Dear Reader,

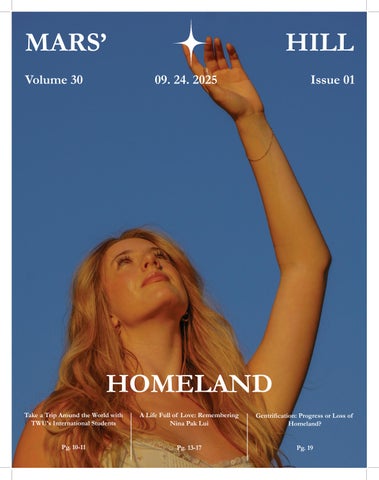

As the theme of our first issue of the year, “Homeland” invites us to explore our relationship to the places where we have lived and to the land we live on.

For some, homeland may be associated with words like “stolen,” “war-torn” and “polarized.” In “Three Books To Deepen Your Understanding of Truth and Reconciliation,” staff writer Sophie Agbonkhese recommends books by Indigenous Canadians for those who want to learn more about the history of this land in advance of Trinity Western University’s Day of Learning on September 26 and Canada’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30.

To others, homeland may have a more positive connotation, evoking a sense of shared cultural identity. Opinions section editor Cristina Pedraza explores the concept of the homes we live in on the internet in her article “Digital Homes,” asking if our time online is taking us away from the people and places that matter most.

As Christians, our homeland on Earth is only a temporary one because Heaven is our true home. In this issue’s feature, we remember Assistant Professor of Education Nina Pak Lui and the impact she had on TWU as a passionate educator and the

legacy of love she leaves behind as a devoted wife, mother, daughter, sister and friend.

While our relationships to our homelands may be ever-changing, I encourage you to reflect on the ground beneath your feet and your countries of origin as you read this issue of Mars’ Hill. Whether you are homesick, wanting to leave your homeland or are in search of a new one, I hope you find a place where the door is always open and the lights are always on.

Sometimes we find a home in unexpected places, such as in the collegiums over pancake breakfast, when cheering on the Spartans or while walking the Salmon River Trail around McMillan Lake. And if not now, I believe that you will find a space where you belong, welcomed as who you are and who you are meant to be.

Sincerely,

Fried egg The blonde girl from O-Day is so

Calista Yinya Chung is the hottest, most amazingest, coolest, smartest RA in Douglas North Low room 105.

The most cursed bathroom location is the lower caf, but it’s perfect for puking. What’s ur fav kind of dawg? Literally write anything. Egg Fried egg @pillar.yearbook on ig <3 ;)

Bree Hunemuller is the hottest girl alive. She plays the drums and volleyball.

67 I have a huge crush on Holly Nelson.

“In spite of ourselves, we’ll end up sitting on a rainbow Against all odds, honey we’re the big door prize”

“Beware of the sultry-voiced chatbots” - wise words from my prof

Ever wonder what train’s rolling past campus? Canadian National Railway usually blasts the louder horn, while Canadian Pacific keeps it quieter. Personally, I think CN wins just for making its presence known.

wHY IS going into a bAthroom at the Same Time aS Someone elSe Intherently shAmeful Can the collegiums not be at billion degrees all the time? Please…

There’s a bunch of people I want to befriend but I’m very awkward, HELP.

you have some information that you want to get out to the student body? Whatever it is, the declassifieds are here for you. Submit yours at www.marshillmagazine.com/declassifieds-section 3

If you’re wondering what that LOUD sound is during your 4:30 class, it’s my stomach GROWLING. Sorry.

a curated playlist

NEVER GET USED TO THIS — Forrest Frank, JVKE

Wrong Plant — Ribbon Skirt

Mess Is Mine — Vance Joy

Sweet Disposition — The Temper Trap Catch & Release - Deepend Remix — Matt Simons, Deepend

Riptide — Vance Joy

Feet It (From “Invincible”) — d4vd

Graceland — Paul Simon

Wolves Don’t Live by the Rules — Elisapie, Joe Grass

Take My Hand — Jeremy Dutcher Nomads — Aysanabee

Dirt Roads — Tia Wood

Anchor — Novo Amor

The Woods — Hollow Coves

Back Home Again — John Denver

Emma Helgason

Kyle Jin is one of those people who quietly stands out with his easygoing nature. However, turn down the lights and put him in front of a drum set, and he will go wild. I had the opportunity to sit down with Kyle and witness his passion for drumming come to life as soon as we started talking. You would never guess that he is studying education, not music, given the way he talks about punk music. Leading two lives, Kyle truly resembles Batman—an education student by day and a drummer by night.

MH: Could you introduce yourself and tell me about your drumming background?

KJ: I am Kyle Jin. I am technically in my second year academically because I switched my major from business to education. So, while I am a third-year student overall, I am in my second year of the education program. I have been drumming since I was seven, almost eight, so for 11 years. It has always been a thing in my life ever since then. I did start learning piano at the same time, but I quit after a year—it just was not for me. But it

did help me learn how to read music, and I do read music now.

MH: What is your favourite thing about drumming? What drew you to the instrument?

KJ:

“Drumming is a very self-directed instrument. You are your own world—you control everything. There is no right or wrong in drumming.”

You can play the easiest note on the snare for a whole song, and you are not wrong. It just might sound bad, but you are not wrong. It is inspiring because you do not need to follow anyone else. You create your own fills, your own rhythms and that is what makes it so creative and personal.

MH: Tell me about your band. What is the story behind Sponge 49?

KJ: Sponge 49 started last spring during TWU’s Music program talent show called the Orbs. I saw a guy performing “Everlong” by Foo Fighters, and I realized he was into rock music like me. Another guy sitting near me also loved punk music. Later, we decided to perform together and ended up winning a prize—a sponge! That is where the name Sponge 49 came from. The “49” is kind of an inside joke. You will have to ask our bassist about that one.

MH: How have you found performing with your band?

KJ: We have performed at events like Hootenanny, TWU’s biggest talent show of the year. It has not always been smooth sailing. Last year, there was a lot of back-and-forth with the organizers because they did not want bands performing due to setup challenges.

“I ended up buying a portable drum kit on the same day to make it work; I would do anything for performing.”

During the performance, we faced a technical issue: our guitarist’s pedal was not working, and his guitar could not get distortion. Then suddenly, out of nowhere, someone in the crowd started yelling “distortion,” and then the whole gym started chanting “distortion.” Oh, it was awesome. We played smoothly in the end.

MH: Should we be on the lookout for any Sponge 49 original songs?

KJ: We have been working on our very first original song recently. We just came out with the title and some background story. Hopefully we can get it done this semester, if not... stay tuned!

MH: Your passion for drumming and education shines through. How do you plan to connect your love of music with your future career in teaching?

KJ: As an international student from Beijing, I am an English language learner myself. I want to help people like me because I have been through all these processes. I know what being a minority feels like, and I understand that feeling. While I know I will not pursue music professionally, it would be cool to keep playing gigs on the side while working as a teacher. Go on gigs at night and then teach kids during the daytime.

MH: Do you have a favourite artist or one that you consider a role model?

KJ: I mentioned that I like that emo and punk, especially Midwest emo. There is a band called Hot Mulligan that I really love. Their music is mostly about connecting to teenage feelings, something that I have found inspiring. I also grew up listening to bands like Guns N’ Roses, Green Day and Linkin Park. Oh, and I am actually going to a Linkin Park concert this month in Vancouver—I love them!

MH: Thank you for your time, Kyle. Sounds like you are ready to rock both the classroom and the stage!

Sophie Agbonkhese

On September 26, the TWU community will gather together for a Day of Learning in anticipation of Canada’s fifth annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (NDTR). Arising from the grassroots Orange Shirt Day movement and the call of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) for a national day of commemoration, the NDTR honours the victims and survivors of residential schools as well as their families and communities.

The Day of Learning is a fantastic way to engage with Stó:lō protocols and traditions, hear from a number of Indigenous speakers and delve deeper into the TRC calls to action and current research projects inspired by Indigenous ways of knowing and being. However, you may have questions about truth and reconciliation not addressed on the Day of Learning. Or maybe a speaker or activity sparks your curiosity and you want to extend your learning. Here are a handful of insightful books about the legacy of Canada’s residential school system and what reconciliation might look like for our fractured nation.

Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation by Justice Murray Sinclair

In this powerful memoir, former judge, senator and activist Murray Sinclair explores four essential questions—Where do I come from? Where am I going? Why am I here? Who am I?—to pull readers into his legacy of leadership and service as well as his inclusive vision of a shared country. Assistant Professor of Communication Loranne Brown is vigilant about including truth and reconciliation content in her courses, which introduce students to Indigenous journalists and memoirists. On her reading list last year, Who We Are—released less than two months before Sinclair’s death—was one of her top recommendations.

Seven Fallen Feathers by Tanya Talaga

Between 2000 and 2011, seven high school students, each of whom had moved to Thunder Bay, Ont. to pursue the high school education that was inaccessible in their remote hometowns, lost their lives in tragic circumstances. Seven Fallen Feathers, a sweeping exposé

by pioneering Anishinaabe journalist and speaker Tanya Talaga, seamlessly weaves together each student’s story with historical and current background information that helps readers better understand the barriers stacked against Indigenous Canadians. From the establishment of reserves and the imposition of treaties to the Indian Act and residential schools, Talaga pieces together the actions that have led to the current situation.

52 Ways to Reconcile: How to Walk with Indigenous Peoples on the Path to Healing by David A. Robertson

Understanding history is critical to making progress with truth and reconciliation, but there is another pressing question we often struggle to answer: what can I do now to make a difference? In this straightforward guide, Robertson outlines a year’s worth of meaningful weekly actions designed to strengthen relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. By exploring Indigenous food, arts, culture and history, we stand to gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of the rich nations on whose land we live, work and play.

Sophie Agbonkhese

Each year, Trinity Western University welcomes more than 2,000 international undergraduate students representing over 70 countries. This provides an amazing opportunity for all students, both domestic and international, to practise radical hospitality, or love of strangers. Matthew 25:35-40 tells us that whenever we welcome strangers, we are actually welcoming Jesus. In our beautiful, multicultural community, we have a daily opportunity to not only share our homeland with visitors, but also to experience the richness of other global cultures.

With that in mind, we have asked three of TWU’s international students to give us a glimpse into their home countries and the aspects that make them special.

Heyan Yang, first-year sociology major

MH: Where do you call home?

HY: I’m originally from Qingdao, a city on the east coast of China.

MH: What do you want people to know about it?

HY: It’s a very beautiful place, and in many ways it feels similar to Vancouver because of the ocean and the scenery. Qingdao is especially famous for its beer and seafood. It was occupied by Germany during World War I, and because of that, you can still see traditional German-style architecture and even a large old beer pipeline in the downtown area.

MH: How long have you been in Canada and what brought you here?

HY: I have only been here for seven months, but I studied in Europe for four years. My high school teacher highly recommended [TWU] because it’s a Christian university.

MH: What do you miss the most about your hometown or country?

HY: I miss my dog and the sea smell.

MH: In what way(s) has travelling away from your place of origin helped shape you?

HY: It has shaped me as a person to know what I want, what I want to do and what I can do. It has helped me to know myself better.

Cristina Pedraza, second-year political science major

MH: Where do you call home?

CP: For me, home is Mexico City.

MH: What makes it special?

CP: Mexico City is truly a place where everything is constantly moving. It is huge with a myriad of things to do, from visiting pyramids to going to the latest art festival, you can never get bored. But the best part about it is the people and the food. There’s always someone to talk to and amazing tacos to eat on the street.

MH: How long have you been in Canada and what brought you here?

CP: I’ve been in Canada for a little over a year and I came here for my degree because I wanted to experience education outside of my home country.

MH: What do you miss the most about your hometown or country?

CP: I miss my friends and family the most, with the food being a close second.

MH: In what way(s) has travelling away from your place of origin helped shape you?

CP: It has made me push myself out of my comfort zone so much. From immigration processes to navigating how to make friends from scratch, it’s all very new territory for me.

Mariam Khaled, second-year MA in Interdisciplinary Humanities student

MH: Where do you call home?

MK: Cairo, Egypt. As long as I am there, then I am home. The whole city is my home. I belong to every street and building and house and tree. They are all mine, and I am all theirs.

MH: What do you want people to know about it?

MK: Cairo is more than the historical monuments it holds. While the pyramids and the temples and the Sphinx and everything else are truly a wonder, the people and their spirits are what makes Cairo, Cairo. So, if you ever visit, venture out to meet the people as much as you would to see the places; both are well worth your time.

MH: How long have you been in Canada and what brought you here?

MK: I have been here almost one full year now. I came here to study.

MH: What do you miss the most about your hometown or country?

MK: For some reason, I never miss the big stuff. I miss hearing my name pronounced correctly. I miss the smell of the sun. I miss the melodic honking of cars mid-rush hour. I miss the feeling of knowing that exactly where you stand, a hundred years ago, someone else stood in the exact same building under the exact same shade, and a hundred years later someone else will stand there too. I miss knowing that I was part of the ever-continuing history of my city, that even if I won’t be remembered, it is still a fact that I was there once, just like the millions before me. An ever-present sense of belonging.

MH: In what way(s) has travelling away from your place of origin helped shape you?

MK: To be fair, I spent most of my childhood away from Egypt. I took my first airplane away from home at two-months-old, so I don’t think it has shaped me significantly in a way I can pinpoint. But I do see a difference in myself since coming here. I understand more of the world, as cliché as it seems. Knowing there is a wide world out there is quite different from experiencing it firsthand. [It has helped me] understand that I can stretch my hand as far as I can, and I would still find people to know and love and share great memories with, even if it is the exact opposite of everything I grew up knowing.

A Conversation with TWU’s Newest Assistant Professor of Biblical & Theological Studies

MH: Welcome to Trinity Western University! We are grateful to have you share your wisdom and expertise with our community. Can you start by introducing yourself and telling us a bit about your background?

SP: I’m Dr. S.J. Parrott, a born and raised Canadian who has recently returned to Canada after seven years overseas. I have a bit of a mutt background in terms of education—my bachelor’s is in business and marketing! But by my second masters I formally entered into the field of First Testament and biblical studies. My doctoral work, now published as a monograph, was on prophetic metaphors of clothing and unclothing, where God is the divine investor of dress and personified Jerusalem is the recipient of His actions.

MH: What led you to TWU?

SP: The simple answer might sound too simple to some, but God led me to TWU. Prior to beginning my work here, I lived in Germany for three years. God made it clear to me that it was time for a change and to be dependent upon and trust Him as I applied for jobs back in North America. I really loved living in München and I find moving hard as you have to start your life over again, so this was a real act of trust for me. And God delivered as I had multiple opportunities open up before me. TWU emerged as the right option as I felt God had something more for me here than simply teaching and research; there was a reason I was to be here and not anywhere else that I don’t yet comprehend. I’m excited and very honoured to be here and I look forward to learning from my students and fellow colleagues.

MH: What are you most excited about in your new role?

SP: I’m excited about many things: getting to know my students, learning from them, growing in my teaching skills, learning from all my colleagues in the humanities, continuing my research under the banner of TWU and having a voice (however small) in shaping the life and future of the university. I’d love to see our faculty grow and flourish as more young people come to see the value in the humanities with respect to our vision of ourselves and our society.

MH: One of your areas of expertise is identity and identity formation. What advice do you have for students who are seeking to define themselves and their identities?

SP: I’ve thought for many years now what a terrible burden it is for young people in our modern and post-modern culture to have the task of being the sole definer of who they are. We are told, taught even, that it is up to you and only you to define or create your identity—no one else gets a say, no one is allowed to influence how you define your own identity. And should they, they will certainly be told to not tell someone who they are or could or should become. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying the individual has no role in defining themselves—it would be nonsensical to think otherwise. But what anxiety must come with this task, how isolating it must be, what social anxiety must come for fear that someone might reject who I have said that I am—especially for young people who are struggling to figure this exact thing out.

I struggled with figuring out who I was in my early twenties. I was confused about who I was, there were aspects of myself that I didn’t like and I had constant stress about whether people would like me or not in light of these things. I went away on a retreat and simply asked Christ to tell me who I was and what I was here on earth to do. And He answered. That experience, almost 10 years ago now, was life changing, and I’ve had freedom in knowing who I am ever since…not because I crafted an identity for myself, but because I allowed God to tell me who I was and unravel the confusion and lies I believed about who I was. So, I guess my advice to students would be to let their Maker have a say in defining who they are, for He knows them better and sees them far more clearly than they can. Indeed, parts of myself that I hated for many years I came to see as the most beautiful characteristics that God instilled in me.

MH: Tell us a little-known fact about yourself.

SP: I love to dance.

MH: How can we pray for you?

SP: Pray that I begin well, learn much, remain dependent upon God and have much joy in this new season of life.

Sadie McDonald

“She was a great mom,” said Jason Lui, husband of Nina Pak Lui. “The kids and I loved how gullible she was at times. She had a passion for learning, sports and travelling. The cool thing is that the kids wanted to continue travelling, and as Nina was sick, she just encouraged that too. She said, ‘You know what, go to places that we should have visited together.’”

Jason and Nina met at Pacific Academy in 2001 when he was hired to be a PE teacher and she was starting her new position as the assistant counsellor to the high school. A maternity leave resulting in Jason transferring to the middle school meant that he and Nina did not see each other until the following year at an outreach retreat.

“By then, some of our mutual friends were saying, ‘Hey, don’t you know Nina?’ or, they were asking Nina, ‘Hey, don’t you know Jason?’” he recalled. “Finally, I had the courage to be like, ‘Okay, like a lot of people have been talking about us, you know. Do you want to grab some hot chocolate and a cookie, and we could talk?’” That talk began a five-to-six-year relationship before they got married and later had Yuna, now 14, and Jonah, now 12.

Nina’s passion for curriculum design and assessment informed her work as she taught and mentored new and upcoming teachers at TWU. She began in 2015 as a part-time instructor in the School of Education and became an assistant professor in 2019. Nina was recognized in 2020 for her professional excellence, scholarly experimentation and innovation when she was awarded the TWU Provost Innovative Teaching Award.

In 2022, Nina became a PhD student at the University of British Columbia to get her doctorate in Community Engagement, Social Change, Equity under the supervision of Dr. Leyton Schnellert, associate professor in UBC’s Department of

Curriculum & Pedagogy and co-director of the Canadian Institute for Inclusion and Citizenship.

April 18, 1980 - May 14,2025

“Her goal for the PhD was to decolonize self and reflectively and reflexively transform practises in teacher education,” explained Jason, noting that Nina took what she studied at UBC and put it into practice at TWU.

“She really had to look back to how she grew up as an individual,” said Jason on Nina’s decolonization of the self. “She definitely just started that journey, so part of that was to connect with the First Nations people in B.C. and see how the university education programs in B.C. can help First Nations teachers become better teachers too.”

There is room for improvement in all post-secondary programs, and like all teachers, Nina reflected on her own practises. In focusing on the reflexive transformation of teaching practises, Nina viewed improvement as something that should be an automatic reflex, not an obligation.

“She was not only a colleague but a friend who shared deeply in the joys and hardships of life,” said Patti Victor Switametelót, Trinity Western University Siya:m. Patti’s work with Nina began in the School of Education when Nina would invite her to speak in her classes so that Nina could learn about Indigenous ways of knowing and being alongside her students. As Nina entered her doctoral studies, Patti became her coach and mentor, something she described as a “privilege.”

“Her pedagogy of reciprocal and collaborative relationships was modelled in her active participation in the Day of Learning, in supporting Indigenous teachers in their journey, and leaning into the importance of identity, not only her own but including students,” said Patti.

Nina’s embracement of Indigenous ways of knowing and being are present in the memories of Nina most significant to Patti, such as when Nina and her family came to the Naming Ceremony at Xchíyò:m.

But Nina’s work with the communities around her did not stop there. Jason is currently an ELL teacher at a school with lower literacy rates.

So, Nina had some of her third and fourthyear education students come in and do a field experience as a way of serving the community and help increase the students’ reading rates. The work Nina began with the school’s administration team continues today, now under the co-leadership of the school’s current principal, the reading recovery teacher and Lisa Olding, a sessional assistant professor of education at TWU.

So when Nina began struggling to recall words and having difficulty reading, she knew something was wrong. “We still remember the day that it all happened,” said Jason. “It was September 29, 2023, and the emergency doctor came

in and said, ‘Hey, you’re not going anywhere because we found a mass. It’s right above your left ear, where the temple is, so you can’t go home and we’re gonna do a surgery pretty much right away to get it out.’”

It was a world-flipping moment in which the Lui family’s future suddenly became unknown. Jason and Nina did not tell their kids right away, needing to gather their thoughts. “We wanted to let them know that we were going to fight this— whatever this unknown mass was—together, that we were gonna fight with mom alongside mom,” said Jason. “That was our primary mission as a family, to continue to fight against this disease, whatever it was.”

Submitted by Jason Lui.

What the disease was took longer to learn, as the brain surgery that removed 30 to 40 percent of the tumour took place on October 6, 2023, and the diagnosis of glioblastoma was made a month later.

According to Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, two to three per 100,000 people in Canada get glioblastomas, the most common and aggressive cancerous tumour originating in the brain. Glioblastomas are more common in men and individuals above the age of 45. There is no cure.

When Nina was diagnosed at 43, her five-year survival rate was less than five percent, and with treatment, her prognosis was one to two years. The second time the emergency room doctor came to speak to Jason and Nina, she gave them some advice: ask for help.

“She’s seen families be in two different camps. The first camp is the families who would hold this information in private because they want to walk by themselves through this journey. The second camp would be the opposite, where they would share it with people who are close to them and ask for help,” recounted Jason.

Those in the first camp became more bitter and resentful, while those in the second camp were healthier in the long run. Nina did not have to think twice. “I remember Nina automatically said, ‘I want to get help,’” said Jason, whose response was the same.

The amount of help that the Luis received over Nina’s 20-month journey with cancer was abundant, making the three brain surgeries, 30 rounds of radiation and four chemotherapy treatments easier to handle as the community pitched in to make a GoFundMe page, meal train and Facebook group and to provide gardening lessons, insurance paperwork advice and company during medical appointments and hospital admissions.

Nina’s biggest supporters included ‘The Fantastic Four’—Julie Frizzo-Barker, Christine Song, Megan Kuo and Suzanne Sheena-Nakai —who each took on responsibility to help ease some of the burdens faced by the Luis.

Less than five weeks after Nina’s first brain surgery, an MRI revealed that the portion of the tumour that had been removed had already grown back. Many forms of grief accompany a cancer diagnosis, and part of this involved Nina grieving her old self. “I remember she kept saying how, out of all the places to get cancer for me, it

is the brain because she was a PhD student and a professor,” said Jason. “For her, in losing her brain like that, it was just very frustrating.”

Nina’s cancer was in the temporal lobe, the language centre of the brain. However, this also resulted in the inability to filter emotions, causing Nina to react to triggers by becoming anxious or angry. The family’s counsellor helped them process this. “Sometimes you see Nina there, but because it’s brain cancer; it’s almost like you’re sometimes talking to another person,” said Jason. “We named that person ‘Glio’ after glioblastoma, so to us it would be the situation against Glio, not against mom.”

Despite the challenges of cancer, the side effects of chemotherapy and the consequences of major neurosurgery, Nina continued to learn. When she could no longer read, she listened to audiobooks, specifically ones on how to navigate challenging seasons. In this, both Nina and Jason discovered there’s no guide for how to grieve.

Nina’s faith was evident to those around her, and even though she asked God why this was happening to her, she continued to praise Him. “I remember at the hospice in the last few weeks, she would be asking me, ‘How much longer before I see Him?’” said Jason. “I think she knew, and by that time, the doctors and the oncologists were already letting us know that they tried everything.”

It was faith that helped Jason, too. “I know I wouldn’t have made it without Him. He showed up every day, and His goodness ran after me every day. I just had to intentionally see it,” he said.

“There’s hope. There’s trust in Him that this is not the end of Nina. She lives on in each one of us who has been touched by her. How can I move forward representing Nina and representing Him, and how can I help my kids do that?”

For Jason, living like Nina would look like being passionate about lifelong learning, knowing that it is okay to make mistakes, being responsible for your actions and setting healthy boundaries. “Nina would want people to learn how to ask for help. We definitely learned that as a family through this journey,” said Jason. “We realized that people are willing to help, but they just don’t know how to. Nina lived her life learning to be a better person, so that she in turn could serve others better.”

Photo by Rachel Pick.

Nina’s celebration of life on June 8, 2025, was attended by more than 500 people, a tribute to the many people whose lives she touched. And yet, her story is not over. True to her fashion as a lifelong learner and educator, Nina desired to use her experience to help others.

“Right after the first brain surgery, when she was just sitting at Royal Columbian Hospital and Julie was visiting, she said, ‘Hey, Julie, can you write a book? You and Jason should write a book about me and this journey,’” said Jason. “We were trying to find resources to see how other families have gone through glioblastoma, and there weren’t any current or relevant ones. The heart of Nina is wanting to help others.”

So Jason began to write, and two of his close friends agreed to be the illustrators. “I think it’ll just be an incredible tribute to Nina. Our goal is to help other people through this and to remind them that they’re not alone,” said Jason. “Even though there’s suffering and grief, life is still full of silver linings, or, in our case, as believers, His goodness.”

Watch Nina Pak Lui’s celebration of life.

GoFundMe: Support for Nina Pak Lui’s cancer journey.

Cristina Pedraza

All around the world, little historical pockets within cities transform into new hotspots. Beautiful new coffee shops, restaurants and vintage stores open as a new wave of residents enters the scene. Every city in the world faces this phenomenon. From London to Mexico City, gentrification seems to be unavoidable and more present than ever before.

Gentrification, in a broad sense, happens when a neighbourhood sees an influx of more affluent, middle-class residents, which in turn displaces the lower-income original tenants. This change in the residents’ purchasing power often leads to increased property values, new investments and economic changes that could appear to signal progress.

But as we have been shown, not all that glitters is gold. This shift may have a deeper impact than is seen initially. The dramatic shift in a neighbourhood’s demographics displaces the original residents and drives the housing crisis up, increasing the cost of living in the adjacent neighbourhoods.

At first glance, the idea of gentrification can seem like a new promise for progress and opportunity in less developed areas of a city. A neighbourhood loved by many can be revitalized, infrastructure can be improved and even crime can decrease. While these are all positive developments, the true underbelly of gentrification has negative consequences for the local population that once called those places home.

Imagine living in a neighbourhood where you know all the residents and have a historical connection to the place. Rent is perfectly affordable for you and others in your community. Then, in the blink of an eye, all the people and places you grew up with change little by little. Eventually, rent increases become unpayable for you and your neighbours. You have been priced out of your own home.

This is the reality for many. Locals are displaced from their homes and lands in the name of progress.

“When housing becomes a means entirely directed towards profit, we lose. We lose the communities, the people, the history, the buildings and create even more inequality in housing.”

There is a lot of good progress that can come from developing existing neighbourhoods and the social capital this brings to residents is invaluable. But when change can only be made through the displacement of locals, social mobility and preservation are hindered. This calls into question the price people ultimately pay for so-called “progress” and the ultimate need to reevaluate if what is good for the economy truly benefits our communities.

Emma Helgason

Sitting in 45 minutes of rush hour traffic to get from Abbotsford to TWU, stressing over finding an empty parking spot and barely making it to class. This is often the daily routine of a commuter. As the semester goes on, the routine will start to feel more transactional than anything.

“TWU may be known for its rich community, but for us commuters, that community can feel like something observed from the outside.”

It should be noted that there are well intentioned spaces for commuters, such as the collegiums, chapel and TWUSA lounge. For example, the four collegiums located around campus offer a place to study, eat or meet other commuters. Past events, such as speed dating at the West Coast Collegium, are evidence of the effort being made by TWU students. However, these spaces lack something; they are a place to visit, not places to call home. Commuters use them as pit stops between classes. It is like having a layover at Toronto Pearson International Airport right before getting on your next flight. Although made with great intentions, these places do not carry a sense of home.

For us commuters, it can feel like the dormitories are where lasting memories are made. There students learn each other’s names, their favourite snacks and even the sound of their alarm clock! They are fortunate enough to have late-night conversations while sharing meals and even taking part in “dorm dates.” For us commuters, these moments are a little more difficult to come by. Names are forgotten, and

meals are not so affordable. For instance, you can tell my name is Emma just by looking at the author of this piece. Do you know what I look like? Most likely not. After all, I am a commuter. Like many of us, I know how difficult it can be to feel truly connected to campus life.

But where does this disconnect stem from? TWU has made many efforts to include commuters, and their efforts are greatly appreciated. Thus, I believe the real question arises when looking at the commuters themselves. It is easy to fall into the habit of arriving, sitting through a lecture and leaving. This mindset may be easy; however, it makes it harder to feel truly connected to campus life.

“Belonging is not just handed to anyone: it is built.”

Now this house may not feel like a home; but that is just a mindset. Belonging is not just handed to anyone: it is built. It is built by stepping outside comfort zones and choosing to engage. Ask for someone’s name and actually remember it. If you see someone from your previous class, go and say hi. Stop by the TWUSA lounge, the Mars’ Hill office, or the Pillar office and introduce yourself—we all love to chat! Better yet, join something!

At times TWU may feel like a house for many commuters—a place to go. Thus, the real challenge is finding ways to turn such fleeting moments into real connections—to make the campus feel less like a house and more like your home.

Cristina Pedra

As the first generation to truly grow up online, we have something unique to the modern age: a home within the confines of the internet. For better or for worse, our ideas, values and even our culture have been shaped by our access to digital media. Within the ever-changing and everlasting online space, we have created a new home for ourselves. A space we reach for constantly since any emotion can trigger our response to engage with the little world we have created, either to share our joys or forget our worries.

The recommended videos on our YouTube pages, the pictures we see on Instagram and the continuous stream of TikToks work like strange little decorations in the rooms we have created online. While it is easy to understand the internet as just another tool we use daily, the reality is that the internet shapes us. Just like spending around four hours daily somewhere would impact you, the internet does that too.

Having a personal little retreat sounds amazing in theory; the possibilities seem endless, but maybe it has always been too good to be true. The issue comes from the fact that these homes were created by a powerful algorithm that made us develop a habit, and at some point we all just started staring at our little worlds without giving them a second thought.

We spend so much time looking at these digital decorations through a screen that we can forget what truly matters.

“Our perfectly curated digital homes eat up the spaces that were supposed to be reserved for people and places around us.”

The people we are and where we are going are changing dramatically too. And there is nothing wrong with having such a connection to the internet and to your own world, but maybe, just maybe, it is time to set those time limits to give yourself back to your real home—the people and places that an algorithm did not curate.

It may be time to delete some of those pesky apps that are robbing you of your time to regain some control over what has your attention and energy. Or it could be removing scrolling from your morning routine. The goal is not to fully remove the digital homes we have built for so long but to readjust the relationship we have with them, their pull on us, and create a more mindful consumption of media. We need to be able to choose what can come into our home, what deserves space on the walls and what does not, instead of just accepting it all. Most importantly, we can work on remembering the homes that really need and benefit from our attention.

Hamdan Sadiq Chaudhry

MH: What is your team, year and major?

EH: My team is track and field, so I do the 200 and 400 metres. My major is HKIN and I’m a fourth year.

MH: How did you first get involved with track and field?

EH: I got involved when I was 13 years old, in middle school. I originally started in cross country and then I got these sheets to sign up for track and field. I begged my mom to sign me up and she agreed. I joined the club and loved it. I did pretty well and I’ve been doing track for about seven or eight years now. That’s how it all started.

MH: Tell us about your favourite track and field moment.

EH: I have quite a few! One of them was in grade 12. The year before, I had a lot of injuries and went through physio because I had tendon issues in my foot. I couldn’t run for about three months. That’s when I started focusing more on the 400m, since I wasn’t necessarily the fastest in the 100m or 200m.

At provincials that year, I had one of the slowest qualifying times and the worst lane assignment. I didn’t think I’d do very well, but I ended up coming second in B.C. at that meet. I ran a three to four second personal best in the 400m, which was huge, especially because it helped me get recruited for university.

Another big moment was just this past April. We were starting our outdoor season in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletic Conference. My coach wanted me to push my times lower. At first, my races weren’t great— it’s always hard transitioning from indoor to outdoor season. But at the third or fourth meet, Battle of Sparta, I ran a massive personal best. I dropped my time down to 51.92 seconds, which was unexpected. I stuck to my race plan, didn’t worry about the others and it paid off. I won my race, and my coach said I had one of the best performances of the meet.

MH: What are you most looking forward to for the next season?

EH: Quite a few things! Since we’re moving into the NAIA Conference, I’m excited for the outdoor season.

My biggest goal is to run sub-50 seconds in the 400m this year. My teammates believe I can do it, my coach believes I can do it and I believe it too. I’m also really looking forward to our 4x400m team. We should have a strong group, and I think we’ll do well in our meets.

MH: What does your future look like after your time at TWU, both in track and field and in your career?

EH: On the sports side, like every kid, I’ve dreamed of becoming an Olympian. I still have a lot of work to do, but the goal is to keep improving, lowering my times and maybe one day competing at the Olympics. We’ll see where it takes me.

For my career, since I’m in human kinetics, I’m considering becoming either a physiotherapist or a kinesiologist. Physiotherapy would mean going to grad school, whereas kinesiology doesn’t always require that. Either way, I enjoy working with people and in the field of athletics, so I see myself staying connected to sports and health in some way.

Hamdan Sadiq Chaudhry

The 300 is more than just a fan club at Trinity Western University; it’s a movement. This student-led group works to make Spartan home games an experience where energy, noise and participation define the court as much as the athletes themselves. At its core is the belief that fans have the power to impact the outcome of a game by transforming the atmosphere.

“The 300’s mission is, rather than simply viewing a sports game, to join into the competitive environment and impact the game through changing the atmosphere of the court,” said current leader Riley Vanderveen, who previously co-led the group with fellow student Ty Johnston.

Inspired by the passion of European football crowds, Vanderveen believes that fans can be just as involved in the action as the players.

“Being a part of the crowd is why you go to the games—not just the sport the fans came to see,” he said.

In his first year at TWU, Vanderveen noticed a gap in crowd participation. Rather than staying quiet, he rallied his friends and began chanting and celebrating. His thunderous efforts soon caught the attention of the university staff, who invited him to lead the 300.

“I figured I would lead,” he said. “But not without a partner, so I needed to get the ultimate hype man, Ty Johnston. Doing The 300 with Ty is so fun because I can build off of the energy he exerts, making it less intimidating to start chants, run games or be on the mic.”

For Vanderveen, the vision for the 300 is all about shifting fans from passive spectators to active participants.

“Ideally, fans would realize that in order to have a hype environment, it takes individual participation. It takes everyone. If people want a hype environment, it requires activity! Fans need to be responsive to the environment. Essentially, it would be really cool for the environment of sports games to shift from consuming to creating.”

He also hopes to build a stronger sense of welcome for fans entering the gym. In the past, crowds often walked in and went straight to their seats without any interaction. Vanderveen believes that needs to change.

“A good welcome is important for people to feel accepted and comfortable enough to participate,” he said. “So welcoming fans well will improve the participation.”

He wants everyone who engages in the 300 experience to feel just as involved in the action as the Spartans on the ground.

From chants that echo across the Langley Events Centre to cheers that rattle the walls of the David E. Enarson Gymnasium, Vanderveen sees the 300 as more than a fan club—it is a culture shift at TWU. With student leaders like him and Johnston at the helm, the group is working to redefine what it means to be a Spartan fan: loud, passionate and united in spirit.

Parnika Trivedi

When I first entered the Graduate Collegium, It felt like opening the first page of a new book. I smiled in peace, feeling welcomed; miles away from home.

Yet for me, it began in another light: one evening, after dinner, on a bench bathed in soft glow, the night air carrying the song of insects. Outside the closed gates of the building, I felt it: peace. A sense of belonging.

Months passed in a haze, each day turning its own quiet page; mornings with coffee runs and classes, afternoons wrapped in never-ending assignments, evenings on the couch we claimed as ours, drinking hot chocolate after class, finding friends in once-unfamiliar faces.

And the seasons changed. Nervous feet carried me once again into the same buzzing place. The next chapter had begun; a smile, pasted on; real yet trembling.

My first pot of coffee brewed, a badge pinned to my t-shirt. My first job

Serving the place that once served me, creating warmth, building community.

I came in as a student leader, and the year turned like pages in a well-loved book. Now, every nook, every corner holds laughter, memories strung with Christmas lights, the printer humming through winter evenings, summer afternoons alive with BBQ luncheons,

my playlist drifting through the speakers, laughter over team dinners, early mornings with pancake breakfasts, the scent of chocolate muffins in the air.

Like unfolding memories on soft paper; so warm, so familiar.

A place known. A memory lane. A new family.

An opportunity to lead with heart.

And as every favourite story must, this one reached its final page. We gathered again, for our last event.

We passed the torch, said farewell, laughed through tears, smiled with heavy hearts, and cleaned the final coffee pot.

As I wiped the board, there it was, written in red ink; the title revealed itself all along: Home Away From Home.

Rea Klar

The smell of cumin and cardamom filled our kitchen every Sunday. My grandparents’ voices rose in Punjabi, steady and warm, weaving with my parents’ conversations and my brother’s laughter. Around that table, the world stretched far beyond our Canadian street.

I was in Punjab—not as a visitor, but as a grandchild growing up inside a homeland, carried across an ocean and rebuilt under our roof.

My parents had come first, carving out a life in Canada with the hope that their children would grow into new opportunities. Later, they invited my grandparents to join us, and suddenly three generations lived together.

The house was never still. My grandfather’s radio hummed in the mornings, Punjabi hymns rising with the sun. My grandmother prayed aloud before breakfast, her voice steady and unwavering. My parents traded stories and responsibilities over cups of chai. My brother and I raced through the house, slipping easily between English and Punjabi.

At home, Punjabi was the air we breathed. My parents made sure of it. They corrected me if I slipped into English when speaking to my grandparents. They reminded me to answer in Punjabi, to remember who I was, to hold onto the culture they had carried across the ocean.

But at school, the opposite pressure pulled at me. English made me invisible, just another Canadian kid. If Punjabi slipped into my speech on the playground, I was met with confused looks or mocking imitations.

Connecting with classmates meant letting go of pieces of myself. Holding on at home, letting go at school. Each day felt like stepping across a border.

Williams Lake was small and steady. The community was tight-knit, life predictable: rodeos, hockey games, school concerts and town parades. Everyone seemed to know everyone. The air smelled of pine and woodsmoke.

I loved the familiarity, but inside that comfort I carried difference.

It showed up in the smallest ways. My friends brought sandwiches of white bread and ham. I unwrapped rotis from foil. They spent weekends fishing or camping. I spent mine inside with cousins, watchyoguring Bollywood movies or listening to stories my grandparents told about Punjab. They talked about cabins at the lake. I listened, smiling politely, with nothing to add.

Sometimes the teasing was harmless, and I learned to laugh along. But other times, it stung.

Canadian kids reminded me that I looked different, that I wasn’t like them. South Asian kids reminded me that I wasn’t Indian enough, calling me “white-washed” for speaking English so easily or not knowing every Bollywood reference.

I felt like I was constantly being picked on from both sides. Indians from India told me I was too Canadian. Canadians told me I was too Indian.

“They each knew one homeland, while I carried two, and somehow two always felt like not enough.”

The confusion followed me home.

My parents, who were balancing their own in-betweenness, pushed me to keep Punjabi alive, to honour their traditions. But they also saw how much Canada was shaping me.

They wanted me to succeed in school, to blend in enough to have opportunities they never had.

It left me in a tug-of-war: Canadian outside, Punjabi inside. Sometimes it felt like I was disappointing both sides at once.

Trips to India only added new layers. The moment we landed, I felt the shift.

My parents told me not to speak English in public, especially in bazaars. If people heard my accent, they would know I was Canadian. They would treat me differently, maybe charge more, maybe see me as soft or spoiled.

I remember walking through crowded markets, the air thick with dust and the smell of fried snacks, my eyes wide at the swirl of colors and noise. I longed to ask questions in English, but I swallowed the words.

My parents’ warning sat heavy in my throat: don’t let them find out. In those moments, I wondered which part of me I was hiding, and why I couldn’t ever seem to be both.

India was vibrant, alive and in many ways familiar. I laughed with cousins, shared meals that lasted long into the night and walked in

the villages my parents once knew.

But even in the laughter I felt distance. My accent gave me away. My Canadian habits slipped through.

I was welcomed with love, but always noticed as different.

Back in Canada, the cycle repeated in reverse. I was too Indian for my Canadian peers, too Canadian for my Indian ones.

My parents’ warning sat heavy in my throat: don’t let them find out. In those moments, I wondered which part of me I was hiding, and why I couldn’t ever seem to be both.

India was vibrant, alive and in many ways familiar. I laughed with cousins, shared meals that lasted long into the night and walked in the villages my parents once knew.

But even in the laughter I felt distance. My accent gave me away. My Canadian habits slipped through.

I was welcomed with love, but always noticed as different.

Back in Canada, the cycle repeated in reverse. I was too Indian for my Canadian peers, too Canadian for my Indian ones.

I learned to adapt, to switch effortlessly, to read a room and know which version of myself to present. But underneath, I carried the ache of never being fully seen.

Leaving Williams Lake for Langley felt like another crossing.

Langley was bigger, busier, more diverse and yet also more anonymous. After years of familiar faces and neighborly waves, I was surrounded by strangers who never looked up. The sidewalks were louder, the days faster.

My dorm room was too quiet after a childhood in a multigenerational home. I missed the hum of life: my grandparents praying, my parents talking late over chai, my brother thundering up the stairs.

The silence pressed in on me. It reminded me that home was not just a location, but the people and voices that made a place feel alive.

At the same time, Langley gave me things Williams Lake never could. In classrooms, English carried me through essays and lectures.

On buses and in markets, Punjabi returned in unexpected ways: overheard conversations, greetings from strangers, phone calls home.

For the first time, both tongues had a place in my everyday life. And yet the tension never vanished.

I felt it when I returned to Williams Lake and could not explain why my life no longer matched the rhythms of my childhood friends.

I felt it in India, where cousins saw me as Canadian no matter how fluent my Punjabi.

I felt it in Langley too, when classmates bonded over cultural references I didn’t know, or when I struggled to explain to them what it meant to grow up balancing two homes, two sets of expectations, two versions of myself.

Too Canadian in India. Too Indian in Canada. Too rural for the city. Too restless for the town.

Always shifting, never still. My identity moved

as quickly as my tongue. The fear lingered: I would never find a true homeland.

For years that fear felt heavy. The confusion was constant.

I felt like an outsider among Canadians who only knew one homeland, and like a stranger among Indians who also only knew one.

I carried both, and instead of being celebrated for it, I often felt questioned. The comments, the teasing, the constant sense of being slightly out of step wore me down.

I wanted to belong fully to something, to be understood without needing to explain.

“But I have since realized I am not the only one. There is a whole group of us, children of immigrants, first-generation Canadians, who live in this in-between space.”

Our parents push us to hold onto a culture we never fully lived in, while schools and peers demand that we adapt to a culture our parents never fully understood.

We switch tongues, switch mannerisms, switch selves, depending on where we stand. We are asked to integrate and to preserve, to blend in and to stand apart, all at the same time. My story is also theirs.

The Nigerian Canadian student who has never been to Lagos but still eats jollof rice at home.

The Filipina Canadian whose parents tell her not to forget Tagalog, while her classmates tease her accent.

The Chinese Canadian who celebrates Lunar New Year with family, then answers “Christmas” when classmates ask about his traditions.

The Mexican Canadian who dances at quinceañeras with cousins, then explains tacos in the school cafeteria as if they are foreign.

The Indigenous Canadian who feels the weight of living between ancestral traditions and the pressure to assimilate into a country that was built on their land.

We are stitched together by this strange and fragile thread: never quite enough for anyone else’s standards, yet carrying more than one homeland inside us.

For a long time, I thought this made me less. I longed for the simplicity of belonging fully to one place, one culture, one identity. I envied those who never had to explain themselves.

But I have begun to see it differently. To live with two homelands is not a curse. It is a kind of doubling.

It has taught me adaptability, empathy and the ability to hold multiple truths at once. It has given me the eyes to see how culture shapes people, and the ears to listen when others share their own struggles of belonging.

Here at this school, I have come to understand that the longing for a single homeland will never be answered by geography.

India and Canada, Williams Lake and Langley, Punjabi and English—each is a piece of me, but none is the whole. I have learned that my true homeland is not here at all. It is in Heaven,

where every tongue is understood, where every culture belongs and where the divisions that once defined me will finally fall away.

The in-betweenness that once felt like a burden now feels like a glimpse of something larger, a reminder that I was never meant to be fully at home here.

I do not stand between two homelands anymore.

I walk with them both, carrying their tension and their beauty, while keeping my eyes fixed on the homeland that waits above, where all tongues will speak the same language of belonging.

I miss the place of my childhood,

My teenage years and twenty-something days.

I cannot live there again, but the place holds my heart—

The echoes and memories remain.

I miss my dad in the kitchen.

His pancakes and bacon.

My dog and I playing, cuddling on the floor.

Perched on bar stools, talking

Until mom woke up.

I miss the logging road’s winding trail,

Sprinting the steepest part after my dog,

Or loping my horse up the big hill.

My dog fishing for rocks in the creek,

Forever chasing the sunset at the end.

I miss my room:

Bookshelves and art.

The bed, cradling tears and laughter, Angst and repression of family drama.

My dog watching, sleeping, as I study.

I miss life there.

Sushi on the beach, Late nights at the barn,

Gardening, barefoot with music in my ears,

Hearing Dad’s truck before he enters the driveway,

Laundry on the line,

Trail rides with friends,

My dog soaring over the fence after his ball,

My sweet nephew and niece.

My heart aches for the Island fields of green, yellow or white:

Lush grass with the first sugars of spring, Golden rounds of hay at the end of summer,

Perfect cover of snow as it blankets winter.

The country roads always led me home,

The ocean swallowed my thoughts,

The forests absorbed my emotions,

The people: my joy and sorrow.

Leaving it behind feels like I’m lost,

No identity, no grounding, no place called home.

A wanderer,

Compass needle spinning aimlessly, Circling the same trees,

Desperate for escape, yet comforted in chronic detachment.

The city here is cold, contrasting sharply with the winter of my former community:

Harsh grey lines of concrete, Headaches from blinding lights, Foreign towers of corporate buildings.

Only God’s beauty is here:

Sunrise and sunset, Snow on the mountain,

The kisses of a horse,

Hugs from a close friend.

Finding peace seems futile:

The cozy rental is not home.

The friends did not stay.

Horses are statements of wealth, not companions.

The absence of a dog’s hug after work.

Seeking security seems unattainable: I get lost all the time.

No familiar neighbors while shopping.

Homeless faces I cannot recognize.

Facebook groups that do not create

family out of strangers.

Grasping for belonging seems worthless:

Friends leave or fade.

I say “at home” but I do not know where that is.

There are no safe places—only familiar ones.

It’s not the loss and gain of things.

It’s that I cannot go back to what I had, And no familiarity in moving forward.

So I just feel like I lose.

Does the longing leave or stay?

Is it the familiarity I yearn for,

Or the goodness apart from it?

Did the chaos burn into my brain as comfort?

Am I only missing familiar fears and anxiety?

Does this wanderer find peace in the newness?

Or does the loss remain,

While the good shifts around it?

Will I return to the place that haunts me?

Or will the ache of loneliness and discomfort settle into familiarity?

Did I trade past scars for future wounds, Or does displacement settle through time, Reshaping, softening into acceptance?

“The One Who Only Reads the Declassifieds”

Name: Kofi

Belongs to: Cristina

Breed: Chihuahua/beagle mix

Age: 13

A senior dog with a love for gossip, Kofi cannot be bothered to read a long article. She gets right to it and looks for the declassifieds in every issue of Mars’ Hill. She’s probably hoping for someone to mention how cute she is or how mysterious she looks when sipping on her Starbucks coffee while finishing assignments at the Pavilion.

“Performative Reader”

Name: Brynny

Belongs to: Faith

Breed: Mini Australian Shepherd

Age: 2

“Sports Paws”

Name: Pepper

Belongs to: Emma

Breed: Morkie

Age: 8

When Pepper is not napping, she is hitting the courts in her Lakers jersey. Fully immersed in the world of sports, she is always on the ball–literally. Whether she is barking for a big play or calling out a foul, she truly knows how to keep the crowd howling.

While she claims to read each issue and frequently brags about her support of print media, Brynny has the attention span of a modern 12-yearold, and can only sit through Tik Toks featuring dogs being dressed for rainy walks. Despite this, she thoroughly enjoys the pictures.

“The Op-Ed Enthusiast”

Name: Scout

Belongs to: Sadie

Breed: Bernedoodle

Age: 6

It doesn’t really matter that the only words Scout knows are “park,” “walk,” “cuddle” and “toy,” nor that if you spell them out instead of saying them, she won’t know what they mean. She loves to read your opinions and has plenty of her own, too, such as there’s no such thing as too many treats.

Breed: Mini Australian Shepherd

Age: 3

An old soul, Austen has discerning literary tastes. He enjoys late evenings reclining by the fire, drinking a strong cup of tea and soaking in the wisdom of his fa vourite poets. While he is drawn to the works of writ ers such as W.H. Pawden, John Treats and Mary Olifur, he tends to shy away from the likes of Ezra Pound.

Are you an artistically-or creatively-minded person? Do you want a place to work on your design skills? Mars’ Hill wants you!

We’re still searching for . . .

Email marshill@gmail.com for more information or apply using the QR code below! We’d love to have you.