International

Research Journal of Engineering and Technology

(IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

X-RAY FLUORESCENCE BASED CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF LADLE REFINERY FURNACE SLAG: A REVEIW

Muhammad Romeo N. KhanMilitary Institute of Science and Technology (MIST), Dhaka, Bangladesh, Email: mrnkhan1975@yahoo.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4806-2035.***

Abstract: This study explores different studies to find out the chemical composition of steelmaking slag generated in ladle refinery furnace. The data in this study is collected from a thorough review of the several papers in the literatures related to chemical composition of ladle refinery furnace slag. For this purpose, the paper represents data found from different study and includes data from a steelmaking plant in Bangladesh. Then an examination is carried out focusing on the chemical compositions of different slags from different corners of the world. The paper discovers the huge variation in chemical compositions of different ladle refinery furnace slags under study and the same found from different studies. It is very well clear that chemical composition greatly influences the properties of slag and the properties dictate the applications of the slag. This study has revealed the distinctive characteristic of ladle refinery furnace slag that the chemical compositions of these types of slags have lots of variations even between the batches of production in the same plant. It can also be concluded that all ladle refinery furnace slag behave very differently, depending on their chemical composition, and must be treated and studied individually. This inherent variability of ladle refinery furnace slag offers a vast area for researcherstostudy.

1953.304milliontonnesofcrudesteelwasproducedin 2021 only [1]. Steel use per capita in 2021 globally stands at 232.2 Per capita consumption compared to global standard indicates huge industry prospect.In 2021, 70.8% ofsteelwereproducedinBOFand28.90% inEAFandrest 0.30%inOHprocess[2].1878milliontonnesofcrudesteel wasproducedin2020.In2020,itwas73.2%ofsteelwere produced in BOF and 26.3% in EAF and rest 0.50% in OH process [3]. The statistics of 2020 and 2021 when compared show that the world steel market is growing bigger. Again the world steel industry is shifting towards EAF gradually. LRF refines the basic SS further. It is assumedthatsteelindustryisincliningtowardsLRF.

Approximately150-200kgofSSisproducedpertonsof steel.ItisverylikelythattheproductionamountofSSwill rise in the coming years with the growth of steel production. Steel industry is unambiguously concerned aboutthegenerationofa hugequantityofthisby-product, i.e.SS.

The buildup of an enormous amount of SS has caused difficulties to the steel industry due to occupation of land and harming the environment, beside the waste of resources. Moreover, factories pay so much cost for the disposalofthesematerials[4].

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally various types of steels are produced through several steelmaking processes. Steelmaking processes are named according to the furnaces used in the production process. Namely open hearth (OH), basic oxygen furnace (BOF), induction arc furnace (IAF) and electric arc furnace (EAF).Steelmakingslag(SS)isabyproductofsteelmaking andalsorefiningprocesses.Toextractmoreoftheintended material, the secondary refining of SS is done in many occasionsnow-a-daysthroughladlerefineryfurnaces(LRF) orladlefurnace(LF).Slagproducedthroughthisprocessis called secondary slag or LRF slag (LRFS) or simply LF slag (LFS)orLadlefurnacereducingslag(LFRS).

Over the last few decades, the European steel industry has focused its efforts on the improvement of by-product recovery and quality, based not only on existing technologies, but also on the development of innovative sustainable solutions. These activities have led the steel industry to save natural resources and to reduce its environmentalimpact,resultinginbeingclosertoits“zerowaste” goal. In addition, the concept of Circular Economy hasbeenrecentlystronglyemphasizedataEuropeanlevel. The opportunity is perceived of improving the environmental sustainability of the steel production by saving primary raw materials and costs related to byproductsandwastelandfilling.[5]

Natural resourcesoftheplanetcalledeartharelimited. Construction industry and conservation of natural resources need use of different recycled and industrial byproducts in construction sector for a sustainable

© 2022, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 7.529 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page1426

Keywords - Steelmaking Slag (SS), Ladle Refinery Furnace Slag (EAFS), chemical composition, X-Ray Fluorescence(XRF)International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

development of this planet. Naturally found stone is generally crushed and used as the coarse aggregate of the concrete. The objective of using SS is to replace natural aggregate in concrete as much as possible. It is initially based on its obtainability and superb physical and mechanicalcharacteristics.SSmaybeutilizedconsiderably inthreemainways.Thetraditionalpracticeistodisposeoff SSbydumpingorstockpilingonsomeland.Predominantly, there may be a substantial reduction in environmental pollution if SS are used up in concrete. Next, the use of SS will increase the reduction of using natural resources. Furthermoreitmayalsocontributeinguardingtheenergy requirements related with the natural stone processing industry.Lastly,thepriceofproducingtheconcretemaybe reduced.

2. PRODUCTION PROCESS OF LRFS

SS is defined as the solid material resulting from the interaction of flux and impurities during the smelting and refining of steels. The American Society for Testing Materials (ASTM) defines SS as ‘a non-metallic product, consisting essentially of calcium silicates and ferrites combinedwithfusedoxidesofiron,aluminum,manganese, calcium and magnesium, that is developed simultaneously with steel in basic oxygen, electric arc, or open hearth furnaces’.[6]

AnytypeofSSisamoltenby-productgeneratedduring theproductionofanytypeofsteel.Duringtheseparationof the molten steel from impurities in steelmaking furnaces, SS is acquired. SS can be categorized according to the furnaces used for its production. LFRS is a byproduct of steelmaking industries obtained from the LF refining of carbon and low alloy steels. The ladle furnaces (LF) have only been constructed in significant numbers since the 1980's[7].Ladleslaggenerationisapproximatelyonethird ofthetotalamountofslagusuallyproducedinanEAF[8].

The ladle furnace basic slag is produced in the final stagesofsteelmaking,whenthesteelisdesulfurizedinthe transport ladle, during what is generally known as the secondary metallurgy process [9]. The most important functions of the secondary refining processes are the final desulfurization, the degassing of oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen, the removal of impurities, and the final decarburization (done for ultralow carbon steels) [10]. In the process, an average of 30 kg LFS slag per ton of steel produced[11].

LF slag is produced in the secondary metallurgy or refining process, which generateshigh-gradesteels. In this process, liquid steel first undergoes an acid dephosphorylation process in the EAF (oxygen blowing). Then,thesteelisdischargedintoaladlefurnace;whereitis deoxidized, desulfuredandalloyed underthe protection of abasicslagi.e.LFSlag.[12]

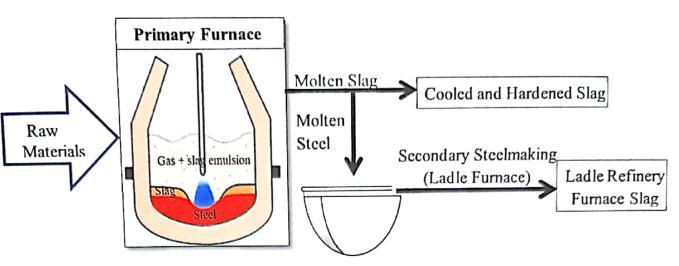

The flow chart of production of LRFS is shown in the followingFig.1.

Fig-1: FlowChartofProductionofLRFS

3. PROPERTIES OF LRFS

The properties of any type of SS define the application. So knowledge of the physical, chemical, mineralogical, and morphological properties of SS is vital. Cementitious and mechanical properties are also significant to know. Beside the mineralogical composition of SS, chemical composition hasagreatinfluenceonitsuseforvariouspurposes.Again, SS is a byproduct of the steelmaking process in which its quality depends on its origin [13]. The chemical, mineralogical, and morphological characteristics of SS are determined by the processes that generate this material. Therefore, knowledge ofthedifferent types ofsteelmaking and refining operations that produce SS as a byproduct is alsorequired.[10]

Based on mainly, the manufacturer, types of steel generated and cooling conditions of the slag the characteristics of the SS produced differ. Furthermore, when SS are refined in ladle furnace, the properties of SS goes through another step of transformation. Thus LRFS aregenerated.Therefore,beforeanySScanberecycledinto greenerproductsorutilizedorreusedindifferentproducts, the study is essential to understand the slag properties. This includes how formation process of SS, its chemical compositions, mineralogical behavior, and harmful contents. The impact, abrasion and frictional properties of SS are influenced by its physical features, morphology and mineralogy.Chemistrybasedonchemical compositionand mineralogyinfluencesthevolumetricstabilityofSS.

ThechemicalcompositionandcoolingofmoltenSShave a great effect on the physical and chemical properties of solidified SS [14]. Also the rate of cooling from a molten liquidtoasolidmainlyaffectsthephysicalpropertiesofSS aggregate and as such, its chemical reactivity [15]. In general,several factors areaffecting physical and chemical properties of SS. These factors include: Type of steel furnace,steelmakingplantandSSprocessing[16].

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

4. PHYSICAL, MECHANICAL, MINERALOGICAL AND CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF LRFS

4.1 Physical and Mechanical Properties

It was found that steel slag aggregate (SSA) has superior physical and mechanical properties as well as lower carbon footprint and reduced negative environmental effects [17, 18]. Steel slag aggregates are fairly angular, roughly cubical pieces having flat or elongated shapes. They have rough vesicular nature with many non-interconnected cells which gives a greater surface area than smoother aggregates of equal volume; this feature provides an excellent bond with Portland cement.Steelslaghasahighdegreeofinternalfrictionand high shear strength. The rough texture and shape ensure littlebreakdowninhandlingandconstruction[19].

Steelslaghashighbulkspecificgravityandlessthan3% water absorption. Steel slag aggregates have high density, but apart from this featuremost ofthe physical properties of steel slag are better than hard traditional rock aggregates.Belowarelistedsomeofthepositivefeaturesof steelslag.[20]

LFSisobtainedinaslowcoolingprocessandpresentsa large content of fine particles, with 20–35% below 75 μm [21, 22]. According to its surface properties, the LFS is considereda mesoporousmaterialwithgreatsurfacearea; ecotoxicity evaluations pointed out that it is a nonhazardous industrial waste [23]. LRFS has good mechanicalproperties:itisacrushedproductwithgreyish orsometimesblackcolourstoneappearanceandhasavery roughsurfacetexture.

Steel slag is a dense rock having a raw density > 3.2 g/cm3 [24]. It has high abrasion resistance, low aggregate crushing value (ACV) and good resistance to fragmentation. The density of LRFS lies between 3.4-3.6 g/cm3. It is observed that after a crushing process, the coarse aggregate can be easily adjusted to meet the grading requirements of the ASTM C33 standard (maximumsize1in.,25mm)[25].LRFSfoundfromasteel plantofBangladeshisshowninFig 2.

Fig – 2: LRFSlag(LRFS)

Thesehaveaveryroughsurfacehavingroughlycubical pieces with flat or elongated shapes and modestly sharp edgeswith numerousofpores.Theangularshapehelpsto develop strong interlocking properties and together with the increased surface area due to cell like pores provides goodbondingwithcementsandotheraggregates.Theyare moderatelystronganddurable.Itisalsoobservedthatthe flakiness index value for slag was generally low which attributes to the rounded shape of SS. SS aggregate (SSA) arehardanddurableandhavehighresistancetoabrasion andimpact.

4.2 Mineralogical Properties

The main mineral phases contained in SSare dicalcium silicate(C2S),tricalciumsilicate(C3S),ROphase(CaO-FeOMnOMgO solid solution), tetra-calcium aluminoferrite (C4AF),olivine,merwiniteandfree-CaO[26].

On the same note, the mineralogical compounds detected in the LF slag could be attributed to mayenite (12CaO⋅7Al2O3, Ca12Al14O33, and C12A7), periclase (MgO), gehlenite (2CaO⋅Al2O3⋅SiO2, Ca2Al2SiO7), larnite (��2CaO⋅SiO2,��-Ca2SiO4),shannonite(��-2CaO⋅SiO2,��-Ca2SiO4), and tricalcium aluminate (3CaO⋅Al2O3, Ca3Al2O6, and C3A) [23,27].

Cooling rate and chemical composition determine slag crystallisation [28]. The temperature at which the cooling occurshasagreatinfluenceonthefinalphasecomposition of the SS. Very rapidly cooling of the liquid slag, does not allowsufficienttimeforthecrystalstogrow.Hencecrystals of the SS will be much smaller, resulting in a more homogeneous overall composition. However the rapid coolingenablesthepossibilityofhavingmetastablephases at low temperatures. Considering all these, LRFS are generatedthroughslowcooling.

During the rapid cooling with water, oxidation on the surfaces may occur, and thereby the formation of soluble phases. Side by side, fast cooling will result in an abrasive surface, due to the presence of smaller grains at the

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

surface.Anabrasivesurfacetendstobemorereactivethan aplanesurface,duetotheincreaseinvapourpressurethat occurs over a convex surface. Thus it will result in more grain boundaries due to the increase of small crystals in thematerial.Diffusionreactionsareknowntooccureasier andfasteralongtheseboundaries[29].

4.3 Chemical Properties

The chemical behavior of SS depends on the chemical propertiesofSS.SimilarlychemicalpropertiesofSSdepend on the chemical composition which vary depending on the end materials to be produced i.e. type of steel, production process,typeoffurnace,feedstocki.e.rawmaterial,cooling speed and temperature and then slag formers used to produce the steel. Besides, element of environment of the dumping place in the factory yards or any place, changes thechemicalcompositionoftheSS.Thustherawmaterials usedforgeneratingsteelinthatlocalityandexposureofSS to ambience of the specific locality greatly contribute in changing the chemical composition leading to its chemical properties.

The main components of the LFS are calcium, silicon, magnesium, aluminum oxides, and calcium silicates under various allotropic forms [30]. The main compounds are calcium, silicon, magnesium, and aluminum oxides representing more than 92% of the total mass [23]. Other minor components include other oxidized impurities, such asMnOandSO3

ThechemicalcompositionandmineralphasetypesofSS from diverse generating areas and plants may be different dependingonthedifferencesinsteelmakingrawmaterials and smelting processes. The LRF steelmaking process is fundamentally an additional step to basic steelmaking process. Again the chemical composition of SS depends on the steelmaking process which is also an important factor for its CO2 reactivity [21]. The composition of the Ironbearing feed i.e. the raw materials and the batch natureof the steelmaking practices can introduce even larger variation. It is significant that LRFS composition is dependentontherawmaterialsourceforthebasicfurnace anditschemistrymaydifferfromonebatchtoanother.For LRFS cooling temperature and rate play a vital role. It is worth mentionable that cooling rate and chemical compositionregulateslagcrystallization.

5. CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF DIFFERENT LRFS

It is predicted that LRFS from different parts of the world and different producers of steel may exhibit a different appearance, physical and chemical properties, dependingonthecompositionofsteelscrapthatisusedas feed materials, the type of furnace, steel grades, refining and cooling processes. The characteristics of the slag produced at each steel manufacturing plant may vary

because it depends on the entire production process of steelusedfromfeedingrawmaterialsuptotheSSdumped. Thefeature,qualityandcompositionofLRFSdependonthe steelscrapusedasrawmaterial,typeandshareintheheat ofspecificnonmetallicsupplements,typeofsteelproduced, type of furnace used and other technological parameters includingrateandtemperatureofcooling.

Review of several studies found out some factors on which the properties of the SS depend. These are namely the furnace type and condition, source, type and chemical compositionofsteelscrapandotherrawmaterials,typeof process (batch process in which reactions are not always completed, thus resulting in a non-uniform slag), use of Dolomite,typesofsteelproduced,typeandrateofcooling, temperature at which cooled, weathering effect, age of the SS, hazardous contents etc. All these factors are applicable for LRFS also. Analyses of investigated slag by EDS have determined that CaO content was 19.02-51.34%, SiO2 (11.3–30.1%), Al2O3 (8.54–15.18%), MgO (7.66–18.84%), FeO(1.17–7.45%),MnO(0.22–1.34%),Cr2O3 (0.04–0.92%), P2O5 (1.52–3%),TiO2 (0.08–0.22%),K2O(0.19–1.68%)and Na2O(0.38–0.56%)[27].

Fig.3showsanX-rayFluorescence(XRF)spectrometer madeinUK.

Fig – 3: ThermoScientificARLQUANT'XXRF Spectrometer

Fig.3showstheARLQUANT’Xwhichisacompacthighperformance Energy Dispersive XRF (EDXRF). It was used to obtain the chemical compositions of the LRFS collected fromasteelmakingplantofBangladesh.

X-ray fluorescence(XRF) is the emission of characteristic "secondary" (or fluorescent)X-raysfrom a material that has been excited by being bombarded with high-energy X-rays orgamma rays. The phenomenon is widely used forelemental analysisandchemical analysis, particularly in the investigation

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

ofmetals,glass,ceramicsand building materials, and for researchingeochemistry,forensicscience,archaeologyand artobjects.[33]

The chemical composition of LRFS is most commonly investigated using XRF spectroscopy. It may be welldefined by different oxides present in LRFS. Mainly oxides like CaO, Al2O3, SiO2, MgO, Fe2O3, FeO, MnO, P2O5, TiO2, MnO2, SO3, Cr2O3, Na2O, K2O, TiO2, Free MgO and Free CaO etc.remainpresentinLRFS.Besidetheremaybealsoother several oxides, metallic or nonmetallic chemical elements i.e. S, C, P, Cr, Zn and F. Now comparisons of some constituents of the LRFS from different parts of the world aredescribedinthefollowingparagraphs.

Unlike natural stone, steel slag contains excess free calcium oxide (f-CaO) or/and free magnesium oxide (fMgO) on its surface. Free lime, with a specific gravity of 3.34, can react with water to produce Ca(OH)2, with a specific gravity of 2.23, which results in volume expansion [31]. Steel slag grains expansion can be caused by lime hydration and carbonation and magnesia hydration and carbonation [32]. So it is worth noting that this SS may be subjected to volumetric instability problems. Same is the casewithLRFS.

Someaspectscontributetothepresenceoffreelimeand periclase,dealingparticularlywiththesteelmakingprocess and to the slag cooling, from the heated furnace to environmental temperature at the dumping place. The existenceof freelimeandpericlase (MgO) inSSaffectsthe characteristicsofit.

InthecaseofSS,theslagcontainsmetallicelementssuchas ironinoxideform;however,becauserefiningtimeisshort andtheamountoflimestonecontainedislarge,aportionof the limestone auxiliary material may remain un-dissolved asfreeCaO[16].

The main chemical components found in LRFS are considered whose highest mass ranges more than 2% are listed below. There are total 12 oxide elements, i.e. CaO, SiO2, MgO, MnO, FeO, Fe2O3, Al2O3, Free Lime (CaO), SO3, P2O5, MnO2 and Free MgO are significantly found in LRFS. These elements together make about 98% of the total composition. A summary of these elements found from 30 different studies carried out in 13 countries are shown in thefollowingTable1.

Table-1: ChemicalCompositionofLRFS(%byMassofMainConstituents) Ser Source ChemicalCompositionofLRFS(%byMassofMainConstituents) CaO SiO2 MgO MnO FeO Fe2O3 Al2O3 Free CaO SO3 P2O5 Free MgO MnO2

1 Australia[34] 5250 999 039 055 250 1750 2 Melbourne,Australia[35] 2490 2293 866 3523 050 047 583 3 Chattogram,Bangladesh[36] 53.19 27.96 6.79 0.70 2.11 4 Chattogram,Bangladesh[37] 32.56 14.92 9.34 4.76 17.27 9.56 0.42 5 Chattogram,Bangladesh[38] 4435 2732 12.4 3 148 613 584 023 6 SouthWestBrazil[39] 6085 3065 730 090 265 245 025 7 Hamilton,Ontario,Canada[7] 5000 600 900 180 280 2900 040

8 Hamilton, Ontario, Canada [14] 4500 1850 550 250 750 2000 055 025

9 Ontario,Canada[40] 6523 1235 396 079 1655 10 5755 621 504 355 2317

11 China[41] 4950 1959 740 140 090 1230 250 040

12 Sisak,Croatia[23] 48.37 15.00 15.25 1.54 14.30 2.73

13 Greece[42] 5573 2410 593 160 153 077

14 India[7] 5250 450 900 010 100 3000 <01 15 India[43] 5040 590 850 010 100 3200

© 2022, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 7.529 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page1430

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

16 Romania[24]

40.78 17.81 8.53 9.79 9.25 3.97 4.23 0.74

17 49.56 14.73 7.88 0.39 0.44 0.22 25.55 0.20

18 Russia[44] 70.10 15.01 10.05 0.43 0.54 3.64

19 Revda,Sverdlovsk,Russia[45] 58.07 24.45 8.27 0.24 1.12 6.86

20 Magnitogorsk, Chelyabinsk, Russia[45] 50.39 14.32 8.89 3.71 8.06 14.64

21 Nizhny Tagil, Sverdlovsk, Russia[45]

52.66 18.39 7.64 0.36 0.66 20.29 22 59.07 12.80 4.89 0.46 0.15 22.6 3

23 Spain[11] 58.00 17.00 10.00 12.00 1.00 1.50(withothers)

24 Spain[46] 56.70 17.70 9.60 2.20 6.60 0.86 0.01

25 Spain[47] 54.00 14.3 16.50 1.77 10.30 5.00 14

26 Spain[12] 55.79 23.5 6.00 1.69 4.29

27 Sweden[29][48] 42.50 14.20 12.60 0.20 0.50 1.10 22.90

28 USandCanada[14] 45.00 18.5 5.50 2.5 7.55 20

29 USandCanada[49] 49.43 12.96 6.23 1.06 5.61

30 Crawfordsville, Indiana, USA [10] 47.52 4.64 7.35 1.00 7.61 22.59 2.30 0.09

The chemical compositions (%) by mass found in highest 2% are listed below. There are total 11 elements, i.e. S, C, Na2O, K2O, TiO2, Cr, Cr2O3, Zn, ZrO2, P and F are

seen to be scantily found in SS. A summary of these elements found from the above mentioned 30 studies are showninthefollowingTable2.

Table-2: ChemicalCompositionofLRFS(%byMassofMinorConstituents)

Ser Source ChemicalCompositionofLRFS(%byMassofMinorConstituents) Cr2O3 Na2O K2O TiO2 ZrO2 S C P Cr Zn F

1 Melbourne,Australia[35] 0.95 0.06 0.50

2 Chattogram,Bangladesh[37] 1.59 0.07

3 Chattogram,Bangladesh[38] 0.14 0.34

4 SouthWestBrazil[39] 0.90

5 Hamilton,Ontario,Canada[7] 0.50

6 Sisak,Croatia[23] 0.92 0.43 0.36 0.20

7 Greece[42] 0.60 0.30

8 India[7] 0.50 <0.1

9 India[43] 0.50 <0.1

10 Romania[24] 1.42 0.30 0.64

11 Romania[24] 0.80 0.07

12 Spain[11] 1.5(withothers)

13 Spain[46] 0.60

14 Spain[47] <0.1 1.50

© 2022, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 7.529 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page1431

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

15 USandCanada[14] 0.55 0.25 0.25

16 USandCanada[49] 0.25 0.01 0.01 0.34 1.33 0.38 0.08 1.66

17 Crawfordsville,Indiana,USA[10] 0.37 0.06 0.02 0.33 0.20 0.01

*Studiesdidnotfindanytraceoftheaboveelementsisnotshowninthetable.

6. DISCUSSIONS

The main chemical constituents of LRF slags can vary widely.Basedonthereviewofthe30studies,theCaO,SiO2, MgO, MnO, FeO, Fe2O3, Al2O3, Free Lime (CaO), SO3, P2O5, FreeMgOandMnO2 contentsofLRFslagsareinthe24.90–70.10%, 0–30.65%, 3.96–16.50%, 0–9.79%, 0-17.27%, 035.23%, 0-32%, 0-5%, 0-2.30%, 0-17.50%, 0-14% and 05.83% ranges, respectively. The widest range (45.20) was foundwiththeCaOandthenarrowestone(2.30)istheSO3 It shows CaO and MgO are the common main constituents of LRFS in all the 30 studies. Maximum 8 elements are found in the studies of China [41], India [7], Romania [24] andUSA[10]each.

From the studies, the highest CaO% was found in the LRFS of a study carried out in Russia [44]. Besides the lowestCaO% was found in the LRFS ofa studycarried out in Australia [35]. Free Lime (CaO) was found in LRFS of China [41]andSpain[47]significantlyandveryscantilyin Greece[42].Itismentionablethatthevolumeexpansionof SSdependspredominantlyonFreeLime(CaO).

MgO also contributes to expansion of SS [34]. The swelling potential of steel slag is of particular importance because of the free lime or magnesia in the slag [50]. The highestMgO%wasfoundintheLRFSofastudycarriedout in Spain [47]. Besides the lowest MgO% was found in the LRFS of a study carried out in Canada [40]. Free Lime (MgO) was found only in the LRFS of Spain [47] significantly and very scantily in Spain [11]. MgO which is one of the two common constituents, regulates and manages the crystallization, and further improves the sintering characteristics. It also increases porosity and bendingstrengthofLRFS.

Thekeyfactorprescribingslaguseisthealkaline-earth metal (e.g.,CaandMg)oxidecontents,whichcontributeto overall basicity and cementitious strength. However, asproduced steelmaking slag is chemically unstable as these oxides readily form hydroxides and carbonates through reaction with atmospheric gases. Both hydroxide and carbonate formation produce substantial mechanical swelling, leading to heave failure in confined construction applications.[51]

The highest SiO2% was found in the LRFS of a study carried out in Brazil [39]. Besides No trace of SiO2% was found in the LRFS of a study carried out in Australia [34].

SiO2 increases mechanical strength of the LRFS. SO3 was found in the LRFS studied in Bangladesh, Croatia, Egypt, Romania and USA. Steel slag contains a lot of metal elements such as calcium oxide (CaO) and silica and has goodcompressiveperformance[52].

The highest MnO% was found in the LRFS of a study carried out in Romania [24]. No MnO trace was found in LRFS in the studies of Australia [35], Canada [40], Croatia [23], Greece [42] and Spain [11, 12, 46, 47]. MnO shows highadsorptionabilityofanycompoundelement.

The highest FeO% found in LRFS in Bangladesh [37] is 17.27%. No trace of FeO was found in the SS of Australia [35], Brazil [39], Canada [40], China [41], Greece [42] and Spain[11,12,46,47].

Fe2O3 increases specific capacity, density, electrochemical properties and mechanical performance, but reduces pore size. The high iron oxide content of the aggregate results in very hard and very dense aggregate (20-30% heavier than naturally occurring aggregates such asbasaltandgranite)[53].ThehighestFe2O3 foundinLRFS inAustralia [35]is17.27%.NotraceofFe2O3 wasfoundin theSSofAustralia[34],Bangladesh[36,37,38],Canada[7, 14],Croatia[23],Russia[44,45],Spain[11]andUSA[10].

Again, the highest Al2O3% was found in the LRFS of a studycarriedoutinIndia[43].NotraceofAl2O3 wasfound in LRFS of studies in Australia [35], Bangladesh [36], USA andCanada[49].ItremovesmostoftheoxygenintheSSto produce deoxidized steel. Deoxidization provides abrasive property through hardness. It also provides strength throughdensificationandmechanicalstrength.

SO3% was significantly found only in LRFS in Australia [35], Canada [14], Spain [11, 46] and USA [10]. It may contributetotheexpansiveperformanceofLRFS.

The highest P2O5% found in LRFS in Australia [34] is 17.50%.NotraceofP2O5 wasfoundintheSSofBangladesh [36], Canada [40], Greece [42], Russia [44, 45], Spain [12, 47], Sweden [29, 48] and USA [14, 49]. P2O5 increases thermalstability,conductivity,andmechanicalflexibilityin a composite material. It might also show some hazardous characteristicswhenpresentintheLRFS.

MnO2 in a good percentage was found in a study carried out on SS of Australia [35] only. A trace was found

© 2022, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 7.529 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page1432

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

in a study carried out in Spain [11]. Some of the known heavy metals that might be present in LRFSare CrandZn. Although these heavy metals often appear only as trace elements,theyserveaskeyfactorsinpollutionandtoxicity [53].

If country wise averages are anyway considered, following Table 3 refers to the averages of the elements significantlyfoundinLRFS.

Table-3: ChemicalCompositionofMainConstituentsofLRFS(%ofAverageMass)

Serial Source Country ChemicalComposition(%ofAverageMass)ofMainConstituents CaO SiO2 MgO MnO FeO+ Fe2O3 Al2O3 Free CaO SO3 P2O5 Free MgO MnO2

1. Australia 38.70 11.47 9.33 0.20 17.89 1.25 0.25 8.99 2.92

2. Bangladesh 43.37 23.40 9.52 2.32 8.51 5.14 0.22

3. Brazil 60.85 30.65 7.30 0.90 2.65 2.45 0.25

4. Canada 54.45 10.77 5.88 1.08 3.66 22.18 0.14 0.17

5. China 49.50 19.59 7.40 1.40 0.90 12.30 2.50 0.40

6. Croatia 48.37 15.00 15.25 1.54 14.30 2.73 7. Greece 55.73 24.10 5.93 1.60 1.53 0.77 8. India 51.45 5.20 8.75 0.10 1.00 31.00 0.05 9. Romania 45.17 16.27 8.21 5.09 6.94 14.89 0.47 10. Russia 58.06 17.00 7.95 1.04 2.09 13.62 11. Spain 56.13 18.13 10.53 1.42 8.30 1.25 0.47 0.38 3.88 0.38 12. Sweden 42.50 14.20 12.60 0.20 1.60 12.90 13. USA 47.52 4.64 7.35 1.00 7.61 12.59 2.30 0.09

TheTable3shows,whenconsideredcountrywise,CaO, SiO2,MgOand Al2O3 arefoundinanyofthestudyonLRFS inallthe13sourcecountries.

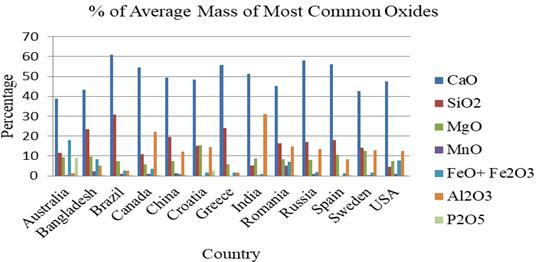

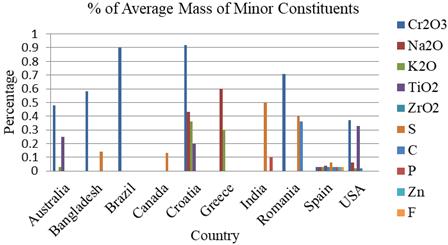

The Fig. 4 below gives a representation of the Table 3 showing the only the most common oxides of LRFS found commonly amongst the countries where studies were conducted.

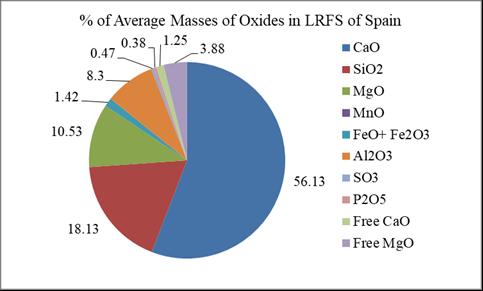

According to the averages shown in Table 3, the CaO, SiO2,MgO,FeO+Fe2O3 andAl2O3 arecommonamongthe13 countries. In Spain, ten oxides out of eleven shown in the Table 3 are found except MnO. The main constituents of LRFSinSpainareshownintheFig.5.

Fig – 4: ChemicalCompositionsofMostCommonOxides ofCountrywiseLRFS(%ofAverageMass)

Fig – 5: PercentagesofAverageMassesofOxidesFoundin LRFSofSpain

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

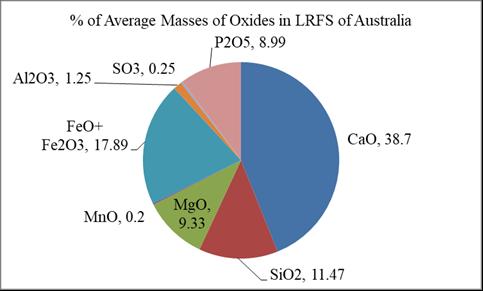

AgainexceptFreeCaOandFreeMgO,nineoxideelements were found in LRFS of Australia. The main constituents of LRFSofAustraliaareshownintheFig 6.

ThehighesttraceofK2Oinpercentageoftotalmasswas foundintheLRFSofastudycarriedoutinCroatia(0.36%). No trace of K2O was found in the LRFS of Bangladesh [36, 37,38],Brazil[39],Canada[7,14,40],China[41],Romania [24], Russia [44, 45] and Sweden [29, 48]. It improves densification and mechanical strength of a composite material.

Fig – 6: PercentagesofAverageMassesofOxidesFoundin LRFSofAustralia

ItisnoteworthythatEAFScompositionisdependenton the raw material source and its chemistry can vary from one batch to another. The rate of cooling from a molten liquidtoasolidmainlyaffectsthephysicalpropertiesofSS and as such, its chemical reactivity [15]. Same is the case withLRFS.

Based on the studies the ranges of Cr2O3, Na2O, K2O, TiO2,ZrO2,S,C,P,Cr,ZnandFandare0-1.59%,0-0.60%,00.36%, 0-0.60%, 0-0.20%, 0-1.50%, 0-0.64%, 0-0.25%, 00.25%,0-0.01%and0-1.66%respectively.

ThehighestCr2O3%wasfoundinLRFSinBangladeshis 1.59% [37]. However, no trace of Cr2O3 was found in the LRFS of Bangladesh [36], Canada [7], China [41], Greece [42], India [7, 43], Russia [44, 45], Spain [46, 47] and Sweden[29,48].Cr2O3 maybetheresponsibleoxideforthe color of the LRFS when present. It may also provide some resistancetoacid.

Some traces ofNa2O were found in theLRFS ofa study carriedoutinCroatia[23],Greece[42],Spain[11],USAand Canada[14].Howeverthehighestpercentagewas0.60%in Greece [42]. No trace of Na2O was found in the LRFS of Australia [34, 35], Bangladesh [36, 37, 38], Brazil [39], Canada [7, 14, 40], China [41], India [7, 43], Romania [24], Russia[44,45]andSweden[29,48].Na2Omaycontrol the crystallization, and further develops the sintering features andalsoincreasesporosityinacompositematerial.

TiO2 traces were found in the studies in Australia [35], Croatia [23], Spain [11, 46] and USA [10] and Canada [49] only. It may increase the surface area, specific capacity, adsorption efficiency and electro- chemical properties of LRFS.Thehighest TiO2%was found intheLRFSofa study carried out in Spain (0.60%) [46]. No trace of TiO2 was found in the LRFS of Bangladesh [36], Brazil [39], Canada [7, 14, 40], China [41], Greece [42], India [7, 43], Romania [24], Russia [44, 45] and Sweden [29, 48]. It may help in crystallization, viscosity, and mechanical properties of a compositematerial.

ZrO2 traces were found in LRFS of Spain [11] and USA [10]only.Thehighesttracewas0.20%inthestudyofUSA. ZrO2 may improve the microstructure properties and solubility. Again it may protect the composite structure fromcrackpropagation.

StraceswerefoundintheLRFSofBangladesh[37,38], Canada [7], India [7, 43], Romania [24], Spain [11, 47] and USA and Canada [14, 49]. No traces of S were found in Australia [34, 35], Brazil [39], China [41], Croatia [23], Greece[42],Russia[44,45]andSweden[29,48].

CtraceswerefoundintheLRFSofRomania[24],Spain [11]andUSAandCanada[49]only.Ptraceswerefoundin the LRFS of India [7, 43], Spain [11] and USA and Canada [14,49]only.

CrtraceswerefoundintheLRFSofSpain[11]andUSA and Canada [14] only. Cr is responsible for enhancing mechanical performance (tensile strength), interfacial bonding strength, and thermal conductivity of LRFS. Zn traces were found in the LRFS of Spain [11] and USA [10] only. F traces were found in the LRFS of USA and Canada [49]only.CompressivestrengthofLRFSmaydecreasewith increasingFcontent.

CountrywiseaveragesofminorelementsfoundinLRFS arepresentedinthefollowingTable4.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Table-4: ChemicalCompositionofMinorConstituentsofLRFS(%ofAverageMass)

Serial Source Country ChemicalComposition(%ofAverageMass)ofMinorConstituents Cr2O3 Na2O K2O TiO2 ZrO2 S C P Cr Zn F

1. Australia 0.48 0.03 0.25

2. Bangladesh 0.58 0.14 3. Brazil 0.90 4. Canada 0.13 5. Croatia 0.92 0.43 0.36 0.20

6. Greece 0.60 0.30 7. India 0.50 0.10 8. Romania 0.71 0.40 0.36 9. Spain 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.03 0.06 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.03

10. USA 0.37 0.06 0.02 0.33 0.02 0.01

*StudiesdidnotfindanytracesoftheaboveelementsinanyofthecountriesarenotshownintheTable4.

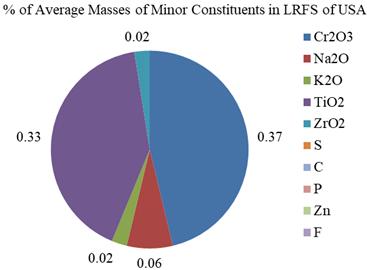

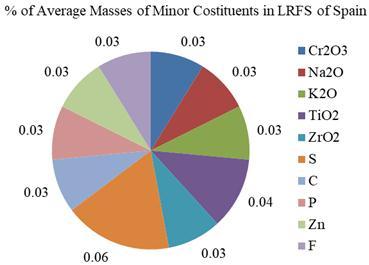

InagraphicalrepresentationoftheTable4wouldshow astheFig 7below.

Fig – 7: ChemicalCompositionsofMinorConstituentsof LRFS(%ofAverageMass)

Based on the averages of Table 4, all the ten elements werefoundintheLRFSstudiedinSpain,thoughinveryless percentages. Cr2O3,Na2O,K2O,TiO2,ZrO2,S,C,P,Cr,Znand F tracesarefoundinLRFSofSpain. Cr2O3,Na2O,K2O,TiO2, ZrO2 andZnarefoundintheLRFSofUSA.Theseareshown intheFig.8.

Fig-8: PercentagesofMinorConstituentsofLRFSinSpain andUSA

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

7. CONCLUSIONS

Formerly considered waste material, steel slag has become a valuable by-product used as a raw material for many industries and is almost fully utilized in some countries[54].TheproductionofthehugeamountofLRFS as co-products of steelmaking operations has become a greatconcernforthesteelindustry.Theamassingofahuge volume of LRFS has caused and causing several problems alsoeveryday.IfLRFSaresuitablyused,problemsofsteel industrywouldbereducedtoabearableone.

This paper summarizes the findings assimilated from a wide-ranging literature review focused on the chemical compositions related to different types of LRFS as well as recognizing corresponding areas of study for future viewpoints.Thebroadreviewimpliesthatthevariationsof the LRFS are based on the important differences in chemical compositions of LRFS. It is obvious that different types of chemical compositions result in different properties of LRFS. This also has a pronounced impact on theutilizationsofLRFS.

LRFS is a compound material of silicates, oxides and some elements that solidifies during cooling. There is characteristicallyahugevariationinthephysical,chemical, and mineralogical properties of all types of LRFS being generatedindifferentcornersoftheworld.Thisdifference depends on the steel-making plant, steel-making process, raw materials of the plants, and types of furnace, processing, the grade of steel produced, storage strategies and type, speed, rate and temperature of cooling etc. Further to add, LRFS may depend on the primary slag produced which is further refined. For this reason, the behaviorsandcharacteristicsofLRFSisverydifferentfrom one to another. Thus LRFS must be considered with credit oftheinherentvariabilityasitsuniqueness.

MoreoverthechemicalcompositionofLRFSvariesfrom country to country and even within the same country region to region and further due to the each and every single factor related with the production system. The dissimilarityisforthedifferencesinthecompositionofraw materialsused,forthedifferencesoftypesoffurnacesused or in operating procedures in batching or in others in the plantalso.Thusvariationscanevenbeseenfromfactoryto factory, plant to plant and even batch to batch. Even the ambienceinfluencesinproducingslag.

It can also be concluded that all LRFS perform very differently, depending on their chemical composition, and must be treated and studied individually. This inherent variability of LRFS offers a huge area for researchers to study.Thisvastresearchfieldmaybeexploredandstudied thoroughly and methodically to use LRFS in all the ways possible for the development of the human civilization.

Hence it can be said that LRFS warrants independent researchoneachandeverytypeofit.

Lastly the review conducted on the different kinds of LRFS studied by several researchers can be concluded like this. Considering the variations of the chemical compositions of LRFS, each type of LRFS requires a separate research to be able to understand the chemical characteristics of LRFS and related engineering properties foritsapplicationsinthedesiredfields.

REFERENCES

[1] World Steel Association (WSA) (2022). “Total production of crude steel - World Total 2021”. https://worldsteel.org/steel-by-topic/statistics/ annual-production-steel_data/P1_crude_steel_total _pub/CHN/IND/WORLD_ALL

[2] WorldSteelAssociation(WSA)(2022).“2022World steel in figures”. https://worldsteel.org/wp-content /uploads/World-Steel-in-Figures-2022.pdf.

[3] WorldSteelAssociation(WSA)(2021).“2021World steel in figures”. https://www.worldsteel.org/en/ dam/jcr:976723ed-74b3-47b4-92f681b6a452b86e/ World%2520Steel%2520in%2520Figures%252020 21.pdf.

[4] Awoyera,P.O.etal.(2016).“Performanceof steelslagaggregateconcretewithvariedwatercementratio”.JurnalTeknologi(Sciences& Engineering)78:10(2016)125–131,eISSN2180–3722,www.jurnalteknologi.utm.my

[5] Branca,T.A.etal.(2020).“Reuseandrecyclingofbyproducts in the steel sector: recent achievements paving the way to circular economy and industrial symbiosis in Europe”. Metals2020,10(3), 345;https://doi.org/10.3390/met10030345.

[6] IspatGuru(2022).“SteelmakingSlag”. https://www.ispatguru.com/steel-making-slag/.

[7] Aminorroaya-Yamini,S.;Edris,H.;Tohidi,A.; Parsi, J. & Zamani, B. (2004). "Recycling of ladle furnace slags". Australian Institute for Innovative Materials - Papers. 1408. https://ro.uow.edu.au/ aiimpapers/1408

[8] ScienceDirect(2022).https://www.sciencedirect. com/topics/engineering/ladle-slag.

[9] Setien,J.;Hernandez,D.andGonzalez,J.J.(2009) “Characterizationofladlefurnacebasicslagforuse asaconstructionmaterial”.Constructionand BuildingMaterials,Vol.23,no.5,pp.1788–1794,

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

May2009,DOI:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.10.003, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248541 772_Characterization_of_Ladle_Furnace_Basic_Slag_f or_Use_as_a_Construction_Material.

[10] Yildirim,I.Z.andPrezzi,M.(2011).“Chemical, mineralogical,andmorphologicalpropertiesofsteel slag,”AdvancesinCivilEngineering,Vol.2011, ArticleID463638,13pages,2011,https://www. hindawi.com/journals/ace/2011/463638/

[11] Manso,J.M.;Losañez,M.;Polanco,J.A.& González,J.J.(2005).“Ladlefurnaceslagin construction”. J. Mater. Civ. Eng., 2005, 17(5):513518, DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)0899 156(2005)17:5 (513).

[12] Vilaplana, A. S.-de-G.et al. (2015). “Utilization of ladle furnace slag from a steel work for laboratory scaleproductionof portlandcement”.Construction and Building Materials 94 (2015) 837–843, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07. 075.

[13] Manso,J.M.;Polanco,J.A.;Losañez,M.& González,J.J.(2006).“Durabilityofconcretemade withEAFslagasaggregate” CementandConcrete Composites 2006, 28 (6): 528 –534, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2220 15952_Durability_of_concrete_made_with_EAF_sla g_as_aggregate.

[14] Shi, C. (2004). “Steel slag its production, processing,characteristics,andcementitious properties”.JournalofMaterialsinCivil Engineering, Vol. 16, No. 3, June 1, 2004. ©ASCE, ISSN 0899-1561/2004/3-230–236/ $18.00, DOI: 10.1061/~ASCE!0899-1561~2004!16:3~230!, https://ascelibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1061/%28AS CE%290899-1561%282004%2916%3A3%28230 %29.

[15] Maharaj, C.; White, D.; Maharaj, R. & Morin, C. (2017). “Re-use of steel slag as aaggregate to asphalticroadpavementsurface”.Article:1416889, Published online: 25 Dec 2017, https://www.tandf online.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311916.2017.141 6889.

[16] Tarawneh, S. A.; Gharaibeh, E. S. & Saraireh, F. M. (2014). “Effect of using steel slag aggregate on mechanical properties of concrete”. American Journal of Applied Sciences 11(5):700-706, 2014 ISSN: 1546-9239©2014 Science Publication 700 AJAS,DOI:10.3844/ajassp.2014.700.706,Published

Online 11 (5) 2014, http://www.thescipub. com/ajas.toc

[17] Jiang, Y.; Ling, T.-C.; Shi, C. & Pan, S.-Y. (2018). “Characteristics of steel slags and their use in cementandconcrete Areview”.Resour.Conserv. Recycl.2018,136, 187–197, https://agris.fao.org/ agris-search/search.do?recordID=US2018004515 36.[CrossRef]

[18] Roychand,R.;Pramanik,B.K.;Zhang,G.&Setunge, S. (2020). “Recycling steel slag from municipal wastewater treatment plants in to concrete applications – A step toward circular economy”. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104533, https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?reco rdID=US202000025036.[CrossRef]

[19] National Slag Association (2003). "Iron and steel making slag environmentally responsible constructionaggregates". NSATechnicalBulletin may 2003. http://www.nationalslag.org/steelslag .htm

[20] Patel,J.P.(2008).“Broaderuseofsteelslag aggregatesinconcrete”.ClevelandState University, ETD Archive. 401, https://engagedscho larship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/401 [CrossRef]

[21] Shi, C. (2002). “Characteristics and cementitious propertiesofladleslagfinesfromsteelproduction.” Cem.Concr. Res.,32(3),459–462,ISSN0008-8846, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(01)007074, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p ii/S0008884601007074).

[22] Branca, T. A., Colla, V., and Valentini, R. (2009). “A way to reduce environmental impact of ladle furnace slag.” Ironmaking and Steelmaking, 36(8), 597–602, DOI: 10.1 179/030192309X1249291093 7970, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/ 10.1179/030192309X12492910937970?scroll=top &needAccess=true.

[23] Radenovic, A.; Malina, J. & Sofilic, T. (2013). “Characterizationof ladlefurnaceslagfromcarbon steel production as a potential adsorbent”. AdvancesinMaterialsScienceandEngineering,Vol. 2013, Article ID 198240, Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/20 13/198240

[24] Nicolae, M.; Vîlciu, I. & Zăman, F. (2007). “X-Ray Diffraction analysis of steel slag and blast furnace slagviewingtheiruseforroad”.ConstructionU.P.B. Sci. Bull., Series B, Vol. 69, No. 2, 2007, ISSN 1454-

© 2022, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 7.529 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page1437

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

2331, https://www.scientificbulletin.upb.ro/rev_ docs_arhiva/full55633.pdf.

[25] Manso, J. M.; Gonzalez, J. J. & Polanco, J. A. (2004). “Electric Arc Furnace slag in concrete”. Journal of MaterialsinCivilEngineering2004,16(6):639-645, ©ASCE/ November/December 2004, DOI: 10.1061 /(ASCE)0899–1561(2004)16:6(639), https://asceli brary.org/doi/10.1061/%28ASCE%2908991561% 282004%291%3A6%28639%29.

[26] Kourounis, S; Tsivilis, S; Tsakiridis, P.E.; Papadimitriou, G.D.; Tsibouki, Z. (2007). “Propertiesandhydrationofblendedcementswith steelmaking slag”. Cement Concrete Res 2007; 37: 815-822, https://paratechglobal.com/wp-content/ uploads/2020/01/Properties-and-hydration-ofblended-ceme.pdf.

[27] Sofilić,T.;Mladenovič,A.;Oreščanin,V.&Barišić,D. (2013). “Characterization of Ladle Furnace Slag from the Carbon Steel Production”. 13th International Foundrymen Conference on Innovative Foundry Processes and Material, May, 16 -17, 2013, Opatija, Croatia, www.simet.hr/~fou ndry, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 305501709.

[28] Oluwasola, E. A.; Hainin, M. R. & Aziz, M. M. A. (2014).“Characteristicsandutilizationofsteelslag in roadconstruction”. Jurnal Teknologi(Sciences& Engineering) 70:7(2014), 17–123, eISSN 2180–3722,www.jurnalteknologi.utm.my.

[29] Engström, F. (2007). “Mineralogical influence of different cooling conditions on leaching behaviour of steelmaking slags”. Licentiate Thesis, Minerals and Metal Recycling Research Centre, Luleå University of Technology, Department of Chemical engineering and Geoscience, Division of Process MetallurgySE-97187,Luleå,Sweden.

[30] Ortega-L´opez, V., Manso; J. M.; Cuesta, I. I., and González, J. J. (2014). “The Long-Term accelerated expansion of various ladle-furnace basic slags and their soil stabilization applications”. Constr. Build. Mater., 68, 455–464, DOI: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat. 2014.07.023, https://www.researchgate.net/publ ication/273626022_The_long-term_accelerated _expansion_of_various_ladle-furnace_basic_slags_ and_their_soil-stabilization_applications.

[31] Wang, G.; Wang, Y. H. & Gao, Z. L. (2010). “Use of steelslagasagranularmaterial:volumeexpansion prediction and usability criteria”. J. Hazard. Mater.

184 (1–3): 555–560, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jhazmat.2010.08.071

[32] Waligora, J. et al. (2010). “Chemical and mineralogical characterizations of LD converter steel slags: A multi-analytical techniques approach”.MaterialsCharacterizationVol.61,Issue 1, January 2010, Pages 39-48, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/ abs/pii/S104458030903192.[CrossRef]

[33] Wikipedia (2022). “X-Ray Flouresence”. https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/X-ray_fluorescence

[34] Wang, G. W., (1992). “Properties and utilization of steelslaginengineeringapplications”.Universityof Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016, 1992. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1258/.

[35] Maghool,F.;Arulrajah,A.;Horpibulsuk,S.&Du,Y.J. (2017).“Laboratoryevaluationofladlefurnaceslag in unbound pavement-base/subbase applications”. Journal of Materials in Civil, Engineering, 2017 29(2):0 4016197, DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-55 33.0001724, https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/ %28ASCE%29MT.1943-5533.0001724.

[36] GPHIspatLimited(NewPlant)(2022).Test Certificate of LRF Slag, January 2022, Quality Control Department, GPH Ispat Limited (New Plant),Chattogram,Bangladesh.

[37] GPHIspatLimited(NewPlant)(2022).Test Certificate of LRF Slag, March 2022, Quality Control Department, GPH Ispat Limited (New Plant),Chattogram,Bangladesh.

[38] GPHIspatLimited(NewPlant)(2022).Test Certificate of LRF Slag, July 2022, Quality Control Department, GPH Ispat Limited (New Plant), Chattogram,Bangladesh.

[39] Marinho, A. L. B. et al. (2017). “Ladle furnace slag as binder for cement-base composites”. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2017, 29(11): 04017207, DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533. 0002061, https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/% 28ASCE%29MT.1943-5533.0002061.

[40] Mahoutian, M.; Ghouleh, Z. & Shao, Y. (2014). “Carbon dioxide activated ladle slag binder.” Construct. Build. Mater. 66, 214e221, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.05.063

[41] Qian,G.R.;Sun,D.D.;Tay,J.H.&Lai,Z. Y.(2013). “Hydrothermal reaction and autoclave stability of

© 2022, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 7.529 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page1438

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 09 Issue: 09 | Sep 2022 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

mgbearingrophaseinsteel slag”.Pages159-164, Published online: 18 Jul 2013, https://doi.org/ 10.1179/096797802225003415.

[42] Papayianni, I. & Anastasiou, E. (2011). “Effect of granulometry on cementitious properties of ladle furnace slag”. Cement & Concrete Composites 34 (2012) 400–407, DOI: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.20 11.11.015.

[43] Kumar, S. et al. (2019). “Recent trends in slag management & utilization in the steel industry”. Minerals & Metals Review – January 2019, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 330701277_Recent_trends_in_slag_management_ utilization_in_the_steel_industry.

[44] Sheshukov O. Yu.; Mikheenkov M. A.; Egiazaryan D. K.; Ovchinnikova L. A. & Lobanov D. A., (2017). “Chemical stabilization features of ladle furnace slag in ferrous metallurgy”. International Conference with Elements of School for Young Scientists on Recycling and Utilization of Technogenic Formations, KnE Materials Science, 59–64.DOI:10.18502/kms.v2i2.947.

[45] SheshukovO.Yu.etal.(2017).“Unitladle-furnace: slag forming conditions and stabilization”. International Conference with Elements of School forYoungScientistsonRecyclingandUtilizationof Technogenic Formations, KnE Materials Science, 70–75.DOI:10.18502/kms.v2i2.949.

[46] Manso, J. M.; Ortega-López, V.; Polanco, J. A. & Setién,Jesus(2013).“Theuseofladlefurnaceslag in soil stabilization”. Construction and Building Materials 40 (2013) 126–134, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.09.079.

[47] Montenegro,J.M.;Celemín-Matachana,M.;Cañizal, J. & Setién, J. (2013). “Ladle furnace slag in the construction of embankments: expansive behavior”. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 25, No. 8, August 1, 2013, DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000642, https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/%28ASCE% 29MT.1943-5533.0000642.

[48] Tossavainen, M. et al. (2006). “Characteristics of steel slag under different cooling conditions”. Waste Management 27 (2007) 1335–1344, DOI: 10.1016/j.wasman.2006.08.002, https://www.sci encedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S095605 3X06002315.

[49] Rawlins, C.H. (2008). “Geological sequestration of carbon dioxide by hydrous carbonate formation in steelmakingslag”.DoctoralDissertations,1927, https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertatio ns/1927.

[50] Asi,I.M.;Qasrawi,H.Y.&Shalabi,F.I.(2007).“Use of steel slag aggregate in asphalt concrete mixes”. CanadianJournalofCivilEngineering,August2007, DOI:10.1139/L07-025,NRCResearchPress, www.cjce.nrc.ca on 14 August 2007, https://cdnsci encepub.com/doi/10.1139/l07-025.[CrossRef]

[51] Lekakh, S.N.; Rawlins, C.H.; Robertson, D.G.C.; Richards, V.L. & Peaslee, K.D. (2008). “Kinetics of aqueous leaching and carbonization of steelmaking slag”.DOI:10.1007/s11663-007-9112-8,https://sc holar.google.com/scholar?q=DOI:+10.1007/s11663 -007-1128&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart.

[52] Yu, Q. et al. (2021). “A review on the effect from steel slag on the growth of microalgae”. Processes 2021,9,769.https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9050769.

[53] Washington State DOT (2015). “WSDOT strategies regardinguseofsteelslagaggregateinpavements”. Construction Division Pavements Office, November 2015, https://app.leg.wa.gov/ReportsToTheLegis lature/Home/GetPDF?fileName=SteelSlagAggregat eReportNovember2015_55c0218c-1ac4-4beb-89b e-ea05a899906b.pdf.

[54] Dhoble, Y.N. & Ahmed, S. (2018). “Review on the innovative uses of steel slag for waste minimization”.JournalofMaterialCyclesandWaste Management (2018) 20:1373–1382, https://doi. org/10.1007/s10163-018-0711-z

© 2022, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 7.529 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page1439