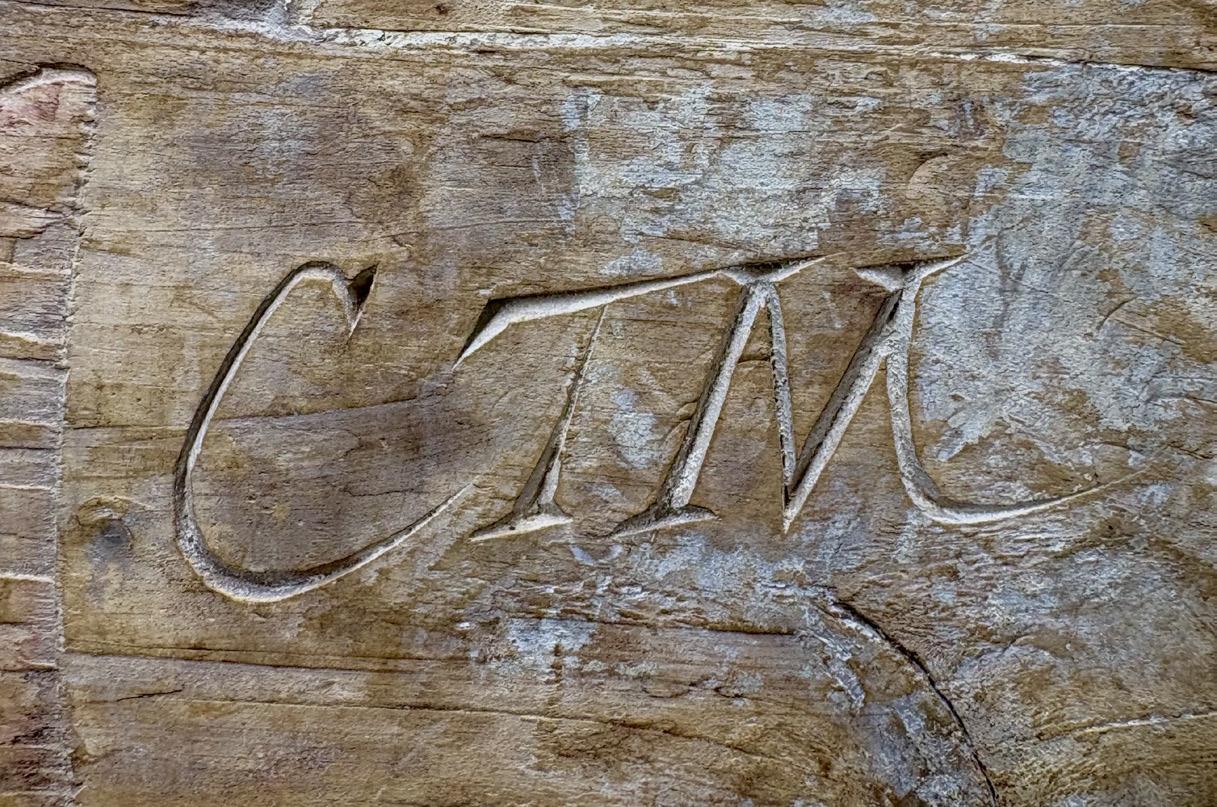

Cameron T. McIntyre

Cameron T. McIntyre

Exhibition

November 21 - December 6, 2025

Guyette & Deeter Gallery

Auction

November 21 - December 6 : lots to begin closing at 7pm est

Please join us for an evening with the McIntyre family. December 6, 5pm. Cocktails and appetizers to be served. Please RSVP by Wednesday, December 3.

Items will be auctioned at bid.guyetteanddeeter.com and our online bidding app.

Guyette & Deeter Gallery

410-745-0485

1210 S. Tablot St, Unit A St. Michaels, Maryland 21663

Artist Cameron McIntyre’s work has always struck me as gifted, thoughtful, and well-representative of the natural beauty that surrounds us. He and I have been contemplating an exhibition and sale together for years, with the hopes of giving decoy and fine art appreciators a chance to experience his work first-hand. I knew immediately that he was going to pour his heart into the work. Creating a catalog, organizing the event, and preparing for the sale of his art—all on top of our busy auction schedule—was no small undertaking, but when you have an opportunity to produce an exhibition by an artist like Cameron, you know it will be well worth it.

Throughout the year, I could sense the intensity of his effort. Every time we spoke, he was working as hard as ever, spending every day in his shop. I had a feeling it was going to come together beautifully. That sense was reinforced as collectors and friends from around the country began calling Guyette and Deeter with questions about the show and expressing their excitement. “Portrait of a Farm” had momentum before we were even able to advertise it.

My connection to Cameron goes beyond art. He and I built a friendship around shared experiences—raising our boys, watching them grow into hunters and fishermen, and appreciating the gifts of nature along the way. That bond has deepened my understanding of his work. His paintings and carvings are not simply representations of landscapes or waterfowl; they are an extension of a life lived close to the land and the water, of mornings in the marsh, of seasons marked by migration and harvest.

The Eastern Shore of Virginia is central to Cameron’s story, and this exhibition reflects the deep roots he has planted there. Two decades ago, he and his wife Adele purchased a farm—a place that embodies everything he dreamed of as a boy: marshes, fields, and flocks of waterfowl filling the skies. That farm is not just where his family lives; it is the wellspring of his creativity.

“Portrait of a Farm” is the culmination of a year’s worth of work, but in truth, the exhibition represents much more than that. This portfolio is the expression of decades of carving, painting, observing, and living in sync with the land. Each piece in the show carries the quiet weight of place and memory. It is art that reaches beyond simple depiction, striving instead to distill essence—to interpret, rather than record. It has been an honor for me, both personally and professionally, to help bring this exhibition to life at Guyette & Deeter. I am proud to share Cameron’s vision with the collectors, sportsmen, and friends who will gather here. His work reminds us of the way an artist’s devotion and observant eye can turn a farm into a portrait of life itself.

- Jon Deeter

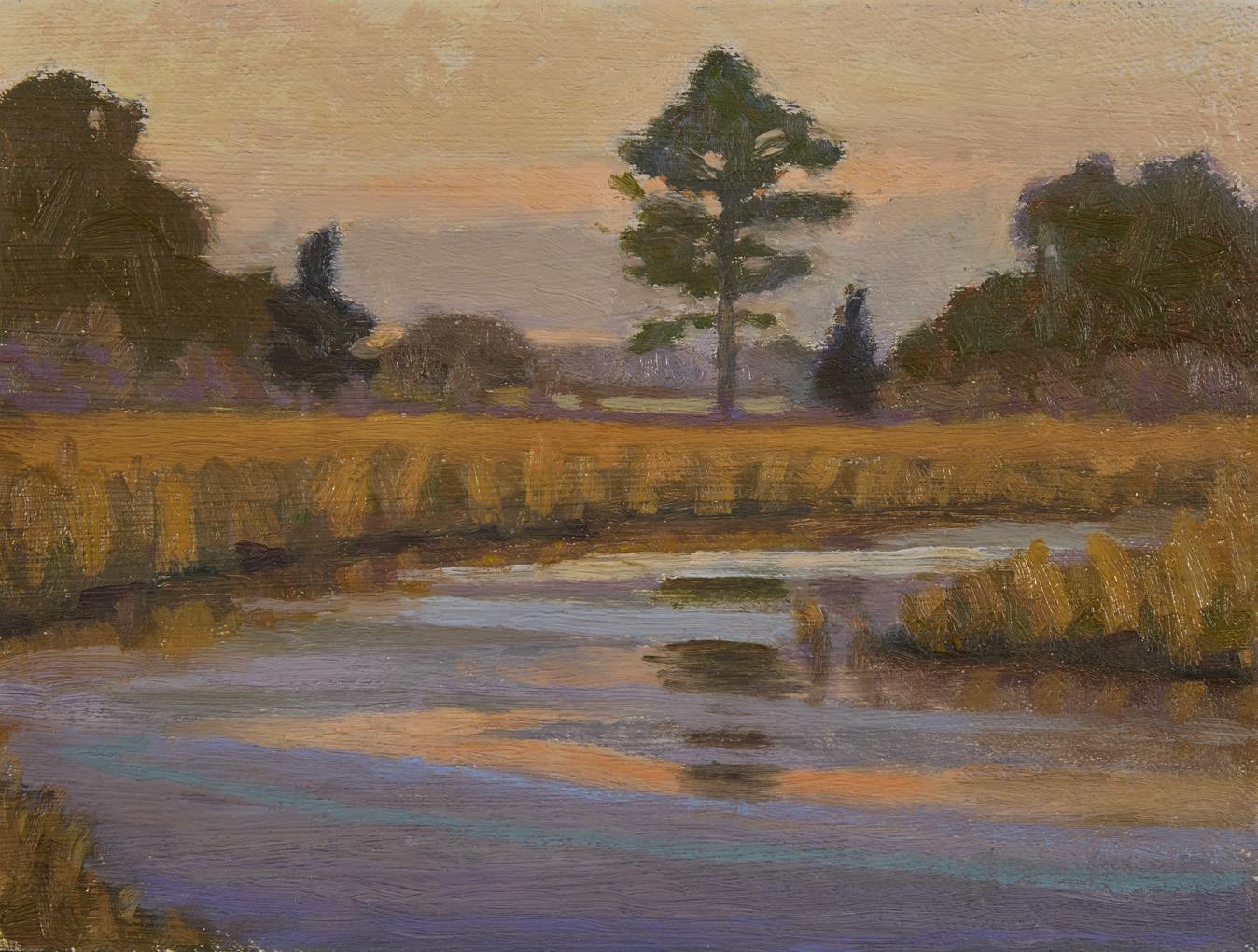

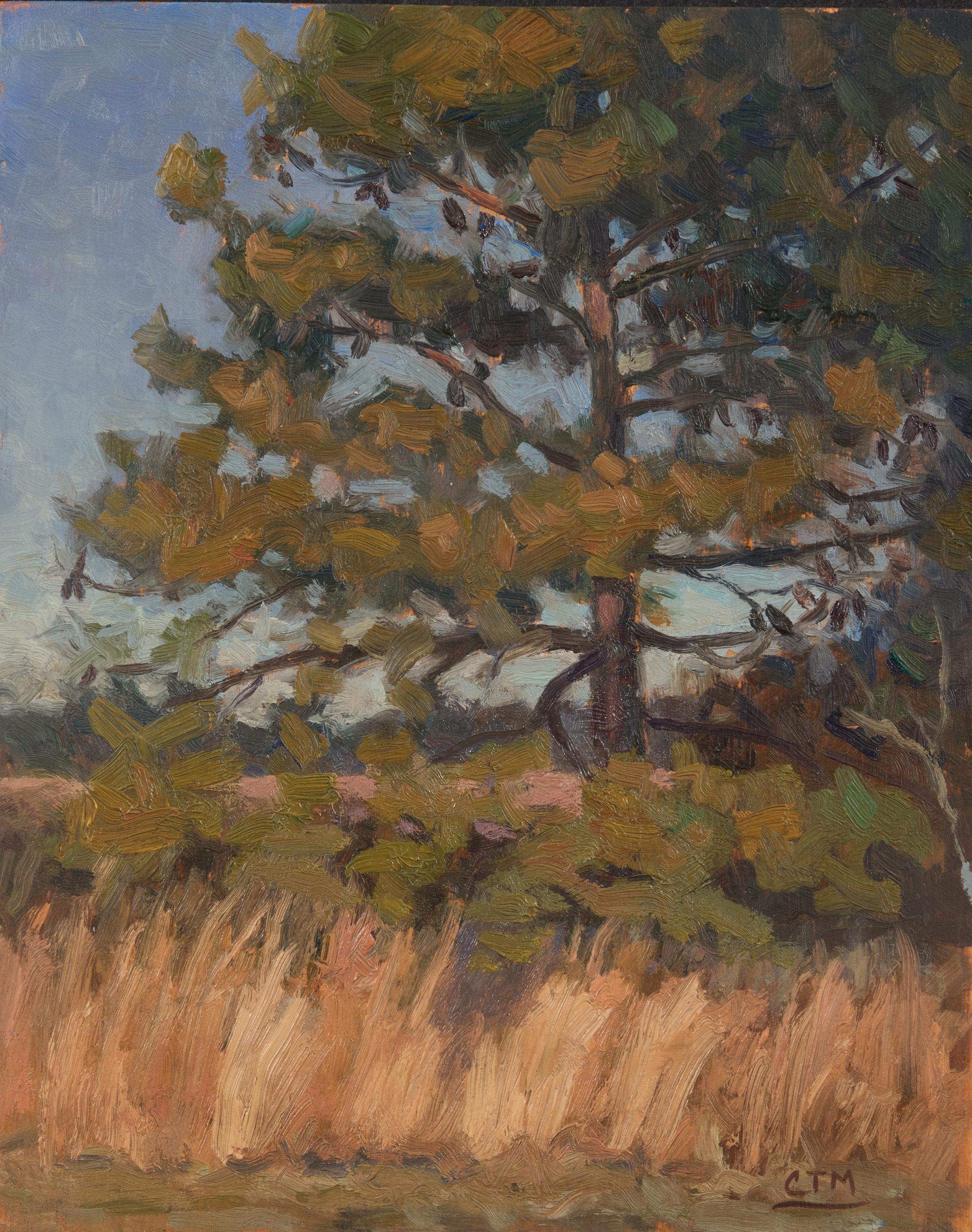

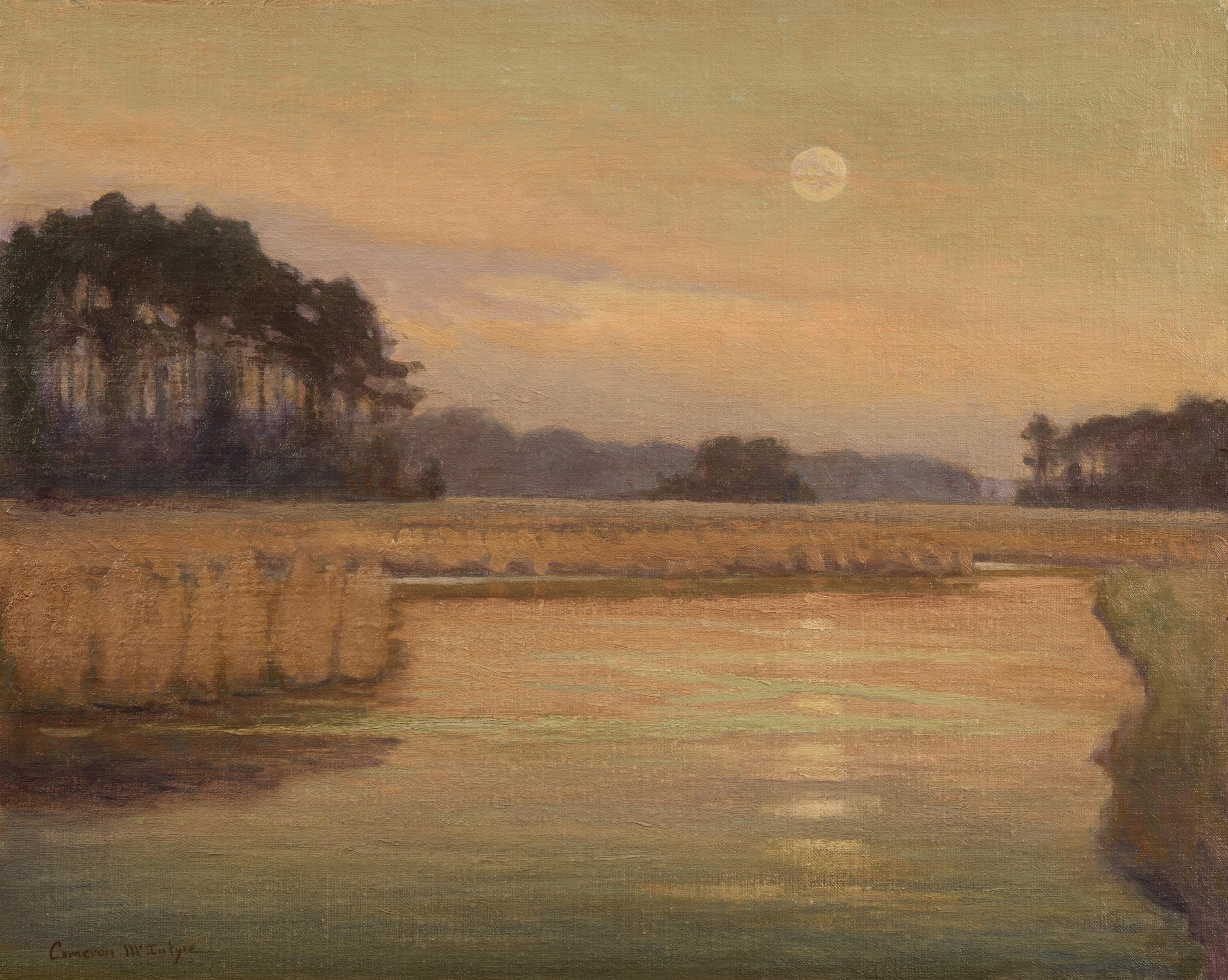

Fundamentally, Cameron McIntyre’s paintings are delicate studies of light and time. The artist paints and carves in a way only someone who has been deeply changed by the Chesapeake Bay can: each piece is simultaneously of the moment in which the artist encountered a scene, but also of the millennia it took to form the beautiful, languid natural forms around us. Activated by light filtering through the clouds, tree lines, marshes, and the like, the beautiful shadows of his paintings tell both the story of the landscape and of McIntyre’s life. The paintings consistently yield delightful complexity in the landscapes. While some scenes center a single element of the landscape as a photograph would, such as the road leading out from his farm in Leaving Home and the towering yet lonely cedar tree in Russ’ Cedar, his painterly haziness transforms the paintings into spiritual experiences.

In depicting the essence of our unique landscape, immersion and understanding is key. What sets McIntyre apart from the many accomplished Plein Air artists who explore this area in their work is that he lives in the land, in a farmhouse that overlooks the characteristic expanses of this region and cycles through the colors and crops of the seasons. This allows McIntyre an appreciation of the quotidian and not just the dramatic. The painter notes that he only paints when “the memory of a scene will not leave his mind”. In miles and miles of memorable scenes, his appreciations and curiosities are as artistic as they are knowing: in the unassuming, undramatic flatness of the Chesapeake, McIntyre always finds beauty and grace, without the help of constant catharsis. Lingering Snow is a great example: the snow itself lies quietly in a small stretch in the middle of the painting, its approaching fate contributing a cinematic quality to the scene. With McIntyre’s guidance and virtuosity, the viewer is transported to simple but fundamental experiences, such as observing a small pile of snow get smaller as the day warms; walking through tall grass towards a marsh; hearing a dog run through the trees; wind changing direction; the full moon peeking through shifting clouds. These are moments for a person to take a breath and think, this must be what it means to live.

Plein Air painters traditionally paint with portable equipment, preferably those that can fit in the trunk of a car, and seek scenes that feel worthy of more than a few hours of their attention. Originally considered a preparatory form of exploration rather than a genre of painting, Plein Air came to be its own discipline

with the Impressionists, who pushed back against the conservative formality of academic painting. The Chesapeake Bay is full of rewarding vantage points for painters seeking such freedom, but also a challenge: painting in “open air,” as plein air is often translated, needs sharp artistic skills, virtuosity, and a resistance to the elements - just ask anyone who has competed in Plein Air Easton in one hundred degrees in mid-July. As freeing as it is to come up on a landscape and think, this must be the place , rendering the scene artistically and not with the exacting interests of a cartographer or a naturalist is key. McIntyre’s Plein Air practice is unique because of his quietly-animated scenes, which effortlessly surpasses expository reporting: his artistry allows you to understand that something has just happened, or is about to happen, to the light, the reflections, or the flora and fauna. And crucially, McIntyre is simultaneously a student and a master of color: gamut is so central to his practice that rather than rely solely on photographs of a scene, he creates field studies that are high-fidelity and recreates them faithfully in the studio. His canvases thus seek the re-emergence of an experience through the fundamental elements of artmaking. The paintings in this exhibition chart a full changing of the seasons through color, intimated not just through subject matter but through thoughtful titling. The transitions and dynamic and varied brushstrokes – especially on the artist’s horizon lines - present subtle yet powerful explorations of a scenic world. The viewer can enjoy the full breadth of his detailed storytelling by coming close and going far.

McIntyre has a loose and atmospheric visual language, although in some paintings he creates beautiful counterpoints to the aforementioned haziness by delineating the edges of his trees, awarding them the focus of a main subject. This is indexical to his love of the land: a wanderer might take in a landscape as a beautiful whole, while McIntyre knows his deeply-rooted subjects and individuates them effortlessly. His water scenes also communicate the experience of someone who has been in the marshes for a long time – Bayside Serenade , one of the larger paintings in this catalogue, pays close attention to the unity and variety of this fast-changing landscape, as the viewer looks down on it at scale. As the seasons change and water lines move, the unique shapes and forms the Chesapeake Bay sing through McIntyre’s expert hand.

Living on a farm yields a matchless kind of constant change. Nature moves in cycles, mirroring some of the most fundamental experiences of a person’s life. McIntyre pays special attention to these changing elements in his paintings and opens doors for viewers to make personal connections with the land by noticing the beautiful details he has subtly included. In many ways, it is not necessarily the awareness that a landscape will change with the seasons that makes his paintings so emotionally influential – it is that the viewer too is changing, made aware or passing time through a delicate crescent moon, the reflection of a flaming sunrise, or a passing cloud in the center of his paintings.

McIntyre’s practice as a decoy carver offers the same kind of meditative respect to his subjects as his paintings: there is quiet delight in how his waterfowl are animated in beautifully and faithfully-determined poses and paint patterns. The dynamism of some of the artist’s choices are especially striking: the ubiquitous Canada goose’s neck, for instance, is observed in an elegant curve that contrasts beautifully with the subtle detailing of its plumage, while Barn Find Goose is carved in high, forward momentum.

The artist offers different approaches to decoy anatomy through his outlines: his Pinch Breast Pintail pair , inspired by the Ward brothers, have flowing lines and the delicate, meticulous, and in places, stippled painting pattern that is well-known to decoy lovers, while his high-contrast Upper Bay Canvasback pair demonstrate head styles with sharper angles and heavy, colorblocked patterns that offer subtle yet compelling rendering, almost at the edge of abstraction. Feeding Brant is just as delicate, as the slight turn of the bird’s head contributes storytelling and reflects McIntyre’s careful observations of his subjects. The piece that ties the different aspects of the artist’s practice, however, is Black duck still life (two drakes) , where McIntyre is able to demonstrate the full virtuosity of his practice. The two life-size subjects hang beautifully, their

wings opening up to gravity in a lifelike and majestic manner. The artist’s detailed and careful choices, such as the use of string and the birds’ delicate and realistically-painted feet, straddle the worlds of painting and hunting. The fresh kill, once obtained, becomes the honored subject of a still life.

McIntyre isn’t merely interested in exposing these moments of change in his paintings and decoys; he finds abstraction in the repeating and changing forms in his landscapes. Such profound observation and creative effort are what yields his authenticity as a painter and a carver. An artist who isn’t necessarily interested in the demands of the art market, McIntyre has found a place for himself as a storyteller and as a maker who is dedicated to delivering a certain type of truth rather than mere visual stimulation, although that all his paintings are focused on the sublime does not hurt. Living most of his life on the Eastern Shore, raising his family here, and making his respect and awe of the land central to his artistic practice, McIntyre delivers lessons for anyone in search of meaning, but especially those who hear themselves whisper “Wow” as they take in our shared landscape. His farm and his relationship to the land are patient subjects, and his paintings and decoys grateful and observant devotions - hence the exhibition’s unassuming but meaningful title, Portrait of a Farm.

- Mehves Lelic, Assistant Professor and Mosely Gallery Director, Department of Fine Arts, University of Maryland Eastern Shore

Oil on hand planed cedar panel

9 1 / 2 ” x 10 3 / 4 ”

Two drakes

White pine / oil

Lifesize

Oil on linen on board

White pine / oil

Framed dimensions 26 1 / 2 ” x 20 1 / 2 ”

Late October

Oil on board 12” x 9”

March

Oil on board 12” x 9”

White cedar / bronze feet

Life sized

I first came to the Eastern Shore on a duck and goose hunting trip when I was about eleven years old. First to Cambridge, Md, and then to Assawoman island, Va. I knew from that early visit that I would someday call the Eastern Shore my home. I also knew from about the fourth grade that I would eventually have a farm of my own - hopefully one with marshland and ducks - lots of them.

In August of 1989, at age twenty, I said goodbye to my home in Beaufort, SC. And moved to the Eastern Shore of Virginia, where I knew about two people. It was truly a sink or swim endeavor, following a crazy dream to try and become a painter and decoy maker. I had little skill, no reputation, and virtually no money. Two traits I did possess in quantity, desire and emotion, got me through the first decade or so. In retrospect, those were the two most important qualities to be blessed with. I worked at the decoys - seemingly every day unless I was out hunting in the marshes- and painted every chance I got. My carving skill improved steadily, while the painting gave me problems, but oh how I tried.

I am getting a bit ahead of myself. I had an obsession with art and drawing from an early age and my mother found a lady in town to give me drawing lessons in about the fifth grade. I began carving decoys in my early teens and steadily and seriously worked at them all through high school. Afterwards I studied art at the University of South Carolina for two years, before leaving to study art and especially painting at the Gibbes Museum in Charleston with the painter William McCullough. Bill and I became fast friends- he even invited me to live part time with him and his family and gave lots of after class instruction. We were painting and drawing from a live model in the museum class, but painting landscapes after class and on weekends. That was my true love and it showed. At that time I subscribed to the magazine “Antiques” and was often

fascinated by the treasures within. I remember showing Bill paintings that I saw in the magazine that I felt some sort of connection with; paintings by Bruce Crane, George Inness, Ralph Blakelock, Albert Ryder and even Millet. He would always say the same thing: “Too dark“. Almost forty years later, I realize that those artists and a host of others in the same vein, were the foundation for my journey and my sensibilities have always led me back to the daybreaks, evenings, and moonlights.

Now about the farm. In 1997 my wife of two years, Adele, and I got the idea that since she held a steady job and I was beginning to sell everything I could make, that the time had come to look for that farm I had always dreamed of.

The one I had my eyes on wasn’t for sale and in fact, I didn’t even know the owner, or how much land it included. It was a place I had passed by for several years on my way to go duck hunting and always appealed to me; lots of marsh, a beautiful creekfront field and big, open horizons. I figured some ducks might call it home also, but wasn’t sure. A trip down to the courthouse gave me the names of the owners, two brothers who farmed much of the land in the whole area. The farm was deemed to have a couple hundred acres , and an assessed value was also provided. My hopes were running high. The assessment seemed like something we may be able to swing if we really buckled down hard.

A call was made to the farmers and a meeting planned. They explained that they didn’t sell land, they usually bought any farmland that came up for sale, but they might consider it.

The day we met will be forever etched in my mind. It was a cold, partly cloudy day in early February. I made my way over to the place and they were waiting at a little pull in on the field edge. Pleasantries were exchanged and they got right down to business, explaining how there wasn’t any more land being made and how this was waterfront, had good tillable soil and that if I liked ducks, this was the place.

Just then a very unusual thing happened. The temperature seemed to drop about fifteen degrees, it got very dark and very windy. Then it began to snow and ducks started flying in from every direction; mallards, black ducks, and I even thought I saw some pintails. Next, flocks of geese started pitching into the field in front of the trucks. I am not making this up. The farmers knew this was the moment to spit out the price and when they said they wanted about five times the appraised value for HALF the farm, I just about fell over, but was brought back to reality by the sound of all those geese.

A miracle known as owner financing ended up being the key to our dream. We bought half the farm, the brothers financed it for us and the rest is history. We moved an 18th century house there a few years later and eventually bought more of the land and marsh. The farmers became friends and even became my customers. To this day it is the only land they have ever sold.

Not long after we moved here, I suddenly felt an overwhelming urge to paint this land I felt so fortunate to own. I would walk all around the farm at all hours of the day and night in any kind of weather, in every season, although winter was by far my favorite. Things began to dawn on me. I started to see ways I might interpret the land through my paintings. A studio and workshop was built and I got to work. Eventually I paid for a large portion of the farm by painting pictures of it. Having always been a regionalist, and having taken heed from the painter and author John F Carlson who cautioned against being a “tourist painter”, nearly every painting I’ve made has been within a few miles of home. A very few have been painted from my memory of a distant place that had special meaning. For about the past decade I have focused entirely on the farm where I live, honing in on the intimate places I know so well- painting dozens upon dozens of paintings right out the front door and I’m positive I have barely scratched the surface.

In the end, I want my paintings to be everything that a photograph is not. I am after an interpretation not a snapshot. I often spend months and sometimes even years, adding forms, subtracting forms, striving for a texture and surface quality that a photograph could never achieve. A search for my own reality. A pairing down to a few simple shapes arrived at by a long and mysterious process that I don’t fully understand is usually how the paintings evolve. It is much the same with the decoys and carvings. They all start with an idea that becomes a sketch. The sketch is redrawn, refined. Then the process of how to really capture the essence of the drawing in wood begins. I honestly miss the mark more often than I should at this point, but that helps to keep me going, urging me to get it better next time. However, I always give each piece all of my undivided attention until I feel it is time to let it go. I continue to be amazed at the endless possibilities, knowing one could never reach the end.

In this show, my “Portrait of a Farm” are some of the results of my efforts. Each species of bird in the show, from mourning doves, to canvasbacks, to tundra swans, have all visited the farm. I have found huge whelk shells in the oyster midden piles on the edges of the creek and each painting is a scene from here at Marsh Haven Farm. A farm inhabited for thousands of years by native Americans, a farm once sighted and explored by Captain John Smith and two centuries later camped on by a couple hundred civil war soldiers. It is the farm where I raised my family and continue to live out my dream, along the way discovering some of Mother Nature’s deepest secrets.

- Cameron T McIntyre 2025

Study for “Peaceful Waters”

Study for “Western Horizon”

“Cameron McIntyre is without a doubt one of the most talented decoy makers of his generation, and his carvings have a particular appeal to those who collect vintage hunting decoys. As a passionate duck hunter and an enthusiastic collector in his own right, Cameron is well versed in both the functionality of hunting decoys and the artistic appeal of vintage birds. He has an innate ability to borrow from the influences of decoys of an earlier period, freely combining the elements of form and paint from the classic carvers of earlier generations to create a vintage decoy from something that only previously existed in his imagination. And yet he is just as capable of producing a decorative carving that rivals any, using only traditional tools. His approach to decoy making in many ways is both spiritual and romantic, as he has tightly woven his interpretations of contemporary decoys with the traditions and gunning lore of its not-too-distant past, while adding an aesthetic flair that raised them to the level of art”

Joe Engers, 2018 Editor of Decoy Magazine and author of The Great Book of Wildfowl Decoys