THURSDAY, JANUARY 29, 2026

BY WILL SENNOTT

Roy Scheffer’s hands mapped a different era of the Martha’s Vineyard waterfront. Etched by decades of running thick, tar-treated longline and calloused from the rough skin of swordfish, Roy was at the helm of the Island’s heyday of commercial fishing and later pioneered its rebound in aquaculture. It was a pursuit that spanned thousands of miles of open ocean, chasing the horizon to land heroic hauls before circling back to end his career where he first started in his youth: hunting for scallops in the bountiful waters in Edgartown’s Cape Pogue. SEE B14

Roy made his final tow on New Year’s Day. He and his longtime partner Patricia Bergeron were scalloping a half-mile off Cow Bay when they were caught in an erratic winter squall. Their skiff capsized, and both died. Roy was 77, and Patricia was 69.

The deaths are an immense loss for the Island community. But for those who have worked on the waterfront, Roy is remembered for his storied commercial fishing legacy. That includes his family, many of whom have followed the trail he blazed in aquaculture, and countless former deckhands on the boats he captained. In interviews, they reflected on how Roy’s life at sea traces the trajectory of the commercial fishing industry through the 20th century, from the vast expanse of boundless ocean and unregulated fisheries to the later years, when the government began to rein in the fisheries with constricting regulation. For Roy, they said, the ocean was a vast frontier, and he was something akin to a prospector — dedicated to crafting new technology and charting new fishing grounds in relentless pursuit of a haul.

“He was always pushing new domains,” said Roy’s grandson, Matteus Scheffer, 25, who worked on Roy’s oyster farm for years, and now scallops and runs his own lobster boat out of Menemsha. “Whether it was the Grand Banks or the Edgartown Harbor, he loved fishing where no one else had gone.”

Roy’s earliest memories involve his family's role in harvesting the Island’s inshore fisheries. In a 2025 interview with Indaia Whitcombe, an oral historian for the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, Roy described looking out the rear window of his grandfather’s 1950s pickup truck: “I was standing on the seat with my nose pressed against the glass. It was cold. My uncles were loading scallops … two bushel bags … they filled the truck right up,” he said, with a laugh.

had pioneered the industry by developing a form of fishing known as “longlining,” which (the legend has it) they learned on a trip to Japan and imported back home. The fishery, which requires rigorous understanding of the ocean’s currents, involves setting one line, often miles long, baited with hundreds of hooks, and buoys to keep the line afloat. Kristine’s father, Louie Larsen, brought Roy aboard their boat, the Martha Elizabeth, as an engineer.

down the jetty in Menemsha, waving at their father as he piloted back to port after a long trip. He brought Isaiah on trips dragging for flounder when he was as young as 11, and had him make his first tow at 13. “He put a lot of faith in me,” said Isaiah, who is now the Chilmark shellfish constable. “I was a kid, but he wanted me to learn that I could do the work of any crewmember.”

“My first trip, I said, ‘I’m never doing this again,’” Roy recalled in the museum’s interview. But that didn’t hold. Instead, it spawned a 27-year career offshore, fishing from the Grand Banks to the Gulf, from the Azores to Hawaii. Within three years of his first trip, Roy had earned his spot at the wheel as captain of the Larsens’ swordboat. “I had the best teacher,” he said of his

Those who worked on deck with Roy for any length of time are filled with stories of their voyages. Some recalled trips in the Grand Banks stretching as long as 54 days, and others where they pursued schools of swordfish as far as 1,700 miles from port, sometimes ending up closer to Ireland than the Vineyard. Some remember the quiet moments, like the five-day steam to the fishing grounds, with Roy’s feet kicked

link and was stuck upright in the mast’s wires. Somehow, maybe by a crossing wave, the boat righted itself and the arm came crashing down, wrapping itself over the rail. When the weather finally cleared, they continued to fish for 12 more days.

Roy was raised by his aunt, Edie Bennett, from the age of 12, after his mother died and his father, who lived in Holland, was unable to live in the country due to visa restrictions. The family lived in downtown Edgartown, and were among the 150 people scalloping in Edgartown at the time, he recalled. Roy started shucking scallops at 12 years old. “Right after school we would run over and cut until suppertime,” he said. After high school, he too ventured out into the bay for a day's pay in scallops.

A captain who defined the Vineyard’s fishing history.

BY WILL SENNOTT

There were also clashes almost as fierce with the Coast Guard. When Roy first started his fishing, the only boundaries of the ocean were the ones created by nature: shoals, currents, and different types of bottom. But in the mid1980s, in response to depleting fish stocks, federal and international authorities made efforts to regulate the fisheries. They did so by setting consistently declining quotas and carving the ocean into nationalized territories; artificial borders like the Hague Line, which partitioned Georges Bank between Canada and the U.S. The once boundless ocean was closing in with regulation, and the relationship between fishermen and the government was beginning to sour. Like many fishermen at the time, Roy was defiant. The Canadian Coast Guard seized his fatherin-law’s groundfish boat for towing over the newly established line. Authorities wanted to make an example out of him by imposing a large fine and holding him in a federal prison. The profit margins in the fishery were rapidly thinning at the time, and the boat was locked up for months. Though the charges were later dismissed, losing even the one haul and months of fishing was a painful financial blow.

When he was 21, Roy was offered his first trip offshore. He was soon to marry his first wife, Kristine Larsen, and their first child, Kimberly, was on the way. It was the late 1960s. The Vietnam War was escalating, and all across the country there was a cultural revolution. Times were also changing in Menemsha. The old world of wooden hulls and harpoons was giving way to a bold new generation of fishermen. The Larsen family at the time ran two successful swordfish boats out of Menemsha — retrofitted Southern shrimp boats — and

father-in-law, Louie. He learned the trade with relentless curiosity. And as he took the helm, he never stopped developing new fishing techniques and exploring new frontiers. Roy said that when he started fishing, they were setting seven miles of line to load the boat in about seven days. By the end, he was setting 35 miles of line, and often fishing for well over 21 days.

“Roy would say: ‘I don’t like this drag, I’m going to invent a new one,” recalled Donny Benefit, who fished as first mate with Roy on both swordboats and groundfish draggers for 15 years. “He loved the hunt and taking a big chance for the big reward.”

Roy’s son Isaiah and his daughter Kim said they remember chasing the boat

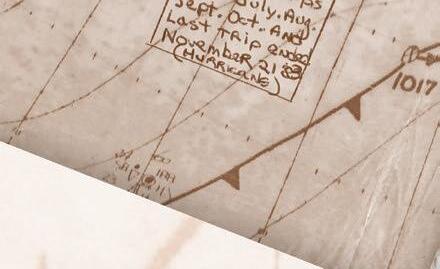

up at the wheel, playing cribbage and listening to Jefferson Airplane. And there were moments as far from that calm as possible. In one harrowing account, Doug Benefit remembers Roy clutching the wheel for 18 hours straight as he navigated a fierce October hurricane two weeks into a trip on the Grand Banks. At one point, he said, the boat rolled hard on its side while climbing 35-foot waves. He remembers walking on the wall and steadying his hand on the floor as he rushed to inspect the boat’s stabilizer arm, which had snapped off its

After years of ratch-

1. Crewmember loading the deck with swordfish.

2. Bird's-eye view, the swordboat.

3. A deckhand carves into a fresh swordfish.

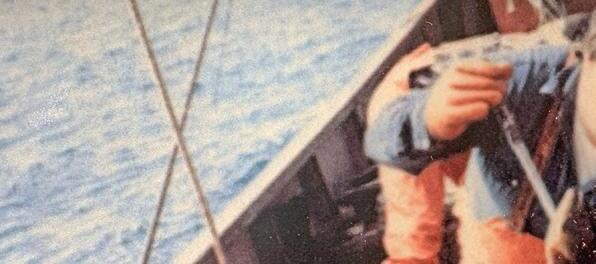

4. Roy bringing a massive tuna over the rail.

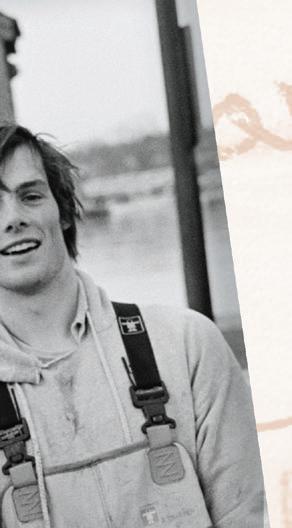

5. Roy on deck, preparing for the next voyage out to sea.

6. Roy and his son, Jeremy, dragging for flounder.

7. A jumbo swordfish, with Roy for scale.

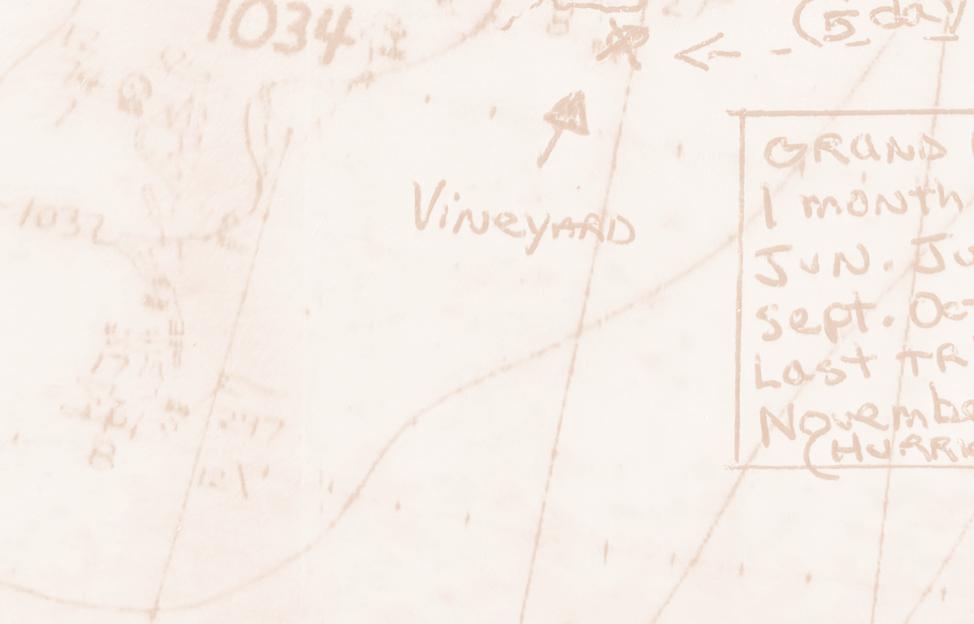

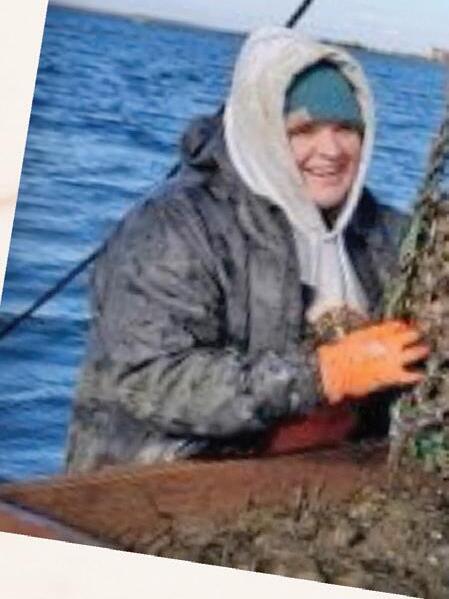

Roy with his grandson Matteus and two bushels of bay scallops.

eting regulation, in 1996, Roy decided to get out. “When the government told me I couldn’t go fishing, or I couldn’t catch the amount of fish that I wanted to catch, that I’m able to catch, I said, ‘Well, this isn’t for me anymore,’” he said in his interview with the museum. But his pioneering spirit didn’t stop. Dedicated to earning a living

on the water, he took the same ingenuity inshore. Working on a grant through the Island’s shellfish group to create jobs for displaced fishermen, Roy and others experimented with different shellfish that could grow in shallow waters like Katama Bay. They tested quahaugs,

mussels, and scallops. But it was oysters that showed the most potential for aquaculture.

“They just started growing. I mean, every time I picked them up, they’re bigger and bigger,” Roy recalled. The equipment didn’t exist yet, so Roy took to welding cages that are the model of the plastic-coated wire cages used today, and introduced all sorts of hydraulic equipment to assist him in the backbreaking work.

“He was really the first. It was his success that convinced people, fishermen, they could make a go of it growing oysters down there,” said Jack Blake, who also pioneered the industry alongside Roy in the 1990s.

“He needs a lot of recognition for that. There’s only one of him.”

Today, oysters have evolved into a multimillion-dollar industry and a stable career

Three generations of the Scheffer family on the oyster farm (Roy, Noah, Isaiah, Matteus). 10. Roy and Patricia hauling in a healthy tow of bay scallops.

on the water for many fishermen with dozens of farms across the Island. Roy’s legacy offshore is one now remembered mostly through old photos, through relics like the swordfish logo on Larsen’s Fish Market, and in the absence of the large, rusted rigs that once lined the Menemsha Docks. But his legacy inshore persists. Roy’s children and their sprawling, extended families continue to harvest shellfish — scallops, lobster, conch, quahaugs, and steamers — from all corners of the Island. Two of his sons, Jeremy and Noah, operate their own oyster farms in Menemsha Pond and Katama Bay. Roy’s youngest daughter, Martha, who worked alongside him for the past 20 years, will run the oyster farm on her own this year. She said she would continue to market the product as “Roysters.”

“I learned so much from him,” she said. “I feel so lucky to have been able to be out there with him all these years. There’s nothing he loved more.”