Iciar de Águeda Martín

Academic Portfolio 2025

Edinburgh College of Arts

University of Edinburgh

European Master in Landscape Architecture (EMiLA) 1st year, 2nd semester

Introduction & conceptual framework

Individual work / ECA / Spring 2025

Latent forces

Group work / CTH / Fall 2021

Trans-Oikeôlogy

Group work / ETSAM-UPM / Summer 2023

Macro-farms

Individual work / ETSAM-UPM / Fall 2023

Guilleries-Savassona

Group work / UPC / Fall 2024

Conclusions

Individual work / ECA / Spring 2025

Madrid / Introduction & Conceptual framework

Gothemburg / Latent forces

Morfi / Trans-Oikeôlogy

Segovia / Macro-farms

Barcelona / Guilleries-Savassona

Edinburgh / Conclusions

“I developed a special interest towards spaces where there was lack of connection between the territories and the inhabitants, and how this disconnection was also related to a lack of agency and consequentially, it was affecting the identity of these areas”

even years ago, I started my academic journey, a journey that now has taken me to the field of landscape architecture, but one that did not begin so directly towards it. Back in Madrid, the city where I have been born and raised, I started my studies in architecture with the intention to learn about different disciplines from diverse fields of study, such as the arts, the history or the physics.

landscape architecture, where I believed I could develop conscious projects more aligned with my personal values and beliefs.

In the same multidisciplinary way that I understood architecture at the beginning of my studies, once I finished my degree, I was also feeling architecture was not only about building or construction, but that there was much more involved in any project. I understood architecture as a trans-disciplinary practice combined with many other disciplines such as urbanism, social studies, heritage... and of course landscape.

This holistic vision of the design and planning of spaces in different scales, contexts and with human or more than human agents was my turning point into

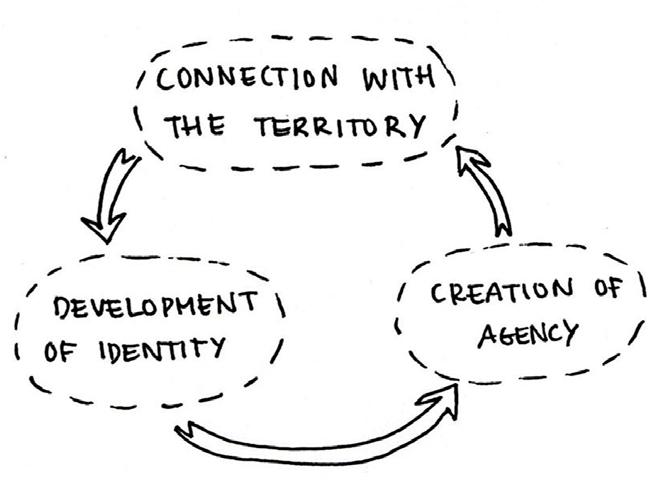

Looking back into my architecture studies’ years, through some of the experiences that I had, and some personal sensibilities towards certain topics that felt familiar to my context, I developed a special interest towards spaces where there was lack of connection between the territories and the inhabitants, and how this disconnection was also related to a lack of agency and consequentially, it was affecting the identity of these areas [Fig. 1].

Turning this idea around, I also became intrigued about the exploration of the development of identity to enable space valorisation and revalorization for unconventional, underestimated and forgotten landscapes, engaging in this way with the inhabitants, to empower them and create agency around the landscape that surround them achieving a longterm relationship between local actors and their landscapes [Fig. 2]

All these interests have been influenced by my architectural background and the concept of “placemaking” related to the 1970’s urban movement aiming for meeting and public spaces for communities in opposition to the top-down policies and tendencies of the time, that can still be reflected and recognized today.

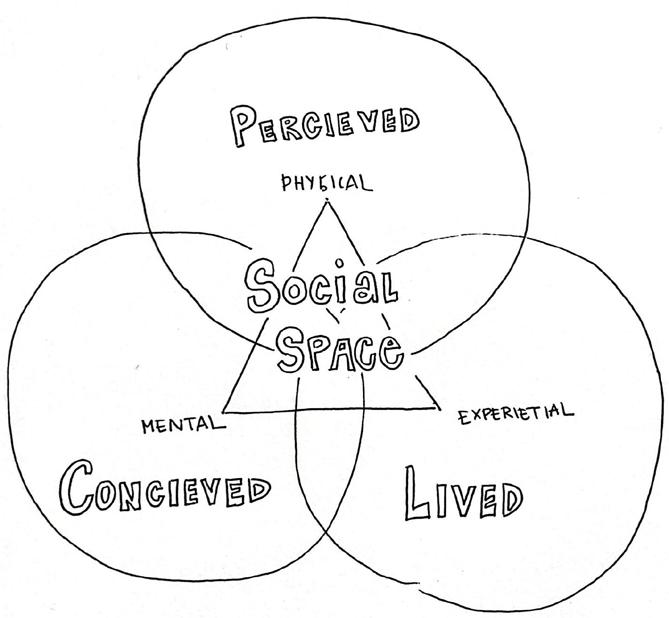

An influence present in my work through my architecture studies was Henri Lefebvre and the triad of space [Fig. 3] introduced in his book “The production of space”. In this book he states that social space is conformed of three dimensions. These are the perceived, conceived and lived dimensions of space, relating correspondingly to physical space, mental space, and experiential space. With any of these missing or lacking acknowledgement, incongruences can start emerging within the social space.

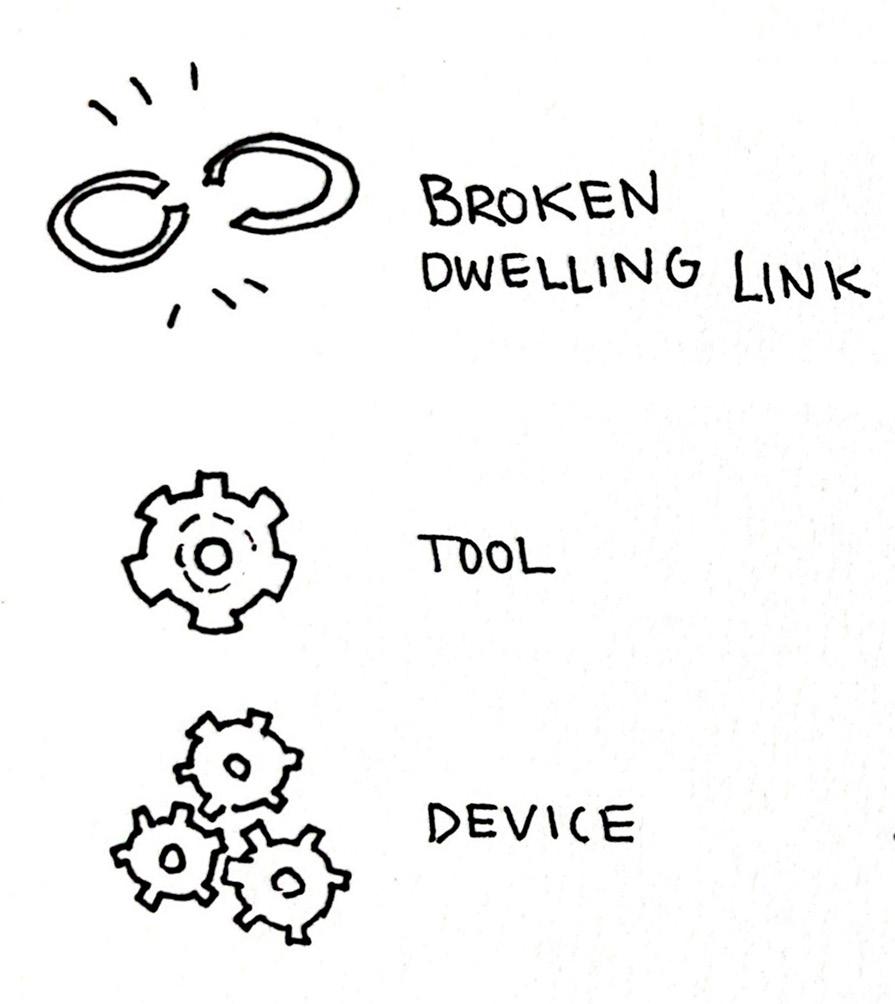

Throughout these concepts, I also came across the idea of the role of the architect or the landscape architect as a designer of tools and devices involving the inhabitants, leading to an iterative process that trough time could finally lead to this fostered feeling of identity.

To support all these ideas, I firstly had to further understand how I really see the landscape, framing it around theory and some of my personal thoughts...

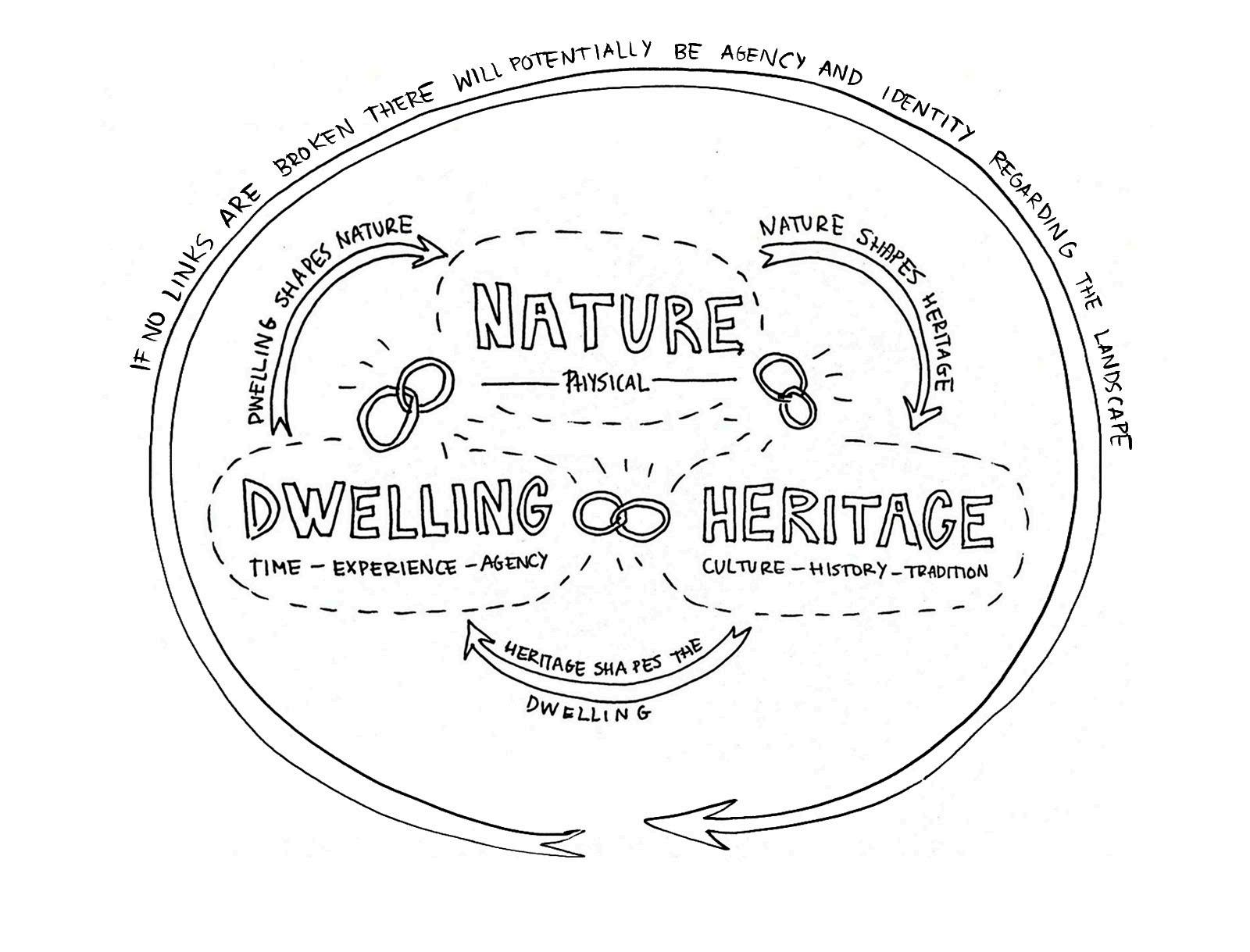

Supporting some of my personal thoughts around this vision of space made up of different dimensions, and the reflections made in Tim Ingold’s “The temporality of the landscape” and “Taking taskscape to task”, I started to understand the landscape as a space made as well of three different dimensions. These three dimensions can be argued to be the nature, the heritage, and the dwelling. The dimension of nature involves every physical aspect of the landscape, the

mountains, the rivers, the sun, the rain, the dew that forms in the mornings, etc… The dimension of heritage is composed of the history of the landscape. It can be all kinds of history, from the geological past that now shapes the territory, to the traditions that shapes the different cultures. Finally, the dimension of dwelling, the one where the experience is revealed, time is acknowledged, and identity is recognized. This is the dimension where the inhabitants of a landscape live and become agents of their territories. Relating to what Ingold argues, this last dimension of what I believe makes the landscape is what he names the taskscape (Ingold, 1993). This taskscape would be the array of any activities carried out by an agent in an environment or as part of his/her/ its normal business of life, or in other words, the constitutive acts of dwelling (Ingold, 1993). This dimension is the one that involves the beings, who are themselves agents and who reciprocally ‘act back’ in the process of their own dwelling (Ingold, 1993), and who can be humans, more-than-humans.

Figure 4, The dimensions of the landscape.

I can see the dwelling dimension as something inherently co-existential with the idea of landscape, as it recognises the fundamental temporality of the landscape itself. This condition of temporality is what makes the landscape perpetually under construction (Ingold, 1993), and what allow us, landscape architects, to engage with it in this endless process of becoming.

The way I understand these mentioned dimensions to be related is as links, related in a continuous and indivisible manner throughout space. The nature and the physical features would shape the heritage and the culture, which then shape the way agents dwell the landscape. In the same way, how inhabitants dwell the landscape will shape or re-shape the nature or physical dimension, and so on [Fig. 4]

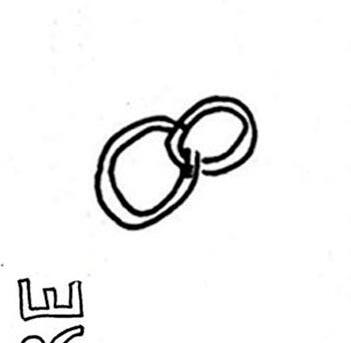

As in the social space, it is also important in every landscape project to understand the importance of each of these dimensions... In landscape architecture, from my personal perspective, this dwelling dimension is to be recognize, otherwise, these unconventional, underestimated and forgotten landscapes start emerging, and the links between dimensions breaks

“I can see the dwelling dimension as something inherently coexistential with the idea of landscape, as it recognises the fundamental temporality of the landscape itself.”

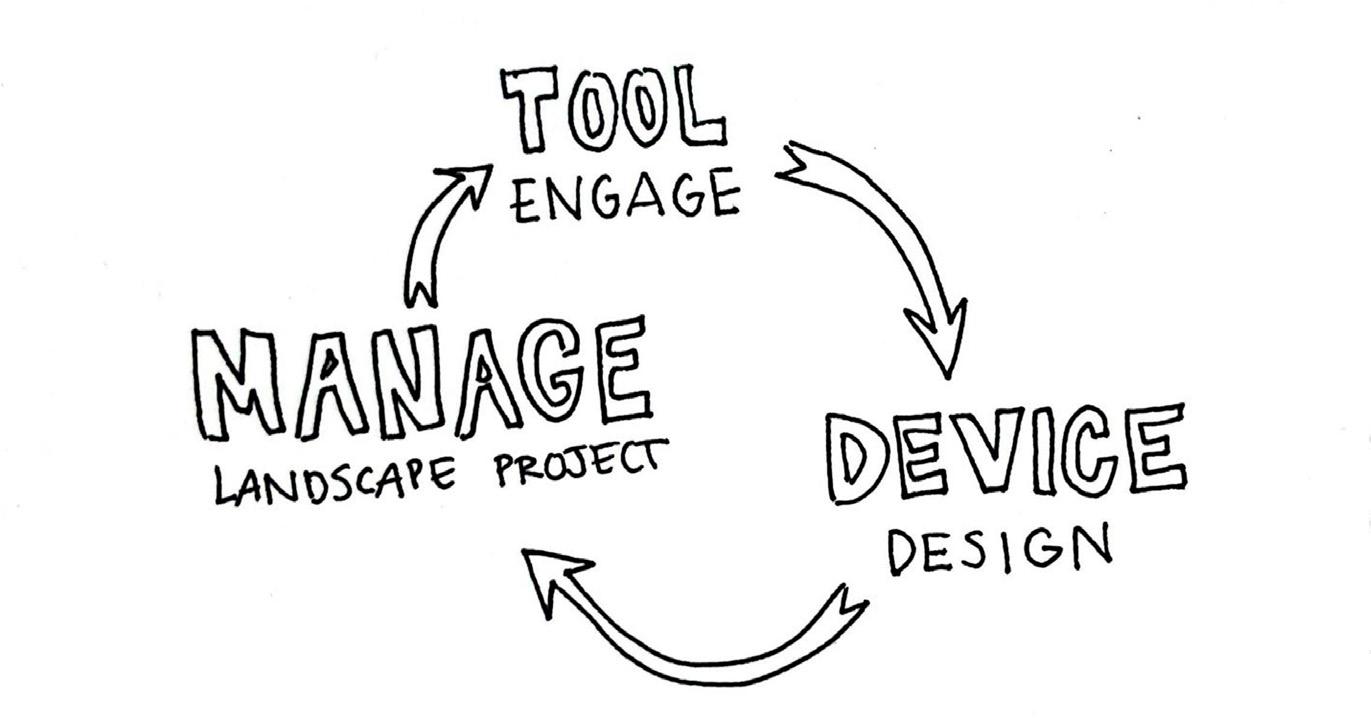

Going back to the idea of connection with the territory introduced in relation to my interest towards identity, the dimension of dwelling is key for this connection to happen, but the “dwelling link” can be broken [Fig. 5]. As I will build up next, the projects that I will highlight from my previous practice all have in common the realization that the dwelling link has been broken, due to different factors, like depopulation, potential depopulation or the ageing of the inhabitants.

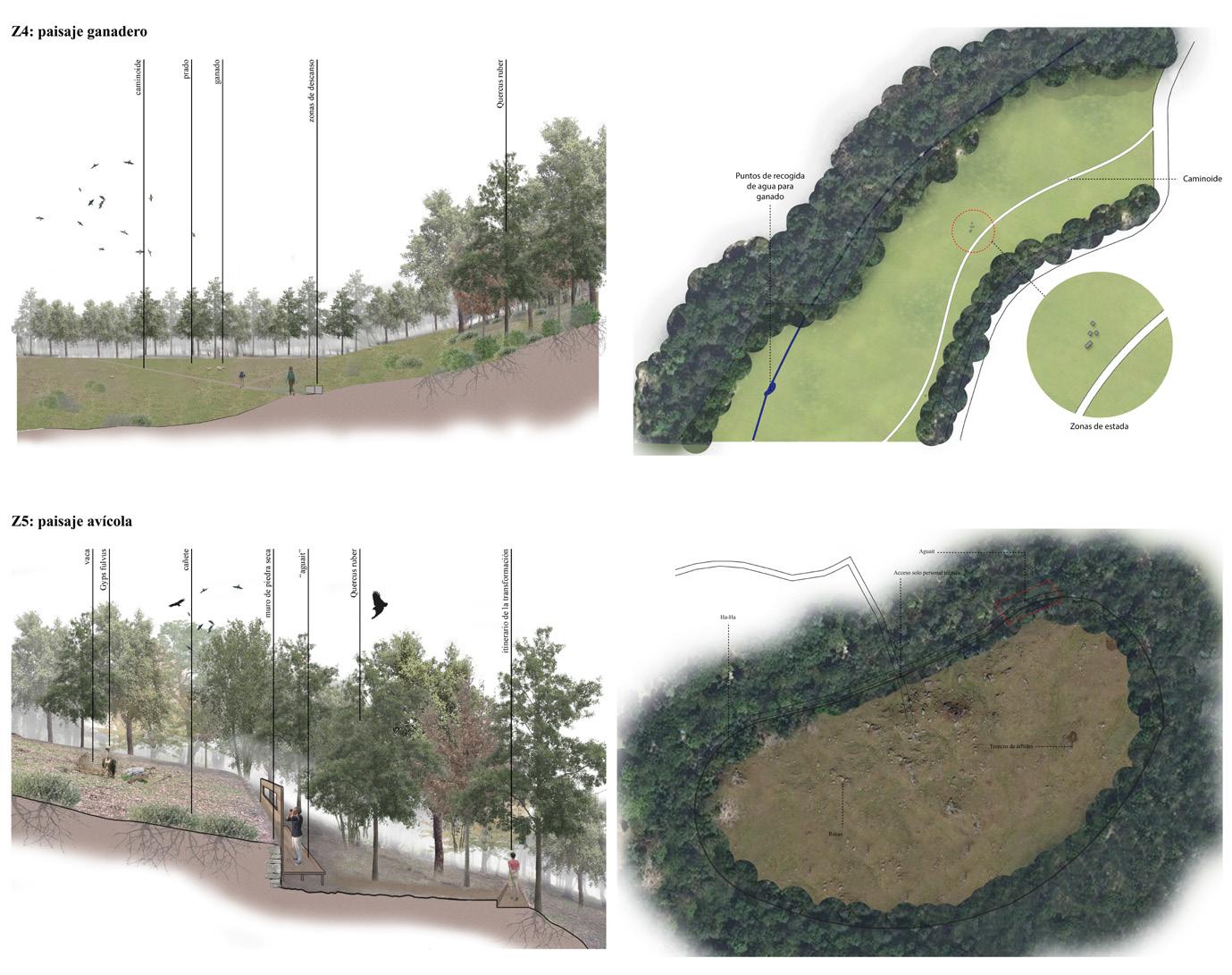

Is in this crucial link of the dwelling dimension where I believe that the landscape architects can develop the tools and devices to keep the agents connected to their territories and better design more resilient and engaging landscapes [Fig. 6]

Throughout the next chapters of this portfolio, I will present one by one three of the projects that I have developed during my architecture years, and that have taught me different tools to begin this agency, adding layers to the different iterations needed trough time to restore the connection between the inhabitants and their landscapes.

Finally, I will present my first landscape architecture project, where the time is fully acknowledged as the management of the landscape becomes the actual design, and I will reflect on how this project could have been improved using some of the previously explained tools.

“Is in this crucial link of the dwelling dimension where I believe that the landscape architects can develop the tools and devices to keep the agents connected to their territories and better design more resilient and engaging landscapes.”

“... inhabitants didn’t seem to relate space to the physical environment, space for them is the networks of people.”

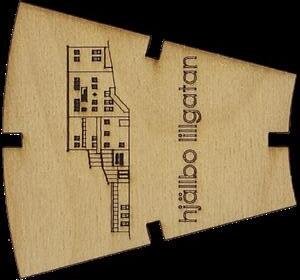

The first time I worked with this idea of the dimensions of space, was during my exchange year in Sweden, in the city of Gothenburg, more specifically in the neighbourhood of Hjällbo. This was a social space where inhabitants were mainly first or second-generation immigrants (90% of the total population), coming from countries such as Somalia, Irek, Bosnia, Syria… and where the Swedish Million Programme (Miljonprogrammet) financed the construction of the whole area consisting of 2.600 apartments built between 1965 and 1969. At first sight, it seemed like any other residential area from the suburbs built during this period in Sweden, many green areas, open spaces, good transport, concrete buildings…, very disconnected to the preconceived image we had, made from media and prejudices [Figs. 1]. It was only when hearing the inhabitants when we started understanding the space.

The people from Hjällbo expressed that the current setup of the system was not adapted to channelling the innate resources in the area. The example they gave was the “Strategy for the development area Hjällbo: 2020-2030”, a 10-year plan that they felt was set without the inclusion of the inhabitants. They said that the legislation and policymaking was being shaped by distorted images in the media. It painted an image of Hjällbo where the physical buildings and blocks

were separated from the people inhabiting the area and the lives and culture that it holds. We noticed how the inhabitants didn’t seem to relate ”space” to the physical environment, ”space” for them was the networks of people. To understand the missing link, we used the briefly explained in the previous chapter ”Conceptual framework”, Lefebvre’s spatial triad, recognising space as made up of three dimensions: perceived, lived and conceived.

The perceived space relates to the world that we experience through our senses, the things we touch, we smell, we flavour, we hear, or we see. The way we represent this perceived space is indeed the conceived space, and it can be distorted by other preconceptions or other interpretations of the space. Lastly, the lived space refers to the emotions and experiences attached to a place that grow while we spend time in it, and it can change between people (personally) or between different cultures.

From our analysis of the area, we concluded that all plans and strategies developed by the housing company and the municipality were only taking in consideration the perceived and conceived dimensions of Hjällbo, and communication regarding the lived space was missing between them and the inhabitants.

This broken connection between the different stakeholders in the area due to the lack of recognition of the memories, dreams and experiences of the inhabitants, as I now understand it, was breaking the link of the dwelling dimension, provoking a potential depopulation of the local inhabitants in the neighbourhood if the “Strategy for the development area: Hjällbo 2020-2030” was carried on, with the consequential increase of the renting prices, and the possibility for the neighbours to not be able to afford this rising.

As a first approximation to activate the iterative process to restore this dwelling link, our project focused on the engaging with the community and allowing a better communication between the different stakeholders. The aim was to recognize the value of the area from the inhabitant’s perspective, to connect the internal identity of the area with the external perceived image.

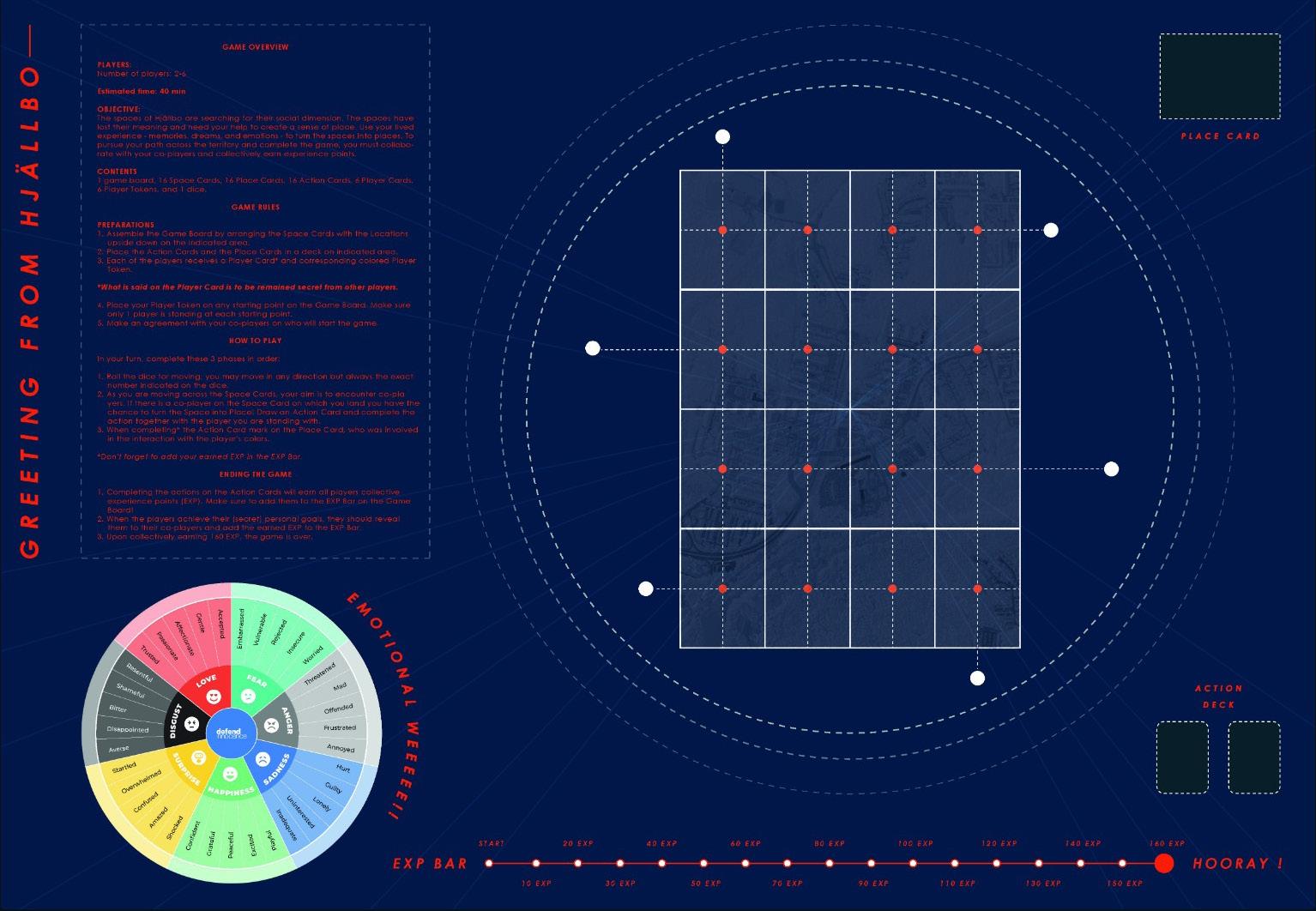

To do so, the devices developed during this project were a series of mock up board games, that lead to a final board game that was tested with the actual stakeholders. We found games as an approachable way to create participation and to exchange information, experiences, hopes, memories, dreams… creating a safe space and context to address certain issues in a more informal way.

The first mock-up game we developed was aiming to transform the “spaces” in Hjällbo into “places” by collectively creating experiences with the other players. To do so the different players would move around the board, made of “space cards” resembling real locations in the neighbourhood [Fig. 2], with the aim of unlocking these cards when two players encounter in one of them, and gaining “experience points” by completing together an action provided by an “action card” [Fig. 3].

This game was a first experiment for a device that could help to collect memories, dreams and emotions [Figs. 4]

Figure 5, Instructions to be followed in the second game elaborated.

Figure(s) 6, Testing for the first and second mock-up games developed.

In the second mock-up game, the experimentation was focused on achieving a tool that could help improve the communication between the stakeholders. The premise was that the points of view regarding the issues in the area between the three main stakeholders, the tenant’s association, the housing company and the inhabitants, were closer than they realized [Fig. 5]

To reveal this, the game was designed as a role play were each of the stakeholders had specific hopes, fears and perceptions of Hjällbo, defined after the several meetings we had with the different local agents. The aim of the game was to guess who out of the three stakeholders said different quotes that we extracted from the actual interviews we previously conducted. As the game goes, some preconceptions and prejudices are shown, and common knowledge is shared [Figs. 6]

Figure(s) 7,

Testing for the final board game with stakeholders.

The final game is the result of the combination between the first two, where communication between the stakeholders and the collection of the lived experiences are the main purposes for it. The intention is to visualize personal differences in the way people experience places and to invite a discussion about the emotional aspect of space. The first part of the game visualizes projections linked to mental images, or representations of space, which we believed influenced the processes that shape the physical urban landscape. In the second part of the game, these are confronted with actual lived experiences of the place in the form of memories and emotions. This last device was tested with some neighbours of Hjällbo and provided for them to keep it as an iterative tool to use in future participatory dynamics [Figs. 7].

This idea of the use of games to engage the community in the future design project is not new. In the discipline of urbanism, the revitalisation of Regents Park neighbourhood in Toronto would be a great example.

From the very beginning of the plan’s conception, a way was sought to involve the residents of the neighbourhood in the project. To do so, the Project for Public Spaces (PPS) organization designed “The Place game”, a game developed as a tool for evaluating any public space—a park, a square, a market, a street, even a street corner—and examining it through guided observation strategies (PPS, 2016) to make the community the expert (PPS, 2016).

To summarize, in this first selected project, the tool extracted would be the shearing of experiential knowledge from the different agents in the territory, and the device would be a board game as a community event useful to start a discussion and collecting in this way first impressions of the place as well as deeper values of the area related to the dwelling dimension and engaging with them.

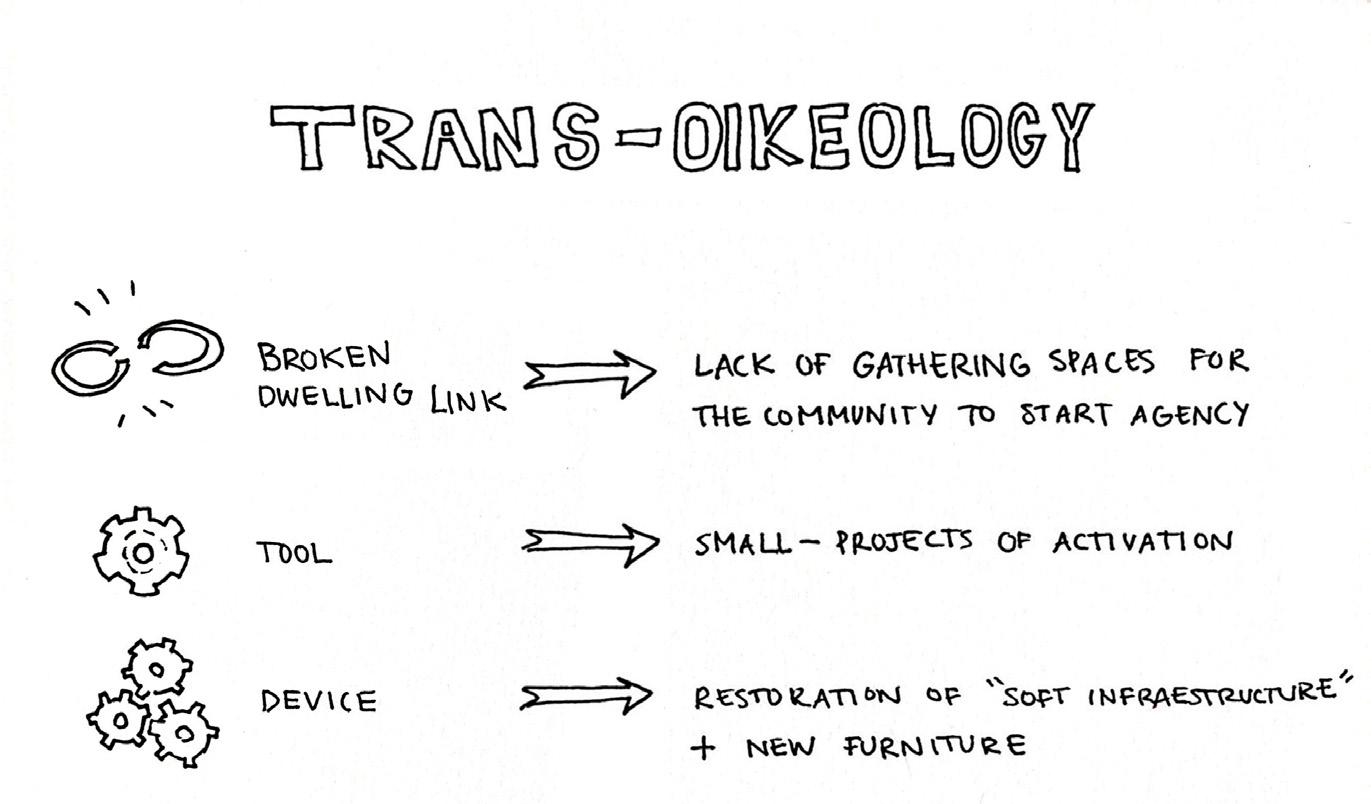

“... the dwelling link was broken due to a lack of spaces in which the existing associations and local initiatives could come together in other to begin the agency.”

Before my final semester of bachelor studies, I had the opportunity to participate in a summer workshop organized by the Observatory of Transdisciplinary Practices in Architecture (TRANS), an investigation group from my bachelor’s home university (UPM). This workshop took place in Morfi, a very small village in the increasingly depopulated region of Thesprotia, in the north-west cost of Greece, where agriculture and tourism are the main economic activities, due to the very important role of the landscape, that also relates to ancient mythology.

The project focused on the restoration of the local school of the village, which was an infrastructure abandoned for decades, to unlock a new gathering place for the local community, and in this way activate, through the people, the territory. In this case the dwelling link was broken due to a lack of spaces in which the existing associations and local initiatives could come together in other to begin the iterative actions that would lead to the recovery of the dwelling dimension.

In the beginning, the specifics of the final design of the restoration project were not clear, but the approach towards the way it was going to be thought were very carefully and intentionally planned.

To engage with the territory as external agents, we explored the physical dimension of its nature, at the same time as we approached other culture specifics such as gastronomy, discovering mythological routes and mapping places of biodiversity through local legends and myths.

The Acheron River, Morfea’s Cave or the stinx Black Lake were some of the places where to engage with Greek mythology, learning this way about the culture and heritage [Figs. 1].

During the workshop days, the focus was on keeping a transversal approach were drawing, writing, preparing a meal or building a table was valued of equal significance in the process of the developing of project itself. Acts of caring, creating community, taking cultural practices into the nature and creating experiences were some of the parallel “projects” carried on during the workshop.

The tool developed with the aim for the restoration of the dwelling link, was the “small projects of activation”. The re-activation of the school as a cultural and social hub was possible by the operation of small actions regarding the reformation of the “soft infrastructure” such as cleaning, fixing the wooden floor, painting the walls… and the development of devices which in this case constituted restored old furniture and new tables and benches build with new and recycled materials.

A crucial procedure for this tool to work in an iterative way was the last step carried on as part of the project; the “hosting the host”. When the restoration of the school was finished, the local community that welcomed us in their village during the workshop were invited to discover the new space that now was for them to take over [Figs. 2].

Another project where the use of this tool started a long-term agency is the case of the Ecobox by the “atelier d’architecture autogenérée”, in the La Chapelle area, in Paris.

In this project, a temporary garden was constructed using recycled materials in a leftover urban space, as well as some mobile furniture, in collaboration with students and designers. This small-scale project became over the years a cultural and social hub where the management of it has led to the creation of a strong thriving community.

Recapitulating, the tool obtained from this second project enables activation by the application of small-scale projects that can support local agents and their agency, aiming for engagement and new initiatives lead by them, shown in this project as devices in the form of “soft infrastructure” such as new furniture [Figs. 3]. This tool is to be used only after the one shared in the previous chapter, as it will require a knowledge of the needs of the agents.

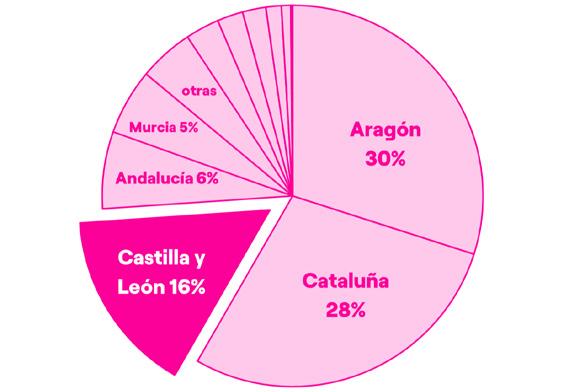

Percentage of pork production in the European Union

LPercentage of pork macrofarms in Spain

Percentage of pork macrofarms in Castilla y León

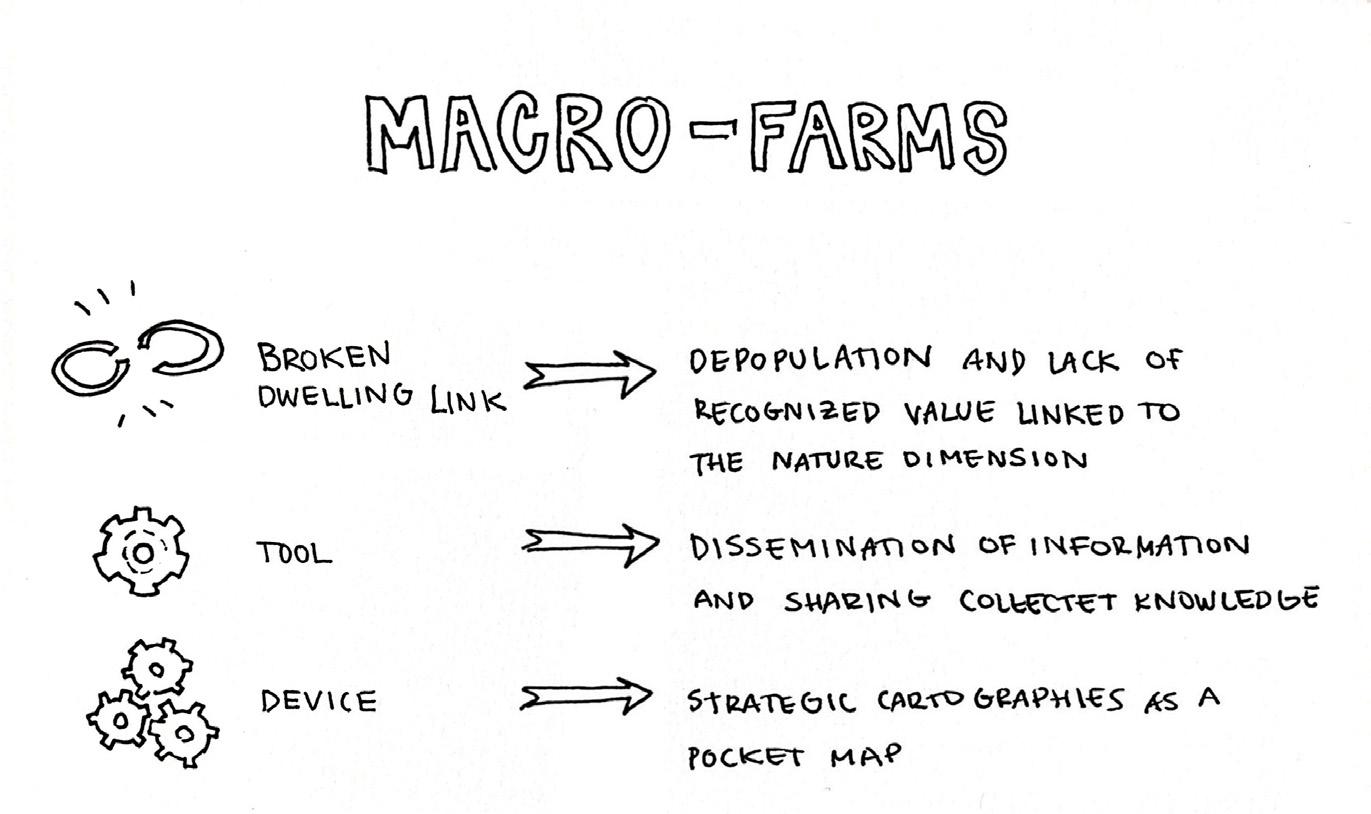

“... the lack of recognition of the value of the landscape relating to the dimension of nature, lead to the breaking of the dwelling link.”

astly before starting my landscape studies, during the development of my bachelor thesis I worked more deeplly with another case of a landscape where the dwelling link was broken.

In this ocasion, the landscape studied was a very familiar one. It was the landscape where I spent all my summer vacations, where I grew up, and where I always go back to. This is the province of Segovia, in Spain, the region where the most part of my family is from and where I feel more connected to a landscape, mainly because is the one where I lived some of my most valuable and cherished memories and I where I feel in touch with my heritage, my roots and, of course, with my identity.

This small region of Spain is part of a larger area known as “the emptied Spain” due to the increasing depopulation that is experiencing, along with an institutional abandonment, and overall ageing. All these reasons and the lack of recognition of the value of the landscape relating to the dimension of nature, lead to the breaking of the dwelling link.

The nature dimension of this landscape is mostly made up of fields, plains and moors, generally used for arable land and for agricultural and productive purposes. It is a land of contrast, where in summer temperatures can go as high as 30ºC,

and in winter as low as -10ºC. It is a “tough land to live and a tough land to love”, as my father will describe it, but for me is so easy to see the value in it. In my personal case, the lived memories play a crucial role, since anyone without the experiential emotions that I have towards this region will struggle to see it the way I do. The value I recognize in it relates to the identity that the landscape reflects on me.

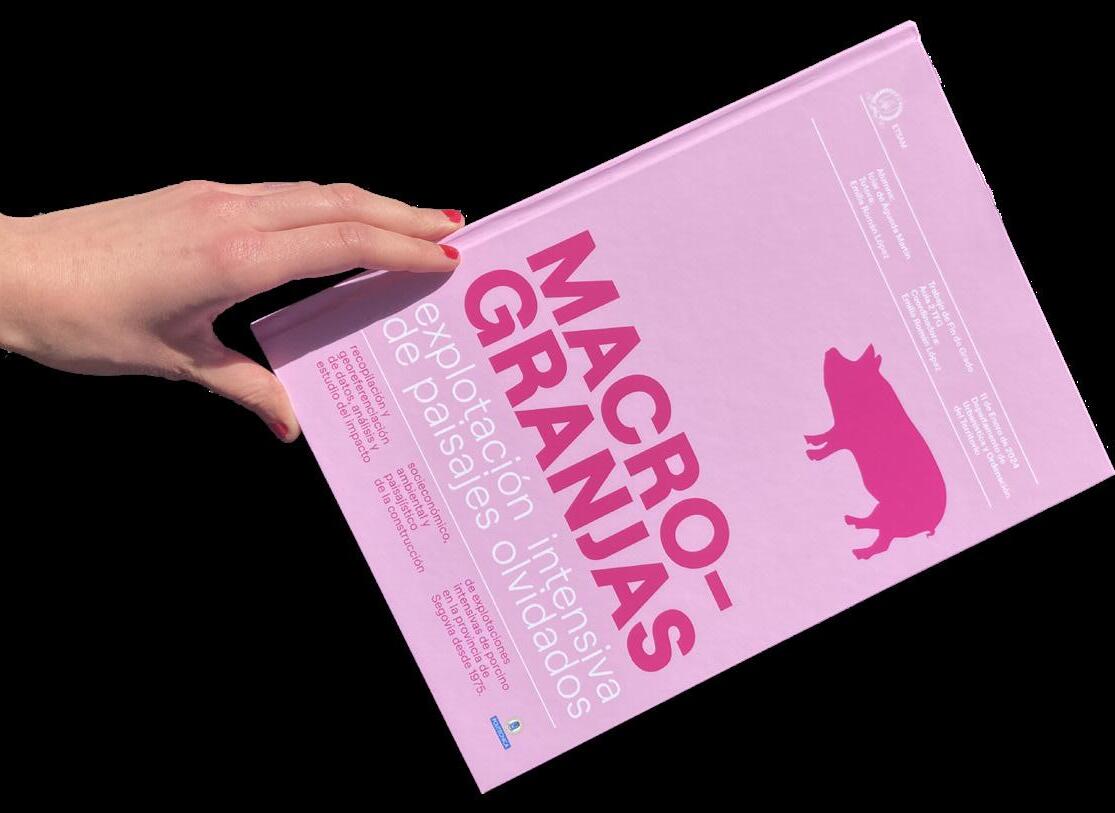

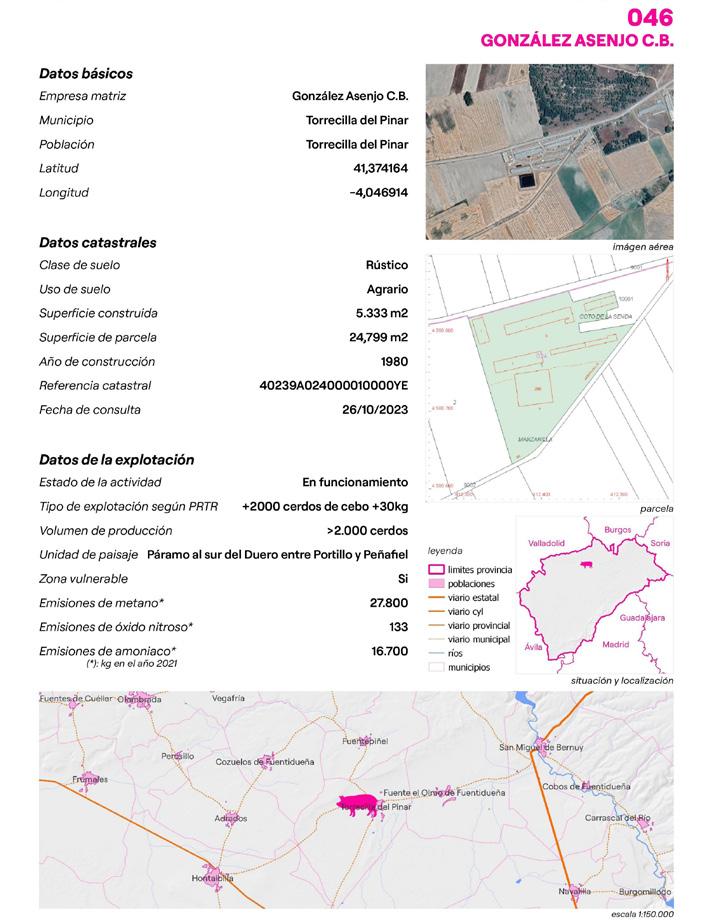

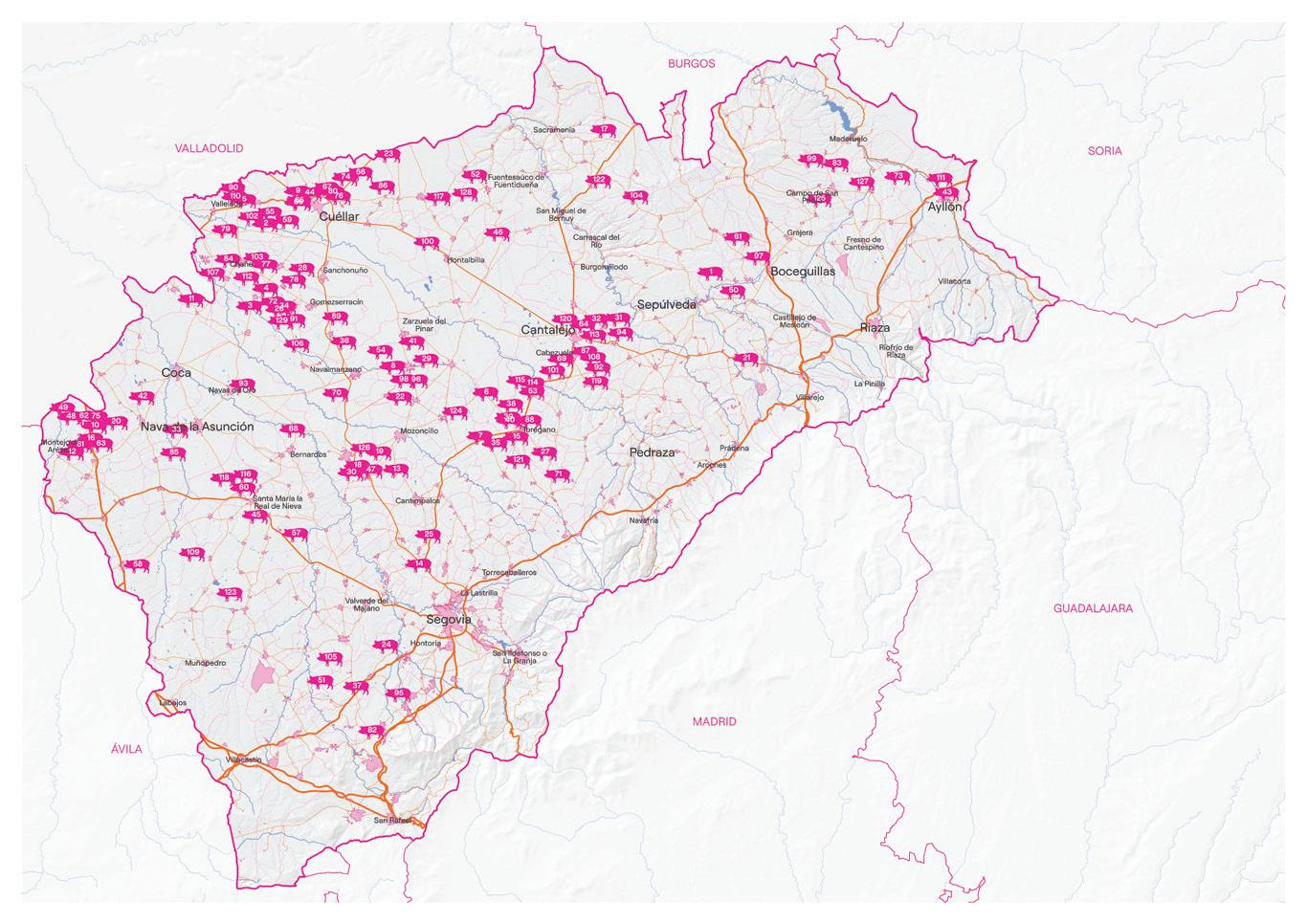

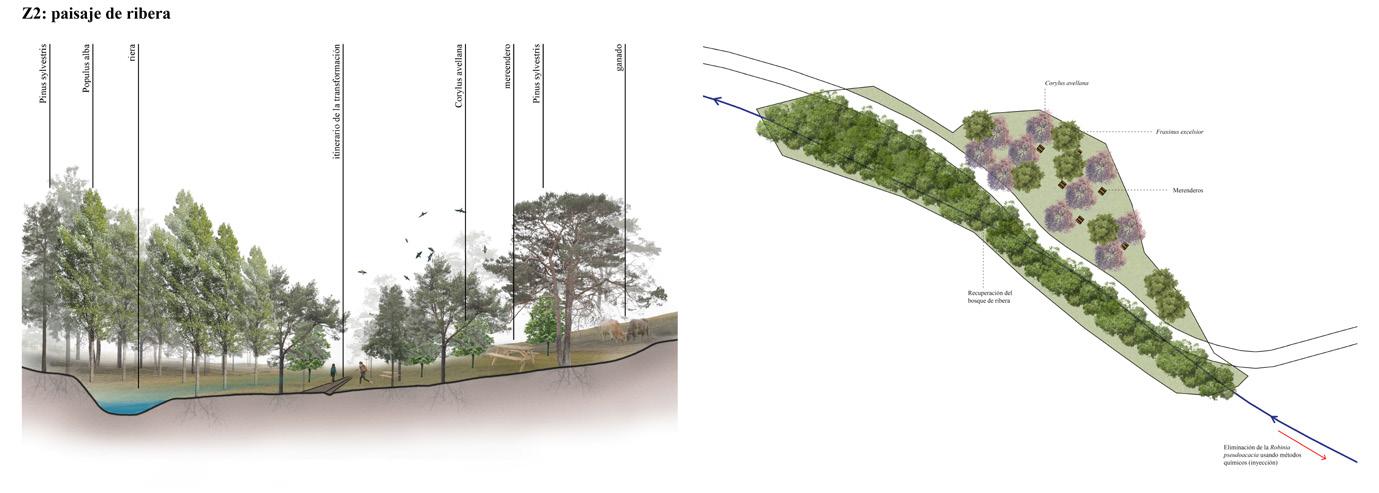

Since the last century, Segovia has experienced a change in its primary sector (as in many other parts of the world), which in the pork sector translates into a transition from extensive livestock farming (with a load of less than 15 pigs per hectare) to intensive livestock farming, which in turn has led to an increase in the number of facilities known as macro-farms, with a total of 129 large-capacity intensive pork farming facilities nowadays [Figs. 1]. These numbers, translated into heads of pigs, represent a total of 1,256,972 pigs. If this figure is compared with the number of inhabitants of the province the ratio obtained is 8 pigs for each inhabitant of Segovia [Fig. 2].

With the purpose to address the macrofarms situation in the region, the project focuses on the developing of a series of strategic cartographies that would help visualize the data collected in the actual context of Segovia.

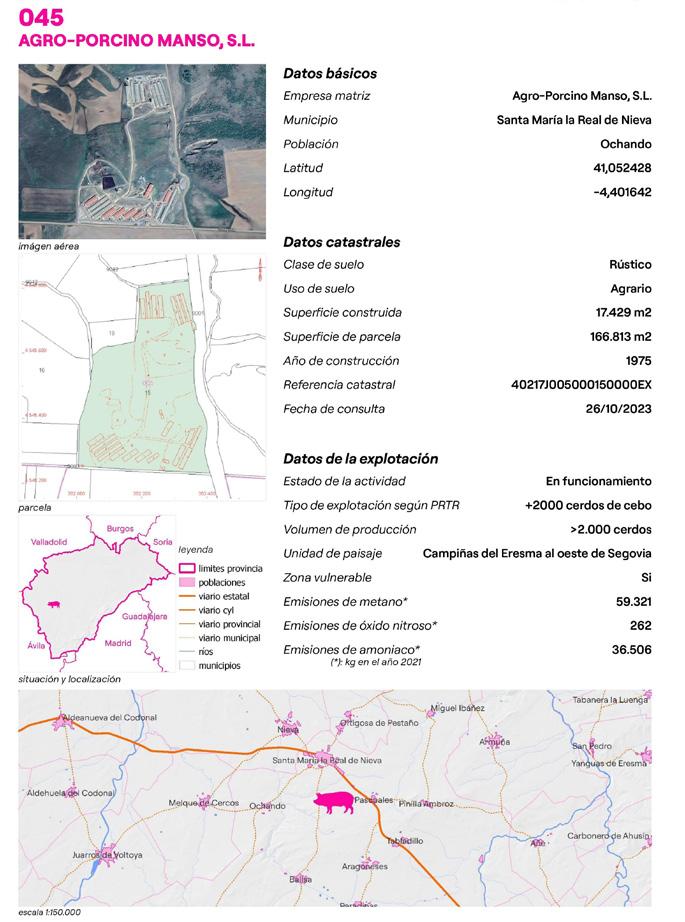

To do so, the socioeconomic, environmental and landscape impact was studied, field work was carried out to visit the farms and to interview those responsible for them. Finally, with all these information gathered, detailed characterization sheets of each of the 129 macro-farms in Segovia were developed to create an inventory capable of visually acknowledge the scale of the situation and make it easier to access the characteristics of each exploitation [Fig. 3].

All characterization sheets contain information collected throughout the development of the thesis, relevant to the understanding of the location and characteristics of each farm, and two of these characterization sheets were also expanded with a brief interview with employees of these facilities. To identify these exploitations, the name of the farm and the code with which it will be identified in the database developed later were indicated at the top of the sheet [Fig. 4]

As previously introduced, to geospatially analyse the situation, a georeferenced database of the macro-farms of Segovia was developed, including cadastral information, emissions, basic data of each farm...

In this way, the result obtained was georeferenced information, with a table of attributes that showed in detail the characteristics of each macro-farm.

Figure(s) 5, Front and back of the developed pocket map.

Figure(s) 5, Pocket map.

This information helped me finally develop the 12 strategic cartographies relevant to the investigation. To make it more accessible, the final form for this device was a pocket map, were all the macro-farms were located, numbered and named, and a brief contextualization of the general context was provided.

As an example of the elaboration of cartographies, the project “Los Madriles” developed by the studio Zuloark uses maps to make visible and to valorise local initiatives around the city of Madrid, giving the chance to the inhabitants to re-explore their city and their neighbourhoods.

The tool revealed in the elaboration of this project is the dissemination of information and pedagogy towards the local inhabitants of the territory in order to provide them with the knowledge collected, on this occasion in the form of a pocket map, as the resulting device developed

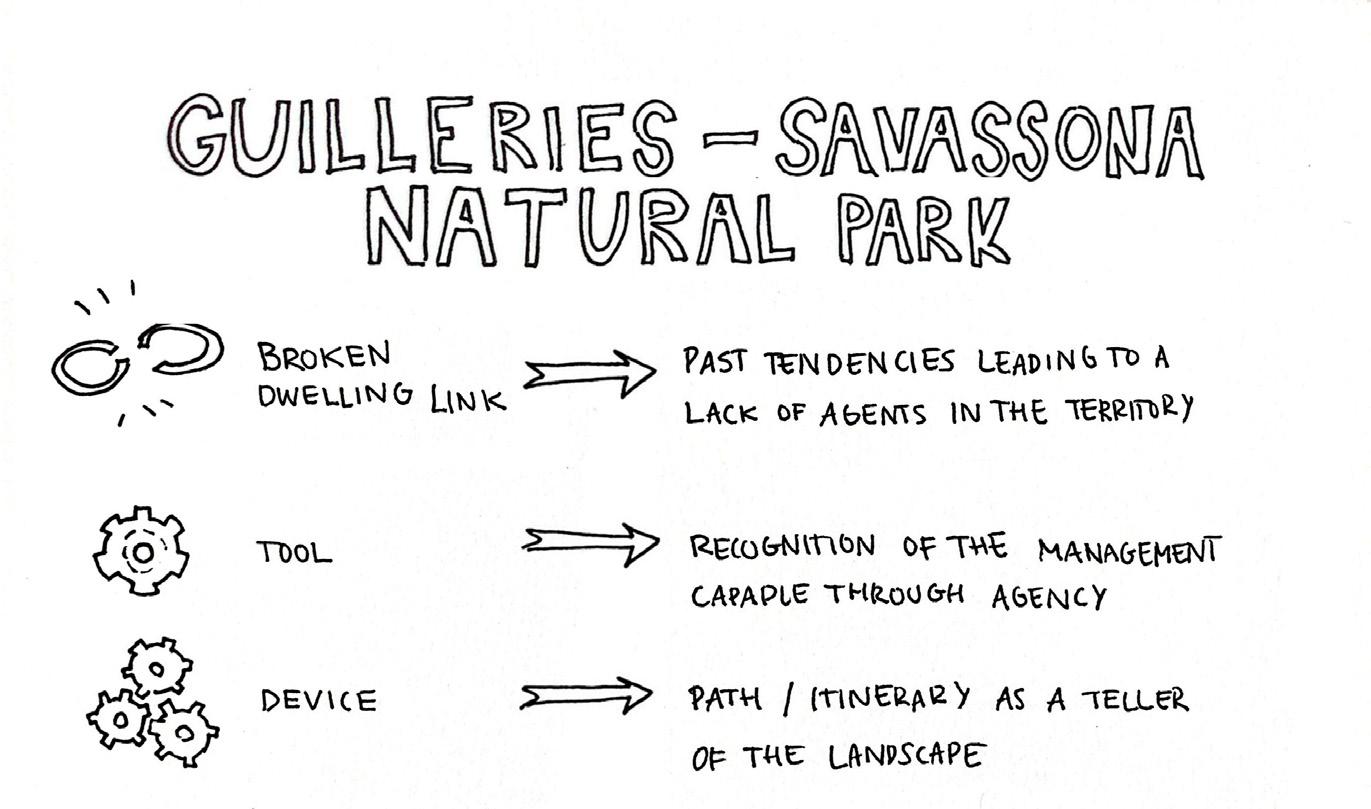

“... past tendencies heading to the growing lack of agents in the territory has translated into a broken dwelling link in the landscape of GuilleriesSavassona. ”

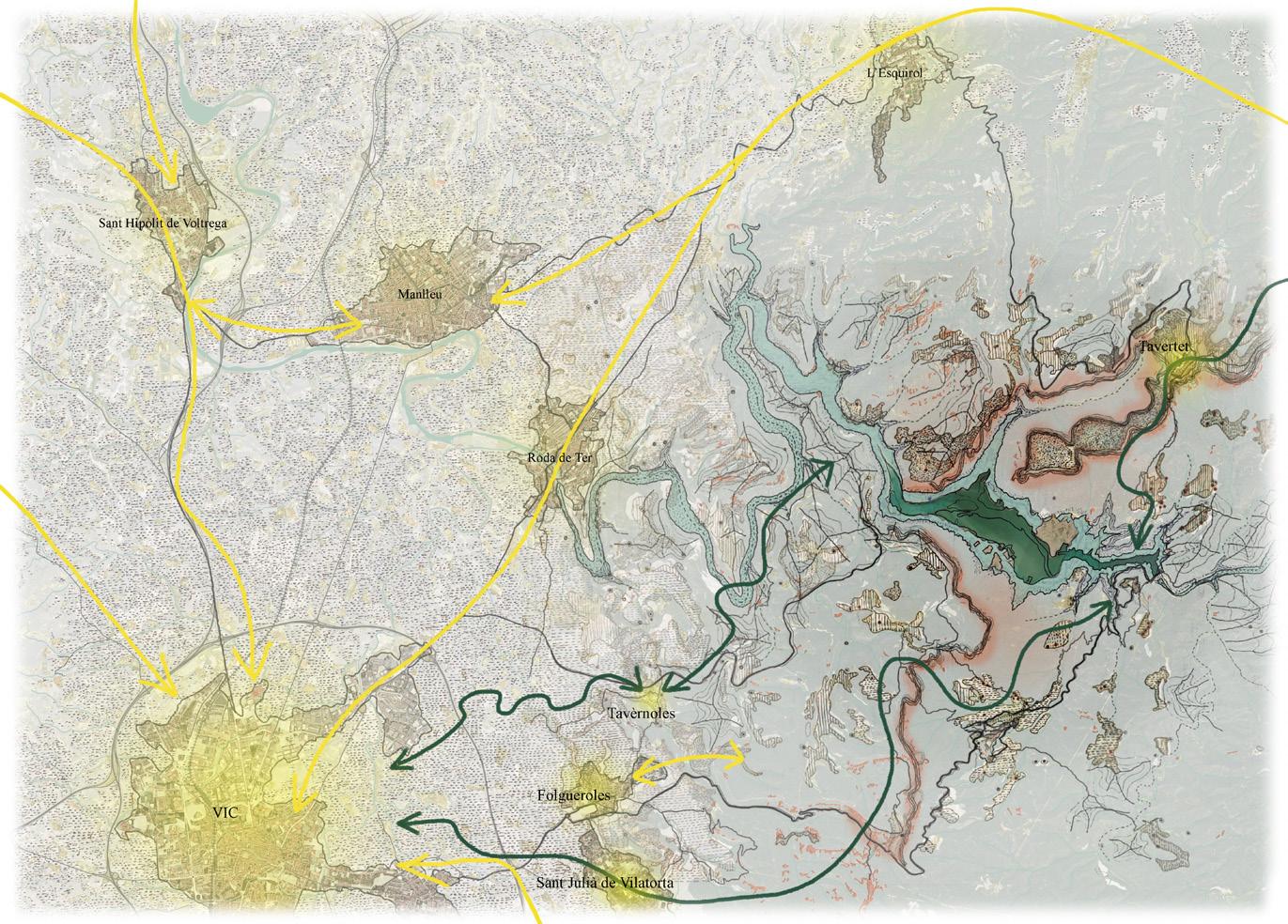

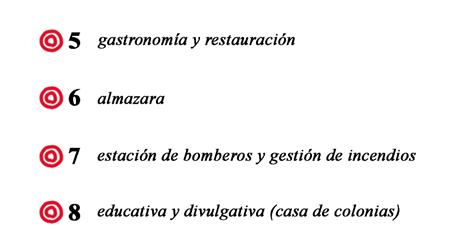

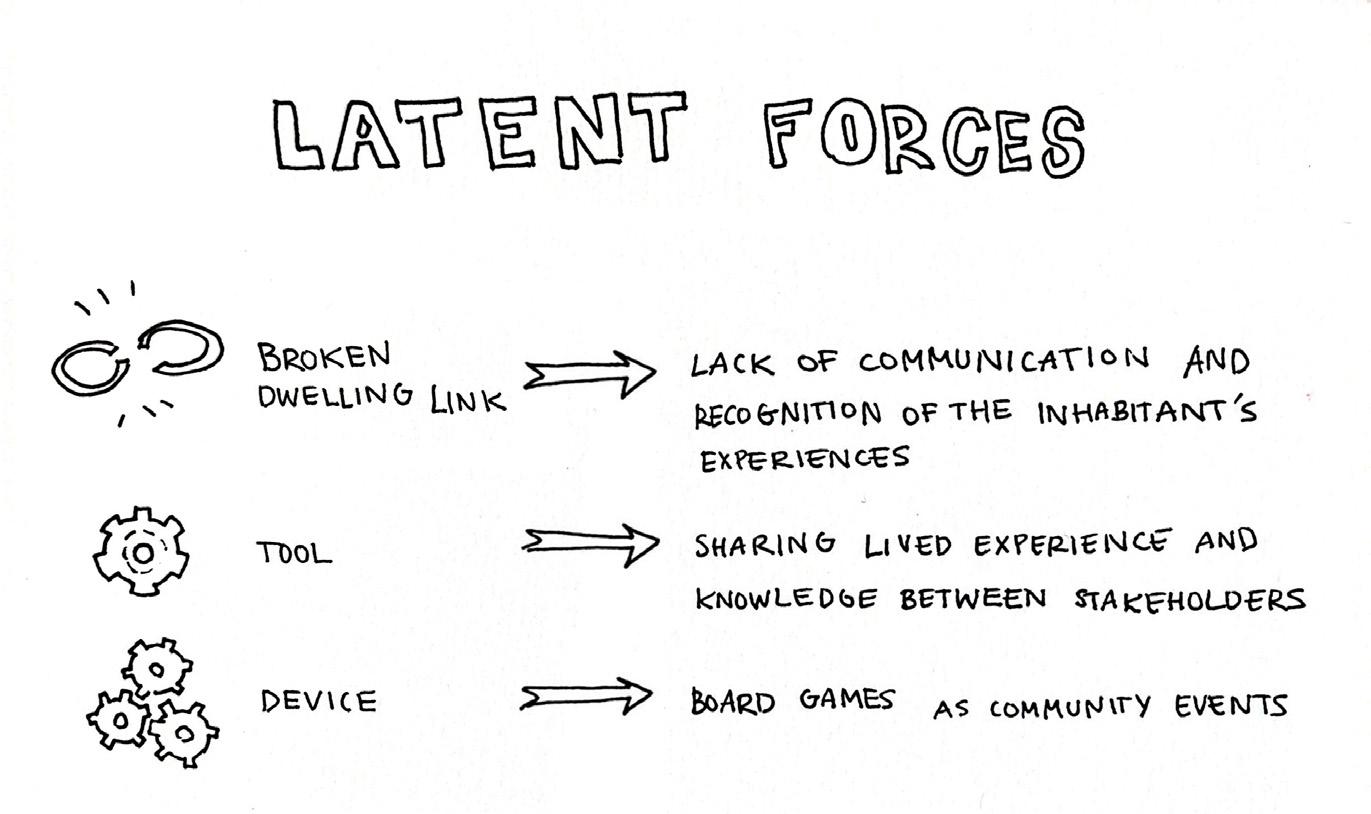

Lastly, we finally arrive to my very first landscape project, developed in group during my first semester of the master studies in Barcelona. The location of the project takes place in the Natural Reserve of Guilleries-Savassona, in the region of Barcelona and near the town of Vic.

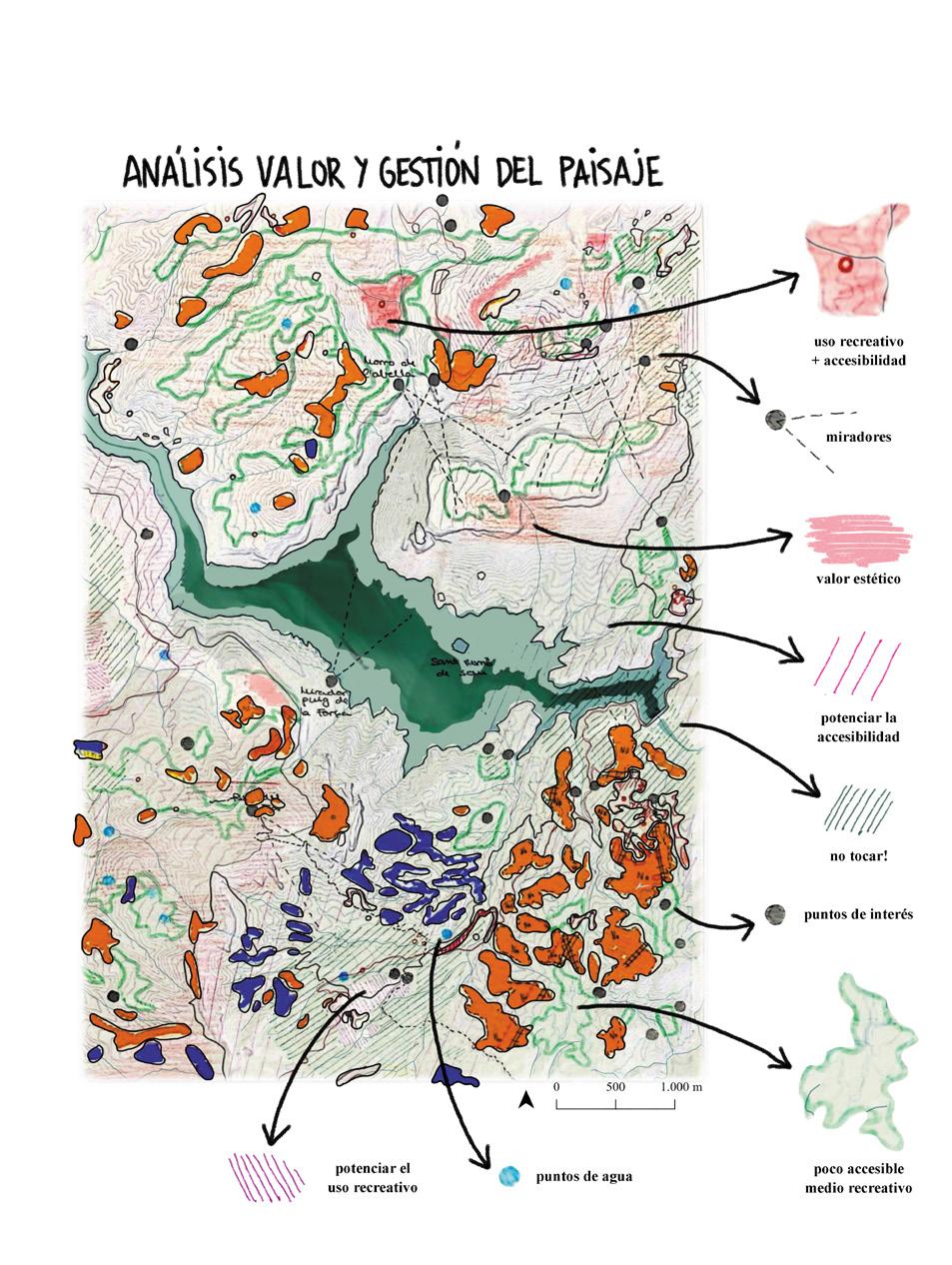

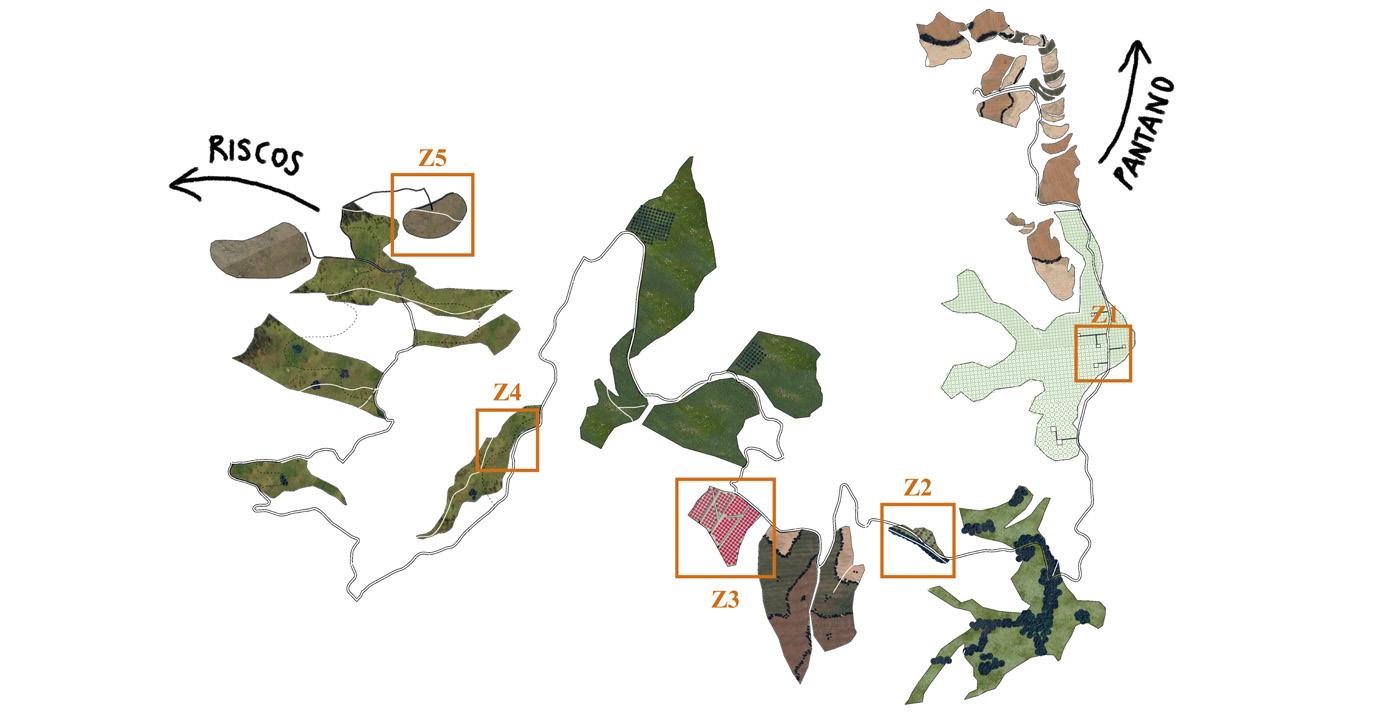

The natural dimension of the landscape reflects a central great reservoir of water (Pantà de Sau), that was reaching an extremely low percentage of its capacity due to the drought experienced in the last years in Catalonia, built by encapsuling with a dam the flow of the Ter River, framed and contoured by cliffs and mountains in reddish colours, all covered by a very dense vegetation, mainly consisting of pine trees and oaks in the most elevated areas and of false acacias and other riverside species along the streams [Figs. 1].

When focusing on the heritage or the symbolic dimension of this landscape, we reveal the history of the construction of the reservoir. The dam was built in the early sixties, causing the flooding of the valley and the creation of the reservoir in only two days, but at the same time, provoking the abandonment of the inundated old village of Sant Romá the Sau, and therefore the abandonment of the cultivations and the relocation of the community.

This was just the beginning of an extended tendency occurring in the decades to come, when more and more small settlements linked to the cultivation fields, agricultural and livestock production and the forest management, locally known as masías, were abandoned as a reflection of the rural exodus to the cities, leaving the land to develop on its own tendency towards the densification of the forest, leading (with the earlier mentioned added factor of drought) to an increasing risk of fires throughout the territory.

These past tendencies heading to the growing lack of agents in the territory has translated into a broken dwelling link in the landscape of Guilleries-Savassona. As we develop this project we identify new potential agents, currently only attracted to the territory for touristic reasons, mainly to visit the bell tower of the flooded village in the reservoir, which due to the lowering of the water level, becomes a symbolic place and a focus of attraction.

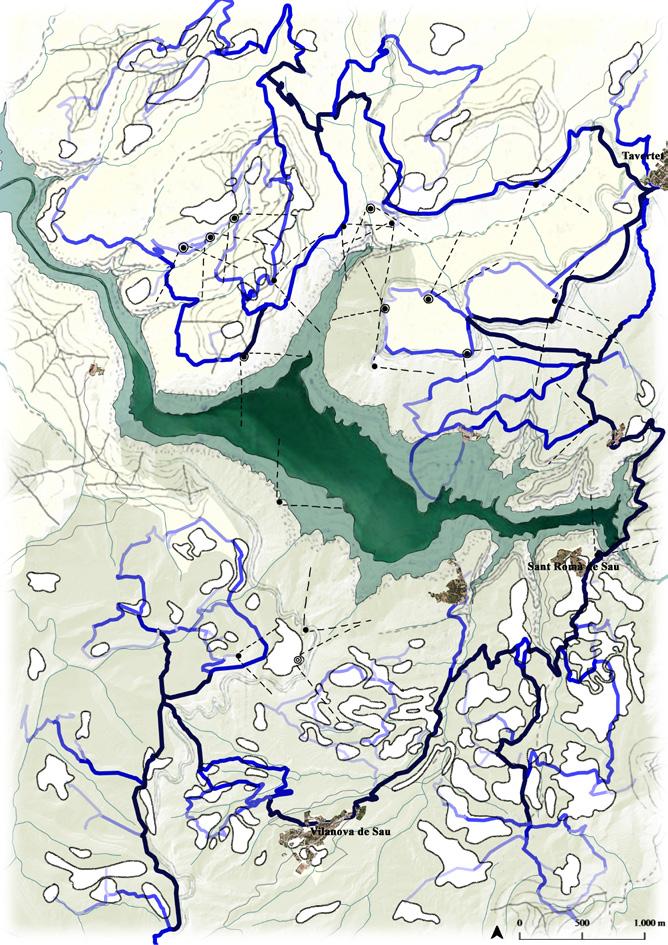

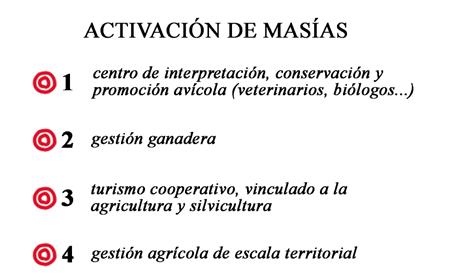

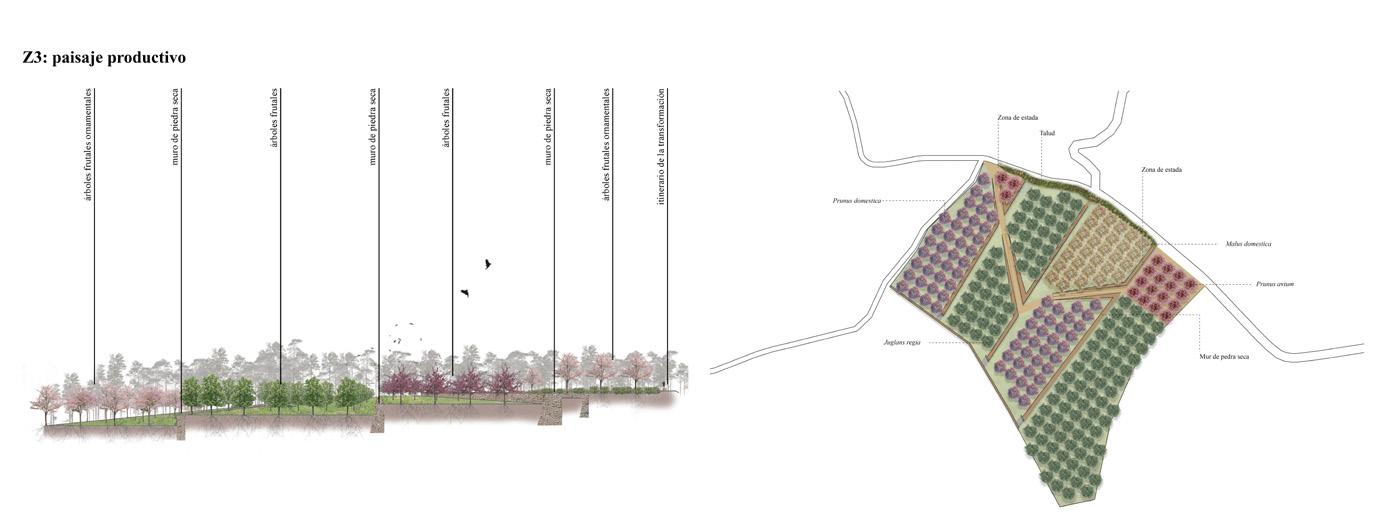

That’s why our project line focuses on diversifying and redistributing the activities and uses that this space can offer, while always being compatible with management, the most sensitive wildlife, and seasonality, with the transversal intention of reactivating the dwelling dimension [Figs. 2]

Figure(s) 2,

Collages reflecting the pervieved actual situation and the purposed situation.

In the process of the developing of the project, the first step consisted of carrying on a site visit to get to know the physical context, as well as to meet some of the remaining agents of the territory, such as local farmers, forest rangers, or even fire fighters working to manage the forests in the area. Is in this phase of the project, besides the meeting and interviewing of the agents, a tool as the one enabled by the game presented in the chapter, could have been useful to exchange impressions and preconceived ideas that we might have carried with us even after the field work. The use of this tool helps bringing the community together, as well as starting a discussion about topics that might not be talked about in other context, giving us much more information about the site, as well as starting a first iteration in which agents and designers come together and engage under a common aim.

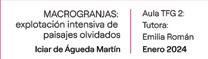

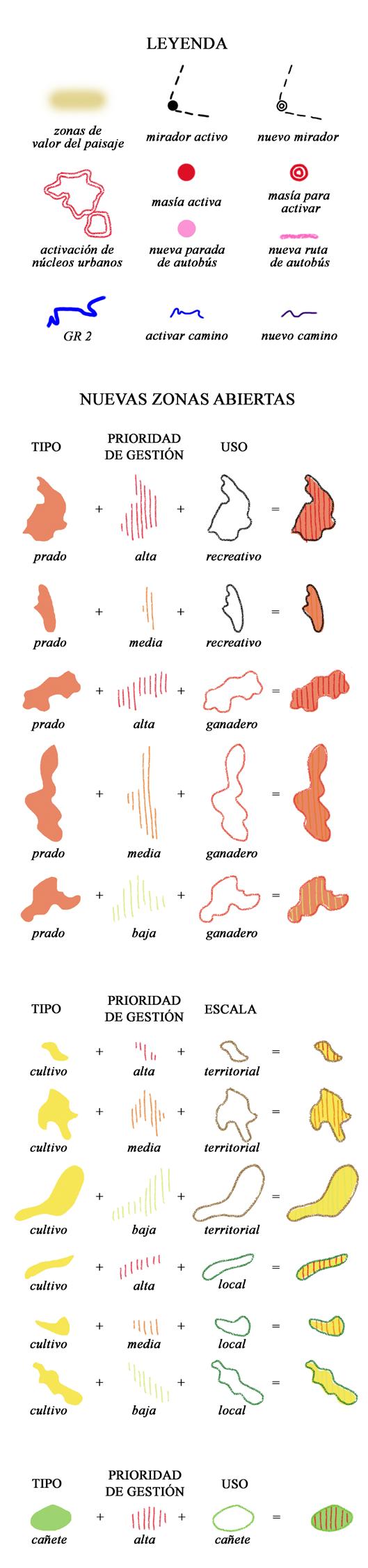

As this project is a student one, our capacity to take direct action on the site was very limited, and the proposal was design after several analysis where we contrasted and overlapped different information layers extracted from the different official geodata bases and some hand sketched drawings where we interpreted the aerial images in different periods of time [Figs. 3]

We thus identify forest areas with the potential to be converted to grassland or crops through management, forest areas with management priority due to fire danger, masías with high vulnerability to fire, recoverable crops in the event of increased drought, lost agricultural traces with favourable slope to be recovered, areas with potential for management by prescribed burning and masías isolated from the agricultural system.

In this way we further defined which areas were chosen to be opened, for what use (agricultural crops, meadows or pasture) and by what type of management (clearing, silviculture, prescribed burning and/ or livestock grazing). These management types were thought to be combined with the human intervention, as part of the reactivation of the territory and, consequently, of inhabiting it in a regulated and continued way.

Figure(s) 3,

Above: analysis for new open spaces. Below: analysis for the value and management of the landscape.

Figure(s) 5,

Actual use intensity of paths.

Right: Purposed use intensity of paths .

To attract these potential new human agents, and to make them stay and contribute to the territory, we analysed frequencies, intensity and main uses of the natural park [Fig. 4], and consequentially discovered potential new poles of attraction that were lacking of connectivity, a system of viewpoints associated with the cliffs, how anthropic flow was mainly concentrated on the roads that connected the urban centres with the reservoir, a main presence of the GR-2 route in the area characterised by points of interest with panoramic views, a network of paths linked to Catalan cultural heritage, how the poles of attraction were mainly concentrated in the area adjacent to the Sau reservoir… [Figs. 5]

In addition, and complementary to this analysis, we carried out a survey to define the possible target groups of the population from which this reactivation of the territory could be initiated.

This is how we came to define the proposal for the project, where three main strategies in the territory were followed.

The first one, as previously mentioned, consisted of the opening of forest areas. This strategy proposed the use, the maintenance plan and the socio-economic plan for these areas. The second proposed strategy was to reactivate abandoned masías, giving them a new purpose related to the use and management of the adjacent (existing or purposed) terrains related to the primary sector. The final strategy of the masterplan (the one with the aim for attraction) was to reactivate the mentioned GR-2 route to reconnect the territory [Fig. 5]

For these second and third phases of the development of the project, where the analysis was carried on and the masterplan design was conceived, the use of the second tool, about the small-scale projects, explained in chapter could have supported the decision-making for the proposal while begging the engagement of the community. The use of this tool in the context of this project would have been very helpful in the testing of the diverse uses and types of management for the expected new open areas.

An example where the use of this tool, and the idea of reversing the traditionally established process of design in landscape architecture, can be seen is in the Martí Franch project for the Girona’s Shore. In this project the process is inverted, as the design ideas are being tested on site while developing the knowledge to further elaborate the “final plan”. This inversion of the process also allows the designer to use the site as a laboratory to develop better adapted protocols, defining a strategic methodology system on how to design depending on the specific characteristics of each area (the Differentiated Management Design).

As an added layer for the final project, the use of the third tool, detailed in the chapter can be significant. The use of the strategic cartographies to share with the community the proposed new open areas, as well as the new connecting paths between them and the masías associated alongside the use and type of management planned for them, would be a valorisation method to recognize the new auto-sufficient networks created and to visualize the links between agents.

Figure(s) 8, Detailes plan and section of the secquence of new open areas. In order: silviculture, recreational, productive, livestock and birdwatch.

Finally, as in the previously presented projects, a tool and a device were extracted from this last one. In this case, the tool became the actual recognition of the agency achieved for the management of the territory, with the purpose to reinforce the fulfilled restoration of the dwelling link, only possible with the effort and engagement of the inhabitants.

To do so, the device designed for the last phase of this project is the “transformation itinerary“ [Fig. 7] a route that allows the user to walk through and get to know both the land and its management, following a sequence of new proposed open areas with different uses; recreational areas, terraced areas with vines and fruit trees, meadows for resting next to livestock and bird observatories [Figs. 8]

As in the Girona’s Shore project, a new beauty is pursued, one that allows its worth to be renewed in the eyes of the public (Martí Franch, 2020), and in the same way, to do so, the path is used as a teller revealing trough time the qualities of the presented landscape, using the sequences of the new opened areas and their specific management as Martí Franch uses the “confetti” to identify, value and celebrate the peculiarity of a place and the radiance of its surroundings (Martí Franch, 2020). The aim of this itinerary is to offer an experience of awareness and knowledge of the landscape and its management through perception and the senses, and thus enhance the valorisation of the activities and tasks carried on by the agents that make the landscape.

Bibliograp

As a result of this portfolio, I have been able to understand a common link in between the main projects that have led me into the landscape discipline, as well as recognize in them useful tools to carry with me for my future practice, always involving the community and with the agency and the dwelling dimension in the centre.

For each of the projects, a device was elaborated following the tool used in consequence of the main reason why the dwelling link was broken in each case. All these devices were capable of starting a new iteration that could eventually lead to a potentially successful landscape project focused on the management of the landscape itself [Fig. 1] .

Books & articles:

• Franch, M. (2018). Drawing on site: Girona’s shores. Journal Of Landscape Architecture, 13(2), 56-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2 018.1553396

• Ingold, T. (1993). The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25(2), 152-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1 993.9980235

• Ingold, T. (2017). Taking taskscape to task. In U. Rajala & P. Mills (Eds.), Forms of Dwelling (pp. 16–27). OXBOW BOOKS.

• Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space.

• Perrault, E., Lebisch, A., Uittenbogaard, C., Andersson, M., Skuncke, M. L., Segerström, M., Svensson Gleisner, P., & Pere, P.-P. (2020). Placemaking in the Nordics. Handbook: Placemaking in the Nordics | Future Place Leadership

• Ps paisea (2020). Ps paisea #6. Girona’s shores. https://www.dropbox.com/s/1oiabqp06rr95mu/PS%236%20INGLES. pdf?dl=1

Websites:

• Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée. (n.d.). ECObox. Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from: https://www.urbantactics.org/ projets/ecobox/

• Spatial Agency. (n.d.). Atelier d’architecture autogérée (AAA). Spatial Agency. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from: https://spatialagency.net/ database/aaa

• Project for Public Spaces. (n.d.). The Place Game: How We Make the Community the Expert. Project for Public Spaces. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from: https://www.pps.org/article/ place-game-community

• Zuloark. (2024, November 22). Los Madriles. Zuloark. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from: https://zuloark.com/es/projects/ los-madriles/