supported our work with a three-year Large Grant; and to the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation, which supported our research in Taiwan Mary Farquhar's preliminary work on the project was also supported by the Griffith University Research Grant Scheme. Chris Berry received support from the University of California Berkeley Humanities Research Grant program and the Chinese Studies Center at Berkeley. We would also like to thank David Desser for inviting and persuading us to undertake the project in the first place.

The cooperation ofboth the Taipei and Hong Kong Film Archives was invaluable and fulsome. Their spirit ofpublic access is an inspiration to us all. At the Taipei Archives, successive directors Edmond K. Y. Wong and Winston T. Y. Lee facilitated our access, and Teresa Huang Hui-min helped us daily and in more ways than we can detail here. At the Hong Kong Film Archive, director Angela Tong opened all doors, and Pinky Tam helped us repeatedly and with great patience. Our colleague and friend Hu Jubin both acted as our intermediary with the China Film Archives in Beijing and also helped us to compile our Chinese-language bibliography and film list.

Various colleagues and friends gave us invaluable support and feedback on earlier drafts of chapters: Vishal Ahuja, Geremie Barme, Yomi Braester, Louise Edwards, Kim Soyoung, Lydia Liu, Kam Louie, Ralph Litzinger, Sheldon Hsiao-Peng Lu, Fran Martin, Murray Pope, Sue Trevaskes, Valentina Vitali, Paul Willemen, and Yeh Yueh-Yu. To all of them we are extremely grateful. We know how busy they were and we are grateful for the time they took to read our drafts. A number of research assistants worked on the project at various times and in various roles, all ofthem important and greatly appreciated. They are Salena Chow, Darrell Dorrington, Hong Guo-

Juin, Rosemary Murray, and Maureen Todhunter. Hu Jubin both worked on the manuscript as a research assistant and offered us his generous and fulsome intellectual response and advice. Sue Jarvis compiled the index for us. To them, we offer special thanks.

Earlier versions of sections of some chapters were presented as conference papers and public presentations at the Chinese Cinema Conference at the Baptist University of Hong Kong in 2000; the 18th Law and Society Conference in Brisbane in 2000; Duke University in 2001; the Asian Studies Association Conference in Chicago in 20or; the Modern Chinese Historiography and Historical Thinking Conference at the University of Heidelberg in 20or; the New England Association for Asian Studies Conference at Williams College in 20or; Fudan University in 2002; the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 2002; Carleton College in 2002; the University ofWashington, Seattle, in 2002; the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, in 2002; the Asian Screen Culture: Mobile Genres conference at the Korean National University of Arts in Seoul in 2003; the Global/Local/Exotic: Transnational Production and Auto-Ethnography conference at the University of Hawaii in 2003; the Berkeley Film Seminar in 2004; the "A Lifetime ofDedication: Colin Mackerras and China Studies" conference at Griffith University in 2004; Haverford College in 2004; the Center for Chinese Studies of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in 2004; and as the 2004 Mcgeorge Cinema Lecture at the University ofMelbourne. We are grateful for the invitations to speak, and for the questions and discussions in response to these presentations, all ofwhich helped us to further develop the work.

Earlier versions of sections of some chapters have also been published elsewhere, and the responses we received helped us to improve them. An earlier version of chapter 1 appeared as "From National Cinemas to Cinema and the National: Rethinking the National in Transnational Chinese Cinemas," in Journal ofModem Literature in Chinese 4.2 (2001). Sections of chapter 3 appeared as "Shadow Opera: Towards a New Archaeology of the Chinese Cinema," in PostScript 20.2-3 (2001). A section of chapter 5 appeared in an earlier version and in Chinese as "Look Again: Using Chinese Examples to Rethink Gender in the Cinema," in Ershiyi Shiji (TwentyFirst Century, Hong Kong), no. 68 (2001) An extended reading of Zhang Yimou's Hero in chapter 6 is to be published as a chapter in Graeme Harper and Jonathan Rayner's The Landscapes ofFilm: Cinema and Its Cultural Geography (Detroit: Wayne State University Press). An extended analysis ofthe discussion of Bruce Lee in chapter 8 will appear as "Stellar Transit: Bruce Lee's Body, or, Chinese Masculinity in a Transnational Frame," in Modernity Incarnate, edited by Larissa Heinrich and Fran Martin (Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, 2005).

ACKNOWLEDG

We thank our editors at Columbia University Press (Jennifer Crewe and Roy Thomas) and at Hong Kong University Press (Colin Day) and their colleagues for their promptness, detailed attention, support, and patience. We also thankthe editors at other presses that showed interest in this project and gave us much good advice, and the university press anonymous readers for their reports. Any remaining problems are, of course, our own responsibility. Finally, we'd like to thank each other! Coauthorship is a difficult task, but we both learned enormously from each other and stayed friends throughout this long and demanding project.

A Note on Translation and Romanization

THIS BOOK uses the pinyin system for romanizing Chinese characters unless common usage makes an alternative more familiar and therefore user-friendly.

Regarding film titles, there are many different ways of translating Chinese film titles into English and many different ways of romanizing Chinese characters into Latin letters. In this book, we have decided not to include any Chinese characters in the main body ofthe text. For film titles, we have used the English export titles of the films wherever they are known. However, because these titles often vary from the original Chinese titles, we have included a pinyin romanization ofthe Mandarin Chinese rendering of the original title in parentheses after the first appearance of each Chinese-language film title in the text. There is also a film list appended at the back of the book, which does include the Chinese character version of the original title.

For books, articles, and other bibliographical items, pinyin romanization of Mandarin Chinese is used in the endnotes for Chinese-language items. The bibliographies at the end ofthe book are divided into European and Chinese-language bibliographies. Items in the Chinese-language bibliography are ordered alphabetically, according to the pinyin romanization of the author's name. However, the full Chinese-character version of each entry is given.

Finally, for the names of internationally known places and people, we have used the version of their name in general circulation rather than the pinyin romanization, e.g., Hou Hsiao Hsien rather than Hou Xiaoxian. For all terms, pinyin romanization has been used.

China on Screen CINEMA AND NATION

Introduction: Cinema and the National

JACKIE CHAN'S 1994 global breakthrough film Rumblein the Bronx is a dislocating experience in more ways than one. This is not just because ofthe gravity-defying action, or because Jackie is far from his familiar Hong Kong. Set in New York but shot in Vancouver, the film shows a Rocky Mountain backdrop looming between skyscrapers where suburban flatlands should be. The film also marks a watershed in Chan's efforts to transform himself from Hong Kong star to global superstar and his character from local cop to transnational cop. Funded by a mix of Hong Kong, Canadian, and American companies, Rumble in the Bronx is an eminently transnational film. In its North American release version, it cannot even be classified using the currently fashionable term for films from different Chinese places, "Chinese-language film" (huayu dianying):I not only are the settings and locations far from China but all the dialogue is in English.2 Indeed, one fan claims Rumble in the Bronx for the United States when he complains that, "From the very start you will realize that this film seems to be trying to set a record for worst dubbing in a supposedly 'American' film."3

While it might seem a stretch to imagine even the North American release version of Rumble in the Bronx is an American film, Rumble in the Bronx certainly illustrates how futile it can be to try and pin some films down to a single national cinema. However, although Rumble in the Bronx demands to be understood as a transnational film, the national in the transnational is still vital to any account ofits specificity. It says something both about the importance ofthe American market to Chan and the aspirations of Hong Kong's would-be migrants in the run-up to China's 1997 takeover that Chan's character, Keung, visits the United States (rather than Nigeria or China, for example).

Even though Jackie Chan successfully vaulted to global stardom in the wake of Rumble in the Bronx, his cultural and ethnic Chineseness and his

INTRODUCTION: CINEM A AND THE NATIONAL

Hong Kong identity remain-not only recognized by fans but also as significant elements that he exploits for the jokes, action, and narratives of his films. In Rush Hour (1998), Chan's first commercially successful Hollywood film, his cop persona is again assertively from Hong Kong, as he saves the PRC (People's Republic of China) consul's daughter in Los Angeles from Hong Kong gangsters with the help of a maverick black LAPD sidekick. As will be discussed in chapter 6, Rush Hour blends regional, cultural, and political Chinese nationalism. This Hollywood movie proclaims both Hong Kong Chinese and blacks as outsiders, who nevertheless save the day for the great and good: the USA, the PRC, and Hong Kong as well as the consul, the FBI, the LAPD, and even China's archaeological heritage, on display in Los Angeles after being saved from a corrupt, British colonial administrator in league with Hong Kong triads.

This book examines some of the many and complex ways the national shapes and appears in Chinese films. Our core argument is twofold. First, the national informs almost every aspect of the Chinese cinematic image and narrative repertoire. Therefore, Chinese films-whether from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, the diaspora, or understood as transnational-cannot be understood without reference to the national, and what are now retrospectively recognized as different Chinese cinematic traditions have played a crucial role in shaping and promulgating various depictions ofthe national and national identity. Second, as the challenge of locating Rumble in the Bronx and Rush Hour demonstrates, the national in Chinese cinema cannot be studied adequately using the old national cinemas approach, which took the national for granted as something known. Instead, we approach the national as contested and construed in different ways. It therefore needs to be understood within an analytic approach that focuses on cinema and the national as a framework within which to consider a range ofquestions and issues about the national.

Why is the national so central to Chinese cinemas? Put simply, ideas aboutthe national and the modern territorial nation-state as we know them today arrived along with the warships that forced "free trade" on China in the mid-nineteenth-century opium wars. Both the national and the modern territorial nation-state were part ofa Western package called modernity, as was cinema, which followed hot on their heels. Like elsewhere, when Chinese grasped the enormity ofthe imperialist threat they realized that they would have to take from the West in order to resist the West. The nation-state was a key element to be adopted, because this modern form ofcollective agency was fundamental both to participation as a nation-state in the "international" order established by the imperialists and to mobilizing resistance.4

However, as Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto pointedly indicates, scholars are less sure about how to study cinema and the national than they used to be:

"Writing about national cinemas used to be an easy task: film critics believed all they had to do was to construct a linear historical narrative describing a development of a cinema within a particular national boundary whose unity and coherence seemed to be beyond all doubt."5 Once, it might have been possible to produce a list of elements composing something called "traditional Chinese culture" or "Chinese national culture," or even some characteristics constituting "Chineseness." Then we could have tried to see how these things were "expressed" or "reflected" in Chinese cinema as a unified and coherent Chinese national identity with corresponding distinctly Chinese cinematic conventions This would then constitute a "national cinema."

In this era of global capital flows, multiculturalism, increasing migration, and the World Wide Web, it is clear that the national cinemas approach with its premise ofdistinct and separate national cultures would be fraught anywhere. But in the Chinese case, its difficulty is particularly evident. Today, "China" accommodates a multitude of spoken languages, minority nationalities, former colonies, and religious affiliations. Until 1991, it designated a territory claimed by two state powers: the People's Republic of China with its capital in Beijing and the Republic of China currently based on Taiwan. Even when President Lee Teng-hui of the Republic of China made reforms in 1991 removing the Republic's claim to the territory governed by the mainland, it was still stated that, "the ROC government recognized the fact that two equal political entitles exist in two independent areas ofone country.,,6 A glance at the Chronology at the back ofthis book shows that China has been through numerous territorial reconfigurations over the last century-and-a-half, and has spawned a global diaspora.

With these circumstances in mind, how do we need to rethink the cinema's connection to the national and ways of studying it? This introduction attempts to answer this question. On the basis of our exploration of the issues discussed below, we argue for the abandonment ofthe national cinemas approach and its replacement with a larger analytic framework of cinema and the national. Instead of taking the national for granted as something known and unproblematic-as the older national cinemas model tended to-our larger analytic framework puts the problem ofwhat the national is-how it is constructed, maintained, and challenged-at the center. Within that larger framework, the particular focus ofthis book is on cinematic texts and national identity. But we hope this book can serve as both an embodiment of our larger argument and a demonstration of the kind of studies that can come out ofsuch a shift.

Although it may sound odd at first, the transnational may be a good place to start the quest to understand what it means to speak ofcinema and the national as an analytic framework. As if taking a lead from Mitsuhiro

Yoshimoto's critique, Sheldon Hsiao-Peng Lu begins his introduction to Transnational Chinese Cinemas by characterizing the anthology as "a collective rethinking of the national/transnational interface in Chinese film history and in film studies."7 He goes on to trace how the cinema in China has developed within a transnational context. As in most of the world, it arrived in the late nineteenth century as a foreign thing. When Chinese began making films, they were heavily conscious that the Chinese market was dominated by foreign film, and increasingly they saw the cinema as an important tool for promoting patriotic resistance to Western and Japanese domination of China. Following the establishment ofthe People's Republic, most foreign film was excluded and an effort was made to "sinicize" the cinema Meanwhile, the cinemas of Taiwan and Hong Kong came to depend on diasporic Chinese audiences. Most recently, Chinese cinemas have participated in the forces of globalization through coproductions and the work ofemigres in Hollywood. With this history in mind, Lu concludes, "The study ofnational cinemas must then transform into transnational film studies."g

This is a very suggestive insight. The essays in Lu's anthology focus on the transnational dimension of transnational film studies. But to use this insight as a way into our project, we need to ask where the national is in transnational Chinese cinemas and in transnational film studies. This question can be addressed by spinning a number of questions out of Lu's comment.

What does "transnational" mean and what is at stake in placing the study of Chinese cinema and the national within a transnational framework?

The term transnational is usually used loosely to refer to phenomena that exceed the boundaries of any single national territory. However, there is a tension around the term, which stems from its relation to the idea of "globalization." In many uses, "transnationalism is a process ofglobal consolidation" and transnational phenomena are understood simply as products of the globalizing process.9 For example, while the multinational corporation is headquartered in one country and operates in many, "a truly transnational corporation is adrift and mobile, ready to settle anywhere and exploit any state including its own, as long as the affiliation serves its own interest. "10

In contrast, other writers use "transnational" to oppose the rhetoric of universality and homogenization implied in the term globalization. For them, the "transnational" is more grounded. It suggests that phenomena exceeding the national also need to be specified in terms ofthe particular places and times in which they operate, the particular people they affect, and the particular ways they are constituted and maintained.II

The focus on China in Chinese film studies precludes assumptions about global universality (although certainly not the impact of capitalist "globalization"). However, the issue of homogeneity versus specificity remains crucial to the question ofhow we might understand the transnational in "transnational Chinese cinemas." One possibility is that the territorial nation-state and national cinema as sites of Chineseness are being eclipsed by a higher level of unity and coherence, namely a Chinese cultural order that is transnational. This would be the kind of culturalism that supports Western discourses ranging from Orientalism (as critiqued by Edward Said) and Samuel Huntington's "clash ofcivilizations" to Chinese discourses on Greater China (Da Zhonghua) and Tu Weiming's "Cultural China."12

The alternative is that the transnational is understood not as a higher order, but as a larger arena connecting differences, so that a variety of regional, national, and local specificities impact upon each other in various types of relationships ranging from synergy to contest. The emphasis in this case is not on dissolving the distinctions between different Chinese cinemas into a larger cultural unity. Instead, it would be on understanding Chinese culture as an open, multiple, contested, and dynamic formation that the cinema participates in. Key to understanding these two different trajectories for the deployment of the "transnational" is the question of whatthe "national" in the word transnational means. This leads to a second question.

What does the "national" mean?

Understandings of Chinese transnationality as a higher level of coherence above the nation-state reinstate the modern nation under a different name. Whether Chinese or Western in origin and whether praising or critical, they simply deploy culture or ethnicity rather than territorial boundaries as the primary criterion defining the nation. The distinction here is between an ethnic nation and a nation-state. Yet both forms retain the idea ofthe nation as a coherent unity. This coherent unity is also usually assumed in the concept and study of national cinemas But it is precisely this understanding of the nation that has come under interrogation in English-language academia over the last twenty years or so, and the directions this critique has taken must guide efforts to transform the study of national cinemas into the study ofcinema and the national

The rethinking of the nation and the national in a general sense has produced a very large body of literature. However, three major outcomes are especially relevant to the arguments in this book. First, the nation-state is not universal and transhistorical, but a socially and historically located form of community with origins in post-Enlightenment Europe; there are other ways of conceiving of the nation or similar large communities. Sec-

ond, if this form of community appears fixed, unified, and coherent, then that is an effect that is produced by the suppression of internal difference and blurred boundaries. Third, producing this effect of fixity, coherence, and unity depends upon the establishment and recitation of stories and images-the nation exists to some extent because it is narrated.

Before elaborating on these points, the implications of these outcomes must be briefly considered. For those committed to the nation, the idea that the nation is constructed can seem to be an attack on its very existence. And for those opposed to the nation, this can seem to presage its imminent demise. Yet ifthe metaphor ofconstruction implies potential demolition, it also suggests that new nations can be built and existing nations renovated. In other words, how this more recent discourse on the nation gets used is not immanent to that discourse, but dependent upon social and institutional power relations.

One reason for the frequent assumption that recent thought constitutes an attack on the nation is the title that looms over this entire field: Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson.13 In a recent survey ofwriting on national cinemas, Michael Walsh finds that "ofall the theorists ofnationalism in the fields of history and political science, Anderson has been the only writer consistently appropriated by those working on issues ofthe national in film studies."14 However, Anderson does not use "imagined" to mean "imaginary," but to designate those communities too large for their members to meet face-to-face and which therefore must be imagined by them to exist. He also distinguishes between the modern nation-state as one form of imagined community and others, including the dynastic empire. For example, he points out that empires are defined by central points located where the emperor resides, whereas nation-states are defined by territorial boundaries. Those living in empires are subjects with obligations, whereas those living in nation-states are citizens with rights, and so forth.'5 After Anderson's watershed intervention, the nation no longer appears universal and transhistorical but as a historically and socially located construction. Indeed, ifMichael Hardt and Antonio Negri are right, our transnational era is already a new age ofempire.,6

Anderson's intervention also demands attention to distinctions all too easily collapsed in the thinking that took the nation for granted and long characterized the national cinemas approach. As well as the distinction between an ethnic or cultural nation and a territorial nation-state made above, there is also the question of the concept of a biologically distinct nation. However, although most cultural nations and nation-states retain links to ideas ofrace, it is difficult to assert that they are one and the same after the notorious example of the Holocaust and Nazi rule in Germany. This then raises the issue of internal divisions and blurred boundaries of nations,

INTRODUCTION: CINEM A AND THE NATIONAL

both ethnic and territorial. Although members ofnations are (supposedly) constituted as citizens with equal rights and obligations, this individual national identity is complicated by citizens' affiliations to other local and transnational identity formations, including region, class, race, religion, gender, and sexuality, to name but a few. These issues and the questions and problems arising from them are foreclosed upon in a national cinemas approach that takes the national for granted as something fixed and known. But with the shift to a framework ofcinema and the national that puts the focus on the national as a problem, they take center stage.

Why does this proliferation of different affiliations for citizens create tensions within the modern nation-state and provoke efforts at containment, when the same situation was commonly accepted in empires? In empires, agency is understood to lie with a deity, an absolute monarch, or a hierarchy ofdifferently empowered subjects. In these circumstances, the various differences among the people in an empire are not so crucial. But the modern nation-state is understood as a collective agency composed of its citizens, whether acting through the ballot box, the dictatorship of the proletariat, or some other mechanism. In these circumstances, loyalties to other collectivities created by diverse identity formations threaten the ability of "the people" to act as an agent, and must be managed either through suppression or careful containment.

However, this is a "catch-22." As Homi Bhabha points out, quite apart from all the other tensions, producing the nation as collective agency in itself leads to a split between the people as objects and as subjects of the discourse that depicts them.I7 So, in addition to the differentiation of nations according to defining criteria such as culture, territory, and race, we also need to distinguish between nation as subject or agency and nation as object. This distinction cannot necessarily be reduced to that between the state (subject) and people (object), as neither of these entities is a stable given, nor is there always a clear line between them.

It is the need to produce and maintain citizenry as a collective national subject in the face of competing and challenging forces that leads Ann Anagnost to write that the nation is "an 'impossible unity' that must be narrated into being in both time and space," and that "the very impossibility of the nation as a unified subject means that this narrating activity is never final."r8 To understand this endless narrating activity in the case of the collective national subject, Judith Butler's work on the individual subject-"me"-may be useful. She argues that the individual subject is not a given but produced and, furthermore, that it is produced through the rhetorical structures of language. Here she notes the Althusserian idea of interpellation. Interpellation is the hailing of the subject, where language calls upon us to take up positions that encourage psychological identifica-

tion and social expectations of who we are. An example might be when heterosexual couples repeat the marriage vows read out to them by the celebrant. Butler terms this process "performative"-doing is being. Her particular contribution to the understanding ofthis performative process is to ground it in history. She notes that each citation of a subject position is part of a chain that links different times and spaces. This causes it to be necessarily different from the previous citation in locally determined ways Butler's privileged example is drag as a citation ofgender that undermines the citation it repeats. Another clear example would be the way in which some members of the Chinese business and political communities cite Confucianism today. Although the rhetorical form oftheir citation declares continuity, there must be difference because premodern Confucianism despised commerce.

Butler's ideas on performativity and citation give us tools for analyzing the paradox of discourses that declare the national subject as fixed and transcendent yet are marked by contradiction, tension, multiple versions, changes over time, and other evidence of contingency and construction.19 Furthermore, her insight about the impact on the citation ofthe different times and spaces it occurs in is particularly pertinent to colonial and postcolonial environments. When the European concept ofthe modern nationstate is imposed onto and/or appropriated into other environments, it is likely to be made sense ofthrough a framework composed ofother already circulating concepts of imagined community. For example, Tsung-I Dow has given an account of the impact of the Confucian environment upon Chinese elaborations ofthe modern nation-state.20

What happens to "national cinemas" in this new conceptual environment?

The rethinking ofthe nation discussed above has combined with changes in cinema studies to undermine the expressive model ofnational cinemas. It is no longer possible to assume that the nation is a fixed and known bundle of characteristics reflected directly in film. In cinema studies itself, there is growing awareness of the dependence of nationally based film industries upon export markets, international coproduction practices, and the likelihood that national audiences draw upon foreign films in the process ofconstructing their own national identity.21

In these circumstances, it becomes proper to talk about the reconfiguration of the academic discourse known as "national cinemas" as an analytic framework within which to examine cinema and the national. Just as Anderson's work grounds the nation as a particular type ofimagined community within Europe, national cinemas reappear in this framework as a set ofinstitutional, discursive, and policy projects first promoted by certain

interests in Europe and usually defined against Hollywood. The framework of cinema and the national extends beyond these specific national cinema projects. It also includes the idea ofa national cinema industry, which concerns film production within a particular territory and the policies that affect it but might not include participation in the production of a national culture. Other areas include the activities of a national audience within a particular territory, censorship, regulation within a particular territory, and so on. This broadening ofwork on national cinemas to include the cinema as an economic and social institution shapes Yingjin Zhang's important new chronological history of Chinese national cinema.22

Unlike Yingjin Zhang's book, many other examples of the institutional approach to national cinemas also abandon analysis offilms, their dissemination of images and narratives about the national, and their role in the construction of national identity. There is no question that the challenge to the expressive model ofnational cinemas has drawn interest away from national imagery and identity. Some writers have even claimed that with the discrediting ofnational identity as something fixed and transcendent, it would be better to abandon the examination of cinema and national identity, and just speak about common cinematic tropes and patterns as "conventions" within the cinema ofcertain territorial nations.23

However, such a move would perform a sort of short circuit that forecloses consideration ofwhat is most crucially at stake in cinematic significations of the national, namely the production of the collective identity and, on its basis, agency. Relying on the rethinking ofthe national subject as located and narrated into existence outlined in the previous section, this book returns to national identity in the cinema, not as a unified and coherent form that is expressed in the cinema but as multiply constructed and contested. Furthermore, just as preexisting Chinese ideas of community provide a framework through which the imported European nation is made sense of, we are also interested in how the imported discursive techniques of the cinema work with and are worked upon by existing local narrative patterns and tropes, creating cinematic traditions in which Chinese national identities are cited and recited. Each chapter considers a particular aspect ofthis process.

The scope of the book is wide, both socially and historically. This is necessary to capture the complexity ofthe national in its various Chinese configurations. Efforts to recast China as a modern nation-state coincide with the century of cinema, making it desirable to range from among the earliest surviving films to the most recent. Two intertwined themes became increasingly clear as we watched film after film. First, there are patterns that appear and reappear in new forms across Chinese-language cinemas over the last century. Martial arts movies are just one example: banned in

mainland China in 1931, they remorphed in Hong Kong and Taiwan from the middle ofthe twentieth century to be reclaimed by the People's Republic in the 1980s with the ascendancy of Jet Li. Filmmakers and audiences are aware of this heritage. Thus, for example, bamboo forest fight scenes in both Taiwan-American director Ang Lee's CrouchingTiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and mainland director Zhang Yimou's House ofFlying Daggers (2004) pay homage to the extraordinary combat scene in the bamboo forest in King Hu's A Touch ofZen (1971). Second, the transformations in these patterns that cut across the cinema are linked to different ideas about the national and nationhood that have appeared in different Chinese places at different times. The range of these ideas cannot be grasped by only attending to one Chinese space and cinema, such as the People's Republic or Taiwan or Hong Kong. Therefore, we have attempted to bring films from different Chinese societies and cinemas together in each chapter.

The topics ofeach chapter emerged in the process ofexploring both the Chinese and English-language writings on Chinese cinema, and the films themselves. The most significant and consistent intersections with the national formed the basis for the following seven chapters. In the next chapter, we look at the intersection ofcinematic time and the time ofthe nation. Chapters 3 and 4 focus on the intersection ofthe national with indigenous and imported cultures to produce distinctive modes of cinema opera and melodramatic realism. Chapters 5 and 6 examine the intersection of gender and the national in the production ofmodern Chinese femininity and masculinity. Chapter 7 extends that discussion into the intersection ofthe national and ethnicity in Chinese cinema, and our final chapter returns to the transnational to examine how the national is recast in a globalizing cinematic environment. In order to understand these topics, we have explored recentwork in cinema studies, Chinese studies, and other related fields. We begin each chapter with a section that explains the framework of thought that we have developed to approach the topic under consideration.

Chapter 2 examines time in the cinema Where many have focused on cinematictime as a philosophical concept, ourinterest is intime andthe formation ofnation and community. We demonstrate that cinematic time and the national are configured in at least three major ways. Each corresponds to a different perspective on the nation-state and modernity. First, national history films operate from within the logic and vision of the modern nation-state to produce time as linear, progressive, and logical. Often, as in the example ofthe Opium War films examined, these narratives start from a moment that produces national consciousness in humiliation. Prompted by crises in modernity, a second group of films takes a critical look back at the projects of the modern nation-state. Our primary examples are the post-Cultural Revolution film Yellow Earth (1984) in the People's Republic

of China and the post-martial law film City ofSadness (1989) in Taiwan. Finally, and possibly most radically, our third group registers a yearning for lost pasts before modernity-and maybe new futures-from within modernity itself. Films like In the MoodforLove (2000) engage haunted time, running wormholes in and out ofmodernity to ruin the linear logic ofnational progression and mark the persistence ofnonmodern formations.

Chapters 3 and 4 turn to Chinese cinematic modes. A mode transcends individual films, genres, periods, and territories as the broadest category of resemblance in film practice. We argue that the Chinese cinema exhibits two main modes whose variations must be explained within contexts of different formations ofthe national: the operatic mode, which began with opera film as a statement ofcultural nationalism, and the realist, which was intimately linked to modernity and nation-building.

Chapter 3 explores the operatic mode as the syncretic core running through Chinese cinemas. We call this mode "shadow opera." It relies on cultural spectacles that link the premodern and the modern in a Chinese cinema of attractions, and appears in a range ofgenres from opera film to martial arts movies overthe last century. These genres are seen as explicitly Chinese, but they vary according to different-and often contested-understandings of Chineseness. The earliest opera films sinicize the foreign art form of the cinema for cultural and commercial purposes, just as the nation-state itselfhad to be made Chinese in the process of appropriation. Later revolutionary operas, like The White-haired Girl (1950) and Azalea Mountain (1974), appropriate and transform opera as a national cultural form in the pursuit of a proletarian nation. Shadow opera operates below, within, and beyond the idea of the nation-state. Early Taiwan films, based on a local operatic form called gezaixi, were reinterpreted in the 1990S as a nationalist form that projects an independent Taiwan identity. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon borrows a mythic sense of the Chinese national to originate a new form of transnational and diasporic identity, while Hero (2002) borrows the same generic form to promote a vision ofthe territorial and expanding Chinese nation-state back in the mists oftime.

In chapter 4, we argue that Chinese reformers adopted realism as the hegemonic and "official" mode ofmodernity in the Chinese cinema. Operatic modes were frequently proscribed as "feudal" or dismissed as crassly commercial. Realist modes were considered both contemporary and modern. However, realist modes were almost always qualified by melodramatic conventions that, in their different forms, proffered different views of the national through stories of the family and home. In pre-1949 China, films of divided families, such as Tomboy (1936), Street Angel (1937), and Spring in a Small Town (1948), reflect the deep anxiety about a China divided by migration, war, and politics in conservative, leftist, and politically

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Talonisäntä: säikähti upseerin raakaa äänensävyä. Se ilmeni hänen vapisevassa äänessään, kun hän vastasi.

»Minä… minä en pidä talossani mitään kapinallisia, sir. Tämä herrasmies…»

»Voinhan itsekin ottaa siitä selvän.» Kapteeni astui kolisten vuoteen luo ja loi karskin katseen kalpeakasvoiseen sairaaseen.

»Ei näy olevan tarpeellista tutkia, miten hän on tähän tilaan joutunut ja mistä hän on haavansa saanut. Kirottu kapinoitsija. Se on selvä.» Hän antoi käskyn rakuunoilleen. »Viekää hänet ulos täältä, pojat!»

Herra Blood astui vuoteen ja rakuunain väliin.

»Ihmisyyden nimessä, sir», sanoi hän hieman suuttuneella äänellä. »Me olemme Englannissa emmekä Tangerissa. Tämän herrasmiehen tila on vakava. Jos häntä käytte liikuttamaan, saattaa olla henki kysymyksessä.»

Kapteeni Hobart näytti huvittuneelta.

»Oh, pitäisikö minun olla huolissani kapinoitsijain hengestä! Piru vieköön! Luuletteko, että viemme hänet pois hänen tervehtymisensä vuoksi? Westonin ja Bridgewaterin välinen tienvarsi on istutettu täyteen hirsipuita ja hän saa paikan yhdessä niistä yhtä hyvin kuin joku muukin. Eversti Kirke aikoo opettaa näille nonkonformistisille hölmöille sellaisen läksyn, etteivät he sitä unohda miespolviin.»

»Aiotteko hirttää ilman edelläkäypää tuomiota? Siinä tapauksessa olen sittenkin erehtynyt. Olemme kuin olemmekin Tangerissa, josta teidän rykmenttinnekin on.»

Kapteeni katsoi lääkäriä kiiluvin silmin. Hän tarkasti häntä kiireestä kantapäähän ja pani merkille hänen hoikan, vilkkaan olemuksensa, ylpeän pään asennon ja sen arvonantoa vaativan ilmeen, joka oli herra Bloodille ominainen, ja sotilas tunsi sotilaan. Kapteenin silmät kapenivat. Jälleentunteminen tuli täydelliseksi.

»Kuka piru te olette?» puhkesi hän sanomaan.

»Nimeni on Blood, sir — Peter Blood. Suosittelen itseäni.»

»Aivan niin, Jumaliste! Siinäpä se. Tehän olitte ranskalaisten palveluksessa kerran, eikö niin?»

Jos herra Blood hämmästyi, niin ei hän ainakaan sitä ilmaissut.

»Niin olin.»

»Minäpä muistan teidät — viisi vuotta sitten tai ehkäpä enemmänkin. Te olitte silloin Tangerissa.»

»Se pitää paikkansa. Tunsin teidät, kapteeni.»

»Tottavie, nyt joudutte uudistamaan tuttavuutenne kanssani.» Kapteeni nauroi epämiellyttävästi. »Mikä teidät on tänne tuonut?»

»Tämä haavoittunut herrasmies. Minut noudettiin hoitamaan häntä. Olen lääkäri.»

»Te — lääkäri?» Iva soi hänen kerskuvassa äänessään hänen kuullessaan sellaisen valheen, kuten hän luuli.

»Medicinae baccalaureus», sanoi herra Blood.

»Älkää tyrkyttäkökään minulle ranskaanne, mies», säväytti Hobart.

»Puhukaa englantia!»

Herra Bloodin hymy harmitti häntä.

»Olen lääkäri ja harjoitan ammattiani Bridgewaterin kaupungissa.»

Kapteeni hymähti pilkallisesti.

»Jonne te jouduitte matkallanne Lyme Registä seuratessanne äpärä-herttuaanne.»

Nyt oli herra Bloodin vuoro hymähtää pilkallisesti.

»Jos teidän järkenne olisi yhtä vahva kuin teidän äänenne, niin te varmaan olisittekin niin suuri herra kuin luulottelette olevanne.»

Hetkeksi jäi rakuuna sanattomaksi. Hänen kasvonsa kävivät tummanpunaisiksi.

»Saatte vielä nähdä, että olen kyllin suuri hirttääkseni teidät.»

»Miksipä ei. Tapanne ja ulkonäkönne muistuttavat vahvasti pyöveliä. Mutta jos aiotte sovittaa ammattianne potilaaseeni nähden, niin voi käydä niin, että saatte hamppuköyden omaan kaulaanne. Hän on sitä lajia, jota te ette pysty hirttämään ilman että siitä kysytään. Hänellä on oikeus vaatia tutkimusta ja vieläpä omien pääriensä puolelta.»

»Pääriensä?»

Kapteeni hämmästyi kolmea viimeistä sanaa, joita herra Blood oli korostanut.

»Varmastikin olisi kuka hyvänsä, paitsi hölmö tai raakalainen, ensin kysynyt hänen nimeään ennen kuin määräsi hänet

hirtettäväksi. Tämän herran nimi on lordi Gildoy.»

Sitten puhui lordi itsekin puolestaan heikolla äänellä.

»En tahdo salata yhteistoimintaani Monmouthin herttuan kanssa. Vastaan seurauksista. Mutta jos suvaitsette, teen sen vasta laillisen tuomion perusteella — jonka päärini langettavat, kuten tohtori sanoi.»

Heikko ääni vaikeni ja seurasi hetken hiljaisuus. Kuten tavallisesti kerskailevissa miehissä, oli Hobartissakin syvemmällä hyvä annos arkuutta. Hänen ylhäisyytensä säädyn kuultuaan se vaikutti häneen voimakkaasti. Orjamaisena nousukkaana hän tunsi pelonsekaista kunnioitusta arvonimiä kohtaan. Sitä paitsi hän pelkäsi everstiään, sillä Percy Kirke ei ollut hellävarainen erehdyksen tehneitä kohtaan.

Viittauksella keskeytti hän miestensä aikomuksen. Hänen täytyi saada miettiä. Huomattuaan sen lisäsi herra Blood hänelle miettimisen aihetta.

»Muistakaa myös, kapteeni, että lordi Gildoylla saattaa olla torypuolueenkin keskuudessa sukulaisia ja ystäviä, joilla ehkä olisi yhtä ja toista sanottavaa eversti Kirkelle, jos häntä käsiteltäisiin kuten tavallista pahantekijää. Olkaa siis varovainen, kapteeni, taikka punotte, kuten jo sanoin, köyttä oman kaulanne varalle tänä aamuhetkenä.»

Kapteeni kohautti ylimielisesti olkapäitään varoitukselle, mutta toimi yhtäkaikki sen mukaisesti.

»Nostakaa vuode hartioillenne ja kantakaa hänet Bridgewateriin», hän sanoi miehilleen. »Sijoittakaa hänet vankilaan, kunnes saan

ohjeita, miten menetellä hänen kanssaan.»

»Hän ei ehkä kestä hengissä matkan päähän», vastusteli Blood. »Hän on kovin heikko.»

»Sen pahempi hänelle. Minun tehtävänäni on ottaa kiinni kapinoitsijat.» Hän varmensi käskyään viittauksella. Kaksi miestä tarttui vuoteeseen ja kääntyi lähtemään. Gildoy teki heikon yrityksen ojentaa kättään herra Bloodia kohti. »Sir», sanoi hän, »jään teille suureen velkaan. Jos elän, niin koetan maksaa sen.»

Herra Blood kumarsi vastaukseksi ja sanoi sitten kantajille:

»Kantakaa häntä varovasti. Hänen eloon jäämisensä riippuu siitä.»

Kun lordi oli kannettu pois, kävi kapteeni ripeästi asioihin käsiksi. Hän kääntyi talonpojan puoleen.

»Mitä muita kirottuja kapinallisia teillä on talossanne?»

»Ei ketään muita, sir. Hänen ylhäisyytensä…»

»Olen selvinnyt lordista toistaiseksi. Selvittelen välini teidän kanssanne heti kun olen tarkastanut talonne. Ja jumaliste, jos olette valehdellut minulle…» Hän keskeytti antaakseen vihaisen määräyksen sotilailleen. Neljä rakuunaa meni ulos. Heti sen jälkeen kuului heidän meluava liikehtimisensä viereisestä huoneesta. Sillä välin etsiskeli kapteeni hallissa koputellen pistoolinsa perällä seinälaudoitusta.

Herra Blood arveli, ettei viivytteleminen häntä enää hyödyttänyt.

»Luvallanne toivotan teille hyvää huomenta», sanoi hän.

»Luvallani jäätte paikallenne hetkiseksi», käski kapteeni.

Herra Blood kohautteli hartioitaan ja istuutui. »Te olette ikävystyttävä», virkkoi hän. »Ihmettelen, ettei everstinne vielä ole huomannut sitä.»

Mutta kapteeni ei kuunnellut häntä. Hän oli kumartunut lattiaan ja otti siitä tahraantuneen ja tomuisen lakin, johon oli pistetty tammenlehvä. Se oli jäänyt lähelle sitä vaatekomeroa, jonne onneton Pitt oli piiloutunut. Kapteeni hymyili häijyä hymyä. Hän kiersi katseellaan huonetta pysähtyen ensin isäntään, siirtyi sitten molempiin naisiin, jotka seisoivat taempana, ja pysähtyi vihdoin herra Bloodiin, joka istui toinen jalka toisen polven yli heitettynä niin huolettoman näköisenä, ettei kukaan olisi voinut arvata, mitä hänen mielessään liikkui.

Sitten kapteeni astui komeron luo ja aukaisi toisen raskaan, tammisen ovipuoliskon. Hän tarttui kyyryssään istuvaa piileskelijää takin kauluksesta ja veti hänet päivänvaloon.

»Mikäs piru tämä sitten on?» kysyi hän. »Varmaankin toinen jalosukuinen otus?»

Herra Blood näki hengessään kapteeni Hobartin mainitsemat hirsipuut ja onnettoman nuoren merikapteenin koristamassa yhtä niistä ilman edelläkäypää oikeuden päätöstä sen uhrin sijasta, joka oli päässyt livistämään hänen käsistään. Hän keksi heti sekä arvonimen että koko sukuluettelon nuorelle kapinalliselle.

»Aivan niin, tepä sen sanoitte. Hän on kreivi Pitt, Thomas Versonin serkku, joka on naimisissa tuon hempukan, Moll Kirken, teidän oman everstinne sisaren kanssa, joka aikanaan oli Jaakko-kuninkaan puolison hovinaisena.»

Sekä kapteeni että hänen vankinsa hätkähtivät hämmästyksestä. Mutta kun nuori Pitt piti suunsa visusti kiinni, kirosi kapteeni oikein nasevasti. Hän tarkasti vankiaan uudelleen.

»Hän valehtelee, eikö niin?» kysyi hän tarttuen nuorta miestä olkapäihin ja tuijottaen häntä kasvoihin. »Jumaliste, hän tekee pilaa minusta.»

»Jos olette sitä mieltä, niin hirttäkää hänet ja odottakaa, mitä siitä teille seuraa.»

Rakuunaupseeri tuijotti ensin tohtoriin ja sitten taas vankiin. »Eikö mitä!» huudahti hän ja lennätti nuoren miehen sotamiestensä käsiin.

»Viekää hänet Bridgewateriin ja vangitkaa tuo mies myös», jatkoi hän osoittaen Baynesia. »Kyllä me näytämme hänelle, mitä kapinallisten majoittaminen ja hoitaminen tietää.»

Syntyi hetken hämminki. Baynes tappeli sotamiesten käsissä kuin vimmattu ja teki ankaraa vastarintaa. Kauhistuneet naiset huusivat, mutta vaikenivat pian vielä suuremman kauhun edessä. Kapteeni astui huoneen poikki heidän luokseen. Hän otti tyttöä hartioista. Tyttö, sievä kultakutrinen olento, katsoi kapteeniin säälittävän rukoilevasti. Kapteeni katsoi häneen himokkaasti, silmät kiiluvina, otti häntä leuasta ja suuteli häntä raa’asti, niin että tyttö värisi kauhusta.

»Minä tarkoitan totta», sanoi raakimus hymyillen julmasti. »Toivottavasti tämä rauhoittaa teitä siksi kunnes olen päässyt

selväksi noista roistoista.»

Ja hän kääntyi poispäin jättäen tytön puoleksi tainnoksissa ja vapisevana hätääntyneen äidin syliin. Hänen miehensä, jotka olivat sitoneet molemmat vangit, seisoivat odottaen käskyä ja virnistelivät.

»Viekää heidät pois, kornetti Drake ottakoon heidät huostaansa.»

Hänen kiiluvat silmänsä etsivät taas piilottelevaa tyttöä. »Jään tänne vähäksi aikaa», sanoi hän, »tutkiakseni tarkemmin tämän paikan.

Täällä saattaa olla vielä muitakin kapinallisia piiloutuneina.» Ja ikään kuin jälkimietteenä lisäsi hän: »Viekää tämä mies mukananne.» Hän osoitti herra Bloodia. »Mars!»

Herra Blood heräsi mietteistään. Hän oli tuuminut, että hänellä oli kojelaatikossaan pitkä leikkaus veitsi, jolla saattaisi suorittaa kapteeni Hobartiin nähden erittäin hyväätekevän leikkauksen. Hyväätekevän nimittäin ihmiskunnalle. Joka tapauksessa sairasti rakuuna liikaverevyyttä, joten pieni suoneniskentä olisi ollut hänelle sangen sopiva. Vaikeus oli vain tilaisuuden saannissa. Hän oli alkanut ajatella, eikö kapteenia olisi voinut saada viekoitelluksi hieman syrjään vaikkapa jonkin kätketyn aarteen tapaamisen toivossa, kun tämä liian aikainen keskeytys teki lopun hänen mieltäkiinnittävästä mietiskelystään.

Hän koetti voittaa aikaa.

»No, se sopii minulle erinomaisesti», sanoi hän, »sillä Bridgewateriin olen lähdössä, ja ellette te olisi minua viivyttänyt, niin olisin sinnepäin jo hyvässä matkassa.»

»Teidän määränpäänne siellä on vankila.»

»Eihän toki! Te laskette leikkiä!»

»Teidän varallenne on myös hirsipuu, jos pidätte sitä parempana. Kysymys on vain siitä, tapahtuuko se nyt heti vaiko hieman myöhemmin.»

Raa’at kädet tarttuivat herra Bloodiin, ja tuo arvokas leikkausveitsi oli laatikossa pöydällä, kaukana käden ulottuvilta. Hän riuhtaisi itsensä irti rakuunain käsistä, sillä hän oli voimakas ja rivakkaliikkeinen mies, mutta he ympäröivät hänet heti uudelleen ja veivät ulos. Painaen häntä maata vasten he sitoivat hänen kätensä selän taakse ja kiskaisivat vankinsa raakamaisesti taas jaloilleen.

»Viekää hänet pois», sanoi Hobart lyhyesti ja kääntyi antamaan määräyksiään toisille odottaville rakuunoille. »Menkää ja etsikää koko talo ullakolta kellariin saakka ja tulkaa sitten ilmoittamaan minulle tänne.»

Sotilaat menivät ovesta sisähuoneisiin. Herra Bloodin veivät hänen vartijansa miespihaan, jossa Pitt ja Baynes jo odottivat. Hallin kynnyksellä hän katsahti vielä kapteeni Hobartiin ja hänen tummat silmänsä salamoivat. Hänen huulillaan oli jo uhkaus siitä, mitä hän Hobartille aikoi tehdä, jos elävänä pääsisi tästä pälkähästä. Ajoissa hän kuitenkin havaitsi, että jos hän sen lausuisi, hän varmaan menettäisi viimeisenkin eloonjäämisen mahdollisuuden suorittaakseen tekonsa. Sillä tänä päivänä olivat kuninkaan miehet herroja Länsi-Englannissa ja sitä pidettiin vihollismaana, jonka oli nöyrästi alistuttava kaikkiin sodan aiheuttamiin kauhuihin voittajan puolelta. Täällä oli tällä hetkellä rakuunakapteeni elämän ja kuoleman valtiaana.

Puutarhan omenapuiden alla sitoivat rakuunat herra Bloodin ja hänen onnettomuustoverinsa kunkin eri hevosen jalustinhihnaan. Sitten lähti pieni joukko kornetin komentamana Bridgewateria kohti. Heidän lähtiessään sai herra Bloodin arvelu, että rakuunat pitivät seutua voitettuna vihollismaana, mitä kamalimman vahvistuksen. Talosta kuului hajoavien väliseinien rätinä, särjettyjen ja kumoon nakattujen huonekalujen räiske sekä sotamiesten raakoja huudahduksia ja naurua, jotka kaikki ilmaisivat, että kapinallisten etsiskely oli vain tekosyy, jonka varjolla he saivat mellastaa ja hävittää. Vihdoin kuului ylinnä kaiken äärimmäisessä tuskassa olevan naisen läpitunkeva avunhuuto.

Baynes pysähtyi ja kääntyi ympäri tuskissaan ja hänen kasvonsa muuttuivat tuhkanharmaiksi. Seurauksena hänen pysähtymisestään oli, että jalustimeen sidottu nuora veti hänet kumoon ja hän laahautui avuttomana jonkin matkaa ennen kuin rakuuna pysähdytti hevosensa ja karkeasti kiroten löi häntä miekan lappeella selkään.

Raahautuessaan tuona ihanana, tuoksuvana heinäkuun aamuna kypsyyttään nuokkuvien omenapuiden alla johtui herra Bloodin mieleen, että — kuten hän jo kauan oli epäillyt — ihminen oli inhottavin olento Luojan luomista ja että oli houkkamaista antautua sellaisten parantajaksi, jotka mieluummin olisi hävitettävä sukupuuttoon maan päältä.

Kolmas luku

YLITUOMARI

Vasta kaksi kuukautta myöhemmin, yhdeksäntenätoista päivänä syyskuuta — Peter Blood joutui oikeuteen valtiopetoksesta syytettynä. Tiedämme, että hän ei ollut syyllinen siihen. Mutta meidän ei tarvitse epäilläkään, ettei hän sen ajan kuluttua olisi ollut valmis siihen. Kaksi kuukautta epäinhimillistä, sanoinkuvaamatonta vankeutta oli kasvattanut hänen mieleensä kylmän ja kuolettavan vihan Jaakko-kuningasta ja hänen edustajiaan kohtaan. Se seikka, että hänellä niissä oloissa oli ensinkään järkeä jäljellä, on erinomainen todistus hänen sitkeydestään, ja vaikka tämän täysin viattoman miehen asema oli kauhea, oli hänellä siitä huolimatta aihetta kiitollisuuteen kahdestakin syystä. Ensimmäinen niistä oli se, että hän yleensä pääsi oikeuden eteen. Toinen taas oli siinä, että oikeudenistunto oli sinä päivänä eikä päivää aikaisemmin. Juuri tuossa viivytyksessä, joka häntä äärimmilleen katkeroitti, oli — vaikka hän ei sitä tiennyt — hänen ainoa mahdollisuutensa pelastua hirsipuusta.

Jollei onni olisi häntä erityisesti suosinut, olisi hän taisteluaamuna sangen helposti joutunut hirtettyjen joukkoon, yhtenä niistä sadoista, jotka verenhimoinen eversti Kirke toi torille Bridgewaterin täpötäydestä vankilasta aivan summamutikassa hirteen vedettäviksi. Tangerin rykmentin everstillä oli kiire ja hän olisi varmaankin menetellyt samalla tavalla kaikkiin lukuisiin vankeihin nähden, jollei tarmokas piispa Mews olisi joutunut väliin ja tehnyt loppua hänen mielivaltaisesta kenttäoikeudestaan.

Sittenkin onnistui Kirken ja Fevershamin saada hengiltä satoja ihmisiä niin summittaisten tuomioiden perusteella, ettei niitä sillä nimellä voi mainitakaan. He tarvitsivat ihmispainoja niihin vipuihin, joita he olivat pystyttäneet pitkin maaseutua tuhkatiheään, ja he välittivät vähät siitä, millä keinoilla he niitä saivat ja kuinka viattomia

heidän uhrinsa olivat. Mitäpä heidän mielestään moukan elämä merkitsi? Pyövelit käyttelivät köyttä, kirvestä ja kuumia kattiloita. Mutta minä säästän lukijani mieltäjärkyttävistä yksityisseikoista. Olemmehan lopultakin tekemisissä vain Peter Bloodin kohtalon kanssa emmekä Monmouthin kapinallisten.

Hän jäi elämään joutuakseen siihen surulliseen vankikarjaan, joka parittain kytkettynä marssitettiin Bridgewaterista Tauntoniin. Ne, jotka olivat liian vaikeasti haavoittuneita kyetäkseen kävelemään, sullottiin raaisti ajoneuvoihin, joissa he sitomattomine ja märkivine haavoilleen saivat virua. Moni sai onnen kuolla matkalla. Kun Blood vaati ammattinsa perusteella oikeutta koettaa huojentaa heidän vaivojaan, pidettiin häntä hävyttömänä ja uhattiin raipoilla. Jos hän nyt katui jotakin, niin oli se sitä, ettei hän ollut lähtenyt Monmouthin mukaan. Se oli tietenkin epäjohdonmukaista, mutta hänen asemassaan olevalta mieheltä voinee tuskin enää odottaa johdonmukaisuutta.

Hänen kahletoverinaan tuolla hirvittävällä matkalla oli sama

Jeremias Pitt, joka alun perin oli hänen nykyisen onnettoman tilansa aiheuttanut. Nuori merikapteeni oli jäänyt hänen läheiseksi kumppanikseen yhteisesti kärsityn vankilassaolon aikana. Siitä ehkä johtui, että heidät oli kahlehdittu yhteen täyteen ahdetussa vankilassa, jossa he alituiseen olivat olleet vaarassa tukehtua löyhkään ja kuumuuteen heinä-, elo- ja syyskuun kuluessa.

Ulkomaailmasta tunkeutui silloin tällöin tietoja vankilaan. Muutamat olivat ehkä tahallisesti sinne levitettyjä. Sellainen oli muun muassa juttu Monmouthin mestauksesta. Se synnytti syvää surua niissä onnettomissa, jotka parhaillaan kärsivät herttuan vuoksi, varsinkin kun hän oli luvannut puolustaa heidän uskontoaan. Moni kieltäytyi uskomasta sitä. Alkoipa hurja huhu kertoella, että joku

Monmouthia muistuttava mies olisi uhrautunut herttuan puolesta mestattavaksi ja että Monmouth eli ja tulisi kohta kunniassaan ja vapauttaisi Siionin ja julistaisi uuden sodan Babylonia vastaan.

Herra Blood kuunteli juttua yhtä välinpitämättömänä kuin hän oli ottanut vastaan uutisen Monmouthin kuolemastakin. Mutta yhden asian hän tämän yhteydessä kuuli, joka ei jättänyt häntä niinkään välinpitämättömäksi vaan joka yhä lisäsi sitä halveksuntaa, jota hän jo tunsi Jaakko-kuningasta kohtaan. Hänen majesteettinsa oli suvainnut ottaa Monmouthin puheilleen. Sellainen teko, ellei hänellä ollut tarkoitus armahtaa herttuaa, oli uskomattoman halpamainen ja katala. Sillä puheille pääsyn syynä ei voinut olla muu kuin alhainen tyydytys saadessaan nauttia onnettoman veljenpoikansa nöyrästä katumuksesta.

Myöhemmin he kuulivat, että lordi Grey, joka herttuan jälkeen — niin, ehkäpä ennenkin häntä — oli ollut kapinan pääjohtajana, oli ostanut itsensä rangaistuksesta vapaaksi neljänkymmenentuhannen punnan hinnalla. Peter Blood arveli, että se oli kaiken muun komennon mukaista. Hänen halveksuntansa kuohahti vihdoin yli laitain.

»Valtaistuimellahan istuu täydellisen kurja roisto. Jos olisin aikaisemmin tiennyt hänestä yhtä paljon kuin nyt tiedän, niin en luule, että olisin antanut aihetta nykyiseen olotilaani.» Ja sitten hänen mieleensä juolahti äkkiä eräs ajatus. »Ja missä luulette lordi Gildoyn nyt olevan?» kysyi hän.

Nuori Pitt, jota hän oli puhutellut, käänsi kasvonsa tohtoriin. Hänen merielämän parkitsema ihonsa oli menettänyt miltei kokonaan punakkuutensa pitkällisen vankeuden aikana. Hänen silmänsä olivat pyöreinä kysymysmerkkeinä. Blood vastasi itse kysymykseensä.

»Emmehän ole nähneet hänen ylhäisyyttään sitten Oglethorpen päivien, ja missä ovat muut vangitut jalosukuiset herra — varsinaiset kapinan johtajat? Luulen, että Greyn juttu selittää täydelleen heidän poissaolonsa. He ovat varakkaita ihmisiä ja voivat ostaa, itsensä vapaiksi. Täällä odottavat hirsipuuta vain ne onnettomat, jotka liittyivät heihin, kun taas ne, joilla oli kunnia johtaa heitä, kulkevat vapaina. Se on soma ja opettava esimerkki asiain nurinkurisuudesta.

Totisesti elämme epävakaisessa maailmassa.»

Hän nauroi, ja sama pilkallinen hymy huulillaan astui hän sitten Tauntonin linnan suureen saliin tuomioistuimen eteen kuulusteltavaksi.

Hänen kanssaan astuivat Pitt ja Baynes, maanviljelijä. Heidät piti tutkittaman kolmisin ja heidän asiansa aloitti tuon synkän päivän.

Sali, joka parvekkeita myöten oli täynnä uteliaita katsojia — enimmäkseen naisia — oli verhottu punaiseen. Se oli yli tuomarin miellyttävä päähänpisto, joka varsin luontevasti ilmaisi, mikä väri hänen verenhimoista mieltään parhaiten viihdytti.

Salin toisessa päässä varta vasten tehdyllä korokkeella istuivat neuvoskunnan muodostavat viisi tuomaria punaisissa viitoissa ja mustissa suurissa tekotukissaan ja ylinnä heidän keskellään ylituomari, lordi Jeffreys, Wernin herra.

Vangit marssivat sisään vartijainsa saattamina. Oikeudenpalvelija vaati hiljaisuutta vankeusrangaistuksen uhalla, ja kun puheensorina vähitellen oli vaiennut, katseli herra Blood kiinnostuneena jurya, jonka muodosti kaksitoista paikkakuntalaista isäntämiestä Eivät he juuri miehiltä näyttäneet. He olivat yhtä säikähtyneitä, levottomia ja masentuneita kuin varas, joka on tavattu pistämästä kättään lähimmäisensä taskuun. Juryn muodosti kaksitoista pelotettua

miestä, jotka äskettäin olivat saaneet vapauttavan tuomion mutta jotka yhä olivat täydelleen herra ylituomarin mielivallan armoilla. Heistä vaelsi herra Bloodin rauhallinen katse tuomareihin ja varsinkin ylituomarina istuvaan lordi Jeffreysiin, jonka hirvittävä maine oli kulkeutunut hänen edellään Dorchesteristä.

Lordi Jeffreys oli pitkä, hoikka, neljänkymmenen korvissa oleva mies, jolla oli erinomaisen kauniit soikeahkot kasvot. Hänen pitkäripsisten silmiensä ympärillä oli kärsimysten tai unettomuuden aiheuttamia tummia täpliä, jotka korostivat niiden loistetta ja hiljaista surumielisyyttä. Hänen kasvonsa olivat hyvin kalpeat, paitsi täyteläisiä huulia, joilla väreili eloisa puna, sekä jonkin verran korkeita, joskaan ei varsin esiinpistäviä poskipäitä, joilla helotti kuumeinen hehku. Hänen huulissaan oli jotakin, joka häiritsi hänen kasvojensa täydellisyyttä, jotakin pahaa, tuskin tuntuvaa, mikä kuitenkin oli havaittavissa ja oli omituisessa ristiriidassa hänen hienon nenänsä, tummien, kosteitten silmiensä ja kalpean otsansa ylvään rauhallisuuden kanssa.

Lääkäri herra Bloodissa katseli miestä erityisen kiinnostuneena, sillä hän tunsi sen kalvavan taudin, joka hänen ylhäisyyttään vaivasi, ja hän tiesi myös kuinka hämmästyttävän epäsäännöllistä ja juopottelevaa elämää tämä vietti siitä huolimatta — tai ehkäpä juuri sen vuoksi.

»Peter Blood, nostakaa kätenne!»

Yleisen syyttäjän karkea ääni herätti hänet äkkiä todellisuuteen. Hän noudatti käskyä koneellisesti ja syyttäjä luki yksitoikkoisella äänellä syytekirjelmän, jossa sanottiin, että Peter Blood oli tehnyt itsensä syypääksi kaikkein armollisimman ja korkeimman ruhtinaan Jaakko Toisen, Jumalan armosta Englannin, Skotlannin ja Irlannin

kuninkaan, hänen luonnollisen ja ylimmän herransa, kavaltamiseen.

Siinä julistettiin vielä, että samainen Peter Blood, pelkäämättä Jumalaa, oli antanut perkeleen vietellä itsensä unohtamaan sanotulle herralle ja kuninkaalle tulevan rakkautensa, uskollisuutensa ja luonnollisen kuuliaisuutensa ja että hän, Peter Blood, oli ryhtynyt häiritsemään kuningaskunnan rauhaa ja levollisuutta nostattamalla kapinaa ja sotaa anastaakseen sanotun herransa ja kuninkaansa arvon, kunnian ja hänen korkean kruununsa kuninkaallisen nimen — ja paljon muuta samanlaista, jonka loputtua häntä kehoitettiin sanomaan tunnustiko hän syyllisyytensä vai ei.

Hän vastasi useammalla sanalla kuin mitä häntä oli kehoitettu käyttämään.

»Olen täydelleen viaton.»

Pieni, terävänaamainen mies, joka istui pöydän ääressä vasemmalla, ponnahti pystyyn. Hän oli herra Pollexfen, ylisyyttäjä.

»Oletteko syyllinen vaiko syytön?» kivahti ärtyisä herrasmies.

»Teidän tulee käyttää niitä sanoja.»

»Vai niitä sanoja?» sanoi Peter Blood. »Noo — syytön.» Ja sitten hän jatkoi kääntyen tuomareitten puoleen. »Jos suvaitsette, arvoisat herrat, niin en ole syyllinen ainoaankaan niistä asioista, joista äsken kuulin itseäni syytettävän. Korkeintaan voidaan viakseni lukea kärsimättömyys, jota olen tuntenut ollessani kaksi kuukautta suljettuna inhottavaan vankilaan, jossa sekä terveyteni että elämäni olivat vaarassa.»

Päästyään alkuun aikoi hän puhua enemmänkin, mutta tällä kohdalla keskeytti hänet herra ylituomari lempeällä, miltei valittavalla äänellä.

»Nähkääs, sir, minun täytyy keskeyttää teidät nyt, koska meidän on seurattava yleistä ja yhteistä menettelytapaa oikeudenistunnossa. Te ette varmaankaan tunne lain muotoja?»

»En tiedä niistä mitään, mutta olen tähän saakka elänyt peräti onnellisena tässä tietämättömyydessäni. Varsin mielelläni olisin jättänyt tämänkin tuttavuuden niiden kanssa tekemättä.»

Heikko hymy välähti ylituomarin tarkkaavaisilla kasvoilla.

»Uskon teitä. Teitä tullaan tarkasti kuulemaan, kunhan teidän puolustautumistilaisuutenne tulee. Mutta kaikki, mitä te nyt sanotte, on tavasta poikkeavaa ja sopimatonta.»

Ilmeisen myötämielisyyden ja arvonannon rohkaisemana vastasi herra Blood tämän jälkeen sitä mukaa kuin häneltä kysyttiin tahtovansa tulla Jumalan ja isänmaansa tutkittavaksi. Kun sitten sihteeri oli rukoillut Jumalaa ja jättänyt hänen asiansa Hänen hyvään huomaansa, kutsui hän esiin Andrew Baynesin ja kehoitti häntä nostamaan kätensä ja vastaamaan. Baynesista, joka myös vastasi kieltävästi, hän siirtyi Pittiin. Tämä myönsi rohkeasti syyllisyytensä. Herra ylituomari liikahti paikallaan.

»Kas niin, se kuulostaa paremmalta», hän virkkoi ja hänen neljä punaviittaista virkaveljeään nyökkäsivät. »Jos kaikki olisivat yhtä itsepäisiä kuin hänen molemmat kapinatoverinsa, niin tästä ei tulisi loppua koskaan.»

Tämän pahaaennustavan välihuudahduksen jälkeen, joka

lausuttiin niin epäinhimillisen jäätävästi, että koko oikeussalin läpi kävi puistatus, nousi herra Pollexfen seisomaan.

Erinomaisella pitkäveteisyydellä hän totesi, mistä noita kolmea miestä yleensä syytettiin ja erityisesti herra Bloodia, jonka asian piti ensimmäisenä tulla esille.

Ainoa todistaja, joka kuninkaan puolesta oli haastettu todistamaan, oli kapteeni Hobart. Hän kertoi reippaasti, missä olosuhteissa hän oli tavannut syytetyt ja miten hän oli heidät vanginnut yhdessä lordi Gildoyn kanssa. Everstinsä määräysten mukaan hän olisi hirttänyt Pittin heti, mutta vangittu Blood oli valheellaan saattanut hänet siihen uskoon, että sanottu Pitt oli valtakunnan päärejä ja siis henkilö, johon oli suhtauduttava varovaisesti.

Kapteeni Hobartin lopetettua todistuksensa kääntyi lordi Jeffreys

Peter Bloodin puoleen.

»Onko syytetty Bloodilla mitään muistuttamista todistajan lausuntoa vastaan?»

»Ei mitään, mylord. Hänen puheensa pitää täsmälleen paikkansa.»

»Olen iloinen siitä, että myönnätte asian ilman verukkeita, jotka ovat niin tavallisia teikäläisille. Ja voin sanoa, että tässä ette verukkeilla mihinkään pääsisi. Sillä me olemme aina lopulta oikeassa, olkaa varma siitä.»

Baynes ja Pitt myönsivät myös kapteenin todistuksen yhtäpitäväksi totuuden kanssa, minkä jälkeen punaviittainen herra ylituomari huokasi syvään helpotuksesta.

»Koska asia siis on selvä, niin käykäämme eteenpäin Jumalan nimeen. Sillä meillä on vielä paljon työtä.» Hänen äänessään ei nyt ollut rippeitäkään ystävällisyydestä. Se oli tiukka ja särähtelevä ja huulet, joiden välistä se soi, olivat pilkallisessa hymyssä.

»Arvelen, herra Pollexfen, että koska heidän syyllisyytensä valtiopetokseen on tullut toteennäytetyksi — hehän ovat sen itsekin myöntäneet — niin ei tässä asiassa ole muuta sanomista.»

Silloin kajahti Peter Bloodin ääni kirkkaana ja siinä soi merkillinen naurun tuntu.

»Suvainnette, teidän ylhäisyytenne, mutta mielestäni siinä on vielä koko joukon sanomista.»

Hänen ylhäisyytensä katsoi Bloodia ensin hämmästyneenä hänen rohkeudestaan, mutta vähitellen hänen katseensa muuttui synkän vihaiseksi. Hänen punaiset huulensa vääntyivät epämiellyttäviin, julmiin poimuihin, jotka muuttivat koko hänen kasvonsa toisenlaisiksi.

»Mitä, mitä roistomaisuutta tämä on? Aiotteko tuhlata meidän kallista aikaamme joutaviin jaarituksiin?»

»Tahtoisin, että teidän ylhäisyytenne ja herrat juryn jäsenet kuulisivat puolustukseni, kuten teidän ylhäisyytenne taannoin lupasi tehdä.»

»Vai niin, roisto, kyllä saat vielä, sen lupaan.» Hänen ylhäisyytensä ääni oli repivä kuin viila. Hän väänteli itseään

puhuessaan ja hänen kasvonsa olivat tuskan ilmeissä. Hieno kuolemankalpea käsi, jonka verisuonet kuulsivat sinisinä, veti esille nenäliinan, jolla hän pyyhkäisi ensin huuliaan ja sitten otsaansa. Tarkastaen häntä lääkärin silmillä Peter Blood päätteli, että hän oli saanut sen taudinkohtauksen, joka häntä kalvoi.

»Kyllä saat, mutta koska kerran olette tunnustanut, niin mitä siinä enää on puolustelemisesta apua.»

»Saatte päättää sitten, mylord.»

»Sitä varten istun tässä.»

»Ja niin saatte tekin, hyvät herrat.» Blood kääntyi tuomareista juryn puoleen. Viimeksimainittu liikahti levottomana hänen varman katseensa edessä. Lordi Jeffreysin uhkaava syytös oli pusertanut heistä kaiken miehuuden. He olivat itse olleet syytettyinä maanpetoksesta ja olivat yhä herra ylituomarin mielivallan alaisia.

Peter Blood astui askelen eteenpäin rohkeana, suorana, itsekylläisenä ja pilkallisena. Hän oli vasta ajeltu ja hänen tekotukkansa, vaikka se olikin kähertämätön, oli huolellisesti kammattu ja siistitty.

»Kapteeni Hobart on todistanut sen, mitä hän tiesi asiassa, että hän tapasi minut Oglethorpen talossa Westonin taistelun aamuna. Mutta hän ei ole kertonut, mitä minä tein siellä.»

Taas keskeytti ylituomari hänet. »Mitäpä te siellä olisitte tehnyt kapinallisten parissa, joista jo kaksi — lordi Gildoy ja toverinne tuossa — ovat tunnustaneet syyllisyytensä!»