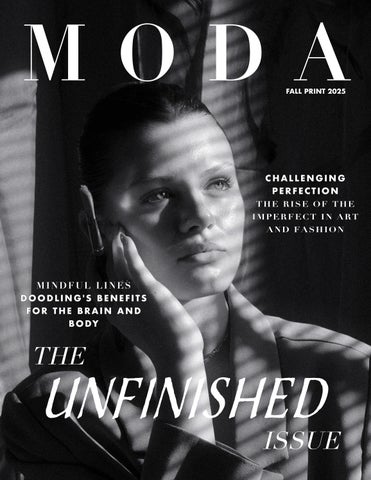

MODA

CHALLENGING PERFECTION

THE RISE OF THE IMPERFECT IN ART AND FASHION

MINDFUL LINES DOODLING'S BENEFITS FOR THE BRAIN AND BODY

CHALLENGING PERFECTION

THE RISE OF THE IMPERFECT IN ART AND FASHION

MINDFUL LINES DOODLING'S BENEFITS FOR THE BRAIN AND BODY

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Maddy Scharrer

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Rayyan Bhatti

PHOTOGRAPHY LEADS

Molly Claus

Indu Lekha Konduru

GRAPHIC AND ILLUSTRATION LEADS

OPERATIONS DIRECTOR

Adina Kurzban

INTERNAL RELATIONS

DIRECTOR

Makaylah Maxwell

PUBLIC RELATIONS

DIRECTOR

Kaitlyn Dietz

EVENTS DIRECTOR

Kasia Kirmser

CULTURE EDITOR

Kate Reuscher

ARTS EDITOR

Talia Horn

LIFESTYLE EDITOR

Tessa Almond

FASHION EDITOR

Marceya Polinger-Hyman

ONLINE EDITOR

Vanessa Snyder

WRITERS

Tessa Almond • Sarah Berendes • Francesa Blue • Leah Bulson • Hannah

Byma • Elise Daczko • Alyna

Hildenbrand • Talia Horn • Lily Kocourek • Liana Lima • Makaylah Maxwell • Marceya • Polinger-Hyman • Josie Purisch • Maddy Scharrer

Breanna Dunworth

Amelia Tingley

STYLING LEADS

Shira Malitz

Jessie Wang

SHOOT PRODUCTION LEADS

Sydney Alston

Heidi Falk

MODEL MANAGEMENT LEAD

Kaleyah Rivera

ART

Vinisha Agnihotri • Molly

Anders • Zoee Boog •

Breanna Dunworth • Natalie Khmelevsky • Devon

Moriarty • Kate Pennoyer

PHOTOGRAPHY

Hannah Byma • Molly

Claus • Elise Daczko • Kylie

Kieffer • Indu Konduru • Liana Lima • Melissa Liu • Maya Stegner

SHOOT DIRECTION AND STYLING

Kayleigh Carlos • Kelly Chi • Heidi Falk • Shira Malitz • Paige Valley • Jessie Wang

MODELS

Ela Altay • Ruby Gallin • Lily

Meinertzhagen • Devon

Moriarty • Delaney Pfieffer • Aviya Ramji • Kaleyah Rivera • Khinny Shin • Harper Sollish • Maya Stegner • Mirabella Villanueva

Process of Becoming

Avoiding Feeling Unfinished An unofficial guide to dodging existential

The Messy Girl's Manifesto: In defense of disorganization 35 Unfinished Business Closure Comes From Within

The Heart of an Unfinished Home

life-long process of decorating

The Art of the DNF To read or not to read

Black, White and Redacted Censorship in style

Well-Fed Minds, Starved Souls A lament for the conformist age

10 Mindful Lines Doodling’s benefits for the brain and body

20 435/435

The last page of Fredrik Backman’s “My Friends,” but does that make it the end?

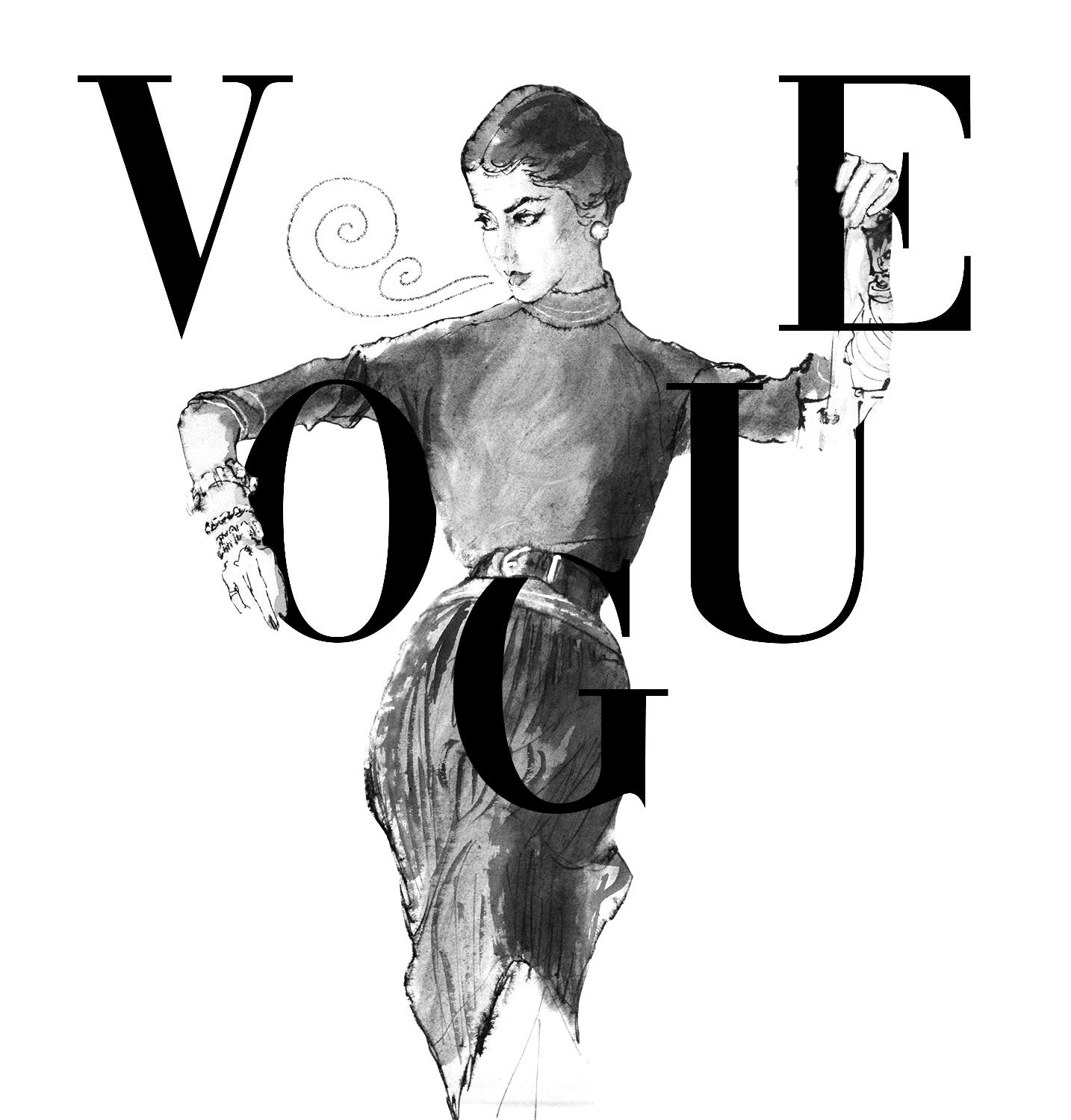

26 The Vogue Visionary You've Never Heard Of

How French illustrator René Bouché turned messiness into the language of high fashion

28 Surviving the 27 Club

How graffiti artist John Kiss painted his own obituary, and then outlived it

38 When the Spotlight Dims

But your Heart is Still Lit

15 The Unfinished Legacy of the Little Black Dress

The little black dress is more than just a garment; it is a revolution stitched in quiet defiance

32 Challenging Perfection

The rise of the imperfect in art and fashion

Dear readers,

I’ve never been a fan of endings.

And yet, I am constantly racing to complete things. Whether it’s finishing my current read, yearning for the weekend to wrap up a long week or hoping for summer days to fade so the fall breeze can swoop in, I’m always thinking of the next stop. But whenever I arrive at my romanticized destination, I’m always deflated when a chapter, big or small, comes to an end.

We spend so much time looking forward to endings because we assume tying up all loose ends creates a neat, comfortable existence. As a college senior on the brink of the next seismic shift in life, I often fantasize about a future where everything I hope and dream for has worked out. But spending so much time wishing for the future diminishes the joy abundant in the process of getting there. You can’t savor the fulfillment of an accomplishment without experiencing the hard work it took to get there, or smile through a series finale without being invested in the characters and plotlines.

Unfinished is all about the in-between — the messy, enigmatic and directionless times that might challenge us but, in tandem, force us to grow and become versions of ourselves that comfort cannot elicit. As we come to the culmination of another semester, Moda reframes our focus to the beauty in this unknown, grateful for the chance to view our story as a draft still being written.

This issue celebrates the opportunity embedded in all things unfinished. It is not about worrying too much about where we are heading; it is about the exciting array of possibilities at our feet. How lucky are we to be works in progress, undetermined in a world full of so many rich experiences to shape us along the way?

In her article “Unfolding Futures,” Liana Lima examines this beauty of becoming. She looks at the lives of people who famously carved their unique paths, like Sylvia Plath and Julia Child, as an inspiration to embrace the pivots and unexpected changes of our lives.

Hannah Byma puts into words the uneasy feeling of incompleteness after closing an important chapter in your life. Her article “When the Spotlight Dims” dives into the complexities of identity after the final curtain, related to her experiences as a lifelong dancer.

Elise Daczko looks at the beauty of interior decoration in her article, “The Heart of an Unfinished Home.” Daczko uses the perspective of a fellow student to emphasize how cultivating your perfect living space is an ongoing process, especially in college, when home can change frequently.

In true Unfinished fashion, different versions of this letter existed on an open tab on my computer for weeks. Rather than wishing to fast-forward to its completion, I reveled in the process of putting this theme into words and the evolution of drafting it; the breakthroughs and the ideas that hatched from letting it remain a living document.

Life is not about where you stand at the end of the day; it’s about all the tiny decisions we make that slowly pile up to create who we are. While our semester comes to a close, our journey together is to be continued…

Until next time,

Maddy Scharrer Editorial Director

Written by Liana Lima | Photography by Indu Konduru,

Falk, Shoot

Humanity is naturally driven to completion, enhancing the world one invention at a time. If things remained unfinished, the world would never progress. The first one to reach the finish line is awarded a trophy; the end-all be-all. Throughout early adulthood, many young people crave a finish line, a finished life, finished processes and careers before they have even begun. With the constant grasping for an ending, many unknowingly rid themselves of the opportunity to become. In a culture so rooted in finishes and efficiency, it can be easy to forget about figures who found success in living their lives “unfinished” and by exploring their passions.

American poet Sylvia Plath highlights how creating an unjust “finish line” can rob people of life. From Plath’s most famous work, “The Bell Jar,” the metaphor of the fig tree represents the terrifying prospect of choice. In Plath’s perspective, choosing a single fig or path effectively meant killing the rest.1 While many interpret the metaphor as a fear of choice, it is really the fear of a fixed life. Robert Ebert, American film critic, journalist, screenwriter and author, refutes this fixed way of life as he wrote, “We are put on this planet only once, and to limit ourselves to the familiar is a crime against our minds.”2 Rather than being caught in a cycle of despair, Ebert challenges audiences to use the freedom of choice to explore and develop their futures.

Steve Jobs is a prime example of success within the realm of “unfinished” lives. Jobs dropped out of college before creating one of the world’s most impactful technology companies. Instead of charting out a strict plan for the future, Jobs pursued his interests by impulsively taking a calligraphy class. This course ended up inspiring the future design for Apple’s iconic typography.3 Job’s story beautifully depicts how exploring self-interests, in addition to hard work, can lead to extraordinary outcomes.

1 Sylvia Plath, “The Bell Jar,” Robin Books, 1963.

2 Robert Ebert, “My Dinner with André” [Film review], Chicago Sun-Times, Oct. 11, 1981.

3 Matt Head, “Wonderful Lessons From Steve Jobs On The Creator Journey,” Matt K. Head, May 19, 2023.

Similarly, American chef, author and television host Julia Child revolutionized food in America through her passion for cooking, a passion that she didn’t discover until she was nearly forty years old. In her youth, Child worked as a secretary but was fired for insubordination over a mix-up with a document. Rather than letting the incident hold her back, Child pivoted and decided to volunteer her services to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), out of the mere desire to serve her country during World War II.4 During her time with the OSS, Child met her husband, Paul Child. While Paul was stationed in Paris, Child discovered her love for cooking and French cuisine. Rather than being confined by her past as a secretary, Child decided to pursue her passion for cooking by enrolling in the famous Le Cordon Bleu cooking school, which provided the foundations for her later success.5 Child’s life was entirely uncharted, yet by being open to new experiences, Child found her niche and inspires people around the globe with it.

As Child highlights, it’s always possible to pivot your path in life, and as Job exemplifies, some of the best creations come from passionate explorations rather than the strict quest for efficiency. While we have to make choices in life, it’s important to remember that choices provide fertile ground for growth. Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist Victor Frankl stated, “Most people want to live lives of meaning and purpose, but they don’t know where to begin.” It’s easy to think that meaning comes from an ending, when really it comes from the journey. Rather than trying to find your end, it might be more worthwhile to find your beginning. The act of becoming is never done, unless you think it is. A finite life would be boring; it is a gift to wake up each day, unfinished.

4 Central Intelligence Agency, “Julia Child: Cooking up Spy Ops for OSSCIA,” Intelligence and Operations, CIA, March 30, 2020.

5 Kelly Spring, “Julia Child,” National Women’s History Museum, 2017.

Written by Alyna Hildenbrand | Graphic by Natalie Khmelevsky

Many believe that art should be reserved for those who are extraordinary at it. They never bother creating anything after their elementary art classes, and never experience the tangible benefits art can provide in life. Not every piece has to be masterful, and anyone has the ability. For instance, it doesn’t take much time, effort or unique talent to doodle, but the seemingly simple action can have a positive effect on one’s mental health, learning and focus.

Art often provides stress relief, even from the smallest sketch. The repetitive and rhythmic process of doodling can decrease levels of the stress hormone cortisol, creating an immediate positive feeling for the body and mind.1 Doodling functions similarly to meditation in this way, slowing down the body’s movement and making people feel more present and in control.2

This sense of presence can also be attributed to doodling’s effects on memory. Doodling can help the brain discover lost parts of memories. These recovered puzzle pieces come together to form whole pictures, breathing more meaning into our lives. The brain feels more present and relaxed, no longer unconsciously searching for these missing pieces.3

Any student understands how easy it is to get lost in an academic setting. After sitting in a lecture listening to the same

1 Spowell, “The brain benefits of doodling,” Life Enrichment Center, Sept. 15, 2022.

2 Ibid.

3 Srini Pillay, “The ‘thinking’ benefits of doodling,” Harvard Health Publishing, Dec. 15, 2016.

professor talk about the same topics for over an hour, your mind begins to wander as the professor clicks over to the next slide. This is another area where doodling can improve our lives. Despite the wide discouragement of doodling in grade school, drawing in class allows deeper concentration for longer periods of time.4 Who knew the small penciled flower on the top of my notes probably helped me answer an extra question right?

Drawing concepts on paper also helps the brain understand them better. Combining the actions of writing and drawing activates both sides of the brain, boosting memory and recall.5 Sketchnoting is a great way to implement these actions. Something as simple as adding sketches or visuals to your notes can make comprehension of concepts easier through this creativity, enhancing your problem-solving skills.6

Though doodling is a powerful and easy tool, most miss out on its multitude of benefits. However, it can be easily slipped into almost any aspect of life. Academically, sketchnoting in class or work is an easy way to start. It can be as intricate or simple as you want, taking up as much or as little time as you need. If drawing while taking notes seems unbearable, try adding a quick sketch of a concept you learned at the end. Taking short breaks during study sessions to draw can help keep you focused and on track in the

4 Ibid.

5 Tanmay Vora, “Benefits of sketchnotes and visual thinking for business leaders and teams,” TanmayVora, Aug. 29, 2025.

6 Ibid.

long run. During your next studying marathon, try setting a timer for five minutes at the end of every hour you study to doodle and give your mind the creative time it needs.

Doodling doesn’t have to be saved for the classroom; it can be a social activity, too. Take a walk to a park, busy street or other random location with a friend and notebook in hand to draw what you see around you. A parked car, ducks on a pond or maybe a kid running around the playground. There is inspiration everywhere. You can even try to draw each other!

It is also important to give yourself personal doodling time. Saving a few minutes at the end of each day before bed to work through your thoughts and just draw will help your brain and body relax. Sit at your desk for a moment and doodle something you remember; it will likely help you feel fulfilled and grounded going into the next day.

Even with all of the joy and positive effects art can have, it is often an overlooked form of self-care. Adding the occasional doodle to your life can provide many benefits. In providing your creativity a space to breathe, you give yourself the space to take a step back and a deep breath as well. So the next time you’re feeling burnt out during a long study session or stressed about the week ahead, sit down, look out your window and grab a pencil.

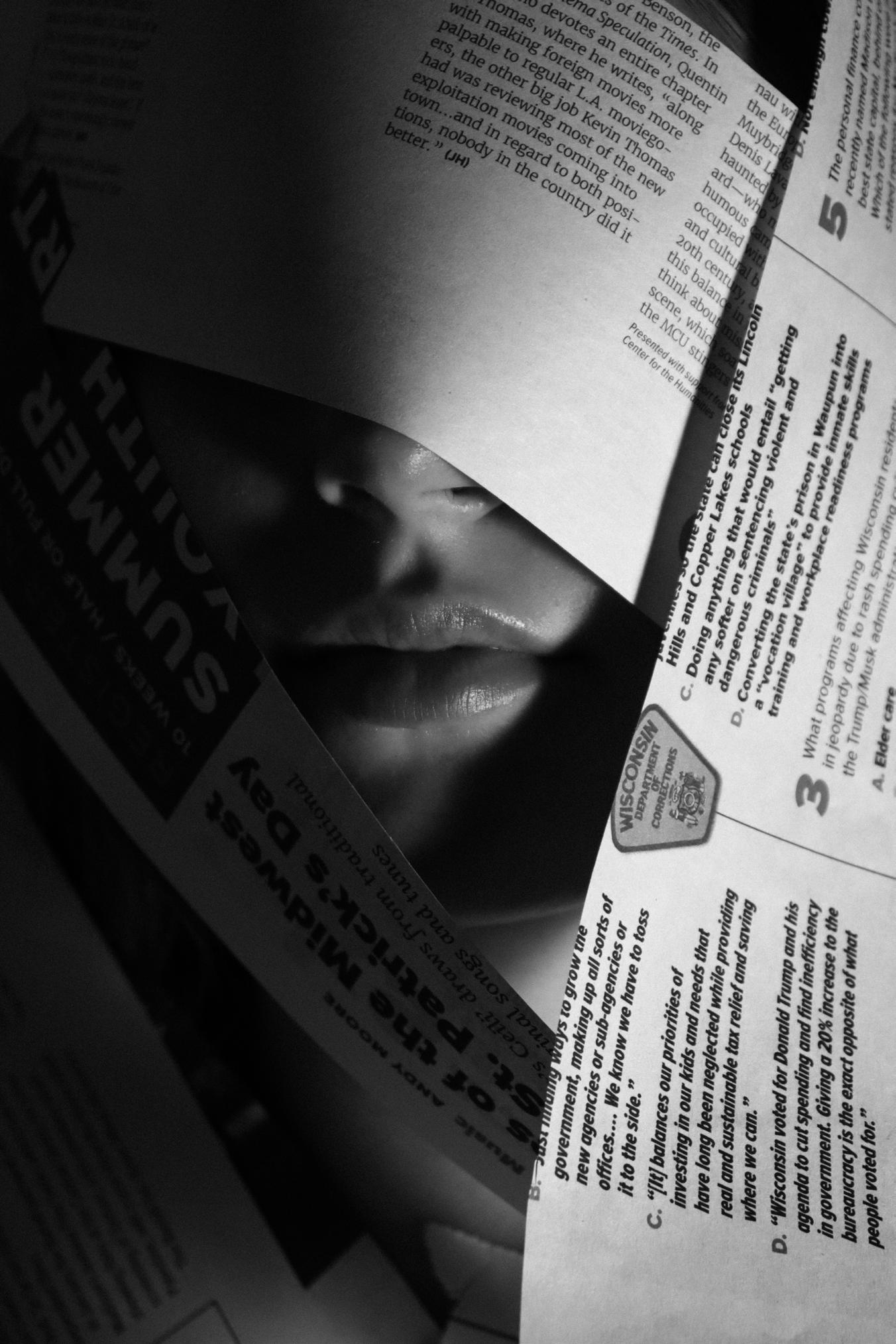

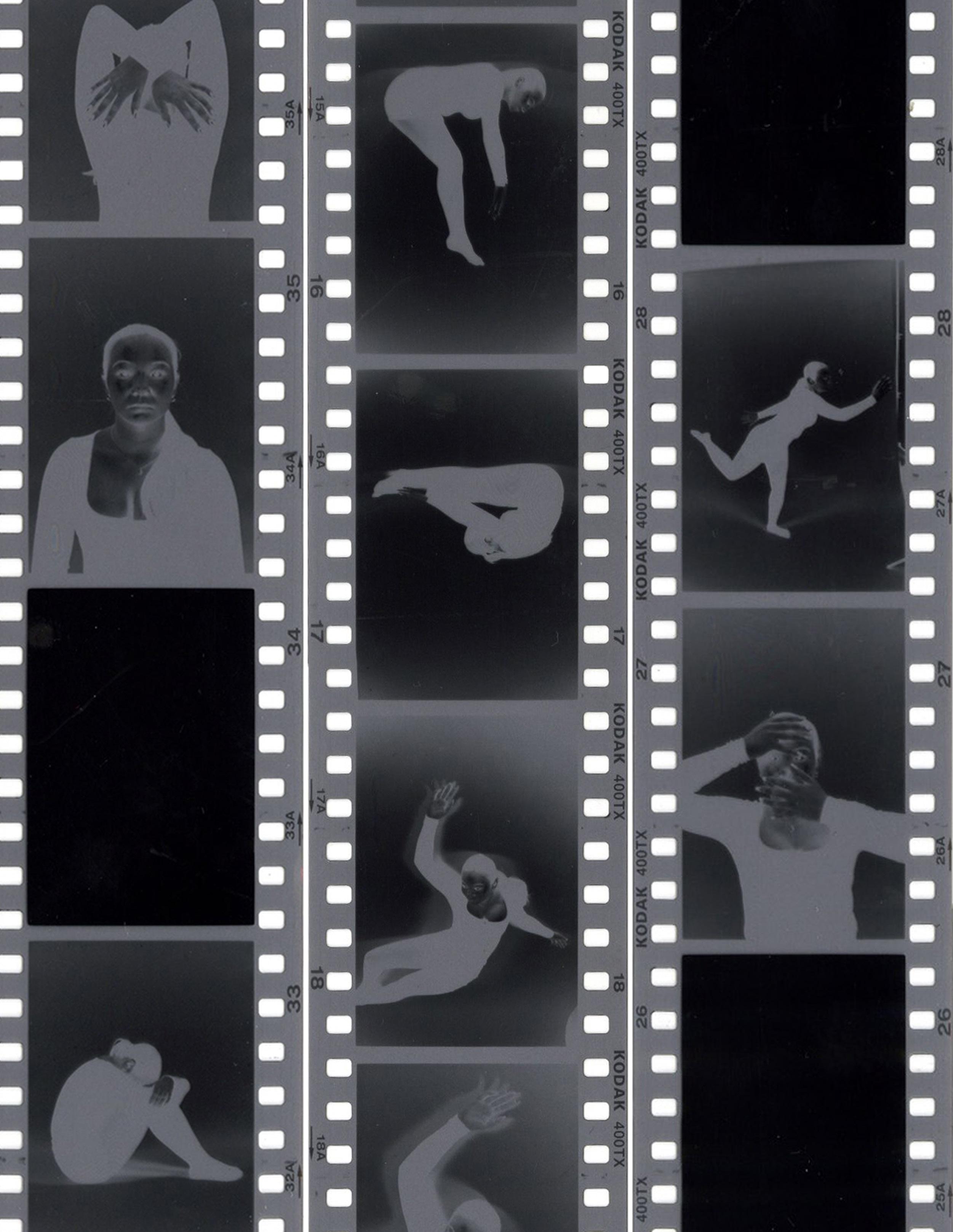

Written

by

Makaylah Maxwell, Internal Relations Director

| Photography by Molly Claus, Photography Lead | Shoot Direction by Heidi Falk, Shoot Direction Lead | Styling by Jessie Wang, Styling Lead | Modeled by Ruby Gallin

In a world curated by control, sometimes what is missing says more than what remains. Redactions don’t confront, they subtract. The black lines don’t just hide content; they leave behind a shape of something that was once whole. It’s the art of erasing dissent, identity and memory; leaving behind a version of reality that feels polished but incomplete.

We often think of censorship as being loud and unmistakable: banned books, blocked websites and the shutdown of protests. But censorship is also missing footage, the redacted document and the stories that never made it into the textbook in the first place. It’s the illusion of completeness, curated by institutions that decide what’s worth remembering and what’s deemed safer to be forgotten.

Governments and institutions use censorship to curate ideal versions of society that omit the reality of situations. Whether it be secret missions from the Cold War or investigative documents requested from local police departments, the black lines on redacted documents have been deployed to withhold details otherwise vital for the democracy of our nation. Institutions have the power to shape perceptions and suppress dissent with censorship at the helm.

The Espionage Act, hailing from World War I, criminalized anti-war speech and enabled postmasters to deny sending mail that could indicate treason or forcible resistance to the United States’ involvement in the war.1 GermanAmerican newspapers were effectively suppressed due to a strong anti-German sentiment that forced English language translations and encouraged overall distrust in immigrants.2 During World War II, the U.S. censored any wartime photographs until 1943, when the U.S. feared complacency back home and strategically published a sliver of photos to remind citizens of the wartime effort and the sacrifices made.3 Black press was systemically suppressed by white authorities seeking to silence their calls for justice.4 These historical examples act as reminders that censorship is about controlling visibility and tailoring public opinion to fit a precise agenda.

Censorship doesn’t just apply to literature and the press; it’s also embedded in our daily fashion choices. In fashion, resistance is wearable. Our everyday clothing is curated by both the manufacturer and the individual to represent what’s allowed to be expressed. In regimes where identity is policed, clothing becomes a battleground. Fashion and people’s choices become a language of resistance, a way to speak when words have been stripped away.

Designers and artists have long responded to these suppressions, whether by mimicking the aesthetics of censorship or by sparking protests against the discrimination. France has repeatedly banned garments such as the hijab and niqab, framing them as threats to French secularism.5 This ban on hijabs and niqabs for women under 18 years old was met with sentiments where women maintain that the veil is a symbol of identity and resistance. Advocates declare this is Frances’ attempt to control their citizens and further perpetrate discrimination that Muslim women face in France; they’ve combatted these bans with social media campaigns such as #HandsOffMyHijab.6 Protest garments carry the weight of what’s been erased and covered up; they stick resistance into every seam.

1 Geoffrey Stone, “The Origins of the Espionge Act of 1917: Was Judge Learned Hand’s Understanding of the Act Defensible?” Chicago Unbound, 2018

2 Elisabeth Fondren, “America First and America Only: German-American Newspapers, Selfcensorship, and Press Freedom in World War I,” Journalism History, March 2019.

3 Carol Schultz Vento, “Censorship and World War II,” Defense Media Nework, July 2014.

4 Fred Gillum, “Censorship during World War II,” EBSCOin, 2022.

5 Raphael Cohen-Almagor, “Indivisibilité, Sécurité, Laïcité: the French ban on the burqa and the niqab”. National Library of Medicine, October 2021.

6 Cady Lang, “Who Gets to Wear a Headscarf? The Complicated History Behind France’s Latest Hijab Controversy,” TIME, May 2021.

Censorship scars cultures. It fractures memories and interrupts lineages. Archives missing key documents and the exclusion of marginalized designers and headpieces all contribute to the sense of incompleteness the modern viewer feels. The ache of missing context is real. And even when we read between the lines, we can’t be certain what the original draft or narrative was. There are gaps everywhere in our history that often only become unearthed years later. Through oral histories, underground publications, coded fashion and digital archiving, communities have preserved what institutions have fought to erase. The unfinished becomes a site of resistance. A redacted line invites speculation. A banned book becomes a necessary read. A censored outfit becomes a symbol for inclusion and advocacy.

Censorship is not just a political tool but a cultural force. It leaves us with fragments and outlines. But in those outlines we’ve found power. We’ve found a possibility of reconstruction. We’ve found the courage to ask: What’s missing? Who’s missing? How do we make space for what was never brought to the surface? The redacted speaks the truth, and it’s the audience who must learn to hear everything. We must challenge false narratives and insist on the right to create our own, because to resist censorship is to restore the truth.

Direction

The little black dress is more than just a garment; it is a revolution stitched in quiet defiance

Written by Tessa Almond, Lifestyle Editor

We all know the iconic little black dress. Immortalized by icons Audrey Hepburn, Princess Diana and countless others, the little black dress remains an uncontested staple. Though it appears simple, the little black dress carries a long and meaningful history beyond its place in our closets.

After women earned the right to vote in 1920, they began to change their style to reflect their feminist beliefs. For the first time, hemlines rose above the knee, and fashion became the new language of women’s liberation.1 Though plain in color, design and structure, the little black dress became a universal symbol of versatility, confidence and timelessness.

The little black dress was first popularized by French designer Coco Chanel in the 1920s. Until this point, black dresses symbolized mourning and grief, and were therefore only worn as funeralwear.2 Chanel aimed to break this convention and took advantage of the color’s simplicity. Her vision was to design a dress that was both affordable for women and suitable for all occasions, from work to partying.3 One of American Vogue’s 1926 issues featured a sheath black dress designed by Chanel, representing a turning point in the fashion world for its chic simplicity and versatility.4 The little black dress was worn ubiquitously until the end of the 1920s. A combination of wartime, nationwide financial crisis and decreased freedoms for women

1 Lydia Rosenstock, “A History of Hemlines

- How the Political Climate Affected Skirt Lengths of the Past,” Political Fashion, Sept. 8, 2023.

2 “Little Black Dress: The Evolution of a Timeless Fashion Staple,” Vogue College of Fashion.

3 Nesterenko, “The Little Black Dress: A Timeless Classic by Chanel,” Fashion Illiteracy, Jan. 2, 2024.

4 “Little Black Dress: The Evolution of a Timeless Fashion Staple,” Vogue College of Fashion.

all resulted in the depopularization of the little black dress style.5

The little black dress returned and rose to iconic status through the Hollywood movie screen. Audrey Hepburn’s black dress look in “Sabrina” (1954) and the Givenchy look from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1961) solidified the little black dress as a worldwide symbol of quiet glamour. Other Hollywood stars like Marilyn Monroe took inspiration from Hepburn by wearing iterations of the little black dress to movie premieres, dinners and other public-facing events.6 Designers began to experiment with silhouettes, waist cuts and necklines of black dresses during runway seasons.7 Princess Diana also wore a version of the little black dress, famously known as “The Revenge Dress,” after her very public divorce from Prince Charles. Her iconography as a humanitarian and public rejection of monarchical norms associated the little black dress with qualities like perseverance, kindness, confidence and humility.

The little black dress has been a staple since the 50s, with designers of all kinds experimenting with it as a foundation. The 90s in particular saw an uprising in black dress styles, with runway shows by Chanel, Armani and Versace adding their personal flair to the iconic style.8 Today, designers continue to debut runway looks featuring short black dresses. Celebrities like Zendaya, Lily Rose Depp, Kylie Jenner and Hailey Bieber swear by the little black dress both on and off the red carpet.

5 Lydia Rosenstock, “A History of Hemlines - How the Political Climate Affected Skirt Lengths of the Past,” Political Fashion, Sept. 8, 2023.

6 “Little Black Dress: The Evolution of a Timeless Fashion Staple,” Vogue College of Fashion.

7 Ibid.

8 Nesterenko, “The Little Black Dress: A Timeless Classic by Chanel,” Fashion Illiteracy, Jan. 2, 2024.

Whether you are rushing to class, strolling to a coffee shop, Ubering to a fancy dinner with friends or stressing before a first date, a little black dress can help solve any fashion crisis. Its versatility is its strength; with the help of some accessories and the right shoes, you can dress it up or down, wear it minimally or maximally, and you can even wear it to bed. If you have errands to run, style the dress with some ballet flats of any color, gold earrings and sunglasses. For a chic going-out look, throw on a blazer or fur coat over the dress with some heeled black boots. If you are a college girl headed to the bars, pair with your favorite jacket, gold hoops, and casual sneakers for a look that’s comfortable, cute and effortless.

The little black dress will likely evolve with the times, adapting to new trends while maintaining its timelessness. Future styling could involve more eco-friendly approaches, creative layering, high-tech materials and other personalized touches. Its form is ever-changing, with a long history of powerful women behind it.

Ultimately, the little black dress is iconic precisely because it refuses to demand attention; its power lies in the quiet confidence of simplicity. Beyond its seams and exterior, the little black dress represents a timeless, unfinished legacy of women. By wearing the little black dress, you embody the same confidence as those who made it a cultural staple. It is not a trend, but rather an ongoing expression of elegance, effortlessness and resilience.

The last page of Fredrik Backman’s “My Friends,” but does that make it the end?

Written by Leah Bulson | Graphic by Vinisha Agnihotri

a heart can beat at, which no one who’s stopped being young can remember. She talks on and on, and Ted listens, and Heaven leans closer to the roof of the house to hear. Louisa tells him about art so beautiful that just seeing it makes you too big your body, a sort of happiness so overwhelming that it’s almost unbearable.

“When I was standing in front of that painting, I forgot to be alone, I forgot to be afraid, do you understand?” she says.

Of course Ted understands. If you’ve experienced it once, you never forget it. If not, there probably isn’t any way to explain.

“If that artist is one of us, really one of us, you have to do whatever you can to help,” he says.

“I know,” she says proudly.

And so the next adventure begins.

“You sound happy,” he smiles.

“I am. You sound happy too.”

“Maybe I’m on my way.”

“That’s all anyone can be, Ted. On your way!”

“You sound grown-up.”

“You sound old.”

“I’ve always been old.”

More rattling on the line. Then she asks:

“Can I ask something?”

“Preferably not,” he yawns.

“Well, it isn’t really a question, it’s more of a suggestion.”

He replies with a sigh, and she of course interprets that as enthusiasm, so she goes on:

“I know what you ought to do, Ted, with the rest of your life! You ought to write a book!”

“Ted is sitting on the edge of his bed. The sun is on its way up outside the window. He presses his feet gently against the floor, making one of the floorboards creak. Then he laughs quietly.

“What would someone like me write a book about?”1

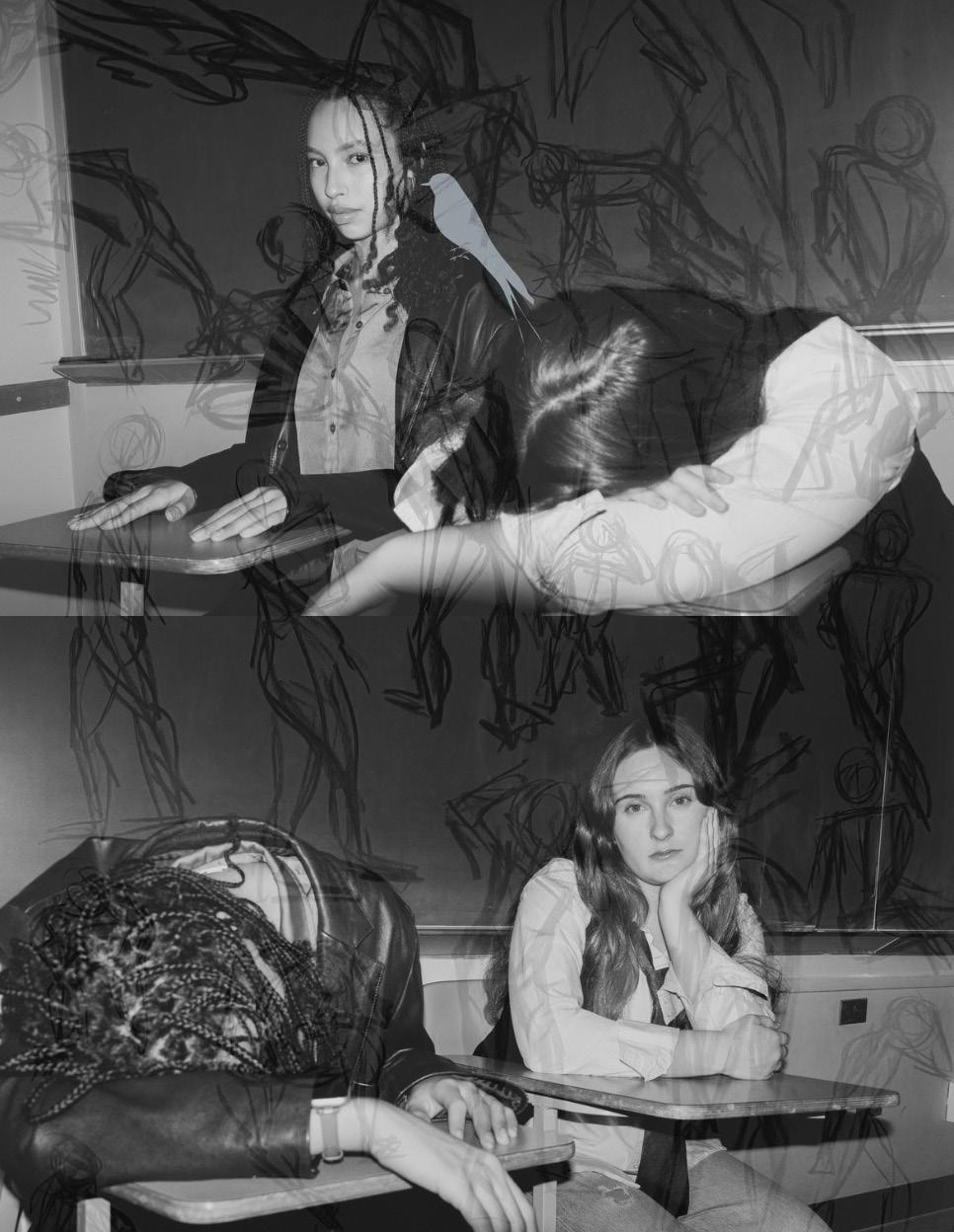

By Marceya Polinger-Hyman, Fashion Editor | Photography by Kylie Kieffer | Graphics

by Kate Pennoyer & Devon Moriarty | Modeled by Kaleyah Rivera & Devon Moriarty

Iweep for all the writers’ words we will never read and all the artists’ pieces we will never consume because someone’s father was a great athlete and his father’s father was a successful businessman. As a society, we lose so much through the fear of being talented at the abnormal, and we sacrifice so much of these seemingly deviant talents to feel a legacy of love rooted in convention.

However, the real love we seek is often found in the violent scribbles in a sketchbook or the seemingly meaningless poems written in sloppy cursive on a random page in the back of your old science notebook. What we have been taught is a lie; the “starving artist” may not make an extreme amount of monetary wealth, but they are fed in a way that a businessman may never be able to afford: with passion and fervent dreams. Art does not rot like picked fruit, but the dream of pursuing art often does. However, the first time one creates art, a metaphoric seed is planted, and it will grow for a lifetime if watered properly.

Now, that is not to say the businessman can’t be an artist, a writer or an exceptionally prophetic poet. It is often his internalized shame of the atypical that prevents him from exploring other facets of his being. It is also not to say the artistic woman who has devoted her life to writing her novel doesn’t have the innate talent to become a CEO of a Fortune 500 company. The real issue boils down to society’s lack of openness and its immense infatuation with clear-cut boxes.

The current climate of our world is hyperfixated on a forced categorization of everything and everyone. Every dream, talent and ambition must fit neatly into a pre-labeled box aptly titled, “The 10-Year Plan.” We are asked from a very young age what we want to be when we grow up, and this question persists. Most children are told to pick a lane before they even know what roads exist, and the moment they step outside their assigned box, society rushes to correct them. A poet is told their words won’t pay the bills. A dancer

is told to find something “more practical.” A scientist who paints or a banker who writes quietly becomes a contradiction to be explained rather than a human being allowed to exist in fullness. These boxes, while designed to give order, often become cages that suffocate curiosity, risk and creativity before they ever have the chance to bloom.

To label, to box, to define; these are ways of controlling the uncertainty of being human. From an early age, we are told that order is synonymous with safety, and yet, all art — all creation — begins in disorder. Sir Ken Robinson, in his seminal TED Talk, “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” argues that education systems “stigmatize mistakes,” teaching children to fear failure and, by extension, to fear the unknown.1 But what is creativity if not the courage to wander into uncertainty and return with something meaningful?

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once warned that “the surest way to corrupt a youth is to instruct him to hold in higher esteem those who think alike than those who think differently.”2 Centuries later, his warning still echoes through the drab cookie-cutter boardrooms, classrooms and dinner tables.

1 Ken Robinson, “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” TED, Feb. 2006.

2 Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Dawn of Day,” trans. J. M. Kennedy, London: Macmillan, 1911.

Organizations consistently “undervalue creativity because its outcomes are uncertain,” preferring efficiency to originality, according to a 2019 Harvard Business Review study.3 In other words, even in adulthood, we are rewarded for coloring inside the lines. Yet the human spirit was never designed to be efficient; it was designed to seek meaning.

The boxes we build — corporate, cultural or familial — are illusions of control: comforting but confining. True fulfillment lies not in perfect order, but in embracing the beautiful disorder of self-expression, where art and philosophy converge to remind us that to create is to exist fully.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy is not the art we never see, but the parts of ourselves we never allow to exist. We spend lifetimes chasing the validation of legacy from fathers or the security of systems, forgetting that our truest inheritance is our capability to create. The world does not need more replicas of success; it needs the raw, trembling honesty of people willing to be unboxed. Because when someone dares to choose art over approval and imagination over imitation, they do more than create — they free the rest of us from our hollow boxes.

3 Jennifer S. Mueller, Shimul Melwani and Jack A. Goncalo, “The Bias Against Creativity: Why People Desire but Reject Creative Ideas,” Psychological Science 23, no. 1 (2012): 13–17.

Written by Sarah Berendes

Iremember vividly the first real mental breakdown I ever had. I couldn’t have been older than 12 when I had learned that most Olympic athletes start training as soon as they can walk.1 At such a young age, I felt crushed under the weight of the world and debilitated by the potential I thought I had wasted. How could I ever be great or make an impact if I hadn’t been dedicated to anything, much less a sport, from that young an age? I felt like I had no chance of finding meaning in my life. In retrospect, that was an incredibly dramatic feeling for a 12-year-old to experience, but over the years it has been an uphill battle fighting it.

The truth is, I was not alone in feeling this way. Almost 3 in 5 adults ages 18-25 have reported feeling like they lack meaning or purpose.2 It isn’t uncommon to feel behind or unfinished. As job and housing markets become more and more exclusive, many young adults face roadblocks in finding meaning in life.3 This makes it difficult to progress in life at the same pace as our parents.

1 Sarah Fielding, “Here’s the Average Age Olympians Start Training For Their Sport,” Bustle, Feb. 15, 2018.

2 “Mental Health Challenges of Young Adults Illuminated in New Report,” Harvard Graduate School, Oct. 24, 2023.

3 Sharita Forrest, “Young adults juggle conflicting pressures to hurry up - and wait,” University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, April 15, 2025.

Mental health also exacerbates these problems, making it feel impossible to break out of the cycle. “Falling behind” your parents’ pace of life may make you feel depressed, which in turn may make you feel less motivated to go out and try to change these feelings. Even if you do feel motivated enough to try to break out of this, you may still feel that you lack purpose as you put all your energy into catching up with expectations that were only realistic in the past. The good news is that there are ways to alleviate these feelings.

The first thing that helped me was accepting that, though I may not have the most grandiose impact, it doesn’t mean that I don’t have the power to make a difference on a smaller scale. Finding little things in your day-to-day life that can make others’ days better is an extremely fulfilling practice. It can be as small as an extra compliment while passing someone on the street, or holding the door open for a stranger you see. My personal favorite is picking up pieces of litter as I come across them. It’s perfect for those of us who aren’t looking for too much social interaction.

Another act that can make an impact is volunteering, even if done on a small scale. And, it has been shown

to improve mental health and sense of purpose.4 There are a variety of organizations on campus that focus on philanthropic efforts, such as the Morgridge Center for Public Service, WUD Volunteer Action Committee and Golden Years Volunteers that are always looking for those ready to lend a helping hand.

But besides doing smaller altruistic tasks, how do you find true meaning? I believe if you dig deep enough, you can discover this for yourself. The answer likely lies in whatever you love to do most.5 What you do doesn’t have to profoundly change the world so long as it provides positivity to someone, including yourself. Whether you think so or not, your purpose in this world is out there, even if it may seem difficult to find. Feeling lost is just a sign to break out of your routine and dedicate yourself to something you’re passionate about.

4 Angela Thoreson, “Helping people, changing lives: 3 health benefits of volunteering,” Mayo Clinic Health System, Aug. 1, 2023.

5 Dr Esmarilda Dankaert, “A Psychologist’s Guide To Finding Meaning In Life,” Medium, March 18, 2025.

Written by Tessa Almond, Lifestyle Editor | Graphic by Breanna Dunworth, Illustration & Design Lead

Half-rendered figures in whites, blacks, beiges and blank spaces. These simple elements put René Bouché on the map as one of the most distinct yet overlooked fashion illustrators in history. Without any formal training, Bouché found himself working alongside Vogue, the largest fashion powerhouse in the world. With charm, attitude and unconventional imperfection, he was able to perfectly capture the effortless essence of high fashion.

Bouché was born in Prague in 1905 or 1906.1 He moved to Munich in his mid-teens to study art history at Munich University, and supported himself by illustrating children’s books.2 In 1927, he moved to Berlin with hopes to make a career out of his passion for illustration, but his pursuits were cut short.3 Fearing for his own safety as a Jew, Hitler’s rise to power forced Bouché to relocate to Paris in 1933.4

In Paris, Bouché did advertising for commercial clients like Nestlé, Ascott Shoes and Peugeot. A few of his experimental, sketchy fashion illustrations caught the attention of Plaisir de France, a famous magazine dedicated to fashion and architecture, and later, French Vogue, which he contributed to regularly.5 While still living in France, World War II broke out, and Bouché decided to join the army. He was captured and later escaped a detention camp.6

In an effort to escape the trauma of war, he left for New York in 1941 and presented himself at the Vogue offices there. After working on a new illustration portfolio for six weeks, Vogue hired him, and he worked for them until he died in 1963.7

1 “Collection: René Bouché Fashion Illustrations,” The New School Archives & Special Collections, n.d.

2 David Downton, “René Bouché,” Substack, Sept. 7, 2022.

3 Geo Neo, “Fashion Fridays - René Bouché (1905–1963),” Illustrators’ Lounge, Dec. 11, 2015.

4 David Downton, “René Bouché,” Substack, Sept. 7, 2022.

5 Ibid.

6 Geo Neo, “Fashion Fridays - René Bouché (1905–1963),”

Illustrators’ Lounge, Dec. 11, 2015.

7 David Downton, “René Bouché,” Substack, Sept. 7, 2022.

His time with Vogue in the 40s and 50s was one of transformation, experimentation and stardom. He represented Vogue on the Royal Mail Ship Queen Elizabeth, drew post-war cities seen during his travels and, of course, worked backstage for the Parisian couture scene, sketching the designs of Dior and Givenchy after runway shows.8 Vogue also commissioned him to do charcoal sketches for their issues, often combining fashion and landscape portraiture.9 Outside of Vogue, Bouché was commissioned to paint portraits of notable public figures, including Truman Capote, Sophia Loren, Igor Stravinsky, John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy, among others.10

Bouché’s legacy continues long after his death. He stood out to Vogue not because of realism, but because of the abstraction, messiness and blank spaces in his sketches. Instead of valuing picture-perfect detail, clean cuts and precision, he showed that unfinished messiness was the most effective way to represent the world’s most famous designers. You can even buy prints of his work at the famous booths along the Seine River in Paris. Designers today often embody this messiness in their sketches, representing the tedious and uncertain process of bringing a garment to life. In the fashion world, sketching has become synonymous with constant change, transformation and the use of rough lines to represent energy.

Bouché’s illustrations invite viewers to fill in the blanks, feel the movement and recognize the personality behind the lines. He was able to capture fleeting moments of beauty, the elegance of imperfection and the comfort of uncertainty. From Bouché, we can all learn to appreciate that the most enduring elements of art are the spaces left for us to fill.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

Written by Talia Horn, Arts Editor | Graphics by Zoee Boog

Content warning: This article discusses topics related to suicide and addiction. Read at your own discretion.

Maybe it’s the age where people tend to get reckless. Maybe it’s the age when people start to lose hope. Maybe it’s just the age when luck simply runs out. Regardless of why, there seems to be a supernatural element that emerges when you hit 27 years old, the age we lost many famous figures. Most of these iconic artists fell to drug and alcohol abuse at a young age, with the exception of Kurt Cobain, who committed suicide. These artists comprise the ominous 27 Club.

There has been an anomaly of many celebrities dying at age 27. Members of this notorious club include Jimi Hendrix, Amy Winehouse, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Jean Michel Basquiat, Kurt Cobain, Brian Jones and almost the artist who created The 27 Club mural, Jonathan Kislev, now referred to as John Kiss. The Israeli artist painted his famous 9.8 x 27-foot mural in 2014 on the streets of Florentin, Tel Aviv, depicting not only the lives of these seven tragically famous figures, but also himself.1

Tel Aviv has a unique respect for graffiti. The city is scattered with colorful, pretty, political and religious artworks across public walls, streets and train tracks.2 This iconic piece is beloved by locals and is often featured on graffiti

1 Israel Herzl, “Graffiti tour in the Florentine neighborhood,” April 22, 2021.

2 Ibid.

tours. The large work transformed a previously bland white wall into his own personal canvas. It depicts six portraits of those famous artists, who each died tragically at 27 years old, with the excess spray paint trickling down into the wall beneath them. Each artist is drawn and memorialized in their own color scheme, excluding the final figure, Kiss himself, whose faded figure in black and white is drawn to the right of Amy Winehouse. As much as the artwork touches viewers, its story of the artist remains the heart of the piece.

Kiss, who struggled intensely with addiction, believed he would soon make his debut as the newest member of the 27 Club. This was why he decided to insert himself as the last, but faded figure; a foretelling of his presumed fate.

However, Kiss, with a newfound drive, clawed his way from the hole of addiction to a healthy and sober life. In an Instagram post discussing the artwork, he defined it as a testament to the price of fame, analogizing it to a “candle burning all too quickly.”3

He signed off that same post by saying, “Glad I didn’t join the club!”4

Having outlived the future he once prophesied for himself on that Tel Aviv wall, it was time to rewrite the story. On top of Kiss’s self-portrait on the wall now lie splotches of white paint. Graffiti often portrays an informal and fluid style, but in The 27 Club artwork, the juxtaposition of the paint blotches with Kiss’ beautiful strokes adds an entirely new layer of meaning.

While some believe it could have been the work of other jealous artists, or even Kiss himself, the most commonly accepted legend is that the addition was the work of his sister. She is rumored to have thrown buckets of

3 Jonathan Kiss (@johnkissauthor), July 30, 2021.

4 Ibid.

paint on Kiss’ portrait, erasing him from the colorful obituary. Her actions were a statement that sometimes the eraser can be as loud as the lead tip. It would have been easy for Kiss, with the help of a very tall ladder or forklift, to return to the site and completely cover his faded portrait. Nice, neat and uniform with the visual identity he gave to the piece. But this would have hidden the powerful story behind it.

It is messy, raw and honest. Maybe Kiss wanted to show the world he refused to succumb to the 27-yearold curse. Maybe he thought his art could inspire the next person struggling who stumbles upon this wall in Tel Aviv. Regardless, Kiss understood that there are stories to be told in the strokes we do not paint and the words we leave unspoken.

His story is a reminder of the power of welcoming help from loved ones. Members of the 27 Club, like Amy Winehouse and Jimi Hendrix, were never able to share their final words the way they should have. Kiss lends a hand, reminiscent of that of his sister, to give them a platform to continue impacting people. The inspiration from their lives and stories can continue to bleed into ours as the spray paint bleeds into the white wall, honoring their memories.

Written

As trends eventually grew tired and embarrassed of the maximalism that ruled the late 2010s and early 2020s, minimalism found space in the fashion world through the clean-girl aesthetic.

The clean girl is minimal through and through — her hair in a perfectly slicked-back ponytail, her nails polished in an inoffensive color and her makeup crafted perfectly to create the illusion of a bare face. This unforgiving aesthetic refuses to accept room for any mess. If her hair is undone, nails chipped or makeup too heavy, the “clean girl” disappears, and she is relegated to the status of just a regular girl.

As my TikTok For You Page became overrun with the archetypes of the clean girl aesthetic, I had convinced myself that I was attracted to the look by nothing more than my own conviction. And just as I am tricked by every passing fad, I wanted to be a part of it. I craved their order and elegance, and I tried to mimic an aesthetic that, in reality, was more of a personality trait.

The clean girl aesthetic relies on effortless perfection. You can’t try to become the clean girl — you must be her already. So it shouldn’t have been a surprise for me — a girl who could never be bothered to take her makeup off at night and is currently decorating

her keyboard with the grease of her afternoon snack — when I couldn’t just embody this aesthetic.

No matter how hard I tried to maintain a flawless image, the mascara I put on in the morning always seemed to paint my undereyes by nightfall, and the curls that my slickback ponytail attempted to hide found sneaky ways to unearth themselves.

Once my own chaos exiled me from the clique of clean girls, I had to make a choice: either wallow in the jealousy of unattainable perfection, or find the romance in my own mess.

Choosing the latter, I turned back to the movies that raised me, and the characters that I worshiped before influencers ever had the chance to infect my interests.

My mind immediately wandered to the face of one of my favorite romantic comedies, with a protagonist who just happens to be the antithesis of the clean-girl aesthetic: Bridget Jones of “Bridget Jones’ Diary” (2001). With even Netflix describing her life as “a bit of a mess,” the eccentricities that fuel her disorganization are exactly what make her so lovable. Jones’ willingness to make a fool of herself — whether that be by going viral for failing on live news or running half-naked down the street

in the name of love — opens doors that perfection would keep politely closed. If Jones favored office-appropriate outfits and work party speeches that did not ramble on, she would unknowingly forfeit the love, success and selfhood that became her happy ending.

Discovering examples of unapologetic messiness in the media and those around me — from the teachers who never had lesson plans to the friends who could never pin down one aesthetic — I found myself drawn to those who embrace their clutter. Why did I ever covet an aesthetic that demanded invisibility?

The illusion of perfection makes you live in fear of losing it. When you rejoice in your own mess, you can accept the chaos and layers of your own person, using it as fuel to break the routines that flatten our lives. In the pursuit of perfection, we risk losing our personalities as collateral.

While some certainly hide it better than others, everyone is unfinished. Yet it is always those who treat their unfinishedness as strength, who do not shy away from unmade beds and mismatched outfits, who get to discover the beauty that exists in the untold stories.

The rise of the imperfect in art and fashion

Written

Direction by Kelly Chi | Styling by Jessie Wang, Styling Lead | Modeled by Aviya Ramji

Imperfection has existed in creativity since the beginning of time, and it often weaves the stories that perfection leaves untold. When looking at fashion, there is a great power in leaving something unfinished, something imperfect.

Artists strive for perfection, but it is close to impossible to achieve. Some of the most beautiful, important pieces of art in history are anything but perfect. Quite frankly, the imperfections are what make them so captivating. The Entombment by Michelangelo was left unfinished, without much talk about why or how it was abandoned.1 Yet, it is described as a beautiful and celebrated Renaissance piece nonetheless. The Entombment demonstrated that finished does not equal perfection, and perfection is in the eye of the beholder.

Imperfection doesn’t only have a strong foothold in art but also in fashion. Fashion is a true expression of individuals and their creative drive. Some brands tend to lean towards perfection with their pieces, while others, like Maison Margiela, are described by critics as “perfectly imperfect.” Imperfection can encompass a lot: raw hems, dangling sleeves, fringe and textures. All of these aspects aren’t frequently exhibited in the fashion industry today because society has this idea that perfect is ideal, but that is no longer the case. The idea of perfection in fashion is a falsity that stems from a perceived importance of a polished experience. It stems from the idea that humans need to be perfect and create perfection, which has translated into what humans think they should create.

Maison Margiela has a variety of pieces that have broken the internet, the most recent being their tabi ballet flat. This design goes all the way back to traditional Japanese footwear and has absolutely tested the boundaries of what uniqueness looks like in the fashion industry.2 It is all part of the brand goal to exemplify deconstructivism. According to If Chic, “Margiela’s early work, often featuring exposed seams, repurposed materials and an unconventional approach to tailoring.”3 Their brand identity and goal is to show how beautiful unfinished and imperfect can be.

Vivienne Westwood is a prime example of how unconventional style can be captivating. Westwood was known for her unique take on fashion design, but never let that change the way she did things. Her idea of perfection was in the imperfection. London Runway said of Westwood’s designs that, “Though some criticised the frayed edges and slashes in clothes that made them look ‘unfinished,’ it represented something more — a rebelling against societal norms of what fashion should be.”4 Westwood was one of the first female designers to redefine what fashion looks like in a way that had never been seen before.

This perspective has even seeped into museums. Fashion Unraveled was an exhibit done at the Museum at FIT. 5 It displayed unfinished, distressed and deconstructed clothing. It

1 Alan Beckett, “Michelangelo’s ‘The Entombment,’” February 19, 2025.

2 Durga Chew-Bose, “The Uncanny Appeal of Margiela’s Tabi Boots,” 2018.

3 IFCHIC, “Maison Margiela: The Art of Deconstruction — Why Fashion’s Rules Were Made to Be Broken,” n.d.

4 Amrit Virdi, “The Legacy of Vivienne Westwood,” Londonon Runway, n.d.

5 The Museum at FIT, “Fashion Unraveled,” The Museum at FIT, n.d.

got lots of traction and made people question what fashion can look like. Society has this idea that if you’re dressed a certain way, others will create an opinion; if you dress perfectly, you will be viewed as perfect. This is fueled by social norms and a mob mentality to fit in with your peers. Although if someone dresses unconventionally, don’t they catch your eye more? Unconventional can look perfect to some, and perfect could look robotic. The fashion industry today is challenging these ideas and striving toward imperfection and uniqueness.

The future of fashion will greatly benefit from being unique. In a world where things sometimes seem consumeristic and fake, this idea of perfection is unraveling at the seams. Imperfect is taking a stronger foothold in the fashion industry, with numerous brands trying to encapsulate what Vivienne Westwood and Maison Margiela have created. As a society, striving for perfection is impossible, but striving for intentional imperfection is attainable.

By Lily Kocourek

"Some stories don’t need another chapter; they just need to be left where you finally outgrew them."

It starts the way most ghosts return — quietly.

A name lighting up your phone, a message you never expected to see. The moment freezes, like a Polaroid developing in slow motion — edges first, then color, then the full, undeniable picture. It’s been a year since you last spoke — long enough to convince yourself the story has ended. But here they are again, tugging at a past version of yourself you thought you packed away for good.

In a winter that already feels far away, I met someone while I was still trying to put myself back together. I was just a teenager, unsure of everything, and drawn to someone who seemed magnetic and unpredictable with the kind of intensity that makes you crave more. Mysterious, handsome and impossible to pin down, they became the distraction I didn’t know I needed.

We spent weeks tangled in that almost relationship; movie nights that turned into mornings, conversations that meant everything and nothing. There was never a label, just a blur of moments that felt like more than they were. They’d pick me up late at night, drive aimlessly, talk about their future like they believed in it. I mistook their mystery for depth, their intensity for care.

There’s a peculiar kind of pain in something that fades instead of ending. You don’t get the clean break, the closure, the reason to move on. You’re left holding fragments of something that once was — half-developed pictures of a love that never fully formed.

As soon as winter had ended, summer had arrived, and with it, someone new. I told myself I’d learned my lesson, that I wouldn’t fall for the same type of person again. But then they came, crashing in — charming, witty and hard to forget. They were lighthearted, where the first had been dark — all jokes, confidence, and the occasional smirk. For a while, I let myself believe this time might be different.

But it wasn’t.

They liked me, but only in private. I never met his family, never a part of his real life. We went out, had fun, played the part, but I always felt like a secret; someone they didn’t want the world to see. And yet, as summer drew to a close, they told me they loved me.

It should have felt like a full-circle moment, hearing those words everyone wants to hear. But instead, it just made everything blur. Another almost. Another story that faded without ending.

Maybe it’s because ending something undefined feels impossible. You can’t mourn what was never officially yours, yet it still aches like a loss. So we pretend we’re fine. We delete their number, we tell our friends we’ve moved on, all while still replaying memories etched in our brain like our favorite melody.

So, a year later, when I received, “How have you been? I can’t stop thinking about you.” I froze.

It was them — summer’s fleeting spark. The same person who told me they loved me then disappeared. The same one who blocked me, moved on and made sure I knew it. For a second, my heart did that old, familiar thing; the pause before the fall. And then just as quickly, I felt something else: stillness.

It’s strange how the people who leave you broken think they can wander back in, like time didn’t happen. But I realized something in that moment: closure doesn’t come from the person who hurt you. It comes from finally recognizing that you don’t owe them any more of your peace.

I didn’t answer the text. I didn’t need to, because I’ve learned that not everything unfinished needs to be reopened.

Some stories don’t need another chapter; they just need to be left where you finally outgrew them.

And some entanglements are best left where they ended — reminders of who you were, not who you are now.

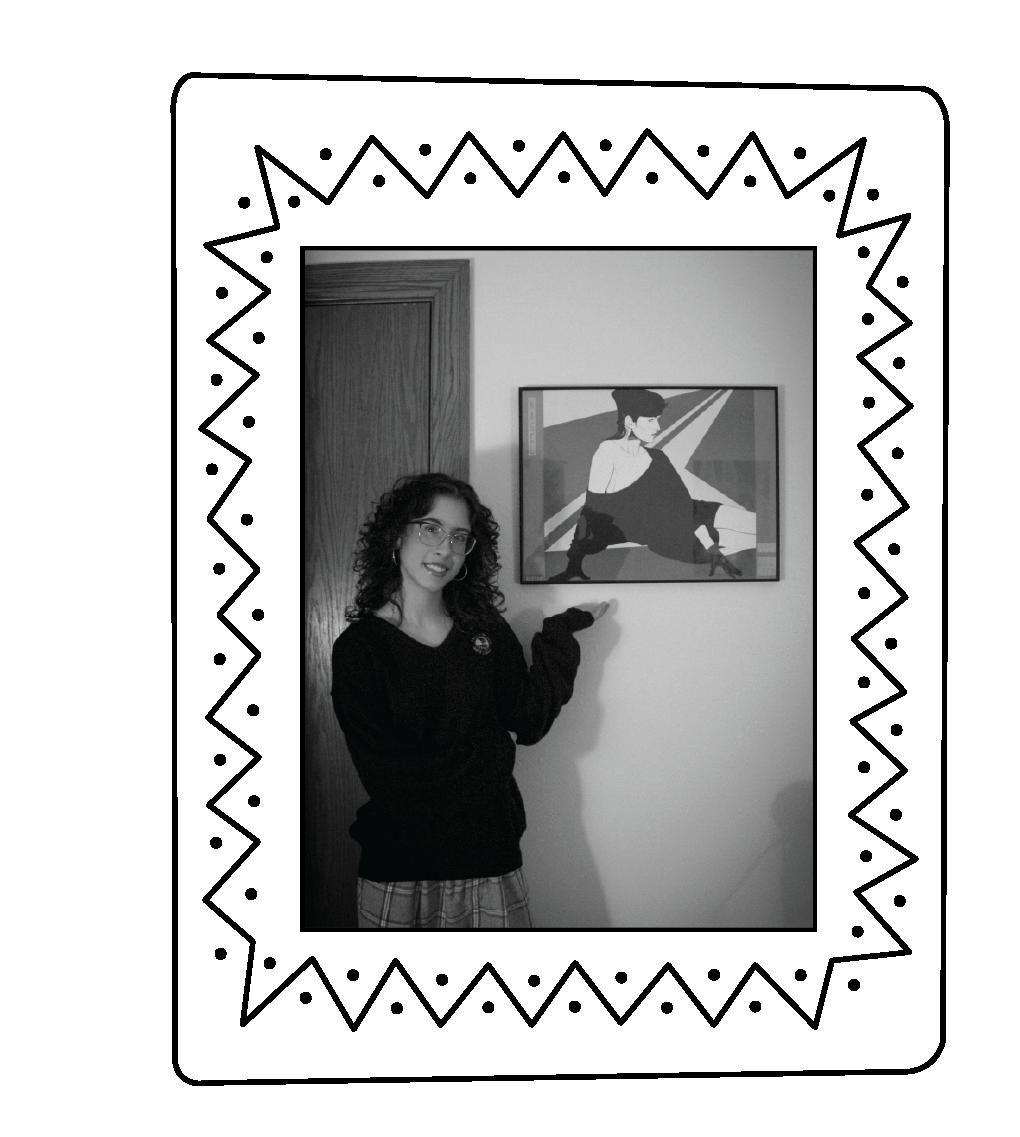

Written by & Photography by Elise Daczko |

Modeled by Mirabella Villanueva

hen moving into a new space, the activity I always look forward to most is decorating. I scan over the empty rooms, pondering where to place my furniture and which wall decor I can display to create an optimal atmosphere. I gradually move in my possessions, assembling and disassembling each room accordingly. But whenever I think I’m finished decorating, there always seems to be something missing. A warm lamp for the dark corner of the room? A small, eclectic trinket for the end table? I’ve found that you can keep trying to fill a space, but there will always be some miscellaneous piece of decor that could be added or altered.

The process of decorating a home is never easy, and it’s never finished either. According to the New York Post, 57% of homeowners reported that they felt their home was still a “work in progress.”1 Decorating a college apartment is even more difficult when faced with the reality that, as a student, you could be packing up your life and moving to a new home in one year’s time.

1 Tyler Schmall, “You’re not the only one putting off your DIY project,” New York Post, June 12, 2018.

“I want to make my space feel like home,” says Mirabella Villanueva, a third-year student at UW-Madison, “but I do have to be conscious of the stress of then having to move everything afterwards.”

Villanueva describes her decorating style as vintage and antique. The retro style inspires her to search for decor that makes her space feel welcoming and comforting.

“I like making my space feel like it’s back in time,” Villanueva says. “I think with our day and age, I definitely have a sense of escapism, and even though I wasn’t alive during those 60s and 70s eras, I feel nostalgic for them in a way.”

To create this vintage-inspired space, Villanueva has chosen to decorate with antique framed art, grandma-aesthetic trinkets and other retro decor that holds sentimental value for her, such as her pink rotary phone.

“It’s one of my favorite items,” Villanueva says. “I found it at one of the first antique stores I had ever been to back in California. I definitely see myself using the phone as decor and maybe even as a functional phone in a future home.”

Regarding the move from her home in the San Francisco Bay Area to her fresh-

man-year residence hall, then finally to two consecutive apartments, Villanueva remarks that living in an apartment has given her more freedom to decorate the spaces beyond her bedroom. She now enjoys spreading her homely decor to the kitchen, bathroom and living room. While filling the large space was overwhelming at first, Villanueva eventually came to understand the joy in filling it little by little. In a world of overconsumption and lifestyles centered around materialistic possessions, she notes that an unfinished space doesn’t necessarily need anything more.

“You have your whole life to discover how to decorate your home,” Villanueva says. “There are definitely elements of the apartment that are unfinished, but overall, when I look at all of my items that I own, I don’t look at my collection as a whole as unfinished. I just think the space is not at its full potential yet, and that’s okay.”

The decorating process is never complete, but there is beauty in that. From her timeless pink princess phone to her Cicely Mary Barker “Flower Fairies” print, Villanueva uses her decor not only to make her home into a comfortable space, but also as a representation of the past stages of her life.

“When decorating a space, I obviously feel happiness, but I also feel achieved, in a way, because the decor shows different phases of my life that I can associate memories with,” Villanueva says.

In short, there is no need to stress about trying to make your home perfect or buying all of your decor at once. Instead, try to enjoy the exciting journey of adding to your decor throughout your lifetime. Decorating is a gradual process that will likely always be unfinished, but the journey is where you will find the true joy of making your house into a home.

Written by & Photography by Hannah Byma

The music ends, the lights dim and you are left in momentary stillness — the blackout before the final bow. As you step softly to center stage with pointed feet and shaky breath, a spotlight clicks on, illuminating your farewell. How do you say goodbye to this, knowing it will never truly leave you?

Dance is often regarded as one of the most intimate and powerful forms of expression, perhaps acting as the only truly universal language. Dancers are valued for artistry, strength and individuality, which make the most difficult steps appear to come easier than breathing. Often over decades, they form an intimate relationship with

their art, and a final bow is the culminating moment where talents and history with the art form are recognized and celebrated.

Moments like this don’t happen by coincidence — they are built by years of devotion and dedication. Thousands of hours in the studio, hundreds of

pairs of pointe shoes and black socks, countless tears and a whole lot of love all stand behind it. We pursue perfection, despite knowing it is virtually impossible to reach. But the blood, sweat and tears could not have been given without the gratitude, reflection and fulfillment that accompany it.

When your body is your instrument, you learn how to hold respect and responsibility in your lungs, and vulnerability in your veins. After millions of repetitions, demi-plié becomes home, a safe haven to return to when the rest of the world is in chaos.

Walking into a dance studio means finding a new kind of community, one rooted in integrity that values intentional presence and hard work above all. The spaces you occupy have magic in the air, something that allows your body to release and create from the inmost being. Here, you hold deep respect toward your teachers and those you teach, while unspoken connections build along the ties of 5, 6, 7 and 8.

Eventually, you’ll wake up and realize that being a dancer has not just changed how you move through the studio, but how you move through the world. This response is born of emotion and time commitment, as well as neurobiological

patterns. Neural circuits are built through training, so those years of creating muscle memory were actually reshaping your brain chemistry and identity.1 Every class, rehearsal and performance activates the brain’s bonding chemistry (dopamine, endorphins, serotonin and oxytocin).2 Thus, when you step away from such a consistent and transformative part of your life, it often makes you feel like you’re losing an integral part of who you are.

Though you might grow reliant on the comfort of battered pink pointe shoes and the hard-earned calluses they produced, not everything goes according to plan. Though dancers end their careers for many reasons, the luxury of choice isn’t always available: sometimes a career-ending injury makes the decision for you.

Unforeseen goodbyes are never easy. But even after a final bow, the passion and the journey leave imprints on your heart that never fully leave you. The brain synapses, core values and lessons learned stay strong in your mind. It might feel like you’re leaving something behind, or leaving a part of yourself unfinished. But maybe that’s the point; there is beauty in allowing something to remain so close to your heart.

It enriches the way you experience life, in all of its messiness, and gives you a perspective and lifeline to which you can hold on. The dedication to the journey and the value of hard work required to be a dancer translates to professional life, relationships, love and almost all foundational life values. Correcting even the tiniest of movements teaches precision and attention to detail that strengthens your ability to be attentive to the beauty in the small moments.

Learning to appreciate this process and perspective opens your eyes to the rest of the world. The magic of the little moments will become brighter as you realize it is not the final bow that is most rewarding, but the process of getting to the spotlight. The beauty is in what you take with you. If you find yourself having to part ways with a skill, place or sport — anything that has become intertwined in your heart — try redefining its presence instead of saying goodbye.

What will you take with you as the curtain closes? Is there a way you can keep the velvet cracked, shifting the stage lights to irradiate the steps leading offstage into a whole new world?

1 Scott Edwards,. “Dancing and the Brain,” Harvard Medical School, 2015. 2 Olivia Foster Vander Elst, et al, “The Neuroscience of Dance: A Conceptual Framework and Systematic Review,” Science Direct, July 2023.

No matter how hard you try, your eyes flutter shut. After half an hour, you’ve only managed to flip the page two or three times. It’s been a week of trying to get into this book, and it has been waiting patiently in line in your to-beread pile (TBR). But when given its time to shine, it disappoints.

Why is it so hard to throw in the towel and decide to leave a book unfinished?

DNF’ing — an acronym standing for “did not finish” — is a popular phrase in book-related subsections of the internet, like BookTok. BookTok is a community of passionate readers who create book-related content on TikTok, and they have taken the reading world by storm. In many ways, these online book conversations have turned reading into a social activity rather than just a personal one. DNF is the term thrown around when people discuss books they’ve started that they do not feel compelled to finish. The conversation usually starts when someone is debating whether or not to stop reading a book, or if they should power through in hopes that fulfillment is on its way.

With floods of opinions on popular titles, it is easy to be convinced that you’re picking up the best book on the shelf with each new recommendation taking over the internet. Being passionate about something makes a person defensive over it, and BookTok comments are filled with readers who have a lot to say to those who don’t connect with their most beloved books.

Many book lovers express firm beliefs against DNF’ing a book — they swear it’s worth it to push through, and that some stories don’t get good until partway through. This ideology has created levels of guilt for some readers. It’s almost become taboo to even posit the idea of DNF’ing a book.

But with your ever-growing TBR list, it’s time to start making your own executive decisions on when you should leave a book unfinished. You don’t need someone else’s permission or input because everyone has different genres they’re drawn to, unique tropes they enjoy and authors they swear by.

So, when is it better to leave a book unfinished? A rule of thumb I like to follow is if I’m not invested after the first hundred pages, it’s usually a sign that it’s not the right book for me (or not the right season of my life to read it). I tend to become heavily invested in the stories I enjoy, and when a book can’t elicit that glorious, page-turning frenzy, it’s just not worth it.

Sure, there are exceptions to every rule; one of my favorite series took me about halfway through the first book and a partial DNF before I was finally enchanted by it. But that leads directly

to my next point: DNF’ing doesn’t have to be so black-and-white. You don’t have to sign divorce papers and swear to cut full contact with a story you’re unsure about finishing. It’s okay to put a book down and come back to it at a later date. Your relationship with a book doesn’t have to be finite.

Let’s switch the narrative surrounding unfinished books; they’re an opportunity to learn what you do and don’t like to read, and sometimes a story to literally bookmark for a later date. Similar to the TBR list, why don’t we embrace DNF piles? Who knows — you might come back to an unfinished book after a month, or a year, and find a whole new meaning depending on where you’re at in life. Deciding which story to spend your time with is a personal choice, and life’s too short to force yourself through ones you don’t like — don’t let the guilt of DNF’ing stop you from starting your next favorite book!

Written by Maddy Scharrer, Editorial Director | Graphic by Molly Anders