Wine and the Martinis

By David O’Reilly

If you’re a woman who is 40 or older, an annual mammogram is an important step in early breast cancer detection. Mammograms are quick, covered by most insurance and can be scheduled with ease.

Early detection saves lives. Make your health a priority this Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

Schedule your mammogram at Guthrie today by scanning the QR code, visiting www.Guthrie.org/Mammogram or calling 866-GUTHRIE (866-488-4743).

By Terence Lane

By Phil Hesser

By David O’Reilly

Carolyn Straniere

By Lilace Mellin Guignard

Dave DeGolyer

Maggie Barnes

Paula Piatt

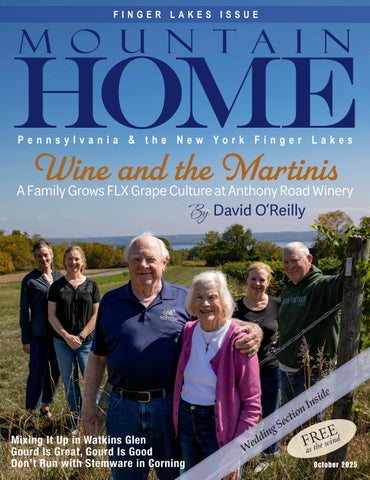

Cover photo by Wade Spencer. This page (top) The four Martini kids in

(middle)

(bottom)

mountainhomemag.com

E ditors & P ublish E rs

Teresa Banik Capuzzo

Michael Capuzzo

A ssoci A t E E ditor & P ublish E r

Lilace Mellin Guignard

A ssoci A t E P ublish E r

George Bochetto, Esq.

A rt d ir E ctor

Wade Spencer

M A n A ging E ditor

Gayle Morrow

s A l E s r EP r E s E nt A tiv E

Shelly Moore

c ircul A tion d ir E ctor

Michael Banik

A ccounting

Amy Packard

c ov E r d E sign

Wade Spencer

c ontributing W rit E rs

Maggie Barnes, Melissa Farenish, Dave DeGolyer, Phil Hesser, Terence Lane, David O'Reilly

Paula Piatt, Karey Solomon, Kelly Stemcosky, Carolyn Straniere

c ontributing P hotogr AP h E rs

Cameron Clemens, Terence Lane, Paula Piatt, Kelly Stemcosky

d istribution t EAM

Dawn Litzelman, Grapevine Distribution, Linda Roller

t h E b EA gl E Nano Cosmo (1996-2014) • Yogi (2004-2018)

ABOUT US: Mountain Home is the award-winning regional magazine of PA and NY with more than 100,000 readers. The magazine has been published monthly, since 2005, by Beagle Media, LLC, 39 Water Street, Wellsboro, Pennsylvania, 16901, online at mountainhomemag.com or at issuu.com/mountainhome. Copyright © 2025 Beagle Media, LLC. All rights reserved. E-mail story ideas to editorial@ mountainhomemag.com, or call (570) 724-3838.

TO ADVERTISE: E-mail info@mountainhomemag.com, or call us at (570) 724-3838.

AWARDS: Mountain Home has won over 100 international and statewide journalism awards from the International Regional Magazine Association and the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association for excellence in writing, photography, and design.

DISTRIBUTION: Mountain Home is available “Free as the Wind” at hundreds of locations in Tioga, Potter, Bradford, Lycoming, Union, and Clinton counties in PA and Steuben, Chemung, Schuyler, Yates, Seneca, Tioga, and Ontario counties in NY.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: For a one-year subscription (12 issues), send $24.95, payable to Beagle Media LLC, 39 Water Street, Wellsboro, PA 16901 or visit mountainhomemag.com..

Wine and the Martinis

A Family Grows FLX Grape Culture at Anthony Road Winery

By David O’Reilly

Wade Spencer

Anthony Road, with the tasting room on the left and production facility on the right, leads to happiness (and Seneca Lake).

The Long and Winey Road

It was a cool April day in 1973 as John and Ann Martini drove down New York’s Route 14 in their Pontiac LeMans with their two small kids.

At a remote stretch of rural Penn Yan they turned left onto Anthony Road, but not for its sweeping views of Seneca Lake. John, thirty-one, had just quit his job at a chemical company in Baltimore after a banker friend suggested a radical career change: “Why don’t you grow grapes?”

“Well, we knew nothing about farming or growing grapes,” John, now eighty-three, recalls with a laugh. “So that’s exactly what we did.” Rumpled, white-haired, and manifestly unsnobbish, he’s seated at a table in the elegantly understated tasting room of his family’s acclaimed Anthony Road Winery. It’s a sunny afternoon in the waning days of summer, and at adjacent tables seventeen patrons are sampling some of the best wines made in New York State. “This is one of our favorite wineries,” says Dan Breckenridge, a welding supply salesman from Aurora, New York. “The wines are delicious and the people are great.” He and his wife make it a point, he says, to visit at least once a year, usually with friends.

“We’re dry red people,” explains his wife, Nancy. Today, after sharing two tasting flights while gazing out on the slate-blue lake, they’re heading home with three bottles: a Cabernet Franc, a Lemberger, and, their favorite, a Cabernet Franc-Lemberger blend.

“There’s a lot of fun in that bottle,” says Dan, sixty-three.

The Martinis currently bottle 10,000 cases annually and ship to thirty-nine states. About sixty percent of their sales is wholesale, with the rest sold more profitably out of the tasting room.

The thing is, none of this was supposed to happen. Five decades ago—when all of New York boasted just eighteen wineries—John and Ann rarely drank wine and had no intention of launching the nineteenth. Growing grapes had appealed simply because Ann’s parents lived ten miles up the road in Geneva. And the giant Taylor Wine Company in Hammondsport was paying good money for the grapes it turned into the sweet, fortified ports and wines then popular across America.

“My philosophy has always been ‘try something,’” John explains with a shrug, though eldest daughter Sarah Eighmey, head of operations since 2013, offers a different explanation. “Dad can get talked into things very fast.”

“It’s been an interesting ride,” says John, though he concedes it’s lately turned bumpy. Consumption of fine wines and other alcoholic beverages is in marked decline, especially among younger adults turning to cannabis or drinking less for health reasons. In July the percentage of U.S. adults who drink alcohol fell to fifty-four percent, the lowest since Prohibition.

Nevertheless, today all four of the Martini children are active in the operation. In ad-

Grape Expectations

Ann and John (left) get new tanks in 1989, and winemaker Peter Becraft checks the sugar level, anticipating the wine to come.

dition to Sarah, son Peter is vineyard master, Liz runs the tasting room, and Maeve is office manager. Several spouses and grandchildren also take part.

“Every day I try to figure out how much we have to make to support the families and staff under this umbrella,” says Sarah. Sales of Anthony Road wines are down six percent over last year, and this sunny tasting room, with its soaring ceiling and sleek rosewood tables, is seeing about 200 fewer patrons each month than in 2024.

“But I think the wine industry goes like this,” she says, and makes an undulating, wave-like gesture with her hand. “We’re in a down phase now, but I think positively—that there’s going to be an up—and that we’ll ride the wave. But we’re not going to chase wine in a can or box wine….We’re staying true to who we are and what we’ve been.”

And how many different wines do they now make? She thinks for a moment, reaches for a tasting menu, and starts counting off the offerings: sparkling riesling…unoaked chardonnay…pinot blanc…skin fermented pinot gris…barrel fermented gewurztraminer…rosé of cabernet franc…pinot noir…lemberger… “Thirty,” she tallies, and laughs. “Too much.”

Perhaps. But their winemaker, Peter Becraft, is “proud of them all.” He strives to “create wines that are balanced,” he says, and an “expression of our site.” He began as a vineyard worker here nineteen years ago, then apprenticed for six years in the cellar under his prede-

cessor. “I’m lucky because I have the luxury of estate-grown grapes. So it allows you to really understand the place.”

Dry riesling and the rosé of cabernet franc are their top sellers, followed by pinot gris and cabernet franc. Their 2022 dry riesling—which Peter’s notes describe as tasting of “ripe fruit, lemon, peach, and honeysuckle”— was rated a 92 by Wine & Spirits magazine and a 93 by wine critic James Suckling. He also gave a 92 to their rosé of cabernet franc (“cherry floral, herb, watermelon, and nectarine”) which Wine Spectator rated 87.

Danielle Kane, a Rochester native now living outside Frankfurt, Germany, pronounced them “very good” on a recent visit as she sampled flights with a friend. “I appreciate dry wines. These meet the German wine region expectations...It was worth the drive.”

The Road More Traveled

That farmland the Martinis visited in 1973 had never grown grapes, but the soil was of a type known as honeyoye, high in lime, well drained, ideal for grapes. The climate was moderated, too, by the presence of Seneca Lake two-thirds of a mile away. And so, with a five thousand dollar loan from his father, they bought a hundred acres—unaware the location of their Martini Vineyards had linked them to an epic moment in American history.

They wouldn't remain unaware for long.

Martinis continued from page 7

Courtesy Anthony Road Winery

Wade Spencer

Mother Grows Best

continued from page 8

On the night of February 15, 1898, the US battleship Maine was docked in Havana Harbor when an enormous explosion ripped off its bow. The sinking ship was instantly plunged into darkness, forcing its captain, Charles Sigsbee, to feel his way out of his cabin toward the quarterdeck.

But as he groped blindly down a rapidly tilting passageway filled with smoke he collided with someone coming towards him. Private William Anthony had rushed into the ship to inform his captain that their ship had been “blown up,” and escorted him to safety. Both survived, but two hundred and sixty crew died that day. Believing it to be sabotage, America declared war on Spain.

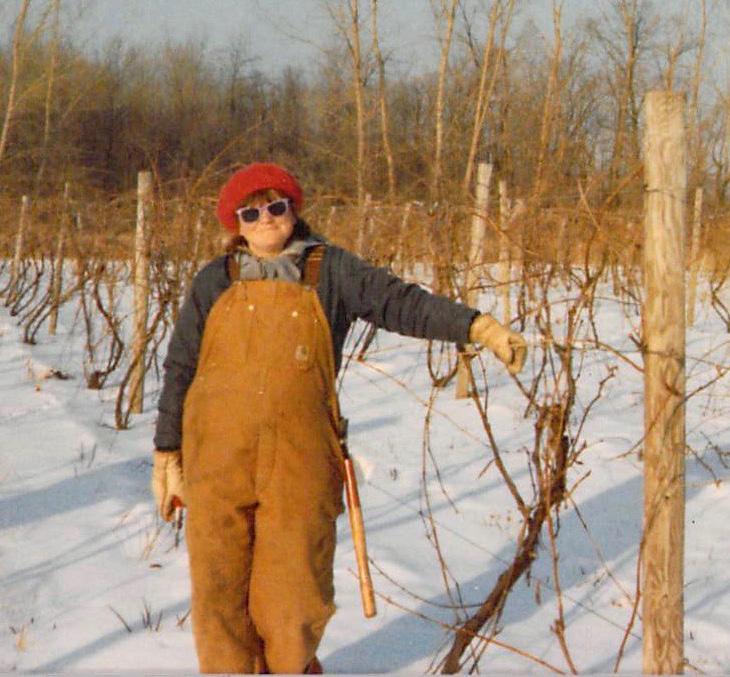

Ann (top) trims Aurora in 1989; the four Martini kids at their new house in 1977; and Ann gets a workout with their first press in 1989.

Captain Sigsbee never forgot Anthony’s “soldierly conduct.” Instead of fleeing to safety on that “dangerous occasion,” the forty-five-year old had chosen to “fulfill…the precise duties of his position,” he wrote to the Secretary of Navy, and recommended Anthony’s promotion to sergeant.

Hailed as “the nation’s hero,” Anthony fought in the Spanish-American War aboard another ship, retired with the rank of sergeant-major, and died in New York City the following year.

The Navy would name two destroyers for him, and Penn Yan would name a road for him.

John and Ann—who could relate to Anthony’s plunge into the unknown—would one day name their winery in his honor.

Grateful for Grapes

The vicissitudes of farming, meanwhile, would reveal themselves almost as soon as John and Ann rolled a repossessed, three-bedroom trailer—with no plumbing or electricity—onto their then-houseless property. Grape seedlings take two to three years to mature into fruitbearing vines, they discovered, and that meant John—a trained chemist—would have to find some other source of income.

(3) Courtesy Anthony Road Winery

And so, as he started testing animal feeds and fertilizers for the New York State Agriculture Experiment Station at Cornell, Ann began the laborious task of hand-planting five acres of the red grape variety known as marechal foch for which Taylor Wine Company had contracted. “Nine feet between rows,” he recalls, “and six feet between the vines.”

The future of grape growing looked bright back then. Taylor was the sixth largest winemaker in the country, and public thirst for their sweet wines seemed unquenchable. Best of all, Taylor paid well, and soon—with the help of an automated planter—the Martinis were growing thirty acres of foch, aurora, seyval blanc, vignoles, and DeChaunac. These were French-American hybrid varietals to which the Taylor Company added abundant sugar to produce inexpensive wines high in alcohol.

“Cornell allowed us to make it week to week,” recalls Sarah, “and the grapes paid the mortgage” on the house they built.

Indeed, Taylor’s future looked so bright that the Coca-Cola Company bought it in 1977—only to discover that the public’s appetite for their sweet, syrupy wines was drying up. As sales tumbled, Taylor was forced to scale back grape buying, and grapes that once sold for four hundred dollars per ton now fetched just a hundred. By the early eighties, dozens of Finger Lakes growers who’d relied on Taylor were plowing under their vines or scrambling for new markets.

Ann, by now the mother of four, found herself driving grapes to the wineries at the far end of Long Island—a seven hundred-mile

Martinis

round trip—and selling juice to home winemakers who knocked at their door.

“There was a lot of stress and strain in those days. I can remember my mother having to stretch twenty-five dollars to feed a family of six,” says Sarah. “But they weren’t the type of people who gave up.” And wine growing in the Finger Lakes was undergoing a sea change thanks to the vision and persistence of one man.

Dr. Frank

For more than a century, Finger Lakes winemakers had supposed the region too cool to grow the superior vinifera grapes of Europe like chardonnay, riesling, gewurztraminer, pinot noir, and cabernet sauvignon—hence their reliance on budget-friendly sweet wines.

Then, in the 1950s, a young viticulturalist from Ukraine arrived on the scene. Dr. Konstantin Frank had grown vinifera grapes in regions of the Soviet Union far colder than upstate New York, and was emphatic they would prosper here. He was greeted with much skepticism until Gold Seal winery invited him in 1958 to grow a demonstration crop. It met with such success that in 1962 Dr. Frank launched his own winery on Keuka Lake—and with it a wine revolution in New York State that would gradually topple the Taylor Wine Company.

“If Taylor had not failed,” says John, “this industry would not be here the way it is. You either got out or you got deeper.”

And the Martinis might have walked away in these difficult times had not their friend Scott Osborne, owner of nearby Fox Run Winery, mentioned in 1987 he had 1,500 riesling “sticks,” or seedlings, that he could not use. Did John and Ann want any? A few of their Seneca Lake neighbors, including the Hermann J. Wiemer winery, had just begun making riesling with notable success. The Martinis took all Scott had to offer.

“It was a really good decision,” says John. “They grew beautifully. Rieslings would go on to take Finger Lakes wines out to the world—to establish our reputation.” In short order they began planting more vinifera grapes, like chardonnay, pinot gris, cabernet franc, and pinot noir. Their biggest leap would come in 1989, as John sat at a local tavern with his friend Derek Wilber, a young winemaker then working at Widmers Wine Cellars on Canandaigua Lake.

“Over a beer in a bar is always a good place to make a life-changing decision,” John jokes. “But Derek knew how to make good wine and put it in a bottle. So I said, ‘Why don’t we start a winery?’ And that’s what we did.”

A Little Labor Intensive

Their first “cellar” was a renovated machine shop, where they parked four oval, stainless tanks from a scrapyard in Newark, New Jersey, that once held fragrances for Colgate-Palmolive. That fall, with a few hired hands, Ann helped pick twenty tons of grapes. She then crushed them with a hand-cranked apple press, layering the grapes between cheesecloth and squeezing the juice into tubs underneath.

“It’s fun to talk about now, but wow…” says John. “I used to tell her she should have stuck with her first boyfriend.”

Ann shakes her head fondly at the memories. “I would take the cheesecloth to a laundromat at night so no one would see me.”

She still helps out in the tasting room as needed. She and Derek earned little or nothing those first years—their employed spouses brought home the only paychecks—but not for lack of labor. In addition to tying and pruning vines with whatever help she could find, Ann was also head of sales, this in the days before the internet, email, and cell phones. She drove around the region with sample bottles, coldcalling wine stores.

“She’d look them up in the Yellow Pages,” Sarah recalls.

They produced 2,000 cases in 1990, with grand visions of one day reaching 70,000. But in thirty-five years they’ve never produced more than 20,000, and even that was a challenge.

“It’s one thing to produce that much,” explains Sarah, “but then you’ve got to sell it.”

Martinis continued from page 11

Wade Spencer

A Taste of Grapeness

Tasting room manager Liz (left, standing) chatting with patrons Cynthia Keller (left, seated) and Joe Abel from Upper Black Eddy, Pennsylvania, while tasting room flight attendant Gate Hathway serves a pinot noir and a cab franc.

Changing Tastes

With Finger Lakes wines enjoying newfound prestige, new wineries sprouting like weeds, and “wine trails” forming around Cayuga, Seneca, Keuka, and Canandaigua Lakes, tourists became an increasingly important source of revenue for Anthony Road and others.

“In the early days nobody charged for their tasting bars,” says Liz, who manages the tasting room. “You’d have a tasting sheet, and some people would take their time” to savor. But then began the tour buses, whose passengers were often out for the free wine. “People would just sit at the bar and stick their glass out. It really took away from what we were trying to do.”

Despite growing recognition of their wines’ quality, it was an unpretentious, semi-sweet wine called Tony’s Red, initially selling for six bucks, that originally proved their biggest source of revenue. In that first decade they also started a distribution company, Finger Lakes Premium Wines—essentially a cooperative—that marketed the wines of a half-dozen wineries before it was bought out by Opici, a leading wine distributor.

“So we did OK. We never went on food stamps,” says John, who quit working for Cornell’s Experiment Station in 1998. That freed him to take an ever-expanding role representing the region’s wineries and grape growers in Albany and Washington, DC.

“I didn’t lobby,” he says with a wink. “I educated.” He would become president of both the New York State Wine Grape Growers Association and the Wine Grapegrowers of America, chairman of Na-

Planet of the Grapes

Shaking Things Up in Wine Country

By Terence Lane

We know what a bartender makes, but what makes a bartender? Hear from three creative bartenders in Watkins Glen.

What brought you to bartending?

Indiana: “I was raised in restaurants, so the chaos of expo lines and Saturday nights always felt like home to me. I didn’t become a bartender until about six years ago when I was encouraged by coworkers who thought I had the skills and personality to be successful. I’ll always be grateful to them for that. I began to truly enjoy myself. I think joy in work is a unique thing to find.”

Ian (above): “In my teens and twenties, I was a hothead and very opinionated. Very controversial. I didn’t think I had the patience for working with the general public. But then I worked for the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum as an interpreter on this roving circus of tours on a canal system. I did a presentation about the War of 1812 and told the history of the boat. Hundreds of people did the tour. That job made me realize that I can deal with the public, I can speak publicly, and that I’m not afraid of this. Bartending just kind of fell into my lap after that. The girl I was dating worked for a restaurant and they needed help at a catering gig. I was in charge

of making three cocktails and thought it was pretty interesting. Eventually I found my way to 29 Neat [at 29 North Franklin Street], and that’s where I really cut my teeth on cocktails.”

Terence: “My sister connected me with winemaker Jeff Dill, who was opening a bar in downtown Watkins Glen [J. R. Dill Wine Bar, 301 North Franklin Street], and we hit it off. We had a similar vision and he was trusting enough to give me free rein. I remembered the great cocktail bars I frequented when I was living in Queens, and wanted to do something similar. Just really high-quality cocktails that look and taste amazing. Everyone posts pictures of their drinks, so they always have to

Terence Lane

look incredible. I’d been working exclusively with wine before, so running a cocktail bar was a chance to do something new and refreshing.”

What’s the best thing about bartending?

Ian: “I appreciate when you have the ability to do something new and unique. Some bartenders look at uncertainty as a burden. For the most part, I look at that as an opportunity to evolve. That’s what it’s all about. Helping people find something to drink that they didn’t even know they liked. I can tell within the first second of the first sip if they liked it or not. Their eyes light up. There’s the flush of the face. Some people just let out a sigh and slowly nod their head. You can tell instantly. It’s completely nonverbal.”

Indiana: “I love making new drinks and spending time with my regulars [at El Rancho, 212 North Franklin Street]. Some of the greatest friends that I’ll have forever are those I’ve met while bartending. But finding new ingredients and flavors to work with, that’s when I feel like I’m creating art.”

Terence: “I get to hang out with my friends and try out new jokes all night long. I get to talk to girls, and I get to be myself. I see young people in their twenties working in drug stores and car washes, and I always wonder why they wouldn’t want to be bartenders instead. I’m basically always looking around wondering why everyone isn’t bartending. It’s a great way to make a living and it’s so much fun. I genuinely love making cocktails.”

What’s something you wish people understood about bartending?

Ian: “A drink is only as good as its ingredients, and curated cocktails have the ingredients they do for a reason. Sometimes people want to make substitutions, which is okay, but now I don’t know if that’s going to taste good. It could lead to an unsatisfactory experience, and that’s the last thing I want. Moral of the story—just let me make the cocktail how it’s been designed and chances are you’re going to love it.”

Terence: “What Ian said. Some customers get so fixated on one ingredient they don’t recognize and end up denying themselves the experience of having an experience. I run an ambitious cocktail program with only New York spirits, and I realize it might be intimidating. Customers are going to see a lot of bottles they’ve never seen before. It’s okay to ask questions and have a conversation, but it’s important to keep an open mind.”

Indiana: “I wish people understood that bartending is a performance. The personality, the swagger, and the bar flare, it’s all for entertainment purposes. I can’t speak for every bartender, but I’m certainly a bit different outside of work. Running into regulars outside of the bar tends to be amusing. It’s fun when they see how surprisingly calm and quiet I am outside of that environment.”

Terence’s Alpine Mule:

Combine 1 oz. vodka, .5 oz. Fernet Branca, 1 oz. fresh lime juice, and .5 oz. simple syrup in a collins glass filled with ice. Top with ginger beer. Garnish with a lime twist and candied ginger. Cheers!

Terence Lane is a Certified Sommelier. His short fiction and wine writing has appeared in a number of magazines including Wine Enthusiast. A native of Cooperstown, New York, he now lives in the Finger Lakes and is the beverage manager at J.R. Dill Wine Bar in Watkins Glen.

WATKINS GLEN

Don't Run with Stemware

The start of the 2024 half-marathon had strict rules against wine-ing—until the race was finished, of course.

A 26.2-Mile Block Party

Guthrie Wineglass Marathon Makes the Run Fun for Everyone

By Phil Hesser

Following the Wineglass Marathon in 2010, local leaders and organizers

Chris Sharkey and Sheila Sutton knew there was room for improvement. “The race was a gem—with much more potential,” recalls Sheila, now WGM race director. The race had a big impact on businesses.

Chris notes, “If the race faded away, it would affect the community.” And not in a good way. So, there were things that had to change. Law enforcement, fire/EMT, and volunteers from several organizations were winging how they made assignments, and management across the groups wasn’t coordinated. In 2011 WGM was refreshed. It became a separate 501(c)(3) with Chris as board chair. She says their plan was to, “up the ante as an economic driver and the very best running experience”—a vision that would benefit everyone. Guthrie signed on as title sponsor in 2017, with 2018 being the first year of the official name change to Guthrie Wineglass Marathon.

The greatest benefit extended to the volunteers. Organizers were there for all the support people—briefing them beforehand and thanking them afterwards. A safety committee coordinated traffic and fire/EMT. “Captains” became the go-to people for the hundreds of volunteers interacting with the runners. The spirit of the race became infectious for runners and support people. Vol-

unteers made the water stops into carnivals with signs, music, and costumes.

“We had to waitlist organizations who wanted to join in the fun,” says Sheila.

Sharing in the fun were people who now have supported the race for a decade or more. Impressed with everyone’s “positive energy,” Steuben County Sheriff Jim Allard meets the runners minutes after the start, sweeping away their jitters by telling them, “You’re almost there” and giving them highfives just before the halfway point at Savona. When she ran the race, Corning-Painted Post School Superintendent Michelle Caulfield was amazed at the support people “who wanted to be there,” and decided to volunteer at the start, adding that volunteer students and staff are inspired by the runners who “conquer something that’s not easy” and pay volunteers back with their own infectious energy.

Speaking of paying back, Chris recalls, “We were going to give back to our volunteers.” One fire company received funding for a four-wheeler to support runners on roadless sections. By using the online runsignup.com, runners directly donated to four charities, including scholarships for local track athletes and other students who were key race volunteers.

These changes made WGM run full circle, reaching across the community. Chris

quantifies the impact: Over $1 million in donations since 2011 going to fifty nonprofits who help with the race; more than $7 million in spending by 6,500 runners and their 15,000 friends/families during the marathon weekend in 2024.

Last year, six women from the 2024 USRowing Olympic roster ran the halfmarathon, reuniting two months after the Olympics.

“The Wineglass half-marathon for me was an opportunity to celebrate our team, the small moments, and the shared love,” says Jessica Thoennes, who finished fourth in Paris in the women’s pair. “It’s a gift in this lifetime to find friends who will get up at 3 a.m. to go compete for fun. The fact that the entire town of Corning celebrated with us is joy beyond words for me.”

The race starts at 8:15 a.m. in Bath on October 5 and ends on Market Street in Corning. Visit wineglassmarathon.com for more information.

Having completed a few hundred marathons and ultramarathons over nearly 30 years, Phil Hesser still jumps—if you call that jumping— at the chance to do the distance at a great event. Look for him this year, hobbling near the end of the pack and whooping it up on every mile.

GAFFER DISTRICT

Jackassing Around

Owners Skip Kratzer and Larry Winans (lower right, l to r) are kicking it at their brewery with two locations: Lewisburg (above) and Williamsport (left).

A Brew-Hee Haw

Jackass Brewing Is Kicking It in Lewisburg and Williamsport

By Melissa Farenish

The names of the menu items, the beers—Mother of All Cluckers, the Cobbfather, and Whoop Ass—and of the business itself add to the edgy and irreverent vibe at Jackass Brewing Company. The restaurant, which has locations in Lewisburg and Williamsport, offers creative food and a variety of beers, and keeping things lighthearted and fun is part of the M.O. Owners Larry Winans and Skip Kratzer have learned not to take anything too seriously.

“We want people to come here and have fun,” Larry says. He and Skip are firm believers in the adage posted on their business homepage (jackassbrewingcompany. com): “You don’t stop having fun because you get old, you get old because you stop having fun.”

“We’re actually kind of boring, honestly,” Skip says. “I’m a former schoolteacher, and he was a dentist.” The pivot to beer brewing began more than seven years ago during a weekly outing with friends.

“We used to go out for beers, usually Friday afternoons,” Larry recalls. “Then Skip came up with the idea one day to brew our own beers.”

Skip had already dabbled with home brewing. Larry, who majored in chemistry in college, began brewing on weekends with his pal. The results at first were not always favorable. “We learned a very important lesson while doing it, that one should not drink bourbon while brewing bourbon porter,” Larry says with a laugh.

The two spent the next few years dedicating themselves to the art of beer brewing. By March of 2020, they were ready to take the plunge and open their own brewery in Lewisburg. They chose the name “Jackass” partly because they wanted to keep things light but also because the jackass has a strong work ethic.

“The characteristics of a donkey are stubborn, strong-willed, determined, hardworking, loyal, and faithful. That’s us,” Larry says.

But, talk about a kick in the, well, you know, the brewery’s opening was just five days before the covid pandemic shut everything down.

“When we started the brewery in Lewisburg, we were about sharables,” Skip says. “We wanted to have sharable foods and have people together at tables. Covid changed that for a bit.”

The Lewisburg location has large pullopen garage doors, though, which helped to keep Jackass Brewing Company afloat during the pandemic restrictions. Word got out that a new brewery had opened in the area, and customers started coming to the open garage doors for takeout beers. It seemed Larry and Skip’s mission to bring people together was fulfilled after all.

“People were able to see their friends and neighbors in the parking lot as they waited for their beers,” Skip says.

Eventually, restrictions eased, and the Jackass team got to work developing a food menu consisting of offerings with a creative

twist. The Mother of All Cluckers chicken sliders is one of the most popular, Larry says. The sandwich recipe takes fried chicken and adds unusual ingredients, including cheesy mashed potatoes, waffles, and whiskey maple syrup. “That was a take on central Pennsylvania chicken and waffles,” Larry explains. “We have some creative chefs who take a twist on the menu items and say we ‘jackass’d it up.’” Other menu items, such as This Little Piggy Went to Wilpo, take traditional pulled pork and dresses it up with pineapple salsa, chipotle BBQ, and cotija cheese.

Of course, a meal at Jackass wouldn’t be complete without one of the twelve beers currently offered on tap. Skip and Larry come up with the recipes to brew a variety of beers, including darks and lights, IPAs, sours, and the recent addition of a farmhouse saison.

The names of the beers the Jackass crew brews are just as creative as the food names. Beers such as Dumbass Porter, Foggy Doo (a New England style IPA), and Wonkey Donkey (a Belgian Tripel) are staples on the roster.

“We like to say we have a beer for everyone,” Larry says.

“We just brewed our first ever pumpkin beer, Jacktoberfest,” Skip adds. “We took an Oktoberfest and Jackass’d it up.”

One of the most recent business ventures for Jackass has been hosting events at the Lofts at 301 West 3rd, the third floor of their Williamsport location. The 28,000-square-foot building has four floors, two of which are dedicated to hosting events such as weddings, corporate parties, baby showers, bridal showers, and the like. Last November, the Lofts hosted a holiday market. This fall, the Lofts will host a bridal expo in October and a second annual holiday market in November.

Although the Williamsport location has been around for only a year, it already has a following. Larry and Skip like the Williamsport area, and thought it would be a good second location, with the advantage of being close to their Lewisburg home base.

“There’s a real sense of pride in the community and that’s what we’re about,” says Larry. “And that’s one of the reasons we picked Williamsport.”

The two say they have built a good team at both locations. The Williamsport crew was put to the test recently during the Little League World Series in August. More than sixty players and families of the Las Vegas Little League team came in one night. “Our entire team stepped up to the challenge that night,” Larry notes. The Jackass staff made people smile, and that makes the owners happy.

“Smiles—that’s always been a big part of what we are about,” says Skip.

Enjoy a brew and a meal at the Jackass Brewery Lewisburg location, 2268 Old Turnpike Road, or in Williamsport at 301 West 3rd Street. For menus, reservations, and booking events at the Lofts, call (570) 980-1083 or go to jackassbrewingcompany.com. And watch for the rooftop bar coming in the summer of 2026.

Melissa Farenish lives in Montoursville with her husband, Sean, daughter, Nadia, and two cats. She’s been writing for publications since her college days at Penn State University, and has written for community newspapers in Williamsport and Sunbury. She enjoys music, traveling, and the outdoors.

Tapping into Community

People have a new way to let their imaginations take flight thanks to Paul and Stacy Richmond (left) and their payby-the-ounce approach that Steve Shutt of Lawrenceville enjoys during the taproom's one-year anniversary.

Latitude 42

Horseheads’ Answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything

By Kelly Stemcosky

If Stacy and Paul Richmond have learned anything through twenty-nine years of marriage and one year as business partners, it’s that friends, connections, and memories matter most. Those three words are the motto stamped above the door of Latitude 42 Taphouse, which just celebrated its first year of business in Horsesheads, and, as Paul says, “that’s what we believe in.”

“That’s our mission,” he adds. “We’re not here just to pound beers down.”

“The community has been overwhelmingly supportive. We’ve reconnected with old friends, and we’ve met so many new friends,” says Stacy.

The anniversary celebration on Saturday, August 30, started in the afternoon with an employee-only gathering, but then those old and new friends started trickling in, then pouring in as the night progressed. Many floated from table to table, from indoors to out, convening around the self-pour taps that make Latitude 42 so distinctive.

The self-pour, pay-by-the-ounce model

isn’t widely seen in the Twin Tiers, but the Richmonds say it’s been welcomed with open arms and empty glasses. The concept is simple: tap, pour, drink, and pay. Selfpour gives patrons the power to sample as much—or as little—as they’d like, with glasses of all sizes and shapes, and options to make your own flights.

Taps at Latitude 42 are grouped in threes, with a screen above each displaying the name and pertinent info about each libation. After obtaining a tap card—the card keeps track of the ounces you pour—at the front desk, choose your glass, tap the card against the pad above your selection, angle your glass, and pull the tap. Pour just a sip or an entire glass—the choice is yours, because you’re your own bartender.

The selections change with the seasons, with recommendations from their distributors, or from Stacy and Paul, based on their travels around the country and formations of new partnerships. They try to have something for everyone—from cider, wine, and

beer, from the darkest stout to the lightest blonde ale, locally crafted, imported, and domestic, and non-alcoholic selections. Included in the twenty-four currently available are well-known Miller Lite and Guinness, local seasonal brews like 1911’s Cider Donut, and Stacy’s personal favorite, Kentucky Vanilla Barrel Cream Ale by Lexington Brewing & Distilling.

“You’ve got to try this,” she says, whipping out her own tap card, her face lighting up as if she’s about to let a new friend in on her own little secret. The medium-bodied ale swishes into the glass, and when it’s pulled back, a perfect, slightly foamy head rests on top like a crown. The first taste is what one might expect from a barrel-aged ale with vanilla notes, but the aftertaste is what earns it the title of a bar owner’s favorite. It’s like a smoky vanilla breath mint, not too sweet or overpowering, but with an unexpected burst of flavor after the liquid is already down your gullet.

Kelly Stemcosky

“I feel like it makes my breath smell good,” says Stacy with a laugh, happy that she’s converted yet another person. It’s just one of the brews she and Paul discovered on their various trips, which also influenced the concept of Latitude 42.

Pennsylvania Lumber Museum

“Our daughters both played travel softball, so we’ve traveled to a lot of places around the country, and this was something a little bit different than we’ve seen,” says Stacy, adding that they’ve visited self-pour establishments in Atlanta and Charlotte, with the closest being in Owego. “We wanted to think of something that we could do in retirement. We wanted to do something where we could give back and make it a place for the community.”

5560 US Route 6 West , Potter Co. (814) 435-2652 lumbermuseum.org

While the Richmonds are still working full time, both in education, they couldn’t pass up the perfect location when it came on the market last year, 467 Old Ithaca Road, Horseheads. Its latitude is, guess what, 42.

“We live right up the street. I saw the building was for sale, so we jumped on it. It was a perfect point in our life where we’re now empty nesters. It was just something that came about with the encouragement of the community and our neighbors and friends,” says Stacy.

In return, the Richmonds are using their venture to give back. In June, Latitude 42 hosted a cancer walk to benefit the Falck Cancer Center patient care fund, which, as a cancer survivor, Stacy says was near and dear to her heart.

“We had such a great turnout. We did three different walks throughout the day, just around the neighborhood for a mile. We also had Blush Salon come, and we just really celebrated survivors but also celebrated the lives that we’ve lost,” she says, adding that they’ve also collaborated with fellow Old Ithaca Road establishments Horseheads Brewing Co., Sonny’s Bar and Grille, and Nick’s Bar and Grille to host a Shamrock Shuffle, SantaCon, and Christmas in July events to raise money for the local food bank, cancer center, and the Chemung County SPCA.

by Michael L. Goodman

Latitude 42 also hosts weekly trivia nights, workshops, and, new this year, it’s a certified Bills Backers bar, and will be open for all Buffalo Bills football games. The space is available to rent for gatherings and is kid- and dog-friendly, with furry visitors even getting their own selection of NA all-natural dog beer, wine, or pup cups.

“We don’t really think of ourselves as a bar or a taphouse,” says Paul. “It’s more like a community center.”

Latitude 42 Taphouse is open Tuesday 5 to 9 p.m., Wednesday 4 to 9 p.m., Friday 3 to 9 p.m., Saturday 12 to 9 p.m., Sunday 2 to 8 p.m., and closed Monday except for special events. For the most up-to-date info, find Latitude 42 Taphouse on Facebook or call (607) 526-5242.

Kelly Stemcosky is an award-winning writer who works as a newspaper page editor/designer. A Tioga County native, she spends most of her free time volunteering for animal-related causes and hanging out with her family and cats.

Welcome to MOUNTAIN HOME WEDDING

A Kiss of Autumn

Cameron Clemens

Cameron Clemens captured the special day of Mikayla Chilson and Blair Phelps last September in Fall Creek, Pennsylvania.

Top Tier

Whether traditional or experimental, Lisa Fieno executes her customers' wishes with exceptional skill and quality.

Cake Is Her Love Language

Lisa Fieno Elevates Food to Fine Art at The Cakery in Elmira

By Karey Solomon

“Why couldn’t Cinderella play soccer?” asks Chris Fieno as he takes an order. He’s the brother of chef and baker extraordinaire Lisa Fieno. And he apparently revels in the dad jokes he thinks up while his sister creates magic in the kitchen of The Cakery (thecakeryelmira.com or (607) 731-6118).

Because Cinderella’s only got one shoe? “Wrong,” he smiles, as Lisa brings out part of someone’s lunch and he assembles the rest.

The café and pastry shop at 116 Baldwin Street in Elmira—“Look for the red column, and we are in that little nook, second door on the right”—is peaceful oasis across Baldwin Street from the Chemung Canal Trust Company’s home office. On a “quiet” day, a steady stream of customers came for goodies and lunch, many staying to eat inside or at outdoor tables in the courtyard. A group of older ladies chatted over lunch,

and planned to bring more friends to enjoy the chicken salad the next time they come.

The ambiance is relaxed, with quiet jazz in the background, dining tables as well as armchairs with convenient side tables, and Athena, Chris’ polite black cat, napping on the sofa. “I wanted a place that was cozy and welcoming, where you can just sit down, spend as much time as you want, and let the day go,” Lisa says.

There’s a fireplace, paintings, a spinet piano whose music stand holds music and the children’s book Strega Nona, a folk tale about a grandma who feeds infinite amounts of people until all are sated, and then blows three kisses to her magic pot.

Lisa is that kind of grandma. She began making custom cakes for her grandchildren and others. Back then baking was a hobby fueled by occasionally binge-watching the Great British Bake Off. She got ideas, experimented with flavors, added her own

spin, and found people asking her to bake for them. After covid, her custom cake business outgrew hobby status. Lisa used her stimulus check to buy a commercial oven she’s nicknamed “The Beast.” A few years later, to satisfy her taste for creating savory meals (which rivals her enjoyment of sweet desserts), she decided a café would be her next venture. She opened a year ago.

Her take on food is innovative, sometimes experimental, and held to a high standard. “Everything is made from scratch, and every teeny tiny thing someone puts in their mouth here is different,” Lisa explains. For instance, she wants her sweets to have a balance of flavors without being too sweet. Her Kitchen Sink cookie features a chocolate chip cookie base with white chocolate, marshmallow Rice Krispie treats, and the additional crunch of potato chips. Not to stint on decadence, it’s served with her homemade salted caramel sauce. The whole

business is time-consuming to make from scratch, but when she watches someone taste it for the first time, well, “I see the look on their face, and it’s so worth it!”

When a customer arrives for a special-order cake, Chris has her heft the box to feel its weight. “Homemade is going to be heavier than you’d think,” he murmurs, while the customer exclaims, “Oh! It’s gorgeous!”

Cinderella, as it turns out, couldn’t play soccer because she didn’t stay with the ball. Unlike Cinders, Lisa doesn’t lose sight of her goal. Her chocolate desserts are “definitely hardcore,” like the chocolate almond torte, served in generous portions, that’s chocolatey, melt-in-your-mouth creamy, and set off with the mild crunch of an Oreo-cookie crust. It’s gluten-free, might have a million calories, and is totally worth it. When Lisa offered to make a wedding cake for her daughter, this was the bride’s heartfelt request. Lisa is making twenty of these for the celebration.

Wedding cakes might be her favorite things to make. “I love the elegance of wedding cakes, and I love everything about the wedding cake process,” she says. “I’m so excited for the couple when they reach out!” After discussion, she’ll make a sample box, with three mini-cakes in the flavors and icings chosen by the couple from her roster of possibilities.

Many couples come bearing a design inspiration, often a photo, based on a story of their relationship. Armed with that and their feedback on the samples, “I make sure whatever they give me, it’s on the next level. I’m just as excited as they are about the cake. I tell them, ‘You work with me and you’ll have nothing to worry about.’” As for the tradition of saving part of a wedding cake to enjoy at the first anniversary, Lisa, predictably, has a better idea to avoid freezer burn.

“If they order cake for a hundred guests or more, they’ll get a free anniversary cake. I tell them to reach out to me a month prior to the anniversary, and I’ll replicate their top tier for free.”

So far, the largest wedding cake she’s made was for three hundred. Featuring fresh strawberries, it was massive and extremely heavy. “And since it’s just me doing everything and delivering it…” it was an achievement to lift it and get it safely to its destination.

“I love what I do,” she says enthusiastically. “I have so many ideas.” In July, already playing with ideas for fall and holiday menus, she recalled the Christmas carol with the line, “For we all like a figgy pudding,” and was inspired to try a recipe. It called for a lot of breadcrumbs and was, she reports, abysmally disappointing.

She consulted a friend in England who consoled her with, (Lisa repeats with a convincing British accent) “Oh, Lisa, you should have asked me first. That’s for the poor!”

She’s currently working on reinventing a tastier version.

From savory meals inspired by seasonal produce to popular permanent menu items, repeat customers know their best strategy is to come for lunch and stay for dessert. Or vice versa. You wouldn’t want to miss either one.

Karey Solomon is the author of a poetry chapbook, Voices Like the Sound of Water, a book on frugal living (now out of print), and more than thirty-six needlework books. Her work has also appeared in several fiction and nonfiction anthologies.

The Barn at Hillsprings Farm

The ideal setting for any type of special event.

The Barn is the perfect “all-in-one” venue that includes catering! Three packages to choose from with a wide-variety menu. This beautifully restored barn is nestled in the serene hills of ADDISON, NEW YORK two miles north of Elkland, PA

For information or to book your special event contact Amy at (607) 368-5092 or Dorotha at (570) 772-6876.

www.thebarnathillspringsfarm.com

Where friends meet, since 1947

Outdoor Wedding Receptions Rehearsal Dinners Bridal Showers

Spectacular views of the Endless Mountains and Lycoming Creek! 14262 SR 14, Roaring Branch, PA (570) 673-8421 • wheelinninc.com

Wedding and Event Venue with Overnight Accommodations overlooking Lamoka Lake

Email: events@luxehomeandleisure.com Website: luxehomeandleisure.com

A Marriage of Health and Beauty

Stylist Amelia Sousa does a bridal trial hairdo for bride-to-be Haley, while Grace Holistic owner Stephanie O'Sullivan watches.

Comb By It Naturally

Grace Holistic Keeps Calm and Carries on in Painted Post

By Carolyn Straniere

What if there was a salon that catered not only to making your hair look and feel great, but included helping your body and spirit do the same? And did it naturally? Enter Grace Holistic Beauty and Wellness, located at 240 S. Hamilton Street in Painted Post. Owner Stephanie O’Sullivan, a hairstylist with over twenty years of experience, envisioned a beautiful space dedicated to marrying self-care and style holistically, then made it a reality.

“I saw the need for more natural products after I developed sensitivities to color and other products over the years,” Stephanie explains. “I went down the rabbit hole of ingredients used in traditional products and was shocked by what I found. Many commercial hair and beauty products on the market have harsh or toxic ingredients, and some of them are hormone disruptors.”

Knowing she needed an alternative solution, Stephanie looked into how a holistic practice might be the answer. “I knew I couldn’t be the only one with these sensitivities,” she says. “I had to do better, not only for myself but for my clients and staff.”

Stephanie, an Addison native, began looking for clean salon options. In 2021, a storefront became available on Corning’s Market Street, and Grace Holistic Beauty and Wellness was born.

“My goal was for the salon to be more than just a place to get your hair styled. I wanted to incorporate every aspect of wellness, and to nurture beauty from the inside out, naturally,” Stephanie says. “I think it’s important for our clients to know there’s a better way to overall health, especially in the beauty world.”

Starting with a small staff, the stylists at Grace Holistic provided a wide array of services using a combination of natural products designed for each client’s individual needs and hair type. The offerings included cuts, styling, color correction, natural hair care, and strengthening. As the clientele base grew, an independent skin care specialist was added, then a massage therapist.

In the spring of 2025, Stephanie and her husband, Tony, purchased the former Community Bank building in Painted Post. They moved to the new space over the summer.

“We have more room now,” says Stephanie. “We’ve been able to increase the independent wellness practitioners and stylists here.” Among the new additions are an esthetician, providing the latest in facials and derma-planing, a make-up artist, and a hair extension specialist. “We also have a specialist who handles hair loss and thinning of the hair. We offer consultations, treatments, repair, and analysis for those facing this condition.”

Grace Holistic also offers the Grace Bridal

Company, a team of professionals dedicated to bringing your wedding day dreams to life. You can choose Grace Holistic’s beautiful space for yourself and your bridal party to have hair and make-up done, or the team can travel to your location for the big day. Whichever service you choose, Grace Bridal Company will help you look and feel your best.

Massage has been a staple of offerings since the Market Street days, and continues in the new digs. The goal is to create a calming environment designed to leave clients relaxed and renewed. A variety of massages are available, including Swedish and prenatal. No time for a full body treatment? Opt for a mini massage.

For more information or to schedule an appointment, call (607) 973-2153, email graceholisticbeautywellness@gmail.com, visit graceholisticbeautyandwellness.com, or follow them on Facebook.

Born in the Bronx, Carolyn Straniere grew up in northern New Jersey and has called Wellsboro home for over twenty-eight years. She enjoys spending time with her eleven grandchildren and traveling whenever she can. Carolyn lives with her four-legged wild child, Jersey, and dreams of living on the beach in Italy in her old age.

Wade Spencer

Carving a Name for Himself

Pumpkin Master Eric Jones Will Light Up Corning’s Centerway Square

By Dave DeGolyer

Spend some time watching Eric Jones transform a pumpkin into a sometimes spooky, always creative, work of art and you’ll start to understand why he is so popular. It’s not merely his prodigious skills as a 3D sculptor, but his affinity for children and his passion for inspiring them to pursue their own creative interests that are special.

For Eric, pumpkins are a medium that allow for temporary creative expression and act as a connector of sorts, a way to captivate and hopefully inspire others to try their hand at art. He engages his audience, especially the young, often encouraging them to give it a try and imparting a technique or two.

Halloween and other fall traditions such as dressing in costumes and carving jack-o-lanterns stretch back centuries to the ancient Celtic harvest celebration of Samhain and to Irish folk tales, like “Stin-

gy Jack.” While pumpkin carving is now a widespread American tradition around Halloween, pumpkins have not always been the objects being carved. In Ireland and Scotland, folks would carve scary faces into turnips, while in England they often carved large beets. When immigrants sailed across the Atlantic, they brought with them those tales and traditions to the new continent where pumpkins were abundant (they are native to North America and were vital to the Indigenous people).

Eric’s origin story as a master pumpkin carver doesn’t go back quite that far, but it did begin in middle school. It’s probably no surprise that a man who has spent nearly three decades as a caricature artist, drawing over 300,000 people at live events, loved to draw as far back as childhood. What might be surprising, however, is the inspiration Eric found thanks to a teacher. But it wasn’t from being praised for his talents. One day

a teacher discovered Eric sketching and told the boy to “find something constructive to do.” The admonition resonated with Eric, but likely not in the way the teacher had intended. After all, why couldn’t he pursue a career that allowed him to do the thing he loved? Why couldn’t art be constructive?

Eric became motived to not just establish his own career through art, but to share that inspiration with kids. “To push themselves,” he says, “and to look at careers that inspire them. Through artwork you can do just about anything in this country. I want to let them know that art is relevant. It’s not just math, science, and engineering that are important. We are a nation of innovative people.”

One might ask, of all the artistic media available to use as a canvas for creation, why pumpkins?

“I have been a 2D artist my whole life,” explains Eric. “I got into pumpkins

(3) Courtesy Eric Jones

Eric Jones has mastered pumpkin carving and inspiring others to pursue their creative talents. Gourd Times

about eight years ago to hone my 2D skills and fell in love with 3D sculpting.” After he’d been at it for a while, he sent a carved pumpkin to Al Roker on the Today Show, which caught people’s attention. Soon Food Network invited him to try out for the show Halloween Wars. He made the cut (yup, pun intended) and participated on the show. Later, he won the third season of Outrageous Pumpkins

The celebrity status that came from those shows has lended itself to Eric’s credibility and reputation. In 2023, he expanded on the level of his work by carving the world’s largest pumpkin (which weighed 2,749 pounds before he started cutting). Imagine how many mischievous faeries and spirits that jack-o-lantern might have warded off.

That Guinness World Record and his streaming success have afforded Eric the chance to travel around the country and meet the top growers, so that he is able to procure the largest pumpkin grown each year and carve it.

But what is it like spending time creating art that isn’t going to last? Unlike a marble or bronze sculpture in a museum, or the stone or wood carvings that adorn parks and town squares, Eric’s mediums are primarily pumpkins, snow, and sand, which rot, melt, or wash away. For him, the ephemeral nature of his work adds to the appeal.

“All the work is temporary,” he says. “It’s about process more than the product. When you create something temporary, there’s an urgency to see it.”

Eric often uses the transitory nature of his creations and that sense of urgency to engage in philanthropy. Sculpting For Smiles, a nonprofit he founded, is intended to bring a smile to children who suffer from health issues.

“I try to bring smiles to kids themselves,” says Eric, “so that for a little while at least they might overlook their struggles.” He finds himself creating for sick or injured kids, as memorials or fundraiser foundations in the names of those who have passed away.

“I go to their homes, school, hospital and will make a sculpture of anything they like,” he adds. “There is often a mad rush to come and see it and get a photo with it, which creates an opportunity to raise funds for the child.”

A lifelong Buffalo Bills fan, Eric has also gained a reputation for his snow and sand sculptures related to the team, and has made himself a staple of the Bills Mafia. As a result, he often works with several Bills players, their charities, and the organization. He has a number of sand and snow sculpture activities planned for the upcoming season, including a sand sculpture for Dion Dawkins’ charity.

Throughout October, Eric will be traveling the country carving pumpkins. He buys around 1,000 each fall to sculpt for personal projects, for organizations, and events like Corning’s Days of Incandescence (daysofincandescence.com), October 23 through 25. He’s scheduled to be creating something amazing in Centerway Square from 2:30 to 6:30 p.m. on October 25. Learn more about Eric at ericjonesstudios.com.

September 15 - November 29

Discover Historic Wellsboro & Beyond

Hop aboard Tony’s Trolley for a charming ride through Wellsboro’s gas-lit streets and rich history. Take in iconic architecture, fascinating stories, and breathtaking views of the PA Grand Canyon.

Planning a special event? Our trolley is perfect for birthdays, weddings, and more! Experience vintage charm, adventure, and unforgettable memories with Tony’s Trolley Tours!

A reluctant reader in his youth, Dave DeGolyer became a writer, of all things, with a day job that allows him to share stories about the Finger Lakes region. Contact 570-723-7777

It's a Great Pumpkin, Charlie Messina

Display Misty for Me

Mike Ritter’s Giant Pumpkin Is Ready for Her Close-up

By Lilace Mellin Guignard

In Mike Ritter’s backyard in Blossburg, a twenty-by-sixty-foot area is covered with pumpkin vine. Yes, just one vine, spread out from a thick, light brown main stem in the middle of the 1,200 square feet that is mostly verdant and leafy. The exceptions are the area immediately surrounding the central stem (September’s forty-degree nights caused the oldest leaves to dry out), and Misty, the huge, golden-orange, unblemished pumpkin lying on her side on foam squares.

“All pumpkins are female,” Mike smiles, “but not all females are pumpkins.” The reason, he says, is that pumpkins carry the seed inside them. Almost every year since 1997, he has nurtured a giant pumpkin that, in early October, he takes to be weighed and compete with other pumpkins. This year, for the first time, it is coming back to Tioga County. Usually, he sells it. However, due to his friend Charlie Messina, chair of the Wellsboro Area Chamber of Commerce’s tourism committee, he’s trucking Misty back to the county seat where she will be on display for locals and leaf peepers to take photos outside the chamber office.

Charlie came up with the photo op idea last fall, and Mike agreed to mentor him in growing his own giant pumpkin.

But there’s a learning curve and lots of luck involved, and, well, rascally rabbits. “A lot of what I do is risk management,” Mike says. So early in the growing season—Mike plants his April 15 every year—when it was clear that Charlie would not be supplying more than some field pumpkins to the display, the plan shifted.

The annual weigh-off is sponsored by the Pennsylvania Giant Pumpkin Growers Association. It moves around every year, but Mike describes it as big fun with lots of anticipation. Folks watch from bleachers as the pumpkins, in order of smallest to largest, get weighed. There can be surprises. Last year, Mike’s contestant, Joy, was ranked in eighth place, but after the weight turned out to be lighter than expected, his pumpkin dropped to thirteenth. “She must have had thin walls,” he says, explaining pumpkins can have walls up to a foot thick. Joy— no slouch at 1,075 pounds—was purchased for a festival in Annapolis.

Mike’s biggest pumpkin so far weighed 1,254 pounds and earned him a ribbon for eighth place. The world record is over 2,600 pounds. “Each seed from a world record pumpkin can go for $300 to $500 each,” he says, “like an award-winning pedigree dog.” Each day unless it rains, Mike waters

Misty with about 240 gallons, using a mix of fertilizer that includes blackstrap molasses. A giant pumpkin can grow fifty to sixty pounds a day. He’ll keep pushing until October 3 when Chad Roupp, from the Blossburg Borough, comes to carefully hoist a padded Misty into the box truck.

Lots can go wrong. Rabbits can eat your vines. A bear can claw or mouse gnaw. Any hole a square inch or larger disqualifies a pumpkin. One year a rope holding one of the largest pumpkins broke as it was being lifted to the scale. It dropped from eight feet, and the crowd gasped. It bounced but didn’t break. “Then it happened two more times but still didn’t bust,” Mike shakes his head. “Ended up weighing about 2,200 pounds.”

From October 5 through Halloween, Misty will be posing for photos on Wellsboro’s Main Street. After that her seeds will be dried and packaged to sell—five seeds for five dollars—to raise money for the Children’s Health Fair in June. With the packet will come a page of instructions for those who want to try their luck. Charlie is already making plans for next year.

(2)

Lilace Mellin

Guignard

Misty, shown here with Mike Ritter (left) and Charlie Messina in her mid-September glory, will be available for photos October 5 to 31 on Wellsboro's Main Street.

As god is my witness, I thought Ground hogs could fly.

A Fog By Any Other Name

By Maggie Barnes

“Five minutes, Mags.”

I glanced up from my typewriter and nodded at Skip. We were working the four to midnight shift at a small radio station in the Southern Tier. I was on the news team, and Skip was the DJ and sports guy.

Small town radio is a very specific lifestyle, and all of us who worked the industry in the ’80s and ’90s spoke the same language. We worked lousy hours in shabby buildings with dysfunctional equipment. We were as poor as church mice during a cheese shortage. Our social life was nonexistent as we worked nights, weekends, and holidays. But it was gloriously fun and interesting. No two days were alike. You might be interviewing a fire chief at a barn fire one day, and doing a piece on the local stock car race the next.

It was the best education I could have

had about my craft. Radio was where I learned to write concisely and how to align facts to get the message across. It was also where I could screw up safely. The stations were always desperate for help, so they forgave you when you goofed. And the cast of characters you encountered were legendary. Small town mayors, business owners, politicians of every shape and size. You really become a part of the fabric of life in the community.

The listeners were a category all on their own. One station I worked for always included obituaries in the noon newscast. After the broadcast one day the newsroom phone rang and an irate woman demanded to know why there were no obits at noon. For the first and last time in my life, I had to say, “I’m sorry ma’am, but no one died today.”

During a summer thunderstorm, the station tower got hit by lightning and we went off the air. The engineer was doing his best, but we were silent for nearly an hour. A listener called to ask why we weren’t broadcasting. Informed of the lightning strike she huffed, “Well, I wish you would let people know when this is going to happen!” I thought, lady, if I could predict lightning strikes I wouldn’t be pulling down $185 a week in this dump.

The night I want to reference was in the fall. I went into the news studio to do the 10 p.m. broadcast, starting with a weather teaser, just a short line about current conditions before the whole forecast at the end of the report. Like all small operations, we used a network for national and world news, followed by the local stuff. In order to hear

Courtesy Maggie Barnes

the network report we had to use a technique called “back timing,” where you gave the station call letters and the one line weather report, and the second you finished the network voice came on. This was back in the day of the almighty sweep second hand. Hit it right, and the broadcast was seamless. Hit it wrong, and it was jumbled and unprofessional.

When Skip gave me the heads up, I glanced at the weather forecast again and memorized what I needed, “Cool tonight with a chance of low-lying ground fog.” I watched the second hand, estimated how much time I needed, and opened my microphone. “Good evening, this is WJTN, Jamestown, tonight’s weather is cool, with a chance of low-flying ground hogs. The news is next.” Triumphantly, I watched the second hand hit twelve, and the network anchor started his report. It was perfect.

Then I looked up through the glass that separated the news anchor from the disc jockey. Skip’s eyes were the size of hubcaps and his mouth hung open. I held up my hands to him in a gesture of what gives? He walked out of his studio and down the hall to mine. I turned down the network feed as he came in and said, “Do you know what you just said?” I scrunched up my face and said, “The weather teaser. So?”

Informed of what words actually came out of my mouth, I sat there stunned. Replaying the moment in my head, I was sure I had said it correctly. But the outside phone rang, and Skip answered to find a listener laughing uproariously. All I heard was Skip’s side of the conversation, including “Oh, yes, she’s very clever,” and “We are so glad we made your day!”

It wasn’t the last such call.

I had to get my wits about me and do the actual newscast, ending with the full forecast, during which I over enunciated “lying” “ground” and “fog.” I really didn’t want some little old lady deciding not to walk her terrier before bed in fear of airborne rodents.

My conversation the next day with the news director and station manager was a little more severe than the gleeful listeners. I was reminded that we do have standards to be professional despite our small size and that I should take greater care in the future. I agreed wholeheartedly.

But my colleagues were not about to let this magic moment go so easily. The next night, as I did the expanded 6 p.m. newscast, Skip ushered in a group of my teammates who got down on the floor and threw a variety of stuffed animals across my field of vision in the hallway. The new improved Maggie, with more professionalism, nearly choked trying to suppress her laughter and still get the words out.

It’s been decades since that foggy night, but it comes back to haunt me via some friends who have elephant-like memories. I can’t predict lightning strikes, and I can’t convince people to die if they don’t want to, but by God, no one is going to be surprised by aerial mammals. Not on my watch.

Maggie Barnes, shown left during her stint working for WJTN Jamestown back in the day, has won several IRMA and Keystone Press awards. She lives in Waverly, New York.

Can You See Me Now?

Smartphones can reveal the northern lights even when not visible to the naked eye.

Auror-Awe

Searching the Sky for Elusive Lights

By Paula Piatt

“Is this the place for the lights?” she asked expectantly.

As if Google Maps had a dropped pin at the magical opening of a space window in Bradford County where you could see the elusive aurora borealis.

“It sure is,” I answered.

I first saw the lights—the dreamlike dancing visions of green and red and purple—as I fought off sleep on a slowly rocking train inching its way over the northern Manitoba muskeg in the 1990s. Was that a blip of green? A moving cloud? A wish so persistent it simply created a picture in my mind? As it often is, the aurora was fleeting. Stepping off the train in Churchill, known as much for the aerial display as for the terrestrial one—polar bears—we were there to see, the sky hid behind a gray flannel blanket for the next five days. Chances since have been latitude-dependent. Trips to Alaska and the Yukon provided some great sightings; unsurprisingly, a Pennsylvania

view eluded me.

But 2024 was filled with anticipation. At the peak of the sun’s eleven-year activity cycle, the most powerful geomagnetic storm in twenty-one years hit the planet in May. With misty eyes, I scrolled through my phone’s notifications from any one of six aurora apps: “They’re HERE!!!” The lights, seen as far south as the Florida Keys, were no doubt dancing above those Churchillgray clouds that enveloped the east coast that night. I just shut off the phone and went to bed.

Five months later the sun sneezed out another huge coronal mass ejection of plasma in our direction, sending a severe G4 geomagnetic storm hurtling toward earth. While it wasn’t equal to May’s G5 storm, my heart leapt at the possibility, for in addition to bringing you those notifications, your iPhone can “see” the aurora that you can’t. Something about computational photography and artificial intelligence left me stand-

ing in the yard and hanging out windows taking photos of “nothing” and marveling at even the faintest hint of color on the horizon. In Pennsylvania. It was magical.

Little did I know.

The next two nights the show intensified, and word dribbled out to even those who don’t endlessly scroll through space weather sites that by October 10 the peak, “they” said, would arrive.

Less than a mile from my house on a (temporarily) quiet gravel road, a cloudless northern sky spread out before me. I leaned against the hood of the car. The temperature was hovering on either side of fifty. I was all alone as that gray flannel of May gave way to millions of stars. I felt like I was cheating. The first hint came at nautical twilight, just as the stars were coming out. By 9 p.m., if you knew what to look for, you could see a faint glow, and auroral pillars appeared on photos. By 9:30, those Google Map pins

See Awe on page 38

Paula Piatt

had been placed on the hills surrounding The Valley, and the curious had started to arrive.

“I don’t see anything,” the woman said, the disappointment of living a latitudinally challenged life never more evident.

“Do you have a smartphone?” I asked, knowing the answer.

“I do,” piped up her daughter, the device already in her hand.

“Point it at the sky, hold it still, and take a picture,” I suggested.

The aurora’s magic then took hold.

“Ooohhh…I never thought I would see this,” Mom said, her wonder turning into true excitement tinged with a little emotion as her own phone came out of her pocket. She took picture after picture—each bringing more marvel and awe. I stopped watching the sky and delighted in seeing her face in the glow of her phone. I took the opportunity to explain a bit about the aurora—the solar cycle and substorms, the charged particles hitting our atmosphere, why the colors were different. None of it, none of the science with its “whys” and “hows,” could explain the sheer enchantment of the moment.

Others came and went for the next hour or so, the tour guide in me sharing photo tricks and science tips and just delighting in the discoveries the visitors made. Most—if not all—of them would never get this opportunity again; people say “once-in-a-lifetime,” a lot, but this was its definition.

After about a half hour, the woman reluctantly put her camera away and she and her daughter got into the car. “This was amazing. I never thought I would ever see this,” she said again, her voice still filled with the spectacle. “If I didn’t have to get up for work tomorrow, I’d stay till dawn.” Her “thank you,” was returned in earnest; sometimes the greatest joy is bringing joy to others. They drove away in a cloud of dust and even as the lights danced in front of me, her smile, her excitement, her exhilaration outshone the sky for that moment.

I didn’t have to get up for work the next day, so I leaned on the car for another hour or so, taking a picture occasionally, to make sure my friend was still there. Notifications turned off on my phone, I didn’t know what was coming until the sky suddenly exploded. The logical left side of my brain knew it was a new solar substorm arriving; the holistic right side screamed at me to just enjoy.

For the next twenty minutes, the dance was not only to the north in front of me, but overhead and even behind. The colors fighting for attention with, and winning over, a first-quarter moon in the cloudless sky were everywhere. I didn’t know where to look next, but it really didn’t matter. My peripheral vision was also filled with color and light.

“Wow,” I said to no one.

More than once.

It was, indeed, the place for the lights.

Paula Piatt lives in the Northern Tier of Pennsylvania with her husband and two Labrador retrievers, where they hunt and enjoy the outdoors. An award-winning writer and member of the Dog Writers Association of America, she is an active member of the Pennsylvania Outdoor Writers Association.

continued from page 13

tional Grape and Wine Initiative, and serve on the boards of numerous other trade associations. It’s a testimony to his efforts and influence that in August, 1984, Governor Mario Cuomo signed legislation at Anthony Road legalizing the sale of wine coolers in food stores, and in 2013, Governor Anthony Cuomo came to sign legislation easing regulations for the state’s farm wineries. In 2022 the New York Wine and Grape Foundation honored John with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

In 1999 their son Peter, who’d been working in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, as an auto technician, returned to take over as head of Martini Vineyards, the family’s thirty-five acre grape-growing side of the business. One year later Derek decided to move on to Swedish Hill Winery on Cayuga Lake, so the Martinis had to find a new winemaker. But it wasn’t going to be John. “I’d made some good wines, but I just don’t have the attention to detail,” he admits. “My brain is always somewhere else.”

So they turned their attention to an accomplished young winemaker, Johannes Reinhardt, whose family had been making wines in Bavaria for six hundred years. He’d worked in the Finger Lakes for several years but was back in Germany when John called to see if he might consider joining Anthony Road.

“We never talked about how he made wine, just our philosophies of life,” John recalls, “and he said ‘I’ll do it.’...By now Peter was learning to grow better, and we had cabernet franc and lemberger and pinot gris, and Johannes was blending this with that, trying to produce the best.”

Johannes and other winemakers would meet periodically to sample one another’s work, asking “Why did you go with this? What if you did that?’” John remembers. “It was a rising tide thing: Anything you could do to improve the region’s reputation was a plus for everybody… Johannes changed us and helped change the Finger Lakes.”

After training his apprentice, Peter Becraft, to take over—Johannes had put him in charge of chardonnay one year, three wines the next, and six the year after—Johannes left Anthony Road to start his own winery, Kemmeter Wines in 2013, on a property adjacent to theirs. “The respect, trust and love the Martinis showed me was simply remarkable,” he says on his website.

The covid pandemic forced, or mercifully allowed, wineries to restrict crowd sizes at their tasting rooms, and that’s when the Martinis replaced the bars and barstools with tables and chairs. “We still get a lot of boomers, but they’re passing,” says Sarah. “And while we see a lot of women in their forties, we’re not seeing so many of the twentysomethings.”

And those they do see are “not so loyal to one brand. They want to experiment. They want things a little quirky or different, like a skinfermented pinot gris. So we try to meet those tastes.”

But Anthony Road’s future might well depend on John and Ann’s twelve grandchildren, for whom the vineyards and tasting room and cellars are a second home. “Our hope is the next generation, because I do want to retire some day,” says Sarah, sixty-five. “We all do, and we’ve earned it. We value what Mom and Dad did, but we don’t want to work that hard for our entire lives.”

Award-winning journalist David O’Reilly was a writer and editor for thirty-five years at The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he covered religion for two decades. Contact him at davidcoreilly@gmail.com.

Wade Spencer

Martinis

Susan Shadle Erb

Mountain Home SERVICE DIRECTORY

East tradE Co.

BACK OF THE MOUNTAIN

Harvesting Moons

By Deb Young

On the evening of the full harvest moon last October, I went out to find a good spot to capture the moon as it rose for the evening. Although I did take some pictures, none really seemed to do the moon justice. When I woke up early the following morning and went out on my front porch, there it was in all its splendor. I snapped this photo of the harvest moon with the fog in the valley, so typical of an October morning in the hills of Mansfield, Pennsylvania.