BETWEEN SACRED AND CONTEMPORARY

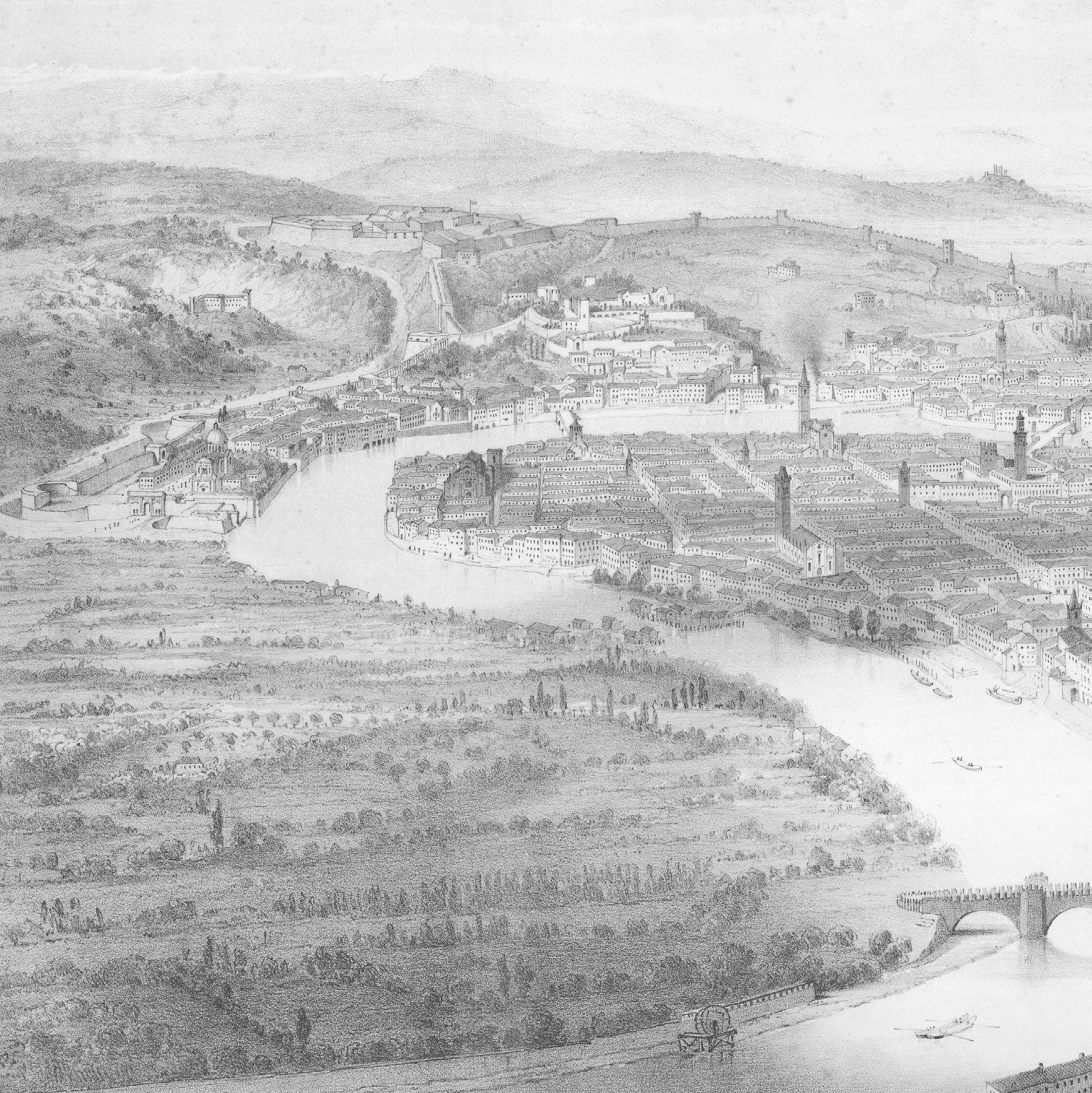

www.meglioranziartcollection.com Corso Sant’Anastasia, 34 - 37121, Verona, Italy

Ph: +39 045 8005050 info@meglioranziartcollection.com meglioranzi_art_collection MAC Meglioranzi Art Collection

Titolo dell’opera: KOTA RELIQUARIES. Between sacred and contemporary I RELIQUIARI KOTA. Tra sacro e contemporaneo

A cura di: Tiziano Meglioranzi

Progetto grafico: Antracite Studio, Anastasia Pestinova

Testi e ricerca: Anastasia Pestinova

Fotografie: Antracite Studio Foto ritratto di T. Meglioranzi: Leonardo Ferri

Ringraziamento speciale a: Libreria Antiquaria Perini

COPYRIGHT © 2025, ARTEP SRL

La responsabilità di tutti i contenuti di quest’opera è dell’autore

Prima edizione: Aprile 2025

Edizioni 03 Srls Tel. +39 045 7114134 www.edizioni03.com giovanni.p@edizionizerotre.com

Tutti i diritti riservati. Senza l’autorizzazione scritta dell’editore è vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, del presente volume, l’inserimento in circuiti informatici, la trasmissione tramite qualsiasi mezzo elettronico e meccanico, la fotocopiatura, la registrazione e la duplicazione con qualsiasi mezzo. Secondo la “Legge sulla stampa” l’eventuale citazione deve fare esplicito riferimento all’autore, al titolo e all’editore.

ISBN 9788892712744

“There

is nothing more beautiful than the feeling of discovering something rare, unique, and unrepeatable, and this is regardless of its monetary value.”

Tiziano Meglioranzi is a consultant and legal expert for Cultural Heritage, collector, expert and dealer of tribal art, archaeological artefacts, antique textiles, design objects and contemporary art. Founder and owner of the Artep gallery founded in 1981. He continues to curate and organise exhibitions, involving various institutions in his main mission: the enhancement of cultural heritage through an innovative approach. He was one of the three founders of the modern and contemporary art fair ArtVerona and the artistic director of its first edition (13-16 October 2005). He also promoted the Antiques Biennial ‘Treasures from Time’ (1996-2003). With years of experience in the field of art and a global network of contacts, the goal of the MAC - Meglioranzi Art Collection is to provide collectors and art enthusiasts with an exclusive selection of carefully curated works of art.

Tiziano Meglioranzi è consulente e perito legale per i Beni Culturali, collezionista, esperto e dealer di arte tribale, manufatti archeologici e tessili antichi, oggetti di design e arte contemporanea. Fondatore e titolare della galleria Artep, nata nel 1981, continua a curare e organizzare mostre, coinvolgendo diverse istituzioni nella sua missione principale: la valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale attraverso le lenti di un approccio innovativo. È stato uno dei tre fondatori della fiera di arte moderna e contemporanea ArtVerona e direttore artistico della sua prima edizione (13-16 ottobre 2005), nonché promotore della Biennale d’Antiquariato ‘Tesori dal Tempo’ (1996-2003). Con anni di esperienza nel campo dell’arte e una rete di contatti globali, l’obiettivo della MAC - Meglioranzi Art Collection è quello di offrire ai collezionisti e agli appassionati una selezione esclusiva di opere d’arte, curate con attenzione e dedizione.

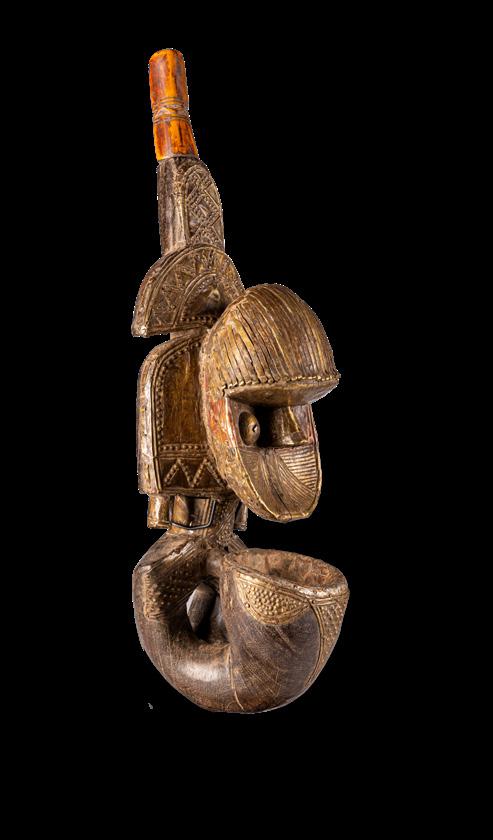

With the Premier exhibition series, we continue to explore the imaginary and visual language of Indigenous cultures, offering readers an immersive journey into a rich universe of art forms. We aim to delve into the intersections of spirituality, identity, and globalisation - universal themes intertwined with the cultural specificities of communities in continuous dialogue with modernity. Kota people from the eastern region of Gabon and parts of the Republic of Congo combine wood and metal - often copper or brass - to create reliquary figures with strong symbolic value. Known as mbulu ngulu, these reliquaries protected and honoured the memory of high-ranking ancestors, securing blessings for the clan. They were central to the rituals of the Bwete cult, moments when crucial decisions for the community were made. These works are now recognised as authentic masterpieces of African art, characterised by unique shapes and stylised faces that conveyed clan identity and continuity. Their aesthetics have influenced numerous 20th-century artists and movements, most notably Cubism. Pablo Picasso, André Derain, Henri Matisse, Constantin Brâncu ș i and many others drew inspiration from the proportions and essential forms of African sculptures, including the Kota reliquaries, to develop new visual languages. Their abstract lines, formal reduction, and iconic energy challenged traditional academic norms. These sculptures continue to captivate and engage, collected and studied by the leading museums and foundations worldwide, bearing witness to a timeless intercultural dialogue.

Tiziano Meglioranzi

Con la serie di mostre Premier continuiamo a esplorare il linguaggio immaginario e visivo delle culture indigene, offrendo ai lettori un viaggio immersivo in un ricco universo di forme artistiche. Il nostro obiettivo è indagare le intersezioni tra spiritualità, identità e globalizzazione – temi universali intrecciati alle specificità culturali di comunità in costante dialogo con la modernità. Il popolo Kota, proveniente dalla regione orientale del Gabon e da alcune aree della Repubblica del Congo, unisce legno e metallo – spesso rame o ottone – per dar vita a figure reliquiarie dal forte valore simbolico.

Conosciuti come mbulu ngulu, questi reliquiari proteggevano e onoravano la memoria degli antenati di alto rango, garantendo benedizioni al clan e intorno ai quali si svolgevano i rituali del culto Bwete, momenti in cui si prendevano decisioni cruciali per la comunità. Caratterizzate da forme uniche e volti stilizzati che esprimevano l’identità e la continuità del clan, queste opere sono oggi riconosciute come autentici capolavori dell’arte africana. La loro estetica ha influenzato numerosi artisti e movimenti del XX secolo, in particolare il Cubismo. Pablo Picasso, André Derain, Henri Matisse, Constantin Brâncu ș i e molti altri trassero ispirazione dall’arte dei Kota per sviluppare nuovi linguaggi visivi. Le loro linee astratte, la riduzione formale e l’energia iconica sfidavano, infatti, i canoni accademici tradizionali. Ancora oggi, i reliquiari Kota, raccolti dai principali musei e dalle fondazioni di tutto il mondo, continuano a suscitare fascino e interesse, testimoniando un dialogo interculturale senza tempo.

Tiziano Meglioranzi

‘Guardian’ figures are a recurring trope in African art, embodying the role of protectors and mediators between the seen and the unseen. Among the Fang people of Gabon and Cameroon, byeri, with their fierce expressions and poised stances, are believed to ward off malevolent forces. Similarly, the Mambila of Nigeria and Cameroon carve tadep, characterised by wide, alert eyes - a symbol of vigilance and metaphysical strength. These figures resonate with a broader, cross-cultural mythology of liminal guardians. In Greek lore, Cerberus, the multi-headed hound, guards the gates of the underworld, ensuring that no soul escapes and no living being intrudes. Similar figures appear in other traditions: the Egyptian god Anubis oversees the threshold between life and death, and the Japanese komainu lion-dogs protect the entrance at Shinto shrines. Across continents and centuries, such figures express a shared human impulse: to safeguard the invisible borders between the sacred and the profane.

I “guardiani” sono un tema ricorrente nell’arte africana poiché incarnano il ruolo di protettori e mediatori tra il visibile e l’invisibile. Tra i Fang del Gabon e del Camerun, i byeri, con le loro espressioni intense e le pose vigili, sono ritenuti capaci di allontanare le forze maligne. Allo stesso modo, i Mambila della Nigeria e del Camerun scolpiscono i tadep, caratterizzati da occhi grandi e attenti – simboli di vigilanza e forza metafisica. Queste figure risuonano con una più ampia mitologia transculturale dei guardiani liminali. Nella mitologia greca, Cerbero, il cane a più teste, sorveglia i cancelli dell’oltretomba, impedendo alle anime di fuggire e ai vivi di entrare. Personaggi simili compaiono in altre tradizioni: il dio egizio Anubi veglia sul passaggio tra la vita e la morte, mentre i komainu, cani-leone giapponesi, proteggono l’ingresso dei santuari shintoisti. Attraverso continenti e secoli, queste figure esprimono un impulso umano condiviso: quello di proteggere i confini invisibili tra il sacro e il profano.

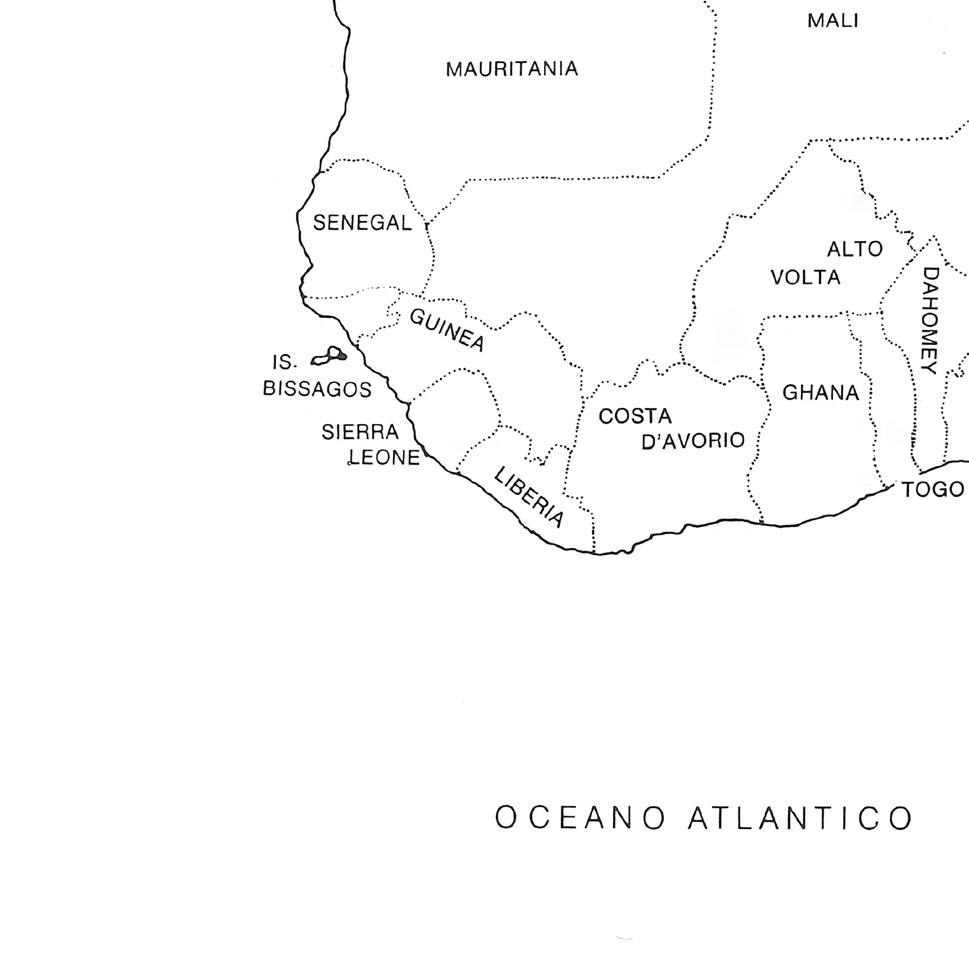

Kota (Bakota) people inhabit regions of Gabon, the Republic of Congo, and parts of Cameroon. Their cultural identity is deeply rooted in connection - both to their ancestors and among themselves as a community. This was mainly due to their mobility, which stems from their adherence to slash-and-burn farming (also known as swidden agriculture), a method involving the clearing of forest sections for cultivation, followed by relocation when the soil’s fertility declined. Consequently, the Kota could not always maintain permanent memorial sites for their ancestors due to their semi-nomadic lifestyle. To address this challenge, they - like other ethnic groups in the region, such as the Fang - preserved relics in portable baskets (mbulu) , safeguarded by sculpted guardian figures (mbulu ngulu) . These reliquary figures played a crucial strategic role, helping the Kota people to settle and claim new territory. Since the Kota were not a centralised kingdom but rather a society organised into clan-based groups, authority was often tied to lineage and, consequently, to ancestral spiritual protection. In several Bantu languages, roots such as kot- or kuta - are linked to ideas of binding or tying - concepts reflected in the Italian word ‘legare’ derived from the Latin lēgāre (‘to send’ or ‘to entrust’), which metaphorically evokes generational connection through memory and inheritance. Divided into various ethnic groups - among the northern Kota are the Mahongwe, Shamaye, Ossyeba, and Sangu (or Shake), while the southern groups include the Obamba, Ndasa, and Mbede - the Kota share rites and beliefs that reflect a fundamental notion of connection. Each group displays distinct visual styles in their reliquaries, differing in facial shapes (convex or concave), the presence or absence of a mouth, types of hairstyles, and the predominant use of metal strips or sheets.

I Kota (o Bakota) abitano regioni del Gabon, della Repubblica del Congo e alcune aree del Camerun.

La loro identità culturale è profondamente radicata nel concetto di legame, sia con gli antenati, sia all’interno della comunità. Ciò era principalmente dovuto alla loro mobilità, conseguenza della pratica dell’agricoltura itinerante mediante debbiatura (nota anche come slash-and-burn - letteralmente “incenerimento e bruciatura”), una tecnica che consiste nel disboscare porzioni di foresta per la coltivazione per poi spostarsi quando la fertilità del suolo si riduce. Di conseguenza, a causa del loro stile di vita semi-nomade i Kota non potevano sempre mantenere in modo permanente i siti commemorativi per gli antenati. Per ovviare a questa difficoltà, similmente ad altri gruppi etnici della regione, come i Fang, i Kota conservavano le reliquie custodite da figure guardiane (mbulu ngulu) in contenitori portatili (mbulu) . Questi reliquiari assumevano, quindi, un ruolo strategico fondamentale, aiutando i Kota a insediarsi e a rivendicare nuovi territori. Poiché i Kota non costituivano un regno centralizzato ma una società organizzata in gruppi clanici, l’autorità era spesso legata al lignaggio e, di conseguenza, alla protezione spirituale degli antenati. In diverse lingue bantu, radici come kot- o kuta- sono associate a concetti di legame o unione, idee che si riflettono nel termine italiano “legare” derivato dal latino lēgāre (“inviare” o “affidare”), che evoca metaforicamente la connessione generazionale attraverso la memoria e l’eredità. Divisi in vari sottogruppi etnici – tra i Kota del Nord si trovano i Mahongwe, gli Shamaye, gli Ossyeba e i Sangu (o Shake), mentre nel Sud si distinguono gli Obamba, gli Ndasa e i Mbede – i Kota condividono riti e credenze che riflettono una nozione fondamentale di connessione. Ciascun gruppo presenta stili visivi distinti nei propri reliquiari, differenziandosi per la forma del volto (convessa o concava), per la presenza o l’assenza della bocca, per i tipi di acconciature e per l’uso prevalente di lamelle o lamine metalliche.

In addition to the well-documented influence of Kota art on modernism, we can also witness an ongoing dialogue between contemporary artists and the Kota tradition today. A striking example is Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui, who works with recycled materials such as bottle caps, aluminium foil, and metal, recreating the alchemy of transforming the everyday into the sacred. His metallic, golden ‘fabrics’, reminiscent of altars, merge textiles’ fluidity with metal’s rigidity, symbolising the evolving nature of tradition itself and human resilience in times of hardship. Another compelling case is the work of Gonçalo Mabunda, a Mozambican artist who creates anthropomorphic sculptures from decommissioned weapons. The naive and pure expressions of his characters evoke guardian spirits, standing in stark contrast to the original use of materials intended for violence, revealing a tension between innocence and the power inherent in the instruments of war.

Oltre alla ben documentata influenza dell’arte Kota sul modernismo, oggi possiamo osservare un dialogo continuo tra gli artisti contemporanei e la tradizione Kota. Un esempio emblematico è quello dello scultore ghanese El Anatsui che lavora con materiali riciclati come tappi di bottiglia e fogli di alluminio e metallo, ricreando il processo alchemico che trasforma il quotidiano in sacro. I suoi “tessuti” metallici e dorati che ricordano gli altari fondono la fluidità del tessile, simbolo della natura mutevole della tradizione, con la rigidità del metallo, riferimento della resilienza di un popolo in condizioni precarie. Un altro caso significativo è l’opera di Gonçalo Mabunda, artista mozambicano che realizza sculture antropomorfe utilizzando armi smantellate. Le espressioni ingenue e pure dei suoi personaggi evocano spiriti guardiani, in radicale contrasto con l’utilizzo originale dei materiali destinati alla violenza, rivelando una tensione tra l’innocenza e il potere insito negli strumenti di guerra.

Bwete (ancestor)

Among Manongwe and Shaamye bwete literally means ‘ancestor’, yet the term extends beyond this definition to refer to a ritual system central to Kota beliefs, where the ancestors are simultaneously revered as protectors and feared for the potential danger due to their lingering spiritual presence. This ambiguity arises from the belief in the various spiritual components of an individual, each involved in the transition between life and the afterlife. As French anthropologist and renowned African art scholar Louis Perrois explains, upon passing into the afterlife, a person may either transform into a benevolent spirit that guides and protects their descendants or become a ghost ( edzu or nkuku ), failing to transition peacefully and remaining a wandering entity that poses a threat to their lineage.

Tra i Manongwe e gli Shaamye, bwete significa letteralmente “antenato”, ma il termine va oltre questa definizione e si riferisce a un sistema rituale centrale nella visione del mondo dei Kota, nel quale gli antenati sono al tempo stesso venerati come protettori e temuti per il potenziale pericolo legato alla loro presenza spirituale persistente. Questa ambiguità nasce dalla credenza nell’esistenza di diverse componenti spirituali dell’individuo, ciascuna coinvolta nella transizione tra la vita terrena e l’aldilà. Come spiega l’antropologo francese e studioso dell’arte africana Louis Perrois, nel passaggio all’aldilà una persona può trasformarsi in uno spirito benevolo, che guida e protegge i discendenti, oppure in un fantasma ( edzu o nkuku ), incapace di compiere una transizione pacifica, rimanendo così un’entità errante e potenzialmente pericolosa per il proprio lignaggio.

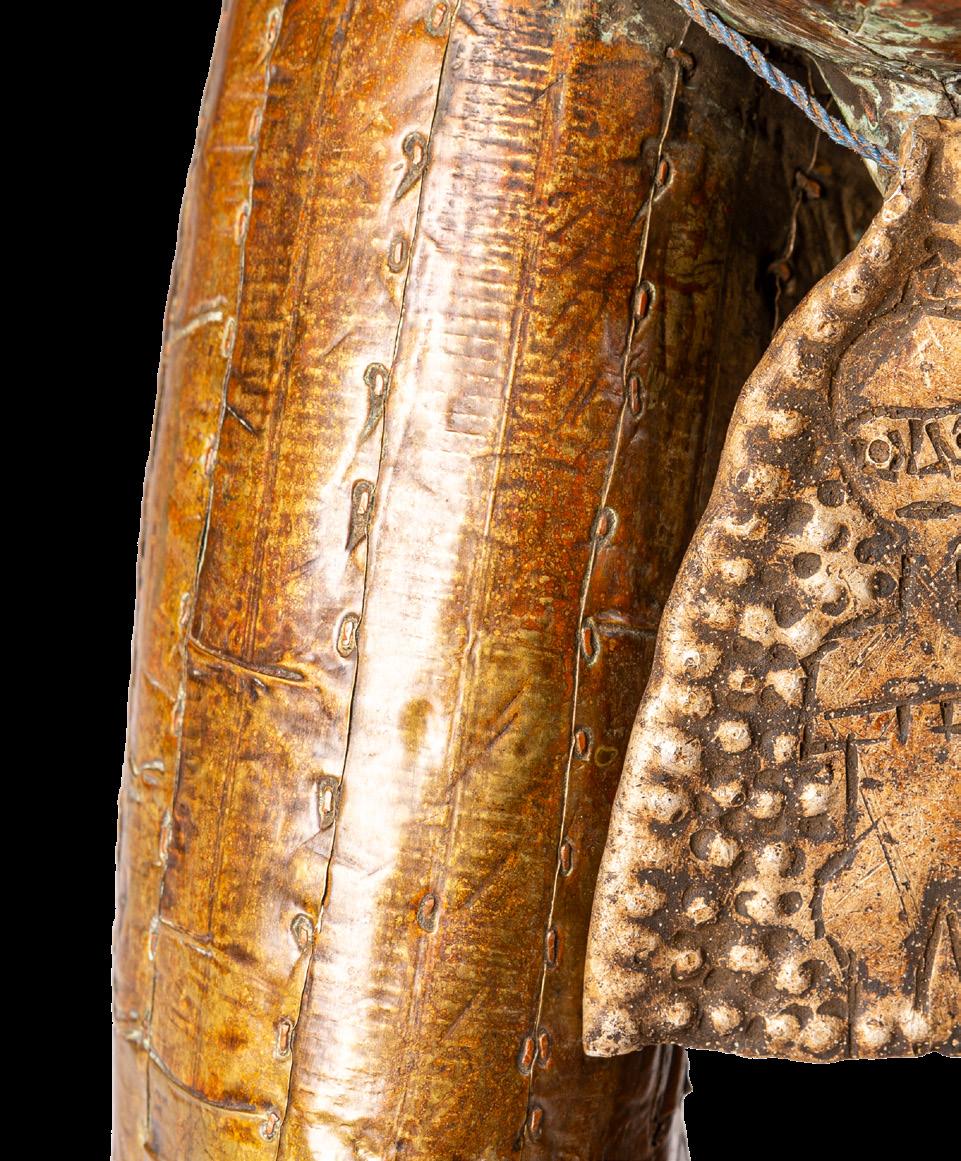

Mbulu, musuku mwangudu, or usuwu ngulu are names for a cylindrical container used to preserve and honour ancestral relics. Beyond its functional role, it symbolises the living presence of past generations and serves as a sacred focal point for family and community rituals. It is not merely a vessel but an active mediator, providing communication between realms.

Mbulu, musuku mwangudu o usuwu ngulu sono nomi che designano un contenitore cilindrico utilizzato per conservare e onorare le reliquie ancestrali. Al di là del proprio ruolo funzionale, esso simboleggia la presenza viva delle generazioni passate e funge da punto focale sacro nei rituali familiari e comunitari. Non è semplicemente un recipiente, ma un mediatore attivo che consente la comunicazione tra diverse dimensioni.

Among the Kota people, mbumba primarily denotes the symbolic imagery of the rainbow, which is further associated with the power of the python. In Central African traditions, the python is revered as a symbol of eternity and the continuous cycle of life and death. Frequently depicted on the Kota figures as a type of crown, the half-moon shape typically features carvings that vary by clan.

Tra i Kota, mbumba indica principalmente l’immaginario simbolico dell’arcobaleno, associato anche al potere del pitone.

Nelle tradizioni dell’Africa centrale, il pitone è venerato come simbolo dell’eternità e del ciclo continuo di vita e morte. Spesso rappresentato sulle figure Kota come una sorta di corona, la sua forma a mezzaluna presenta generalmente incisioni che variano a seconda del clan.

In Kota reliquary figures, the term ekwawo refers explicitly to the base of the sculpture. It’s distinctive shape, resembling two stylised arms folded protectively, embodies guardianship over the relics housed within the reliquary. The opening created by these arms is known as mubula (‘hole in a node’), serving as a sacred aperture- a portal or passage that facilitates spiritual communication. Another African art scholar, Frédéric Cloth, notes, ‘During initiations, candidates would have to look through that hole to glimpse the bwiti, in short, the essence of the divine’. In Gabonese spiritual traditions, particularly among the Tsogho people, the term bwiti encompasses profound metaphysical concepts that transcend its recognition as a religious cult.

While bwiti is widely known as a spiritual practice involving rituals and the use of the iboga plant, it also signifies the ultimate truth sought by initiates through experience.

Nelle figure dei reliquiari Kota, il termine ekwawo si riferisce esplicitamente alla base della scultura. La sua forma caratteristica, che ricorda due braccia stilizzate ripiegate in modo protettivo, incarna la funzione di custodia delle reliquie contenute all’interno della scatola cilindrica. L’apertura creata da queste “braccia” è nota come mubula (“foro di un nodo”) e funge da apertura sacra, un portale o un passaggio che facilita la comunicazione spirituale.

Un altro studioso di arte africana, Frédéric Cloth, osserva: «Durante le iniziazioni, i candidati dovevano guardare attraverso quel foro per scorgere il bwiti, in breve, l’essenza del divino». Nelle tradizioni spirituali del Gabon, in particolare tra il popolo Tsogho, il termine bwiti racchiude anche concetti metafisici profondi che vanno oltre il suo riconoscimento come culto religioso. Sebbene il bwiti sia ampiamente conosciuto come pratica spirituale che prevede rituali con l’uso della pianta di iboga, esso rappresenta anche la verità ultima che gli iniziati cercano di sperimentare.

The iron ‘tears’ visible on some Kota reliquaries are believed to correspond to what the neighbouring Teke people call mbandjuala. According to Teke oral tradition, villagers once lived surrounded by dense, thorny bushes that scratched their faces whenever they moved in and out of their settlement, leaving distinctive scars. Over time, these markings evolved into symbols of communal identity, unity, and belonging, finding expression in reliquary iconography.

Le “lacrime” in ferro visibili su alcuni reliquiari Kota sono ritenute corrispondenti a ciò che i vicini Teke chiamano mbandjuala. Secondo la tradizione orale Teke, gli abitanti del villaggio vivevano un tempo circondati da fitte siepi spinose che graffiavano i loro volti ogni volta che entravano e uscivano dal loro insediamento, lasciando cicatrici distintive. Col tempo, questi segni si sono evoluti in simboli di identità collettiva, unità e appartenenza, trovando espressione nell’iconografia reliquiaria.

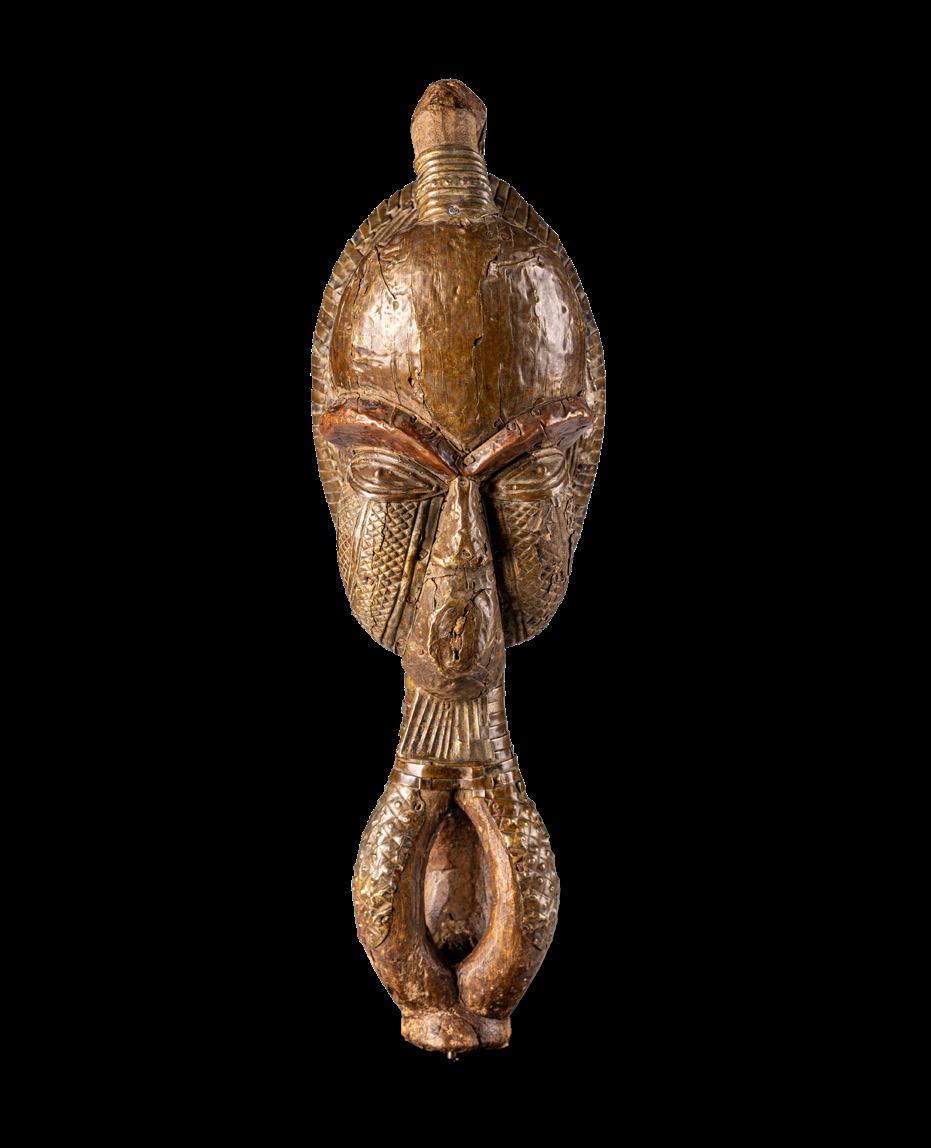

Boho na bwete is a term that refers to Kota reliquaries, typical of the northern region. It translates to ‘face of Bwété’ and is recognised for its slender, concave face, resembling the raised head of the black-necked spitting cobra (Naja nigricollis).

Boho na bwete è un termine che si riferisce ai reliquiari Kota tipici della regione settentrionale. Si traduce con “volto del Bwété” ed è riconoscibile per il viso sottile e concavo che richiama la testa sollevata del cobra dal collo nero, detto anche cobra sputatore (Naja nigricollis).

01. 25081 | height 105 cm (41.33”)

02. 24312 | height 55,5 cm (21.85”)

03. 25015 | height 49 cm (19.29”)

04. 20958 | height 64,5 cm (25.39”)

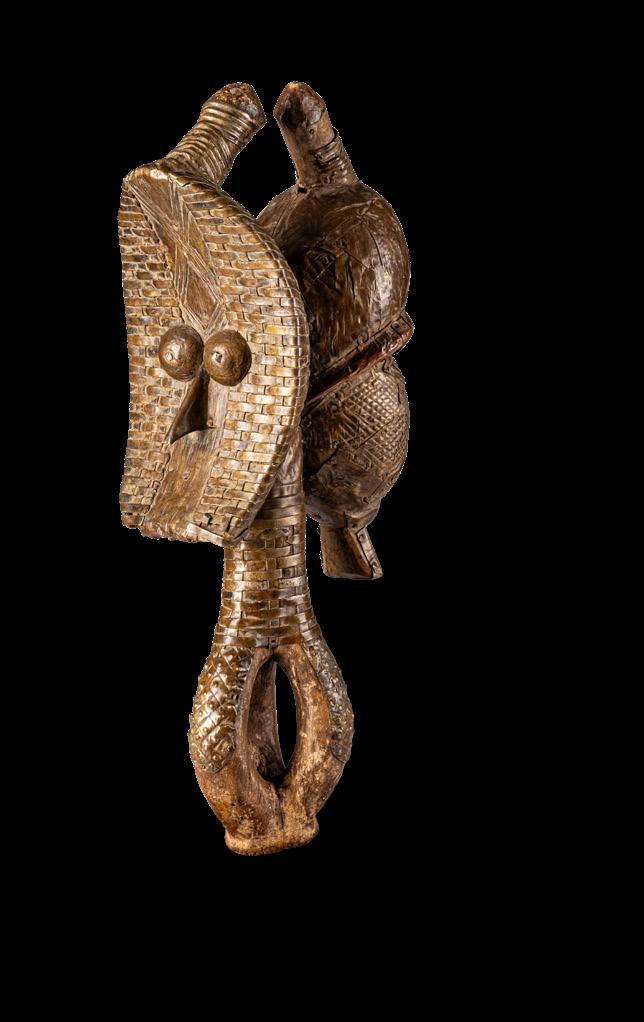

Mbulu viti, also known as mboy, refers to janiform reliquaries- figures with two faces. These figures typically combine male and female traits, symbolising complementary gender roles and the omnipresence of ancestors, whose gaze looks in multiple directions.

Mbulu viti , noto anche come mboy, indica reliquiari gianiformi, ovvero figure con due volti. Queste sculture combinano generalmente tratti maschili e femminili, simboleggiando i ruoli di genere complementari e l’onnipresenza degli antenati, il cui sguardo si proietta in più direzioni.

05. 25016 | height 41,5 cm (16.33”)

06. 24316 | height 49 cm (19.29”)

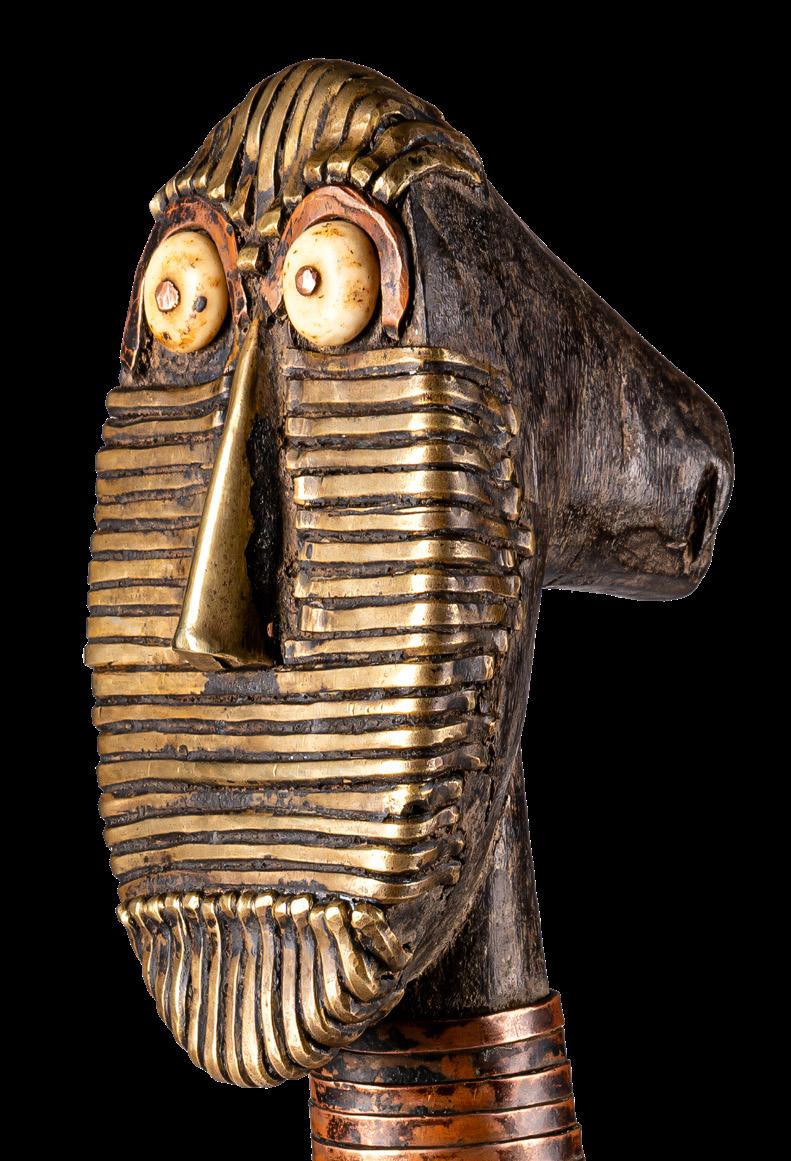

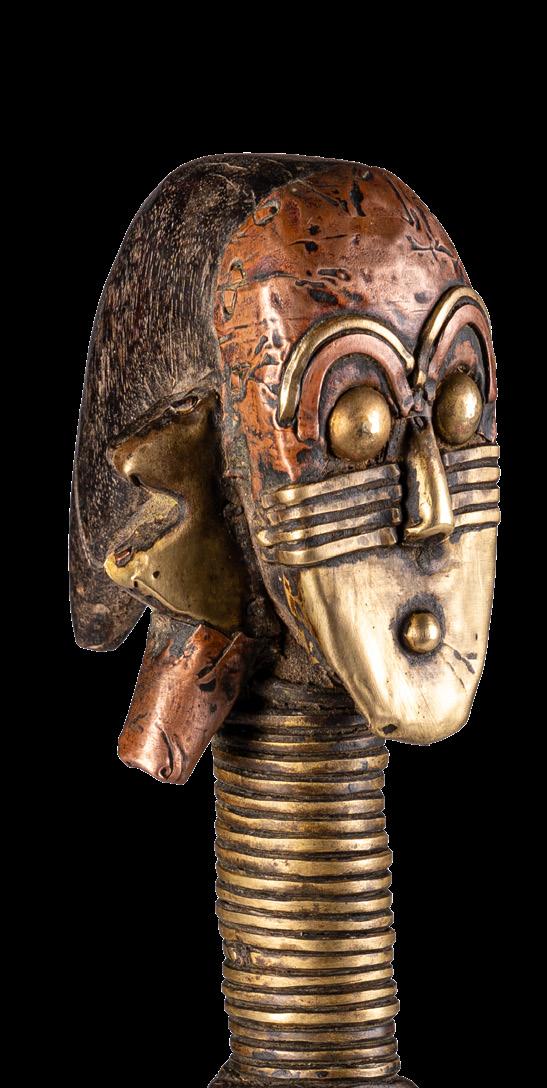

This variation of Kota reliquaries, associated with the Sangu and Shamaye groups, features distinct stylistic elements that set them apart from other types. Compared to other Kota reliquaries, most striking at first glance is their smaller size, the eyes crafted from bone, and the absence of the typical half-moon motif. This relates to a different method of storing and transporting the relics, as well as a variation in ritual practices. In addition to serving as memorials, mbumba bwete were used in divination and healing ceremonies.

Questa variante dei reliquiari Kota, associata ai gruppi Sangu e Shamaye, presenta elementi stilistici distintivi che la differenziano dagli altri tipi. Ciò che colpisce maggiormente a prima vista rispetto agli altri reliquiari Kota sono la loro dimensione ridotta, gli occhi realizzati in osso e l’assenza del tipico motivo a mezzaluna. Queste differenze sono legate a un diverso metodo di conservazione e trasporto delle reliquie, nonché a una variazione nelle pratiche rituali. Oltre a fungere da memoriali, gli mbumba bwete erano utilizzati in cerimonie di divinazione e guarigione.

07. 25043 | height 36 cm (14.17”)

08. 25045 | height 26,5 cm (10.43 ” )

09. 25044 | height 37 cm (14.56 ” )

10. 25048 | height 31 cm (12.20 ” )

11. 25041 | height 26 cm (10.24 ” )

12. 25042 | height 33 cm (13.00 ” )

13. 25046 | height 29,5 cm (11.61 ” )

14. 25047 | height 31 cm (12.20 ” )

The Mbete (or Mbede, Ambete - a Kota subgroup) reliquary statues feature a niche carved into their backs, originally sealed with a flap tied with plant fibres. The lid and ties have been lost over time in many collected specimens. This niche serves as a container for relics and magical substances, while the statue itself represents an ancestor figure. Its compact body, bent arms, and flexed legs resemble byeri guardian figures of the Fang.

Other defining features of Mbete statues include their sagittal crest-shaped hairstyle, faces that often exhibit iron teeth, and eyes inlaid with cowrie shells, giving them a striking expression intended to ward off evil spirits.

Le statue reliquarie dei Mbete (o Mbede, Ambete, un sottogruppo dei Kota) presentano una nicchia scavata sul dorso, originariamente sigillata da un lembo fissato con fibre vegetali. In molti esemplari raccolti, il coperchio e i lacci sono andati perduti nel tempo. Questa nicchia serviva come contenitore per reliquie e sostanze magiche, mentre la statua stessa rappresentava una figura ancestrale. Il corpo compatto, le braccia piegate e le gambe flesse ricordano le figure guardiane byeri dei Fang. Altri elementi distintivi delle statue Mbete includono acconciature a cresta sagittale, volti che spesso presentano denti in ferro e occhi intarsiati con conchiglie cauri che conferiscono loro un’espressione intensa, pensata per allontanare gli spiriti maligni.

15. 25075, 25076 | height 122 cm (48.03”) each

16. 25082 | height 65 cm (25.59”)

17. 24317 | height 58 cm (22.83”)

18. TMc54 | height 51 cm (20.08”)

19. 25052, 25051 | height 61 cm, 65,5 cm (24.02”, 25.78”)

20. 25083 | height 81 cm (31.90”)

21. 25049, 25050 | height 56,5 cm, 56 cm (22.24”, 22.04”)

The Ndasa type of Kota reliquary figure is known for its frequently encountered convex face, characterized by an outwardly rounded shape and prominent cheeks, although concave faces are also prevalent. It typically features a crescent-shaped design resembling a half-moon, with lateral extensions that end in forms reminiscent of a duck’s tail; double earrings are also a common element of the Ndasa style. The examples presented illustrate well this expressive range within the Ndasa aesthetic: one figure displays pronounced cheekbones and wide, flared side elements; double earrings and intricate geometric textures distinguish another, while a third combines an elongated visage with a cross motif, mbandjuala iron ‘tears’, lateral wings, and lateral pendant forms.

La figura reliquiaria dei Ndasa è nota per il volto convesso, caratterizzato da una forma arrotondata verso l’esterno e dalle guance prominenti, sebbene siano comuni anche i volti concavi. Essa presenta tipicamente un motivo a mezzaluna, con estensioni laterali che terminano con sagome che ricordano la coda di un’anatra; i doppi orecchini sono altresì un elemento ricorrente nello stile Ndasa. Gli esempi presentati illustrano bene questa varietà espressiva dell’estetica Ndasa: una figura mostra zigomi pronunciati ed elementi laterali ampi e svasati; un’altra si distingue per i doppi orecchini e le intricate texture geometriche; una terza combina un viso allungato con un motivo a croce, “lacrime” di ferro mbandjuala ed elementi laterali pendenti.

22. 25040 | height 58 cm (22.83”)

23. 25014 | height 45 cm (17.71”)

24. 24443 | height 57 cm (22.44”)

The reliquaries of the Obamba group in the Haut-Ogooué province of Gabon feature a concave face. The lateral sections often terminate in shapes that resemble earrings. The examples presented in this volume feature another distinctive trait typical of the Obamba: a massive, protruding forehead that casts a shadow over the eyes. Although some pieces display curls instead of earrings - a detail associated with the Ndasa tradition - the facial iconography, particularly the combination of a pronounced forehead and cabochon eyes, indicates that they belong to the Obamba group. This section also includes a striking example of a mbulu ngulu, expressively adorned with mbandjuala iron ‘tears’.

I reliquiari del gruppo Obamba, situato nella provincia dell’Haut-Ogooué in Gabon, presentano un viso concavo e le sezioni laterali terminano spesso in forme che ricordano orecchini. Gli esemplari presentati in questo volume mostrano un altro tratto distintivo tipico degli Obamba, una fronte massiccia e sporgente che getta un’ombra sugli occhi.

Sebbene alcuni pezzi presentino riccioli al posto degli orecchini - un dettaglio associato alla tradizione Ndasa - l’iconografia del volto, in particolare la combinazione di una fronte pronunciata e di occhi a cabochon, indica che appartengono al gruppo Obamba. Questa sezione include anche un esempio sorprendente di mbulu ngulu, ornato in modo espressivo di “lacrime” di ferro mbandjuala .

25. 25020 | height 57 cm (22.44”)

26. 25021 | height 59 cm (23.23”)

27. 25019 | height 60 cm (23.62”)

28. 24313 | height 53 cm (20.86”)

29. 25022 | height 51 cm (20.07”)

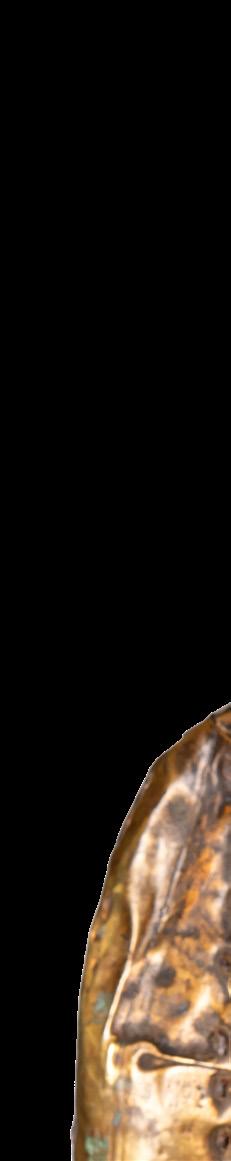

Beyond the well-known reliquary figures, the Kota carved various objects that combined sacrality and utility, illustrating how spiritual significance was woven into everyday life. Ceremonial stools and pipes carried symbolic weight beyond their practical use, often indicating the owner’s status. At the same time, certain protective elements, sometimes incorporated into architectural structures or personal spaces, were designed to ward off harmful forces and maintain spiritual balance.

Oltre alle celebri figure reliquiarie, i Kota realizzavano diversi oggetti intagliati che univano sacralità e utilità, illustrando come il significato spirituale fosse intrecciato alla vita quotidiana. Sgabelli e pipe cerimoniali avevano un valore simbolico che andava oltre il loro uso pratico, indicando spesso lo status del proprietario. Allo stesso tempo, alcuni elementi protettivi, talvolta integrati alle strutture architettoniche o agli spazi personali, erano progettati per allontanare le forze nocive e mantenere l’equilibrio spirituale.

30. 25017 | height 39,5 cm (15.55”)

31. 24314, 24315 | height 53 cm, 51,5 cm (20.86”, 20.27”)

32. 25013, 25012 | height 54 cm, 57,5 cm (21.26”, 22.64”)

Bibliography:

A. LaGamma, Eternal Ancestors: The Art of the Central African Reliquary, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2007.

F. Cloth, The rediscovery of a Kota masterpiece, Auction: Au Cœur des Arts d’Afrique: Collection Viviane Jutheau, Comtesse de Witt, Lot 17, Sotheby’s, Paris 2016.

J. Green, Material Values of the Teke Peoples of West Central Africa, Sainsbury Research Unit, University of East Anglia, Norwich 2020.

L. Perrois, Arts du Gabon. Les arts plastiques du bassin de l’Ogooué, Cahiers de l’ORSTOM, Paris 1979.

L. Perrois, Ambete-Art and the ‘Kota’ Tradition, in Id «Art Tribal» , n. 1, 2002, pp. 74-103.

L. Perrois, Visions of Africa: Kota, 5 Continents Editions, Milan 2012.

L. Perrois, G. Pestmal, Note sur la découverte et la restauration de deux figures funéraires Kota-Mahongwé (Gabon) , Cahiers de l’ORSTOM, Paris 1971, pp. 367-385.

L. Perrois, Le Bwété des Kota-Mahongwe du Gabon: Note sur les figures funéraires des populations du bassin de l’Ivindo , Cahiers de l’ORSTOM, Paris 1969.

L. Perrois, Two Reliquary Figures from Eastern Gabon In «African and Oceanic Art» , Sotheby’s, Paris 2022.

Special Issue 5: Kota-A Patrimony Rediscovered in «Tribal Art Magazine», Belgio 2015.

Reliquary Figure (Mbete), Gabon , Accession Number: 1978.412.596, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Finito di editare nel mese di Aprile 2025 per i tipi di Edizioni 03

Edizioni 03 S.r.l.s. Via Macello, 25 - 37121 Verona - Italy www.edizioni03.com EDIZIONI

SKU: 492 € 88,50