CASE: GS-84

DATE: 8/7/13

QUIRKY:A BUSINESS BASED ON MAKING INVENTION

ACCESSIBLE

We are not here to build a startup business, we are here to unlock the creative potential of the universe. To solve problems in the most unconventional ways. To find folks in the middle of an African village who have great ideas for how our lives could be better. That is the big idea.

To Make Invention Accessible. Period. No Comma.

Now, here’s the rub… We’re not a non-profit. We are a well-funded startup business with a responsibility to our employees and our shareholders.

Ben Kaufman, founder and CEO of Quirky1

In March 2009, Ben Kaufman founded Quirky, a company that enabled anyone with a product idea to access an online network of people to help evaluate and improve the idea, and potentially bring it to market. Though only 22 years old when he founded Quirky, Kaufman was already a successful serial entrepreneur. While a high school student, he had started a company to make

1 Internal memorandum.

David Hoyt and Michael Marks, Lecturer in Operations, Information and Technology, prepared this case as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

At the time this case was written, Quirky was a private company, not subject to public disclosure requirements. The authors thank Ben Kaufman and Quirky for their extraordinary support in providing and allowing publication of data from internal documents and financial information.

Copyright © 2013 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. Publically available cases are distributed through Harvard Business Publishing at hbsp.harvard.edu and The Case Centre at thecasecentre.org, please contact them to order copies and request permission to reproduce materials. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the permission of the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Every effort has been made to respect copyright and to contact copyright holders as appropriate. If you are a copyright holder and have concerns, please contact the Case Writing Office at cwo@gsb.stanford.edu or write to Case Writing Office, Stanford Graduate School of Business, Knight Management Center, 655 Knight Way, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5015.

accessories for Apple products. He sold that venture and started a second company to develop an online platform for problem solving. His goal for Quirky was to “make invention accessible,” giving anyone the possibility to have the satisfaction he had gained by seeing products he had invented being used by the public.

By the end of 2012, Quirky was taking three product ideas each week submitted by online community members into the research and development process. Many of these ideas would eventually be manufactured and marketed. Revenues were growing rapidly, reaching more than $16.7 million in 2012, the third full year of shipments. Quirky products were available in about 35,000 stores worldwide.

Quirky faced a number of challenges. Margins were low and had to be improved for the company to become profitable. Its product development model, using a combination of online participants and internal staff, was under stress as the number of products under development rapidly increased, the company was challenged to effectively manage these projects without adding excessive overhead. And its supply chain, which relied on external manufacturing and sales, had to adapt to a continual stream of new products. It was particularly difficult for thirdparty retailers to adapt to the Quirky model, with a continual stream of new products, as the retailers concentrated on a relatively few, well-established, high-selling products. In addition, they could not convey the unique Quirky model, nor the story behind each product, to their customers.

BEN KAUFMAN AND THE ORIGINS OF QUIRKY

In early 2005, Ben Kaufman had a product idea a lanyard headphone for the iPad that he had prototyped from ribbon and wire. At the time, Kaufman was an 18 year old high school senior. He convinced his parents to remortgage their house, and with $185,000 he flew to China to arrange for the product (the “Song Sling”) to be manufactured. He launched his new company “Mophie,” (named for his dogs Molly and Sophie) the day he graduated from high school.2

In January 2006, Mophie was awarded “Best of Show” at MacWorld for a modular case accessory system, and raised $1.5 million in venture funding, with which the company developed a range of accessories for Apple mobile products. At the next MacWorld, Kaufman gave pads of paper to 30,000 people, asking them to design his next product line. He promised to take one of these ideas from initial sketch to delivery-ready in 72 hours. One attendee gave him a sketch of a bottle opener for the iPod Shuffle. Kaufman put the sketch online, and thousands of people from around the world helped develop the product, “Bevy,” an integrated case, bottle opener, cord management system, and keychain for the iPod Shuffle.3 Mophie was soon selling the product worldwide. The buzz generated by involving the community in product development immediately established the Mophie brand.

Excited by the power of an engaged community, Kaufman sold Mophie and formed Kluster, a company that developed a platform for online problem solving. Companies could use this

2This section is heavily drawn from comments by Ben Kaufman, in the video “The Path to Quirky,” http://www.quirky.com/learn/videos (accessed March 20, 2013).

3 Erick Schonfeld, “First Look: Kluster’s Market Approach to Crowdsourcing,” TechCrunch, February 18, 2008, http://techcrunch.com/2008/02/18/first-look-klusters-market-approach-to-crowdsourcing/ (accessed March 20, 2013).

platform to describe problems or projects, such as designing a new product, logo, or marketing campaign, or solving a technical problem, and offer cash rewards for people who contributed solutions.4

Despite Kluster’s progress, Kaufman missed the satisfaction of producing tangible products. He recalled riding the subway in New York six months after creating the Song Sling, and seeing someone using it. He called it, “the best feeling in the world: ‘Holy s**t! I made that!’”5 He wanted that feeling again, and wanted other people to feel it as well.

Kaufman founded Quirky in March 2009 to enable people to present product ideas and mobilize the power of an online community to evaluate, develop, and refine these ideas. Quirky would build an internal staff, including designers and engineers, to bring the best of those products to market. Products would be sold under the Quirky brand, and members of the community who participated would receive royalty payments based on their contributions. (See Exhibit 1 for a timetable of events from Mophie to Quirky.)

QUIRKY

In Kaufman’s words, “I strongly believe that Making Invention Accessible is the most important job we will ever do. Humans are wired to invent, and unlocking that potential [in] each and every person will have lasting effects on the world. This is why I wake up in the morning. This is why we are doing what we are doing.”6

Taking an idea from conception through to a product on a retail shelf was a daunting proposition. Many people had ideas for products that solved problems they encountered in their daily lives, or that they thought would be desired by others. However, engineering a product, obtaining patents, and packaging, pricing, manufacturing, and distributing new products required time, technical and business expertise, and capital far beyond what most people possessed, or could invest. Enabling someone with an idea to develop a marketable product was what Kaufman meant by making invention accessible.

Accessibility applied not just to the person with the initial product idea, but those with the time, interest, and ability to help develop that idea into a product determine design properties, features, color, name, tagline, price, and myriad other details. Most products were developed by a team of engineers, designers, and marketers working inside a company, often involving a relatively small set of customers participating in surveys or focus groups. But this was a minute subset of people who might be interested in the product and able to contribute to its development. Making invention accessible included giving any interested person the opportunity to participate in the process of turning an idea into a product on the market.

While making invention accessible was the company’s primary mission, Kaufman also recognized the necessity of building a sustainable business. In a board presentation in early 2013, he presented the criteria for making strategic decisions as:7

4 Ibid.

5 Quirky Series C presentation.

6 Internal memorandum.

7 Quirky board presentation, January 18, 2013.

The Quirky Process

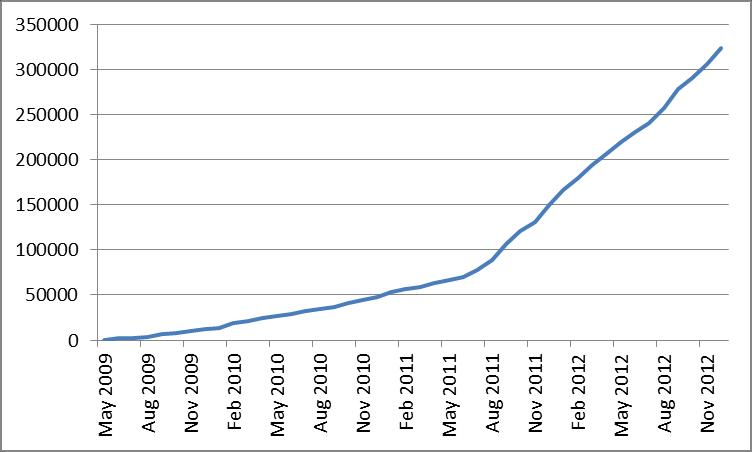

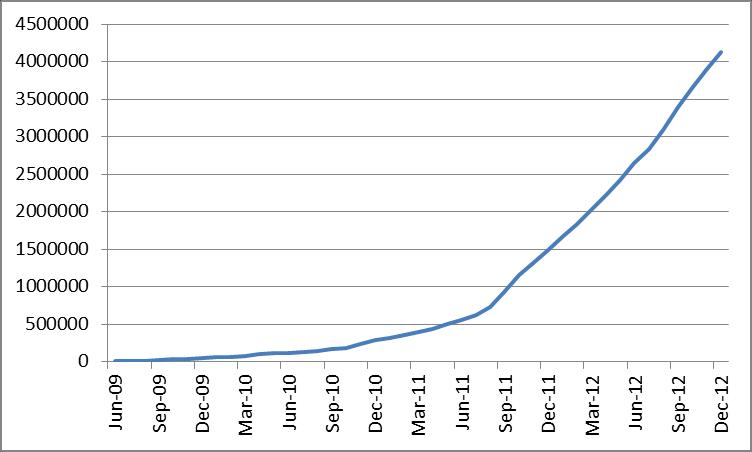

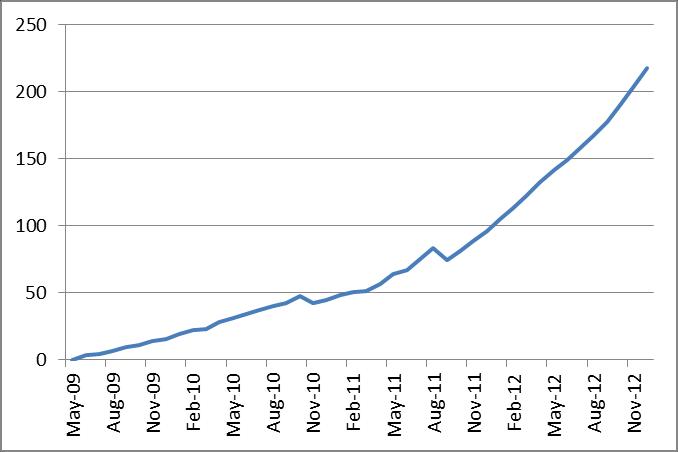

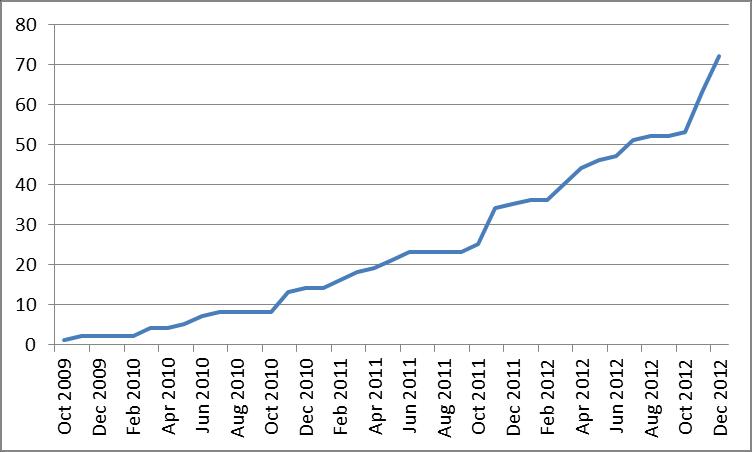

The product development process followed by Quirky (Exhibit 2) involved participation of both an online community and in-house staff—creating what the company called “a socially developed product.” By the end of 2012, there were more than 320,000 registered Quirky members. (See Exhibit 3 for growth of the user community over time.)

The process began when someone (the “inventor”) submitted an idea to the company Website (quirky.com). Members submitted an average of more than 1,100 ideas each week by the end of 2012 an average submission rate that had increased from just 200 at the end of 2010. To submit an idea, a member filled out a simple online form, including the following items:

Idea description (limited to 140 characters)

Product category (such as “kitchen” or “lawn & garden”)

Problem to be solved

Solution to the problem

Key features of the product

Similar products.

The inventor could also attach files, such as a quick sketch, a detailed drawing, or a video. There was a $10 fee to submit an idea.

After an idea was submitted, it was shown on the Quirky Website, and members had 30 days to vote for those that they liked. Members could also comment on the idea, suggest improvements, or express concerns. Quirky’s staff also evaluated the ideas. About 20 ideas each week were selected to be discussed at product evaluation meetings each Thursday evening. These meetings were run by Quirky staff and included a live audience (Exhibit 4). They were also webcast, so that online participants could observe, submit comments, and vote for the ideas they liked best. By 2012, 470 products were “picked” through this evaluation process. The community then helped with the design of the product. In addition to helping define product features, the community also participated in other ways, such as naming the product, devising a tagline, selecting colors, and completing market research surveys. To help maintain involvement, Quirky sent periodic updates to members who had expressed interest in specific products by participating in projects related to those products. After products completed the collaborative design process, they were “launched” into the Quirky website’s “Upcoming” section. By the end of 2012, 276 of the 470 picked products (59 percent) had completed design and been launched, while the remaining 196 were still being worked on by the community and Quirky staff.

Once in the Upcoming section, the community helped establish the price by participating in the “Quirky Pricing Game,” in which the product was described and members were asked a series of questions the price at which the product was expensive but still worth buying, the price at which it was too expensive, the price at which it would be perceived as too cheap or of poor quality, and the price at which it would be a good bargain. Answers to these questions were displayed in a graphic showing the average results of all participating members. (Members could also report that they were not interested in the item, regardless of price.) At the same time, Quirky staff discussed the products with retailers to determine interest and validate price assumptions, and with suppliers to estimate product costs and make sure they were compatible with the expected selling prices. For products in existing lines of business, such as kitchen, this was straightforward Quirky went to its primary kitchen suppliers and got a quick cost estimate. For products that required new manufacturing techniques and sources, Quirky’s head of manufacturing, located in Hong Kong, sought out potential suppliers and received high-level cost estimates.

Throughout this process, from initial idea submission through participation in the pricing game, members earned “influence” credit for participating, which generated cash “community rewards” payments once the product shipped. These payments totaled 30 percent of revenue generated by direct sales through Quirky.com, and 10 percent of revenue generated from indirect sales, such as in Target or Bed Bath & Beyond stores. The distribution of these payments to influencers was based on their contribution the person who submitted the original idea received the highest percentage, but people who submitted ideas that improved the product also received a portion of the community payments, as did those who provided competitive comparisons, voted for the product, completed research surveys, provided design help, participated in the pricing game, named the product, or suggested the product’s tagline.8 Community rewards totaled more than $2 million in 2012.9

About 40 percent of products in the Upcoming section went no further there might be insufficient retail interest, or expected prices and costs did not provide an acceptable margin. For new product categories, which would require new suppliers and distribution channels, the bar for giving a product the “green light” for production was higher than for existing categories with established suppliers and distribution.

The other 50-60 percent of products moved into the “We’re Making” section of the Website. When the product passed into this phase, Quirky staff did the detailed engineering that was required for production. The time between being given the green light for production, and actually shipping varied some products might take 6-8 months before they were ready to ship. The final purchase orders for production were not released until the company had sufficient preorders, either online or through its retailers, to justify manufacturing a number that varied depending on the start-up production costs and product margins. (See Exhibit 5 for a graph of number of products ideas submitted and development phase over time.)

8 QuirkyWebsite, “Howto EarnInfluence,” http://www.quirky.com/learn/influence (accessed March 21, 2013).

9 Payments were made to community members after Quirky was paid for the product. The amount shown in the financial statements (typically 11-12 percent of revenues) is the total of payments already made, and those accrued, for products sold during the year.

By the end of 2012, 74 products had been shipped, accounting for 27 percent of the 276 launched into the Upcoming section. Another 59 were in the later stages of the manufacturing process, and scheduled to ship in early 2013, and 123 were waiting for confirmation of retail, pricing, and margin alignment. Just 20 had been abandoned.

The target shipment date varied depending on the timetable for shipment. For instance, “Crates” was a modular storage/furniture system based on a simple milk crate design concept, and well suited for college dorms. In order to have it available for the back-to-school buying season, Quirky had to go from initial sketch to delivery to stores in 100 days. Production and shipment from China, where most of Quirky’s products were made, would have taken too long, so tooling was made in New Jersey and the product was made in Vermont with the product on store shelves in time for students to buy for their dorm rooms. The first shipment of Crates was in June 2012. By the end of 2012, more than 178,000 units of Crates had been sold, generating over $1.4 million in revenue and more than $142,000 in community earnings10 its inventor, Jenny Drinkard, earned more than $80,000.

One of the fastest products to be produced was “Pluck,” a device to separate egg yolks. Pluck consisted of two molded parts, one made of silicone and the other plastic. Due to the enthusiasm the product generated from members, as well as its simple production, Quirky rushed it to market the time from initial submission to the Website to delivery to Bed Bath & Beyond was just 29 days.

At the other extreme were products that required more complicated assembly, or regulatory approval, such as “Pivot Power,” the company’s most successful product. Pivot Power was a flexible power strip that could be adjusted so that each outlet could be used, even if one or more large power adapters were plugged into it. The regulatory process meant that this product took about 10 months to get to market. Pivot Power was first shipped in June 2011. By the end of 2012 it had sold more than 653,000 units, generated more than $10.5 million in revenue, resulting in more than $1.1 million in community earnings, including $407,000 to inventor Jake Zien.11

In early 2013, about 90 percent of Quirky sales were through retail chains such as Target, Bed Bath & Beyond, OfficeMax, Home Depot, Staples, and Best Buy, and through televised home buying on QVC. Quirky products were available in 35,000 stores at the end of 2012, more than 10 times the 3,300 stores with Quirky products at the end of 2011. The remaining sales were through the company’s online store, Quirky.com.

Quirky Products

Quirky divided its product portfolio into categories. By early 2013, it sold products in 11 categories: Apple appliances, kitchen, toys, home decor, lawn and garden, electronics, organization, fitness, accessories, pets, and other. (See Exhibit 6 for photos of a selection of Quirky products.) The product distribution demonstrated a wide disparity between high sales volume of low priced products, and high revenues attributed to relatively few higher priced

10 Payments to the community were $51,000 as of the end of 2012, with the balance accrued until Quirky received payment for the product.

11 Payments to the community were over $500,000 as of the end of 2012, with the balance accrued until Quirky received payments for the product.

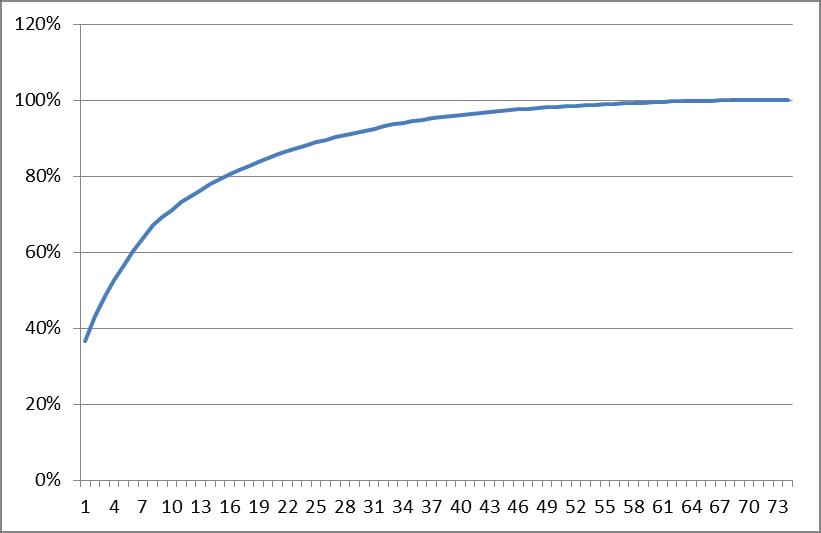

products (Exhibit 7). A relatively few products accounted for most of the company’s revenues (Exhibit 8).

The company also categorized ideas according to the effort that would be involved in developing them into products. About 45 percent of ideas were described as “bandits,” which could be developed in a couple of weeks by industrial designers with an investment of less than $5,000. These products were conceptually well-defined and proven, needing only refinement and styling. “Jammers” needed an overall conceptual review and multi-disciplinary knowledge, and accounted for about 40 percent of ideas. A team consisting of engineers and designers needed to completely rethink the idea to get at the root of the problem being solved. This typically took about one month and $15,000 before the product was ready to hand off for manufacturing. The third class of products, about 15 percent of ideas, was termed “epics.” These required about three months before being ready to manufacture.

Quirky had relatively little control over the ideas that flowed into its Website. As a result, the vast majority of products did a task that existing products already performed, but did it better. These products were less exciting to customers and retailers than products that did something that had not be possible before. Products that were the first of their kind offered the potential to get into new, high profile retailers, define the Quirky brand, and demonstrate the power of the Quirky model for social development of products however, these accounted for only a small fraction of ideas submitted.

Quirky Advanced Research Fund

One aspect of the Quirky model was that people tended to contribute ideas that were relatively simple, and similar to other Quirky products for instance, relatively simple molded products for routine kitchen chores. The Quirky staff was well suited to quickly and efficiently developing these ideas into finished products. The simplicity of Quirky’s products could be seen in the average selling price just $8.95 at the end of 2012, a slight decrease from the price a year earlier.

Sometimes, however, a member submitted an intriguing product idea that was complex, requiring substantial investment. For instance, one product submission was for a “granola machine” that would evenly mix and bake granola from any ingredients that the consumer put into the machine. There were no products on the market with this capability, and the community was enthusiastic about it. The community could help refine the product, complete market research surveys, and provide other support, but the detailed design and development would require substantial investment. The product involved motors and blades to mix ingredients, a baking oven, and substantially more sophistication than most Quirky products.

To support development of products such as the granola maker, in 2012 the company dedicated $2 million to the “Quirky Advanced Research Fund” (QARF). QARF products could require up to nine months of development, and $150,000-500,000 in development resources (either for adding new in-house resources or contracting with outside experts). To qualify for QARF funding, products had to have a retail price of at least $50, and potential revenue of at least $10 million within the first year of sales. The company’s objective was to add two to four QARF product lines each year.

Sales Channels

As previously noted, about 10 percent of Quirky’s sales were through the company’s Website, while the rest were sold through third parties such as Target and Bed Bath & Beyond. This posed challenges, as Quirky’s business model was based on a steady stream of new products. Traditional sales channels focused on a relatively few winners which were prominently featured on store shelves they were not equipped to handle a constant flow of new products. This was seen in the fact that 90 percent of the products widely distributed by retailers in the 2012 holiday season (accounting for 65 percent of revenue) had been available in the 2011 holiday season despite the development of many new products during the year.

Not only were third party sales channels focused on a relatively few products with established track records, and ill-equipped to handle the influx of new items, but they could not convey the compelling stories behind Quirky and its products. The typical Quirky product began with an ordinary person who faced a problem in everyday life. The story of that person, the problem he or she wanted to solve, and the Quirky community that rallied to help develop the solution, could create a level of consumer interest unlike anything generated by the marketing departments of a traditional corporate consumer goods manufacturer. Yet, stores could not convey the stories behind the products, and it was economically impractical to use valuable shelf space for storytelling materials when the products being sold had average selling prices of less than ten dollars.

Kaufman considered ways to improve third-party retailers’ ability to sell Quirky’s products, but also considered ways to take a more direct role in the selling process. One was establishing brick-and-mortar stores, where the company could tell its story, interact directly with customers, and feature all new products. Another was leasing space within existing retailers, such as department stores. In this approach, Quirky would set up its own displays, staffed by its own employees, and benefit from the flow of traffic provided by the host store but with the risk of confusion caused by customers not distinguishing between Quirky and host store employees, discounts, sales, and other activities.

Make or Buy, and Where?

From the beginning, Quirky had outsourced manufacturing to Asia. It managed manufacturing, warehousing, and logistics from an office in Hong Kong. The company’s first experience of manufacturing in the U.S. had been production of Crates, driven by the need to have the product in stores in time for back-to-school sales. Working closely with tool makers and molders in New Jersey and Vermont, Quirky was able to produce Crates quickly and then rapidly ship the bulky products to market.

Kaufman wanted to bring more production to the U.S., and he planned to experiment with one or two large projects each quarter to “learn what the limitations are, and what goes faster and what goes slower [in the U.S]. I do believe in the future of U.S. manufacturing. I think local manufacturing will be a big deal for Quirky.”12

12 Quotations from interviews with the author, unless otherwise specified.

He was planning for a major new product to be built entirely in the U.S. in 2013. “Drift,” a balance board that enabled users to simulate skateboarding, skiing, and other sports, would be built from four different sub-assemblies, made from cast aluminum, wood, spring steel, and plastics. The parts would be made in several locations throughout the U.S., and the product would give Quirky experience in dealing with more complex logistics than it had previously encountered. Kaufman said, “It’s a real challenge, and I’m watching it closely.”

Kaufman also considered whether Quirky should bring manufacturing in-house. If it did, what tasks should be internalized? The Quirky product line included lots of different types of parts (e.g., molded plastics and metals), and expansion into more sophisticated products would add even more manufacturing technologies (e.g., printed circuit boards and other electronics). Commenting on the question of bringing retailing and manufacturing in-house, Kaufman said, “I ultimately think we should be a retailer and we should be a manufacturer. I think those are the two things that people are most afraid for us to be, and I think the two things that will allow us to truly be what I want us to be.”

Scale and Geographic Expansion

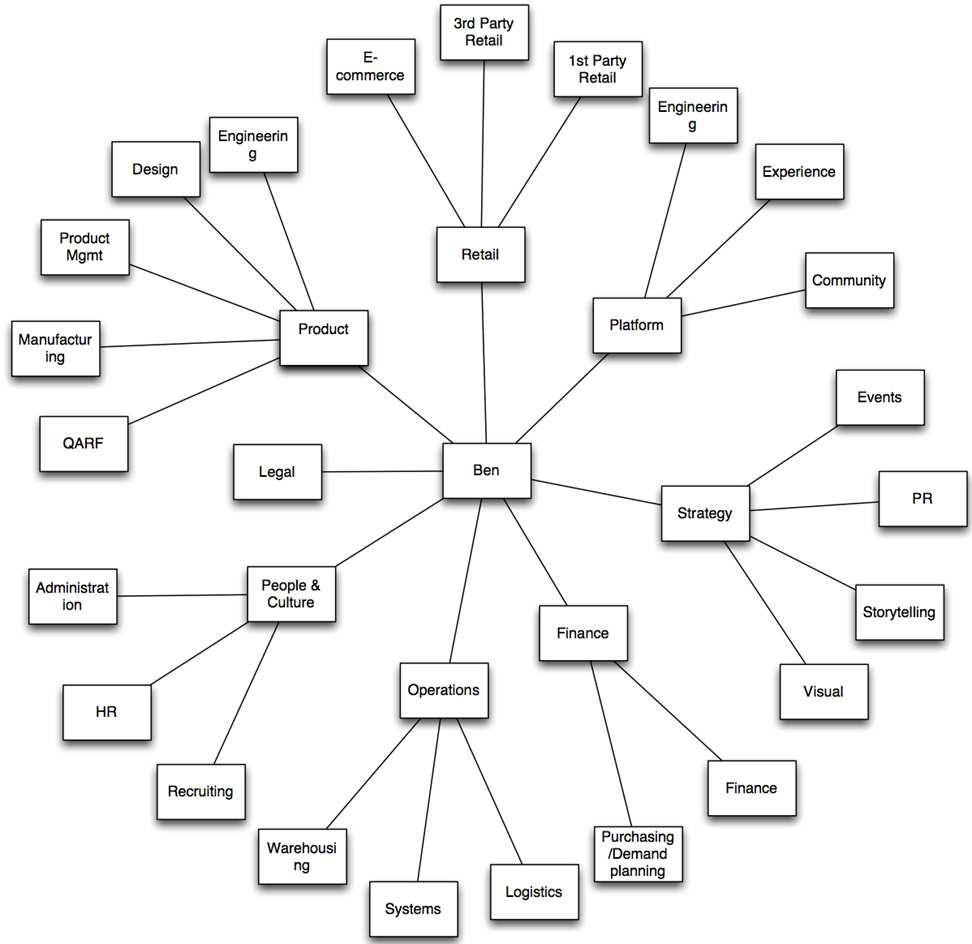

In early 2013, the entire Quirky product development process, generating three products per week, was based in its offices in New York City (see Exhibit 9 for company organization chart, and Exhibit 10 for photos of the Quirky facility). The operation had grown dramatically since its beginnings just three years earlier, yet Kaufman was concerned that the company risked losing its distinctive nature and becoming like other consumer product companies. It had added employees, structure, and procedures and the meetings and other complications that came with increased size. It needed to continue growing, while retaining the spontaneity and culture that had characterized its early days, when five people designed a product every week.

Quirky faced a challenge in providing support to the existing product base, and adding new products at an ever-increasing rate, without being dragged down by organizational overhead. One metric Kaufman used to measure product development efficiency was people-per-productper-week (PPPPW). In 2009, this metric was five. In September 2010, with about 35 people and two products per week, it was 17. By late 2012, it had grown to 37 (110 people and three products per week). Kaufman wanted to improve efficiency, bringing the metric down to 25 on a sustainable basis.

One idea was to create satellite Quirky offices, staffed by about 20 employees, which would focus on specific types of products and use unique local expertise. For instance, Quirky might open an office in San Francisco, focusing on consumer electronics and hardware, with a target of one new product each week. The office would include all the functions required to be selfsufficient, but due to its focus and small size, would be far more efficient than continued expansion of corporate headquarters. As of early 2013, the company had not experimented with any such satellites.

The satellite concept might, or might not, be the solution to the PPPPW deterioration; this could only be determined by trying the concept. There might be better solutions. But Kaufman was determined that Quirky would not allow its growth to undermine the attributes that he believed were essential to its importance and success.

Financials

Quirky was funded by a series of equity investments, beginning with seed capital raised to found Quirky in March 2009. Kaufman then raised his first round of venture funding, $11 million, just over a year later, in April 2010. Over the next two and a half years, he would raise an additional $16 million of Series B venture funding, and $43 million in Series C funding (net of $25 million that was used to pay existing investors). While revenues had grown rapidly, so had losses the company was still losing a substantial amount of money through 2012.

In 2012, Quirky lost $16.1 million on sales of $16.7 million a revenue increase of more than 250 percent the previous year. By increasing revenue and improving margins, the company anticipated reaching profitability by 2014. (See Exhibit 11 for annual financials from 2009 to 2012, and Exhibit 12 for 2012 quarterly financials.)

Kaufman eventually expected gross margins to reach more than 40 percent of revenue by 2014. In 2011, however, they were just 28 percent, decreasing to 24 percent in 2012. Both revenue and margins were impacted in the second half 2012 by a cash shortage due to delays in closing the Series C Preferred round of funding. Not wanting to commit to large inventory purchases until he had the money to pay for them, Kaufmann delayed placing orders for two months, and spent, in his words, “the rest of the year digging out from these decisions I made due to an apprehensiveness to spend money. Then we raised money, and we compensated for our lack of inventory by air freighting everything in and taking a margin hit.” The consequence was the loss of about $6 million in revenue in Q3 and Q4, and about $1.8 million in additional costs due to payments for air freight.

Margin improvements through volume increases and greater production experience occurred in the cases of Pivot Power and Cordies. Pivot Power margins increased from a negative 21.4 percent to a positive 20.6 percent in the first year of sales, while Cordies margins increased from a negative 11.8 percent in its first production run to a positive 55.3 percent in its second production run. These margin improvements came from product reengineering and redesign, changing sourcing, and increased quantity production. (See Exhibit 13 for details.)

Comparison to Other Consumer Product Companies

Quirky’s product development model distinguished it from traditional companies that relied on in-house personnel for product ideas and development. (See Exhibit 14 for financial data of other companies that developed products for consumer use.) Quirky’s model of community involvement provided access to a huge network of brainpower, experience, and passionate contributors to its products, which the company paid for through its community rewards program. However, these contributions needed to be used effectively by Quirky staff, and commercial proof of success was demonstrated by financial results. As of early 2013, Quirky was still in the development stage, and this success had not yet been demonstrated.

While Quirky’s model had not yet demonstrated financial success at the corporate level, some insiders suggested that it might be mutually beneficial for the company to partner with one or more established consumer product manufacturers. These companies had substantial credibility with the public, as well as success in creating and selling products. Furthermore, their brand reputation was strong and trusted by the public. On the other hand, Quirky was less well known,

and consumers might shy away from some products, such as those involved with user safety, that were branded as “quirky.”

If a relationship with a large, established company was of potential value, what form could it take, and what benefits could it offer each side?

FUTURE CHALLENGES

By the end of 2012, Quirky was selling 77 products that were the result of ideas and other contributions from its community of more than 320,000 online members. The company staff of 110 turned these ideas and inputs into products, and arranged for their manufacture and sale. Seven of these products had exceeded $1 million in revenue. Overall revenues were rapidly growing, nearly tripling from 2011 to 2012 despite severe inventory problems during the year. However, overall margins remained low, and the company had not yet become profitable.

Quirky faced a number of challenges. Key among these were increasing margins sufficiently so that the company would be profitable, continuing its social development model without becoming burdened by excessive overhead, and developing its supply chain to take advantage of the unique attributes of the Quirky business model rapid introduction of new products, and a compelling product story.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. How can the company achieve acceptable long-term margins?

2. Should Quirky continue to add new products at an ever-increasing rate? If so, how can it do this while retaining the flexibility and nimbleness that characterized its early development?

3. Should it bring manufacturing in-house? If so, how should it decide what it should do inhouse, and what it should continue to outsource?

4. How can Quirky address the difficulties of selling its products through third-party retailers? Should it increase its direct selling activities, and if so, how?

5. Should Quirky partner with established consumer companies? If so, what form should such a partnership take? Whom would you partner with?

2005 March May June

July

2006 January August

2007 January March May July August September October

2008 February

2009 March June September October November

2010 April December

2011 January March July August October November December

2012 January February March April June August

Source: Quirky.

Exhibit 1

Timetable: Mophie Through Quirky

Ben Kaufman starts Mophie

Kaufman flies to China to finalize production for Song Sling

Kaufman graduates from high school

Song Sling launched

Mophie wins Best of Show at MacWorld

Mophie gets venture investment

Mophie involves 30,000 MacWorld attendees in developing Bevy

Bevy launched

Mophie products distributed in 28 countries

Inc. Magazine names Kaufman #1 Entrepreneur in Under 30 Category

Mophie sold

Kluster development begins

Kaufman turns 21

Kluster launched at TED Conference

Quirky founded

Quirky.com goes live

Quirky featured in NYT Magazine

First product shipped (Split Stick)

Quirky acquires Kluster Platform

Quirky raises $6 million Series A venture funding

Products distributed through Bed Bath & Beyond

Quirky premiers on HSN

Closes $5 million Series A2 insider round

Cover of Entrepreneur Magazine

Raises $16 million in Series B round

Full store rollout in OfficeMax

Shipments begin to all Target stores

Quirky on Yahoo News front page. Quirky’s highest traffic day

Quirky moves to new 27,000 sq. ft. office

Quirky featured on CNBC

Ships 1 millionth unit

Featured in The Economist

Ships 2 millionth unit

Raises Series C: $68 million ($43 million net to company after payments to existing shareholders)

Exhibit 2

Source: Quirky Website, “Learn,” http://www.quirky.com/learn (accessed March 21, 2012). Reprinted with permission.

Exhibit 3

Growth of the Quirky Online Community

Unique visitors per month, June 2009 to December 2012

Page views, June 2009 to December 2012

Source: Based on data from Quirky.

Total registrations, May 2009 to December 2012

Total Votes, June 2009 to December 2012

Exhibit 4

Live Quirky Evaluation Meeting

Quirky held weekly meetings to review product ideas. Staff presented the ideas and moderated discussions. A live audience participated, and online members could view the proceedings by webcast and submit comments by live chat. Participants, both in person and online, voted on each idea presented.

Source: Quirky. Reprinted with permission.

Exhibiy 5

Product Pipeline, May 2009 to December 2012

Total ideas submitted

Products in “Upcoming” (completed design)

Source: Based on data from Quirky.

Products in development

Products shipping (from October 2009)

Exhibit 6

Selected Quirky Products

The wide range of Quirky’s products is illustrated by this small selection.

Pluck: a device for separating egg yolks. Price: $12.99 on Quirky.com.

Crates: a modular organizing/furniture system. Available at Office Max.

Source: Quirky. Reprinted with permission.

Pivot Power: a flexible power strip. Price: $29.99 on Quirky.com

Cordies: a device for organizing computer cords. Price: $9.99 on Quirky.com.

Exhibit 7

Sales by Product Price

The following chart shows the distribution of product sales by price, from the first sale of each product through April 2013. Prices in table are list prices, not the prices at which Quirky sells to retailers.

The largest single unit seller was Pivot Power, which accounted for 24 percent of total units sold and 37 percent of total revenue, and had a list price of $29.99. (Note that this is the standard Pivot Power product and does not include variants such as “Christmas Pivot Power” and “Pivot Power EU.”)

The highest priced product in early 2013 was Space Bar, a computer accessory that minimized desk clutter and provided additional USB ports. Space Bar had a list price of $99.99.

Total unit sales was 4,405,124. Total revenue was $28,396,657.

Source: Derived from data provided by Quirky.

Exhibit 8

Cumulative Revenue by Product

As of early 2013, Quirky’s lifetime revenues had been dominated by a relatively few products, led by Pivot Power, which accounted for 37 percent of total revenue. The top 4 products (by revenue) made up 53 percent of total revenue. This is shown in the following graph.

The y-axis is cumulative revenue expressed in percentage. The x-axis is number of products that contribute to that revenue, with data from products in descending order of sales.

Source: Derived from data provided by Quirky.

Exhibit 9

Quirky Organization Chart, Early 2013

Quirky described its organization using the following graphic:

Source: Quirky. Reprinted with permission.

Exhibit 10

Quirky Facilities in New York City

In January 2012, Quirky moved to a new state-of-the-art facility in New York City, including areas for design, conferencing, webcast product evaluation meetings, and a model shop.

Source: Quirky. Reprinted with permission.

Exhibit 11

Quirky Financials (Unaudited)

All values in thousands of dollars, except gross profit percent.

Note: due to changes in reporting format, income statement financials are provided only by major category. As a result, 2009 and 2010 cost of sales is calculated based on revenue and gross margin percent.

Source: Quirky.

All values in thousands of dollars. Balance Sheet (as of Dec. 31)

Deposits & Prepaids

Exhibit 11 (continued)

Equity

and Paid-in Capital Retained Earnings Total Shareholders’ Equity

Notes: 1) For 2009 and 2010, included in Operational Deposits and Prepaids.

Source: Quirky.

Exhibit 12

2012 Quarterly Financial Statements (Unaudited)

Note that Q3 and Q4 were impacted by inventory shortages. All values in thousands of dollars, except gross profit percent.

Statement

Operating Expenses (2)

EBITA

Notes:

1) Revenue adjustments include returns, deductions, and promotions.

2) Includes community rewards of:

a. Q1 = 171

b. Q2 = 533

c. Q3 = 432

d. Q4 = 909

Source: Quirky.

All values in thousands of dollars. Balance Sheet at

Total

Liabilities

Current Liabilities

Accounts

Shareholders’ Equity

Contributed Capital Retained Earnings (Net Income)

Source: Quirky.

Exhibit 12 (continued)

Exhibit 13

Margin Improvement: Pivot Power and Cordies

Margin increases for Pivot Power and Cordies for their early production runs are shown below. The initial production run for Pivot Power was shipped by air in order to meet retailer delivery requirements; subsequent orders were shipped via ocean container. Product unit costs for the second run were reduced by 8 percent due to increased volume. A new supplier was secured for the third production run, resulting in a 20 percent unit cost reduction, as well as a 6 percent reduction in fulfillment costs. Overall, these changes improved the margin from negative 21.4 percent in the first run, to a positive 20.6 percent within one year.

All values in dollars, except margin percent.

Source: Quirky.

Exhibit 14

Comparisons with Other Companies

Quirky R&D is based on community rewards plus internal staff costs.

Source: Public company financials compiled from financial disclosures by Scott Ransenberg, Riverwood Capital. Quirky financials provided by Quirky.