The Weight They Carry

Life as a Teacher in Mississippi

Acknowledgements

Mississippi First extends special thanks to the 988 teachers who completed the 2025 Mississippi Teacher Survey, as well as the colleagues who provided valuable feedback on early drafts of this report. Mississippi First worked with the Survey Research Laboratory (SRL) at Mississippi State University’s Social Science Research Center to obtain survey data for this report. Mississippi First completed all analysis, and SRL does not necessarily agree or disagree with any of the analysis or commentary. This report was made possible by the generous support of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of Mississippi First alone.

Team

Grace Breazeale, Author Director of Research and K-12 Policy

Angela Bass, Editor Executive Director

Micayla Tatum, Editor Director of Early Childhood Policy

Madaline Edison, Editor Consultant

Heather Bruce, Designer

Copyright © 2025 by Mississippi First. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. Icons found in this design are from Faticon.com.

Table of Contents

Part One | Compensation

Insight: The value of a teacher’s salary has declined over the past decade and continues to erode in the absence of regular pay raises.

Insight: A significant proportion of survey respondents are not financially secure, evidenced by their lack of ability to afford basic necessities, pursuit of second jobs, and self-reported financial status.

Part Two | Workload and Workplace Support

Insight: Mississippi teachers face unsustainable workloads, reflecting a national trend.

Insight: Educators’heavyworkloadsunderminetheirwell-being.

Insight: Workload pressures are more acute for teachers in high-poverty schools.

Part Three | Student Behavior

Insight: Student behavior plays a critical role in shaping teachers’daily experiences and can significantly contribute to burnout.

Insight: Schools continue to grapple with the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on student behavior.

Insight: Student behavior challenges tend to be more prevalent in high-poverty schools.

Part Four | School and District Leadership

Insight: School and district leaders play a significant role in teacher satisfaction and retention.

Insight: High-poverty schools tend to have more turnover among school leaders.

Part Five | Who is Most At Risk of Leaving?

Insight: Teachers in the early stages of their careers are more likely than their peers to consider leaving their current role.

Insight: Teachers earning less than $3,000 in local salary supplements are more likely to consider leaving their school district to teach in another one.

Insight: Teachers in high-poverty districts are more likely than their counterparts in other districts to consider every form of exit from their current classroom: teaching in another state, moving to another Mississippi school district to teach, taking another role in education, or exiting education entirely.

Policy Recommendations

Goal 1: Increase teacher compensation to make the profession financially sustainable.

Goal 2: Make teacher workloads more manageable by providing adequate time, staffing, and resources.

Goal 3: Strengthen student behavior supports so teachers feel equipped and empowered to manage classrooms effectively.

Goal 4: Build and retain strong, stable leadership in every school.

FOREWORD

OBy Angela Bass, Executive Director

ver the past decade, Mississippi students have made some of the greatest academic gains in the nation.

But there is another story unfolding alongside this progress, one that is far less visible in headlines and rankings. It is the story of what it costs to be a teacher in Mississippi today.

As we captured the voices of educators across the state, a common theme emerged: the burden they shoulder has grown heavier over time. Even though student achievement has improved, too many teachers are struggling to pay their bills, keep up with mounting responsibilities, manage increasingly complex student needs, and navigate systems that do not always listen to or support them. At the same time, schools, especially those with the highest-need student populations, are losing teachers faster than they can replace them.

This report, The Weight They Carry, is Mississippi First’s effort to name and understand that reality. Building on our previous teacher pipeline work, we surveyed almost 1,000 teachers across the majority of the state’s public school districts and charter schools. Their responses are candid and often painful to think about. They report paychecks that do not cover basic needs, workloads that exceed the hours in a day, classrooms shaped by post-pandemic trauma and behavioral challenges, and leadership that can either lighten or magnify the burden.

Taken together, their voices make one thing clear: Mississippi does not have a generic “teacher shortage.” We have a teacher retention crisis that is concentrated in specific places and driven by specific, solvable problems. Teachers are not leaving because they care less about their students or believe less in their work. They are leaving, and thinking about leaving, because the conditions we have created for them are increasingly unsustainable.

The Weight They Carry does not stop at describing the problem. It offers concrete, targeted policy recommendations for the state legislature, the Mississippi Department of Education, and local school districts. Some of these recommendations require new investments. Others ask us to use existing resources and authority differently. All are grounded in a simple idea: if we want our state to sustain its gains in student achievement, we must make it possible for teachers to build long, stable, and dignified careers in our classrooms.

“Teachers are not leaving because they care less about their students or believe less in their work. They are leaving, and thinking about leaving, because the conditions we have created for them are increasingly unsustainable.”

This foreword is both a note of gratitude and a call to action. We are deeply grateful to the educators who took time, often at the end of long school days, to complete this survey and share their stories. Their honesty is a gift to this state. We also recognize the many leaders, advocates, and community members who have worked for years to improve public education in Mississippi. The progress our state has made shows what is possible when we treat student outcomes as a shared responsibility.

Now we must widen that lens. The next era of Mississippi’s education story cannot be only about student achievement. It must also be about the conditions we create for the people who make that achievement possible. The question before us is not whether we value teachers in theory, but whether we are willing to act in ways that reflect that value in practice, through pay, support, and leadership that honor the complexity and importance of their work.

Our hope is that The Weight They Carry will be used as a practical tool: by legislators weighing budget choices, by state and district leaders designing policy and supports, by school boards setting priorities, and by community members seeking to understand what their local schools are facing. The choices we make in the coming years will determine whether Mississippi’s recent progress becomes a foundation for long-term excellence or a brief moment that is not sustained.

Mississippi has already proven that meaningful improvement is possible in public education. We have done something hard once. We can do it again, this time by ensuring that every teacher who wants to stay and serve Mississippi’s children has an opportunity to thrive.

Executive Summary

Mississippi stands at a crossroads. In recent years, the state has been a national success story in public education, with students making extraordinary gains in reading and math. These achievements are not the result of chance but reflect years of intentional reform, strategic investment, and, most importantly, the dedication of Mississippi’s educators.1

Yet beneath this progress lies a persistent crisis: Mississippi struggles to retain the educators who made these gains possible. Following the 2023-2024 school year, 19.4% of teachers left their positions, the second-highest rate in the past eight years. Midway through the 2024-2025 school year, the Mississippi Department of Education reported 2,964 teacher vacancies across the state.2

In the wake of vacancies, teachers who remain in the profession are often expected to absorb the additional responsibilities that arise from the unfilled positions, contributing to a cycle of burnout and more attrition. Ultimately, students are the ones who bear the consequences of this cycle, as teacher turnover disrupts schools and negatively impacts student achievement.3,4

The Weight They Carry investigates the causes behind Mississippi’s high rate of teacher turnover, building on insights from Mississippi First’s prior teacher pipeline reports published in 2022 and 2023. Drawing on survey responses collected during the 2024-2025 school year from 988 public school teachers across 121 school districts and charter schools, this report identifies four central pressures pushing educators out of the classroom: inadequate compensation, unsustainable workload, challenging student behavior, and disconnect with school leadership. We examine each of these factors in depth and conclude with a set of targeted policy recommendations for the Mississippi Legislature, Mississippi Department of Education, and local school districts.

1 Dan Goldhaber, “In School, Teacher Quality Matters Most,” Education Next 16, no. 2 (2016): 56-62, https://www.educationnext.org/in-schools-teacher-quality-matters-most-coleman/

2 “Mississippi Educator Workforce Shortages and Strategies,” Mississippi Department of Education, December 19, 2024, https://mdek12.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2024/12/24-25_Educator-Shortage-Survey-Results-and-Strategies.pdf

3 Desiree Carver-Thomas and Linda Darling-Hammond, “The Trouble With Teacher Turnover: How Teacher Attrition Affects Students and Schools,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 27 (2019): 36, https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.3699

4 Matthew Ronfeldt, Susanna Loeb, and James Wyckoff, “How Teacher Turnover Harms Student Achievement,” American Educational Research Journal 50, no. 1 (2013): 4-36, https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/ how-teacher-turnover-harms-student-achievement

Table 1. Summary of Policy Recommendations

goal one

Increase teacher compensation to make the profession financially sustainable.

Provide an across-the-board increase to Mississippi’s teacher salary schedule

Pilot a school staffing redesign program

Boost local salary supplements and commit to regular increases

Adopt paid parental leave policies

Provide retention incentives

Proactively explore school staffing redesign models

Suppor t school districts in transitioning to school staffing redesign models

Include local salar y supplement data in annual teacher salary report

goal two

Make teacher workloads more manageable by providing adequate time, staffing, and resources.

Guarantee time for duty-free lunch

Increase pay for assistant teachers

Audit and eliminate unnecessary duties

Adopt aligned high- quality instructional materials (HQIM) and ensure teachers are trained to use HQIM

goal three

Strengthen student behavior supports so teachers feel equipped and empowered to manage classrooms effectively.

Implement clear and consistent behavior policies

Promote access to high-quality professional development on behavior management

goal four

Build and retain strong, stable leadership in every school.

Implement 360-degree feedback systems for principals and use to drive professional development

Prioritize high-quality professional development for principals

Sur vey principals to identify needs and barriers

Establish a statewide task force on school leadership development and retention

Technical Information

Survey Methodology

Mississippi First partnered with the Survey Research Lab (SRL) at Mississippi State University to conduct our 2025 Mississippi Teacher Survey. Mississippi First developed the survey instrument and provided SRL with a contact list containing email addresses for public school teachers across the state. To build the contact list, we sourced publicly available information from the Mississippi Department of Education and school district websites. The final list included 31,103 valid email addresses.

The SRL programmed the survey and generated a secure response link, which was distributed via email to the contact list we provided. Over the course of two weeks, SRL sent three invitations encouraging teachers to participate in the survey. Once the survey closed, SRL returned a dataset of deidentified responses to Mississippi First for analysis.

All data analysis in this report was conducted independently by Mississippi First. The SRL is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, any conclusions or commentary contained in this publication.

Survey Items

Survey items included questions about respondents’financial well-being, career plans, policy preferences, demographic information, and more. The full survey can be found in Appendix B.

Free Response Items

The survey included an open-ended question allowing teachers to provide additional context about factors influencing their career decisions. Selected responses are featured throughout the report. Some quotes have been lightly edited for grammar, clarity, or length, without altering meaning

A Note on Interpreting Results

This report reflects data from the 988 teachers who completed the 2025 Mississippi Teacher Survey (approximately 3.2% of the state’s public school teachers during the 2024-2025 school year). While the survey sample closely matches the statewide teacher population on key observable characteristics such as gender and race, it is important to note that survey participation was voluntary. As a result, findings may be subject to self-selection bias and should be interpreted with this limitation in mind.

Demographics of Respondents

Note: Percentages in each table may not total 100 percent due to rounding.

Table 2. Gender of Respondents

Source: Data on the public school teacher population was obtained from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Table 3. Race of Respondents

Source: Data on the public school teacher population was obtained from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Table 4. Teaching Experience of Respondents

Source: Data on the public school teacher population was obtained from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Introduction

Over the past decade, Mississippi’s students have made remarkable academic gains. Between 2013 and 2024, the state’s fourth-grade reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) rose from 49th to 9th in the nation, while fourth-grade math scores climbed from 50th to 16th.5 After adjusting for demographics, Mississippi students currently rank highest in the nation in 4th-grade reading, 4th-grade math, and 8th-grade math, and fourth in the nation in 8th-grade reading.6 This turnaround has drawn widespread attention, with news outlets and policymakers across the country citing Mississippi as a model for educational success.

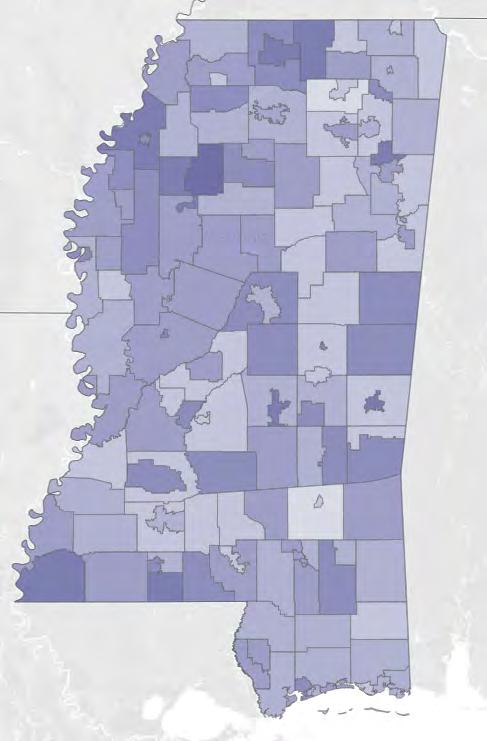

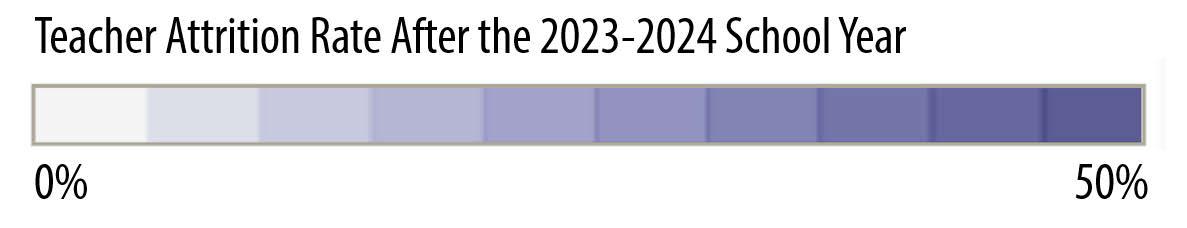

But even as student performance has improved, the state is facing a teacher workforce crisis that has worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic. After the 2018–2019 school year—prior to the pandemic—18.4% of teachers left their school districts. Attrition rose to 19.9% after the 2021–2022 school year and has remained elevated since. After the 2023–2024 school year, the statewide attrition rate stood at 19.4%, with 11 school districts losing more than 30% of their teachers.

While variations in how states define teacher attrition complicate national comparisons, research has found that Mississippi recorded the highest teacher vacancy rate in the country during the 2023–2024 school year, underscoring the severity of its teacher pipeline issues.7 The Mississippi Department of Education, educator preparation programs, and other stakeholders across the state work hard to bring new teachers into the profession, but new entrants into the profession cannot stabilize schools when the teacher pipeline is leaking faster than it can be filled.8

5 NAEP is commonly referred to as the “Nation’s Report Card.” It is administered across the nation every two years in grades 4 and 8. Unlike state-specific standardized tests, the NAEP assessment allows for comparison of student achievement between states and within states over time.

6 Matthew Chingos and Kristin Blagg, “States’ Demographically Adjusted Performance on the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress,” Urban Institute, January 29, 2025, https://www.urban.org/research/ publication/states-demographically-adjusted-performance-2024-national-assessment

7 “A Systematic Examination of Reports of Teacher Vacancy and Shortages,” Teacher Shortages in the United States, accessed November 1, 2025, https://www.teachershortages.com/

8 “CMSE Tackles Increasing Teacher Shortage with Middle Math Institutes,” University of Mississippi, accessed November 1, 2025, https://olemiss.edu/news/2024/06/cmse-tackles-increasing-teacher-shortage-withmiddle-math-institutes/index.html; “State Invests in Future Educators with $2.9 Million in Teacher Residency Grants,” Mississippi Public Broadcasting, September 30, 2025, https://www.mpbonline.org/blogs/news/ state-invests-in-future-educators-with-29-million-in-teacher-residency-grants/

Figure 1. Total Teacher Attrition Rate in Mississippi, 2016-2024.

Note that all Mississippi schools moved to remote instruction in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and most continued in a partially or fully remote model for some portion of the 2020–2021 school year.9 Teacher attrition briefly declined during the pandemic, and it has since risen and stabilized at levels higher than the pre-pandemic baseline.

Source: G. Breazeale’s calculations based on data from the Mississippi Department of Education.

9 Kayleigh Skinner, “As Reeves shutters schools, some teachers worry about sustaining distance learning,” Mississippi Today, April 14, 2020, https://mississippitoday.org/ 2020/04/14/as-reeves-shutters-schools-some-teachers-worry-about-sustaining-distance-learning/

Figure 2. Individual District Attrition Rates, 2024.

Source: G. Breazeale’s calculations based on data from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Decades of research have shown that teachers are the most important in-school factor influencing student achievement.10 If current patterns of teacher attrition do not improve, the educational progress Mississippi has worked hard to achieve could begin to erode. At Mississippi First, this has raised urgent questions: Why are so many teachers leaving their positions? And what can be done to keep them?

In 2021, we launched the Mississippi Teacher Survey to hear directly from teachers about their experiences, with the goal of identifying policies that could encourage them to remain in the classroom. At the survey’s inception, it was the most comprehensive teacher voice initiative in the state since 2007.11 Findings from this survey, along with a second iteration the following year, helped inform several key policy wins, including the creation and expansion of the Winter-Reed Teacher Loan Repayment Program and the largest teacher pay raise in state history.12, 13

Mississippi First conducted the third iteration of the Mississippi Teacher Survey in February 2025. A total of 988 public school teachers responded, representing the vast majority of the state’s public school districts and public charter schools. Their insights shed light on the stark realities of the teaching profession. Over half of surveyed teachers (54.4%) reported that they are somewhat likely or very likely to leave their current role within the next year to teach in another state, move into a non-teaching role in education, exit education entirely, or teach in another Mississippi district. The percentages of respondents who indicated a likelihood of taking the first three options closely mirrored data from our 2021 and 2022 surveys, indicating a pattern of discontent (the fourth option was new to the 2025 survey). While not all teachers will follow through on these intentions, the responses suggest that a significant share of the state’s teacher workforce is dissatisfied.

10 Jennifer King Rice, Teacher Quality (Economic Policy Institute, 2003), Executive Summary, https://www.epi.org/publication/books_teacher_quality_execsum_intro/

11 Barnett Berry and Ed Fuller, “Final Report on the Mississippi Project CLEAR Voice Teacher Working Conditions Survey,” Center for Teaching Quality, January 31, 2008, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED502195.

12 “Teacher Pay Raise A Reality,” Mississippi First, March 25, 2022, https://www.mississippifirst.org/teacher-pay-raise-a-reality/

13 “Winter-Reed Teacher Loan Repayment,” Mississippi Office of Student Financial Aid, accessed on July 1, 2025, https://www.msfinancialaid.org/wrtr/.

Table 5. Teachers’ Intended Career Actions Within the Next Year

Likely to Teach in Another State

Likely to Take Other Education Role

Likely to Teach in Different School District in Mississippi

Likely to Exit Education Entirely 16.6%24.4%22.3%35.9%

Source: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to take each of the following actions within the next year?” in 2025 survey.

To better understand intentions, we asked teachers to assess the extent to which various factors influence their professional plans. The figure below illustrates the percentage of teachers who reported that each factor had “some” or “a great deal” of impact on their career plans.

Figure 3. Teachers’ Career Influences

Source: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Strong” or “Very Strong” to the question, “Whether or not you plan to remain a Mississippi public school teacher, how much of an impact do the following factors have on your career plans?” in 2025 survey.

The results highlight the intersecting pressures that shape teachers’ decisions to stay or leave. In past reports, we have zeroed in on the top factor, compensation, while acknowledging that it is more than just pay that drives teachers out of the classroom.

In this report, we broaden our focus to examine four of the most influential factors shaping teachers’ career decisions: compensation, workload, student behavior, and school leadership.

In Part One, we present updated survey data on teachers’financial situations, making the case that each year without a teacher pay raise is effectively a pay cut.

Parts Two through Four examine research on other key factors influencing teachers’ career decisions: workload, student behavior, and school leadership. These sections draw primarily on external research, as our survey included limited questions on these topics. While future surveys will explore these areas in greater depth, we chose to address them now because they are frequently overlooked in discussions of teacher attrition in Mississippi.

In Part Five, we explore characteristics that appear to be related to teacher attrition, including career stage, district poverty, and local salary supplement size.

We conclude with policy recommendations intended to guide state leaders and district decision-makers toward practical, research-informed solutions that reflect the lived experiences of Mississippi’s educators.

Part One: Compensation

In the 2025 Mississippi Teacher Survey, 93.1% of teachers reported that compensation has a strong impact on their career decisions. In this section, we examine how Mississippi teachers’ salaries have eroded over time and what this has meant for their financial well-being.

insight

The value of a teacher’s salary has declined over the past decade and continues to erode in the absence of regular pay raises.

During the 2021-2022 school year, Mississippi ranked last in the nation for average teacher pay.14 Recognizing the urgency of this issue, state leaders passed the largest teacher pay raise in Mississippi history during the 2022 legislative session, providing an average salary increase of $5,151 per teacher.15

The 2022 pay raise temporarily improved Mississippi’s national ranking in average teacher pay. However, rising inflation quickly eroded those gains. When Mississippi First surveyed teachers at the end of 2022, 92.9% reported that inflation had an impact on their financial well-being, while only 36.2% reported the same about the pay raise.16 In the years since, inflation has remained high.17 As of 2025, Mississippi has once again fallen to 50th in the nation in average teacher pay, largely because other states have taken action to increase teacher pay in the past several years while Mississippi has not.18

Without consistent, meaningful increases, teachers’ salaries lose purchasing power over time. For example, a first-year teacher who entered the profession on a Class A license in 2025 effectively earned less than a first-year teacher on the same license in

14 “Table 211.60,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, accessed November 1, 2025, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_211.60.asp?current=yes

15 Geoff Pender, “Lawmakers pass largest teacher pay raise in Mississippi history,” Mississippi Today, March 22, 2022, https://mississippitoday.org/2022/03/22/lawmakers-pass-largest-teacher-pay-raisein-mississippi-history/

16 Toren Ballard and Grace Breazeale, “Falling Behind: Teacher Compensation and the Race Against Inflation,” Mississippi First, September 1, 2023, https://issuu.com/mississippifirst/docs/teacher-survey-brief_final

17 “12-month percentage change, Consumer Price Index, selected categories,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed on November 1, 2025, https://www.bls.gov/charts/consumer-price-index/consumer-priceindex-by-category-line-chart.htm

18 “Educator Pay in America,” National Education Association, April 29, 2025, https://www.nea.org/resourcelibrary/educator-pay-and-student-spending-how-does-your-state-rank

2024, who in turn earned less than a comparable teacher in 2023. Although the nominal salary was identical in all three years, increases in the cost of living steadily reduced its real value.

Figure 4. Salary of First-Year Teacher Over Time, in 2025 Dollars

While the nominal salary of a first-year teacher has risen over the past decade, inflation has outpaced those increases. As a result, the purchasing power of a first-year teacher’s salary has declined over time.

$50,000

$40,000

$30,000

Base Salary, First-Year Teacher with Class A License (Nominal Dollars)

Base Salary, First-Year Teacher with Class A License (July 2025 Dollars)

Source: G. Breazeale’s calculations based on “FY2025-2026 MSFF Salary Schedule,” Mississippi Department of Education, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://mdek12.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/2025/03/Salary-Schedule-for-FY26.pdf; and “CPI Inflation Calculator,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

“I have a Master’s degree and 14 years of experience. Entry-level jobs at companies like FedEx pay significantly more. With increasing inflation, I debate on leaving education all the time, even though I love what I do.”

–Mississippi Teacher

This problem persists even as teachers move up the salary schedule. While they receive annual step increases as they gain experience, these incremental raises have not kept pace with inflation, resulting in a steady erosion of purchasing power. Teachers may earn more on paper each year they remain in the classroom, but those increases have not translated into greater purchasing power in recent years.

The graph below illustrates this trend for a teacher who began their career in 2022 with a Class A license. Despite moving up the salary schedule, the teacher’s real salary declines each year, leaving them worse off in inflation-adjusted terms.

Figure 5. Decline in the Real Value of a Teacher’s Salary Over Time (Teacher Entering in 2022–2023)

Although a teacher’s nominal salary increases with years of experience, inflation has outpaced these gains in recent years. As a result, a teacher who entered the profession in 2022 has experienced declining purchasing power even while moving up the salary schedule.

$46,000

$45,000

$44,000

$43,000

$42,000

$41,000

$40,000

$39,000

Year 1 (2022-2023)Year 2 (2022-2023)Year 3 (2023-2024)Year 4 (2024-2025)

Base Salary, Teacher with a Class A License (Nominal Dollars)

Base Salary, Teacher with a Class A License (July 2025 Dollars)

Source: G. Breazeale’s calculations based on “FY2025-2026 MSFF Salary Schedule,” Mississippi Department of Education, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://mdek12.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/2025/03/Salary-Schedule-for-FY26.pdf; and “CPI Inflation Calculator,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

insight

A significant proportion of respondents are not financially secure, evidenced by their lack of ability to afford basic necessities, pursuit of second jobs, and self-reported financial status.

The decline in the real value of teacher salaries has direct and serious consequences. Our 2025 survey reveals a stark picture of the financial insecurity facing Mississippi teachers. As in previous years, we asked respondents whether their household income was sufficient to cover four basic necessities: food, housing, transportation, and medical care.

In total, a striking 63.8% of teachers reported that they struggle to afford at least one of these basic necessities, up from 54.1% in our 2022 survey.19 Likewise, the share of teachers reporting difficulty affording each individual necessity has risen since 2022.

6. Teachers with Inadequate Access to Basic Resources

Source: Percentages of teachers responding “Somewhat Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” to the question, “My household income is sufficient to afford…” in 2022 and 2025 surveys.

19 Toren Ballard and Grace Breazeale, “Eyeing the Exit: Teacher Turnover and What We Can Do About It,” Mississippi First, January 10, 2023, https://issuu.com/mississippifirst/docs/eyeing_the_exit_2023

Table

The Rising Costs of Medical Care for State Employees

Of the four basic needs included in the survey, medical care was most frequently cited as unaffordable. This reflects the growing burden of health insurance costs on Mississippi educators. As we have noted in past reports, the state heavily subsidizes health insurance premiums for employees on individual insurance plans, but premiums for employees on family plans can be prohibitively expensive.20 In 2025, an employee opting to include a spouse and two or more children on their select insurance plan faced a monthly premium of $926, or $11,112 per year.21 This amount is more than a quarter of the current minimum gross salary for a first-year teacher with a Class A license.22

“My spouse and I are both teachers. We currently do not have any children, but want to start a family. However, we already cannot afford to move from our apartment into a better family environment, and I have no idea how we would afford childcare, child-related bills, and all the other necessities for raising a baby, let alone the several children we would like to have. We have decided that one or both of us will have to leave the profession that we both love, just to be able to afford to have a family of our own.”

– Mississippi Teacher

Self-Reported Financial Strain

We asked teachers to characterize their overall financial situation by selecting one of four options: finding it difficult to get by, just getting by, doing okay, or living comfortably. Their responses further underscore the financial strain many educators face. In total, 60.0% reported they were either just getting by or finding it difficult to get by, a sharp increase from 48.4% in 2022.

20 Ballard and Breazeale,“Eyeing the Exit."

21 “State and School Employees’HealthandLifeInsurancePlan, ”MississippiDepartmentofFinanceAdministration,November2024, https://www.dfa.ms.gov/sites/default/files/Insurance%20Home/Publications/Newsletters/KYB%20Newsletter-Nov%202024%20Retiree%20Edition.pdf

22 “FY 2025-2026 MSFF Salary Schedule,”MississippiDepartmentofEducation,accessedJuly1,2025,

https://mdek12.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/2025/03/Salary-Schedule-for-FY26.pdf

Table 7. Teachers’ Self-Described Financial Situations

Source: Percentage of teachers selecting each response to the question, “Overall, which one of the following best describes how well you are managing financially these days?” in 2022 and 2025 surveys.

Second Jobs Are the Norm

One of the most direct consequences of inadequate pay is that many teachers are forced to work second jobs to make ends meet. Between 2022 and 2025, the percentage of teachers who reported that they have a second job outside of the school system increased from 35.5% to 41.4%.

Table 8. Percentage of Teachers who Work a Second Job

Source: Percentage of teachers reporting that they receive income from a second job in 2022 and 2025 surveys.

“As of now, I have to work a second job in order to maintain household expenses. In the Mississippi Delta, teacher pay is low, and housing, gas, and food are expensive. “

– Mississippi

Teacher

Mississippi’s teachers are not just underpaid; without regular, meaningful salary increases, they fall further behind financially every year they remain in the classroom. Rising costs and stagnant pay have left many teachers struggling to meet basic living expenses. The state cannot expect to recruit and retain a strong, stable teaching workforce while offering compensation that fails to meet basic living standards.

Part Two: Workload and Workplace Support

In the 2025 Mississippi Teacher Survey, 90.1% of respondents reported that their workload has a strong impact on their career plans. In this section, we explore the breadth of teachers’ responsibilities and the toll this can have on their wellbeing.

insight

Mississippi teachers face unsustainable workloads, reflecting a national trend.

The responsibilities of teachers are expansive and varied. They go far beyond delivering instruction to students. These duties can include, but are not limited to:

Instructional Duties:

Planning lessons; delivering instruction; creating assignments for students; differentiating instruction and assignments for different learning styles and stages; creating formative and summative assessments to monitor student progress; grading and providing feedback on student work and assessments; tracking data; creating anchor charts for walls in classroom; obtaining supplies for lessons; printing and copying assignments.

Classroom Management Duties:

Maintaining communication with parents and guardians; building and maintaining strong relationships with students; creating and managing systems to manage student behavior; implementing disciplinary action when necessary.

Duties Related to Students with Disabilities:

Attending Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings for students with disabilities23; creating resources to ensure compliance with students’ IEPs; completing Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) paperwork24; completing Behavior Improvement Plan (BIP) paperwork.25

Professional Duties:

Par ticipating in professional growth opportunities to maintain licensure;

23 Students with identified special needs have IEPs, which lay out the supports and services that they need to thrive in school.

24 The MTSS process is a policy adopted by the Board of Education to ensure that all students’ academic and behavioral needs are met. It involves using focused supplemental instruction (Tier II) and intensive interventions (Tier III) for students who need extra support.

25 Students who exhibit challenging behaviors have BIPs, which lay out strategies to improve their behaviors.

participating in school and district committees; participating in Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) during planning and before and after school.26

Extracurricular Duties:

Working at after-school sports events; sponsoring student clubs.

Operational Duties:

Monitoring students during lunch, arrival, and dismissal; decorating classroom; cleaning classroom.

“There’s

a lack of planning time, huge amounts of paperwork (Tier ll and Tier lll paperwork, data tracking, forms, etc.), lesson plans, and things required on walls (standards posted, ‘I can’ statements, directions to centers with pictures, etc.). The list goes on and on.”

– Mississippi Teacher

Given these numerous responsibilities, teachers receive few, if any, breaks during the school day. Times that might otherwise serve as breaks are often spent supervising students. Many teachers are required to arrive early to monitor student arrival, escort students to lunch and eat while supervising them, and remain with students during dismissal until all have left campus. Even during designated planning periods, teachers are frequently pulled into professional development sessions, administrative meetings, or conferences with parents.

“We are contracted for an 8-hour workday, but I frequently pull a 50+ hour work week. The general public just says you signed up for that. The students’ needs keep me in the classroom, but it is getting harder to stay every year.”

– Mississippi Teacher

The unsustainability of teachers’ workloads in Mississippi reflects a broader national trend. A 2024 survey from the Pew Research Center found that a large majority of U.S. teachers lack sufficient time during the workday to complete essential tasks such as grading, lesson planning, and responding to emails, with 84% reporting that their workload exceeds the hours available.27 Teachers cited being assigned excessive work, including non-instructional duties, supporting students outside of class time, and covering for absent colleagues. Additionally, 70% reported that their schools are understaffed.

26 Professional Learning Communities include groups of teachers who work together to improve their practice. They are typically organized at the school level.

27 Luona Lin, Kim Parker, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz, “How Teachers Manage Their Workload,” Pew Research Center, April 4, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/04/04/how-teachers-manage-their-workload/

insight

Educators’ heavy workloads undermine their well-being and drive burnout.

A growing body of research underscores the consequences of educators’heavy workloads. A study published in June 2025 surveyed teachers across the United States and examined the increasing dehumanization of the teaching profession, highlighting how unsustainable working conditions harm teachers’mentalandphysicalwell-being. 28 The study also explored how public discourse often disrespects and undervalues the complexity and expertise required to teach, and how this can lead to unrealistic demands on educators with limited support. A significant portion of teachers in the study reported experiencing health issues linked to job-related stress. Though they entered the profession to help others, many educators are being actively harmed by the work. The study concluded that addressing teacher shortages will require not only more material resources, but also respect for teachers’time,energy, and professional knowledge.

“It is difficult to take time off work because it only sets you further behind. This increases an already overwhelming workload that cannot be realistically completed within a typical workday. Every day that I have missed this year was due to having a sick child. Teachers need more support to ensure that they do not have to put their families behind their job.”

– Mississippi Teacher

Similar research has found that the accumulation of responsibilities without corresponding time to complete them negatively affects teachers’health, well-being, and retention. One analysis described this phenomenon as“time poverty,”emphasizing its systemic nature, and concluded that efforts to improve teacher retention or instructional quality will fall short without interventions grounded in a clear understanding of teachers’workloads.29 Put simply, reducing teachers’workloadisessentialtoimprovingretention.

28 Betina Hsieh, Alejandra Priede, and Gaelle Mounioloux, “The Great Resignation in Teaching: Illuminating an Ongoing ‘Crisis’ in Teacher Dehumanization,” Teachers and Teaching (June 2025): 1–17, doi:10.1080/13540602.2025.2526634.

29 Sue Creagh, Greg Thompson, Nicole Mockler, Meghan Stacey, and Anna Hogan, “Workload, Work Intensification and Time Poverty for Teachers and School Leaders: A Systematic Research Synthesis,” Educational Review 77, no. 2 (April 2023): 661–80, doi:10.1080/00131911.2023.2196607.

insight

Workload pressures are more acute for teachers in high-poverty schools.

According to data from the Pew Research Center, staffing shortages are especially common in high-poverty schools. These shortages force existing staff to absorb additional duties, such as covering classes during planning periods, managing behavioral issues without adequate support, or taking on administrative tasks.30 A working paper from the American Educational Research Association underscores this idea, finding that teachers in high-poverty schools are more likely to work longer hours and manage larger class sizes compared to teachers in low-poverty schools.31

In addition to these issues, the instructional challenges in high-poverty schools are typically more complex. An analysis by the Learning Policy Institute found that teachers in these schools report lower levels of parental involvement, higher rates of student absenteeism, and larger numbers of students who arrive “unprepared to learn.”32 Each of these factors increases the time and effort required for teachers to support student learning and classroom management effectively.33

Research makes clear that the teachers’ workload demands are unsustainable, particularly in high-poverty schools. Time constraints, compounded by expectations to assume non-instructional responsibilities, contribute substantially to burnout and can undermine teachers’ willingness to remain in the classroom long term.

30 Lin, Parker, and Horowitz, “How Teachers Manage Their Workload.” https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/04/04/how-teachers-manage-their-workload/

31 Motoko Akiba, Soo-yong Byun, Xiaonan Jiang, Kyeongwon Kim, and Alex J. Moran, “Do Teachers Feel Valued in Society? Occupational Value of the Teaching Profession in OECD Countries,” AERA Open 9 (2023), https://www.aera.net/Newsroom/AERA23-Study-Snapshot-Disparities-in-Teachers-Working-Conditions-Qualification-Gap-and-Poverty-BasedAchievement-Gap-in-38-Countries

32 “Unprepared to learn” is phrasing from the survey given to teachers. It is not further defined in the data.

33 Emma García and Elaine Weiss, “Challenging working environments (‘school climates’), especially in high-poverty schools, play a role in the teacher shortage,” Economic Policy Institute, May 30, 2019, https://www.epi.org/publication/school-climate-challenges-affect-teachers-morale-more-so-in-high-poverty-schools-the-fourth-report-in-theperfect-storm-in-the-teacher-labor-market-series/

Part Three: Student Behavior

In our 2025 survey, 88.2% of teachers reported that student behavior impacts their career plans. In this section, we explore the effects of student behavior on teacher well-being.

insight

Student behavior plays a critical role in shaping teachers’ daily experiences and can significantly contribute to burnout.

Teachers spend most of their day engaging directly with students and are responsible for maintaining a learning environment that supports academic growth. This becomes more challenging when students display disruptive behaviors. Even a small number of student disruptions can affect the overall classroom dynamic: teachers are forced to redirect their attention toward behavior management, compromising the academic progress of the entire class.

“I do not feel like I am able to teach adequately due to disruptive student behavior inside of the classroom.”

– Mississippi Teacher

When student behavior is consistently disruptive, it creates an environment that can feel unsafe and unsupportive for educators, undermining their morale and willingness to stay in the profession. A substantial body of research indicates that this challenge is not unique to Mississippi. In RAND’s State of the American Teacher survey, administered annually to educators nationwide, teachers have consistently ranked student behavior among their top three job-related stressors. 34

34 Sy Doan et al., “State of the American Teacher and State of the American Principal Surveys: 2022 Technical Documentation and Survey Results,” RAND, June 15, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/ RRA1108-3.html; Sy Doan, Elizabeth Steiner, and Ashley Woo, “State of the American Teacher Survey: 2023 Technical Documentation and Survey Results,“ RAND, June 21, 2023, https://www.rand.org/pubs/ research_reports/RRA1108-7.html; Sy Doan et al., “State of the American Teacher Survey: 2024 Technical Documentation and Survey Results,” RAND, June 18, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/ RRA1108-11.html

Student behavior and school climate are therefore strong predictors of teacher retention.35 Teachers are far more likely to remain in schools where behavioral expectations are clear, support systems are in place, and they are not left to manage challenging student behavior on their own. In contrast, schools with higher rates of disciplinary incidents tend to experience greater teacher turnover.36 This dynamic can become self-reinforcing: higher turnover is associated with increased office referrals and suspensions, which in turn contribute to additional turnover.37

Teachers in our survey cited not only escalating student behavior but also a lack of consistent school- and district-level discipline policies as reasons they feel unsupported. Their responses indicate that they often feel unfairly blamed or not adequately supported in managing classroom disruptions. Without support from school leadership, teachers’effectivenessinmanagingstudents’ behaviorhitsaceiling. Teachers are not asking for punitive approaches; they are asking for consistent expectations, follow-through, and support in maintaining a safe and respectful learning environment.

insight

Schools continue to grapple with the long-term effec ts of the COVID-19 pandemic on student behavior.

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers across the country reported sharp increases in student misbehavior. During the 2021–2022 school year, schools surveyed by the U.S. Department of Education reported higher rates of misconduct, rowdiness, disrespect toward teachers and peers, and frequent violations of rules related to electronic device use 38 In the same survey, 87% of public schools reported that the pandemic negatively affected students’ social-emotional development, and 84% reported negative impacts on students’ behavioral development. 39 Experts have attributed these trends, in part, to prolonged periods of social isolation, which weakened students’ social-emotional skills and their ability to meet classroom expectations. 40

These challenges persisted in subsequent school years. In a nationally representative 2023 study, 80% of teachers reported that student behavior had worsened following the pandemic. 41 Similarly, a 2025 Education Week survey found that 72% of educators believed student behavior was worse than it had been in fall 2019 42

The severity of these challenges is evident not only in increased classroom disruptions, but in the escalation of harmful behaviors. According to 2023 data from the Pew Research Center, 68% of teachers reported experiencing verbal abuse from students and 40% reported being physically assaulted, with nearly one in ten teachers reported experiencing physical assaults multiple times per

35 Barnett Berry, Kevin C. Bastian, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Tara Kini, “The Importance of Teaching and Learning Conditions,” Learning Policy Institute, January 2021, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/produc t-files/Leandro_Teacher_Working_Conditions_BRIEF.pdf

36 Alexander Bentz, “Do Student Behavior Issues Impact Teacher Retention?: Evidence from Administrative Data on Student Offenses,” Department of Economics, University of Colorado Boulder, October 30, 2023, https://www.alexanderhbentz.com/papers/bentz_discipline_live.pdf

37 https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/737522?journalCode=aje

38 “More than 80 Percent of U.S. Public Schools Report Pandemic Has Negatively Impacted Student Behavior and Socio-Emotional Development,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, July 6, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/07_06_2022.asp

39 “More than 80 Percent of U.S. Public Schools,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

40 Oscar Macias, “Navigating Post-Pandemic Student Behavior: Strategies for Teachers and School Administrators,” Association of California School Administrators, August 26, 2024, https://content.acsa.org/navigating-post-pandemic-student-behavior-strategies-for-teachers-and-school-administrators/

41 Brian Jacob, “The Lasting Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on K-12 Schooling: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Teacher Survey,” Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, August 2024, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED660202

42 Caitlynn Peetz Stephens, “Is Student Behavior Getting Any Better? What a New Survey Says,” Education Week, January 8, 2025, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/is-studentbehavior-getting-any-better-what-a-new-sur vey-says/2025/01

month. These trends underscore the intensity of behavioral challenges that educators face and the serious implications for their safety and well-being.

“Teachers are blamed for bad classroom management when students disrupt the classroom. Students have no consequences because they need to be in the classroom for instruction. Teachers are verbally and physically abused on a daily basis.”

– Mississippi Teacher

insight

Student behavior challenges tend to be more prevalent in high-poverty schools.

Students living in poverty are more likely to be exposed to instability, trauma, and chronic stress.44 This can manifest in school through both aggressive behaviors (e.g., talking back to teachers, using inappropriate body language, or showing defiance) and passive behaviors (e.g., withdrawal, slouching, or disengagement from academic tasks).45

It follows that student behavior and school climate tend to be worse in higher-poverty schools than in lower-poverty ones. A 2024 Pew Research study found that 64% of teachers in high-poverty schools rated student behavior as “fair” or “poor,” compared to just 37% of teachers in low-poverty schools.46 Additional findings from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) illustrate the disparities between school climates in high- and low-poverty settings.47

According to the EPI, teachers in high-poverty schools are:

Twice as likely to report student apathy as a serious issue;

Ten percentage points more likely to report being threatened by a student; and

Five percentage points more likely to report being physically attacked by a student.

The schools where behavior challenges are most severe are also the ones that are most in need of qualified, committed teachers. Yet these schools are often where teachers feel the most unsafe, unsupported, and overwhelmed, leading to high turnover and staffing shortages.

43 Luona Lin, Kim Parker, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz, “Challenges in the Classroom,” Pew Research Center, April 4, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/ 2024/04/04/challenges-in-the-classroom/

44 Lucine Francis, Kelli DePriest, Marcella Wilson, and Deborah Gross, “Child Poverty, Toxic Stress, and Social Determinants of Health: Screening and Care Coordination,” Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 13 (2018): 2, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6699621/

45 Mengying Li, Sara B. Johnson, Rashelle J. Musci, and Anne W. Riley, “Perceived neighborhood quality, family processes, and trajectories of child and adolescent externalizing behaviors in the United States,” Social Science & Medicine 192 (2017): 152-161, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953617304604

46 Luona Lin, Kim Parker, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz, “Problems students are facing at public K-12 schools,” Pew Research Center, April 4, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/ social-trends/2024/04/04/problems-students-are-facing-at-public-k-12-schools/

47 García and Weiss, “Challenging working environments.”

This creates a cycle in which disruptive behavior drives teachers out, creating instability and more work for those who are left, leading to more teacher attrition and a worse learning environment for students.

“Our students are allowed to do as they please with very little consequences. At the high school level, this is very difficult to deal with. I will teach a maximum of five more years.”

– Mississippi Teacher

Part Four: School and District Leadership

In our 2025 survey, 86.5% of teachers reported that school and district leadership impacts their career decisions. In this section, we explore how leaders can shape teachers’ experiences.

insight

School and district leaders play a significant role in teacher satisfaction and retention.

As teachers’ supervisors, school leaders can influence numerous aspects of the job, including class schedules, collaboration time, extracurricular expectations, and discipline policies. Leaders who are out of touch with teachers’ needs can make their jobs more challenging and amplify the challenges we have outlined throughout this report.

“We all feel incredibly micromanaged and have nowhere to turn to. Teachers have no power.”

– Mississippi Teacher

For instance, a leader who fails to enforce behavior standards can undermine a teacher’s ability to enforce a consequence ladder, and a leader who regularly assigns last-minute tasks to teachers can cause an already-unmanageable workload to feel impossible.48 In contrast, principals who advocate for their staff and promote a culture of mutual respect can relieve pressure and foster a more enjoyable and productive working environment.

Research supports the idea that principals can have a significant impact on teachers. Panel data from North Carolina indicate that more effective principals create better working conditions by providing more time during the school day to complete work, greater access to resources, and more meaningful professional development.49 Consistent with these findings, schools with higher-rated principals, based on teacher feedback, tend to experience lower teacher turnover.50

Leadership stability also matters. When principals remain in their roles over multiple years, they have the time and influence to cultivate a positive school culture, build trust with teachers, and implement consistent policies that support effective teaching. Research shows that principal retention improves teacher retention.51 Conversely, frequent leadership changes can disrupt routines, undermine morale, and erode teachers’confidence that their challenges will be addressed. Just as strong, supportive leaders can buffer against the everyday stresses of teaching, inconsistent or transient leadership can exacerbate them, leaving teachers feeling unsupported and isolated. Ensuring both effective and stable leadership is therefore a critical lever for improving teacher satisfaction and fostering professional growth.

“Instead of allowing educators to use their expertise and experience to teach effectively, we are buried under constant assessments and changing expectations that do not benefit student learning.”

– Mississippi Teacher

In our survey, teachers expressed frustration not only with building-level leadership, but also with district-level directives they view as disconnected from classroom realities. District leaders shape the policies, priorities, and expectations that guide school leaders and ultimately affect teachers. When district initiatives are misaligned with school-level needs, they can compound teachers’ frustration.

48 “The Role of Principals in Addressing Teacher Shortages,” Learning Policy Institute, February 27, 2017, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/role-principalsaddressing-teacher-shortages-brief

49 Susan Burkhauser, “How much do school principals matter when it comes to teacher working conditions?” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 39, no. 1 (2017): 126-145, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308182081_How_Much_Do_School_Principals_Matter_When_It_Comes_to_Teacher_Working_Conditions

50 Jason A. Grissom, Anna J. Egalite, and Constance A. Lindsay, “How principals affect students and schools,” Wallace Foundation 2, no. 1 (2021): 30-41, https://wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/How-Principals-Affect-Students-and-Schools.pdf

51 Stephanie Levin and Kathryn Bradley, “Understanding and Addressing Principal Turnover: A Review of the Research,” Learning Policy Institute, March 19, 2019, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/nassp-understanding-addressing-principal-turnover-review-research-report

“I feel that there are too many initiatives and directives that do not allow classroom educators to properly identify and correct student shortfalls within the classroom. It seems that everyone has a plan that they think would work great for every educator, but forget that we are not in a mass-production industry. “

– Mississippi Teacher

High-poverty schools tend to have more turnover among school leaders.

Principal quality and stability have an outsized impact on teacher retention in high-poverty schools.52 Yet, these schools are more likely to have less experienced principals and higher rates of leadership turnover. 53 A 2022 study by Mississippi First found that Mississippi schools receiving Title I funding, an indicator of student poverty, experience higher principal turnover than their counterparts that do not receive Title I funding.54 This finding is consistent with national research, which shows that schools with high percentages of low-income students are most likely to experience leadership instability.55 In these environments, teachers face greater student needs and behavioral challenges while also coping with leadership churn and shifting expectations.

52 Levin and Bradley, “Understanding and Addressing Principal Turnover.”

53 Ibid.

54 Grace Breazeale, “The Leadership Shuffle: Exploring Turnover in Mississippi’s Principal Workforce,” Mississippi First, November 11, 2022, https://w ww.mississippifirst.org/leadership-shuffle/

55 Levin and Bradley, “Understanding and Addressing Principal Turnover.”

Part Five: Who is Most at Risk of Leaving?

The challenges we have outlined in this report–compensation, workload, student behavior, and school leadership–are pushing Mississippi teachers toward the exit. But not all educators experience these challenges to the same extent, nor are all educators equally likely to consider leaving.

In this section, we disaggregate our survey data to identify several policy-relevant characteristics that are associated with a heightened risk of attrition.

insight

Teachers in the early stages of their careers are more likely than their peers to consider leaving their current role.

Among the survey respondents who have not yet reached the threshold for full retirement benefits, novice teachers (0-5 years of experience) were the most likely to consider moving to another district within Mississippi or leaving the state to teach. Early career teachers (6-11 years of experience) were the most likely to consider leaving the profession entirely or taking another role in education.

This trend is troubling. Novice teachers and early-career teachers represent long-term instructional capacity. Early-career teachers, in particular, have made it through the steep learning curve of the profession. Losing them represents not only an immediate workforce challenge but a long-term loss of institutional knowledge and expertise.

Figure 8. Likelihood of Taking Another Education

Figure 7. Likelihood of Teaching in Another State, by Career Stage.

Source: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to move to another state to teach within the next year?” in 2025 survey.

Figure 9. Likelihood of Exiting Profession Altogether, by Career Stage.

Source: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to take another role in education within the next year?” in 2025 survey.

Source: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to exit the profession entirely within the next year?” in 2025 survey.

insight

Teachers earning less than $3,000 in local salary supplements are significantly more likely

to consider moving districts.

Local salary supplements, which are funded at the district level, represent one of the most immediate levers available to improve teacher compensation. However, these supplements vary widely across Mississippi school districts, ranging from $0 to $8,700 for first-year teachers holding a Class A license. Districts with stronger local tax bases are generally able to offer larger supplements on top of the state-mandated base salary.

Our data indicate that local salary supplements may play a meaningful role in teacher retention. Compared to teachers who received more than $3,000 in local supplements, those receiving less than $3,000 were nearly twice as likely to report considering a move to another Mississippi school district. As shown in Figure 10, lower supplements appear to be associated with an increased likelihood that teachers will seek higher-paying roles elsewhere within the state.

Sources: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to take each of the following actions within the next year?” in 2025 survey; salary supplement data obtained from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Notably, the share of teachers who reported considering teaching in another state, transitioning into another role within education, or leaving the profession entirely was similar across supplement levels. The pattern suggests that while supplements may influence where teachers choose to work within the state, they are less likely on their own to determine whether teachers remain in the profession.

This finding underscores a significant takeaway of this report: compensation matters, but it is not sufficient on its own to address teacher attrition. Other factors, such as workload, student behavior, and school leadership, also play roles in shaping teachers’career decisions, and meaningful retention efforts must address these factors alongside pay.

Figure 10. Percentage of Teachers who Reported Plans to Leave the Classroom, by District Salary Supplement

insight

Teachers in high-poverty districts are more likely than their counterparts in other districts to consider every form of exit from their current classroom: teaching in another state, moving to another Mississippi school district to teach, taking another role in education, or exiting education entirely.

Our survey results show a clear relationship between school district poverty and teacher attrition risk. To measure school district poverty, we used each district’s Identified Student Percentage (ISP) from the 2024-2025 school year. “Identified students” are those enrolled in means-tested programs such as SNAP, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), or the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), as well as students identified as homeless, migrant, or runaway. A district’s ISP is calculated by dividing the number of identified students by the total number of students enrolled in the district.

Teachers working in districts with higher ISPs were more likely to report considering every type of career move included in the survey: transferring to another Mississippi district, leaving the state to teach elsewhere, taking a non-classroom role within education, or exiting the profession entirely.

11. Percentage of Teachers who Reported Plans to Leave the Classroom, by District Identified Student Percentage

Sources: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to take each of the following actions within the next year?” in 2025 survey; ISP data obtained from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Figure

These self-reported intentions are corroborated by actual attrition data from the Mississippi Department of Education. Following the 2023–2024 school year, districts with higher ISPs experienced higher rates of teacher attrition. According to our analysis, each percentage point increase in a district’s ISP was associated with a 0.22 percentage point increase in its teacher attrition rate.

Our findings mirror national data that we presented earlier in this report. Schools serving students with higher needs often present more complex working conditions, including behavioral challenges, fewer resources, and higher accountability pressures. All of these factors can increase teacher stress and burnout, pushing them to exit the classroom.

Because student poverty and local salary supplement size are often related and may jointly influence teacher attrition, we conducted an additional analysis examining how attrition risk varied by Identified Student Percentage (ISP) across school districts with different supplement levels. We compared districts offering local salary supplements below $3,000 with those offering supplements of $3,000 or more.

In both groups of school districts, the patterns described earlier in this section mostly persisted. Among teachers working in districts with salary supplements below $3,000, those in higher-poverty districts were more likely to report considering every form of exit included in the survey: moving to another Mississippi district, leaving the state to teach elsewhere, transitioning into another role in education, or exiting education entirely. As ISP increased, so did teachers’reportedlikelihoodofleaving,regardlessofthedestination.

Among teachers receiving larger local salary supplements, higher district poverty was also associated with elevated attrition risk, with one notable exception. While teachers in high-poverty districts with supplements of $3,000 or more were more likely than their peers in lower-poverty districts to consider moving to another Mississippi district, taking another role within education, or leaving education entirely, they were not more likely to consider leaving the state to teach elsewhere. This pattern suggests that stronger local financial incentives may help reduce the likelihood that teachers in high-poverty districts seek opportunities outside Mississippi, even if they do not fully offset other pressures associated with student poverty.

Figure 12. Percentage of Teachers who Reported Plans to Leave the Classroom, by Identified Student

Percentage: Districts with Salary Supplement

Below $3,000

Figure 13. Percentage of Teachers who Reported Plans to Leave the Classroom, by Identified Student

Percentage: Districts with Salary Supplement of $3,000 or Above.

Sources: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to take each of the following actions within the next year?” in 2025 survey; ISP data and salary supplement data obtained from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Sources: Percentage of teachers who responded “Somewhat Likely” or “Very Likely” to the question, “How likely are you to take each of the following actions within the next year?” in 2025 survey; ISP data and salary supplement data obtained from the Mississippi Department of Education.

Actual attrition data from the Mississippi Department of Education following the 2023–2024 school year further illuminate the relationship between student poverty and teacher turnover, controlling for local salary supplement size.

Across districts with both lower and higher local salary supplements, higher student poverty is associated with higher teacher attrition. However, the relationship is notably stronger in districts offering supplements below $3,000. In these districts, each one-percentagepoint increase in Identified Student Percentage (ISP) is associated with a 0.25-percentage-point increase in teacher attrition. By contrast, in districts offering supplements of $3,000 or more, a one-percentage-point increase in ISP is associated with a 0.10-percentage-point increase in attrition.

While these findings do not establish a causal relationship, they suggest that local salary supplements may help buffer the effects of student poverty on teacher attrition. Higher supplements appear to moderate (though not eliminate) the increased turnover risk associated with serving higher-poverty student populations, underscoring the importance of compensation as part of a broader, multifaceted retention strategy.

Part Six: Policy Recommendations

Meaningfully improving teacher retention will require a coordinated effort across all levels of the public education system. This section outlines four overarching goals and offers corresponding recommendations for the Mississippi Legislature, the Mississippi Department of Education, and local school districts.

To develop these recommendations, we drew on findings from our analyses and reviewed existing research on effective teacher retention strategies to ensure alignment with evidence-based best practices. We also consulted with colleagues in the education policy and advocacy space to gain additional perspectives. Finally, we convened a group of public school educators to review and respond to a draft of this section, ensuring that the recommendations reflect the day-to-day realities of classrooms and schools. Their feedback helped sharpen the specificity, feasibility, and relevance of each recommendation. Together, these steps ensured that the recommendations in this section are both data-driven and grounded in the lived experiences of Mississippi educators.

goal 1:

Increase Teacher Compensation to Make the Profession Financially Sustainable

Low pay remains one of the most powerful drivers of teacher attrition in Mississippi. Too many educators struggle to support themselves and their families on current salaries. Addressing this challenge will require leaders to both raise overall compensation and think more strategically about how excellence is rewarded. Across-the-board increases are essential to making teaching a viable profession, but they should be paired with models that allow highly effective educators to earn meaningfully higher pay in recognition of the impact they deliver. By lifting both the floor and the ceiling of teacher pay, Mississippi can retain its strongest teachers and strengthen the profession over the long term.

Recommendations for the Mississippi State Legislature

1. Provide an Across-the-Board Increase to Mississippi’s Teacher Salary Schedule

The legislature should provide an across-the-board increase to the statewide base salary schedule for teachers, which is the most straightforward way to improve teacher pay. This would bring Mississippi’s teacher salaries closer in line with current regional figures.

For a teacher’s salary in 2026 to have the same purchasing power it had in 2022, base pay would need to increase by approximately 12.8 percent, or about $5,500 for a first-year teacher holding a Class A license.56

Figure 14. Minimum Base Salary for Teacher with Bachelor’s Degree (2026-2027)

Note: The graph reflects projected minimum base salaries for teachers in the 2026-2027 school year as of December 2025. These could change if any of the states in the graph pass a teacher pay raise in 2026. Source: Data obtained from State Departments of Education; G. Breazeale calculation of Mississippi teacher salary with recommended pay raise.

G. Breazeale calculations, assuming a 2026 inflation rate of 2.5%.

Alabama Arkansas Tennessee

MIssissippi (without recommended pay raise)

MIssissippi (with recommended pay raise)

How much would it cost to increase the teacher salary schedule by 12.8 percent?

Based on our calculations, increasing Mississippi’s state teacher salary schedule by 12.8 percent would cost approximately $267.9 million. A detailed explanation of the methodology used to arrive at this estimate is provided in Appendix A.

It is important to consider how a salary increase would interact with the Mississippi Student Funding Formula (MSFF), the state’s primary mechanism for financing public education. The MSFF is built around a base student cost, which is then supplemented with weighted funding to account for students with additional needs.

The base student cost is recalculated every four years using a statutory formula that includes four components, three of which are directly tied to the average teacher salary. As a result, changes to the teacher salary schedule have a significant impact on overall MSFF funding levels.

We estimate that a 12.8 percent increase in the teacher salary schedule would result in an additional $276 million in MSFF base student cost funding flowing to school districts (see Appendix A for calculation). This figure does not include the additional increase in weighted funds, which would also rise because they are calculated as a function of the base student cost.

Notably, the projected increase in MSFF funding exceeds the estimated cost of implementing the salary increase at the district level. While this report does not attempt to assess or modify the MSFF, this finding suggests that policymakers may wish to revisit how the base student cost is calculated to ensure it accurately reflects districts’actualcosts.

2. Pilot a School Staffing Redesign Program

The Legislature should establish a multi-year pilot program that offers competitive grants to support districts in implementing staffing redesign models that expand the reach and impact of highly effective teachers. Traditional staffing structures often fail to fully leverage top educators’ expertise or provide meaningful career pathways, contributing to teacher turnover. High-quality redesign models create leadership roles in which excellent teachers continue classroom instruction while coaching colleagues, earning substantial salary supplements for their expanded impact.57

North Carolina launched a pilot grant program in 2016, the Advanced Teaching Roles (ATR) Program, to support districts in implementing such models. Consecutive evaluations on the program have found that ATR has a statistically significant positive impact on students’ test scores, and data has also shown that students in ATR schools are more likely to meet or exceed expected student growth than comparable schools not implementing ATR.58, 59 In addition to impacting student achievement, ATR can improve teacher satisfaction: in a 2023 program evaluation, 90% of teachers in leadership roles reported that this role contributed to their

57 “Reimagining the Teaching Role,” National Council on Teacher Quality, accessed on November 1, 2025, https://reimagineteaching.nctq.org/

58 Aaron Arenas et al., “Advanced Teaching Roles: Evaluation Report,” The William and Ida Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, October 2023, https://fi.ncsu.edu/wp-content/ uploads/sites/175/2023/09/ATR-Evaluation-Report-2023-Final.pdf; Sarah Bausell, Shaun Kellogg, and Emily Thrasher, “Advanced Teaching Roles: Annual Evaluation Report,” The William and Ida Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, November 2024,https://fi.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2024/11/ATR-Evaluation-Report-2024-FINAL.pdf; Sergio Osnaya-Prieto, “Advanced Teaching Roles program shows improved test scores, but faces funding concerns,” EdNC, October 7, 2025, https://www.ednc.org/10-07-2025advanced-teaching-roles-program-shows-improved-test-scores-but-faces-funding-concerns/

59 “Advanced Teaching Roles in North Carolina,” BEST NC, accessed on November 1, 2025, https://bestnc.org/advancedroles/

intentions to stay in the teaching profession.60 The positive outcomes of this program led the North Carolina Legislature to make the program permanent in 2020, and it continues to receive an annual budget allocation.

A Mississippi pilot, like the one North Carolina implemented in 2016, would provide districts with the resources to implement these types of models. At the conclusion of the pilot, an evaluation of student outcomes and teacher retention could guide decisions on continuing the program.

Information on the Opportunity Culture® initiative, which is the most widely used redesign model for districts receiving ATR grants in North Carolina, can be found on page 52.

Recommendations for School and District Leaders

1. Boost Local Salary Supplements and Commit to Regular Increases