ROCKY MOUNTAINS

/

Beyond ordinary.

Ordinary days aren’t measured in miles.

They aren’t improvised at altitude. They don’t begin at first light, lead you above the clouds, and end with dwindling sunlight as you take refuge in the shadows of summits. But then, ordinary days never make great stories.

59.2661° N, 136.4061° W

TABLE of CONTENTS

DEPARTMENTS

P. 8 Editor's Message: Rooted

P. 17 Backyard: Sleeping My Way Through the Backcountry

P. 30 Behind the Photo: Low Burn

P. 46 Mountain Lifer: Chloe Vance

P. 51 Trail Mix

P. 52 Book Reviews

P. 54 Gallery

P. 59 Gear Shed

P. 64 Back Page

FEATURES

P. 10 Blown Away at Castle

P. 24 The Old Ones

P. 34 The Nature of Music

P. 39 Queen Line

ON THIS PAGE

Mike Hall threads a spine in the Alphabet Gullies, Lake Louise Ski Resort. GRAHAM MCKERRELL ON THE COVER A lone tree perseveres in an ever-shifting landscape, Jasper National Park. PAUL ZIZKA

In the spirit of respect and truth, we honour and acknowledge that Mountain Life Rocky Mountains is published in the traditional Treaty 7 Territory which includes the ancestral lands of the Stoney Nakoda First Nations of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Wesley, the Tsuut’ina First Nation, the Blackfoot Confederacy First Nations of Siksika, Kainai and Piikani, and the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3. We acknowledge the past, present and future generations of these Nations who continue to lead us in stewarding this land, as well as honour their knowledge and cultural ties to this place.

PUBLISHERS

Bob Covey bob@mountainlifemedia.ca

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

EDITOR

Erin Moroz erin@mountainlifemedia.ca

CREATIVE & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR, DESIGNER

Amélie Légaré amelie@mountainlifemedia.ca

PHOTO EDITOR

Brooke Riopel brooke@mountainlifemedia.ca

COPY EDITOR

Kristin Schnelten kristin@mountainlifemedia.ca

WEB EDITOR

Ned Morgan ned@mountainlifemedia.ca

SMALL BATCH COFFEE ROASTERY AND CAFE

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, DIGITAL & SOCIAL

Noémie-Capucine Quessy noemie@mountainlifemedia.ca

FINANCIAL CONTROLLER

Krista Currie krista@mountainlifemedia.ca

CONTRIBUTORS

Bob Covey, Ryan Creary, Thomas Garchinski, Blake Gordon, Kevin Hjertaas, Laura Keil, Michael Klekamp, Graeme Kennedy, Dee McLean, Margaret McKeon, Graham McKerrell, Laura Ollerenshaw, Andrew Penner, Sherpas Cinema, Georgi Silckerodt, Laura Szanto, Steve Tersmette, Sabine Tilly, Chloe Vance, Anne Wangler, Meghan J. Ward, Paul Zizka.

SALES & MARKETING

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

Published by Mountain Life Media, Copyright ©2026. All rights reserved. Publications Mail Agreement Number 40026703. Tel: 604 815 1900. To send feedback or for contributors guidelines email kristy@mountainlifemedia.ca. Mountain Life Rocky Mountains is published every October and May and circulated throughout the Rockies from Revelstoke to Calgary and Jasper to Fernie. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Views expressed herein are those of the author exclusively. To learn more about Mountain Life, visit mountainlifemedia.ca. To distribute Mountain Life in your store please email Bob at bob@mountainlifemedia.ca.

From Norway to Bann.

x Shop the new collection

Rooted

There’s a tension in winter. Isolation versus connection. Stillness versus survival.

Winter in Canada demands resilience—physical, emotional, ecological. It asks us to endure the season’s weight. We take our cue from the trees that persist and persevere through storms, frost and freeze-thaw cycles, their roots deep and steady.

But being rooted isn’t the same as being stuck. To be rooted is to be connected. Winter brings out parts of ourselves that often lie dormant the rest of the year. Artistic pursuits, shelved hobbies and back-burnered relationships return.

The season turns us inward, causing reflection. There’s responsibility here: caring for others, showing up for community. Helping people in need is as much a part of the season as snowfall. We’ve learned how to survive here—not just physically, but together.

This winter at Mountain Life Rocky Mountains, we explore what it means to be rooted. From carving turns through dry powder at down-home Castle Mountain Resort to tracing the gnarled limbs of ancient limber pines. We hear trees turned into music. Meet people whose healing work grows from horses, land and connection. And watch from the sidelines, as one of our own chases her homespun dream on Robson’s south face.

Winter is a return to quiet steadfastness rooted in community. Listening, learning and letting the mountains remind us where we belong and why we stay. –Erin

Jasper elk, endurance incarnate. PAUL ZIZKA

Tonje Kvivik Haines, Alaska

Photo: Aaron Blatt

THIS PAGE Coming up for air on Gravenstafel Peak.

RIGHT PAGE, TOP Commuting locals.

RIGHT PAGE, BOTTOM Lift ops on retro day at the T-Rex T-Bar.

Blown Away at Castle Mountain

words :: Steve Tersmette

photos :: Lizzy Reimer

The Butterfly Effect is a pillar of Chaos Theory, a philosophy modernized by mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz, that asks: “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wing in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?”

Off Japan’s east coast, the northbound Kuroshio Current meets the frigid waters of the Oyashio Current and together they begin their long journey eastward. On Gravenstafel Ridge in the Southern Canadian Rockies, a solitary snowflake touches down while a dormant chairlift sways above. On one hand, Lorenz could characterize those two individual events as chaotic, while the actual cause and effect is much simpler. As the two ocean systems join to become the North Pacific Current, they travel toward Canada transporting moistureladen air in its wake. As the current diverges off the coast of British Columbia, that moist air continues inland, forced upward by the

mountain ranges that define the western Canadian landscape. It meets the freezing arctic air parked high above the Rocky Mountains, and lo and behold: snow!

It is this cold, dry snow that first attracted Paul Klaas, a group of skiers with a D-9 bulldozer and a small consortium of investors to a remote valley in the Southern Rockies in 1960.

Castle Mountain Resort’s relatively obscure history is rooted largely on hardship and turmoil dating back to its opening in 1965. The original West Castle Ski Hill featured a classic, Swiss-style chalet and four T-bars, one of which had to be sold just a few years later to pay down debt. The winter of 1975 saw West Castle host the Alberta Winter Games, a competition plagued by heavy snow and even heavier winds. That weather event resulted in an in-bounds avalanche, forcing the hill to close for two days. In January of 1977, the original day lodge burned to the ground—which was the last straw for the original owners. At that point, the Municipal District of Pincher Creek assumed ownership of the ski hill and operated it until 1996 when a group of nearby residents and skiers took over and developed West Castle into what it is today.

BUCKAROO CARPET

Bruised Knees, Big Feelings

My own first taste of Castle came during a snowy stretch of weather over the Christmas holidays in the winter of 1996. I left my skis at home, rented a snowboard and signed up for lessons. While the memories of that week have been relegated to a less useful part of my brain, three things still stand out to this day. The first is how purple and bruised my knees were from the beating they took as I failed to grasp the finer points of snowboarding. The second is how friendly my instructor was and how adept he was at keeping a gang of cocky, wanna-be snowboarders in check. And the third was my deep regret for not bringing the planks to take in three days of blower powder.

BEING THERE

Ski Racer Turned Resort Lifer

Dean Parkinson is the general manager at Castle Mountain Resort. Prior to his current post, he served as the resort’s director of finance. And before that, the president of the racing club. Dean has dedicated most of his adult life to the ski industry and to Castle going back to the early 1980s. He first experienced Castle during the 1982 Alberta Winter Games, competing in downhill skiing and quickly forming friendships with many of the local skiers. Over the next 18 years, he visited the hill only occasionally, but in 2000 and in his own words, he “took his first true sip of the Kool-Aid.” He discovered Castle Mountain was a place where he could ski with his children and enjoy the deep, deep powder in a place where everyone knows your name.

Castle Mountain Resort has undergone significant changes including the opening of new runs and, most recently, the acquisition of the original Angel Express high-speed quad lift from Sunshine Village under Dean’s direction. From the outside looking in, the recent upgrades and expansion may seem to fly in the face of their humble operation, but there is a broad awareness that the business is as important as the people who have supported it for decades. For Castle, creating a memorable experience means leaning into what makes them unique: incredible terrain, deep powder, wide-open runs without the crowds and a genuinely friendly vibe.

Sixty years later and counting, Castle Mountain Resort has almost 100 runs on two mountains. Six lifts access 3,500 skiable acres with an annual snowfall of 8.5 metres. An in-bounds cat skiing program also operates on the hill. However, their winter operations only scratch the surface of what Castle is all about.

STAGE /COACH ZONE

Homegrown and Armpit Deep

In Western Canada, where many ski hills are often an asset contained within a financial portfolio owned by national or multinational corporations, Castle Mountain is continually doubling down on its commitment to its roots. Cole Fawcett is the sales and marketing manager at the resort, a position that not only requires a foot on the gas pedal year round, but also a keen awareness of its loyal, local base. He’s deeply connected to the pulse of the ski industry, helping Castle thrive as an independently owned resort that attracts skiers while staying true to its community.

The snow falls reliably at Castle and the resort has nationwide bragging rights for average accumulation, which certainly makes Cole’s job easier, but weather is a double-edged sword here and presents a litany of operational challenges. For starters: the wind. As Cole says, “If it ain’t snowin’, it’s blowin’.” Southern Alberta is notorious for high winds and Castle Mountain Resort is firmly in the crosshairs. The steep terrain, coupled with avalanche start zones and wind-loading of slopes creates a quagmire of avalanche management conditions to deal with. He credits the team for always managing the challenge safely and creating an operational policy to work with Mother Nature, rather than fight against her. To that point, the wind isn’t all bad. The wind direction is constantly providing a refresh of snow, even if it’s not actually snowing. This is an anomaly the locals have dubbed “windsift,” where snow that has simply been blown around the mountain fills in yesterday’s tracks and still yields fresh turns.

In addition to the weather constantly keeping resort staff on their toes, they also have challenges with aging equipment. The capital cost of replacing machinery, cats and buildings is daunting to any ski resort, let alone an independent one. It’s part of the reason why their existing ski lifts and the new-to-them Stagecoach Express have all been obtained from other resorts and refurbished. At the end of the day, though, while Castle’s business model absolutely must be sustainable, they are not driven by profit. Cole proudly states that every penny made is ultimately returned into the visitor experience. This policy applies to everything from improving snowmaking and grooming, right down to ticketing—anything to make their guests’ days better.

“I’m continually drawn in, not only by the love and support of our incredible community and the great skiing, but by having the privilege to work under and alongside some incredibly smart, talented and hard-working individuals,” says Cole. “What we do here is cherished and what we have here is something truly special.”

Showdown on Sheriff.

Blower on Showdown.

On Chasing Snow and Finding Home

Every year when the lifts at Castle Mountain start turning, Tim Luke locks the door to his home in Muskoka, Ontario, and hops a flight to Calgary. When most snowbirds are looking south to warmer weather and greener pastures, Tim is literally looking for snow. In March of 1987, he got his first taste of Rockies powder at West Castle and has been making the trip to southern Alberta ever since. In 2017, he bought a mobile home on one of the 134 full-time leases near the hill along with a share in Castle Mountain Resort and now serves as the president of the Castle Mountain Community Association.

The reason for his initial Castle excursion was simple: a bluebird day, spring skiing and a welcome distraction from a business trip. The reason for coming back, and ultimately for staying, wasn’t so much the skiing as it was the people. Tim Luke truly loves Castle Mountain. His excitement builds as he talks about the community events his association puts on. But it doesn’t start, or end, with that. “I love the hiking trails. I love the mountains and the nearby wetlands,” he says. “I am passionate about this place.” For Tim, there’s so much more than skiing. It’s the friendly faces and staff at the hill. It is generations of families that have grown up on that mountain, skiing with their kids and now their grandkids. Some of those bright-eyed children from Tim’s early trips to Castle have grown up, bought their own shares at the resort and now have their own cabins and homes on the hill. Some have become employees at the resort, even working into management roles. And some can be found volunteering alongside Tim on the Community Association.

HUCKLEBERRY CHAIR

From Ditching School to Shaping Community

Judy Clark’s long relationship with Castle sounds suspiciously like Tim Luke’s. While she isn’t necessarily racking up the frequent flyer miles that Tim has over the years, her story draws a number of parallels. Her first memory of West Castle was skipping school in the early 1980s to go skiing—an effort that was rewarded by making turns on a rainy day. And that first visit spurred many, many more. She and a small group of friends frequented the ski hill, creating lifelong memories filled with laughter and tired legs. Within a few years, she was living in a travel trailer on the hill. In 1996, when funds were being raised to take over the ski hill from the Municipal District of Pincher Creek, Judy became one of the original shareholders. She also took out a 20-year lease on a parcel where her cabin sits today.

For 40 years Judy has lived and breathed Castle Mountain Resort. She’s been there through multiple ownership changes and the growth and expansion of the resort as well as the lean years where the dry Southern Alberta snow refused to fall. Through it all, the support of her community has never wavered. She’s watched as families, guests and staff return year after year, most notably a friendly ticket checker whose reputation reaches far and wide. “You’ve heard of Huggy Lady, right?” she asks. “She’ll check your ticket and give you a big hug. If she really likes you, she’ll give you one of her pins.”

For Judy Clark, everything that is good about Castle is personified by the hugging ticket lady. Judy’s metaphorical embrace for her home hill is downright contagious and, although some days she’d like to keep it the best kept secret around, she also knows that an experience like this is meant to be shared—an experience 60 years in the making, that started with the flap of butterfly wings half a world away.

Ol’ school vibes on the Tamarack chair.

Members of Castle’s pro patrol.

A ski guide’s long slide from luxury lodging to increasingly questionable sleeping arrangements.

words :: Kevin Hjertaas

Mike has never been particularly good at ski guiding. But he’s also never been very picky—and has always been broke—so over the years he’s worked at a wide variety of backcountry operations. And he’s seen a shocking array of staff quarters. Now a grumpy old guide, he looks back on his career as a steady descent of living arrangements.

Mike’s first full-time guiding gig was with Canadian Mountain Holidays, commonly shortened to CMH, and then affectionately expanded to Cheese & Meat Holidays. It’s one of the few places a guide can work in the backcountry for a year and gain weight.

There’s a reason skiers call it a heli-belly, and it has less to do with the helicopter’s help and more to do with the gluttonous amounts of fine food offered to you throughout the day. For a poor young ski guide, living at a CMH lodge was a revelation. Beyond the food and endless powder, Mike also grew accustomed to the spacious, comfortable private room, cleaned by someone else. His only previous experience had been as a practicum tail guide at a ski touring lodge called Blanket Glacier Chalet. Blanket was nothing like CMH, and not just because you had to walk uphill.

The first day at a remote hut is always hectic: a blur of new guests, luggage, food and logistics as you rush out the door to

cram in some skiing before dark. By the time Mike lugged his own bags up to bed on that first night at Blanket, it was dark. The cook and custodian were already asleep, so he crept up the ladder into the communal staff loft and silently searched for a place to lay his head.

The main chalet had been modernized, but the staff quarters remained a collection of six single mattresses in a loft above the sauna. The roof was slanted, and Mike’s head smacked it immediately. His eyes slowly adjusted, and he took in the scene: Curtains hung everywhere, like a bazaar or Persian market, in an attempt to create privacy for an unknown number of people. He listened, trying to decipher which curtains had

Salvation. The sauna at the Golden Alpine Holidays' (GAH) Sentry Lodge. ANNE WRANGLER

someone sleeping behind them and which might have a vacant bed. After standing there like an idiot for a time, he pulled back the curtain on his left, whispering, “Oops. Sorry!” A sleepy guide squinted up at him, then thrust a pointed finger at the bunk furthest from the lone window.

Mike found a rhythm as the days went on, and he came to understand why clients are so dedicated to skiing at The Blanket. He particularly loved the morning commute—simply descend the ladder into the tiny guide’s office for the 6 a.m. meeting. Unfortunately, coffee is over in the main lodge, and if there is new snow (there’s always new snow at The Blanket), you need

to shovel your way to and from. On the bright side, if you are shovelling, it means there’s fresh powder and you’ll soon be skiing it. Combine the shovelling with trailbreaking all day, and you’ll be tired enough to sleep anywhere.

Lucky for Mike, sleep has never been a problem. His ability to drift off anywhere is his superpower. That, and his total lack of self-awareness. On his third day at The Blanket, he mentioned how well he’d been sleeping and added how happy he was that no one snored. The big table fell dead silent. The staff put down their forks and stared at him with bloodshot eyes. Mike, engrossed in his pancakes, was oblivious to the tension.

This is a good time to remind anyone going on a backcountry trip to always, always, pack earplugs. Mike learned that lesson himself, like so many before him, at an Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) hut. The Blanket may be rustic in some ways, but its kitchen and guest rooms are nicely upgraded, and the sauna provides a relaxing end to the day and a warm shower always follows. The ACC’s Bow Hut, on the Wapta Icefields, offers no such luxury.

Combine the shovelling with trail-breaking all day, and you’ll be tired enough to sleep anywhere.

At Bow Hut, Mike slept with a small community of 30 exhausted, unclean strangers. The bunks each sleep five or more, shoulder to shoulder, on thin, durable mats. Roll either direction and you’re close enough to kiss your neighbour. You’re guaranteed most of them will be bumbling to the outhouse all night, too.

When he couldn’t sleep, Mike lay awake, silently watching uncomfortable people with tight hips and skied-out legs try to extricate themselves from sleeping bags and crawl on all fours around other sleepers. One by one, they would find hilarious choreographies to make their way to, then down, the ladder. He watched one middle-aged man, who’d probably never done yoga in his life, silently invent the oddest contortions to progress around the other sleepers. Then, with a twitch and a short squeal, his hamstring spasmed and he toppled onto a young woman who woke in a thrashing panic. Mike lay there shaking his head, thinking about colleagues who’d taken work in the remote North, where they made considerably more money and didn’t have to sleep with anyone they didn’t want to. Mike dreamed of that gold-level luxury.

ABOVE Sunrise Lodge. ANNE WRANGLER. RIGHT PAGE Adam McCraw, Lake Louise backcountry. GRAHAM MCKERRELL.

It was an almost fabled land, something only whispered about in tight quarters: In northern BC, 300 kilometres from nowhere, sits a gold mine surrounded by glaciers. It’s an audacious place to build a small village of portables, but that’s what gold money can do. Up there, avalanche safety workers have private rooms with their own bathroom and shower, like Mike had at CMH. And, like at CMH, there’s a gym (because honestly, you don’t work that hard heli-skiing). But the gold mine also provides a music room equipped with guitars, drums, microphones, a bass guitar and a keyboard. Though he has no musical talent, Mike lay in the sardinepacked bunk, dreaming of working at the mine, recording an album throughout the winter. It might be a darker album, as half of the shifts at the mine happen at night. And during the dead of winter, you can work an 82-hour week without ever seeing the sun breach the horizon.

In hindsight, Mike realizes he had it good that first year at CMH. Instead of working alone and living amongst the unshowered masses at Bow Hut, he could be back in comfort with a bartender who knows his order, an on-call massage therapist and a patisserie chef who made his favourite cookies for him. Heck, the maintenance staff even did all the shovelling around the lodge. Mike’s biggest challenge at CMH had been after his pre-dinner nap, when he would have to pull himself out from under

his down duvet and put on a collared shirt. Mike had soon learned to enjoy a sauna or hot tub instead of a nap. Then he would arrive at dinner just as fresh as if he were on vacation. That is, if he could have afforded to vacation in a place with pitchers of cucumber water in every room, white robes with matching slippers and a wine cellar bigger than the van he lived in.

But, instead of returning to heli-skiing after the Bow Hut, Mike decided to try a more rootsy ski experience. Golden Alpine Holidays (GAH) was hiring, and Mike was broke (again), so he signed up to work at their four remote lodges. His first lesson at GAH came from the crusty old lead guide Isaac Kamink, who would tell everyone, “If you’re not doing anything, you’re doing something wrong!” This came as a shock to Mike. He wasn’t being lazy per se; he was just waiting for his cappuccino to arrive. He never complained that his empty beer can hadn’t been taken away, but he was surprised no one offered to pour it into a frosted mug for him.

His first week at GAH, Mike was startled to find the guide’s room had only one double bed. He was expected to share it with a respected mountain guide who was absolutely his superior. It was their first time working together, so Mike suggested they sleep head-to-toe. Is that better, he wondered? Or was it awkward even mentioning it? Mike took the far side of the

bed so the senior guide wouldn’t have to climb over him to reach the outhouse in the middle of the night. But that meant Mike couldn’t sneak out if he woke up early. So the next morning, there he lay—staring at the gnarled feet poking out beside his face.

Why is it more intimate sharing a bed than a tent? he wondered. Because there’s less clothing? Dirty long underwear hung on a hook just past those grotesque feet. That week, in that bed, even Mike slept lightly, worried he might roll onto his boss or utter some incriminating nonsense in his sleep.

Luckily, the other GAH huts have bunk beds. Of course the roof is never quite high enough for adult bunk beds. Mike is not an early riser by nature, and he would typically only wake when the custodian, cook or guide sleeping below bumped their head on the wooden slats beneath his bunk. He would giggle while falling back to sleep, then wake in a panic later, realizing he was now late for work. Jolting up he’d smack his own head off the roof.

You might be thinking Mike sounds like a fictitious, more well-adjusted version of me—and I won’t argue with you. I will say that I no longer have the bump on my head, but those gnarly feet will haunt the rest of my days. I’ve gone on to sleep in trucks, snow caves and even a sea can at backcountry jobs. Crammed amongst my co-workers or guests at night, I still dream of the beds at CMH. And the cookies.

Daily life at GAH’s Sunrise Lodge. ANNE WRANGLER

Photo by Maur Mere Media

Photo by Maur Mere Media

Thinking About Visiting Golden This Winter? Your Questions, Answered.

Q.Why should Golden be my next winter getaway?

Golden is an authentic mountain town framed by three dramatic ranges: the Canadian Rockies, Purcell, and Selkirk Mountains. With legendary snow, awe-inspiring scenery, and a welcoming community, Golden delivers an unrivaled winter experience. Here, world-class adventure meets genuine mountain culture.

Q: Why ski Kicking Horse?

Just outside Golden is Kicking Horse Mountain Resort, only 15 minutes from town. Known for its 4,000 feet of vertical drop, champagne powder, and dramatic ridgelines, the resort offers some of the most unique big-mountain terrain in North America. Intermediate skiers can enjoy glorious top-to-bottom runs, while beginners will find more gentle terrain on Catamount Chair.

Q: Is there skiing outside the resort?

Absolutely. Golden is a haven for those seeking fresh tracks beyond the lifts. Heli-skiing was pioneered in the region, and today Golden offers four heli-ski areas, one cat-skiing area, and more than 20 lodges that provide guided ski touring experiences. Whether by helicopter, snowcat, or on a guided tour, skiing outside the resort in Golden means untouched powder and unforgettable terrain.

Fir & Feather TREEHOUSE

Top 1% on AirBnB.

Winter paradise, with off-grid trappers TENT, wood stove, outdoor kitchen, deck, firebowl, SNOWSHOES, and 100km of trails. MoonrakerMountain.ca MoonrakerrMountain@gmail.com

Get the FREE Golden APP tourismgolden.com/localapp

For a different pace, visitors can also enjoy Nordic skiing at Dawn Mountain, home to beautifully groomed trails and a welcoming community club that caters to all levels. It’s the perfect way to explore Golden’s winter landscape at a slower rhythm while still immersed in stunning mountain scenery.

Q: What other activities can I enjoy?

Winter in Golden is about more than skiing. Visitors can explore the scenic downtown, embark on guided snowmobile tours, go snowshoeing, or enjoy wildlife viewing. For families, ice skating, climbing, and local events bring the season to life. Don’t miss the annual Emberfest, a celebration of costumes, dance, and mountain culture.

Q: What makes Golden truly unique?

Golden is more than a resort town. It is a true mountain community where winter is a way of life. Visitors find world class adventure by day and genuine hospitality by night, with accommodations ranging from boutique lodges and rustic cabins to family friendly hotels. We look forward to seeing you here, whether you are carving fresh turns or simply enjoying the mountain life that makes Golden special.

Start planning: tourismgolden.com/life

Vagabond Lodge

Enjoy a boutique alpine luxury in the Rockies. Alpine skiing, snowboarding, Nordic trails, and fireside apres-ski comfort. Your exclusive mountain home awaits. vagabondlodge.ca info@vagabondlodge.ca

An ancient limber pine frozen in time on the Whaleback Ridge, Bob Creek Wildland Provincial Park.

The Old Ones

Tracking Alberta’s ancient limber pines through wind, time and wilderness

words & photos :: Andrew Penner

In the waning light, the sun a glossy orange ball hanging just above the North Saskatchewan River, I finally found what I had been looking for: a mangled monster of a tree, a gothic-looking beast reputed to be nearly 3,000 years old. Quite possibly the oldest living thing in Alberta. A little sapling, perhaps, when the ancient Greeks carved the last pillar of the Parthenon.

Alberta. The limber pine, Pinus flexilis, and the whitebark pine, Pinus albicaulis, are the only two endangered tree species in the province. The threats to these trees include white pine blister rust, which is a human-introduced fungal disease, as well as climate change, fire suppression and the mountain pine beetle. And certainly industrial activity—e.g., open-pit coal mining—and other human-authored disturbances of montane areas can also be significant issues.

The limber pine is a five-needled, slowgrowing pine with an upswept branched crown and rough, dark-brown bark with wide, scaly plates. It takes 40 years or more for the species to produce its large cones, and it relies primarily on the Clark’s nutcracker to disperse its seeds. And it’s critically important for soil stability in the montane,

The limber pine takes 40 years or more for the species to produce its large cones, and it relies primarily on the Clark’s nutcracker to disperse its seeds.

For five minutes or so, as the biting Chinook wind scoured the Kootenay Plains Ecological Reserve, I marvelled at the thing, wandered around the base (that took a while), and felt the prehistoric wood. Then, for the obligatory photos, I set up my tripod 30 feet away on a rock, hit the timer and settled under the tree’s cavernous trunk to give the photo some scale. My quest to find and photograph the famous Whirlpool Point limber pine was a success.

I’m smitten with a number of things on this planet. Turquoise mountain lakes. Knife-edge ridgelines. Massive cats at the top of the food chain. Bears. Blue whales. There’s a bit of trend, it would seem. And you can throw one more big thing into the mix: trees. The bigger, the better. If it’s ancient, grotesque, tough-to-find, weird or rare, chances are, I’m interested. I’m interested in Alberta’s limber pines.

Clinging to rocky outcroppings, cliffs, grassy slopes and wind-blasted ridgetops at higher elevations, predominantly found in prized and precious montane ecosystems, the limber pine is a unique and impressive species. They often stand alone, outliers, on otherwise barren and exposed terrain.

Although these trees are widely distributed throughout the Western United States, in Canada the limber pine is almost entirely confined to the montane subregion of the Rocky Mountain Natural Region in Alberta with a few scattered stands in the East Kootenays of southeastern British Columbia. And sadly, the limber pine—and its close sibling, the whitebark pine—is in rapid decline in

watershed management and carbon sequestering. Also, numerous small mammals and birds rely on it for shelter and as a food source—the seeds are packed with protein and have long been valued by Indigenous Peoples.

Without a doubt, the limber pine is an iconic symbol of Alberta’s southwest. In the Crowsnest Pass, for example, the famous Burmis Tree—it currently stands dead, propped up with brackets and a steel rod, beside Highway 3 as you enter the Crowsnest—is a cherished beacon adored especially by locals. If you’re zipping by, chances are a curious motorist will be stopped beside the road, taking a selfie with this left-for-dead but somehow-stillstanding landmark.

If conditions are favourable, a limber can live for more than a thousand years. Even longer! Its gnarled and twisted, wind-tormented branches are limber (hence the name of the tree) and, because of the deep, widespread root system, it’s able to withstand the significant forces—powerful Chinook winds and heavy snow loads—that punish it. Very few, in fact, are uprooted. Due to its penchant to grow in solidarity or in small stands on open, rockpeppered terrain, it’s often a survivor when grass fires sweep through.

Near Calgary, places like Bob Creek Wildland and Black Creek Heritage Rangeland—spectacular prairies-meet-mountains landscapes where lone limber pines reign on windy ridgelines—have an undeniable pull. This area, known as The Whaleback, screams Alberta—it’s an iconic western landscape if there ever was one. Wanderers, writers, musicians, local ranchers, naturalists, environmentalists, Indigenous leaders and lovers of untamed lands have voiced their affection and waxed poetic about the rugged beauty, the water and the important biodiversity found in this area. “Think I’ll go out to Alberta, weather’s good there in the fall,” wrote Ian Tyson in “Four Strong Winds,” perhaps the most famous Canadian folk song ever written. Tyson, who grew up near Longview, was certainly a champion for the protection of the region.

Corb Lund, Ian Tyson, Andy Russell, Kevin Van Tighem and Charlie Russell are just a few notables who have advocated for the protection of this under-pressure landscape. “This is sacred country,” said Lund in a recent CBC story on the highly controversial open-pit coal mining initiatives. Open-pit coal mining, which will decimate broad swaths of the landscape and destroy water quality,

is a massive environmental issue in this area.

“This land just gets into your soul,” says Lorne Fitch, a professional biologist, writer and a past adjunct professor with the University of Calgary. In decades of field work, Fitch has spent extensive periods in the Bob Creek Wildland and other remote areas in Alberta’s southwest. “Once these areas are disturbed, once roads are built and creeks are disrupted, it’s basically impossible to restore them.”

In Fitch’s most recent book, Conservation Confidential: A Biologist Investigates the Clash Between Progress and Nature, he devotes an entire chapter to the old trees—limber pines and Douglas fir, most notably—in Alberta’s southwest.

“In a way, old trees do talk,” he states in an early graph. “Not the garrulous narratives of elderly people, but with ancient wisdom acquired with centuries of life experience. Old trees have given us a gift of insight into climate and of extreme variability, especially on the drought side. It’s a cautionary tale about our future.”

Like many people, including Fitch, who value time in the wilderness, I, too, love to walk among the old trees, pull out my camera and capture the curling and contorted shapes, hear the creaks, the groans, as the ancient wood bends in the breeze. There is a power there, a benefit that—just like any potent in-nature experience—provides muchneeded soothing for the soul.

When you really love old trees. The author's tent on the Whaleback Ridge.

These moments drove me to learn more about ancient trees, and during my research I learned of the Whirlpool Point limber pine, culminating with that serene clifftop moment alone with the behemoth. But my successful quest only left me with more questions: Is the Whirlpool Point limber pine really 3,000 years old? Is it the oldest living thing in Alberta?

In one of my conversations with Fitch, he mentioned the extensive work of Dr. David Sauchyn, the director of the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative at the University of Regina. If there is a Wayne Gretzky in the old-tree-finding game, it’s probably Sauchyn. He’s devoted decades of his life to scouring Alberta (and Chile, California, Nevada and many other places where old trees can be found) looking for what he calls “old wood.” And, together with his team, he’s located and documented thousands of samples in Alberta, mainly in the Whaleback and Kootenay Plains Ecological Reserve, some of which are 1,500 years old. In his tree ring lab, Sauchyn has been able to analyze and decode more than 1,000 years of climate data.

But Sauchyn, an expert in dendrochronology (the scientific method of studying tree rings, typically by laboriously boring into the tree to obtain a sample), doesn’t buy the 3,000-year-old

age estimate of the Whirlpool Point pine made by more amateur tree hunters.

“The Whirlpool Point pine is rotten in the middle,” says Sauchyn. “They’re filling in the gaps using the measurements of the much thinner rings on the outside of the tree. The older growth rings, the ones that are gone in this particular tree, would be significantly larger. Ultimately, it can’t be proven, but my guess is this tree is, perhaps, half this age.”

Still curious, I asked Sauchyn about the legendary Great Basin bristlecone pine, Methuselah, which grows high in the White Mountains in eastern California. At 4,857 years old, it’s the oldestknown non-cloned living organism on earth. Not surprisingly, serious tree hunters consider visiting this ancient mammoth a rite of passage. Is it possible that a limber pine in Alberta could approach this kind of longevity?

Sauchyn cuts to the chase: “No, it’s not possible. Our colder climate just doesn’t support this. However, my search for old wood is far from over. My guess is the oldest tree in Alberta has not yet been found. It’s probably tucked away on some rocky ledge where it’s escaped fire, disease and other threats. I’m still hunting for that tree.” He likely has a few people hot on his heels.

I, too, love to walk among the old trees, pull out my camera and capture the curling and contorted shapes, hear the creaks, the groans, as the ancient wood bends in the breeze.

Hunting for ghosts on the Whaleback Ridge.

Low Burn

photographer :: Ryan Creary

athlete :: Thomas Honegger

location :: Revelstoke backcountry, BC

The plan was to wrap by dusk. But five minutes before the sun dipped behind the Monashees, the light started to break just right—and everything shifted. Photographer Ryan Creary and multidiscipline shredder Thomas Honegger stayed out past the usual call, milking the last hits of golden light. The payoff: some of Creary’s favourite frames of the season. The price: skinning out by headlamp, back to the vehicle by dark, stoke high.

The Nature of Music

The Journey from Tree to Cello

words & photos :: Laura Keil

In a mature, cedar-hemlock forest, the uppermost branches of a lonely Engelmann spruce pierce the canopy. Its needles have browned, its lower branches are bare. It is standing dead. Yet inside its bark lies something magical: straight white grain, strong enough to bear harsh pressure, both qualities necessary for tonewood and exactly what luthier David Carson is looking for.

Carson, owner at Mountain Voice Inc., measures the butt of the tree (76 centimetres are needed for a cello), and once the tree is cut he examines the grain, hoping for straight, even lines with few knots—qualities more common in old, dense forests where spruce forego lower limbs as they reach for sun in the shade of giants.

Carson’s dad, Gordon Carson, a lifelong logger and musician, first learned how to identify tonewood when a friend of his requested violin wood in the late ‘70s. From there his reputation and business grew by word of mouth until his son David took over in 2019. The operation, still located on Mount McKirdy, is powered by micro-hydro on a nearby creek. Stashes of tonewood for piano soundboards and guitars, as well as cello, violin and viola tops, are all over the property.

“A squirrel loses track of 70 per cent of its caches,” David Carson quips, as he walks through a field punctuated by stacks of wood. “We’re not quite that bad.”

David Carson examines a tall spruce tree on his family's Mount McKirdy property; the best spruce tonewood comes from dense, mature forests.

Aging the wood is important. The change in temperature, humidity and airflow helps season it. “You can either improve the tone by playing an instrument or you can leave it out to age naturally,” Carson says. “Many luthiers are looking for older wood because it puts them that much further ahead.”

Tapping to hear the wood’s tone is an immediate sensory connection to the tree’s innate ability to carry sound. Even a rough-cut board has resonance. In an age when music has gone increasingly electronic, wood still holds its own. Why do luthiers, musicians and tonewood seekers obsess over grain and density and more elusive aims like “flame” and character? It all begins with a tree. And a vision.

It’s a cold February evening in Valemount, BC, and up a long-forested driveway guests follow music-note signage to the home of Ann McKirdy-Carson and Gordon Carson. The house, overlooking a great swath of forest, was built for its acoustics, and entering is almost like stepping inside a hollow tree—wooden floors, ceilings and walls, with railings curved like the natural arch of a tree’s unique limb.

This is the first time professionals will play a cello and piano made from the couple’s tonewood in this space, and in the double-height living room cellist Martin Krátký and pianist Paul Dykstra get ready. Krátký repositions the cello and looks over at Dykstra. For Krátký, this moment began a year and a half earlier when he tested a cello at a convention. That instrument wasn’t a fit, but Montreal luthier Lucas Castera offered to build one for him. Krátký was asked to choose the cello’s top, which serves as the instrument’s face and is a key element in the sound. From photos, Krátký looked at the grain spacing and straightness and selected a piece of Engelmann spruce from Mountain Voice.

“You can either improve the tone by playing an instrument or you can leave it out to age naturally.” – David Carson

David Carson inspects aging tonewood, ideally seasoned for five years before sale.

Tonewood awaits a buyer.

“You want tight-grained, you want fairly regular, but not so much that it’s boring,” Krátký says. “So [mine] even has some bear-claw-like character—when the wood curves a bit on its own. You see the tree, the way it’s been growing. It’s just really alive, that piece of wood.”

Before Castera began work on his instrument, Krátký described his ideal sound: rounder, with a flame or vibrancy in the upper harmonic spectrum. And Castera set to work.

In his dimly lit workshop, side-lit so he can spot imperfections in the wood by shadow and silhouette, Castera uses planes, scrapers and curved chisels called gouges to shape the wood in three dimensions. All of it counts: the curvature, the thickness, the arching. It’s both an art and a science. Much like a sculpture, an instrument is as much about what you take away, creating the ideal open space and wood

Martin Krátký described his ideal sound: rounder, with a flame or vibrancy in the upper harmonic spectrum.

thickness for the sound to match the customer’s desires. Once shaped and glued, the instrument is tanned under UV lights and varnished.

When Krátký first saw his cello in person, the aesthetics struck him immediately. Castera, he says, is a master of varnish. “It was just really beautiful,” Krátký says. “And a lot of it is that spruce top.”

Castera incorporated caramelized honey from his family’s farm into that final layer. His varnish—composed mostly of linseed oil and balsam fir pitch harvested himself from the bubbles on tree bark—is made the same way it was 300 years ago, using local products. “I like to use what is already part of my life,” Castera says.

Once the instrument is in the client’s hands, the luthier holds his breath. In the small world of instrument making, a luthier cannot afford unhappy customers. Even though the cello was commissioned and Krátký liked it, he was still given the opportunity to test it for a month before committing.

The following winter, on McKirdy Mountain, the ears of friends and music-lovers pick up the pleasing resonances of the local wood. McKirdy-Carson is radiant. “It’s supergratifying,” she says. “The trees are singing to us.”

There’s a Japanese word, shin shin, that can refer to snow falling quietly and steadily. It’s ironic perhaps to name an instrument—which is used to create sound—after this phenomenon, but when Castera asked Krátký for a name, this is the word that surfaced.

Outside the house’s windows, snow falls gently. It collects on the crowns and branches of trees, a silent reminder of the natural forces—sun, wind, rain and shade—that drive the growth of the towering spruce trees that give their voice for music.

guitar body made from local poplar.

Cellist Martin Krátký at the house concert.

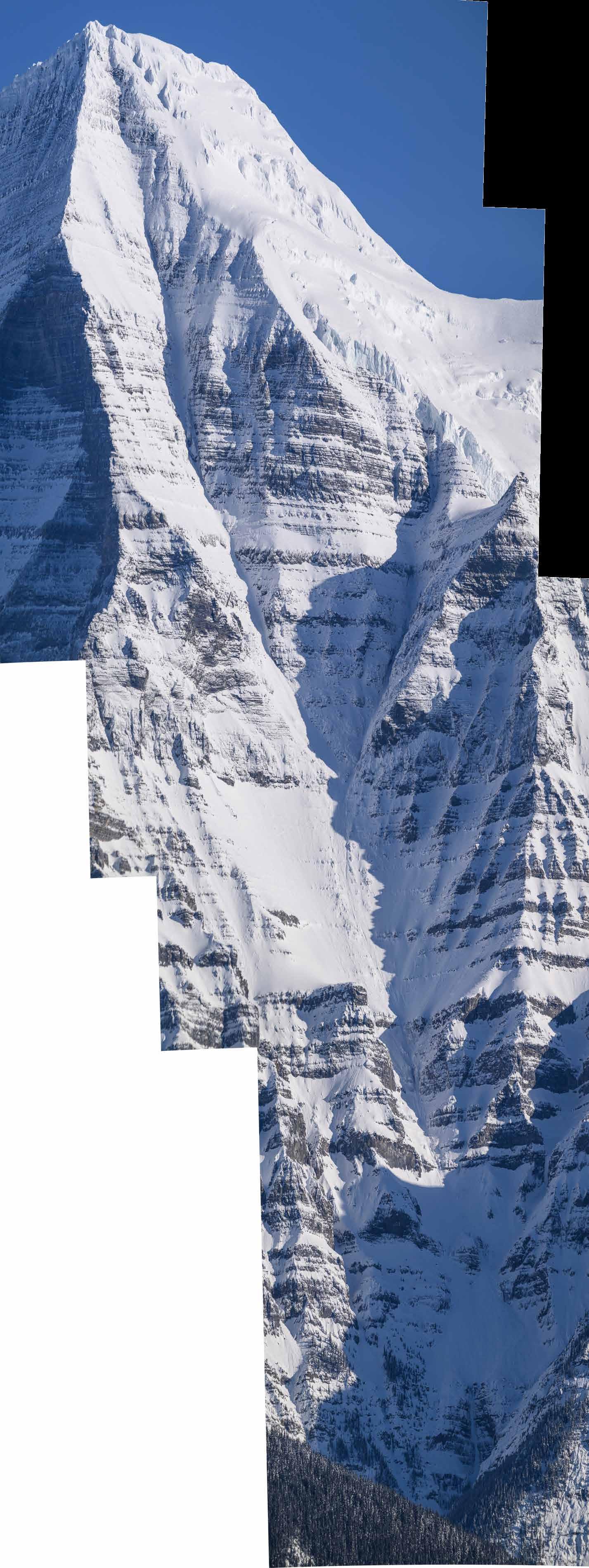

Queen Line

words :: Kevin Hjertaas

photos :: Blake Gordon

Robson, the King of the Canadian Rockies, towers above its surroundings—the monarch, holding aloft legends of mountaineering’s history. Its stature and its lore have attracted the great Canadian alpinists of every generation. So it was inevitable Christina “Lusti” Lustenberger would be drawn to it, too.

Born and raised in Invermere, BC, the ex-ski racer has become Canada’s most prolific ski alpinist, establishing technically challenging first descents on four continents, including a line down the Great Trango Tower that Outside magazine called, “The most impressive first descent of the decade.”

Most would consider it the line of a lifetime, but when asked in the spring of 2025 to imagine her dream line, Lusti replied, “Oh. Well, I think I just did it. I think it was Mount Robson.”

She’s referring to the Great Couloir on the south face of Mount Robson. The previously unskied line drops a massive 2,954 metres from the summit and features a face up to 50 degrees with waterfall ice and mixed climbing. Impressive, but how could a mountain so close to home outshine Himalayan or Baffin peaks? “There’s something intoxicating about experiencing a story that lives in our home range,” Lusti told the crowd at the Banff Mountain Film Festival in 2025. “It [Robson] holds stories older than us. This is a 10-year dream and a continuation of those that came before. Robson is more than a mountain; it’s a monument of imagination.”

As the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies at 3,954 m, and the

most prominent in all of North America with a vertical relief of 2,829 m, The King has always drawn attention. The Secwépemc people call it Yexyexéscen, “The Mountain of the Spiral Road” for its striped rock bands. Conrad Kain, Canada’s most famous mountain guide, first stood on the summit with his clients in 1913. Mountaineers have tested themselves on its various faces ever since. Legendary Canadian alpinists like Barry Blanchard and Marc-André Leclerc have etched their stories on the peak with standard-setting ascents, and countless unrecognized climbers have played out their own dramas on its slopes. In 1983, Robson was finally skied from the summit by Pembertonian Peter “Peru” Chrzanowski, but Robson’s highly coveted north face eluded him and everyone else for years. Numerous wellfunded, widely publicized expeditions tried, but the face rebuked them all—until a pair of young ski bums quietly decided to have a look.

Pique Newsmagazine told their story in 1995: “Two Whistler adventurers used the light of the full moon and the native name of Mount Robson [Yuh-hai-has-kun] as inspiration as they pulled off the first ski descent of the highest mountain in the Canadian Rockies. Ptor Spricenieks and Troy Jungen summited the 3,954-metre peak in the pre-dawn moonlight last Saturday after a gruelling four-anda-half-day ascent and skied down the entire mountain in a dayand-a-half. ‘This is the greatest adventure so far in my life,’ says Spricenieks, 27, a global ski tourer and cosmic consciousness raiser. According to Spricenieks, cosmic couch surfer Jungen had been carefully monitoring the snow conditions on Robson all summer and a combination of summer storms and the full moon prompted the pair to attempt the descent.”

Lusti above Robson's Kain Face during the team's second attempt.

The south face bowls in slightly for its entirety, creating a monstrous funnel that draws any falling rock or snow into its guts: the Great Couloir.

Lusti (lead) and Gee (second) ascending out of the Cascade, seen at bottom centre of image.

It stands as one of the continent’s greatest ski descents—ever— and that story has added to every skier’s experience on Robson since. Seemingly at the peak of her career, Lusti was ready to add a new chapter to the legend. And to create a great story, you need great characters.

“I’m a French mountain guide from Chamonix, the center of the universe,” Guillaume “Gee” Pierrel jokes. On first impression, Gee is a swashbuckling Frenchman: all panache, mustache and joie de vivre Helmet-less and hanging off massive mountains, Gee’s smile is the perfect foil to Lusti’s razor intensity.

“He’s the person who laughs when your plan sounds completely insane, but still shows up,” Lusti says. “There’s plan A, plan B and plan C. Then there’s plan Gee.”

Luckily, Gee is also one of the most competent climbers and skiers in the world, with the experience and talent needed for an objective like Robson’s Great Couloir. Still, Gee admits he didn’t know what he was getting into: “I didn’t do much of the research and prep. I just showed up. So when we turned the last corner and saw the face… Wow. That’s serious, actually.”

the simple hut, they could fly drones over the ridge to find Lusti and Gee, then film the action for a few minutes before needing to return for fresh batteries. When the skiers encountered dangerous crux moments—struggling to find good ice to climb or scratching for an edge hold on the way down—the 10-minute pause in contact was anxiety-inducing.

“It’s weird because you are sitting up there at this hut on one of Canada’s biggest mountains in -40 C and you have batteries and drones and all this stuff plugged into a generator,” says Phil. “You have this sense of security while these two are fighting for their lives, a ridge over from us.”

“I was filming them on a rappel and I saw three little avalanches coming straight towards them. There was nothing I could do. They were literally in the middle of this rappel when I saw it break off.” – Phil Forsey

While Gee came to terms with the size of the objective, Sherpas Cinema, sensing something special, mobilized a small team to capture it all. Phil Forsey took the director’s role and quickly saw the gravity of what the skiers were planning and how their descent might fit into Robson’s legacy. “Learning the history is always exciting for me. It creates a deeper connection,” he says.

Phil and photographer Blake Gordon set up at the Ralph Forster Hut, around a ridge from the south face and the Great Couloir. From

What stands out to alpinists about the Great Couloir and the entire south face is not their steepness or technical difficulty; it’s the shape of the mountain. The south face bowls in slightly for its entirety, creating a monstrous funnel that draws any falling rock or snow into its guts: the Great Couloir. Every moment spent in the couloir increases one’s risk of being hit by something. There’s simply no place to hide for most of it. The only way to diminish the hazard is to move quickly—something Lusti and Gee are good at—and to make the attempt only when the mountain is frozen solid.

Day one was arduous bushwacking and monotonous slogging to a bivy site. The next day they climbed the Great Couloir for hours. By the time they reached a ledge system that would access the summit ridge, it was late and the weather had deteriorated significantly. Just 150 vertical metres short of the summit, but with precarious climbing ahead, the pair decided to turn around and use what energy they had in reserve to ski down 2,800 m of technical terrain.

LEFT Gee and Lusti at basecamp on the eve of the second attempt. RIGHT Gee (below) and Lusti (above) navigating a choke at dusk while descending on their first attempt.

Beyond the convenience, choosing Roam is an act of local stewardship. Every time you ride with Roam, you help to reduce tra c congestion and limit vehicle emissions in the Bow Valley. It’s an easy and essential way to show your commitment to sustainability while still getting exactly where you need to go.

Get your paperless passes by downloading either app below. Visit our website for more details.

The descent, with its steep, incredibly narrow sections and seven rappels, took them three and a half hours.

It was the right call. The snow was terrible. Bits of ice had fallen over the face and peppered the couloir with pockmarks and refrozen chunks. It took hours of arduous skiing, rappelling and crashing through bush to get back to the motorhome, three hours after sunset.

Lusti and Gee had climbed and skied the Great Couloir safely, but they hadn’t skied off the summit. With no interest in the objective hazard of climbing the couloir again, they made a plan to try again from the other side. After a couple of days’ rest, the crew took a helicopter to The Dome, a smaller peak and typical bivy site for standard ascents of Robson. The next morning, Lusti and Gee climbed from there to the summit and skied off that legendary peak under clear skies. They made their way to the ledges where they’d turned around previously, then removed their skis to delicately cross over to the top of the Great Couloir once again.

The snow in the couloir was much better this time, enjoyable even. But the drama wasn’t over. The descent, with its steep, incredibly narrow sections and seven rappels, took them three and a half hours. As the sun warmed the mountain, snow began to sluff down the south face. Phil was watching it all through his drone’s screen: “I was filming them on a rappel and I saw three little avalanches coming straight towards them. There was nothing I could do. They were literally in the middle of this rappel when I saw it break off.” Phil used the radio to warn Lusti and Gee but, hanging from a rope in the dead center of the slope, there was no escape. “As soon as I told them, they both kind of froze.”

Everyone held their breath until the slide stopped short and the pair continued their descent safely. Gee admitted later that the route had been near the limit of his risk tolerance. The relief they felt after completing the descent slowly gave way to satisfaction and, later, appreciation for what they’d accomplished.

“It just feels so authentically a part of my story,” Lusti says. “I’m just so proud of that mountain and it being in the Canadian Rockies. I think it’s one of the world’s most exceptional peaks. It holds up to any Himalayan face, and there’s tons of history and Canadian culture. There’s a lot of pride connected to the mountain for me.”

Later, when asked to reflect on the Robson stories and accomplishments that preceded theirs, Lusti said, “There’s richness in that. There’s richness in these people’s lives. There’s purpose and meaning that they find up there. And I think that’s contagious. And I hope our line, and the movie we’ve made, shares that contagion.”

Lusti gearing up at daybreak.

words :: Meghan J. Ward

photos :: Georgi Silckerodt

The Medicine of Horses

The sense of expansiveness is powerful at Star 6 Ranch, even amid the circle of structures, paddocks and timber fences that mark the property. Beyond a redroofed barn and several small cabins, wild spaces beckon—open grassy meadows belted by poplars, the forested banks of the Kananaskis River and distant views flanked by the peaks of the Rocky Mountains. It was into this land in Kananaskis Country, just off the Trans-Canada Highway, that Chloe Vance first stepped on a crisp day in November 2019, immediately knowing it was special. “I was like, I’m supposed to be here, but this makes no sense,” said Vance. “It felt like I was coming home or coming back to something.” Vance pinned a postcard from Star 6 to a bulletin board as a reminder of this calling, but it wouldn’t make sense for another two years.

On one level, Vance’s attraction to the equestrian vibes of Star 6 made sense. Raised in Ontario, she had grown up riding, training and competing alongside horses. She pursued this passion through university until she was introduced to the world of outdoor expeditions. With that introduction, her passions shifted: She sold her horse and dove into wilderness guiding. Vance and her husband, Rob, moved to the outdoor-loving community of Canmore, AB, in 2010.

Vance spent several years guiding before settling into a job in Canmore supporting Indigenous youth in the school system. Then, in 2016, challenges with infertility threw her into a downward spiral. In her path to healing, Vance realized something had been missing from her life:

horses. Immersing herself in their company, she began to heal. To her astonishment, within a few months she discovered she was pregnant. Vance gave birth to a daughter, Quinn, in 2017, and eventually got back into the saddle training and riding horses. Inspired by her renewed connection with horses, she began coursework in equine therapy.

Vance was working with several nonprofits, including Spirit North, when she first visited Star 6 in 2019. At that time, the 80-acre property—founded four years prior by Banff’s Fiona Mactaggart—offered no formal programming, only potential. Mactaggart’s two-part vision was simple but profound: to share the land and foster resilience and healing in others. Then, in June of 2021, Mactaggart suffered a traumatic brain injury; it was an uncertain time for the family and the ranch. But it was precisely then that Vance met Mactaggart’s husband, Kevin, during a Spirit North event at Star 6. He asked if she might volunteer to support the horses. Vance jumped at the opportunity. That same summer, during a ride at Star 6, she had visions of community gatherings, ancestral connection and regeneration of the land. The experience was so powerful that she wrote a letter to Mactaggart, saying she felt they were meant to work together.

Vance’s letter arrived during Mactaggart’s recovery, and once she was out of the hospital the pair met at Star 6. “Chloe and I collided. We came together at an incredibly vulnerable time, not just in my life, but also in the life of the ranch,” said Mactaggart. The injury had strengthened Mactaggart’s resolve to position Star 6 as a place of healing and connection. Vance’s teaching and outdoor

educational background, decades of experience with horses and vision for Star 6 were much needed and nothing short of miraculous. In time, Star 6 would focus on land stewardship, relational horsemanship and land-based learning, with Vance in the saddle as the director of programming and herd guardian.

Since stepping into the role, Vance’s hats have been many, but the load has

The herd grazing in the home paddock at Star 6 Ranch. Graeme Kennedy

lightened as new team members, including her husband, have come on board. Outside her official titles, she’s still driving the tractor, feeding chickens, gardening and hauling hay. As herd guardian, she is responsible for the horses’ care, maintenance and training, as well as their feeding, using established rotational grazing zones to help regenerate the land’s natural ecology. As programming director, she collaborates with the Star 6 team to design custom, land-based experiences and hosts the diverse groups who use the property’s venues for gatherings such as wellness retreats, educational groups, Elders’ crafting circles and trauma support.

“To have Chloe’s unflagging support of the potential of the Star 6 Ranch is something that I lean on in the good times and in the bad times,” says Mactaggart.

Yet, of all the hats Vance wears, there’s one that has an extra touch of magic. Building on her personal experience of healing and connection through horses, Vance has developed Equine Connection sessions, which focus on self-discovery, reflection and personal growth through interactions with the Star 6 herd.

Horses have long been used as a therapeutic aid for a wide range of conditions, including anxiety, depression, PTSD and addiction. Vance’s approach weaves together relational horsemanship, neuroscience, equine behaviour science, traditional nature-based wisdom and

transformative coaching, as well as formal training in horse medicine leadership (focusing on the somatic system) and certification with the EQUUS Academy in New Mexico. Vance says we can learn a lot from horses as masters of survival: “They’ve been around for about 56 million years. They are one of the longest-standing species, albeit in slightly different forms. To exist for that long as a prey animal means you’ve got to be highly attuned, highly aware and perceptive.”

Vance’s work is rooted in Indigenous knowledge and the belief that all things hold a medicine meant for the world. The sensitivity and intelligence of horses make them particularly adept at encouraging their human counterpart to self-reflect. “Horses give us feedback to reflect in a way that humans can’t because humans will intellectualize it,” she says.

Vance’s one-on-one Equine Connection sessions (small groups are also welcome) begin by simply observing the herd, which gives her the information she needs to help guide the next step. At times, it brings up a reaction in the participants. Often, the horses—whom Vance considers to be equal partners in the process—reveal the next course of action. “I definitely now have a sense of different horses and their individual medicines, where they tend to step in, the type of situation that might be happening for that person.” As an example, she points to

a grey-coloured steed named Gandalf. “He’s very strong, steady, grounded. I’ve seen him step in many times now for people who are in some sort of relationship challenge.”

Vance has a repertoire of exercises to use as needed, but Equine Connection sessions are fluid, unfolding one sequence at a time. For Vance, it’s like following a thread of actions, reactions and, for the most part, the unspoken moments transpiring between horse and human.

Mactaggart herself has experienced Equine Connection sessions with Vance. “If you can bury your own ego and your own hubris and open yourself up to raw observation,” says Mactaggart, “the wisdom that falls in, that Chloe channels, is overwhelmingly remarkable.”

Vance sees how these sessions impact not only the individual but also the Bow Valley and beyond. Witnessing the magic that has been finding her purpose at Star 6 has given her further evidence. “When we reconnect with our most authentic self, we can then put that out there,” she says. “That’s when we can be an engaged community member. That’s when we can be the best partner, the best parent that we can be. And then it starts to bring it out in other people. And that is, then, the interconnected web.”

To learn more or book a session visit star6ranch.com

ABOVE Star 6 owner Fiona Mactaggart. PAGE 46, TOP LEFT Chloe Vance. BOTTOM RIGHT Fiona Mactaggart and Chloe Vance.

Experiencing an environment—its light, its weather, its atmosphere— is what primarily influences the work of artist Dee McLean.

A scientific illustrator and painter, McLean uses art as a vehicle to engage her audience with science and the climate crisis, asking, “What effect was it having on places where I have emotional connections?” in her 2023 exhibition Water, Wilderness and Wildfires.

That exhibition took place before the historic 2024 Jasper wildfire, when a third of the town tragically burned. McLean, who lives in London, England, watched the devastation unfold. She felt powerless, left to worry from afar about a place her daughter and son-in-law, residents of Jasper, love so much. “There was nothing I could do,” she recalls.

Then came the pyronema omphalodes: a bright orange fungus that fruits on the ashes of woody debris. In the aftermath of Jasper’s highintensity, high-severity burn, the short-lived mycelia—and other photogenic fire phenomena— was widespread.

Knowing she’d like to paint the spectacle, McLean’s son-in-law, a Jasper National Park trail crew member, sent her images from the field.

“The growth after the fire was extraordinary,” McLean said. “I had to paint it.” Soon after, staff at the town’s iconic local ski shop, Totem, wanted to immortalize McLean’s art on the slopes.

Now, with the help of ski manufacturer Armada, a special run of skis will honour Jasper’s the loss, but also its renewal. Via the topsheets of 106 pairs of the company’s best-selling ARV series, McLean’s vibrant illustrations will debut on ski slopes this November.

McLean hopes the limited-edition skis help people connect not just their turns, but the dots between the climate crisis and their communities. She has seen in Jasper that wildfire prevention and recovery begin with togetherness.

“Jasper has shown extraordinarily resilience,” she says. “It seems that being connected as neighbours has a lot to do with that.”

REDEFINING ADVENTURE AFTER TRAGEDY

Trailblazing: The Matt Hadley Story, a new documentary by emerging Canmore-based filmmaker Kim Logan, is gaining attention on the global festival circuit. Created by an almost all-Alberta team, the film follows Matt Hadley, a former elite mountain biker once ranked fourth in Canada, whose life changed forever after a devastating 2019 rockfall accident. His journey of reinvention as an adaptive adventurer explores resilience, loss and the barriers of accessibility.

If his name doesn’t sound familiar, his work likely does: Matt helped design and build iconic trails like the High Rockies Trail and the redeveloped Ha Ling and Yamnuska Trails, leaving a lasting mark on Alberta’s outdoor culture. The film honours his legacy.

“When I first read about Matt’s accident, I was struck by the story of someone in our small community not only surviving a tragedy but consciously deciding to adapt and redefine his reality. That takes a lot of courage and perseverance, and is not by any means easy,” says Logan. “Matt’s inspiring story was begging to be told. It challenges perceptions of what it is like to live with a disability and celebrates the spirit of human resilience.”

Trailblazing features universal themes of persistence and possibility that resonate with adventurers, athletes and anyone who has faced adversity.

Trailblazing won a Golden Sheaf Award at Yorkton Film Festival and earned a Rosie Award nomination from the Alberta Media Production Industries Association. It will screen at festivals through 2025 before streaming on TELUS Optik TV, Stream+ and STORYHIVE’s YouTube in 2026. Watch the trailer and learn about upcoming screenings at trailblazingfilm.ca.

Matt Hadley and Kim Logan on the last day of filming. MICHAEL KLEKAMP

Dee McLean in her home studio. SABINE TILLY

MOUNTAINEERING WOMEN: CLIMBING THROUGH HISTORY

By Joanna Croston

There aren’t enough books about bad-ass women doing their thing, quietly or not-so-quietly breaking records, living their lives on their own terms and sending their potential. A new book by Joanna Croston, Mountaineering Women: Climbing Through History aims to fill this gap, with biographies of 20 remarkable women climbers who have made their mark and pushed the limit on mountaineering.

Croston, the director of mountain culture at the Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival & World Tour, is a writer and climber who has climbed and skied mountains around the world. The book is beautifully illustrated by Tessa Lyons, an artist and climber from North Wales. This connection between the artwork and the text adds to the narrative, allowing the reader to follow along visually.

The task to choose 20 climbers could not have been an easy one. Croston writes that her initial list included more than 70 women. Most difficult was finding information on Indigenous women climbers and those of African and Asian ancestry: “I’ve included some remarkable climbers from these underrepresented groups among these pages, but even in the 21st century, these stories are difficult to track down.”

Croston was able to research and write the stories of many of those women, including Junko Tabei (from Japan), the first woman to ascend Mount Everest in 1974; Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, the first Nepalese woman to summit Everest; Juliana García, an Ecuadorian and certified IFMGA Mountain Guide; Wasfia Nazreen (from Bangladesh) who climbed the Seven Summits as well as K2; and Kei Taniguchi, a Japanese woman who summited Kamet and received the celebrated Piolet d’Or (Golden Ice Axe) in 2009.

Many of the biographies focus on women who are still climbing, and include stories of the climbers’ personal drive, hard work and strong instincts. In some, the women were called selfish or liars, some were left behind by their teams, while others were forced to quit their in-progress climbs. Each biography includes a story of a climb, and Croston shines as a storyteller. A timeline of all noted dates in the book, a graphic lining up the mountains conquered and their profiles from Everest to El Capitan, a glossary of climbing terms, a small section of 15 additional female climbers and three, full-colour image galleries make this book a joy to peruse.

This beautiful book collects and shares the stories of extraordinary women climbers in one place, inviting readers to reckon with our unlimited potential. – Laura Ollerenshaw

CROSSINGS: HOW ROAD ECOLOGY IS SHAPING THE FUTURE OF OUR PLANET

By Ben Goldfarb

Crossings is a road ecology masterpiece, one of beauty, hope and heartbreaking loss. Through writing that is as evocative as it is thorough, Ben Goldfarb shines a light on the wild and human interconnections bound together through the omnipresent entity of the road.

“A triumph of writing and reportage…from one of the best environmental writers of his generation,” writes jury member Gloria Dickie of Crossings’ grand prize win at last year’s Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival.

I listened to the audiobook as I drove east from Canmore on a sultry Saturday morning.

Goldfarb’s vivid stories gave me fresh eyes and big, new questions as I drove past a bumper-to-bumper wall of mountain-bound cars, then later beneath the recently completed Peter Lougheed wildlife overpass, a striking echo of Banff’s world-renowned vegetated crossings.

The stories in this book have transformed how I relate to our sprawl of asphalt and gravel. It’s easy for roads to fade into the routine of our lives but, for the animals who must navigate around them, roads are an insatiable predator, an impenetrable wall, a pervasive noise far from routine.

It’s easy for roads to fade into the routine of our lives but, for the animals who must navigate around them, roads are an insatiable predator, an impenetrable wall, a pervasive noise far from routine.

Crossings asks us to bear witness to loss and let hope guide us to action, to consider: What do animals need from us? Do we want to live in communities governed by roads? Have roads served what we value most about our communities? All are questions I found myself asking on a recent morning when my bike commute was paused by a rutting bull elk. In the brightening grey light, on a lowspeed road, he strolled down the centre line, his antlers spanning the width of a car.

Roads, in their unending reach, represent dominance over nature. Crossings challenges us to imagine infrastructure that honours all who move through the land. – Margaret McKeon

Florina Beglinger, Rogers Pass. LAURA SZANTO

Julio Figueredo, Athabasca Glacier. THOMAS GARCHINSKI

Available at your Favorite Local Retailers

It’s a bold goal to make the best better. Over the past 13 years, our PowSlayer series has earned a near mythical status among those seeking the steepest, deepest powder in the biggest mountains. These aren’t the ones bragging at the end of the day; they are the ones who let their tracks do the talking, who start before sunrise and leave behind lines as proud as they are nameless.

Our new PowSlayer Freeride Kit is built for those riders.

Ryland Bell slays the powder line of his life near Haines, Alaska. Nicolas Teichrob © 2025 Patagonia, Inc.

1. THE NORTH FACE WOMEN’S SUMMIT SERIES VERBIER GORE-TEX JACKET is built for riders who don’t sit out storms. With 100 per cent recycled waterproof GORE-TEX fabric, pit-zip ventilation and stash-ready pockets, it delivers uncompromising performance. This isn’t outerwear—it’s armour for big lines. thenorthface.com // 2. From alpine ridges to northern powder stashes, the RAB MEN’S OPTICAL WATERPROOF DOWN JACKET delivers featherlight warmth and total protection. Waterproof Pertex Shield, 700 fill-power down and low-bulk mobility make it a go-to layer for epic winter adventures and high-altitude exploration. rab.equipment // 3. The BAFFIN TERRAIN COLLECTION redefines hiking performance with its blend of rugged durability and advanced technology. Engineered for challenging terrain, the collection features IceBite for superior traction and a secure lace clip for a customized fit. With a new insole design for enhanced cushioning and a fixed-fit liner for optimal comfort, the Terrain Collection ensures stability and support. mec.ca // 4. Did you know up to 45 per cent of body heat is lost through the neck and the head? PUFF, the original down-filled neck warmer, is stretchable and holds its shape–making it breathable while protecting you from the elements. Offered in a variety of colours and sizes. One dollar from every PUFF sold is donated to POW Canada. puff.design // 5. The ARC’TERYX QUINTIC 28 BACKPACK is freeride-specific, designed to have a shorter back length without compromising midsize capacity. It’s roomy enough for avalanche gear, extra layers, skins and the essentials you need for big days on snow but compact enough it won’t hinder a backflip. Built with a hybrid of weather-resistant fabrics and ultra-durable nylon with a light, flexible frame, this pack delivers the stability to keep your centre of gravity solid. arcteryx.com

6. The ORAGE MTN-X SPURR JACKET is made for skiers who stay out when the temps dip and the wind howls. The Spurr is a waterproof, windproof three-layer shell with just the right mix of function and ski-town style—built to handle the worst a Canadian winter can throw at it. vertical-addiction.com // 7. Keep your chicken nuggets hot on the trail with this 100 per cent leakproof and dishwasher safe YETI RAMBLER 236 ML INSULATED FOOD JAR. Stay fueled wherever your adventure takes you, whether it’s morning oats or a midday salsa snack. The MagVent lid uses a two-piece system to vent out hot air as it opens, and it comes apart for easy cleaning as well. Also available in 473 ml. yeti.ca // 8. Conditions in the backcountry are always changing, be it the weather or how hard you’re working. The snow-specific midlayer of the PATAGONIA NANO-AIR ULTRALIGHT FREERIDE JACKET is built specifically for the skintrack and designed to be worn all day, on its own or under a shell. It combines weather-resistant fabric at the hood and shoulders with a lightly insulated body for the perfect balance of protection and breathability. patagonia.ca // 9. Conquer winter with OSPREY’S MOUNTAIN BOUND SKI & SNOWBOARD ROLLER BAG. Oversize wheels and a rugged chassis tackle snow, ice and rough terrain, while NanoTough water-resistant fabric shields skis or snowboards up to 195 cm. Whether it’s backcountry powder or a multi-mountain tour, this bag moves as hard as you do, blending unstoppable durability with effortless travel ease. osprey.com // 10. Perfect for high-output pursuits, the SWANY AIR GLOVE keeps hands warm and dry with breathable, moisture-managing materials and dependable weather protection without adding unnecessary weight. swanycanada.com // 11. Be it hut trips or hot laps, the PATAGONIA POWSLAYER PACK is a backcountry gear wrangler built for hunting powder stashes all season long. Featuring a dedicated compartment for snow tools, an easy-access back panel, and body-hugging shoulder straps and hip belt. patagonia.ca