ARC3024

The Politics of Space: Infrastructure Development and Ideological Power in Postcolonial Cities

Case study- Journey from Calcutta to Kolkata

Deedhiti Mukherjee 40372347

"In Kolkata, infrastructure is more than structure — it is a weapon of power, a canvas of resistance, and a blueprint for future dreams." (Gupta 2023, p. 475; Sur 2017, p. 602–604)

Postcolonial cities’ spatial reconfiguration and layout often reflect an in-depth ideological and political transformation, shaping their identity and power dynamics. Infrastructure development is seen as a reflection of resilient administration. It has historically been utilised to impose dominance psychologically and literally over the urban fabric of a city, and soon before they realise, it begins to shape their daily lives.

Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta, serves as a powerful case study of how infrastructural decisions have been used as a physical and psychological tool of both colonial power and post-independence government to form an identity.(Gupta 2023,p. 475 )

Calcutta, once serving as the capital of British India, is a site of imperial ambition, incorporated with a spatial division deliberately designed to reinforce racial and social hierarchies.(Gupta 2023,p. 469–475).

Hence, this essay explores the course of Kolkata’s transformation of urban fabric, beginning with the colonial influence on the spatial order and social hierarchy, followed by its post-independence struggle to reclaim its identity, and finally, the implications of neoliberal economic policies in reshaping its urban fabric. (Gupta 2023, IJSSER, p. 477–478).

While examining the layers of transformation in Kolkata’s built environment, it will become evident how infrastructure and public spaces continue to function as spaces where histories get renegotiated, power is contested, and visions for the future are formed. (Sur 2017, The Blue Urban, p.602–604)

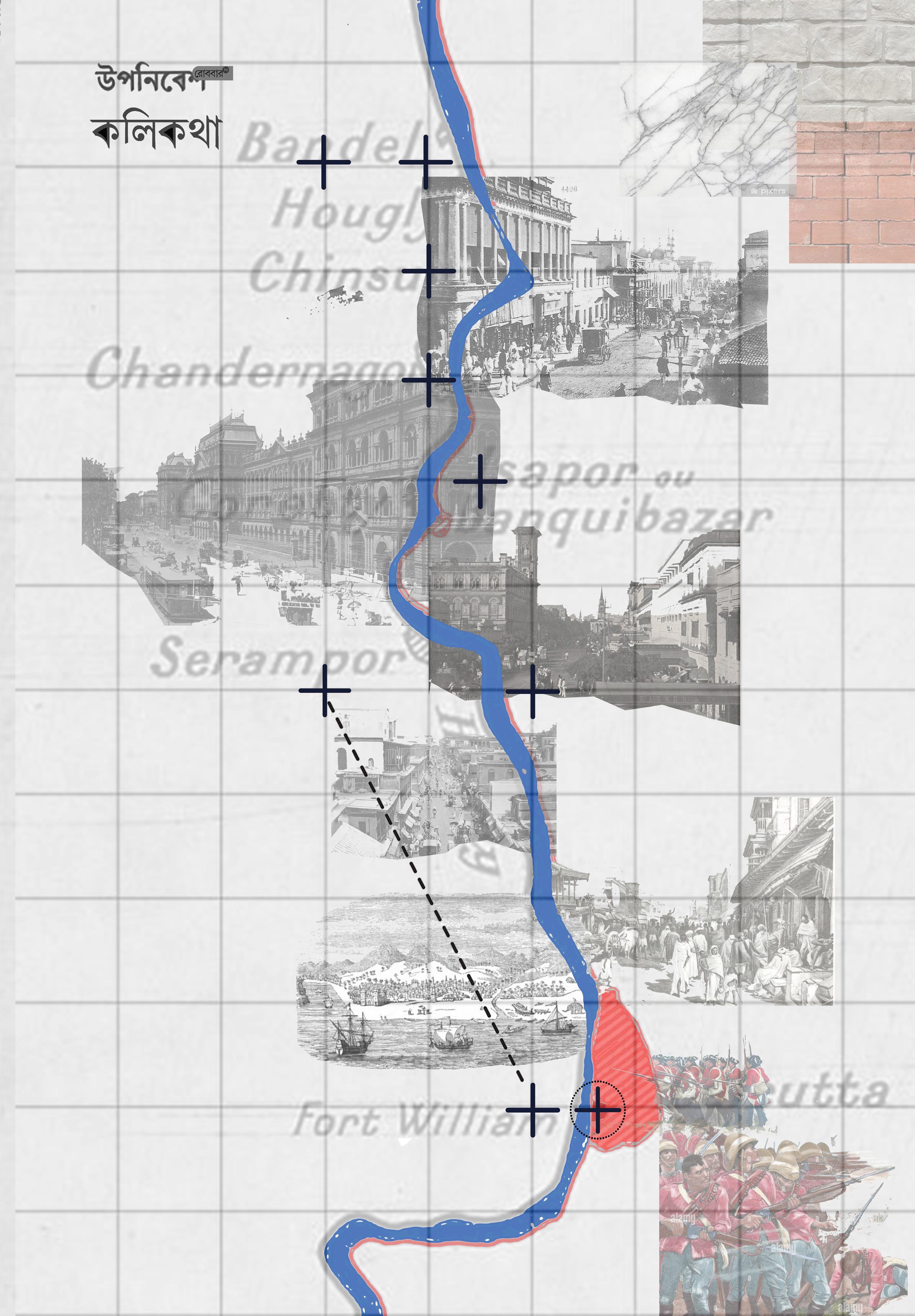

Calcutta, now known as Kolkata, encountered several complexities of urban development between the period of 1772 and 1911. These transformations reflected a complex interplay of colonial influences, shifts in the demographics and how the city’s spatial organization was. It has been widely acknowledged that British colonialism had a great impact on the shaping of city trajectory. While it’s true, it is also essential to remember that Mughal consolidation, Maratha incursions as well as European colonial invasion, began before the British dominance, reflecting the notable impact of Portuguese and French establishments.(Gupta, 2023 ,p.15)The city’s morphology underwent a lot of transformations during the imperialistic rule.

Calcutta was still characterized by its humble beginnings, for example, the mud-built fortifications and provisional defense mechanisms, like the Maratha ditch dug in 1742 in order to guard against the frequent Martha invasions. Over time, these rudimentary boundaries became the core reason for further expansion and structured urban development of the city. Later around 1799, the Martha ditch was filled in and transformed into the circular road, which today we know as Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Road (AJC Bose Road).(Mukherjee, (2019),p.450).This newfound freeway helped to fundamentally mark the city’s eastern edge and also opened the window for its outward expansion, facilitating a more connected and organized landscape.

In the late 18th century, during the transformative years of British rule, the East India Company inherited a system of agrarian taxation influenced by the Mughal Empire. There had been significant efforts to standardise this system, which led to the introduction of the Permanent Settlement At in 1793. This was arily aimed at creating a predictable revenue system by fixing the amount of land and taxes permanently. However, this rudimentary approach failed to acknowledge the dynamic nature of the rapidly evolving urban landscape, often resulting in debates and challenges regarding the assessment and collection of land taxes. (Roy, 2023, p.15-18)

A City where every brick and boulevard echoes the struggle for social and political control

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Calcutta saw a dramatic surge in its population, substantially driven by migrants seeking economic opportunities. The influx in population led to the city’s expansion beyond its boundaries, which led to reshaping its urbanscape and promoting interactions among the mosaic of new communities starting to coexist. While there had never been any play of explicit policies of racial and religious segregation, unintentionally people have always practiced it among their communities, hence the socioeconomic factors and colonial preferences resulted in forming distinct European and native enclaves.(Dhar,p.20)

Amidst these divisions, figures like Dwarkanath Tagore emerged as pivotal in bridging communal divides. Beyond his entrepreneurial pursuits, Tagore was a noted philanthropist and civic leader, contributing to various social and cultural initiatives that fostered spaces of interaction and cultural synthesis between European and Indian communities.

As the years went by and British colonial rule steadily extended its reach, tightening its grip on the city, Calcutta’s contradictory colonial landscape continued to evolve. The British colonial administration attempted a calculated move towards reshaping the urban landscape by asserting dominance, reinforcing racial hierarchies and promoting an efficient government. The city’s transformation from a “city of huts” to a “ city of palaces” was not only about the aesthetics but it was to impose a sense of British authority. The existing blend of Mughal and vernacular architecture was encountered in the introduction of neoclassical architecture, expensive levies and specific designated administrative zones, highlighting this as the prominent metaphor of imperial control.

One key aspect of this transforming cityscape was a visible division between the European-dominated ‘White Town’ and the congested Indigenous neighbourhoods often known as the ‘Black Town. The white town was primarily inhabited by British officials and European merchants. It was a conscientiously planned domain that often could be seen having grand colonial edifices and broad avenues, illustrating imagery of beautification. The Black town was predominantly home to the native/local population. It had been often characterized by its congested planned spaces, narrow lanes and inadequate infrastructure. It was a deliberate attempt at the spatial division which asserted colonial agenda of racial and social classification, ensuring an explicit distinction between the European elite and the native communities. (Mukherjee 2012, p305-310) Considering the previous rudimentary application of policies, it becomes prominent that a greater agenda was at play. Beyond the physical segregation, colonial urban policies attempted to reshape calcutta into administrative as weel as symbolic nucleus of British rule. It primarily aimed to embed very European/ western conception/ ideals of progress and civilization into the core fabric of the city and by doing so, it sought to bring a powerful psychological play of power and dominance over both space and society. For example, structures like the writers building and general post office in Kolkata reflected the imperial grandeur, projecting a sense of power and stability of British rule.

What about the privileged for whom city is not a battleground for survival but a playground for fun?

Displaced residents were often relocated to peripheral areas with inadequate infrastructure, exacerbating social and economic disparities Calcutta has been through gentrification even before it became a term. (Pramanick 2025 ,p.22). While these infrastructural developments were often legitimized as an attempt to create a “ healthier and more beautiful city”, it has often become the reason behind the displacement of the native communities from their own space and more prioritizations has been given to the European interests. Nonetheless, the structural imposition by colonial urban planning, unintentionally planted the seeds of resistance and adaptation among the native population. The educated middle class, often termed as “ Bengali bhadrolok”, embarked on appropriating colonial architectural styles to acclaim their own newfound identity.(Poromesh. 2016,p50-55).

For example, the areas of north Calcutta, primarily inhabited by the local communities, saw an emersion of Indo-European styled mansions. It had blended the elements of western architecture with vernacular traditions. With this adaptation and integration, there has been a reflection of the “Bhadraloks” attempt to navigate through the cultural dualities which have been slowly becoming their reality. (Mukherjee, (2019, p.455)

Moreover, the bhadralok’s engagement with colonial spaces extended beyond architecture. Their increasing presence in areas like the Maidan, a vast urban park initially dominated by the British, signified a subtle yet powerful assertion of agency.

By adopting European customs around park use and public leisure, the bhadralok redefined these spaces, embedding them with new cultural meanings. In essence, while colonial urban policies in Calcutta aimed to impose European ideals and structures, they also set the stage for complex interactions between the colonisers and the colonised. The bhadralok’s appropriation and reinterpretation of colonial architecture and spaces highlight the dynamic processes through which native communities navigated, resisted, and reshaped the urban fabric imposed upon them.(Gupta, 2023, p.18)

Post-Independence Struggles: Decolonisation and the Search for Identity

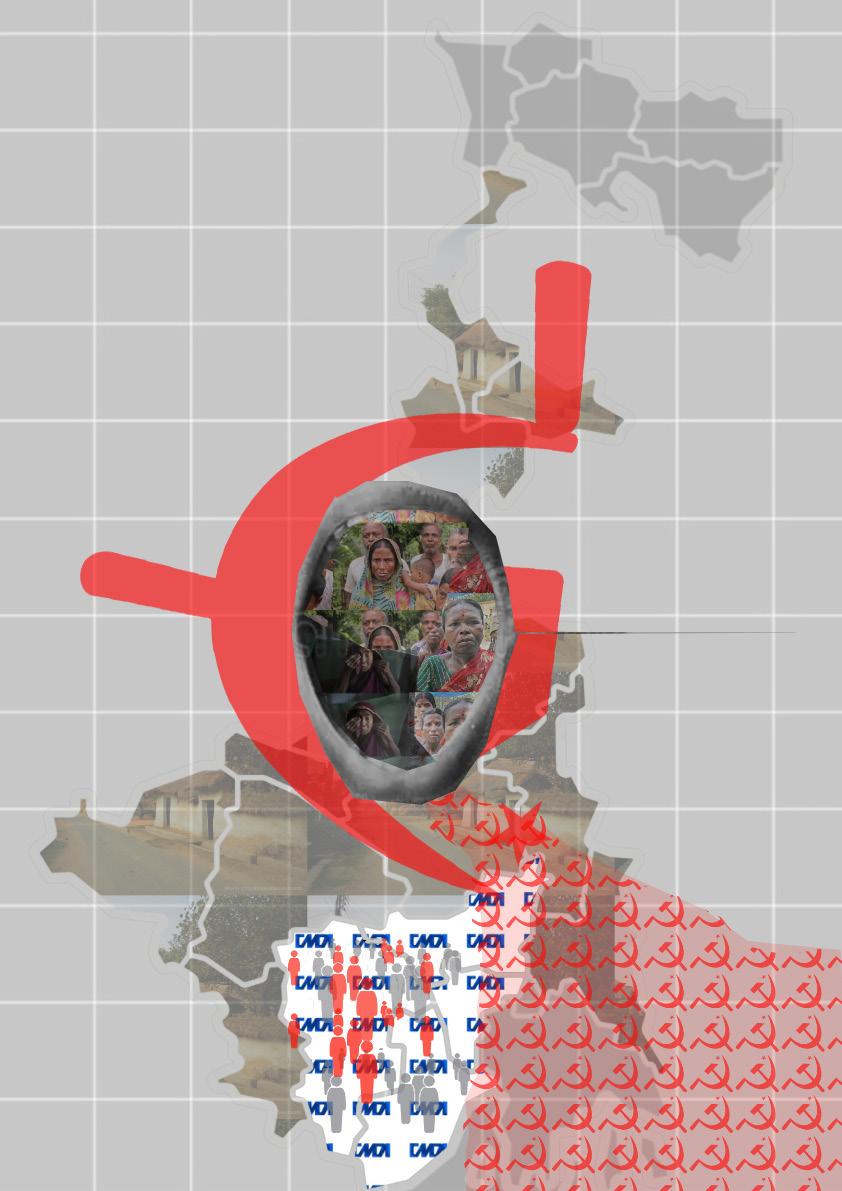

The fear of communism led to the formation of the Kolkata Metropolitan Authority, yet the grassroots infiltration by the Communist Party of India and its allies showcased their deep-rooted influence over the city’s socio-political fabric.

Fear in the eyes of people in Rural India

After the independence of India in 1947, Kolkata set off on a transformative journey to discover its newfound identity, both symbolically and physically. A new trend was initiated with the renaming of streets and government institutions to reclaim the city’s heritage from its colonial past. From 1976 to 2007, approximately 168 streets and parks were renamed, and it witnessed a significant peak was witnessed in 1982 when 27 streets were renamed within a year. The most prominent examples are Amherst Street becoming Raja Rammohun Roy Sarani, and Dalhousie

Square was renamed as Binoy Badal Dinesh Bagh. Nevertheless, even after prolonged efforts, these symbolic gestures could not dismantle the grip of the colonial framework. Many colonial-era names still persist in everyday usage, reflecting the deep-rooted nature of these identifiers in the city’s collective memory. (Sengupta, 2021, pp. 40–42)

As a result, even after decades of independence, it continued to influence the city’s governance and spatial organisation.

Kolkata, post-independence, witnessed several significant socio-political turbulences, notably the influx of refugees/immigrants following the partition of Bengal. Estimates suggest that by 1951, approximately 1.17 million Bengali Hindus had migrated from East Pakistan to West Bengal, with a substantial number settling in Kolkata. This massive migration began to alter the city’s demographics, leading to the rapid expansion of informal settlements, locally known as “jabar-dakhal” colonies, as refugees occupied vacant lands to establish makeshift homes around several parts of

the city. (Nakatani, 2000, p. 80) The newly independent government and head of the state faced a dual challenge to manage between the recent urban growth and the striving to establish a distinct architectural identity that reflects the aspirations of the newborn nation. It has been comparatively seen in cities like Chandigarh, which adopted the modern urban planning and style of modernist architecture as a break from the colonial traditions. Meanwhile, Kolkata struggled to characterise its postcolonial aesthetics and urban framework. Consequently, Kolkata’s landscape remained dominated by colonial structures, such as the Victoria Memorial Hall. (Banerjee,2022,p.10)This shadow of the colonial past emphasised the difficulties Kolkata had been facing to redefine its urban architectural identity, and all amidst the challenges of the 0-partition refugee rehabilitation and a quest for a new national ethos.

During the 1960s and later in 70s, Kolkata witnessed the rise of leftist political power in West Bengal, which significantly influenced the urban policies. The communist party of India (Marxist) attempted to coordinate urban development with their socialist ideologies, advocating for the protection of the rights of the working-class sector and invoking grassroots movements. While this period saw a concerning increase in state intervention in urban planning and expansion of the urban framework, it also led to bureaucratic inefficiencies and a stagnation in the workflow. Infrastructure projects were often delayed, and large-scale urban redevelopment proposals were sidelined in favour certain political considerations.

For instance, the Calcutta Urban Development Project (CUDP), initiated in the 1970s with World Bank assistance, aimed to improve the city’s infrastructure but encountered challenges in implementation due to administrative hurdles and political dynamics. (Unger, 2015, pp. 132–134) .There was a clear dominance of a single political party and its hierarchical segregation and despite several attempts of democratic decentralisation, it was the reality that centralized decision making often got ovelooked the needs and priorities of the locals. (Unger, 2015, p. 136)

Although, despite facing several challenges while searching for its new identity, Kolkata made efforts to reclaim its architectural uniqueness. There had been attempts to incorporate indigenous elements into certain public spaces, for example, institutions like Rabindra Sadan embraced red brick facades and local motifs as a symbolic gesture to get past their colonial bygone days. (Banerji, 2014, pp. 104–106).However, these efforts became Irrelevant and short-lived, as the city fell under the grasp of economic decline and political instability. The lack of comprehensive urban planning throughout the years clearly implied that Kolkata continues to struggle with infrastructural decay, overcrowding and inadequate public service spaces. (Sanyal, 2013, p. 42)

Neoliberalization and the Changing Urban Aesthetic

The economic liberalisation around the 1990s saw a remarkable shift in Kolkata’s urban trajectory, onsetting a new period of neoliberal urbanism. As India had been heading towards the era of globalisation and overseas investment, urban policies by the government began to favour privatisation and real estate development. The Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority, also known as KMDA, performed a crucial role in accelerating the expansion of private townships, IT parks and gated communities. For example, regions such as Salt Lake, new town action areas and Rajarhat surfaced as optimal sites to execute the policy of urban expansion, attracting Multinational corporations and a huge sector of upper middle-class demography. (Sawyer et al. (2021, pp. 1307–1310).

During this period, the city has encountered a massive transformation in its aesthetics and started inclining towards a homogenised and global urban landscape. The consequences started to appear in the form of glass-clad office buildings, high-rise apartments and huge shopping complexes. Soon, they began to dominate the skyline, resulting in replacing the historical infrastructures that once defined Kolkata’s architectural identity and old charms.(Satpati and Haldar 2020 p.1832).Although the new urban fabric began to prioritise efficiency and economic growth, it was often at the expense of ecological sustainability and social/societal integrity. Examples of this practice have been seen, such as the wetlands in New Town and Salt Lake, which had always functioned as the city’s natural drainage system, getting repurposed for commercial expansions, resulting in environmental degradation. (Satpati and Haldar 2020 pp.1833–1834).

Simultaneously, the city’s economy encountered a surge in marginalisation among different demographics. Initiatives such as Operation Sunshine, which aimed to remove the rickshaw (local form of transportation operated by a person) hawkers and street/local shops from major streets and commercial sectors, exposed the attempt of the government to display Kolkata as a modern metropolis. (Chatterji and Roy 2016 p.4)

These actions caused negligence towards the livelihoods of thousands of working-class families, who are often regarded as the backbone of the formation of the city’s economy. As a result, these efforts of modernisation saw resistance from labour unions and activists who considered them an attempt to attack the working-class communities. (Chatterji and Roy 2016 p.5)

Kolkata’s neoliberal urban policies reflected a trend in several other postcolonial cities, where economic requirements often dominated the infrastructural decisions, whereas in reality, it should be the other way round. While new investment brought economic opportunities, it also intensified the already existing spatial disparity, displacing the lower-income communities further down, resulting in the fragmentation of the city’s fabric.(Sawyer et al.2021 pp. 1311–1313) The brewing tension between the increasing sense of modernisation and preservation of the city’s heritage became a common theme in the metropolitan dialogue. In response, a new generation of entrepreneurs and conservationists has emerged, aiming to preserve and repurpose the city’s heritage structures. Initiatives like the Calcutta Architectural Legacies campaign have advocated for the protection of historic buildings, transforming them into contemporary spaces that retain their historical significance. Consequently, a burning question came up among scholars and activists that whose interests were being prioritised in the name of these developmental projects.

The city has seen its fair share of grassroots movements, challenges presented by civil society organisations and the emergence of advocacy regarding inclusive urban policies. For instance, street vendors and the local transportation community have organised several unions to resist their eviction and demand their rights. Established in 1971, this union has been instrumental in organising vendors to resist evictions and demand recognition of their livelihoods. However, recent surveys indicate that a significant portion of these vendors operate without legal sanctions. A survey by the Town Vending Committee found that 80% of hawkers at the Grand Arcade were considered illegal by municipal standards. (Chatterji and Roy 2016, p.5 )This situation has led to frequent clashes between vendors and authorities, often resulting in the demolition of stalls without adequate compensation or rehabilitation. In recent years, Kolkata has been experiencing a growing awareness regarding the need to find a balance between radical development, environmental sustainability and social equity. However, the implementation of approaches such as inclusive planning remains nonexistent, and the ambition to fabricate an anti-discriminatory and sustainable Kolkata remains just a vision. (Satpati and Haldar (2020) p. 1835). As it continues to evolve, the voices of its diverse communities remain crucial in shaping a city that honours its rich heritage while embracing inclusive growth. This entails not only recognising the rights and contributions of informal sector workers and marginalised communities but also ensuring their active participation in the urban planning process.

Conclusion In Kolkata, a space is never a space. It is built upon layers of history, politics, culture and emotion. A city where every building and lane seems to carry the weight of the past. From colonial segregation to finding temporary challenges of post-independent identity and today’s continual push towards global modernity, the city has always been in conversation and conflict with itself. What you see on the streets is not just an infrastructure but an ideology in brick and concrete. Colonial mansions still stand beside crumbling worker tenements and sleek flyovers slice through neighbourhoods that have adapted and endured. Kolkata doesn’t unfold like a planned narrative. And now, as the city moves forward, the biggest questions aren’t just about traffic or GDP. They’re about fairness. Who gets to decide what the future looks like? Who gets pushed out in the name of progress? At the heart of it all is a deeper question of spatial justice for forming a city that belongs to everyone and for coexisting. A truly postcolonial Kolkata can’t come from wiping the slate clean or copying some other city’s skyline. It must come from within space that listens to its many voices, embraces its contradictions, and allows its complexities to breathe.

1. Basu, Sudipto. 2015. “Spatial Imagination and Development in Colonial Calcutta, C. 1850–1900.” History and Sociology of South Asia 10 (1): 35–52.

2. “HAWKERS and the URBAN INFORMAL SECTOR: A STUDY of STREET VENDING in SEVEN CITIES Prepared by Sharit K. Bhowmik for National Alliance of Street Vendors of India (NASVI).” n.d. Accessed April 27, 2025.

3. Sawyer, Lindsay, Christian Schmid, Monika Streule, and Pascal Kallenberger. 2021. “Bypass Urbanism: Re-Ordering Center-Periphery Relations in Kolkata, Lagos and Mexico City.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 53

4. Sengupta, Anwesha. 2021. “Bengal Partition Refugees at Sealdah Railway Station, 1950–60.” South Asia Research 42 (1): 40–55.

5. Nakatani, Tetsuya. 2000. “Away from Home : The Movement and Settlement of Refugees from East Pakistan in West Bengal, India” 2000 (12): 73–109.

6. Banerjee, M. (2022). The Partition of India, Bengali ‘New Jews,’ and Refugee Democracy: Transnational Horizons of Indian Refugee Political Discourse. Itinerario, pp.1–21.

7. Sanyal, Romola. 2013. “Hindu Space: Urban Dislocations in Post-Partition Calcutta.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39 (1): 38–49.

8. Satpati, Lakshminarayan, and Anwesha Haldar. 2020. “Neoliberal Urban Sustainability in Old Kolkata, India: Case Studies of Contested Developments.” Regional Science Policy & Practice 13 (6): 1825–41.

9. Mukherjee, Mala. 2012. “URBAN GROWTH and SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION of KOLKATA METROPOLIS: A CONTINUATION of COLONIAL LEGACY,” January.

10. Chatterji, Tathagata, and Souvanic Roy. 2016. “From Margin to Mainstream: Informal Street Vendors and Local Politics in Kolkata, India.” L’Espace Politique, no. 29 (September).

11. Kumar, M. Satish. 2007. “Representing Calcutta: Modernity, Nationalism, and the Colonial Uncanny , By Swati Chattopadhyay.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 28 (2): 240–42.

12. Gupta, Devarupa. 2023. “EVOLUTION of an INDIAN CITY: FROM CALCUTTA to KOLKATA.” International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research 08 (03).

13. Mukherjee, M. (2019). View of a city: an immersive history of Kolkata via camera-eye. South Asian History and Culture, 10(4), pp.443–469.

14. Dhar, Diksha. n.d. “International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities (IJISSH) Commemorating the Bhadralok: Exploring Culture as Governance in the Context of West Bengal.” Accessed September 26, 2024.

15. subham pramanick. 2025. “Kolkata – the Colonial City_Subham.” Scribd. 2025. https://www.scribd.com/document/618871326/ Kolkata-The-Colonial-City-Subham.

16. Acharya, Poromesh. 2016. “Bengali ‘Bhadralok’ and Educational Development in 19th Century Bengal,” January.

17. Roy, Tirthankar. 2023. “The Permanent Settlement and the Emergence of a British State in Late-Eighteenth-Century India.” https:// www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/WorkingPapers/Economic-History/2023/WP355.pdf.

18. Mukherjee, Madhuja. 2025. “Cinema and Its Spectral Returns: The Single-Screen Viewer at the Site of Artistic Re-Imagination.” South Asian History and Culture, April, 1–22. doi:10.1080/19472498.2025.2488645.

Witnessed a Battle, Battle of Alinagar (1956), between Siraz-Ud-Daulah and East India Company, Which Eventually Lead To.” Linkedin.com. June 14, 2019. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/city-palette-political-advertisement-case-kolkata-diya-banerjee/.

FIGURES BIBLOGRAPHY

FIG 1-9

Website:

“Bangla o Bangali.” Goodreads, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/bangla-o-bangali.

Article:

“Calcutta and the British Empire.” Victorian Web, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://victorianweb.org/history/empire/india/calcutta/p3.html.

Postcard:

“Writers’ Building, Calcutta.” Paper Jewels, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.paperjewels.org/postcard/view-writers-building-calcutta.

Image:

“British Imperialism in Sudan, Africa.” Bridgeman Images, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/noartistknown/british-imperialism-sudan-africa-english-army-attacking/nomedium/asset/562256.

Image:

“P615 Calcutta in the 17th Century.” Creazilla, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://creazilla.com/media/traditional-art/7067948/p615-calcutta-in-the-17th-century.

Article:

“Photographs from Kolkata: These Colonial Structures Helped Calcutta Rule Over the Subcontinent.” Indian Express, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://indianexpress.com/article/research/photographs-from-kolkata-these-colonial-structures-helped-calcutta-rule-over-the-subcontinent/.

Artwork:

“Indian Poor - Drawings.” Fine Art America, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://fineartamerica.com/art/drawings/indian+poor.

Image:

“Lake Superior by Bellin, 1744.” Boudewijn Huijgens Archive, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://boudewijnhuijgens.getarchive.net/amp/media/lake-superior-by-bellin-1744-888fef.

Product Page:

“Cut Stone Products.” Nitterhouse Masonry, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.nitterhousemasonry.com/our-products/cutstone/.

FIG 10-25

Website:

“5 Days Trip for.” GenSpark AI, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.genspark.ai/spark/5-days-trip-for/d4115a56-030e-4ec0-9d26-4195a1fe8580.

Story:

“The Road to Revolution.” Sutori, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.sutori.com/en/story/the-road-to-revolution--TAGdYdF4zPBipb3c6mepGjx2.

Article:

“Politicized Judiciary Sentences Yemenis to Death Without Due Process.” Mwatana, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.mwatana.org/posts-en/politicized-judiciary-sentences-yemenis-to-death-without-due-process.

Blog Post:

“Why Did UK Midwives Promote Normal Birth? Medical Imperialism.” Skeptical OB, March 2022. https://www.skepticalob.com/2022/03/why-did-uk-midwives-promote-normal-birth-medical-imperialism.html.

Article:

“Classical Culture in British India I.” Antigone Journal, February 2023. https://antigonejournal.com/2023/02/classical-culture-british-india-i/.

Website:

“United Kingdom.” U.S. Department of State, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.state.gov/countries-areas/united-kingdom/uk-lgflag/.

Article:

“Strolling Through Kolkata’s Colonial Past.” EU Telegram, January 21, 2018. https://eu.telegram.com/story/entertainment/fashion/2018/01/21/strolling-through-kolkatas-colonial-past/16039712007/.

Image:

“Historical Reenactment of British Riflemen at the Battle of Waterloo, 1815.” Bridgeman Images, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/camillo-balossini/historical-reenactment-british-riflemen-battle-of-waterloo-1815-napoleonic-wars-19th-century-photo/photograph/asset/3067352. image:

“Mukherjee,Deedhiti.Victoria Memorial Hall,2021.

Blog Post:

“The Eternal Evolution of Saree Blouses.” Chidiyaa, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://chidiyaa.com/blogs/indian-sarees/the-eternal-evolution-of-saree-blouses.

Wikipedia Article:

“Sudhira Sundari Devi.” Wikipedia, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sudhira_Sundari_Devi. Wikipedia Article:

“Indo-Saracenic Architecture.” Wikipedia, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Saracenic_architecture. Website:

“Posh Areas in Kolkata.” MagicBricks, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.magicbricks.com/blog/posh-areas-in-kolkata/121121.html.

Image Resource:

“Université de Madras, Chennai, India.” Adobe Stock, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://stock.adobe.com/uk/images/universite-de-madras-chennai-inde/262016114. Tumblr Post:

“The Sari in the 1870s.” Vintage Indian Clothing on Tumblr, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.tumblr.com/vintageindianclothing/79399408884/the-sari-1870s-as-is-well-known-the-innovation. Online Art Store:

“Babu - Home Maker.” Gallery Splash, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.galleriesplash.com/product/914/Babu---home-maker-.

FIG26-37

News Article:

“Hindus and Muslims Living Through the Legacy of Partition.” The Guardian, August 2, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/02/wounds-have-never-healed-living-through-terror-partition-india-pakistan-1947. News Article:

“Stone-Pelting to Vandalism: Violence Mars Ram Navami Celebrations in Various Parts of the Country.” Deccan Herald, April 2023. https://www.deccanherald.com/india/stone-pelting-to-vandalism-violence-mars-ram-navami-celebrationsin-various-parts-of-country-1205074.html.

Editorial Article:

“Parliament, Vidhimandal Politics: Leader Talking, Comment Writing.” Esakal, 2023. https://www.esakal.com/sampadakiya/editorial-articles/editorial-article-writes-parliament-vidhimandal-politics-leader-talking-comment-sanjay-raut-eknath-shinde-devendra-fadnavis-pjp78.

Image Resource:

“Writers’ Building, Kolkata.” Wikimedia Commons, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Writers’_Building_6.jpg.

Image Search:

“Communist Party.” Shutterstock, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.shutterstock.com/search/communist-party.

Blog Post: “Why Is South Calcutta Losing Its Buildings?” Double Dolphin, July 2015. http://double-dolphin.blogspot.com/2015/07/why-is-south-calcutta-losing-its-buildings.html.

Image Resource:

“Aerial People Crowd Background.” Adobe Stock, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://stock.adobe.com/uk/images/aerial-people-crowd-background/220297341. Art Resource:

“Decadence Photographs.” Fine Art America, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://fineartamerica.com/art/photographs/decadence?page=2.

Website Article:

“What Is AI Networking?” Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.hpe.com/uk/en/what-is/ai-networking.html. Image Resource:

“Crosswalk Overhead.” iStockphoto, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.istockphoto.com/photos/crosswalk-overhead.

News Article:

“Sujit Bose in the News.” The Statesman, Accessed December 12, 2024. https://www.thestatesman.com/tag/sujit-bose.