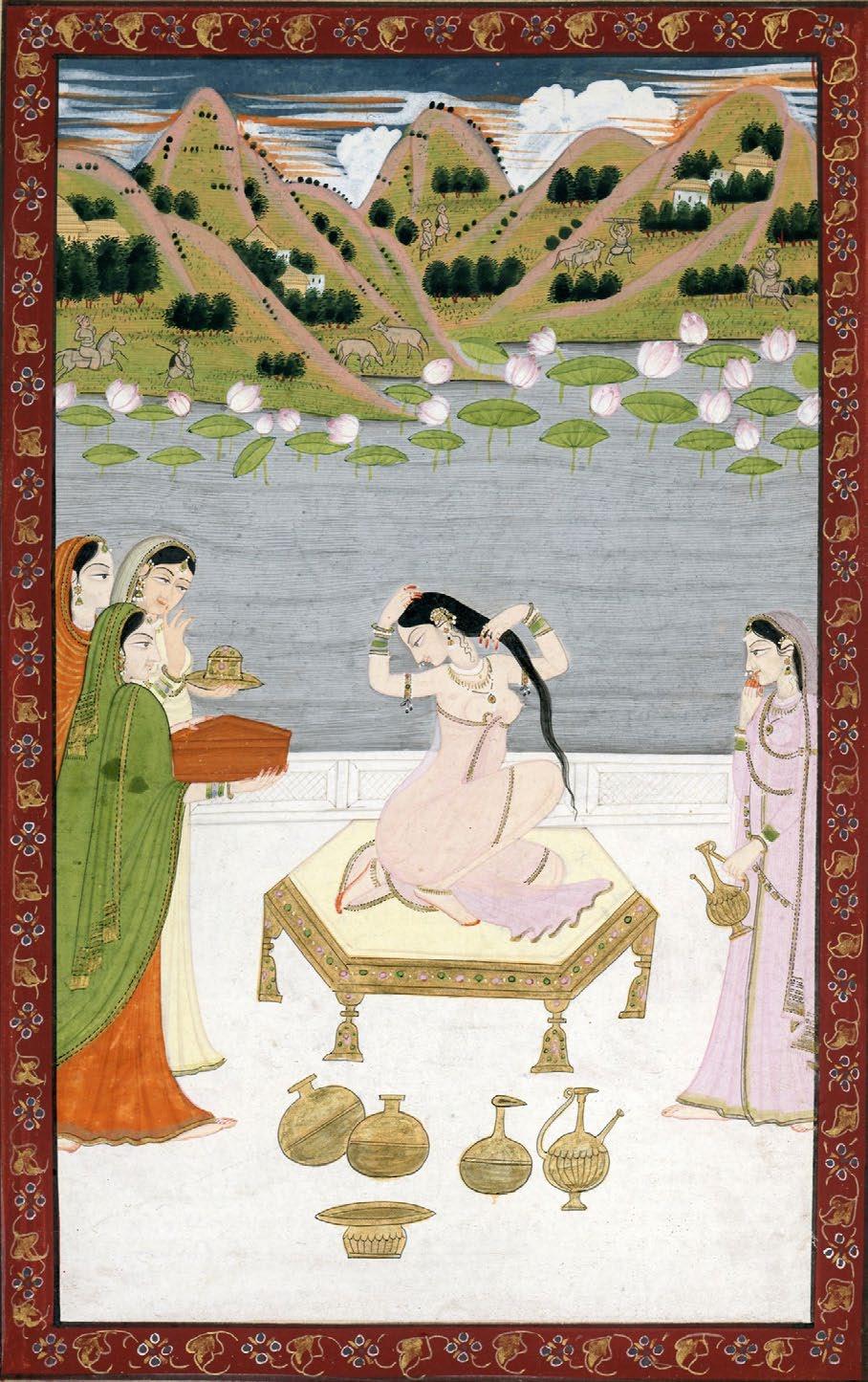

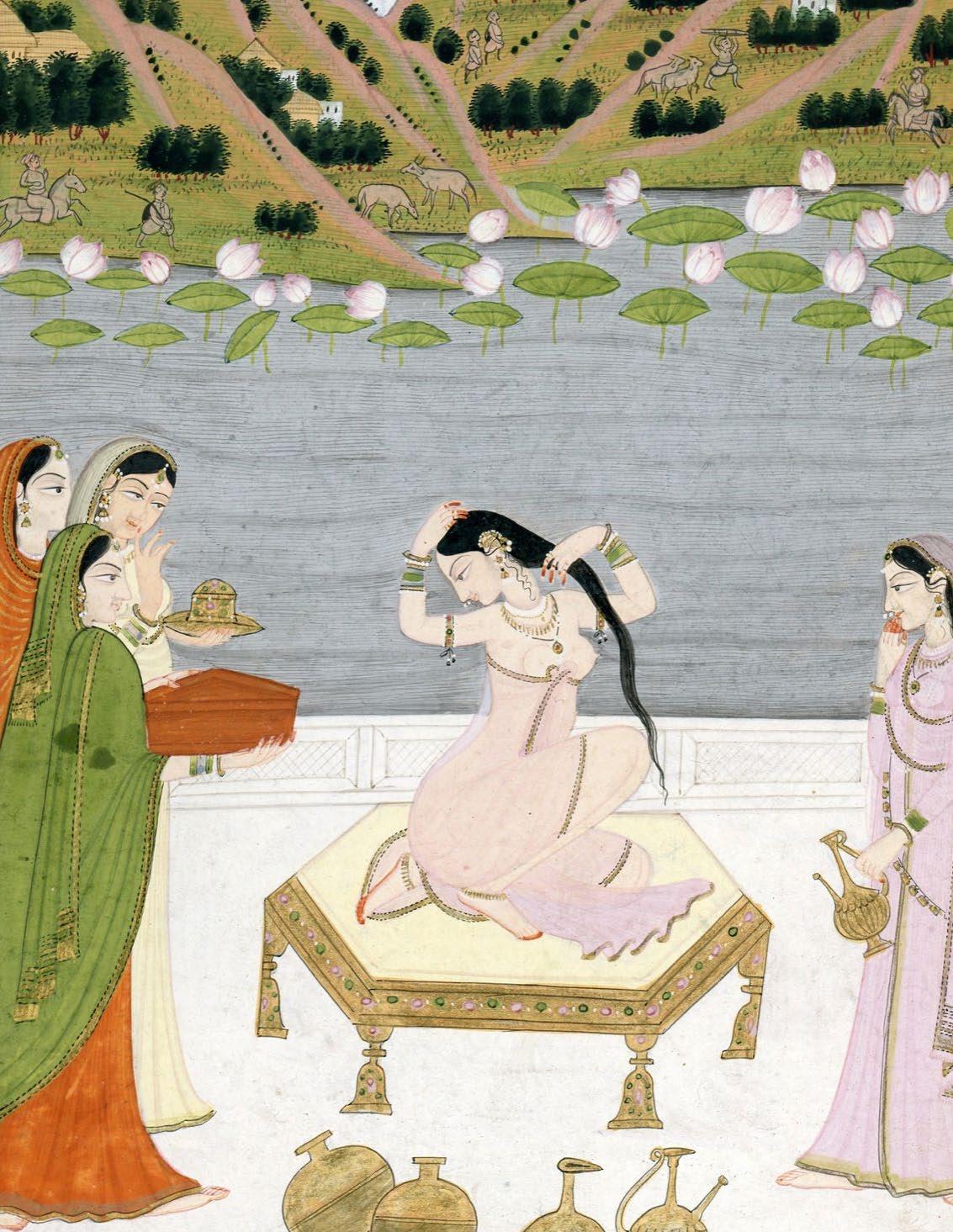

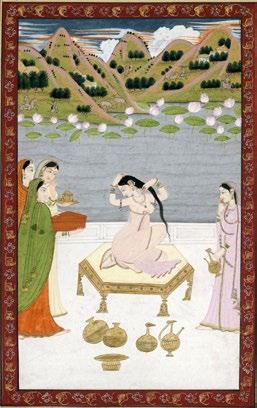

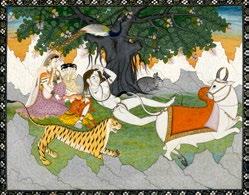

A Nayika Preparing to Meet her Beloved Kangra, India, mid-19th century Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper Image: 7 2/3 x 5 in. (19.5 x 12.7 cm.)

Folio: 10 ½ x 7 in. (26.7 x 17.8 cm.)

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 6 July 1978, lot 64. The collection of Dr. Alec Simpson.

Kangra, India, mid-19th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 2/3 x 5 in. (19.5 x 12.7 cm.)

Folio: 10 ½ x 7 in. (26.7 x 17.8 cm.)

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 6 July 1978, lot 64. The collection of Dr. Alec Simpson.

A nayika kneels on a gold and jeweled plinth, naked except for a transparent wrap and gold jewelry. Her lithe body turns as she wrings out her long black hair on the white marble terrace of the zenana. The woman is accompanied by four attentive handmaidens holding vessels that contain body oils, perfumes, ointments and lac for the palms of her hands and soles of her feet. As she prepares to greet her lover, the air is tense with anticipation. The blue, cloudy sky is streaked with red, rendering an evening sunset. In the middle distance rises a gray lotus-filled pond, the blossoms and leaves large and freshly blooming. In the far distance, a village set among steep hillsides is visible. Amidst its population of cowherds and small structures, two tiny mounted nobles gallop in from the left and right.

Compare these landscape features to a work signed by the artist Har Jaimal in W.G. Archer’s Visions of Courtly India, 1976, no. 73 and 74.

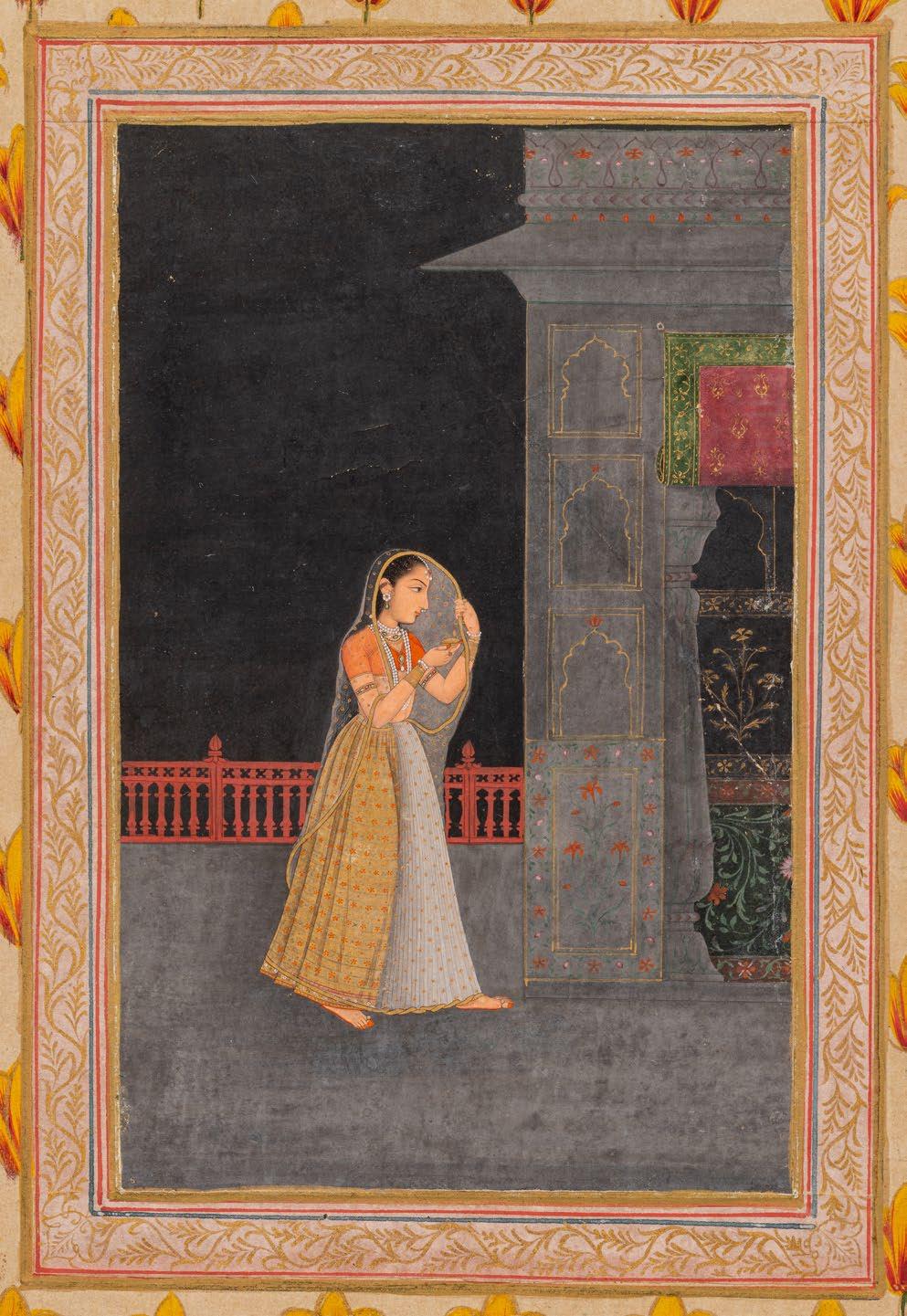

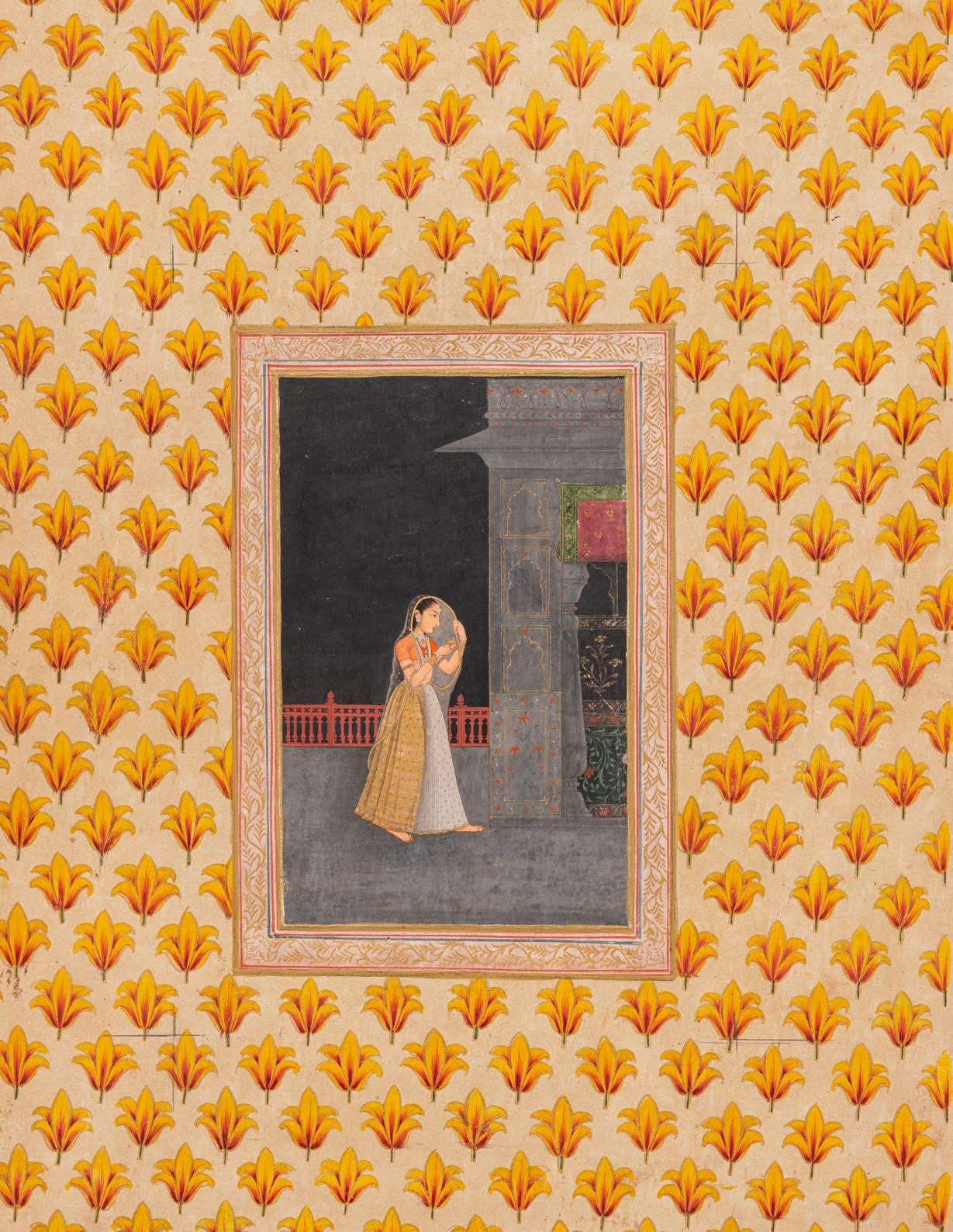

Princess Strolling Across a Palace Terrace at Night Lucknow, Awadh, India, circa 18th century Gouache painting on paper heightened with gold leaf Image: 7 1/8 x 4 7/8 in. (18.1 x 12.4 cm.)

Folio: 17 x 12 in. (43.2 x 30.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Doris Wiener Gallery, New York, September 30, 1969 (documentation available upon request).

02 Princess Strolling Across a Palace Terrace at Night

Lucknow, Awadh, India, circa 18th century

Gouache painting on paper heightened with gold leaf

Image: 7 1/8 x 4 7/8 in. (18.1 x 12.4 cm.)

Folio: 17 x 12 in. (43.2 x 30.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Doris Wiener Gallery, New York, September 30, 1969 (documentation available upon request).

This exquisite miniature painting from 18th-century Lucknow embodies the refinement and poetic sensibility of late-Mughal and Awadhi courtly aesthetics. The composition depicts a princess walking barefoot across a palace terrace late at night in an intimate moment, engaged in an act of quiet contemplation with a subtle sense of resolve. The artist employs a darkened background to evoke the enveloping night sky, enhancing the luminosity of the central figure whose delicate features, dress, and jewelry gleam in contrast. Awadhi miniatures often incorporate a diverse range of painting techniques, with specific interest in the interplay of light and shadow, as well as a more precise rendering of volume and spatial depth.

The princess is dressed in an elegantly pleated and embroidered golden skirt with a deep orange blouse. She gently draws her sheer dupatta (shawl) forward with one hand to partially veil her face, and perhaps wishing to remain hidden in the night. The fabric of her dress is rendered with an exquisite attention to textile detailing, showcasing the artist’s ability to convey the rich and graceful qualities of the princess. Soft shading across her form brings a sense of volume and dimensionality to the central figure. She is also adorned with a string of pearls draped around her neck, wrists, forehead,

and toes with various jewels embellished throughout, emphasizing her regal presence. Looking more closely, alta (red dye) decorates the tips of her fingers, toes, and the soles of her feet, denoting her status as a married woman. She also holds up a small diya (candle) to her face. Her ethereal presence in this scene is further accentuated by her serene expression and the soft upward curve of her lips.

A series of finely painted jharokhas (arched windows) frame the princess in the evening scene, and floral motifs decorate the structure on the right. A crimson red balustrade in the background anchors the composition spatially and adds a rhythmic contrast to the princess’s gentle stride. The restrained yet vibrant color palette, with the interplay of warm ochres, muted blues, verdant greens, and bold reds, reflects the refined sensibilities of the period. Such nocturnal vignettes, often laden with poetic and literary associations, were favored subjects in courtly ateliers, illustrating themes of solitude, anticipation, and the fleeting nature of beauty.

The miniature painting is encased by a large vibrant yellow and red floral border, its repeating pattern heightened with gold leaf.

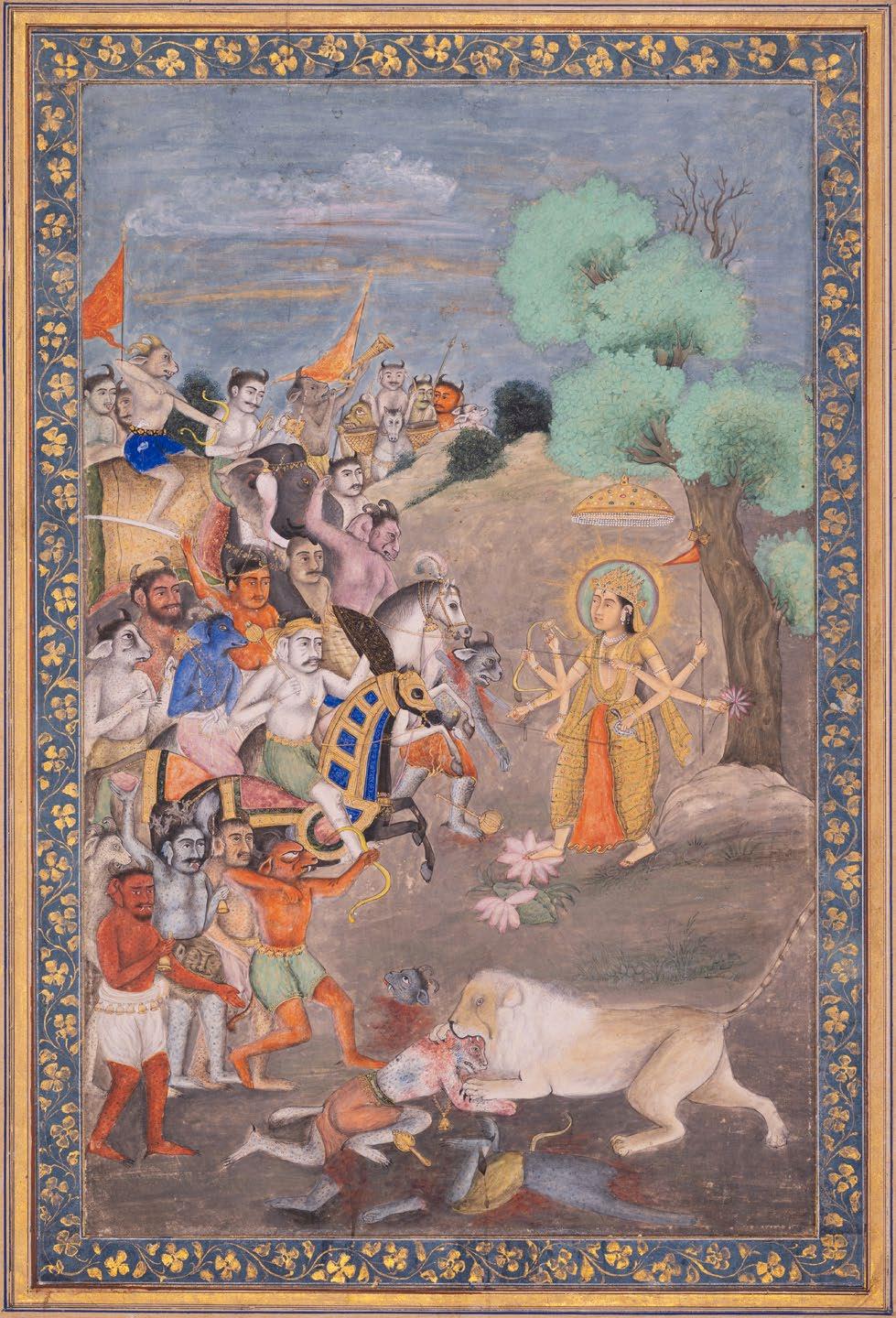

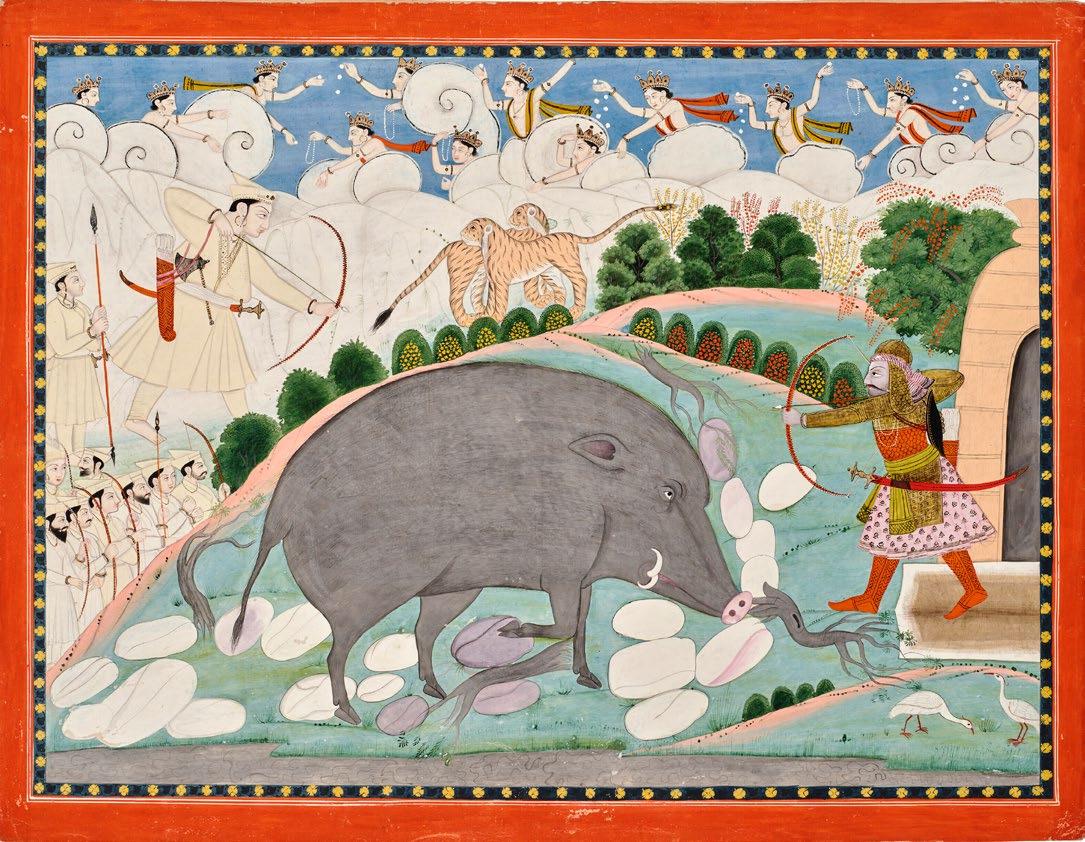

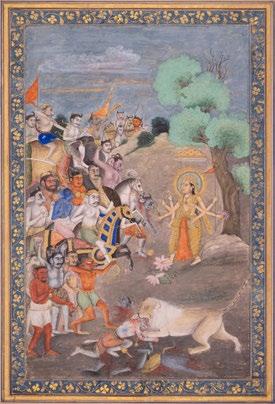

An Illustration from a Markendeya Purana Series: The Devimahatmya Mughal, circa 1700

Ink, opaque watercolor, heightened with gold on prepared paper 12 ⅜ x 8 ⅜ in. (31.4 x 21.2 cm.)

Provenance:

Allen and Matilda Alperton, San Francisco, CA, by repute. Acquired from Eugene Bernald, circa 1976, by repute.

An Illustration from a Markendeya Purana Series: The Devimahatmya Mughal, circa 1700

Ink, opaque watercolor, heightened with gold on prepared paper

12 ⅜ x 8 ⅜ in. (31.4 x 21.2 cm.)

Provenance:

Allen and Matilda Alperton, San Francisco, CA, by repute.

Acquired from Eugene Bernald, circa 1976, by repute.

The Devi Mahatmya, a revered section of text within the Markandeya Purana, is one of the most significant scriptures in the Shakta tradition, celebrating the Goddess Shakti as a supreme cosmic force. Comprising 700 verses across 13 chapters, it narrates the divine battles in which the Goddess, in her many manifestations, vanquishes powerful demons who threaten the balance of the universe. The text is structured around three major episodes: her defeat of the demons Madhu and Kaitabha, her triumph over the buffalo demon Mahishasura, and her ultimate victory against the brothers Shumbha and Nishumbha. These stories symbolize the triumph of good over evil and establish the Goddess as the embodiment of power, wisdom, and divine justice.

The present artwork captures a moment from one of these epic battles, though without inscriptions or identifying markers on the piece, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact episode depicted. The eight-armed Goddess stands at the center, facing a formidable horde of demons advancing from the left. Some of the asuras retain human-like features but are adorned with horns and antlers, while others appear in more grotesque, animalistic forms. Among them, a few charge into battle on horseback, while one demon,

seated atop an elephant, looms over the fray. At the rear, another figure beats a pair of kettle drums, rallying the army into action.

In the foreground, the Goddess’s vahana, the lion, pounces upon a demon, who may have emerged from behind the severed body lying below—a visual motif frequently referenced in the text. While the Devi Mahatmya often describes the Goddess manifesting in multiple forms to combat demonic forces, this artist has chosen to emphasize her singular presence, heightening the sense of her divine power. She stands resolute facing nearly two dozen adversaries, symbolizing the triumph of cosmic order over chaos.

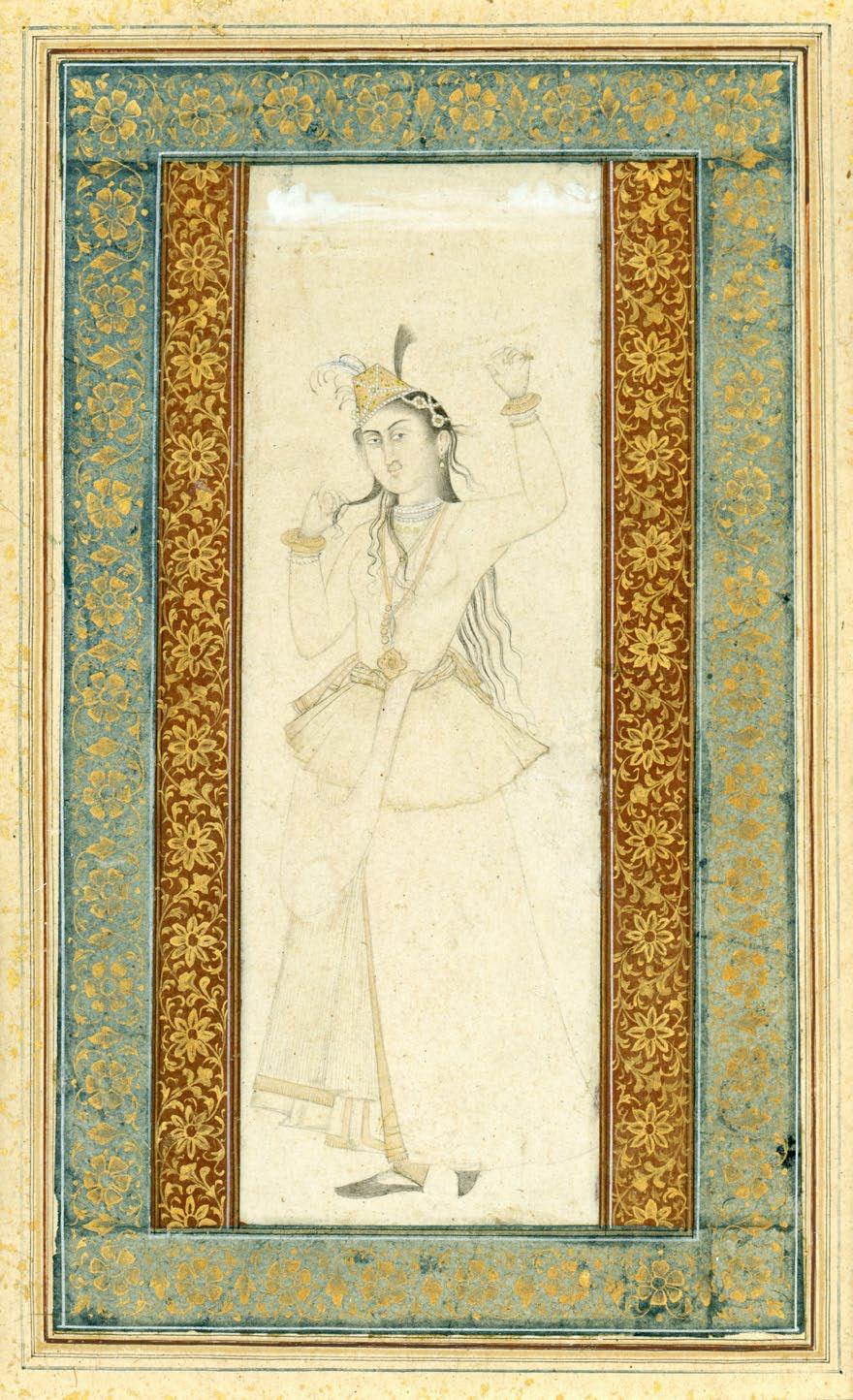

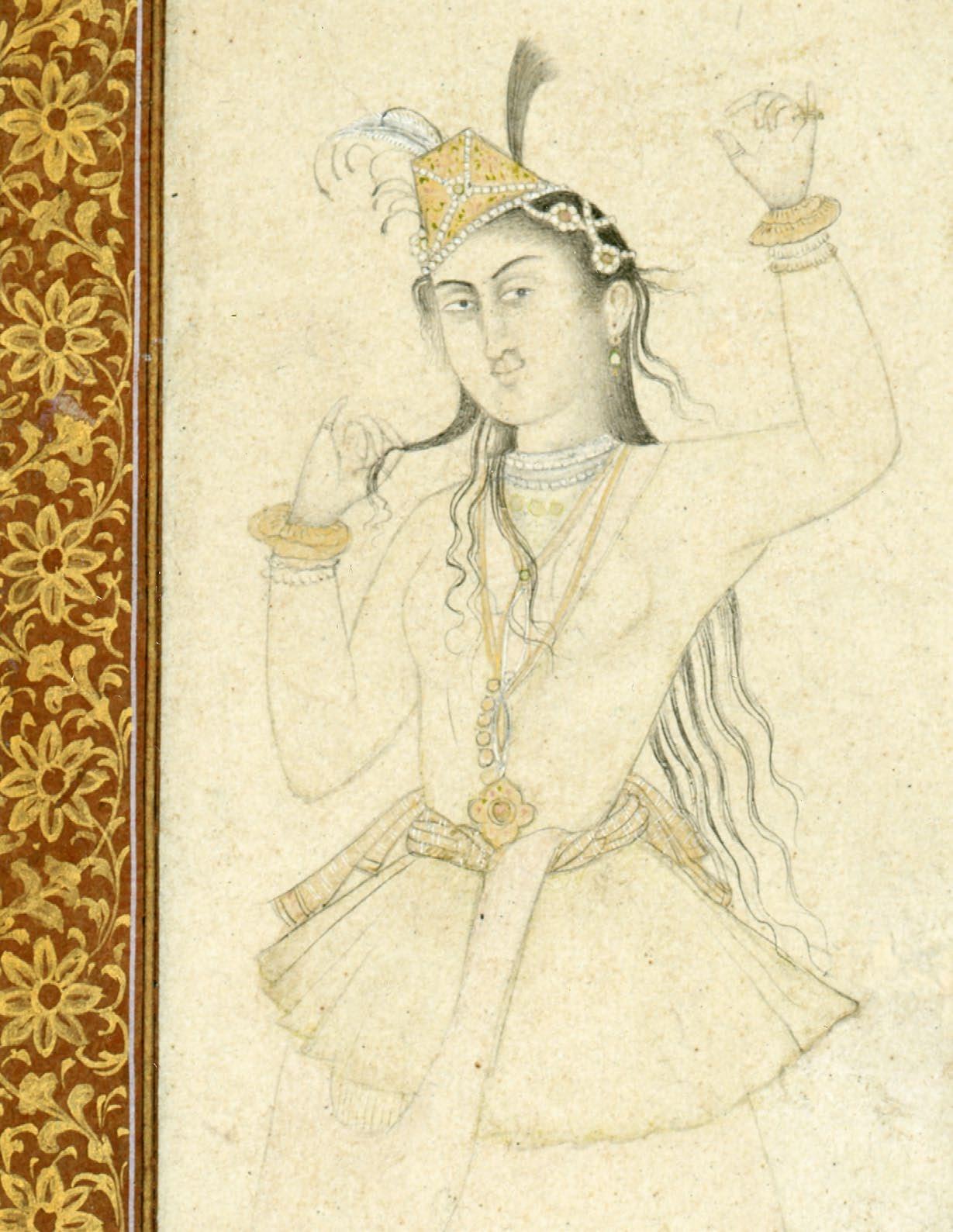

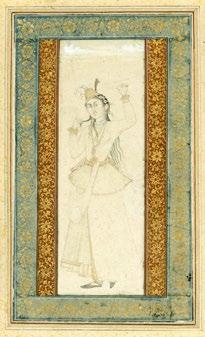

A Courtesan Dancer

Deccan, Golconda or Hyderabad, last quarter of the 17th century

Ink with embellishments in gold on paper Image: 7 3/4 x 2 5/8 in. (19.7 x 6.7 cm.)

Folio: 13 7/8 x 10 in. (35.2 x 25.4 cm.)

Provenance:

Saeed Motamed Collection. Christie’s London, 7 October 2013, lot 118.

Deccan, Golconda or Hyderabad, last quarter of the 17th century

Ink with embellishments in gold on paper

Image: 7 3/4 x 2 5/8 in. (19.7 x 6.7 cm.)

Folio: 13 7/8 x 10 in. (35.2 x 25.4 cm.)

Provenance:

Saeed Motamed Collection.

Christie’s London, 7 October 2013, lot 118.

The young dancer’s long wavy black hair falls in slender tresses down her back and over her shoulder. She is dressed in a Safavid Persianate manner and faces the viewer in three-quarter pose. She places her weight on one leg and twists rhythmically, her left hand raised up above her head and her right playfully pinching out a strand of hair. A feathered and gold cap with strands of pearls, gold bracelets and necklaces adorn her figure from head to foot.

Her near-frontal pose suggests that she is a courtesan—a princess, meanwhile, would typically be depicted in profile. Although the identity of this courtesan is unknown, she is depicted with realistic features, capturing a true representation of the sitter in a Mughal style. By this time, the Mughals conquered the Deccani Sultinate finalizing their triumph over the region. This portrait was executed when Mughal aesthetics dominated the Deccan, evident here in the realism and empty background with a carefully patterned outer border.

The present portrait is similar to a published painting of a Yogini with a Mynah Bird (Chester Beatty Museum, Dublin, Ireland, accession no. In 11A.31), depicted half length with a bold smile and full face. Both women project a similarly insouciant attitude. And for another

painting of a similar style and subject, reference A Dancing Courtesan – Folio from the Colebrook Album, North India, possibly Delhi region, from the early 19th century, executed in opaque pigments heightened with gold on paper and laid down on an album page (folio: 33.1 × 24.4 cm; painting: 21.5 × 14.4 cm).

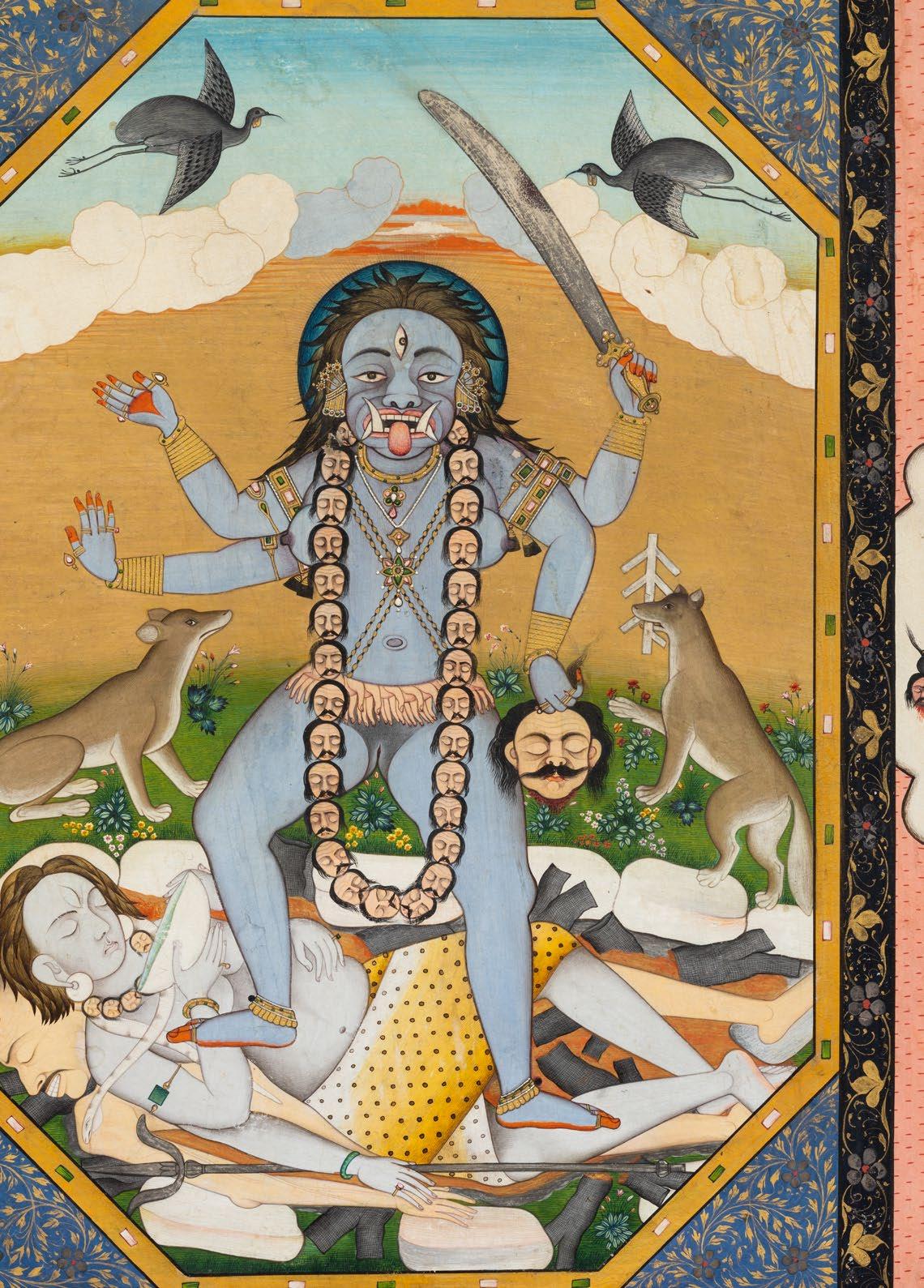

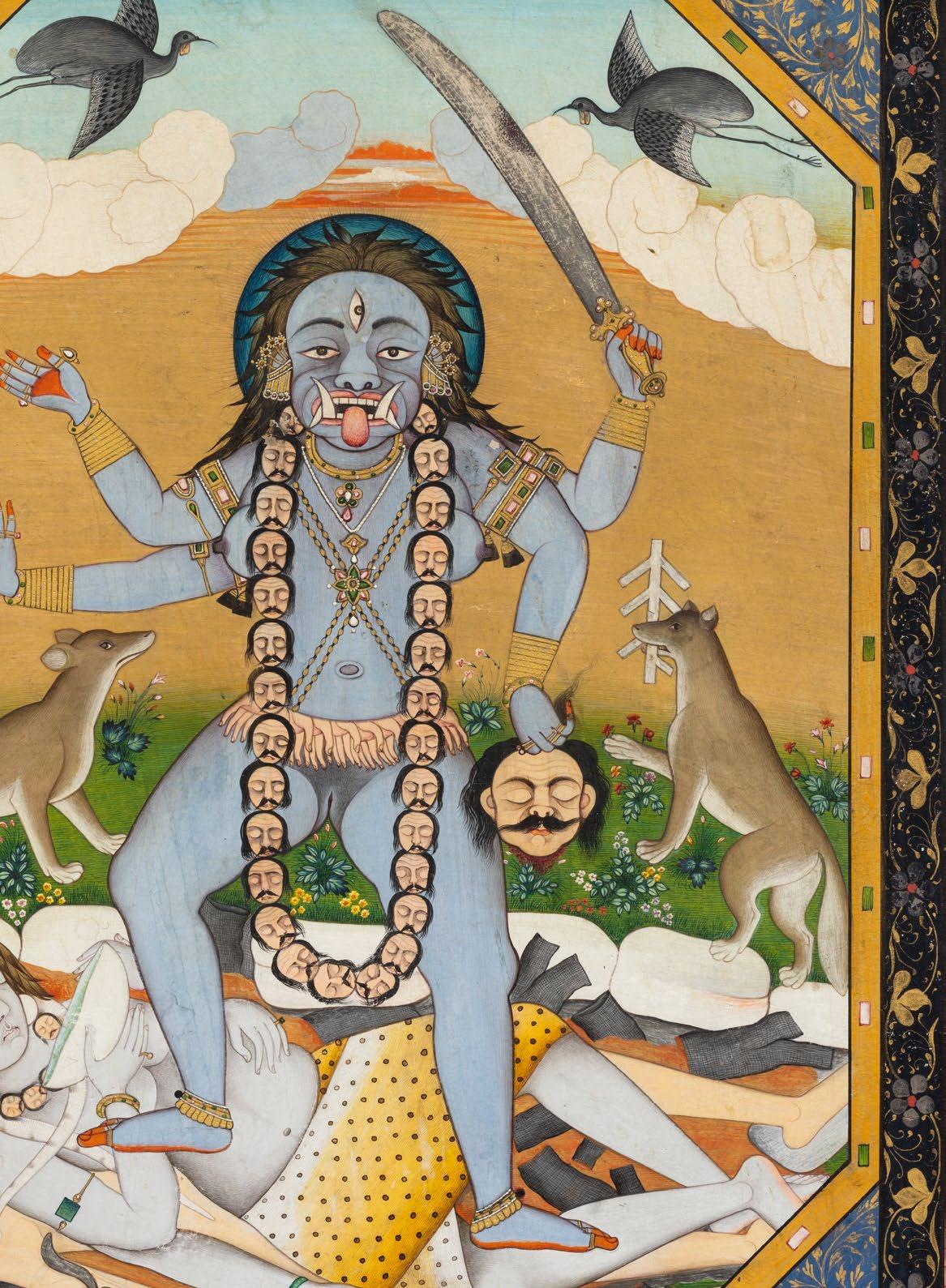

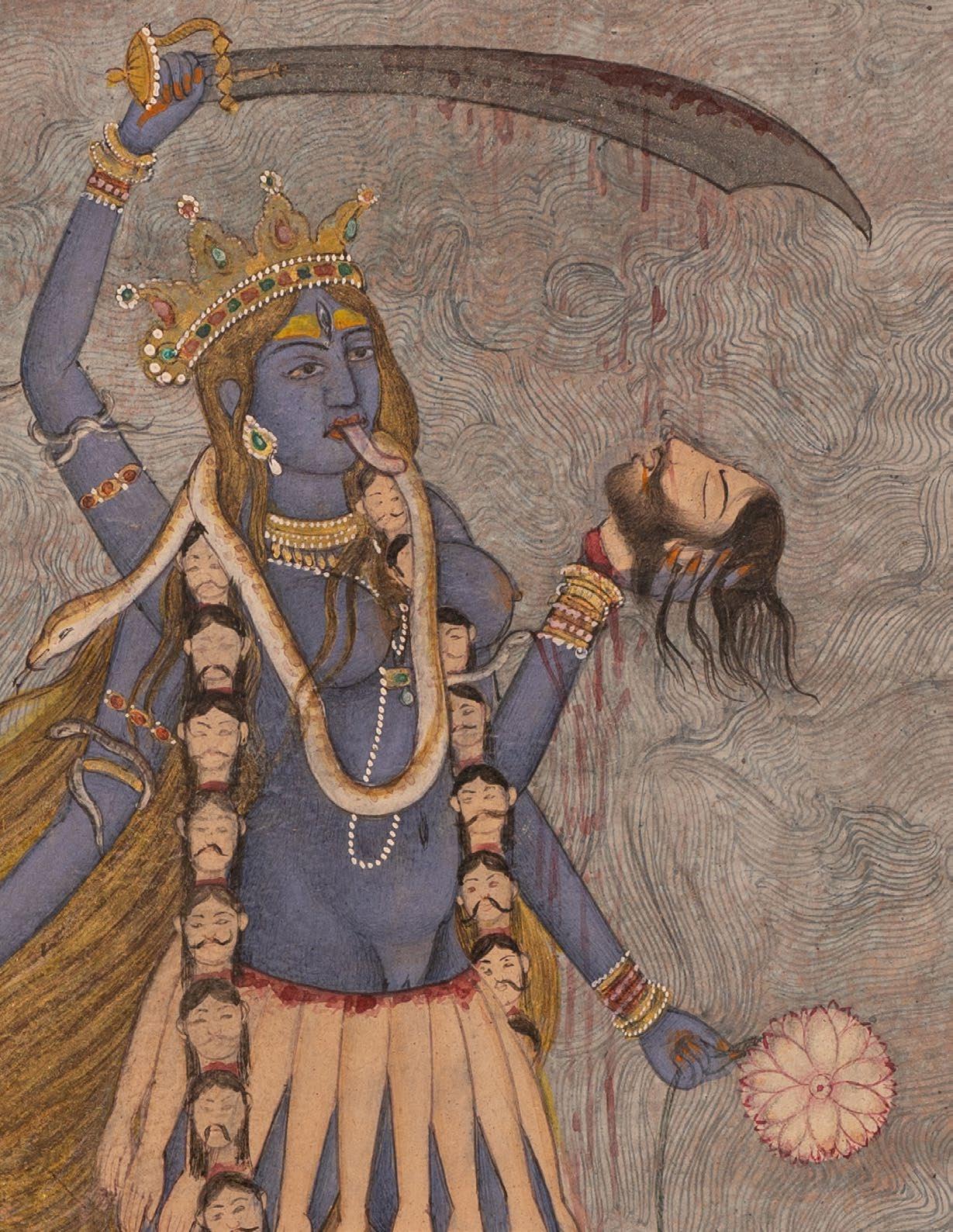

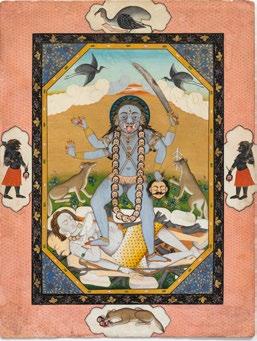

The Goddess Kali Attributed to Sajnu Mandi, North India, circa 1810

Opaque watercolors heightened with gold on paper 12 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (31.8 x 24.2 cm.)

Provenance: Private Swiss Collection.

Christie’s, London, 10 June 2015, Lot 70.

The Goddess Kali

Attributed to Sajnu Mandi, North India, circa 1810

Opaque watercolors heightened with gold on paper 12 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (31.8 x 24.2 cm.)

Provenance:

Private Swiss Collection.

Christie’s, London, 10 June 2015, Lot 70.

The goddess depicted in a classical stance after her killing spree, the third eye surmounts her tongue struck out in between protruding fangs, clad in a belt of decapitated hands and a necklace of severed heads as jagged hair runs down her shoulders. The manifestation of destruction and barrenness is seen brandishing a curved sword (kharga), holding a decapitated head, with a foot over Shiva’s body. Jackals and vultures surround the scene smelling death in the blood- saturated air. The illustration is centered in an octagonal medallion, the spandrels embellished with gold scrolling foliate tendrils, in black borders with scrollwork, wide pink margins containing further depictions of her emanations, cusped cartouches above and below with a vulture and a rat.

Mahakali, or “The Great Kali,” embodies the dual aspects of time and destruction, as well as the creative power (Shakti) fundamental to the cosmos. She is juxtaposed with Shiva, who symbolizes pure consciousness. This artwork is emblematic of monistic Shaktism and resonates with the Nondual Trika philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism. The depiction of Kali standing upon Shiva signifies the activation of the universe through Shakti, without which consciousness remains inert, akin to a corpse (Shava). This interplay highlights the necessity of balance between the forces of creation and destruction.

The distinctive elaborate margins of this work with cusped cartouches containing attendants of Kali and associated animals are similar to those found on a painting of Raja Isvari Sen of Mandi worshiping Shiva attributed to artist Sajnu (W.G. Archer, Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills, London, 1973, fig. 46, p. 275).

About Sajnu: “Painting at Mandi, a relatively large kingdom in the Punjab Hills, did not really get underway until the middle of the eighteenth century. It reached an apogee of creativity during the reign of Raja Isvari Sen, who was under the cultural sway of painting mad Kangra and Guler, the two kingdoms which supplied a number of Isvari Sen’s favorite artists. His leading court painter was Sajnu, originally from Kangra or Guler. Sajnu, like Nainsukh and the Basohli Master of the Early Rasamanjari before him, did much to transform the style of painting everywhere in the Punjab Hills. Early nineteenth century Pahari painting was greatly influenced.” (McInerney, Terence; Kossak, Steven; and Haidar, Navina. Divine Pleasures: Painting from India’s Rajput Courts. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016 pg. 238. Print.)

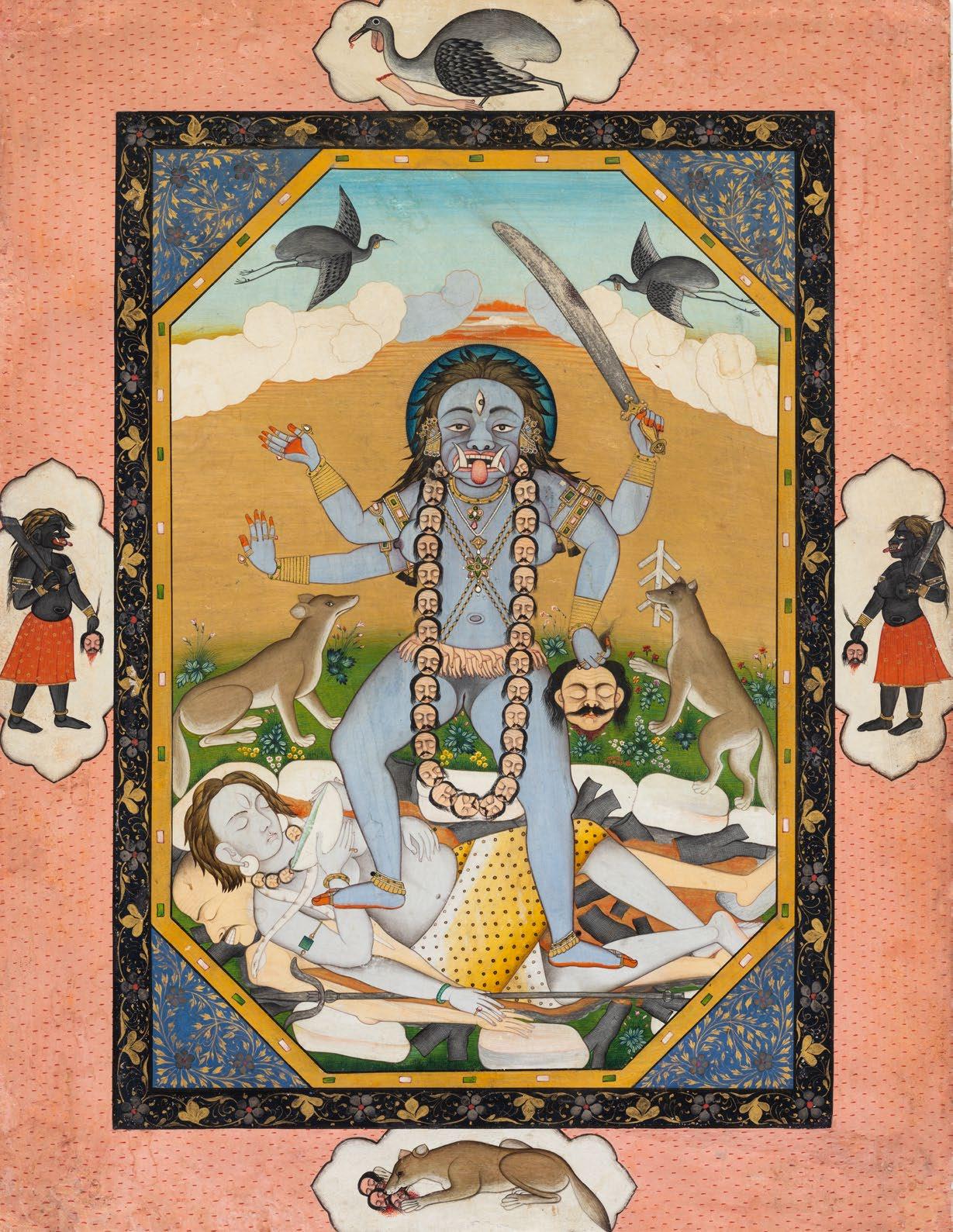

Kali Dances on Two Lovers Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India, circa 1840 Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper Image: 8 1/2 x 5 3/4 in. (21.5 x 14.6 cm.)

Folio: 11 x 8 1/8 in. (28 x 20.6 cm.)

Provenance:

Private European collection, by repute.

Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India, circa 1840

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Image: 8 1/2 x 5 3/4 in. (21.5 x 14.6 cm.)

Folio: 11 x 8 1/8 in. (28 x 20.6 cm.)

Provenance:

Private European collection, by repute.

The goddess depicted in a classical stance after her killing spree, the third eye surmounts her tongue struck out in between protruding fangs, clad in a belt of decapitated hands and a necklace of severed heads as jagged hair runs down her shoulders. The manifestation of destruction and barrenness is seen brandishing a curved sword (kharga), holding a decapitated head, with a foot over Shiva’s body. Jackals and vultures surround the scene smelling death in the blood- saturated air. The illustration is centered in an octagonal medallion, the spandrels embellished with gold scrolling foliate tendrils, in black borders with scrollwork, wide pink margins containing further depictions of her emanations, cusped cartouches above and below with a vulture and a rat.

Mahakali, or “The Great Kali,” embodies the dual aspects of time and destruction, as well as the creative power (Shakti) fundamental to the cosmos. She is juxtaposed with Shiva, who symbolizes pure consciousness. This artwork is emblematic of monistic Shaktism and resonates with the Nondual Trika philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism. The depiction of Kali standing upon Shiva signifies the activation of the universe through Shakti, without which consciousness remains inert, akin to a corpse (Shava). This interplay highlights the necessity of balance between the forces of creation and destruction.

The distinctive elaborate margins of this work with cusped cartouches containing attendants of Kali and associated animals are similar to those found on a painting of Raja Isvari Sen of Mandi worshiping Shiva attributed to artist Sajnu (W.G. Archer, Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills, London, 1973, fig. 46, p. 275).

About Sajnu: “Painting at Mandi, a relatively large kingdom in the Punjab Hills, did not really get underway until the middle of the eighteenth century. It reached an apogee of creativity during the reign of Raja Isvari Sen, who was under the cultural sway of painting mad Kangra and Guler, the two kingdoms which supplied a number of Isvari Sen’s favorite artists. His leading court painter was Sajnu, originally from Kangra or Guler. Sajnu, like Nainsukh and the Basohli Master of the Early Rasamanjari before him, did much to transform the style of painting everywhere in the Punjab Hills. Early nineteenth century Pahari painting was greatly influenced.” (McInerney, Terence; Kossak, Steven; and Haidar, Navina. Divine Pleasures: Painting from India’s Rajput Courts. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016 pg. 238. Print.)

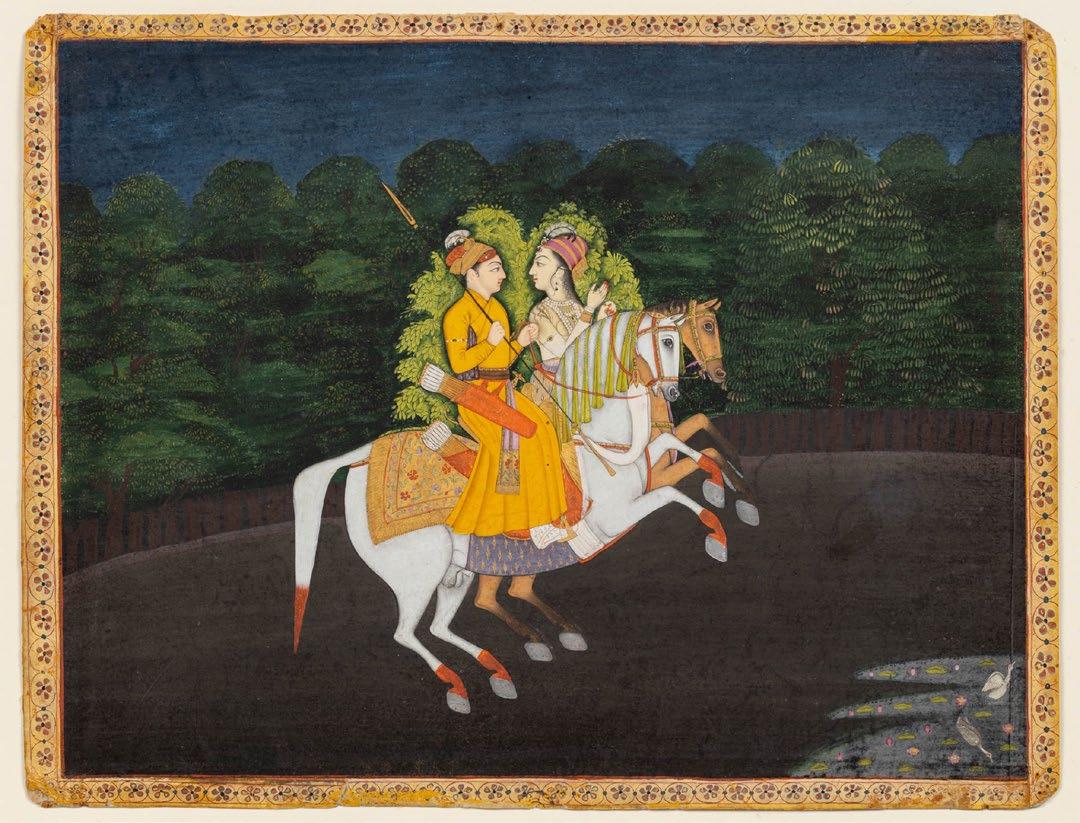

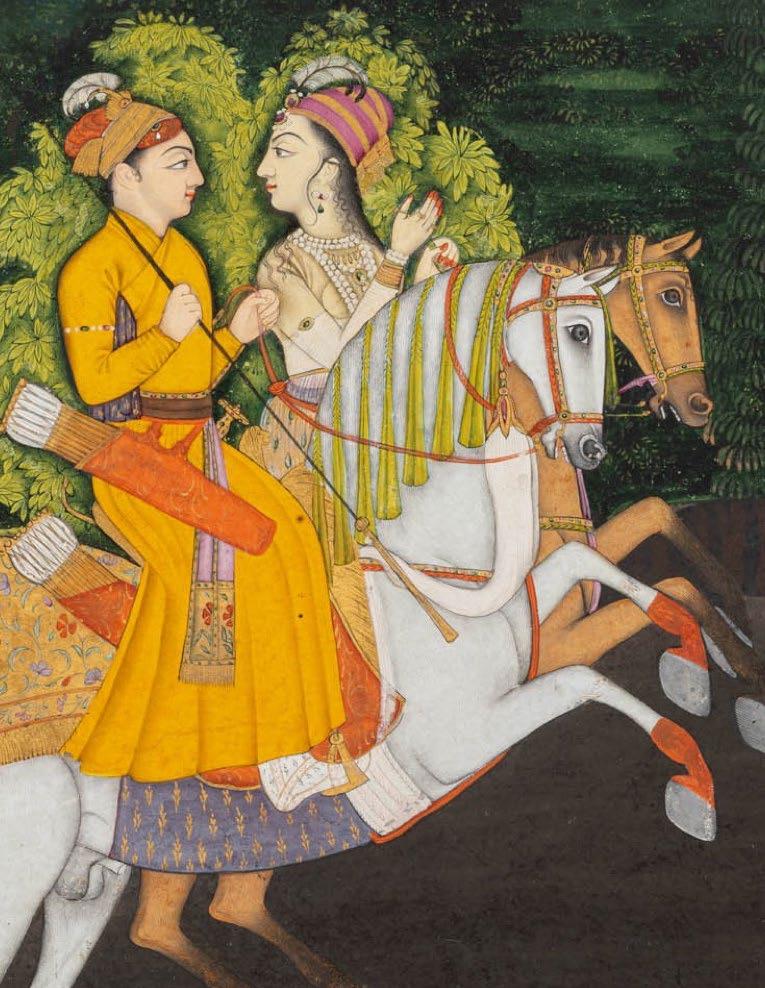

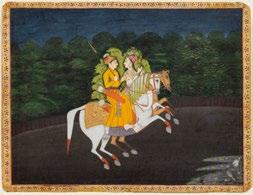

Baz Bahadur and Rupmati Riding at Night Mughal, probably Awadh, circa 1800 Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper Image: 7 3/4 x 10 1/8 in. (19.7 x 25.7 cm.)

Folio: 8 3/8 x 10 7/8 in. (21.2 x 27.6 cm.)

Published:

Daniel J. Ehnbom, Indian Miniatures: The Ehrenfeld Collection, New York, 1985, no. 30, pp. 76-77.

Provenance:

The Ehrenfeld Collection, California. Sotheby’s New York, 6 October 1990, lot 19.

Carlton Rochell Asian Art, New York.

The Sterling Collection, U.S., 2011.

07 Baz Bahadur and Rupmati Riding at Night

Mughal, probably Awadh, circa 1800

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 3/4 x 10 1/8 in. (19.7 x 25.7 cm.)

Folio: 8 3/8 x 10 7/8 in. (21.2 x 27.6 cm.)

Published:

Daniel J. Ehnbom, Indian Miniatures: The Ehrenfeld Collection, New York, 1985, no. 30, pp. 76-77.

Provenance:

The Ehrenfeld Collection, California.

Sotheby’s New York, 6 October 1990, lot 19.

Carlton Rochell Asian Art, New York.

The Sterling Collection, U.S., 2011.

Baz Bahadur of Mandu, the last King of the Malwa Sultanate (r. 1555-1562), is depicted here riding with his beloved Rupmati on a pair of horses. They gallop in sync through the darkened night landscape, rearing up in perfect unison as the lovers gaze into each other’s eyes. They seem to glow with an otherworldly radiance, their energy illuminating the green bush behind them like a spotlit stage. A lotus-filled pond with a pair of birds bathing is depicted below.

Although the Muslim Baz Bahadur and the Hindu Rupmati were historical figures who lived and loved during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, their inspiring story has transcended into folklore and poetry.

Baz Bahadur was initially led to Rupmati by music he heard on a hunt. After years of palatial and romantic bliss, the two were divided by the 1661 Mughal conquest of Mandu, whereupon Rupmati chose death over being taken captive. Thus, they are the archetypal tragic lovers—an Indian version of Romeo and Juliet—and are represented here in this stunning miniature as idealized types, raised to heroic perfection.

While it is apparent that these are not actual portraits, we can nevertheless immediately recognize them as Baz and Rupmati with the help of longstanding visual

conventions associated with their story: Baz Bahadur bears a long spear, two quivers of arrows, a bow, and a sword. Their eyes meet as their caparisoned horses lift them in a united stride.

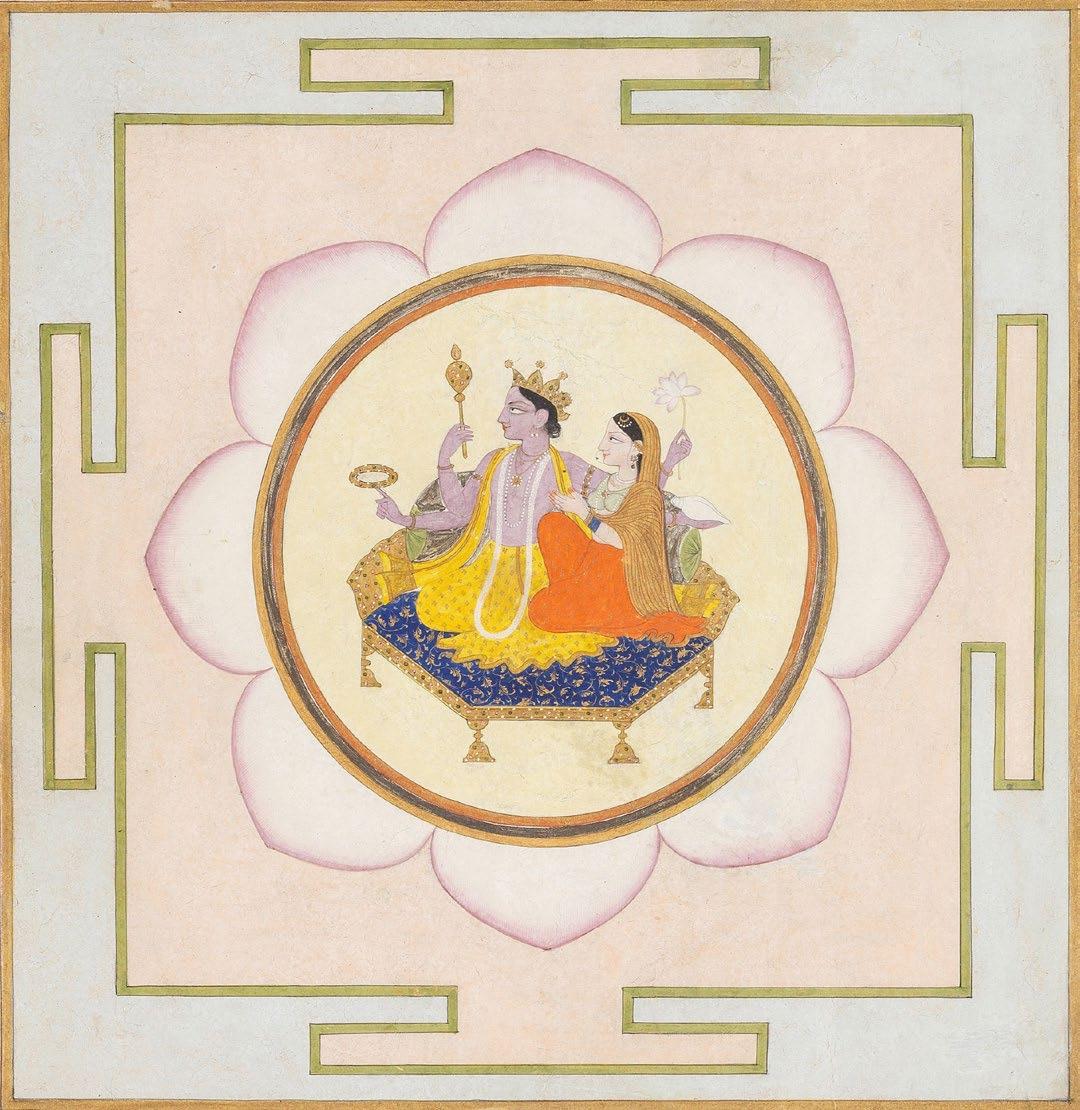

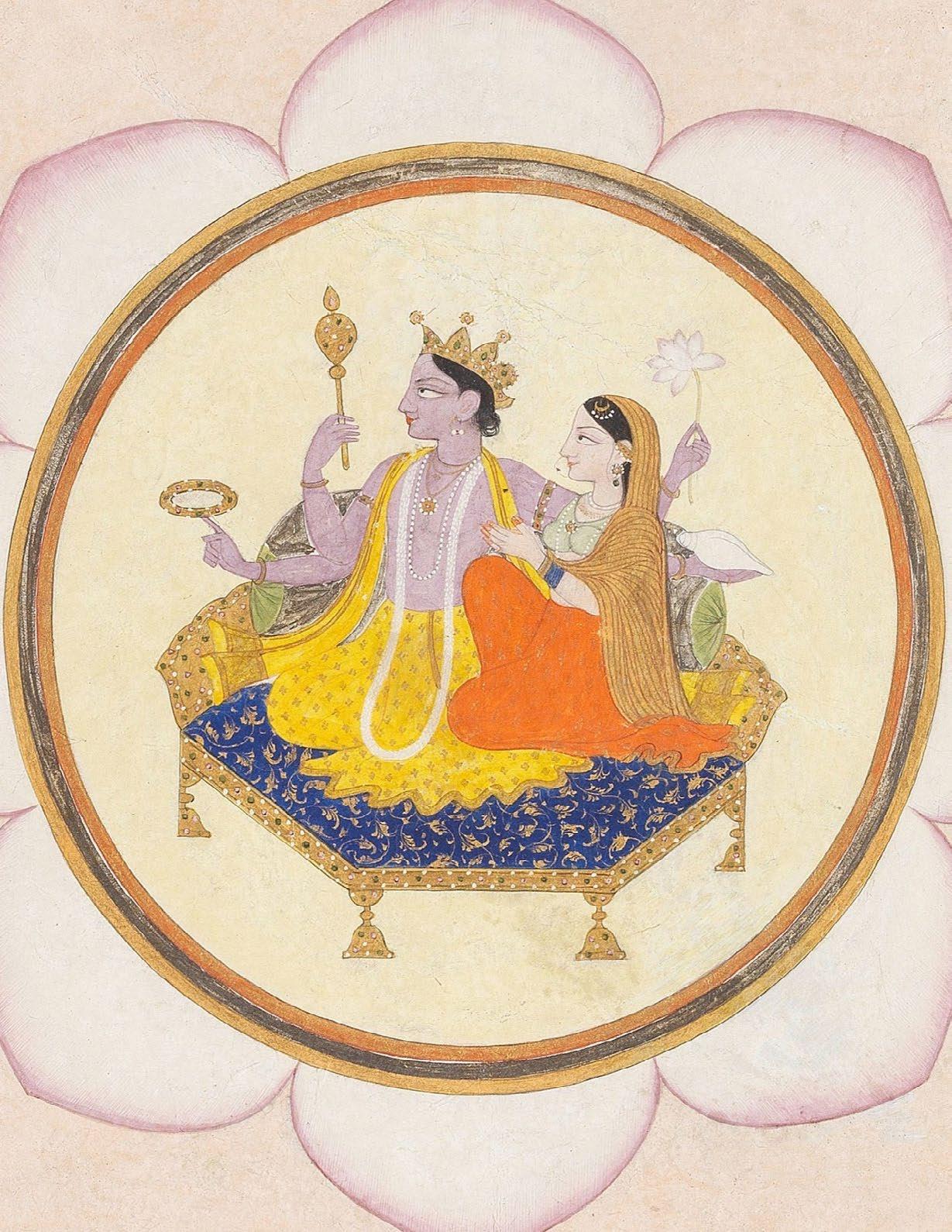

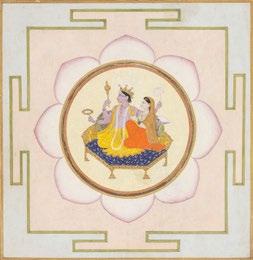

Lakshmi-Narayana Enthroned Kangra, dated Samvat 1845 (1788 C.E.) Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 8 ¼ x 8 ⅛ in. (21 x 20.7 cm.)

Provenance: Hearst & Hearst, Boston, early 1980s. Private Boston collection.

08 Lakshmi-Narayana Enthroned Kangra, dated Samvat 1845 (1788 C.E.)

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 8 ¼ x 8 ⅛ in. (21 x 20.7 cm.)

Provenance:

Hearst & Hearst, Boston, early 1980s.

Private Boston collection.

Vishnu the Preserver appears here in his Chaturbhuja (four-armed) form, enthroned beside his consort Lakshmi. The god’s identity is revealed by his blue-toned skin and vibrant yellow dhoti as well as the objects he carries in each of his four hands: a discus (chakra), mace (gada), conch (shankha), and lotus. Both deities are illustrated in an opulent manner–garbed in vibrant colors and lavish pearl, emerald, and gold accessories–which follows the typical convention for depicting Vishnu as a king and Lakshmi as the goddess of wealth and prosperity.

Perhaps most notable, however, is the placement of the divine couple within a yantra—a rare practice in Indian miniature painting. Yantras are tantric diagrams used in homes and temples to aid in meditation and can be of several types. The present painting displays a pujayantra, which is invoked in the worship of specific deities. Vishnu and Lakshmi are encircled within a border surrounded by eight lotus petals pointing in the cardinal and intermediate directions. Yantras often include lotus petals—a symbol of purity, transcendence, and fertility—in various numbers, but with eight being one of the most common. The lotus is then enclosed in a square with four gates–sacred doorways also pointing in the four cardinal directions—a standard convention in the representation of yantras.

The painting’s verso is dated Samvat 1845 (1788 C.E.) and inscribed with a devanagari couplet that translates to:

“May Lord, [I pray], please listen to the songs (bhajana) about the suffering of the world (bhava-peer)

Save me! Save me! O Raghu Veer, the one who takes away all sorrows and gives happiness to all.”

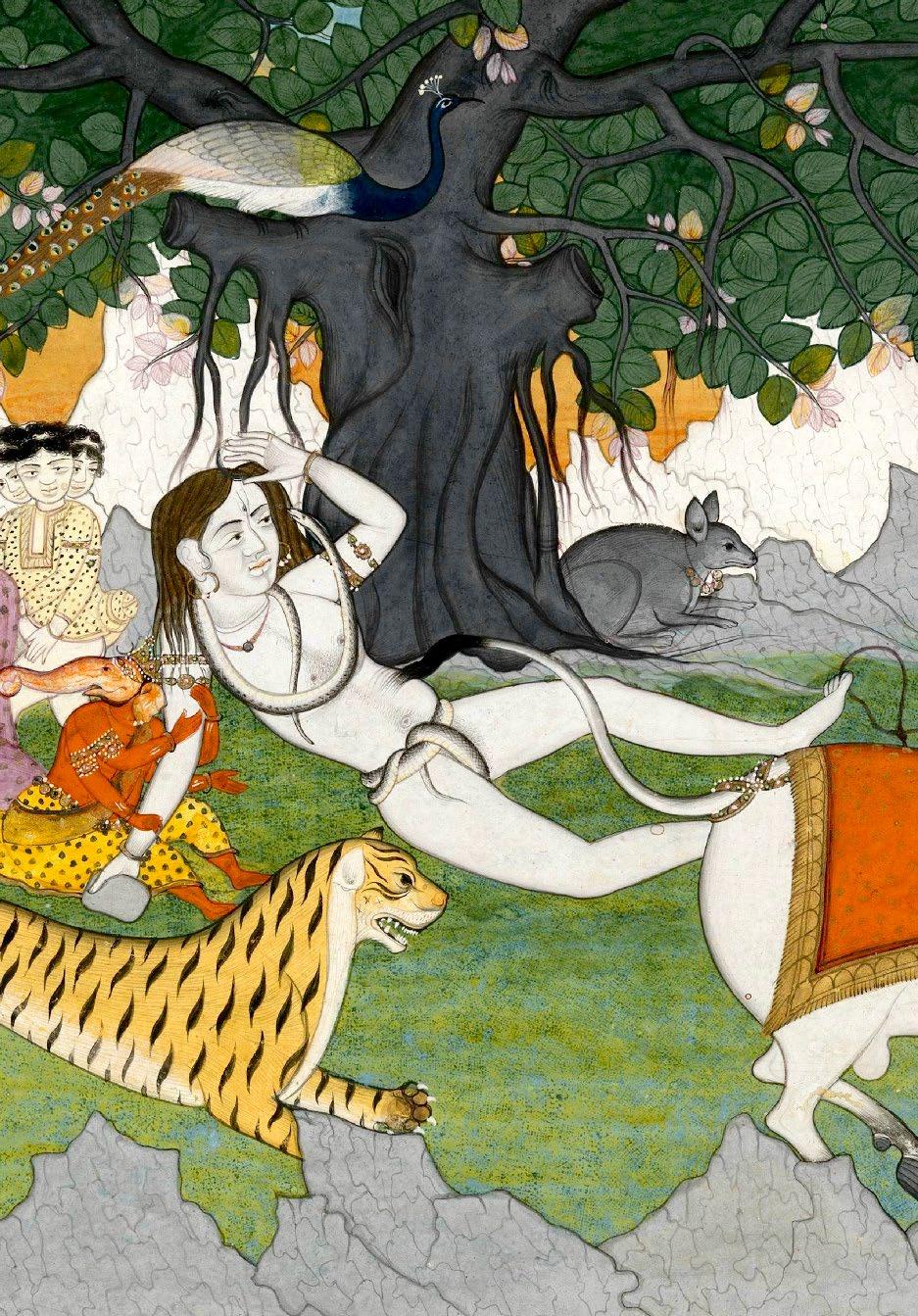

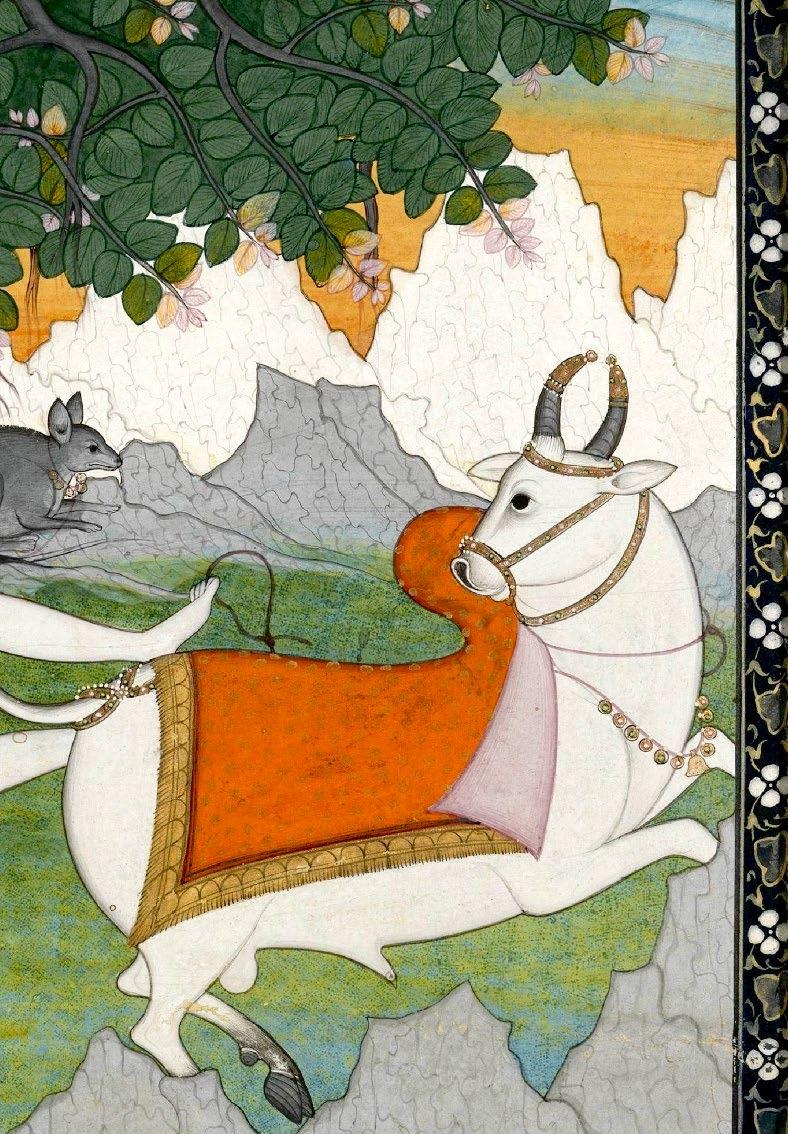

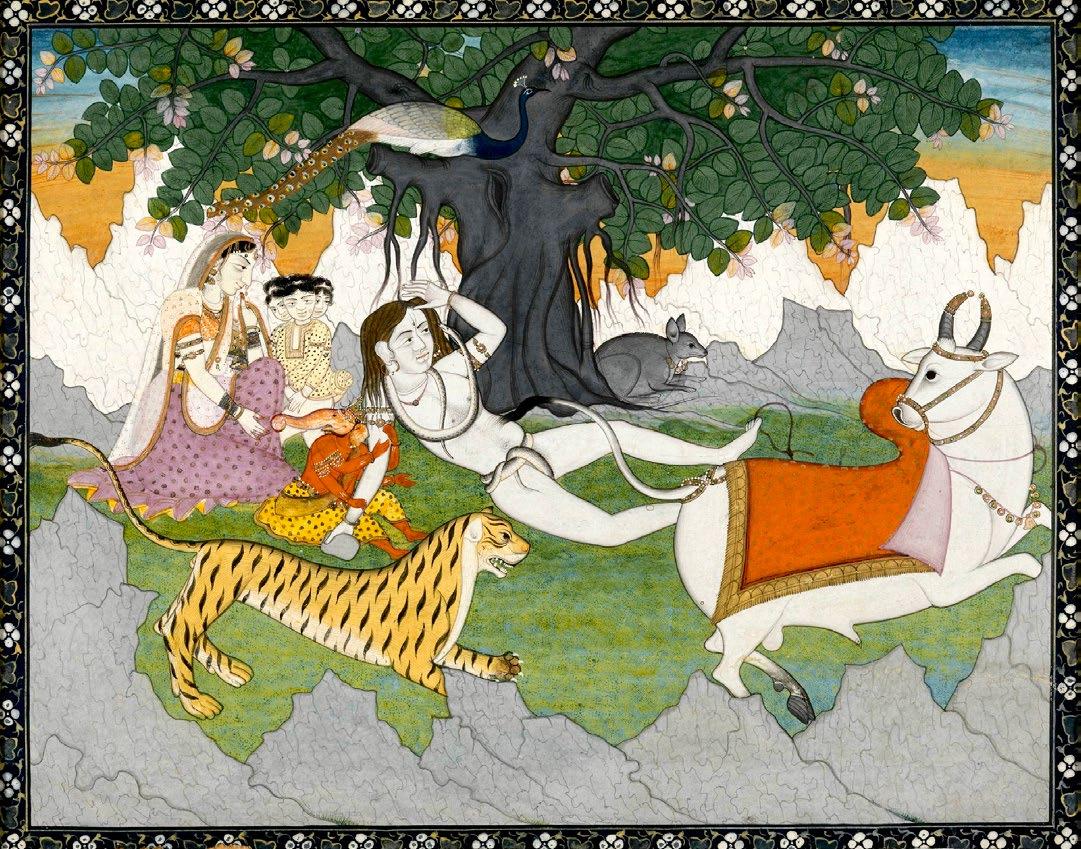

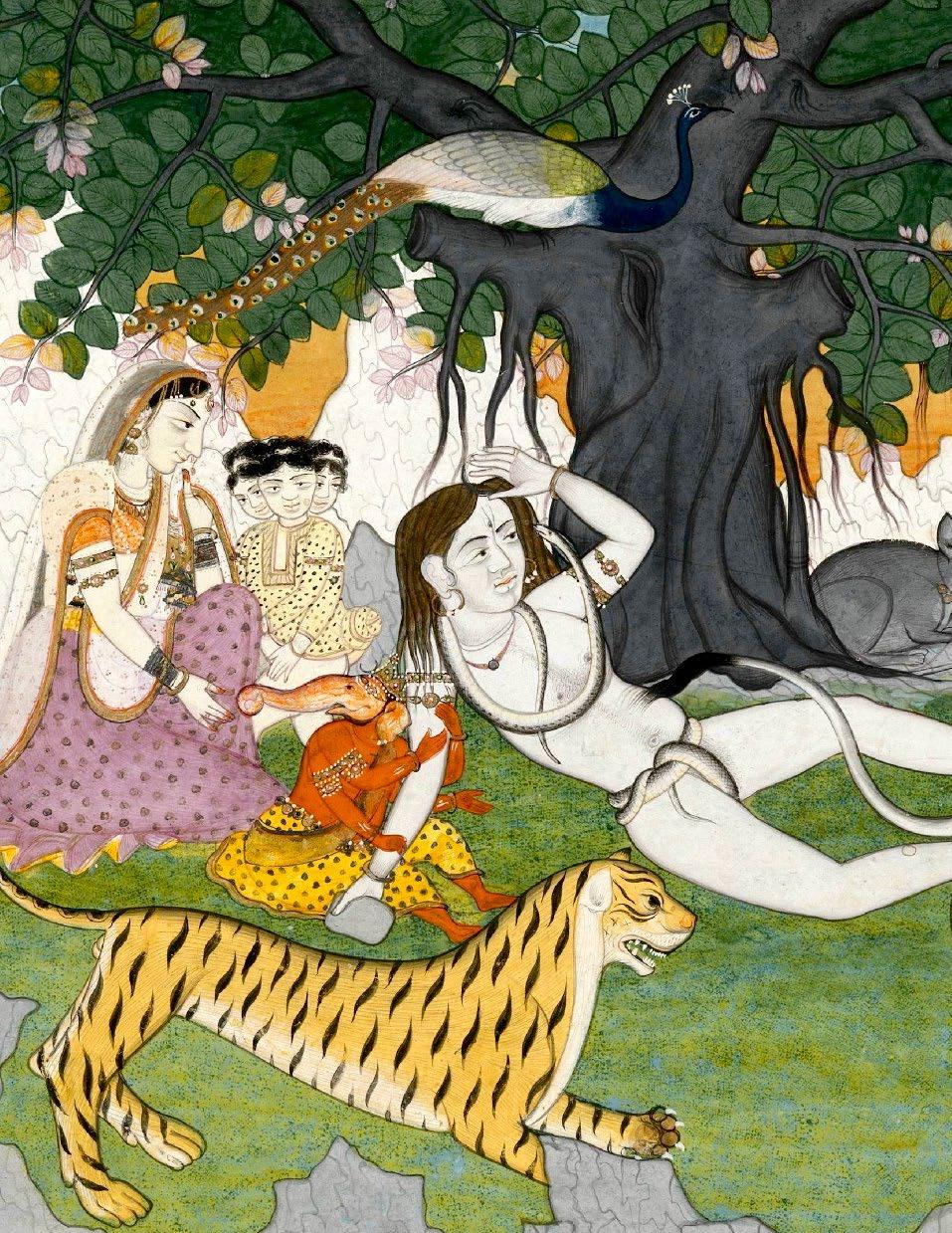

Shiva Under the Influence of Bhang Kangra, India, 1810-1820

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 11 ¾ x 7 in. (29.5 x 18 cm.)

Provenance:

Private German collection.

Private UK collection.

Shiva Under the Influence of Bhang

Kangra, India, 1810-1820

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 11 ¾ x 7 in. (29.5 x 18 cm.)

Provenance:

Private German collection.

Private UK collection.

The present painting depicts Lord Shiva and his wife Parvati, as well as their two sons, Karttikeya (Skanda) and the elephant-headed Ganesha. Their respective vahanas (vehicles) are shown here as well–Parvati’s tiger, Karttikeya’s peacock, Ganesha’s rat, and Shiva’s sacred bull, Nandi. Shiva reclines against a banyan tree in a drunken stupor as the young Ganesha clutches at his arm. He is shown here in the nude except for two vine-like snakes that serve as his undergarments and necklace, mirroring the god’s characteristic matted locks and the aerial roots of the banyan tree above. In his right hand he holds a cup of Bhang, a traditional Indian beverage infused with cannabis–often associated with Shiva and his devotees–which is said to help Shiva focus inward, allowing him to harness his divine powers.

Scenes of the Holy Family are a popular theme in the Pahari school of painting and often show the family in domestic bliss. See another depiction of the Holy Family, attributed to Purkhu, currently at the Victoria & Albert Museum (acc. 4648C/(IS)). This painting also features Shiva, cup of Bhang in hand, with his family in their home atop Mount Kailash, surrounded by the distinctive jagged peaks of the Himalayas. See also a comparable image at the Los Angeles Museum of Art (acc. M.2009.148.2), which depicts Ravana receiving the

Pashupatastra weapon from Shiva. In particular, the rendering of the banyan tree, with the pinkish hue of the new growths, is remarkably similar.

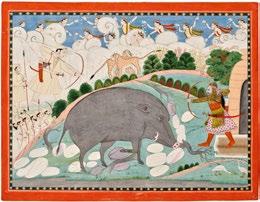

Illustration to Kirata-Arjuniya Episode, from a Mahabharata Series Attributed to Purkhu Kangra, India, circa 1820 Opaque watercolor on paper, heightened with gold Image: 13 ¾ x 18 ½ in. (34.93 x 47 cm.)

Folio: 15 ½ x 19 ⅞ in. (39.4 x 50.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired from the Doris Weiner Gallery by repute. Private Virginia collection, thence by descent.

Illustration to Kirata-Arjuniya Episode, from a Mahabharata Series

Attributed to Purkhu Kangra, India, circa 1820

Opaque watercolor on paper, heightened with gold

Image: 13 ¾ x 18 ½ in. (34.93 x 47 cm.)

Folio: 15 ½ x 19 ⅞ in. (39.4 x 50.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired from the Doris Weiner Gallery by repute.

Private Virginia collection, thence by descent.

A Sanskrit epic, written by Bhairavi in the 6th century, the Kirata-Arjuniya episode revolves around the encounter of Pandava Prince Arjun with Lord Shiva (in disguise of a Kirata, a mountain dwelling hunter).

During the Pandavas’ exile, Arjuna encountered a demon in the form of a boar. After Arjuna killed the boar in selfdefense, a dispute arose with Shiva, disguised as a hunter, claiming he had shot first. Despite Arjuna’s use of divine weapons, he couldn’t defeat the hunter. Recognizing the hunter as Shiva, Arjuna sought forgiveness. Shiva revealed his identity, and blessed Arjuna with powerful weapons, including the Pashupatastra, strengthening him for the Kurukshetra War.

This artwork beautifully encapsulates the quintessence of the Kangra style by incorporating a distinctive bold border adorned with foliate motifs that gracefully traverse the composition. The airbrushed portrayal of trees and the opulent landscape, coupled with the application of linear perspective for depth, depicts the typical Kangra paintings of its era. Notably, the majority of figures are depicted inside or quarter profile. The meticulous detailing of weaponry, jewels, and clothing in the depictions of Arjuna as a warrior prince and Shiva

as the Kirata hunter underscores the exquisite artistry inherent in Kangra miniatures.

Refer to a similar painting (M.70.38.1) from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art which comprises the same subject matter.

For any inquiries about the works presented in this catalog, please reach out to Kapoor Galleries via email (info@kapoors.com) or phone (+1 (212) 888-2257). Thank you!