NZ Zines

Bryce Galloway Punk to Present

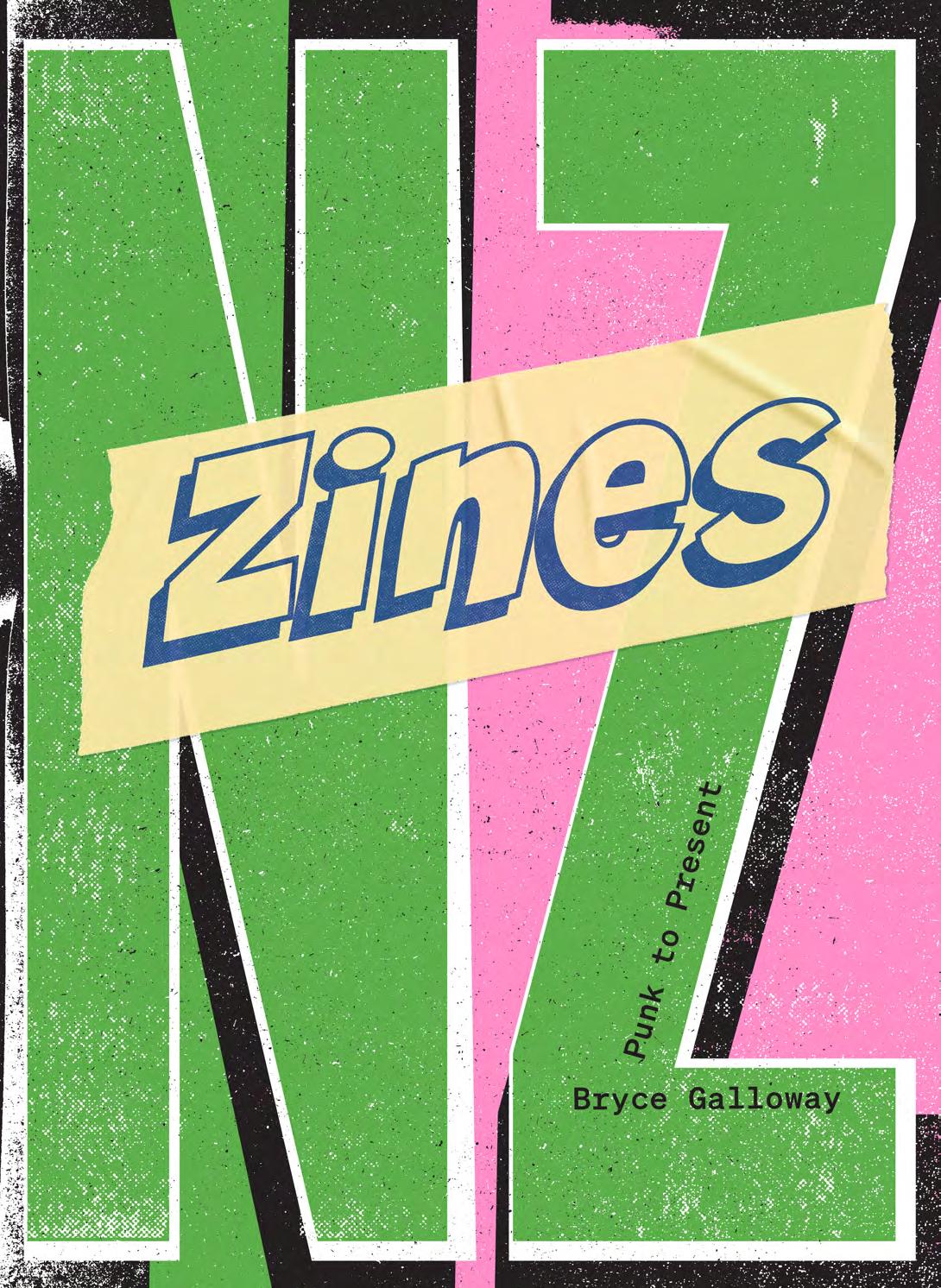

1. Garbage, edited by Adam Hyde, A4, 1990s. Kirikiriroa Hamilton.

2. Philosoflygirl #1, Coco Solid aka Jessica Hansell, 170 x 230mm, 2011. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

Intro

Almost every mainstream media article you’re likely to read about zines in Aotearoa asks, and then attempts to answer, the question ‘What’s a zine?’, as if every article is the very first to be written on the subject. This despite there being 12 zine festivals (or zinefests) in Aotearoa at the time of writing, despite numerous library collections, despite the many zine projects now in primary through to tertiary-level classrooms, despite the thousands of titles and millions of artefacts. This book hopes to go well beyond ‘What’s a zine?’ to investigate the contexts, motivations, processes, tools, distribution strategies and highs and lows of zine-making in Aotearoa since punk rock.

The first Aotearoa punk zines popped up in the 1980s, made by zinesters using professional printers, Gestetners1 and the new xerographic (photocopy) technology that was becoming more common. The word ‘fanzine’ was coined in the United States in 1940 to describe the amateurishly produced fan magazines being shared among science fiction fans. Like sci-fi fans, punk-rock zinesters were obsessives, but beyond that there may not be too many similarities in their creative output apart from the whiff of amateurism and their use of accessible printing technologies. Why start with punk? The politics of punk still informs the Aotearoa zine scene to a greater or lesser degree, depending on the region, and — full disclosure — it’s this author’s bias. The subculture not only promoted a do-it-yourself ethos across music, fashion and zines, it also married this with a challenging love of the abject. Audiences were invited to become creators; you didn’t even need to work through the bum notes, poor construction and spelling mistakes before going public. Non-musicians and amateurs picked up guitars, playing original songs at parties, pubs and community halls. Attitude and ideas prevailed over musicianship. The idea of wooing the public by seamlessly playing covers in a pub before wowing them with a couple of originals suddenly seemed stupid and safe. It took a little longer for zines to follow the music, but there would have been little in the way of inspiration from overseas zine ephemera compared to the number of punk records finding their way to these shores.

When zines did arrive, attitude and ideas prevailed there as well. A zine-maker might play writer, illustrator, photographer and designer, without training or prior experience in any of those things. Zinesters learned on the job, a job that no one was paying them to do. With punk music being actively ignored by the mainstream media, punk zines attempted to fill the void as zinesters reviewed gigs, record or cassette releases by a favourite new band, or conducted interviews. The politics in the music then became the politics outside it, as zinesters took it upon themselves to editorialise on matters of government and society, taking a right of reply that had never been offered to them. A grassroots national network in punk zines became the only way to find out about local punk music and culture. Zines helped young punks build an

identity that ran counter to the conservatism of their parents, their government and society at large.

Those early sci-fi self-publishers were fans of a literary genre, just as punk-rock zinesters were fans of a type of music (genre or attitude?). But the ‘fan’ tag was never going to weather punk rock, with its manifesto of bands and audience existing on an equal footing — sometimes quite literally, with there being no stage. ‘Anti-fanzine’ was even stamped across the cover of the mid-eighties Ōtepoti Dunedin zine PMT in acknowledgement of these etymological tensions. And so it was that the fanzine became a ‘zine’, opening up to accommodate all forms of amateur publishing: comics, collage, poetry, fiction . . . you name it.

Fast-forward, and a visit to your local zinefest will impress upon you not just a diversity of content, but also the diversity of gender, sexuality, class, age and neurodiversity of the zine-makers and zine-readers. (Ethnic diversity is improving but has been the harder battle.) Punk’s ‘death to disco’ mantra inadvertently raised a barrier along ethnic lines, when all it really wanted was to fight the corporatisation of music. Ever since, anything deemed ‘indie’ has had to actively try to shake off this historical baggage. In addition, the skinhead thing looked to many outsiders like evidence of punk’s racism, when inside the scene anarcho-punks and skins were at war over that very issue.2

The drugs took their toll, that and other aspects of the rock ’n’ roll life. The time is right for an oral history of this kind before anyone else expires. Each of the ageing punks I interviewed asked who else I’d spoken to, and on several occasions a surprised ‘They’re still alive!?’ bounced back. But that was not the catalyst for this history being an oral history. That decision points to the motivations of punks and zinesters, for at heart both are amateurs suspicious of any so-called experts. The all-comers community that amateurism invites hates the idea of the distant expert canonising a singular story. The zine voice is subjective and plural, so my job has been to gather together some of these voices and offer them up to you (after extracting several thousand ‘ums’ and ‘ahs’, ‘y’knows’ and ‘kind-ofs’).

4. Every Secret Thing #10 back cover, Robert Scott, A4, 1985. Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Bios

in order of appearance ...

Dave White

Dave White has long been singer/ guitarist in the band Lung. White was instrumental in setting up both The Stomach and Yellow Bike Records in Te Papaioea Palmerston North. He picked up Valve zine after it was dropped by Massey University student radio, producing several additional issues until his move to Whakatū Nelson in the late 1990s. The first so named ‘zinefest’ in Aotearoa was the International Zinefest (1997), which White organised in his role as director of the Nelson Community Arts Centre. It opened with a performance by Fugazi.

Paul Luker

As a then printer’s apprentice, Paul Luker is credited with starting New Zealand’s first punk zine, Empty Heads, in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in 1980. Luker had already selfpublished chapbooks of his own work and that of fellow poet John Pule. Empty Heads ran for two issues before Luker shifted his energies to running his Industrial Tapes label, starting the Flying Nun band Phantom Forth, and eventually moving on to create bespoke one-off artist’s books.

Ania Glowacz

Ania Glowacz is the creator of mideighties Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington zine Submission, which mixed sociopolitical commentary and collage with Glowacz’s fandom for the band Flesh D-Vice. Submission ran for several issues before Glowacz moved on to other forms of music journalism, magazine production, radio work and audio engineering.

Eighties Aotearoa

1980s Aotearoa is a world away! Here are some of the contextual considerations that will, I’m sure, confound the younger reader and make those who can remember the eighties feel as though they’ve been alive for a very long time.

In January 1980, Aotearoa New Zealand had enjoyed a second television channel for fewer than five years. With TV2 came the late-night music videos of Radio with Pictures, videos deemed inappropriate for daytime broadcast. You were less likely to see anything exciting on the daytime top 20 rundown Ready to Roll. Some top 20 songs didn’t even have music videos, in which case TV1 might roll out the Oomph Dance Troupe for some synchronised leotard action.

Import tariffs and licensing controls meant that any records, clothes or books beyond mainstream interests might be hard to get hold of. Conversely, Aotearoa was flooded with weekly music tabloids from the UK that reported on the post-punk revolution in music. In response, bands were formed, street fashions changed, and fanzines and independent record labels were launched.

In June 1981, Joy Division’s ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ was the topcharting song in the country, despite receiving no commercial airplay. A month later it was the New Zealand population that was torn apart as every adult was compelled to decide whether they did or did not support a tour by the visiting Springboks rugby team from apartheid South Africa. Every test match invited a violent pitched battle between police and anti-tour protestors.

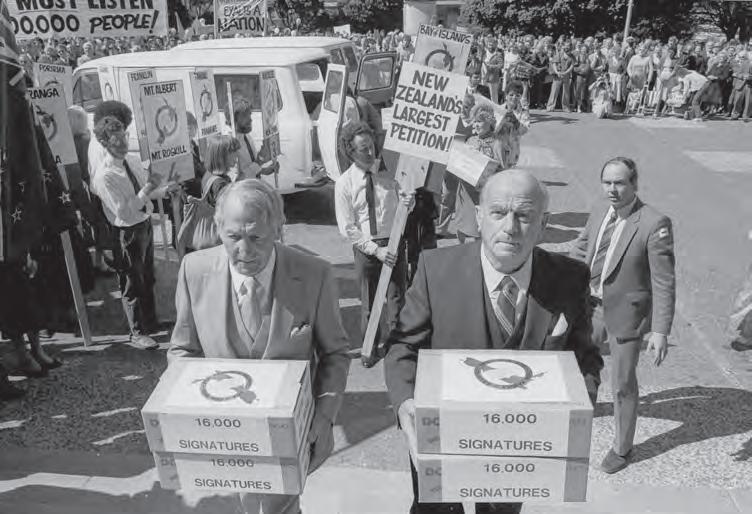

Former Napier mayor Peter Tait and businessman and former mayor of Mount Maunganui Keith Hay carrying boxes into Parliament containing the petition against homosexual law reform, 24 September 1985. Alexander Turnbull Library, EP/1985/4285/25-F

In November 1982 a young Auckland punk and Springbok protest veteran named Neil Roberts attempted to blow up the centre of state surveillance, the Wanganui Computer Centre. Roberts died in the blast, damaging the building’s foyer but failing to disrupt the centre’s operations.

A heated social divide of a different kind arrived a few years later when MP Fran Wilde introduced a parliamentary Bill designed to decriminalise gay sex. The Homosexual Law Reform Act was voted in by a narrow majority and signed into legislation in July 1986.

Anti-Springbok tour demonstrators overturning a car on Onslow Road, Kingsland, Auckland, 12 September 1981.

Alexander Turnbull Library, EP-EthicsDemonstrations-1981 Springbok tour-0

Eighties Zines

Dave White I’m getting all inspired to start writing again, eh. All this zine shit. It’s like, fuck,I’ve still got heaps of stories I want to tell.

Paul Luker I think I was quite comfortable going back to school, because in my last year I’d been a shocker. I was a second-year sixth. I repeated — yeah, I failed University Entrance. I was not focused at all. I can remember coming back for that second year from Nambassa,1 rocking into school thinking ‘Shit, enrolment’s today!’ Being dropped off by mates and going straight into school to meet the form teacher and being sent home for a shave, which I thought was a really good start. [Laughs.]

Dave White The first punk bands were at Nambassa. A band called The Plague played completely nude: a little guy painted blue, women painted yellow. So, there was definitely punk at Nambassa, and there was a feeling that anything went, like you could do anything you wanted, and it didn’t matter. You could always make money by playing crappy old hippie music, but if you wanted to do something different . . . I don’t know whether we realised that it was a revolution or if it just seemed like the music scene was evolving.

Paul Luker I think Rip It Up2 was probably doing a fine job at the time, but anyone really into punk rock would’ve been left thinking ‘More Warners ads’, ‘Hello Sailor again’, ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, Dragon — just let Australia keep them’. That was Rip It Up’s bread and butter; it would have made some think ‘Is it worth reading all this just to get to a one-inch column on The Steroids?’

Ania Glowacz I’m just the black sheep of the family. When I was burning candles and incense and listening to records in my bedroom and my little brother’s going ‘Urgh, the incense is giving me a headache’, and my dad thinks I’m devil-worshipping. It’s like, ‘Man, I’ve gotta get out of here.’

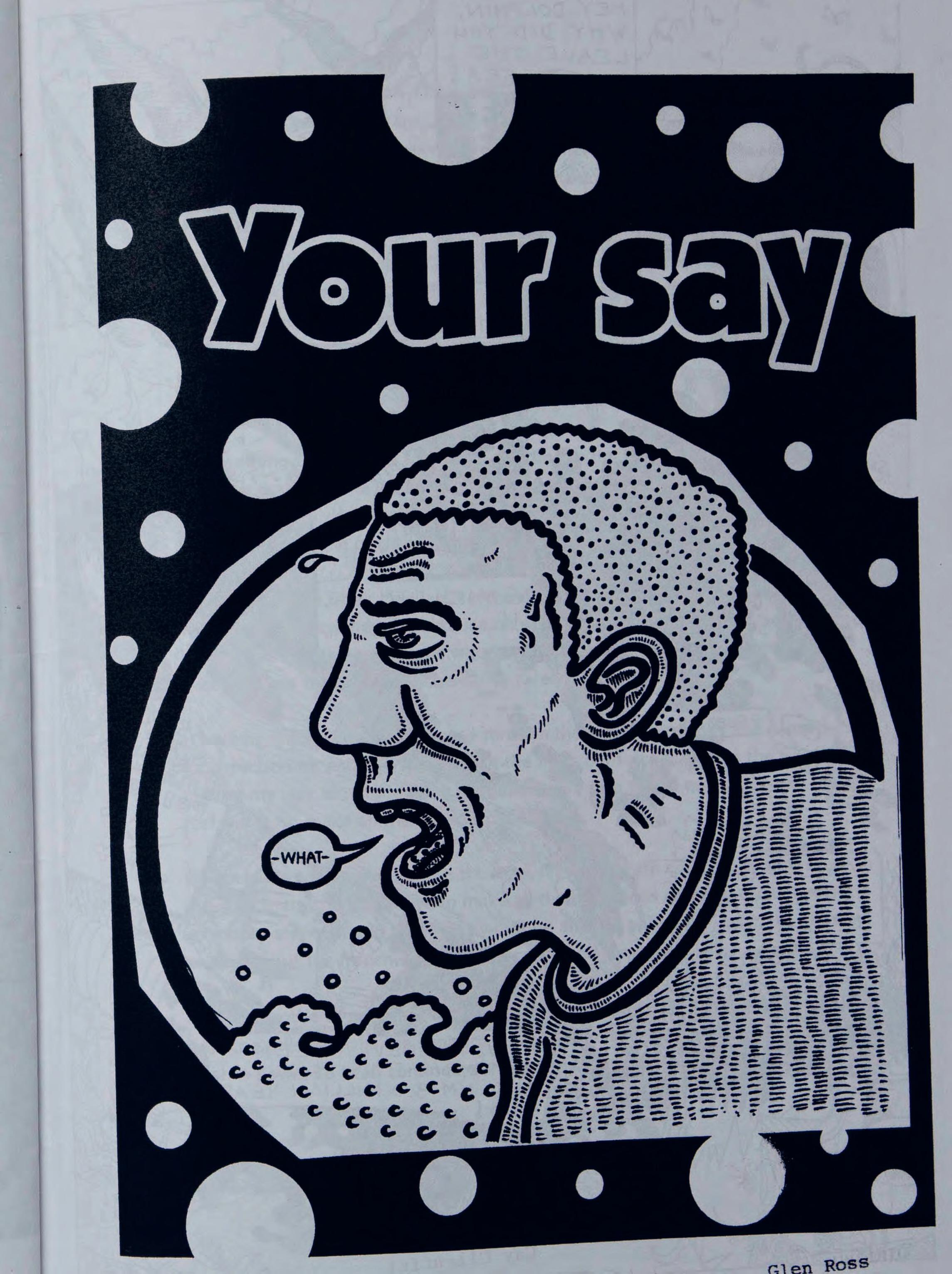

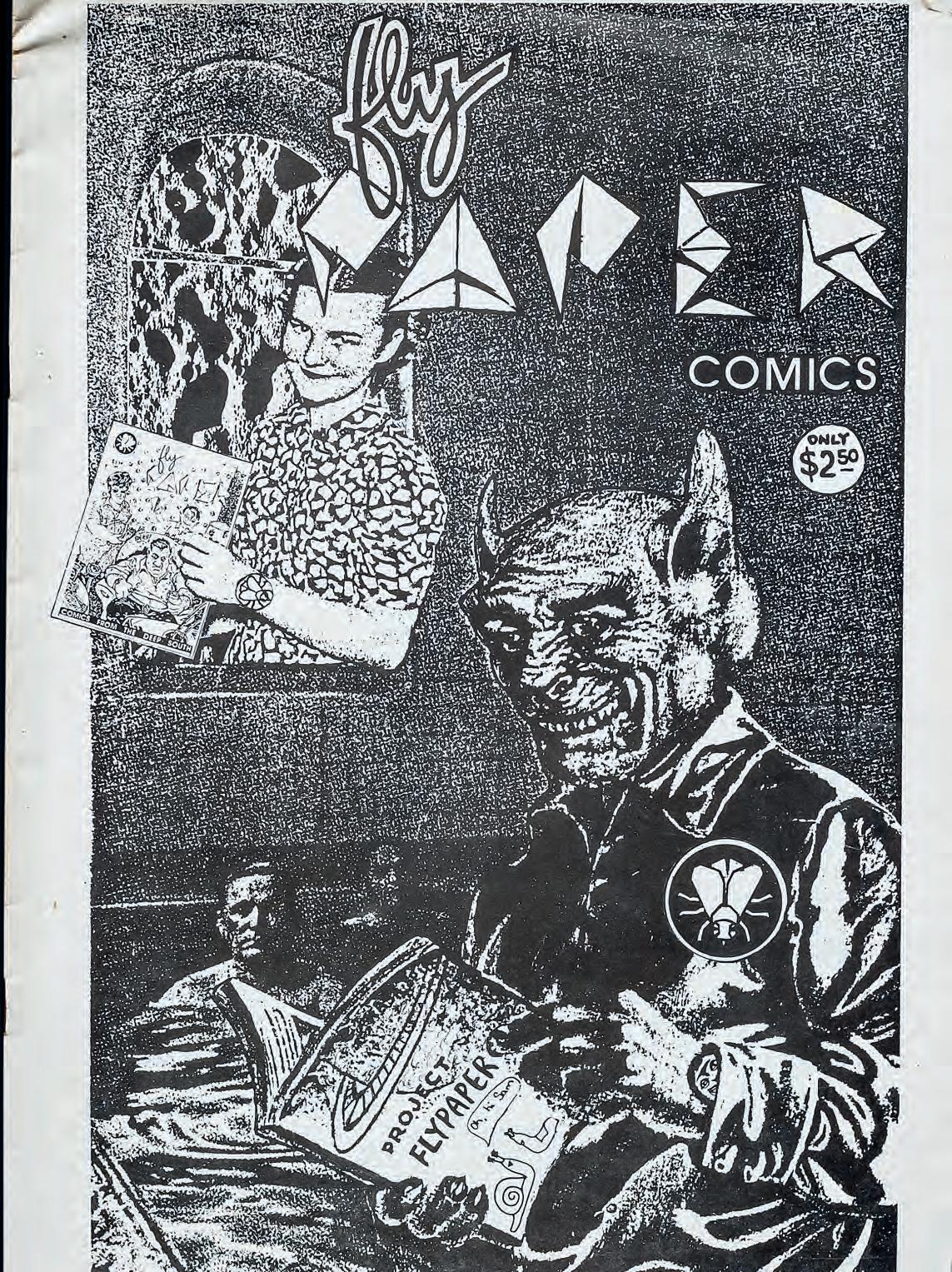

8. Fly Paper, edited and cover by Gregory Edwards, A4, 1984. Ōtepoti Dunedin.

Tracey Wedge I sent my parents to the anarchist bookshop in Redfern, Sydney, to buy records for us to review. So they obviously accepted what I was doing, they were more supportive than judgmental.

Lyn Spencer Punk introduced me to a lot of ideas that I otherwise wouldn’t have known about. I got into punk after working on sheep farms and mustering. I arrived home having decided I didn’t like killing sheep — the farm always used to get me to kill sheep to feed the dogs — I hated it. I got home and my sister had got into punk, and she’d gone vegetarian, and I go ‘Oh! Vegetarian? I didn’t know that was a thing. Oh, yes, I want to go vegetarian.’ I didn’t like what I was doing on the farm.

David Merritt As soon as I heard Mark E. Smith, that was it. I thought, ‘Fuck, this is amazing. It’s not even good but I like it.’ I don’t like polished music. I don’t like music that’s clearly been through the hands of 16 professional engineers to get to that sparkly FM sound.

Robert Scott We’d get the NME 3 and Melody Maker 4 three months after they’d come out, coming over on the boat from England, that would be us keeping up with the music scene. There wasn’t an equivalent American magazine, maybe Creem,5 but I don’t think the American publications came over as much, it was definitely the English ones. Then there was Barry Jenkins on ZM. He would play a lot of new music. He’d have excerpts from the John Peel show, and he’d got the English records somehow and played a lot of new stuff that shaped a lot of people’s musical tastes, whether it was Buzzcocks or Wire, stuff like that or slightly more left-of-field stuff like Vic Godard and John Cooper Clarke.

Andrew Schmidt The journey began back in London on the boat, and then we got it. The threemonth thing is something that always comes up and it interests me in a way, as a historian. I don’t think the time lag was, in a historical sense, that long, but because it’s popular culture it seemed quite long back then. Nobody ever stopped reacting to it just because three months had passed. We were still going to do something once we got that information.

David Merritt God, CAN were a big thing for me. I loved CAN when I discovered them. It’s funny, eh, we would have to listen to Barry Jenkins on the one radio station — this is pre-student radio — or Radio Hauraki, just to try and get interesting music from overseas, otherwise it was just bullshit, bullshit, bullshit, y’know, crooners and middle-of-the-road America, ‘A Horse with No Name’. If I fucking hear that song again! ‘Welcome to the Hotel California’, ad nauseam.

Paul Luker I’d walk through the railway station to catch the bus to my Comprint job. The railway station had the best newsagent in town. It had the airfreighted NME and Melody Maker. If I had the money I’d buy the airfreighted issues. I’d rather not eat because, honestly, there were some amazing writers in there. It was fucking weekly, what luxury. ‘Oh, Joy Division, well, if you think that’s good . . .’ I would order the records I was reading about. It was easy to send to the UK for them: Swell Maps, Joy Division.

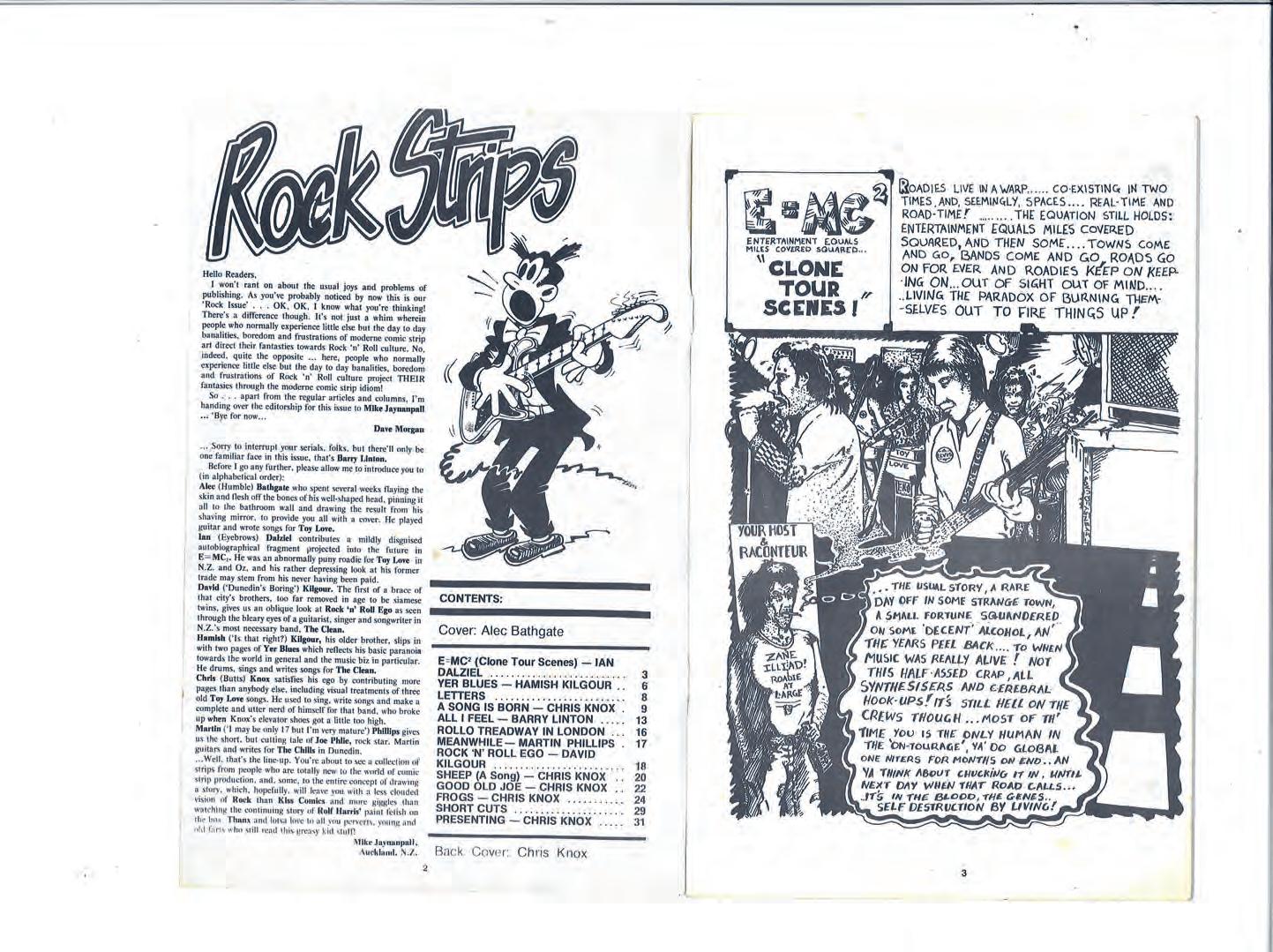

9. Strips #16, The Rock Issue, guest editor Chris Knox, 165 x 243mm, 1981. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

Andrew Schmidt It was really a combination of growing up with magazines like the NME, which we would get in Paeroa every week, and a lot of people had that experience — it would go all around the country. There were four music magazines coming in from Great Britain. That’s a hell of a lot of information and that’s a hell of a lot of influence. Sounds,6 Melody Maker, NME and Record Mirror,7 which was a bit more mainstream, but it was the one that Peter Jefferies and Graeme Jefferies8 read in Stratford. Record Mirror had a lot more disco and stuff, which I would love now but back then I probably would’ve preferred the NME.

Tony Renouf Love onomatopoeia, love MAD magazine. Don Martin, Sergio Aragonés are my big loves. It was all really cool, and I kind of liked Spy vs Spy, but that got a bit same-y. Don Martin and Sergio Aragonés, what those guys could say with one picture, or one silly word was just fabulous.

Matthew Campbell Downes The other thing to mention is of course Strips, which was Joe Wylie and all that lot. That would’ve been Lorenzo van der Lingen’s guiding light. I believe Strips started in ’77. We were sort of like ’79 to ’81. Strips was the shining light. We were all like: ‘Wow, these comics are as good as Heavy Metal magazine, and they’re made here!?’ It showed that it was possible. We used to pore over Strips. There probably wasn’t a drawing session where Strips comics weren’t on the table next to us and if you look at Mark Morte’s comics and mine, and maybe to a lesser extent, Lorenzo’s, you’ll see direct influences from the likes of Joe Wylie. He was our clear favourite. To us Joe was up here [holds hand aloft] and everybody else was a big chunk below, still quite good, but Joe was up here.

No, you wouldn’t find Strips in the Four Square, you’d go to Scorpio Books. They also had Heavy Metal magazine, which was probably the only really alternative comic you could get in New Zealand. The other big influence of course was MAD magazine We were big fans of MAD, and being big fans of MAD we hated Cracked and all the other MAD copyists. But Sergio Aragonés and Al Jaffee, we loved all that stuff. You could get MAD at the local book shop. That was available.

Nineties Zines

Dave Hegan I left Christchurch in about May 1988 because I’d heard there was a

good punk scene in New Plymouth.

I’d been flatting with some punks and skinheads. Back then, punks and skinheads all hung out. Now they hate each other. They hated each other then, but it was just more relaxed. They said, ‘Oh, you should go to New Plymouth, there’s heaps of drugs and lots of good bands’, and I was like, that sounds good to me and so I just moved up. I moved to Hamilton first. My dad was living there, and I lied to him and said, ‘I’m coming up to go to university’, because I needed to get to Hamilton to get to New Plymouth, but when I got to Hamilton he figured out what was up and kicked me out. So I just caught a bus down to New Plymouth on a dole day, that’s how I ended up in New Plymouth. I knew the punks drank at the White Hart pub, so I went there.

Long story short. I got into the whole punk scene, but everything got out of control, the drugs and stuff like that. I ended up getting done for burglary of a supermarket, which I didn’t actually burgle. There was a whole bunch of us, and I crashed out at the scene because I was too wasted. I didn’t even get inside the building. The police found me outside and said, ‘What are you doing?’, and I’m like ‘Oh, I’m just having a sleep.’ But anyhow, they said to me ‘Look, we’re sick of this. If you plead guilty to being unlawfully on the premises, we’ll charge you for that and we won’t charge you for burglary’, and I’m like ‘Great, let’s do that’, and then they chucked me in the cells for the night. The next morning, I’m up in front of the

judge and he says ‘Dave Hegan’s pleaded guilty to burglary’, and I’m like ‘What!? This is news to me.’ Life changed really dramatically. I got a year’s probation and I got sent to drug rehab, which was actually a good thing because I was doing a Sid Vicious — crash and burn, die young. I ended up coming back to Christchurch to live with my mum. It’s weird, you’ve got to sober up before you go to drug rehab. At least that’s how it was back then. You had to have a few weeks clean before you could go to Queen Mary Hospital in Hanmer. It made sense for them. There was six months of drying out in Christchurch before rehab. All of a sudden I had all this time on my hands because all I’d been doing was getting wasted, hitchhiking around the North Island and going to gigs, so that’s when I decided to do a zine. I was really into all the bands and the politics and stuff, so I just started posting interview questions off to bands and asking all my mates if they wanted to contribute. I had all this energy. I was also screenprinting and all sorts of other stuff. I got out of rehab in November ’89 after six weeks, and then I published my first zine in early 1990.

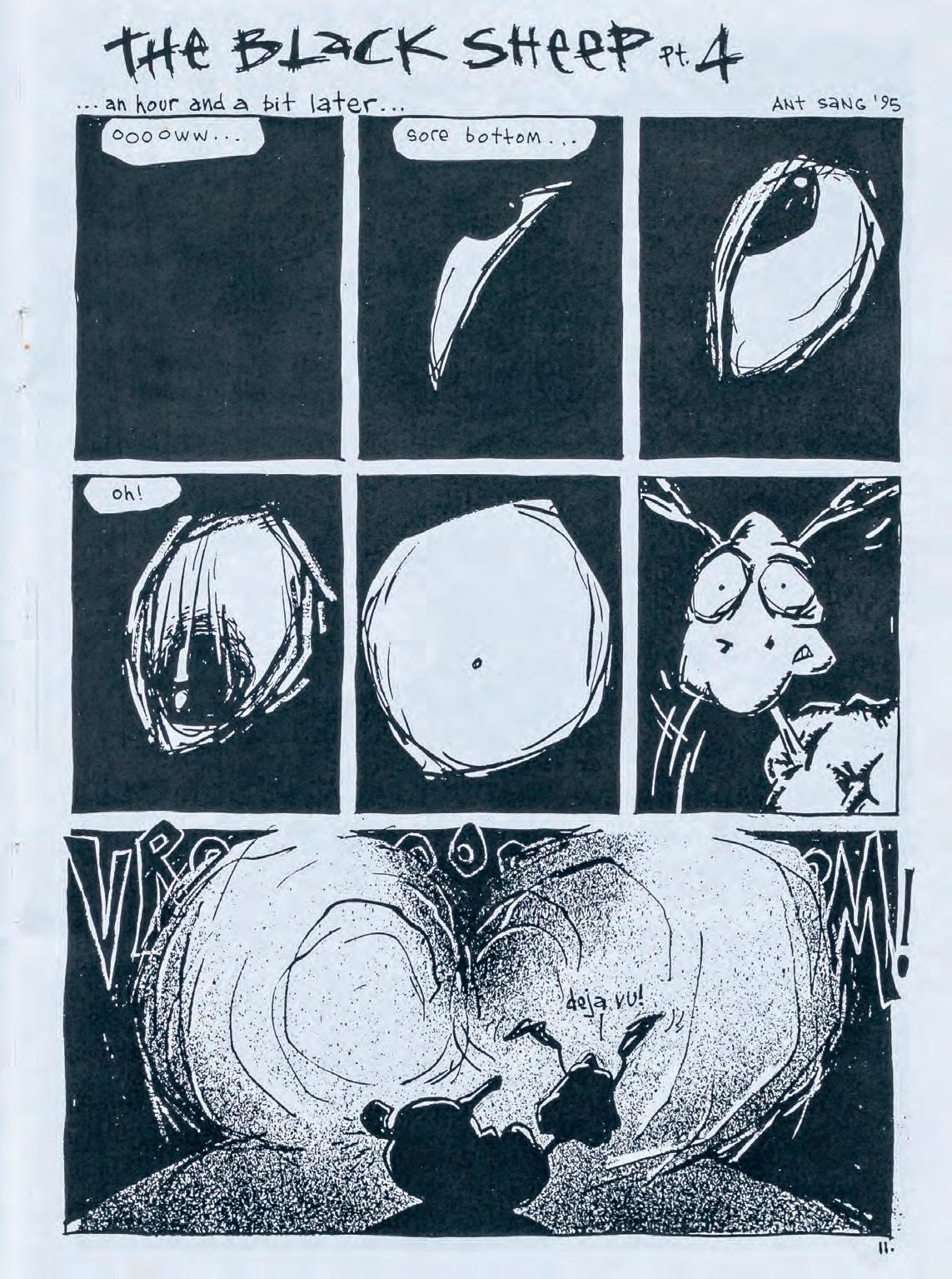

63. Filth #5, Ant Sang, A5, 1995. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

David Merritt Michael O’Leary, he’s a lovely man, he was the best poetical role model I had at the time. He’s like me now, but I met him when I was 25. He was this big man. He had a huge beard, he was Irish, he drank like a fish and he ran this thing called the Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop, or ESAW. That was his press. He’d always run bookshops. When I got to Dunedin he had a bookshop in The Octagon called The Mother of All Potatoes, don’t ask me why. Of course, I headed straight in there, couldn’t resist, met him, liked the bookshop, volunteered to work there because, y’know, I’d arrived in Dunedin. I was working three dishwashing jobs trying to get by. I was flatting in View Street, which is in the middle of town, but my rent was like $12 a week. I was living on maybe 50 bucks a week or something, and I could earn that money as a dishwasher. I had time up my sleeve . . . I had PageMaker skills by then, and I was doing the Spec magazine with Caro McCaw for Radio One. I’d learnt a bit, so I started to help Michael O’Leary put out publications. We did about three or four books in the space of a year, and I got the bug after that. I thought, this is what I want to do. I think I already knew that anyway.

You pick up skills when you’re young and they’re useful to you all your life. Often the skills that you pick up are just a reincarnation of a skill that you’ve already picked up, just applied slightly differently or with a new form of media.

Indira Neville It didn’t occur to any of us that you didn’t have licence to just make whatever, it wasn’t a choice or anything. The music’s funny, too. Now it’s weird that these fancy arty European labels are re-releasing all this early Plop stuff [Oats’s music arm]. It is weird how what starts out as drunken mucking-around becomes art in a different context years later. I don’t know, it’s fascinating. Even Funtime, they didn’t drink but it was still mates just doing shit over cups of tea. Back in the day, they were the only group with the same ethos as Oats.

Beth Dawson As a piece of journalism, zines are such a good capture of a particular time and place. They capture a scene and the voice of that scene, which is why it’s so nice that my friends and I have those zines that Liz made in our teenager years and our early twenties. It’s this little snapshot.

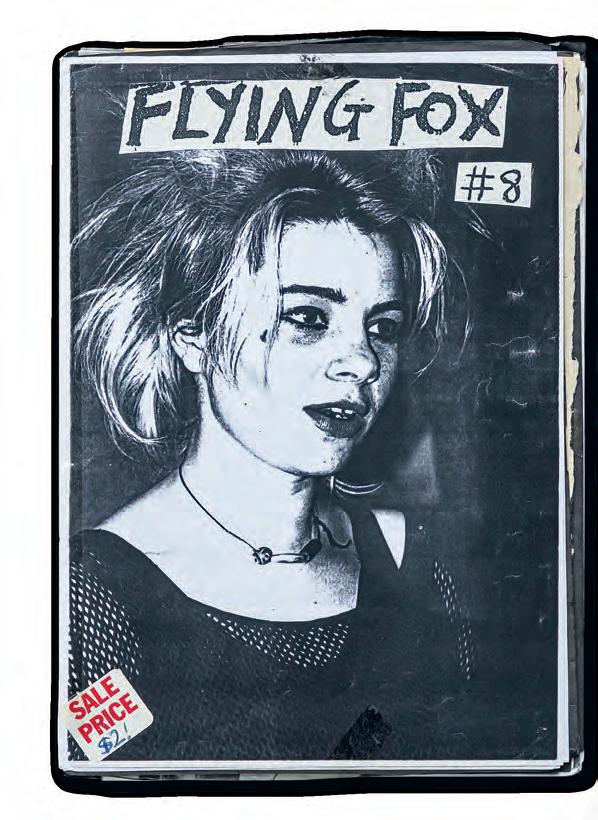

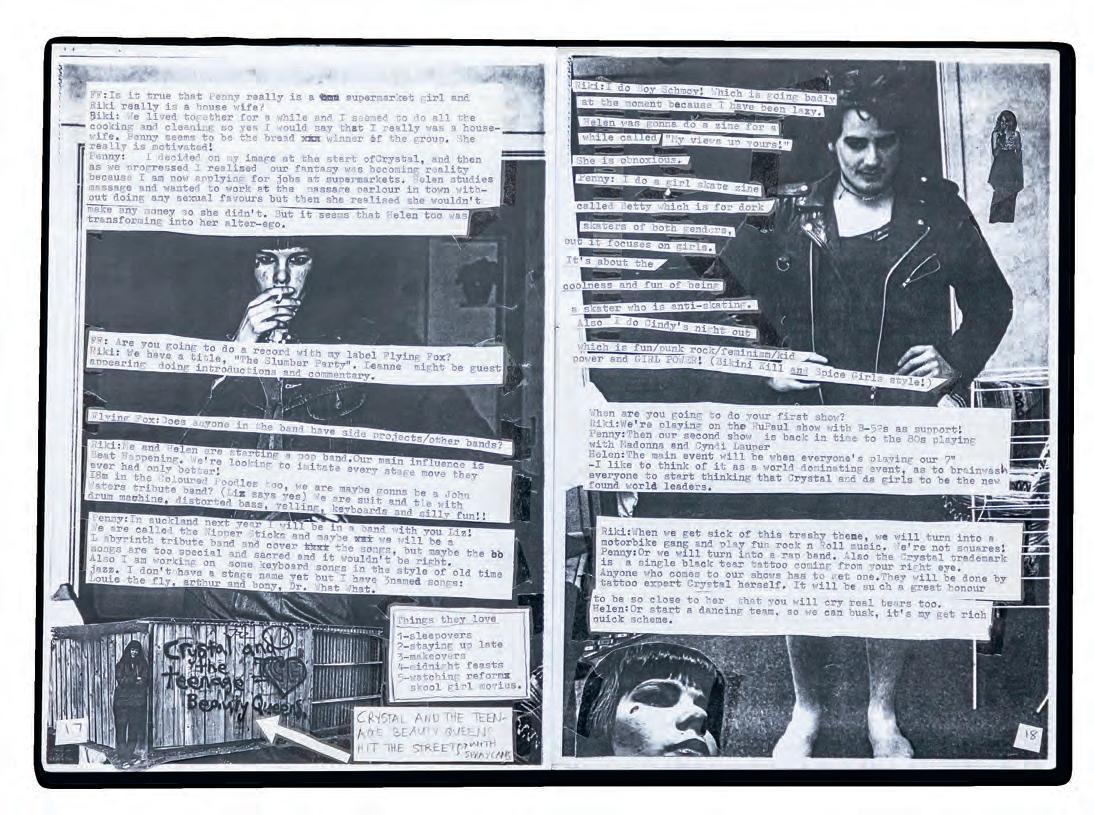

76. Flying Fox #8 cover and spread (analogue master for black-and-white photocopying), Liz Mathews, A4, 1998. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

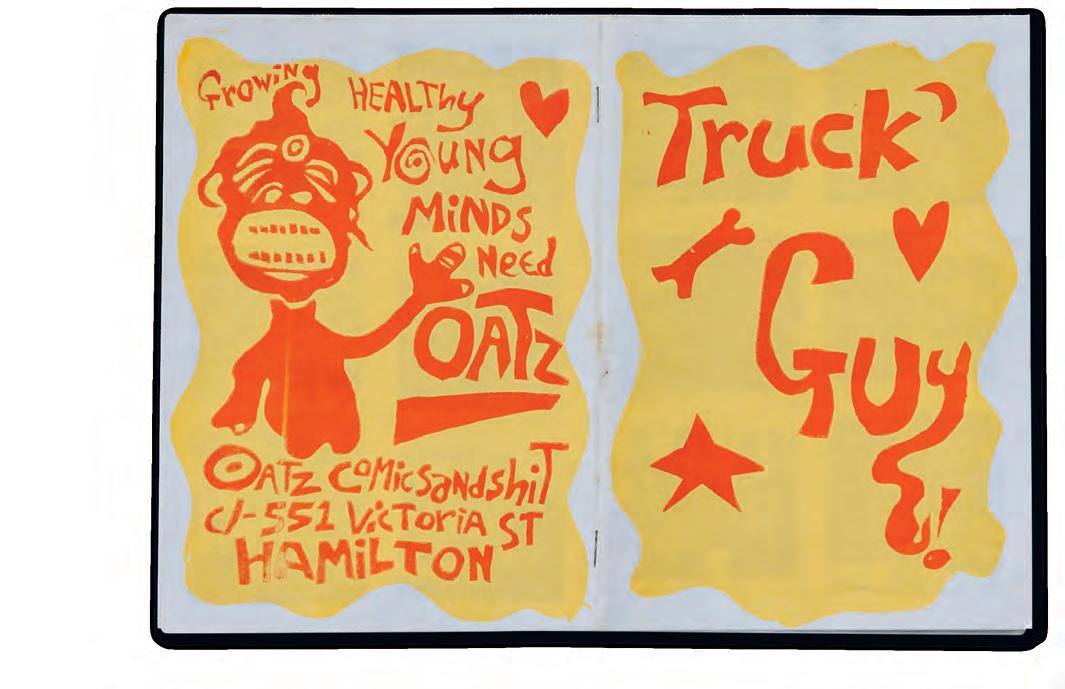

77. Truck Guy front and back covers, Glen Frenzy, A5, 1990s. Kirikiriroa Hamilton.

Nineties Aotearoa / Nineties Zines / Getting started

Bruce Grenville This is a typecase. There’s the map of it. You see all the capitals are all here, the rest of it’s all there, and like a QWERTY keyboard, every printer is totally familiar with that. The ‘e’s are always there and ‘a’s are always there, so we can actually typeset quite quickly because we know where they all are. Hold that letter in your hand. Now, notice it’s got a little nick on one end of it? That’s to show you that’s the bottom because if you get a letter like a capital ‘O’ it could be the same either way, so it’s important to know which is the bottom, otherwise your line’s going along and then suddenly — wobble. Everything is the same height. It’s .918 of an inch, which might seem an odd size but it’s the size they standardised everything to. Once you’ve set it all up and printed, then you’ve got to clean it and put everything back.

David Merritt The older economics of scale have gone. If I’m printing on web offset, sure, I may as well print 1000 copies as print 10, because the [major, fixed] cost is in setting up the fucking job, but if I’ve got a photocopier, it’s just the cost of paper and toner for each copy. There’s no economy of scale. The paper costs the same, the toner costs the same.

Bruce Grenville I ended up having lots of these typecases. In fact, that cabinet we were looking at there came from that same studio at Auckland University. As did quite a few of my chairs and things as well. I also got heavily into offset, which is much easier than letterpress printing because you just provide your copy and then photograph it and a relief is made of the photographic image. It’s much easier to print.

Lyn Spencer And you could get little pictures made up — what were those called again? Ross Gardiner Polymer blocks. Lyn Spencer Polymer blocks, yeah. So, you’d get a picture and put it on the press, if you wanted a logo for your zine or something then you could just use that to make pictures as well. Ross Gardiner Print it in colour. Yeah, it was basically like woodcutstyle printing.2 You’d just take a picture into some [graphic reproduction] company, and they’d duplicate it onto a sort of plastic resin-type stuff [and mount the resin image on a piece of wood]. So, you could make any graphic into a raised block, and then you’d print it on a letterpress machine. It could be a photograph or just a line drawing or whatever.

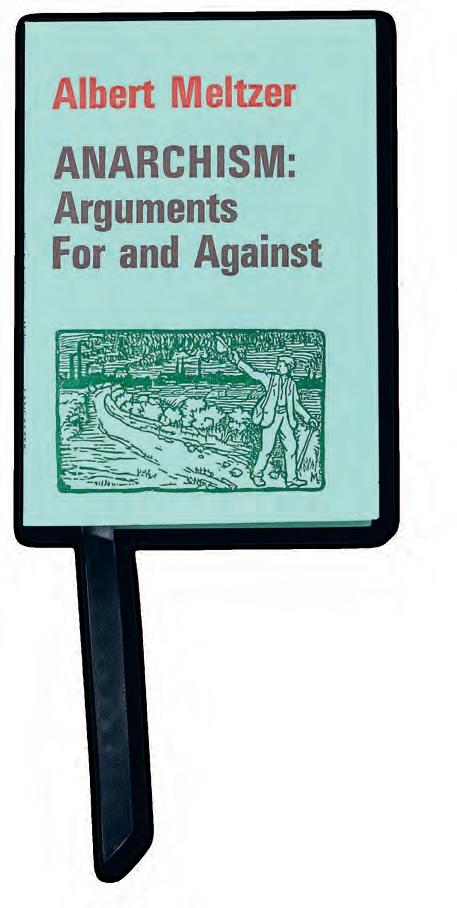

96. Anarchism: Arguments For and Against, by Albert Meltzer, reprinted by Bruce Grenville, A6, 1991. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

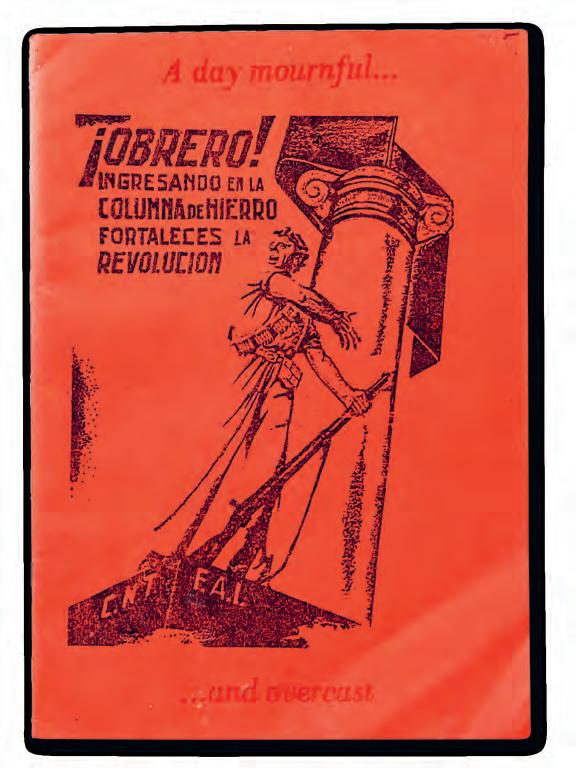

97. A day mournful and overcast, anonymous, reprinted by Ross Gardiner at Bruce Grenville’s Tāmaki Makaurau print studio for The Freedom Shop in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, A5, mid-1990s.

Bruce Grenville I showed Ross Gardiner and quite a few others how to use the press. Here’s [Larry Law’s] Revolutionary Self-theory: A Beginners’ Manual. I didn’t see Ross print this one, he just set up and did it without me. What he’s done here is print a front and back cover on nice card, then all the complicated inside pages are just photocopied from the existing book. He’s sewn it, because in the printing industry we consider staples a very bad idea because they [rust away and damage the paper, and] are not archival. Here, on the other hand, this linen thread will last forever.

Here’s another Ross-ism. This is A day mournful and overcast [1937],3 which, once again, he printed without asking me, because if he had I would have said, ‘Well, red-on-red is not gonna show up well.’

This is The Heretic’s Guide to the Bible [edited by Chaz Bufe , 1992] 4 It’s all photocopied, but Ross has done a bit of letterpress at the bottom in green to make it look nice. A very good book, but it’s all bootlegged, just photocopied from

an overseas product because he was doing [it for] the anarchist bookshop in Wellington, The Freedom Shop; they wanted copies to sell. This one here is the Cycle of Starvation: The Third World War, which is one that Ross actually wrote and researched. Originally it was an article for The State Adversary, but then he thought he’d better do it as a stand-alone zine. It’s all done on my IBM [Selectric] Composer so it’s all quite nicely typeset. The IBM Composer is that golf-ball typewriter. It has interchangeable ‘golf-balls’ with different fonts so you can go from 6-point to 12-point [and change typefaces]. If we wanted bigger stuff, we used the photocopy machines that enlarged things. Originally, photo-copy machines wouldn’t do enlarging, they’d just do the same size you started with. And early days, everything from a typewriter was basically one size, 10-point or whatever it was.

Kerry Ann Lee Thank goodness for kindly parents who let you use their work photocopier after hours! Sometimes you get money from zine sales; all those $2 zines might add up to a hundred bucks if you’ve got a few titles and you’ve been saving. Then you could lay down some serious change at a photocopy shop like Datastream, and they’d help you out because they’ve done it more than once. Kay and Tony at Datastream would help. ‘Do you want this?’ ‘Is it like this?’ ‘Is it good like that?’ and you’d work with them.

‘Okay, what can I do?’ ‘You be useful and you fold these things.’

You’d co-create with them. You’d learn how a photocopy shop works. Know what to do with paper jams: especially if it’s not your photocopier, you don’t want to get your friend’s parent in trouble. They gave you the key and they trusted you and you don’t want to fuck up their work machine.

Andrew Stephens I printed some at my library job for a while, and then it just wasn’t cool anymore so I got them done at the print shop. I’d stopped paying for any of it at the library. I considered it a work privilege, but after a while they thought I was taking the piss. In the end I bought a little flatbed single-sheet printer and started doing it myself, very slowly and painstakingly.

Jarrod Love’s a guy in Palmy who used to write zines. He had all the gears so I used to talk to Jarrod about zines and borrow stuff like his longreach stapler so I could staple in the middle of an A4 page. Jarrod wrote a damn good zine, eh. He was really funny. I remember he wrote an article about his addiction to sliced cheese. Trish Stephens He spent a month or something living off white bread and processed cheese slices.

98. Undercurrent #5 cover and spreads, edited by Jarrod Love, A5, 1997. Te Papaioea Palmerston North.

Indira Neville We just photocopied everything in Hamilton at the Centreplace copy centre, and it was great because the people there got to know us. You get the photocopying the wrong way round, or cut off or something, and you’d just secretly chuck them all away and do it again and again. I don’t know what they thought of us, ‘There they are again, photocopying weird things, not CVs or anything’, and it just got to the point where they’d overlook the number of wrong copies and not charge us for the 15 crap ones that ended up in the bin.

99. Pick Pick front and back covers, words by Indira Neville, pictures by Stefan Neville, Oats Comics, 105 x 105mm. Whāingaroa Raglan.

Twothousands Aotearoa

Beyond the music, eighties punk zines responded to incidents of police brutality, irrelevant royals, the bullishness of Prime Minister Robert Muldoon (who was ousted in the 1984 election), nuclear testing in the Pacific . . . all manner of contemporary issues. But such real-time reaction waned through the nineties, and by the two-thousands had all but disappeared as identity came to the fore. At the level of content, the politics of zines in the two-thousands might be feminist and personal, reacting to the age-old violence of patriarchy rather than zeroing in on a specific governmental issue. Riot Grrrl influenced zines in Aotearoa long after its mid-nineties heyday in the US. Other twothousands zines were completely apolitical in their content, but mounted a challenge at the level of aesthetics and mode-of-exchange.

Two-thousands Zines

Pritika Lal You could walk past a café or a music store and pick up a really

had just left in the

significant piece of work that someone

doorway.

That’s how I found out about zines, from just picking stuff up out of doorways and then thinking ‘What? This is a whole thing — this is not like a flyer. Maybe we could do something like this?’

Tessa Stubbing The first zine I ever came across was something called Punk Brazil, which I found in Real Groovy Records when it was on Queen Street. Maybe it was dropped off by a tourist or a traveller or someone who’d immigrated here. Real Groovy had a little rack in the doorway where you’d have all the flyers and stuff. Someone had dropped Punk Brazil in there. I don’t know if there were more zines there at the time, I just remember that one because I grabbed it and I was like ‘This is cool, oh my gosh.’ The printing wasn’t even double-sided, each page of content sat next to a blank page. It was pretty low-budget, and that was cool. Did I know it was called a zine? No, I don’t think so. We’d just got internet at home with a 14.8K modem — so, so slow. I looked up punkas. com, and from there I found out that this thing was called a zine, and then I found Moon Rocket zine distro. That’s where I used to order all my zines from.

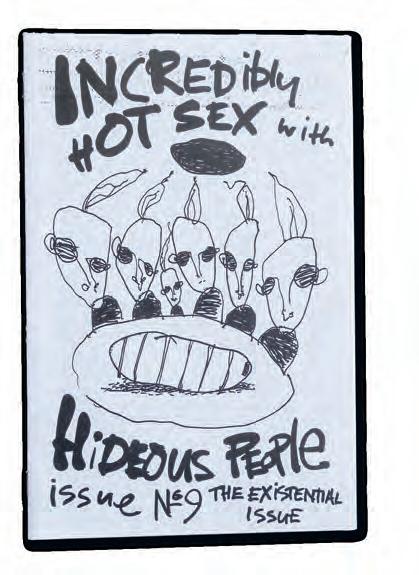

Kylie Buck I’m pretty sure that Incredibly Hot Sex with Hideous People was the first zine I ever came across, either in Olive café or Midnight Espresso on Cuba Street. I would have just picked one up and been like ‘What the hell is this?!’

Pritika Lal A bunch of us K Road people were working at this shitty call-centre in the evenings. Everyone would doodle on the backs of the customer-service info sheets we were supposed to be filling out during calls. Stefan Neville was also working there, and I gave him this info-sheet doodle I’d done. One day he came into work and presented me with a little book of info-sheet doodle art that included my drawing. He’d made this beautiful little book with a hand-printed cover. They’d been photocopied at A4 and then cut into slivers. That was the first time anyone published anything of mine, and I was like ‘Wow, this is amazing. This is now a book? This was just a bunch of conversations.’

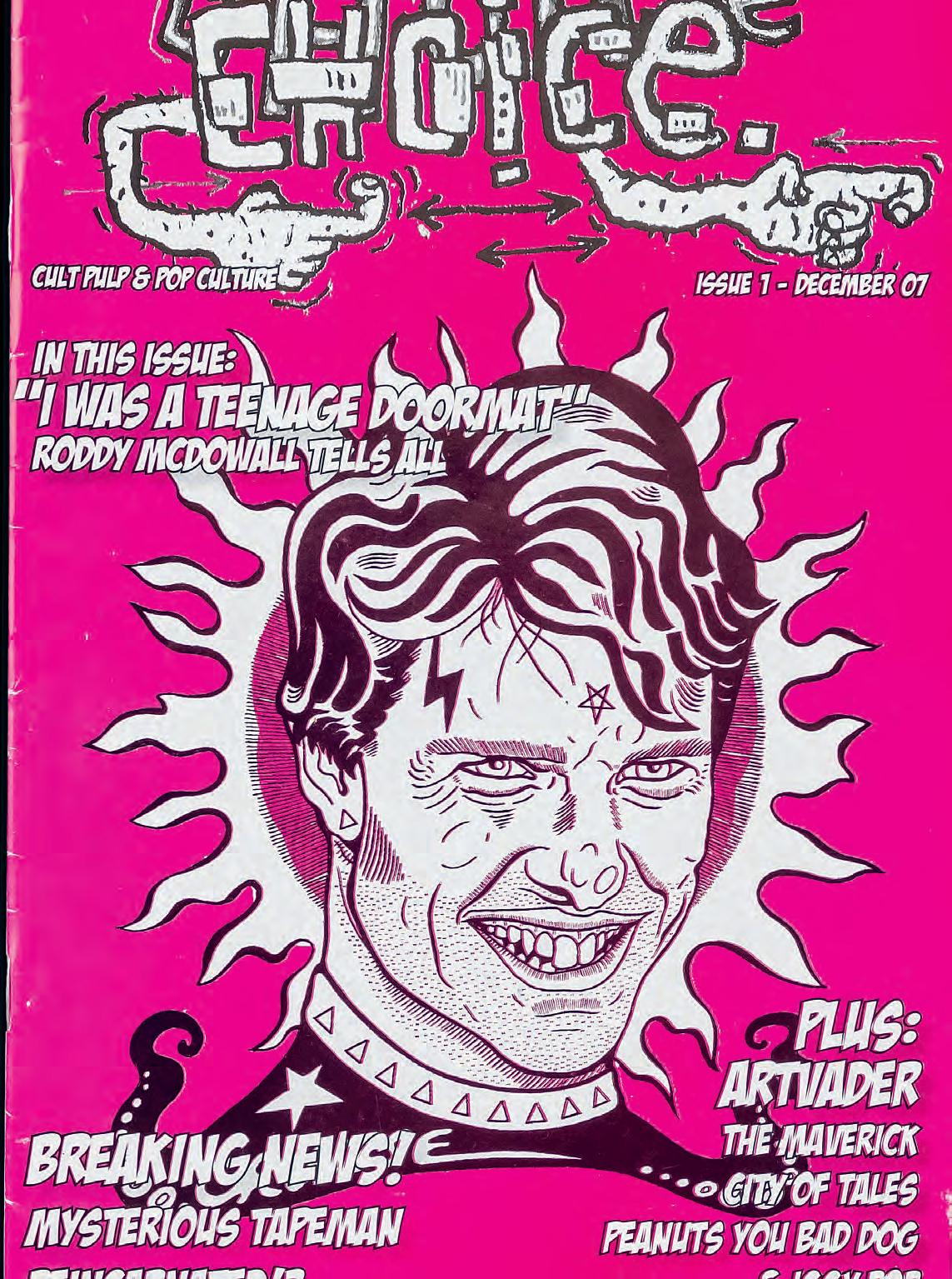

113. Choice #1 detail, edited by Mitch Marks, 260 x 170mm, 2007. Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Tui Gordon I left Rotorua and came to Auckland, where I discovered that there were all kinds of people who weren’t like the people I grew up with, including people like Ant Sang, who lived in warehouses. I got to see punk zines and comics. It even got me into drawing comics. When I moved to the UK, I used to draw some of Ant’s stuff on the walls of my squat. It was really nice being able to do that. I’d been to university and studied literature and stuff. I even remember making a zine before I knew what zines were. I called it a magazine, but it was just a stapled piece of A4, an anti-capitalist thing. I never really understood the whole glossy magazine thing and all of that pop culture,

because I was raised by hippie Buddhists, gentle reggae-listening hippies, lentil-eaters, y’know? I definitely had grounding in the animal rights stuff, but the fierceness of punk was pretty alien. I kind of got into punk via ska, because reggae goes to ska goes to punk, and then I got to Riot Grrrl after that, once I realised how cool it was seeing women being tough and making music, which I hadn’t really seen before.

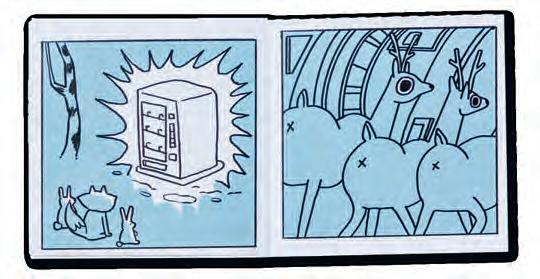

114. Milk Milk Lemonade front and back covers and spread, Clayton Noone and Stefan Neville, Oats Comics, A5, 2000s. Ōtepoti Dunedin.

Kylie Buck I just thought it was awesome because Incredibly Hot Sex with Hideous People is a perzine. I don’t know if people call them that anymore . . . Who wouldn’t wanna read some rando talking about their life, that’s totally my jam. I was at art school, and you were writing about art and teaching and all sorts. I would’ve just been like ‘Yes, this is my scene . . .’ I wouldn’t have thought of it as art. I would’ve just been like ‘Oh, sweet, someone wrote a little book about their life.’

115. Incredibly Hot Sex with Hideous People #9, Bryce Galloway, A5, 2002. Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Moira Clunie The Moon Rocket online zine distro launched on 1 January 2000. I figured that went with this whole futuristic thing.

Kylie Buck We ordered some zines from Alex Wrekk’s distro in Portland, and some from Cherry Bomb Comics and Moira Clunie’s Moon Rocket distro in Auckland.

Moira Clunie I had a part-time job working for ihug, the internet service provider in the late nineties–early 2000s, and I remember going and getting coffee from a café and the people on the table next to me were talking about email and how interesting it was that their work had decided to get an email address. That would’ve been around the turn of the millennium, so, y’know, it was still seen as a bit of a business-y thing or a nerdy thing, and certainly in terms of putting content on the internet, that was a bit more technical and involved. It wasn’t like you could just sign up for Instagram or get on Facebook and have a presence for yourself online. You had to make your own webpage, figure out where to host it, that kind of thing. There were GeoCities and some of those early web hosts but it was probably quite a niche thing.

Kylie Buck We sent away to Alex Wrekk’s distro in Portland for some zines, and I was like ‘These are fucking amazing!’ In one of my favourites they’d gone dumpster-diving out the back of the university and found all these old submissions for entry into the doctorate programme, and the submissions had all these margin notes from staff about the applicants, like ‘Oh, she looks like she’ll be pregnant soon, so we won’t let her in.’ I can’t remember what it was called but I loved that one. Yes, it may have been a work of fiction.

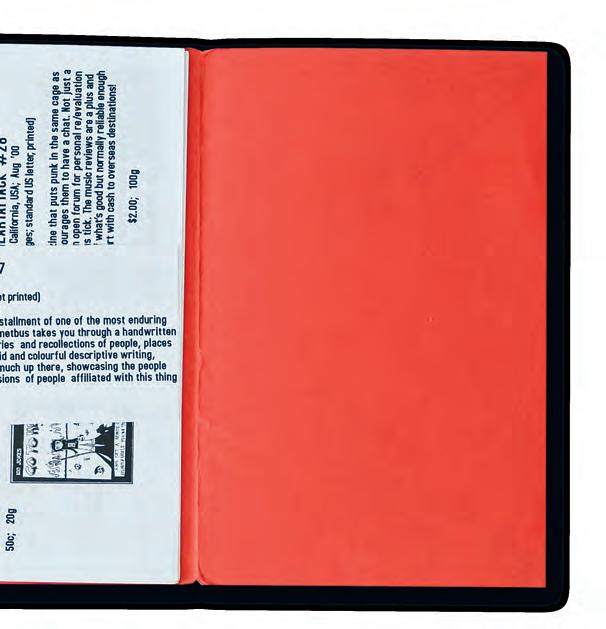

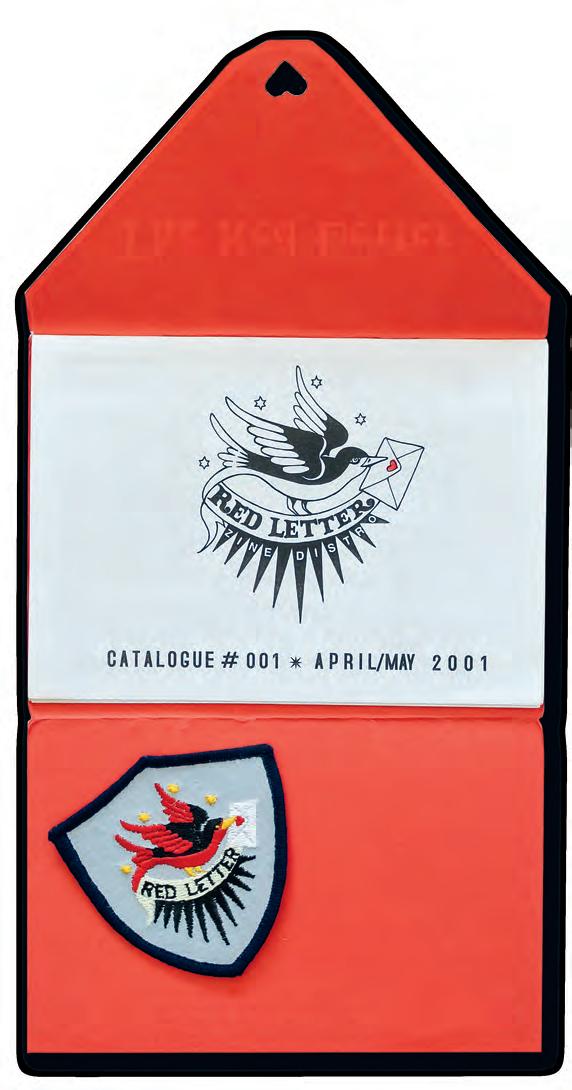

Kerry Ann Lee Red Letter Zine Distro was born after I finished design school and I realised that I had accumulated a whole bunch of really wonderful friendships and pen pals through zine-making and I was bringing stuff into New Zealand. I was swapping records for zines and zines for records and things from here in New Zealand for overseas, getting all these packages and letters and circulating them, I’m thinking ‘Shit, it’s more than just my friends who’d be interested in this stuff. I’m gonna try this out . . .’ Do a wee distro inspired by international distros overseas that would stock their favourite records and zines and do a really faithful job of promoting them. So that’s what the distro was about. It was gonna be a mail-order distro, and that was why I loved the idea of the catalogue, the idea that you actually go through and — like the school book clubs when you’re a kid — tick the books/zines you want.

I was also having the occasional table at the back of a show. At the time Wellington was really open for stuff like that. I’d get my distro catalogues into cafés and independent bookstores that were

up for trying out zines. Good as Gold used to stock some early Red Letter stuff. Dandelion — which was Rebecca Taekema and Lorene Harris’s shop — used to stock zines. There was The Family, which was Jason Lingard and Arlo Edward’s store. There were just all these cute little boutique initiatives by folks who were my age and who were like ‘Cool, just bring it in and we’ll see how it goes.’ That was the first time we were getting zines out on the street in Wellington, outside of the anarchist info store, different styles, not completely political, some of them comics. Things like some of Toby Morris’s early comics, and zines by the Cookie Cutter Collective that Louise Clifton and Dane Taylor were part of, Ant Sang (he was a friend after I became a fan of his early comic-zine Filth, and then he did Dharma Punks).

I was distributing Dharma Punks, early Disasteradio CD-R releases and Incredibly Hot Sex with Hideous People. I got to write to my favourite zines and ask to distribute them, like Cometbus, Heart Attack, Chunklet and Girlyhead. They’re so beloved, these zines. I mentioned these zines to new friends who grew up in the United States and who also read these same zines, and they’re like ‘Wow, you carried that in New Zealand of all places?!’

119. Red Letter Zine Distro catalogue and sew-on patch, Kerry Ann Lee, A6, 2001. Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Twenty-tens to -twenties Aotearoa

The zinefest model exploded through the 2010s and 2020s. By 2010, there were two annual zinefests: one in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and one in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington. Over the next 15 years they were joined by the annual or sporadic Ōtepoti Zinefest (from 2011), Ōtautahi Zinefest (2011), Kirikiriroa Hamilton Zinefest (2014), Tauranga Zinefest (2016), Palmy Zine Fest (2020), Whanganui Zinefest (2020), Kāpiti Zinefest (2022), Whau Zine Fest (2023), Taranaki Zinefest (2023) and Zine Fest Nelson (2024).

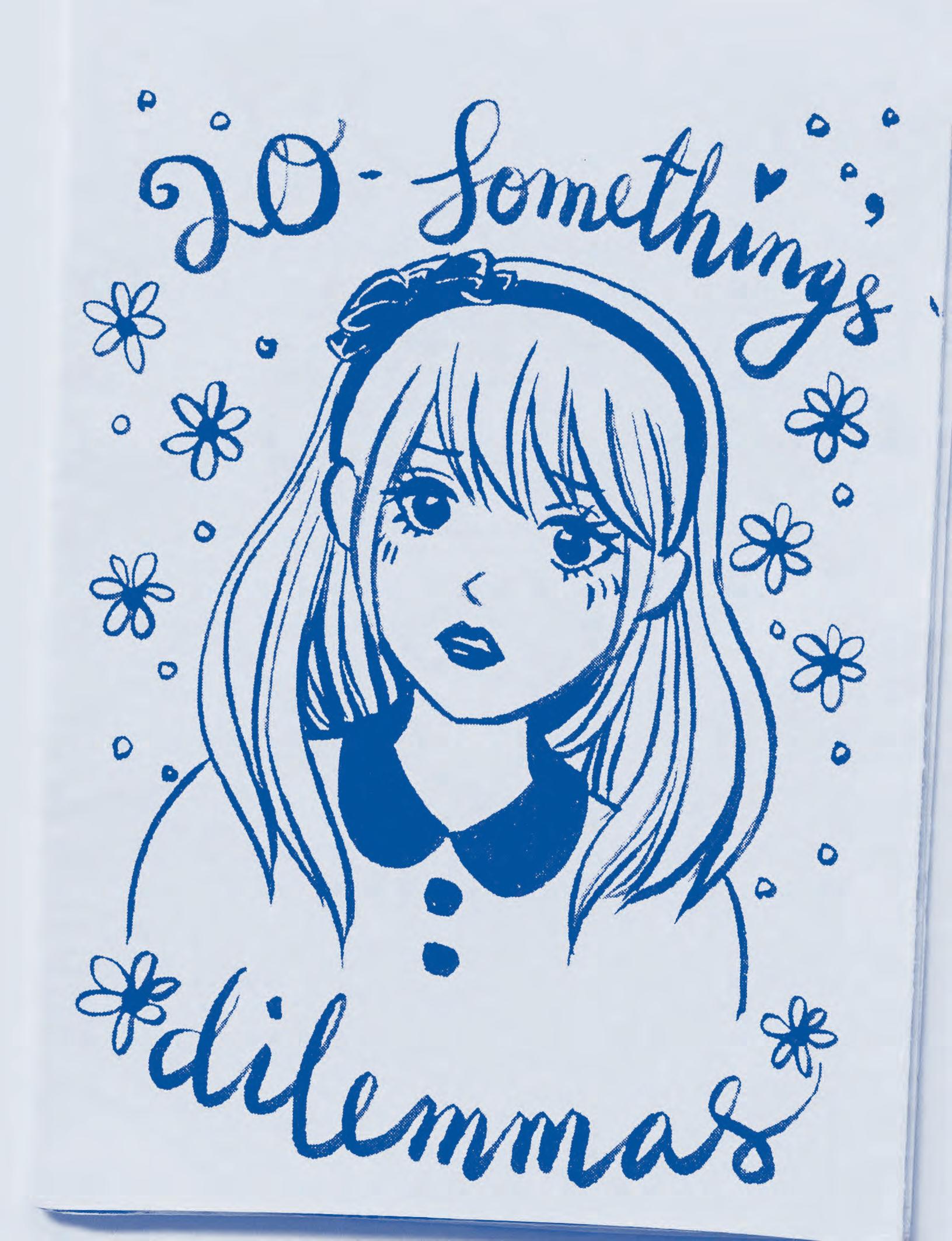

150. 20-Something’s Dilemmas, Chloe Or, A7, 2017. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

Twenty-tens to -twenties Zines

Mieke Montagne I like to mispronounce

Liam Goulter When I was 15 I volunteered at The Freedom Shop, back when it was on Left Bank off Cuba Street. I didn’t really care about politics at the time, but my friend was really into animal rights and there was animal rights stuff happening there. So I tagged along with her when she volunteered. They had a whole bunch of zines about stuff that I didn’t really know about. One of them was about polyamory, and I bought it because I thought it would be cool to leave it at my house to piss off my mum.

Murtle Chickpea There were about 20 of us in the 91 Aro Street collective. We each paid 10 bucks a week to do whatever we wanted with the space; people would have exhibitions out front or sell their stuff from the shop out back. I remember looking at the zines and not quite getting them. One girl had written a zine about being unattractive and how she wore leather jackets and red lipstick to compensate. It made her feel powerful. I remember thinking ‘That’s weird.’ And someone else had made a photo comic about bike riding or something. I was like ‘Oh yeah, okay, is that what people do . . .?’ I still didn’t get it.

Years later I went to the mid-winter zine market and just went ‘Oh my god’, bought heaps of zines and then started making my own. I just lost my mind at that mid-winter zine market. Suddenly I just thought ‘Oh my god — zines are

amazing.’ I didn’t know that before. I’d also seen quite a few zines in the anarchist book shops in Melbourne, but they were all political, not my thing. I remember looking around at the people at the market and thinking ‘Oh my god, my crowd: everyone’s just a little bit wonky’, and I really liked that. I talked to a guy who had this zine about being awkward, we just talked and talked. I would do a lot of talking and buying zines and then I’d go to the next stall and talk and buy zines. My friend and I went out for beer afterwards at the Southern Cross. We were reading all our new zines and it was like something had just gone click! ‘This is what we should all be doing.’

Liam Goulter The Freedom Shop seemed like the waiting room at the GP’s; all of those flyers like ‘Want to Stop Snoring?’, but in this case geared toward anarchist thought. The publications were really cheap-looking, in a way that I found very cool. They appeared to be made by people rather than institutions, but people I was probably a bit afraid of.

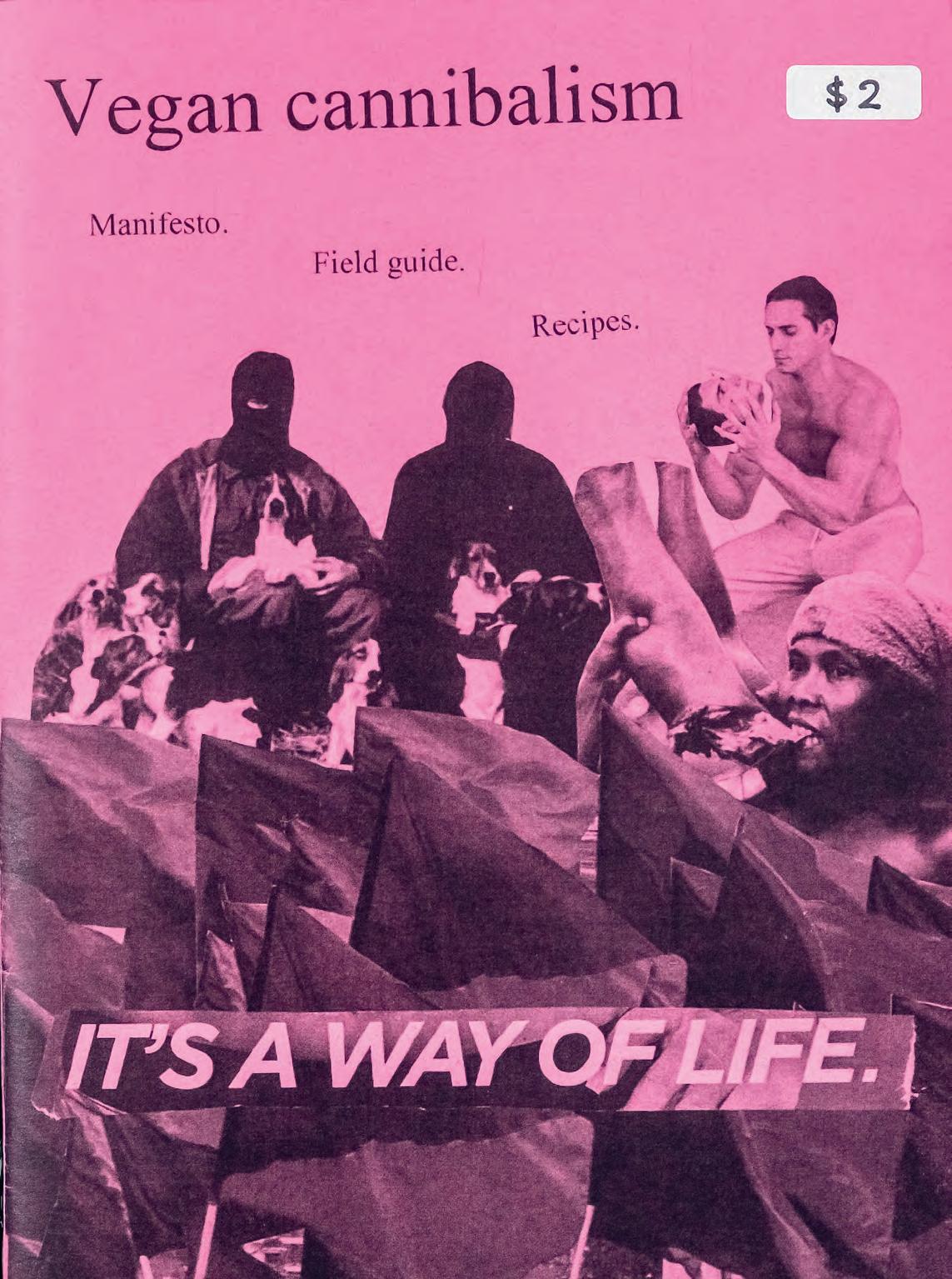

152. Vegan Cannibalism, Callum McDougal, A5, date unknown. Kirikiriroa Hamilton.

Maya Templer Yes, my dad’s an illustrator, and I definitely credit his influence. We would watch heaps of cartoons together, especially Cartoon Network stuff, and he’d show me the cartoons he liked when he was a kid. They’d be on YouTube. I’d stay at his house every weekend or every second weekend, and we’d just hang out and watch cartoons and do art. In the British show The Mighty Boosh, one of the main characters, Vince, makes comics about Charlie the bubblegum monster, so we started making comics about Charlie the bubblegum monster. In the show they would say ‘Oh, we put them in Weetabix packets in the supermarket’, so my dad said ‘Yeah, we can put them in the Weet-Bix packets.’ I don’t think we ever did, but when I was a teenager I’d print comics and leave them for people to find. That was probably inspired by that.

Helen Yeung There’s an early Riot Grrrl zine for feminists of colour called Slant and it really resonated with me, even though I could only see some of its pages on Tumblr. There was a lot of cool punk imagery and comic-book imagery. The person who started Slant is Mimi Thi Nguyen. She’s Vietnamese and is based in the States, where she’s a professor. Her writing about zines and girls of colour is really good.

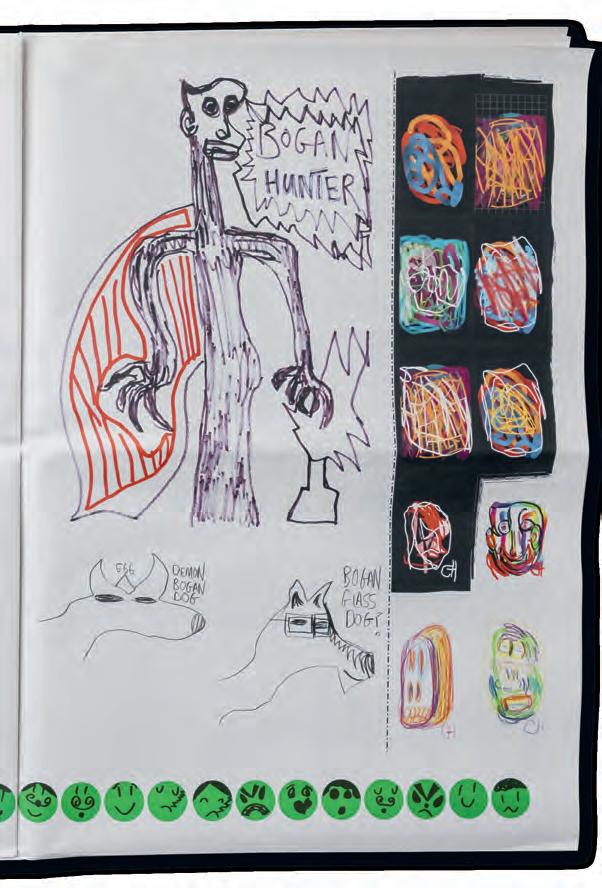

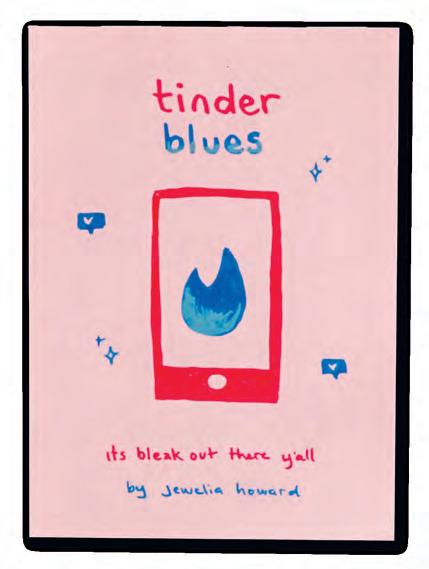

Jewelia Howard I found out about zines through the emo pop-punk scene on Tumblr. I made a lot of friends in that scene. You talk about your other interests, so zines come up because it’s that kind of scene. It wasn’t like sitting down and having a conversation about zines, it was seeing it mentioned and being like ‘Okay, what is this?’ Bookmark it in my brain to come back to later. I followed up by getting some books about zines out of the library. I remember thinking ‘What the fuck are these things?

I didn’t find out about Auckland Zinefest in time, but I was moving to Wellington and remember being really, really excited that I was going to get to go to my first zinefest and see zines for real. By then I’d already bought my first art zine off Etsy. Well, maybe it’s not a zine but more a small art book. I still have it.

156. Winter cover and spread, Maya Templer, 105 x 105mm, 2022. Ōtautahi Christchurch.

157. The Dawn of Comic Planet, page by Colin Harris, Māpura Studios comic group TV Competition: FutureFutureFuture, A2, 2019. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

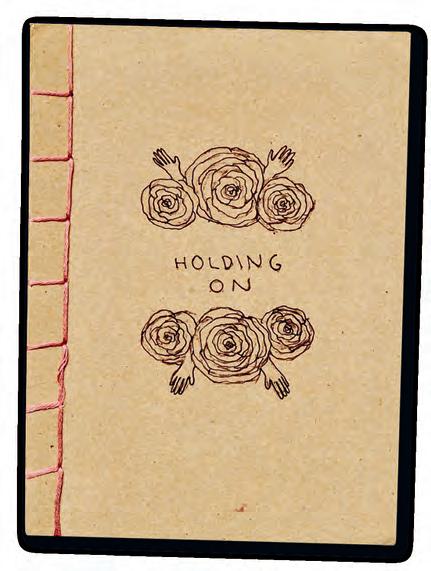

158. Holding On, Jewelia Howard, A6, 2015. Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

159. Tinder Blues #1, Jewelia Howard, A5, 2023. Te Whanganuia-Tara Wellington.

Tim Danko We moved back to Auckland from Great Barrier Island around 2010. I did my master’s, and toward the end of the degree I started volunteering at Māpura, because Stefan Neville was working there. I went to an open day, was seeing the work that was being done in the studio and was just like ‘Oooooh’. I had an inkling that this was going to be the kind of artwork that I was interested in. After about a year of volunteering I started working in open studio sessions, and there were people doing comic work and comicrelated work that ticked all the boxes. This was the stuff that I’d been reading about since my bachelor’s. When I did my master’s, there was even more engagement with the critical theory. That was really cool. At Māpura I thought ‘Man, these guys are being what the theory is talking about.’ Eventually, after a couple of years, the director of Māpura said, ‘We’ve got all these guys doing comic work. Do you want to start a comic group?’ So Stefan Neville and I started the comic group TV Competition: FutureFutureFuture. You’re actually meant to say the ‘future’ repeatedly until it collapses in on itself. Futurefuturefuturefuturefuturefuture . . .