8 minute read

Waterfowl and Ranching

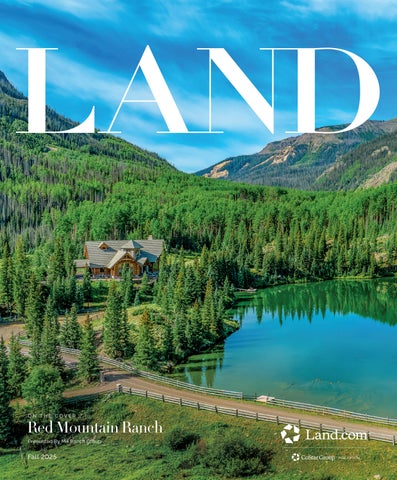

from LAND Fall 2025

Q&A

5 Questions About

WATERFOWL AND RANCHING

A Q&A with Robert "Bob" Sanders

STORY By Lorie A. Woodward

In the 1930s, many wildlife species throughout North America faced severe declines due to habitat destruction from unsustainable farming practices, wetland drainage and market hunting pressures, leading to critically low populations of species like the wild turkey and American bison as well as migratory ducks and geese. The situation was heightened by a protracted drought that prompted the Dust Bowl, further damaging habitat and limiting surface water supplies.

This looming wildlife crisis prompted significant conservation action, including the Civilian Conservation Corps' habitat restoration efforts and the establishment of numerous national wildlife refuges.

The crisis, despite occurring at the height of the Great Depression, also spurred the passage of landmark legislation such as the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937 (Pittman-Robertson Act) and the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act of 1934 that levied taxes or fees, dedicated to conservation, on sportsmen.

For instance, the Federal Duck Stamp was created in 1934 with the passage of the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act, to address dwindling waterfowl populations and wetland habitat loss. Sales of the stamp, which is available to anyone but required for waterfowl hunters, provide the primary funding for the National Wildlife Refuge System, raising more than $1.2 billion to conserve millions of acres of vital wetlands and other habitats since its inception.

In 1937, a small group of waterfowlers, visionaries and community leaders set out to save North America's waterfowl populations while celebrating the continent's solid waterfowling heritage. Stressing the critical role wetlands play across North America, the organization, Ducks Unlimited, committed to this mission. Through the support of both hunting and non-hunting waterfowl enthusiasts, DU has protected or restored more than 19 million acres of habitat across North America in the areas most important to ducks and geese.

I sat down with Robert “Bob” Sanders, Manager of Montana Conservation Programs for Ducks Unlimited, on the Land.com Podcast to discuss the overlap of healthy waterfowl populations and ranching. To catch the entire conversation, listen to “Duck, Duck, Landowner” Episode 28 of the Land.com Podcast.

1. What is the mission of Ducks Unlimited?

RS: Our duck head logo is pretty famous, even though some people mistakenly think it represents a line of clothing. Other people only know about our banquet system that raises money for conservation, but we have an applied conservation side with programs in all 50 states. That’s where I work—and I call it our fun side.

Our priority focus is keeping as much of the wetland-pocked landscape in the Prairie Pothole Region, which is the breadbasket of North America’s duck production, as intact as possible. While we also work in places where ducks migrate for the winter like Arkansas, Louisiana and the Texas Gulf Coast, our primary focus is on the Prairie Pothole region of Montana and the Dakotas. If we don’t have quality breeding grounds for waterfowl then migrating and wintering habitat will be irrelevant.

2. What is the Prairie Pothole region and why is it important to waterfowl?

RS: It’s a vast region of depressional wetlands that are found in the Canadian prairies as well North and South Dakota, and Montana with small segments stretching into Minnesota and Iowa. These shallow wetlands or “potholes” are crucial as nesting grounds for North American waterfowl.

These unique wetlands were created about 7,000 to 8,000 years ago during our last Ice Age. Glaciers moved down from the Hudson Bay region of north central Canada. As the glaciers moved south, they carried rocks of all sizes with them. When the glaciers melted, they left behind the rocks and big chunks of ice that had broken off and gouged the landscape, creating shallow, water-holding depressions of various sizes and depths that are scattered throughout the mid-grass prairie. Because all the wetlands are not identical— some are deeper and permanent, while others are shallow and ephemeral—neither are the plants nor the insects that inhabit them. As a result, this region can support more than 30 species of ducks in close proximity to one another because the wetland diversity means that different duck species can find the food and habitat that fit their specific needs. Because their food requirements and foraging techniques differ from species to species, they are not competitors.

There is a misconception that agriculture and wildlife conservation are mutually exclusive. It’s almost the exact opposite, especially the grass-based side of agriculture.

3. Describe the life cycle of a duck and the role that wetland habitat plays in its development?

In a wet spring, the combination of melting snow and rainfall fills the prairie wetlands. The water chemistry, depending on the depth and permanence of the wetland, dictates the vegetation. You’ve got the typical wetland plants that people imagine, sedges, rushes and cattails, as well as grass. The vegetation provides nesting cover as well as seeds and serves as habitat for insects, another important food resource.

Take a mallard, for example, because they are common and the male’s green head makes them recognizable. Generally, female mallards lay their eggs beginning in early May. At the rate of one egg per day, it takes eight to 10 days to lay an average clutch. Duck eggs are 80 percent to 90 percent fat and protein, so to produce eggs, the hens

need a diet rich in protein, fat and calcium. Seeds are an insufficient source, meaning that the hens and later the hatchlings need aquatic insects and other invertebrates.

The hen incubates the eggs for about 28½ days. Contrary to popular belief, the hens don’t sit on the eggs to keep them warm, but to keep them cool. Unless the eggs completely freeze, cooling down just slows the development process, but getting too hot can kill the developing ducklings.

After they hatch, the ducklings will spend 24 hours to 48 hours on the nest. Then, the hen will lead them to a wetland and she will watch over them while they feed. Hopefully, the wetland is rich in aquatic insects and invertebrates because that’s what the ducklings need to thrive. It takes about 58 days before they’re able to fly, so the ducklings are especially vulnerable to predators during that period. Staying on the water with access to dense vegetation is the key to duckling survival.

During this period, what ducks really need to avoid is moving overland, which is why it is so critical that we keep large tracts of wetland and grassland habitat intact. If a shallow wetland dries up, ideally the ducks can move right next door instead of having to navigate stretches of bare farm ground or sub-divisions to find their next suitable home.

4. What role does cattle ranching play in the reproductive success of waterfowl?

RS: There is a misconception that agriculture and wildlife conservation are mutually exclusive. It’s almost the exact opposite, especially the grass-based side of agriculture. Ranchers want to see grass and water for their livestock, and we want to see the same things for ducks. Other groups want to see the same things for elk, deer, antelope and even songbirds and butterflies.

All these species need habitat. Habitat exists on ranches. Successful ranching keeps wild places open, ensuring that rangelands and forests remain “neighborhoods” for wildlife instead of strip centers and suburbs.

5. What tools does Ducks Unlimited use to help keep ranchers—and waterfowl—on the landscape in the Prairie Pothole Region?

RS: Our most effective tool is honest, straightforward communication. Relying on partnerships, working relationships with agencies, and various programs, we can bring a lot of resources to bear, but we have to know what the ranching family’s goals are for their operation and their land.

For some people, it may be to keep their land intact to pass along to the next generation or to get an infusion of capital or maybe both. In those cases, a voluntary conservation easement, where landowners forego developing their property in perpetuity in exchange for tax credits and possibly payment for those development rights, may be a good option.

In other instances, landowners may want to convert farmland back to grassland or build cross-fences and install a stock pond or water distribution system to improve their grazing system or a myriad of other improvements. We have knowledge of and access to a host of incentive- and cost-share programs that will help landowners enhance their operation and their conservation efforts.

Our network includes state and federal agencies, conservation organizations and other NGOs that are dedicated to helping put conservation on the ground, so landowners and wildlife will continue to thrive.

Join the Conversation

To listen to Episode 28 "Duck, Duck, Landowner" with Bob Sanders (and all the other episodes) of the Land.com Podcast, click here or tune in on Spotify or Apple.

For more information, check out the following online resource https://www.ducks.org/