Developing oracy through the Harkness Model in Lower Sixth History Classes

Amy Angell - Teacher of History

What is oracy?

There has been a renewed ephasis on the importance of oracy in education, with the Oracy Education Commission declaring that it should be the ‘fourth R’ along with reading, writing and arithmetic [1] Kier Starmer stated in July 2023 that ‘ an ability to articulate your thoughts fluently is a key barrier to getting on and thriving in life’, and indeed his new Labour Government has recognised it as a crucial part of a child’s education, and key in preparing young people to be engaged and articulate citizens [2]

But what is oracy and is it just a new political buzz word? The concept has actually been around for over half a century, as the term was first used by Professor Andrew Wilkinson in the 1960s, when he defined it as ‘the ability to use the oral skills of speaking and listening’ [3] In many ways this is natural and essential to our human nature, and young children will, in normative circumstances, learn language and in turn use this to interact with others Nevertheless, most children need adults to model and practice good oracy, if they are to become effective speakers and listeners themselves This does not end with early childhood, and right up to teenage years young people need effective guidance in oracy education As the communicative experience outside of school varies, schools should see it as their place to develop spoken language skills and embed oracy education into the child’s school experience

This can be done in many practical ways:

Active listening and engagement in class

Meaningful class discussions to develop critical thinking and communication

Presentations to provide the opportunity to develop confidence and communication

Dialogic teaching, where teachers use purposeful dialogue to guide students learning and understanding whilst modelling effective communication

Structured questioning that encourages students to articulate their thoughts and promotes deeper understanding

Reading aloud to foster vocabulary development

Harkness Model

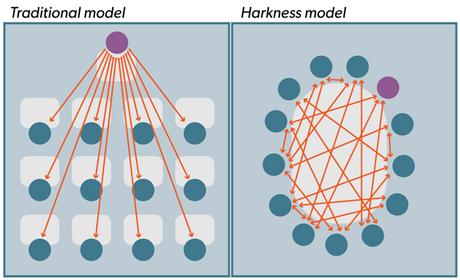

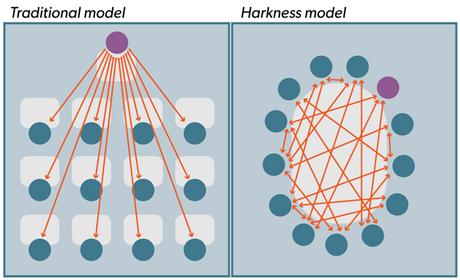

One particular way that oracy can be fostered in the classroom is through what has become known as the Harkness Model. In 1930 a philanthropist called Edward Harkness donated millions of dollars to Exeter Academy, hoping to find a way for student to feel ‘encouraged to speak up ’ [4] What was developed through this funding was a collaborative teaching strategy, mainly used for older students, that put preparatory work, oracy and independent learning at the heart of teaching

In simple terms, most of us will think of this as university seminar style learning, where students are expected to come having read around the topic and in a circular group discuss key issues, facilitated by the teacher or lecturer As Smith and Foley said this is a great way of getting ‘students to make the discoveries for themselves, to get them to draw their own conclusions, to teach them how to consider all sides of an argument, and to make up their own minds based on analysis of the material at hand ’[5]

This year we were excited to try this model in our L6 History classes, hoping that it might also relieve other issues that we were having As well as developing a students communication skills, we hoped that it could develop their written articulation of ideas in examination settings, and break up content-heavy lessons All A Levels experience the issue of ‘there is not enough time’, and as curriculum demands grow it is tempting to depend further on core textbooks and didactic strategies However, this also led to our students having decreasing ability to learn independently, and it becoming harder for teachers to promote wider reading We can all agree on the value of wider reading and long for the day when our students walk into the lesson with well-read academic books spilling out of their bags However, how we get there is not straightforward Furthermore, the ability to argue does not necessarily naturally flow from purely reading more [6]

Therefore, the Harkness Model is a good way to bridge this gap, providing students with structured reading and encouraging higher order arguments through oracy

What we hoped to achieve

Independent learning – Students will have worked independently at home to complete reading and bring their notes to the class

Articulating ideas – Students will have to communicate their ideas clearly to classmates, and learn what makes their argument stronger They should start to include more factual detail to support their points, directly respond to evaluative points and show counter arguments, and use the relevant academic vocabulary They should also learn non-verbal gestures, such as eye contact and facial expressions

Listening – As well as speaking, the style of teaching forces students to listen to others so that they can respond accordingly Not interrupting, not echoing what has been said and keeping on the relevant topic

Confidence – Students should take more risks as they become more confident in their knowledge of the subject and also their ability to share their views They should go deeper in challenging others and thinking critically about connections to other topics, texts or subjects

Disagreeing well – Students should learn that you can disagree on some aspects of a debate and how to do this politely and amicably

What we did

In order to try this out in the History department, once or twice a half term we set our Lower Sixth history classes a ‘seminar’ The key stages were:

1 Develop an engaging enquiry question It is important that it is a wide enough topic with many avenues of discussion Examples we have used have been ‘Was Hitler a strong dictator?’ or ‘How totalitarian was the GDR?’

2 Set clear preparatory work It is important that this is completed ahead of the session As we know sixth formers can struggle with ‘reading around’ so it is key to give realistic and targeted reading For us this has tended to include a number of relevant articles, a podcast on the topic and maybe a documentary or film

3.Create a collaborative environment. Although the Harkness Model has become synonymous with the oval table this is not necessary, and classrooms can be rearranged to suit or the meeting rooms in Number 100 booked ahead

4 Facilitate discussion Students were given a list of questions that they might consider under the wider enquiry question, and then these are used as good starting points for teachers to initiate discussion However, the teacher’s role should be to prompt and not to direct discussion, maybe through redirecting discussion, asking leading questions or playing devil’s advocate

5.Assess. We added this stage as we wanted to encourage students that there was a purpose to the seminars, and their progress would be judged The Head of Department developed a mark scheme that focused on: preparation, knowledge & understanding, quality of arguments, questioning & engagement

Did it work?

Overall, we found it amazingly successful in several areas Our research has been mainly qualitative, but through observations, comparing the quality of work with previous years, and student questionnaires, it is clear to us that that the model has had a beneficial effect on our Sixth Form teaching

Oracy

The ability and confidence of students to articulate their ideas and to express their views has improved vastly over the year

Student views:

‘I think its really useful in practicing to raise opinions academically and articulate confidently Not only do these skills help my History course and revision, but are useful for any setting where oracy is needed: a vital skill so I have found it a great addition ’

‘I enjoy being able to form a argument that I had perhaps not thought of before, just by discussing a common topic with my classmates’

Depth of knowledge

Students’ understanding of the course and key topics has been much deeper than previously, with a wider awareness of different academic interpretations and the evidence to support each one

Student views:

‘It forces me to acknowledge and understand other stances and help me collect information for my essays Seminars consolidate my understanding and force me to deepen it’

‘Having to think how to back up your statement and hearing wider ranges of opinions that aren’t from the textbook Sometimes you have to debate something on the spot and then I feel I know the topic really well ’

Wider Research

The requirements force students to read more widely than they usually would, and access different styles of material This has helped their knowledge, vocabulary and articulation

Student views:

‘I enjoyed researching and going outside the textbook Seeing how the historiography has changed’

‘I have enjoyed where there is a documentary to watch before them as they are very interesting to develop my understanding’

Flexible thinking

We were able to view students change their minds more easily, and respond to new information that others brought Rather that viewing this as negative, students recognised how flexible thinking is desirable

Student views:

‘I changed my mind quite a bit which made me more apt to consider alternative interpretations’

‘Having the opportunity to hear other people’s views has given me the capacity to really think for myself and form my own opinions’

Written work

When a seminar came before an essay topic and students had the opportunity to argue and discuss ideas first, we found that students written work was far more detailed and evaluative, with strong and consistent arguments running through

Student views:

‘They help me learn better, due to the debate and having people pick apart the strengths and weaknesses of a point, which can then be used in an essay ’

‘I find it really easy to remember my argument when I have had to speak about it ‘

‘Having the seminars has helped in quickly forming essay plans because you know the content better after having discussed it and evaluation is easier when you have heard other people’s counter arguments’

‘I think through seminars I learn and understand topics in greater depth, with a justified and well thought out argument that I can easily access when writing essays in the exam ’

Enjoyment of the Subject

An unintended consequence was how much students enjoyed the format and the impact this had on their enjoyment of the content and subject

Student views:

‘I love the actual seminars, and I love debating ’

‘It’s something I wish that I could have done earlier on in school ’

What now?

We have been pleased with how the Harkness Model has improved our student’s oracy and written work in History, and so we will continue to embed this in the L6 History course We are also going to do similar in Upper Sixth, now that this cohort are used to the style of learning

However, the usefulness of this model is not limited to History or Sixth form It can be adapted for lower and middle school classes, something we are planning to experiment with next year, but it is also relevant across the curriculum, in building up key skills and attitudes Interestingly, none of our students felt that it could be used effectively outside of History, but they should be proved wrong! Whist it is ostensibly easier to see the direct relevance in humanities subjects, oracy and independent learning is vital in all curriculum areas This is only one model that exists to encourage these skills, but it is one our department can highly recommend and hopes to see spread more widely throughout the school

Bibliography:

[1] We need to talk, The Oracy Education Commission, October 2024

[2] Sky News, 6 July 2023, Sir Keir Starmer pledges speaking lessons for children as he promises education overhaul under Labour | Politics News | Sky News th

[3] Education Brief: Oracy, Cambridge Assessment International Education, accessed: Education brief: Oracy

[4] Orth, Lacey and Smith, Hark the Herald tables sing, Teaching History, The Historical Association (June 2015)

[5] Smith, A and Foley, M (2009) ‘Partners in a Human Enterprise: Harkness Teaching in the History Classroom’ in The History Teacher, 42, no 4, p 478

[6] Bellinger, L (2008) ‘Cultivating curiosity about complexity’ in Teaching History, 132, Historians in the Classroom Edition, pp 5-13

How can we make learning ‘irresistible’?

Reflections inspired by John Tomsett’s ‘This Much I Know About Truly Great Secondary Teachers’ (and what we can learn from them)

Milly Williams - Head of Religion and Philosophy

In July, I had the pleasure of attending the Festival of Education at Wellington College, alongside five other colleagues from Kingston Grammar School Among the many inspiring sessions, one that stood out was John Tomsett’s talk, where he shared insights from his latest book, ‘This Much I Know About Truly Great Secondary Teachers’. A former headteacher and lifelong advocate for professional learning, Tomsett draws on a career spent observing classrooms not from the front, but from the back quietly watching, listening, and learning from the very best

I’ve always appreciated Tomsett’s writing He champions teachers as the single most important factor in student success, and despite his own wealth of experience, he remains deeply committed to learning from others Like him, I believe that the most powerful professional development comes from watching our peers, borrowing ideas, and experimenting with what we ’ ve seen His reflections from the back of countless classrooms offer a rich seam of insight reminding us that the most valuable professional growth comes from observing, sharing, and refining our practice together The book is framed by a fascinating dialogue between Tomsett and Professor Robert Coe, exploring the elusive question of how we define and measure great teaching Coe, known for his work on value-added metrics, has long sought a reliable way to quantify teacher effectiveness Tomsett, however, resists the idea that great teaching can be reduced to a number Their debate ultimately led to a collaboration on the Sutton Trust’s ‘What Makes Great Teaching?’, which went on to become the Trust’s most downloaded research report As Coe notes in his foreword, ‘observing classrooms is a lot harder than it seems ’ learning isn’t always visible, and teachers often disagree on what excellence looks like

So, Tomsett sets out to identify the common threads that run through truly great teaching He distilled his findings into nine behaviours, drawn from interviews and observations of eleven exceptional teachers While all are important and often interwoven, I’ve chosen to reflect on four that I believe lie at the heart of making learning truly irresistible and how we might nurture them in our own classrooms at KGS

1.Teach with Enthusiasm

Great teachers radiate energy not just for their subject, but for the act of teaching itself They are devoted to deepening their own understanding and making the curriculum come alive Chris McGrane, principal teacher of mathematics at Holyrood Secondary in Glasgow, puts it simply: ‘You’re doing your job if every child you teach thinks maths is all you think about ’ Tomsett himself reminds us, ‘If you are dulled by what you ’ re teaching, what chance do the pupils have?’ The teachers he observed were visibly enjoying their time in the classroom and that joy was contagious

Yet Tomsett also cautions against being overly fixated on the question ‘Have we got the knowledge?’ at the expense of asking ‘How is the knowledge acquired?’ He argues that the curriculum is more than a static body of knowledge it is a dynamic invitation into communities of learning Teachers must inspire and encourage students to join these communities, shaping not just what is taught, but how it is experienced

What’s the takeaway?

If we want our students to fully engage with the curriculum and take ownership of their learning, we need to think carefully and creatively about how we deliver it how we draw them in That means making space to share ideas, both in and across departments, reflecting on how they play out in practice, and inviting colleagues to observe and discuss what they see In doing so, we reconnect with the thinking and curiosity that first led us to our subjects

2. Explain Things with Clarity

Enthusiasm is important but it must be channelled with precision Tomsett emphasises the importance of clarity in curriculum delivery and lesson sequencing In the classrooms he visited, students knew exactly where they were, what was coming next, and what they were working towards

Modelling plays a crucial role here ‘Live modelling characterised by high-quality metacognitive talk,’ Tomsett writes, ‘makes visible the thinking process of the teacher expert.’ We must teach students how to think how to apply knowledge to unfamiliar problems

What’s the takeaway?

Clarity in curriculum delivery matters – we need to be ‘clear explainers’ We should sequence learning deliberately, make links to prior knowledge explicit, and clearly communicate what’s coming next

Explicit modelling especially when paired with metacognitive talk helps students understand not just what to learn, but how to think This kind of transparency empowers students to navigate unfamiliar problems with confidence

3. Have Genuinely High Expectations

High expectations weave through every example in Tomsett’s book, forming a consistent hallmark of great teaching Reflecting on his own English teacher, Dave Williams, Tomsett writes, ‘We cared because Dave cared ’ That sense of mutual respect and high standards is echoed by students of Suzy Marston, Director of Drama at Chesterton Community College, who say, ‘We learn our lines because she expects us to We have a fear of her being disappointed ’ It’s clear that her expectations create a culture where students strive to meet them not out of fear, but out of respect and shared purpose

But it’s not just academic expectations that matter Behavioural standards are equally crucial Tomsett highlights Garry Littlewood, subject lead for food and textiles at Huntington School, as a powerful example of how a teacher’s high expectations combined with meticulous planning, consistency, and quiet relentlessness come to be mirrored by students His classroom is built on a strong culture of commitment to learning, and his students consistently rise to meet that expectation

What’s the takeaway?

High expectations of effort, behaviour, and engagement are non-negotiable From the moment students walk through the door, we must establish clear routines and model the standards we expect The tone we set in those first few minutes shapes the learning that follows Stability, structure, and a shared understanding of what excellence looks like are essential

In Defence of Handwriting

Lottie Mortimer - Classics Teacher

Devices are becoming ever more prevalent in our lives Ofcom reports that 15-17 year olds spend an average of 5 hours 4 minutes a day online, which works out at 1 day 11 hours 28 minutes a week or approximately 77 days a year [1] 22% of secondary school teachers report that pupils use devices in more than half of their lessons (although a digital divide still remains with 70% of secondary schools having only enough laptops for less than 25% of their pupils )[2] As the use of technology by young people has increased in recent years, so has the scrutiny it faces: the government has published guidance for mobile phones in schools and there have been increasing calls for mobile phone and social media bans for under 16s [3]

In contrast, if you walk into my classroom, it’s most likely that you’ll see my classes writing in their exercise books, on a worksheet or on mini whiteboards over typing on their devices I realise that I am at risk here of being the caricature Luddite Latin teacher, teaching from a textbook originally written in the 1970s, who’s overly sceptical of technology I don’t oppose technology at all, but I do think we need to think very carefully how we use it, not using technology just for the sake of using it However, one thing that I do really value, especially as a teacher of languages, is handwriting With the rise of the technology, it is assumed that people no longer regularly handwrite but a recent YouGov poll shows at least 71% of adults still regularly handwrite notes and short lists [4]

Handwriting and Typewriting

Handwriting and typewriting, alongside spelling, make up the key component of writing known as transcription which refers to the physical skills which need to be developed to support the composition of writing

However, handwriting and typewriting are different skills with different cognitive demands

Take a moment and think about the complexity of the skill of handwriting Pupils need to combine the physical, visual and cognitive to develop automaticity In order to write a letter on the page, pupils need to use their fine motor skills to physically hold a pen and accurately manoeuvre it on paper to form the correct visual shape to represent the sound in the word which they are spelling Typewriting is not as complex a skill, with pupils pressing a button for the letter to be formed for them by a word processor

Furthermore, we compose texts differently depending on whether we are handwriting them or typing because typing gives us the ability to more easily review and edit texts Teachers of essay subjects are all too familiar with the challenges faced by pupils who insist on typing essays throughout the year when they will be sitting a handwritten exam at the end of their course.

EDIT Edit

Because of the ongoing discussions about a move towards digital examinations, Cambridge Assessment explored the literature surrounding handwritten vs digital scripts [5] They found that generally it makes little difference to scores whether scripts are handwritten or typed but “English language ability and computer familiarity could influence the results” Students whose English language ability was lower performed better when handwriting Similarly, those who had less experience using a computer word processor did better and wrote more when handwriting Furthermore, they found that pupils planned more carefully in handwritten exams because of the ability to more easily edit digital work

Why is handwriting valuable?

The recently published Writing Framework from the Department for Education states:

“The act of handwriting: supports letter recognition helps pupils develop their orthographic processing skills (the permissible letter patterns of the language), thereby supporting reading and spelling enhances memorising of new information

Research also indicates that handwriting rather than typing may produce better-quality writing ”[6]

Longcamp et al ’ s study in 2005 added to the large body of data suggesting that the movement of handwriting contributes to successful letter recognition [7] Two groups of pupils were trained to copy letters using handwriting or typing, and handwriting led to the better recognition of letters

Whilst this is useful to know for students learning to write, how is this relevant to secondary school teachers? Increasing research at university level also suggests that handwriting notes is better for memory [8]

One of the reasons for this is that students can usually type faster than they can handwrite which means that they can write down the lecturer’s words verbatim without needing to process the information Handwriting slows students down making them think more about the information in order to condense it to write it down

More of the brain is used when handwriting and there is a link between the completed motor action of writing and the understanding of what has been created This has now started to be researched with school aged pupils - Horbury and Edmunds findings were similar to the university studies that handwriting had a positive impact on conceptual understanding [9]

As a teacher of ancient languages, I have a particular interest in the role that handwriting plays in the development of early writing, especially as I teach Ancient Greek which uses a different alphabet Considering the claims made in the DfE’s Writing Framework, I would be very interested to read more research on handwriting and language learning

Supporting students with difficulties with transcription

Whilst I highly value handwriting, it is important to note how typing is a crucial skill used by many pupils who struggle to handwrite, including those with SEND needs such as dyslexia or mobility issues

Students who find handwriting difficult use valuable cognitive load on the act of writing itself rather than their learning Allowing these pupils to type removes this barrier and helps them to access the learning

The EEF’s report on Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools recommends that students who need extra support with their transcription skills (handwriting, typing and spelling) be quickly identified and supported so that their transcription skills become automatic [10] Some secondary schools may struggle to resource this specialist intervention and some pupils may feel demotivated by the prospect of handwriting support in secondary school The same report also identifies that providing a computer can help weaker writers, especially in conjunction with typing support Whilst for some pupils a laptop is an essential tool to help them access the classroom and a valuable reasonable adjustment, it may also be helpful to consider how we balance this with other forms of support that continue to nurture and develop students’ writing skills

I truly believe that handwriting has value and still deserves a place in a world becoming ever more digitised And if you are someone who hasn’t handwritten anything for a while, why not reacquaint yourself with the skill?

Bibliography

[1]https://www ofcom org uk/siteassets/resources/ documents/research-and-data/onlineresearch/online-nation/2022/online-nation-2022report pdf?v=327992

[2]https://assets publishing service gov uk/media/6 55f8b823d7741000d420114/Technology in schoo ls survey 2022 to 2023 pdf

[3]https://assets publishing service gov uk/media/6 5cf5f2a4239310011b7b916/Mobile phones in sch ools guidance pdf

https://www bbc co uk/news/articles/c8rejlezrp1o

[4] https://yougov co uk/society/articles/52273what-is-the-state-of-britains-handwriting

[5]https://www cambridgeassessment org uk/blogs /handwriting-versus-typing-exam-scripts/

[6]https://assets publishing service gov uk/media/6 86e7890fe1a249e937cbecb/The writing framewo rk pdf

[7]https://www sciencedirect com/science/article/ abs/pii/S0001691804001167

[8]https://www scientificamerican com/article/why -writing-by-hand-is-better-for-memory-andlearning/ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/095 6797614524581?ref=alexquigley co uk

9] https://nhahandwriting org uk/handwriting/articles/handwritte n-notes-versus-keyboard-notes-the-effect-onassessment-of-conceptual-understanding/ [10]

https://d2tic4wvo1iusb cloudfront net/production/ eef-guidance-reports/literacy-ks3ks4/EEF KS3 KS4 LITERACY GUIDANCE pdf? v=1753032789

Wider CPD opportunities

For insightful reflections on educational leadership and professional growth, Dr Jill Berry’s blog is well worth exploring. A former headteacher, she writes about leadership development, transition, and collaboration in schools: jillberry102 She leads a fantastic leadership course too (LIS ONLINE)

Hosted by Tom Sherrington and Emma Turner, ‘Mind the Gap’ educational podcast offers sharp, evidence-informed insights into teaching, leadership, and professional development.

Alex Quigley’s blog Making the Difference for Pupils with Dyslexia offers clear, evidence-informed strategies for supporting dyslexic learners in the classroom. Alongside practical teaching advice, he signposts excellent wider reading around the subject

In this recent blog, Mary Myatt invites teachers to rethink the difference between teaching content and ensuring students truly grasp it: I might have taught it, but have they got it?

Mary Myatt Learning