Lotus

Lilly Metom

Kazuhito Takadoi

Alfred Russel Wallace

Paramat Leung-on

Dhruvi Acharya

Pallavi Narayan

Karla Knight

Sujata Setia

Minnie Evans

Mohana Gill

Lilly Metom

Kazuhito Takadoi

Alfred Russel Wallace

Paramat Leung-on

Dhruvi Acharya

Pallavi Narayan

Karla Knight

Sujata Setia

Minnie Evans

Mohana Gill

A Quick Word Editor’s comments

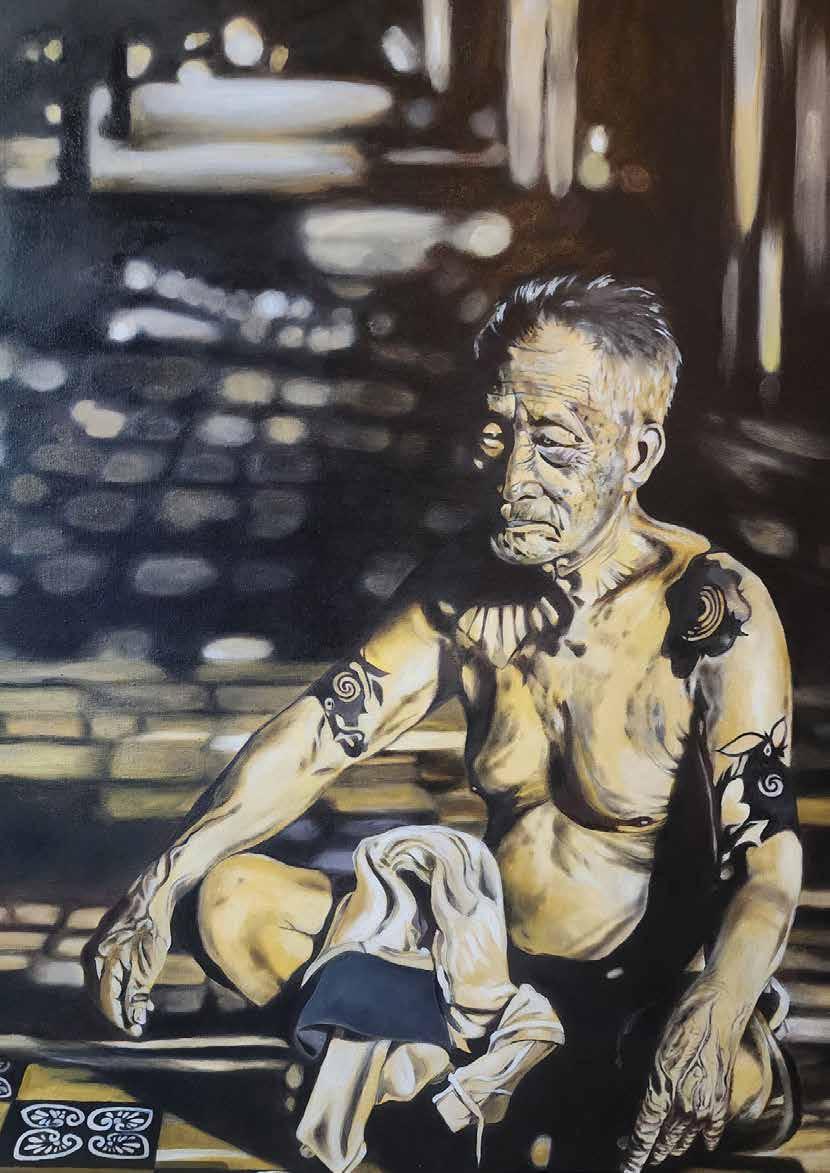

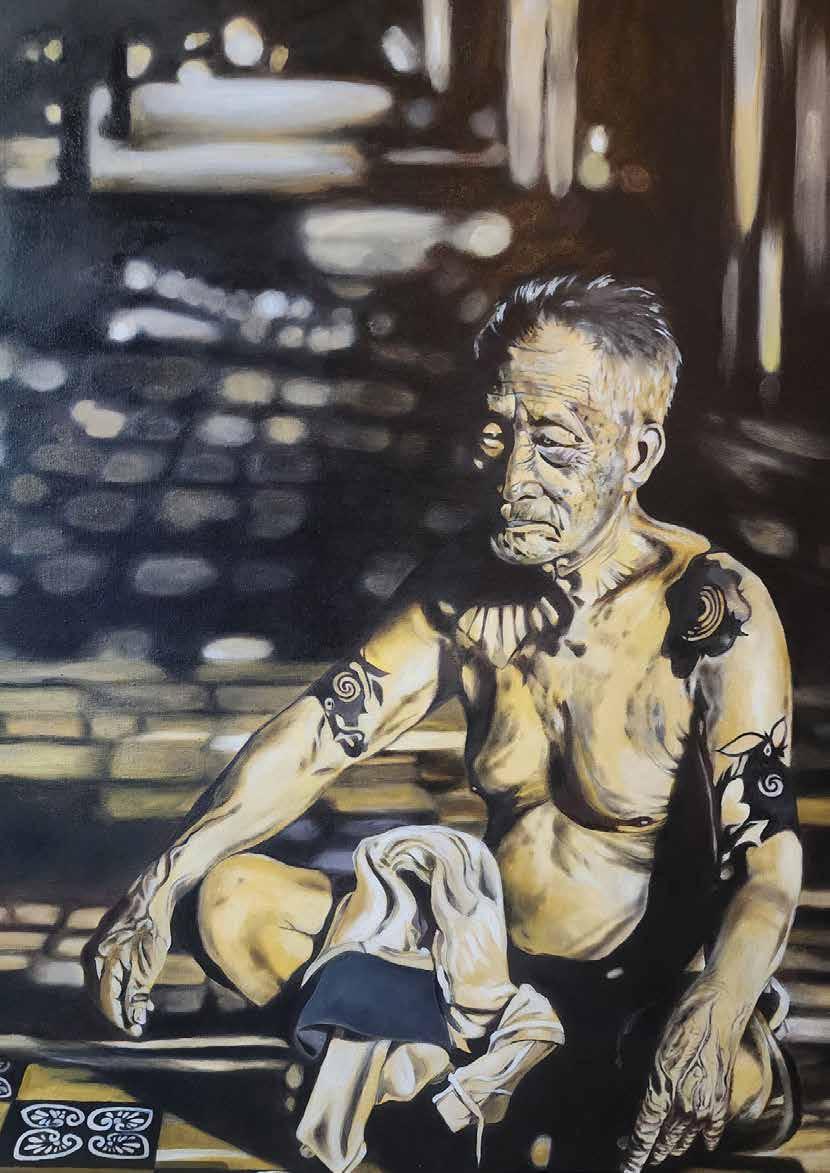

Lilly Metom Sarawakian artist, Malaysia

Longhouse, Sarawak, Malaysia

English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator

Project Khwaabgaon’ (already running for 8 years) now at the village of konedoba, India

Meditative paintings from Thailand

A book in parts by Martin Bradley

Psychological and emotional aspects of an urban

p98

Pallavi Narayan Poems from Malaysia

Karla Knight

p102

p116

Visual artist born in New York City and currently living and working in Connecticut

Sujata Setia A Thousand Cuts

p126

p138

Minnie Evans

Visionary artist from the USA

p142

Moringalicious Moringa The Tree of Life with Mohana Gill

Mohana’s Myanmar Cuisine Burmese cuisine

p152 Sarawak Indigenous cuisines

WELCOME BACK TO THE BLUE LOTUS MAGAZINE.

As we slide towards Autumn we present an amazing collection of goodies from Asia and lands beyond. Delight in this issue’s mix of new abstractions and other ‘Spiritual’ creations.

Thank you, as always, for reading. Submissions regarding Asian arts and cultures are encouraged to be sent to martinabradley@gmail.com for consideration.

Take care and stay safe

(Martin A Bradley, Founding Editor,

UK.)

Lilly Metom was born in Serian, Sarawak in 1973. She is a self-taught artist.

Lilly studied TESL (bachelor’s degree) and English Language Studies (master’s degree) at UKM, Bangi, Malaysia, and is currently teaching English at Universiti Teknologi MARA, Samarahan Campus, Sarawak.

She is a member of Sarawak Artists Society. Her favourite mediums are oil and watercolour pencils.

London, 1952. Young man Hamid, adrift from his studies and from himself, uncertain of his future and that of Malaya, not yet a country. He wants to belong to something but is it to his Sultan, to a barely imagined nation or to the British Empire? The answer, he believes, is to find a wife.

In the Great Smog, he meets Tom Pelham, an old friend from Malaya and son of a former British Resident, who invites Hamid to spend Christmas at his family estate. Excited, Hamid anticipates reuniting with his childhood crush, Clare Pelham, only to be met with another pleasant surprise: Clare’s two competitive friends, Hermione and Margaret. Hamid finds them as exotic as they find him. Caught in the middle of the three women, Hamid does the unthinkable, loses Clare’s trust and is thrown out of the house. But all is not lost. Tom offers Hamid a route back to redemption and to Clare—if he spies for England.

Cold War Berlin, 1953. Hamid is sent to seduce an East German communist student leader.Abandoned in East Berlin when it is sealed off during a violent uprising (unknown today outside Germany), Hamid must save himself from Soviet tanks and rely on the unknown loyalties of a Soviet Colonel and especially on the wits of his mistress, loyal only to herself. Hamid must cross the final bridge to safety, to adulthood and to belonging to something, or to someone.

Paperback / Hardback

Published: Mar/2025

ISBN: 9789815233858

Length: 352 Pages

Kam Raslan is a Malaysian writer and broadcaster. Originally a film-maker working in London, Los Angeles, Malaysia and Indonesia, he has written for many publications including The Economist, Mekong Review and he had a long-running column in The Edge Malaysia. He hosts two shows on BFM Radio: A Bit of Culture and Just For Kicks. Kam Raslan is the author of ‘Confessions of an Old Boy,’ a collection of short stories, the various adventures of Dato' Hamid from the 1940s to the 2000s. The book was first published in 2008 and has been re-issued in 2024.

The grey, Malaysian-made, Perodua Bezza SUV skipped neatly between Selangor State’s raindrops as I was shot towards KLIA (Kuala Lumpur International Airport) 2. I was hurrying to wait for my flight to the Land of the Hornbills - jungle-blessed Sarawak, situated on South East Asia’s large island of Borneo (743,330 km2).

Gibson, gastronome, friend and driver, regaled me with stories of Sarawak’s indigenous festival of Gawai and, alternatively, of the indigenous food found there. I also learned of the amount of different cakes in one Penang island cafe (China House, 20-30), and of succulent pork stews. After which, satiated by the mere thought of food, I closed my eyes for the remainder of the cab journey.

After the stop and go of boarding passes and passport checks, I was allowed the respite of the American-owned Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf’s Jalapeño bagel with cream cheese. It’s become a favourite go-to. No KFC, McDonald’s or Burger King. I prefer the kick of the green Jalapeño pepper and the crispness of the toasted bagel coupled with its internal softness of cream cheese. In London’s East End, I enjoy Bagel Bake and its genuine Jewish bagels with gravlax (Lox or Lax) but in Malaysia Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf has to suffice.

Only when my bagel arrived, it was plain. The Jalapeño slices had clearly been removed by some secretive pepper aficionado. I resolved not to let that spoil this breakaway.

After a briefly delayed flight, said aircraft’s successful landing and a half-hour Grab trek, I arrive at the Equatorial Hotel (not its real name), in Sarawak’s capital of Kuching (cat in Malaydon’t ask). My room faced, well, nothing, and

was minute. I brought this to the attention of the hotel. My new room was opposite a small jungle which I am sure watches back. I thought that I saw a monkey. It could have been a combination of leaves though. Nevertheless, I had let my fantasy monkey exist in the spirit of détente.

My delayed lunch was Ubi Cauli Rice and Nasi Lemak Ayam Masak Lemak Cili Api at Indah Cafe, a rustic eatery conveniently near my hotel, but sadly not so convenient as there’s a distinct lack of WiFi.

My late lunch rolls into an early dinner at Lau Ya Keng food court, where I order stir-fried mixed meats with yellow noodles, and a mug of Chinese chrysanthemum tea. The simple eatery rests opposite the Teochew Hiang Thian Siang Ti Taoist (Daoist) Temple, which was all lit up with orange, not red, lanterns radiating in the fading daylight of Kuching’s Chinatown.

Kuching town, after dusk, was quiet. It had not been quite what I was expecting at Gawai festival time. I had been looking forward to street decorations, pizzazz and Sarawakian fuss. What I got was a drizzle of quite expected rain, which drove me into a Grab (taxi) and transported me back to the hotel early for an evening alone with my thoughts, Lipton tea and social media on my phone.

The next day was my big trip to a Bidayuh longhouse, 60km and an hour and a half away outside of Kuching city, in the Padawan District of Sarawak. It was near Malaysia’s border with Indonesia, at Kalimantan, and was in a rainforest estimated to be 140 million years old.

In the bright, early, morning - daylight blasted into the hotel curtains early in Sarawak, my paidfor breakfast devolved into toast, kaya (coconut

jam) and butter. It seemed to be the fault of the morning chef, who was more than an hour and a half late for his shift. Outside the hotel, the constant drizzle of rain further dampened my expectant, and hungry, spirit.

I ‘WhatsApp’ texts to Danny, my potential tour guide.

“Hi Danny”

I heard a sound nearby, in the Reception area of the hotel.

A young Chinese-looking man, dressed for hiking in a dark blue long-sleeved shirt, long trousers with ample pockets, jungle trekking shoes and sporting a floppy Noslife hat, checked his phone.

I, on the other hand, was wearing my thin cotton Marks & Sparks blue shirt, thin black trousers and Laird of London black fedora. I walked over to the potential Danny.

“Danny?”

“Martin?” Replies Danny Chan.

It was like the awkwardness of a first date.

Danny was before time at the hotel, and said so.

“ I’d much rather be a few minutes early, than late” Danny explained.

Danny being early allowed me to grab a quick couple of roti cannai at a nearby Mamak eatery before we launched into the green, green hills sheltering Sarawak’s indigenous peoples, and their homes.

Through long and increasingly winding roads which obviously lead, eventually, to someone’s door, the persistent greenery had a distinct lulling effect on my consciousness. I slept through the twists and turns of quite majestic mountains’ foothills and an increasing vert jungle, and only awakened to Danny’s alert to the approaching destination.

“Sorry to disturb you, but we’re practically there, at the longhouse. Tired?”

“Didn’t sleep too well last night.”

“That happens to me in unfamiliar places. Anyway, we’re here.” Said Danny as he stopped the car in a small rustic car park, at the edge of a forest.

The Bidayuh Longhouse was true to its name. That is to say that it was long. Unlike Iban longhouses, which still exist further into the extensive jungle, the Bidayuh version appeared to be more of a terraced house situation, with adjoining houses rather than one long house with multiple doors and multiple occupancies.

It was quiet too, perhaps because of the Gawai Festival celebrations at the weekend. That celebration was happening after I was due to return to Sarawak’s capital of Kuching, and re-visiting some Bidayuh friends.

There is a word ‘ Biannah’ (in the Bidayuh language) meaning ‘people of Annah Rais’. ‘Rais’ means kampung/village and ‘Annah’ is that kampung’s name (after the nearby river).

Danny led me up, on what appeared to be ageing wooden, moss-graced steps and through the practically haunting bamboo walkways. At first, I had difficulty walking there. The dried concave bamboo culms seemed hard against my street slip-ons.

In time we passed numerous houses, perhaps as many as eighty, some were antique wooden constructs, but many were more modern concrete and/or brick built. I noticed few people in evidence, but scores of cats.

All my romantic, and evidently quite mistaken, imaginings of friendly indigenous individuals vying to shake my hand, were dismissed. It was decidedly not any sort of Kipling’s ‘The Man Who Would Be King’, no greeting of long lost kin of the once royal Brookes family. Instead, the Longhouse ambience echoed the greying clouds gathering over the nearby tropical rainforest. And, there was not an iconic hornbill in sight.

Karum, the Indigenous Bidayuh owner of the homestay (no.67) I had booked to stay the night in, greeted me. She evinced unforced affability and a smile to melt even my hardened heart.

The weight of my journey dissipated as I took a quick nap on the mattress provided on the floor of my small room. There were no frills, no air conditioning even. A standing fan moved warm air from one side of the room to another, reversed and moved it back.

At the rear, there was a wooden door. It led out to a balcony and an outdoor space which looked out to the dense greenery of the nearby

jungle, and the teh tarik coloured Sememdang river. The green of the nearby foliage and the watery sounds washed away my slight irritation with the seemingly abandoned abode. I snoozed.

Karum prepared a wonderful indigenous repast, which I eagerly ate. Later Danny led me through the main bamboo passageway of the longhouse, climbing down wooden stairs, past penned ducks, tiger-striped cats, and strutting cockerels, to a hexagonal wooden hut.

“Do remember that, historically, the tribes here were known as headhunters. This is the Bidayuh Baruk. It has the human skulls of the previous enemies of this community, hung in their headhunting days. It was a place for the warriors to gather and talk.” Danny explained.

In the dimmed wooden hut, I plainly saw the hexagonal wire mesh enclosure. It contained blackened human skulls just like the ones I’d seen the year before, in the educational ambience of Kuching’s Borneo Museum. In the longhouse environment, the poignancy of the dried heads seemed more ‘real’ if such a thing is possible. I was completely unperturbed by the sight of the heads. My curiosity too was dialled down. My recent research had taken the surprise out of the situation. I was, however, hot. Sweating into my hat and shirt.

Night and dinner came. Karum had outdone herself by presenting yet another amazing indigenous meal. And in the dewy, mist-laden morning the brown river gurgled as freshly awakened exotic-sounding birds sang to welcome me to the jungle.

Breakfast was early, brief and I felt hurried as more guests were due to arrive before lunch. I was, once more lulled into sleep on the return journey.

Danny, bless him, awoke me as we approached 96 Street Noodle shop. He wanted me to try the (in)famous ‘Fresh Fish Mee Soon Soup’. Which was every bit as tasty as he had described in the car park, before entering the establishment.

Ed

Having finished my studies at Hokkaido Agricultural and Horticultural College at Sapporo, Japan, I moved to the U.K. to further my studies at The Royal Horticultural Society at Wisley.

From the U.K. I went to the U.S.A. for a year, studying at Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania.

In 1999 I returned to the U.K. to work in a large private garden. I then enrolled at Leeds Metropolitan University from where I graduated in 2003 with a BA hons in Art and Garden Design.

Nature is both my inspiration and my source of material, which is provided in abundance from my garden and allotment. There are no added colours, everything is simply dried then woven, stitched or tied.

To me shadows are an important dimension to my work and as the light changes or the point of view is moved, so the shadows will create a new perspective.

Because the materials I use are un-dyed the colours may alter with time adding another layer of interest.

I’d freshly returned from a stay at the Bidayuh longhouse, at Annah Rais, Padawan, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia. On arrival back to Selangor, in peninsular Malaysia, my attention was drawn to a notice of a talk being given at Ilham Tower. The talk was advertised as ‘An Artistic Pilgrimage Retracing Alfred Russel Wallace’s Journey in Sarawak’, a talk by Chang Yoong Chia & Ming Wah. It was part of the on-going series of talks called ‘Ilham Conversations’, at Level 5, ILHAM Gallery , Ilham Tower, Kuala Lumpur. I was interested in the talk as a pleasant reminder of my two visits (so far) to Sarawak, and a reminder of my excitement concerning being in Kuching - the land of the hornbill.

Chang Yoong Chia & Ming Wah’s talk gave an overview of the English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator Alfred Russel Wallace. He stayed in Sarawak from 1854 to 1856, writing his seminal paper ‘On the law which has regulated the introduction of new species,’ also known as the ‘Sarawak Law’.

Towards the end of their illumination, the couple broached the subject of creating a ‘Graphic Novel’, about Wallace, and revealed some initial artworks concerning that project.

Before the talk, and between that event and my coming back to Selangor I’d read

Wallace’s ‘The Malay Archipelago’, as well as several biographies regarding Alfred Russel Wallace, and was more than alarmed at his casual slaughter of Sarawak’s ‘Old Man of the Forest’ (aka Orangutans) related in ‘The Malay Archipelago’ (Published 1869)…

“About a fortnight afterwards I heard that one was feeding in a tree in the swamp just below the house, and, taking my gun, was fortunate enough to find it in the same place. As soon as I approached, it tried to conceal itself among the foliage; but, I got a shot at it, and the second barrel caused it to fall down almost dead, the two balls having entered the body. This was a male, about half-grown, being scarcely three feet high.”

For me it brought up the distance in time between Wallace in the 19th Century and myself existing in the 21st Century, as well as the distance in practical ethics. It is an irony then, that he had also written in ‘The Malay Archipelago’…

“It seems sad, that on the one hand such exquisite creatures should live out their lives and exhibit their charms only in these wild inhospitable regions... while on the other hand, should civilised man ever reach these distant lands... we may be sure that he

will so disturb the nicely-balance relations of organic and inorganic nature as to cause the disappearance, and finally the extinction, of these very beings whose wonderful structure and beauty he alone is fitted to appreciate and enjoy..”

Alfred Russel Wallace was responsible for the demise of at least 29 orangutans, male, female and young. Of course that is not to mention the hundreds of other species that he ‘collected’ in South East Asia and, before that, in the Amazon. Wallace collected in the 1850s and Hornaday in the 1870s; then there was the adventures of Tom Harrison fighting the Japanese during the Second World War, and the Sarawak Museum collections.

“Orangutans in Borneo were first mentioned in western records in the 1600s with Jacobus Bontius and Nicholaas Tulp being probably the first few to use the scientific term orang-utan in 1631 and 1641 respectively. There were several variations used, Orang Utan, Orang-outang, and Orang-autang (page 275, Nicolai Tulpii Amstelredamensis Observationes Medicae, 1641, Book III, 56th Observation, or page 284 of the same book under the Google books.

Orang-utans became such an attraction that by the end of the 1800s, over 200 orangutans were exported to Europe from Sarawak (Bruen & Haile,1960) by early 1900s. A separate 1950s survey by Harrison (1961) estimated that a further 125 orangutans (minimum) were in captivity of orangutans in private hands in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, a global estimate by Zoological Society of London in 1960 estimated that there were at least 248 orangutans in captivity in zoos worldwide (Harrison, 1961).”

(Moving towards zero losses of orangutans and their habitats in Sarawak, Conference Paper · December 2014)

Orangutans, today, are more under threat than ever, despite being an official endangered species.

Ishita Roy

Jan 5, 2025

Located 4km from Jhargram town, Lalbazar is a small village of less than 100 people. This is where Mrinal Mandal, an art graduate and teacher saw the potential of the kind of art which could reach a global audience. Indeed, with his hard work and efforts, the village which was unknown until a few years ago, has not only gotten an identity, but is now a project that aims to transform many more such villages of Bengal.

A graduate of Govt. Arts College in Kolkata, an art enthusiast himself, Mrinal Mandal was just looking around for traditional art when he found out about Lalbazar. The residents of a village Lalbazar, which was nondescript until a few years ago excel at local arts and crafts. In fact, Mandal himself was fascinated by the raw beauty of the way they created their art.

Mandal's Journey To The Art Hub Located 4km from Jhargram town, it is a small village of less than 100 people. This is where Mandal saw the potential of the kind of art which could reach a global audience. With this thought, he made this place his second home. Then, with the help of Chalchitra Academy, an artist's initiative in Kolkata, he conducted art classes for the people. Experts from several other districts were brought in, too.

These local artists from Lalbazar were able to showcase their art during the Indian Museum and the Behala Art Fest. The art was represented by an all-women team of 7, who too were fascinated to have a look at new art forms and massive installations. This team painted two walls and their work was appreciated by organisers, fellow artists, including those from abroad and visitors. It seems that the art truly reached a global audience.

As a token of honour, the village Lalbazar also earned the name Khwaabgaon or Dream Village, for the girls who dared to dream.

This led to a huge excitement and encouragement for the artists who, a few years back were not even known, neither were their village was descripted. This is what gave them and their village a new identity, turning Lalbazar into an art hub!

At the Indian Museum, Khwaabgaon participated in From Fields to Folk: A Journey Through Rural Heritage. They put up dokra works and wooden handicrafts.

The step forward

These villagers are now trained in kutum-katum, a traditional handicraft made from twigs and roots, dokra, kantha stitching, pottery and wall painting. They are being visited from nearby villages and are also paid to buy local art. Not just income, but the village itself looks beautiful, with art featured on every wall in the settlement. As for Mandal, he wants to carry on with the project Khwaabgaon and transform 12 more such villages in West Bengal! The next in line is the village of Konedoba.

Mrinal Mandal has reiterated that deforestation is the main problem in India, and the rest of world. Due to deforestation, and mining, elephants are coming in villages and cities. They are destroying houses, eating villager’s vegetables and fighting with people - killing men and sometimes being killed by men.

Recognition of this has prompted a fresh need for ‘Elephant Awareness’ unfortunately without government or corporate support. Wall murals and the expansion of ‘Project Khwaabgaon’ (already running for 8 years) at the village of konedoba, in 2018. This is under the guidance of Mrinal Mandal and the Chalchitra Academy. They assist villagers to paint wall murals to help empower those marginal tribal people.

Konedoba is a predominantly Santhal village located in the Junglemahal region of India, specifically in the Jhargram district of West Bengal

Mrinal Mandal mentions that the wall-art includes lord Buddha’s birth to Mahabalipuram , Ganesh bandana, and chow dance.

His works are inspired by nature, its existence and importance. Therefore, his works are filled with many plants and animals, sometimes real and sometimes imaginary, in order to emphasize the importance of the integration of man and nature.

Paramat chose to train in traditional Thai painting techniques, hoping to preserve Thailand's cultural heritage. He devoted much of his early life to creating murals for temples across Thailand, dedicating nearly all of his time to the development of Buddhist temples. The meditative environment stimulated his introspection and reflection, and his paintings, which adorn the temple walls and contain stories and Buddhist teachings, laid the foundation for his later work.

His work is also inspired by nature, its presence, and its importance. Consequently, his paintings are filled with plants and animals, sometimes real and sometimes imaginary, to emphasize the importance of the unity between man and nature.

Such ideas and influences converge into one, so there is a very unique style in his works, which is highly complex yet melodious, bold and tranquil, like a depiction of the heavenly world.

A book in parts by Martin Bradley

To all intents and purposes Kuala Lumpur (KL), in English, means ‘muddy confluence’ - Kuala being the point at which two rivers join or an estuary, and Lumpur meaning ‘mud’. There’s other explanations of that city’s naming, but the above seems to be the most commonly used.

In his ‘A History of Kuala Lumpur, 1857-1939 / J. M. Gullick (Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 2000) had written...

“In 1837, Raja Abdullah of Klang with the support of his brother, Raja Jumaat of Lukut, sent eighty-seven Chinese miners from Lukut up the Klang River to open new mines. It would be necessary to supply food and other goods to the miners over a period of, say, six months while they excavated large pits to uncover the ore deposits. To meet these and other initial expenses, the brothers secured an advance of $30,000 from two Malacca Chinese towkays, Chee Yam Chuan and Lim Say Hoe. When the expedition reached the confluence (kuala in Malay) of the Gombak and Klang rivers, where the Jamek Mosque now stands in the centre of Kuala Lumpur, the men disembarked from their boats, and after some preliminary prospecting, they began to mine at Ampang, two or three miles from the point of disembarkation.”

Kuala Lumpur is a city overflowing with people, traffic and shops. However, there’s enough mystery and history for Brian Holland to discern that city’s obvious glamour.

Kuala Lumpur has slowly revealed herself to him in myriad colours emanating from the vibrancy of its multiple ethnicities and giving the city her life, her potency and her history too.

From the 1860s Kuala Lumpur had struggled to become a small tin town centred on the Ampang area. Later in the 19th C, under the colonising British, Kuala Lumpur had become known for her spectacular Indo-Saracenic (Moorish or NeoMughal) styles of architecture and an inherent hybridity which had shaped Kuala Lumpur as a city…

On Brian’s first encounter with Kuala Lumpur, dust had swirled on the Kuala Lumpur streets. The wind had picked up strewn scraps of local newspapers in its eddies and, as quickly, cast

them aside as if it were looking for something in particular. The eternal bright, blue, morning skies, dampened only by a seasonal rain, had watched over the nascent, arousing, city.

Complex architectures, developed over the one hundred and sixty years since the city’s birth, stretched its fingers high, sheltering infinity pools with their stunning city views and diverse ethnic, morning bathers. Yet, no matter how far the sky-scraping buildings reach, nor how many wallow in their new found luxury, they all seemed insignificant when compared to the magnificence of a god’s heaven.

That trip, Brian had slouched on the side of the ‘queen size’ bed, in his room with the sleazy number (69), in the Golden Dragon hotel, Petaling Street, Kuala Lumpur. It had been some distance, physically and financially, from skyscrapers and infinity pools, yet they drew ever nearer to the previous generations, and their luxury, ready,

one day to swamp them altogether.

Brian experienced the softness of the mushy worn mattress under his hairy, naked buttocks. The lurid green hotel bed-throw, felt coarse, shabby, under his flabby, dappled hand. His nude toes had nestled in the tousled, mismatched, pink mat, adjacent to an aged hardness of cigarette burnt nylon fibres and some petrified minutiae of chewing gum, both caked solid into that ancient hotel mat.

The twelve-by-ten hotel room had been feeling increasing claustrophobic as Brian sat, musing on one of the vile, scuttling monstrosities of city cockroaches. He had heard one’s pugnacious, filthy, shuffling, scratching behind the dingy room’s cupboards, where it’d scampered. That had been, quite literally, the price he had to pay, then, for a room on Petaling Street, in the centre of Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown.

From the peeling ceiling, the aphasic neon strip had thrown punitive blue light upon his middleaged frame. It had revealed to him his deathly grey pallor - a lumpish carcass, maltreated, flaccid. The archaic, flecked silver and black, mirror, had viciously revealed his visage.

He’d been taking time out.

It had been a well-deserved rest from the intrigues and bitchiness of the UK. Time out too from his former wife, their neighbourhood (Blicton0onSea) and the overall greyness that Britain had become under mealy-mouth Tories.

Brian Holland and time had, inevitably, moved on.

In the cold cobble, brick and concrete world of sea-side Essex, Brian had once successfully severed the bonds of his youth. He had reinvented himself from the working-class boy he had been, growing up on an apple farm, swimming and fishing in the rural River Stour to being a catering student in Blicton-on-sea. Through sheer perseverance, Brian had climbed out of his past into a future as a pastry chef then into writing about the culinary arts.

His marriage to the proverbial Essex Girl (Julie) had died. For some time Brian had walked alone, drank alone, down the East End’s ‘Young Prince’ pub, enviously watching young couples flaunt their youth.

His existence had weighed heavily. He hadn’t missed Julie. The last few months of that relationship, her betrayal - cuckolding him, had obliterated all the good that may have gone before. But he did feel something - unease

- a creeping ennui. Gradually, the notion of absenting himself had fostered itself.

Once his mind had been made up, Brian had quickly booked a ticket with Malaysian Airlines for the following week and, before he knew it, he had exited at Kuala Lumpur International Airport.

Being of reasonable intelligence, it had not been too difficult for Brian to find his way to the rail link to Kuala Lumpur’s Sentral Station and found his way to Pasar Seni station. From there he had hauled his suitcase along broken, narrow, pavements under a sweltering sun to the hotel, which only bore a vague resemblance to that advertised on the internet. Tired, sweaty and in no mood for chit chat, Brian had tendered his passport, got his room and cursed himself for my foolishness.

The Golden Dragon Hotel had hardly lived up to its illustrious name. The ramshackle building hid behind its history like a sore behind a bandage. Reception had been dank. It’d overtly smelled of cockroaches, and the corridors sported threadbare carpeting with hotel staff as surly as the roaches inhabiting it.

Brian’s room had been a twelve by ten, roach infested shoebox, and had been sans even the most minimal of comforts. He had felt as alone in Kuala Lumpur, as he had in Britain.

Sticky, hot, and uncomfortably moist Brian had dragged his ennui into the cupboard which doubled as the hotel bedroom shower. He could clearly see his fifty plus years reflected in the stained and discoloured bathroom mirror. He’d witnessed his jowls sagging, his anaemically pale skin looking soft, dough-like and, to himself - repugnant. The effect of the forceful shower had eventually brightened his spirits and, after towelling off, he’d managed to catch the spurious internet WiFi which, at times, had appeared as elusive as fame.

Four year later, and with an entirely renewed mindset about Malaysia, Brian Holland has, slowly, become familiar with the swelteringly damp city of Kuala Lumpur, whose many colonial buildings face down the sun and give shade to heat-ridden pedestrians beneath their well-formed arches.

Carefully crafted brick pushes up and carves majestic places within the city’s skyline but, increasingly monstrous office buildings and newly made Art Brut architecture have begun to overshadow those previously glorious edifices

of Indo-Saracenic design.

Sadly, in a city where little architecture is aged, many older buildings have been savagely torn down to make way for the newer and most unremarkable rectangular structures.

The hundred year old Kun Yam Thong Buddhist temple disappeared in 2000; the luxuriant Eastern Hotel (1915) – believed to be Kuala Lumpur’s first hotel, and Chua Cheng Bok’s - Bok House (1929) are further examples of Malaysia’s wanton heritage destruction. Kuala Lumpur is not alone in Malaysia’s blatant disregard for antiquity. Prime buildings in Penang and Ipoh have also fallen into dereliction, or have been torn down to be replaced with car parks.

In place of graceful colonial buildings, Malaysia has raced with Dubai, Taiwan and China (and lost), to house the world’s tallest buildings. Kuala Lumpur’s Petronas Twin towers now rank ninth and tenth respectively in the height stakes, as they had risen themselves up on that city’s skyline like some elderly aunt’s forgotten knitting needles.

In Kuala Lumpur, other architectural additions smacked of the modernity that is painting the city with a shock of the new. It has been a confused city, not totally Eastern but not Western. Kuala Lumpur seems to be caught between MTV, McDonalds, and Starbucks on the one hand, and a former Prime Minister’s ‘Look East’ policy on the other.

Brian has languished a few months in Kuala Lumpur amidst the heat and the traffic fumes, trying to discover the authenticity he knows is there, but which seems to lay just beyond his reach. He drags his moist body to and from the local light rail transit system (LRT) at Bangsar, and heads for heritage buildings which, on discovery, have been rendered to rubble. Giving up he seeks the ex-pat haven of Bukit Bintang (aka Star Hill) and other malls in and around that city.

In the older malls of Bukit Bintang, such as Sungei Wang Plaza, Brian purchases less-thanlegal DVDs of films or TV series he only vaguely wants to watch. He scowls when they either don’t work, or are of such poor quality that he would be better off just giving his money away to one of the many street beggars around KL’s China Town. Brian’s lessons are slow to learn, but the LRT (Light Rail Transit)and Monorail keep him busy.

Somewhere, at the back of Brian’s still very Western mind, is a nagging thought “surely this isn’t all there is”. He remembers, from his earlier visits that there’s a whole country out there somewhere. In the states of Kedah and Perak there are jungles, forests, parks, and cooling, tumbling, waterfalls with large rocks to lay upon in the excitement of rurality. He knows that Kuala Lumpur is not the sum totality of Malaysia.

When Brian gathers enough courage, he loans a car (an old Malaysian-made Proton Wira) and begins to drive. Driving in Kuala Lumpur isn’t quite as daunting as he’d first thought. However, he has to throw away any notion of a British Highway Code and, instead, watches and learns how the locals behave on the roads, then follows suit.

The concept of lanes, queuing, and signalling seems to be as equally foreign as is the concept of giving way. Though Malaysia is not quite as bad as India with its every man for himself and cows are king (queen?), but ‘might is right’ does seem to be the Kuala Lumpur street mantra.

In Malaysia, the bigger the vehicle the more respect you seem to get.

Brian soon discovers that motorcycles deserve little respect. In the Malaysian traffic mindset two-wheeled motorised vehicles are but mechanised insects, whereas pedestrians have even less rights on Malaysian roads than motorcyclists, which is to say that they have none whatsoever. Malaysian roads are designed for motorised four-wheeled vehicles not, emphasise not, for people who cannot or will not protect themselves with copious amounts of metal and power.

Frequent road diversions lead Brian away from the main parts of the city and its one-way systems. He frequently gets lost and find himself literally miles from where he’d expected to be. The plus side of being lost is that he ‘discovers’ completely new areas of Kuala Lumpur.

Eventually, with the tarnishing penny slowly sinking in, Brian Holland realises that all roads lead not to Rome, but to Kuala Lumpur City Centre (KLCC). With that realisation, getting lost is no longer a chore. Brian saunters away his days swimming along the one way system, traversing the highways and byways and still, eventually, heads back to the small section of Kuala Lumpur where he is laying my head.

Brian has discovered that Kuala Lumpur has many notorious areas, but none as notorious as

Lorong Haji Taib in the Chow Kit area has been.

Chow Kit was named after the wealthy Chinese tin entrepreneur Loke Chow Kit. Yet the Chow Kit area had become famed for a certain type of purveyor of the world’s oldest profession. Because a conventional work environment had been frequently hostile, sex work has become one of the few opportunities for certain types of humanity to feed themselves.

Brian had never been in Chow Kit in the evenings – that’s when the sex workers ply their trade. Walking around Chow Kit in the mornings Brian notices the ‘girls’ easing out of the night and into the (for them) early mornings – 9-10am. Like freshly awoken cats, they stretch and yawn on their doorsteps as he passes, barely able to purr a good morning, but attempting to anyway as they light their first fags of the day. Brian waves a cheery wave to them – from the opposite side of the road - as there’s no need to get the ladies’ hopes up so early in their collective mornings.

When Brian doesn’t drive in Kuala Lumpur, he uses the LRT or the monorail (for its air-con). He likes the way the rail system cuts through the traffic build-ups and eases the parking problem. He’s found many places are accessible using the rail systems. He’s also noticed that there are short walks where he can link one system with another. The concept of linking different rail systems together via networked tunnels seems a little alien in Malaysia, as opposed to sublimely networked ‘undergrounds’ in other cities.

Many of KL’s malls are outside of the LRT/ Monorail systems, and only accessible via taxi or private vehicle. With his sense of direction they are quite beyond Brian. One, a slightly older mall – the Mid-Valley Mega-mall, built in the same year as the Suria KLCC (1999), is accessible via a train link (KLM) from KL Sentral, also via bus link from Bangsar LRT station. It has become Brian’s cool haven.

Ultimately, there is only so much citywatching one foreign man can achieve before the streets begin to pall. Getting lost looses its charm and the delights of the city are leaving him, not cold, for he is never cold, but wishing that he could see green, smell unpolluted air and hear less traffic.

The move from Bangsar to Wangsa Maju is, relatively, plain sailing and is much needed to give Brian Holland a fresher perspective on life and his adopted city.

My work focuses on the psychological and emotional aspects of an urban woman’s life in a world teeming with discord, inequalities, gender disparities, violence and environmental catastrophes. Often utilizing a subtle, dark and wry humour to address these troubling issues, I also reflect on the hope, empathy and courage that exist in our minds, creating works that are visually and psychologically layered.

My work is based on my drawings, and my sketch books are like a daily journal – a chronicle of my thoughts, observations, emotions and experiences. In my work I create a world where thoughts are as visible as “reality”, where human forms morph to match their mental state, and comic book-inspired empty thought and speech bubbles convey ineffable emotions. The protagonists in my work populate a world where past memories, the present, and imagined futures can all coexist.

However when the works are viewed, I hope that the myriad detailing lures viewers to reflect on their own experiences and sentiments, making the specifics of the stories and the meaning of each image unimportant and allowing for the contemplation of our shared human existence

As the world burns-angel

by Pallavi Narayan

In a lantern carriage she careens Across the strip from Sungei Melaka To Jonker’s shore, a veritable Cinderella Caught up in the furore of the market At night. It is lit and from her coach She waves, in her own estimation a Brown princess gracing the colonies. Her irreverent musings interrupted with “Are you here on work?” the rickshaw Cyclist’s enquiry. She nods no, she’s Here for the long weekend. “Wah, Coming from Singapore, issit?” he says, Clearly impressed. She inclines her head Imperceptibly, as he continues, “You Joining your boyfriend, husband? He At the market?” Discomfited, she pauses At which he turns back his head and Openly stares at her. She hurries over Her words, no, she is here with her Girlfriends, they are waiting for her by The putu piring. Her eyes shine with Gula melaka dreams as yet unfulfilled Because rickshaw guy takes the liberty To say, “I live alone, have my own house.”

She wonders where he is going with this, As he trips over his words, swerving Desperately in the face of the crowds Thronging her throne, at the edges of which Her thighs are now straining against In despair as the cyclist slows, talking, “I drink alone most nights,” he murmurs, Winking at her. “I do this just for fun in the Evenings, you understand? I’m a civil Servant otherwise.” Now she recovers Herself and snaps, finally. “Can you Drive without talking and stop right there, Next to that cart.” “That one? It’s not Near the stall you want to go to.” Firmly, she enunciates, “Enough. Please stop talking and let me enjoy the Ride and my holiday.” “Holiday alone…” He mumbles but then falls silent. Finally she get back a modicum of her Enjoyment at the lurid colours, Florescent lights of her carriage until The man shouting for cendol is here And off hops this Cinderella, exhausted.

by Pallavi Narayan

She is walking the night market Clad in her short new dress The one she picked up from The day markets. How funny, she Giggles, muttering “Silly goose” To herself. Yellow, even golden Like the sun, like butter on a bun Oh, she’s having fun, with herself As she strides ahead, then ambles Following the drift of the crowd Sometimes she stumbles. She waits In queue for chicken balls, “Oh, it’s Only you? Single person, eh? There Is a table to share.” Later, a butterfly Pea drink, violet-hued, a gift in the Heat, and she is sipping it and noticing The patterns in the graffiti, tiles Blooming intricately under her feet And she’s in an expansive mood when A trio of young women stop her and ask “Will you take our photo?” She acquiesces “Of course!” and when they have suitably Oohed and aahed over it, they linger And ask where her husband or father Or brother is at. “Not even a boyfriend?” They knowingly nudge each other as She calmly pronounces that she didn’t Bother. She’s travelling solo, and has no Reason to wait or watch for anyone, Least of all a man who’d make her come Undone. Their eyes widen, tones hush As their chatter fades. “You’re so brave!” The butter melts, the sun goes down, Gold scatters in a spatter all around. Her dress too short, her walk too long She is astounded, hit by a broken song.

Dr Pallavi Narayan has authored Pamuk’s Istanbul: The Self and the City (2022) and edited Singapore at Home: Life across Lines (2021). Her poetry has been published in anthologies such as Malaysian Places and Spaces, Asingbol: An Archaeology of the Singaporean Poetic Form, SingPoWriMo 2015, 40 Under 40: An Anthology of Post-Globalization Poetry, Poetry in the Time of Coronavirus, Dilli: An Anthology of Women Poets of Delhi; journals like Kitaab, The Initial Journal, Muse India, We Are a Website, and New Quest; and national dailies such as Hindustan Times and The Times of India. In 2006 she was named a Toto Funds the Arts New Emerging Poet and when she was fifteen, she was selected for a national residential poetry workshop with Keki Daruwalla.

Karla Knight is a visual artist born in New York City and currently living and working in Connecticut. She received her BFA in painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 1980.

Knight's work has been widely exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions. She is represented in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Walker Art Center, among others.

She has been the recipient of various awards and honors including MacDowell, Yaddo, and two Connecticut Artist Fellowships. Knight is represented by Andrew Edlin Gallery in New York City, and had her first solo museum exhibition (with catalogue) in 2021-22 at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, CT.

Karla Knight's work consists of imaginary language, objects, diagrams, and symbols. It forms a pictorial language of symbol and writing whose underlying system is not known. Simultaneously ancient and futuristic, the work creates an alternative culture which plays with the mystery (and absurdity) of life, and what lies underneath.

Derived from the ancient Asian form of torture -“Death by a thousand cuts” or “Lingchi”, “A thousand Cuts” is a series of portraits and stories that present a photographic study of patterns of domestic abuse in the South Asian community.

I have borrowed the metaphorical meaning of Lingchi to showcase the cyclical nature of domestic abuse.

The continuous act of chipping at the soul of the abused, is expressed by making cuts on the portrait of the participant.

The paper used to print the portrait is a thin A4 sheet, depicting the fragility of her existence.

I have kept the project at a domestic scale, using resources available within the home as a metaphorical reflection of violence occurring within the human space. The final artwork is photographed in a very closed, tight crop so as to express a sense of suffocation and absence of room for movement.

The red colour underneath the portraits signifies not just martyrdom and strength but also the onset of a new beginning.

“A thousand Cuts” is an effort to understand abuse from many different frames of references.

My intent was to create a metaphorical “waiting room,” where strangers meet and talk to each other without any fear of judgement or hierarchies. An imaginary space where conversations around abusive lived experiences continue to happen. Where it is easy to come out. A room where you are heard, seen, understood and where you feel safe to leave your story behind.

We started by creating that room as a real space. A space in a church in Hounslow, UK. Many of us met there, several times over. We held hands and spoke at length. No one interjected the other. No one left the room midway. These initial dialogues led to the creation of a vector of faith between myself and the participants in this project. We then moved on to private oneon-one conversations and me photographing each survivor individually with their consent and their complete control on the way they want to be “seen.” Once I printed the images, the survivor then selected the image she wanted me to start making the cuts

The premise of my existence

on and made suggestions on the metaphorical representation of their narratives through those cuts. From there on, it has been over a year and the conversations continue. Sometimes I listen. Sometimes I get heard… but we promise to “see” each other.

Through these conversations, we have collectively tried to study the journey of abuse from the private, intimate space where violence occurs; to its place in the public domain, whether it be in terms of how the private reality is subverted; decorated in public or that initial disclosure process when the survivor breaks their silence and speaks out to family, friends, neighbours, colleagues or even absolute strangers. This photographic study draws on interviews with 21 South Asian women (it is an ongoing project) and analyses the interactional and emotional processes of the first public disclosure of their private reality.

The long term intention is to bring narratives of abuse into the public discourse, arts and human spaces. In that sense, “A thousand Cuts” is an invitation for an open dialogue that allows both the survivor and the society at large, to explore concepts such as trauma, suffering, genetic and cultural predispositions, gender and identity politics without sacrificing their own vulnerability or risking confrontation.

In my discussion with one of the participants, who is of Indian origin, we had a very disturbing however, real conversation about how her perpetrators existed within “home”.

“Home” being a metaphorical term here describing not a physical space but energies… many energies and realms of individual and systemic consciousnesses, placed in relative positions to each other.

We spoke of how generations of human and societal conditioning formulated her understanding of simple feelings such as love, care and belonging. How she equated all of these feelings to some or the other form of coercive control and how that understanding itself helped perpetuate and in a sense normalise the verbal and psychological abuse that was meted out to her by her elders and society at large.

It is a very complex reality. Of being a woman. Also, of being a south Asian woman. I started to find in me this urgent need to engage with this complex, yet very subtle reality.

So I reached out to Sayeeda Ashraf at the charity - Shewise UK. Sayeeda and I had been work colleagues in the past and I knew about the immensely important work she was doing in the field of helping survivors of Domestic Violence in becoming financially independent.

I discussed with her about my intent. Sayeeda along with Salma Ullah and Saima Khan from Shewise, have been extremely instrumental in helping me reach out to the survivors and initiate a dialogue that is ongoing of course but is most importantly sheltered with appropriate safeguards.

The survivors who have very generously agreed to participate in this project, are each experiencing differing stages of trauma so it was important for me to ensure that our engagement doesn’t leave their wounds bleeding.

A place to call home

“I have never remembered sleeping without [dreaming].” The words of Minnie Evans from her 1998 exhibition at Luise Ross Gallery, New York

Minnie Eva Jones was born on December 12, 1892 in a cabin in Long Creek, North Carolina. Her young, poor mother was fourteen years old, working as a domestic servant. At the age of only two months, Minnie was taken to live with her grandmother in Wilmington. She was essentially raised by her grandmother, and considered her biological mother to be more of a sister-figure. Her father, George Moore, was also very young when she was born and abandoned the small family. When she was a teenager, Minnie found out about his death, but not until a year after the fact.

Minnie’s family history is full of strong women. Passed down verbally from one generation to the next, their story recounts the experiences of their ancestor, Moni, an African woman who was a slave in Trinidad. She eventually ended up in Wilmington, North Carolina, where relatives still live today.

Minnie began school at the age of five and attended until she was in the sixth grade, leaving school to help earn money for her family. She had loved studying history, mythology, and biblical stories which were part of her deep Baptist faith.

As a child, she often heard voices and had waking dreams and visions. She could not recall a night she slept without having dreams, and during the daytime, recurring hallucinatory experiences lead to a confused sense of reality. According to author Gylber Coker, “there were times when Evans could barely distinguish between dreams and visions, as well as between dreams and wakeful experience.” This continued throughout her life, though the intensity of her visions varied. These waking dreams were often images of prophets and religious figures, real and mythical animals, flowers, plants and faces. She was quite conscious of this unusual aspect of her personality, and cautious about letting other people become aware of this phenomenon.

After leaving school, she worked as a “sounder”, going door-to-door selling shellfish gathered from the waters off of the North Carolina coast. She met Julius Caesar Evans, and married her nineteen-yearold groom four days after her own sixteenth birth- day. Not being of legal age, she wrote her age as eighteen on the marriage license, which became something the couple often joked about during their long marriage through which they bore three sons.

Her husband worked as the valet for Pembroke Jones, a wealthy landowner, and Minnie went into domestic service on the estate as well. After the death of Jones, his widow remarried and moved with her new husband to the estate called Airlie where the Evans’ continued working for the family. The 150 acres were developed into an expanse of gardens and opened to the public in 1949. Minnie Evans became the gatekeeper, collecting admission from visitors, and eventually retired from her post in 1974.

Evans didn’t start drawing until she was 43 years old, when a voice

told her she must “draw or die”. On Good Friday, 1935, she did her first drawing, and the next day a second one followed. Both are now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Her work was an automatic process, seemingly directed by outside forces. Evans stated: “I have no imagination. I never plan a drawing. They just happen.”

It would be five years before she would create another picture. She found her two drawings, both dated and one bearing the inscription ‘my very first’ and the other ‘my second’, stuck in the pages of a magazine that she was about to dispose of by burning. This chance finding seemed fortuitous and signalled the beginning of her fervent art making.

As she began drawing compulsively, her family became concerned that she was losing her mind, but grew accustomed to her endeavours. She gave her pictures to people who admired her work, and eventually hung them up near the gatehouse at the gardens where she worked, selling them for fifty cents each, a sum equal to half her daily wages. Eventually, Evans’ work came to the attention of Nina Howell Starr, a graduate photography student in her forties who was married to a professor of a Florida university. Starr worked with Evans from 1962 until 1984, becoming her de facto agent, traveling to see Minnie frequently and showing her work to New York galleries.

With the encouragement and assistance of her agent and friend, Evans work was widely exhibited. According to the exhibition catalogue Black Folk Artists: Minnie Evans and Bill Traylor from the African American Museum,

“The first Minnie Evans exhibitions were in the 1960s: 1961, Wilmington, North Carolina; and in 1966, New York. Evans came to New York on that occasion, and visited the Metropolitan Museum. This inspired her to enlarge the scale of her work, and to redo earlier pieces in a larger format.”

This is corroborated by Nathan Kernan in his essay, Aspects of Minnie Evans:

“After she returned home, influenced by the larger sizes of some of the works she had seen in the museum, Evans began to make larger works by cutting up existing drawings, gluing them to board or canvasboard, and expanding them with the addition of new paintings.”

An Evans piece in the Petullo Collection bears the dates 1960, 1963, 1966, and shows seams where the board had been cut and a triangular centre section inserted. Presumably, this is one of the paintings she reworked when experimenting with larger picture sizes.

Author Mary E. Lyons tells how Starr suggested that Minnie go back and sign and date earlier works, “Minnie agreed, though she had trouble estimating dates for pictures she had completed ten years earlier. As a result, many dates are incorrect. Not all of the signatures are Minnie’s either – in the early 60s, Minnie asked her granddaughter to sign her pictures for her.”

A retrospective exhibition of her work was mounted in 1975 at the Whitney Museum. Evans was also honoured when May 14, 1994 was declared “Minnie Evans Day” in Greenville, North Carolina.

Minnie continued drawing for most of her life. She moved into a nursing home in 1982, and died there on December 16, 1987 at the age of 95.

From a pdf found on the internet...no author mentioned.

Award-winning author Mohana Gill has once again solidified her legacy in the literary world with a remarkable achievement. The National Book Council of Malaysia, under the Ministry of Education, has proudly recognized Moringalicious: Malaysia’s Gift to the World as one of the 50 Best Malaysian Titles for International Rights 2023-2025. This prestigious honour, presented by Director Mohd Khair Ngadiron, celebrates Mohana Gill’s invaluable contribution to Malaysian literature and her global impact through her culinary and educational books.

At 90 years young, Mohana Gill continues to inspire readers worldwide with her passion for nutrition, culture, and storytelling. Published in 2023, Moringalicious has already garnered international acclaim, including the Best in the World title at the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards. Now, with this latest recognition from the National Book Council of Malaysia, the book’s significance as a cultural and culinary gem is further cemented.

Moringalicious introduces readers to the wonders of the moringa tree—often called the "Miracle Tree" or "Tree of Life"—through 60 recipes spanning global cuisines. From garden to kitchen, Mohana Gill showcases the tree’s nutritional benefits while delighting the taste buds with dishes that nourish the body, mind, and soul. This book is not just a cookbook; it’s a celebration of nature’s bounty and Malaysia’s rich heritage, making it a perfect candidate for international recognition.

Mohana Gill is an award-winning author known for her inspiring books that celebrate healthy living, plant-based cuisine, and children's storytelling. Passionate about food, nutrition, and cultural heritage, she has dedicated her work to educating and inspiring readers worldwide.

Her journey as an author began with a deep appreciation for wholesome food and a desire to share its benefits with others. Through her books, she brings to life the wonders of Moringa, nature’s miracle tree, and other nourishing ingredients that promote well-being.

Mohana’s work extends beyond cookbooks; she has also written engaging children’s books, blending storytelling with valuable lessons about food, nature, and sustainability. Her Hayley’s Series introduces young readers to the richness of Malaysia’s flora and fauna, fostering a love for nature and healthy eating from an early age.

Mohana continues to inspire individuals to make mindful choices, embracing a lifestyle that is both nutritious and sustainable.

https://www.mohanagill.com

Moringalicious-unleash-the-miracles-of-moringa 60-global-recipes-for-wellness-by-mohana-gill

A few weeks ago I had been invited to an afternoon soirée in the beautiful Malaysian home of Burmese writer Mohana Gill (left - aka Mohana Rosie Gill Nee M.R.Dutt - author of the book ‘Mornigalicious’).

It was a gathering, at Mohana’s home, concerning the internationally recognised ‘super-food’ - ‘Moringa’.

According to Mohana (in her book ‘Moringalicious’)…

“Moringa Oleifera, or more commonly referred to as just moringa, also goes by a long list of monikers--horseradish tree, drumstick tree, radish tree, ben oil or benzolive tree, Tree of Life, arango, badumbo, caragua, sohanjna, rawag, la mu shu, teberindo, maranga-calalu--that attest to its widespread use and popularity around the globe. Just as long is the list of health benefits that are attributed to it, and the fact that every part of the tree can be used or consumed, which has led to it being widely hailed as the Miracle Tree.” (Page 16)

An admixture of Malaysian ‘writers’, editors et al were in attendance as we listened intently to our host regale us about the efficacious Moringa tree, its nutritional and culinary uses. That captivating afternoon had culminated with mingling chats while devouring a variety of culinary goodies derived from the internationally reputed Moringa plant, to our earnest delight.

It was only that afternoon that I’d realised that the long, thin, Indian vegetable commonly known as ‘drum stick’ (or Murungakkai in Tamil), used in curries and with dhal, was the seed pod of the Moringa tree and, further, that the small green culinary leaves (‘M’rum' or ‘Daum M’rum’ in Khmer) so very popular during my enforced stay in Cambodia (during Covid 19 times) were of the very same tree, used in soups, salads or in Khmer stir-fries.

The University of California (2018) studies into Moringa have found…

“Almost all parts of the Moringa are edible, from concentrations of protein, vitamins and minerals. This fast-growing tree has great potential as a food crop and can be cultivated in tropical and subtropical climates.

Moringa leaves have a high concentration of protein, making them a good, inexpensive substitute for meat, fish or eggs.

The flowers of the Moringa have a mild mushroom flavour and contain vital amino acids, calcium and potassium. They are also said to have medicinal properties.

Moringa seed pods and seeds are a tremendous source of Vitamin C, protein, amino acids, calcium and potassium.

Moringa roots are ground to create a medicinal past with a flavour similar to

that of horseradish.”

It’s without a doubt that Moringa has a great deal to offer mankind, now and in the future, and is thusly and earnestly championed by Mohana Gill to educate us all into the uses of this amazing plant.

Mohana’s book ‘Mornigalicious’ comes in two editions, one for adults (originally published in 2023) to learn about Moringa and practise recipes, and was chosen (among 200 books) for the China International Book Fair while the second, thinner book, called ‘Hayley’s Moringalicious Malaysia’ and (published in 2024 and illustrated by Tan Day Fern) is one of Mohana’s many beautifully illustrated books for younger readers,featuring her characters Hayley, Zac, Ari and their pets, and has been recognised as one of Malaysia’s 50 best. Both books have been recognised in Malaysia Ed

Myanmar holds a very special place in my heart. It is the place of my birth and where I spent more than two decades of my life, surrounded by my loving family - my parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins - who all called Myanmar home.

Myanmar is an enchanting place. A land of pagodas, festivals, music, dance, and varied communities, existing together with an unbridled joi de vivre, all of which had such an impact on my own life and outlook.

It was this early introduction to different customs and cultures that sparked my keen interest in multinational cuisine. It has been such an exciting journey, and one that endures. Despite half a century of upheaval and instability faced by the country, I still feel very much a part of the new Myanmar. And this is why I felt compelled to write this book on Myanmar's cuisine and culture, its people and customs; aspects of the country still not widely known.

Within the pages of this book are colourful stories and anecdotes of my personal experiences in Myanmar, coupled with my observations of the many layers that make up the nation's warm and spirited population. In order to know the country, you have to first understand its heart and soul, and this is something I hope to bring out in this book. Beginning in my home town, Pathein (the "rice bowl" of Myanmar), and covering six other places close to my heart, I hope you will enjoy this insider's tour of Myanmar

May this book help you gain an insight into this vast and vibrant country, as you discover its cuisine, culture and customs.

Yesterday, during a gloriously wet and therefore a cooler day, just off Malaysia’s ‘Jalan Gasing’ area of Petaling Jaya, I was back at Mohana Gill’s beautiful Malaysian house - marvelling at her tropical green oasis.

A concrete statue oversaw the host’s gardens crammed with herbs, spices, equatorial fruits and, of course, Moringa trees stretching their arms up to dampen their plentiful leaves.

Mohana had sent a Facebook Messenger invitation that I just could not refuse. I was invited to have a home-cooked Burmese meal and a further, this time more in-depth, chat with host Mohana in her home setting.

While I had been fascinated at the first meeting, I was enthralled during the second with tales of Myanmar (then Burma), the USA, and of Singapore.

Then, of course, there’d been the food. If the first repast had been enticing with all things Moringa, the second was a gourmand’s heaven. It was such a great honour to have been invited once to Mohana’s home, but to be invited twice was beyond all measure.

From a simply delicious handmade ‘Burmese’ fish-ball curry (A-tharlohn-hin), to an intriguing preserved ‘Roselle’ dish (Chin Baung Kyaw), a mixed-leaf salad (and accompaniments), to homemade semolina Halva (aka Shwegyi Sanwei Makin), the meal simply over-awed me with its combination of tastes and its loving preparation.

To top the meal off, a pot of well-rounded tea was poured from a striking teapot sporting a blue koi fish prominent from the white of the pot, and into what appeared to be Japanese styled cups sporting a chrysanthemum design.

After the rain we visited Mohana’s garden. I came away with a small Moringa plant which, I am assured, can survive on my apartment balcony. I just have to give the Moringa sufficient water and drainage, and not forget to prune it as it may grow too large.

In Issue 61 of The Blue Lotus magazine (June 2024) I’d mentioned some of the indigenous foods of Sarawak.

One year later I was back at Kuching’s Hotel Borneo (convenient for the China Town area where I was trying to experience more of Sarawak’s indigenous foods).

This time I travelled outside of Kuching (approximately 60km away) visiting the indigenous Bidayuh Annah Rais, ‘longhouse’ (No. 67), and met my Bidayuh indigenous hosts - Karum and her husband at (Karum Bidayuh Homestay).

Over two intriguing days surrounded by Borneo rainforest, heat and moistness, Karum created morsels of indigenous cuisine in her small kitchen at the rear of her ‘homestay’. These were…

Pekasam - Fried Fermented fish with salt, palm sugar, toasted rice, and tamarind (asam gelugur)

Fried ikan bilis with tempoyak and chilli, - aka Sambal Tempoyak. Tempoyak is fermented durian, Ikan Bilis is small fish (Anchovy), dried.

Red Bario rice wrapped in itun sip leaf - locally farmed red rice, wrapped in a local leaf

Stir fried ginger chicken, - not strictly an indigenous dish but popular in Malaysia

Sweet and sour prawns, - the same holds for this dish.

Chicken pansuh, - is chicken and spices cooked in a bamboo tube, over an open fire.

Fresh coconut water, - literally the water inside a fresh coconut.

Deep fried cassava chips with garlic.

Later, back in Kuching city once more, I roved around in and near the old Chinese quarter, which is rapidly becoming a favourite haunt of mine. It was the annual celebration time of Gawai, and I was in search of eating places that I’d missed during my last year’s visit to Kuching.

An A-frame blackboard on the pavement outside JAK MA’AN, Carpenter Street, caught my attention. It welcomed its visitors by proclaiming “Selamat hari Gawai - oooohaaaa Udah mabuk, tinduk bedau mabuk, ngirup agi!!! (Have a good Gawai day - oooohaaaa Already drunk, I’m getting drunk, I’m sipping Agi!!!).

I just had to go in and eat…

Stir fried cassava leaves, - these are minced.

Chicken with tempoyak, - as it sounds.

Stir fried Bamboo shoots - ditto.

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/samphire_island

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/being_here_now_

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/love_s_texture

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/malim_nawar_morning

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/on_the_island

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/cambodia_chill_re-issue

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/lotus

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/remembering_whiteness_booklet

Martin Bradley is the author of a collection of poetryRemembering Whiteness and Other Poems (2012, Bougainvillea Press); a charity travelogue - A Story of Colours of Cambodia, which he also designed (2012, EverDay and Educare); a collection of his writings for various magazines called Buffalo and Breadfruit (2012, Monsoon Book)s; an art book for the Philippine artist Toro, called Uniquely Toro (2013), which he also designed, also has written a history of pharmacy for Malaysia, The Journey and Beyond (2014, Caring Pharmacy).

Martin has written two books about Modern Chinese Art with Chinese artist Luo Qi, Luo Qi and Calligraphyism and Commentary by Humanists Canada and China (2017 and 2022), and has had his book about Bangladesh artist Farida Zaman For the Love of Country published in Dhaka in December 2019.

Canada 2022

(The

Publishing), in Colchester, England, UK, since 2011