Priscilla Papers

Power Equations

03 Hierarchy and the Biblical Worldview

Alan Myatt

8 Women and Men: A Biblical and Theological Perspective

Ian Payne

14 Victim Blaming and the David and Bathsheba Narrative

J. Dwayne Howell

18 The Image of God as a Statement of Mutuality: An Illustration

Aaron K. Husband

23 Humility: The Path for MaleFemale Relationships

John McKinley

29 Book Review

The Struggle to Stay: Why Single Evangelical Women Are Leaving the Church

Reviewed by Emma Feyas

Editorial

A certain fable tells of a wicked lion that took over a forest. He hunted not just for food but because it amused him to kill. The terrified animals hastily convened a meeting and came to a decision. They would persuade the lion to accept an animal as his meal each day, sent to his den. The lion agreed. Each day, his meal arrived as promised. One day, the meal failed to arrive at the usual time. The lion waited, getting hungrier and angrier by the hour. At last, a rabbit appeared, running as if her life depended on it. “Great lion,” she panted on arrival, “six rabbits were sent as your meal today, but we were waylaid by a lion bigger and fiercer than you. Only I have escaped to come to you.”

The lion was furious. Another lion? Did he have a rival? The rabbit offered to show him, and brought him to a deep well on the edge of the forest. “The other lion lives in this well—look and see!” said the rabbit. The lion looked into the still water of the well below him and saw, of course, his own reflection. Without another thought, he let out an angry roar and leaped into the well. And that was the end of him.

In the fallen state of humanity, men and women often relate to each other as the lion did with his reflection: with suspicion, with animosity, with the desire to supersede. A relationship that was to be governed by mutuality is fraught with rivalry. The patriarchal social structures that continue to dominate our homes, churches, and workplace communities are the hotbed in which the abuse of power flourishes.

Alan Myatt persuasively presents how hierarchical thinking in Christian theology, especially as it endorses the superiority of the male over the female, reflects the Greek philosophical

concept of the Great Chain of Being, which locates all that exists into vertical positions of power relative to each other. Dwayne Howell illustrates through the story of David and Bathsheba how social power structures result in exploitation and questions the reading of Bathsheba—influenced by hierarchy—that seeks to blame the victim and absolve the perpetrator.

Moving from what is to what should be , Ian Payne and Aaron Husband examine what it means for men and women to be created in the image of God. Payne teases out the threads that constitute the equality of women and men, both at creation and in the reality of the new creation that Christ brings us into. Husband explains, using the analogy of a female-male pair appointed as co-directors of a Christian event, how the complementarian hierarchical position is incompatible with the concept of humanity—male and female—as bearers of the divine image.

A final contribution to what should be is John McKinley’s essay, which proposes that Christlike humility as it was practiced by the NT church is the means by which abusive male-female power relations can be deconstructed.

We look towards a world in which lions are wiser than in the fable: creatures that recognize the likeness between God and themselves (irrespective of sex) and honour it in each other, resisting the fallenness of hierarchical power relations.

Praying that this issue of Priscilla Papers inspires us to serve together, side by side, in God’s world.

Havilah Dharamraj EditorPriscilla Papers is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database® (ATLA RDB®), http://www.atla.com, in the Christian Periodical Index (CPI), in New Testament Abstracts (NTA), and in Religious and Theological Abstracts (R&TA), as well as by CBE itself. Priscilla Papers is licensed with EBSCO’s full-text informational library products. Full-text collections of Priscilla Papers are available through EBSCO Host’s Religion and Philosophy Collection, Galaxie Software’s Theological Journals collection, and Logos Bible Software. Priscilla Papers can also be found on Academia, Faithlife, and JSTOR. Priscilla Papers is a member publication of the American Association of Publishers.

Advertising in Priscilla Papers does not imply organizational endorsement. Please note that neither CBE International, nor the editor, nor the editorial team is responsible or legally liable for any content or any statements made by any author, but the legal responsibility is solely that author’s once an article appears in Priscilla Papers

CBE grants permission for any original article (not a reprint) to be photocopied for local use provided no more than 1,000 copies are made, they are distributed for free, the author is acknowledged, and CBE is recognized as the source.

Priscilla Papers is the academic voice of CBE International, providing peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary scholarship on topics related to a biblical view of women and men in the home, church, and world.

Editor: Havilah Dharamraj

Assistant to the Editor: Jeff Miller

Graphic Designer: Margaret Lawrence

President / Publisher: Mimi Haddad

Peer Review Team: Andrew Bartlett, Joshua Barron, Stephanie Black, Lynn H. Cohick, Seblewengel (Seble) Daniel, Mary Evans, Laura J. Hunt, Chongpongmeren (Meren) Jamir, Jung-Sook Lee, Jill McGilvray, Ian Payne, Finny Philip, Charles Pitts, Terran Williams

On the Cover: Double expourse; Shutterstock Stock Photo ID: 2307366793

Priscilla Papers (issn 0898–753x) is published quarterly by CBE International, 122 W Franklin Avenue, Suite 610, Minneapolis, MN 55404–2426 | cbeinternational.org | 612–872–6898

© CBE International, 2023.

DISCLAIMER: Final selection of all material published by CBE International in Priscilla Papers is entirely up to the discretion of the publisher, editor, and peer reviewers. Please note that each author is solely legally responsible for the content and the accuracy of facts, citations, references, and quotations rendered and properly attributed in the article appearing under her or his name. Neither CBE, nor the editor, nor the editorial team is responsible or legally liable for any content or any statements made by any author, but the legal responsibility is solely that author’s once an article appears in print in Priscilla Papers

Hierarchy and the Biblical Worldview

Alan MyattAfter decades of discussion, the evangelical debate over the roles of women and men in church and at home shows no sign of resolution. Both sides affirm the final authority of Scripture but arrive at very different conclusions. It is as if each side is looking at the Bible through a different set of lenses. Here I will examine the interpretive lens that leads to a male-female hierarchical reading of biblical texts. I aim to show how theological patriarchy can be said to ground female subordination in a view of the creation order that bears relation to ancient Greek philosophy, and, as such, is incompatible with the biblical doctrine of creation. Therefore, the hierarchical structure of family and church supported by complementarianism replicates an unbiblical worldview that distorts God’s intention for church, home, and society.1

The Greek Roots of Hierarchy in the West

The ancient Greeks observed that the world is composed of a wide diversity of individual things grouped together into larger categories. What makes aspen, elm, or pine trees all trees when they are individually distinct? Greek philosopher Plato (428/423–348/347 BC) reasoned that there must be a universal principle, such as “treeness,” that unifies all particular trees. These principles are abstract ideas that represent the “true essence” of individual things. Hence, the idea of a thing is its most perfect reality, not the individual tree growing in your front yard. Plato traced each category to a higher and more abstract level of unity until he concluded that ultimate reality itself is the pure idea of perfection, absolute goodness, or the One. In this we can see the suggestion that ideas and the particular things that represent them may be organized into a hierarchy stretching from the perfection of the abstract One down to the imperfect world of the Many.

Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle (384–322 BC), also had an incipient notion of hierarchy in his discussion of the relation between the various species of animals as well as the relationships among human beings. He argued that it is just and proper for some people to be slaves, because nature has made particular persons to be ruled and others to be rulers. He wrote, “The male is by nature superior, and the female inferior; and the one rules, and the other is ruled; this principle, of necessity, extends to all mankind.”2 For Aristotle, maleness is fullness; it is knowledge; it is that which is rational, active, and commands. The female nature represents deprivation, opinion, the emotional, the passive, and is created to obey.3

The seeds of hierarchy planted by Plato and Aristotle eventually came into full bloom in Plato’s most famous interpreters in antiquity, Plotinus (AD 204/5–270) and Proclus (AD 412–485). Plotinus, in the Enneads , 4 and Proclus, in his Elements of Theology , 5 each developed the hierarchy of Being 6 into complete cosmologies that unified all creation. This became known as the Great Chain of Being.

Plotinus taught that the original reality was the One, an absolute state of perfection and unity with no distinctions. Out of this absolute state of unity, diversity descends in a series of emanations. Like the rays of the sun, the emanations shine downward as a magnificent chain. They unite all things on a scale of existence down to the lowest specks of dust. The first emanation from the One is Mind. From Mind follows Soul. Soul, in turn, produces matter and unites with it to form living creatures, the highest of which is humankind. The rest are arranged in descending order of rationality, followed by the plant world and, finally, non-living matter. Even the stones are arranged in a hierarchy, since gold is more noble than lead, which is in turn higher than mere dirt. Everything has its due place in the hierarchy of the created order.7

Though hierarchicalism had gained inroads into the church through such figures as Gregory of Nyssa,8 Augustine,9 and others, Proclus sought in Plotinus a means of combatting the growing marginalization of pagan Greek religion by Christianity. He understood the hierarchical cosmology of Plotinus to be incompatible with the worldview of Christianity and wanted to use it against Christian teaching. He was, no doubt, correct in this assessment, but that did not prevent the Neo-Platonic metaphysics of hierarchy from being gradually adopted by Christian theology, especially in the Greek-speaking east.

Proclus’s Elements of Theology was transmitted to the Latin West by a translation from Arabic of an Islamic adaptation titled The Book of Causes, 10 and through the highly influential works of Dionysius the Areopagite. The latter was dubbed Pseudo-Dionysius, as he was clearly not the disciple of Paul from Acts 17 whose name he adopted. Pseudo-Dionysius created a syncretism of Neo-Platonic and Christian concepts, forging a hierarchical cosmology that became the framework for subsequent theological and philosophical speculation.

In Pseudo-Dionysius, the One becomes fully identified with the God of Christianity. Written between AD 485 and 528, his books The Celestial Hierarchy and The Ecclesial Hierarchy described the Great Chain of Being in elaborate detail.11 In the spiritual realm, the Chain stretches from God through a hierarchy of angels arranged in three triads. First are the Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones, who are above the Dominations, Virtues, and Powers, ranking above the Principalities, Archangels, and Angels. Spirit meets matter in humanity, which in turn rules over the hierarchy of animals, plants, and inanimate things. In each of these classes, every individual has a designated place in the hierarchy, subordinate to those above it and superior to those below. Any attempt to step outside one’s divinely appointed place in the hierarchy upsets the very order of creation.

The Victory of Hierarchy in Medieval Theology

Among the many medieval thinkers probably influenced by Pseudo-Dionysius, Thomas Aquinas (ca. 1225–1274) was the

most influential. Although Aquinas is well known for his use of Aristotle, contemporary scholars note that it was Neo-Platonic Aristotelianism that he inherited.12 Indeed, his teacher, Albert the Great (AD 1196–1280), is notable for his synthesis of Neo-Platonism with the philosophy of Aristotle.13 Aquinas gained his knowledge of Plato through sources including Augustine, The Book of Causes, Dionysius, and Proclus, in which hierarchy was fully developed.

Thus, it is no surprise to discover that Aquinas viewed the structure of creation as a hierarchy of Being.14 Etienne Gilson commented, “It is easy to see the influence of Pseudo-Dionysius on the mind of St. Thomas.” Dionysius, says Gilson, “leaves the conviction that it is impossible not to consider the universe as a hierarchy; but he leaves the task of filling this hierarchy to St. Thomas. . . .”15 For Aquinas, each individual on the ladder of Being was inferior in its participation in the qualities of the thing on the next level above. To be lower on the hierarchy was to be inferior in Being and further from God.16 The hierarchy of Being extends from God through numerous ranks of angels, humans in various social positions, and the lower animals. While the hierarchy is, in a sense, a ladder to God, it is proper for each creature to remain in its assigned place in the created order.17

By the time of Aquinas, the Neo-Platonic idea of hierarchy was well along the path of being completely embedded in the structure of medieval Christendom, both in the church and in the social structure of the feudal kingdoms that arose after the breakup of the Roman Empire. The idea of the Great Chain of Being provided an all-encompassing worldview to justify and sustain this social reality.

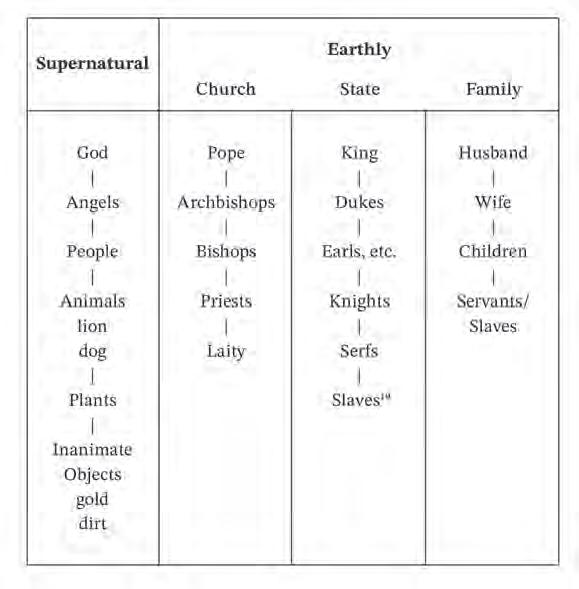

The Hierarchical Scheme of Medieval Feudal Society 18

The Great Chain of Being

It is impossible to read classic literature in Western history without seeing references to the philosophy of the Great Chain of Being. E. M. W. Tillyard discusses the concept in detail in The Elizabethan

World Picture, a book designed to give students of Shakespeare the background needed to understand his works. He observes:

The chain stretched from the foot of God’s throne to the meanest of inanimate objects. Every speck of creation was a link in the chain, and every link except those at the two extremities was simultaneously bigger and smaller than another: there could be no gap.20

As a typical example, Tillyard quotes an influential work from the 1400s on natural law:

In this order angel is set over angel, rank upon rank in the kingdom of heaven; man is set over man, beast over beast, bird over bird, and fish over fish, on the earth, in the air, and in the sea: so that there is no worm that crawls upon the ground, no bird that flies on high, no fish that swims in the depths, which the chain of this order does not bind in most harmonious concord.21

Each individual thing in the Chain of Being, no matter how lowly, has a function necessary for the well-being of the whole. Things run smoothly when each link stays in its proper place, fulfilling its divinely mandated function. In this way, although things higher on the chain have greater degrees of nobility and a higher participation in Soul or the spiritual, all things have equal value and dignity. They are each equally necessary to maintain the proper balance and function of creation, and the failure of any link in the chain to do the work proper to its nature upsets the order of creation with disastrous results.22

In Milton’s Paradise Lost, the catastrophe of rebelling against one’s place on the Chain of Being comes into full view. First, Lucifer attempts to break the Chain by overthrowing God and taking his place. Later, the authority structure of God over man, man over woman, mankind over the animals is ruptured when Eve attempts to ascend to the level of God, ironically by submitting to the direction of the serpent. She eats the forbidden fruit and gives it to her husband. He acquiesces to her leadership by accepting it. Through this sequence of ruptures in the Chain of Being, evil with all its woes enters the creation.23

Evangelicals and the Chain of Being

Arthur Lovejoy showed in his classic study, The Great Chain of Being, that by the time of the Protestant Reformation, the idea of hierarchy so permeated European culture that it was simply taken for granted.24 It never occurred to the Reformers to question it. Hierarchy was practically the air they breathed.

In this setting, John Calvin (1509–1564) wrote that Paul forbids a woman to teach because she “by nature (that is, by the ordinary law of God) is formed to obey.” He uses the language of the Chain of Being to assert that women “must keep within their own rank,” clearly below the rank of men.25 He situates women firmly within the Chain of Being. Man is preeminent over woman, who is “inferior in rank,” since she was created for man. This echoes how Neo-Platonism describes the emanation of lower elements from the higher. Woman must be inferior and subject to man because she “derives her origin from the man” and the thing produced must always be subject to the thing that causes it.26

This is not to say that Calvin was consciously applying PseudoDionysius in his exegesis. It is simply to recognize that the idea of the Chain of Being was so completely pervasive that everything, including Scripture, was viewed through its lens. While they succeeded in rejecting the authority of the Roman Catholic hierarchy, Calvin and the other reformers did not question the hierarchies of the political and social order. Women remained firmly in their place below men on the Great Chain of Being.

The Chain of Being’s influence over evangelicals continued down through the centuries as evidenced by their use of it to justify the brutal enslavement of Africans. This extended into early AngloAmerica and was used against the abolitionists' egalitarian readings of Scripture.27 Historian Winthrop Jordon notes that belief in the Chain of Being was pervasive in America during the 1700s.28 It was a convenient tool for classifying Africans below Europeans, just above the apes, though not without creating tension in the minds of Christians, who could not avoid seeing that Africans are humans, not animals. Evangelical slaveholders resolved this tension by affirming both the spiritual equality of Africans and their functional subordination to whites.29 The parallels between this and the complementarian insistence that women and men are equal in value while women are functionally subordinate is no mere coincidence.

Contemporary evangelicals no longer defend slavery, but the Great Chain of Being persists in its influence, particularly in contemporary defenses of male authority over women. Perhaps there is no clearer statement than that of Elisabeth Elliot, who grounded male authority over women in what she viewed as

a glorious hierarchical order of graduated splendor, beginning with the Trinity, descending through seraphim, cherubim, archangels, angels, men, and all lesser creatures, a mighty universal dance, choreographed for the perfection and fulfillment of each participant.30

The inclusion of this in one of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood’s principal collections of essays would appear to be endorsement. The remaining question is to determine if this is truly biblical.

The Great Chain of Being and the Bible

The idea of the Great Chain of Being is not unique to the West. It is so common in world history that anthropologist Louis Dumont dubbed humanity Homo Hierarchicus 31 To discover if the Bible teaches that the Chain of Being accurately describes the creation order, we will compare the biblical creation account with the worldview of ancient Egypt.

Ancient Egyptians saw the original Being as “the Primordial Abyss of waters (which) was everywhere, stretching endlessly in all directions. . . . all was dark and formless.”32 The waters, called Nu or Nun, are “the basic matter of the universe” from which consciousness came into being.33 “This Nun, however, was not so much a primary substance or form of matter, but rather a mythic symbol of the abstract reality of the full potential of being.”34

Before the beginning of creation, there was only an infinite dark, watery, chaotic sea. There was nothing above or below the sea— the sea was all there was. Immersed in the sea, Atum (or Re or Amun or Ptah), the creator god and source of everything, brought himself into existence by separating himself from the waters.35 The gods evolved from this impersonal, original One, manifesting as a descending hierarchy of beings, and creating a hierarchy of the various classes of humans.36

Recent scholarship has argued that the long-observed similarities between Genesis 1 and Egyptian mythology are not simply borrowed ideas, as earlier critical scholarship assumed. Instead, it recognizes that the biblical creation account serves as a polemic against ancient Egyptian cosmology.37 This polemic is apparent in that Genesis 1 opens by flipping the Egyptian creation account on its head. Egyptian mythology declares impersonal, chaotic Being to be ultimate, with consciousness and the gods arising from it and subject to it. In contrast, Genesis reveals that the infinite, personal, self-contained God came first. Divinity did not rise from the primordial waters as in the Egyptian view, but rather God spoke the primordial waters into existence from nothing. The idea of a hierarchical Chain of Being linking nature to God is decisively ruptured by Genesis 1:1.

The worship of heavenly bodies was a significant part of ancient Egyptian religion, since it identified the sun, moon, stars, and planets with the hierarchy of gods. As elements of the hierarchy of Being superior to humankind, they had power over human destiny, provoking fear. The writer of Genesis, however, shows no such fear. He reveals that the sun, moon, and stars did not emanate from uncreated Being as the Egyptian astrologers believed. They were created as distinct entities for the purpose of serving the needs of humankind. Hence, they have no power over us.

The Hebrew account of the creation, function, and limitation of the luminaries is another unequivocal indicator that in Genesis 1 there is a direct and conscious anti-myth polemic. The form in which this Hebrew creation account has come down to us portrays the creatureliness and the limitations of the heavenly luminaries as is consonant with the worldview of Genesis 1 and its understanding of reality.38 Genesis 1 inverts the order in which the luminaries were created in Egyptian mythology, breaking the hierarchy of divine Being implied therein.39

Likewise, the creation of animals and plants does not depict the fashioning of a hierarchy linked by degrees of participation in the Being of the One. Instead, God creates each group distinctly after its own kind. There is discontinuity between each of the kinds. Each reproduces within the limits of the kinds in which they were created. The text does not indicate that they are linked on a scale of existence. Not only is there no link between kinds, but the creation of the simpler forms of life first reverses the order of emanation of the animals from the One in ancient mythology.

The first hint of hierarchy in the biblical creation story does not appear until God gives humanity the mandate for dominion over the creation (Gen 1:26–30). Here, the hierarchy is God over humans (male and female) and humans—male and female alike—over the rest of creation. Unlike the Chain of Being, there is no continuity of Being linking these three categories. God is distinct in his Being from

humans, just as humans, who bear the divine image, are distinct from the rest of the creation. Likewise, there are no hierarchies indicated within the three categories of the divine, the human, and the rest of creation. The divine Being is personal and One, not a hierarchy of finite gods as in Egyptian polytheism. Humans are created both male and female, with no hint of priority or authority given to one gender or the other. Both are equal recipients of the command to have dominion over the earth (Gen 1:28).

It is worth noting what the text of Genesis 1 does not say. While silence is not proof, when an obvious opening exists for making a claim critical to an argument, we may assume that its absence is not simply an oversight. We would expect the notion of a hierarchy of Being to be introduced here if it were relevant, yet we see nothing of the kind. This is significant because wherever it appears, the Great Chain of Being is the central, unifying motif that provides structure, coherence, and order to a worldview. If creation were truly structured in a hierarchy of Being, then Genesis 1 would be the most obvious place to say so. Instead we see just the opposite: namely, the consistent disruption of hierarchies.

Many have argued that there is a hierarchy between male and female humans in the text of Genesis 2. But why, after ruling out hierarchies in nature, would the writer suddenly revert to hierarchical thinking in the next chapter? That makes no sense. Nevertheless, we need to comment briefly on common arguments in favor of such a hierarchy.

Complementarians have argued that the creation of the man first and the woman second indicates a hierarchical relationship requiring female submission to male authority.40 The man was created first, they say, and for this reason enjoys priority as the leader over the woman. However, we have seen that the order in which the animals were created does not support hierarchy. If it did, then, by the same logic the animals should have authority over humans. What we do find in the OT are examples of first-born children being given less priority than their younger siblings.41Apparently, chronological order is not necessarily relevant for establishing authority in the Bible.

Complementarians have also reasoned that since the woman was created to be the man’s helper in Genesis 2, she must function as an assistant under his direction and supervision.42 The problem here is that the Hebrew word for helper, ezer, does not have the same connotation as the English word “helper.” The Hebrew word is used principally to describe a superior party who comes to the rescue of someone in need. In other passages, the word is used to refer to God when he acts as the “helper.” If anything, taking ezer literally would invert the traditional male-female hierarchy. At the very least it erases hierarchy as an option in Genesis 2.43 Rather than being an assistant, the woman was created as “‘a strength/power equivalent to him,’ equally able to carry out the creation mandate assigned to humanity.”44

Thus, we see that the biblical account of creation is a rebuttal to the hierarchical worldview. A hierarchical Chain of Being is simply incompatible with the creation order as established by God in which man and woman share dominion equally. Against this background, female subordination first enters the world as a result of the fall (Gen

3:16). Male-female hierarchy appears here for the first time, not as the God-ordained order of creation, but as a devastating aspect of sin. It turns the creation order upside down, wrecking the proper mutual relationship between man and woman. Ever since the fall, hierarchicalism has been a distorted lens that the fallen mind uses to view the world. It eradicates the Creator-creature distinction by placing God at the top of a hierarchy of Being merging with the created realm, thus giving license to the rebellious human quest to ascend to godhood. It alienates humankind from creation, making its dominion one of environmental exploitation and destruction, rather than stewardship and godly development. It creates power hierarchies of race, caste, class, and gender that issue forth in oppression and abuse.

Conclusion

In light of the incompatibility of the Great Chain of Being with a biblical worldview, I conclude that hierarchy is not a viable rubric for interpretating Scripture. A consistently biblical hermeneutic must be a worldview hermeneutic. Difficult and disputed texts such as 1 Cor 11:2–16, 1 Tim 2:11–15, and Eph 5:21–33 simply cannot mean something that contradicts the most basic presuppositions of the biblical worldview as established from Genesis to Revelation. On the contrary, a correct interpretation of these texts will support and reinforce the biblical worldview. Since the Bible takes a hierarchical interpretation of creation off the table in its opening chapters, it cannot be what the inspired writers of Scripture intended for us to understand.

Our study shows that, rather than being derived from the Bible, hierarchicalism is the fruit of a non-Christian worldview reflecting pagan Greek philosophy. Over time, it entered the church and became a distorted lens for reading the Bible in such a way as to mandate the practice of female subordination, contrary to its egalitarian intent. Reading the Bible without the influence of unbiblical, Neo-Platonic presuppositions frees us to see that the disputed passages actually subvert hierarchies in human relationships and point us back to the egalitarianism of the original creation order. May we take this to heart and banish human-made hierarchies from disturbing the order and freedom of all members of the body of Christ.

Notes

This article is an enlarged version of the presentation “The Worldview of the Bible vs. the Worldview of Hierarchy,” delivered at the CBE conference in São Paulo, Brazil, 2023.

1. My thesis here is not original; I am building and expanding upon two previous articles: Letha Scanzoni, “The Great Chain of Being and the Chain of Command,” The Reformed Journal 26/8 (Oct 1976) 14–16; Robert K. McGregor Wright, “Hierarchicalism Unbiblical,” Journal of Biblical Equality 3 (June 1991) 57–66.

2. Aristotle, “Politics” 1.1, in Aristotle: The Complete Works (Pandora’s Box) Kindle Location 820.

3. Prudence Allen, The Concept of Woman: The Aristotelian Revolution 750 B.C.–A.D. 1250, 2nd ed. (Eerdmans, 1997) ch. 2.

4. Plotinus, The Enneads, ed. Llyod P. Gerson (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

5. Proclus, The Elements of Theology: A Revised Text with Translation, Introduction, and Commentary, 2nd ed., ed. E. R. Dodds (Clarendon, 1992).

6. I am using “Being” with a capital B to represent the Greek concept of existence itself. It embraces all that is, including God and the universe. It is synonymous with ultimate reality. Applied to God, I use the capital B to denote God as ultimate Being, distinct from the creation, which is “being” with a lowercase b.

7. cf. Dominic J. O’Meara, “The Hierarchical Ordering of Reality in Plotinus,” in The Cambridge Companion to Plotinus, ed. Lloyd P. Gerson (Cambridge University Press, 1996); D. E. Çuscombe, “Hierarchy,” in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Philosophy, ed. A. S. McGrade (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

8. Dmitry Birjukov, “Hierarchies of Beings in the Patristic Thought: Gregory of Nyssa and Dionysius the Areopagite,” in The Ways of Byzantine Philosophy, ed. Mikonja Knežević (Sebastian, 2015) 71–88.

9. Lia Formigari, “Chain of Being,” in Dictionary of the History of Ideas, ed. Philip P. Weiner (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1973) 1:326.

10. Book of Causes: Liber de causis, English and Latin Edition, trans. Dennis J. Brand (Marquette University Press, 1984).

11. Both may be found in Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, The Works of Dionysius the Areopagite, trans. John Parker, vol. 2 (James Parker and Co., 1899).

12. Wayne J. Hankey, “Aquinas, Plato, and Neoplatonism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Aquinas, ed. Brian Davies and Eleonore Stump (Oxford University Press, 2012) 56.

13. Markus Führer, “Albert the Great,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta (Summer 2022), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/ albert-great/.

14. I use a capital B here because, even though Aquinas affirmed the Creator-creature distinction, his use of the Greek notion of Being in general obscured it.

15. Etienne Gilson, The Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas (B. Herder Book Co., 1924) 274–75.

16. Gilson, Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 196.

17. Gilson, Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, 154–57, 272.

18. Table adapted from Bruce R. Magee, “The Three Estates and Their Potential Vices,” in Course Notes for English 201 (Louisiana State University, 2008), https://latech.edu/~bmagee/201/intro2_ medieval/estates&chain_of_being_notes.htm.

19. On medieval slavery, see The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500–AD 1420, new ed., ed. C. Perry, D. Eltis, S. L. Engerman, and D. Richardson (Cambridge University Press, 2021). Burnard, in his review, remarks, “Slavery was unproblematic because it fitted well into hierarchical assumptions, especially in regard to understandings of the place of women and children in society.” Trevor Burnard, “A Global History of Slavery in the Medieval Millennium,” in Slavery & Abolition 43/4 (2022), 819–26, https://web.archive.org/ web/20210422143616/http:/www2.latech.edu/~bmagee/201/ intro2_medieval/estates&chain_of_being_notes.htm

20. E. M. W. Tillyard, The Elizabethan World Picture (Taylor and Francis) Kindle Location 26.

21. Sir John Fortescue, Works, ed. Lord Clermont (London, 1869) 1:322, cited in Tillyard, Elizabethan World Picture, 27.

22. Tillyard, Elizabethan World Picture, 93–94.

23. John Milton, Paradise Lost, in English Minor Poems; Paradise Lost; Samson Agonistes; Areopagitica, ed. Mortimer J. Adler and Philip W. Goetz, 2nd ed., vol. 29, Great Books of the Western World (Encyclopædia Britannica; Robert P. Gwinn, 1990) Books IX and X; Bruce R. Magee, “Milton,” Course Notes for English 201 (Louisiana State University, 2008), https://latech. edu/~bmagee/201/milton/paradise_notes.htm.

24. Arthur O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea (Harvard University Press, 1976).

25. John Calvin. Commentary on 1 Timothy, 2:12.

26. John Calvin. Commentary on 1 Corinthians, 11:8.

27. Scanzoni, “Great Chain of Being,” 16.

28. Winthrop D. Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550–1812 (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North

Carolina Press, 2012) 483.

29. Winthrop D. Jordan, The White Man’s Burden: Historical Origins of Racism in the United State, Kindle Locations 1153–82.

30. Elisabeth Elliot, “The Essence of Femininity: A Personal Perspective,” in Recovering Biblical Manhood & Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, ed. John Piper and Wayne Grudem (Crossway, 2006) 394. Numerous writers in this collection of essays ground subordination in the nature of femininity, consistent with Chain of Being thinking. Further evidence of Chain of Being influence on complementarians may be found in the essays of McGregor Wright and Scanzoni.

31. Louis Dumont, Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications, 2nd ed. (University of Chicago Press, 1981).

32. R. T. Rundle Clark, Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt (Thames and Hudson, 1991) 35.

33. Rundle Clark, Myth and Symbol, 36.

34. Vincent Arieh Tobin, Theological Principles of Egyptian Religion (Peter Lang, 1989) 60.

35. Johnny V. Miller and John M. Soden, In the Beginning . . . We Misunderstood: Interpreting Genesis 1 in Its Original Context (Kregel, 2012) 78.

36. Robert A. Armour, Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt (American University in Cairo Press, 1986) 18, 20; Janice Kamrin, The Cosmos of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan (Kegan Paul International, 1999) 7.

37. Brian N. Peterson, “Egyptian Influence on the Creation Language in Genesis 2,” BibSac 174/695 (2017) 289–90; John D. Currid, Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old Testament (Crossway, 2013) 36ff.; Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, chs. 1–17, NICOT (Eerdmans, 1990).

38. Gerhard F. Hasel, “The Polemical Nature of the Genesis Cosmology,” EvQ XLVI/2 (April–June 1974) 89.

39. Hamilton, Book of Genesis, 128.

40. See, for example, Bruce A. Ware, “Male and Female Complementarity and the Image of God,” in Biblical Foundations for Manhood and Womanhood, ed. Wayne Grudem, Foundations for the Family Series (Crossway, 2002) 82.

41. Mary L. Conway, “Gender in Creation and Fall: Genesis 1–3,” in Discovering Biblical Equality: Biblical, Theological, Cultural, & Practical Perspectives, ed. Ronald W. Pierce, Cynthia Long Westfall, and Christa L. McKirland, 3rd ed. (IVP Academic, 2021) 42.

42. Raymond C. Ortlund Jr., “Male-Female Equality and Male Headship: Genesis 1–3,” in Recovering Biblical Manhood & Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, 101–2.

43. “As to the source of the help, this word is generally used to designate divine aid, particularly in Psalms (Cf. Ps 121:1, 2) where it includes both material and spiritual assistance.” Carl Schultz, “1598 עָזַר,” TWOT 661.

44. Conway, “Gender in Creation and Fall,” 42.

Alan Myatt, Ph.D. is a graduate of Denver Seminary with a PhD in Theological Studies and Religion from Denver/Iliff School of Theology. He is currently a professor of Theology at the Baptist College of Curitiba, Brazil. He taught at Baptist Theological College of São Paulo, Brazil and was chair of Theology and Philosophy of Religion at South Brazil Baptist Theological Seminary. His publications include Teologia Sistemática (awarded two Arete prizes) and numerous articles such as “Fides Reformata,” “Religion and Social Policy,” and “Vida Acadêmica” and his article titled “On the Compatibility of Ontological Equality, Hierarchy and Functional Distinctions” pages 22–28, in the special edition publication titled “The Deception of Eve and the Ontology of Women,” published by CBE. He also contributed to CBE’s “An Evangelical Statement on the Trinity.”

Women and Men: A Biblical and Theological Perspective

Ian Payne“My first memory was from when I was three years old,” he said to me. “I’m clinging to my mother’s sari as my father is strangling my mother!” It helped me understand a little more his struggle to stop beating his wife.

Is a woman a person?

Are men entitled to treat women as subordinate, as possessions?

Relationships between men and women can be heaven. They can be hell. How easily men learn they can dominate women! They learn to think they must keep them in line. They learn to treat women as subordinates, as possessions.

“Is a woman a person?” This is the title of Sudhir Kakar’s article, written not long after the nation-shocking rape in a Delhi bus of a young woman dubbed by the media as Nirbhaya.1 Kakar, an Indian psychoanalyst, explores the tension between Western and traditional views of women. Is a woman a person? The answer, it seems, is yes—so long as she is a mother, daughter, sister, or wife. If not, the answer is no. She is just an object, an object for the enjoyment of men, an object for the playhouses of their minds.

The article makes a great discussion point in my theology classes. Is a woman a person? Are men entitled to treat women as subordinate, as possessions? There is plenty of ill-treatment of women in the Bible. Does the Bible permit, even promote, this? Though God’s word comes through patriarchal settings, does it reinforce that patriarchy—or not? By looking at God’s purposes for men and women in creation and in new creation, focusing especially on 1 Corinthians 11:7 and Galatians 3:28, we will find the Bible certainly speaks today. The Bible presents a vision of equality and giftedness.

Men and Women in Creation Equally Created

Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.”

So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. (Gen 1:26–27 NRSV)

Right from the first chapter, God’s purposes for humanity focus on men and women. Their being made in his image distinguishes them from animals. We are told God “created humankind in his own image,” and immediately come the words “male and female he created them.” Traditionally, this has been seen merely as preparing the way for the

topic of reproduction in the next verse. But is that all? Is it significant that there is mention of the sexual difference straightaway (unlike the animals)? When we ask what this sexual differentiation means for understanding the image of God, 2 we unfold a richer meaning. The poetic parallelism is synonymous; the author intends us to see the second line further explains the first line. That means sexual difference is part of the image of God and hence that men and women are equally made in the image of God.

We should be careful not to derive too much significance from this one verse, but it already points us away from seeing the imago Dei3 as primarily structural and, instead, as something that is also social. It is not some substance within us; rather, it is how we behave in community. When we attend to the larger biblical context surrounding Genesis 2:18, together with Ephesians 5:22–33, we see where the Bible is going with the sexual differentiation between men and women. In the former passage, we see God’s paradigm for all marriages; in the latter, all marriages point ultimately to the marriage—of Christ and the church. Marriage is linked, in the end, with the marriage supper of the Lamb. The image of God theme points us to the destiny of the new humanity in Christ.4

How does sexual differentiation relate to the story of God’s ultimate purposes for humanity? Gender works to transform us by drawing us out of ourselves. Felipe do Vale sees gender as love. “Through loving,” he says, “we bring the beloved into ourselves and incorporate them into our stories. . . . [but because] love has its source and end in God, who is love . . . [the] social goods that we are called to love are to be loved as gifts from the Creator, according to the specifications set forth by the Giver, and in a right order. . . . The forces that shape us into godliness are the same forces that tell us who we are as gendered selves.”5 Using a different metaphor, Jonathan Grant says, “Our onesidedness as either male or female creates a homing instinct that calls us beyond ourselves, to seek relationship with God and others.”6

Men and women feature centrally throughout the human story. We must now consider how they introduce the dramatic tension. Adam and Eve fall into sin.

Equally Fallen

It starts so well. God says, “It is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a corresponding partner for him (Gen 2:18).” But in the Garden, Adam and Eve disobey God. Equally created, they are now equally fallen.

Much has been made of Paul’s observation that “Adam was not the one deceived; it was Eve who was deceived and became a sinner”

(1 Tim 2:14 NIV). This follows Paul’s statement that he does not permit a woman to teach or assume authority over a man. Does Paul believe men are less prone to deception than women? Does this lead us to conclude only men should have leadership positions in the church? Cynthia Westfall gives good reasons why to do so would be to misunderstand Paul. Her wider study of what Paul says about temptation leads her to assert, “Even though Eve was a woman, according to Paul, the possibility of being tempted or deceived by Satan or sin is a universal experience. Eve’s deception is a paradigmatic example of the human condition.”7 Furthermore, after showing that “Christian women in Ephesus were being deceived in a way that was unparalleled in other churches,” she argues it is plausible to understand Paul’s prohibition in v. 12 to be based on Eve’s deception and transgression as an illustration of the deception of women and men in Ephesus. That is, the situation (perhaps some gullible women) in Ephesus, rather than an ontological flaw in all women, justitifies the ban on their teaching.8 Yes, some women are more prone to deception than some men, and this suited Paul’s point in 1 Timothy in that particular situation. But elsewhere, referring to the same Genesis event, Paul lays the blame on Adam. Paul teaches that sin entered the world through Adam (Rom 5:12–21, focusing on his humanity rather than his maleness). No, being prone to deception is not a universal principle for all women in all places. All humans can be deceived. We are equally fallen.

Equally Dignified in Cultural Cross-currents

Equal dignity has been rare. There is no doubt most cultures in history provide cross-currents for seeing women as equal in status with men. The culture in Paul’s day is no exception. What we know about women and attitudes toward them in the ancient world paints an awful picture. In Judaism, women were not counted in the quorum needed for a synagogue. Jewish men used to daily thank God that God had not made him “a Gentile, a slave, or a woman.”9 In Greco-Roman culture, things were worse.10 One ancient writer said women were the worst plague Zeus made. Ontologically, perfection, strength, and rationality were found in men; imperfection, weakness, and irrationality in women. Women, though useful, were sometimes considered mere chattels, without intelligence, without legal status. Extramarital sex was often seen as acceptable for a husband but as shameful for a wife. Infanticide and abandonment of female babies was widespread, more so than of males. By and large, women were viewed as inferior. “Disdain for women was almost universal.”11

How does Paul address this? Does Paul say women and men are equally bearers of God’s image? Or does he think men are privileged and women are subservient? Many think subservience is the basis of what Paul is arguing in 1 Cor 11:2–16.

In those verses, he is discussing the propriety of covering the head when the Corinthian Christians gather for worship. In v. 7, the reason he gives that a man ought not cover his head is: “since he is the image and glory of God, but woman is the glory of man.” Paul is thinking of the Genesis creation narrative, for he continues in v. 8, “For man did not come from woman, but woman from man; neither was man created for woman, but woman for man” (NIV). So in light of this passage, the question is whether women and men bear the

image of God in different ways. Are women subordinate to men? Or are they equally made in the image of God?

This is a rather famous crux. Many interpreters say women are subordinate by creation;12 others equal by creation.13 Part of the problem lies in the influence that culture has on our understanding and reading of Paul. What do we think of that ancient culture’s endorsement of the general subservience of women? How does our own culture think about the symbolism of head and of head coverings—whether hats, veils, or hair? The most persuasive reading of 1 Cor 11:7 is that women and men are equal by creation but inhabit cultural cross-currents.

Paul says that when the house church gathered for worship, men were to have their heads uncovered and women were to have their head covered. Why? It is common to assume that the women were flouting the convention of wearing a veil in the house church and Paul is correcting them. The opposite scenario makes a plausible and compelling reading: the women want to wear the veil, and Paul is correcting the men!14

What does the head covering mean? In my (Western) culture, the headcovering of a judge or a police officer signals authority, but a veil signals subservience or subordinate status. The meaning of veiling in Corinth (and many non-Western cultures today) was to signal modesty and to avoid signalling sexual availability. Veiling was typically restricted to the upper classes. In these verses, then, Paul is defending the women’s right to resist pressure to remove their veils. “Paul’s support of all women veiling equalized the social relationships in the community. . . . [It] secured respect, honor, and sexual purity for women in the church who were denied that status in the culture.”15 This view also makes sense of v. 10: “. . . a woman ought to have authority over her own head.” There is no need to understand this as a figure of speech which upturns the meaning of the grammar (as if they must wear a veil as a sign of [accepting the man’s] authority on their heads).

We have not yet talked about a key word found in v. 7: head. The same word is prominent in v. 3: “the head of every man is Christ, and the head of the woman is man, and the head of Christ is God” (NIV). Compared with the English “head,” the Greek word translated “head” (kephalē) has a range of metaphorical meanings including “source of life.” “Source of life” makes good sense in this context. So v. 3 could be paraphrased, “But I want you to realize that every man’s life comes from Christ, woman’s life comes from man, and Christ’s life comes from God.” Paul’s words are not intended to convey hierarchy (and therefore patriarchy).16 Paul’s description balances the equality and the created distinction between man and woman, just as he later balances the priority of man’s creation (v. 8) with the interdependence of man and woman (vv. 11f.).

So what does v. 7 mean? “For a man should not have his head covered, since he is the image and glory of God. But the woman is the glory of the man.” Paul is urging that “man shows his humility before God as the unadorned image of God, and woman shows honor to God, herself, and her family by diminishing her glory/beauty in public and in worship. . . . The fact that woman was created for man’s sake (1 Cor 11:9) indicates the purpose of her greater beauty and her attraction for men.”17 Paul is not diminishing women’s attributes

but “sees them in a positive light: a woman’s hair is the glory of her head. Her hair is something valuable that needs to be protected and managed appropriately.”18 “Woman is the glory of man . . . describes the power women have over men.”19 So, v. 7 indicates that women are both made in the image of God and are the glory of man. This makes better sense than presuming women bear God’s image in a different and reduced way compared with men.

Notice Paul does not minimize the created distinction between man and woman. “Woman is the glory of man” highlights the distinctiveness of women. Since all are born of woman, men cannot exist without women. They fit; they are well suited for one another. We see this fit also in Genesis 2. For Adam, the animals do not fit, but the woman does. Adam rejoices in the identity-in-distinction, exclaiming she is “bone of my bone, flesh of my flesh.” God-given sexual difference impels people generally to come together in marriage and in community. Paul’s treatment of veiling shows women and men appropriately expressing their gender differences in culturally specific ways that vary from culture to culture.

We have been looking at women and men in the light of creation. “In the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” Women and men are equally bearers of the image of God. They possess distinctive attributes necessarily expressed in diverse cultural situations. From among the various ways of expressing gender available in our contexts, we should choose those that express their equal dignity. Each culture tends to warp the equality or blur the diverse glories that woman and man each have. Keeping the focus right depends on not only looking backward to creation but also looking forward to the new creation.

Women and Men in the New Creation

If, in creation, God has made women and men equal (though distinctive) image bearers, how does God continue doing so in the new creation work in Christ? The NT sees a necessary continuity between creation and redemption. God’s purposes in eschatology provide confirming proof of his purposes in creation. The destiny of women and men reflects the purpose of God’s creation of humanity. More than this, Jesus is pivotal. “Human destiny—the full flowering of the image of God—has already been realized in Jesus's resurrection.”20 In other words, because of Jesus, God’s new creation shines even more light on his purposes for women and men.

Not only are they equally made in the image of God, but women and men are also equally called to be in the image of God. This is true both in terms of ultimate destiny and our everyday character and service.

Equal Destiny

In Galatians 3, Paul describes the pivotal role of Christ in the unfolding purposes of God. Until Christ came we were “under the law”; now we are “in Christ” (Gal 3:23–26). Grace supercedes law. It is not that, with the coming of the New Covenant, the law has disappeared and we can now do whatever we like. Rather the law has been put “in our minds and written in our hearts.”21 Because Christ has fulfilled the law, stunningly, his obedience is counted as ours. The law was our guardian, making sure we knew God was

our Judge (v. 24). Now by faith we are free as children of God, our Father (v. 26). Like a sonic boom, Christ’s coming means God’s sure goal has broken into the world. He has begun to change and perfect everything. In language Paul uses elsewhere, “So if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation” (2 Cor 5:17 NRSV). “The renewal of the individual in conversion prefigures the renewal of the cosmos at the end.”24

As Paul makes explicit in Galatians 3, our point is this: women and men share equally in this new reality, this eschatological hope.

So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise. (Gal 3:26–29 NIV)

Men and women have the same eschatological hope without distinction. We share an equal destiny. Read it again: “. . . Nor is there male and female.” Along with the distinctions of race and rank, in God’s new creation the distinction of sex becomes irrelevant. Paul is emphatically asserting the equality of the sexes. Of course, he does not mean these distinctions are actually obliterated. We do not ignore people’s sex, treating someone as if they were actually the opposite sex or somehow neuter. John Stott clarifies, “When we say that Christ has abolished these distinctions, we mean not that they do not exist, but that they do not matter. They are still there, but they no longer create any barriers to fellowship.”23

“Paul fully and explicitly includes women and men in humanity’s final destiny. In Galatians 3:26–4:1, this destiny will be one of rule and authority, as God’s children and equal heirs in Christ.”24 Women and men will equally rule with Christ. Furthermore, in Christ, we anticipate the same resurrection body as Christ’s, regardless of gender.25

The problem is, however, that barriers for women in the church have often remained. Paul’s logic has been traditionally resisted. One would think their equal created dignity and their equal share in destiny would lead the church to encourage all to achieve their Godgiven potential in skills and leadership, regardless of their sex. The actual loss of a share in authority and rule for women is the result of the fall in Genesis 3:16. It is part of a general corruption of power in human relationships, which sin has brought about. There is no justification for mistreating or subordinating women.

Some have suggested the fact that Adam was created first requires a hierarchy, with men over women. But to qualify what he means about Adam’s priority and to exclude hierarchy, Paul asserts a balancing interdependence (1 Cor 11:11). Of the people of God, only Jesus has a superior status; only he is the firstborn 26

It has been persuasive for me to reflect on the maleness of Jesus. Does the incarnation mean men are more God-like than women? Are men more closely related to Christ than women are and therefore more truly human? The simple answer is no.27 One reason is that men and women are equally “brought into union with Christ through the power of the Spirit so that we come to take on the very

characteristics of Christ.”28 The fact that Christ was a man does not somehow privilege all males.

We have asserted women and men equally image God and alike will share a resurrection body like Christ’s. That we all may “take on the very characteristics of Christ” leads us to consider our equal calling.

We have asserted women and men equally image God and alike will share a resurrection body like Christ’s. That we all may “take on the very characteristics of Christ” leads us to consider our equal calling.

Equal Calling

Equally made in God’s image, we are equally called to bear his image. The same Spirit at work bringing us to our destiny is at work forming the Christian’s character and service in daily life. Being in Christ means becoming increasingly like Christ. Indeed, this is the central characteristic of salvation; becoming like him is the fruit of our union with Christ. Our point is this: women and men alike are called to become like Christ. The Bible calls all people to be holy and Christlike. There is no hint that men can become more holy than women.

Christlikeness is spiritual and ethical. While our life is always embodied, Christlikeness is never pictured in relation to body shape or eye colour—or gender. Being like Jesus does not mean wearing sandals or becoming carpenters or remaining unmarried29—or becoming masculine.

None of our bodies look like Jesus's; that is not the goal. But we will all become like him in character, for as John writes, “Dear friends, now we are children of God, and what we will be has not yet been made known. But we know that when Christ appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is. All who have this hope in him purify themselves, just as he is pure” (1 John 3:2–3 NIV). “Love, joy, peace . . . ” The fruit of the Spirit is the picture of Christlikeness in both women and men. Women and men are equally called to purity and self-sacrifice, to authentic transformation and service. 30

Consonant with all this, God equally enables women and men to serve him. Protestants routinely say we believe in the priesthood of all believers—and rightly so. This is fundamental to Paul’s famous call to worship and service in the body of Christ in Romans 12:1–8. We are all urged to offer our bodies as living sacrifices. In vv. 3–5, we are called to diverse service in unity. God has given each of us spiritual gifts to benefit the body of Christ, the church. Notice that Paul urges us to evaluate what our personal gift is according to “faith” (v. 3) and to “grace given to each of us” (v. 6). It is problematic when men claim that a woman's faith and experience are invalid in discerning her gift. In vv. 6–8, Paul teaches that gifts are given to meet the needs of the body of Christ. The list of seven gifts Paul gives is representative rather than exhaustive, but he covers a wide range: prophecy, serving, teaching, exhortation, giving, leadership (which links with elders and deacons), and mercy. It

is significant that God gives spiritual gifts to women as well as to men. Paul sees no need in Romans 12 to teach that half of what he is saying does not apply to half of his audience! The truth is that spiritual gifts are given by God without restriction as to sex.

How sad it is when Christian men reserve for themselves the gifts of leadership and teaching, and restrict women’s participation.31 Exclusive male leadership is in the long run toxic and unjust. Ultimately, it reflects a different theology for women than for men.

What is needed is recognition that God equally calls women and men to serve him in the church and in mission—where unjust crosscurrents will certainly be encountered even more. To please the Lord, Christian women and men need to be Christlike and adaptable.

Equally Self-Sacrificial in Cultural Cross-Currents

In the Pastoral Epistles, Paul teaches how the young churches where Timothy and Titus serve should live as a community and among unbelievers. Similarly, in passages often called household codes, Ephesians 5:22–6:9 and Colossians 3:18–4:1 offer advice directed to wives, husbands, children, parents, slaves, and masters. We can learn from the way he gives different advice to each group. Slaves are taught to obey; masters to be just. Wives to submit; husbands to love. In Ephesians 5:22, 25 we read, “Wives, submit yourselves to your own husbands as you do to the Lord. . . . Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for . . . ” (NIV).

What does Paul mean? The word submit means “be courteously respectful,” yielding one’s own rights. It is a grateful acceptance of love, not grovelling obedience. In 1 Cor 11:3, Paul sees a creational model of headship meaning “source.” Here he adds a model of the headship of Christ in relation to the church. The church willingly submits to Christ. Submission and headship are powder keg words. That is because of their connection with power.

Headship is not hierarchy. Some men exercise control and make all the decisions, either openly or secretly. That is simply tyranny. It is as if he remotely controls an electric dog collar on his wife’s neck. Headship conceived as control leads to power games. One seeks to dominate, either by open demand, by physical violence, by playing the victim, or even by threatening suicide.

Rather, headship is self-sacrificial love. In between tyranny and rivalry are marriages in which husband and wife display something more mysterious. Headship is reverent responsibility. The head is the source of the provision of life in a relationship of equals. But this is a priority of love not of power. Paul could have echoed Jesus’s teaching about servant leadership. It is not about “lording it over others.” Marriage is like a dance, where mutual submission (v. 21) is how we dance, respecting our distinctives (vv. 22–33). A wife’s submission is self-sacrificial; a husband’s headship is also self-sacrificial, and this is exactly what Paul emphasises as expected of husbands.

Back then, the most strikingly countercultural line in these marriage instructions is Paul’s command to husbands, and that is why he dwells on it four times as long!32 Most interpreters see that the effect of Paul’s teaching is to soften the hard edges of the hierarchical social structures in the ancient world. The question

is whether Paul agrees with them and is urging believers to conform or whether he disagrees with them and aims to subvert In the new creation, God is now actively reversing the fall, equally bringing women as well as men toward the completion of their same destiny. Paul’s “in Christ” vision has missional and therefore also sociological implications. What is true “in Christ” needs to become a practical reality insofar as mission priorities allow.33 Paul is arguing, in other words, “for the entire church to adopt a missional and self-sacrificial adaptation to fallen social structures of the Greco-Roman world as a strategy to advance the gospel. . . . Like secret agents, Paul wanted his communities to fit in as much as possible; they did the same things that their neighbours did yet for eschatological reasons: they served another king and belonged to another kingdom.”34

So, when Paul enjoins submission of women to their husbands in keeping with the Greco-Roman setting and upends that culture by requiring self-sacrificial love of men to their wives, his motive is not conformity, but subversion. Each sacrifices their right to selfdetermination. It is the Saviour, the head, who determines. Each is impelled to generous service to the other. To people in our context wondering if submission to God’s lordship reduces their humanity, Christian communities and marriages can demonstrate submission to God’s authority that is liberating. Indeed, as something penultimate, marriage points to the ultimate mystery of Christ and the church, in which our calling to self-sacrificial love finds its final purpose.

In the new creation, God is now actively reversing the fall, equally bringing women as well as men toward the completion of their same destiny.

Conclusion

Whether we are looking back to creation or forward to the new creation, the Bible teaches us that men and women have equal dignity and destiny. In God’s purposes, by grace and faith, sexual difference draws us out of ourselves into community and to his ultimate goal of eternal fellowship with him.

God has three purposes for gender. They are transformative, missional, and unitive. That is, God’s purpose is to foster in us love, like his, that transforms us as individuals, incorporates us in community, and unites us in fellowship with himself. Here are some lessons.

First, God wants us to become morally like him. Since he regards women and men as equally made in his image, we should respect them equally. Created equal in dignity, women and men live in interdependence. Societies that celebrate women and men as equal image-bearers flourish. Their created equality means women are never possessions of men, not even of husbands. Disability or gender deficit35 does not disqualify people from that equal status. Furthermore, women and men are equally called to become image bearers. In Christ, there is no male and female. Women and men share an equal destiny: we are all to be holy. Holiness is not somehow easier for men, as if they were

more truly human. Women and men are equally given gifts to serve the community and the church. So we should encourage all to achieve their God-given potential in skills and leadership, regardless of their sex. Women and men are called to share dominion.

Second, God wants us to be fruitful. When we face cultural crosscurrents to God’s purposes, mission informs how we adapt to culture. From among the various ways of expressing gender available in our context, we should choose those that express the equal dignity of women and men and the counterintuitive power of mutual submission. Whether our context favours tyranny or rivalry, Christian women and men should live out their equal dignity through self-sacrificial love. We share in God’s mission of drawing all people together under the headship of Christ, in whom we find true freedom in submission. We must be willing to upend our culture’s gender stereotypes and rampant consumerism for the sake of the gospel.

Third, God wants us for fellowship with himself. God aims to teach us to love him. To lose ourselves for the sake of another, against all insecurities and self-centredness, is Christlike. At the marriage supper of the Lamb, there will only be women and men whose love for Christ has eclipsed their love for themselves.

Notes

This article is an edited version of a chapter in Ian Payne’s forthcoming book, The Message of Humanity, in The Bible Speaks Today series (IVP, 2025).

1. Times of India (Jan 9, 2013).

2. Latin for “the image of God.”

3. See Stanley Grenz, The Social God and the Relational Self: A Trinitarian Theology of the Imago Dei (Westminster John Knox, 2001) 270ff.

4. Filipe do Vale, Gender as Love: A Theological Account of Human Identity, Embodied Desire, and our Social Worlds (Baker Academic, 2023) 238.

5. Jonathan Grant, Divine Sex: A Compelling Vision for Christian Relationships in a Hypersexualized Age (Brazos, 2015) 146.

6. Gen 2:18. The Hebrew word for “helper” (ezer) does not connote subordination, for in its usage the most common reference is to God.

7. Cynthia Long Westfall, Paul and Gender: Reclaiming the Apostle’s Vision for Men and Women in Christ (Baker Academic, 2016) 111. Note that, in 2 Cor 11:3, Paul fears that the Corinthian church (not just the women there) might be led astray.

8. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 117f.

9. William Barclay, The Letters to the Galatians and Ephesians, Daily Study Bible, rev. ed. (Theological Publications in India, 1976, 1991) 168.

10. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 14ff.

11. John R. W. Stott, The Message of Ephesians (IVP, 1979) 224. See further, Lynn H. Cohick, Women in the World of the Earliest Christians: Illuminating Ancient Ways of Life (Baker Academic, 2009).

12. E.g., D. J. A. Clines, “Image of God,” in Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, ed. Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid (IVP, 1993) 426ff.

13. E.g., Westfall, Paul and Gender, 61–69.

14. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 26, 32.

15. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 33–34.

16. Gordon Fee, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, NICNT (Eerdmans, 1987) 502.

17. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 40f.

18. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 40f.

19. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 67. See also 1 Esdras 4:14–17.

20. Kevin Vanhoozer, “Human Being, Individual and Social,” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine, ed. Colin Gunton (Cambridge University Press, 1997) 173.

21. Jer 31:32. The result is we now want to obey the law and by grace, in Christ, we can, though until heaven imperfectly so.

22. Murray J. Harris, The Second Epistle to the Corinthians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, NIGTC (Eerdmans, 2005) 427.

23. John R. W. Stott, The Message of Galatians (IVP, 1968) 100.

24. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 147.

25. 1 Cor 15:49.

26. Rom 8:29; Col 1:15ff.

27. Lack of space precludes further discussion. See Marc Cortez’s chapter, “The Male Messiah,” in his ReSourcing Theological Anthropology: A Constructive Account of Humanity in the Light of Christ (Zondervan, 2017) 190–211.

28. Cortez, “The Male Messiah,” 210.

29. Being unmarried is not a shortcoming, and marriage is not required for holiness. Jesus and Paul were unmarried, and Paul commends its advantages in 1 Cor 7.

30. Rom 12:1–2.

31. It seems tendentious to interpret 1 Tim 2:12 to universally deny women can teach when contradiction with 1 Cor 11:5 is a result, and when clearer and more significant passages such as Rom 12:1–8, 1 Cor 12:1–29, and Eph 4:7–13 apply equally to women as to men. 1 Cor 14:34 can similarly unfortunately be used to deny women’s participation when its concern is with disorderly “chatter.”

32. After all, they had the most cultural power.

33. “The Jew-Gentile issue was the greatest stumbling block for the gospel in Paul’s day. While Paul granted slaves and females equality ‘in Christ,’ there was not the same kind of urgency in terms of working out the social dynamics.” William J. Webb, Slaves, Women, and Homosexuals: Exploring the Hermeneutics of Cultural Analysis (IVP, 2001) 86.

34. Westfall, Paul and Gender, 147, 161.

35. Such as is experienced by people who are intersex, or DSD (disorders of sex development).

Extend your influence and impact for generations to come.

Designate CBE as a beneficiary of life insurance, retirement assets, real estate, or other financial accounts. These gifts generally escape estate, inheritance, and income taxes.

When you leave funds to family, it may create a taxable event, and your loved ones will be taxed accordingly. However, by designating CBE as a beneficiary, you eliminate the tax bill and provide meaningful support for the mission of CBE, which means so much to you. Then, you can give more tax-efficient gifts to provide for the needs of your loved ones.

Simply designate CBE as a beneficiary on the forms provided by your life insurance provider, retirement plan administrator, or financial institution, and specify the amount you want to give.

What you need from us:

Legal Name: Christians for Biblical Equality 122 West Franklin Ave, Suite 610 Minneapolis, MN 55404-2426

Tax ID Number: 41-1599315

Ian Payne is executive director of Theologians Without Borders. He was principal and head of the department of theology at South Asia Institute of Advanced Christian Studies (SAIACS), Bangalore, India, from 2008 to 2018. He has his PhD in theology from the University of Aberdeen, UK, focused on epistemology, God’s love, and Karl Barth. He is the author of Wouldn’t You Love to Know? Trinitarian Epistemology and Pedagogy and The Message of Humanity (IVP, anticipated). The son of New Zealand missionaries, he grew up in India. After being an architect in New Zealand, he received an MTh at SAIACS in the mid-90s, accompanied by his wife, Judith, and three daughters. From building church buildings, he has been drawn into the excitement of building the church. He has retired from being interim pastor at Eden Community Church, Auckland, and through Theologians Without Borders continues to serve global theological education.

Victim Blaming and the David and Bathsheba Narrative

J. Dwayne HowellA few years ago, I found several colleagues across various schools in deep discussion over the question of Bathsheba’s innocence or guilt in 2 Samuel 11. This was on the theologically astute site known as Facebook. As I read the comments, I offered my insights, given that one of my dissertation chapters is on David and Bathsheba. I have thought about this discussion, often asking: why is there a need to save David at the cost of blaming Bathsheba?

Many denominations have been affected in the past several years by scandals concerning sexual abuse and the cover-ups that sought to hide the abuse.1 Victims of such abuse are further victimized by insinuations that they were willing participants or that they entrapped the men involved—men who are often in positions of leadership. Referred to as victim blaming, the men absolve themselves by deflecting personal accountability onto the victim. Related to this is toxic masculinity in churches where the submission of females to males is emphasized. This allows for situations with the potential for a variety of abuses: physical, psychological, and spiritual. This essay acknowledges that there is a spectrum of possible abuse in a church or other institution. However, the focus is the abuse of females by male authority figures.

The David and Bathsheba narrative of 2 Samuel 11 provides an example of such abuse. While the biblical text does not accuse Bathsheba of any wrongdoing, interpretations of the text sometimes situate Bathsheba as seducing David into adultery.

Literary Analysis of 2 Samuel 11

The narrator uses the introduction in v. 1 both to begin the story and to provide a transition from the previous chapter (2 Sam 10) by tying it to the theme of war.2 Spring is when “kings go out to battle.” David does not go to battle, but instead sends Joab out to lead on his behalf. The narrator establishes irony in the introduction by contrasting David with other kings.3 While other kings go to war, David does not. While Joab and the soldiers leave home, David remains at home.4

The use of Hebrew verb “to send” serves an important role in the narrative. It emphasizes that David is the central focus of the narrative. It is used twelve times in the story (11:1–27), playing a role in each part except the conclusion (v. 27b).5 In each scene, “send” brackets the action. In Scene One, David sends to enquire about the beautiful woman and then sends for her. The scene closes with the woman sending a message that she is pregnant.6 Scene Two begins with David sending for Uriah and ends with David promising to send him back if he would stay another day. In Scene Three, David sends Uriah’s death warrant to Joab through Uriah, unbeknownst to Uriah. Joab then sends a messenger to tell David that Uriah is dead. The final scene simply states that David sends for the woman and marries her. Significantly for this word motif, the next narrative (2 Sam 12) begins “And the LORD sent Nathan to David.” The narrator is concerned with David’s actions throughout the story. As the

narrative proceeds, the emphasis is placed increasingly on David’s actions, not Bathsheba’s.

Verses 2–5 introduce Bathsheba to the narrative. David is walking on his rooftop after resting (v. 2). From this vantage point, David sees a beautiful woman bathing. After asking, he finds that the woman is Bathsheba, daughter of Eliam and wife of Uriah the Hittite. David sends for the woman, but nothing is said about his inner motivation for the summons. As Kyle McCarter puts it: “The most egregious behavior possible on the part of the king is attributed to David without a word of mitigation.”7

Does Bathsheba purposely bathe outside to be seen by David? The narrator does not address this possibility, nor does the narrator seem to care about Bathsheba’s motives. The emphasis is on David’s initiative in the relationship that follows.8 Bathsheba is a passive character, acted upon rather than acting.9 The reader is not told whether she comes willingly or is forced. Outside of Bathsheba’s mourning for her husband (v. 26) and her son (12:24), nothing is known of her emotions.10 Bathsheba serves merely as the character David acts on through rape. When she is referred to, it is nearly always by the generic “woman” or “wife” (vv. 2, 3, 5, 11, 26, 27) and as such, related to a male (daughter of Eliam, v. 3; wife of Uriah, vv. 3, 26; David’s wife, v. 27).11 Only once is she called “Bathsheba” in the narrative (v. 3). Walter Brueggemann asserts: “She has no existence of her own but is identified by the men to whom she belongs.”12 In the culture of the ancient Near East, women had few rights and found their protection by being attached to a male. The narrator discloses just the one fact about Bathsheba: she is bathing to ritually cleanse herself after her monthly period (v. 4).13 Significantly, the readers are told this fact after intercourse has occurred, so they are not surprised by the message that Bathsheba sends David: “I am pregnant” (v. 5).

The barebones style picks up again near the end of the story as it concerns Bathsheba: she mourns; David sends for her, brings her to the palace, and marries her; she bears him a son (vv. 26–27a). The conclusion ties together David’s sexual wrongdoing and his murder of Uriah.14