MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO DE BUENOS AIRES 2025

Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires

AUTORIDADES

JORGE MACRI

JEFE DE GOBIERNO DE LA CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES

GABRIEL CÉSAR SÁNCHEZ ZINNY

JEFE DE GABINETE DE MINISTROS

GABRIELA RICARDES

MINISTRA DE CULTURA

VICTORIA NOORTHOORN

DIRECTORA DEL MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO DE BUENOS AIRES

SOFIA BOHTLINGK —————

EL RITMO ES EL MEJOR ORDEN

SOFIA BOHTLINGK ————

EL RITMO ES

EL MEJOR ORDEN

TEXTOS DE

SOFIA BOHTLINGK

FERNANDO GARCÍA

VICTORIA NOORTHOORN

JUAN TESSI

Sofia Bohtlingk : El ritmo es el mejor orden / Sofia Bohtlingk ... [et al.]; Director Victoria Noorthoorn ; Editado por Martín Lojo ; Alejandro Palermo. - 1a edición bilingüe. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Secretaria Cultura GCBA. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2025. 208 p. ; 23 x 16 cm.

Traducción de: Ian Barnett ; Leslie Robertson.

ISBN 978-987-22339-1-4

1. Arte. 2. Arte Argentino. 3. Arte Contemporáneo. I. Bohtlingk, Sofía III. Noorthoorn, Victoria, dir. IV. Lojo, Martín, ed. V. Palermo, Alejandro , ed. VI. Barnett, Ian, trad. VII. Robertson, Leslie, trad. CDD 760.1

Este libro fue publicado como documentación y complemento de la exposición Sofia Bohtlingk: El ritmo es el mejor orden, que tuvo lugar entre el 21 de noviembre de 2024 y el 6 de abril de 2025.

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Av. San Juan 350 (1147) Buenos Aires, Argentina

Impreso en Argentina

Printed in Argentina

Akián Gráfica S. A. 2992, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires

Créditos fotográficos

Archivo Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Rosario Castagnino+macro: 144-145

Ariel Authier: 101-115, 118-119

Sofía Bohtlingk: 73, 136-137

Bruno Dubner: 121, 127

Viviana Gil: 35-71, 75-87, 123

Carlos Herrera: 146-147

Ignacio Iasparra: 128-129

Guido Limardo: 158-159

Nicolás Mastracchio: 116-117, 130-133, 138-143, 149-153

Cortesía Galería Sendrós: 125, 134-135, 154-155

Josefina Tommasi: 160-169

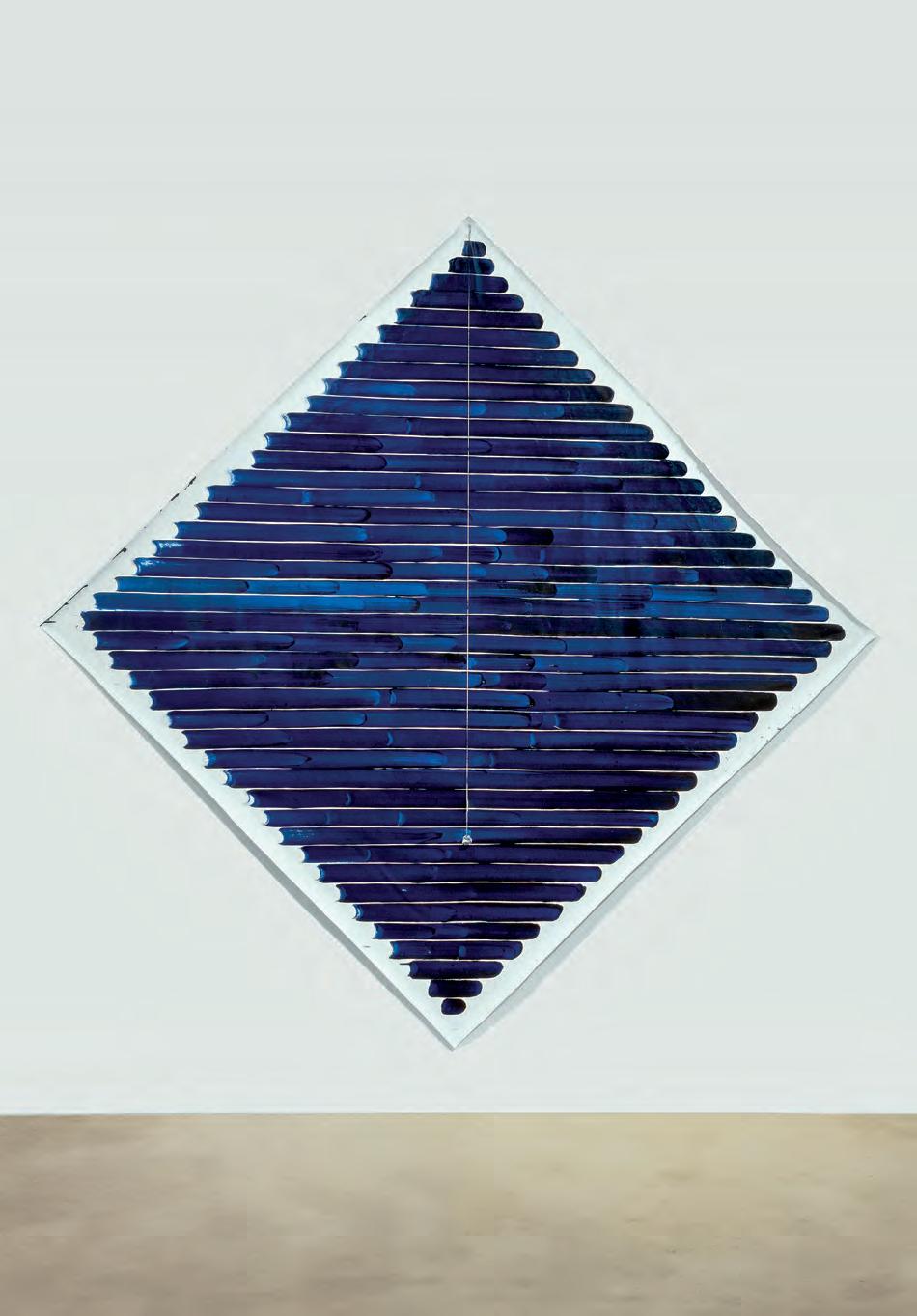

Imágen de tapa: Te dominaré lentamente, 2012

PRÓLOGO

Por VICTORIA NOORTHOORN

"POR FIN FRENTE A ELLA..."

Por SOFIA BOHTLINGK

GRACIAS POR DEVENIR

Por FERNANDO GARCÍA

ME GRITARON RUBIA

Por JUAN TESSI

LÍNEAS Y CUERPOS I

EL RITMO ES EL MEJOR ORDEN

OBRAS

PLAYLIST

ESTO ES UNA NUBE DE BERDAD

Por SOFIA BOHTLINGK

LÍNEAS Y CUERPOS II

SELECCIÓN DE OBRAS 2011-2024

INTRODUCCIÓN

Por SOFIA BOHTLINGK

OBRAS

LA TABLA

Por SOFIA BOHTLINGK

LISTADO DE OBRA Y VISTAS DE SALA de EL RITMO ES EL MEJOR ORDEN

PRÓLOGO

Por VICTORIA NOORTHOORN

Al inicio de mi carrera, en alguno de mis diálogos con el curador norteamericano Rob Storr, le oí decir que una de las principales razones para elegir curar una exposición era la de intentar comprender la obra de artistas cuya complejidad no logramos abarcar. La experiencia y tantos años de trabajo me confirmaron la verdad de sus palabras, y hoy creo fervientemente que curar es adentrarse en un universo artístico que muchas veces se nos resiste para intentar comprender aquella pulsión que lleva al artista a crear. Transitar ese camino de la mano del artista, en diálogo, es una de las razones por las cuales tantos apasionados del arte elegimos esta profesión, que nos permite movernos de la mano de la empatía, el reconocimiento de la propia sensibilidad y el ejercicio de la humildad ante la maestría de otras inteligencias, sensibilidades y formas de lo humano.

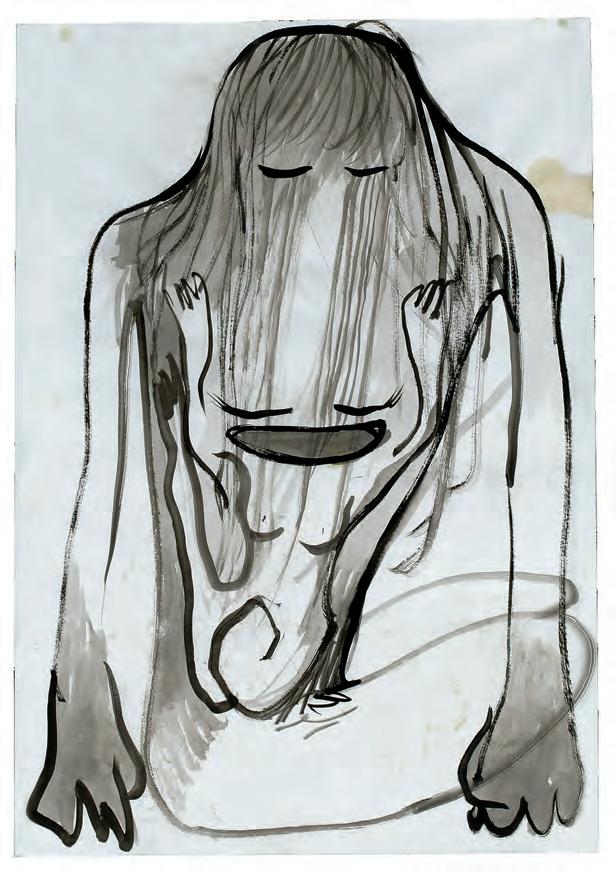

Al abordar este libro tan especial dedicado a la joven gran artista argentina Sofia Bohtlingk, recordé aquellas palabras de Rob, sobre todo cuando mi equipo editorial sugirió que requería un prólogo más personal que los que solemos publicar. Y no pude sino pensar en los enigmas que despiertan los dibujos de Sofia, y en aquel día en la Galería Nora Fisch, hace ya varios años, cuando me topé con un par de sus acuarelas figurativas que —debo aquí recurrir al lenguaje coloquial— me volaron la cabeza. Ver aquellos dibujos de humanos no humanos, mitológicos,

madres, gestantes o gestados, dramáticos, profundamente vitales, asertivos del poder de la existencia de la humanidad y del arte, fue el comienzo de una búsqueda obsesiva por saber más.

Durante meses pregunté por aquellos dibujos mientras imaginaba invitar a Sofia a una exposición en el Moderno con una consigna: mostrar esos dibujos o desarrollarlos como un guion, darles potencia, considerarlos avisos de mundos y seres poderosos por venir. Pregunté y pregunté, pero los dibujos no llegaban; el voraz devenir cotidiano del Moderno se comía el tiempo y el tiempo pasó, con aquellos dibujos siempre en mi mente, dejando su estela en algún lugar de mi memoria.

Un día me dije: este es el momento, estén listos o no Sofia y el Museo. La llamé a Nora Fisch, le pedí que me trajera todos los dibujos de esa serie. Y sucedió lo mejor que podía suceder. Una tarde de martes, envueltas en el silencio del Museo cerrado, Nora y Sofia aparecieron con todos los dibujos. Cuando digo todos me refiero precisamente a aquellos dibujos inquietantes de seres en el umbral entre la realidad y la mitología, entre la ficción y el imaginario y asimismo a todos los dibujos abstractos que Sofia y Nora tenían consigo. Con nerviosismo y entusiasmo, desplegamos los dibujos de Sofia sobre las mesas del Café del Museo. Los observamos. Los observé detenidamente. Y pasó lo que suele pasar con las grandes obras de arte: hablaron. Tal y como sostiene el gran teórico W.J.T. Mitchell, las grandes obras de arte nos hablan y expresan sus deseos más profundos: nos dicen qué quieren hacer.

Y aquellos dibujos, aquel día, hablaron y se hicieron oír con suma claridad. Nos dijeron: queremos estar juntos, existimos en relación los unos con los otros. No somos figurativos o abstractos, todos somos los hijos de Sofia, nos referimos y traducimos el ritmo de su respiración, somos la extensión de su cuerpo y de su imaginario. Somos sistema. Somos existencia. Somos uno.

Rápidamente, subimos a la sala que antecede a las salas de Patrimonio del Moderno, y desplegamos allí, en ese pasillo convertido en sala, los dibujos de Sofia. Los alternamos unos con otros, siguiendo un ritmo que era el del diálogo entre ellos, que contaban, así, una historia de vida, de existencia, de aquello que somos, decimos, imaginamos. Ese guion, esa historia, finalmente devino exposición, y luego, ahora, deviene libro. Es el guion que nos permite conocer

a una artista para quien su arte es una extensión de sí misma y quien, creo yo, vincula como nadie su ser artista con su ser mujer, ser cuerpo, ser madre.

Bienvenidos a esta historia de una artista argentina libre y feliz, aurática, bondadosa y generosa, que ama, teme, sufre y siente como todos, pero que comparte cada vivencia a través de un arte vital, siempre en mutación y transformación.

Gracias, Sofia Bohtlingk, por tu confianza; gracias, Nora Fisch, por tu generosidad y apoyo, y a todos los involucrados en la exposición y en este libro, ¡gracias por hacerlo posible!

¡Bienvenidos, lectores y entusiastas observadores!

Por fin frente a ella, respiro aliviada.

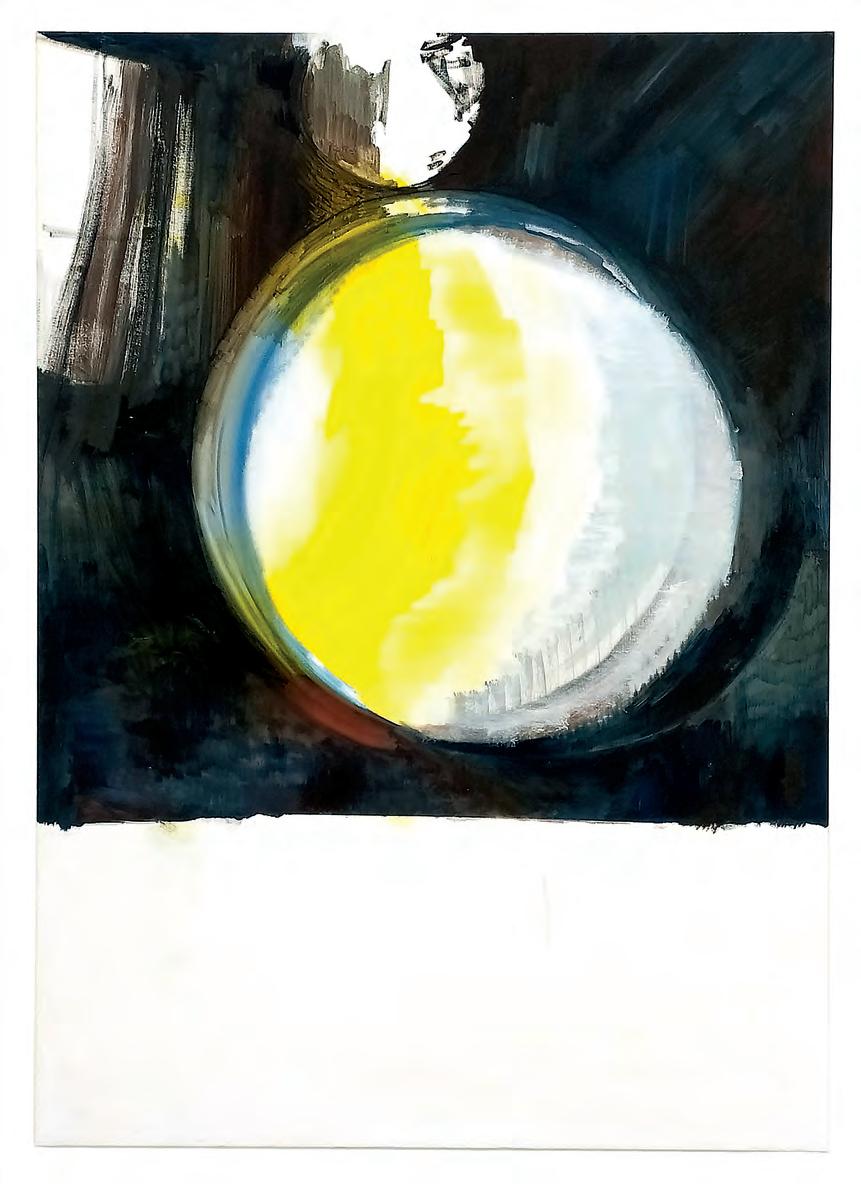

Es como si fuera observada desde un punto muy lejano. Parece un izamiento de la bandera, o algún tipo de ceremonia. Varias personas acompañan la ceremonia, se derraman hacia abajo formando un triángulo aplastado por la gravedad.

La que iza la bandera sostiene algo. Y otras personas y otras y otras y más abajo, se empiezan a confundir, parecen follajes, plantas, yuyos entrecruzados.

Toda esta pirámide aplastada está pintada de negro, pero es plana. Si pasaras la lengua no sentirías un relieve, sería como chupar un Vermeer.

Está de negro porque recién, recién parece estar amaneciendo. Y el cielo se cubre en segundos de esa luz disparada. A esa hora, una vez que esos rayos tocan el borde, nada los detiene, son abducidos por la tierra.

¡Pero la luz es plateada! Hay una lucha entre el nublado y la luz. Todo en el centro se ve blanco, luz radiante, hay demasiada luz. Las figuras y el mástil parecen derretirse en el centro, pero todo el resto es gélido.

El centro brillante, enceguecedor, intenta avanzarles a las nubes negras, grises, azules del cielo, les avanza recto. Como yo ahora sosteniendo el lápiz a noventa grados porque se está quedando sin punta, llega arriba.

Las nubes azules grises se pavoneaban, cargadas, y ahora, abochornadas, son atravesadas, llega arriba, la luz cubre el cielo, llena toda la esfera y baja feroz. Y a través de cada hueco diminuto que encuentra entre las nubes azules grises, cada rayo se convierte en mil, divididos de a quince grados cada uno, como si una regadera lo hubiera separado.

Hay uno, dos, cinco, siete de estos rayos que se van atomizando mientras se encuentran con la superficie y cada uno comienza a tocar lo que está debajo.

SOFIA BOHTLINGK

GRACIAS POR DEVENIR

Por FERNANDO GARCÍA

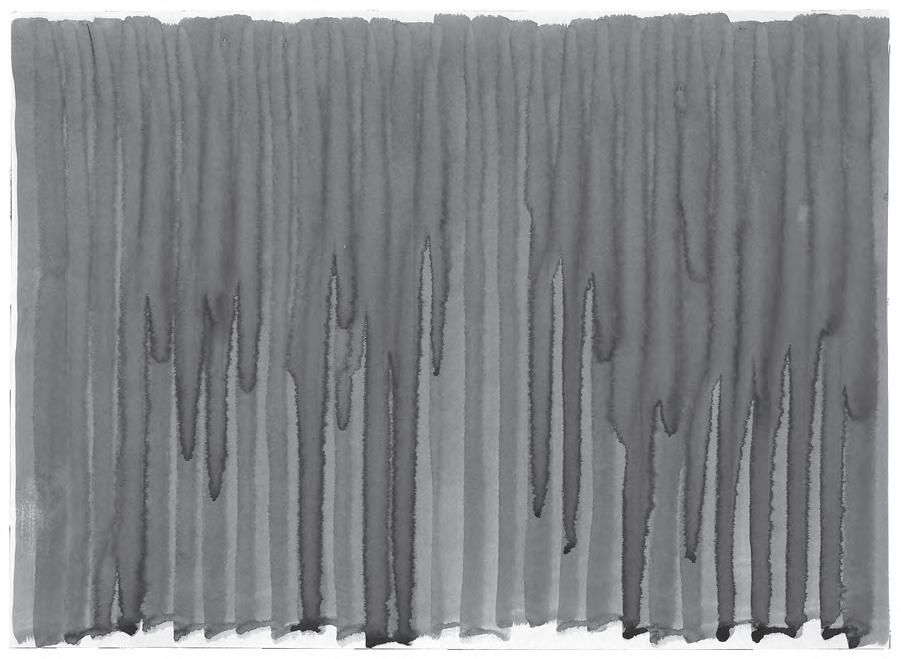

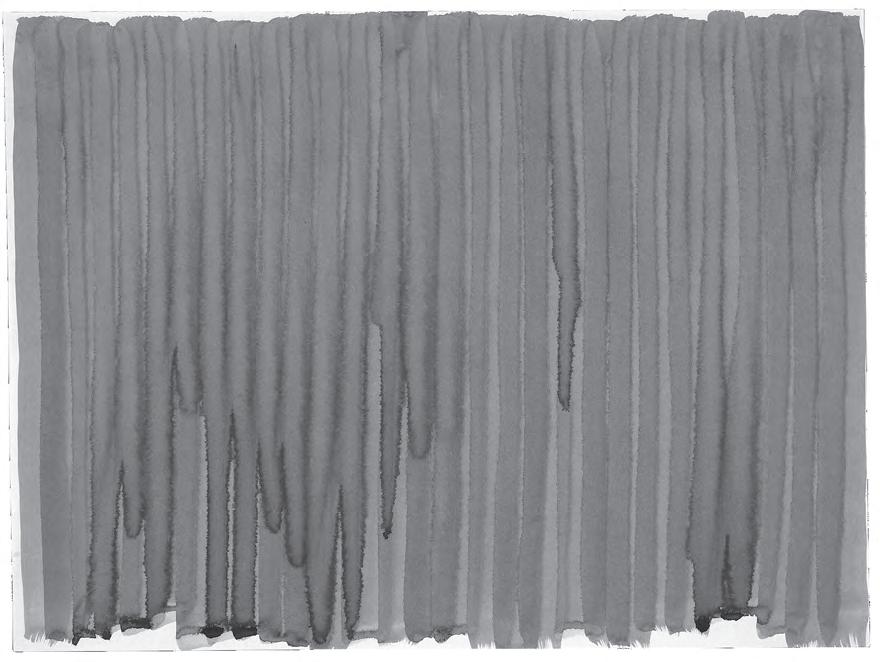

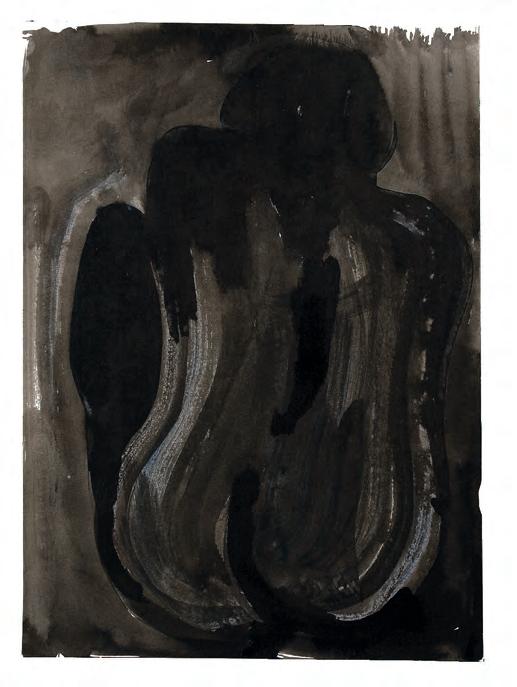

En dos acuarelas ejecutadas casi en simultáneo, Sofia Bohtlingk descubre el telón de su teatro íntimo. Dice, en los títulos, que no puede alcanzar el vacío porque su mente rebalsa de imágenes y después afirma que, en efecto, rebalsa de imágenes. Una criatura, solo un contorno, se distingue apenas de la mancha y una acuarela es casi el negativo de la otra.1 Entre 2019 y 2024, la artista se dedicó a bajar sobre el papel este aluvión de más de cincuenta fantasmas (un estado intermedio entre el boceto y la obra final) que se plasmaron en la transición de la forma abstracta a la figura humana y de la línea manifiesta, precisa, a la evanescencia del trazo no consumado. Aquí, Bohtlingk actualiza todas las categorías a partir de un mandato escrito por ella misma en su taller: “Pinto según mi deseo momentáneo”. Da lo mismo si dibuja (cuando la línea de tinta se expande y retuerce sobre sí) o pinta (cuando tantea lo invisible y deja la materialidad al borde de no ser), pero lo seguro es que, en estos papeles, todo corre hacia ahora.2 Hay

1 Este ejercicio pareciera atravesar la dibujística contemporánea. En la publicación Asterisca (2024), Lucas Di Pascuale cita el ejemplo de una obra de la neerlandesa Marijn Von Kreij (1978) que trabaja un díptico de dibujos “iguales”, en el que se pone en crisis la noción que la cultura occidental desarrolló acerca del original y su copia

2 En referencia a los versos escritos por José Alberto Iglesias (“Tango”) en 1967 para “Amor de primavera”. “Te comunicarás con él en una línea directa al infinito y verás que todo corre hacia ahora”. Publicada en el álbum póstumo Tango (Talent, 1972).

una urgencia por hacer, por no detenerse, por continuar. Por sostener el pulso de la mano y seguir el ritmo de la mente sin interrupciones.

Bohtlingk ha creado verdaderos enigmas sobre la condición contemporánea del ser en la correspondencia escindida entre las imágenes y los títulos de sus obras, impregnados del rayo misterioso que alimenta una poética impar. Resulta emblemático el de un video que registra el puro acto del goteo al pintar: Ella sabe más de mí que yo de ella. 3 Como si para saber de la artista hubiera que entrar en confianza con sus cuadros de cemento o poner el oído en estas tintas y acuarelas en las que se percibe un rumor de incertidumbre. Así, hay también aquí un desfile de nombres que son parte de una escritura en ciernes: Y si tenés que renunciar al mundo, no desesperes. Aún seguirás siendo un árbol solitario. Otra vez, hay una forma animista de acercarse a la obra y, entonces, no resulta extraño que, al nombrarlas, Sofia evoque el impacto sutil de los haikus japoneses. Algo en este conjunto dispone la necesidad de agotarlo todo, vaciarse y, a la vez, poner en evidencia el cansancio posterior como una respuesta al mandato de rendimiento y de autoexplotación que impone el régimen biopolítico del capitalismo digital. Como la artista le dijo a Lucrecia Palacios en Laguna, Isla, Nube, el libro que editó en 2019: “Muchas veces, pienso que una manera de estar tranquilo es ser invisible. Quizás uno pueda volverse invisible a través del cansancio, como cuando la repetición de una acción te vuelve transparente”.

Si se hace el ejercicio inverso, ¿qué imagen podría corresponderse con Y si tenés que renunciar al mundo, no desesperes. Aún seguirás siendo un árbol solitario? Sofia Bohtlingk tiene el don y la libertad de la niña-artista, una que nombra cosas imposibles que solo pueden representarse en una imagen que, por supuesto, no se corresponde con nada conocido. Para la niña-artista lo que se nombra lo es todo y el dibujo, esa aproximación atávica, se independiza de cualquier referencia, pero, al mismo tiempo, no puede ser ninguna otra cosa que aquello que se ha nombrado.

3 Sofia Bohtlingk, 2013. El video se vio desde entonces en distintas exposiciones en las galería Sendrós y Arte x Arte y en la Fundación Osde.

En su conferencia En busca del tiempo perdido. Por qué dibujamos y por qué dejamos de hacerlo, 4 Eduardo Stupía citaba un artículo de César Aira sobre Copi5 para dar cuenta de esto.

(…) los niños no es que sepan dibujar sino que saben qué quieren dibujar. Quieren por ejemplo dibujar una nave espacial con la computadora desacompasada por el rayo láser que le lanza un King Kong magnético a bordo de un galeón pirata atacado por un tiburón panda con dos sobrinos, uno bueno y uno malo. Como no saben dibujar, pueden hacerlo. En los niños, como en los artistas consumados, hay una voluntad positiva, libre. No es omnipotencia, es la realidad, lisa y llana, la vida aceptada como un devenir (…).

Acaso Aira escribió esto también pensando en esta serie de dibujos que Sofia Bohtlingk todavía no había realizado. No es casual, entonces, que ese mismo concepto del devenir aparezca después en la transcripción de un intercambio epistolar entre Ana Vofelgang y Bohtlingk:

9 de noviembre de 2020

Me despierto, prendo el celular. Tengo un audio de Sofia: “¿Sabés que el otro día me acordé de una palabra que vos me dijiste una vez de mi pintura? ¡Ay! No quiero ser autorreferente, tipo yo yo yo yo... Perdón... Pero es con respecto al texto y la charla que tuvimos el otro día. Me acordé de esta palabra que me encantó, que es: ‘devenir’. Bueno, eso, nada más. Te mando un besote enorme”.

Miro el cuadro de Sofia que cuelga en la pared frente a mi cama. Es una tela con pinceladas azules atravesadas por una inscripción, como una herida. Devenir, como enseñar, también es un estado. Esa pintura es ella, sujeto, objeto, sustancia, cosa.

4 Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 11 de setiembre de 2024.

5 César Aira en “Del salto milagroso por el que un ser humano se convierte en artista”, La Hoja del Rojas, julio de 1988. Publicado luego en La ola que lee, Buenos Aires, Random House, 2021.

¿Reescuchará Sofia sus propios mensajes?

Sofia Bohtlingk en el WhatsApp, 21/11/24, 09:41

Con Julieta García Vázquez hice un texto sobre unas pinturas que no existen pero que las describís, como que te las imaginás. Es un proyecto que se llama Amor mía. Son pinturas leídas que no existen y… Cuando estaba en cuarto grado del colegio me pasó algo como cuando decís… Uy, ¿pintar es esto? Una mañana estaba formando en fila en el izamiento de la bandera o algo y como que pasaba esto con las nubes. Mi colegio daba al río Reconquista y se veía todo plateado. Como que estaba medio amaneciendo y se metían rayos de sol entre las nubes y en la clase de plástica lo pinté y me re impresionó la idea de que algo podía ser visto y después dibujado. Fue una sensación muy fuerte tomar conciencia de eso. Creo que ese dibujo tiene mucho que ver con los colores que hago ahora. Con los negros, los grises y las rayas. Algo medio relacionado con el romanticismo, no sé. Bueno, vos sabés.

Pero es ella la única que sabe sobre los rayos del sol filtrados entre las nubes, plateando el Reconquista. Y la que me explica sobre una figura que resulta tutelar para este conjunto de obras, la de la coreógrafa, compositora y diseñadora peruana Victoria Santa Cruz (1922-2022), de la que Bohtlingk se impregnó al escucharla decir que “el ritmo es el mejor orden”. Así, la artista se dispuso como una atleta afectiva6 (la chica de Vitrubio que pinta el largo de sus brazos en cemento),7 ejecutando todo aquello que la rebalsaba en series no del todo identificadas. El tiempo de estos dibujos revela un espesor histórico ineludible. El trabajo de Sofía transcurrió entre la pre y la pospandemia, cuando los cuerpos del mundo revelaron una fragilidad global inédita y, así, aparecen asimétricos o intervenidos con extremidades inauditas, de una genética visual que podría rastrearse en los bestiarios neofigurativos o el art brut. La diferencia es que, en estas obras de Sofia, la instancia de encontrar un lenguaje indistinto entre figura y abstracción o mancha ya fue superada. En

6 Concepto esbozado por Antonin Artaud para su programa sobre el Teatro de la Crueldad.

7 Con Bohtlingk cobra otro sentido aquello de “te sigo desde Cemento”, alarde de la lengua popular porteña que se refiere a los inicios de los muchos artistas que debutaron en la discoteca que llevaba ese nombre. Aplicado a ella, se volvería una referencia ineludible de su ejercicio performático de la pintura y del uso de un material que pone a prueba su musculatura.

estos dibujos, la encrucijada es otra: es como si al haber atravesado el virus, la figura humana aún estuviera por rehacerse y la artista se hiciera cargo de plasmar ese ansiado regreso a la normalidad. También los debates coyunturales sobre los límites de la ciencia que se abrieron con la emergencia del covid 19 parecen asumirse aquí a partir del uso de grillas blandas, donde la severidad geométrica tiembla, o el entrevero de líneas alude al diseño de un instrumento de laboratorio trémulo, alimentado por una señal indeterminada. Frente a lo desconocido, al fin, la intuición de la artista reemplaza las certezas del instrumental científico, elevando preguntas antes que respuestas. Y es que, en la frenética búsqueda del vacío de estas obras, Sofia Bohtlingk da testimonio de la forma de un mundo que nunca volvió a ser el mismo.

ME GRITARON RUBIA

Por JUAN TESSI

Si uno no conociese a Sofia Bohtlingk y se quedase con su aspecto nórdico y un pantallazo veloz de su trabajo, asumiría que es una de esas artistas proclives a la distancia gélida y disciplina draconiana de una pintora conceptual. Pero si recorremos su producción con cuidado, nos daremos cuenta de que este prejuicio es por el disfraz que se le suele poner a la pintura que manifiesta un accionar sujeto a algún tipo de pensamiento, lo cual es problemático, porque como subgénero insinúa la posibilidad de una pintura sin ningún tipo de razonamiento. Quizá solo sea una manera de aclarar que se pensó más de lo que se pintó. O que se pensó hasta pintar con la forma de un proyecto vector. Pero en la pintura de Bohtlingk no hay nada programático y sus ideas no argumentan con la linealidad discursiva asociada con el género. La artista, poseída por sus materiales, más que conceptual, es en realidad una admirable entusiasta.

“Encendidos por una chispa divina los entusiastas esparcen el fuego a lo largo de épocas, culturas y religiones”, dice Jan Verwoert, el crítico holandés, en su breve ensayo sobre entusiasmo, amor y manía.1 Para después, citando la can-

1 Versión original en inglés: Jan Verwoert, “Enthusiasm, Love and Mania”, en revista Frieze, n° 200, enero-febrero de 2019.

ción “Rythm is a dancer”, de SNAP!, el proyecto de eurodance alemán de 1989, preguntarse: “¿Cuál es el acto si el ritmo es un bailarín?”. Montado sobre la máquina elíptica, tratando de seguirle el tempo a “Motiveishon”, de Lali Espósito, que sonaba a todo volumen en los parlantes del gimnasio, me puse a pensar en la recientemente inaugurada muestra El ritmo es el mejor orden, de Bohtlingk, en el Museo Moderno.

En un principio, pero no al comienzo, sus pinturas al óleo —enormes batallas que solo podría encarar una persona de su estatura— desplazaban la materia de un lado al otro generando un ritmo en el que la vara era su propio cuerpo. Con una predilección por el aceite de lino y el color azul, que con el tiempo viró cada vez más profundo, sus pinceladas zigzagueaban con gracia o simplemente subían y bajaban interrumpidas cada tanto por raptos de abandono (Te dominaré lentamente, 2012/Una persona seria, 2013). Sin embargo, el gesto metódico y repetitivo nunca se quedó quieto, ya que la artista pronto se distrajo con las posibilidades de nuevos materiales.

La pintura como tal ha respondido a un mundo cambiante desde su origen. Del soporte de la piedra rústica de una cueva pasó al papiro, a la pared a través del fresco, a la madera con el óleo para finalmente llegar a la tela. La historia de la tecnología de este medio ha sido, desde su origen y hasta el período de entreguerras, una permanente búsqueda de —y subordinación a— la estabilidad de los materiales y la superficie. O por lo menos así lo explica el documental de 1967 La historia de la pintura, producido por la corporación Shell, que elige ilustrar el caso con el chasis de un auto mientras es sumergido por un brazo mecánico en una batea gigante llena de pintura roja: nuevas formas fordistas de pintar del siglo XX. Por el otro lado, Douglas Crimp, en su texto seminal “El final de la pintura”,2 sugiere que Johann Wolfgang von Goethe es el primero en señalar que los franceses, a fines del 1700, comenzaron a arrancar las obras hechas in situ en Italia para llevárselas a su país. De alguna manera, presagiando la entidad artística que se gestó en París cien años después, hoy entendida como modernismo.

2 Versión original en inglés: Douglas Crimp, “The End of Painting”, en revista October, n° 16, “Art World Follies”, primavera de 1981, pp. 69-86.

Es cierto que no hay nada como desestabilizar la superficie para evitar la hasta hace muy poco denigrada categoría de pintora de atril. También es cierto que el respeto hacia la estabilidad de los materiales es más funcional al mercado que a la experimentación. Algo de esto y de andar moviendo paredes de un lado a otro aparece en su muestra Espada, de 2017, en la galería Nora Fisch. Distraída por el cemento y un ladrillo hueco roto, Bohtlingk cambió pinceles por amoladora y se lanzó a hacer una pintura/muro de 200 kilos (Pared, 2017) y un conjunto de enigmáticas esculturas/ofrendas de todo tipo de descarte, rudimentariamente atadas: platos rotos, bollos de cinta de pintor empapadas en óleo, mechones de pelo, etc. Sin duda, la producción de Sofia rebasa de ocurrencias insólitas, acciones impulsivas y una capacidad inusitada para maravillarse por las cosas que la rodean.

Pero esta vez, el conjunto de dibujos presentados en el pasillo del primer piso que desemboca en la sala F del museo —trabajos que hasta ahora se habían visto de manera esparcida e intermitente— generan un nuevo orden de ritmos que ya se podía intuir en la pintura que nos daba la espalda (Mamá robot, 2022) al entrar en la exhibición Ilusión y bochorno, de 2023. El trabajo de aquel entonces sugería, pudorosamente, una espacialidad reminiscente de sus paisajes cósmicos/heavy metal más tempranos. Pero en este caso, su uso de la línea delataba una fuente, no un boceto, pero sí un origen, que era sin duda un dibujo. No recuerdo quién dijo, hablando sobre pintura, que si la superficie es pública, la profundidad es privada. Y si bien ahora el recorrido nos recibe con el paredón de una de sus pinturas en concreto (Invisible, 2015) —pura superficie—, hay que decir que los dibujos, trabajos que van del 2019 al 2024, son un abismo del que no dan ganas de salir.

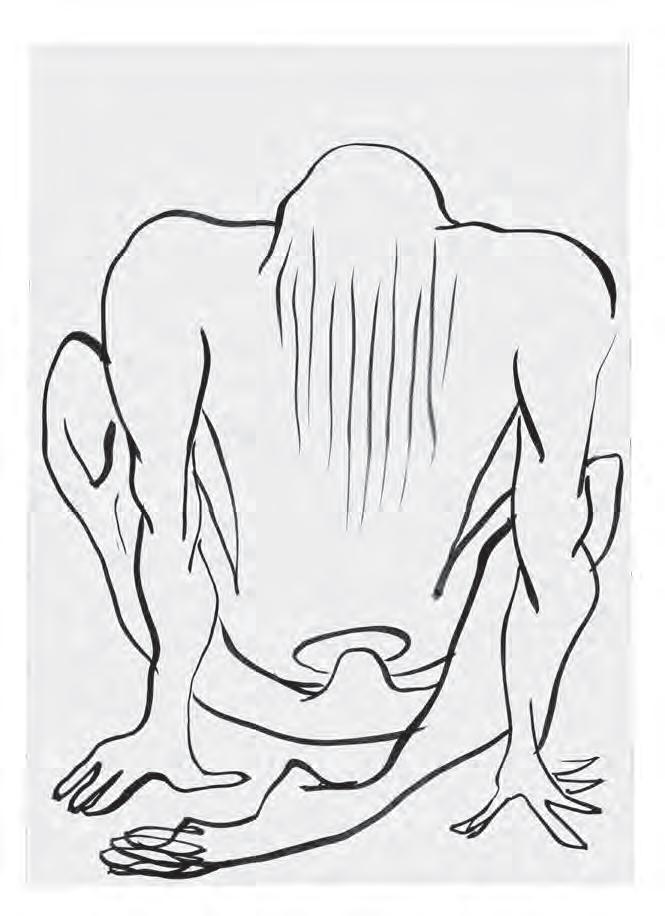

Con curaduría de Victoria Noorthoorn, los delicados papeles conforman una muestra íntima que da lugar a la figura y la abstracción en conjunto. Si bien el cuerpo ha sido el canal predilecto para pensar el trabajo de esta artista, la forma humana como tal es un recurso curiosamente desterrado del léxico de Bohtlingk, que supo ser habitué de la Asociación de Estímulo de Bellas Artes, donde se podían tomar cursos de modelo vivo. Prolijamente ordenados en grupos, algunos pocos dan la sensación de ser bocetos para pinturas que ya sucedieron. Otros parecen ensayos de formas y líneas repetitivas que le suman musicalidad al espacio. También hay experimentos donde mezcla óleo con tierra y pedacitos de cemento, resultado de prácticas performáticas en las que

pinta sin pintar, dejando que la materia haga lo que quiera mientras elucubra dispositivos para sostener su propio cuerpo. Y por último las figuras: una mujer con pelos al viento y una indigestión de sonrisa pícara; otra que le hace de espejo con un crío a cuestas; una de cuerpo blando con cuatro tetas tragando desaforada; varias haciendo imposibles posturas de yoga (a una incluso se le puede ver cómo el ejercicio la hace irradiar su propia aura); de pelo larguísimo y de pelo corto; solas, la mayoría, y una acompañada (las dos mujeres enfrentadas en algún tipo de rito pagano), las hay de frente y las hay de espalda.

De estas últimas hay un pastiche de Victoria Santa Cruz, la coreógrafa, activista, feminista, poeta y diseñadora afroperuana autora del emblemático poema rítmico, publicado en 1978: “Me gritaron negra”. La poeta escribió su estremecedor himno sobre la negritud inspirada por la primera experiencia de discriminación que vivió a los cinco años. Vivencia que raudamente plasmó en un cuaderno. Dice la autora que fue en ese momento cuando empezó a descubrir la vida. Claramente hay experiencias de nuestra infancia que nos marcan para siempre.

En las antípodas, cuenta Bohtlingk que más o menos a esa misma edad, mientras en el patio del colegio se alzaba la bandera recortada contra la madrugada del río Reconquista, quedó hipnotizada por los haces de luz que se filtraban a través de las nubes. Sus ojos celestes, del color de sus esculturas de vidrio templado (Corte pulido brutal (bruxisme), 2016), pudieron ver el fenómeno con tanta claridad que inmediatamente entendió la posibilidad de replicarlo en lápiz y papel.

Las comparaciones resultan odiosas, sobre todo entre pintura y dibujo, principalmente porque la pintura siempre sale perdiendo. De hecho, recuerdo a un maestro decir que nunca es buena idea mostrarlas juntas. Sin embargo, hay que decir que el conjunto de trabajos de Bohtlingk aquí reunido parece informar y ampliar nuestra comprensión de su obra pictórica casi de la misma manera o más que lo que lo hacen los brillantes títulos a los que nos tiene malacostumbrados.

La historiadora norteamericana especializada en dibujo Bernice Rose, curadora de la muestra Drawing Now, en el MoMA de Nueva York en 1976, recorre la historia del dibujo para entender el legado de esta tradición a la fecha de la

muestra. El texto distingue el momento en el que este medio cobra autonomía como soporte de la pintura o la escultura; señala cómo pasa de ser un medio conservador a vivir un resurgimiento en los últimos veinte años; encuentra cuarenta hombres y cinco mujeres para ejemplificar su punto y explica que en el siglo XVI, Federico Zuccari, el pintor, arquitecto y escritor italiano, proclama al dibujo como una suerte de pensamiento divino que se puede distinguir entre disegno interno y disegno externo, poniendo al término disegno en el mismo plano que el de idea. El disegno interno vendría a ser la chispa divina y el externo su manifestación. “En este sentido el dibujo es la proyección de la inteligencia del artista en su forma menos discursiva”, dice Lawrence Alloway, el crítico inglés citado por Rose en el texto publicado por el MoMA sobre aquella exposición.3 Y ahí se entiende por qué a la pintura se le cuestiona todo y al dibujo nada. Porque el dibujo no titubea, es el impulso a través del cual se moldea un universo. Dice Rose, unas líneas más tarde, que en el Alto Renacimiento, cuando se entendió a la línea como el corazón del arte, incluso aquellos dibujos “que demostraban un desapego intelectual eran apreciados como indicativos de pensamientos privados, minuciosamente revelados”.

“¿Cuál es el acto si el ritmo es un bailarín?”. No consigo encontrar respuesta a la pregunta de Verwoert. Y eso debe de ser algo bueno, porque quiere decir que no le puedo poner palabras a los ritmos de Sofia. Lo único que puedo decir es que la fragilidad del papel y la inmediatez de este tipo de línea (tinta, acuarela, fibra) dan rienda suelta a la pulsión primitiva y al instinto animal de esta artista. Con su trazo, la pintora hurga hondo en su deseo con el entusiasmo libre, tenaz, y la inteligencia milenaria de un husky siberiano. Pero al compás de un preludio inquieto de Debussy. Al fin y al cabo, como dijo hace ya rato Seth Price, el artista posconceptual, “el arte es el resultado productivo de una mirada atípica, de un pensamiento raro y de acciones extrañas”.4

3 Bernice Rose, Drawing Now, Nueva York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1976.

4 “Art is the productive outcome of wrong seeing, odd thinking, strange action.” Versión original en inglés: Seth Price, “Wrong Seeing, Odd Thinking, Strange Action”, en revista Texte Zur Kunst, n° 106, “The New Left”, junio de 2017.

LÍNEAS Y CUERPOS I

EL RITMO ES EL MEJOR ORDEN

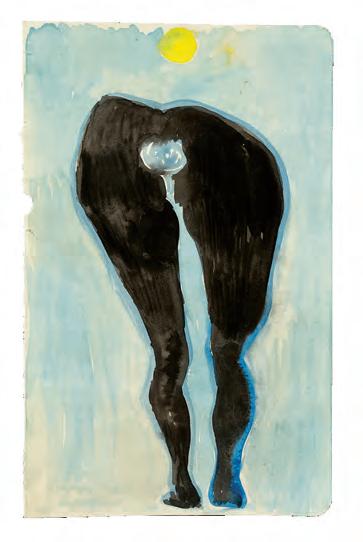

zzzshshsh, 2023

Cama, 2022

Sí, 2021

Luna, 2022

Sin título, 2021

Mi y yo III, 2024

Su existencia depende de las máquinas III , 2022

Un barco en el océano Índico (que es marrón) cuando hace calor, 2024

Una puede proyectar lo que quiera sobre una pintura abstracta, y esta convertirse en lo que quiera, 2024

(seis obras de la serie)

Está nevando sobre nieve vieja, 2021

La vergüenza de desear algo, 2021

Ahí está, ahí está. Unos pasos adelante. La transformación I y III, 2021

La lengua mineral, 2022

Mitad cuerpo mitad arquitectura, 2019

Empiezo a ver las primeras telarañas, 2019

Sin título, 2021

Sin título, 2019

Sííí nooo, 2024

Ver la línea, la ves, pero no existe (el horizonte), 2019

Creo que estoy rebalsando de imágenes, 2019

Sin título, 2022

Poseía, poesía, 2024

Un huevo volando, 2021

Columna, 2024

No estoy consiguiendo vaciarme, creo que estoy rebalsando de imágenes, 2024

Sin título, 2024

Sin título, 2024

Sin título, 2024

EL RITMO

ES EL MEJOR ORDEN

Diez horas con la música que SOFIA BOHTLINGK utiliza como banda de sonido en su taller

El arco de estilos, escenas y épocas del que la pintora y dibujante echa mano en su trabajo se asemeja mucho a su máxima: “pinto según mi deseo momentáneo”. Con la misma lógica, el orden de esta playlist funciona como la radio interna de la artista. Las repeticiones de bandas y solistas que se desentienden del diseño sonoro o las correspondencias estilísticas se verán replicadas en los dibujos de pequeño formato que se presentó en la exposición del Museo Moderno. Bohtlingk se revela como una melómana capaz de integrar el folclore austero de Jorge Cafrune con el blues vanguardista de Captain Beefheart, solo por citar apenas los extremos de esta playlist inabarcable que suena a manifiesto. Los 142 tracks se presentan en el mismo orden dispuesto por ella, junto con el título de la obra, el autor o intérprete y el año de su publicación, ya sea en edición original, reedición o compilado.

1. “Genius of Love”, Tom Tom Club, 1981

2. “Run Fay Run”, Isaac Hayes, 1974

3. “Lovey Dovey”, Dick Dale & his Del Tones, 1962

4. “Let’s Go Trippin’”, Dick Dale & his Del Tones, 1962

5. “The Tide is High”, The Paragons, 1967

6. “When the Lights are Low”, The Paragons, 1967

7. “Only a Smile”, The Paragons, 1967

8. “The Way it Goes”, Sneaks, 2019

9. “Anchin Kfu Ayinkash”, Hailu Mergia & Dalahk Band, 2016

10. “Sketch for Summer”, The Durutti Column, 1979

11. “Soul Alphabet”, Colleen, 2015

12. “Plagé Isolée”, Polo & Pan, 2015

13. “Wede Harer Guzo”, Hailu Mergia & Dalahk Band, 2016

14. “Tezeta (Nostalgia)”, Mulatu Astatke, 1998

15. “Nabu Corfa”, Dorothy Ashby, 1965

16. “Homesickness part 2”, Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru, 2006

17. “On the Beach”, The Paragons, 1967

18. “Steady Rock”, The Aggrovators, 2017

19. “Sonido de barco antiguo”, Relajante Conjunto de Música Zen, 2018

20. “El niño y el canario”, Jorge Cafrune y Marito, 1972

21. “Tell Me”, The Rolling Stones, 1964

22. “Afternoon Bird Chorus”, Forest Soundscapes, 2015

23. “Zambita pa’ Don Rosendo”, Jorge Cafrune y Marito, 1972

24. “Cold Blooded Old Times”, Smog, 1999

25. “Baby”, Donnie & Joe Emerson, 1979

26. “Texas Sun”, Khruangbin & Leon Bridges, 2019

27. “Valerie”, Amy Winehouse, 2006

28. “Ene Alantchi Alnorem”, Girma Hadgu, 1998

29. “Sintayehu”, Hailu Mergia & Dalahk Band, 2016

30. “The Homeless Wanderer”, Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru, 2006

31. “Migibima Moltual”, Hailu Mergia & Dalahk Band, 2016

32. “These Days”, Nico, 1967

33. “Come Live With Me”, Dorothy Ashby, 1968

34. “Embuwa Bey Lamitu”, Hailu Mergia & Dalahk Band, 2016

35. “Inlbesh”, Hailu Mergia & Dalahk Band, 2016

36. “My Future”, Billie Eilish, 2020

37. “Ene negn bay manesh”, Girma Beyene, 2004

38. “Techero adari negn”, Alemayehu Esthete, 2004

39. “Don’t Let me Down”, Marcia Griffiths, 2006

40. “Sunday Morning”, Amanaz, 1975

41. “Bombay Talkie”, Shankar Jaikishan, 1970

42. “Extremely Bad Men”, Shintaro Sakamoto, 2014

43. “La bataille de neige”, Domenique Dumont, 2015

44. “Deep Shadows”, Little Ann, 2019

45. “This World Should Be More Wonderful”, Shintaro Sakamoto, 2014

46. “Dreaming”, Sun Ra, 1963

47. “Yemanesh Aniyama”, Hailu Mergia & Dalahk Band, 2016

48. “Will You Promise”, Ebo Taylor, 1975

49. “Volta jazz”, Bi Kameleou, 2016

50. “Tearz”, El Michaels Affair, Lee Fields (The Shacks), 2017

51. “San Franciscan Nights”, Gabor Szabo, The California Dreamers, 1967

52. “Black Man’s World”, Alton Ellis, 2003

53. “Gypsy Woman”, Joe Bataan, 2008

54. “Leave the Door Open”, Bruno Mars y Anderson Paak (Silk Sonic), 2021

55. “Adam and Eve”, Nas, The-Dream, 2018

56. “Wayakangai”, Camayenne Sofa, 1976

57. “Saana”, Ebo Taylor, 1978

58. “Vida antigua”, Erasmo Carlos, 1972

59. “Mother’s Love”, Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru, 2006

60. “Oh Yeah”, Yello, 2006

61. “Sea of Love”, Cat Power, 2000

62. “Danza negra”, La Tropa Colombiana, 2016

63. “La cumbia rebaja”, Aniceto Molina, 2016

64. “Blue World”, Mac Miller, 2020

65. “Be My Baby”, The Ronettes, 1964

66. “Me and Bobby Mc Gee”, Janis Joplin, 1971

67. “¡Me gritaron negra!”, Victoria Santa Cruz, 2003

68. “I Hope You Die”, Molly Nilsson, 2011

69. “Running Up that Hill (A Deal with God.”, Kate Bush, 1985

70. “Cloudbusting”, Kate Bush, 1985

71. “N.I.T.A”, Young Marble Giants, 1980

72. “Hong Kong Garden”, Siouxsie and the Banshees, 1978

73. “Lobo-Hombre en París”, La Unión, 1984

74. “I’m Having too Much Sex Blues”, Netherfriends, 2017

75. “Sketch for Summer”, The Durutti Column, 1979

76. “La fama”, Rosalía, The Weeknd, 2021

77. “Let’s Make Love and Listen Death from Above”, Cansei de Ser Sexy, 2005

78. “Atlas Eclipticalis”, John Cage, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, James Levine, 1994

79. “Ay K Emoción”, Chill Mafia Records, Yung Prado, 2021

80. “Stardust”, Hoagy Carmichael, 1947

81. “Off-peak Day Return”, Reynolds, 2020

82. “Luces rojas”, Luca Prodan, 2021

83. “Life on Mars?”, Seu Jorge, 2004

84. “Acabou chorare”, Silvia Pérez Cruz, Raul Fernández Miró, 2014

85. “Aké”, Blick Bassy, 2015

86. “Bad guy”, Billie Eilish, 2019

87. “Wap do Wap”, Blick Bassy, 2015

88. “If You Wanna Go”, Frazey Ford, 2010

89. “It’s What You Do, It’s Not What You Are”, R. Stevie Moore, 1988

90. “Drinkin’ in L.A.”, Bran Van 3000, 1997

91. “Xtal”, Aphex Twin, 1992

92. “Pulsewidth”, Aphex Twin, 1992

93. “Heliosphan”, Aphex Twin, 1992

94. “Hedphelym”, Aphex Twin, 1992

95. “La noche de anoche”, Bad Bunny, Rosalía, 2020

96. “Antes de morirme”, C-Tangana, Rosalía, 2016

97. “Me porto bonito”, Bad Bunny, Chencho Corleone, 2022

98. “Águas de março”, Stan Getz, João Gilberto, 1976

99. “Besos moja2”, Wisin & Yandel, Rosalía, 2022

100. “Players”, Coi Leray, Tokischa, 2023

101. “Work”, Rihanna, Drake, 2016

102. “Pericón nacional”, Hermanos Abrodos, 1995

103. “Galopera”, Raquel Lebron, 2017

104. “Bobby Brown Goes Down”, Frank Zappa, 1979

105. “Soul on Fire”, LaVern Baker, 1957

106. “Mama Said”, The Shirelles, 1962

107. “Nothing Can Change this Love”, Sam Cooke, 1963

108. “Hold on”, Plastic Ono Band, 1970

109. “Orchid”, Black Sabbath, 1971

110. “Aerokiwi Lagoon”, Ilkae, 2001

111. “The Spins”, Mac Miller, Empire of the sun, 2010

112. “Paint the Town Red”, Doja Cat, 2023

113. “Nikes on My Feet”, Mac Miller, 2010

114. “After Hours”, The Velvet Underground, 1969

115. “Little Wing”, Jimi Hendrix, 1967

116. “Charley’s Girl”, Lou Reed, 1976

117. “The Wind Cries Mary”, Jimi Hendrix, 1967

118. “Who Loves the Sun?”, The Velvet Underground, 1970

119. “A Well Respected Man”, The Kinks, 1965

120. “You and Me”, Penny & The Quarters, 2011

121. “Redondo Beach”, Patti Smith, 1975

122. “Sunny Afternoon”, The Kinks, 1966

123. “The Boy is Mine”, Brandy, 1998

124. “Chasing Sheep is Better to Left to Sheperd’s”, Michael Nyman, 2004

125. “From Disco to Disco”, Whirlpool productions, 1996

126. “Baby’s on Fire”, Eno, 1973

127. “Canto de Ossanha”, Baden Powell, Vinicius de Moraes, 1966

128. “Tarde en Itapoã”, Vinicius de Moraes, 2014

129. “Cosmic Dancer”, T-Rex, 1971

130. “Big Yellow Taxi”, Joni Mitchell, 1970

131. “Get it Together”, Beastie Boys, Q-Tip, 1994

132. “Flute Loop”, Beastie Boys, 1994

133. “Something’s Got to Give”, Beastie Boys, 1992

134. “I Don’t Know”, Beastie Boys, Miho Hatori, 1998

135. “Sure Shot”, Beastie Boys, 1994

136. “Can I Kick It?”, A Tribe Called Quest, 1990

137. “The Spins”, Mac Miller, Empire Of The Sun, 2010

138. “Valerie”, Frank Zappa, 2010

139. “I”, Aphex Twin, 1992

140. “Police & Thieves”, Junior Marvin, 1977

141. “Rumba”, Tindersticks, 1996

142. “Deixa a Gira girar”, Os Tincoãs, 2013

ESTO ES UNA NUBE DE BERDAD

La hizo Nina cuando tenía ocho años. Dijo que era de esos algodones que tienen algunos árboles y pensó que era una nube que se había caído.

No pesa nada y la cinta está pegada a los pelitos exteriores del algodón. Me gusta que tenga la forma de una espiral helicoidal alrededor de un gas. Creo que esa forma dibuja cualquier proceso y ofrece más posibilidades que una línea recta. Igual, la línea recta me encanta. Más todavía después de las teorías atómicas o la geometría no euclidiana, según la que dos paralelas sí se juntan. Además, esa forma hace que veamos solo una palabra de la oración: “esto” o “nube”, por ejemplo. Igual, les creo mucho a las palabras ordenadas una tras otras que forman una oración, pero cuando ves solo una u otra, son como individuos.

Lo que más me gusta es la B de Berdad. No importa que no supiera escribirla. Esa letra que repite la B de Nube, haciendo que suene de otra manera. La verdad, escrita con sus “B”, “D”, “D”, se convierte en una nube. Esta verdad es una nube. Transformándose, cambiando de estado y de forma, casi invisible y contundente. Que ganas de hacerle eso más al lenguaje, ¿qué es eso de los errores? Cada oración puede ser un individuo con sus necesidades y deseos. Cambiando las letras y el orden según en qué lugar de la espiral helicoidal están. “Cada oración está bien en su lenguaje tal como está”, escribió alguien a quien le gustaban mucho la filosofía y las matemáticas. Todavía no llego a entender bien, creo, lo que quería decir. Pero me gusta que aparezca “la oración” y que aparezca “está bien tal como está”, y que aparezca “en su lenguaje”, el lenguaje de cada oración.

SOFIA BOHTLINGK

LÍNEAS Y CUERPOS II

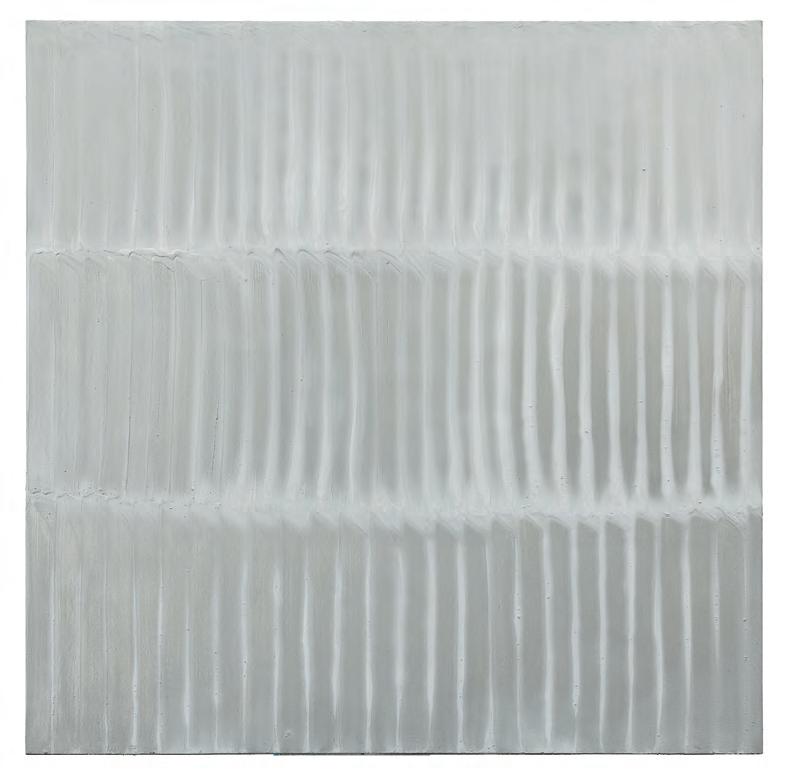

La línea se apoya en la superficie y no se levanta hasta terminar. En el camino, no hace sombreados ni ornamentos.

En los papeles, el cuerpo está entero. Los cuerpos quieren entrar en el espacio de una hoja y, si es necesario, se contorsionan.

En las telas, los brazos se extienden y cubren con el pincel el espacio que ocuparía un cuerpo.

Según el tamaño de la superficie, el cuerpo se va a expandir o se hará pequeño.

Un ladrillo hueco es un ladrillo que fue tirado al aire, se rompió y todos sus pedazos entraron casi justo en el reverso de un bastidor de cincuenta por cincuenta centímetros. No sobró nada, está la figura entera. El resultado es una superficie con líneas rojas.

Pero también es el pincel moldeando líneas en el cemento, como en Escribir, o pintando líneas con el óleo.

Siempre, la que hace es una línea.

SOFIA BOHTLINGK

Mar, 2021

Cómo inventarse un espacio, 2020

Fernet, 2021

Rectángulo, 2022

La fuente cisne, 2022

Y, S, L, 2022

Caen las notas, 2017

Vista de sala de la exposición Ilusión y bochorno Galería Nora Fisch, Buenos Aires, 2022-2023

Nadie (o todos) saben que un trazo sale bien de casualidad y temblando, 2017

Pared, 2017

Vista de sala de la exposición Espada, Galería Nora Fisch, 2017

Dos vistas de:

Todos saben algo sobre el futuro, 2014

Una isla o una aleta de cemento, 2017

Escribir, 2016

Señor, ¿quiere unirse a nosotros? No, gracias, 2013

Escultura, 2014

Parecía la sombra de una ballena pasando por abajo, 2014

Color a la guerra y la paz, 2013

Vista de sala de la exposición Futuro, Galería Alberto Sendrós, Buenos Aires, 2013

Fotograma del video

Ella sabe más de mí que yo de ella, 2013

Todo lo que es mimetizarse con la tierra y los mármoles, 2017

Bola es todo, 2014

Te dominaré lentamente, 2012

Vista de sala de la exposición Las confesiones, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Rosario Castagnino+macro, 2012

Veo que me ves sonreír, 2014

Performance junto a Florencia Vecino Ciclo Performatón, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Salón, 2017

Catherine, 2011

Vista de sala de la exposición No sé en qué utopía futurista viven, Galería Alberto Sendrós, Buenos Aires, 2011

Nunca, 2011

LA TABLA

En una de las últimas escenas de Titanic , ella está acostada sobre una tabla, mientras él apoya su mano y el codo cerca, intentando mantenerse a flote. Sus pies ya deben estar congelados por el frío del océano Ártico y ella tiene los labios morados.

En la escena están ella, él y la tabla, rodeados de un azul casi negro que solo kilómetros y kilómetros de este color y vacío pueden dar.

Él se sumerge lentamente en la profundidad, como Holly Hunter en La lección de piano, y ella es rescatada con el abrigo de él, marrón y empapado.

Pasan varias horas y los botes ya se alejaron. Se escuchan ruidos desde el barco, como una ballena hueca que se llena de agua y va chocando contra los acantilados de hielo, kilometros abajo de la superficie. Se escuchan los sonidos de la onda más grande, moviéndose lentamente en el agua. Y la tabla de pronto se encuentra envuelta en el azul más oscuro y brillante del océano Ártico.

La tabla escucha el sonido de su propia madera chocando contra el agua. Ella no siente el frío y puede flotar.

SOFIA BOHTLINGK

EL RITMO ES EL MEJOR ORDEN

LISTA DE OBRA Y VISTAS DE SALA

GALLERY VIEWS AND CHECKLIST

OF THE EXHIBITION RHYTHM IS THE BEST ORDER

zzzshshsh, 2023

Fibra sobre papel [Marker on paper]

19 × 28 cm

Colección Gala Elman y Emiliano Grodzki p. 35

Cama [Bed], 2022

29,6 × 20,5 cm

Fibra sobre papel [Marker on paper]

Colección de la artista p. 37

Luna [Moon], 2022

29,6 × 20,5 cm

Fibra sobre papel [Marker on paper]

Colección de la artista p. 41

Sin título [Untitled], 2021

Fibra sobre papel [Marker on paper]

14,5 × 21 cm

Colección de la artista p. 43

Un barco en el océano Índico (que es marrón) cuando hace calor [A Ship in the Indian Ocean (Which Is Brown) When It´s Hot], 2024

Acuarela y tinta sobre papel

[Watercolour and ink on paper]

29,7 × 21 cm

Colección privada p. 47

Mi y yo III [Me and I III], 2024

Carbonilla y acuarela sobre papel

[Charcoal and watercolour on paper]

21 × 29,7 cm

Colección privada p. 44

Su existencia depende de las máquinas III [Their Existence Depends on Machines III], 2022

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

29,5 × 42 cm

Colección de la artista p. 45

Una puede proyectar lo que quiera sobre una pintura abstracta, y esta convertirse en lo que quiera [You Can Project Whatever You Want on an Abstract Painting, and It Can Become Whatever It Wants to Be], 2024

Acuarela y tinta sobre papel

[Watercolour and ink on paper]

21 × 28,4 cm

Colección de la artista p. 49

Una puede proyectar lo que quiera sobre una pintura abstracta, y esta convertirse en lo que quiera [You Can Project Whatever You Want on an Abstract Painting, and It Can Become Whatever It Wants to Be], 2024

Acuarela y tinta sobre papel

[Watercolour and ink on paper]

21 × 28 cm

Colección privada p. 54

Una puede proyectar lo que quiera sobre una pintura abstracta, y esta convertirse en lo que quiera [You Can Project Whatever You Want on an Abstract Painting, and It Can Become Whatever It Wants to Be], 2024

Acuarela y tinta sobre papel [Watercolour and ink on paper]

28 × 38 cm (seis obras / six works)

Colección de la artista pp. 50-53

Mi y yo II [Me and I II], 2024

Carbonilla y acuarela sobre papel [Charcoal and watercolour on paper]

21 × 29,7 cm

Colección Juan Borchex p. 55

La vergüenza de desear algo [The Shame of Desiring Something], 2021

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

30 × 42 cm

Colección de la artista p. 59

Está nevando sobre nieve vieja [It´s Snowing on Old Snow], 2021

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 30 cm

Colección de la artista p. 57

Ahí está, ahí está. Unos pasos adelante. La transformación I [There It Is, There It Is.

A Few Steps Forward. Transformation I], 2021

30 × 42 cm

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

Colección de la artista

p. 60

Ahí está, ahí está. Unos pasos adelante. La transformación III [There It Is, There It Is.

A Few Steps Forward. Transformation III], 2021

30 × 42 cm

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

Colección de la artista

p. 61

Sin título [Untitled], 2021

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 30 cm

Colección de la artista p. 67

Mitad cuerpo mitad arquitectura

[Half Body Half Architecture], 2019

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 30 cm

Colección de la artista p. 64

Empiezo a ver las primeras telarañas [I Begin to See the First Cobwebs], 2019

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 30 cm

Colección de la artista p. 65

Sin título [Untitled], 2019

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 30 cm

Colección de la artista p. 68

Sííí nooo [Yeees Nooo], 2024

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

38 × 28 cm

Colección privada p. 69

Poseía, poesía [Possess, Poesy], 2024

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 30 cm

Colección privada p. 75

La lengua mineral [The Mineral Tongue], 2022

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 29,7 cm

Colección de la artista p. 63

Ver la línea, la ves, pero no existe (el horizonte) [Seeing the Line, You See It, but It Doesn’t Exist (The Horizon)], 2019

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 29,7 cm

Colección privada p. 70

Creo que estoy rebalsando de imágenes [It Feels Like I’m Heaving with Images], 2019

Tinta sobre papel [Ink on paper]

42 × 29,7 cm

Colección privada p. 71

No estoy consiguiendo vaciarme, creo que estoy rebalsando de imágenes

[I’m Not Managing to Empty Myself, It Feels Like I’m

Heaving with Images], 2024

Acuarela y tinta sobre papel

[Watercolour and ink on paper]

21 × 29,7 cm

Colección de la artista p. 81

Columna [Spinal Column], 2024

Acuarela y tinta sobre papel

[Watercolour and ink on paper]

35 × 25 cm

Colección de la artista p. 79

Un huevo volando [An Egg Flying], 2021

20,5 × 12,6 cm

Acuarela sobre papel

[Watercolour on paper]

Colección de la artista p. 77

Sin título [Untitled], 2024

Óleo, tierra, cemento y cola vinílica

[Oil, soil, cement and vinyl glue]

42 × 29,7 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires p. 87

Sin título [Untitled], 2024

Óleo, tierra, cemento y cola vinílica

[Oil, soil, cement and vinyl glue]

42 × 29,7 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires p. 85

Sin título [Untitled], 2024

Óleo, tierra, cemento y cola vinílica

[Oil, soil, cement and vinyl glue]

29,7 × 42 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires p. 83

OTRAS OBRAS DE SOFIA BOHTLINGK PUBLICADAS

EN ESTE LIBRO

[OTHER WORKS BY SOFIA BOHTLINGK INCLUDED IN THIS BOOK]

Catherine, 2011

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

210 × 205 cm

Colección de la artista p. 151

Nunca [Never], 2011

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

200 × 290 cm

Colección Oxenford pp. 152-153

Te dominaré lentamente

[I Will Master You Slowly], 2012

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

210 × 300 cm

Colección Oxenford pp. 142-143

Ella sabe más de mí que yo de ella [She Knows More About Me Than I Know About Her], 2013

Video

2 min, 7 s

Colección de la artista pp. 136-137

Plan [Plan], 2013

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

210 × 240 cm

Colección de la artista pp. 132-133

Señor, ¿quiere unirse a nosotros? No, gracias

[Sir, would you like to join us? No, thank you], 2013

Cemento sobre tela [Cement on canvas]

200 × 200 cm

Colección privada p. 125

Color a la guerra y la paz

[Colour to War and Peace], 2013

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

200 × 220 cm

Colección Banco Supervielle, en comodato al Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires pp. 130-131

Bola es todo [Ball Is Everything], 2014

Óleo sobre tela, piolín y tapa de gaseosa [Oil on canvas, string and bottle cap]

235 × 235 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires p. 141

Escultura [Sculpture], 2014

Seis óleos sobre tela superpuestos [Six overlapping oils on canvas]

200 × 200 cm

Colección privada p. 127

Parecía la sombra de una ballena pasando por abajo [It Looked Like the Shadow of a Whale Passing Below], 2014

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

200 × 220 cm

Colección privada pp. 128-129

Todos saben algo sobre el futuro [Everyone Knows Something About the Future], 2014

Cemento [Cement]

50 × 50 × 50 cm

Obra destruida p. 121

Veo que me ves sonreír [I See You See Me Smiling], 2014

Performance junto a Florencia Vecino [Performance, together with Florencia Vecino]

Ciclo Performatón [Performatón Cycle], Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires pp. 146-147

Escribir [To Write], 2016

Cemento sobre tela

200 × 200 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. Adquirida por el Comité de Adquisiciones y Asociación Amigos del Moderno, 2024 p. 123

Caen las notas

[The Notes Fall], 2017

Cemento, ladrillo hueco, bastidor y tela

[Cement, hollow brick, stretcher and canvas]

50 × 50 cm

Colección de la artista p. 113

Nadie (o todos) saben que un trazo sale bien de casualidad y temblando [No One (or Everyone) Knows that a Clean Line Turns Out Well through Sheer Luck and Trembling all the While], 2017

Cemento sobre madera terciada [Cement on plywood]

200 × 150 cm

Obra destruida p. 115

Pared [Wall], 2017

Cemento sobre bastidor rígido

[Cement on rigid stretcher]

200 × 200 cm

Obra destruida p. 116

Salón [Lounge], 2017

Cemento y óleo sobre tela

[Cement and oil on canvas]

50 × 50 cm

Obra destruida p. 149

Todo lo que es mimetizarse con la tierra y los mármoles

[It Is All About Blending in With the Earth and the Marble], 2017

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

200 × 300 cm

Colección privada pp. 138-139

Una isla o una aleta de cemento [An Island or a Cement Fin], 2017

Cemento, madera, tela y óleo

[Cement, wood, canvas and oil paint]

200 × 150 cm

Colección privada pp. 118-119

Cómo inventarse un espacio

[How to Invent a Space for Oneself], 2020

Óleo, hierro, hilo de cera y tierra

[Oil, iron, wax thread and soil]

42 × 42 cm

Colección de la artista p. 103

Fernet, 2021

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

55 × 53 cm

Colección de la artista p. 105

Mar [Sea], 2021

Óleo sobre plástico

[Oil on plastic]

60 × 60 cm

Coleccion privada p. 101

Sí [Yes], 2021

Fibra sobre papel

[Marker on paper]

21,5 × 14 cm

Colección de la artista p. 39

La fuente cisne

[The Swan Fountain], 2022

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

197 × 140 cm

Colección privada p. 108

Rectángulo [Rectangle], 2022

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

200 × 149 cm

Colección Oxenford p. 107

Sin título [Untitled], 2022

Tinta sobre papel

[Ink on paper]

42 × 30 cm

Colección de la artista p. 73

Y, S, L, 2022

Óleo sobre tela [Oil on canvas]

Colección privada

198 × 130 cm p. 109

BIOGRAFÍA

Sofia Bohtlingk (Buenos Aires, 1976) estudió pintura con Sergio Bazán. Entre 2009 y 2010, cursó el Programa de Artistas de la Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, dirigido por Jorge Macchi. Entre 2010 y 2011, fue becaria de la quinta edición de la Beca Kuitca, dirigida por Guillermo Kuitca.

Bohtlingk explora diferentes posibilidades de la pintura a partir de los movimientos corporales propios de su producción. Sus obras se inscriben en la abstracción pictórica, pero no por su composición, sino porque escenifican la relación del cuerpo con la tela al pintar, un abordaje que se conjuga con estrategias de la performance.

Entre sus numerosas exposiciones individuales se destacan La Tierra fue una vez un animal gigante (Galería Appetite, 2008), Las confesiones (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Rosario, 2012) y Espada (Galería Nora Fisch, Buenos Aires, 2017). En 2019, obtuvo el Tercer Premio Categoría Mayores de la Fundación Amalita.

También participó en exposiciones colectivas como: Veo que me ves sonreír, performance realizada junto con Florencia Vecino para el ciclo Performaton (Museo Moderno, 2014); Empujar un ismo, curada por Javier Villa (Museo Moderno, 2014-2015); Pintura Post Post, curada por Cristina Schiavi (Fundación Osde, 2015); Omnidireccional, curada por Mariano Mayer (Centro Cultural Recoleta, 2015); quinta edición del ciclo Bellos jueves, curada por Javier Villa (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2015); XIX Premio Fundación Klemm a las Artes Visuales (2016); rro, curada por Sarah Demeuse y Javier Villa (sección “Dixit”, Arteba, 2017); tercera edición del Premio Braque (Muntref Centro de Arte Contemporáneo, 2017); Las decisiones del tacto, una de las exhibiciones de En el ejercicio de las cosas, en el marco de Argentina Plataforma ARCO, curada por Sonia Becce y Mariano Mayer (Madrid, 2017); Sacarse el sombrero para saludar, dirigida por Santiago Bengolea (Proa 21, 2018); Zig Zag, curada por Juan José Cambre para la Colección Alec Oxenford (2018); Iteraciones sobre lo no mismo, curada por Guillermina Mongan y Gonzalo Lagos (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Buenos Aires, 2019); Cuerpos blandos, proyecto dirigido por Lucrecia Palacios en diálogo con la exposición Reina de Corazones, de Delia Cancela (Museo Moderno, 2019); Asamblea de pájaros, obra en video y performance desarrollada junto a Florencia Rodríguez Giles y Julieta García Vázquez, comisionada por el Museo Moderno (2021).

Su obra forma parte de numerosas colecciones públicas y privadas. Vive y trabaja en Buenos Aires.

ENGLISH TEXTS

SOFIA BOHTLINGK: RHYTHM IS THE BEST ORDER

FOREWORD

By VICTORIA NOORTHOORN

In the conversations I used to have with American curator Robert Storr early on in my career, he would often say that one of the over-riding reasons for choosing to curate an exhibition was to delve into the work of artists whose complexity we are unable to fully comprehend. Time and experience have confirmed the truth of Rob’s words. Today I hold to the belief that to curate is to immerse ourselves in an artistic universe that resists our attempts to understand what the artist is doing. To walk this path in dialogue with the artist is one of the reasons why so many curators choose this profession: to make curating an exercise in empathy and humility.

When I approached this very special book devoted to the great Argentinian artist Sofia Bohtlingk, I recalled Rob’s words, especially when my Editorial Team suggested it required a manifestly personal foreword. And I couldn’t help remembering the day at the Nora Fisch Gallery, several years ago now, when I came across a pair of

Sofia’s figurative watercolours, which really blew my head off. Seeing those drawings of non-human humans, mythological mother-beings, gestating or gestated, affirming the sheer power of humanity and art, marked the beginning of my obsessive urge to learn more.

I imagined inviting Sofia to exhibit at the Moderno to display those drawings so that we could develop them as a script, imbue them with power, look on them as an annunciation of worlds and beings to come. But the daily whirlwind of life and work at the Moderno swallowed up the time, and the months passed. Yet those drawings were always on my mind, lingering over my thoughts.

One day I said to myself, ‘This is it. Whether Sofia and the Moderno are ready or not.’ I called up Nora Fisch and asked her to bring them in, every one of them. One Tuesday afternoon, wrapped in the silence of the closed Museum, Nora and Sofia showed up with all the drawings: those unsettling drawings of beings on the threshold of reality and mythology, fiction or the imaginary, as well as all the abstract drawings they had with them. We spread Sofia’s drawings over the tables in the Museum Café. We studied them together. W.J.T. Mitchell argues that great works of art speak to us and

express their deepest desires: they tell us what they want to do.

That day, those drawings spoke out, very clearly. They said: ‘We want to be together. We exist in relation to each other. We aren’t either figurative or abstract. We are Sofia’s children. We translate the rhythm of her breathing. We are the extension of her body and her imagination. We are indivisible. We are one.’

We hurried upstairs and there, in a corridor repurposed as a gallery space, we displayed Sofia’s drawings. We set them side by side, following the rhythm of the dialogue between them. They told a story. That script, that story, eventually became an exhibition. And now it is a book that gives us an insight into an artist for whom her art is an extension of herself, and who marries her being-an-artist with her being-a-woman, a body and a mother.

Welcome, then, to this story of an auratic Argentinian artist who is free and happy, kind and generous, who loves, fears, suffers and feels like all of us but who shares every experience through a vital art in constant transformation.

Thank you, Sofia Bohtlingk, for your trust. Thank you, Nora Fisch, for your generosity and support. And to all those involved in the exhibition

and this book, thank you for making it possible!

Welcome, devoted readers and observers!

Finally, in front of it, I breath a sigh of relief.

It feels as though I were being observed from some distant vantage point. As if it were a flag-raising, or some other kind of ceremony. Several people join the ceremony, spilling down, forming a triangle crushed by gravity.

The person raising the flag is holding something. And others, and others, and others further down, they begin to blur together, they look like folliage, plants, or intertwining weeds. This whole flattened pyramid is painted black, but it is flat. If you passed your tongue over it, you wouldn’t feel any ridges, it would be like licking a Vermeer.

It’s black because it is only just now that the sun appears to be rising. And the sky is filled in seconds with that beam of light. At that hour, once those rays hit the edge, nothing can stop them; they are carried off by the earth.

But the light is silver! There is a struggle between the cloudiness and the light. Everything at the centre looks white, radiant, there is too much light. In the centre, the figures and the flagpole appear to melt, but everything else is icy.

The gleaming, blinding centre tries to push the black, grey and blue clouds of the sky forward; it pushes them straight ahead. It reaches up, just like my pencil that I am now holding at ninety degrees because it’s going blunt. The bluegrey clouds paraded about, heavy and, now, overwhelmed, they are pierced through; the light reaches up, washing over the sky, filling the whole sphere and shining down fiercely. And through each tiny gap between the blue-grey clouds, each ray becomes a thousand rays, each separated by fifteen degrees, as if spilling through the spout of a watering can.

One, two, five, seven of these rays disperse as they meet the surface, each one beginning to touch what lies beneath.

SOFIA BOHTLINGK

THANK YOU FOR BECOMING

By FERNANDO GARCÍA

In two watercolours executed almost simultaneously, Sofia Bohtlingk draws back the curtain on her intimate theatre. She says, in the titles, that she cannot make her mind a blank because it overflows with images, and then she confirms it does indeed overflow with images. A creature, or nothing more than its outline, can be hardly discerned from a smudge, and one watercolour is almost the negative of another.1 Between 2019 and 2024, the artist devoted herself to putting onto paper a torrent of more than fifty of these ‘phantoms’ – works

in an intermediary state somewhere between a sketch and a finished piece. They capture a transition from abstract forms to the human figure, and from clear, precises lines to the evanescence of unfinished strokes. Here, Bohtlingk redefines all possible categorisations based on a statement she herself wrote in her workshop: “I paint according to my immediate desires.” It doesn’t matter whether she draws (her lines of ink expanding and twisting upon themselves) or paints (grappling with the invisible and pushing materiality to the brink of non-existence); what remains certain is that, in these roles, everything runs towards the now.2 There is an urgency to create, to never stop, to continue. To hold the pulse of the hand and keep pace with the momentum of the mind, without interruptions.

In the fractured correspondence between the images and titles of her works, steeped in mysterious flashes that nourish the odd poetics, Bohtlingk has created true riddles about the contemporary condition of the

1 This exercise seems to permeate contemporary drawing practices. In his publication Asterisca [Asterisk] (2024), Lucas Di Pascuale cites the example of a work by Dutch artist Marijn Von Kreij (1978), who created a diptych of ‘identical’ drawings that challenge the notion of the original and its copy as developed in Western culture.

2 This is a reference to the lyrics José Alberto Iglesias (‘Tango’) wrote in 1967 for “Amor de primavera” [“Spring love”]: “Te comunicarás con él en una línea directa al infinito y verás que todo corre hacia ahora” [“You’ll communicate with him on a direct line to infinity, and you’ll see that everything runs towards the now”]. Released on the posthumous album Tango (Talent, 1972).

human being. An emblematic example is a video that captures the pure act of dripping paint: She knows more about me than I know about her.3 It is as if, to understand the artist, you should immerse yourself in her cement on canvas works or attune yourself to the inks and watercolours, filled with murmurs of uncertainty. And, here too, there is a list of titles that are part of an emerging style of writing: And if you have to renounce the world, don’t despair. You’ll still be a lonely tree. Again, there is an animistic approach to the work, and so it is no surprise that, in her titles, Sofia evokes the subtle impact of Japanese haikus. Something in the series conveys her need to drain herself completely, to empty herself, while at the same time revealing the subsequent fatigue that results from the mandate of performance and self-exploitation imposed by the biopolitical regime of digital capitalism. As the artist told Lucrecia Palacios in Laguna, Isla, Nube [Lake, Island, Cloud], the book she edited in 2019, “Often, I think that one way to find peace is by being invisible. Perhaps

you can become invisible through fatigue, like when the repetition of an action renders you transparent.”

If the exercise were reversed, what image would correspond to “And if you have to renounce the world, don’t despair. You’ll still be a lonely tree”?

Sofia Bohtlingk has the gift and freedom of a child-artist, one who names impossible things that can only be represented in images that, of course, do not correspond to anything known. For the child-artist, what is named is everything, and a drawing – that atavistic approach – is independent of any references, yet at the same time, cannot be anything other than what has been named.

In his lecture, En busca del tiempo perdido. Por qué dibujamos y por qué dejamos de hacerlo [In search of lost time: Why we draw and why we stop doing it],4 Eduardo Stupía quoted an article written by César Aira on Copi5 to account for this occurrence:

3 Sofia Bohtlingk, 2013. The video has since been shown at various exhibitions at the Sendrós and Arte x Arte galleries and the OSDE Foundation.

4 Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 11 September 2024.

5 César Aira in “Del salto milagroso por el que un ser humano se convierte en artista” [“On the miraculous leap by which a human being becomes an artist”], La Hoja del Rojas [The Rojas Journal], July 1988. Later published in La ola que lee [The Wave That Reads], Buenos Aires, Random House, 2021. Copi (Raúl Natalio Roque Damonte, Buenos Aires, 1939-Paris, 1987) was an Argentine satirical comic strip author and writer of the absurd who lived most of his life in France and wrote his literary works both in French and Spanish.

(…) with children, it is not that they know how to draw, but that they know what they want to draw. For example, they want to draw a spaceship with a computer that’s unsynchronised because of the laser beam shot by a magnetic King Kong aboard a pirate ship that is under attack by a panda shark with two nephews, one good and one evil. Since they don’t know how to draw, they can do it. Children, like accomplished artists, are filled with positive, free will. It isn’t omnipotence, it is reality, plain and simple: life accepted as a becoming. (…)

Perhaps, Aira wrote this while thinking about this series of drawings by Sofia Bohtlingk that she had yet to produce. It is no coincidence, then, that this same concept of ‘becoming’ later appears in the transcript of a conversation between Ana Vofelgang and Bohtlingk.

9 November 2020

I wake up, turn on my mobile. I have an audio from Sofia: “You know, the other day I remembered a word you once used to describe my painting... Ugh! I don’t want to be so self-referential, like me, me, me, me... Sorry... But it’s about the text and the chat we had the other day. I remembered this word that I loved, which is: ‘becoming’. Well, that’s all. Kisses”.

I look at a painting by Sofia that hangs on the wall opposite my bed. It is a canvas of blue brushstrokes with an inscription that pierces through them, like a wound. Becoming, like teaching, is also a state of being. That painting is her: subject, object, substance, thing.

Will Sofia listen again to her own messages?

Sofia Bohtlingk via WhatsApp, 21/11/24, 09:41

I produced a text with Julieta García Vázquez about some paintings that don’t exist but you can easily describe them, it´s as if you could imagine them. It is a project called Amor mía [My love]. They are paintings that are read and don’t exist and... When I was at school in fourth grade, something happened, kind of like when you say, “Oh, so this is what painting is?” One morning I was standing in a queue for the raising of the flag or something like that, and something was happening with the clouds. My school overlooked the Reconquista River and everything looked silver. It was like half dawn, and the rays of sunlight were breaking through the clouds. I painted it in art class and was struck by the idea that something could be seen and then drawn. It was such a strong sensation to become aware of that. That drawing, I´m sure, has a lot to do with the

colours I use now. The blacks, greys and stripes. It’s something to do with romanticism, I guess. Well, you know.

But she is the only one who knows about the rays of the sun filtering through the clouds, turning the Reconquista silver. And she is the one who tells me about a figure who influenced this series of works: the Peruvian choreographer, composer and designer Victoria Santa Cruz (1922-2022), who impressed Bohtlingk to the core when she said, “Rhythm is the best order”. And so, the artist became an emotional athlete6 – the Vitruvian girl who “pinta el largo de sus brazos en cemento” (paints the length of her arms in cement”)7 –channelling everything that overflowed from her into these series that have yet to be fully identified. The period in which these drawings were produced imbues them with an inescapable historical weight. Sofia’s works were created during the pre- to post-pandemic timeframe, when our fragility was exposed on an unprecedented global scale, so that the bodies in her works appear asymmetrical or feature unusual limbs, and with theirvisual genetics that could be traced back to neo-figurative bestiaries or Art Brut.

The difference is that, in these works by Sofia, the challenge of finding an indistinct language that lies somewhere between figuration, abstraction, or stain has already been overcome. In these drawings, a different dilemma is faced: it is as if, having lived past the virus, the human figure were yet to be reshaped, and she as an artist were responsible for capturing that long-awaited return to ‘normality’.

There also appear to be references to the debates that arose with the emergence of COVID-19 regarding the limits of science, as seen in the artist’s use of soft grids – where the geometric precision wavers – and mingling lines that allude to the design of a quivering laboratory instrument, informed by an indeterminate signal. Faced with the unknown, the artist’s intuition ultimately supplants the certainties of scientific instruments, raising questions rather than providing answers. And thus, in her frenetic quest to find the void in these works, Sofia Bohtlingk bears witness to the shaping of a world that has never been the same again.

6 A concept outlined by Antonin Artaud for his programme on the Theatre of Cruelty.

7 The phrase “te sigo desde Cemento” (“I’ve been following you since Cement”) takes on a different meaning, since in Buenos Aires slang it refers to Cemento, the club where many artists first started out. When applied to Bohtlingk, it becomes an unavoidable reference to her performative exercise of painting and her use of a material that puts her muscles to the test.

THEY SHOUTED ‘BLONDIE’ AT ME

By JUAN TESSI

I f you weren’t familiar with Sofia Bohtlingk and all you had for reference was her Nordic appearance and a quick glimpse of her work, you might assume that she is one of those artists who has adopted the icy distance and draconian discipline of a conceptual painter. But a careful look at her body of work will reveal that this prejudice arises from the way painting is often dressed up as an action that is subject to some kind of thought. This is problematic because, as a subgenre, it suggests the possibility of a type of painting that is devoid of reasoning. Perhaps it is just a way of making it clear that more thought went into it than what was

‘Set ablaze by a divine spark, enthusiasts spread the fire across ages, cultures and religions,’ says the Dutch critic Jan Verwoert in his short essay on enthusiasm, love and mania.1 Quoting the lyrics to ‘Rhythm Is a Dancer’, a song released by German Eurodance group SNAP! in 1989, he asks, ‘What’s the act when rhythm is a dancer?’ While on an elliptical, trying to keep up with the beat of Lali Espósito’s ‘Motiveishon’ blaring out of the speakers at the gym, I started to think about Bohtlingk’s show El ritmo es el mejor orden [Rhythm is the Best Order], which opened recently at the Museo Moderno.

At first, though not quite from the start, she moved the oils across her canvases – so large that only a someone of her stature could tackle them – from side to side, creating a rhythm in which her own body

1 Jan Verwoert, ‘Enthusiasm, Love and Mania’, in Frieze, No. 200, January–February 2019. actually painted. Or that the amount of thought extended to the idea of painting in the form of a vector project. But there is nothing programmatic about Bohtlingk’s painting, and her ideas do not contradict the discursive linearity associated with the genre. More than a conceptual artist, she is possessed by her materials and is, in fact, an admirable enthusiast.

became the baton. With her preference for linseed oil and the colour blue – becoming an ever deeper shade over time – her brushstrokes zigzagged gracefully, or simply rose and fell, interrupted from time to time by bursts of abandon (Te dominaré lentamente [ I Will Master You Slowly ], 2012 / Una persona seria [ A Serious Person ], 2013). However, this methodical and repetitive gesture never stood still, and the artist soon became distracted by the possibilities of new materials.

Painting has responded to a changing world ever since its inception. From the rough stone walls of a cave, it moved to papyrus. Then, with fresco, it shifted to the wall, and with oil paint, to wood, until it finally settled on the canvas. From its origins and up to the interwar period, the technological history of the medium has involved an ongoing search for stable materials and surfaces. Or at least that is how it is explained in the 1967 documentary produced by the Shell corporation, La historia de la pintura [The History of Painting], which illustrates the concept by showing the chassis of a car held aloft by a mechanical arm and then dipped into a giant pan of red paint: the new 20th century Fordist method of painting.

Elsewhere, Douglas Crimp, in his seminal text ‘The End of Painting’, 2 suggests that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was the first to note that the French, at the end of the 1700s, had begun to carry off the works created in situ in Italy back to their own country. In a way, they foreshadowed that artistic entity that emerged in Paris a hundred years later, today understood as modernism.

It is true there is nothing quite like destabilising the surface to avoid being relegated to the until very recently denigrated category of easel painter. And it is also true that respect for the stability of materials serves the market more than experimentation. Something of this and of moving walls from one side to the other can be seen in the artist’s 2017 show Espada [Sword], at the Nora Fisch Gallery. Distracted by cement and a broken hollow brick, Bohtlingk traded her brushes for a grinder and threw herself into making a 200-kilogram painting/wall – Pared [Wall], 2017 – and a set of enigmatic sculptures/offerings that were created using all sorts of rudimentarily bound and discarded items: broken plates, oil-soaked balls of painter’s tape, strands of hair, etc. There is no doubt that Sofia’s productions overflow with unlikely occurrences, impulsive

2 Douglas Crimp, ‘The End of Painting’, in October, No. 16, ‘Art World Follies’, Spring 1981, pp. 69-86.

actions, and an unusual capacity to marvel at the things around her.

But this time, the group of drawings shown in the first floor corridor that leads to the museum’s Gallery F exhibition space – works that until now had only been seen in a disperse and intermittent manner – create a new order of rhythms that could already be sensed in Mamá robot [Robot Mum] (2022), the painting that had its back turned to the viewer as they entered her 2023 exhibition Ilusión y bochorno [Illusion and Embarassment]. The work of that period suggested, modestly, a spatiality reminiscent of her earlier cosmic/heavy metal landscapes. But in this case, her use of line betrays a source, not a sketch, but an origin: undoubtedly, a drawing. I can’t recall who it was, but when speaking about painting, someone said that if the surface is public, the depths are private. And whereas in this show, you are now welcomed by a wall featuring one of her concrete paintings (Invisible, 2015) – pure surface – it has to be said that the drawings, produced between 2019 and 2024, are an abyss from which you have no wish to escape.

Curated by Victoria Noorthoorn, the delicate papers form an intimate show that provides room for both figurative and abstract elements. While