America, Iberia, and Africa Before the Conquest

chronology

c. 100 b.c.–750 a.d. Emergence and prominence of Teotihuacan in Mesoamerica

250–900 Maya Classic period

718–1492 Christian Reconquest of Iberia from Muslims

c. 900–1540 Maya Postclassic period

c. 1325 Mexica begin to build Tenochtitlan

1415 Portuguese capture Ceuta in North Africa

1426–1521 Triple Alliance and Aztec Empire

c. 1438–1533 Inka Empire

1469

Marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel of Castile 1492 Columbus’s first voyage; fall of Granada; expulsion of Jews from “Spain”; first Castilian grammar published 1493 Papal donation; Columbus’s second voyage (1493–96); “Columbian Exchange” begins with Spanish introduction of sugarcane, horses, cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens, wheat, olive trees, and grapevines into Caribbean islands

1494 Treaty of Tordesillas

1500 Pedro Alvarez Cabral lands on Brazilian coast

1502 Nicolás de Ovando takes about 2,500 settlers, including Las Casas, to Española; Moctezuma II elected tlatoani of Mexica

1510–11 Diego de Velázquez conquers Cuba

1512 Laws of Burgos

1513 Blasco Núñez de Balboa crosses isthmus of Panama to Pacific

The Western Hemisphere’s history begins with the arrival of its first inhabitants. Most scholars agree that the hemisphere was settled in a series of migrations across the Bering Strait from Asia. There is less consensus about when these migrations took place. Hunting populations expanded rapidly along the west coast of the

hemisphere after 14,000 b.c. Some evidence suggests, however, that human populations may have been present in South America as early as 35,000 b.c. If this is verified by additional research, then some humans probably reached the hemisphere using small boats.

Regardless of the date of first arrivals, it took millennia to occupy the hemisphere. Societies in Mexico, Central America, and the Andean region had initiated the development of agriculture and complex political forms before 5000 b.c.

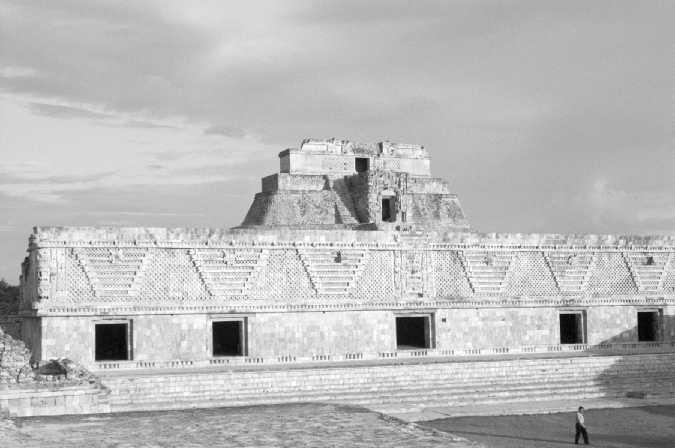

The main temple at Chichen Itza, near the modern city of Merida, Mexico. Chichen Itza was the major Postclassic-era Maya city.

On the other hand, the Caribbean Basin and the plains of southern South America were inhabited less than 2,000 years before Columbus’s arrival. The hemisphere’s indigenous population at the moment of contact in 1492 was probably between 35 million and 55 million.

Although the Aztecs and Inkas are the civilizations best known during the age of conquest, the inhabitants of these empires constituted only a minority of the total Amerindian population and resided in geographic areas that together represented only a small portion of Latin America’s landscape. Aymara, Caribs, Chichimecas, Ge, Guaraní, Mapuche, Maya, Muisca, Otomí, Pueblo, Quibaya, Taino, Tepaneca, Tupí, and Zapotec joined a host of other peoples and linguistic groups who inhabited the Americas; together they formed a human mosaic whose diverse characteristics greatly influenced the ways in which colonial Latin America developed. By 1500 over 350 major tribal groups, 15 distinct cultural centers, and more than 160 linguistic stocks could be found in Latin America. Despite the variety suggested by these numbers, there were, essentially, three forms or levels of Indian culture. One was a largely nomadic group that relied on hunting, fishing, and gathering for subsistence; its members had changed little from the people who first made stone points in the New World in about 10,000 b.c. A second group was sedentary or semisedentary and depended primarily on agriculture for subsistence. Having developed technologies different from those of the nomadic peoples, its

Inka ruin, Machu Picchu, Peru.

members benefited from the domestication of plants that had taken place after about 5000 b.c. The third group featured dense, sedentary populations, surplus agricultural production, greater specialization of labor and social differentiation, and large-scale public construction projects. These complex civilizations were located only in Mesoamerica and western South America. The civilizations of Teotihuacan, Monte Albán, Tiwanaku, Chimú, and several Maya cultures were among its most important early examples.

Mesoamerica is the term employed to define a culturally unified geographic area that includes central and southern Mexico and most of Central America north of the isthmus of Panama. Marked by great diversity of landscape and climate, Mesoamerica was the cradle of a series of advanced urbanized civilizations based on sedentary agriculture. Never more than a fraction of this large region was ever united politically. Instead, its inhabitants shared a cultural tradition that flourished most spectacularly in the hot country of the Gulf of Mexico coast with the Olmec civilization between 1200 and 400 b.c. While linguistic diversity and regional variations persisted, common cultural elements can be traced from this origin. They include polytheistic religions in which the deities had dual (male/female) natures, rulers who exercised both secular and religious roles, the use of warfare for obtaining sacrificial victims, and a belief that bloodletting was necessary for a society’s survival and prosperity. The use of ritual as well as solar calendars, the construction of monumental architecture including pyramids, the employment of a numeric system that used twenty as its base, emphasis on a jaguar deity, and the ubiquity of ball courts in which a game using a solid rubber ball was played were additional characteristics of complex Mesoamerican societies. Long-distance trade involving both subsistence goods and artisanal products using obsidian, jade, shell, and feathers, among other items, facilitated cultural exchange in the absence of political integration. This rich cultural tradition influenced all later Mesoamerican civilizations, including the Maya and the Aztecs.

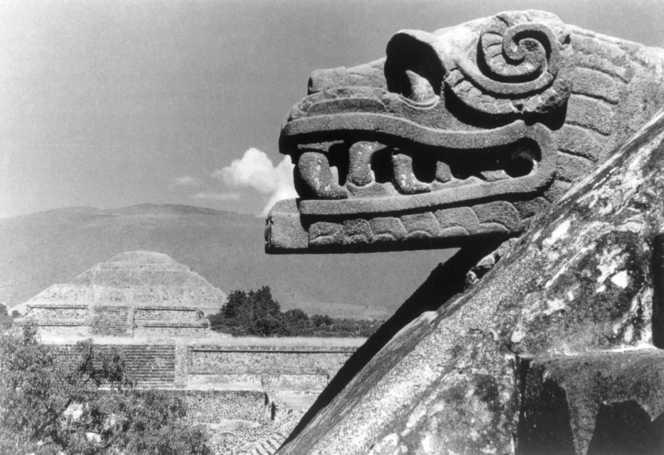

Following the decline of the Olmecs, the city of Teotihuacan (100 b.c.–750 a.d.) exercised enormous influence in the development and spread of Mesoamerican culture. Located about thirty miles northeast of modern Mexico City, Teotihuacan was the center of a commercial system that extended to the Gulf coast and into Central America. At its height its urban population reached 150,000, making it one of the world’s largest cities at that time. One of the most important temples at Teotihuacan was devoted to the cult of the god Quetzalcoatl, or Feathered Serpent. Commonly represented as a snake covered with feathers, Quetzalcoatl was associated with fertility, the wind, and creation. Following Teotihuacan’s decline in the eighth century, the Toltecs dominated central Mexico from their capital at Tula. Although not clearly tied to Teotihuacan’s decline in the eighth century, the Toltecs came to dominate central Mexico by the tenth century. The Toltecs used military power to extend their influence and manage complex tribute and trade relationships with dependencies. Tula was both an administrative and a religious center. It was constructed on a grand scale with colonnaded patios, raised

Before the Conquest

platforms, and numerous temples. Many of the buildings were decorated with scenes suggesting warfare and human sacrifice.

In the Andean region, geographic conditions were even more demanding than in Mesoamerica. The development of complex civilizations after 1000 b.c. depended on the earlier evolution of social and economic strategies in response to changing environmental, demographic, and social conditions. Along the arid coastal plain and in the high valleys of the Andes, collective labor obligations made possible both intensive agriculture and long-distance trade. Irrigation projects, the draining of wetlands, large-scale terracing, and road construction all depended on collective labor obligations, called mit’a by the native population and later mita by the Spanish. The exchange of goods produced in the region’s ecological niches (lowland maize, highland llama wool, and coca from the upper Amazon region, for example) enriched these societies and made possible the rise of cities and the growth of powerful states.

The chronology of state development and urbanization within the Andean region was generally similar to that in Mesoamerica. However, there was greater variation in cultural practices because of the unique environmental challenges posed by the arid coastal plain and high altitudes of the mountainous regions. Chavín was one of the most important early Andean civilizations. It dominated a populous region that included substantial portions of both the highlands and coastal plain of Peru between 900 and 250 b.c. Located at 10,300 feet in the eastern range of the Andes north of present-day Lima, its capital, Chavín de Huantar, was a commercial center that built upon a long tradition of urban development and

Representations of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent at Teotihuacan. Teotihuacan was the largest of the Classic-era cities in Mexico. In the background is the Temple of the Moon.

monumental architecture initiated earlier on the Peruvian coast. The expansion of Chavín’s power was probably related to the introduction of llamas from the highlands to the coastal lowlands. Llamas dramatically reduced the need for human carriers in trade since one driver could control as many as thirty animals, each carrying up to seventy pounds. Chavín exhibited all of the distinguishing characteristics found in later Andean civilizations. Its architecture featured large complexes of multilevel platforms topped by small residences for the elite and buildings used for ritual purposes. As in the urban centers of Mesoamerica, society was stratified from the ruler down. Fine textile production, gold jewelry, and polytheistic religion also characterized the Chavín civilization until its collapse. By the time that increased warfare disrupted long-distance trade and brought about the demise of Chavín, its material culture, statecraft, architecture, and urban planning had spread throughout the Andean region. The Moche, who dominated the north coastal region of Peru from 200 to 700 a.d., were heirs to many of Chavín’s contributions.

In the highlands, two powerful civilizations, Tiwanaku and Wari, developed after 500 a.d. Tiwanaku’s expansion near Lake Titicaca in modern Bolivia rested on both enormous drainage projects that created raised fields and permitted intensive cultivation and the control of large herds of llamas. At the height of its power, Tiwanaku was the center of a large trade network that stretched to Chile in the south. Pack-trains of llamas connected the capital to dependent towns that organized the exchange of goods produced throughout the Andean region. Large buildings constructed of cut stone dominated the urban center of Tiwanaku. A hereditary elite able to control a substantial labor force ruled this highly stratified society. Wari, located near present-day Ayacucho, may have begun as a dependency of Tiwanaku, but it soon established an independent identity and expanded through warfare into the northern highlands as well as the coastal area once controlled by the Moche. The construction of roads as part of Wari’s strategy for military control and communication was a legacy bequeathed to the Inkas who, like the Aztecs in central Mexico, held political dominance in the populous areas of the Andean region when Europeans first arrived.

the Maya

Building in part upon the rich legacy of the Olmec culture, the Maya developed an impressive civilization in present-day Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, southern Mexico, and Yucatan. Although sharing many cultural similarities, the Maya were separated by linguistic differences and organized into numerous city-states. Because no Maya center was ever powerful enough to impose a unified political structure, the long period from around 200 a.d. to the arrival of the Spaniards was characterized by the struggle of rival kingdoms for regional domination.

Given the difficulties imposed by fragile soils, dense forest, and a tropical climate characterized by periods of drought and heavy rains, Maya cultural and architectural achievements were remarkable. The development of effective agricultural technologies increased productivity and led to population growth and

urbanization. During the Classic era (250–900 a.d.), the largest Maya cities had populations in excess of 50,000.

From earliest times, Maya agriculturalists used slash-and-burn or “swidden” cultivation in which small trees and brush were cut down and then burned. Although this form of cultivation produced high yields in initial years, it quickly used up the soil’s nutrients. Falling yields forced farmers to move to new fields and begin the cycle again. The high urban population levels of the Classic period, therefore, required more intensive agriculture as well. Wherever possible, local rulers organized their lineages or clans in large-scale projects to drain swamps and low-lying river banks to create elevated fields near urban centers. The construction of trenches to drain surplus water yielded rich soils that the workers then heaped up to create wetland fields. In areas with long dry seasons, the Maya constructed irrigation canals and reservoirs. Terraces built on mountainsides caught rainwater runoff and permitted additional cultivation. Household gardens further augmented food supplies with condiments and fruits that supplemented the dietary staples of maize (corn), beans, and squash. The Maya also managed nearby forests to promote the growth of useful trees and shrubs as well as the conservation of deer and other animals that provided dietary protein.

In the late Preclassic period, the increased agricultural production that followed these innovations helped make possible the development of large cities like El Mirador. During the Classic period, Maya city-states proliferated in an era of dramatic urbanization. One of the largest of the Classic-period cities was Tikal, in modern Guatemala, which had a population of more than 50,000 and controlled a network of dependent cities and towns. Smaller city-states had fewer than 20,000 inhabitants. Each independent city served as the religious and political center for the subordinated agricultural population dispersed among the milpas (maize fields) of the countryside.

Classic-era cities had dense central precincts visually dominated by monumental architecture. Large cities boasted numerous high pyramids topped by enclosed sanctuaries, ceremonial platforms, and elaborately decorated elite palaces built on elevated platforms or on constructed mounds. Pyramids also served as burial locations for rulers and other members of the elite. The largest and most impressive buildings were located around open plazas that provided the ceremonial center for public life. Even small towns had at least one such plaza dominated by one or more pyramids and elite residences.

Impressive public rituals held in Maya cities attracted both full-time urban residents and the rural population from the surrounding countryside. While the smaller dependent communities provided an elaborate ritual life, the capital of every Maya city-state sustained a dense schedule of impressive ceremonies led by its royal family and powerful nobles. These ritual performances were carefully staged on elevated platforms and pyramids that drew the viewers’ attention heavenward. The combination of richly decorated architecture, complex ritual, and splendid costumes served to awe the masses and legitimize the authority of ruler and nobility. Because there were no clear boundaries between political and religious functions,

divination, sacrifice, astronomy, and hieroglyphic writing were the domain of rulers, their consorts, and other members of the hereditary elite.

Scenes of ritual life depicted on ceramics and wall paintings clearly indicate the Maya’s love of decoration. Sculpture and stucco decorations painted in fine designs and bright colors covered nearly all public buildings. Religious allegories, the genealogies of rulers, and important historical events were familiar motifs. Artisans also erected beautifully carved altars and stone monoliths (stelae) near major temples. Throughout their pre-Columbian existence, the Maya constructed this rich architectural and artistic legacy with the limited technology present in Mesoamerica. The Maya did not develop metallurgy until late in the Classic era and used it only to produce jewelry and decorations for the elite. In the Postclassic period the Maya initiated the use of copper axes in agriculture. Artisans and their numerous male and female assistants cut and fitted the stones used for palaces, pyramids, and housing aided only by levers and stone tools. Each new wave of urban construction represented the mobilization and organization of thousands of laborers by the elite. Thus the urban building boom of the Classic period reflected the growing ability of rulers to appropriate the labor of their subjects more than the application of new or improved technologies.

The ancient Maya traced their ancestry through both male and female lines, but family lineage was patrilineal. Maya families were large, and multiple generations commonly lived in a single residence or compound. In each generation a single male, usually the eldest, held authority within the family. Related families were, in turn, organized in hierarchical lineages or clans with one family and its male head granted preeminence.

The Nunnery complex at the Classic-era Maya site of Uxmal.

By the Classic period, Maya society was rigidly hierarchical. Hereditary lords and a middling group of skilled artisans and scribes were separated by a deep social chasm from the farmers of the countryside. To justify their elevated position, the elite claimed to be the patrilineal descendants of the original warlords who had initiated the development of urban life. Most commonly, kings were selected by primogeniture from the ruling family; on at least two occasions during the Classic period, however, women ruled Maya city-states. Other elite families provided men who led military units in battle, administered dependent towns, collected taxes, and supervised market activities. Although literacy was very limited, writing was important to religious and political life. As a result, scribes held an elevated position in Maya society and some may have come from noble families.

In the Classic period and earlier, rulers and other members of the elite, assisted by shamans (diviners and curers who communicated with the spirit world), served both priestly and political functions. They decorated their bodies with paint and tattoos and wore elaborate costumes of textiles, animal skins, and feathers to project secular power and divine sanction. Kings communicated directly with the supernatural residents of the other worlds and with deified royal ancestors through bloodletting rituals and hallucinogenic trances. Scenes of rulers and their consorts drawing blood from tongues, lips, ears, and even genitals survive on frescos and painted pottery. For the Maya, blood sacrifice was essential to the very survival of the world. The blood of the most exalted members of the society was, therefore, the greatest gift to the gods.

In the Postclassic period, the boundary between political and religious authority remained blurred, although there is some evidence that a priestly class distinguishable from the political elite had come into existence. Priests, like other members of the elite, inherited their exalted status and were not celibate. They provided divinations and prophecies, often induced by hallucinogens, and kept the genealogies of the lineages. They and the rulers directed the human sacrifices required by the gods. Finally, priests provided the society’s intellectual class and were, therefore, responsible for conserving the skills of reading and writing, for pursuing astronomical knowledge, and for maintaining the Maya calendars.

Although some merchants and artisans may have been related to the ruling lineages, these two occupations occupied an intermediate status between the lords and commoners. From the Preclassic period, the Maya maintained complex trade relationships over long distances. Both basic subsistence goods and luxury items were available in markets scheduled to meet on set days in the Maya calendar. Each kingdom, indeed each village and household, used these markets to acquire products not produced locally. As a result, a great deal of specialization was present by the Classic period. Maya exchanged jade, cacao (chocolate beans used both to produce a beverage consumed by the elite and as money), cotton textiles, ceramics, salt, feathers, and foods, especially game and honey taken from the forest. Merchants could acquire significant wealth and the wealthiest lived in large multiple-family compounds. Some scholars believe that by the Postclassic period rulers forced merchants to pay tribute and prohibited them from dressing in the garments of the nobility.

A specialized class of urban craftsmen produced the beautiful jewelry, ceramics, murals, and architecture of the Maya. Their skills were essential for the creation and maintenance of both public buildings and ritual life, and, as a result, they enjoyed a higher status than rural commoners. Although the evidence is ambiguous, certain families who trained children to follow their parents’ careers probably monopolized the craft skills. Some crafts may also have had a regional basis, with weavers concentrated in cotton-growing areas and the craftsmen who fashioned tools and weapons from obsidian (volcanic glass) located near the source of their raw materials. Most clearly, the largest and wealthiest cities had the largest concentration of accomplished craftsmen.

The vast majority of the Maya were born into lower-status families and devoted their lives to agriculture. These commoners inherited their land rights through their lineage. Members of lineages were obligated to help family members in shared agricultural tasks as well as to provide labor and tribute to the elite. Female commoners played a central role in the household economy, maintaining essential garden plots, weaving, and managing family life. By the end of the Classic period a large group of commoners labored on the private estates of the nobility. Below this group were the slaves. Slaves were commoners taken captive in war or criminals; once enslaved, the status could become hereditary unless the slave were ransomed by his family.

Warfare was central to Maya life and infused with religious meaning and elaborate ritual. Battle scenes and the depiction of the torture and sacrifice of captives were frequent decorative themes. Since military movements were easier and little agricultural labor was required, the hot and dry spring season was the season of armed conflict. Maya military forces usually fought to secure captives rather than territory, although during the Classic period Tikal and other powerful kingdoms initiated wars of conquest against their neighbors.

Days of fasting, a sacred ritual to enlist the support of the gods, and rites of purification led by the king and high-ranking nobles preceded battle. A king and his nobles donned elaborate war regalia and carefully painted their faces in preparation. Armies also included large numbers of commoners, but these levies had little formal training and employed inferior weapons. Typically, the victorious side ritually sacrificed elite captives. Surviving murals and ceramic paintings show kings and other nobles stripped of their rich garments and compelled to kneel at the feet of their rivals or forced to endure torture. Most wars, however, were inconclusive, and seldom was a ruling lineage overturned or territory lost as the result of battlefield defeat.

Building on the Olmec legacy, the Maya made important contributions to the development of the Mesoamerican calendar. They also developed both mathematics and writing. The complexity of their calendric system reflected the Maya concern with time and the cosmos. Each day was identified by three separate dating systems. As was true throughout Mesoamerica, two calendars tracked the ritual cycle (260 days divided into 13 months of 20 days) and a solar calendar (365 days divided into 18 months of 20 days, with 5 unfavorable days at the end of the year).

The Maya believed the concurrence of these two calendars every fifty-two years to be especially ominous. Uniquely among Mesoamerican peoples, the Maya also maintained a continuous “long count” calendar that began at creation, an event they dated at 3114 b.c. These accurate calendric systems and the astronomical observations upon which they were based depended on Maya contributions to mathematics and writing. Their system of mathematics included the concepts of the zero and place value but had limited notational signs.

The Maya were almost unique among pre-Columbian cultures in the Americas in producing a written literature that has survived to the modern era. Employing a form of hieroglyphic inscription that signified whole words or concepts as well as phonetic cues or syllables, Maya scribes most commonly wrote about public life, religious belief, and the genealogies and biographies of rulers and their ancestors. Only four of these books of bark paper or deerskin still exist. However, other elements of the Maya literary and historical legacy remain inscribed on ceramics, jade, shell, bone, stone columns, and monumental buildings of the urban centers.

The destruction or abandonment of many major urban centers between 800 and 900 a.d. brought the Maya Classic period to a close. There were probably several interrelated causes for this catastrophe, but no scholarly consensus exists. The destruction in about 750 a.d. of Teotihuacan, the important central Mexican commercial center tied to the Maya region, disrupted long-distance trade and thus might have undermined the legitimacy of Maya rulers. More likely, growing population pressure, especially among the elite, led to environmental degradation and falling agricultural productivity. This environmental crisis, in turn, might have led to social unrest and increased levels of warfare as desperate elites sought to increase the tributes of agriculturalists or to acquire additional agricultural land through conquest. Some scholars have suggested that climatic change contributed to the collapse, but evidence supporting this theory is slight. Regardless of the disputed causes, there is agreement that by 900 a.d. the Maya had begun to enter a new era, the Postclassic.

Archaeology has revealed evidence of cultural ties between the Toltecs of central Mexico and the Maya of the Yucatan during the early Postclassic period, but the character of this relationship is in dispute. Chichen Itza, the most impressive Postclassic Maya center, shared both architectural elements and a symbolic vocabulary with the Toltec capital of Tula. Among these shared characteristics was a tzompantli, a low platform decorated with carvings of human heads. Bas-relief carvings of jaguars, vultures holding human hearts, and images of the rain god Tlaloc were also found at both cities. Other key architectural elements of Chichen Itza appear to have central Mexican antecedents as well. The Temple of Warriors, a stepped platform surmounted by columns, was embellished with a chacmool, a characteristic Toltec sculpture of a figure holding on his stomach a bowl to receive sacrifices. Finally, while Maya cities had ball courts from early days, Chichen Itza’s largest court was constructed and decorated in the style of the Toltecs.

Sixteenth-century histories written by Spanish priests suggest that the Toltecs conquered the Maya of the Yucatan. Based on native informants, these histories

claim that the Toltec invasion was led by the prince Topiltzin, who had been forced to leave Tula by a rival warrior faction associated with the god Tezcatlipoca. Defeated by the powerful magic of his adversary, Topiltzin, called Kukulkan by the Maya, and his followers migrated to the east and established a new capital at Chichen Itza after defeating the Maya.

Recent archaeology has confirmed cultural parallels between the Maya and the Toltecs, but the direction of cultural exchange remains unclear. It is even possible that changes in Maya iconography and architecture reflected the impact of cultural intermediaries. The Putun Maya from the Tabasco region on the Gulf of Mexico coast had deep and sustained relationships with the Maya of Yucatan and the Toltecs. Culturally and linguistically distinct, the Putun Maya lived on the northwestern periphery of Classic-era Maya civilization. They had strong trade and political connections with central Mexico and spread elements of Toltec cultural practice. As their influence expanded, they established themselves at Chichen Itza. It is also possible that a small number of Toltec mercenaries reinforced this expansion and contributed to the transmission of central Mexican cultural characteristics.

Chichen Itza was governed by a council or, perhaps, a multiple kingship form of government. The city’s rulers exercised economic and political influence over a wide area, imposing tribute requirements on weaker neighbors by military expansion. Although the reasons are not yet clear, it is known that Chichen Itza experienced significant population loss after 1100 a.d. and was conquered militarily around 1221 a.d. Following this catastrophe, the city retained a small population and may have remained a religious pilgrimage site.

By the end of the thirteenth century, a successor people, the Itza, had come to exercise political and economic authority across much of Yucatan. The origin of the Itza is unclear. As their name suggests, they claimed to be the people of Chichen Itza. Their elite claimed descent from the Toltecs and were linguistically distinct from the region’s original population. It seems more likely that they were related in some way to the Putun Maya.

The Itza eventually probably established the important city of Mayapan, but many Maya groups remained independent. At its peak, Mayapan had a population of approximately 15,000. The size of the city’s population and the quality of its construction were far inferior to that of either the major Classic centers, like Tikal, or Postclassic Chichen Itza. Unlike the major Classic period cities that had served as centers for agricultural and craft production and as markets, Mayapan served as the capital of a regional confederation that compelled defeated peoples to pay tribute. This oppressive economic system probably provoked the warfare and rebellion that led to the end of Itza domination and the destruction of Mayapan about 1450 a.d. The Itza persisted, despite these reversals, continuing an independent existence in the Peten region of Guatemala until defeated by a Spanish military force in 1697.

From the fall of Mayapan until the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, the Maya returned to the pattern of dispersed political authority. During this

final period, towns of modest size, some with no more than 500 inhabitants, exercised control over a more dispersed and more rural population than had been the case in earlier eras. The cycles of expansion and collapse experienced by Chichen Itza imitated in many ways the rise and fall of important Maya centers during the Classic period. Although no powerful central authority existed in Maya regions when the Spanish arrived, Maya peoples retained their vitality and sustained essential elements of the cultural legacy inherited from their ancestors.

the aztec

When the Spaniards reached central Mexico in 1519, the state created by the Mexica and their Nahuatl-speaking allies—now commonly referred to jointly as the Aztec—was at the height of its power. Only the swiftness of their defeat exceeded the rapidity with which the Aztec had risen to prominence. For the century before the arrival of Cortés, they were unquestionably the most powerful political force in Mesoamerica.

Among the numerous nomadic and warlike peoples who pushed south toward central Mexico in the wake of the Toltec state’s collapse were the Mexica, one of many aggressive invading bands from the north that contemporary Nahuatl speakers referred to as Chichimec. Ultimately the most powerful, the Mexica adopted elements of the political and social forms they found among the advanced urbanized agriculturalists. After 1246 this emerging Chichimec elite forged a dynastic link with the surviving Toltec aristocracy of Culhuacan. This infusion of the northern invaders invigorated the culture of central Mexico and eventually led to a new period of political dynamism. The civilization that resulted from this cultural exchange, however, was more militaristic and violent than that of its predecessors.

The Mexica became important participants in the conflicts of the Valley of Mexico while the city of Atzcapotzalco was the dominant political power. Valued for their military prowess and despised for their cultural backwardness, Mexica warriors served as mercenaries. They initially received permission to settle in Chapultepec, now a beautiful park in Mexico City, but jealous and fearful neighbors drove them out. With the acquiescence of their Tepanec overlords in Atzcapotzalco, the Mexica then moved to a small island in the middle of Lake Texcoco where they could more easily defend themselves from attack. Here in 1325 or soon afterward they began to build their capital of Tenochtitlan. Despite their improved reputation, they continued for nearly a century as part-time warriors and tributaries of Atzcapotzalco.

By 1376 the Aztec were politically, socially, and economically organized like their neighbors as altepetl, complex regional ethnic states, each with a hereditary ruler, market, and temple dedicated to a patron deity. Altepetl were, in turn, typically made up of four or more calpulli, which also had their own subrulers, deities, and temples. These subdivisions originally may have been kinship based, but by the fourteenth century they functioned primarily to distribute land among their members and to collect and distribute tribute. The ethnic group called the Mexica had only two altepetl—the dominant Tenochca and the less powerful Tlatelolca.

The Mexica’s first king (tlatoani), Acamapichtli, claimed descent from the Toltec dynasty of Tula. After a period of consolidation, the new state undertook an ambitious and successful campaign of military expansion. Under Itzcoatl, the ruler from 1426 to 1440, the Mexica allied with two other city-states, Texcoco and Tlacopan, located on the shores of Lake Texcoco. In a surprise attack the Triple Alliance conquered the city of Atzcapotzalco in 1428 and consolidated control over much of the valley. During the rule of Moctezuma I (Motecuhzoma in Nahuatl) from 1440 to 1468, the Mexica gained ascendancy over their two allies, pushed outward from the valley, and established control over much of central Mexico. Following an interlude of weaker, less effective rulers, serious expansion resumed during the reign of Ahuitzotl from 1486 to 1502, and Aztec armies conquered parts of Oaxaca, Guatemala, and the Gulf coast. By the early sixteenth century, few pockets of unconquered peoples, principally the Tarascans of Michoacán and the Tlaxcalans of Puebla, remained in central Mexico.

When Moctezuma II took the throne in 1502 he inherited a society that in less than a century had risen from obscurity to political hegemony over a vast region. Tenochtitlan had a population of several hundred thousand persons, many of them immigrants, and the whole Valley of Mexico was home to perhaps 1.5 million. Social transformation accompanied this rapid expansion of political control and demographic growth. Before installing their first tlatoani, Mexica society had a relatively egalitarian structure based within the calpulli. Calpulli leaders, in addition to managing land administration and tribute responsibilities, supervised the instruction of the young, organized religious rituals, and provided military forces when called upon. Mexica calpulli resident in Tenochtitlan were primarily associated with artisan production rather than agriculture. The ability of a calpulli to redistribute land held jointly by its members was more important to rural and semirural areas than to urban centers. There also were noteworthy differences in wealth, prestige, and power within and among calpulli. The calpulli’s leader, however—most typically elected from the same family—handled the local judicial and administrative affairs with the advice of a council of elders.

After the Triple Alliance conquered Atzcapotzalco—the critical event in the evolution of the Mexica and the Aztec Empire—Itzcoatl removed the right of selecting future rulers from the calpulli and altepetl councils and gave it to his closest advisers, the newly established “Council of Four” from which his successors would be selected. The power and independence of the ruler continued to expand as triumphant armies added land and tribute to the royal coffers. In the late fifteenth century the ruler also served as high priest: Moctezuma II took the final step by associating his person with Huitzilopochtli, the Mexica’s most important deity.

Among the Aztec in general was a hereditary class of nobles called the pipiltin, who received a share of the lands and tribute from the conquered areas, the amount apparently related to their administrative position and rank. They staffed the highest military positions, the civil bureaucracy, and the priesthood. Their sons went to schools to prepare them for careers of service to the state. Noblemen had one principal wife and numerous concubines. This polygyny resulted in a

Another Random Scribd Document with Unrelated Content

LA CONFESSION D'UNE JEUNE FILLE

«Les désirs des sens nous entraînent çà et là, mais l'heure passée, que rapportez-vous? des remords de conscience et de la dissipation d'esprit. On sort dans la joie et souvent on revient dans la tristesse, et les plaisirs du soir attristent le matin. Ainsi la joie des sens flatte d'abord, mais à la fin elle blesse et elle tue.»

(ImitationdeJésus-Christ, Livre I, c. XVIII.)

I Parmi l'oubli qu'on cherche aux fausses allégresses. Revient plus virginal à travers

les ivresses, Le doux parfum mélancolique du lilas.

(Henri de Régnier.)

Enfin la délivrance approche. Certainement j'ai été maladroite, j'ai mal tiré, j'ai failli me manquer. Certainement il aurait mieux valu mourir du premier coup, mais enfin on n'a pas pu extraire la balle et les accidents au cœur ont commencé. Cela ne peut plus être bien long. Huit jours pourtant! cela peut encore durer huit jours! pendant lesquels je ne pourrai faire autre chose que m'efforcer de ressaisir l'horrible enchaînement. Si je n'étais pas si faible, si j'avais assez de volonté pour me lever, pour partir, je voudrais aller mourir aux Oublis, dans le parc où j'ai passé tous mes étés jusqu'à quinze ans. Nul lieu n'est plus plein de ma mère, tant sa présence, et son absence plus encore, l'imprégnèrent de sa personne. L'absence n'est-elle pas pour qui aime la plus certaine, la plus efficace, la plus vivace, la plus indestructible, la plus fidèle des présences?

Ma mère m'amenait aux Oublis à la fin d'avril, repartait au bout de deux jours, passait deux jours encore au milieu de mai, puis revenait me chercher dans la dernière semaine de juin. Ses venues si courtes étaient la chose la plus douce et la plus cruelle. Pendant ces deux jours elle me prodiguait des tendresses dont habituellement, pour m'endurcir et calmer ma sensibilité maladive, elle était très avare. Les deux soirs qu'elle passait aux Oublis, elle venait me dire bonsoir dans mon lit, ancienne habitude qu'elle avait perdue, parce que j'y trouvais trop de plaisir et trop de peine, que je ne m'endormais plus à force de la rappeler pour me dire bonsoir encore, n'osant plus à la fin, n'en ressentant que davantage le besoin passionné, inventant toujours de nouveaux prétextes, mon oreiller brûlant à retourner, mes pieds gelés qu'elle seule pourrait réchauffer dans ses mains... Tant de doux moments recevaient une douceur de plus de ce que je sentais que c'étaient ceux-là où ma mère était véritablement elle-même et que son habituelle froideur devait lui coûter beaucoup. Le jour où elle repartait, jour de désespoir où je m'accrochais à sa robe jusqu'au wagon, la suppliant de m'emmener à Paris avec elle, je démêlais très bien le sincère au milieu du feint, sa

tristesse qui perçait sous ses reproches gais et fâchés par ma tristesse «bête, ridicule» qu'elle voulait m'apprendre à dominer, mais qu'elle partageait. Je ressens encore mon émotion d'un de ces jours de départ (juste cette émotion intacte, pas altérée par le douloureux retour d'aujourd'hui) d'un de ces jours de départ où je fis la douce découverte de sa tendresse si pareille et si supérieure à la mienne. Comme toutes les découvertes, elle avait été pressentie, devinée, mais les faits semblaient si souvent y contredire! Mes plus douces impressions sont celles des années où elle revint aux Oublis, rappelée parce que j'étais malade. Non seulement elle me faisait une visite de plus sur laquelle je n'avais pas compté, mais surtout elle n'était plus alors que douceur et tendresse longuement épanchées sans dissimulation ni contrainte. Même dans ce temps-là où elles n'étaient pas encore adoucies, attendries par la pensée qu'un jour elles viendraient à me manquer, cette douceur, cette tendresse étaient tant pour moi que le charme des convalescences me fut toujours mortellement triste: le jour approchait où je serais assez guérie pour que ma mère put repartir, et jusque-là je n'étais plus assez souffrante pour qu'elle ne reprît pas les sévérités, la justice sans indulgence d'avant.

Un jour, les oncles chez qui j'habitais aux Oublis m'avaient caché que ma mère devait arriver, parce qu'un petit cousin était venu passer quelques

heures avec moi, et que je ne me serais pas assez occupée de lui dans l'angoisse joyeuse de cette attente. Cette cachotterie fut peut-être la première des circonstances indépendantes de ma volonté qui furent les complices de toutes les dispositions pour le mal que, comme tous les enfants de mon âge, et pas plus qu'eux alors, je portais en moi. Ce petit cousin qui avait quinze ans—j'en avais quatorze—était déjà très vicieux et m'apprit des choses qui me firent frissonner aussitôt de remords et de volupté. Je goûtais à l'écouter, à laisser ses mains caresser les miennes, une joie empoisonnée à sa source même; bientôt j'eus la force de le quitter et je me sauvai dans le parc avec un besoin fou de ma mère que je savais, hélas! être à Paris, l'appelant partout malgré moi par les allées. Tout à coup, passant devant une charmille, je l'aperçus sur un banc, souriante et m'ouvrant les bras. Elle releva son voile pour m'embrasser, je me précipitai contre ses joues en fondant en larmes; je pleurai longtemps en lui racontant toutes ces vilaines choses qu'il fallait l'ignorance de mon âge pour lui dire et qu'elle sut écouter divinement, sans les comprendre, diminuant leur importance avec une bonté qui allégeait le poids de ma conscience. Ce poids s'allégeait, s'allégeait; mon âme écrasée, humiliée montait de plus en plus légère et puissante, débordait, j'étais tout âme. Une divine douceur émanait de ma mère et de mon innocence revenue. Je sentis bientôt sous mes narines une odeur aussi pure et aussi fraîche. C'était un lilas dont une branche cachée par l'ombrelle de ma mère était déjà fleurie et qui, invisible, embaumait. Tout en haut des arbres, les oiseaux chantaient de toutes leurs forces. Plus haut, entre les cimes vertes, le ciel était d'un bleu si profond qu'il semblait à peine l'entrée d'un ciel où l'on pourrait monter sans fin. J'embrassai ma mère. Jamais je n'ai retrouvé la douceur de ce baiser. Elle repartit le lendemain et ce départ-là fut plus cruel que tous ceux qui avaient précédé. En même temps que la joie il me semblait que c'était maintenant que j'avais une fois péché, la force, le soutien nécessaires qui m'abandonnaient.

Toutes ces séparations m'apprenaient malgré moi ce que serait l'irréparable qui viendrait un jour, bien que jamais à cette époque je n'aie sérieusement envisagé la possibilité de survivre à ma mère. J'étais décidée à me tuer dans la minute qui suivrait sa mort. Plus tard, l'absence porta d'autres enseignements plus amers encore, qu'on s'habitue à l'absence, que c'est la plus grande diminution de soi-même,

la plus humiliante souffrance de sentir qu'on n'en souffre plus. Ces enseignements d'ailleurs devaient être démentis dans la suite. Je repense surtout maintenant au petit jardin où je prenais avec ma mère le déjeuner du matin et où il y avait d'innombrables pensées. Elles m'avaient toujours paru un peu tristes, graves comme des emblèmes, mais douces et veloutées, souvent mauves, parfois violettes, presque noires, avec de gracieuses et mystérieuses images jaunes, quelquesunes entièrement blanches et d'une frôle innocence. Je les cueille toutes maintenant dans mon souvenir, ces pensées, leur tristesse s'est accrue d'avoir été comprises, la douceur de leur velouté est à jamais disparue.

Comment toute cette eau fraîche île souvenirs a-t-elle pu jaillir encore une fois et couler dans mon âme impure d'aujourd'hui sans s'y souiller? Quelle vertu possède cette matinale odeur de lilas pour traverser tant de vapeurs fétides sans s'y mêler et s'y affaiblir? Hélas! en même temps qu'en moi, c'est bien loin de moi, c'est hors de moi que mon âme de quatorze ans se réveille encore. Je sais bien qu'elle n'est plus mon âme et qu'il ne dépend plus de moi qu'elle la redevienne. Alors pourtant je ne croyais pas que j'en arriverais un jour à la regretter. Elle n'était que pure, j'avais à la rendre forte et capable dans l'avenir des plus hautes tâches. Souvent aux Oublis, après avoir été avec ma mère au bord de l'eau pleine des jeux du soleil et des poissons, pendant les chaudes heures du jour,—ou le matin et le soir me promenant avec elle dans les champs, je rêvais avec confiance cet avenir qui n'était jamais assez beau au gré de son amour, de mon désir de lui plaire, et des puissances sinon de volonté, au moins d'imagination et de sentiment qui s'agitaient en moi, appelaient tumultueusement la destinée où elles se réaliseraient et frappaient à coups répétés à la cloison de mon cœur comme pour l'ouvrir et se précipiter hors de moi, dans la vie. Si, alors, je sautais de toutes mes forces, si j'embrassais mille fois ma mère, courais au loin en avant comme un jeune chien, ou restée indéfiniment en arrière à cueillir des coquelicots et des bleuets, les rapportais en poussant des cris, c'était moins pour la joie de la promenade elle-même et de ces cueillettes que pour épancher mon bonheur de sentir en moi toute cette vie prête à

jaillir, à s'étendre à l'infini, dans des perspectives plus vastes et plus enchanteresses que l'extrême horizon des forêts et du ciel que j'aurais voulu atteindre d'un seul bond. Bouquets de bleuets, de trèfles et de coquelicots, si je vous emportais avec tant d'ivresse, les yeux ardents, toute palpitante, si vous me faisiez rire et pleurer, c'est que je vous composais avec toutes mes espérances d'alors, qui maintenant, comme vous, ont séché, ont pourri, et sans avoir fleuri comme vous, sont retournées à la poussière.

Ce qui désolait ma mère, c'était mon manque de volonté. Je faisais tout par l'impulsion du moment. Tant qu'elle fut toujours donnée par l'esprit ou par le cœur, ma vie, sans être tout à fait, bonne, ne fut pourtant pas vraiment mauvaise. La réalisation de tous mes beaux projets de travail, de calme, de raison, nous préoccupait par-dessus tout, ma mère et moi, parce que nous sentions, elle plus distinctement, moi confusément, mais

avec beaucoup de force, qu'elle ne serait que l'image projetée dans ma vie de la création par moi-même et en moi-même de cette volonté qu'elle avait conçue et couvée. Mais toujours je l'ajournais au lendemain. Je me donnais du temps, je me désolais parfois de le voir passer, mais il y en avait encore tant devant moi! Pourtant j'avais un peu peur, et sentais vaguement que l'habitude de me passer ainsi de vouloir commençait à peser sur moi déplus en plus fortement à mesure qu'elle prenait plus d'années, me doutant tristement que les choses ne changeraient pas tout d'un coup, et qu'il ne fallait guère compter, pour transformer ma vie et créer ma volonté, sur un miracle qui ne m'aurait coûté aucune peine. Désirer avoir de la volonté n'y suffisait pas. Il aurait fallu précisément ce que je ne pouvais sans volonté: le vouloir. III

Et le vent furibond de la concupiscence

Fait claquer votre chair ainsi qu'un vieux drapeau.

(Baudelaire.)

Pendant ma seizième année, je traversai une crise qui me rendit souffrante. Pour me distraire, on me fit débuter dans le monde. Des jeunes gens prirent l'habitude de venir me voir. Un d'entre eux était pervers et méchant. Il avait des manières à la fois douces et hardies. C'est de lui que je devins amoureuse. Mes parents l'apprirent et ne brusquèrent rien pour ne pas me faire trop de peine. Passant tout le temps où je ne le voyais pas à penser à lui, je finis par m'abaisser en lui ressemblant autant que cela m'était possible. Il m'induisit à mal faire presque par surprise, puis m'habitua à laisser s'éveiller en moi de mauvaises pensées auxquelles je n'eus pas une volonté à opposer, seule puissance capable de les faire rentrer dans l'ombre infernale d'où elles sortaient. Quand l'amour finit, l'habitude avait pris sa place et il ne

manquait pas de jeunes gens immoraux pour l'exploiter. Complices de mes fautes, ils s'en faisaient aussi les apologistes en face de ma conscience. J'eus d'abord des remords atroces, je fis des aveux qui ne furent pas compris. Mes camarades me détournèrent d'insister auprès de mou père. Ils me persuadaient lentement que toutes les jeunes filles faisaient de même et que les parents feignaient seulement de l'ignorer. Les mensonges que j'étais sans cesse obligée de faire, mon imagination les colora bientôt des semblants d'un silence qu'il convenait de garder sur une nécessité inéluctable. À ce moment je ne vivais plus bien; je rêvais, je pensais, je sentais encore.

Pour distraire et chasser tous ces mauvais désirs, je commençai à aller beaucoup dans le monde. Ses plaisirs desséchants m'habituèrent à vivre dans une compagnie perpétuelle, et je perdis avec le goût de la solitude le secret des joies que m'avaient données jusque-là la nature et l'art. Jamais je n'ai été si souvent au concert que dans ces années-là. Jamais, tout occupée au désir d'être admirée dans une loge élégante, je n'ai senti moins profondément la musique. J'écoutais et je n'entendais rien. Si par hasard j'entendais, j'avais cessé de voir tout ce que la musique sait dévoiler. Mes promenades aussi avaient été comme frappées de stérilité. Les choses qui autrefois suffisaient à me rendre heureuse pour toute la journée, un peu de soleil jaunissant l'herbe, le parfum que les feuilles mouillées laissent s'échapper avec les dernières gouttes de pluie, avaient perdu comme moi leur douceur et leur gaieté. Les bois, le ciel, les eaux semblaient se détourner de moi, et si, restée seule avec eux face à face, je les interrogeais anxieusement, ils ne murmuraient plus ces réponses vagues qui me ravissaient autrefois. Les hôtes divins qu'annoncent les voix des eaux, des feuillages et du ciel daignent visiter seulement les cœurs qui, en habitant en eux-mêmes, se sont purifiés.

C'est alors qu'à la recherche d'un remède inverse et parce que je n'avais pas le courage de vouloir le véritable qui était si près, et hélas! si loin de moi, en moi-même, je me laissai de nouveau aller aux plaisirs coupables, croyant ranimer par là la flamme éteinte par le monde. Ce fut en vain. Retenue par le plaisir de plaire, je remettais de jour en jour la décision définitive, le choix, l'acte vraiment libre, l'option pour la solitude. Je ne renonçai pas à l'un de ces deux vices pour l'autre. Je les mêlai. Que disje? chacun se chargeant de briser tous les obstacles de pensée, de sentiment, qui auraient arrêté l'autre, semblait aussi l'appeler. J'allais

dans le monde pour me calmer après une faute, et j'en commettais une autre dès que j'étais calme. C'est à ce moment terrible, après l'innocence perdue, et avant le remords d'aujourd'hui, à ce moment où de tous les moments de ma vie j'ai le moins valu, que je fus le plus appréciée de tous. On m'avait jugée une petite fille prétentieuse et folle; maintenant, au contraire, les cendres de mon imagination étaient au goût du monde qui s'y délectait. Alors que je commettais envers ma mère le plus grand des crimes, on me trouvait à cause de mes façons tendrement respectueuses avec elle, le modèle des filles. Après le suicide de ma pensée, on admirait mon intelligence, on raffolait de mon esprit. Mon imagination desséchée, ma sensibilité tarie, suffisaient à la soif des plus altérés de vie spirituelle, tant cette soif était factice, et mensongère comme la source où ils croyaient l'étancher! Personne d'ailleurs ne soupçonnait le crime secret de ma vie, et je semblais à tous la jeune fille idéale. Combien de parents dirent alors à ma mère que si ma situation eût été moindre et s'ils avaient pu songer à moi, ils n'auraient pas voulu d'autre femme pour leur fils! Au fond de ma conscience oblitérée, j'éprouvais pourtant de ces louanges indues une honte désespérée; elle n'arrivait pas jusqu'à la surface, et j'étais tombée si bas que j'eus l'indignité de les rapporter en riant aux complices de mes crimes. IV

«À quiconque a perdu ce qui ne se retrouve jamais... jamais!»

(Baudelaire.)

L'hiver de ma vingtième année, la santé de ma mère, qui n'avait jamais été vigoureuse, fut très ébranlée. J'appris qu'elle avait le cœur malade, sans gravité d'ailleurs, mais qu'il fallait lui éviter tout ennui. Un de mes oncles me dit que ma mère désirait me voir me marier. Un devoir précis, important se présentait à moi. J'allais pouvoir prouver à ma mère combien je l'aimais. J'acceptai la première demande qu'elle me transmit

en l'approuvant, chargeant ainsi, à défaut de volonté, la nécessité, de me contraindre à changer de vie. Mon fiancé était précisément le jeune homme qui, par son extrême intelligence, sa douceur et son énergie, pouvait avoir sur moi la plus heureuse influence. Il était, de plus, décidé à habiter avec nous. Je ne serais pas séparée de ma mère, ce qui eût été pour moi la peine la plus cruelle.

Alors j'eus le courage de dire toutes mes fautes à mon confesseur. Je lui demandai si je devais le même aveu à mon fiancé. Il eut la pitié de m'en détourner, mais me fit prêter le serment de ne jamais retomber dans mes erreurs et me donna l'absolution. Les fleurs tardives que la joie fit éclore dans mon cœur que je croyais à jamais stérile portèrent des fruits. La grâce de Dieu, la grâce de la jeunesse,—où l'on voit tant de plaies se refermer d'elles-mêmes par la vitalité de cet âge—m'avaient guérie. Si, comme l'a dit saint Augustin, il est plus difficile de redevenir chaste que de l'avoir été, je connus alors une vertu difficile. Personne ne se doutait que je valais infiniment mieux qu'avant et ma mère baisait chaque jour mon front qu'elle n'avait jamais cessé de croire pur sans savoir qu'il était régénéré. Bien plus, on me fit à ce moment, sur mon attitude distraite, mon silence et ma mélancolie dans le monde, des reproches injustes. Mais je ne m'en fâchais pas: le secret qui était entre moi et ma conscience satisfaite me procurait assez de volupté. La convalescence de mon âme—qui me souriait maintenant sans cesse avec un visage semblable à celui de ma mère et me regardait avec un air de tendre reproche à travers ses larmes qui séchaient—était d'un charme et d'une langueur infinis. Oui, mon âme renaissait à la vie. Je ne comprenais pas moi-même comment j'avais pu la maltraiter, la faire souffrir, la tuer presque. Et je remerciais Dieu avec effusion de l'avoir sauvée à temps.

C'est l'accord de cette joie profonde et pure avec la fraîche sérénité du ciel que je goûtais le soir où tout s'est accompli. L'absence de mon fiancé, qui était allé passer deux jours chez sa sœur, la présence à dîner du jeune homme qui avait la plus grande responsabilité dans mes fautes passées, ne projetaient pas sur cette limpide soirée de mai la plus légère tristesse. Il n'y avait pas un nuage au ciel qui se reflétait exactement dans mon cœur. Ma mère, d'ailleurs, comme s'il y avait ou entre elle et mon âme, malgré qu'elle fût dans une ignorance absolue de mes fautes, une solidarité mystérieuse, était à peu près guérie. «Il faut la ménager quinze jours, avait dit le médecin, et après cela il n'y aura plus de

rechute possible!» Ces seuls mots étaient pour moi la promesse d'un avenir de bonheur dont la douceur me faisait fondre en larmes. Ma mère avait ce soir-là une robe plus élégante que de coutume, et, pour la première fois depuis la mort de mon père, déjà ancienne pourtant de dix ans, elle avait ajouté un peu de mauve à son habituelle robe noire. Elle était toute confuse d'être ainsi habillée comme quand elle était plus jeune, et triste et heureuse d'avoir fait violence à sa peine et à son deuil pour me faire plaisir et fêter ma joie. J'approchai de son corsage un œillet rose qu'elle repoussa d'abord, puis qu'elle attacha, parce qu'il venait de moi, d'une main un peu hésitante, honteuse. Au moment où on allait se mettre à table, j'attirai près de moi vers la fenêtre son visage délicatement reposé de ses souffrances passées, et je l'embrassai avec passion. Je m'étais trompée en disant que je n'avais jamais retrouvé la douceur du baiser aux Oublis. Le baiser de ce soir-là fut aussi doux qu'aucun autre. Ou plutôt ce fut le baiser même des Oublis qui, évoqué par l'attrait d'une minute pareille, glissa doucement du fond du passé et vint se poser entre les joues de ma mère encore un peu pâles et mes lèvres.

On but à mon prochain mariage. Je ne buvais jamais que de l'eau à cause de l'excitation trop vive que le vin causait à mes nerfs. Mon oncle déclara qu'à un moment comme celui-là, je pouvais faire une exception. Je revois très bien sa figure gaie en prononçant ces paroles stupides... Mon Dieu! mon Dieu! j'ai tout confessé avec tant de calme, vais-je être obligée de m'arrêter ici? Je ne vois plus rien! Si... mon oncle dit que je pouvais bien à un moment comme celui-là faire une exception. Il me regarda en riant en disant cela, je bus vite avant d'avoir regardé ma mère dans la crainte qu'elle ne me le défendit. Elle dit doucement: «On ne doit jamais faire une place au mal, si petite qu'elle soit.» Mais le vin de Champagne était si frais que j'en bus encore deux autres verres. Ma tête était devenue très lourde, j'avais à la fois besoin de me reposer et de dépenser mes nerfs. On se levait de table: Jacques s'approcha de moi et me dit en me regardant fixement:

—Voulez-vous venir avec moi; je voudrais vous montrer des vers que j'ai faits.

Ses beaux yeux brillaient doucement dans ses joues fraîches, il releva lentement ses moustaches avec sa main. Je compris que je me perdais

et je fus sans force pour résister. Je dis toute tremblante:

—Oui, cela me fera plaisir.

Ce fut en disant ces paroles, avant même peut-être, en buvant le second verre de vin de Champagne que je commis l'acte vraiment responsable, l'acte abominable. Après cela, je ne fis plus que me laisser faire. Nous avions fermé à clef les deux portes, et lui, son haleine sur mes joues, m'étreignait, ses mains furetant le long de mon corps. Alors tandis que le plaisir me tenait de plus en plus, je sentais s'éveiller, au fond de mon cœur, une tristesse et une désolation infinies; il me semblait que je faisais pleurer l'âme de ma mère, l'âme de mon ange gardien, l'âme de Dieu. Je n'avais jamais pu lire sans des frémissements d'horreur le récit des tortures que des scélérats font subir à des animaux, à leur propre femme, à leurs enfants; il m'apparaissait confusément maintenant que dans tout acte voluptueux et coupable il y a autant de férocité de la part du corps qui jouit, et qu'en nous autant de bonnes intentions, autant d'anges purs sont martyrisés et pleurent.

Bientôt mes oncles auraient fini leur partie de cartes et allaient revenir. Nous allions les devancer, je ne faillirais plus, c'était la dernière fois... Alors, au-dessus de la cheminée, je me vis dans la glace. Toute cette vague angoisse de mon âme n'était pas peinte sur ma figure, mais toute elle respirait, des yeux brillants aux joues enflammées et à la bouche offerte, une joie sensuelle, stupide et brutale. Je pensais alors à l'horreur de quiconque m'ayant vue tout à l'heure embrasser ma mère avec une mélancolique tendresse, me verrait ainsi transfigurée en bête. Mais aussitôt se dressa dans la glace, contre ma figure, la bouche de Jacques, avide sous ses moustaches. Troublée jusqu'au plus profond de moimême, je rapprochai ma tête de la sienne, quand en face de moi je vis, oui, je le dis comme cela était, écoutez-moi puisque je peux vous le dire, sur le balcon, devant la fenêtre, je vis ma mère qui me regardait hébétée. Je ne sais si elle a crié, je n'ai rien entendu, mais elle est tombée en arrière et est restée la tête prise entre les deux barreaux du balcon...

Ce n'est pas la dernière fois que je vous le raconte; je vous l'ai dit, je me suis presque manquée, je m'étais pourtant bien visée, mais j'ai mal tiré. Pourtant on n'a pas pu extraire la balle et les accidents au cœur ont commencé. Seulement je peux rester encore huit jours comme cela et je

ne pourrai cesser jusque-là de raisonner sur les commencements et de voir la fin. J'aimerais mieux que ma mère m'ait vu commettre d'autres crimes encore et celui-là même, mais qu'elle n'ait pas vu cette expression joyeuse qu'avait ma figure dans la glace. Non, elle n'a pu la voir... C'est une coïncidence... elle a été frappée d'apoplexie une minute avant de me voir... Elle ne l'a pas vue... Cela ne se peut pas! Dieu qui savait tout ne l'aurait pas voulu.

UN DINER EN VILLE

«Mais, Fundanius, qui partageait avec vous le bonheur de ce repas? je suis en peine de le savoir.»

(Horace.)

IHonoré était en retard; il dit bonjour aux maîtres de la maison, aux invités qu'il connaissait, fut présenté aux autres et on passa à table. Au bout de quelques instants, son voisin, un tout jeune homme, lui demanda de lui nommer et de lui raconter les invités. Honoré ne l'avait encore jamais rencontré dans le monde. Il était très beau. La maîtresse de la maison jetait à chaque instant sur lui des regards brûlants qui signifiaient assez pourquoi elle l'avait invité et qu'il ferait bientôt partie de sa société. Honoré sentit en lui une puissance future, mais sans envie, par bienveillance polie, se mit en devoir de lui répondre. Il regarda

autour de lui. En face deux voisins ne se parlaient pas: on les avait, par maladroite bonne intention, invités ensemble et placés l'un près de l'autre parce qu'ils s'occupaient tous les deux de littérature. Mais à cette première raison de se haïr, ils en ajoutaient une plus particulière. Le plus âgé, parent—doublement hypnotisé—de M. Paul Desjardins et de M. de Vogüé, affectait un silence méprisant à l'endroit du plus jeune, disciple favori de M. Maurice Barrès, qui le considérait à son tour avec ironie. La malveillance de chacun d'eux exagérait d'ailleurs bien contre son gré l'importance de l'autre, comme si l'on eût affronté le chef des scélérats au roi des imbéciles. Plus loin, une superbe Espagnole mangeait rageusement. Elle avait sans hésiter et en personne sérieuse sacrifié ce soir-là un rendez-vous à la probabilité d'avancer, en allant dîner dans une maison élégante, sa carrière mondaine. Et certes, elle avait beaucoup de chances d'avoir bien calculé. Le snobisme de madame Fremer était pour ses amies et celui de ses amies était pour elle comme une assurance mutuelle contre l'embourgeoisement. Mais le hasard avait voulu que madame Fremer écoulât précisément ce soir-là un stock de gens qu'elle n'avait pu inviter à ses dîners, à qui, pour des raisons différentes, elle tenait à faire des politesses, et qu'elle avait réunis presque pêle-mêle. Le tout était bien surmonté d'une duchesse, mais que l'Espagnole connaissait déjà et dont elle n'avait plus rien à tirer. Aussi échangeait-elle des regards irrités avec son mari dont on entendait toujours, dans les soirées, la voix gutturale dire successivement, en laissant entre chaque demande un intervalle de cinq minutes bien remplies par d'autres besognes: «Voudriez-vous me présenter au duc?—Monsieur le Duc, voudriez-vous me présenter à la Duchesse?—Madame la Duchesse, puisje vous présenter ma femme?» Exaspéré de perdre son temps, il s'était pourtant résigné à entamer la conversation avec son voisin, l'associé du maître de la maison. Depuis plus d'un an Fremer suppliait sa femme de l'inviter. Elle avait enfin cédé et l'avait dissimulé entre le mari de l'Espagnole et un humaniste. L'humaniste, qui lisait trop, mangeait trop. Il avait des citations et des renvois et ces deux incommodités répugnaient également à sa voisine, une noble roturière, madame Lenoir. Elle avait vite amené la conversation sur les victoires du prince de Buivres au Dahomey et disait d'une voix attendrie: «Cher enfant, comme cela me réjouit qu'il honore la famille!» En effet, elle était cousine des Buivres, qui, tous plus jeunes qu'elle, la traitaient avec la déférence que lui valaient son âge, son attachement à la famille royale, sa grande