Antimicrobial Resistance

“We need evidence-based, pragmatic solutions that work locally but scale globally.”

Professor Dame Sally Davies, UK Special Envoy on Antimicrobial Resistance Page 02

“Agrifood systems remain chronically underfunded despite their central role in public health.”

Junxia Song, Senior Animal Health Officer, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Page 12

“Together, we’re driving African cross-sector action for global impact on AMR.”

Amref Health Africa Pages 10-11

AMR is a preventable global crisis

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) affects everyone, threatening our health, economies and food security. We must act on our commitments to tackle AMR, or its impact will only get worse.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global emergency. Without action, annual deaths could reach 1.9 million by 2050,1 and the global economy could lose $1.7 trillion.2 The UK alone could face $59 billion in losses, including $2.8 billion in additional healthcare costs.3 Drugresistant infections make it harder to treat diseases like HIV, malaria and tuberculosis. Dangerous fungi like Candida auris are rising sharply in European hospitals.

AMR hits hardest where vulnerability is greatest Deaths have increased by 80% since 1990 in those over 70 and are projected to double by 2050.1 Cancer patients are particularly at risk. Data shows how countries with the weakest healthcare systems and most challenging access issues to essential antibiotics and diagnostics bear the greatest AMR burden. This is a preventable crisis, but only if we act decisively and collectively.

Turning commitments into action

Last year, world leaders made a strong commitment to tackle AMR at the UN General Assembly (UNGA), including to reduce global AMR deaths by 10% by 2030. We need to turn those words into action.

As promised at UNGA, a new Independent Panel for Evidence for Action on AMR (IPEA) will launch this year. This panel will bring together the latest data to guide global policy and help countries respond effectively to AMR challenges. The panel must be scientifically independent, globally representative and inclusive of all countries and sectors. Hosting it in Africa, where the burden of AMR is greatest, would send a powerful signal.

No single country or sector can solve AMR alone

The UNGA Political Declaration gives us direction. Now, we need evidence-based, pragmatic solutions that work locally but scale globally. The new IPEA will help in this, translating the wealth of data that we have into potential solutions, helping countries to target and resource their responses.

While evidence is crucial, it must be backed by a universal commitment to act. By pooling our strengths and learning from each other, we can change the course of AMR.

References:

1. Naghavi, M et. al. The Lancet, Volume 404, Issue 10459, 1199 – 1226. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050

2. McDonnell A, et. al. 2024. Forecasting the Fallout from AMR: Economic Impacts of Antimicrobial Resistance in Humans – A report from the EcoAMR series. Paris (France) and Washington, DC (United States of America): World Organisation for Animal Health and World Bank, pp. 58.

3. https://www.cgdev.org/media/forecasting-fallout-amr-economicimpacts-antimicrobial-resistance-humans

Invisible frontlines: tackling antimicrobial resistance amid conflict and fragility

BY

Yvan J-F Hutin Director, Antimicrobial Resistance, World Health Organization

WRITTEN BY Muhammed Shaffi

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major global health threat. In fragile and conflict-affected settings, this risk is magnified, and the consequences are often invisible.

In most conflict zones, health systems become fractured with weak governance, damaged infrastructure, workforce depletion and disrupted supply chains. Policies meant for functional health systems may not work in fragile settings. We must recognise the issue and adapt AMR mitigation to fragile contexts and integrate it into humanitarian and development agendas.

hygiene supplies and clear best practices can help keep patients and frontline workers safe. Vaccines against outbreak-prone infections must also be part of humanitarian health packages. They don’t just save lives — they prevent outbreaks that drive unnecessary antibiotic use.

AMR’s dangerous foothold War and displacement may fuel drug resistance, leading to a collapse of systems to prevent, diagnose and treat infections. Trauma and injuries are common, with high risk of infection and suboptimal surgical care. Studies have documented high rates of drugresistant pathogens in wounds treated in conflict settings. Simultaneously, diagnostic capacity is minimal or destroyed and resistance patterns are unknown, undermining rational treatment decisions.

Disruptions in the antibiotic supply chain aggravate this situation. In places like Gaza, first or second choice antibiotics are often unavailable, leaving patients un-or undertreated. Counterfeit drugs also flood informal markets, fuelling misuse. The collapse of public services amplifies indirect risks and cross-border displacement spreads resistant pathogens beyond conflict zones.

Given competing priorities, it’s difficult to prioritise AMR. Humanitarian actors and governments tend to focus on immediate emergencies like epidemics and trauma care. AMR is perceived as secondary or long-term, even though it directly undermines emergency response.

Adapting AMR response to fragile settings

Infection prevention and control is the first line of defence — essential

Accurate diagnosis is equally critical. Field laboratories guide treatment even in the harshest conditions. By adapting existing rapid diagnostic systems for broader use, we can expand diagnostics access and see resistance patterns more clearly. Treatment must be smarter. Emergency health kits should follow WHO’s AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) system, with simplified stewardship protocols. Resilient supply chains for quality-assured antibiotics, diagnostics and vaccines secure availability.

However, none of this will succeed without communities at the centre. Training local health workers and first responders in hygiene, wound care and appropriate antibiotic use builds capacity and trust. Involving affected communities ensures interventions are realistic and sustainable.

International organisations and global funding mechanisms are increasingly open to fragile contexts nowadays. With innovative technologies, predictable financing, stable supply chains and qualityassured medicines, integrating AMR into humanitarian response is possible with the right policies.

World AMR Awareness Week 2025 is a reminder that resistance respects no borders. A hospital bombed, a laboratory destroyed or water systems contaminated aren’t just immediate tragedies — they drive AMR emergence and spread. If we fail to act now, AMR will erode important defence lines for some of humanity’s most vulnerable populations, with consequences that extend far beyond conflict zones.

WRITTEN

Revolutionising UTIs diagnosis and treatment in 45 minutes

WRITTEN BY

Takashi Ono Member of the Managing Board and Senior Executive Officer, Managing Director of Sysmex Corporation

WRITTEN BY Professor Carles

Alonso-Tarrés

Head of microbiology laboratory, Fundació Puigvert, Barcelona, Spain

WRITTEN BY

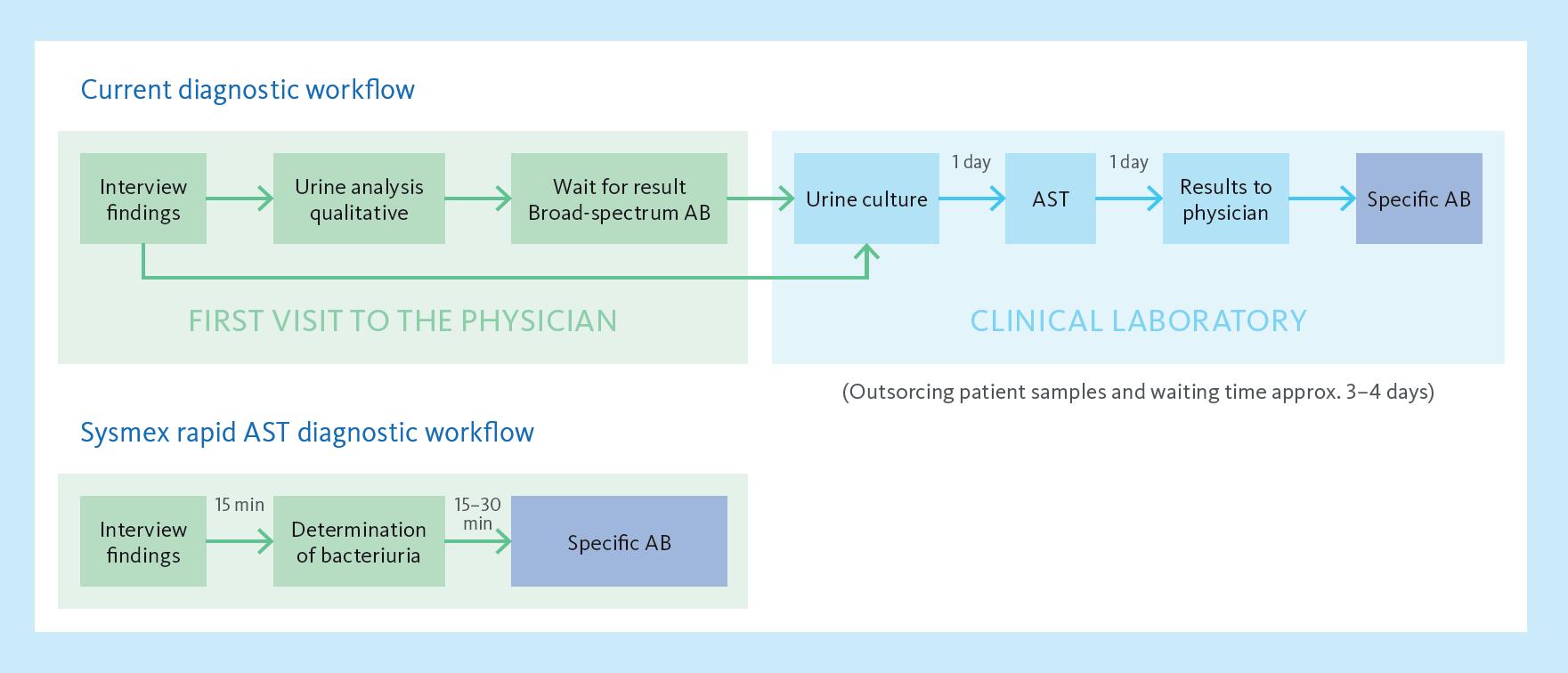

Sysmex’s PA-100 AST System is redefining the standard of care for diagnosing and treating uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs). By combining cutting-edge nanofluidic technology with rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST), the system delivers actionable results within 45 minutes — eliminating delays associated with traditional laboratory testing. In clinical settings, this advancement enables healthcare professionals to make timely, evidence-based decisions, improving patient outcomes.

Tackling UTIs with precision

UTIs are among the most common bacterial infections, affecting over 400 million people worldwide annually. Delays in diagnosis and reliance on empirical antibiotic treatments often lead to suboptimal outcomes, secondary infections and increased antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

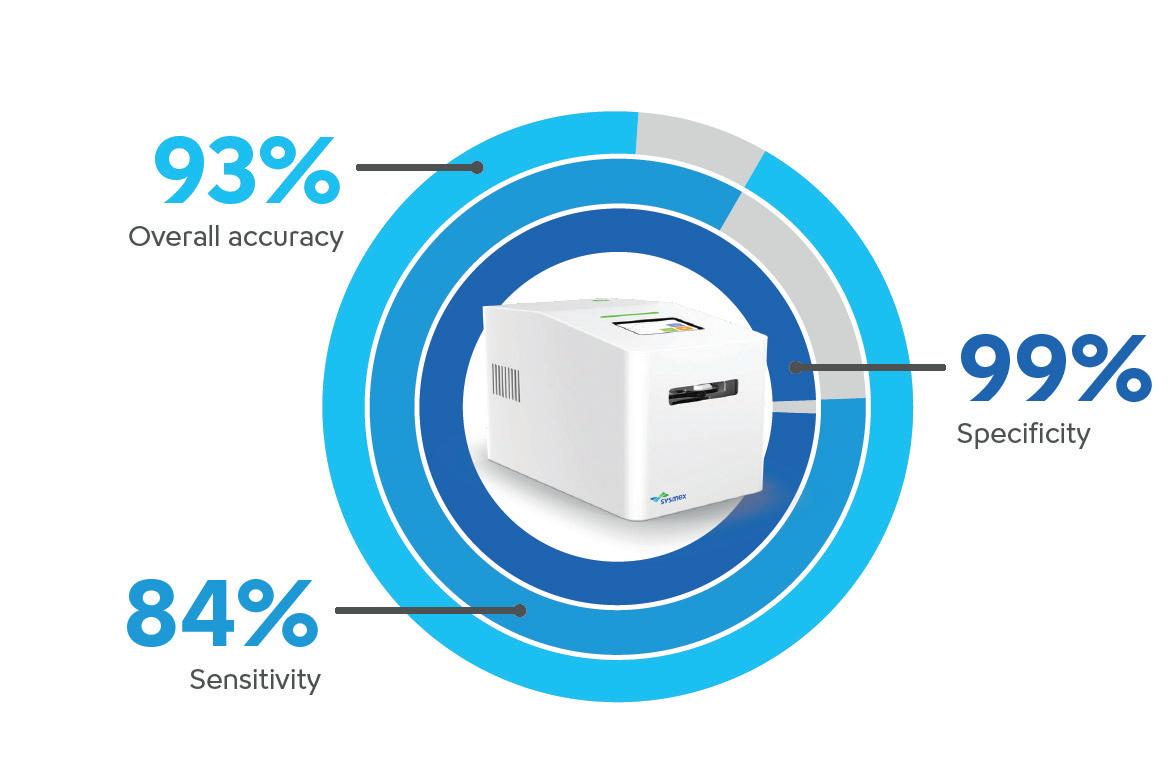

Sysmex’s PA-100 AST System bridges this gap with reported sensitivity (84%) and specificity (99%), ensuring timely and precise care while reducing reliance on broad-spectrum antibiotics — a critical step in slowing the rise of AMR.

Faster insights and lower healthcare costs

Dr Carles Alonso-Tarrés, Head of microbiology laboratory, at Fundació Puigvert, Barcelona, Spain, says: “The idea behind the technology of the PA-100 is like a dream for microbiologists and infectologists: knowing the real resistance profile of a bacterial strain immediately.”

A recently published analysis suggests potential healthcare savings based on modelled projections in Spain. Recent budget impact modelling suggests that implementing the PA-100 AST System in Spanish public healthcare settings could contribute to cost efficiencies in UTI management.

The analysis projects potential savings of approximately €323 million in the first year — assuming 100% adoption — with projections indicating cumulative cost reductions over three years. These stem from anticipated reductions in secondary complications, hospital admissions and indirect costs such as productivity losses.

Reshaping approaches to AMR globally

Beyond its economic and clinical utility, the system’s achievements have been widely recognised. Last year, the PA-100 AST System was awarded the Longitude Prize,

The Sysmex PA-100 AST System reduces the time for UTI diagnosis to just 15 minutes and determines optimal antibiotics within 30 minutes.

an £8 million award dedicated to innovations addressing AMR. This accolade underscores the system’s capacity to enhance patient outcomes and mitigate the global AMR crisis.

Professor Dame Sally Davies, Master of Trinity College, shares: “I was the instigator in the Longitude Prize of making the challenge around a rapid diagnostic to reduce AMR. I was absolutely delighted when, a decade later, this rapid diagnostic came out because it looks to me as if it is not only innovative but can make a big difference to patients.”

Targeted antibiotic prescription in 45 minutes.

Takashi Ono, Member of the Managing Board and Senior Executive Officer, Managing Director of Sysmex Corporation, comments: “By addressing one of the leading causes of antibiotic misuse, Sysmex’s PA-100 AST System aligns perfectly with global efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance. The system empowers healthcare providers with the data needed to make the right decision at the right time, benefitting patients and public health alike.”

Paid for by Sysmex

Professor Dame

Sally Davies Master of Trinity College

Images provided by Sysmex

Image provided by Sysmex

Why we still don’t have enough vaccines for bacterial threats

Scientists are uncovering how bacteria silence the immune system and exploring new ways to block this ‘off switch’ to create vaccines that could stop infections before they start.

When vaccines hit the wall

For decades, we’ve chased ever-changing bacterial surfaces with vaccines and drugs, hoping one more tweak would work. It hasn’t. For many of the deadliest pathogens — E.coli, K.pneumoniae, S.aureus and S.agalactiae — effective vaccines are missing. Expecting a different result from repeating the same playbook is nonsense.

A new target: the ‘off switch’

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: when these bacteria invade, they don’t just hide; they actively silence the immune system. Our research shows a conserved bacterial protein (GAPDH) is excreted within hours of infection, flipping an ‘off’ switch on host immunity. If your body’s alarm is disabled, antibodies against surface molecules won’t save you.

Harnessing immunity to outsmart bacteria

At Immunethep, we’re developing preventive and therapeutic agents that block a bacterial molecule which dampens our immune response — neutralising GAPDH to restore rapid, multipathogen protection. It’s like giving each individual’s immune system a pair of special glasses that allows them to see through the GAPDH ‘all-clear’ signal to recognise danger and enable a decisive response.

Spare the microbiome, slow resistance

Antibiotics carpet-bomb our microbiome and fuel antimicrobial resistance. By restoring immune function rather than blitzing bacteria, we leave beneficial microbes intact and reduce the evolutionary pressure that drives resistance. Prevention without collateral damage is the point.

What to do next

Support trials that validate the mechanism of action, measure microbiome impact alongside efficacy and fund approaches that change the rules, not repeat them. The bar for innovation should be higher: protect patients today without mortgaging public health tomorrow.

Where we are now

With the support of CARB-X, Immunethep is developing a proof-of-concept preventive vaccine against E.coli that aims for first-in-human studies by the end of 2026. In parallel, with support from PACE (Pathways to Antimicrobial Clinical Efficacy), the company is advancing monoclonal antibodies designed to treat already-infected patients, targeting the same bacterial mechanism to switch immunity on.

Finding the missing millions: how next-gen diagnostics can transform TB response

Each year, nearly 3 million people with tuberculosis (TB) are ‘missed’ by health systems – undiagnosed or unreported – allowing the world’s deadliest infectious disease to persist.1

Today’s diagnostics are accurate but too scarce, costly or unsuitable for those at most risk.

Some go untreated; others receive the wrong treatment; and drug-resistant strains spread – deepening the global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) challenge.

Far from a distant problem, TB affects over 5,000 people annually in the UK, with London among Western Europe’s highest-burden capitals.2

A new wave of TB diagnostics

After more than a decade of little progress, innovation in TB diagnosis is emerging. New tools are simpler, cheaper and more portable –with non-invasive samples like tongue swabs instead of sputum – bringing testing closer to communities.

From smaller molecular platforms to sequencing technologies that quickly identify drug resistance to multi-disease tests in development, next-generation diagnostics could transform TB care and close the gap of the ‘missing millions.’

Driving scale through investment

Scaling innovation for impact requires investment to deliver these tools. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria is one of the most effective vehicles to do this, but its success depends on donors stepping up.

The Gates Foundation recently committed $912 million to the Global Fund’s eighth replenishment. Children’s Investment Fund Foundation also pledged $50 million to support rapid country rollout of new diagnostics specifically, but far more is needed.

With simpler, cheaper tools, investments can stretch further, diagnosing more people and delivering greater impact for less. As a leader in global health and co-host of this year’s Global Fund replenishment, the UK has an opportunity to help ensure this.

TB will not be beaten with yesterday’s tools

Continued investment in next-generation tools, including diagnostics, is critical. At the Gates Foundation, we are investing across the TB innovation spectrum – including diagnostics, treatments and vaccines –because only with this full pipeline can we turn the tide against TB. Together, collective investment will yield healthier communities and stronger protection against outbreaks for all, including TB and AMR.

References:

WRITTEN BY Pedro Madureira Chief Scientific Officer,

1. WHO. 2024. Global Tuberculosis Report.

2. Gov.UK. 2025. Reports of cases of TB to UK enhanced tuberculosis surveillance systems, England: 2000 to 2024 report.

Patents power innovation against antimicrobial resistance

Discover how patent protection drives innovation in fighting antimicrobial resistance (AMR), encouraging collaboration, research investment and global access to life-saving interventions.

The rapid emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance pose significant challenges to global health, threatening the effectiveness of existing antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents. Addressing this crisis requires considered innovation in the development of new drugs, diagnostics and therapies. Patent protection plays a critical role in fostering innovation by incentivising investment in research and development.

Benefits of the patent system

Patents grant exclusive rights to inventors, enabling pharmaceutical companies and research institutions to recover not only the initial investment costs associated with research and development, but also to potentially earn profits by outlicensing and commercial sales. Without patent protection, organisations have less motivation to invest in risky and costly drug development, potentially leading to a stagnation of new therapeutic options.

Patents can also facilitate synthesis between academia, industry and governments by providing a framework for licensing and technology transfer. This collaborative approach accelerates the development, testing and distribution of new antimicrobials. Patents also promote transparency and knowledge sharing, which are vital for global efforts to combat AMR, especially in underserved regions where access to innovative treatments is limited.

Balancing access and incentives with patents

While some critics argue that the patent system can hinder access to life-saving medicines, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, balancing patent rights with public health needs is essential. Mechanisms such as voluntary licensing, patent pools and compulsory licenses can help ensure affordability and access without undermining incentives for innovation.

Patent protection is indispensable in the fight against antimicrobial resistance and infectious diseases. It drives the discovery of new drugs, fosters collaboration and ultimately contributes to improved public health outcomes worldwide. To maximise the benefits of the patent system, policymakers must create a balanced legal framework that encourages innovation while ensuring equitable access to vital medicine.

VOSSIUS is a leading European intellectual property law firm with significant experience in the life sciences sector. We work with numerous clients, from startups to large companies, to support the development of novel therapies against infectious diseases and microbial resistance.

WRITTEN BY

Yogan Pillay Director, HIV and TB Delivery, Gates Foundation

for by VOSSIUS

WRITTEN BY

Dr. Philipp Marchand Partner, Vossius, European, German and Swiss Patent Attorney

A race against time: antimalarial drug resistance

Cristina Donini, Head of Research and Early Development at Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), shares her concerns around antimalarial drug resistance (AMDR) and outlines innovative strategies to advance malaria care and protect vulnerable populations.

What are the current challenges in malaria treatments?

Complex drug regimens, resistance to medications and weakened healthcare systems. Microbes are masters of survival: they mutate and evade drugs, and the emergence of partial artemisinin resistance threatens our most effective treatments. Early warning signs like delayed parasite clearance are appearing in several African regions. It’s a race against time and every delay increases the risk of losing control over the disease.

How serious is antimalarial drug resistance, and what could happen if we don’t act?

The threat is extremely serious. Although artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) – which pair fast-acting artemisinin with a longer-lasting partner drug – remain effective, signs of delayed susceptibility of the parasite are emerging. This calls for heightened vigilance. If we fail to act promptly, we risk losing some of the tools that have controlled malaria for decades. This would be catastrophic.

How does AMDR fit within antimicrobial resistance (AMR)?

AMDR is a subset of AMR but is often overlooked. Parasites are microbes too, and resistance spreads similarly. AMDR must be recognised as a top global health priority, especially in regions where malaria remains endemic and health systems are fragile.

What options are available for malaria drug resistance, and how do we know they work?

We’re diversifying strategies by using multiple firstline therapies and expanding access to alternative

combinations. Switching or combining therapies can slow the parasite’s adaptation and extend drug effectiveness. Adding a third drug strengthens defence, protecting partner drugs and making resistance harder to develop. We’re also exploring strategies to block transmission of resistant parasites at source. These approaches help contain resistance while new therapies are being developed.

Can you tell us about MMV’s multi-layered strategy to combat resistance?

Artemether-lumefantrine (AL) is the most common of ACTs, but we aim to reduce reliance on a single treatment to reduce drug pressure on the family of ACTs. In collaboration with partners like Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and others, we’re advancing novel combinations with high-resistance barriers. Our strategy includes medicines with new mechanisms of action and optimising existing therapies – offering a stronger, more sustainable defence than traditional methods.

How does collaboration help ensure new medicines reach those who need them most?

Collaboration is central to MMV’s mission. As a product development partnership, we work with academia, industry partners, and governments to ensure new malaria treatments reach those in need. Academics bring earlystage discovery programmes, MMV accelerates drug development with industry partners, and governments help scale access. No single organisation could achieve this alone.

What innovations could secure the future of malaria treatment?

Bold science is key if we want to eliminate, rather than control, malaria. One major challenge is ensuring patients complete treatments, so simpler drug regimens are critical. Imagine a single-dose cure or a long-acting injectable that prevents malaria for months. Or an AI-driven approach that designs new medicines faster. These breakthroughs could dramatically shorten drug development timelines and transform malaria care.

Why is sustained funding so critical?

History shows that when efforts slow, resistance quickly returns, threatening years of progress. As resistance emerges, sustained funding is essential to develop nextgeneration medicines. Eliminating malaria requires consistent support from donors, governments and communities.

What keeps you motivated amid complex global challenges?

I’ve had the chance to visit hospitals in Africa, and it’s deeply moving to see how malaria impacts families and communities. Malaria is both a consequence and a cause of poverty, trapping people in cycles of illness and hardship. As a registered pharmacist, my mission is to help deliver life-saving medicines. It’s a long journey, but knowing our work is changing lives keeps me going.

Ask me how sustained funding can stop malaria resistance: doninic@mmv.org

for by MMV

INTERVIEW WITH Cristina Donini Executive Vice President, Head of Research, Early Development and Modelling, Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV)

WRITTEN BY Bethany Cooper

Image provided by Novartis

Antimicrobial resistance threatens treatment progress and the lives of cancer patients

A cancer advocacy group warns that data relating to antimicrobial infections (AMI) in cancer patients is being underrecorded in hospitals across Europe.

Cancer Patients Europe (CPE) believes the risk posed by antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in cancer care is being overlooked and that the cause of death in cancer sufferers often fails to reflect the fact that an antibiotic resistant-related infection killed them rather than their underlying condition.

Infection risk

CPE’s CEO Antonella Cardone says: “AMR is a priority for us because it is significantly impacting cancer patients; data shows that 50% of all cancer deaths are due to antibioticresistant infections, which could not be treated.”

She adds: “We cannot ignore this, and the situation is worsening to the point that, as cancer treatments impact the immune system of individuals, there is the risk that soon the use of traditional cancer treatments like chemotherapy will be compromised due to the infection risk.”

CPE — a pan-European patient organisation with 70 members from 29 countries and working on research, advocacy and delivering a united voice for the cancer community in Europe — highlights further data suggesting that cancer patients are up to three times more at risk of developing an infection compared to patients without cancer.

AMR data capture

Cardone and leading oncologists fear that such high levels of infection risk could undermine innovations such as CAR

WRITTEN

T-cell therapy and other immunotherapies. An additional concern is a lack of capture of AMR as a cause of death; when an oncology patient suffers an AMR-related death, the cause is still often recorded as cancer-related.

“This is because when people enter the hospital or a treatment pathway, they enter as cancer patients. When they die, the death is recorded as cancer rather than considering that the reason that caused the death in the end was the infection,” she adds.

“We strongly believe that if this alarming data were shown in hospital records, there would be greater attention to the topic of AMR and to the urgent need to take decisive actions by policymakers.”

Emotional burden

There is also an overlooked AMR-associated emotional burden impacting patients and families as they go through their challenging cancer treatment journey. “The risk of an infection puts a huge psychological burden on patients and families because they then tend to isolate themselves,” she says. “They avoid going to work or having a social life, but this is a vicious circle because people become depressed, which aggravates the entire situation.”

To help address this, we want more attention to be given to the prevention of infections, identifying novel effective antibiotics, as well as making them accessible to all those patients who need them most.

Biotech investment aims to tackle global AMR crisis

Policymakers have been warned that a USD1 billion fund to support development of new antibiotics is only a ‘temporary stopgap’ while urgently awaiting more robust marketsolutions to take place.

Agroundbreaking fund is helping support smaller biotech firms in the race to develop antibiotics to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Funding for AMR solutions

The AMR Action Fund is investing USD1 billion in companies that are developing urgently needed antibiotics targeting bacteria and fungi that the World Health Organization has deemed a priority because of the significant morbidity and mortality they bring.

However, CEO Henry Skinner warns that the fund is only “a partial and temporary stopgap” to the problem and is “buying time” for policymakers to deliver more permanent market solutions.

Developing promising antibiotics

With AMR being one of the world’s leading health challenges, new antibiotics are desperately needed to treat superbugs. However, due to a lack of return on investment, investors have

abandoned this area, and the pipeline of treatments is almost dry.

He explains: “Our focus is on supporting companies that are developing the most promising antibiotics in terms of potential public health benefit while raising the attention and informing policymakers on the need to change how antibiotics are valued so that upon the expiration of the Fund, other investors will support innovation to address the accelerating AMR challenge. Our goal is to support these companies, so they can obtain approval for two to four new antibiotics by 2030.”

Raising financial investment

Under the current system, a drug’s value is determined by its sales volume. That model works well in other therapeutic areas, but it is not the case with antibiotics.

“Antibiotics are not big moneymakers,” Skinner continues. “They deliver incredible value to society, cure infections and enable a wide range

of modern medical procedures like surgery, chemotherapy and organ transplants. While that’s good for public health, this critical contribution is not reflected in terms of patients’ access, which limits antibiotics’ clinical contribution and commercial potential, with investors fleeing to more financially rewarding and commercially viable areas.”

It is, he adds, a broken market that makes it exceedingly difficult for small and mid-size biotechnology companies to raise the necessary financing to advance antibiotics development.

Proper policies

Figures1 show how investors favour other areas. For example, between 2011–20, venture capital funding for US oncology companies totalled USD26.5 billion, but only USD1.6 billion for antibiotics. He warns: “Investors will continue to avoid antibiotics until policymakers enact meaningful policies that incentivise investment into antibiotic R&D, reward successful innovation and reflect the true valuecontribution of antibiotics.”

While the AMR Action Fund is investing in promising companies until policymakers enact market solutions, that will not continue forever. Acknowledging that the UK and Italy are exceptions, Skinner states there must be longer-term solutions with “proper policies in place to make a real difference,” leading to the development of novel antibiotics.

Reference:

1. Biotechnology Innovation Organization. 2022. The State of Innovation in Antibacterial Therapeutics.

INTERVIEW WITH Antonella Cardone CEO, Cancer Patients Europe

WRITTEN BY Mark Nicholls

INTERVIEW WITH Henry Skinner, PhD CEO, AMR Action Fund

BY Mark Nicholls

Novel antibiotics are failing to reach patients: here’s why and what needs to change

A

leading expert voices highly cautious optimism over the very few steps taken today that could help tackle the threat to patients’ lives and their medical care from antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

With AMR contributing to millions of deaths and costing the global economy billions of dollars, Dr Najy Alsayed, Head of Infectious Diseases in Menarini, emphasises the urgency in fighting the AMR threat, where microorganisms develop resistance to antimicrobial medicines.

While warning that the model to produce novel antibiotics is broken, Dr Alsayed says they continue to diligently work with authorities over implementing tailored effective solutions, should the political awareness be translated into decisions and decisive actions.

AMR threat

Menarini, a mid-sized European pharmaceutical company focusing on oncology, cardiovascular and respiratory and infectious diseases, sees three major elements to the AMR threat: (1) life-threatening clinical impact; (2) associated with rising healthcare costs; (3) while threatening the present and future progress of modern medicine.

Pointing to a 2019 paper in The Lancet which showed 4.95 million annual AMR deaths globally, a figure which could rise to 38.5 million by 2050, Dr Alsayed adds: “We must take decisive actions to curb this accelerating threat.”

Healthcare-associated costs of USD66 billion a year are projected

to rise to USD1.2 trillion by 2050, but he is particularly concerned about the impact on patients. In one example, he fears that half of organ transplant patients will be affected by an AMR-related infection due to their immunocompromised systems, and 30–40% of these patients will die as a result.

Broken model

Dr Alsayed indicates that at present we have a ‘broken model’ as we strive to develop and bring to the clinicians and patients novel antibiotics to support our fight against the accelerating AMR threat. This is because the current model is driven by an approach of largely restrictive, rather than appropriate, use and availability of novel antibiotics to clinicians and patients.

This has resulted in a lack of commercial viability in a large number of countries. Indeed, of the 16 antibiotics approved in the last decade, only two are available in high-income countries, with access further limited in low and middle-income countries. Lessons can be learned from how the orphan diseases crisis has been successfully addressed over the past 25 years. Facing similar barriers to novel antibiotics, with poor patient access, challenging commercial viability and sustainability, alongside lack of investment attractiveness, the action taken through the designated Orphan

Medicine EU-Legislation has led to significantly improved patient access, a more dynamic pipeline and investments, boosting the sustainable availability of orphan medicines for patients with rare diseases.

Emerging solution

We must take decisive actions to curb this accelerating threat.

Another positive step comes from the Italian reserved antibiotics model, announced during the G7 meeting in June 2024, acknowledging the ‘significant and accelerating threat of AMR and the need for novel antibiotics.’ Under this, Italian policymakers and government created an antibiotic patient access model through which novel antibiotics will be ‘evaluated, priced and reimbursed’ and ‘patient access will be facilitated accordingly.’

He also highlighted that RDTs (rapid diagnostic tests) are important in ensuring novel antibiotics are promptly and appropriately delivered to patients. With Menarini having a portfolio of novel antibiotics and collaborating with biotech companies, he believes that through the collaborative efforts and partnerships between governments and EU policymakers, pharmaceutical companies, patient associations and other AMR key stakeholders, decisive solutions will emerge to address both the current broken market and patient access failures.

Menarini

Najy Alsayed

WRITTEN BY Mark Nicholls

AMR has reached a tipping point

Could changing the way we talk about drug-resistant infections help us tackle the escalating global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis?

WRITTEN BY

Dr Manica Balasegaram

Executive Director, Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP)

The latest research suggests that AMR has now reached a critical tipping point, with the number of AMR-associated deaths expected to rise sharply, increasing by more than 70% by 2050.1

Antibiotic resistance outpaces development

We already know that we need to curb the overuse and misuse of antibiotics, both of which are driving the rise and spread of drug-resistant infections. To prevent this sudden upsurge, a change in narrative is also needed. In addition to reducing the inappropriate use of antibiotics, we must now also increase their appropriate use.

That’s because today, many people aren’t getting the antibiotics they need; either they cannot get the right antibiotics or the right drugs have not been developed in the first place. This has led to a global shift, with the most difficult to treat multidrug-resistant infections now beginning to outpace antibiotic development. As a result, more people are now dying from a lack of access to antibiotics than from drug-resistant infections, while the most difficult-to-treat infections continue to spread almost unhindered.

Targeting Gram-negative threats

In light of this, a concerted global effort is now needed towards investment in the development of innovative,

Making AMR metrics matter for global health

Antimicrobial resistance is rising despite greater global attention. Progress remains slow, threatening health worldwide and demanding urgent action.

With such slow progress, we may want to question whether we are focusing on (or at least communicating) the wrong thing. AMR isn’t a disease; it’s a biological phenomenon where microbes evolve to survive antimicrobial treatment. Currently, we communicate about AMR in terms of genotypic or phenotypic patterns, but this tells us little about whether patients can get effective treatment when they have an infection.

Limits of resistance data alone

Knowing that microbes (eg. bacteria, fungi) are resistant to certain medicines doesn’t reveal the full picture. A patient might have a ‘susceptible’ infection (sensitive to specified antimicrobials) but still face an untreatable condition if those medicines aren’t available or accessible. Conversely, even microbes deemed

new and effective antibiotic treatments for multidrugresistant infections. Specifically, we need ones that target those Gram-negative infections that pose the greatest public health threat — those included in the World Health Organization priority pathogen list.

This alone is predicted to prevent 11 million AMR deaths by 2050, while improving access to effective antibiotics could prevent more than 50 million more deaths during this period.

Antibiotic stewardship and access needed

Public-private partnerships, like the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), are already making progress on both these fronts. However, a shift in the global AMR narrative is also needed to highlight the need for appropriate access and innovation. The way to achieve this is by adopting a positive and inclusive global agenda that is focused on saving lives.

Because to avoid the AMR tipping point, we need to improve the stewardship of existing antibiotics, and that means not only reducing their inappropriate use but also ensuring that everyone has access to the appropriate antibiotics when they need them.

Reference:

to be genetically ‘resistant’ may still be treatable if the specific gene is not expressed within a specific patient or population. This can limit the usefulness of gene-based resistance data trends in the context of prescribing.

Biological complexity of resistance

The biological complexity surrounding resistance also makes it difficult to understand when interventions are working or not. Resistance can emerge unpredictably, spread in nonlinear ways and respond to multiple environmental factors, making it nearly impossible to demonstrate clear cause-and-effect relationships between prevention or control efforts and outcomes. Unfortunately, this disconnect undermines the prioritisation of AMR and the implementation of National Action Plans on AMR globally.

A clinically rooted metric is needed

In trying to find solutions to this problem, we might shift focus (at least when communicating about AMR) from resistance patterns to ‘treatability’ — a comprehensive metric that captures whether infections can actually be treated effectively in real-world settings. This would consider multiple factors, including:

• Healthcare infrastructure and access to medical facilities

• Diagnostic capabilities and speed

• Availability of appropriate antimicrobials

• Infection prevention and control measures

• Local sanitation and hygiene systems

A treatability framework would provide clearer guidance for policymakers, enable better economic assessments of interventions and help track progress toward global AMR targets more meaningfully. Crucially, it would show how investments in basic healthcare infrastructure, sanitation and diagnostic capacity contribute to fighting AMR.

Ensuring people get effective treatment

Rather than communicating through abstraction, we should focus on the ultimate goal: ensuring people can get effective treatment when they have an infection. This reframing may help garner the badly needed political will and resources needed to make tangible progress against one of our most pressing global health challenges.

WRITTEN BY Professor Holger Rohde Professor of Molecular Microbiology, University Medical Center, Hamburg-Eppendorf

1. Naghavi, Mohsen et al. 2024. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet, Volume 404, Issue 10459, 1199 – 1226.

The vanishing antibiotic pipeline is threatening global health

Without market incentives, talent loss and a declining pipeline will leave the world unprepared for the next wave of resistant infections.

WRITTEN BY

In 2019, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) caused 1.27 million deaths and contributed to another 5 million deaths worldwide.1 Left unchecked, those numbers are projected to rise by 70% by 2050.2 This isn’t a distant public health issue; it’s an urgent problem today and a direct threat to modern medicine itself. Without effective antimicrobials, routine surgeries, chemotherapy and even childbirth become perilous. Yet, research and development continue to lag far behind the urgency of our crisis.

Deadly consequences for evaporating pipeline

The workforce behind antimicrobial innovation is vanishing as a result of unique threats to the antimicrobial ecosystem. Today, only around 3,000 researchers worldwide are focused on AMR, compared to 46,000 in cancer and 5,000 in HIV/AIDS.3 That’s not just a shortage; it’s a brain drain with deadly consequences.

New antibiotics must only be used when necessary

The problem isn’t science – it’s economics. New antibiotics need to be used appropriately, used only when necessary to slow resistance. That makes traditional volume-based incentives ineffective. Put simply: the market for antimicrobials is broken. Without intervention, investment will continue to evaporate, leaving healthcare professionals without options to treat patients.

Without effective

antimicrobials, routine surgeries, chemotherapy and even childbirth become perilous.

The innovation pipeline reflects the same imbalance. In 2022, there were 35 times more cancer publications than on priority bacteria.3 Cancer patents outpaced antibiotic patents by 20 to 1.3 The result, as our research shows, is a dwindling pipeline that cannot keep pace with the scale of the threat.

Break the chain of transmission to end tuberculosis

Ending tuberculosis in high-burden settings requires us to adopt evidence-based interventions. No one should be at risk of this deadly, but curable, disease.

INew market incentives for antimicrobials are needed now

We cannot wait for this crisis to worsen. Policymakers must create new market incentives to bring antimicrobials back into the innovation spotlight. Otherwise, oncetreatable infections will again become death sentences.

References:

1. WHO. 2023. Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ antimicrobial-resistance

2. GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. 2024. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet.

3. AMR Industry Alliance. 2024. Leaving the Lab: Tracking the Decline in AMR R&D Professionals.

t is a profound injustice that millions worldwide remain at risk of tuberculosis (TB) – a disease that is both preventable and treatable. Despite decades of knowledge and effective tools, such as ultraportable radiology, rapid molecular diagnostics and shorter and more effective treatment regimens, TB continues to devastate communities.

Ending tuberculosis demands action

The problem is no longer a lack of solutions, but a lack of political will, investment and recognition that the current trajectory will not achieve the goal of ending TB by 2030 or 2035.

The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) is calling for urgent adoption of evidence-based policies that break the chain of transmission in high-burden settings. History shows the way forward: in the latter half of the 20th century, community-wide active case finding and effective treatment eliminated TB in parts of Europe, North America, Asia and Oceania. This proven strategy must now be scaled globally to prevent further illness and death.

An incredibly difficult funding and geopolitical landscape Progress is being undermined by shrinking budgets and geopolitical

instability. Cutting funding now is not only short-sighted but reckless — every dollar withheld means more lives lost and more infections spreading. Policymakers must stop treating TB control as a cost centre and start seeing it as an investment in global health security.

The return on investment is not just short-term health gains, but a reduction in new TB infections and a sustained reduction in the number of people with TB. This is good for people who are no longer at risk of suffering from, or dying due to, TB — but it also saves future costs in diagnosing and treating people with TB. Ignoring the prevention benefits of finding and treating people with infectious TB is a false economy that perpetuates the epidemic.

Now is not the time to retreat from the fight against TB

The Union urges leaders and donors to honour their commitments and dramatically increase investment in transmission-breaking investments. Communities must also be empowered to hold their governments accountable.

In 2025, no one should expect to face a high risk of TB infection. The tools to end this ancient disease exist. What is needed now is courageous resolve.

WRITTEN BY Dr Kavindhran Velen Chief Scientific Officer, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease

African coordination can turn the tide on AMR

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) demands a coordinated African continental response. It’s time to accelerate national plans and regional action in Africa.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Evelyn Wesangula East Central and Southern Africa Health Community (ECSA-HC)

WRITTEN BY Dr Jackline Kiarie Institute of Capacity Development, Amref Health Africa

Africa has the highest AMR mortality rates globally.1 One in five bacterial infections in Africa is now resistant.2 By 2050, Africa is projected to bear 40% of global AMR-related deaths.3 Without intervention, four million people in Africa will lose their lives every year from AMR-related illnesses.

We must turn the tide on AMR

When vaccines and diagnostics are out of people’s reach, illnesses are treated blindly with broadspectrum antibiotics and preventable infections spread unchecked. An Africa CDC and African Society for Laboratory Medicine study across 14 countries found that only 1.3% have sufficient bacteriology capacity. 4 Twenty-six percent of pharmacy healthcare workers surveyed in 28 African countries thought that antibiotics can be used to treat viral infections,5 and 55% of people in Africa self-prescribe antibiotics.6

These patterns of misuse also affect animal health. Amref Health Africa found that one in five animal owners in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Zambia occasionally use human medicine to treat animals due to gaps in veterinary care. 7

Yet, across many African nations, there is limited access to quality antibiotics. Over-the-counter sales of substandard or counterfeit drugs fuel antibiotic misuse and resistance.

These inequities create the perfect conditions for resistant strains to emerge and spread.

Strong continental frameworks to stop the spread

The African Union Taskforce on AMR provides a continental coordination mechanism, driving One Health policy priorities and adoption of AMR National Action Plans. It plays an essential role in feeding Africa-specific evidence and integrating African priorities into global action platforms like the Quadripartite Joint Secretariat on AMR.

With increased laboratory capacity to collect and analyse samples from hospitals, clinics, farms and the environment, we can better detect resistant strains.

These cooperative partnerships work to unite human, animal, plant and environmental health actors. By coordinating surveillance and evidence generation projects like Mapping Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use Partnership (MAAP), they can produce data to guide national policy. They are coordinating training and lab strengthening to make AMR testing more available and reliable. With increased laboratory capacity to collect and analyse samples from hospitals, clinics, farms and the environment, we can better detect resistant strains.

Coordination challenges slow down the response

These are strong continental One Health frameworks, but implementation often remains siloed. National human health, animal health and environment ministries run separate surveillance data systems and regulatory policies.

Lack of systems to generate reliable data, inconsistent data sharing and lack of harmonised standards delay timely detection and response. Without national data feeding regional platforms, it is difficult to coordinate regional data analysis to map

patterns and trends. This uneven capacity creates ‘blind spots’ where resistant strains can spread across borders with no early warning.

Limited domestic financing and heavy donor dependence undermine sustainability. Nearly a decade on from the development of National Action Plans, just 5% of African NAPs are fully funded. And without mandatory reporting, few countries enforce stewardship or report progress. Private sector and community actors are often underrepresented in AMR coordination forums. Behaviour change communication campaigns are often sporadic and not coordinated across Africa.

African leadership is driving AMR action

Initiatives like the African Leadership for AMR Action, led by Amref Health Africa and funded by GSK, are helping to bridge the gap.

It brings together private and community health sectors, One Health leaders in national governments and regional coordination bodies to strengthen leadership and local ownership for AMR action. It supports cross-sector workforce capacity building on AMR to drive more effective Antimicrobial Stewardship. It drives better community AMR understanding through integrating AMR education and awareness interventions into community health programmes and coordinating advocacy and media campaigns. Working at the national and regional levels, it enhances multisectoral action to drive cohesive and sustainable AMR mitigation efforts.

Similarly, the Health Emergency Preparedness Response and Resilience project, spearheaded by the East Central and Southern Africa (ECSA) Health Community and funded by the World Bank, has prioritised building regional and country level capacities to better implement AMR interventions. It aligns countries to common standards and its Ministers’ Conference and Community of Practice on AMR and Infection Prevention and Control convenes stakeholders, optimises regional expertise and keeps AMR high on the political agenda.

Our joint continental action and partner driven efforts create a regional architecture to strengthen systems. With evidence-based interventions, stronger coordination, sustainable financing and cross-sector enforcement, we are driving progress in the fight against AMR. In this way, together, we will safeguard Africa’s future health.

References:

1. World Health Organization Africa. 2024. Addressing the challenges of antimicrobial resistance in Africa.

2. World Health Organization. 2025. Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report 2025.

3. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2024. The Lancet. Table S17, Appendix 1.

4. Osena, Gilbert et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Africa: A retrospective analysis of data from 14 countries, 2016-2019. PLoS medicine vol. 22,6 e1004638. 24 Jun. 2025, doi:10.1371/journal. pmed.1004638

5. Agiri O, Osena G, Bahati F, Dill D, Kalanxhi E, Ashiru-Oredope D, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices survey on antimicrobial resistance and stewardship among pharmacy healthcare workers in 28 African countries. BMJ Global Health. 2025;10:e019151. https://doi.org/10.1136/ bmjgh-2025-019151

6. Yeika, Eugene Vernyuy, et al. 2021. Comparative assessment of the prevalence, practices and factors associated with self-medication with antibiotics in Africa. Tropical medicine & international health: TM & IH vol. 26,8 (2021): 862-881. doi:10.1111/tmi.13600

7. Amref Health Africa. Antimicrobial Landscape Analysis in Select African Countries Report (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Zambia).

8. Wesangula, E.; Chizimu, J.Y.; Mapunjo, S.; Mudenda, S.; Seni, J.; Mitambo, C.; Yamba, K.; Gashegu, M.; Nhantumbo, A.; Francis, E.; et al. A Regional Approach to Strengthening the Implementation of Sustainable Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Five Countries in East, Central, and Southern Africa. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 266.

The five steps for a stronger African One Health response to AMR

No single sector can solve Africa’s antimicrobial resistance (AMR) challenge on its own. Only a One Health response — uniting human, animal and environmental health — can curb AMR and protect communities.

Wellcome Trust and Kenyan Ministry of Health to research AMR emergence and resistance patterns of selected infections in Kenya — can strengthen evidence and ensure it shapes national and regional decision-making.1

3. Prevent infection

Every infection we prevent reduces the need for antibiotics and slows resistance. Infections spread rapidly where clean water, sanitation and hygiene are lacking or where health facilities fall short on infection prevention and control. Policy documents recognise this link, but evidence tying WASH and AMR remains weak.

All 47 WHO African Region countries have AMR National Action Plans framed around One Health. Yet, coordination between human, animal, agriculture and environmental sectors remains limited. Veterinary, health and environmental systems often operate in silos, with poor data sharing and weak sub-national collaboration. Five key steps are needed to strengthen this response.

1. Improve AMR awareness and understanding across

The fight against AMR starts with awareness. Farmers, health workers, pharmacists, veterinarians and communities all influence how antibiotics are used. Many countries have awareness strategies in place, but we still lack a clear picture of what people actually know or do. Recent Amref Health Africa research showed huge variations in AMR awareness and knowledge among community members, human health workers and animal health workers surveyed in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya and Zambia.

Without that awareness baseline, campaigns risk missing their audience. Amref is working with the Africa CDC to implement an AMR regional messaging framework. This will mobilise schools, clinics, community groups and agricultural networks to deliver clear, practical information about the dangers of antibiotic misuse and the importance of responsible use.

2. Integrate surveillance and research

Surveillance systems form the backbone of any AMR response, yet in many African countries, laboratories are poorly equipped, health facilities are underresourced and data rarely flows between human, animal and environmental sectors. This leaves dangerous blind spots in detecting resistant strains or understanding how they spread.

A One Health approach builds integrated surveillance that captures data from hospitals, veterinary clinics, farms and water sources. Research partnerships linking universities, ministries and agriculture departments — such as the collaboration between The Kenya Medical Research Institute,

One Health connects the dots. It pushes for investment in water and sanitation for households, health facilities, schools, farms and markets. Breaking the chain of infection matters as much in barns and fields as in hospitals. This is critical for Africa, which carries the largest global burden of communicable diseases.

4. Optimise the use of antimicrobials

Antimicrobial stewardship is gaining ground in human health systems, but animal health often falls behind. Livestock use accounts for 70% of antibiotic use worldwide.2 Farmers still use antibiotics in livestock (mostly without laboratory tests or prescriptions), fuelling resistance that spreads back into human populations.

While many countries have policies to regulate use, enforcement is weak. A One Health approach closes this gap. It develops stewardship programmes that apply equally across hospitals, pharmacies and veterinary practices. Training health workers and farmers side by side on correct prescribing, dosing and alternatives creates a culture shift that reduces misuse.

5. Build the economic case for investment Financing ties these efforts together. Yet, too often, AMR work relies on short-term donor funding, leaving it vulnerable to the tectonic shifts caused by the cuts to global health funding. Africa needs a compelling economic case that shows the cost of inaction and the shared benefits of action.

Investment must support not only new medicines and diagnostics, but also the systems — labs, surveillance, education, stewardship — that allow them to work.

The One Health framework makes this case clear: smart investment protects lives, food systems, livelihoods and economies.

Collaboration across human, animal and environmental health isn’t optional; it’s the only path to a safer, healthier future.

References:

1. KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme. Antimicrobial resistance.

2. The Fairr Initiative. 2024 Protein Producer Index. Key antibiotics and animal health findings.

WRITTEN BY Dr George Kimathi Director, Institute for Capacity Development, Amref Health Africa

WRITTEN BY Dr Fuysa Goma Animal Health Focal Point and Assistant Director, Zambian Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock

Why capable workforces are key to containing AMR

Reciprocal learning is key to ensuring we have a global health force well-equipped to identify, control and contain AMR.

WRITTEN BY Victoria Rutter CEO, Commonwealth Pharmacists Association

Workforce capability building is a vital intervention in the fight to contain and control AMR; international learning partnerships remain one of the most cost-effective ways to strengthen health systems in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) while generating mutual benefit for partners in high-income settings.

Exchange that strengthens systems

Facilitating learning across national boundaries is a powerful and costeffective way to drive innovation and build resilience. Structured partnerships not only strengthen local capacity but also bring ‘reverse innovation’ and global learning back to the high-income health systems. Upskilling healthcare workers to improve antimicrobial prescribing, strengthen laboratory testing and develop locally appropriate infection prevention measures all play a crucial role in controlling AMR. At the same time, global partners gain insight into innovative, resource-efficient practices, leadership under constraint and community engagement models that enrich their own approaches to health security.

lead to lasting change. At Lira Regional Referral Hospital in Uganda, a collaboration with University Hospitals Dorset NHS Trust led to a fourfold reduction in the inappropriate use of high-cost antibiotics such as Meropenem. In turn, NHS teams have reported applying insights from Uganda to their own antibiotic stewardship and diagnostics pathways – showing how innovation and leadership flow in both directions.

Structured partnerships not only strengthen local capacity but also bring ‘reverse innovation’.

The transformative power of partnerships CPA, with our partner GHP, supports 30 African-UK health partnerships which demonstrate how mutual learning can

AIn Kenya, a partnership between Kakamega County Hospital and Cambridge Global Health Partnerships enabled the local production of alcohol-based hand rub and integrated infection control into staff appraisals. The approach was later adapted by UK partners and offered lessons in sustainable, locally owned quality improvement.

Better professionals, better outcomes For LMIC professionals, the two-way model unlocks access to skills and tools that improve patient health outcomes. For partners, it strengthens global competence, fosters cultural humility and drives innovation through exposure to new ideas and diverse approaches. By framing global health partnerships as opportunities for bidirectional learning, we promote a more equitable approach to health. This model supports a stronger, more connected global workforce equipped to tackle AMR.

Responsible practices that can help safeguard our food systems

Policy and collaboration across sectors

AMR demands collaboration across the agriculture, health and environment sectors. National Action Plans (NAPs), developed with international support, offer frameworks for action. However, only a small fraction of NAPs is fully costed and budgeted, limiting their implementation.

Applying proven best practices across farms and food systems is key to preserving the effectiveness of antimicrobials.

ntimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens the effectiveness of medicines essential for people and animals. In agrifood systems, antimicrobials can treat and control disease in livestock, aquaculture and plants. When these substances are misused, resistant microorganisms can develop and spread through food, water and the environment.

For example, routine antibiotic use in poultry feed to promote growth could result in resistant bacteria like Salmonella, posing risks to consumers. Reducing such risks requires coordinated, science-based action at every stage of food production.

Putting prevention first Keeping animals healthy is essential to reducing AMR. Improved hygiene,

strong biosecurity and vaccination are proven strategies. In aquaculture, good water quality and balanced feeding practices helps reduce disease outbreaks. Integrated pest management in crops offers alternatives to chemical treatments. These practices not only lower AMR risks but also support safer and more sustainable production. In Zimbabwe, poultry farmers supported by FAO and national authorities reduced antimicrobial use by improving hygiene and recordkeeping.1 In Cambodia, farmer Khem Samay adopted cleaner housing and vaccination, using antibiotics only when necessary.2 These examples demonstrate that preventing and reducing antimicrobial use is not only possible but practical.

Agrifood systems remain chronically underfunded compared to other sectors, despite their central role in food security and public health. The One Health approach, which recognises the links between the health of people, animals, plants and ecosystems, is essential.

Turning commitments into action

The 2024 UN General Assembly Political declaration of the high-level meeting on AMR has reaffirmed the urgency of tackling AMR, but progress depends on putting commitments into practice. Strengthening farmers’ access to training on good practices, investing in surveillance and encouraging responsible antimicrobial use are all essential.

Applying best practices across agrifood systems is a collective responsibility to preserve antimicrobials’ effectiveness, protect food security and sustain our planet’s health.

References:

1. FAO, 2025. Zimbabwe makes strides in reducing antimicrobial use in poultry with FAO support. FAO Regional Office for Africa.

2. FAO, 2025. From routine to resilient: reducing antibiotics on the farm, Takeo Province, Cambodia.

WRITTEN BY Junxia Song Senior Animal Health Officer, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Patient-derived organoids are de-risking clinical drug development

Biotechnology company merges with a leading global life science and technology company to enhance its offering of patient-derived organoid services for clinical drug development.

Drug development is a long, costly and high-risk process, often taking upwards of 10–15 years, and typically costing over £1 billion for each new therapy.

Drug candidate attrition rates

Despite significant investment, around 90% of drug candidates fail, as findings from preclinical research are extremely difficult to translate to human models.

Sylvia Boj, CSO of HUB Organoids, explains: “Traditional animal models and cell lines don’t capture the complexity of human tissue. While primary human cells do offer more relevant insights, they can’t easily be expanded or preserved, and the differences between donor samples make results difficult to reproduce.”

Patient-derived organoids

With patented technology, HUB Organoids has developed patient-derived ‘mini-organs in a dish’ from both healthy and diseased tissues, to close the gap between the lab and clinic. Cutting-edge services include drug screening, custom assay development and co-clinical testing. Boj continues: “Organoids overcome traditional challenges, as they can be expanded, cryopreserved and used repeatedly, ensuring consistent data from the same group of donors over time.”

The company’s mission has always been to provide the most physiologically relevant models possible to help accelerate therapy development. Boj explains: “Animal

Afabicin: A new generation of antibiotics to fight AMR

An independent biopharmaceutical company is committed to developing tomorrow’s standard of care, with first-in-class novel antibiotic afabicin (Debio 1450) showing remarkable promise in bone and joint infections.

With surging AMR-infection coupled with a lack of alternatives to combat resistant pathogens, AMR is rapidly becoming a global public health emergency, a mission central to one Swiss biopharmaceutical company. Debiopharm’s Global Value and Access Senior Manager, Isabelle Petit, and Medical Director, Dr Jutta Amersdorffer, share how the company is helping in the fight against AMR.

The burden of antimicrobial resistance

“AMR is responsible for around one million direct deaths each year and associated with over four million more,”1 explains Petit. “Beyond this human toll, the economic impact could reach almost one trillion US dollars by 20501 if we fail to act.”

In addition, the difficulties in coding AMR as the main cause of death for patients who have multiple co-morbidities or the inconsistencies in coding method lead to an underestimation of the AMR-related

models help us to understand biology, but they’re not human. Organoids enable the growth of human adult tissue in the lab, effectively replicating its genetic and phenotypic characteristics to more accurately reflect the realities of human biology.”

Seeing tangible success across numerous therapeutic areas has validated the power of organoid technology, including oncology and cystic fibrosis. HUB Organoids is now focused on extending its services to the area of infectious diseases, to bridge the unmet need for patients who are notoriously affected by a lack of access to treatments.

“Researchers studying infections like RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) or rhinovirus have traditionally struggled to model human infection accurately in the lab,” Boj explains. “With organoids, we can reproduce the infection process in patient-derived tissue, observing real human immune responses and testing antiviral agents in a biologically relevant setting.”

Partnering for impact

The company’s recent acquisition by life science global leader, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt Germany, marks a major step forward. “Merging with a recognised global biopharmaceutical leader enhances the resources, regulatory expertise and infrastructure we can offer to biopharma researchers, enabling us to scale our impact and capabilities,” Boj adds. “This partnership will allow us to extend our services across new therapeutic areas, including antimicrobial resistance and infectious diseases.”

mortality and hospitalisation period and mask the real-world burden of AMR.2

Unmet need in bone and joint infections

One area of concern surrounds bone and joint infections, specifically those caused by bacteria, which have high morbidity and mortality rates.

“There have been no newly approved antibiotics for bone and joint infection in nearly 40 years,” says Dr Amersdorffer. “Patients often endure prolonged hospitalisation, and those with chronic infections may face amputation.”

The company is on a mission to change that, currently investigating the use of afabicin in a Phase 2 clinical trial for bone and joint infections.

Afabicin against AMR

Fulfilling all four WHO innovativeness criteria: new chemical class, new target, new mode of action and no crossresistance to other antibiotic classes, afabicin (Debio 1450) is a first-in-class

novel antibiotic that inhibits fatty acid synthesis in Staphylococci by targeting the Fabl enzyme.

“Afabicin has been designed to be highly specific,” explains Dr Amersdorffer. “It directly targets the source of infection, the Staphylococcus bacteria, without harming intestinal microbiota.” Afabicin’s narrow spectrum profile helps preserve the body’s healthy microbiome and reduce risk of further resistance, with early clinical data showing efficacy comparable to standard-of-care treatments.

“For Debiopharm, addressing antimicrobial resistance has always been a priority,” says Petit. “We recognised the urgent need for new antibiotics long before it became a mainstream concern, and that commitment has driven us to actively engage in this field and build strong in-house expertise.”

With the antibiotic market facing economic challenges, as the cost of development far outweighs its commercial return, it is key for companies like Debiopharm to collaborate with policy makers and industry to build consensus, define incentives to support antibiotic R&D and ensure that essential innovations like afabicin can be sustainably supported.

References: 1. WHO. (2023). Antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization. https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance 2. Mestrovic T, Robles Aguilar G, Swetschinski LR, et al. The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO European region in 2019: a cross-country systematic

Learn more about

HUB Organoid technology:

HUB Organoids is part of the Life Science Business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Merck operates as MilliporeSigma in US and Canada.

Paid for by Debiopharm

INTERVIEW WITH Sylvia Boj CSO, HUB Organoids

WRITTEN BY Dr Jutta Amersdorffer Medical Director (Consultant), Debiopharm

WRITTEN BY Isabelle Petit Global Value and Access Senior Manager, Debiopharm

WRITTEN BY Bethany Cooper

Without effective antibiotics, accelerated action on NCDs is at risk

A coordinated response to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) is essential to building healthier populations worldwide, and pull incentives for antibiotics are part of the solution.

AMR and NCDs represent two of the greatest threats to global health and development that we face. Coordinated political leadership at the United Nations, across G7 countries, and nationally can help ensure a robust, integrated health systems response.

AMR, infectious diseases and NCDs are connected

Treatment-resistant bacteria are already associated with nearly 5 million deaths each year and, without meaningful action, they could cumulatively contribute to 169 million deaths by 2050, resulting in almost USD 100 billion of additional annual healthcare costs from 2050 onwards.1

Effective antibiotics underpin virtually all facets of modern healthcare. Yet, according to WHO, one in six bacterial infections are now resistant to antibiotic treatments.

Many people living with NCDs, especially those undergoing cancer treatment, are more vulnerable to infection due to weakened immune systems and frequent hospital visits. Cancer patients are up to three times more likely to contract drugresistant infections, and infections are directly or indirectly linked to half of all cancer deaths.2

Pull incentives are essential to turning the tide

Over the years, WHO has underlined the scarcity of the clinical pipeline. Our research further shows that, without prompt action to incentivise antibiotic innovation, it will only get worse.

At its core, the pipeline issue is economic due to the necessity of restricting antibiotic use to preserve effectiveness. This creates a disconnect between the high costs of development and returns developers can achieve, discouraging investment. Smaller developers are hit particularly hard, and many suffer significant financial difficulties, despite achieving initial success.

With existing market dynamics insufficient to drive antibiotic innovation, additional economic incentives are needed. This requires so-called ‘pull’ incentives, designed to reward the successful development of new antibiotics and increase the solutions we have to respond to infectious diseases, including for those most at risk.

The pharmaceutical industry is committed to playing its part in transforming scientific progress into meaningful health outcomes. With the right pull incentives in place, innovation against AMR can be unlocked, to the benefit of patients everywhere.

References:

1. Naghavi, Mohsen et al., 2024. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet, Volume 404, Issue 10459, 1199 – 1226.

2. Nanayakkara, Amila K et al. 2021. Antibiotic resistance in the patient with cancer: Escalating challenges and paths forward. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians vol. 71,6 (2021): 488-504. doi:10.3322/caac.21697.

Harnessing bacteriophages in the fight against antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains one of the most pressing public health challenges of our time, claiming more than 35,000 lives each year in Europe alone.1

Beyond the human toll, its economic burden is staggering, costing the European Union an estimated €1.5 billion annually in healthcare expenses and productivity losses, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the OECD. Without urgent global action, AMR could cause up to 10 million deaths annually by 2050,2 threatening the very foundations of modern medicine.

Rethinking antibiotic incentives

Discussions around AMR rightly often focus on antibiotics, as reducing their unnecessary use remains essential. Awareness campaigns and responsible prescribing are crucial, but these must go hand in hand with the development of new antibiotics.

At the EU level, work is underway on new economic models, such as subscriptionbased payments or milestone rewards, which could help resolve the paradox in which the responsible, limited use of new antibiotics undermines investment incentives.

However, our focus should not rest solely on antibiotic incentives. An emerging ally in the fight against AMR is bacteriophages, or phages. These naturally occurring viruses specifically target bacteria, offering a promising and largely untapped medical countermeasure. Alongside incentivising R&D in antibiotics, a comprehensive approach to phages is needed, recognising their applications and potential to combat AMR across multiple sectors.

Potential of phages in AMR response

In healthcare, phages can complement or even replace antibiotics, particularly against resistant infections such as MRSA, sepsis or chronic wounds. In veterinary medicine, they provide similar benefits for treating bacterial infections in animals. In diagnostics, engineered phages can rapidly and accurately identify specific bacteria.

Beyond medicine, phages can enhance food safety by reducing contamination from pathogens like listeria, Salmonella and E. coli, while also improving environmental health through targeted wastewater treatment.

The potential of phages is immense, but realising it requires a robust regulatory framework. Tackling AMR effectively demands a multi-pronged strategy, and phages can play a crucial role in Europe’s response to this global health challenge.

References:

1. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2022. Assessing the health burden of infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU/EEA.

2. Naghavi, Mohsen et al. 2024. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet, Volume 404, Issue 10549, 1199–1226.

Using vaccines to slow the global AMR crisis

Vaccines don’t just prevent disease; they also slow the rise of antimicrobial resistance. As immunisation rates fall, experts warn we risk losing one of medicine’s best defences.

Vaccines and antibiotics have revolutionised public health. The introduction of the Expanded Program on Immunisation in the 1970s led to remarkable reductions in child mortality rates.1 Similarly, the widespread clinical use of antibiotics starting in the 1940s drastically reduced infection-related deaths and paved the way for progress in modern medicine.2 Yet, amid these accomplishments, there is a growing sense of complacency. Immunisation rates are declining, while we rely heavily on antibiotics that were discovered decades ago.3

Antibiotic resistance undermines modern medicine Antibiotics are losing their effectiveness due to the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria,4 a phenomenon known as antimicrobial resistance, or AMR. For many patients, AMR makes infections harder to treat, often necessitating the use of more sophisticated and costly antibiotics. Unfortunately, much of the public does not know that AMR can manifest subtly, lurking beneath other issues, such as post-surgical complications, prolonged hospital stays or interrupted cancer treatment. Currently, over 1 million lives are lost annually due to bacterial AMR, with countless more deaths linked to conditions worsened by these resistant bacteria.5