TRIBUTE

The Loss of a Leader: Rabbi Moshe Hauer, zt”l

Man of G-d: Remembering Rabbi Moshe Hauer

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

A Guiding Light for Klal Yisrael By Chief Rabbi Kalman Meir Ber

“His Life Was a Continuous Ascent” By Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

To Illuminate Rather Than Condemn: The Legacy of Rabbi Moshe Hauer By Moishe Bane

A World Mourns

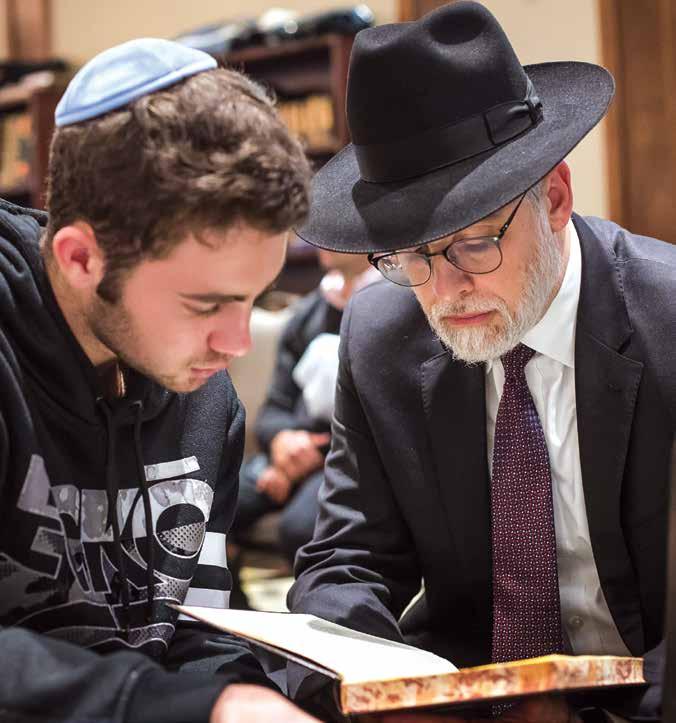

PHOTO ESSAY

Portrait of a Leader

JEWISH LAW

Weighing In: Ozempic and Jewish Law By Dr. Sharon Grossman

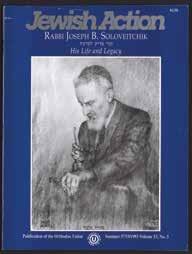

COVER STORY

Celebrating Our Fortieth Anniversary

Jewish Action Through the Years

Forty Years of Change By Jonathan Dimbert; Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein; Rabbi Menachem Genack; Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg; Nachum Segal, as told to Sandy Eller; Rabbi Gil Student; Rebbetzin Dr. Adina Shmidman; Nathan Diament; Rabbi Avraham Edelstein; Rabbi Micah Greenland; Dr. Rona Novick, as told to Sandy Eller; Rabbi Michoel Druin; Dr. Noam Wasserman; Eli Langer; Rabbi Menachem Penner; Ruchama Feuerman; Ann Diament Koffsky; Roz

Sherman, PhD; Lisa Elefant, as told to Sandy Eller; Rabbi Yehoshua Fass, as told to Tova Cohen; Hillel Fuld

BUSINESS & ECONOMICS

Crushed by the Costs: The Hidden Financial Strain of the Orthodox Middle Class By Shalom Goodman

Financial Minimalism:

What happens when you stop chasing more and focus on what really matters? By Rivka Resnik

The Cost of Community: The OU’s Bold Effort to Make Frum Life Sustainable By Tova Cohen

JEWISH MEDIA

Faces of Orthodoxy: Stories of Orthodox Jews, One Face at a Time By Alexandra Fleksher

90

JUST BETWEEN US Turning Off My Phone By Richard Simon

Jewish Action is published by the Orthodox Union • 40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006, 212.563.4000. Printed Quarterly—Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, plus Special Passover issue. ISSN No. 0447-7049. Subscription: $16.00 per year; Canada, $20.00; Overseas, $60.00. Periodical’s postage paid at New York, NY, and additional offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Jewish Action, 40 Rector Street, New York, NY 10006. Jewish Action seeks to provide a forum for a diversity of legitimate opinions within the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism. Therefore, opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or opinion of the Orthodox Union.

KOSHERKOPY

Kosher Rx: Navigating the Kashrus of Medications and Vitamins

LEGAL-EASE

What’s the Truth about . . . Waiting Between Meat and Dairy? By Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

THE CHEF’S TABLE Winner Winter Weeknight Dinner! By Naomi Ross

NEW FROM OU PRESS

The Concise Code of Jewish Law: A Guide to Daily Prayer and Religious Observance (Revised Edition) By Rabbi Gersion Appel; revised edition edited by Rabbi Daniel Goldstein

BOOKS

Ben Yeshiva: Pathway of Aliyah By Rabbi Ahron Lopiansky Reviewed by Rabbi Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer

Kotzk: The Rebbe, The Message, The Legacy By Yisroel Besser

Reviewed by Yehuda Geberer

LASTING IMPRESSIONS

Life Lessons from My Stint as Junior Gabbai By Rabbi Akiva Males

Cover Design: Bacio Design & Marketing, Inc.

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION

jewishaction.com

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION jewishaction.com

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

I just read Adina Peck’s article in the summer 2025 issue, “Yes, There Are Jews in Charlotte: Living Jewishly in the American South.” And a great article it was! It was well written and well documented.

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Associate Editor Sarah Weiner

Assistant Editor Sara Olson

Associate Digital Editor Rachelly Eisenberger

Literary Editor Emeritus Matis Greenblatt

Rabbinic Advisor

Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz

Book Editor Rabbi Gil Student

Book Editor

And I learned much, even though, having lived here for thirty years, I thought I knew all there was to know about Jewish Charlotte.

Elias Roochvarg

Cantor Emeritus

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Hillel Goldberg

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Moishe Bane • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg

Editorial Committee

David Olivestone • Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Temple Israel of Charlotte

Charlotte, North Carolina

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

Gerald M. Schreck • Rabbi Gil Student

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Moishe Bane • Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

David Olivestone • Gerald M. Schreck • Dr. Rosalyn Sherman

Design 14Minds

Rebbetzin Dr. Adina Shmidman • Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Advertising Sales

Thank you for the very wise article by Rabbi Yisrael Motzen (“No Labels, No Limits,” summer 2025).

Copy Editor Hindy Mandel

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Design

Subscriptions 212.613.8140

Bacio Design & Marketing, Inc.

ORTHODOX UNION

Advertising Sales

Rabbi Motzen teaches us that success doesn’t depend on someone’s talents, intelligence, strength, riches or anything else. It depends on emunah—the pure and simple faith in Hashem—which brings one to see the world in its proper light.

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

President Mark (Moishe) Bane

Chairman of the Board

Howard Tzvi Friedman

ORTHODOX UNION

Vice Chairman of the Board Mordecai D. Katz

President Mitchel R. Aeder

Chairman, Board of Governors Henry I. Rothman

Chairman, Board of Directors Yehuda Neuberger

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Gerald M. Schreck

Vice Chairman, Board of Directors Morris Smith

Executive Vice President/Chief Professional Officer Allen I. Fagin

Naftali Rubin

Jerusalem, Israel

Chief Institutional Advancement Officer Arnold Gerson

Chairman, Board of Governors Henry Orlinsky

Senior Managing Director Rabbi Steven Weil

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Jerry Wolasky

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Executive Vice President Rabbi Moshe Hauer, zt”l

In response to Yosef Lindell’s thoughtful article, “Between Nusach and Niggun: The Chazzan’s Evolving Role” (fall 2025), I would like to share an important perspective I heard a number of years ago from Rabbi Yaakov Hopfer, rav of Shearith Israel Congregation in Baltimore, when he addressed ba’alei tefillah in the community. What follows is my summary of his words, as I understood them.

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer Shlomo Schwartz

Executive Vice President & Chief Operating Officer

Rabbi Josh Joseph, Ed.D.

Chief Human Resources Officer

Rabbi Lenny Bessler

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Chief Information Officer Samuel Davidovics

Managing Director, Communal Engagement

Chief Innovation Officer

Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

Rabbi Dave Felsenthal

Director, Jewish Media, Publications and Editorial Communications

Rabbi Gil Student

Director of Marketing and Communications Gary Magder

Jewish Action Committee

Jewish Action Committee

Dr. Rosalyn Sherman, Chair

Gerald M. Schreck, Chairman

Gerald M. Schreck, Co-Chair

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

©Copyright 2018 by the Orthodox Union Eleven Broadway, New York, NY 10004

©Copyright 2025 by the Orthodox Union

40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Facebook: Jewish Action Magazine

Instagram: jewishaction_magazine

Twitter: Jewish_Action Linkedln: Jewish Action

There is a widespread misconception about the role of the shaliach tzibbur. Many think his primary function is to inspire the kehillah. While that is certainly important, he has a more critical role to play: he is speaking directly to Hashem on behalf of His people. The central focus of the shaliach tzibbur is Chazaras Hashatz, Kedushah and other tefillos established to ensure that those who are not fluent in davening could still fulfill their obligation to daven. That was the very reason the role of shaliach tzibbur was instituted.

Rabbi Hopfer went on to explain: the role extends even to those who cannot be present in shul, the am shebesados [those who worked in the fields and were often far from the town]. These individuals were considered anusim—prevented from attending minyan through no fault of their own—and yet the shaliach tzibbur fulfills

their obligation nonetheless. One might ask: if they are not present to hear him daven, how can he fulfill this role for them? The answer lies in the principle of shlucho shel adam kemoso (a person’s emissary is like himself). Just as when the leader of a community goes before a king and speaks as the representative of the people who sent him, so too the shaliach tzibbur speaks before the Ribbono Shel Olam on behalf of his kehillah. Thus, the shaliach tzibbur is their emissary, their mouthpiece.

This, Rabbi Hopfer explained, means the shaliach tzibbur must have a profound sense of rachmanus (compassion) for his people. He must daven with the awareness of the struggles in his community, families crushed by staggering tuition burdens, people enduring financial difficulties that strain shalom bayis, men and women confronting health challenges, children suffering with learning or focusing issues, young men and women still waiting for shidduchim

A shaliach tzibbur who feels this collective pain and brings it before Hashem will daven in an entirely different way. As the tefillah says: “Heyei im pifiyos shluchei amcha Bais Yisrael—Be with the mouths of the emissaries of Your people, the House of Israel.”

The shaliach tzibbur

One patented system. Endless configurations.

• NEW item – Available in Black or White

• Modular & Expandable – Any configuration you need

• 4-Plata Starter Set – Expandable up to 20 Platas

• High-Tech Heating Element in each Plata (270°F / 130°C)

• Easy-to-Clean Tempered Glass Surface

• Easy to Store — stackable

• Lightweight

• Travel-Friendly

• Take one Plata on the go – perfect for travel

• Great for Home, Catering, Bu ets, Kallah Gifts & more

• Approved by Mishmeret HaShabbat of Bnei Brak

of Klal Yisrael. When a person truly feels the pain of others and cries out to Hashem from that place, those tefillos pierce the heavens. But alongside the pain, the shaliach tzibbur must also feel the goodness, the beauty and the nobility of our people. That combination, both empathy for suffering together with gratitude for the blessings of Klal Yisrael, creates a tefillah filled with authenticity, love and compassion.

May we all be zocheh to approach tefillah in this spirit and, through such heartfelt davening, bring yeshuos and nechamos to our communities and to all of Klal Yisrael.

Yaakov Jake Goldstein Baltimore, Maryland

BUILDING COMMUNITIES FROM THE GROUND UP

I read with great interest Judy Gruen’s “Putting Springfield, New Jersey, on the Map: Ben Hoffer” (fall 2025) about the flourishing community of Springfield, New Jersey, led so dynamically by Rabbi Chaim

shul building as it was being constructed in the early 1970s. Rabbi Turner served as the rabbi and then rabbi emeritus of the congregation from 1973 until his passing in 1996. He was followed by Rabbi Alan J. Yuter, who led the congregation from 1987 until 2002. I recall speaking at Rabbi Turner’s funeral, which took place in the shul, where I focused on his total devotion and deep love for the shul, its members and the greater Springfield community. I am certain that he would take great pride to see how this fledgling community has become a makom Torah and avodah, with families continually moving in and enjoying all that the shul and community have to offer. His vision for the future has come true!

Bonnie Frankel Woodmere, New York

While it was great to see Phoenix, Arizona, featured in Sandy Eller’s “Warmth Beyond Sunshine in Phoenix: Shaun and Gary Tuch” in the last issue, the article seemed to present a very narrow narrative. The Orthodox community in Phoenix, founded in 1965, possibly earlier, has been flourishing. There are over

seven Orthodox shuls of different types within a oneand-a-half-mile radius in Phoenix and at least three in Scottsdale, which is twenty minutes away, as well as numerous Chabad centers in the Phoenix metro area. Within nine miles of each other, there are four kosher grocery stores as well as expanded kosher sections in Safeway and Fry’s (Kroger). Trader Joe’s and Costco carry kosher meat, and there are some independent sellers of frozen bulk meat.

Restaurants? Your article stated that there was one. Within a few miles of each other there are two dairy and two meat restaurants in Phoenix. In Scottsdale, there are two wonderful meat restaurants and an excellent dairy restaurant.

Schools? There are Orthodox schools including Chabad schools for preschool through eighth grade. There are also a number of single-gender high schools and a co-ed high school. Numerous youth organizations, for all ages, are available as well.

Having lived in places where I had to travel forty-five minutes to an hour to buy kosher food or go to a kosher restaurant, I find that Phoenix is blessed with plentiful opportunities to purchase kosher food or dine out.

Additionally, Phoenix, with its low property taxes compared with other cities, can be affordable.

In short, Phoenix is filled with Yiddishkeit.

Ellen Nechama Poor Phoenix, Arizona

Thank you for presenting the inspiring stories of Orthodox Jewish communities building and rebuilding, including Cincinnati, Ohio (“How a Shul Rewrote Its Story: Yosef Kirschner,” by Judy Gruen). Beneath the happy endings are the senior board members, whose steadfast efforts preserved the institutions and who then focused on working with the next generation to address their evolving needs and preferences.

Dr. Leonard J. Horwitz Cincinnati, Ohio, and Deerfield Beach, Florida

Transliterations in the magazine are based on Sephardic pronunciation, unless an author is known to use Ashkenazic pronunciation. Thus, the inconsistencies in transliterations in the magazine are due to authors’ or interviewees’ preferences.

This magazine contains divrei Torah and should therefore be disposed of respectfully by either double-wrapping prior to disposal or placing in a recycling bin.

This past Shemini Atzeret, the OU family—and indeed all of Klal Yisrael—was left with a void that cannot be measured, with the passing of our beloved Executive Vice President, Rabbi Moshe Hauer, zt”l. For nearly six years, he carried the OU with a steady hand and a listening heart, guiding with wisdom rooted in Torah, integrity and an abiding love for Klal Yisrael. In shul, in the office, in the public square— wherever he went—he brought warmth, clarity and a sense of sacred purpose. His life was a living lesson in devotion, humility and care. May his memory forever be a blessing and a light to guide us forward.

In the pages that follow, we offer reflections from colleagues and friends who knew him best. A more extensive tribute will appear in a special edition of Jewish Action.

Rabbi Moshe Hauer, zt”l

, with OU Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

Just a few short months ago, at the OU’s Professional Leadership Retreat in September 2025, Rabbi Moshe Hauer, zt”l, shared something that Rabbi Berel Wein, zt”l, often recounted about the legendary Rabbi Alexander Rosenberg, zt”l,—Rebbetzin Mindi Hauer’s grandfather—who preceded Rabbi Wein as the rabbinic administrator of OU Kosher from 1950 to 1972.

A wide array of people would approach Rabbi Rosenberg with a range of ideas and plans. True to the extraordinary integrity he was known to exemplify, he would listen carefully until they finished, pause, look at them and ask, “Un vos zogt G-tt?—And what does G-d say?”

His daughter (Rabbi Hauer’s mother-inlaw) related that this was her father’s guiding principle—his mantra: “What would G-d say?”

Today we often soften that question, noted Rabbi Hauer. Instead we ask, “What does the Torah say?”

But the Gemara uses the terminology, “Rachmana amar—the Merciful One said.” We are meant to hear G-d’s voice, to live with an awareness of Hashem Yitbarach, and to help raise that awareness in the world. We are defined as a nation of believers—people who believe in G-d and take pride in our belief.

This question encapsulated Rabbi Hauer’s essence. In his erev Shabbat Shuvah message (Sept. 26, 2025), he wrote: “Let’s speak about G-d. Not just now. Let’s consistently speak much more about G-d. Not just about religious behavior and belonging, but about belief, the alef and bet of religious life—emunah and bitachon.”

In my previous Jewish Action articles, we’ve discussed the three B’s of religious engagement:

Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph is executive vice president/ chief operating officer of the Orthodox Union.

belief, behavior, and belonging. (Actually, there’s a fourth—becoming—which perhaps we will discuss in the future.) My focus had been on the last of these, belonging. But privately, Rabbi Hauer and I often bemoaned our community’s lack of connection to Hashem—a concern that increasingly became the focus of his public message in his final days.

In one of our earliest moments of sharing Torah, during a troubling and difficult time for the world as the pandemic took hold, Rabbi Hauer shared a thought that has shaped my perspective time and time again:

“Mi ha’ish he’chafetz chayim, ohev yamim lirot tov? Netzor leshoncha mei’ra, usefatecha midaber mirmah—Who is the man who desires life, who loves days to see good? Guard your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking deceit” (Tehillim 34:13–14).

When encountering this quote, we usually focus on the message of not speaking lashon hara. But Rabbi Hauer saw more than that. He would often say: “Don’t speak badly about Jews! Don’t even think badly about them!” I asked him, “How?” And he answered, “Stop skipping over the middle phrase: “ohev yamim lirot tov—who loves days to see good.”

That is what he would do: he would put on his G-dly lenses, his ahavah-colored lenses, and see people and situations with love. Through that love, he saw the good.

With this devar Torah, he not only shaped our perspective in a time of distress but also offered a way of life—a Torat Chaim—to guide all of our days.

Rabbi Hauer used this mindset and framework to believe in everyone’s potential, even those whom others didn’t believe in—or those who didn’t believe in themselves. He believed in the power of the Jewish people. He believed in his family. He

believed in the OU. He believed in us. He believed in me. Ultimately he believed in shalom, in people getting along.

Our tradition offers us a beautiful story to illustrate the idea of believing in each other. The Torah states that Noach went into the ark “mipnei mei hamabul—due to the waters of the Flood” (Bereishit 7:7). Rashi comments: “Af Noach miketanei amanah hayah, ma’amin ve’eino ma’amin sheyavo hamabul—Noach, too, was one of those of little faith; he believed but didn’t believe [fully] that the Flood would actually come.” That is why Noach did not enter the Ark until he saw with his own eyes that the waters had started to fall.

But how could Noach, the greatest tzaddik of his generation, have even the smallest doubt that the word of G-d would be fulfilled? Didn’t he spend 120 years listening to Hashem?

Rabbi Yitzchak of Vorki presents a remarkable reimagination of Rashi’s approach. He suggests we punctuate Rashi’s comment differently: “Af Noach miketanei amanah hayah ma’amin, ve’eino ma’amin sheyavo hamabul—Even Noach believed in those of little faith, and therefore he did not believe the Flood would come.” He trusted that they would repent and return to Hashem, and Hashem would halt the destruction of humankind. In other words, Noach believed in all of humanity, in the potential of each and every person.

Interpreting for the Good: Noach’s Legacy

It’s important to point out another aspect of the story of Noach, as the goodness of Noach himself is often debated. “Eileh toledot Noach; Noach ish tzaddik tamim hayah b’dorotav—These are the descendants of Noach; Noach was a righteous man, perfect in his generation” (Bereishit 6:9). Rashi notes that some of our rabbis interpret “in his generation” as praise—all the more so would Noach have been righteous had he lived among the righteous. Others interpret it as criticism—only relative to his generation was he righteous; had Noach lived in Avraham’s generation, he would not have been considered upright.

Rabbi Hauer used this mindset and framework to believe in everyone’s potential, even those whom others didn’t believe in—or those who didn’t believe in themselves.

Rabbi Avraham Rivlin of Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh teaches: Anyone who doesn’t interpret Noach favorably isn’t from our sages! Because “talmidei chachamim marbim shalom ba’olam— Torah scholars increase peace in the world.”

It’s time we put on Rabbi Hauer’s Hashemcolored lenses, his ahavah-colored lenses, and see the world as he did.

I truly think of Rabbi Hauer as a man of G-d. As we know, he traveled frequently—in taxis, Ubers and other vehicles. Shortly before he passed away, he shared with us that although he always said thank

you to these drivers, more recently he started to say “G-d bless you.” The reactions he would get were priceless, with the drivers genuinely appreciating his invoking G-d’s blessings.

This is just one example of how, wherever he went, people saw him as a man of G-d—reflected in his middot and his humility: “veha’ish Moshe anav me’od mikol ha’adam ” In everything he did, whenever he spoke and with whomever he spoke, he had in his mind the gemara in Yoma 86: “Ve’ahavta et Hashem Elokecha: she’yehei Shem Shamayim mitahev al yadcha—And you shall love Hashem your G-d: that the name of Heaven should become beloved through you.” For so many—those who knew Rabbi Hauer well and those who met him just once—Hashem became beloved through him.

Developing a “Hashem-First” Mindset

I often find that my first reaction—especially in interactions with others—is to think about people:

• “What will they think?”

• “How will they take this?”

• “Why is he being nice?”

• “Why is she speaking hurtfully?”

In all of those situations, I could instead think first about Hashem:

• “What will Hashem think?”

• “How will Hashem take this?”

• “Why is Hashem giving me a nice word through this person?”

• “What message is Hashem sending me through this person?”

Part of developing a “Hashem-first” mindset requires us to look for the love of Klal Yisrael through Hashem’s eyes. This is how Rabbi Hauer lived each day.

Rabbi Hauer’s legacy calls us to cultivate a “Hashem-first” mindset in all of our interactions. This means putting on our ahavah-colored glasses to see the good in others; believing in everyone’s potential, even when others do not; increasing peace in the world through our actions; and making the name of Heaven beloved through our conduct. May his memory be a blessing, and may we continue to ask ourselves: “Un vos zogt G-tt?—And what does G-d say?”

By Chief Rabbi Kalman Meir Ber

When Rabbi Yochanan passed away, Rabbi Elazar arose and eulogized him, saying: “This is as difficult a day for Israel as when the sun sets at midday” (Mo’ed Katan 25b). Rabbi Yochanan was 120 years old when he left this world. He was certainly not a young man. Nevertheless, Rabbi Elazar described his passing as a “difficult day for Israel,” a day when the sun set prematurely—at noon—because Rabbi Yochanan was still at the height of his leadership. He illuminated the eyes of Israel. When he died, it was as if the sun had set at midday, at the very peak of its brilliance. His age was irrelevant.

Rabbi Kalman Meir Ber is the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel. This article is an unreviewed translation of Rabbi Ber’s eulogy delivered Friday, October 17, 2025 (Chaf Hei Tishrei, 5786). The sources are provided by the editor. The original eulogy, in Hebrew, can be found here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMgZ5U51QtE.

OU Israel’s

There was a great light—the light of Rabbi Moshe Hauer, a light that shone like the midday sun. Rabbi Hauer was a real leader. He knew how to navigate, to guide, to unite and to consistently act for the sake of Klal Yisrael. Rabbi Hauer did not think of himself; he thought only of what was best for the Jewish people at any given moment.

Truly, it is a difficult day for Israel.

The Gemara (Berachot 28a) relates that when Rabban Gamliel was removed from the position of nasi (head of the Sanhedrin), it was due to Rabbi Yehoshua (the details are not relevant here). Later, Rabban Gamliel went to reconcile with him and said, “It is evident from the sooty walls of your home that you are a blacksmith.” (Rabban Gamliel had not been aware of the financial hardship that compelled Rabbi Yehoshua to engage in that trade.)

Rabbi Yehoshua replied with two statements: “Woe to the ship whose captain you are; woe to the generation which you serve as a parnas (leader).” What did he mean? The words of the sages always require study. A leader must possess two traits. First, he must be like a ship’s captain. A captain need not know each passenger personally; he must know the direction—where to steer the vessel, where to take the people. But a leader must also be a parnas—from the word parnasah [someone responsible for everyone’s sustenance and livelihood]. It is not enough to see the collective; one must also see each individual—to understand that the flock is composed of individuals, each with his own needs.1

Rabbi Moshe Hauer exemplified both of these traits. He understood the nature of the Jewish people—he knew how to unite them, to sense their

needs, to spread Torah and chesed, to unify people and to revive them. Someone told me, “When I was sick, I felt as though Rabbi Hauer took my illness upon himself—it became much easier for me.” Every sick person, every poor person, every needy soul—he was a parnas to each one. That is true leadership. And when such leadership is extinguished, it is like the sun setting at midday.

It is truly astonishing. Looking around the Jewish world today, we see how many divisions there are among the people and how few are truly “accepted by all their brethren”—right and left, in Israel and abroad. I ask myself, how did Rabbi Moshe Hauer merit such universal respect and affection? He achieved what few ever do—the love and esteem of all sectors.

Perhaps it is as the verse says about Mordechai HaYehudi: “Gadol laYehudim ve’ratzui l’rov echav He was great among the Jews and accepted by most of his brethren” (Megillat Esther 10:3). Before he was “ratzui—accepted,” he was first “gadol—great.”

What does “great” mean? In Torah and throughout Tanach, gadol always denotes one who cares for others. “Moshe grew up—vayigdal Moshe—and went out to see the suffering of his brothers” (Shemot 2:11). True greatness is in seeing another’s pain.

A gadol is one who gives. Likewise, the Shunammite woman is referred to as an “ishah gedolah—a great woman” (II Melachim 4:8). What made her great? She cared for Elisha’s needs, made him a room, looked after him. She concerned herself with others—and that is what made her great. Her greatness lay in her generosity, in her hospitality.

So too Mordechai HaYehudi was “gadol—great” because he cared for every Jew, saw the Jewish spark within every person. Because of that, he was accepted by most of his brethren.

Rabbi Hauer was the very embodiment of vayigdal Moshe—true greatness. For him, the only thing that mattered was the welfare of the individual and the needs of the collective. How to care for each person. What action to take. How to give—whether to the community as a whole or to each individual in need.

His universal acceptance should therefore come as no surprise. There is so much for us to learn from him. His constant caring explains why he was ratzui l’rov echav—beloved by Jews from all walks of life.

I have to mention one point that I think is very important. The Gemara in Sanhedrin (105b) says, “Whoever is lazy in eulogizing a sage deserves to be buried alive.” It derives this from Yehoshua bin Nun: “He was buried north of Mount Ga’ash” (Yehoshua 24:30). The Gemara understands this to mean that the mountain “erupted,” as if to swallow the Jewish people because they were negligent in his eulogy. Why were they negligent? Yehoshua was

a great leader—why would the people not properly eulogize him? Actually, they did not fail in their duty. Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin explains that there are two types of negligence: One is neglecting time for Torah; the other is failing to reach depth in study. Such a lack is also a form of neglect.2

Of course there were eulogies for Yehoshua. But the Jewish people did not truly plumb the depths of who he was. They all spoke of Yehoshua the chief of staff, Yehoshua the strategist, Yehoshua the leader of Am Yisrael, the great warrior and all his achievements. But they failed to see the real Yehoshua—the source of all his success. “Yehoshua bin Nun, a lad, would not depart from the tent” (Shemot 33:11). He was constantly immersed in the depths of Torah. Everything he did flowed from a Torah-based outlook, from his role as the personal attendant of Moshe Rabbeinu. He never departed from the tent of Torah.

This was where the Jewish people failed. They did not perceive Yehoshua bin Nun’s ruach hakodesh. 3 And incidentally, this was also the reason that Shmuel HaNavi’s prophecy ceased.

For a eulogy is meant to be more than remembrance—it is the takeaway, the lesson to be learned. Rabbi Hauer was a tremendous talmid chacham who could discuss any sugya, any subject in the Torah. It was through the power of Torah—its outlook on life, the world of Torah—that he achieved everything he did. We must not take a superficial view of who he was. We must look deeper, at the inner dimension—at the depth of Torah. “The lad—the servant—would not depart

from the tent.” At all times, even while on his feet and going about his work, Rabbi Hauer remained focused and toiling in Torah. And from this effort, he reached all his achievements.

The Gemara says that a person’s place and time of death are decreed at birth (Shabbat 156a). How fitting that he passed on Simchat Torah—the day when all Israel unites around the Torah. Unity, yes—but unity through Torah. He sought unity but without compromising Torah. As Rabbi Avi Berman [executive director of OU Israel] told me today, “He wanted unity but never at the expense of a single value of Torah.”

That was Rav Moshe Hauer. Amid all these exceptional abilities, he attained the world of Torah.

We offer a prayer to the Creator: We send you a faithful shaliach tzibbur. Rabbi Hauer, you were here with us, and you looked after Klal Yisrael at all times. You looked after everyone. May you continue to be a Heavenly advocate for the Jewish people.

Notes

1. See Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, Ein Ayah, Berachot 4:22.

2. Nefesh HaChaim 4:2.

3. See Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, Ein Ayah, Shabbat 13:6.

By Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

It was well over forty years ago, long before I became the rabbi of Shomrei Emunah in Baltimore, that my wife, Chavi, and I had the zechus to host Rabbi Moshe Hauer, Rabbi Moshe Yisrael ben Binyamin, zt”l, for Shabbos meals, sometimes for an entire Shabbos day, when he was a young student at Yeshivas Ner Yisroel. Back then, we knew him as Moishe—a brilliant young man, already recognized for his

excellence in Talmudic study—but even then, there was something about him that made it clear he was destined for a life of extraordinary impact. In those early years, I saw a young bachur with a presence unlike others. Yeshivah bachurim who

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb is executive vice president, emeritus of the Orthodox Union.

Even at that young age, there was an awareness, a sensitivity, a kind of inner depth that suggested he would not only learn but grow in ways that would touch many lives.

would come to our home for Shabbos were often lively, sometimes unfocused, but Rabbi Hauer stood apart. He engaged in conversation, in Torah discussion or simply in observing the world around him with a seriousness and thoughtfulness beyond his years. His intellectual curiosity was vivid, but it was paired with a natural integrity, a careful honesty and a humility that commanded respect without effort. Even at that young age, there was an awareness, a sensitivity, a kind of inner depth that suggested he would not only learn but grow in ways that would touch many lives.

Over the decades, what I saw in those first encounters developed into something astonishing. The young Talmud scholar became a man of formidable erudition. His curiosity blossomed into mastery, and that mastery into wisdom, all nurtured by a relentless commitment to truth. It was not merely knowledge that grew within him, but a profound sense of responsibility, of leadership and of care for others. Every step of his life reflected a growth that was consistent, steady and transformative.

I watched him grow from a brilliant student into a rabbi in the community, then a rabbi in many communities, shaping and guiding countless individuals. Finally, he became executive vice president of the Orthodox Union, and even in that position, he continued to grow. From week to week and month to month, he expanded his influence, refining his voice, asserting his intellect, and deepening his understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing the Jewish people. He reached far beyond his immediate circles, engaging with the broad spectrum of the Jewish world, extending even to interactions with non-Orthodox Jews and leaders in diverse social and political arenas.

His growth was not only intellectual. The young man who listened attentively at our Shabbos table

evolved into a man of profound empathy and care. He could hear the words of others and understand their needs, their struggles and their potential. His courtesy, once noticeable in small gestures, became a vast expression of love for his fellow Jews. His love for the Jewish people—ahavas Yisrael—expanded beyond his community, beyond Baltimore, beyond Orthodox circles, touching Jews everywhere.

I think of him in moments of courage as well, standing firm in truth even when it was difficult. One story that comes to mind is the memorial for the assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, when Rabbi Hauer did not hesitate to participate fully, representing Orthodox Jewry even when it might have been uncomfortable or controversial. He understood that leadership sometimes requires courage, that emes—the uncompromising pursuit of truth—is not only a personal virtue but a communal responsibility.

And yet, through all of this, it was growth that defined him most of all. Not just growth in knowledge or position, but growth in character, in depth, in love for humanity and commitment to the Divine. Each stage of his life built upon the last, transforming early potential into realized greatness. The young student who first came to our home was already remarkable; the man who stood as a leader, a thinker and a shepherd for his generation became extraordinary.

With Rabbi Dr. Tzvi

Even in the final weeks of his life, he continued to grow. His weekly writings became more profound, more incisive, more far-reaching, touching issues and hearts far beyond what he had done before. His growth was never static; it was a living, evolving testament to his inner strength and commitment.

Rabbi Moshe Hauer was, in the truest sense, a person whose life exemplified the extraordinary

potential of growth, the unfolding of talent and character over a lifetime devoted to Torah, truth and the Jewish people. We are left to mourn a loss that cannot be measured, to grieve the absence of a leader whose life was a continuous ascent, whose impact was ever-expanding, and whose spirit will continue to guide and inspire all of us who were privileged to know him.

By Moishe Bane

Ihave not yet found words to convey the depth of my personal bereavement with the passing of Rabbi Moshe Hauer. I can, however, more readily reflect upon and discern the gifts he bestowed upon Klal Yisrael.

Much has already been said and written about the tragic and immeasurable loss our community has endured, not least being Rabbi Hauer’s rare constellation of personal virtues that defined him. Yet to me, his most significant and enduring communal legacy lies in the way his extraordinary success in public life resolved one of Orthodox leadership’s most persistent dilemmas: how to defend Torah values with vigor and conviction while remaining faithful to Torah’s call for love and respect.

Experience teaches that casting stones, whether literal or figurative, at those who espouse offensive ideas rarely changes their hearts or minds. On the contrary, such gestures tend only to deepen resistance. The true aim of public condemnation and denigration is seldom reform but rather to sway the uncommitted and fortify the convictions of those already aligned—not to change the views of adversaries but rather to signal to one’s own community that the positions or behavior being attacked are beyond the bounds of consideration.

This strategy of militant contentiousness may at times be justified as necessary for the preservation of Torah Judaism. This is particularly true when confronting deviant views that include elements that may appear persuasive to the unguarded ear. Yet, Torah values themselves call us to speak with love and understanding, and to engage one another with dignity and respect. Moreover, those who assail theological or political adversaries through disparagement and vilification risk appearing sanctimonious and vitriolic, often alienating those who might otherwise sympathize with their position.

On the other hand, those who approach antagonists with warmth and camaraderie risk inadvertently conferring legitimacy upon indefensible ideas or conduct that ought to remain beyond the pale.

Rabbi Hauer revealed this supposed paradox to be illusory. He resolved this enduring tension for communal leaders by illustrating that principled and unyielding advocacy and sincere warmth and respect are not antithetical virtues, but complementary expressions of Torah integrity.

I accompanied Rabbi Hauer through countless meetings, conferences and conversations with those holding views we vehemently opposed. He composed hundreds of letters, essays and articles championing authentic Torah values at moments when those values were under challenge. At times, he also entered the fray of controversies within Orthodoxy itself, articulating his views with clarity and conviction.

Never once, however, did his words descend into disparagement, nor his tone into vilification. He would voice conviction with the quiet strength of humility. He listened attentively and would seek to understand the reasoning behind positions he knew were misguided. And he would respond firmly but never convey self-righteousness. Adversaries were transformed into friends, and Torah Judaism earned the respect of even its harshest detractors.

Simultaneously, his engaging and respectful manner with those asserting diametrically opposing views was never mistaken by his supporters for compromise or even modest endorsement of the views he unequivocally rejected. Those in the camp he represented, who shared his convictions, understood that Rabbi Hauer’s graciousness toward others was not a softening of principle but an expression of his ahavas Yisrael. He harbored a genuine love for every Jew, untouched by how fallacious or offensive their religious or political views, or

Experience teaches that casting stones, whether literal or figurative, at those who espouse offensive ideas rarely changes their hearts or minds.

even conduct, might have been. Even his more combative allies and their supporters never doubted Rabbi Hauer’s passion or his unwavering fidelity to Torah-true values.

In shaping the Orthodox Union’s institutional culture, Rabbi Hauer would often invoke a teaching of the Chafetz Chaim: that the most powerful refutation of error is not condemnation and denigration, but the clear and consistent example of the right path. When an organization challenges the practices of other movements or institutions, there is a tendency to denounce their flaws and failures. Rabbi Hauer, though acknowledging how difficult restraint can be, consistently urged the OU to act otherwise. Human nature often falls short of the ideal, but this ethic has become a guiding standard at the OU.

In an era of increasingly destructive polarization, Rabbi Hauer’s legacy offers a desperately needed model: that we can hold firm to Torah truth while treating every person with dignity, that we can unequivocally reject ideas without rejecting people, and that the most compelling defense of our values is not the force of condemnation but the integrity of our conduct.

May we find within ourselves the passion, courage and ahavas Yisrael to make Rabbi Hauer’s example the standard by which we guide both our personal lives and our communities.

A true bridge-builder, Rabbi Hauer was admired across the Jewish world and beyond. Below is a selection of excerpts from the condolence letters we received.

Letter of condolence from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), signed by Archbishop Timothy P. Broglio, president, and Bishop Joseph Bambera, chair of the Committee of Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs

Dear Mr Aeder and Rabbi Joseph,

And to all of my dear friends at the OU - to all board members, staff, and employees,

I write to you in a state of shock and deep sadness on hearing the devastating news of the passing of Rabbi Moshe Hauer, of blessed memory

I got to know him as a deeply compassionate, thoughtful, and visionary leader, who profoundly impacted American and world Jewry In every interaction with him, I was always struck by his graciousness his profound yiras Shamayim Every gesture thought and word was saturated with the light and gentleness of Torah that he personified - a Torah of darchei noam and shalom a Torah that reflected a deep sense of achrayus personal responsibility for Am Yisrael

Statement by Agudath Israel of America, noting the kiddush Hashem Rabbi Hauer created in all his encounters with the outside world and the unity within the Jewish world that he always sought to promote

Rabbi Hauer’s moral and spiritual qualities were matched by his remarkable strategic and leadership abilities He was a person of tremendous capability, vision, and depthaccompanied by tremendous generosity of spirit, always seeking to encourage others and to champion the dignity and honor of Heaven

Rabbi Hauer’s passing is a terrible loss and great blow for Am Yisrael

In his letter to the OU, Rabbi Dr. Warren Goldstein, chief rabbi of South Africa, calls Rabbi Hauer’s passing a “great blow for Am Yisrael.”

On behalf of the South African Jewish community, I would like to extend my deepest condolences to his mother Mrs Hauer, Rebbetzin Mindi and their children and grandchildren, to all who knew and worked with him

On behalf of our community, we stand with you in sorrow at this time and join with you in paying tribute to a truly great leader

With blessings,

World Mizrachi deeply mourns the sudden and tragic passing of Rabbi Moshe Hauer zt”l

Executive Vice President of the OU.

A gentle statesman of great stature and deep conviction, he led with empathy, love and wisdom. He was a masterful talmid chacham, whose authoritative voice of Torah, chessed and faith made a deep impact throughout Klal Yisrael. He was a proud advocate for Eretz Yisrael, Am Yisrael and Torat Yisrael, who knew how to inspire Torah values through his exemplary teaching, mentoring and personal values.

He was a cherished friend of the Mizrachi movement and a prominent leader of the Orthodox Israel Coalition, where we will miss his guiding presence and counsel.

We send our deepest condolences to Rebbetzin Hauer, his dear family, and everyone at the OU.

IN MEMORIAM: Remembering my chavruta: Rabbi Moshe Hauer, z”l

By Rabbi Rick Jacobs, President, Union for Reform Judaism

Published by EJP October 16, 2025

Earlier this week on Simchat Torah, we read the Torah’s final description of the biblical Moshe’s life of inspired leadership: “There never arose another one like Moshe” (Deuteronomy 34:10).

These words carry poignant resonance as our Jewish community mourns the sudden death of our beloved sage, Rabbi Moshe Hauer, z”l. Many Jewish leaders talk about the need for Jewish unity during this time of intense polarization, but Rabbi Hauer actually built Jewish unity. Since he became the leader of the Orthodox Union, Rabbi Hauer became my friend and trusted colleague — even while also an occasional sparring partner.

A few years back, Rabbi Hauer sent me a marked-up copy of a statement I had published. My words were covered with his voluminous comments in red ink. He took issue with pretty much every point I had made. Rather than just thanking him for “sharing his thoughts,” I asked if we could sit and discuss his rather extensive rebuttal.

Rabbi Hauer’s relationships extended throughout the Jewish world. Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, published an article entitled, “Remembering my chavruta: Rabbi Moshe Hauer, z”l,” in eJewishPhilanthropy. On social media, Sheila Katz noted that despite being “an unlikely duo”— she, “a Reform, Jewish progressive woman,” and Rabbi Hauer, “an Orthodox, male rabbi”—they came “together to advocate against antisemitism, to promote safety in Israel, and for the return of the hostages.”

How could I not be impressed by the seriousness with which he debated my views about the latest news from Israel? With his characteristic humility, he took me to task, never once raising his voice or dismissing my deeply held convictions. As consummate students of Torah, our session felt like a chavruta, an intense one-on-one learning session with a wise colleague. I thanked him for his thoughtful critique.

Months later, Rabbi Hauer shared this beautiful characterization of our discussions: “We are an odd chavruta: a Reform and an Orthodox rabbi, and we are unlikely to ever see eye-to-eye either on issues of religion and state in Israel or on matters of Jewish law and practice. Yet we can, and have, worked together as brothers committed to the wellbeing of our beloved Jewish people and State of Israel.”

Yes, we disagreed on many (if not most) things, but we also shared many commitments, including standing up for the safety of our people and our Jewish homeland. Last year, Rabbi Hauer and I were both at a planning meeting for an upcoming communal event one year into the Gaza War. Each person advocated for which important messages should be conveyed.

After listening to many wise and appropriate suggestions, including the deep solidarity we Diaspora Jews continue to share with our Israeli siblings, I said: “But if no one raises the suffering of the innocent Palestinians in Gaza, our gathering will be morally incomplete.” Rabbi Hauer challenged me, asking if I thought that Orthodox Jews didn’t care about the dignity and safety of innocent Palestinians. I replied, “I don’t know, but what I do know is that I rarely hear Orthodox colleagues raise the subject.”

While the communal event featured several speakers from across the religious spectrum, only one ended up raising the issue of the suffering of innocent Palestinians caught in the crossfire of Israel’s war against Hamas: my chavruta, Rabbi Hauer. Though his voice was usually soft, his Torah was powerful and rooted in the deepest layers of Jewish teachings.

This summer, Rabbi Hauer and I were part of the Conference of Presidents’ Israel Leadership Mission. Our opening session was held at President Isaac Herzog’s home, Beit Hanasi. I took my seat next to my friend — and evidently President Herzog was struck that Rabbi Hauer and I were sitting next to each other. He marveled that the head of the Reform movement was sitting next to the head of the Orthodox Union. I told him that it was completely natural for me to sit next to my friend and cherished colleague. Yes, we disagreed on many issues, but we shared a profound respect and love for one another.

President Herzog asked me to offer words to close our session. I said that my prayer for the state of Israel was that one day it would not be newsworthy for a Reform rabbi to sit next to their Orthodox rabbi friend at an official meeting in the Jewish State. Rabbi Hauer’s humble leadership and devotion to the wellbeing of Klal Yisrael, the entire Jewish People, remains a beacon of light and love during these turbulent times. Our world is always in short supply of such kind, wise and principled leaders. How enormously blessed are we to have had such an exemplary soul leading us.

In the Talmud, we are taught: “Woe to those who are lost and cannot be replaced” ( Sanhedrin 111a). Today, we are the ones who are lost; our teacher, my chavruta, is the one who cannot be replaced.

UNION FOR REFORM JUDAISM

633 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017-6778 | 212.650.4000 | URJ@URJ.org

Knowledge Network: 855.URJ.1800 | URJ1800@URJ.org

Letter of condolence from the White House signed by President Donald Trump. In his letter, he refers to Rabbi Hauer’s “remarkable legacy” and stated that he was a “fierce advocate for the Jewish people.”

Message on social media by New York Governor Kathy

Hochul

Statement by the Jewish Federations of North America Board of Trustees

Chair Gary Torgow and President and CEO Eric Fingerhut

Hauer

to

it could also be

for

As the rabbi of Bnai Jacob Shaarei Zion in Baltimore for twenty-six years, Rabbi Moshe Hauer, together with his devoted wife, Rebbetzin Mindi, built a strong, vibrant kehillah that pulsed with life and purpose. A consummate talmid chacham and proud product of Ner Yisrael, Rabbi Hauer was equally revered for his empathy—for the way he listened, noticed and genuinely cared. His concern extended far beyond his own shul; he carried the weight of the broader Jewish community on his shoulders. It was that deep sense of responsibility that eventually drew him to a national role at the Orthodox Union. Yet even as he became executive vice president of the OU, he never left his kehillah behind. He stayed in Baltimore, commuting to New York each week, bringing with him the same warmth, humility and quiet strength that had defined both his family life and his rabbinate.

When Rabbi Hauer became executive vice president of the Orthodox Union in 2020, he brought with him the heart of a congregational rav—someone deeply attuned to the rhythm of real Jewish life. He led the OU through a time of global upheaval—first Covid, then October 7—with calm strength and Torah clarity. Under his guidance, the organization deepened its work with shuls and schools, expanded its rabbinic and educational efforts and fostered unity across the Orthodox world. His leadership was marked by warmth, integrity and a steady sense of purpose— always grounded in the conviction that the OU’s overriding mission is to strengthen the Jewish people’s commitment to Torah and mitzvot.

Speaking in Washington on the 180th day of the hostages’ captivity when the OU hand-delivered 180,000 letters from Americans to the White House appealing for the US to do even more to free them

Rabbi Moshe Hauer moved comfortably in the public square, speaking about faith with senators and other political leaders as naturally as he did with members of his shul. At the OU, he became the organization’s public voice, representing the Orthodox community in national, interfaith and governmental settings. Yet he never viewed advocacy as politics. For him, it was responsibility—Torah values translated into action. He listened as much as he spoke, and made everyone he met feel heard. Whether testifying before Congress on campus antisemitism, meeting with world leaders or addressing interfaith gatherings, he carried himself with humility and conviction, always anchored in Torah and guided by compassion.

In conversation with

By Dr. Sharon Grossman

Recently, after I delivered a lecture to a group of frum women on the Torah perspective on weight-loss medicine, a slim woman named Chani came over and said, “My sister, Dina, weighed 250 pounds. Her health was terrible. Ozempic is a miracle drug—she is now a size 4. Her diabetes disappeared, and her blood pressure and cholesterol are normal.” She paused, then added, “Can you write a prescription for me? I want to fit into a size 2 for my daughter’s wedding.”

Chani and Dina have different reasons for seeking weight-loss medication, illustrating two sides of a complex issue.1

Obesity is a public health crisis in the US. In 2020, nearly 75 percent of Americans were overweight, and 42 percent were obese. One in five children is obese. Orthodox Jews are not immune. Our rates of obesity are similar to—or perhaps even higher than—those of the general population.2 Moderate obesity reduces life expectancy by about three years; severe obesity cuts it by about ten.

Excess weight increases the risk of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, asthma, cancer, Alzheimer’s, depression and infertility among other health issues—as well as overall mortality. The longer one is obese, the greater the risks. Losing just 5 to 10 percent of one’s total body weight (10–20 pounds for a 200-pound person) can make a real difference.3

Dina had long struggled with her weight. The cycle of losing pounds only to gain them back was frustrating. Diet and exercise were not enough. In fact, 80 percent of people who lose weight regain half of it within five years.4 She wasn’t lacking willpower; rather, to lose weight and keep it off, she needed to overcome her body’s set point—the weight range your body naturally tries to stay at.

Ozempic is part of a new class of drugs, which mimics a naturally occurring hormone, that decreases appetite, delays gastric emptying, and creates a feeling of fullness to help sustain weight loss.5 These drugs were originally developed to treat diabetes but have been found to trigger weight loss in many people.6 Medical organizations recommend weight-loss medicine—as part of a comprehensive plan that includes nutrition, physical activity and behavioral counseling—for individuals with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, or 27 kg/m2 with comorbidities, who have failed to achieve significant weight loss.

Dr. Sharon Grossman is a writer and lecturer on medicine, public health and halachah. She has published widely in journals such as Tradition, Hakirah and the Lehrhaus as well as in medical literature. She is the author of the forthcoming book The Cure Before the Illness: Disease Prevention in Jewish Law (Maggid Books) and has lectured extensively to diverse audiences in Israel, as well as in Australia, Great Britain and the United States.

Dina’s program ensured that she met eligibility requirements and screened her for medical issues that could make her ineligible for the drug.7 She suffered no side effects—neither the common ones, like nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, nor the less common ones, such as allergic reactions and gallstones.8 Her results were astounding.

Beyond dramatic weight loss, these medicines also decrease blood pressure, cholesterol, and triglycerides, and improve glucose regulation. They reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke, and cardiac death by 20 percent in obese adults with pre-existing heart disease but without diabetes. Since these drugs are still relatively new, their full impact on disease prevention is not yet known. One study anticipates they could prevent 46 million heart attacks over ten years.

To maintain the benefits, Dina will need to continue these medicines and lifestyle interventions indefinitely. People who discontinue them typically regain two-thirds of their weight loss and lose the associated health benefits.9

While Dina uses the medication to manage her chronic health conditions, the cosmetic use of weight-loss medicine is on the rise. One expert speculates that millions of healthy-weight individuals may now be using these drugs.10 Some in the Orthodox community who are not obese use them for quick weight loss before a simchah or to improve their prospects for a shidduch. 11

In general, prescribing an FDA-approved drug offlabel—for uses other than those for which the drug was approved—is legal. However, physicians strongly disapprove of using weight-loss medicine as a quick fix because these drugs have not been studied in healthyweight individuals and may pose dangerous side effects for this population. They can cause healthy-weight people to become underweight and reduce muscle mass to dangerously low levels. Additionally, they might contribute to the development of eating disorders.12

Those who use these medicines off-label often obtain them through telehealth platforms or medical spas that do not rigorously evaluate patients, screen for potential contraindications, or monitor for complications.13 Furthermore, the surge in public demand for these medicines reduces their availability for those who need them to treat diabetes or obesity, exacerbating already difficult supply shortages. For these reasons, the American Medical Association (AMA) has stated that these medicines are approved for the treatment of obesity and not for cosmetic weight loss.14

I am helping to advance YU’s MBA program that empowers strategic thinkers to stay ahead in a rapidly evolving global economy.

Dr. Pablo Hernández-Lagos Director, Sy Syms School of Business MBA Program

Located in the heart of New York City’s business ecosystem, the Sy Syms School of Business empowers students to excel at the intersection of startups, technology and finance. Our MBA program cultivates expertise in entrepreneurship, strategic management, organizational behavior, business ethics and more, guided by faculty who are both accomplished scholars and industry leaders.

As these drugs become more common, how will they affect fat stigma and our ongoing obsession with thinness?

Eli Lilly, one of the leading manufacturers of weightloss drugs,15 explicitly states that these medicines “were not studied for . . . and should not be used for cosmetic weight loss.” This condemnation from a company that stands to profit from off-label use reinforces the medical community’s distaste for the drugs’ cosmetic application.16 Insurance companies have threatened to report suspected inappropriate or fraudulent prescribing practices to state licensure boards as well as federal and state law enforcement agencies. Florida restricts the prescription of weight-loss medicine to patients who meet strict BMI requirements. The English Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners calls prescribing weight-loss drugs for cosmetic purposes a public safety hazard and warns that prescribers may face regulatory scrutiny.17

As the cosmetic use of weight-loss medicine becomes increasingly common, the medical-legal community must clearly define the consequences. In the meantime, prescribing Ozempic for Chani may not be illegal, but depending on the jurisdiction, it could carry medicolegal implications.

Despite the fact that Dina is using weight-loss medication for legitimate health reasons, her doing so raises several halachic questions. First, may she take a medication that might cause long-term harm?

In two teshuvot, Rabbi Eliezer Waldenburg permits a terminally ill patient to take pain medication that does not treat the underlying disease and might hasten death. He reasons that as long as a physician administers the medication and its purpose is to relieve terrible suffering, verapo yerapeh—the physician’s license to heal—justifies any untoward effects that might arise.18 Based on these teshuvot, one might conclude that halachah permits Dina to take the drug despite its known risks, even without longterm safety data, since it has regulatory approval and is prescribed for a medical purpose.

Secondly, because weight-loss medicine is administered by injection, is Dina violating chovel—the prohibition against causing a wound? In this case, the injection may be permissible, as halachah generally rules leniently regarding injection wounds;19 the

prohibition may not apply to wounds that result from a medical procedure20 or are inflicted for a purpose; according to Rambam, chovel only applies to wounds intended to humiliate.21 Pharmaceutical companies are developing oral formulations of these drugs—which would eliminate chovel concerns altogether.22

Finally, does the restriction of food intake caused by these medicines violate the prohibition against selfharm? Rabbi Moshe Feinstein permitted a woman to diet,23 arguing that the prohibition against self-harm obligates people to follow medically prescribed diets, since failure to do so would cause extreme suffering from obesity-related diseases. For Dina, Ozempic arrested this risk, preventing debilitating complications and adding years to her life. Thus, drawing on Rav Moshe’s teshuvah, halachah not only permits Dina to take Ozempic but requires it. Here, weight-loss medicine falls under the mitzvah of v’nishmartem me’od l’nafshoteichem (the obligation to preserve one’s health) and the general duty to prevent disease. If a doctor recommends weight-loss medicine, halachah obligates the patient to comply as part of the broader obligation to follow medical advice.24

While Jewish law embraces the use of weight-loss medicine to manage obesity, its response to cosmetic use is less clear-cut. One potential parallel lies in teshuvot addressing the halachic permissibility of cosmetic surgery, which tests the boundaries of what is allowed in the pursuit of improved appearance. Cosmetic procedures may violate chovel, interfere with G-d’s design and expose individuals to risk for nonmedical reasons—raising the question of whether verapo yerapeh even applies.

Rabbi Eliezer Waldenburg takes the most stringent view, prohibiting cosmetic surgery on these grounds and arguing that it implies G-d’s creation is flawed.25 However, he does distinguish between procedures purely for aesthetic reasons and those that restore the body to its original state.

In contrast, the Chelkat Yaakov, Rabbi Yaakov Breisch, permits a young woman to undergo cosmetic surgery to improve her appearance in order to find a spouse, since it is done to relieve tza’ar (mental anguish).26 He cites Shabbat 50b, which allows a person to remove scabs if they cause pain. Tosafot (s.v. bishvil) add: “If the only pain he suffers is the embarrassment of walking among people, it is permitted—because there is no greater pain than this.” Rabbi Breisch suggests that Tosafot’s definition of pain includes psychological distress.

He concludes that, since the risks are low, one may undergo surgery for a non-life-threatening condition, particularly because shomer peta’im Hashem—the principle that one may engage in potentially dangerous activities that society has demonstrated a willingness to

I am an award-winning clinical psychologist and Ferkauf professor pioneering innovative migraine treatments.

Dr. Elizabeth K. Seng Professor of Psychology, Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology

For over 60 years, Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology has been a trailblazer in psychology and counseling education, consistently ranked among the nation’s top institutions. We proudly attract a diverse, global student body, all drawn to our commitment to excellence. With a distinguished faculty and a supportive administration, we provide an exceptional private education designed to empower students and ensure their success in the field.

accept—might justify any residual risk.

Rabbi Menashe Klein permits a young woman to undergo plastic surgery to correct a facial imperfection that interfered with her ability to find a spouse,27 citing Talmudic precedents that allow medical interventions to improve one’s appearance.28

Rav Moshe also permitted such procedures,29 when it alleviates suffering or embarrassment, invoking v’ahavta l’rei’acha kamocha. It would seem that the reasoning is that improving one’s appearance—when it removes distress—constitutes an act of chesed and is consistent with the Torah’s mandate to love and respect others (including oneself).

It is unclear whether Rav Moshe’s teshuvah is limited to cases of significant need. Finally, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach asks rhetorically why halachah would prohibit surgery aimed solely at restoring a normal appearance. He writes, “If the plastic surgery is done to prevent suffering and shame caused by a defect in his looks . . . this would be permitted based on the Tosafot and the Gemara, since the purpose is to remove a blemish.”

Nevertheless, he adds, “If the only reason is for beauty, this is not permitted.”30

Do the teshuvot that permit cosmetic surgery also apply to the cosmetic use of weight-loss medication?

The risks associated with these drugs may be lower, since they do not involve surgery. Even Rabbi Waldenburg’s categorical prohibition against plastic surgery might leave room for the cosmetic use of weight-loss medication, since it can be viewed as restoring the body to its original, thinner form. On the other hand, one must ask: why does Chani want to use Ozempic? Does she meet Tosafot’s definition of tza’ar—psychological distress so severe that she is embarrassed to “walk among people”? Is she truly uncomfortable in her current state to the point of not wanting to be seen at her daughter’s wedding?

Furthermore, in order to receive Ozempic for cosmetic purposes, Chani would either have to lie about her weight to a telehealth provider or find a healthcare provider who disregards the clinical guidelines—raising several halachic concerns. These include prohibitions against sheker (lying), geneivat da’at (being deliberately misleading), mesayei’a l’dvar aveirah (enabling another to sin) and lifnei iver (placing a stumbling block before the blind). If these medicines are in short supply, the halachic implications intensify: is it permissible to use them for non-medical, cosmetic reasons when doing so may deprive those who genuinely need them to treat diabetes or obesity?

Although the medical community generally views cosmetic surgery as an acceptable intervention, the AMA disapproves of using weight-loss medications for purely

cosmetic purposes.31 This disapproval may undermine halachic comparisons between cosmetic surgery and the cosmetic use of weight-loss drugs. Can the principles of verapo yerapeh and shomer peta’im Hashem justify the risks, given the medical community’s condemnation of this practice?

If halachah prohibits the cosmetic use of these drugs, might it distinguish between different types of users—such as between men and women, or between young women hoping to improve their shidduch prospects and alreadymarried women seeking to enhance their appearance for a family simchah? Conversely, if halachah permits such use, should Torah-observant Jews still avoid it due to the unresolved halachic, ethical and societal concerns?

As the use of these medications becomes increasingly common in the Orthodox community, posekim will need to consider these issues and determine whether such use parallels that of cosmetic surgery, which halachah generally permits. The introduction of medicines for treating obesity and obesity-related diseases also requires us to consider their broader implications for our community. Rabbi Auerbach’s teshuvah raises questions about what we consider normal. Does body size define that? And if it does, what size do we view as normal? As these drugs become more common, how will they affect fat stigma and our ongoing obsession with thinness? On the one hand, if these medicines make thinness easy to attain, perhaps we will desire it less. Perhaps they will increase our compassion for those who are overweight, since the drugs highlight the difficulty of maintaining weight loss. On the other hand, if becoming thin is so easy, we may begin to see it as a basic aspect of self-grooming—leading to the expectation that those who are overweight should take these medicines. This perspective could reinforce weight stigma and undo decades of efforts to promote body positivity.

In a society where appearance holds such importance, many of us will feel compelled to do more. Fifty percent of thirteen-year-old girls are already unhappy with their bodies; by age seventeen, that number rises to 80 percent.32 Will these drugs lead to eating disorders among Orthodox Jews?33

I prepare future leaders to navigate a changing world with clarity, courage and timeless Torah values.

Rabbi Daniel Feldman

Rosh Yeshiva, RIETS

Sgan Rosh Kollel of the Bella and Harry Wexner Kollel Elyon

By advancing our academic excellence and providing a values-based education, Yeshiva University is preparing the next generation of Jewish leaders for both personal and professional success, poised to transform their communities, our people and the world around them.

With your generosity, we can meet the evolving needs of Yeshiva University and propel it to unprecedented heights for our Jewish future. Please join us in achieving our $613-million campaign

These questions are critical as our community grapples with the role of weight-loss medicines. Doctors, pharmaceutical companies, the healthcare industry and patients must work together to prevent the misuse of these drugs and ensure that those who need them receive them.34 Moving forward, we must heed Rabbi Waldenburg’s warning that our obsession with beauty contradicts Torah values: “Beauty is vain. A woman who fears G-d—she is to be praised.”35

My conversation with Chani evoked conflicting emotions: awe at the miracle drug that could reverse the obesity epidemic; hope for those like Dina who struggle with obesity; and fear that our medical ability to induce weight loss will reinforce weight stigma, an overemphasis on external appearances, and eating disorders. Dr. David Kessler, the former FDA commissioner who led the fight against the tobacco industry, states, “The fight against tobacco . . . has been the great public health success. Obesity has been the great public health failure.”36 Armed with these new medicines, we stand at a defining moment in the battle against obesity-related diseases. If we use them judiciously, we have the potential to save countless lives and fulfill Hashem’s mandate to eradicate illness.

Notes

1. For a complete discussion of obesity and its management in Jewish law, see my forthcoming book, The Cure Before the Illness: Disease Prevention in Jewish Law (Maggid Books). I would like to thank Dr. Jody Dushay, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and attending physician in the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, for taking the time to discuss weight-loss medicine with me and for reviewing the manuscript. Her input greatly enhanced this article.

2. Katelyn Newman, “Obesity in America: A Public Health Crisis,” US News & World Report, Sept 19, 2019; Craig M. Hales et al., “Trends in Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in US Youth and Adults by Sex and Age, 2007–2008 to 2015–2016,” JAMA 319, no. 16 (Apr 2018): 1723–25, https://doi. org:10.1001/jama.2018.3060. Obesity is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30.0 or higher. Severe obesity is defined as having a BMI of 40.0 or higher. https:// www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult-obesity-facts/ index.html; https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/ childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesityfacts.html; Maureen R. Benjamins et al., “A Local Community Health Survey: Findings from a Population-Based Survey of the Largest Jewish Community in Chicago,” Journal of Community Health 31 (Dec 2006): 479–95, https://doi.org./10.1007/ s10900-006-9025-5; https:// www.cityhackneyhealth.org.uk/ wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ Orthodox-Jewish-Health-NeedsAssessment-2018.pdf.

3. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/living-with/healthy-weight. html; https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/obesity/obesity-fact-sheet#what-is-knownabout-the-relationship-between-obesity-and-cancer-. The American Cancer Society attributes 11 percent of cancers in women, approximately 5 percent of cancers in men, and 7 percent of all cancer deaths to excess body weight—about 40,000 deaths each year. (This figure does not include deaths from other obesity-related illnesses and conditions.) https:// www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesityconsequences/health-effects/; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC5497590/

4. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/ S0025712517301360?via%3Dihub.

5. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/set-point-theory/

6. These weight-loss medications are part of a class of drugs known as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1s). Semaglutide is a GLP-1 agonist, while tirzepatide is a dual agonist, acting on both the GLP-1 receptor and the glucosedependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor. At lower doses for treating diabetes, semaglutide is marketed as Ozempic; at higher doses for treating obesity, it is sold under the name Wegovy. Tirzepatide is marketed as Mounjaro for diabetes and as Zepbound for obesity.

7. This is the recommendation of the Obesity Society, the Endocrine Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK279038; https://time.com/6285055/wegovyteenagers-weight-loss-risks/.

8. Liyun He et al., “Association of Glucagon-Like Peptide--1 Receptor Agonist Use with Risk of Gallbladder and Biliary Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials,” JAMA Internal Medicine 182, no. 5 (May 1, 2022): 513–19, https://doi.org/10.1001/ jamainternmed.2022.0338.; E Pérez et al., “A Case Report of Allergy to Exenatide,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Practice 2, no. 6 (Nov–Dec 2014): 822–23; and https://eposters.ddw.org/ddw/2024/ddw2024/414874/piyush.nathani.incidence.of.gastrointestinal. side.effects.in.patients.html.

9. https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/ Articles/2023/08/10/14/29/SELECT-Semaglutide-ReducesRisk-of-MACE-in-Adults-With-Overweight-or-Obesity; https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2307563; https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9542252.

10. Personal communication with Dr. Jody Dushay, August 2025. Thirty percent of plastic surgeons reported having used weight-loss medicine; of these, 70 percent indicated that they did so for cosmetic weight-loss alone. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38085071; Nathan D. Wong, Hridhay Karthikeyan, and Wenjun Fan, “US Population Eligibility and Estimated Impact of Semaglutide Treatment on Obesity Prevalence and Cardiovascular Disease Events in US Adults,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Aug 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0735-1097(23)02259-3; https://www.today.com/health/ celebrities-on-ozempic-rcna129740

11. https://jewinthecity.com/2025/03/does-judaism-allow-youto-take-ozempic-and-other-weight-loss-drugs/.

12. Personal communication with Dr. Jody Dushay,

If you’re going to make it from scratch, make it the best.

Breakstone’s butter brings out the pure flavor and flaky texture that everyone loves in Chanukah cookies and treats.

Touro University is all in on one mission—your excellence. We’re here to help you become exceptional: highly successful, purpose-driven, and ready to make a meaningful impact. The first step? Choose Touro. We’ll take you where you want to go.

AND

THE SCHOOL OF HEALTH SCIENCES, TOURO UNIVERSITY FUTURE PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS

Fifty percent of thirteen-year-old girls are already unhappy with their bodies; by age seventeen, that number rises to 80 percent. Will these drugs lead to eating disorders among Orthodox Jews?

August 2025. https://www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/983004#vp_2; D.C.D. Hope and T.M.M. Tan, “Skeletal Muscle Loss and Sarcopenia in Obesity Pharmacotherapy,” Nature Reviews Endocrinology 20 (2024): 695–96 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574024-01041-4; https://dom-pubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ doi/10.1111/dom.14725; and https://time.com/6290294/ weight-loss-drugs-ozempic-demonization-essay/.

13. Personal communication with Dr. Jody Dushay, August 2025. Some telehealth platforms accept patients based on patient report. https://www.newyorker.com/ magazine/2023/03/27/will-the-ozempic-era-changehow-we-think-about-being-fat-and-being-thin; https:// magazine.ucsf.edu/weight-loss-drugs-too-good-to-be-true

14. https://www.ama-assn.org/public-health/chronicdiseases/what-doctors-wish-patients-knew-aboutanti-obesity-medication Despite these concerns, some doctors are writing prescriptions for weight-loss medicine purely for cosmetic purposes. https://beverlyhillscourier. com/2023/11/16/the-real-skinny-on-weight-loss/; Personal communication, Dr. Jody Dushay, August 2025.

15. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/2024-oscars-eli-lilly-adweight-loss-drug-mounjaro-ozempic.

16. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zYsU9ltnH8w

17. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/06/11/ weight-loss-ozempic-wegovy-insurance/?utm_ campaign=KHN%3A%20First%20Edition&utm_ medium=email&_hsmi=262066865&_hsenc=p2ANqtz9rIvynBptFsvvj0doDkQYFbvNOgwtFzvPvqY3Lam5f eDA5V4gdYZuELna20MTZAFOD_wqPN6lJvzvminl; https://www.lilesparker.com/2024/10/28/auditsand-investigations-of-semaglutide-and-other-glp-1claims/?utm_source=chatgpt.com; https://www.jccp.org. uk/NewsEvent/prescribing-weight-loss-procedures-inthe-cosmetic-sector-1.

18. Tzitz Eliezer 13:87; 14:103.