ART & ANTIQUE DEALERS

Thierry W. Despont: Modern Renaissance Man presented by Maison Gerard

Thierry W. Despont: Modern Renaissance Man presented by Maison Gerard

01 FOREWORD BY THE AADLA TEAM

02 COLLECTION SHOWCASE ANTIQUE PERSIAN BIDJAR RUGS presented by Douglas Stock Gallery

03 OBJECT PRESENTATION THE WADSWORTH ATHENEUM ART MUSEUM ACQUIRES ENAMEL COUPE from The European Decorative Arts Company

04 CURATORIAL FOCUS THIERRY W. DESPONT: MODERN RENAISSANCE MAN JUNE 4 - AUGUST 31, 2025

05 OBSERVATIONS, INSIGHTS, AND MORE ART, HISTORY AND STORYTELLING: THE MANY WORLDS OF COINS presented by Keith Twitchell

06 CURATORIAL FOCUS THE BLOSSOM & THE SWORD, PORTRAITS OF INDIA presented by Kapoor galleries

07 DEALER SPOTLIGHT MEET MARCY BURNS SCHILLAY of Marcy Burns American Indian Art LLC

08 A CLOSER LOOK A MARC VIBERT CONSOLE (1755-1760) MADE FOR ELIZABETH OF FRANCE (1727-1759) presented by L'Antiquaire & the Connoisseur

09 OBSERVATIONS, INSIGHTS, AND MORE TASTE AS INTENTION written by Clinton Howell

10 AADLA EVENTS TREASURES FROM THE ATTIC, ANNUAL APPRAISAL DAY AT THE NASSAU COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART presented by the AADLA

11

COLLECTION SHOWCASE FLOOR SYSTEMS OF THE WORLD TRADE CENTER presented by Robert Morrissey Antiques

Feel free to feature your collection or gallery in an upcoming issue of The League Journal. You may share select artworks or objects, an article about an upcoming exhibition, or insights about the latest developments in the art and antique market. The opportunities for submissions are infinite and diverse and we welcome all types of topics in this field. Kindly share any text and imagery to marketing@aadla.com

"Collector's Circle" will be a new recurring section in The League Journal that will pose one thoughtful question to all AADLA members. Each issue will share the diverse responses, offering a snapshot of perspectives from across the art and antiques community, and highlighting shared passions, emerging trends, and the stories behind the collections.

Can you share a moment when a specific detail— whether it was the provenance, craftsmanship, emotional resonance, or a compelling story—that made you decide to acquire a particular piece? What was it that truly sealed the deal for you?

Send us your response at marketing@aadla.com today, or reach out to use for any questions!

October 2025

OCTOBER 12 - 18

The Original Round Top Antiques Fair

Big Red Barn

OCTOBER 16 - 19

The San Francisco Fall Show

San Francisco, CA

OCTOBER 15 - 19

Frieze London

The Regent’s Park, UK

OCTOBER 31 - NOVEMBER 02

2025 Antiques + Modernism

Winnetka

OCTOBER 31

Princeton University Art Museum

Opening Princeton, NJ

NOVEMBER 06 - 10

Salon Art & Design

New York, NY

NOVEMBER 06 - 09

Art Cologne

NOVEMBER 07 - 09

The Delaware Antiques Show Wilmington, DE

NOVEMBER 13 - 16

West Bund Art & Design Shanghai, China

DECEMBER 02 - 06

Nada Miami

DECEMBER 05 - 07

Art Basel

Miami Beach, FL

JANUARY 23 - FEBRUARY 01, 2026

The Winter Show Park Avenue Armory New York, NY

→ →

Stay connected with the League beyond the Journal—follow us on Instagram (@the_aadla) and LinkedIn (@Art & Antique Dealers League of America) for member spotlights, behind-the-scenes glimpses, upcoming events, and more.

We invite all members to follow both pages and help us grow our online community this summer! And make sure you tag us on all your posts, #AADLAMember

@the_aadla

@Art & Antique Dealers League of America

@Art and Antique Dealers League of America

marketing@aadla.com

www.aadla.com

We hope you enjoy reading the sixth issue of The League Journal this fall, as the air turns crisp here in New York. Each edition is a point of pride, shaped by the thoughtful contributions of our members, and we always love learning about the exciting exhibitions, new acquisitions, and insightful happenings at your galleries and businesses. As we look ahead, 2026 will mark the Art and Antique Dealers League of America’s centennial—a remarkable milestone that gives us the chance to honor a century of scholarship, fellowship, and integrity in the trade. While we prepare to celebrate 100 years, we’re also focused on strengthening the ways we share our members’ voices and expertise with the wider world.

The League Journal has long been a vibrant showcase of the League’s remarkable members and dealers, and your contribution ensures it remains dynamic, engaging, and a true reflection of our community. For all issues, we welcome submissions on any topic within your specialty—whether it’s spotlighting recent acquisitions, discussing current market trends, highlighting exhibitions or events, or even sharing the history of your gallery.

We would love to feature your gallery and its collection, and your participation will help shape not only this issue but also the growing record of our shared legacy. Please don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions, and thank you in advance for your contributions as we look forward to the centennial and beyond.

Sincerely,

The AADLA Team marketing@aadla.com

DOUGLAS STOCK GALLERY

www.douglasstockgallery.com

Helen and Douglas Stock douglas@douglasstockgallery.com (781) 205-9817 21 Eliot Street (Route 16) South Natick, MA 01760

Today, we will review some antique rugs woven in the Bidjar area in northwest Persia’s Kurdistan province. Each example in this article was woven during the so-called “Persian Rug Revival” period that stretched from the 1870s to about 1915, the general era of World War I.

The region of Kurdistan province where antique Bidjar rugs were woven is mountainous. One of the benefits in that regard is that the sheep produce beautiful quality wool and the general area is a source of various natural dyes.

Most Bidjar rugs were woven by Kurdish weavers, generally women. Men tended to focus more on the dye production. The Kurdish people appear to love color; and Kurdish weavings not only from Bidjar but from Senneh, also in Kurdistan; and from Souj Bulagh, further north in Persian Azerbaijan, reflect this penchant for saturated tonality and often a wide and sometimes unconventional color combination which, in the best examples, elevate them as textile art.

Bidjar rugs, and I should note at this point that a “rug” is smaller than 6 feet by 9 feet, where a “carpet” is larger than 6 feet by 9 feet, are known colloquially as “The Iron Rug Of Persia”. Woven on vertical looms, the rows of knots, woven on the vertical foundation threads that are called “warp” threads” are separated by horizontal foundation threads referred to as “wefts”. In many types of antique Persian rugs, a single weft separates two contiguous rows of knots. In Bidjar rugs, the weavers typically use two, three or even four weft threads which are then compressed by the weaver using a metal comb and hammer. This produces a dense, heavy and generally exceptional durable fabric, making antique Bidjar rugs among the best selections for high traffic areas in a home.

In addition to their love of color, Bidjar weavers appear to have had an unusual interest in and, curiously, access to, given the somewhat remote location of the village, various designs, many of them based on early “classical” Safavid Dynasty period (circa 1501 to 1722) formats. The “Vase” design and “Herati” design are true classical period designs. Other formats, including the “Harshang” design of flowers and palmettes; the “Mina Hani” design of flowers and lattice work; the “Afshan” pattern of various flowers; the Split Arabesque design; various medallion formats; and the dramatic and often stunning “open field” designs evolved over time.

We are selecting some examples to feature here and, while this section served as a general overview of Bidjar rugs, the captions that appear underneath each respective rug will hopefully fill in additional information.

Some of the featured rugs are currently available from Douglas Stock Gallery, while others are from our Archives.

Words by Douglas Stock

Continue on page 4

1 of 5

4’9” x 7’3” Important Antique Bidjar Rug, Vase Design, Northwest Persia, Kurdistan Province, Circa 1900

Of very fine quality and displaying a remarkable range of colors, this antique Bidjar rug was woven in northwest Persia’s Kurdistan Province, circa 1900. The design has its antecedents in Safavid Dynasty period (circa 1501 – 1722) “Vase” carpets.

In this Bidjar example, polychromatic palmettes with ancillary flowers decorate the navy blue field. Colors include a light brown which has oxidized; camel; chocolate brown; grass green; madder red; sky blue; yellow; bottle green; coral; teal; and ivory. A madder red border with sky blue guard borders frames the field.

This piece is perhaps the world’s best small format “Vase” design Bidjar from the “Revival” period, being very fine with excellent drawing and superb color quality. From our Archives.

2 of 5

4’4” x 8’5” Antique Bidjar Rug, Northwest Persia, Kurdistan Province, Circa 1880

This distinctive and beautifully colored antique Bidjar rug from northwest Persia’s Kurdistan province features polychromatic diagonal bands of color containing stylized diamonds and squares. The red major border is decorated with scrolling leaves and flowerheads in an early style, suggesting the rug dates to no later than circa 1880.

Kurdish weavers are famous for their bold and adventurous use of color and the range of colors in this rug is remarkable, including green, yellow, ivory, mahogany, brownish-aubergine, coral, red, brown and sky blue. While it is occasionally seen in antique Bidjar rugs, the diagonal stripe field design is uncommon and is a beautiful example of textile folk art. From our Archives.

3 of 5

7’8”

Antique Garrus Bidjar Carpet, Calyx Design, Northwest Persia, Kurdistan Province, Circa 1890

“Garrus” is a term sometimes used for early Bidjar carpets from northwest Persia’s Kurdistan province. The most famous design associated with this term is the Split Arabesque design but the design seen here, referred to as a Calyx design, also fits into the broader group of carpets, assuming it is an early enough (generally 19th century) example.

The red field is decorated with large Calyx motifs in shades of yellow/camel and sky blue. Smaller Calyx motifs alternate with the larger ones. The navy blue major border is of unusual composition, with flowerheads and leaves that almost have a Cloudband feel.

19th century Bidjar carpets tend to be long and narrow, after the classical paradigm where carpets were often about twice as long as they were wide. Unlike a Fereghan Sarouk carpet of this age, that might typically be about 9 feet by 12 feet, or a Heriz Serapi carpet of this era that might typically be about 10 feet wide by 12 feet in length, this Bidjar is less than 8 feet wide by 12 feet in length. From our Archives.

4 of 5

3’5” x 5’4” Antique Bidjar Rug, Northwest Persia, Kurdistan Province, Circa 1915

Rugs from the Bidjar area in northwest Persia’s Kurdistan province with this type of articulation of the design, with a somewhat geometric medallion and corner spandrels with a lot of open space in the format, are often attributed to the village of Gogargin.

One more typically sees Gogargin type Bidjar rugs in either the approximately 2’6" x 4' size or in the approximately 5' x 7' size, referred to a s a “Dozar” size. This intermediate size, referred to as a “Zaronim”, is less common.

With high quality wool and saturated natural dyes, this piece would be an excellent choice for a beginning (or advanced) collector or for furnishing where a moderately priced, durable rug is warranted. Currently available for purchase.

5 of 5

5’10” x 8’5” Antique Halvai Bidjar Rug, Northwest Persia, Kurdistan Province, Circa 1890

A fine antique Bidjar rug of very uncommon size. The navy blue field is decorated with a red and ivory medallion and stylized floral motifs in a geometric style that suggests the rug is on the early side. Ivory corner spandrels and a brick red “Turtle” design border frame the field. The plain, variegated mid blue band between the field and the borders is a beautiful feature.

From our Archives.

6 of 6

5’11” x 7’8” Antique Bidjar Rug, Northwest Persia, Kurdistan Province, Circa 1890

The “Harshang” design of various palmettes, flowers and leaves is perhaps the most beautiful format seen in Bidjar weavings. In this piece, which is also of very uncommon large, squarish size for a “scatter rug”, the important Deerhead Border is also seen.

A soft red medallion with the classical “Herati” design decorates the navy blue field, which is also decorated with the “Harshang” design. The lack of corner spandrels, where the field extends all the way to the interior guard border on all four sides, is uncommon and gives the rug a distinctive appearance. The terra cotta color border is decorated with stylized deer head motifs and scrolling vines with leaves and palmettes. This rug is large enough to serve as a room size carpet in a small room and would be beautiful in a foyer. A very collectable rug with strong decorative appeal.

Currently available for purchase.

EUROPEAN DECORATIVE

ARTS COMPANY

www.eurodecart.com

eurodecart@gmail.com

Gallery: 516-621-8300

Mobile: 516-643-1538

299 Main Street

Port Washington, NY 11050

At the Winter Show 2025, the Wadsworth Atheneum Art Museum in Hartford, Connecticut (founded 1842), the oldest continuously operating public art museum in the U.S., acquired a recently discovered enamel and & gilt-bronze coupe, attributed to the Sèvres porcelain manufactory in France. The coupe (Figs. 1, 2 & 3) appeared in a small Florida auction last year, described generically as a “Limoges enamel tazza”. While the description was accurate, to the degree that the technique employed in its manufacture was a style of enamel used in France in the 16th and 17th centuries, the superlative

Continue on page 12

and complex execution of the enameling, high quality mounts and unusual form, indicated that it was an object to be further analyzed and researched.

Enamels made at the Sèvres factory are extremely rare, as the enamel workshop was only in existence from 1845-1872. Nevertheless, the factory is credited with “rediscovering” the art of painted enamels, which had fallen into relative obscurity since the 17th century and there was a concerted effort to unlock the secretive techniques used centuries ago.

Exhaustive research into the archives and inventories of the manufactory revealed that this coupe was most likely one of the earliest examples produced and is the only one which has been identified as having been exhibited at the Palais du Louvre in 1846. While not illustrated in the catalog – indeed no objects were illustrated at this date – a description of the tazza matches perfectly with the object, including the exact dimensions and iconography of the scenes depicted in the enamel work. Additionally, it was probably also acquired by the Comte de Paris, Prince of Orléans (1838-94), the grandson of King Louis Philippe.

The enamel scenes, depicting the liberal arts in the center, and the frolicking putti on the underside, are attributed to Jacob Meyer-Heine (1805-1879), whose works can be found in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York). We are very grateful to Erika Speel, the renowned enamel historian, for her very valuable advice and analysis of this beautiful object and for helping us bring it out of obscurity.

Words by Scott Defrin

June 4 – August 31, 2025

MAISON GERARD

www.maisongerard.com home@maisongerard.com

T. 212.674.7611

F. 212.475.6314

53 East 10th Street

New York, NY 10003

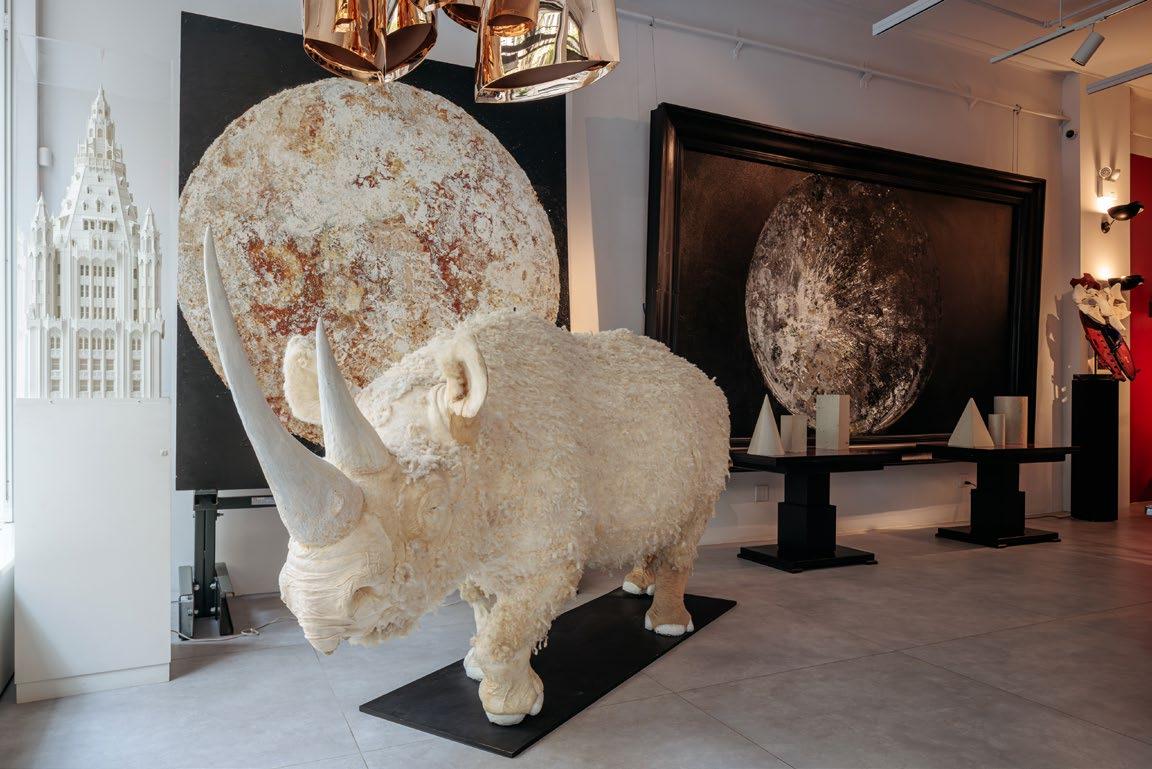

Thierry W. Despont was a man who lived in many worlds at once. Architect, designer, painter, sculptor and collector, he was, in every sense, a modern Renaissance man. To step into the exhibition at Maison Gerard—now extended through the fall—is to enter this multiverse: a place where history, imagination, and monumentality coexist in extraordinary harmony.

Since its debut this summer, the show has been praised for both its breadth and intimacy, offering the rare chance to experience Despont’s personal creative spaces brought to life. Maison Gerard will allow this world to linger a little longer, keeping alive a vision that remains scholarly yet theatrical, rooted in history with an eye toward the unknown.

Continue on page 17

Despont (1948–2023) was a longtime client of the gallery, and Maison Gerard is honored to be a part of his legacy. Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and holding a degree in Urban Design from Harvard, he is perhaps best remembered for landmark restorations and architectural projects—the Statue of Liberty, the Ritz in Paris, Claridge’s in London, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Woolworth Building among them. Yet beyond these public achievements, he cultivated a remarkable private world of art, objects, curiosities, and his own artworks—many of which form the core of this show.

Curated by Benoist F. Drut, in collaboration with Despont’s daughters, Catherine and Louise, Modern Renaissance Man reconstructs key environments from Despont’s life—his Tribeca office, his Manhattan home, and his Hamptons studio. Visitors encounter a twelve foot long Jean-Michel Frank–style sofa with amber-hued armchairs. More than a piece of

furniture, the table embodies his design philosophy: rooted in European precedent, reimagined through proportion, and adapted to American life. Here, a life-size resin and shearling rhinoceros; there, celestial canvases, insect assemblages made from vintage tools, and shelves overflowing with manuscripts, maps, and models. Following Despont’s own practice, the objects are not simply staged as decorative items; they are presented as inhabitants of his imagined worlds.

Of note is the Bibliotheca Selenica, a monumental cabinet of curiosities more than twelve feet wide and nine feet tall. Housing over two hundred volumes—including a rare second edition of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius—alongside scientific manuscripts, celestial maps, and artifacts, it is both scholarly and poetic, arguably one of the most comprehensive collections of scientific material on the moon ever assembled.

Another highlight of the exhibition is a French carom table that doubles as a dining table. Despont designed it and had it executed by Blatt Billiards, one of New York’s oldest game table makers. He chose the French pocketless carom style over the American pocket standard for its elegance and scale - not to mention he enjoyed such tables as a student in Paris. For his New York home, he added wooden cover plates for dining use. Like much of his work, the piece plays multiple roles— it’s a stage for conviviality and spectacle.

Capping the show is a presentation of the Houses books, five massive tomes that Despont created as gifts, as well as Insectissimus and Hippocampus: An Incomplete Atlas, An Architect’s Memoir. Says Benoist F. Drut, “Despont, despite being famous; was intensely private. These books were Despont’s collages of his artwork, architecture, photography and drawings into large volumes. Each book is a special glimpse into the man, and each leads to new discoveries. These were never offered for sale, and were only presented by Despont to friends and associates. Very few ever made it to the market, and single books can be found online for $1000; we are happy to be able to present full sets at much more attainable price levels.”

Maison Gerard’s decision to extend the exhibition reflects not only the strong response it has received but also the richness of Despont’s vision. For longtime admirers and new audiences alike, the show reveals the theatrical grandeur, obsessive curiosity, and timeless artistry of a man who treated design as a portal into other worlds. The gallery invites visitors to engage with a body of work that spans architecture, painting, sculpture, collecting, and above all, imagination. MAISON GERARD www.maisongerard.com home@maisongerard.com

Presented by Keith Twitchell

KEITH TWITCHELL

Executive

Director

of the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild www.keithtwitchell.com keithgct@gmail.com

1 – Greece, Athens “owl” silver tetradrachm, 5th century BCE; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

Most people see coins as little more than a means of commerce – if they see them at all. Coin collectors, however, view these little bits of metal very differently: as works of art, artifacts of history, and tellers of epic tales.

Coins first emerged in Lydia, an ancient Greek city-state located in modern-day Turkey, in the 7th century BCE. They were made of electrum, a gold-silver alloy, and were basically small lumps of metal with a rough image hammered onto them. Since then, coins have spread to every nation on every continent, serving as the primary medium of commerce for over two millennia.

Coin collecting emerged as a significant hobby during Renaissance times. The wealthy nobility valued the artistic qualities of Greek and Roman coins – and sometimes used them to claim family heritage back to the ancient world. Scholars used them to study ancient history. Among the early collectors were Lorenzo de Medici, Pope Paul II and Emperor Maximillian I.

While collectors today have any number of specialized interests–after all, billions of coins have been minted over the centuries–ancient coins remain popular. Within this area, there are many sub-specialties, such as themes (i.e., dolphins on coins), or issues from specific city-states or Roman emperors. Some collect by denomination, such as Greek silver drachms or Roman bronze sestertii (or for those with larger budgets, gold aurei).

Continue on page 23

2 – Greece, Taras, Calabria silver didrachm, circa 300 BCE; courtesy Ancient Coin Search

3 – Greece, Pantikapaion, Cimmerian Bosporos bronze, 4th century BCE

4 – Greece, Syracuse, Sicily silver tetradrachm, 5th century BCE; courtesy Peter Tompa/Ed Waddell

Coinage from ancient Greece is still considered some of the most artistic ever produced. The Greeks often used the reverses of their coins to highlight an aspect of their city; for example, the people of Thessaly were known for horsemanship, so horses appear frequently on coins of this region. Athenian “owl” tetradrachms became almost an international currency, instantly recognizable from their design and establishing Athens as a leading world power [image #1]. In Calabria, coins of Taras almost always showed a boy riding a dolphin, referencing the city’s origin myth [image #2].

The obverses usually portrayed a god of the Greek pantheon, often one associated with the city. Unsurprisingly, the obverse of the Athenian owls featured Athena, while Pantikapaion, coinage depicted the god Pan [image #3]. Sometimes a local deity might appear, such as Arethusa on the magnificent coins of Syracuse [image #4]. Not until the time of Alexander the Great, in the 4th century BCE, did the practice of placing the image of a ruler on coins begin to emerge [image #5].

When the Roman Republic began to supplant the Greek states, coin imagery generally followed the same approaches. But as the Republic gave way to the Roman Empire, things changed dramatically. Coins became propaganda tools for the emperor, with his head on the obverse and what we might today call a marketing message on the reverse.

Examples of this include coins issued to commemorate (and brag about) significant military victories, as did emperor Septimius Severus after his triumph in Arabia [image #6]. An emperor assuming the throne in turbulent times, as Domitian did in 81 CE, might issue a reverse showing Pax, the goddess of peace [image #7]. Keeping the military happy was always a priority, so some coins glorified Roman soldiers.

These coins enhance our understanding of ancient times. For example, we can confirm the travels of the emperor Hadrian from the coins he issued commemorating his visits to places such as England and Alexandria [image #8].

Continue on page 24

5 – Greece, Kingdom of Thrace silver tetradrachm, 297 – 282 BCE, depicting Alexander the Great; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

6 – Rome, Septimius Severus, silver denarius, 194 CE; courtesy Ancient Coin Search

7 – Rome, Domitian, bronze sestertius, 81 CE; courtesy Ancient Coin Search

As the Roman Empire began to decline, eventually morphing into the Byzantine Empire, coin artistry and subject variety also declined. Portraits of the emperors are less distinct and of lower quality. Christianity became the official religion, and obverses frequently depicted Jesus [image #9].

In the eastern world, the earliest coins emerged in China in approximately the 5th century BCE. Formed at first in the shapes of spades or knives [image #10], round coins, usually with a square hole in the center, began appearing about a century later [image #11]. Unlike the hammered coins of the west, early Chinese coins were cast, and made from base metals such as bronze, copper and brass. China produced immense quantities of such coins until the end of the Empire in 1912, which along with local copies were used to monetize much of East Asia. Some such coins are even found in “Chinatowns” in the Western United States.

Between the far east and the west, many other civilizations also issued coins. Ancient Indian coinage began several centuries BCE [image #12]. Islamic coinage is popular with collectors, with the earliest issues dating to approximately 700 CE [image #13]. Coins of the Mongol empire – especially from the reign of Genghis Khan – are also highly prized [image #14]. Between the hundreds of local kings, chieftains, satraps and other rulers, the collecting (and learning) opportunities are virtually endless.

In the western world, coinage continued throughout the Dark Ages, primarily hammered silver pieces. While fascinating from a historical standpoint – who wouldn’t be interested in a relic from epic figures such as Charlemagne [image #15] or William the Conqueror? – the aesthetics leave much to be desired. Many coins featured crude portraits of the ruler on the obverse, and, reflecting the dominance of Christianity, a cross on the reverse.

The Renaissance saw the return of true artistry to coinage. Magnificent coins and medals from France, Italian states such Continue on page 25

8 – Rome, Hadrian, billon tetradrachm, 130/131 CE, depicting Hadrian greeting personified Alexandria; courtesy Ancient Coin Search

9 – Byzantine, Justinian II gold solidus, 685 – 695 CE, obverse depicting Jesus; courtesy Ancient Coin Search

10 – China, spade money, circa 350 – 250 BCE; courtesy Ancient Coin Search

as Genoa and Venice, German and Spanish principalities, reflect both the royal power and artistic prowess of these times [image #16].

As the European powers began colonizing across oceans and continents, often driven by lust for precious metals, they began creating mints, and issuing coins, all over the world. By the time nations began throwing off the colonial yokes, the use of coins and currency was thoroughly entrenched from Argentina to Zanzibar. Today, virtually every nation on earth issues its own coinage (though some employ foreign mints to manufacture the coins).

Coinage in the United States reflects much of this history. Early settlers brought coins of their home countries for local use. Beginning with Massachusetts in 1652, some colonies began releasing their own issues. Some followed the ancient Greek tradition of highlighting local features, such as the “Green Mountain” coins of Vermont [image #17].

Following the Declaration of Independence, pre-federal coinage often included Roman-like propaganda elements, like the thirteen-link chain and “Mind Your Business” slogan of the so-called Fugio cents [image #18].

American coins have rarely reached true artistic heights, in part due to stipulations made by Congress regarding the images they could depict. Until the early 20th century, Lady Liberty and the American eagle were the primary elements used. A few are considered genuine works of art, such as the St. Gaudens double eagle ($20 gold piece) [image #19] and the Walking Liberty half dollar [image #20] – both the result of President Theodore Roosevelt’s desire to upgrade the design quality of our nation’s coinage.

However, this trend was quickly reversed as Congress passed new laws authorizing American historical figures to be portrayed on coins, starting with the Lincoln cent. Today, all circulating U.S. coins depict past presidents; none are

Continue on page 28

11

14

15

13

16

17 – Vermont copper penny, 1786; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

18 – United States, “Fugio” copper cent, 1787; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

17 – United States, 1908 “St. Gaudens” gold double eagle ($20); courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

20 – United States, 1937 “Walking Liberty” silver half dollar; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

21 – United States, 1926 Oregon Trail commemorative silver dollar; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

22 – United States, 1915 Pan Pacific commemorative gold fifty dollars; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

23 – Greece, Kingdom of Thrace silver tetradrachm, 297 – 282 BCE, depicting Alexander the Great; courtesy Classical Numismatic Group

24 – China, 1999 silver ten yuan, colorized

particularly distinguished compared to examples from around the world, although the recent series of special-reverse quarters has elevated that particular denomination.

A different category of coins allows for greater artistic variety: commemoratives. The U.S. and many other nations issue commemoratives; among American examples, the Oregon Trail silver dollar [image #21] and the Pan-Pacific octagonal gold $50 [image #22] piece are highlights.

Similar to commemoratives, some countries create collectoronly coins as a way to raise revenue. The island nation of Palau a prime example, having issued dozens of exotic designs never intended for circulation or even to commemorate a particular event. The country does not even mint these coins, but sells them worldwide at a useful profit.

The Cook Islands have been a leader in using new minting technologies, such as including tiny bits of a non-coin substance within a coin. One such series highlighted meteorite falls, complete with specks of the meteorite encased in the coins [image #23].

Colorizing coins is now a popular approach, as displayed by these examples from China [image #24] and Palau [image #25]. More recently, some coins have even included holograms; Canada has been a leader in this, as evidenced by this $20 coin [image #26].

Each of these innovations helps grow the number of coin collectors worldwide. The hobby is accessible to people from all walks of life, though since Renaissance times it has also appealed to the rich and famous. Well-known collectors include President John Quincy Adams, Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and actor Buddy Ebsen, who co-founded the Beverly Hills Coin Club.

Collecting today is going strong, despite some headwinds. The appearance of paper money, first achieving widespread

Continue on page 29

use in the late 17th century, initiated the first decline of coin usage. The current trend towards cashless societies has further reduced coin mintage. Inflation is also taking its toll, as evidenced by the United States announcing that it would stop producing cents, a step already taken by Canada and other countries. Ill-advised import restrictions in the U.S. are reducing access to coins from a growing number of nations despite the best efforts of advocacy groups like the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild and trade associations like the International Association of Professional Numismatists.

Nevertheless, the appeal of coins remains powerful. So many are indeed true works of art; many are also genuine historic objects – yet they can be held in the hand, lingered over at length with an appreciative eye. They continue to inform research into times from ancient to colonial. Coins are teachers: the study of Roman coins develops some understanding of Latin, the study of South American coins requires some reading of Spanish.

Coins connect people to past times and exotic places, as well as to fellow collectors all over the world. They create community, curiosity, and little sparks of happiness with every numismatic encounter.

Words by Keith Twitchell

KEITH TWITCHELL Executive Director of the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild

www.keithtwitchell.com keithgct@gmail.com

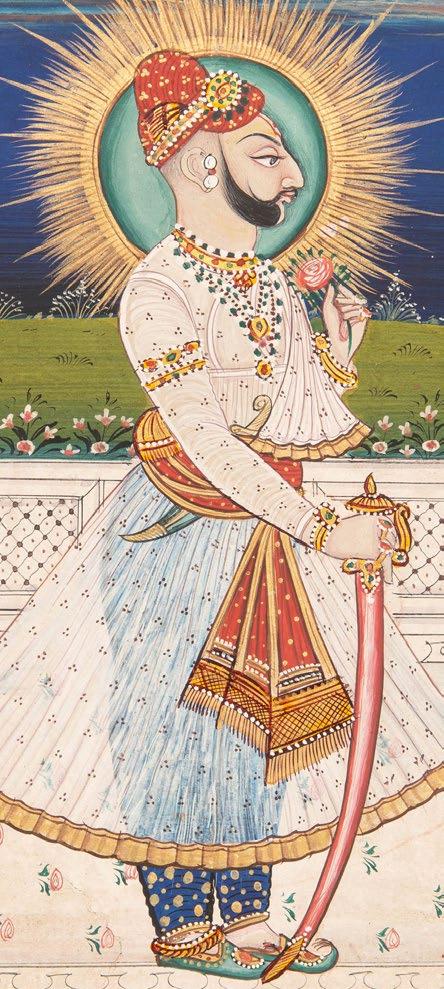

Portrait of Maharao Ram Singh Bundi, Rajasthan, India, 19th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 10 1/4 x 7 1/4 in. (26 x 18.5 cm.)

Folio: 12 x 9 in. (30.5 x 23 cm.)

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

Kapoor Galleries presents The Blossom & the Sword, a fall 2025 exhibition showcasing portraits from across the Indian subcontinent. These works depict individuals from all walks of life including noblemen and women, high-court officials, courtesans, and villagers. The paintings of nobility reveal how the courts of India aimed to convey a sense of refined elegance and an authoritative presence to their subjects, while the depictions of others offer glimpses into everyday life and society. Every element—from the details of the garments and colors used, to the posture, gaze, and objects in hand—give insight into the individual, their social status, the culture of the time period, and the society in which they lived. Explore a collection of portraits from India in The Blossom & the Sword at Kapoor Galleries or online at kapoors.com/exhibitions.

KAPOOR GALLERIES www.kapoors.com 34 East 67th St, New York, NY By appointment only info@kapoors.com +1 (212) 888-2257

"The

motif of the ruler holding a blossom and a sword may be understood as emblematic of sensitive and martial qualities—representing a king who can appreciate the delicate and ephemeral fragrance of a flower but will fearlessly face his enemies when provoked."

Portrait of Maharao Ram Singh

Bundi, Rajasthan, India, 19th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 10 1/4 x 7 1/4 in. (26 x 18.5 cm.)

Folio: 12 x 9 in. (30.5 x 23 cm.)

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

A Nayika Writing a Note

Kangra, India, circa 1810-1830

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 ¼ x 6 in. (21 x 15.2 cm.)

Folio: 9 ¾ x 7 ¾ in. (24.8 x 19.7 cm.)

Published: Sharma, Vijay. Painting Traditions of Kangra. p. 95.

Provenance: The Collection of Hellen and Joe Darion, New York, by February 1968.

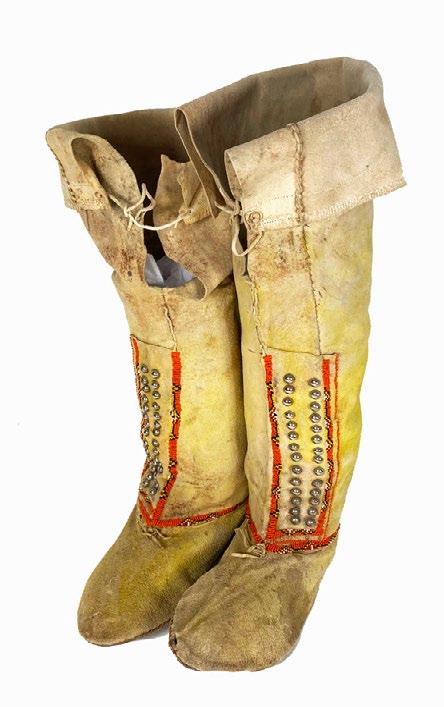

MARCY BURNS AMERICAN

INDIAN ARTS LLC

info@marcyburns.com

212-439-9257

917-710-8635 (cell)

www.marcyburns.com

520 East 72nd Street, 2C

New York, New York

1 of 14

Hopi pottery canteen attributed to Nampeyo

2 of 14 (on right)

Navajo eyedazzler blanket woven out of Germantown wools

Marcy Burns Schillay was born and raised in Denver as a member of a fourth-generation Colorado family (her greatgrandparents were dairy farmers in the 1880s near Pueblo, Colorado). She graduated magna cum laude from Tufts University where she majored in political science, with minors in History and Education. After Tufts, Marcy attended Teacher’s College at Columbia University in NYC, where she received a Master of Arts degree. She comments that she “almost took a course with Margaret Mead but it met very early Saturday morning. I regret that I didn’t take that course to this day."

Marcy married and moved to Pennsylvania. Her husband began working as a lawyer in a prominent Philadelphia law form and Marcy began teaching World Cultures and Humanities at Abington (PA) High School. After her children were in school, Marcy ran a very successful elective elementary program in Cheltenham, PA for seven years, which offered a wide range of courses in the arts. She has always been an educator, whether in the schools or as a dealer working with new collectors.

When asked about her interest in Native peoples, Marcy reflects that her interest “goes way back. My parents took us on many car trips throughout the West when I was growing up. I certainly saw Indians on these trips. On one trip, we went to the Gallup Intertribal Ceremonial and that had a big impact. In addition, she recalls an essay on Anasazi culture that she researched and wrote as part of a competition while she was in ninth grade. That triggered her interest in the history and culture of the Anasazi, Hopi and Pueblo peoples.

One more memory: "After getting married in Denver, my husband and I went to Arizona on our honeymoon. We came upon a trading post on the Pima Reservation where we fell in

love with an early Pima basket. We couldn’t afford the basketit cost $60. - but our interest in baskets was triggered and they became my first collecting love".

Marcy began to seek out baskets. She and her husband purchased their first baskets at Kohlberg’s and at Peter Natan’s gallery in Denver soon after. Wherever they were, they searched out antique Western Indian material, including in Maine when they visited her husband’s family. Their collection began to grow.

Marcy learned that Pennsylvania was a center of wealth from the 19th century until the Depression (think steel, coal and railroads). Many well-to-do Pennsylvanians traveled west on the railroads and they usually came home with objects they had purchased on their trips. “They had the time, the interest and the means to go. They valued the beauty of the objects as well as their history and they cared for them, passing them down through the generations".

In 1983, Marcy and her husband took their children on a trip to Santa Fe. Coincidentally, they arrived on the last day of the Whitehawk Show and that is how she discovered the antique collecting world. Upon returning to Pennsylvania and with her youngest child entering kindergarten, Marcy became a dealer, initially selling contemporary pottery, which she sold to interior designers, and also contemporary Indian jewelry, both of which she sold at shows.

Marcy’s focus and primary interest, however, was always on the antique market. When she discovered that antique Native American material was available and being sold at antique shows near her home, she began buying objects to sell. By 1984, she was participating in Americana shows. She believes that she was probably the first person to exclusively offer antique Native American material in major American antiques shows.

Continue on page 36

5 of 14

knifewing god pin

“Pennsylvania was a treasure trove. I would meet people in local antique shows and go to their homes and buy. As a result, I was able to offer wonderful fresh material. I was in the right place at the right time with the right material.”

Marcy always cared a lot about relationhips with buyers and sellers and she has always tried hard to be fair. She says, “The word spread and I still get those phone calls”. When the first pieces sold, Marcy bought more. “I always had baskets; they were and remain my first love. Then I discovered Historic pottery and Navajo (Dine’) textiles. My business and interests grew.”

Marcy became aware of the pending Spiderwoman exhibit at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (now called The Penn Museum). “We donated money towards the exhibit and related symposium and we were invited to a reception at [Philadelphia collector] Fred Boschan’s house". That is how she met Fred and the staff of the museum and that was the beginning of a close connection with both that continues to this day. She calls Fred Boschan her role model and good friend.

Marcy became a volunteer in the Museum’s American (Indian) Section which led to 15 years of working with one of the largest and premier collections in the world. The Penn Museum has approximately 300,000 objects, 40,000 of which are ethnographic rather than archaeological. She says, "I was able to see and handle high quality early material. I learned from the material itself. I also met academicians and I still have to connections to many of those people today.”

Among other clients, Marcy sold to Fred Boschan. “I would get things and he would come running over. He told people to ‘pay attention to this dealer’” As she made money, she put it back into the business, expanding the inventory, participating in shows and advertising. "Public exposure helps and if you are fair, that comes back to you.”

Continue on page 38

8 of 14

Among the items that Marcy was “fortunate to acquire” was a very early Navajo Classic serape and a Lakota ledger book. She says that the serape is still “the finest and most beautiful that she has ever seen”. (It remains in private hands). The ledger book was an account of the Sun Dance and it is a very important document as well as beautiful art. She felt a “moral obligation to keep it together and make it available to scholars.” She is pleased that after she sold it, it was kept intact and is now at the University of California at Davis where it is available for study.

Marcy has participated in major antique shows including the Whitehawk Indian Show, the Philadelphia Antiques Show, the Delaware Antiques Show, the ADA Show and the Metro show in New York City. She also sets up a jewelry case in her husband’s booths in Palm beach and New York. (Marcy’s husband, Richard Schillay, is a fine arts dealer who exhibits Impressionist and 20th century modern art in major shows in both locations).

When she lived in Pennsylvania, Marcy lived in the suburbs of Philadelphia. She comments that now that she is in New York, on the Upper East Side just down the street from Sotheby’s, she gets more out-of-state collectors visiting the gallery (she works by appointment only). Being in New York City, she says that she sees visitors who come from all over the world as well as from the United States.

People wonder if it is difficult being an Indian dealer outside of the Santa Fe-Scottsdale axis? Marcy comments that she has never been part of a geographic network. She feels that in some ways, that helped. She didn’t rely on a network of other dealers. She was able to get fresh material and do it justice.

Marcy has sold to several museums, including an “important and fine” Chilkat blanket to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. She stands behind the materials that she sells and she is always willing to sell on a consignment basis from collectors who purchased the item from her. Of course, she fully warranties in writing all material sold.

Marcy has a private collection of never-sell pieces, including important baskets, textiles, pottery and beadwork. She is especially fond of a “great Moki blanket that came out of a Philadelphia home that has never been on the market and a great jar by Nampeyo that also descended in a family".

Marcy is a founding member and two-term President of Antique Tribal Art Dealers Association (ATADA) and also a founding member and former Board member of Antique Dealers Association of America (ADA). She is also a long-term and proud member of AADLA.

L'ANTIQUAIRE & THE CONNOISSEUR

www.lantiquaire.us info@lantiquaire.us

+1-212-517-9176

36 East 73rd Street

New York, NY 10021

King Louis XV had 10 children with only one wife. Six were born within 5 years with his Queen Maria Leszczynska, whom he married at age 12. At age 15, his first born was a twin named Elizabeth, her twin named Henriette.

Elizabeth was married off at age 12 to the youngest son of the Spanish King, Infante Philip Peter. Louis XV wanted to strengthen ties with the Spanish Royal House, who were themselves direct descendants of the French King Louis XIV.

At the Spanish court, Elizabeth had to contend with her mother-in-law and also the dullness she was not used to coming from the brilliant court of Versailles.

With the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, the independent Dutchy of Parma became available. Elizabeth made sure her father intervened to secure the Dutchy for her and her husband, which would give her more freedom as the Duchess of Parma. She had spent 10 months in Versailles again and was obliged to join her husband in Parma. He was a kindly man whose nickname was Il Tappeziere as hanging tapestries in churches was his favorite activity.

Elizabeth had 3 children and was very active promoting French culture, styles, and trying to emulate Versailles as much as possible. She brought the French furniture maker, Marc Vibert, to Parma from Paris to make her furniture. This console pictured here (Fig. 1), from the 1755-1760 era, was known to have been made for her by him. It is beautifully carved, very graceful, finely gilded with its original marble top. It looks quintessentially French and of a quality that would have been appreciated at Versailles.

Written by Clinton Howell

Digging for a definition of what can only be considered an artificial concept, taste, is like identifying the flotsam and jetsam after a Category 5 hurricane. It isn’t possible—taste is an amorphous concept that is subject to a great many variables, some cultural, some the current zeitgeist, individual preference and economic factors not to mention experience— the list goes on. The icing on the cake is, of course, fashion and trends, whether something is hot or ignored. Good and bad taste morph in definition according to all these variables—is there a solid base to any of it?

I will try to answer that question but my intention is less to provide a definition and more to provoke thought about why you like something, because every person, from the age of seven onwards, has a sense of taste. But the understanding of your motivation for liking something can evolve your taste. Furthermore, nothing stays the same if you are the type of person who digs and tries to understand why you might like something. New things are constant and you can, potentially, find your taste taking a whole new direction, maybe not disowning what went before, but altering your outlook. And this is true for just about anything in your life—clothes, the space you live in, architecture, food and much more.

Consider the world of cars. Car design was either functional or very sleek when cars first hit the mass market. When World War II came to pass, functionality became the norm—car companies were concerned about looking frivolous, I suppose. Jump into the 1950’s and American car manufacturers enter into a world of their own, opting for powerful engines

1958 Edsel Pacer 4dr sedan, taken Sept 2003. Image Credits: Loungelistener at English Wikipedia

and sizable dimensions and, of course, a lot of chrome—big powerful cars. They had their day and by the mid to late 1960’s, car design faltered into what I might refer to as a middle aesthetic. But, interestingly, the cars from the 1950’s are collected because they stand apart in such a striking fashion—but are they tasteful?

The question begs asking because many of those cars get negative reactions for their material obsolescence—someone who has driven Volvos or Jaguars all their life might be quite disdainful of them. (And vice-versa.) But should that affect our view of them if they are in fact, to our taste? This is the crux of the matter—we are all allowed to like what we like—we are even encouraged to like what we like. There is a disconnect here that is quite diffcult to assess in a positive or negative fashion simply because we all see the world differently.

I often think of the great scene from “My Cousin Vinnie” where Marisa Tomei is able to describe a car from a tire track. Her character knows everything she needs to know to determine the make and model—she truly knows her subject. Learning about taste is not that different. You need to look at everything and ask yourself what it is that you like or don’t like about something, ask tough questions of yourself. Again, this approach needs to be used on everything—it’s about being judgmental in order to learn what it is you like. If you think the Edsel, going back to the 1950’s car paradigm, is ugly, that is your choice, but if you express such an opinion, you should be ready to back it up.

Architecture is much easier to talk about than cars because everyone has an opinion about buildings. If you live in New York City, as I do, there is a lot to talk about although I will keep it simple and talk about just a few buildings. My biggest pet peeve is brutalism—not because I don’t like it, but because for it to fit into a city, you have to locate it in the perfect spot. Indeed, my most favorite walk in the city is under the enormous concrete arches you see on Randall’s Island, built

The Sydney Opera House: The monument that represents Australia Image Credit: Bella Falk-Alamy

“Sargent and Paris” exhibition at MET Image Credit: metmuseum.org

to hold the trains serving Penn Station. They are gorgeous in my opinion. And one of my favorite buildings that fits the definition of brutalism as I know it, is the Sydney Opera House. It is nigh on perfect in my eyes.

You would think that I like brutalism and even consider it tasteful in the right situation. That is absolutely true. Where doesn’t brutalism work? How about the former Whitney Museum home on Madison Avenue between 74th and 75th streets? In my eyes, it’s a really stupid place for a brutalist structure. Of course, there are others who will disagree with me and suggest that it makes a great contrast to all the limestone and brick that predominates in the area. I will dispute their taste, but I can’t deny their taste, although, if the person disagreeing with me was an architect, I would never use them to build for me.

Location makes an enormous difference to what we might consider to be tasteful. I ran across a video from the Metropolitan Museum regarding the Sargent exhibition at the Met, “Sargent and Paris”. The video was discussing a painting of a woman in Morocco dressed in white with a white umbrella against a white wall. I have seen it a number of times and I love the painting, much more than “Madame X”, which is among Sargent’s most infamous paintings. The video explains what I already knew, that painting white on white is really very diffcult. My question, however, relates to the discussion of taste—is the painting in good taste? Is the painting even subject to the question of whether it is in good taste?

Figuring out the tastefulness of this painting is questioning an icon. It’s a rude question but it needs to be asked about everything that you like. In a way, the painting is exceedingly demure and for that, at least on the surface, it lacks visual power. Does a painting need visual power? The question suggests that I am judging the painting incorrectly—it isn’t about overt power, it is about a subtle power—the power of a supra accomplished painter working with the absence of color. Yes, in my opinion, it is very tasteful, but it will require its own space. It can’t be placed next to, for example, a

Continue on page 47

Rembrandt, a van Gogh, a Turner or a host of great artists. This painting is quiet and appreciation is achieved by close attention.

I’m hinting here, that upon a full assessment of an object, that the object, in a way, defines how it is meant to be used. Years ago, I was invited to visit a friend on the banks of the Hudson close to the Rip Van Winkle Bridge, near Hudson, NY. My host was an English furniture curator who rented this house for years and he spent his time furnishing it with items he could afford which was NY State made furniture dating between 1840-60, not a period known for its great design. Anyone who knows this era will know that the shapes are bulbous, the furniture over scaled and bulky and made with red stained mahogany veneer that shouts, look at me. However, his use of this furniture was sparse—one chest against a white wall with an appropriate mirror, chairs and art—the wall, the room worked sublimely well.

As you can see, the word function pops up along with location in the discussion of taste, because taste is not just about how good the object, material, color choice or whatever else you are looking at may be. Does that mean the Edsel sedan passes muster if it can get you where you want to go? It doesn’t.

Function, like everything else to do with taste, is provisional. A good example can be found in color preference. Blue is a wonderful color—almost any shade of it—but it is not always the right color. Silk is a wonderful material, but it isn’t always right. And so on and so forth. Favorite colors do not imply good taste. Materials don’t define taste—why is this definition so slippery?

One way of looking at the visual aspect of taste is to relate it to the feeling in our mouths that we get from the food we eat. We have lots of words that describe our sense of taste— sharp, tangy, sour, spicy, full flavored, zesty, bland, yucky, sublime, sweet and on and on—I believe one can visualize all of these adjectives. The variables are related to what we

Continue on page 48

are eating, when we are eating it and what we are combining things with, whether we are having an overall good time and who and where we are eating with. And if you’re hungry, how something tastes will matter far less than just having something to eat. There are probably many more variables that I haven’t thought of, but regardless, we will be judging what we eat and talking about taste(s) at the end of the meal.

There is no doubt that anyone who understands the layers behind everything, is also someone who begins to grasp what makes good taste. Yes, there are single objects that just sing—I have a few in my inventory of English furniture— but context really matters. Does this mean that something that many consider to be ugly or in bad taste can be made to reflect, somehow, good taste? Perhaps it does? Many things start out as being in bad taste, after all, but things that have lasted for years earn a certain cachet for having lasted so long and begin to fall under the umbrella of being, if not in good taste, iconic. Even so, the assessment of taste is a constant adjustment, quite literally day by day.

Bad taste can be defined to a limited extent. It often reveals itself. It is always insistent, dominating where you don’t necessarily want dominance, upsetting balance when you need it and generally hogging the limelight when you are looking for collaboration. You can see this in literature by how we view novels differently from generation to generation. Mark Twain is seen very differently from just fifty years ago, because some of the language he used is offensive to us today. For some, a few of his books are now considered to be in bad taste. Or take the Eiffel Tower—scorned when it was built and now an icon—for many it represents Paris.

Why does taste matter? The crux of this essay is to suggest that good taste improves an environment. Man made spaces have options, after all, and being neutral is certainly one of them. Most airports aim for good taste and are usually lucky if they are neutral. Modern hotel lobbies also work towards creating a standard from the moment you walk into the building. It’s a diffcult task and the designer, in either

Image credits: Wikipedia, Paul 012

Continue on page 49

The main waiting room of old Penn Station. George P. Hall and Son. Interior of Pennsylvania Station. 1911. Museum of the City of New York.

McKim-Mead-White, PennsylvaniaStation, New York City via the Library of Congress.

one of these cases, needs a significant budget—otherwise, neutral is the option. I’m reminded of the building of the Ford Foundation Atrium—it was a modern concept in 1967 that was highly praised as it did something most entryways don’t—it intrigued people and that interest overpowered any sense of neutrality. People loved it.

Taste matters in what we eat and it should matter on what we see. City dwellers are enshrouded in a man made environment and making that environment interesting relieves the stress of city dwelling. Making it beautiful ups the ante as it encourages interaction and lessens tension—the tension that comes from seeing something as a grind versus seeing something as a pleasure. A great example of this is New York City’s High Line, a public park created on elevated railway tracks that is planted out with local flora. We are, inadvertently, affected by the choices that create taste wherever we are—we can’t avoid it. Whether it accommodates you is something you’ll know when you start to peel back the layers on what you consider to be your taste.

There is, however, a democratic aspect to taste which should not be underestimated. No one has to like everything and when enough people veto something, it is hard to argue with the majority. Penn Station was demolished, seemingly without a thought, by the New York City Department of City Planning, and Grand Central came close to being demolished as well. And yet what many would call the mediocre building at 2 Columbus Circle built by Huntington Hartford took years to be re-designed because people wanted to retain the original design. Tastefulness doesn’t imply anything other than a momentary opinion and some things that are lost will be mourned and others simply forgotten.

What is there to learn about taste? It’s yours, no one else’s and the more you can understand why you like something and can defend it, the more likely you will be to want to surround yourself with those things that please you aesthetically. That is a good thing, something everyone should work towards. Think about how wonderful it is to have trees lining a street,

Continue on page 50

which I consider to be one of the more tasteful things that can be done in a city. Yes, they create a mess when the leaves fall and yes, they need to be looked after and there is pollen, but the benefit is to make life calmer for the shade they offer in summer let alone the carbon they capture in the growing season. The green of the leaves is always a nice break from concrete, macadam, brick or limestone, and you get to watch them grow and flower. They make everyone’s life better. They are, at least in my opinion, the quintessence of what a tasteful city street can offer.

Words by Clinton Howell

CLINTON HOWELL ANTIQUES www. clintonhowellantiques.com clintonrhowell@gmail.com (646) 489 - 0434 30 E 95th St #5B, New York, NY 10028

On September 20th, the AADLA participated in the Treasures from the Attic annual appraisal event at the Nassau County Museum of Art (NCMA). This event fosters greater public engagement with the art and antiques world—inviting attendees to bring in artworks and objects from their personal collections, meet with trusted experts, and gain valuable insight into the cultural and historical significance of the pieces they have inherited or collected.

This was the second year that this appraisal event will took place at the NCMA. Last year’s event was initiated by Scott Defrin of European Decorative Arts in collaboration with the NCMA. While it was not officially organized by the League at the time, Scott participated as a representative of AADLA, and the event was well received by the public and the museum alike.

This year on Saturday, September 20th, the AADLA was the official sponsor of the event, in direct partnership with the Nassau County Museum of Art. All proceeds benefited the museum’s exhibitions and educational programming, and the AADLA had 12 appraisers who graciously lent their time and expertise. Learn the names of each appraiser and the categories of art that they evaluated on the next page. The AADLA is grateful for the opportunity to work with the NCMA and looks forward to supporting future projects with the museum.

Would you like to participate next year? If so, reach out to marketing@aadla.com to learn more and sign up today.

Asian

Sanjay

European

Scott Defrin, Euorpean

American

Betty Krulik, Betty Krulik Fine Art Limited

Marissa Brucculeri, C.G.A., G.G., A.J.P., Long Island Jewelry

Harry S.

Richard Schillay, Schillay Fine Arts Inc.

Robert Rienzo, Galerie Rienzo

Scott

Clinton

Michael

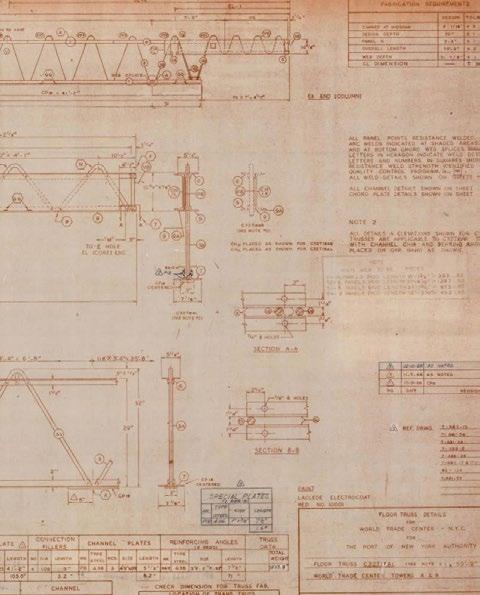

ROBERT MORRISSEY ANTIQUES

www.robertmorrissey.com robert@robertmorrissey.com (314) 560 - 5006

5 Spoede Hills Dr. St. Louis, MO 63141

Among the many joys of life as an antiques dealer is the thrill of discovery. Whether in a big city auction preview, an antiques fair in the country, a call to a local residence, or even in another shop, there’s nothing quite like discovering an object you never knew existed or never dreamed you’d find. But it happens. Over my 40+ years in the business here in St. Louis, I’ve had my share of discoveries. Like the time a Newport chair surfaced in the bedroom of a townhouse in a tony suburb. Made by Job Townsend, c. 1760, and in original untouched condition, it is now in the collection of the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee. Or the time I found a superb Biedermeier secretary at a Midwest antiques fair, later to discover its close relationship to an important drawing conserved at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna. The list goes on. A small but important early 19th century Berlin cast iron urn turned up at a rural auction in Pennsylvania a few years ago. Based on a Wedgwood model, it’s now in the Birmingham Museum of Art, home of the most important collection of European decorative cast iron in the country. While the bread and butter of my career has been in

Continue on page 56

455 Fabrication Plans for the Floor Systems of the World Trade Center

Engineered by A. C. Weber for the Laclede Steel Company

5 Blueprints Illustrating the Concept of the Floor Systems

Minoru Yamasaki & Richard Roth, architects

the handling of more traditional European furniture and objects, it’s outliers like these, and the ensuing research they demand, sometimes taking years to complete, that have sustained my interest and enthusiasm. Most gratifying, however, is the satisfaction of identifying a significant historical artifact and giving voice to the people and culture that produced it.

Little did I realize what I was getting into when I bought the fabrication plans for the floor systems of the World Trade Center in 2022. The floor systems were designed and manufactured by the Laclede Steel Company, headquartered in St. Louis, so it made sense they’d surface here. My first thought was, “These are big, beautiful graphic images and they relate to the Twin Towers- if nothing else, I can frame and sell them!” Numbering over 450, I’d have inventory for years. But as I studied them, what emerged was perhaps the most important find of my career. Unlike say, the plumbing or electrical systems, the floor systems were structural components that kept the towers standing and the people safe inside. As I peeled back layers of the onion, the dramatic, life saving role they played on 9/11 came to light. Thus, they will be offered as a single magnificent archive of one of the great architectural and engineering triumphs of the 20th century.

It is well remembered that the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, claimed the lives of over 2,500 people. Among the many questions raised on that dreadful day was, why didn’t the Twin Towers collapse on impact, instantly killing all 17,000+ occupants? How did the buildings remain standing for approximately one hour, long enough for some 15,000 people to evacuate safely? The answer lies in the remarkable design of the floor systems. The innovative floor systems, with their patented truss design, provided the extraordinary strength that played a critical role in saving the lives of so many people. The floor systems also prevented the towers, each standing over ¼ mile high, from toppling over during the collapse, a truly unimaginable scenario. Continue on page 57

This rare set of 455 fabrication plans for the Floor Systems of the World Trade Center documents the design, manufacture and assembly of this engineering marvel. Full sized working plans, measuring 24” x 36” and rendered in granular detail, they bear the stamps and annotations of the manufacturer, engineers and contractors who built the tallest buildings in the world at the time of their completion.

Bound together in 5 volumes, this is the most complete set of its type known to exist. Its historic significance is further enhanced by the fact that federal investigators used these very plans during their investigation into the towers’ collapse. Their findings indicated that, had the insulation not been knocked off the girders, the towers would likely have remained standing—thanks in large part to the floor systems.

Accompanying the set are five large-scale blueprints from lead architect Minoru Yamasaki. Measuring 36” x 50”, the largest format in use at the time, they outline the basic concepts for the framing of the Twin Towers.

Together, this historic archive, comprising 460 plans, fully illustrates the World Trade Center's extraordinary floor systems. It reveals the genius of the architects, engineers, manufacturers, and contractors that remained largely unrecognized until 9/11, when the critical role they played in the safe evacuation of thousands was brought to light. It is one of the most significant sets of World Trade Center documents ever offered.

To learn more about the fabrication plans for the floor systems of the World Trade Center, please reach out to Robert Morrissey. words by Robert N. Morrissey

AADLA MEMBERS: L'ANTIQUAIRE & THE CONNOISSEUR, INC. • KELLY KINZLE ANTIQUES • KAPOOR GALLERIES

• EUROPEAN DECORATIVE ARTS COMPANY • CLINTON

HOWELL ANTIQUES • A LA VIEILLE RUSSIE • A.J. KOLLAR FINE PAINTINGS, LLC • ANDERSON GALLERIES • ANTIQUARIUM • BETTY KRULIK FINE ART LTD. • BRAD & VANDY REH • CAMILLA DIETZ BERGERON • CARLTON HOBBS LLC • CHARLES CHERIFF GALLERIES • CHRISTOPHER BISHOP FINE ART • DALVA BROTHERS, INC. • RICHARD A. BERMAN FINE ART • DAPHNE ALAZRAKI FINE ART • DAVID NELIGAN ANTIQUES • DOUGLAS STOCK GALLERY

• EARLE D. VANDEKAR OF KNIGHTSBRIDGE, INC. • ENGSDIMITRI WORKS OF ART • FIND WEATHERLY • FRAMONT

• G. SERGEANT ANTIQUES, LLC • GALERIE RIENZO, LTD. • GEORGE GLAZER • GODEL & CO. FINE ART • HIXENBAUGH

ANCIENT ART LTD. • HYDE PARK ANTIQUES, LTD • ILIAD

• J.N. BARTFIELD GALLERIES • JAMES ROBINSON, INC. • JAYNE THOMPSON ANTIQUES • JULIUS LOWY FRAME & RESTORING CO. • YEW TREE HOUSE ANTIQUES • MAISON GERARD • MARCY BURNS AMERICAN INDIAN ART • MARY HELEN MCCOY FINE ANTIQUES • MEDUSA ANCIENT ART, LTD. • MICHAEL PASHBY ANTIQUES • O'SULLIVAN ANTIQUES • PAUL M. HERTZMANN, INC. • PHILIP COLLECK, LTD. • R. KALLER-KIMCHE INC. • REHS GALLERIES, INC • ROBERT MORRISSEY ANTIQUES • ROBERT SIMON FINE ART • ROBYN TURNER GALLERY • SCHILLAY FINE ART, INC • SPENCER MARKS, LTD. • STEPHEN RUSSELL • THE ROMAN GORONOK COMPANY • THOMAS K. LIBBY • LILLIAN NASSAU • ARNOLD LIEBERMAN FINE ARTS •

AADLA invites you to support Himalayan Art Resources: A comprehensive education and research database and virtual museum of Himalayan art. Discover a wealth of knowledge at HimalayanArt.org The Art and Antique Dealers League of America, Inc. is the oldest and principal antiques and fine arts organization in America. Learn more at AADLA.com

Interested in working with the AADLA? Reach out to us via email: info@aadla.com or marketing@aadla.com