Problem Solving with Python

Problem Solving with Python

Using Computational Thinking in Everyday Life

Michael D. Smith

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

The MIT Press

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 mitpress.mit.edu

© 2025 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used to train artificial intelligence systems or reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these other wise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Times New Roman by Westchester Publishing Services. Printed and bound in the United States of Amer ica.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-0-262-55284-4

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe, Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia | Email: gpsr.requests@easproject.com

1 Read a Children’s Book 1

Problem Solving, in General 1

Problem Solving, in Detail 2

Our First Computational Problem 4

Imagine a Specific Instance 5

Sketch Using Computational Thinking 5

Capturing This Thinking 7

An Environment for Coding 7

Our Generic IDE 8

Our First Pseudocode 10

Comments 10

Commands and Input Parameters 10

Scripts Versus Execution 11

Our First Error 12

The Interactive Interpreter 12

Code and Transcript Blocks 13

Interacting with the Interpreter 14

The Interpreter as a Calculator 14

Python Help 15

Revisiting Our First Error 15

Undefined Names 16

Talking Through Your Confusion 16

Naming a Computation’s Result 17

Debugging 18

Showtime 18

Printing to the Console Pane 19

Statements, Objects, Attributes, and Types 19

Namespaces 20

Strings and String Literals 21

Variables 22

Valid Names in Python 22

Terminology Illustrated 23

Aliasing 24

Reading Two Lines 26

Carriage Returns 26

Reading an Entire Story 27

Creating a Loop 28

End of File (EOF) 29

Three Major Tasks 30

Testing a Condition 31

Exiting the Loop 31

Indentation 32

Loop Until 32

Any Book 34

This Problem, in General 35

Historical References to Computational Thinking 35

2 Grab the Dialogue 37

What Is the Current Task? 37

A New Problem 38

Splitting the Problem into Small Pieces 39

Reuse 39

Switching Between Goals 41

Finite State Machines 41

Error Handling in FSMs 42

Encoding the State Information 43

This or That 44

Work on a State 44

Strings as a Sequence of Characters 45

Membership Test 46

Coding a Transition 46

Indexing and Slicing 47

For- Loops 48

String Find 50

Design Patterns for Error Handling 51

Never Go Too Long Without Testing 51

Concatenation, Overloading, and Shorthands 52

Off-by- One and Other Potential Errors 53

Testing 53

Beware of Hidden Assumptions 55

Function Composition 55

Abstraction as Information Hiding 58

There Is No Character 58

3 Replace Text with Emoji 59

Internationalization 60

Encoding 60

Standards 62

Unicode 62

A New Problem 63

Decomposition to Reduce the Problem’s Complexity 63

Strings as Immutable Sequences 64

Encode an Emoji in Unicode 65

Multiple Dif ferent Replacements 67

Feeling Overwhelmed? 67

Functions 68

Function Definitions 69

The Actual Function Definition and Its Invocation 70

Function Execution 72

Abstraction, Decomposition, and Algorithms 73

Definition Before Use 74

Python’s Special Variables 74

Docstrings 76

Getting a Feel for Abstraction 76

Another Kind of Abstraction 77

Lists Are Sequence Objects 78

Abstraction Barriers 80

Methods 81

Modules 82

Avoiding Main 84

Pure Functions 84

4 Query a Web Resource 87

Packages and Libraries 87

APIs 88

A New Problem 88

Searching Wikipedia 89

The Client-Server Programming Model 91

Resources, Transactions, and Protocols 92

The URL 93

The Programmable Web 94

Python Dictionaries 95

An HTTP Response 98

The Response Header 100

JSON and the Response Body 101

Enumerating Answers for HOLLIS 103

Beyond Printing 104

Blocking and Non- Blocking Function Calls 107

5 Play Guess-a- Number 109

Guessing a Number 110

The Player’s Guess 112

Type Conversion 113

Try and Recover 114

The Game Loop 115

Testing Our Proposed Solution 116

A Networked Architecture 116

Its Sequence Diagram 119

When to Use a New Library 120

Sockets in Action 121

Specifying the Other Party 122

Sending and Receiving Messages 123

Size Matters 125

Encoding Again! 125

A Simplified Networking Interface 126

The Server 127

A Connection 128

Picking Up a Call 129

The Conversation 129

Programmer Beware 131

Run It! 132

6 Do You See My Dog? 135

Numbers and Knowledge 136

Do You See My Dog? 137

No Interpretation, Please 138

Reading a Hexdump 139

Hexadecimal Explained 140

Converting Between Number Systems 141

Does the Computer See My Dog? 142

Painting a Picture 143 Bits 144

One Finger, No Thumb 145

The Digital Abstraction 145

Bits, Bytes, and Nibbles 146

Setting a Pixel’s Color 146

Saturation 147

Overflow and Underflow 148

Finding Edges 149

7 Many but Not Any Number 153

Floating- Point Numbers and Numerical Computing 153

Computers Struggle with Arithmetic? 154

The Range of an FP Number 155

Precision 155

Illustrating This Issue of Precision 156

Getting Started 157

One Bit at a Time 158

Searching for the Smallest Difference 158

FP Errors Accumulate 160

8 What Is My Problem? 161

Data Science 161

Images as Data About the World 162

Yes, You Must Clean Up 163

Understanding What Might Go Wrong 163

Noise and Its Removal 164

The Power to Create New Realities 165

A Process for Eliminating Photobombing 165

This Data Is Not Wrong, but 166

Zero Out the Unnecessary Details 167

No Visible Difference 171

Image Steganography 172

Where Is That Pixel? 172

And How Did We Get There? 173

Visualizing a Traversal 173

Inverting a Pixel’s Color 174

Naming the Traversal 175

Specifying the Range You Want 176

Storing a 2D Array in Memory 177

What You’ve Learned 178

9 Find a Phrase 181

A Complex Problem-to- Be-Solved 181

Some Basic Facts 183

Which Algorithm? 183

Algorithms, Formally 184

A Well-Studied Specification for String Matching 184

Is a Specification an Algorithm? 185

A Brute- Force Algorithm 186

A BF-String-Matching Program 186

One Algorithm, Multiple Implementations 188

Evaluation 189

Evaluation in Context 189

Measuring Performance 190

How Do We Do Better? 192

Loops Are Where the Action Is 194

Computational Complexity 196

Computational Complexity in Action 196

Problem Unsolved 201

10 Build an Index 203

Strings to Numbers 204

A Simple Hash Function 205

Updating a Hash with O(1) Work 206

Allow Collisions 209

Other Applications of Hashing 212

Indices for Fast Data Retrieval 212

Hash Tables 213

The Speed of Array-Index Operations 213

With High Probability 215

Collision Resolution 215

Specification for Creating a Book Index 216

Building Top- Down 216

Updating the Index 219

Sort and Strip 222

11 Discover Driving Directions 225

A New Approach to Programming 225

Driving Directions, a Formal Specification 227

Parallels with Finite State Machines 228

Solutions with Specific Characteristics 228

Let’s Walk Before We Drive 228

A Random Walk 230 Will It Work? 230

A Short Walk, Please 231 No Loops 231

Only Visit New Spots 231

A Dog Walk 232

Simulation 234

Object- Oriented Programming 236

Classes 236

Building an Instance 238

Self and Instance Attributes 240

Methods 241

Representation Invariant 242

Magic Methods 242

Building on Others 244

12

General Maps 245

Keeping Track 245

Remembering How We Got There 249

The Solution 251

Depth- First Search (DFS) 253

Breadth- First Search (BFS) 254

Informed Searches 254

Divide and Conquer 257

A Specification for Sorting 258

Sorting in Python 259

Sorting in Descending Order 261

Sorting with Your Own Comparison Function 261

Sorting Playing Cards 263

Time Complexity of Brute- Force Sorting 264

Binary Search 265

Divide-and- Conquer Algorithms 267

From Split to Merge 268

Iterative Merge Sort 269

Recursion 270

Iterative Factorial 272

Recursive Merge Sort 273

Beckett’s Challenge 274

Its Base Case 274

The Play with a Single Actor 275

Looking for the Pattern 276

A Polished, Full Solution 277

13

Rewrite the Error Message 279

The Mistakes We Make in Problem Solving 280

Our Problem-to- Be-Solved 281

From the GUI to the Shell 283

Understanding Paths 284

From Paths to Programs 285

Redirecting Inputs and Outputs 287

Which Output? 287

Pattern Matching 288

Wildcards in the Shell 289

Regular Expressions 290

Finding Simple Words 290

Matching Metacharacters 291

Using REs 292

Finding Filenames 294

Python RE Extensions 295

Putting It All Together 297

Shell Pipes 297

Scripting What the Shell Did 298

Concurrency 299

Making python32 Look Like python3 299

14 The Dream of Bug Fixing 303

Finding All Bugs 304

Decision Problems 306

Uncomputable Problems 307

An Analysis That Finds a Bug 308

Running Our Simple Analysis 309

A Tool for Running Analyses 310

Grabbing a Function with a Syntax Error 312

Analyzing Other Functions 313

Using the Input 313

A Nontrivial Decision Problem 315

An Indecisive Decision Function 317

Insight from Indecision 318

Specifications Without Implementations 320

15 Embrace Runtime Debugging 321

The Duality of Code and Data 323

Breakpoints and Runtime State 323

Inserting a Breakpoint 324

Inserting a New Statement 326

Indenting That Statement 327

Launching a Script from Another 329

Instrumenting a Script 332

REPL 335

16 Catch Them Early 337

Divide-by-Zero Bugs 338

A Silly Coding Error 339

What’s Hidden? 342

Why Compile? 343

Finding Type Errors 344

To Squiggle or Not 344

Dynamic Typing 345

Why Types Are Interest ing 346

Types Versus Values 347

Dynamic Type Checking 347

Static Type Checking 348

Type Hints 350

No Free Lunch 350

17 Build Prediction Models 353

Predicting Home Prices 354

Your Sister’s Data 354

Solving This Problem Ourselves 356

Machine Learning 358

Labeled Training Data 359

ML Workflow 360

Getting a Feel for the Data 361

Set the Prediction Target 363

Pick Some Features 363

Fit the Model to Our Data 364

Predicting Unseen Data 365

Model Validation 366

Making the Fit Just Right 367

Bias in ML 369

Classifying Comments as Toxic 370

More Art than Science 371

18 Use Generative AI 373

Navigating the Jagged Frontier 375

My Use of GAI 377

Large Language Models (LLMs) 378

The Operation of LLMs 379

Complexity from Simplicity 380

Training a Neural Network 381

Two Pieces to Problem Solving with GAI 382

An Easy Request? 383

Write the Script Ourselves 384

Ask ChatGPT 386

Is This Task Within the Frontier? 388

The Expanding Frontier 389

How to Problem-Solve with an LLM 389

Writing Good Prompts 391

Final Thoughts 393

Acknowledgments 395

Index 397

Welcome

This book tells a story about computing, computational thinking, and computational approaches to problem solving. Computational thinking, paired with today’s digital devices and the skill of computer programming that you’ll learn in this book, will empower you with a new approach to solving the little problems you encounter in everyday life.

Do you need to find the prime numbers between 1 and 100, convert a temperature in Fahrenheit to Celsius, or use bisection search to approximate the square root of a number? No? Well, neither do I. The calculator on my smartphone computes square roots just fine, and a quick Google search will find the answers to the other two problems. Yet if you pick up most any other book on learning to code, it will subject you to a lengthy procession of tiny programs that solve basic math challenges. Such programs helped me to learn the syntactic rules of a new programming language, but they were not how I learned to use computation to solve the problems in my life.

There is another way. In this book, you will learn to solve problems with computation by writing programs that grab data from the Internet, modify a digital picture you’ve taken, and help you understand how Google finds the answers to your questions from all the world’s websites in under a second. Yes, that’s amazing.

Learning to program is a power ful skill when you si multaneously learn how to problemsolve. This book will teach you how to solve the computational problems you encounter in everyday life. And if you feel inspired, it can also help you imagine ways in which we might collectively grapple with the big, thorny problems facing our society. For programming has never really been a solitary activity disconnected from the world. It is a tool of a thriving community full of increasingly diverse individuals building products and services that we each use every day of our lives.

This book will introduce you to this community, which will be an invaluable resource for you when you inevitably have questions. But you’ll find that this community can be much more. It can also be a source of promising approaches to your problems and pointers to rich resources on which you can build. And if you decide to use your new literacy and capabilities to tackle problems beyond those in your own backyard, you will find colleagues in this community with whom you can partner.

What You’ll Learn

A good story is not only fun to read, but it can expand your view of the world. I have tried hard to avoid making this book a tortuous march through a set of dry, disconnected topics. Every technical concept I cover is taught through a short story involving a problemto-be-solved. I have then ordered and threaded these individual short stories together with an overarching storyline.

I’ll speak about this storyline in a moment, but you are probably thinking, “Wonderful, but what specifically will I gain from reading this collection of stories?” Great question. I hope you learn the following:

1. To solve problems using computers. In general, problem solving involves thinking methodically, expressing your goal without ambiguity, decomposing your specific challenge into manageable subproblems, and solving these subproblems through a variety of proven approaches.

2. To address real-world problems and transform them so that they can be solved with the help of a computer. In general, this involves gaining experience in representing and processing information in digital formats.

3. To understand how computers, networks of computers, and their associated software systems operate and communicate.

4. To apply the power of algorithms, abstraction, decomposition, concurrency, and many other computer science concepts in problem solving.

5. To reason about the limits of computing machines and identify the limitations of specific software solutions. You’ll also develop a toolbox of techniques for finding design faults and diagnosing erroneous outputs.

6. To write reasonably robust and efficient code in Python using procedural and objectoriented approaches, and to use and understand Python modules and packages written by others. You will gain the confidence to be a contributing member of the worldwide Python community.

Don’t worry if the technical terms in this list are unfamiliar to you. You will soon understand what they mean and how they can help you to become an amazing problem-solver.

I want to emphasize that this book isn’t trying to turn you into a computer scientist or a professional software engineer. You can use it to become an individual in these professions, but I’ve written this book for anyone who finds that they need to understand computational thinking and computer programming to accomplish their personal and professional aspirations. If that’s you, keep reading!

The Python Programming Language

The last of the listed learning goals mentions Python, which is the programming language that you’ll learn in this book. It is a popular language, used by millions of people around the world, and it is a great starting point for learning computer programming. Let me try to explain why with as few technical terms as possible.

I chose to base this book on Python because it emphasizes readability. I believe that you’ll read more code than you’ll ever write. This isn’t very different from our experiences with our native languages, if you think about your typical day. You will read a lot of code in this book, and this will make you a better writer of code. In fact, when I do ask you to write Python code, I’ll encourage you to write in a manner that is easy to read and understand.

Readability is impor tant because code is dense, with lots of things typically happening in each statement. This detail, as we will discuss, is necessary for the computer to understand what it is that you want it to do, but humans don’t like too much detail all the time. Just as we sometimes skim dense documents to get the gist of what’s going on, we’re going to want to develop this same skill in computer programming. Python’s emphasis on readability will help get us started toward this impor tant skill of skimming code to understand its gist.

Python is also one of the fastest-growing languages in terms of popularity. What this means for us is that the growing community of Python users is constantly producing Python code that we can use in our projects. In other words, we don’t have to write our code using only the primitive commands shipped in the core language. We can quickly begin tackling hard problems because others have written and shared Python code that we will use as building blocks. What do I mean, exactly? Well, think about how hard it would be to build a wood-frame house if you not only had to construct the wood frame for the floors, walls, and roof, but also had to chop down the trees and slice the logs into boards. Constructing the frame is hard enough; adding the latter work makes the project something only a historical hobbyist would love. Working in a programming language with a growing and vibrant community matters, as we will discuss more in the chapters to come.

Beyond Python

I want you to notice that the first five learning goals above don’t mention Python or any other programming language. This is because we need a programming language to help us to practice thinking in a computational manner. Once you’ve developed that skill, it’s not that difficult to convert your Python scripts (i.e., your programs written in Python) into a dif ferent language.

In fact, the new language might not even be another traditional programming language. In the last chapter, I will show you how to take what you’ve learned about directing a machine in Python and apply this knowledge to create effective prompts in English for directing a generative artificial intelligence (GAI) chatbot to do your bidding.

Three Acts

I have chosen to structure these lessons about computers and computation as a theatrical drama in three acts. It is a drama in the full sense of the word. Each story (i.e., chapter) begins with a problem that we’ll take apart and then solve.

But I like the image of a drama for an additional reason. As some of you might already know, the word “drama” comes from the Greek word dran, which means to do, to act. And act you will.

I ask that you don’t passively read each of the chapters that follow. As explained on the book’s companion website, you can (and should) execute and edit every piece of code in this book. Doing so will deepen your understanding of the concepts we cover. It will allow you to answer the “I wonder” and “what if” questions that pop into your mind.

I’m serous. Don’t just read. Experiment. Try to break things. Try to make the code in this book do things that interest you.

Programmers and Playwrights

As you work your way through the code examples in this book, I’d like you to think of yourself as a programmer and a playwright. Paul Graham of Y Combinator fame wrote in 2003 that hackers and painters, seemingly different professions, are quite similar in that both groups hone their skills by doing.1 While I have great respect for Paul, I think programmers and playwrights are a more apt twosome. Why? It has to do with the immediacy of the feedback they receive on what they write.

Playwrights who test their early drafts with a theatrical troupe receive immediate feedback on the success of what they write. Those playwrights can compare what they had in mind while writing to the results when the scripts are performed. Paying close attention to what works and what doesn’t, they can build a masterpiece.

Likewise, the best computer scripts come not fully formed from a programmer’s mind but blossom over time as the programmer tries things and adjusts to feedback, from both the machine and their peers. Programming, like playwriting, is a craft that improves with feedback, practice, and community.

The Hump

The skills in any worthwhile craft take work to develop and master. By opening this book, you’ve taken the first step toward developing the craft of solving problems with computation, a skill of growing importance in our modern world.

But I need to be honest with you. You will work hard to develop this skill. Yet, just like learning how to read and write in any language, you’ll be amazed when things fi nally click.

This book will help you to get over the hump we all experience. On one side of this hump, it feels as if you’re drinking from a firehose and you have no idea what you’re doing. But on the other side, you’ll find yourself making connections between concepts, writing parts of your programs where you don’t have to look up every piece of syntax, and running scripts that make you feel proud and power ful.

Besides helping you get started with programming, this book will teach you to interpret the immediate, often frustrating feedback you’ll get as the computer performs the first versions of your scripts. Knowing what to do when things fail will give you the tools you need to succeed.

1. Paul Graham, “Hackers and Painters,” May 2003. https://www paulgraham com / hp.html

Problem Solving

I strongly believe that doing is the best path to learning, but what you’re asked to do can be engaging and inspiring, or it might just be dreadfully boring. Alfred Hitchcock said that “drama is life with the dull bits cut out,” and cutting out the dull bits is my goal in teaching you the art and skill of computer programming.

This book won’t waste your time on a parade of programming language features, a dictionary of computer science concepts, and the small, typically mind-numbing code examples that demonstrate them. You can find ample examples online when you need them.

Instead, we will spend our time together in each chapter developing solutions to widely encountered problems. For example, how does one grab data from a text file? How do two individuals on different digital devices communicate and cooperate with each other? How can you manipulate a digital image to portray something that never occurred? And can search, which is at the heart of so many tools, work quickly over a large collection of data?

Every computational concept and programming language feature that I cover is taught within the context of a problem-to-be-solved. I’ll encourage you to work through each problem, and periodically, I’ll give you the chance to practice what you’ve learned. This work will both deepen your understanding of the concepts covered and develop your skills as someone capable of using computation to solve real-world problems.

Learning to Problem-Solve in Three Acts

Structurally, the book segments the problems into three acts. The acts correspond to the stages that I envision in your evolution from someone just learning to write your own scripts to someone that uses programming and computational thinking as skills in your everyday work.

• Act I (the setup) assumes a novice status. It introduces you to the steps involved in problem solving with computers, and it illustrates these steps by asking you to solve eight easy-to-understand challenges. Each challenge highlights skills that you’ll use often in working with computers.

○ The problems in the chapters 1–8 are ordered so that each builds on the previous chapter, introducing you to new computational ideas and concepts.

○ These chapters encourage you to be curious, try things, make lots of mistakes, and ask lots of questions. They also equip you with simple approaches to finding and fixing faults and errors in your scripts.

○ By the end of act I, you will have gained significant practice in translating a rough problem statement into a sequence— a worklist —of computational tasks that, when performed, will solve your problem. Worklist processing is the first of several problem-solving techniques that you’ll learn.

○ In terms of computational thinking, this first act focuses on two fundamental ideas: decomposition, which is about breaking a daunting challenge into small, manageable tasks, and abstraction, which allows us to build simplified representations of the problem’s essential elements. These ideas are two of the five cornerstones in computational thinking.

• Act II (the confrontation) is when you gradu ate from novice to apprentice of computational thinking and problem solving. This act teaches you to tackle real-world problems that are more complex than the easy-to-understand challenges of the first act.

○ Chapters 9–12 cover four problems related to search, a task that is at the heart of many problem-solving approaches. Through these challenges, you’ll experience the power of abstraction and move beyond solutions consisting of simple worklists.

○ A key aspect of real-world problems is that we can no longer be satisfied with any solution to a problem; we need to create solutions that adhere to specific constraints, such as how long we are willing to wait for a program to run. This act is where you’ll learn about a range of problem-solving techniques and the algorithms and data structures behind these techniques. Algorithm design and data repre sentation are two more cornerstones of computational thinking.

• Act III (the resolution) moves from a focus on computational techniques to an emphasis on computational tools. As you become a skilled practitioner, you’ll use many dif ferent tools and correspondingly dif ferent languages to direct these tools. Common across all computational tools is our desire to write short, unambiguous scripts that instruct these tools to solve the problems that interest us. And what keeps us from this goal? Two things: (1) identifying the right computational tool and (2) understanding why our set of instructions to this tool didn’t work as expected.

○ Finding the right computation tool is a matter of understanding and exploiting patterns, as you’ll see in chapters 13–18. Pattern recognition is the final fundamental idea in computational thinking, and it is at the core of machine learning and generative AI. If you can recognize the patterns in your problem, you can identify a computational tool to exploit them.

○ While the right tool will make a seemingly hard problem simple to solve, all computational tools have limitations. Skilled practitioners know the limitations of their tools and how they can fail to achieve desired results. Throughout this final act, you’ll learn to recognize and, when possible, overcome these limitations.

Layering and Exploiting Connections

Nowhere in this book will you find a single section on a programming structure like looping or an impor tant computer science concept like abstraction. Instead, the text will regularly return to previously introduced topics, and when it does, I will layer on new nuances and new connections. This layering will help you to grow from novice to skilled practitioner.

This is a problem-solving-first approach to learning concepts in computer science and becoming proficient with the syntax of a programming language like Python. Starting simple and building toward complexity through a carefully ordered range of problem contexts is a proven way to learn and retain information.

Furthermore, experts become experts because they see the similarities between problems, and this ability helps them get quickly started on a new problem. Experts almost

never start from a blank page. They start with an approach that solved a similar problem and then adapt it for the differences they see in their new problem. We will do the same thing in coding by often starting from something we have previously written.

Getting Started

The one exception to this never-start-from-a-blank-page approach is the first chapter, where I assume that you have no prior background in coding or computational thinking. It introduces you to the general problem-solving process, gets you started in an environment where you’ll practice problem solving with computation, and explains some basic statements in programming and the Python programming language. This is impor tant foundational material that could have comprised a complete chapter, but I wrapped it in a problem-tobe-solved, just like all the other chapters. That’s because a problem-solving approach to learning this material works as well for it as for the rest of the book’s material.

There is, however, a cost to organizing the introductory chapter with a problem-to-besolved: it necessarily takes you on a longer journey (i.e., it is nearly twice the length of the average chapter). Don’t let this discourage you. Once you’ve solved your first problem, the rest will fall into place quickly.

This is what awaits you in this book. It is an approach that has engaged students intrinsically motivated to learn programming and those who thought they could never do it. No matter which you are, I’m glad that you picked up this book. You are about to experience the beauty and power of computational thinking to solve real-world problems, especially those that excite you. And as you learn to write your own scripts, I hope you will, like the best playwrights, develop your own voice and your own unique style. Then what you do with this new and wondrous skill is up to you.

Read a Children’s Book

I love a good story that opens with action and suspense. The action in this opening chapter will be to solve our first computational problem and write our first Python script These two things are linked. The goal of a Python script is to get a computer to act in a certain way, to perform one or more specific computations. And if we correctly do the problem-solving work that sets up the writing of such a script, the computations that result will be a solution to our problem.

The suspense? Well, you won’t just read about what it takes to write a script that solves the problem before us. You will actively try many different short scripts that may move us closer to solving our problem. For each script, we will pay careful attention to how the computer reacts. I will help you to understand each response, and through this experience, you’ll begin to build a mental model of what it takes to write a script that causes the computer to perform as we desire.

This trial-and- error approach is not that much different from what we did as young children as we learned how to communicate with those around us. There was a language that the adults were speaking, but we didn’t yet understand it. We wanted to be part of the action, so we would string together some words from this language and notice how the adults reacted. By paying careful attention to their reactions, we built a mental model that mapped our ideas to what statements we needed to say to express those ideas in that language.

Problem Solving, in General

But we want to do more than just develop this mental model and learn to express simple concepts in Python. We want to solve computational problems. To solve a problem, we will begin by imagining and then sketching out a set of actions that, if followed, would solve the problem before us. This set of actions is the content of the script that we want our computer to follow.

In the theater, scripts are useful when we can read them and follow their stage directions. If a script uses a language or a lot of terms that we do not understand, it is gibberish to us. The same is true for a computer script. We need to express the script using a language and terminology that the computer understands. Python is a language the computer

understands, and this is where our mental model of what we can express in Python comes into play. The second part of problem solving with computation, then, is the translation of our imagined set of actions into Python.

If you keep in mind the elements involved in good storytelling, you can use them to become a good problem-solver. Just as there are different narrative structures that help writers organize their stories, there are dif ferent problem-solving strategies that we will use to structure our scripts. Just as storytellers need to decide what narrative details are necessary to include and which can be left out, we too will have to decide which problem details are pertinent to finding a solution. And just as storytellers take advantage of cultural knowledge to streamline their narrative, we will learn to use prominent features of our computer and its programming language to produce efficient and easily understood scripts.

Writing a story or a script, however, is not the end for a storyteller or for us. Stories are meant to be read and scripts performed. Just as storytellers hope to elicit par ticular reactions from their readers, we hope that our scripts will produce par ticular results when executed by a computer. Unfortunately, the first draft of a story doesn’t always elicit the reaction a storyteller hoped it would, and the first versions of our scripts often won’t produce our desired outcome. But that’s OK! We will figure out what failed, fix it, and begin again.

Terminology

I’ll talk about our scripts (i.e., our computer programs) as being executed or run. Both terms simply mean that the computer performs the actions dictated in the script.

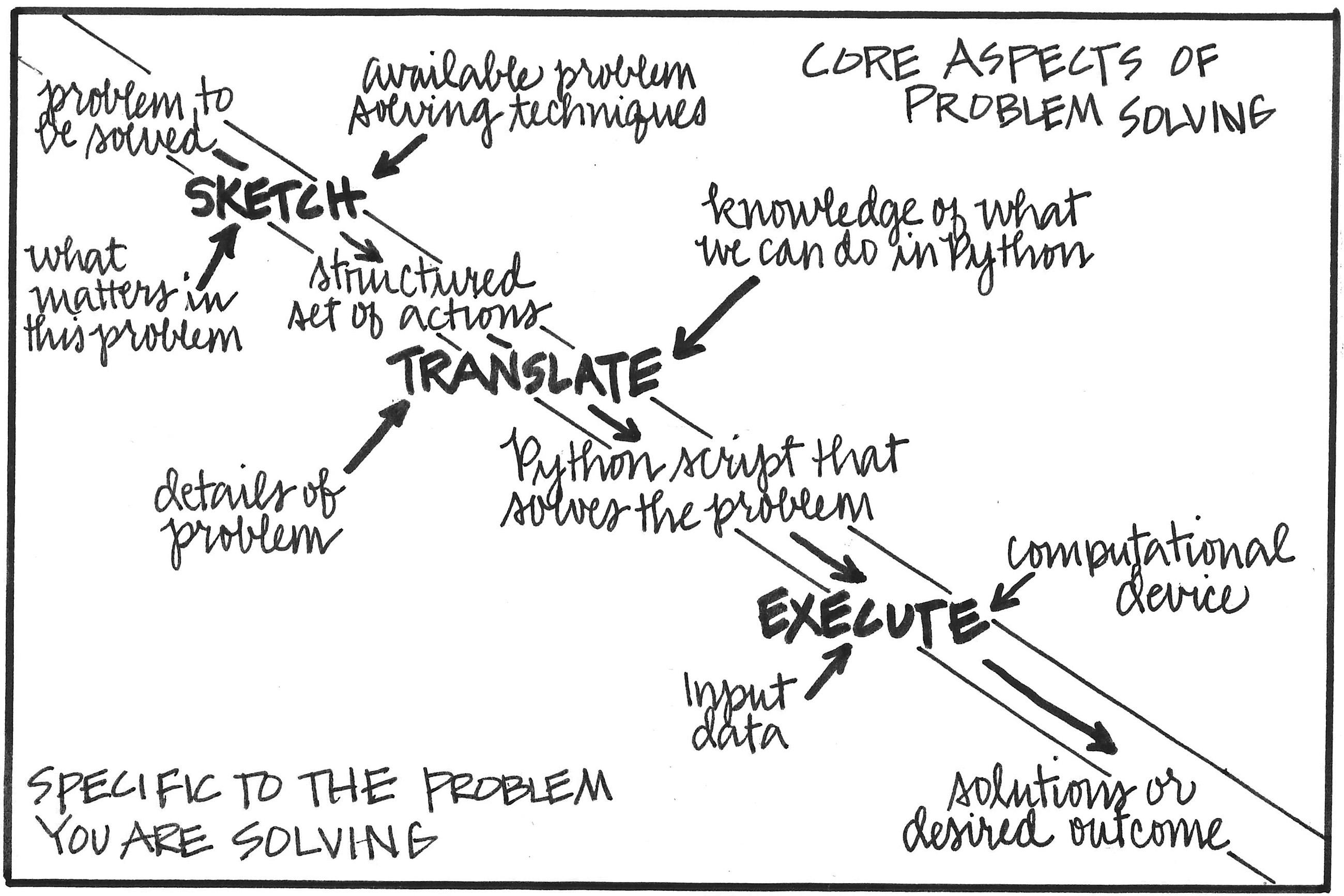

For every problem we aim to solve throughout this book, we will work through these three basic steps: sketch, translate, execute. Figure 1.1 summarizes how these steps take us from a problem to a solution, and it reminds us of what we need at each step.

Problem Solving, in Detail

While figure 1.1 makes it look like problem solving is a linear process, our first attempt, like a first draft of a story, might miss its mark. For most of us (including me), problem solving is not a linear process but an iterative one. A script when executed might not produce a correct solution or even run at all, and when this happens, we will need to figure out what went wrong and then restart our problem-solving process at some earlier step. This need to backup and restart might occur at any step in our problem-solving process. For example, we might start translating our outlined set of actions into Python and then realize that we forgot a case we need to handle. No problem. This simply means we back up and restart at an earlier step in our problem-solving process. At which step we restart depends on the implications of what we had overlooked.

Now I don’t know about you, but I don’t like to redo my work over and over again. We can avoid some of this backup-and-restart action if we are more thoughtful before we begin sketching a set of computational actions. How thoughtful? Well, we will add an additional five steps to the front of the process in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1

The work we will do going from a problem-to-be-solved to a computational solution.

Five steps before we even sketch out some computational actions might sound like a lot, but the thought put into these first five steps is what helps experienced problem-solvers more quickly find working solutions. The resulting eight-step process is still iterative. No one solves a problem perfectly in their first attempt, and these new initial steps are meant to help us discover blind spots and oversights before we have done a lot of design and coding work. In other words, this early work will save us a lot of wasted work in the last, time- consuming stages of the process.

Tip

What is the biggest trap for many beginner programmers? They attempt to go directly from a problem description to the writing of a bunch of programming language statements. Learning to program is hard enough without skipping the impor tant steps between the first and the last. As you tackle your first problems-to-be-solved, keep in mind that the actual writing of code is work done late in the process of problem solving with computation. It might look like an experienced programmer skips quickly to coding, but it is more likely that you are seeing them pull code from prior, similar problems (step 5 below). As you practice, you too will begin to see similarities between problems.

Putting this all together, the following is a brief description of each of the eight steps that will help us act like an experienced problem-solver:

1. Precisely specify the problem you will solve.

2. Imagine one or more specific instances of the problem, then identify the inputs you would use in those instances and the answers you would like produced. What you learn in this step may cause you to change the specification you wrote in step 1.

3. Decompose the problem into smaller tasks that together solve the overall problem. This decomposition may highlight corner cases that you hadn’t considered in steps 1 and 2.

4. Decide which tasks identified in step 3 are amenable to computational approaches This decision may cause you to change the problem or some aspect of the problem.

5. Identify what code you have already written or that you know exists that might help perform each task you need done. Based on what exists, you may yet again adjust the problem to minimize the work you need to do yourself.

6. Sketch the sequence of actions you want the computer to do in each task. What you discover as you do this work might change your mind about the decisions you’ve made in the previous steps.

7. Translate your sketch into programming language statements. If you run into any roadblocks in this translation, you might overcome them by changing some prior decision.

8. Execute the resulting script to see if it functions correctly and meets all the problem’s specifications. If it doesn’t, you will need to ask yourself if the failure is an error in your code or a problem with your specifications.

Don’t feel you need to memorize these eight steps or fully understand the italicized terms in them. Through repeated practice, as offered in this book’s chapters, these steps will soon become second nature. And before you know it, you won’t just be acting like an experienced problem-solver, you will be one.

Learning Outcomes

While solving each chapter’s problem, you will gain practice in design, new knowledge of computer science (CS) concepts, and specific skills in Python programming. To help you understand how you will grow in these three areas, each chapter begins with a list of its learning outcomes. By the end of this first chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the general process involved in problem solving with computation (design).

• Take the first steps in this process (design and programming skills).

• Use an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) as a place to sketch out and run a computational solution to a problem (programming skills).

• Use the interactive Python interpreter to bootstrap your knowledge of Python (programming skills).

• Understand the structure of the feedback you receive from the Python interpreter and start becoming comfortable with its error messages (programming skills).

• Consult a number of dif ferent resources that can help you interpret the meaning of this feedback (programming skills).

• Write a few commands and expressions in Python and name their results (programming skills).

• Recognize the basic form and function of Python’s if-, while-, and break-statements (programming skills).

• Explain namespaces and straightforward aliasing of Python objects (CS concepts).

• Read a text file and print its contents (programming skills).

Our First Computational Problem

I employed the imagery of how we learn to communicate ideas and stories to help you imagine how you will learn to solve problems with computation. Let’s stay close to this imagery with our first problem-to-be-solved.

When my children were young, I read to them nightly in the hope that this special time together would help them as they struggled to learn how to read. As we embark on learning to read and write Python, let’s see if we can get our computer to read a children’s book to us

Imagine a Specific Instance

We don’t yet have enough experience in computation to know whether we have precisely specified this problem, but that’s OK. Since problem solving is an iterative process, we can always come back and refine our simple specification later. Let’s move on to step 2 of the problem-solving process and consider a specific instance of our problem.

Step 2 talks about identifying our inputs; for our problem, this means choosing a book to read. One of the first books I remember having read to me when I was young was The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss. I loved this rambunctious story, and it naturally was the first book I pulled out to read to my children. Let’s have this be the first book we get the computer to read to us.

OK, but what copy of this book do we use? In the physical world, this book comes in many different shapes and sizes, and digitally, it is available in many different file formats. We need a file format that our computers can access and interpret.

We might choose a copy of our book in PDF (Portable Document Format) or DOCX (Microsoft’s file format for word processing), as these formats allow us to include text and pictures. Or we might choose a file format that stores only the book’s text. In making this choice, notice that we are already refining our problem specification!

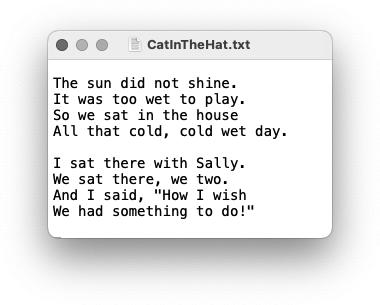

Let’s decide that our script will expect the book to be a plain text file format (.txt), since I have such a plain text file containing the beginning of The Cat in the Hat available for you to use as an input. Figure 1.2 shows what we would see if we opened this plain text file in a typical word processor (e.g., Microsoft Word or Google Docs).

In addition to our script’s input, we also must specify its output. Let’s agree that the output on our computer screen is the text that we see in figure 1.2.

Tip

These two choices illustrate an approach that I strongly advocate: Start with a single and simple instance of your problem-to-be-solved. Here, we have decided to start with a script that won’t read any book in any format but this one specific book in one par tic ular format. Then write a script that solves that instance. Only then should you consider how you might expand your script’s functionality so that it solves multiple dif ferent instances of your problem (i.e., other books and other formats).

In summary, the script we will write will take the contents of the file named CatInTheHat.txt as input and display its contents on our computer screen as if it were reading the book from start to finish. As a finishing touch, let’s have the script add an extra line to the end of the book where it will say, as I always did for my children, “The End.”

Sketch Using Computational Thinking

Given that this is our first computational problem, we will skip over steps 3 through 5 of our problem-solving process. These three steps become impor tant as you gain experience.

Figure 1.2 The contents at the start of the file named CatInTheHat.txt

For example, in subsequent chapters, you will start to see problems that you have already solved as pieces of the problem you are currently trying to solve. But since we can’t yet plumb such experience, we will jump directly to step 6 and sketch out the sequence of actions that will get the computer to read our book to us.

Remember that our goal in this step is a sketch. Although our script must eventually be written in a programming language, step 6 is not about programming but computational thinking. This step is not programming because we are not trying to say something in a programming language like Python. This means that you don’t need to know Python or any other programming language to create a sketch. You can use any language you would like to capture the sequence of actions in your sketch.

So, what is computational thinking if it is not programming? The historical note at the end of this chapter presents what some noteworthy people have said about this term, but for our purposes, I mean the thought process humans move through to structure a problem and its solution script so that the problem is solvable by a computational device.

This definition begins by emphasizing one of Jeannette Wing’s impor tant characteristics about computational thinking: It is “a way humans solve problems,” and it is not about “trying to get humans to think like computers.”1 It is a way because the definition constrains our creative problem-solving ability: the problem specification must be amenable to a computational solution, and the solution script that we eventually produce must be

1. Jeannette M. Wing, “Computational Thinking,” Communications of the ACM 49, no. 3 (March 2006): 33–35. https://doi org /10 1145/1118178.1118215

able to be run on a computer. This constraint is something that Alfred Aho emphasizes in his definition of computational thinking: computers and computation are the primary tools we use in producing a solution to our problem.2 Beyond this constraint, we can use any of the diverse skills we often employ in everyday problem solving, from simple mathematical analyses to complex planning to the understanding of human behavior. You can see this if you read through Jeannette Wing’s seminal paper on computational thinking and think about what is involved in each of her many examples.

Capturing This Thinking

Creating a sketch of a script using computational thinking is what we want to do, but you are probably still thinking, “This isn’t clear. What exactly am I supposed to do?”

To help, let’s return to the imagery of children learning. With time and practice, children are able to quickly turn ideas into coherent, grammatically correct statements. But are perfect clarity and correct grammar the most impor tant issues when first learning to talk? Do you see parents interrupting their young child every time the child is unclear or makes a grammatical mistake? I don’t. Instead, I see parents encouraging their children to put words to their ideas. The resulting broken English (or whatever your native tongue) isn’t always coherent or grammatically correct, but it is often sufficient to communicate the child’s thoughts.

When starting out, we have the same goal: capture in a sketch (i.e., broken English) our ideas about how we might computationally solve the problem

Broken English for us is what computer scientists call pseudocode. In pseudocode, it is fair game to write down the set of actions you’d like the computer to take in any English phrase that makes sense to you. If you want the computer to open a window on the screen, you can type the phrase: open a window on the screen. If you want the computer to add 5 and 6, you can type: add 5 + 6. I don’t care what you write as long as you— and hopefully others— have a strong sense of what you mean.

An Environment for Coding

So let’s write down some pseudocode— that is, some ideas about how to instruct a computer to read a book to us. But where should we write these ideas, this pseudocode? We could scribble on a piece of paper, but it would be better if we wrote this pseudocode where it would be easy for us to turn our ideas into actual Python code, which is the next step in our problem-solving process.

Fortunately, there are numerous applications available for writing, running, and inspecting code. These tools are typically called an editor, an interpreter, and a debugger The editor is where we will write our pseudocode and then our Python script. The interpreter is what allows us to run the script we have written, and the debugger is a tool that can help us understand the reasons why our script may not have run as we had hoped.

2. Alfred V. Aho, “Ubiquity Symposium: Computation and Computational Thinking,” Ubiquity 2011 (January 2011): article 1. https://doi org /10 1145/1922681.1922682

Figure 1.3

The bars, panels, and button we need to get started, as illustrated in our generic IDE.

While you can use these as standalone tools, many programmers like to use what is called an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) that packages together all the tools you’ll need in a single application. In a moment, I’ll help you get started with an actual IDE that you’ll use to build the computational solutions I discuss in this book’s chapters. There are many dif ferent IDEs, including some that are free, and it won’t matter which you use. The most impor tant thing is that you use an IDE as you work your way through this book.

Our

Generic IDE

Most IDEs have many features, and it is easy to feel overwhelmed with their extensive functionality. Don’t worry. You’ll need only a small slice of it in this book.3 In par ticular, I want you to become familiar with six things found in every IDE, which are typically instantiated as two bars, three panels, and one button. Figure 1.3 illustrates where I locate these six items in what this book calls a generic IDE

Running along the top of our generic IDE is the title bar, which is where you will find the name of the project you have open. You can think of a project as a folder on your computer. It is where you store all the scripts, other files, and specific configuration information associated with the problem you are trying to solve. You can name your projects anything you like.

3. The IDEs that I’ll suggest to you are ones used by professional programmers. This way you can continue with your selected tool long after you finish this book.

The other major bar is the menu bar, which often resembles a tray of icons. By selecting one of these icons, you can inspect dif ferent aspects of your project. To begin, the menu bar in our generic IDE will contain only two icons, as illustrated in figure 1.3. The first looks like a small stack of papers, and clicking this icon changes the panel to the right of the menu bar into a file explorer. It allows you to manipulate the files in your project. The second looks like a small gear, and clicking it displays configuration options for the IDE.

Tip

There are two IDE configuration settings to apply if you want to work with the code in this book: (1) the editor should perform indentation using spaces, not tabs, and (2) a single level of indentation is four spaces. As we will discuss shortly, indentation holds meaning in the Python programming language. By adopting the same indentation settings as I did in creating this book’s scripts, you will be able to seamlessly use my code. If you don’t adopt these settings, you will generate many unnecessary headaches for yourself.

Besides the panel to the immediate right of the menu bar, our generic IDE also contains two other panels: the code editor and the console.

The code editor acts like a panel in a word processor. When we click our mouse inside this panel, we get a cursor at the location of our click and can start typing. And just like in a word processor, we can use the functionality of the editor to edit, search, and format the text we type.

Tip

You might be wondering if you could use your current word processor to write your Python scripts. Although you can— a Python script is nothing more than a specially structured text file— the features we want in our code editor are not the same ones useful in writing an email to grandma, a theatrical script, or a technical paper. For example, we won’t need to insert images into our Python scripts, but we will want to include code modules written by others. We won’t care if a word in our script is a valid English word, but we will want help knowing what the word means in the context of this script. Fi nally, we will want a dif ferent type of autocomplete (e.g., one that helps us remember the particulars of the syntax in our programming language). Hopefully, you’re starting to see the benefit of adopting an editor that is purpose-built for programming. A good code editor will make the process of coding easier. Don’t use a word processor to write or edit your code.

The last panel, which in our generic IDE is the one to the far right, is the console. It is where we can interact with our script as it runs. You can think of this panel as the stage where the actor (the Python interpreter on our computer) performs our script. How do we ask the interpreter to run the script that appears in the editor pane? That’s right! We click the Run button

You Try It

It’s time to select the IDE that you’ll use as you work through this book’s problems-to-be-solved. On the companion website to this book, you can find directions that will help you get started with one of several dif ferent IDEs. Some of them are free to use. It doesn’t matter which you choose. Only once you’re set up with an IDE should you read on.

Our First Pseudocode

We are now ready to do some computational thinking and sketch out our thoughts in an IDE. If we want our computer to read The Cat in the Hat to us, what is the first action it should take? Think about the first action that you would take if you were to read this book to another person. Now write that down in the editor window in a file called seuss.py

You probably wrote something like the following, where the initial 1 is just the line number displayed by the IDE’s editor:

1 # Open the book so we can read it

If you wrote something like “Read the first line” then you have to get used to thinking about every step in the process of doing something. Unlike a human, the Python interpreter won’t know that to read the first line, you must first open the book. This is important: When writing a computer script, you must tell it every detail of what you want it to do. We will see in a moment what happens when we don’t provide the interpreter with specific instructions.

What we just wrote is pseudocode. It is a description of what we want the interpreter to do. This description isn’t Python code, and we want to make sure that the interpreter doesn’t try to interpret it as such.

Comments

I made sure that the interpreter would ignore my line of pseudocode by placing a hash mark (#) at the start of the line. This character holds special meaning in Python. When the interpreter sees it, it knows to ignore every thing from the hash mark to the end of the line. Programmers refer to text like this as comments

Comments are notes that we write to ourselves, or we might use them to leave a note for anyone else reading our script. Let me emphasize that comments are for humans. The interpreter will ignore whatever is in a comment, and so a comment cannot contain any actions that we want the computer to interpret or act out.

Even though comments don’t tell the computer anything, they are impor tant and useful. I will use them for two distinct purposes:

• To capture our ideas during the problem-solving phase when we sketch the actions the computer should take (step 6)

• To explain why the Python code that we write in step 7 looks like it does. According to Swaroop in A Byte of Python, “Code tells you how, comments should tell you why”4

Commands and Input Parameters

Normally, we would write more pseudocode to sketch out what we want the interpreter to do, but let’s convert this pseudocode into Python code so that we can get a feel for what it is like to command the computer to do things.

4. C. H. Swaroop, A Byte of Python, Python version 3, accessed March 19, 2025. https://python swaroopch com / basics.html

Our pseudocode instructs the interpreter to open our book, just as if we had a physical copy of The Cat in the Hat. So let’s write open('CatInTheHat.txt') on the line below our pseudocode. This new line is valid Python. What does it command the interpreter to do? To open the file named CatInTheHat.txt

1 # Open the book so we can read it

2 open('CatInTheHat.txt')

Let’s talk about the syntax (i.e., the form and ordering of the elements) in this line that makes it valid Python. Its form is command (input parameters). In our example, we are issuing an open command, which requires a piece of information to do its work (i.e., a single input parameter). In this case, the parameter tells the interpreter what file we want opened. The single straight quotes around the filename are necessary, and I’ll explain why in a bit.

In general, a command may require zero, one, or many input parameters. When there are multiple input parameters, each is separated by a comma. A command that takes no parameters has this form: command (). In other words, you always need the parentheses.

Returning to our open command, how is it that the Python interpreter knows what to do when it encounters an open command? There are three answers to this question:

• The command is built into the Python language

• It was added to the language by some other person

• We added it to the language ourselves

In the case of open, it is a builtin function. We will stick with commands built into the Python language in solving this chapter’s problem; we’ll see the other two categories of commands in the following chapters.

Terminology

Think of the term command and function as interchangeable terms. Every command is performed by some code that we think of as a function. We’ll learn to build functions in chapter 3.

Scripts Versus Execution

So far, we have a script with a comment and a single command. Imagine you are a playwright writing a short note to yourself and a single line for an actor. Once written, the next step is for the actor to perform the line so that you can see how it works. In your IDE, the equivalent of this handoff from playwright to actor is to click the IDE’s Run button. It instructs the Python interpreter to run your script.

Go ahead and try it with the script we’ve written so far, which is copied below:

1 # Open the book so we can read it

2 open('CatInTheHat.txt')

You Try It

As you read on, you’ll notice that I do not include the result of running this script in the text. This is to encourage you to be an active learner. Write the two lines above in your own IDE, and then hit the Run button and see what happens. Feel free to experiment by changing the code and hitting the Run button again. You can’t break anything, so experiment. Be creative!

Oops, our code produced a whole lot of text in the console panel that’s telling us we did something wrong.

Our First Error

Computer scientists call this text an error message. I don’t want you to think of this as an error but as feedback . The Python interpreter is trying to tell us that it couldn’t perform a part of our script. Unfortunately, the interpreter’s feedback isn’t always easy to understand. If it helps, think about the interpreter as an actor whose English isn’t too great.

What can we learn from the broken English in this error message? FileNotFoundError looks like promising information, and the file the interpreter couldn’t find was CatInTheHat.txt. Do you see this in the error message? The message also says that the interpreter had this trouble when it tried to execute the open command on line 2 of our script.

The interpreter can’t find the input file because this file isn’t one of those listed in the file explorer panel. How can we change this? We could add a new empty file to our project called CatInTheHat.txt, but then we’d have to type its contents, and I’d rather not type in something that already exists. So where can you find this existing file? It’s in the txts folder in your IDE’s file explorer.

You Try It

Use your IDE’s file explorer to make a copy of CatInTheHat.txt so that this copy is at the same level of the file explorer as your seuss.py script. Your IDE probably supports the same kind of copy, paste, move, and rename actions that you’ve used with your computer’s operating system.

With CatInTheHat.txt where the script seuss.py expects it, click the Run button again. Success! I mean, at least no error message this time.

But it looks as if clicking the Run button did nothing. The interpreter was completely silent while executing our script. Is that what you expected to happen? If we’re going to command the interpreter to do things for us, we had better develop an understanding of how it operates. Only with a good mental model of its operation can we successfully command it.

The Interactive Interpreter

Giving the Python interpreter a script (like seuss.py that we’ve started writing) is one way to command it, but it isn’t the only way. We can also ask the interpreter to interact

with us. You should think about this as having a conversation with the interpreter. In this conversation, we can feed it different parts of our Python script and see how it reacts, and like an attentive friend, the interpreter will remember what we’ve previously said to it. In the directions that got you started with your selected IDE, I include a section that tells you which panel in your IDE you should use to start the Python interpreter in its interactive mode— that is, what people call the interactive Python interpreter. This IDE panel contains a shell prompt where you type can python3, then press the return key on a Mac or the enter key on a PC.

Terminology

You’ll learn a lot more about the shell in chapter 13, but briefly, the shell is a mechanism for you to run programs on your computer and manipulate your computer’s files and folders.

To illustrate, in the block below, shell_prompt$ is the shell prompt (your IDE’s shell prompt will look different). The next lines are information about the version of the Python interpreter that you’re running and a few commands you can send to it; the interpreter prints these lines as it starts running (your lines will look slightly different). The final line, starting with >>>, is the interactive Python interpreter’s prompt (yours will look exactly like this).

shell_prompt$ python3

Python 3.12.3 (main, Apr 9 2024, 08:09:14) [GCC 13.2.0] on linux Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

To exit the interactive Python interpreter, you simultaneously press your keyboard’s control key and the letter-D key.5 Going forward, I’ll abbreviate this key combination as Ctrl + D

You Try It

Use Ctrl+D to exit the interactive Python interpreter and then type python3 at the shell prompt to re- enter the interactive interpreter.

Code and Transcript Blocks

I want to pause here and make sure that you recognize the difference between a code block (e.g., the earlier block that contained a comment and an open command) and a transcript block (e.g., the previous block that illustrates how you can launch the interactive Python interpreter). Code blocks are the scripts that we’ll feed to the Python interpreter, while transcript blocks are recordings of the conversations I had with the Python interpreter or my computer’s operating system.

5. If you’re a MacOS user, I do mean the control and not command key.

The previous block is a recording of my interaction with the shell on my machine, and it ends with a prompt that allows us to converse with the interactive Python interpreter. You use Ctrl+D to end this conversation and return to talking to the shell.

Interacting with the Interpreter

OK, let’s chat with the interactive Python interpreter and see how it reacts to the two lines in our suess.py script. In other words, let’s feed the two lines of our script to the interactive Python interpreter one at a time.

Starting with the comment line, type it at the interactive interpreter’s prompt and hit enter. What happened?

>>> # Open the book so we can read it

>>>

The transcript shows that nothing happened! Exactly what the interpreter should do with a comment line.

Now type the open line at the interactive Python interpreter’s prompt.

>>> open('CatInTheHat.txt')

<_io.TextIOWrapper name='CatInTheHat.txt' mode='r' encoding='UTF-8'>

>>>

The interpreter responded with something interest ing. It doesn’t read like the error message we saw earlier. The interpreter is trying to tell us something different. In technical jargon, the Python interpreter, in interactive mode, prints the value it computed. To understand what this means, let’s try something simpler.

The Interpreter as a Calculator

What happens if you type 2 + 3 at the interactive Python interpreter’s prompt?6 Before you hit enter, take a moment and think about what we are asking the interpreter to do.

>>> 2 + 3

Press the enter key. Yes, we can use the interpreter like a calculator to evaluate an arithmetic expression. Given an expression, the interpreter prints what it calculates.

You Try It

Take a bit of time and play with the interpreter as a calculator. Keep in mind as you play that you are playing to learn. If you try something and it fails, try something slightly dif ferent. As you read this book, get into the habit of experimenting and forming theories from what you observe during these experiments. By the way, a simple Google search with the phrase “Python arithmetic operators” will connect the mathematical operations you know with the symbols that perform these operations in the Python programming language.

6. Note that I haven’t provided a full transcript. Type 2 + 3 at your interactive Python interpreter’s prompt. Don’t just read. Try!

From your experiments, I hope you have learned that the interactive Python interpreter prints the value of the expression we asked it to evaluate. So, what is this value that it printed when we asked it to open a file?

Python Help

Wouldn’t it be nice to ask for some help? It would, and so let’s do that. Type help(open) in the interactive interpreter and run it.

The help command is another Python built-in function, and it tells us about what we provided as a parameter to this function. The help command says that open takes a filename and a whole bunch of other input parameters. These other parameters, however, are optional parameters, which are given default values if you do not specify them. That’s what the = syntax means.

For now, let’s look only at mode and encoding mode defaults to 'r', which means that we are going to read the file. Alternatively, we might want to write the file. We will talk about encoding in greater detail later; for now, you can think of it as telling the interpreter which language the file is written in (i.e., the computer equivalent of asking if it is written in English or French).

Fi nally, help tells us that this built-in function opens a file and returns a stream Again, we will talk about file input and file output (i.e., file I/O) in greater detail later in the book, but think about it. When I open a book, I probably open the cover and put my finger on the first word on the first page. You can think of a stream as my virtual finger telling me where I’ll read the next characters in the file.

Returning to the question about the value the interpreter printed, it was cryptically telling us about the position of its virtual finger in the file. Less cryptically, this value is the description of an object that reads a text file whose name is CatInTheHat.txt and whose content is encoded in the UTF-8 language.

Terminology

I’ll talk more about objects later in this chapter. For now, think of a Python object as the physical representation of an idea. Python records something when it computes the answer to the expression 2 + 3. Similarly, it records some information when it opens CatInTheHat.txt and puts its virtual finger at the first character in that file.

Revisiting Our First Error

What happens if we ask the interactive Python interpreter to open a file that doesn’t exist? We saw that this caused an error when we executed our whole script and the text file we wanted wasn’t in the list of files. Will this error message look dif fer ent when the problem occurs in the interactive interpreter? I don’t know. OK, I do, but let’s pretend I don’t.

Let’s misspell the filename and execute that open statement. Type the following in the interactive interpreter: open('CatInTheHut.txt')

We got an error message again, as expected. This time it shouldn’t look as scary because we’re already familiar with it. Yup, FileNotFoundError, as we saw before. This is a type of OSError that help told us would be raised upon failure to successfully complete the open operation.

The only difference this time is that the Traceback looks a bit dif ferent. It doesn’t tell us where in our script the execution error occurred, but that there was a failure on line 1 of this cryptic file “<stdin>”. We don’t really need to understand this broken English, since this traceback information is only needed when we have an error buried somewhere in a multiline script.

Undefined Names

Let’s return to our script seuss.py. We now know that the interpreter does nothing with our comment line and then computes a stream object (i.e., a virtual open book) from our open command. At the end of seuss.py, the interpreter is ready for us to tell it what we want it to do with this stream object, this open book.

Well, how about we read the first line? If Python has a built-in file open command, maybe it has another built-in function called readline. Let’s type readline() at the bottom of our script and run it. The empty parentheses at the end of readline simply say that we’re not providing this command with any input parameters.

1 # Open the book so we can read it

2 open('CatInTheHat.txt')

3 readline()

Oops, another error that says NameError: name 'readline' is not defined This seems to be telling us that Python doesn’t know what to do when we tell it to execute a command called readline

Let’s look at the online Python documentation and, in par ticular, at the list of built-in functions.7 The command open is there, but not readline. In fact, there are no read functions at all. There must be something wrong with our thinking. What good is it to open a file if you cannot read it?

Talking Through Your Confusion

Let’s try these commands on a person to see if we can glean what might have gone wrong. Yes, you should try the following with a friend or family member. Give your friend a book and then command them to open('book_name'), where book_name is a book that they’re holding. Next, command them to readline(). Did they do what was commanded? While they probably opened the book in their hands, it’s hit or miss if they read a line from it. The command readline() doesn’t specify what line you want read. What if our script had opened two files or your friend had two open books? How would either know which to read?

7. Python Software Foundation, “Built-in Functions,” accessed March 19, 2025. https://docs.python.org /3 / library/functions html#built-in-funcs

This is an example of what’s good and bad about computers. They are very literal. They will do exactly what you ask them to do and nothing more.

If you’re lucky, when you tell a computer to do something ambiguous, it won’t do anything and will instead tell you that it is confused by your command. That’s what the Python interpreter did when I asked it to execute a command name that it didn’t know.

If you’re unlucky, it will do something random, and you’ll need to determine for yourself if the computer did what you wanted it to do. We will spend a good bit of time talking about how to avoid these situations and what to do when you find yourself in them.

Naming a Computation’s Result

We can solve this problem of ours by using the result of the open command. In par ticular, we want to tell the interpreter to use that thing it computed during open and read the first line in that file’s stream (i.e., the line under its virtual finger). This context removes any ambiguity about what line to read.

Let’s delete readline() and type a new piece of pseudocode:

1 # Open the book so we can read it

2 open('CatInTheHat.txt')

3 # Read the first line using that thing you computed

This pseudocode highlights a naming problem. How do we tell the interpreter what “ thing” I mean? Luckily, Python and all other programming languages allow us to name the results of a computation.

Edit the open statement as follows, assigning the result of the open command to the name my_open_book:

1 # Open the book so we can read it

2 my_open_book = open('CatInTheHat.txt')

3 # Read the first line using that thing you computed

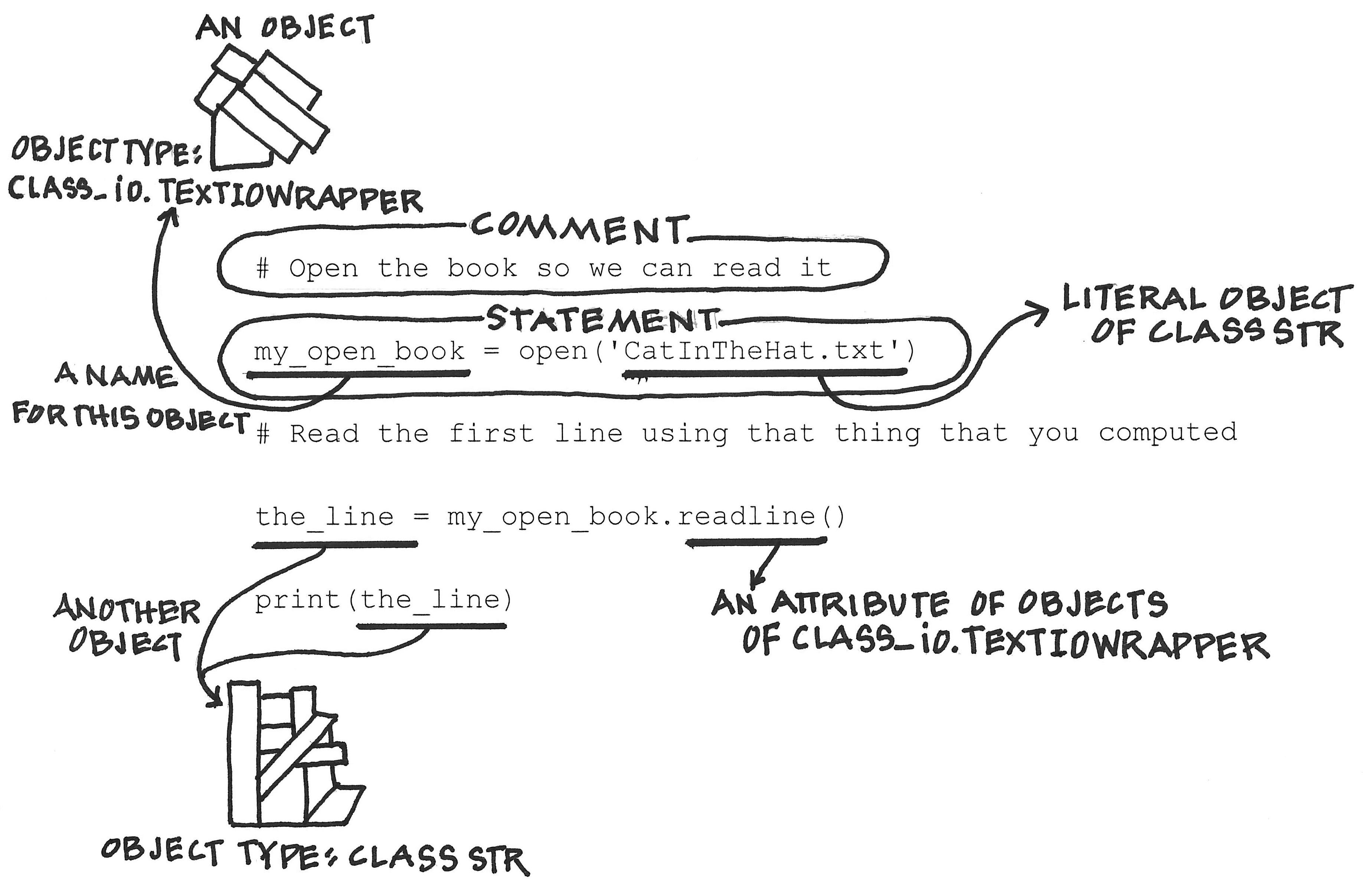

A single equal sign (=) is the assignment operator in Python. We’ll talk more about naming and the intricacies of assignment, but for the moment, you can think of this single equal sign as saying, “Whatever open produced as a result, name it my_ open_book.”

With a name for our open book, we can now read specifically from it. Append my_ open_book.readline() to the end of your script, which is proper Python syntax for reading the next line from the open file. I’ll explain the syntax of this statement in a bit (i.e., don’t fret over the use of the period or dot between my_open_book and readline).

1 # Open the book so we can read it

2 my_open_book = open('CatInTheHat.txt')

3 # Read the first line using that thing you computed

4 my_open_book.readline()

Click the Run button. No errors! There is also no read line in our console.

Debugging

It’s one thing to have the interpreter report to you that something didn’t work, but it can be even more frustrating when a script runs to completion and the result isn’t what you expect. How do you figure out where and what went wrong?

We will learn that there’s no single, simple answer to this impor tant question. The good news is that there are many effective strategies that you can employ to determine what went wrong. Because our current script is so small, we’ll start with the most straightforward method, which you can think of as a brute-force approach. We start at the beginning of the script and feed each line that isn’t a comment to the interactive interpreter. The following is a transcript of what happened when I fed the highlighted lines, one at a time, to the interactive interpreter:

>>> my_open_book = open('CatInTheHat.txt')

>>> my_open_book

<_io.TextIOWrapper name='CatInTheHat.txt' mode='r' encoding='UTF-8'>

>>> my_open_book.readline()

'The sun did not shine.\n'

Notice that I typed the name of the result we computed in our open command (i.e., my_open_book ) at the second prompt, and the interpreter printed the value of that name (i.e., a TextIOWrapper object). This matches what open computed before, as we saw earlier. This also makes clear what it means for the interactive interpreter to remember named results (i.e., keep the state of our running computation). We can look at (and even modify the values of) the names we know at any point in the execution of a script.

Continuing with the transcript above, I then typed the last line of our seuss.py script and hit enter. In response, the interpreter printed the book’s first line. Our script does successfully read the first line of our book, but why didn’t the book’s first line appear when we ran seuss.py?

Showtime